Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

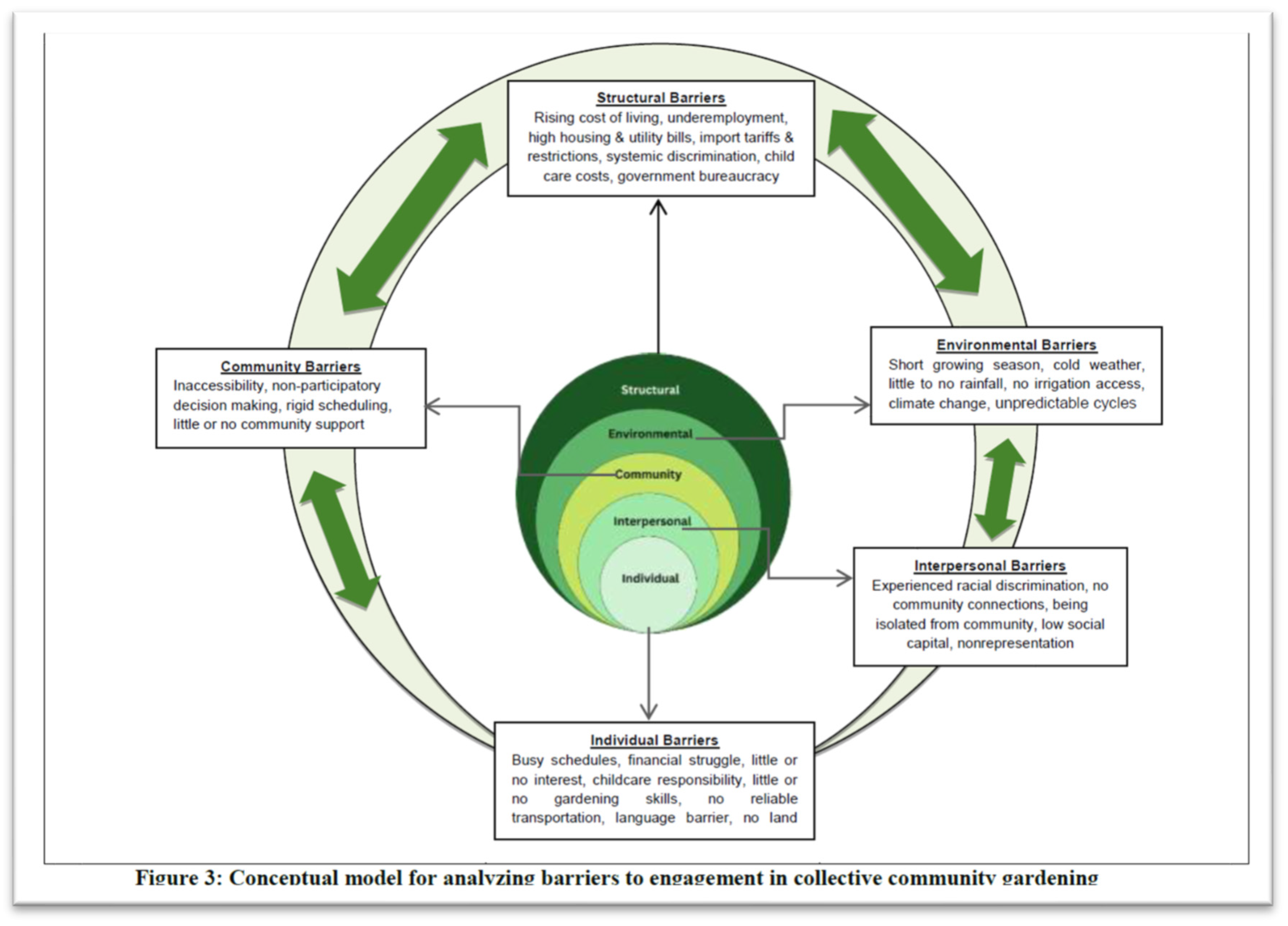

Background: Community gardens are increasingly popular in Canadian cities, serving as transformative spaces where immigrants can develop self-reliant strategies for accessing culturally familiar and healthy nutritious foods. Past research has demonstrated the embodied health and wellbeing benefits of gardening, however, Black immigrants, reported to be at higher risk of food insecurity are experiencing complex barriers to engagement in collective community gardens. Using a socio-ecological framework, this research explores barriers and facilitators to engagement of Black African immigrants in Alberta, Canada in collective community gardening. Methods: The study adopted a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach using mixed-methods to explore the individual and collective experiences, challenges, and meanings adopted by immigrants in connection to collective community gardens. Data collection included structured surveys (n=119) to assess general engagement, facilitators, and barriers, in-depth interviews (n=10) to explore lived experiences, and Afrocentric sharing circles (n=2) to probe collective perspectives. Participants were purposefully recruited through community networks within African immigrant-serving community organizations. Results: Our findings demonstrate how various levels of the socio-ecological model (SEM) – individual (knowledge about gardening, busy schedules, and transportation challenges); interpersonal (not seeing people of their ethnicity on the garden); community (distance to the garden); environmental (extreme weather); and structural (inflation, unemployment/underemployment, import restrictions, systemic racism, and government bureaucracy) barriers to most immigrants. These factors interact to limit the maximum engagement of African immigrants in collective community gardening. However, participants who accessed collective gardens reported significant benefits, including maintaining healthy foodways, knowledge exchange, growing social capital, and community connections that support overall wellbeing. Conclusions: This study contributes an accessible framework for understanding and addressing the complex barriers that limit engagement in community gardens for vulnerable communities, while highlighting opportunities for creating more inclusive and culturally responsive urban agriculture initiatives.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Research Design

Participant Recruitment

Ethics and Participant Protection:

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Survey Participants

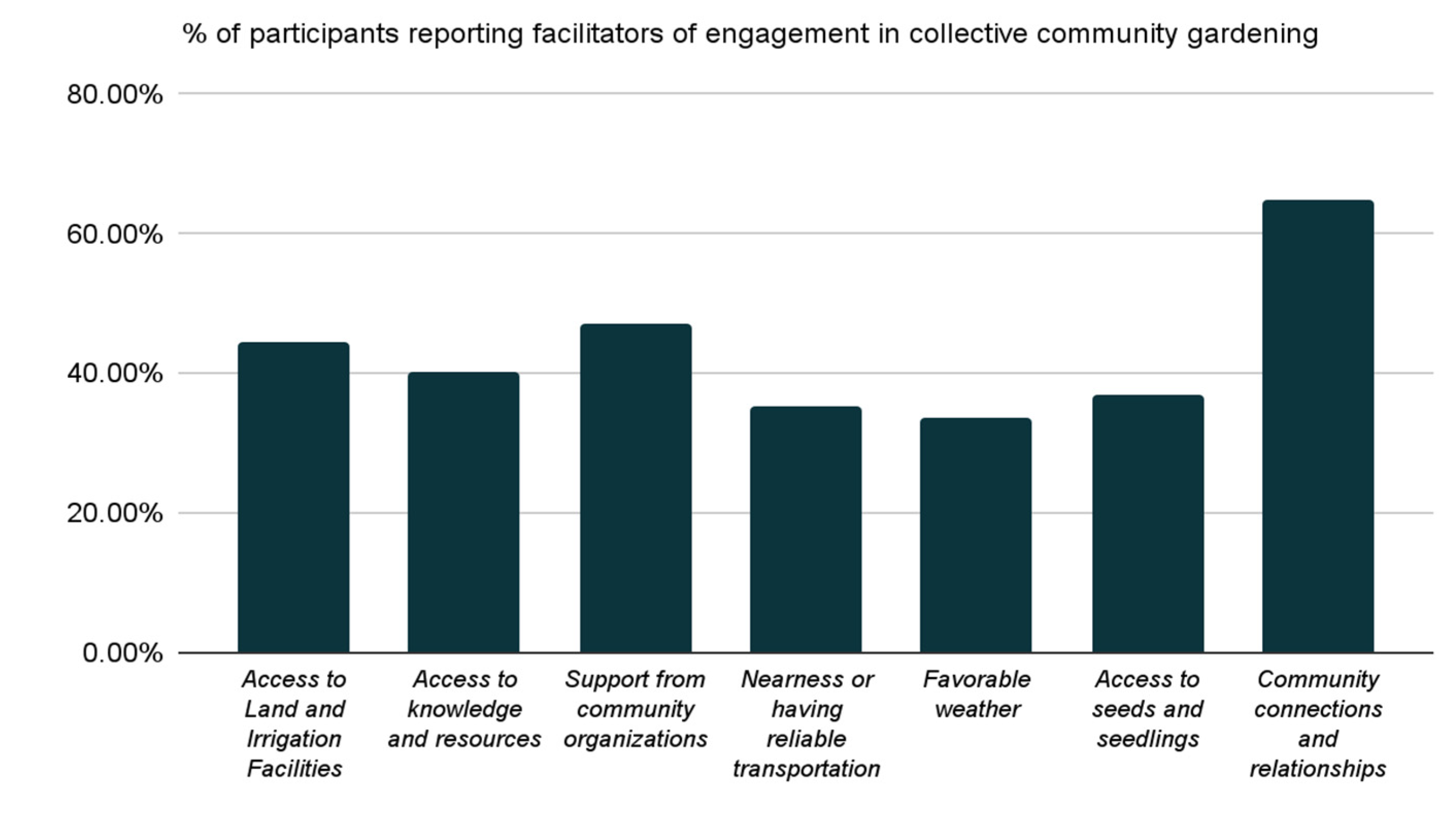

3.2. Facilitators of Engagement in Collective Community Gardening

I have been involved in collective community gardening. I love gardening a lot, unfortunately, I didn’t know about it earlier. It is one of the best things one can do, any community or any culture that treasures farming, they can thrive. They don’t need to depend on external help for survival. But if people become lazy, and they think that everything should come from their central government and sit down and wait for the government to do something, then it’s a recipe for disaster, for the people, or for the community. So yes, I have been involved, and I would love to continue. (IDI-06)

I can say it’s important to me, partly because these are the foods that I have grown up with, and also because I understand the nutritional value of some of these foods, especially the vegetables. (IDI-02)

Collective community gardening comes with a lot of benefits. To start with, you meet new people, people from different backgrounds and you form a community. We have different communities that we belong to. But you become part of a community, another community that is different from the ones that you’re familiar with. (IDI-05)

Because I once saw my friend bring tomatoes from a collective community garden, not the one from the shop. From a real garden. It made me feel like, “Wow, is this being done here?” I was wondering how people were able to plant these things. So that got me curious that if there is a way, then maybe I will try it and learn from it. (IDI-04)

In the collective community garden, because we have people from different countries, they come, and they’re like, “What are you growing there?” Vegetables that they’ve not seen, or they are like, “How do you prepare this?” Like when they see me grow a lot of kale, then they’re like, “What are you going to do with all that?”, then with that, we now start talking about, you know, how I use it, how I’ll prepare and store it. And yeah, so the collective community garden, it’s helped me learn quite a lot, meet people, and see how they are planting, you know, different ways of doing that because I learn something new. (IDI-02)

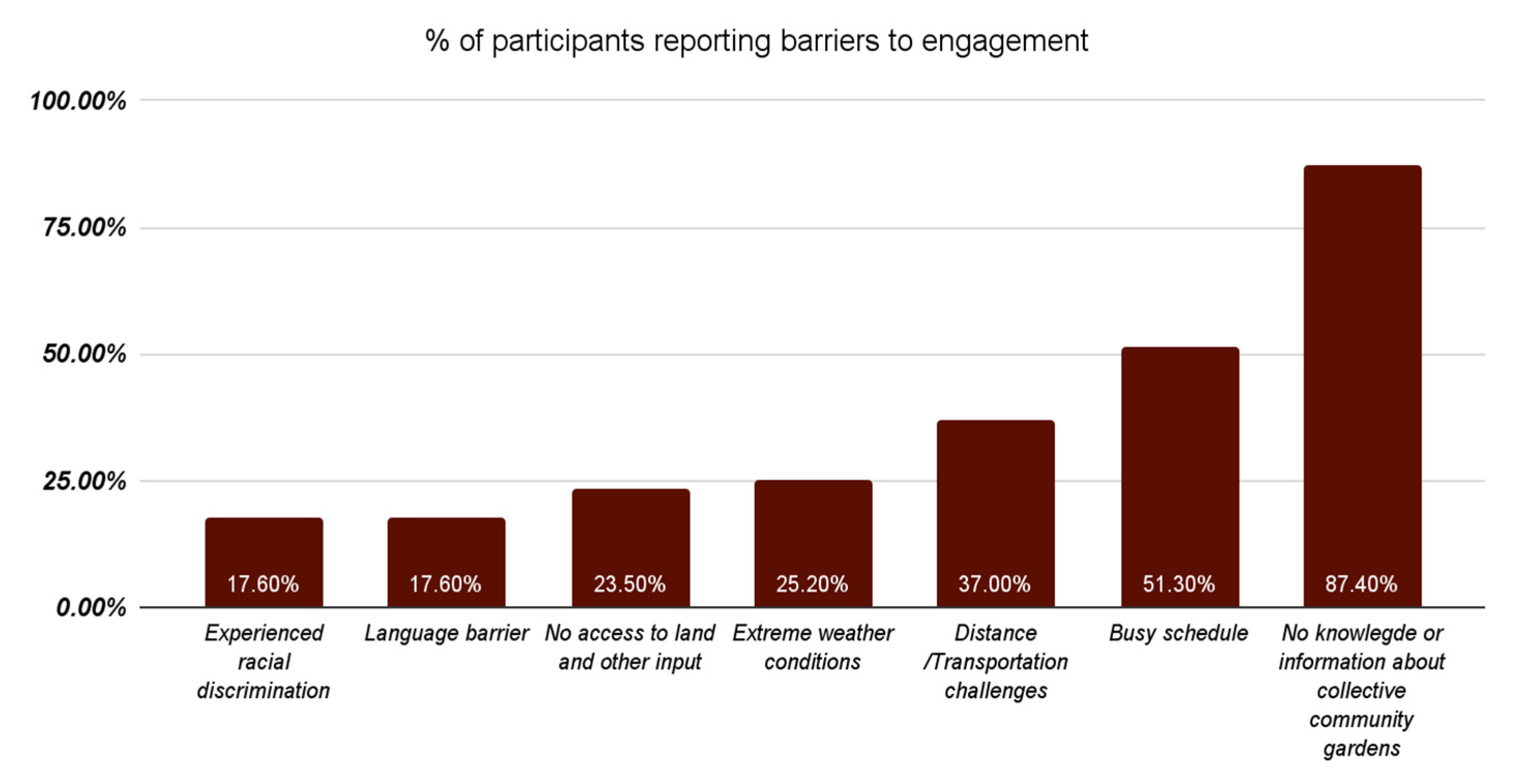

3.3. Barriers to Engagement in Collective Community Gardening

For those of us that are immigrants, one major barrier will be the time factor…. You see, many families, especially in the Black community, are working, trying to survive, and many of us have young ones, because we are immigrants from not more than 20 years. Let’s say from 15 years up, so many of them have new families, young children, so time would be a factor, the time they go to work, the time they go for their businesses. It could be a factor for people to come out. (IDI-03)

You know, people are thinking about how to pay their rent, how to pay their bills. So that can be one barrier, why people are not able to go and volunteer to do collective community gardening, because they are thinking about their bills, you know? Like for me, I work twelve hours. You work twelve hours. When you come home, you have to do a lot of work again, cook, take care of the kids, so sometimes it’s challenging. It’s a big challenge. (IDI-01)

If I can have the floor, I haven’t heard of community gardening actually, to be honest. I haven’t and that was probably why I as a person has not participated. But I mean, I would love to. I would love to see how that would work. I’m open to trying new things, and something I think it’s available. Of course, but why I haven’t done it is because I have never had an opportunity. In fact, I’m just hearing about it for the first time. (P-01 SC-2)

Like I said, I had no idea that a collective community garden exists in Edmonton, but if I had known that there was a community garden, I would have wanted to be part of it. But what would have hindered me from joining such initiatives would probably be my current engagement, which is my studies. I think my studies would be the – one of the major factors I would think that would hinder me from being a part of the community. But as someone who is a garden person, I would definitely make out time. (IDI-07)

My friend and I are the only Black people in that group. I don’t mind saying this, sometimes we’ve faced racial discrimination. Not from everybody. No. But a few people, some people. There are people who love us for who we are, no matter our colour. Such things happen. We face discrimination in the area of work. Sometimes you will see it, not all the leaders. But some of them, when we come, they will want us to do the bigger work, the work that requires more energy, but during harvesting we will be left out. Or others, are allowed to harvest whatever they want, but whenever it comes to people of colour like us, we are treated differently. But we still continue to go, to attend. That is where we now wish, oh, [pause] how we wish we have our own community garden. (IDI-03)

I know some people who are not able to come to the collective community gardens because they are far from where they live. Like where we farm, for instance, I think it’s maybe more than 20 kilometers away from where we live, so it depends on, do people have time to go to the community garden, and how close is it? I had to find a way to create beds and grow in my backyard. They are close enough, I’m able to water them when I need to, unlike the community garden, which is far away. I’m able to harvest when I need something, even preparing food in the kitchen, then I just go to the backyard and get that. So for me that’s the easiest place to farm, unlike the collective community garden. So that’s what I can say has also been a main challenge for me. (IDI-02)

You know, people can even have spaces that are closer to where they live. People can decide that, “Oh, I would belong to the one that is closer to my house,” So it would be more convenient. Besides creating awareness, convenience is also another thing. My husband, for instance, has never come to the collective community garden. Because we live in the Southwest, and the collective community garden is on the Northside. My husband does not like going far. And even when we offer to take him, he’s like, “No, I’m not going.” So some people would not want to maybe drive ten minutes, 15 minutes, you know, between ten and 20 minutes to get to the collective community garden. So convenience is a barrier for some people. (IDI-05)

There is a time I had wanted to join a certain collective community garden. But then I was like, “When it comes to the collective, how do people make decisions on the type of vegetables or fruits to grow?” “How do you decide, or how do you agree that we are going to grow this type of vegetable and not this other one?” Unless you are having people with similar tastes, at a collective garden, so that, you know, somebody might be like, “We are going to grow 20 heads of lettuce,” and then people will agree, because they like to eat salad. But then if you have a mixed group of people, I can imagine telling people from my community, the Kenyan community, like, “You are going to grow lettuce on half of the garden,” they will be like, “For what? [Laughs] I want to grow vegetables.” So collective community gardens, it really depends on who is involved, because we have different tastes, different desires. In a collective garden, how do people make decisions on what to grow? (IDI-02)

I am involved with a collective community garden, here in Edmonton, but you find that all we do is to garden Canadian food, or even other foreign foods, and not African, but European foods. Because I remember we planted lots of garlic. They bring different species of garlic from Germany, Bulgaria, although they will say, “This one is German, this Bulgarian’s flavour,” all those species of garlic. And others, maybe like tomatoes, different types of tomatoes, they have the Italian, they have the Mexican, and things like that, but nothing from Africa. (IDI-03)

Yeah, so I grow my own vegetables, I only buy vegetables when I’ve not been able to grow enough. Like last year I wasn’t around. I was visiting home, so we did not grow a lot of vegetables here which means that now we are buying. So I can’t wait for May to grow my vegetables. The growing season is short, from May to mid-September. Yes, if your plants go to October, you are taking a risk, because frost can come anytime, especially at night. So normally sukuma wiki can survive into maybe mid-October, but the other vegetables, once they are hit with the first frost, they just die. So again, when you are planting vegetables, you have to know what you must harvest by September and know what you can risk leaving in the garden. (IDI-02)

As immigrants, we are not able to afford a greenhouse unless we have to rent a place in the greenhouse, which is expensive. We have access to shared community spaces. But, you know, depending on the season, if there is rain, then you will get a good harvest there. If there’s no rain, you will not get any harvest, and if the rain is too much, it destroys away your harvest [Laugh] – like last year we planted our things in one of the collective community garden, and you know, there was a heavy storm, hailstorms that destroyed everything that we planted there. It was a big loss. [Laughs] Yeah, so that brings another distress for the collective community garden. So the greenhouse, it’s necessary, so that if there is a big storm, or whatever, hailstorm, it won’t be affected. (P01 SC 1)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartwig, K.A.; Mason, M. Community Gardens for Refugee and Immigrant Communities as a Means of Health Promotion. J. Community Heal. 2016, 41, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, C.; Grieger, J.A.; Kalamkarian, A.; D’onise, K.; Smithers, L.G. Community gardens and their effects on diet, health, psychosocial and community outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegner, A.; Sowerwine, J.; Acey, C. Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hite, E.B. , et al., Intersecting race, space, and place through community gardens: Race, space, and place. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 2017. 41(2): p. 55-66.

- Drake, L.; Lawson, L.J. Results of a US and Canada community garden survey: shared challenges in garden management amid diverse geographical and organizational contexts. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 32, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerodetti, N.; Foster, S. Migrant gardeners, health and wellbeing: exploring complexity and ambivalence from a UK perspective. Heal. Promot. Int. 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, C. , “ Rooted in Community”: The Importance of Community Gardens.. Liberated Arts: a journal for undergraduate research, 2021. 8(1).

- Minkoff-Zern, L.-A.; Walia, B.; Gangamma, R.; Zoodsma, A. Food sovereignty and displacement: gardening for food, mental health, and community connection. J. Peasant. Stud. 2023, 51, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, I.; Beilin, R. Community Gardens: Space for Interactions and Adaptations. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 36, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, P.A.; Hamada, J.L.; Rdesinski, R.; Sprager, L.; Nichols, K.R.; Liu, B.Y.; Pelayo, J.; Sanchez, M.A.; Shannon, J. Impact of a Community Gardening Project on Vegetable Intake, Food Security and Family Relationships: A Community-based Participatory Research Study. J. Community Heal. 2011, 37, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, E.; Otoadese, D.; Mori, K.; Chinedu-Asogwa, N.; Kiplagat, J.; Jirel, B. Exploring neighborhood transformations and community gardens to meet the cultural food needs of immigrants and refugees: A scoping review. Heal. Place 2025, 92, 103433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, E. “You Can't Say You're Sovereign if You Can't Feed Yourself”: Defining and Enacting Food Sovereignty in American Indian Community Gardening. Am. Indian Cult. Res. J. 2017, 41, 31–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidro, J. , et al., Beyond Food Security: Understanding Access to Cultural Food for Urban Indigenous People in Winnipeg as Indigenous Food Sovereignty. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 2015. 24(1): p. 24-43.

- Idemudia, S.I. and A. Adedeji, Well-Being and Culture: An African Perspective, in Wellbeing Accross the Globe - New perspectives, concepts, and geography. 2023, intechopen.

- Lindner, C. , “Rooted in community”: The importance of community gardens. 2021, Liberated Arts.

- Charles-Rodriguez, U.; Aborawi, A.; Khatiwada, K.; Shahi, A.; Koso, S.; Prociw, S.; Sanford, C.; Larouche, R. Hands-on-ground in a new country: a community-based participatory evaluation with immigrant communities in Southern Alberta. Glob. Heal. Promot. 2023, 30, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.; Minniss, F.R.; Somerset, S. Refugees Connecting with a New Country through Community Food Gardening. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2014, 11, 9202–9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, D.; Gray, T.; Manohar, N.; Kingsley, J.; Bailey, A.; Pettitt, P. Identifying Key Benefits and Characteristics of Community Gardening for Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. Heal. Soc. Care Community 2023, 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, T.; Costa, J.; Santos, O.; Sousa, J.; Ribeiro, T.; Freire, E. Evidence on the contribution of community gardens to promote physical and mental health and well-being of non-institutionalized individuals: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0255621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, C.; Lestrat, K.E.; Vatanparast, H. Food Security Interventions among Refugees around the Globe: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyg, P.M.; Christensen, S.; Peterson, C.J. Community gardens and wellbeing amongst vulnerable populations: a thematic review. Heal. Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, D.; Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwartnik-Pruc, A.; Droj, G. The Role of Allotments and Community Gardens and the Challenges Facing Their Development in Urban Environments—A Literature Review. Land 2023, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, J.K.; Gounaridis, D.; Newell, J.P. Does urban agriculture lead to gentrification? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, K.L. Modeling community garden participation: how locations and frames shape participant demographics. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 40, 1067–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, K., T. M. Reischl, and J.O. Allen, Community gardening, neighborhood meetings, and social capital. Journal of Community Psychology, 2010. 38(4): p. 498-514.

- Kingsley, J., E. Foenander, and A. Bailey, “It’s about community”: Exploring social capital in community gardens across Melbourne, Australia.. Urban forestry & urban greening, 2020. 49(126640).

- Brooks, S. and G. Marten, Green Guerillas: Revitalizing Urban Neighborhoods with Community Gardens (New York City, USA), in Eco Tipping Points Project. 2012, Eco Tipping Points Project: New York.

- Gregory, C.A. and A. Coleman-Jensen, Food insecurity, chronic disease, and health among working-age adults, in Economic Research Report #235. 2017, AgEcon Search: USA. p. 32.

- Lampert, T.; Costa, J.; Santos, O.; Sousa, J.; Ribeiro, T.; Freire, E. Evidence on the contribution of community gardens to promote physical and mental health and well-being of non-institutionalized individuals: A systematic review. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0255621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hordyk, S.R.; Hanley, J.; Richard, É. "Nature is there; its free": Urban greenspace and the social determinants of health of immigrant families. Health Place 2015, 34, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, C. , Rooted in Community: The importance of community gardens. Liberated Arts: A Journal for Undergraduate Research, 2021. 8(1).

- Jefferies, K.; Richards, T.; Blinn, N.; Sim, M.; Kirk, S.F.; Dhami, G.; Helwig, M.; Iduye, D.; Moody, E.; Macdonald, M.; et al. Food security in African Canadian communities: a scoping review. JBI Évid. Synth. 2021, 20, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Onyango, E. Intersections of race, COVID-19 pandemic, and food security in Black identifying Canadian households: A scoping review. 2023, 10, 3–34. [CrossRef]

- PROOF, New data on household food insecurity in 2023. 2024, PROOF / University of Toronto.

- Elshahat, S.; Moffat, T.; Iqbal, B.K.; Newbold, K.B.; Gagnon, O.; Alkhawaldeh, H.; Morshed, M.; Madani, K.; Gehani, M.; Zhu, T.; et al. ‘I thought we would be nourished here’: The complexity of nutrition/food and its relationship to mental health among Arab immigrants/refugees in Canada: The CAN-HEAL study. Appetite 2024, 195, 107226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chang, J.J.; Xian, H.; Qian, Z.; Barnidge, E. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Association Between Food Security and Depressive Symptoms Among Adult Foreign-Born Immigrants in the US: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Heal. 2022, 25, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, F.; Khanlou, N.; Tamim, H. South Asian populations in Canada: migration and mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 154–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohani, S. , et al., “If You Say You Have Mental Health Issues, Then You Are Mad”: Perceptions of Mental Health in the Parenting Practices of African Immigrants in Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 2020. 52(3): p. 47-66.

- Zutter, C.; Stoltz, A. Community gardens and urban agriculture: Healthy environment/healthy citizens. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Nurs. 2023, 32, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Social Determinants and Inequities in Health for Black Canadians: A Snapshot.. 2020, Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, Canada. p. 1-14.

- Public Health Association of Canada, Inequalities in health of racilized adults in Canada, in Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative. 2022, Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, Canada. p. 1-4.

- Statistics Canada, Study: A labour market snapshot of Black Canadians during the pandemic. 2021.

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D. Translating Social Ecological Theory into Guidelines for Community Health Promotion. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. REVIEW OF COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M.; Wallerstein, N. 3. Improving Health through Community Organization and Community Building: Perspectives from Health Education and Social Work. In Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare; Minkler, M., Ed.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 37–58. ISBN 978-0-8135-5314-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S. and E.G. Guba, Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, 1985: p. 289-331.

- Braun, V. and V. Clarke, Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006. 3(2): p. 77-101.

- Elshahat, S.; Moffat, T.; Iqbal, B.K.; Newbold, K.B.; Gagnon, O.; Alkhawaldeh, H.; Morshed, M.; Madani, K.; Gehani, M.; Zhu, T.; et al. ‘I thought we would be nourished here’: The complexity of nutrition/food and its relationship to mental health among Arab immigrants/refugees in Canada: The CAN-HEAL study. Appetite 2024, 195, 107226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghose, R.; Pettygrove, M. Urban Community Gardens as Spaces of Citizenship. Antipode 2014, 46, 1092–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, E.; Olukotun, M.; Olanrewaju, F.; Kapfunde, D.; Chinedu-Asogwa, N.; Salami, B. Transnationalism and Hegemonic Masculinity: Experiences of Gender-Based Violence Among African Women Immigrants in Canada. Women 2024, 4, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke-Ihejirika, P., B. Salami, and A. Karimi, African immigrant women’s transition and integration into Canadian society: Expectations, stressors, and tensions. Gender, Place & Culture,, 2019. 26(4): p. 581-601.

- Minkoff-Zern, L.A. , Knowing “good food”: Immigrant knowledge and the racial politics of farmworker food insecurity. Antipode, 2014. 46(5): p. 1190-1204.

- Leung, J. Community garden as a nature-based solution to address climate change through adaptation and mitigation. LinkedIn. 2023.

| Survey participant demographics, n=119 | |

|

Gender, n (%) Female Male |

65 (54.6) 54 (45.4) |

| Year Born, median (range) | 1986 (1948 - 2006) |

| Year Arrived to Canada, median (range) | 2014 (1978 - 2024) |

|

Employed, n (%) Yes No |

66 (59.4) 45 (40.6) |

|

If yes, do you have more than one job? n (%) Yes No |

13 (19.7) 53 (80.3) |

|

Highest Level of Education, n (%) No formal education Elementary/Primary complete High School Post-secondary |

1 (0.8) 3 (2.5) 29 (24.4) 86 (72.2) |

|

Marital status, n (%) Never Married (Single) Married Common Law Separated/widowed |

50 (44.2) 56 (49.5) 2 (1.7) 5 (4.4) |

|

Household size, n (%) Single person 2-5 people More than 5 |

11 (9.2) 43 (36.1) 65 (54.6) |

|

Household Structure, n (%) Female-centered Male centered Nuclear Extended |

28 (23.5) 21 (17.6) 54 (45.4) 16 (13.4) |

|

Common types of gardening, (%) Home/backyard gardening Collective community gardens Community gardens No identified |

49 (41.2) 44 (37.0) 33 (27.7) 22 (18.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).