Submitted:

23 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

3. Results

3.1. Water Resource Management in Central Asia: Historical Context and Contemporary Challenges

- BO Amu Darya oversees 84 hydropower stations, including 36 head river water intakes, 169 hydro-posts, and 386 kilometers of interstate canals in Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

- BO Syr Darya manages 198 hydraulic structures, with 21 located on major tributaries such as the Naryn, Syr Darya, Karadarya, and Chirchik rivers.

3.2. The Qush Tepa Canal: A Disruptive Development in Transboundary Water Management

3.3. Legal and Institutional Framework for Water Governance in Central Asia

- International Treaties and Agreements – All international water-related treaties ratified by the Republic of Kazakhstan, which establish frameworks for transboundary water cooperation and management.

- Constitutional Provisions – Article 6 of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan, which defines the legal status and ownership of natural resources, including water.

-

National Water and Environmental Legislation – Key legislative acts governing water resource management, including:

- Water Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan (July 9, 2003, No. 481-II)

- Code on Administrative Offenses (January 9, 2007, No. 212-III)

- Environmental Code (2007)

- Land Code (June 20, 2003, No. 442-II)

- National Water Resource Management Strategy – Presidential Decree approving the National Plan for Integrated Water Resource Management and Water Use Efficiency Improvement (2009-2025), aimed at ensuring sustainable water use and addressing water security challenges.

- Government Regulations and Policy Frameworks – Resolutions and legislative acts that influence public administration and regulatory mechanisms for water resource management, such as the Resolution of the Government of Kazakhstan (January 28, 2009, No. 67).

- Regulatory Framework for Water Governance – National laws and regulations that govern water use, conservation, and distribution, ensuring compliance with environmental and sustainability standards.

- Subordinate Legislative Acts – Sector-specific regulations and executive orders that support the implementation of national water policies and ensure alignment with broader environmental objectives.

- Customary Practices in Water Management – Traditional and regionally accepted practices influencing business and community-level water use, particularly in rural and agricultural sectors.

- Economic and Trade-Related Water Regulations – Legislative frameworks governing water-related business activities, including commercial water use, hydropower development, and irrigation for agricultural enterprises.

- Public-Private Partnership and Stakeholder Engagement Mechanisms – Policies and initiatives facilitating collaboration between the government, private sector, and civil society in water resource management, ensuring inclusive and sustainable governance.

3.4. Aims and Objectives of Water Legislation in the Republic of Kazakhstan

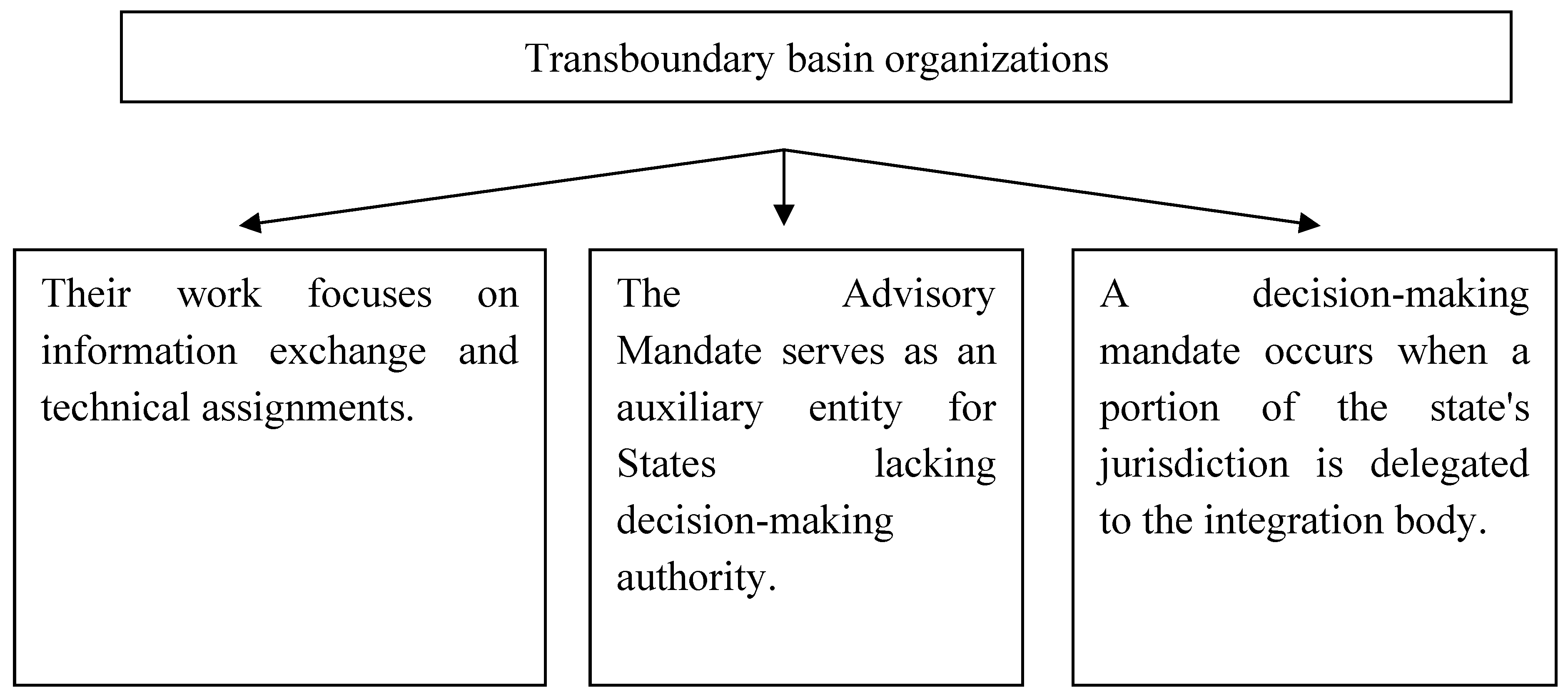

3.5. Transboundary Basin Organizations and Their Challenges

3.6. Institutional Stability and International Best Practices

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koncagül, E. and R. Connor, The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023: partnerships and cooperation for water; facts, figures and action examples. 2023.

- Abdullaev, I., et al., Current challenges in Central Asian water governance and their implications for research, higher education, and science-policy interaction. Central Asian Journal of Water Research, 2025. 11(1): p. 47-58.

- Janusz-Pawletta, B., Current legal challenges to institutional governance of transboundary water resources in Central Asia and joint management arrangements. Environmental earth sciences, 2015. 73(2): p. 887-896. [CrossRef]

- McKinney, D.C., Cooperative management of transboundary water resources in Central Asia. In the Tracks of Tamerlane: Central Asia’s Path to the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Defense University, 2004: p. 187-220.

- Mukhammadiev, B., Challenges of transboundary water resources management in Central Asia, in The Aral Sea: The Devastation and Partial Rehabilitation of a Great Lake. 2013, Springer. p. 233-251.

- Wang, X., et al., Water resources management and dynamic changes in water politics in the transboundary river basins of Central Asia. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 2021. 25(6): p. 3281-3299. [CrossRef]

- Janusz-Pawletta, B. and M. Gubaidullina, Transboundary water management in Central Asia. Legal framework to strengthen interstate cooperation and increase regional security. Cahiers d’Asie centrale, 2015(25): p. 195-215.

- Xenarios, S., et al., Current and future challenges of water security in Central Asia. Global Water Security: Lessons Learnt and Long-Term Implications, 2018: p. 117-142.

- Amirova, I., M. Petrick, and N. Djanibekov, Community, state and market: Understanding historical water governance evolution in Central Asia. 2022.

- Punkari, M., et al., Climate change and sustainable water management in Central Asia. ADB Central and West Asia working paper series, 2014. 5.

- Isaev, E., et al., High-resolution dynamic downscaling of historical and future climate projections over Central Asia. Cent. Asian J. Water Res, 2024. 10: p. 91-114. [CrossRef]

- Sadyrov, S., et al., High-resolution assessment of climate change impacts on the surface energy and water balance in the glaciated Naryn River basin, Central Asia. Journal of Environmental Management, 2025. 374: p. 124021. [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, T. and T. Siegfried, Climate change and international water conflict in Central Asia. Journal of Peace Research, 2012. 49(1): p. 227-239. [CrossRef]

- Reyer, C.P., et al., Climate change impacts in Central Asia and their implications for development. Regional Environmental Change, 2017. 17: p. 1639-1650. [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, T., et al., Will climate change exacerbate water stress in Central Asia? Climatic Change, 2012. 112: p. 881-899.

- White, C.J., T.W. Tanton, and D.W. Rycroft, The impact of climate change on the water resources of the Amu Darya Basin in Central Asia. Water Resources Management, 2014. 28: p. 5267-5281. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L., et al., Climate Change Impacts and Atmospheric Teleconnections on Runoff Dynamics in the Upper-Middle Amu Darya River of Central Asia. Water, 2025. 17(5): p. 721. [CrossRef]

- Kozhagulov, S., et al., Trends in Atmospheric Emissions in Central Asian Countries Since 1990 in the Context of Regional Development. 2025.

- Sidle, R., et al., Dynamics in the Water Towers of the Pamir and Downstream Consequences. 2022.

- Rogers, A., Predicting Biodiversity Loss: A Global Analysis of Red List Index Trends and Key Drivers (2002–2021). Available at SSRN 5106872.

- Toymbaeva, D., D. Mamatova, and X. Ergashev, GEOECOLOGICAL PROBLEMS OF UZBEKISTAN AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE REGION. Web of Humanities: Journal of Social Science and Humanitarian Research, 2025. 3(2): p. 15-26.

- Wang, X., et al., Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanism of Aboveground Biomass Across Three Alpine Grasslands in Central Asia over the Past 20 Years Using Three Algorithms. Remote Sensing, 2025. 17(3): p. 538. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., et al., Scale effects of spatial patterns of ecosystem services in the Tarim River Basin in Central Asia. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2025. 197(3): p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C., et al., Sediment sources, erosion processes, and interactions with climate dynamics in the Vakhsh River Basin, Tajikistan. Water, 2023. 16(1): p. 122. [CrossRef]

- Bank, A.D. In Numbers: Climate Change in Central Asia. 2025 February 24, 2025; Available from: https://www.adb.org/ru/news/features/numbers-climate-change-central-asia.

- Bank, W. Country Profiles with Climate Risks. 2021 February 21, 2025; Available from: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country-profiles.

- Karchegani, A.M., A. Mohammadpour, and M. Tavakoli, Assessing the Determinants of Effective Transboundary Water Resource Management Strategies in the Harirud River Basin, Iran.

- Spoor, M. and L. Thiemann, Hydro-Authoritarianism: Mega-Engineering the (Semi-) Arid Regions of Central Eurasia and China. Europe-Asia Studies, 2025: p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Feng, K., et al., Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Drought and the Ecohydrological Response in Central Asia. Remote Sensing, 2025. 17(1): p. 166. [CrossRef]

- Karimov, A., et al., Of transboundary basins, integrated water resources management (IWRM) and second best solutions: The case of groundwater banking in Central Asia. Water Policy, 2012. 14(1): p. 99-111. [CrossRef]

- Michael, B., Approaches to optimize Uzbekistan’s investment in irrigation technologies. Экoнoмическая пoлитика, 2020. 15(2): p. 136-147.

- Bhat, S.A., M.I. Wani, and P.S.U. Irfan, Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy Potential of Central Asian States: An Analysis in Market Demand. Peerzada Shams Ul, Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy Potential of Central Asian States: An Analysis in Market Demand.

- Chowdhury, A., Z. Tadjoeddin, and Y. Vidyattama, Landlocked Central Asia: The Peril of Transition, in Structural Transformation as Development: Path Dependence and Geopolitics. 2025, Springer. p. 173-202.

- Aituarova, G. and T.L. Kh, THE ROLE OF INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL ORGANIZATIONS IN SOLVING THE PROBLEM OF WATER SHORTAGE IN CENTRAL ASIA. Вестник науки, 2025. 4(2 (83)): p. 352-358.

- Balas, A., The European Union's Role in Addressing Environmental Disputes in Central Asia: Evaluating the Effectiveness of a “Reluctant 3rd Party”, in European Union Governance in Central Asia. 2025, Routledge. p. 111-130.

- Goziyev, R., The Challenges of Maintaining Regional Security in Central Asia Amid Modern Threats, in International Relations Dynamics in the 21st Century: Security, Conflicts, and Wars. 2025, IGI Global Scientific Publishing. p. 349-368.

- Qudbidinova, K., DEHYDRATION CHALLENGES IN CENTRAL ASIA: A LOOMING CRISIS. Web of Scientists and Scholars: Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 2025. 3(2): p. 141-148.

- Horsman, S., Transboundary water management and security in Central Asia, in Limiting institutions? 2018, Manchester University Press. p. 86-104.

- Anghelescu, A.-M. and I.-D. Onel, The EU's Green Normative Power in Central Asia: The Case of the Aral Sea and Water Management Policies in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, in European Union Governance in Central Asia. 2025, Routledge. p. 91-110.

- Brody, M., et al., The Global Energy and Water Exchanges (GEWEX) Project in Central Asia: The Case for a Regional Hydroclimate Project. 2024, Springer. [CrossRef]

- van Oevelen, P., et al. A New Gewex Regional Hydroclimate Activity in Central Asia. in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. 2024.

- Faqiryar, J.N. Food-Climate Nexus in the North River Basin of Afghanistan: A Case Study of the Qush Tepa National Irrigation Canal. 2024. MISC.

- Kuchins, A.C., et al., Afghanistan’s Qoshtepa Canal and Water Security in Central Asia. 2024.

- Sarbiland, H. and I. Stanikzai, Qosh Tepa Canal Impact On Economic Development: Historical Significance And Assessing SDGs 2030 In Afghanistan. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 2024. 30(7): p. 593-601. [CrossRef]

- Wesch, S., Central Asia: Challenges and Opportunities by Way of the Middle Corridor. Climate. Changes. Security: Navigating Climate Change and Security Challenges in the OSCE Region, 2024: p. 175-193.

- Berdiyev, A., Concept for the Development of the Water Management Sector in Turkmenistan. Document for Discussions, Changes, and Additions. 2018.

- Kazakhstan, R.o., Water Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2003.

- Kazakhstan, R.o. Message of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan N. Nazarbayev to the People of Kazakhstan, December 14, 2012. 2012 25 October 2018; Available from: http://www.akorda.kz/ru/addresses/addresses_of_president/poslanie-prezidenta-republics-kazakhstan-nnazarbaeva-narodu-kazahstana-14-dekabrya-2012-g.

- Kazakhstan, R.o. Strategy "Kazakhstan-2050". 2018 25 October 2018; Available from: http://www.akorda.kz/ru/official_documents/strategies_and_programs.

- Republic, K., Sustainable Development Strategy of the Kyrgyz Republic for 2018–2040 (Project) "TAZA KOOM. ZHANGY DOOR". 2017, Republic of Uzbekistan.

- Turkmenistan, Water Code of Turkmenistan. 2004.

- Turkmenistan, National Climate Change Strategy of Turkmenistan. 2018.

- Uzbekistan, R.o., Law on Water and Water Use. 1993.

- Uzbekistan, R.o. Strategy of Action on Five Priority Directions of Development of the Republic of Uzbekistan in 2017–2021. 2018 25 October 2018; Available from: http://old.lex.uz/pages/getpage.aspx?lact_id=3107042.

- Libert, B. and A. Lipponen, Challenges and opportunities for transboundary water cooperation in Central Asia: findings from UNECE's regional assessment and project work. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 2012. 28(3): p. 565-576. [CrossRef]

- Mosello, B., Water in Central Asia: a prospect of conflict or cooperation? Journal of Public and International Affairs, 2008.

- Xie, L. and I.A. Ibrahim, Is the ecosystem approach effective in transboundary water systems: Central Asia as a case study? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 2021. 8(5): p. e1542.

- Izquierdo, L., et al., Water crisis in Central Asia: Key challenges and opportunities. Graduate Program in International Affairs, New School University, 2010. 7.

- Mamatova, Z., D. Ibrokhimov, and A. Dewulf, The wicked problem of Dam governance in Central Asia: Current trade-offs, future challenges, prospects for cooperation. International journal of water governance, 2016. 4: p. 1-10.

- Vinokurov, E., et al., Regulation of the Water and Energy Complex of Central Asia. 2022, Eurasian Development Bank: Almaty, Moscow.

- Khikmatov, F., et al., Hydrometeorological conditions of low-water years in the mountain rivers of Central Asia. International journal of scientific & technology research, 2020. 9(02): p. 2880-2887.

- Hamidov, A., et al., How Can Intentionality and Path Dependence Explain Change in Water-Management Institutions in Uzbekistan? International Journal of the Commons, 2020. 14: p. 16-29.

- Asia, P.o.k.o.w.r.a.e.o.C. Formation of Surface Runoff Water Resources in the Aral Sea Basin. 2018 October 25, 2018; Available from: http://www.cawater-info.net/aral/water.htm.

- Duzdaban, E., Water issue in Central Asia: Challenges and opportunities. Eurasian Research Journal, 2021. 3(1): p. 45-62.

- Amirova, I., M. Petrick, and N. Djanibekov, Long- and short-term determinants of water user cooperation: Experimental evidence from Central Asia. World Development, 2019. 113: p. 10-25. [CrossRef]

- Sidle, R.C., et al., Food security in high mountains of Central Asia: A broader perspective. BioScience, 2023. 73(5): p. 347-363. [CrossRef]

- Kasymov, U. and A. Hamidov, Comparative Analysis of Nature-Related Transactions and Governance Structures in Pasture Use and Irrigation Water in Central Asia. Sustainability, 2017. 9: p. 1633.

| State | Key Regulatory and Legal Acts on Water Resources | National Water Strategy |

| Republic of Kazakhstan | - Constitution of Kazakhstan (1995) - Water Code (2003) - Environmental Code (2007) - National Plan for Collaborative Water Resource Management and Efficiency Improvement (2009-2025) - Concept of the Green Economy (2013) - State Water Resources Management Program (2014) |

Strategy 2050: - Comprehensive analysis of national water management strategies and conservation efforts - Adoption of advanced technologies for groundwater extraction and efficient usage - Implementation of moisture-conserving technologies - Addressing nationwide water supply issues by 2050 - Resolving irrigation water challenges by 2040 |

| Republic of Kyrgyzstan | - Constitution of Kyrgyzstan (2010) - Water Code (2005) - Environmental Protection Act (1999) - Law on Associations of Water Users (2002) |

Sustainable Development Strategy 2040: - Implementation of water conservation and recycling technologies - Establishment of a national water recycling and replenishment system - Ensuring universal access to potable water - Transitioning towards a market-based water management system - Strengthening oversight of mining operations to prevent water contamination |

| Republic of Uzbekistan | - Constitution of Uzbekistan (1992) - Law on Water and Water Use (1993) - Nature Conservation Act (1992) - Environmental Control Act (2013) |

Strategy for Further Development: - Expansion of water-conserving technologies to rehabilitate degraded lands - Expansion of potable water networks in rural areas - Construction of 415 km of new water supply infrastructure |

| Republic of Tajikistan | - Constitution of Tajikistan (1994) - Water Code (2000) - Law on Water Users Associations (2006) - Environmental Protection Act (2011) - Drinking Water and Sanitation Act (2010) |

National Development Strategy 2030: - Development and expansion of hydropower infrastructure - Modernization of existing hydro and thermal power plants - Implementation of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) - Strengthening water sector institutions - Optimization of irrigation and reclamation practices - Strengthening policies to prevent water pollution - Rehabilitation of irrigation and drainage systems to increase water availability - Support for the development of Water Users Associations (WUA) |

| Republic of Turkmenistan | - Constitution of Turkmenistan (1992) - Water Code (2004, revised in 2016) - Law on Nature Protection (2014) - Law on Drinking Water (2010) |

Water Management Development Framework 2030: - Ensuring environmental protection and sustainable resource use - Strengthening the legal framework governing water resources - Encouraging public and inter-industry participation in water infrastructure development - Establishing community-based water management councils (Mirabs) - Expanding e-government initiatives for water sector transparency - Increasing the reuse of treated wastewater |

| Indicators | Turkmenistan | Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Uzbekistan | Tajikistan |

| Irrigated land | 0.146 | 0.035 | 0.102 | 0.458 | 0.227 |

| Industry | 28,916 | 11,556 | 5,504 | 12,026 | 1,643 |

| Services | 19,228 | 31,380 | 17,298 | 14,026 | 5,472 |

| General indicators | 1,525 | 7,201 | 0.842 | 1,431 | 0.882 |

| State | River basin | Aral Sea Basin | ||

| Syr Darya | Amu Darya I | km 3 | % | |

| Kazakhstan | 2,516 | - | 2,516 | 2,2 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 27.54 2 | 1,654 | 29,196 | 25.2 |

| Tajikistan | 1,005 | 58,732 | 59,737 | 51.5 |

| Turkmenistan | - | 1,405 | 1,405 | 1,2 |

| Uzbekistan | 5,562 | 6,791 | 12,353 | 10.6 |

| Afghanistan and Iran | - | 10,814 | 10,814 | 9.3 |

| Aral Sea Basin Summary | 36,625 | 79,396 | 116,021 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).