1. Introduction

Environmental leadership has become increasingly relevant as a tool for advocacy, mobilization, and the promotion of social and environmentally just realities. Also referred to as sustainability leadership, it addresses complex challenges by integrating political, economic, social, and environmental dimensions [

1,

2,

3]. In this context, the construction of knowledge from the local level emerges as a key process to promote conservation strategies that respond to the specific socio-environmental realities of each territory.

One pressing issue is the degradation of natural ecosystems, particularly wetlands, which face biodiversity loss and environmental deterioration [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. These challenges require not only the implementation of public policies, but also the strengthening of local capacities through participatory processes that value traditional knowledge and community experience. Rural communities, as the main guardians of their territories, possess empirical knowledge that, when combined with academic approaches, enhances sustainable environmental management.

The area that includes Chautengo Lagoon and Pico del Monte community in southern Mexico exemplifies these challenges, suffering from deforestation, overfishing, pollution, and unsustainable agricultural and tourism activities. Despite existing activism, weak environmental awareness among local communities has limited conservation efforts. This study explores the role of community environmental leadership as a strategy to enhance local environmental governance through collaboration among activists, rural communities, local authorities, and academia.

1.1. Leadership and Sustainability

Leadership is commonly defined as a set of qualities, behaviors, skills or processes through which individuals influence groups to achieve common goals [

11,

12]. Various leadership styles have been identified, including situational, servant, transactional, transformational, autocratic, democratic, charismatic, and distributed leadership [

13,

14]. Of relevance to environmental initiatives are transactional leadership, which focuses on power and goal-setting, and transformational leadership, which fosters commitment and long-term collaboration [

14,

15].

Liefferink and Wurzel [

16] categorize environmental leaders into four types: structural, entrepreneurial, cognitive, and exemplary, while Liao [

17] highlights ecological transformational leadership, sustainable and moral leadership promote sustainability va-lues, all of them are essential for fostering environmental actions. Boeske [

18] revealed that sustainability, sustainable and environmental leadership share values, attitudes, moral and ethical beliefs.

Four key factors influence environmental leadership: culture, governance, empo-werment, and motivation. Culture shapes social consciousness and can either drive or limit environmental change [

2]. Governance models that blend various styles can enhance sustainability and facilitate policy implementation [

19,

20]. Empowerment arises from participation and local knowledge, fostering autonomy in decision-making [

21], while motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic, plays a crucial role in achieving sustainability goals [

22].

1.2. Sustainable Development and Community Leadership

The concept of sustainable development, introduced in the Brundtland Report, emphasizes meeting present needs without compromising future generations [

23]. Sustainability is defined as the harmonization of economic, social, and environmental dimensions, requiring value-based management that respects ecological limits [

24]. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), underscores the need for local action and multi-stakeholder collaboration [

25]. This study aligns with SDG 15 (Life on Land) by promoting sustainable leadership models that integrate community participation, local governance, and academic support [

26].

1.3. Environmental Education and Leadership Training

Training community environmental leaders is fundamental for fostering grassroots conservation efforts. Environmental education programs aim to raise awareness, build values, and develop skills for sustainable living [

27,

28].

Due to its importance in constructing knowledge through experience in problem-solving, this work is complemented by the theoretical foundations of Tovar Galvez [

29] and the methodology for designing a training program by Nieto & Buendia [

30], who propose a four-stage process for designing environmental leadership programs: (1) Contextualization, which links training to local environmental issues; (2) Structuring, which defines content and methodologies; (3) Programming, which organizes logistics and re- sources; and (4) Evaluation, which assesses learning outcomes.

Learning models from Piaget's cognitivism, Vygotsky's socio-constructivism, and Freire's critical pedagogy suggest that experience-based learning and participatory me-thodologies are effective in shaping environmental leaders [

31,

32].

Environmental leadership plays an essential role in environmental preservation by developing strategies for its conservation [

33]. Hence, it is important to strengthen its knowledge. The following studies reveal significant insights into the nature of environmental leadership in different geographical and cultural contexts (

Table 1). All of them highlight the relevant role that leaders play in promoting social change and sustainability.

A key challenge is integrating local knowledge into leadership development [

26]

. It is also important that the training of environmental leaders generates proposals from a local perspective integrating traditional knowledge [

48,

49,

50,

51]. This aligns with Mexico's Environmental Education Strategy for Sustainability, which promotes the development of environmental leaders capable of addressing the country's sustainability challenges [

52].

1.4. Research Objective

This study examines the epistemological, theoretical, and methodological foundations for training community environmental leaders within the context of sustainable development, emphasizing the construction of local knowledge as a critical component of community empowerment. It documents an initiative in communities near the Chautengo Lagoon, Guerrero, Mexico, where nineteen local leaders successfully mobilized 1,500 people for a cleanup campaign. The findings contribute to the understanding of contextualized environmental leadership training and its potential for replication in similar ecological and social settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Area and Context of Study

The study was conducted in Chautengo Lagoon, located in the state of Guerrero, Mexico (16º 35' 39" – 16º 38' 36" N; 99º 08' 25" – 99º 02' 48" W), covering 32.5 km². Along its border, there is an area of vegetation colonized by Rhizophora mangle, Avicennia nitida, Laguncularia racemosa and Conocarpus erectus (red, black, white and buttonwood mangrove respectively). In addition to Spartina alterniflora and Arecaceae (coconut palm).

The study population comprised residents from eight communities: El Medano, Pico del Monte, Los Tamarindos, Chautengo, Llano de la Barra, Estero del Marquez, Las Peñas, and La Fortuna, totaling approximately 3,136 inhabitants (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) [

53]. Environmental degradation, including mangrove deforestation, overfishing, and pollution, threatens local livelihoods, necessitating urgent community-led conservation initiatives. The primary economic activities in these municipalities include agriculture, livestock farming, fishing, aquaculture, commerce, and tourism. The region has a warm, sub-humid climate, characterized by summer rainfall [

54,

55,

56].

2.2. Type of Research and Procedure

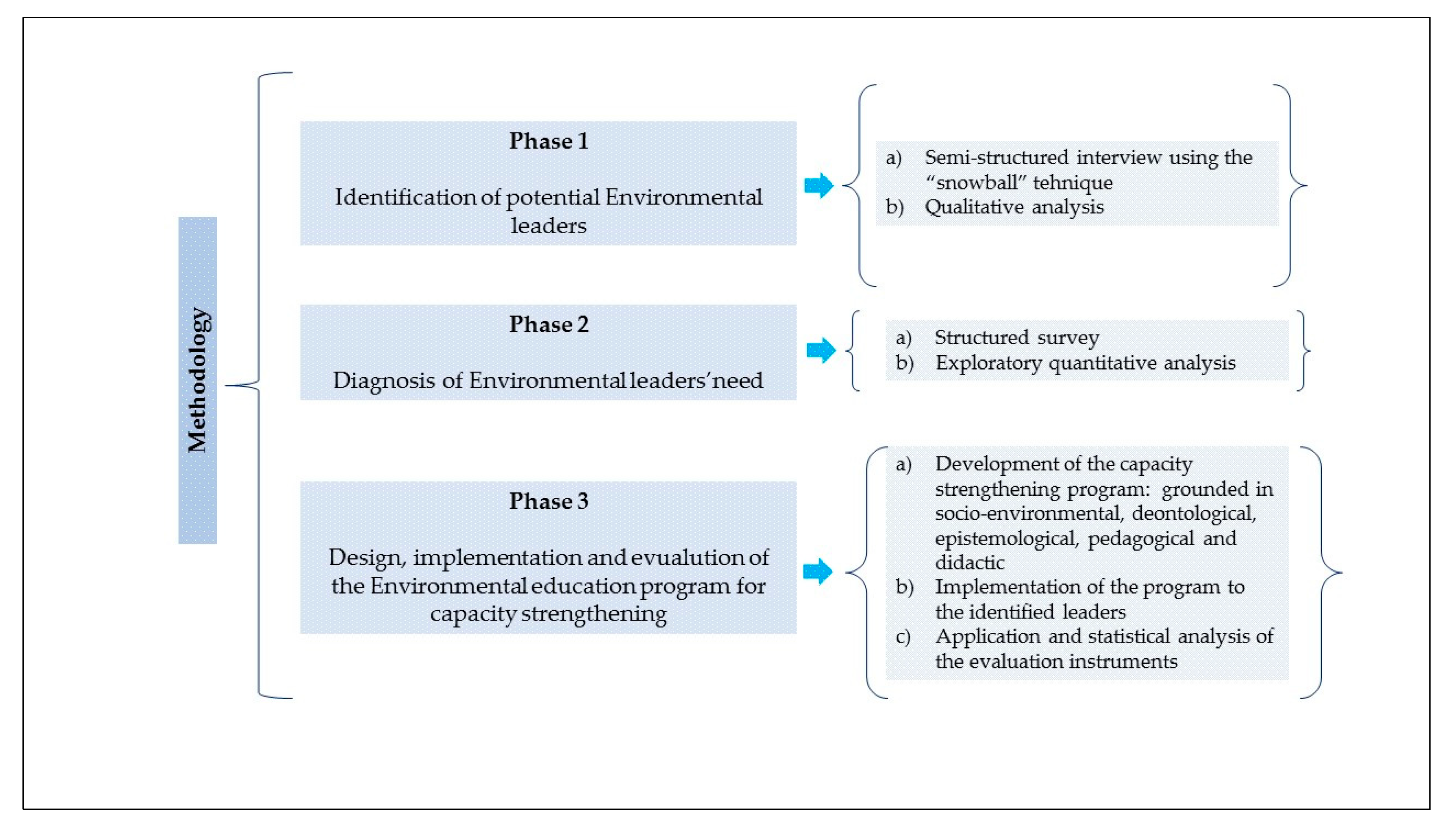

The methodological approach used was mixed, descriptive, and cross-sectional. The research was carried out in three phases, from November 2021 to September 2022 (

Figure 1).

2.3. Phase 1. Identification of Potential Environmental Leaders

An exhaustive documentary review was conducted to identify existing studies on environmental leadership training [

1,

38,

39,

40,

57,

58]. An immersion process was also conducted, consisting of five field visits to Pico del Monte. During these visits, it was possible to explore the characteristics of the place, as well as the ways and lifestyles of the population. The selection of this community was primarily based on its proximity to the Chautengo Lagoon.

During this phase, 12 semi-structured interviews were conducted, using the "snowball" technique to identify the community leaders, as well as their characteristics and the activities they were carrying out in the community and its surrounding areas. Data coding and analysis were carried out using the Atlas ti software program.

After identifying the twelve environmental leaders, a community meeting was organized with fishing cooperatives and residents. During the meeting, topics such as

climate change, environmental challenges, and changes in mangrove area over the years 1981, 2010 and 2020 were presented. Data from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity by its acronym in Spanish (CONABIO) [

7,

26,

59,

60,

61]

was used to support the discussion.

At the explicit invitation of other leaders from the region, and considering the importance of this information, it was also presented to the presidents of the fishing cooperatives from the communities of Chautengo, Llano de la Barra, La Fortuna, Las Peñas and El Medano in the Chautengo community, as well as to residents of Llano de la Barra community and the main town of the municipality of Cuautepec.

It is worth mentioning that, on the proposal of this initial group, leaders proposed a cleanup campaign, mobilizing municipal authorities and private-sector sponsors to remove solid waste from the lagoon. This provided an opportunity to observe leadership behaviors in action.

2.4. Phase 2. Diagnosis of Training Needs of Environmental Leaders

Nineteen leaders from the cleanup campaign were invited to participate in an environmental training program. Participants engaged in reflective exercises on local environmental problems and their alignment with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), identifying the specific knowledge gaps and skillsets needed to strengthen their leadership roles.

All of them expressed their agreement with the proposal. We proceeded to the application of 19 structured surveys with a Likert scale, with five intervals ranging from "sometimes" to "always," which allowed us to obtain a Training Needs Diagnosis (TND); this revealed aspects such as environmental activities they had undertaken, their level of organization, their relationship with their community, and of course, which personal areas they believed should be developed and strengthened for better environmental performance. The data obtained was processed using the SPSS software, version 25.

2.5. Phase 3. Development of the Program to Strengthen Capacities

The training program was structured based on Nieto and Buendía’s framework [

30] and tailored to the socio-cultural context of the region, fostering the co-construction of knowledge between facilitators and community leaders.

Contextualization: Findings from Phase 1 guided the curriculum design, ensuring relevance to local leadership styles and environmental issues.

Structuring: Content was aligned with training needs, incorporating the historical, economic, and ecological context [

26].

Programming: Four four-hour training sessions were scheduled at a local

public educational facility. Sessions integrated prior knowledge exploration and interactive strategies to address the climate crisis.

Evaluation: After program completion, 12 surveys (adapted from Stocking et al. [

62]) were conducted to assess: relevance of content, facilitator expertise, session duration, material effectiveness, and perceived impact on leadership skills.

3. Results

In this section, we present the results to be considered in the training of environmental leaders.

3.1. Identification of the Environmental Leaders

The interviews' results allowed us to identify people in three different occupations: fisherman (3), service provider (5), and public servant (4) who showed concern for and took action to care for the environment.

3.2. Presentation of Environmental Problems in the Communities

The presentation of environmental issues in the communities helped raise awareness not only among the leaders and presidents of fishing cooperatives but also among the rest of the attending population. This resulted in the addition of leaders from the communities of Chautengo (4), Llano de la Barra (3), Los Tamarindos (2), El Médano (1) from the municipality of Florencio Villarreal; La Fortuna (1) and Las Peñas (2) from the municipality of Copala; and Estero del Marquéz (1), which belongs to the municipality of Cuautepec, which added to the five from the community of Pico del Monte, gave us a total of 19 people interested in strengthening themselves as community environmental leaders.

3.3. Cleanup Campaign

Although the cleanup campaign was not the main purpose (it will be reported in another document) of this environmental education process, it did allow us to observe how the 19 people identified as leaders organized and mobilized around 1500 people from eight communities adjacent to the Chautengo Lagoon, as well as various educational ins-titutions in the region. This campaign lasted one week. The leaders were responsible for gathering the population in public spaces (sports fields) in their respective localities; subsequently, they divided the population by gender and occupation and assigned the areas based on their complexity and accessibility (see

Figure 2).

3.4. Training Needs of Environmental Leaders

The results of the needs assessment showed that the leaders have organizational skills but with areas for improvement; 95% of the leaders expressed the need for training in the following environmental topics: urban solid waste management (18%), ecological conservation (10%), communication (10%), recycling (8%), organic composting (7%), and drafting official documents (5%).

These topics were grouped into three guiding themes, which enabled the establishment of the content of the capacity-building program: environmental issues, management for sustainable development, and environmental education for sustainability.

3.5. Training Program for the Development of Environmental Competencies

With the formal detection of the training needs of individuals selected as environmental leaders, a training program was developed and divided into four sessions.

3.5.1. First Session, August 27, 2022

Description: Participants collectively reflected on global environmental issues and their local impacts. Concepts such as planetary crisis, climate change, and global warming were discussed. It was shown how to calculate the ecological and carbon footprint, along with recognizing the renewable resources available in each participating locality. Success stories from other places in Mexico and other countries were shared.

Findings: Attendees reflected their direct and indirect roles in modifying their natural environment by overexploiting fishing resources, deforesting mangroves, or undertaking actions contributing to the silting of the lagoon, resulting in fish mortality, among other problems. They also acknowledged that the population is always seeking economic support and that raising awareness will be a complex but not impossible task.

3.5.2. Second Session, September 3, 2022

Description: The session focused on urban solid waste (garbage), including the description, origin, and classification of plastics and microplastics. Emphasis was placed on the reuse of materials, especially cases involving polystyrene foam and plastic that release contaminating particles when exposed to different temperatures. Additionally, the session highlighted the risks posed to animals that mistake these materials for food. Another significant issue of concern was the socio-environmental problems associated with open-air garbage dumps and their implications for communities.

Findings: The leaders discussed actions that communities can undertake to address or mitigate these negative impacts. They proposed organizing workshops to promote waste collection and contribute to environmental change, emphasizing the slogan "It's not my trash, but it's my planet".

Finally, they expressed their interest in forming a non-profit organization aimed at fostering social and environmental change in the communities.

3.5.3. Third Session, September 10, 2022

Description: The session focused on the ecological importance of mangroves. It included discussions on the differences between reforestation and rehabilitation processes, as well as the necessary steps to carry out a safe restoration. Participants were educated about the significance of sanitation efforts and proposed assisted reforestation guided by professionals. An on-site practical demonstration was conducted with Californian red worms under the guidance of a professional composter.

Findings: The session concluded with plans to launch a mangrove reforestation campaign. Cattle manure from the region was suggested as an organic fertilizer. Additionally, participants agreed to visit Ventanilla, a town in the neighboring state of Oaxaca, to gather information and seek advice on a mangrove reforestation project recognized as a "successful" case.

3.5.4. Fourth Session, September 24, 2022

Description: The session focused on developing critical thinking and assertive communication skills, emphasizing the importance for leaders to reflect on the environmental problems affecting their communities and engaging actively with all levels of government and administrative agencies. Participants were guided on drafting various types of documents to formally request attention to their petitions, including official letters, letters, memorandums, posters, and assembly minutes. The session concluded with a reflection on the practical usefulness of the information covered during the four training sessions, as well as the perspectives on what would follow in their communities with their respective projects.

Findings: To continue with their planned actions, the leaders decided to form a committee consisting of a president, secretary, treasurer, and two members. They aim to formalize this committee as a civil association named "Environmental Leaders for Sustainability in the Costa Chica region." As their first step, they will seek legal assistance from a lawyer and guidance from a civil association called Tlali for advice on the formation and official registration process.

Another action agreed upon was to invite their commissioners to undertake cleanup campaigns, conduct awareness talks, and invite stakeholders engaged in environmental initiatives. To facilitate open and fluid communication, they decided to create a WhatsApp group and add all individuals interested in participating and promoting actions among all the communities involved.

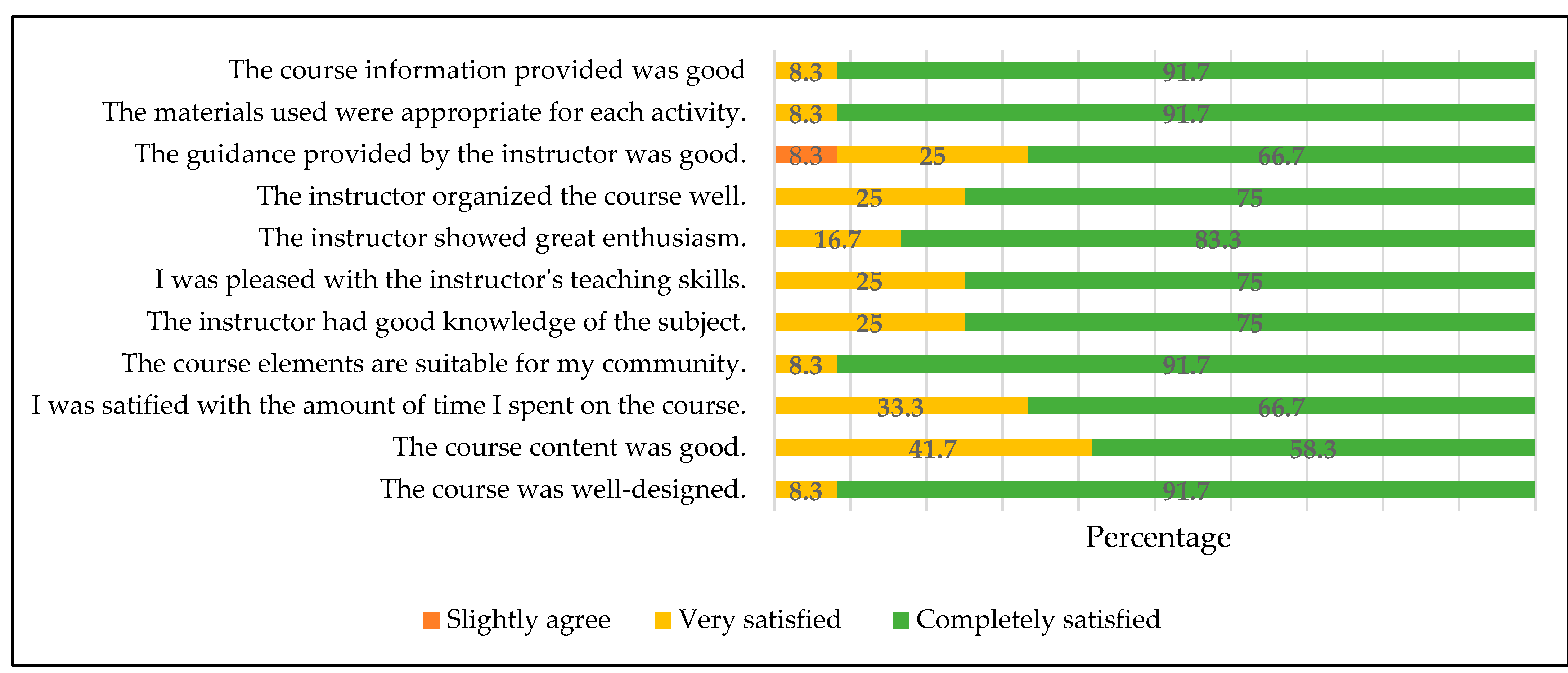

3.6. Evaluation of the Environmental Leaders Training Program in the Context of Sustainable Development

The training program was evaluated by the environmental leaders who attended all four sessions (63%). They were completely satisfied with the course design (90%), the information provided during the sessions (92%), and the materials used in each activity (92%). Likewise, they expressed high satisfaction with the content of the topics covered, with (42%) indicating they were very satisfied and (58%) indicating they were completely satisfied. Regarding the facilitator´s knowledge demonstrated during the course, they were very satisfied (23%) and completely satisfied (71%). They also agreed with the amount of time dedicated to the course for the target population, with (33%) very satisfied and (67%) completely satisfied (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The following is a description of the general findings identified during the environmental leadership training process:

Three types of environmental actors were identified based on their occupations: fishermen, service providers, and public servants. Each of them has developed their leadership by addressing different environmental issues and positioning themselves within situational leadership. The figure of the local fisherman, in particular, stands out for their deep concern for "their lagoon,” which is the main source of livelihood for the communities. This deep-rooted connection to the land and water embodies local ecological knowledge and inspires the adoption of sustainable practices within these communities.

The public servants, through their roles, promote compliance with environmental policies, aiming to improve ecosystem health and sustainability. For their part, the participating public service providers tirelessly work on environmental education for visitors, advocating for more responsible environmental practices. They have witnessed firsthand the negative effects of unsustainable tourism, especially concerning improper waste management—highlight the importance of community-led conservation initiatives.

The study emphasizes the significance of environmental leadership and allows us to witness the transition from an initial transactional leadership to a

situational transformational style. This evolution was grounded in the co-construction of knowledge between community members and facilitators, where local experiences and traditional practices were integrated with sustainable development principles. Unlike previous studies in Europe and Asia—such as Springer, Walkowiak, and Bernaciak [

19] in Poland and Xuejiao Niu et al. [

22] in Taiwan—this study identifies both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations- driving environmental leaders in a Latin American context.

Moreover, our findings align with Zhu and Huang [

47] and Li et al. [

64], who demonstrated that transformational leadership in environmental settings fosters community-wide behavioral change; enhances environmental social governance and strengthens social responsibility [

47]. Additionally, transformational leadership along with GTL, ESTL, SL, GSL have been shown to improve pro-environmental behaviors [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. This was particularly evident during the cleanup campaign, where collective action was catalyzed by the leaders’ passion and commitment, reinforcing the connection between leadership charisma and environmental motivation. This outcome also parallels the results of Hu et al. [

64], who found that sustainable leadership in Taiwanese manufacturing companies enhanced employees' environmental commitment.

The study confirms the effectiveness of contextualized pedagogical interventions in fostering local environmental awareness and community engagement, as highlighted by Barreto et al. [

65] in Bogotá and Selby et al. [

66] in Costa Rica. By embracing participatory learning and respecting community knowledge, the training program created a collaborative space where local leaders became co-creators of environmental solutions rather than recipients of external knowledge. Similarly, the findings align with Jones et al. [

67], who documented how environmental leadership programs in the UK’s Our Bright Future initiative empowered participants to drive meaningful ecological change.

Additionally, the study supports research by Monroe et al. [

39], which emphasizes school-community collaboration in promoting environmental action. The integration of Training Needs Diagnosis (TND) in this study aligns with Tovar-Gálvez [

29] and Hintz and Lackey [

57], demonstrating its value in enhancing community participation and addressing local environmental challenges.

This study contributes to the theory of environmental leadership by integrating situational, transformational, and community-based leadership approaches within a Latin American environmental context. Future research should explore: the long-term impact of environmental leadership training on policy implementation and behavioral change, and the role of gender and generational differences in shaping environmental leadership styles.

One key goal of this training process was to ensure that participants acquired a solid profile that would guarantee the continuity of their role as environmental leaders, as proposed by Torres [

40]; he also suggests that with the acquired knowledge, participants can identify socio-environmental issues, beginning with a broad approach and subsequently prioritizing specific problems within each community.

5. Conclusions

This community-centered environmental leadership training initiative, framed within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, began with an immersion process that allowed for direct engagement with local communities and the observation of their environmental challenges and initiatives. As a result, a working group was established to enhance knowledge and skills related to sustainable practices. This initiative fostered intersectoral collaboration between local governments, civil society, and the private sector, leading to tangible actions, such as a cleanup campaign that removed one ton of plastic waste, generating economic benefits for community development.

The subsequent phase focused on the design and implementation of a community environmental leadership training program, tailored to the socio-cultural and ecological characteristics of the region. This program promoted community empowerment, not only among direct participants but also within the broader population. Its implementation successfully engaged municipal governments, civil society organizations, and private sector actors, reinforcing the importance of multi-stakeholder initiatives in environmental governance. The interinstitutional commitment materialized through a cleanup campaign, where the recovered plastic waste was commercialized, generating revenue for community improvements.

A key contribution of this study is the development of a conceptual framework for community environmental leadership, which integrates training methodologies in environmental sciences and sustainability. This framework fosters action-oriented competencies and community empowerment, equipping local actors to become agents of environmental change. The establishment of a civil committee, Environmental Leaders for Sustainability in the Costa Chica Region, marks a critical step toward long-term environmental governance and legal representation to advocate for the region’s ecological stability. By promoting a community-led model, this training initiative highlights the potential of local leadership to drive sustainability.

The evaluation process demonstrated a significant increase in awareness, leadership capacity, and mobilization among participants, highlighting the effectiveness of environmental education in fostering sustainable practices. The findings underscore the need for contextualized environmental education (EE) that integrates traditional knowledge, critical thinking, and a sense of ownership, supported by academically grounded methodologies.

We consider that a contribution was made to the literature; unlike previous research that focuses on environmental leadership in business sectors, this study focuses on community environmental leadership in a Latin American context, where factors such as local participation, traditional knowledge and sociocultural resilience play a crucial role. Likewise, the effectiveness of participatory methodologies is demonstrated, in line with proposals for contextualized environmental education. The impact of training on community mobilization is also evident; 19 trained leaders mobilized 1,500 people for tangible environmental actions (clean-up campaign and reforestation planning).

However, for future studies it will be necessary to seek greater representation of population groups. The duration of the research should also be taken with due caution; we are documenting the design and implementation of the program, but longitudinal monitoring is required in the medium and long term.

This study lays the groundwork for future research on scalable leadership training models that can be applied to other environmentally vulnerable communities. Future studies should explore the long-term impact of community-based environmental leadership programs on local governance and conservation efforts, and the integration of digital tools and technology to enhance environmental education and activism.

This study demonstrates that community-driven environmental leadership can catalyze sustainable environmental management. The model presented here serves as a replicable framework for other regions facing similar socio-environmental challenges, emphasizing the importance of local knowledge as a driver of sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Aparicio López, J.L.; methodology: Rodríguez Alviso, C.; software and validation: Castro Bello, M.; formal analysis: Villerías Salinas, S.; investigation: Rojas Casarrubias, C..; writing—original draft preparation: Aparicio López, J.L..; writing—review and editing: Rodriguez Alviso, C.; funding acquisition: Rojas Casarrubias, C; Aparicio López, J.L.; Rodríguez Alviso, C.; Castro Bello, M. and Villerías Salinas, S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received external funding from the National Humanities Council of Science and Technology [CONAHCYT] by its acronym in Spanish through the national scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. As part of the ethical protocol, this research process complied with the guidelines issued by the Bioethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Guerrero (Reference: CB-003/2021). The theoretical, epistemic, and methodological foundations were evaluated, ensuring full respect for the characteristics of the study area, its cultural traditions, and the participants´ idiosyncrasies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank C. Ricardo Herrera, Rosa María Brito, Juan Camilo Cardona, Alejandra Moreno, and the Tlali association for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ONU |

Organización de las Naciones Unidas |

| GTL |

Green Transformational Leadership |

| SMEs |

Small – Medium Entrepreneurs |

| ESTL |

Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership |

| GSL |

Green Servant Leadership |

| ESG |

Environmental Social Governance |

| CSR |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

| INEGI |

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography |

| UNEP |

United Nations Environment Program |

| CONABIO |

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| TDN |

Training Needs Diagnosis |

| SL |

Servant Leader |

References

- Celis Campos, I. Liderazgo ambiental: una práctica imprescindible. Saving The Amazon. May 13th, 2021. Available online: https://savingtheamazon.org/blogs/news/liderazgo-ambiental-una-practica-imprescindible.

- Chávez, J.; Ibarra, M. Liderazgo y cambio cultural en la organización para la sustentabilidad. TELOS. Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinarios en Ciencias Sociales 2016, 18, 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, G.; Hernández, O.; González, F. Liderazgo comunitario y su influencia en la sociedad como mejora del entorno rural, Revista INNOVA ITFIP 2019, 15–27. https://www.revistainnovaitfip.com/index.php/innovajournal/article/view/52.

- Castro, M.; Da Silva, H.; Nunes, I.C.; Almeida, T. Anthropogenic Actions and Socioenvironmental Changes in Lake of Juá, Brazilian Amazonia. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Santos-Echeandia, J.; Rodríguez-Herrera, J.; Marmolejo-Rodríguez, A. Estudio integral de la calidad del agua en el litoral del puerto San Carlos, Baja California Sur, México. Revista Internacional de Contaminación Ambiental 2020, 36, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, L.; Rodríguez, C.; López, J. L.; Salinas, S.; Bello, M. Análisis socioambiental de la Laguna de Tres Palos, México: Un enfoque socioecosistémico. Regions & Cohesión 2023, 13, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente [PNUMA]. GEO 6 Perspectivas del medio ambiente mundial. Resumen para responsables de políticas 2019, 9-11. Available online: https://www.unep.org/es/resources/perspectivas-del-medio-ambiente-mundial-6.

- Sandoval, A. La problemática detrás del Lago de Chapala. Gaceta UNAM 2021, Available online: https://www.gaceta.unam.mx/?s=chapala+.

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales [SEMARNAT]. Informe de la Situación del Medio Ambiente en México, 1st. Ed; SEMARNAT, México 2018; pp. 22. Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgeia/informe18/index.html.

- Evaluación de la calidad ambiental del Humedal Refugio de Vida Silvestre Sistema Lagunar de Tisma, Masaya, Nicaragua. Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias en Manejo y Conservación de los Recursos Naturales Renovable, Facultad de Recursos Naturales y del Ambiente-Universidad Nacional Agraria, Managua, Nicaragua 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.una.edu.ni/3682/1/tnt01c352.

- Borden, D. R.; Gosling, J.; Hawkins, B. Exploring Leadership. Oxford University Press. United Kingdom. 2023; 83, 97.

- Northouse, P. G. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc. Thousand Oak, California 2013; 5.

- Cybellium. Exploring Leadership Styles: A Comprehensive Guide to Learn Leadership Styles. Cybellium Ltd. 2024; 3-18.

- Hernández-Carrera, R.; Bautista-Vallejo, J.M. El Liderazgo en la Educación: Conceptos, Modelos y Estilos en el Marco Actual. Investigación, Tecnología y Sociedad: investigación e innovación en educación. Ed. DYKINSON, S.L. Madrid, 2019; 2065-2068.

- Changar, M.; Atan, T. The Role of Transformational and Transactional Leadership Approaches on Environmental and Ethical Aspects of CSR. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefferink, D.; Wurzel, R. Environmental leaders and pioneers: agents of change? Journal of European Public Policy 2016, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. Sustainable leadership: A literature review and prospects for future research. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeske, J. Leadership towards Sustainability: A Review of Sustainable, Sustainability, and Environmental Leadership. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, A.; Walkowiak. K.; Bernaciak, A. Leadership Styles of Rural Leaders in the Context of Sustainable Development Requirements: A Case Study of Commune Mayors in the Greater Poland Province, Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. The greening of Chicago: environmental leaders and organisational learning in the transition toward a sustainable metropolitan region. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2010, 53, 1051–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo-Araujo, L.M; Tereso-Ramírez, L.; Carrillo-Montoya, T. La participación comunitaria como vía para el empoderamiento de encargadas del programa Comedores Comunitarios en Culiacán, México. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e intervención social 2019, 28, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuejiao Niu; Xiaohu Wang; Hanyu Xiao. What motivates environmental leadership behaviour – an empirical analysis in Taiwan. Journal of Asian Public Policy 2017, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe [CEPAL]. Acerca de desarrollo sostenible 2024. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/temas/desarrollo-sostenible/acerca-desarrollo-sostenible.

- Novo, M. La educación ambiental, una genuina educación para el desarrollo sostenible. Revista de Educación número extraordinario 2009, 195-217. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3019430.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas [ONU] . La Agenda para el Desarrollo Sostenible 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/development-agenda/.

- Rojas Casarrubias, C.; Rodríguez Alviso, C.; Aparicio López, J.L.; Castro Bello, M.; Villerías Salinas, S.; Bedolla Solano, R. Problemas socioambientales desde la percepción de la comunidad: Pico del Monte-laguna de Chautengo, Guerrero. Sociedad y Ambiente 2023, 26, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión. Ley General de Equilibrio Ecológico y la Protección al Ambiente. Última reforma publicada en el Diario Oficial de la Federación 01-04-2024; 6. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGEEPA.pdf.

- Ferragut, E.; Velázquez, Y. T.; Pérez, E. Programa de educación ambiental para la comunidad de la Conchita, Pinar del Río. CIGET. Holguín 2018, 20, 308-318. Instituto de Información Científica y Tecnológica. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/6378/637869149007/637869149007.

- Tovar-Gálvez, J. C. Hacia una educación ambiental ciudadana contextualizada: consideraciones teóricas y metodológicas. Desde el trabajo por proyectos. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 2012b, 58, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, L.; Buendía, M. Guía para la estructuración y programación de un proyecto de Educación Ambiental y para la Sustentabilidad. Documento interno de trabajo. Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Mexico 2008, 1-24. Available online: https://www.uv.mx/mie/files/2012/10/SESION10-14-ABRIL-GuiaparalaevaluacionNieto.pdf.

- Schunk, D. H. Teorías del aprendizaje, 6th. ed.; Pearson Educación, México, 2012; 238-246. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39617127/SEXTA_EDICIÓN_TEORÍAS_DEL_APRENDIZAJE_Una_perspectiva_educativa.

- Márquez Duarte, F. Modelo de Naciones Unidas: una herramienta constructivista. Alteridad 2019, 14, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorliza, K. Environmental leadership, practices and sustainability. Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 2020, 17, 4370-4378. ISSN 1567-214X. Available online: https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/2434/2385.

- Arnold, H.; Cohen, F.; Warner, A. Youth and Environmental Action: Perspectives of Young Environmental Leaders on Their Formative Influences. The Journal of Environmental Education 2009, 40, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Leon, I.; Olmedo-Cifuentes, I.; Martínez-Victoria, M.; Arcas-Lario, N. Leadership Style and Gender: A Study of Spanish Cooperatives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N. M.; Gould, R. K.; Kelsey, E.; Fielding-Singh, F. Collaborative and Transformational Leadership in the Environmental Realm. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2014, 17, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Barrera, D. M.; Rojas Caldelas, R. I. Estilo de liderazgo predominante en organizaciones sociales dedicadas a la educación ambiental. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia (RVG) 2017, 22, 657–671. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Gálvez, J. C. Fundamentos para la formación de líderes ambientales comunitarios: consideraciones sociológicas, deontológicas, epistemológicas, pedagógicas y didácticas. Revista Luna azul 2012a, 34, 214-239. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=321727348013.

- Monroe, M. C.; Ballard, H. L.; Oxarart, A., Sturtevant, V. E.; Jakes, P. J.; Evans, E. R. Agencies, educators, communities, and wildfire: partnerships to enhance environmental education for youth. Environmental Education Research 2015, 22, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Paz, R.; Chapalbay, R. Escuela de liderazgo ambiental de la Reserva Biosfera de Sumaco: RBS Estrategia multi-organizacional e innovación local de los recursos naturales (2009-2011) 2011. Número de informe: Serie Sistematizaciones, Fascículo 2. Afiliación: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/33909882/Escuela_de_Liderazgo_Ambiental_de_la_Reserva_de_Biosfera_Sumaco_RBS_Una_estrategia_multi_organizacional_e_innovadora_para_fomentar_la_gobernanza_local_de_los_recursos_naturales.

- Suliman, M.A.; Abdou, A.H.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Al-Khaldy, D.A.W.; Anas, A.M.; Alrefae,W.M.M.; Salama,W. Impact of Green Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Environmental Performance in the Hotel Industry Context: Does GreenWorkEngagement Matter? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgül, B.; Zehir, C. How Managers’ Green Transformational Leadership Affects a Firm’s Environmental Strategy, Green Innovation, and Performance: The Moderating Impact of Differentiation Strategy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.A.E.; Ejaz, F.; Ejaz, S. Green Transformational Leadership, GHRM, and Proenvironmental Behavior: An Effectual Drive to Environmental Performances of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Li, W.; Mavros, C. Transformational Leadership and Sustainable Practices: How Leadership Style Shapes Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Martín, R.; Duran-Heras, A.; Reina Sánchez, K. Influence of Leadership Styles on Sustainable Development for Social Reconstruction: Current Outcomes and Advisable Reorientation for Two Aerospace Multinationals—Airbus and TASL. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Fahlevi, M.; Rahman, E.Z.; Akram, M.; Jamshed, K.; Aljuaid, M.; Abbas, J. Impact of Green Servant Leadership in Pakistani Small and Medium Enterprises: Bridging Pro-Environmental Behaviour through Environmental Passion and Climate for Green Creativity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, F. Transformational Leadership, Organizational Innovation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from SMEs in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, E. Pensamiento Ambiental Latinoamericano: Patrimonio de un Saber para la Sustentabilidad*. ISEE Publicación Ocasional 2009, 6, 5-15. Available online: https://iseethics.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/saps-no-09-span.pdf.

- Vizina, Y. N. Decolonizing Sustainability through Indigenization in Canadian Post-Secondary Institutions. Societies 2022, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonchingong Che, C.; Bang, H.N. Towards a “Social Justice Ecosystem Framework” for Enhancing Livelihoods and Sustainability in Pastoralist Communities. Societies 2024, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiarti, T.; Purba, J.T.; Pramono, R. Enhancing Human Resource Quality in Lombok Model Schools: A Culture-Based Leadership Approach with Tioq, Tata, and Tunaq Principles. Societies 2024, 14, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales [SEMARNAT]. Estrategia nacional de educación ambiental para la sustentabilidad, en México. 1st. ed. México 2006; 27-47. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/educacionambiental/documentos/estrategia-de-educacion-ambiental-para-la-sustentabilidad-en-mexico-version-extensa.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI]. Rumbo al Censo 2020. Available in: https://iieg.gob.mx/ns/wpcontent/uploads/2019/04/CENSO-2020-Consulta.pdf.

- Plan Municipal de Desarrollo. Municipio de Florencio Villarreal, Guerrero. H. Ayuntamiento Municipal Constitucional de Copala, Gro. 2021-2024. Available in: https://congresogro.gob.mx/63/ayuntamientos/plan-municipal/plan-municipal-de-desarrollo-florencio-villarreal-rpg.pdf.

- Plan Municipal de Desarrollo . Municipio de Copala, Guerrero. H. Ayuntamiento Municipal Constitucional de Copala, Gro. 2021-2024. Available in: https://congresogro.gob.mx/63/ayuntamientos/plan-municipal/plan-municipal-copala.pdf.

- Plan Municipal de Desarrollo. Municipio de Cuautepec, Guerrero. H. Ayuntamiento Municipal Constitucional de Cuautepec, Gro. 2021-2024. Available in: https://congresogro.gob.mx/63/ayuntamientos/plan-municipal/plan-de-desarrollo-municipal-2021-municipio-de-cuautepec.pdf.

- Hintz, C.J.; Lackey, B.K. Assessing community needs for expanding environmental education programming, Applied Environmental Education & Communication 2017, 16, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Gálvez, J.C. Pedagogía ambiental y didáctica ambiental: tendencias en la educación superior. Revista Brasileira de Educação 2017, 22, 519–538. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad [CONABIO]. Distribución de los manglares en México en 1981. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/?vns=gis_root%2Fusv%2Fotras%2Fusva1mgw&fbclid=IwAR29f5tNbn5flOUCskrs-qeXHCHbvSotrSYfgwGfDUd3_qLsCAoGit8tDL4.

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad [CONABIO]. Distribución de los manglares en México en 2010. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/?vns=gis_root%2Fusv%2Fotras%2Fusva1mgw&fbclid=IwAR29f5tNbn5flOUCskrs-qeXHCHbvSotrSYfgwGfDUd3_qLsCAoGit8tDL4.

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad [CONABIO]. Distribución de los manglares en México en 2020. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/?vns=gis_root%2Fusv%2Fotras%2Fusva1mgw&fbclid=IwAR29f5tNbn5flOUCskrs-qeXHCHbvSotrSYfgwGfDUd3_qLsCAoGit8tDL4.

- Stokking, H.; Van Aert, L.; Meijberg, W.; Kaskens, A. Evaluating Environmental Education. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK in cooperation with the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries, United Kingdom ,2009; pp. 8-9. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/1999-069.pdf.

- Li, Z.; Xue, J.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, T. Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership and employee´s pro-environmental behavior: The mediating roles of environmental passion and autonomous motivation. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Chang, T.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Yen, S.J.; Ting, C.W. How does sustainable leadership affect environmental innovation strategy adoption? The mediating role of environmental identity. International Journal of Environmental Research and public health 2023, 20, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, C.; Bohórquez, H.A.; Piña, D.C. El empoderamiento de los líderes ambientales escolares: una estrategia para desarrollar la cultura ambiental en dos colegios públicos de Bogotá D.C. Revista Tecné, Episteme y Didaxis: TED al 2016, Número extraordinario. Bogotá, Colombia. https://revistas.upn.edu.co/index.php/TED/article/view/4620.

- Selby, S.T.; Cruz, A.R.; Ardoin, N.M.; Durham, W.H. Community-as-pedagogy: Environmental leadership for youth in rural Costa Rica, Environmental Education Research 2020, 26, 1594-1620. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1278772.

- Jones, R.; White, O.; Twigger-Ross, C. Our bright future evaluation. Environmental leadership: a research study. ERS Ltd and Collingwood Environmental Planning 2021. Available online: https://www.ourbrightfuture.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Our-Bright-Future-Environmental-Leadership-Study-FINAL.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).