Submitted:

02 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Apple by-products (AP) consist of whole defective fruits discarded from the market and pomace resulting from juice squeezing and puree production, which are currently underutilized or dis-posed of due to the lack of effective and scalable extraction methods. Bioactive compounds in AP, especially phlorizin, which is practically exclusive to the apple tree, are endowed with preventive and therapeutic potential concerning chronic diseases such as cardiovascular, metabolic and specific types of cancer. This study investigated the exploitation of AP using hydrodynamic cavitation (HC) for the extraction step and water as the only solvent. High-temperature extraction (>80°C) was needed to inactivate the polyphenol oxidase; a strict range of the cavitation number (around 0.07) was identified for extraction optimization; less than 20 minutes were sufficient for extraction of macro- and micro-nutrients up to nearly their potential level, irrespective of the concentration of fresh biomass up to 50% of the water mass. The energy required to produce 30 to 100 g of dry extract containing 100 mg of phlorizin was predicted around or less than 1 kWh, with HC contributing for less than 2.5% to the overall energy balance due to the efficient extraction process.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

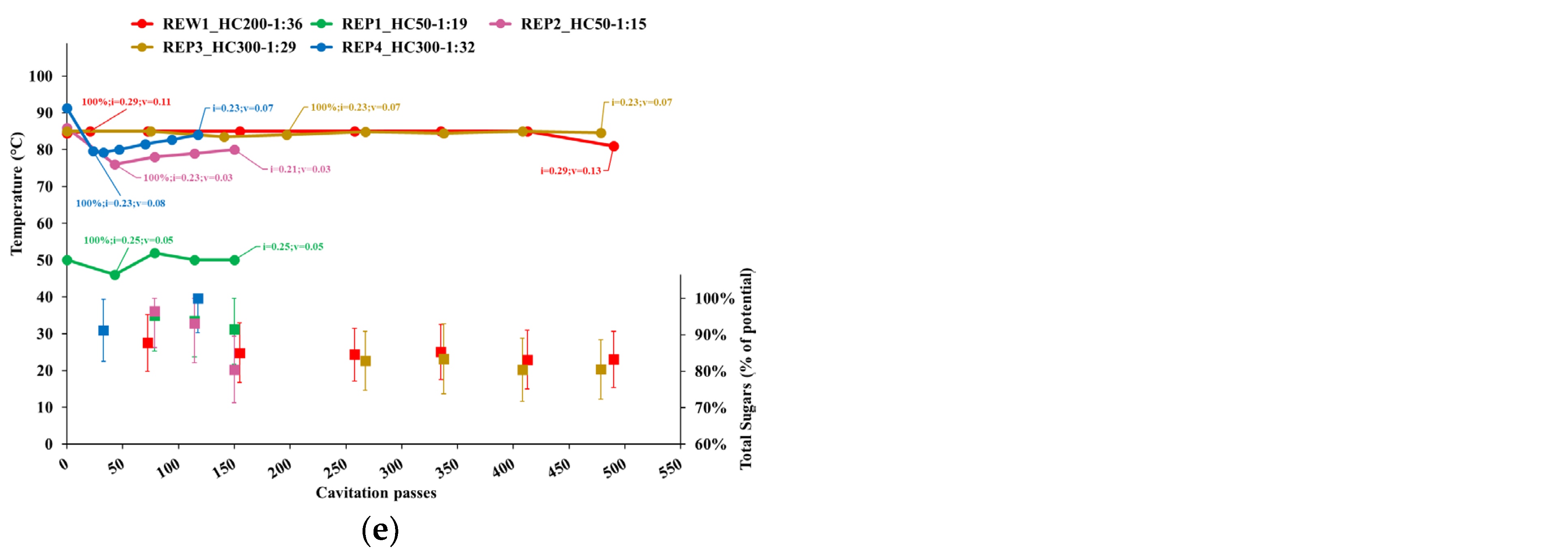

2.1. Hydrodynamic Cavitation

2.2. Raw Materials

2.3. Production of Apple Extracts

2.3.1. HC Device and Method

2.4. Analysis of Raw Material and Extracts

- Sugars: glucose, fructose, sucrose, xylose and sorbitol were quantified according to the method developed by Di Lella et al. [55]. 1 g of the raw apple material and 1 g of the extracted sample were dissolved in 40 mL of water, centrifuged, and the supernatant was subsequently diluted 25-fold for the raw material and 5-fold for the extracted samples. Quantification was performed using an ICS 5000 ion chromatograph (Dionex, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a pulsed amperometric detector (PAD) consisting of a gold working electrode and a palladium reference electrode. The sugar content was calculated by summing the individual sugars. Repeatability (calculated as RSD%) of 5% and uncertainty (σ/√2) of 4%.

- ORAC: Oxygen Radical Absorbance capacity was evaluated in according to Ou et al. [56], by dissolving 1 g of samples in 50 mL of an acetone:water mixture (50:50, v/v) for raw materials and 5 mL for extracted samples and appropriately diluting them with 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for analysis. Subsequently, 150 µL of fluorescein working solution (1.2 µM) was added to microplate wells along with 50 µL of diluted buffer, standard (Trolox, 100 µM), control, and samples. The kinetic reaction with AAPH solution (41 g/L) took place in a fluorescence microplate reader (Varioskan Lux, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and was measured every minute for 35 minutes (excitation at 485 nm and emission at 530 nm). Repeatability (calculated as RSD%) of 11% and uncertainty (σ/√2) of 7%.

- TPC: Total Polyphenol Content was quantified adapting the protocol elaborated by Ceci et al. [57]. 10 g of the raw material were extracted with 40 mL of a water:methanol mixture (80:20, v/v) acidified with 0.85% H₃PO₄. The mixture was shaken for 15 min and centrifuged at 4 °C and 4000 rpm for 5 min (Rotina 380, Hettich, Germany). The supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Extracts were diluted 25 times with the same solvent mixture. TPC was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method. 2 mL of the extract was added to 1 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min. Then, 5 mL of sodium carbonate solution (20% w/v) was added. After 90 min, the absorbance was recorded at 740 nm using a Cary 60 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and compared to a standard curve of catechin [58]. Repeatability (calculated as RSD%) of 16% and uncertainty (σ/√2) of 11%.

- Phenolic profile: individual phenolic compounds were quantified with a liquid chromatograph coupled to a heated electrospray ionization source (HESI-II) and a high-resolution Q-Exactive™ hybrid mass spectrometer (HPLC-HQOMS/Orbitrap; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed using an ACCLAIM Vanquish PA 2 column (150 × 3 mm, 2.7 µm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of H₂O/FA 100 mM/NH₄HCO₂ 20 mM, acetonitrile, and water in a gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min in 21.0 minutes. Mass spectrometric analysis was conducted with a Full MS scan - data dependent (MS/MS) experiment setting a resolution of 70,000 FWHM (m/z 200, 1.5 Hz) over a scan range of 200–2000 m/z. Repeatability (calculated as RSD%) of 10% and uncertainty (σ/√2) of 7%.

- TDS: thermobalance, model MA 110.R (Radwag, Radom, Poland).

3. Results

3.1. AP Biochemical Characterization

3.2. APE Biochemical Characterization and Extraction Yield

3.2.1. TPC and ORAC

- Temperature;

- Cavitation number in the impeller (i) and Venturi-shaped reactor (v) zones, depicted as tags to the temperature curve;

- Extraction yield, computed as the ratio of TPC content or ORAC level in APE to the corresponding levels in AP, normalized to the dry biomass;

- Peak process yield, depicted as tags to extraction yield data points and computed as the consumed energy (Wh) needed to obtain 1 mgCAT of TPC, or 1 mgTE of ORAC, from 1 g of dry AP. Hence, the process yield increases with the decrease of the computed quantity.

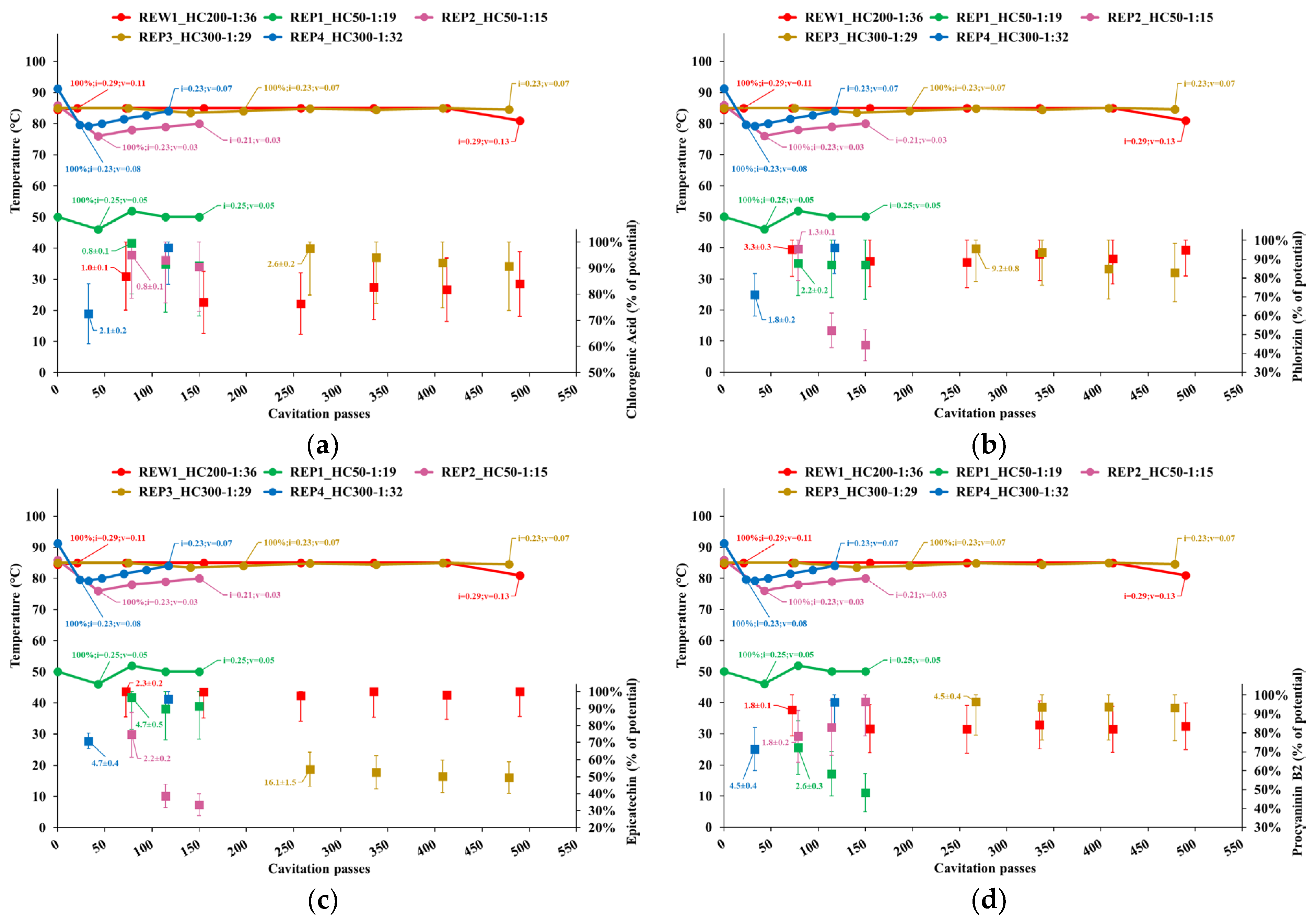

3.2.2. Individual Phenolics and Total Sugars

- Temperature;

- Cavitation number in the impeller (i) and Venturi-shaped reactor (v) zones, depicted as tags to the temperature curve;

- Extraction yield, computed as the ratio of the content of individual phenolic compounds or total sugars in APE to the corresponding levels in AP, normalized to the dry biomass;

- Peak process yield, depicted as tags to extraction yield data points and computed as the consumed energy (Wh) needed to obtain 1 mg of individual phenols from 1 kg of dry AP. Hence, the process yield increases with the decrease of the computed quantity.

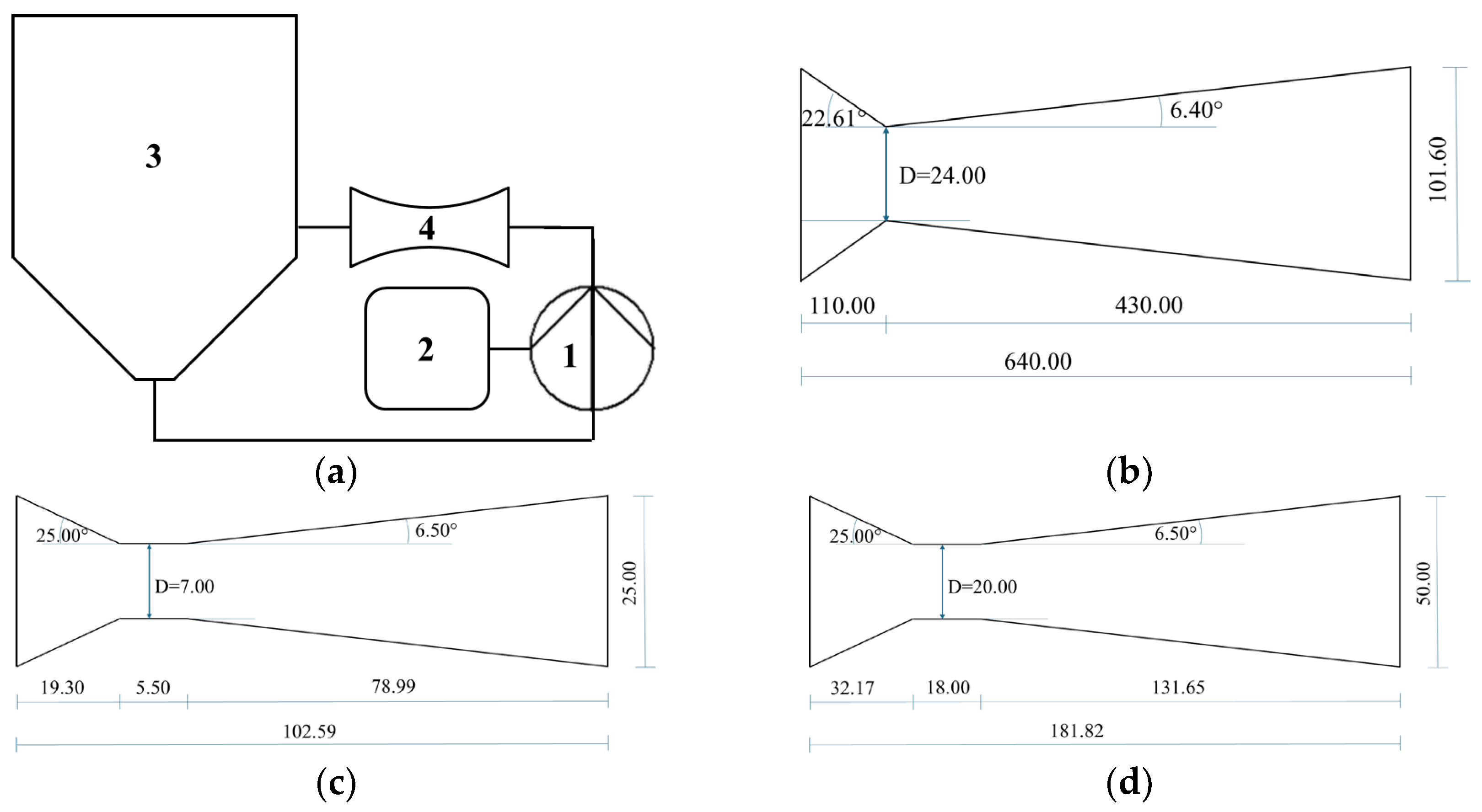

3.3. Mass Extraction Yield and Estimated Composition of Dry Extracts

4. Discussion

- The extraction tests, aimed to investigate the feasibility and efficiency of the HC technique, were carried out without a proper design of experiments and with different lots of apples, leading to a remarkable variability of AP composition, as shown in Table 2.

- In tests REP1, REP2, REP3 and REP4, AP was produced from the whole fruit using a pilot-scale hydropress. The use of industrial by-products could improve the standardization of AP, the reduction of the total sugars content and the reproducibility of the results, which will be the subject of further research.

- The structure of the extracted phytocomplexes was not investigated. For example, HC-based extracts of red orange by-products were found to consist of stable phytocomplexes with flavonoids adsorbed onto the surface of pectin [63]. The mechanisms underlying the generation of pectin-polyphenols conjugates, using both citrus and apple commercial pectin, were identified, for example in the case of hydroxytyrosol, as the adsorption onto the surface of pectin, resulting in relatively weak non-covalent bonds, and the free radical method that produces stronger covalent bonds [64]. It can be hypothesized that HC processes intensify both conjugation mechanisms: adsorption, due to the greatly enhanced mass transfer rate produced by the HC-induced turbulence; likely more important, the formation of strong covalent bonds, which can be boosted due to the HC-based effective generation of hydroxyl radicals (∙OH) [42,65]. However, the extracted red orange pectin showed a very low degree of esterification of 17.05% [63], while pectin extracted from Renetta variety apples showed a substantially higher degree of esterification of 74.2% [27], associated with a higher degree of hydrophobicity [66]. While a stable conjugation of apple polyphenols and pectin could improve metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes [28,29,30,67], whether our HC-based process could lead to such conjugation remains to be investigated and will be the subject of further research, including in vivo experiments.

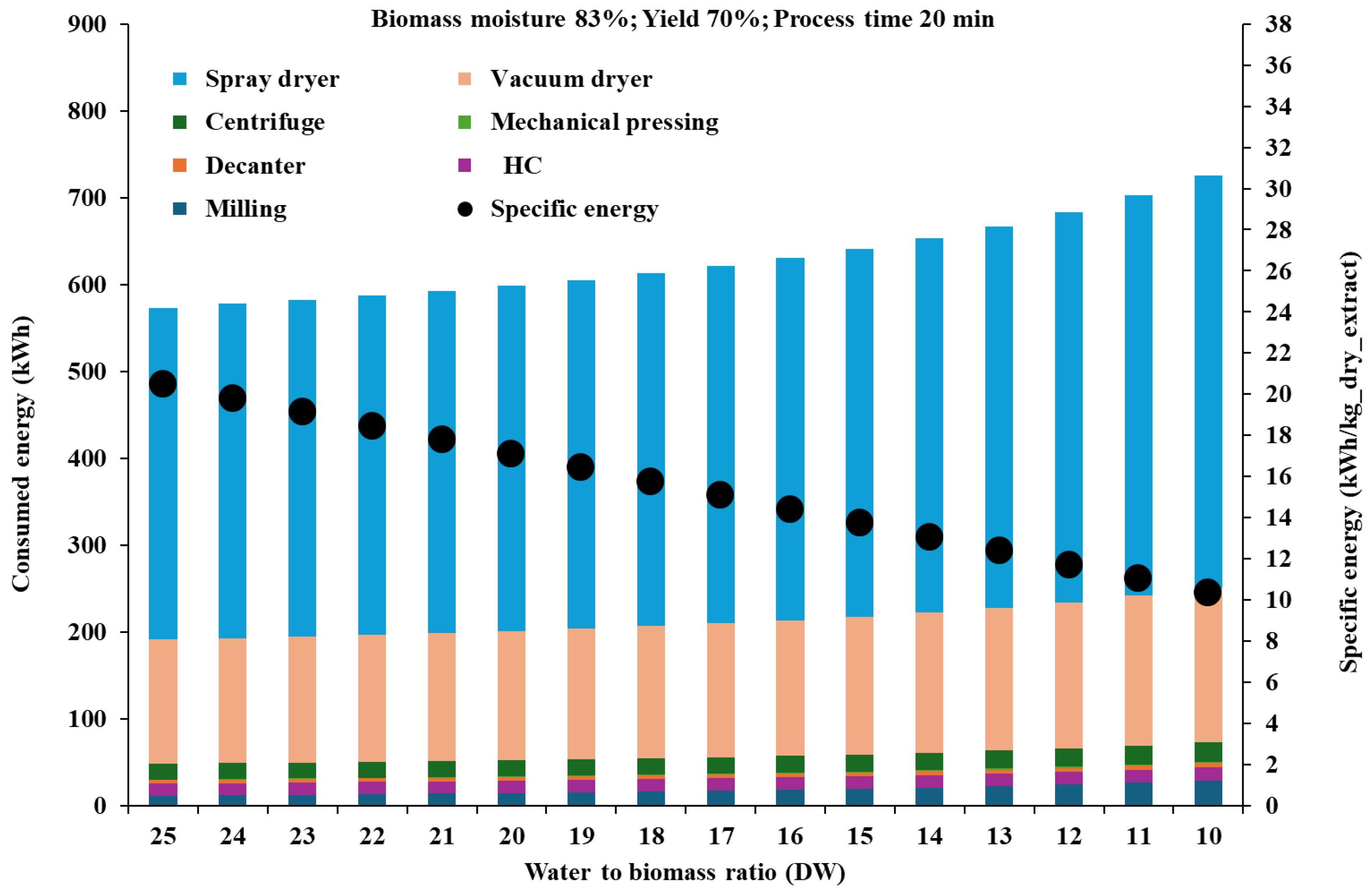

4.1. Scaled-Up Production of Dry Extracts

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, M.; Gramza-Michalowska, A. Recent Development on the Chemical Composition and Phenolic Extraction Methods of Apple (Malus Domestica)—A Review. Food Bioproc Tech 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, U.; Morozova, K.; Ferrentino, G.; Scampicchio, M. Apples and Apple By-Products: Antioxidant Properties and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Yi, J.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Bi, J. Systematic Review of Phenolic Compounds in Apple Fruits: Compositions, Distribution, Absorption, Metabolism, and Processing Stability. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyenihi, A.B.; Belay, Z.A.; Mditshwa, A.; Caleb, O.J. “An Apple a Day Keeps the Doctor Away”: The Potentials of Apple Bioactive Constituents for Chronic Disease Prevention. J Food Sci 2022, 87, 2291–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, J.; Liu, R.H. Apple Phytochemicals and Their Health Benefits. Nutr J 2004, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsos, A.; Tuohy, K.M.; Lovegrove, J.A. Apples and Cardiovascular Health—Is the Gut Microbiota a Core Consideration? Nutrients 2015, 7, 3959–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliceti, C.; Malaguti, M.; Marracino, L.; Barbalace, M.C.; Rizzo, P.; Hrelia, S. Agri-Food Waste from Apple, Pear, and Sugar Beet as a Source of Protective Bioactive Molecules for Endothelial Dysfunction and Its Major Complications. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, M.; Ghimire, S.; Karki, G.; Deokar, G.S.; Al-Asmari, F.; Nirmal, N.P. Fruit Waste: Potential Bio-Resource for Extraction of Nutraceuticals and Bioactive Compounds. In Bioactive Extraction and Application in Food and Nutraceutical Industries. Methods and Protocols in Food Science; Sarkar, T., Pati, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, USA, 2024; pp. 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetafika, H.N.; Bchir, B.; Blecker, C.; Richel, A. Fractionation of Apple By-Products as Source of New Ingredients: Current Situation and Perspectives. Trends Food Sci Technol 2014, 40, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, K.; Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Teleky, B.E.; Martău, G.A.; Plamada, D.; Pascuta, M.S.; Nemeş, S.A.; Varvara, R.A.; Vodnar, D.C. Natural Polyphenol Recovery from Apple-, Cereal-, and Tomato-Processing By-Products and Related Health-Promoting Properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollini, L.; Cossignani, L.; Juan, C.; Mañes, J. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Fresh Apple Pomace by Different Non-Conventional Techniques. Molecules 2021, 26, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, J.C.M.; Arraibi, A.A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Bioactive and Functional Compounds in Apple Pomace from Juice and Cider Manufacturing: Potential Use in Dermal Formulations. Trends Food Sci Technol 2019, 90, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyson, D.A. A Comprehensive Review of Apples and Apple Components and Their Relationship to Human Health. Advances in Nutrition 2011, 2, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Buttari, B.; Panieri, E.; Profumo, E.; Saso, L. An Overview of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, R.; Chen, M.; Huang, A.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammation Effects of Dietary Phytochemicals: The Nrf2/NF-ΚB Signalling Pathway and Upstream Factors of Nrf2. Phytochemistry 2022, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gado, F.; Ferrario, G.; Della Vedova, L.; Zoanni, B.; Altomare, A.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G.; D’Amato, A.; Baron, G. Targeting Nrf2 and NF-ΚB Signaling Pathways in Cancer Prevention: The Role of Apple Phytochemicals. Molecules 2023, 28, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn-Haren, G.; Dragsted, L.O.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Jensen, E.N.; Jensen, R.I.; Németh-Balogh, M.; Paulovicsová, B.; Bergström, A.; Wilcks, A.; Licht, T.R.; et al. Intake of Whole Apples or Clear Apple Juice Has Contrasting Effects on Plasma Lipids in Healthy Volunteers. Eur J Nutr 2013, 52, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Anh, N.H.; Jung, C.W.; Long, N.P.; Park, S.; Cho, Y.H.; Yoon, Y.C.; Lee, E.G.; Kim, M.; Son, E.Y.; et al. Metabolic and Cardiovascular Benefits of Apple and Apple-Derived Products: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobek, L.; Matić, P. Phenolic Compounds from Apples: From Natural Fruits to the Beneficial Effects in the Digestive System. Molecules 2024, 29, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobek, L.; Pöc, K.; Valenteković, M.; Matić, P. The Behavior of Phenolic Compounds from Apples during Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion with Focus on Chlorogenic Acid. Foods 2024, 13, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wei, X.; Miao, Z.; Hassan, H.; Song, Y.; Fan, M. Screening for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Phenolics from Golden Delicious Apple Pomace. Chem Cent J 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birru, R.L.; Bein, K.; Bondarchuk, N.; Wells, H.; Lin, Q.; Di, Y.P.; Leikauf, G.D. Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Apple Polyphenol Phloretin on Respiratory Pathogens Associated With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. The Molecular Pharmacology of Phloretin: Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Action. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.-K.; Cho, S.-J.; Jung, U.; Ryu, R.; Choi, M.-S. Phlorizin Supplementation Attenuates Obesity, Inflammation, and Hyperglycemia in Diet-Induced Obese Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2016, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, C.; Bangert, A.; Kottra, G.; Geillinger, K.E.; Schwanck, B.; Vollert, H.; Blaschek, W.; Daniel, H. Inhibition of the Intestinal Sodium-coupled Glucose Transporter 1 (SGLT1) by Extracts and Polyphenols from Apple Reduces Postprandial Blood Glucose Levels in Mice and Humans. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014, 58, 1795–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, N.; Kumar, M.; Radha; Rais, N.; Puri, S.; Sharma, K.; Natta, S.; Dhumal, S.; Damale, R.D.; Kumar, S.; et al. Exploring Apple Pectic Polysaccharides: Extraction, Characterization, and Biological Activities - A Comprehensive Review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, S.; Cecchi, L.; Khatib, M.; Domizio, P.; Zoccatelli, G.; Civa, V.; Mainente, F.; Breschi, C.; Ugolini, T.; Meneguzzo, F.; et al. 1H-NMR, HPSEC-RID, and HPAEC-PAD Characterization of Polysaccharides Extracted by Hydrodynamic Cavitation from Apple and Pomegranate By-Products for Their Valorization: A Focus on Pectin. Processes 2024, 12, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprikian, O.; Duclos, V.; Guyot, S.; Besson, C.; Manach, C.; Bernalier, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Demigné, C. Apple Pectin and a Polyphenol-Rich Apple Concentrate Are More Effective Together than Separately on Cecal Fermentations and Plasma Lipids in Rats. Journal of Nutrition 2003, 133, 1860–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn-Haren, G.; Dragsted, L.O.; Buch-Andersen, T.; Jensen, E.N.; Jensen, R.I.; Németh-Balogh, M.; Paulovicsová, B.; Bergström, A.; Wilcks, A.; Licht, T.R.; et al. Intake of Whole Apples or Clear Apple Juice Has Contrasting Effects on Plasma Lipids in Healthy Volunteers. Eur J Nutr 2013, 52, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Anh, N.H.; Jung, C.W.; Long, N.P.; Park, S.; Cho, Y.H.; Yoon, Y.C.; Lee, E.G.; Kim, M.; Son, E.Y.; et al. Metabolic and Cardiovascular Benefits of Apple and Apple-Derived Products: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrentino, G.; Morozova, K.; Mosibo, O.K.; Ramezani, M.; Scampicchio, M. Biorecovery of Antioxidants from Apple Pomace by Supercritical Fluid Extraction. J Clean Prod 2018, 186, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Nutrizio, M.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. A Review of Sustainable and Intensified Techniques for Extraction of Food and Natural Products. Green Chemistry 2020, 22, 2325–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, A.A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Turning Apple Pomace into Value: Sustainable Recycling in Food Production—A Narrative Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, U.C.; Muthukumarappan, K.; Meletharayil, G.H. Application of Hydrodynamic Cavitation to Improve Antioxidant Activity in Sorghum Flour and Apple Pomace. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2016, 100, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breschi, C.; D’Agostino, S.; Meneguzzo, F.; Zabini, F.; Chini, J.; Lovatti, L.; Tagliavento, L.; Guerrini, L.; Bellumori, M.; Cecchi, L.; et al. Can a Fraction of Flour and Sugar Be Replaced with Fruit By-Product Extracts in a Gluten-Free and Vegan Cookie Recipe? Molecules 2024, 29, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsos, A.; Riccadonna, S.; Ulaszewska, M.M.; Franceschi, P.; Trošt, K.; Galvin, A.; Braune, T.; Fava, F.; Perenzoni, D.; Mattivi, F.; et al. Two Apples a Day Lower Serum Cholesterol and Improve Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Adults: A Randomized, Controlled, Crossover Trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020, 111, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, M.; Zhang, G.; Petkovšek, M.; Long, K.; Coutier-Delgosha, O. Intensity and Regimes Changing of Hydrodynamic Cavitation Considering Temperature Effects. J Clean Prod 2022, 130470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciardo, E.; Tabasso, S.; Cravotto, G.; Bensaid, S. Process Intensification Strategies for Lignin Valorization. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 2022, 171, 108732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.S.; More, P.R.; Ladole, M.R.; Pegu, K.; Pandit, A.B. Non-Thermal, Energy Efficient Hydrodynamic Cavitation for Food Processing, Process Intensification and Extraction of Natural Bioactives: A Review. Ultrason Sonochem 2023, 98, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Scurria, A.; Pagliaro, M. Natural Product Extraction via Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Sustain Chem Pharm 2023, 33, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Tang, J.; Rahimi, M.; Halim, R.; Shen, H.; Tiwari, B.K.; Zhao, L. Chemistry of Hydrodynamic Cavitation Technology. In Chemistry of Thermal and Non-Thermal Food Processing Technologies; Brijesh, K.T., Mysore, B.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 259–287. ISBN 9780443221828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocelli, M.; Musmarra, D.; Prisciandaro, M.; Lancia, A. Chemical Effect of Hydrodynamic Cavitation: Simulation and Experimental Comparison. AIChE Journal 2014, 60, 2566–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal, M. V; Gogate, P.R. Wastewater Treatment Using Hybrid Treatment Schemes Based on Cavitation and Fenton Chemistry: A Review. Ultrason Sonochem 2014, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiang, C.; Mou, J.; Qian, H.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, P. Numerical Study of Rotating Cavitation and Pressure Pulsations in a Centrifugal Pump Impeller. AIP Adv 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wu, H.; Yang, G.; Tang, R.; Chang, C.; Xu, B.; Lin, S.; Zhang, D. Experimental Study on the Classification and Evolution of the Tip Cavitation Morphology in Axial Waterjet Pumps with Two Different Blade Numbers. J Mar Sci Eng 2024, 12, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xu, H.; Xuan, X.; Manickam, S.; Boczkaj, G.; Wang, B. Assessing the Industrialization Progress of Hydrodynamic Cavitation Process Intensification Technology: A Review. Curr Opin Chem Eng 2024, 45, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, D.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Tiwari, B.K. Cavitation Technologies for Extraction of High Value Ingredients from Renewable Biomass. TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 174, 117682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathijssen, A.J.T.M.; Lisicki, M.; Prakash, V.N.; Mossige, E.J.L. Culinary Fluid Mechanics and Other Currents in Food Science. Rev Mod Phys 2023, 95, 25004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Brunetti, C.; Fidalgo, A.; Ciriminna, R.; Delisi, R.; Albanese, L.; Zabini, F.; Gori, A.; dos Santos Nascimento, L.B.; De Carlo, A.; Ferrini, F. Real-Scale Integral Valorization of Waste Orange Peel via Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Processes 2019, 7, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flori, L.; Albanese, L.; Calderone, V.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M.; Ciriminna, R.; Zabini, F.; Testai, L. Cardioprotective Effects of Grapefruit IntegroPectin Extracted via Hydrodynamic Cavitation from By-Products of Citrus Fruits Industry: Role of Mitochondrial Potassium Channels. Foods 2022, 11, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, G.; Flori, L.; Spezzini, J.; Miragliotta, V.; Lazzarini, G.; Pirone, A.; Meneguzzo, C.; Tagliavento, L.; Martelli, A.; Antonelli, M.; et al. Improved Cardiovascular Effects of a Novel Pomegranate Byproduct Extract Obtained through Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, L.; Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Pagliaro, M. Beer-Brewing Powered by Controlled Hydrodynamic Cavitation: Theory and Real-Scale Experiments. J Clean Prod 2017, 142, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L.; Faraloni, C.; Meneguzzo, C.; Tagliavento, L.; Zabini, F. Pilot Scale Tannin Extraction from Chestnut Wood Waste Using Hydrodynamic Cavitation. In Proceedings of the Towards a Smart, Resilient and Sustainable Industry, ISIEA 2023; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Borgianni, Y., Matt, D.T., Molinaro, M., Orzes, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2023; Volume 745, pp. 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienaho, J.; Liimatainen, J.; Myllymäki, L.; Kaipanen, K.; Tagliavento, L.; Ruuttunen, K.; Rudolfsson, M.; Karonen, M.; Marjomäki, V.; Hagerman, A.E.; et al. Pilot Scale Hydrodynamic Cavitation and Hot-Water Extraction of Norway Spruce Bark Yield Antimicrobial and Polyphenol-Rich Fractions. Sep Purif Technol 2025, 360, 130925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lella, S.; Tognetti, R.; La Porta, N.; Lombardi, F.; Nardin, T.; Larcher, R. Characterization of Silver Fir Wood Decay Classes Using Sugar Metabolites Detected with Ion Chromatography. Journal of Wood Chemistry and Technology 2019, 39, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Chang, T.; Huang, D.; Prior, R.L. Determination of Total Antioxidant Capacity by Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Using Fluorescein as the Fluorescence Probe: First Action 2012.23. J AOAC Int 2013, 96, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceci, A.T.; Bassi, M.; Guerra, W.; Oberhuber, M.; Robatscher, P.; Mattivi, F.; Franceschi, P. Metabolomic Characterization of Commercial, Old, and Red-Fleshed Apple Varieties. Metabolites 2021, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, R.; Cravero, M.C. Metodi per Lo Studio Dei Polifenoli Dell’ Uva. Rivista di Viticoltura e di Enologia 1991, 44, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, J.J.; Richard-Forget, F.C.; Goupy, P.M.; Amiot, M.; Aubert, S.Y. Enzymatic Browning Reactions in Apple and Apple Products. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 1994, 34, 109–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Fu, G.; Xu, W.; Zhai, Y.; Bai, L.; Li, J.; Qu, T. Experimental Study on Attenuation Effect of Liquid Viscosity on Shockwaves of Cavitation Bubbles Collapse. Ultrason Sonochem 2024, 111, 107063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, W.G.; Han, X.D. Effects of Solid Particles at Varying Concentrations on Hydrodynamic Cavitation Evolution in a Nozzle. Journal of Applied Fluid Mechanics 2025, 18, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Hong, F.; Ying, D.; Huang, Y.; Nawaz Khan, S.; Jia, J. A Comprehensive Study on the Effects of Annular Protrusion for Cavitation Intensification in Venturi Tubes. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 498, 155306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurria, A.; Sciortino, M.; Garcia, A.R.; Pagliaro, M.; Avellone, G.; Fidalgo, A.; Albanese, L.; Meneguzzo, F.; Ciriminna, R.; Ilharco, L.M. Red Orange and Bitter Orange IntegroPectin: Structure and Main Functional Compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Senent, F.; Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Lama-Muñoz, A.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. Structural and Antioxidant Properties of Hydroxytyrosol-Pectin Conjugates: Comparative Analysis of Adsorption and Free Radical Methods and Their Impact on in Vitro Gastrointestinal Process. Food Hydrocoll 2025, 162, 110954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Hong, F.; Ying, D.; Huang, Y.; Nawaz Khan, S.; Jia, J. A Comprehensive Study on the Effects of Annular Protrusion for Cavitation Intensification in Venturi Tubes. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 498, 155306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqash, F.; Masoodi, F.A.; Dar, B.N.; Manzoor, N. Effect of Degree of Esterification on the Encapsulation Properties and Gut Health Potential of Apple Pectin. J Polym Environ 2023, 31, 2424–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, O.; Khudyakov, A.; Sergushkina, M.; Solomina, O.; Polezhaeva, T. Pectins as a Universal Medicine. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, O.; Albanese, L.; Guerrini, L.; Zanoni, B.; Zabini, F.; Meneguzzo, F. Whole Wheat Bread Enriched with Silver Fir (Abies Alba Mill.) Needles Extract: Technological and Antioxidant Properties. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102, 3581–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psakis, G.; Lia, F.; Valdramidis, V.P.; Gatt, R. Exploring Hydrodynamic Cavitation for Citrus Waste Valorisation in Malta: From Beverage Enhancement to Potato Sprouting Suppression and Water Remediation. Front Chem 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian Raj, A. Advancing Phytonutrient Extraction via Cavitation-Based Methodology: Exploring Catechin Recovery from Camellia Sinensis Leaves. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2023, 54, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nopens, M.; Sazama, U.; Krause, A.; Fröba, M. Specific Heat Capacity of Wood between −140 and 50 °C in Dry and Wet State. Holzforschung 2021, 75, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Perone, C.; Berardi, A.; Tamborrino, A. Energy Analysis and Numerical Evaluation of the Decanter Centrifuge for Wastewater Management to Allow a Sustainable Energy Planning of the Process. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2024, 22, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szepessy, S.; Thorwid, P. Low Energy Consumption of High-Speed Centrifuges. Chem Eng Technol 2018, 41, 2375–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrosta, V.; Santoso, B.; Siswantoro, D.H. Power Modeling in Rotary Vacuum Evaporator for Meniran Extraction Process. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, 30 September 2024; Volume 3124, p. 070018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.G.J.; McKenzie, K.A. Energy Consumption of Industrial Spray Dryers. Drying Technology 2005, 23, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ji, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Dietary Supplementation of Apple Phlorizin Attenuates the Redox State Related to Gut Microbiota Homeostasis in C57BL/6J Mice Fed with a High-Fat Diet. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Test ID | Date | Biomass a | Device | Fresh biomass (kg) | Dry biomass (kg) | Concentration (dry biomass towater) b | Time (min) | Temp. (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REW1 | Oct-2023 | Whole | HC200 | 28.7 | 4.8 | 1:36 | 95 | 84.4 ± 1.4 |

| REP1 | Dec-2023 | Pomace | HC50 | 11.4 | 2.1 | 1:19 | 42 | 49.6 ± 1.2 |

| REP2 | Dec-2023 | Pomace | HC50 | 17.4 | 2.9 | 1:15 | 42 | 79.8 ± 3.8 |

| REP3 | Jan-2024 | Pomace | HC300 | 48.9 | 8.4 | 1:29 | 102 | 84.5 ± 0.6 |

| REP4 | May-2024 | Pomace | HC300 | 37.3 | 6.0 | 1:32 | 25 | 82.6 ± 4.2 |

| Test ID | TPC (mgCAT/g_DW) a | ORAC (mgTE/g_DW) b | Phlorizin | Chlorogenic Acid | Epicatechin | Procyanidin B2 | Total sugars (mg/g_DW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/kg_DW) | |||||||

| REW1 | 9.8 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 0.8 | 492 ± 34 | 1712 ± 119 | 672 ± 47 | 918 ± 64 | 695 ± 31 |

| REP1 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 13.7 ± 1.2 | 628 ± 61 | 1628 ± 158 | 269 ± 26 | 650 ± 63 | 697 ± 32 |

| REP2 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 0.9 | 959 ± 82 | 1627 ± 140 | 728 ± 43 | 858 ± 74 | 738 ± 32 |

| REP3 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 13.1 ± 1.2 | 640 ± 58 | 2209 ± 201 | 640 ± 58 | 1298 ± 118 | 646 ± 34 |

| REP4 | 12.4 ± 0.8 | 12.2 ± 1.1 | 798 ± 51 | 658 ± 42 | 325 ± 21 | 314 ± 20 | 466 ± 25 |

| Test ID | TPC (mgCAT/g_DW) a | ORAC (mgTE/g_DW) b | Phlorizin | Chlorogenic Acid | Epicatechin | Procyanidin B2 | Total sugars (mg/g_DW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/kg_DW) | |||||||

| REW1 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 468 ± 38 | 1488 ± 119 | 677 ± 54 | 846 ± 68 | 611 ± 35 |

| REP1 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 552 ± 54 | 1622 ± 159 | 260 ± 25 | 470 ± 46 | 665 ± 27 |

| REP2 | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.8 | 914 ± 82 | 1547 ± 138 | 543 ± 49 | 829 ± 85 | 712 ± 36 |

| REP3 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 10.9 ± 1.0 | 612 ± 57 | 1474 ± 151 | 348 ± 32 | 1254 ± 116 | 535 ± 24 |

| REP4 | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 767 ± 52 | 644 ± 51 | 289 ± 23 | 303 ± 24 | 395 ± 22 |

| Test ID | Passes a | TDS (mg/g_DW) | Phlorizin | Chlorogenic Acid | Epicatechin | Procyanidin B2 | Total sugars (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/kg) | |||||||

| REP2 | 107 | 685 | 620 ± 64 | 2153 ± 221 | 356 ± 37 | 1211 ± 124 | 867 ± 45 |

| REP3 | 281 | 692 | 766 ± 74 | 2896 ± 281 | 456 ± 44 | 1740 ± 170 | 751 ± 33 |

| REP4 | 84 | 720 | 1068 ± 85 | 897 ± 71 | 403 ± 32 | 422 ± 33 | 656 ± 30 |

| Step | Quantity | Level | Unit | Source / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass | Specific heat of the dry biomass | 1370 | J/kgK | [71] |

| Milling | Material loss | 0 | % | data |

| Specific energy consumption a | 50 | kWh/ton | Personal experience with commercial bio-shredder | |

| HC | Process time | 20 | minutes | Evidence from this study |

| Temperature ramp | Constant at 80 °C | Evidence from this study | ||

| Energy consumption per unit time | 0.8 | kWh/min | Based on test REP4 b | |

| Yield of dry extract relative to dry biomass | 500 | g/kg_DW | Based on test REP4 (Table 4) | |

| Decanter centrifuging | Separation efficiency | 95% | [72] | |

| Moisture in separated material | 75% | |||

| Specific energy consumption c | 3.38 | kWh/ton | ||

| Mechanical pressing | Specific energy consumption d | 30 | kWh/ton | Personal experience |

| Moisture in separated material | 40% | |||

| Centrifuge | Energy consumption per unit mass of water | 15 | kWh/ton | [73] |

| Separation rate | 100 | % | Negligible errors due to 95% separation by the decanter | |

| Vacuum dryer | Water evaporation rate | 80% | [74] | |

| Energy consumption per unit mass of extract | 150 | kWh/ton | ||

| Spray dryer | Energy consumption per unit mass of extract | 1600 | kWh/ton | [75] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).