1. Introduction

The continuous growing trend of plastic production generates concerns for the disposal and management of post consume plastic, particularly those intended for single-use, hard to collect and hard to recycle applications. The global primary plastic production is estimated to reach 1,100 million tons by 2050. Around 36% of all plastics produced are used in packaging, including single-use items for food and beverage containers and agriculture use. Unfortunately, approximately 85% of these ends up as waste in landfills or unregulated areas. Moreover, almost 98% of single-use plastic products are derived from fossil fuels or "virgin" feedstock. The associated greenhouse gas emissions from the production, usage, and disposal of traditional fossil fuel-based plastics are anticipated to contribute to 19% of the global carbon budget by 2040 [

1].

The renewed focus on developing sustainable materials has prompted studies into biodegradable polymers that can replace conventional plastics derived from petroleum. Adipic and succinic acids are directly esterified with 1,4-butanediol to produce Poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) (PBSA), a thermoplastic aliphatic random co-polyester [

2]. Bio-based succinic acid is the source of some manufacturers to market partially bio-based poly(butylenee succinate) (PBS) and PBSA, which achieve a high bio-based content, up to 54 weight percent, this is envisaged to increase shortly due to the availability of even biobased [

2]. PBSA is noted for its excellent mechanical properties and processability like extrusion, film blowing, thermoforming, and injection moulding, mirroring those of polyolefins [

1,

3,

4].

PBSA differs from PBS having higher values for impact strength, elongation at break, and flexibility, while having lower crystallinity, tensile strength, and melting temperature [

5,

6]. Due to its mainly amorphous structure PBSA has a pretty fast rate of degradation in soil, ocean, industrial composting, and activated sludges [

2,

4] which makes it especially desirable for different applications, where biodegradability is a relevant property such as most agriculture applications including plant pots, bag liners, and agricultural mulching films [

6]. Another highly biodegradable family of polymers is that of the polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), synthesized by various bacteria strains under stress conditions with qualities comparable with those of several commodities plastics [

7,

8,

9]. Because of easier process ability and versatility in use, copolymers such as poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-valerate) (PHBV), have garnered a great deal of attention in both academic and industrial domains [

10] making them suitable for production of items by injection moulding [

11], with the advantage of being biodegradable in several environments [

12,

13,

14]. PHAs and PBSA have a relevant price (5-8 euros/kg) and (7-12 euros/kg) [

15] respectively, compared to other biodegradable polymers such as Polylactic acid (PLA) limiting their use in common low-cost applications such as packaging and agriculture devoted items.

The production of biocomposites where the polymeric matrix is highly biodegradable and the filler is a by-product of low value, represents an economical and environmentally sustainable substitute for conventional petroleum-derived materials that can be used to customize products for uses. Biocomposites characteristics have been covered in-depth in several books and papers [

16,

17]. The addition of natural or biobased fibres, which have lower density and biodegradability, makes biocomposites more affordable, lightweight and promotes biodegradability in particular disintegration [

13,

18]. Thus, biocomposite, possibly soil biodegradable, are raising interest in agriculture applications, allowing for disposal of the post consume plastic together with crops cuts in composting, while possible lost plastic debris in soil would be able to biodegrade and get converted in valuable biomass. Biomass, sourced from organic by-products like plant residues, agricultural waste, and forest by-products, stands as a renewable resource with vast potential to meet the growing demand for sustainable materials [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Among biomass available by-products insect’s exoskeleton is an innovative emerging resource. Indeed, insect proteins have emerged as a sustainable and versatile protein source, with applications mainly in animal feed. Specifically, insects, such as crickets, emerge as noteworthy valuable alternatives protein sources due to fast and relatively low cost raising. The insect exoskeletons remain after protein extraction procedure with alkaline as a no value biomass. In present study those exoskeletons were dried, milled and used as filler for bio-composites to be devoted to injection moulding items production. Representative prototypes of bio-composites have been produced in industrial scale as plant pots, confirming suitability of insect powder to be used as filler in biodegradable polymeric matrices, and were positively validated for plant growing and for compost ability and soil biodegradability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composite Materials

Polyhydroxyalkanoate-co-valerate (PHBV) is characterized by a density of 1.25 g/cm

3 and melt flow index (190 °C, 2.16 kg) of 15–20 g/10 min. PBSA was FD92PM from Mitsubishi with density 1.24 g/cm

3 (23 ± 0.5°C) [

24] melting temperature 84 °C; melt flow rate (MFR) 4 g/10 min (ISO 1133 190 ◦C/2.16 kg) [

25] with a butylene adipate content of about 20 wt.% [

26]. PBSA FD92PM is certified industrial/home compostable and biodegradable in soil by TÜV Austria and of food contact grade by EU10/2011 [

26]. Cricket insects were provided by the company Nutrinsect (MC, Italy), finely ground, and subsequently sifted using a 500-micron sieve. The finely ground and sifted powder was then placed in an oven at 60 degrees Celsius for 24 hours to eliminate any potential moisture before usage.

2.2. Composite Preparation on Laboratory Scale

Formulations were prepared with varying insect filler (I) content, including 0%, 5%, 10%, and 15% by weight relative to the total weight of the composite as reported in

Table 1. These formulations were based on a polymeric matrix with a 70/30 weight ratio PBSA/PHBV (M). This diverse set of formulations allowed for a comprehensive analysis of the impact of insect filler content on the properties of the composites.

Polymeric blends and composites were prepared by using a laboratory-grade single-screw extruder to produce monofilaments. This specialized extruder, manufactured by Brabender in Duisburg, boasts a screw with a diameter of 19 mm and a nominal length equivalent to 25 screw diameters. It is seamlessly interfaced with a computer and has four independently adjustable heating zones. This allows precise control and regulation of the temperature within different segments of the extruder, ensuring optimal processing conditions for monofilament production. The extruder operating conditions adopted for all the formulations were 175/180/175/160 °C with the die zone at 150 °C, and the total mass flow rate was 2 kg/h with a screw rate of 100 rpm. The extruded strands underwent cooling in a water bath at ambient temperature and were transformed into pellets using an automated knife cutter (PROCUT 3D, Chinchio Sergio Srl). The pellets were used to produce a dog-bone specimen for a tensile test. Tensile samples were manufactured using a mini-injection press (ZWP Proma, Poland). In the production of the dog-bone specimens, the pellets were introduced into the temperature-controlled barrel of the injection press set at 140°C. After approximately 1 minute, the molten material was mechanically injected into the stainless-steel dog-bone mould and held at 60°C for an additional minute before extracting the sample. All the materials utilized in the process were dried at 60 °C for 48 h before processing to minimize possible degradation for hydrolysis of the biopolyesters during processing in the extruder.

2.3. Composite Characterizations

The thermal stability of the composites obtained was investigated by thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA). These measurements were carried out, in duplicate, on about 10 mg of the sample by using a Netzsch STA 200 Regulus (Selb, Germany) under nitrogen flow (20 mL/min) at a heating speed of 10 K/min from 30°C to 700°C. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed by a Perkin Elmer DSC 6000 (Perkin Elmer Instrument, Waltham, MA, USA). About 15 mg of pellets were placed in an aluminium pan and subjected to a first heating from −60 ◦C to 185 ◦C (to remove any thermal history from processing), followed by cooling from 185°C to −60°C and a second heating to 185°C under a nitrogen flow (20 mL/min at 10 ◦C/min). The melting temperature (Tm) and the melting enthalpy (∆Hm) were determined by the second heating DSC curves. The crystallinity of each polymer was determined from the melting endotherm (∆Hm) as:

Where

i is the weight content of the corresponding polymer, ΔH0m, the melting enthalpy of a 100% crystalline polymer with pure PHBV (146 J/g) [

27] and PBSA (113.4 J/g) [

28].Tensile tests were conducted on dog-bone specimens (Type V) adhering to ASTM D638 standards, with dimensions verified to meet tolerance requirements: a length of 80 mm, a larger section width of 12 mm, a narrower section width of 4 mm, and a thickness of 2 mm. Tensile tests on the samples prepared with the injection moulder were performed at room temperature, at a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min, using an INSTRON 5500 R universal testing machine (Canton, MA, USA), equipped with a 10kN load cell and interfaced with a computer running the Merlin software (Canton, MA, USA).

The morphology of the insects’ powder and the bio-composites was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a COXEM Co. Ltd. Model EM-30 N (Daejo, Republic of Korea). The samples were frozen under liquid nitrogen and then fractured along the cross-section to cause a fragile fracture, providing a smoother surface for the SEM analyses. The sample fractured surface was metalized with a thin gold layer before microscopy to avoid charge buildup using a sputter coater, Edward S150B.

An MCR 92 rheometer from Anton Paar, equipped with a 25 mm diameter plate-plate configuration, was used to examine the effect of insect filler content on the viscosity of PBSA/PHBV composites. Before testing, each sample underwent a drying process and was then melted on the rheometer plate for 3 minutes at constant temperatures to eliminate any thermal history associated with processing. The measurements were carried out at four different temperatures (150, 160, 170, and 180 °C) using a 1 mm plate-plate configuration. To establish suitable operational parameters within the linear viscoelastic range, an amplitude strain sweep was conducted. Oscillatory angular frequency sweeps (ω) were performed ranging from 0.314 rad/s to 628 rad/s (0.05 to 100 Hz), using a strain amplitude (γ) of 0.2%. Complex viscosity (η*), loss modulus (G”), and storage modulus (G’) were measured about angular frequency (ω).

2.4. Scale-Up Production of Prototypes

The most effective formulations for plant pots have been prepared and fine-tuned, yielding the following conclusive compositions:

The plant pots were produced by injection moulding at an industrial scale by LCI/FEMTO Engineering, San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Italy. The demonstrators were moulded with a Negri Bossi P75 Injection moulding machine. The injection machine presents 4 extruder zones, with control of the temperature profile. The extruder operating conditions adopted for all the formulations were 160/170/170/170 °C.

2.5. Compost Degradation Tests

The developed bio-composite pots based on PBSA/PHBV and PBSA/PHBV/15%insect powder pot, were produced from polymers that were already certified according to EN 13432, with the optional addition of insect material. Insect filler was not chemically modified, doesn’t contain any additional organic additive in a concentration above 1% (dry weight) and the total sum of these organic constituents without determined biodegradability does not exceed 5%. In this case disintegration is requested to attest compost ability according to EN13432. The disintegration of demonstrators PBSA/PHBV pot (1.55 mm bottom, 1.56 mm sidewall), PBSA/PHBV/15%insect powder pot (1.52 mm bottom, 1.60 mm sidewall), was qualitatively tested according to ISO 16929. The thickness is an important characteristic, as a high thickness will impact the disintegration rate negatively. The pilot-scale aerobic composting test simulates as closely as possible a real and complete composting process in composting bins of 200 l. The pots both have a height of 15 cm and bottom diameter of 14 cm and were cut in pieces of 5 cm × 5 cm. They were added to a mixture of fresh Vegetable, Garden and Fruit waste (VGF) and structural material and introduced in an insulated composting bin after which composting spontaneously starts. Like in full-scale composting, inoculation and temperature increase happen spontaneously. During composting, the contents of the vessels are turned manually, at which time test item was retrieved and visually evaluated. The fresh biowaste was derived from the separately collected organic fraction of municipal solid waste, which was obtained from the waste treatment plant of Erembodegem, Belgium. The biowaste at start should have a moisture content and a volatile solids content on total solids (TS) of more than 50% and a pH above 5. From

Table 2 can be observed that these requirements were fulfilled. The biowaste contained a moisture content of 73.1% and a volatile solids content of 85.3% on TS. At start-up a pH of 5.6 was measured and after 1.7 weeks of composting the pH was increased till above 8.5. Furthermore, the C/N ratio of the biowaste at start should preferably be between 20 and 30. An optimal C/N ratio of 28 was found for the biowaste.

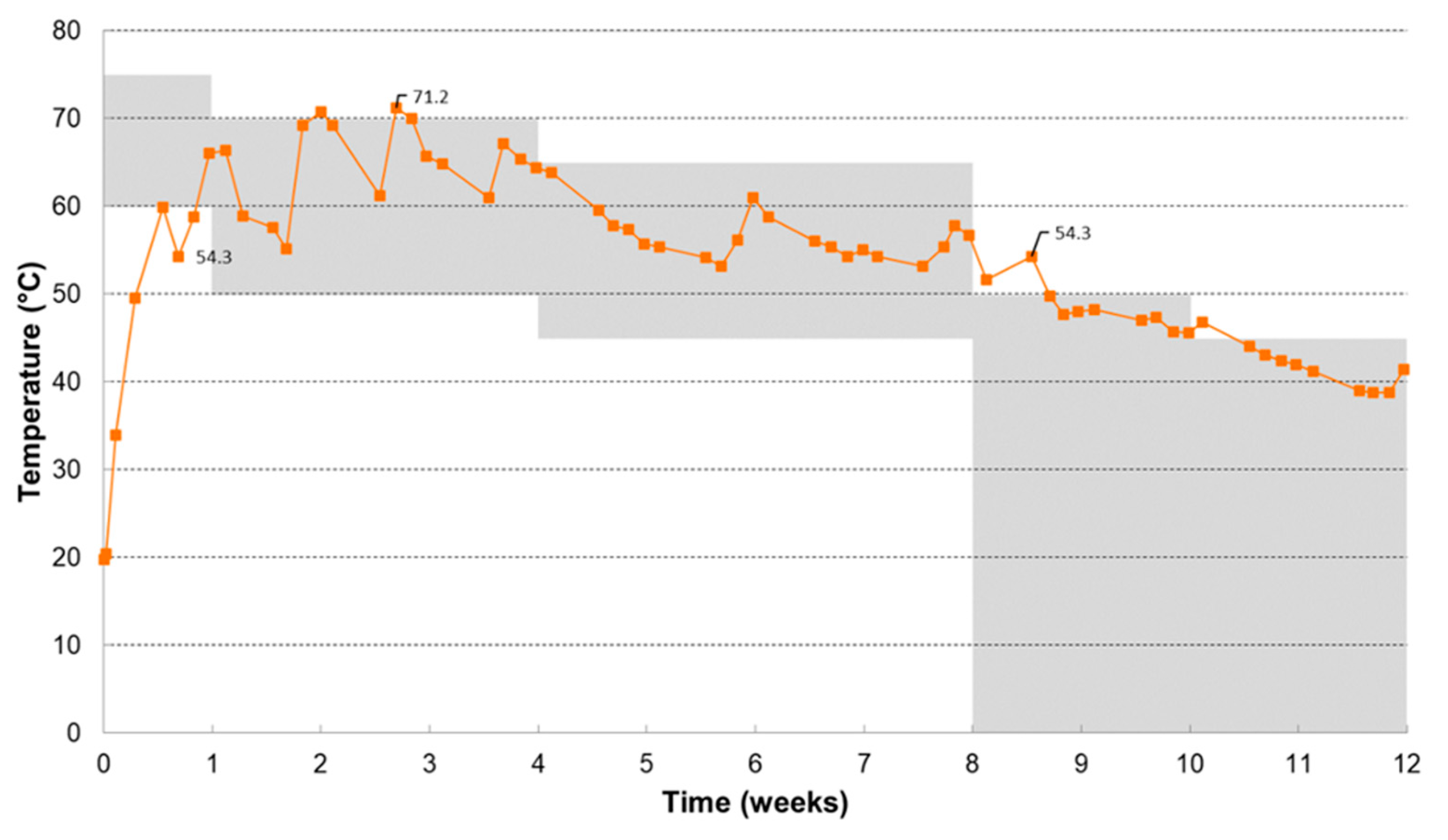

Figure 1 shows the temperature evolution during the composting process and the prescribed temperature conditions. Each time when the temperature criteria were not fulfilled action was taken to maintain optimal temperature conditions. Also, during the composting process the bin was placed in different incubation rooms (at ambient temperature, at 40°C and at 45°C) to maintain optimal temperature conditions during the different time periods.

Elevated temperatures during the composting process were also caused by the turning of the contents of the bin, during which air channels and fungal flakes were broken up and moisture, microbiota and substrate were divided evenly. As such optimal composting conditions were re-established, resulting in higher activity and a temperature increase. The temperature profile showed an initial thermophilic phase and a mesophilic continuation, which is representative for industrial composting and therefore it can be concluded that the temperature conditions were fulfilled. The oxygen concentration in the exhaust air remained always above 10%. As such, good aerobic conditions can be guaranteed.

3. Discussion

3.1. Thermal Analysis of Composites

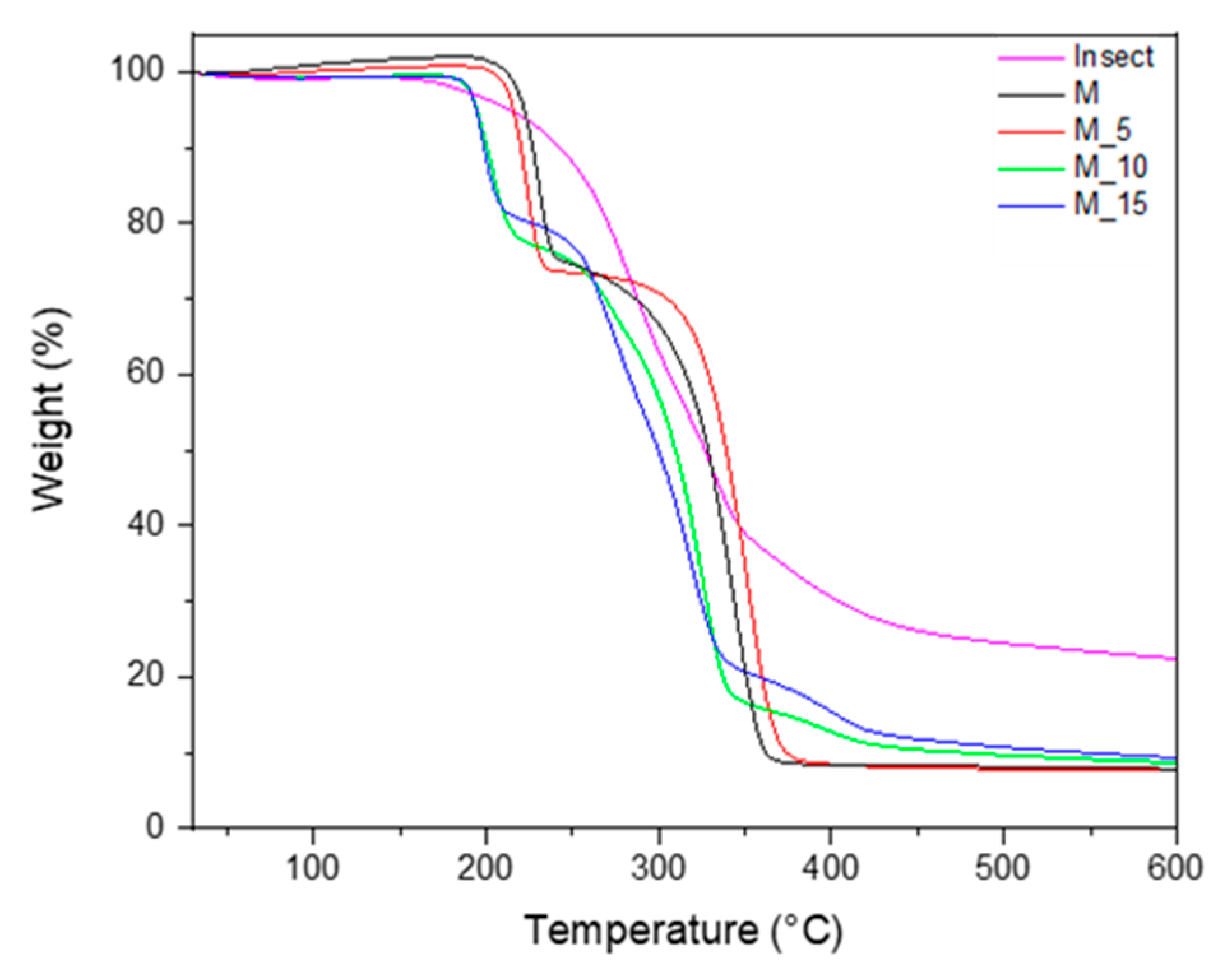

The thermal properties of bio-composites can be significantly influenced by the process of melt blending the polymers and incorporating the biomass fillers. To comprehensively evaluate these effects, we conducted a thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) reported in

Figure 2.

The PBSA/PHBV blend and the bio-composites containing insect fillers at concentrations of 5%, 10%, and 15% by weight exhibited a distinctive two-stage degradation pattern. In this thermal process, the initial peak degradation temperature can be attributed to PHBV, while the subsequent peak degradation temperature corresponds to PBSA. These findings are in line with what was observed in previous research [

28]. Notably, the thermal decomposition of the filler, which in this case consists of insects, exhibits a distinctive one-step degradation process at about 200 °C.

The analysis revealed specific thermal parameters for the materials: the onset degradation temperature related to PHBV and the temperature of degradation corresponding to PBSA were measured at about 190 °C and 250 °C, respectively. Notably, these values exhibited a decreasing trend as the filler loading increased, indicating that the addition of fibres had a diminishing effect on the thermal stability of the bio-composites.

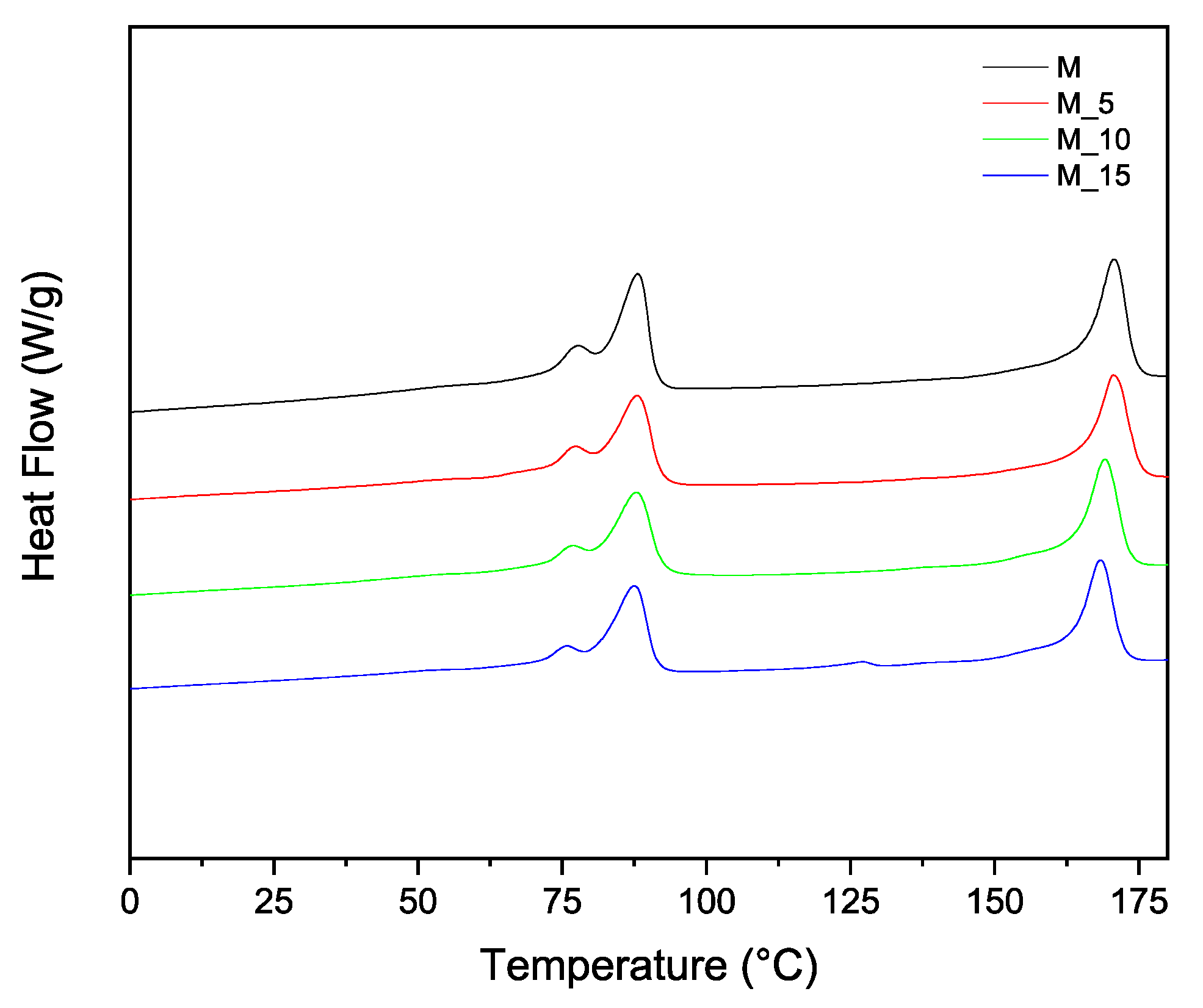

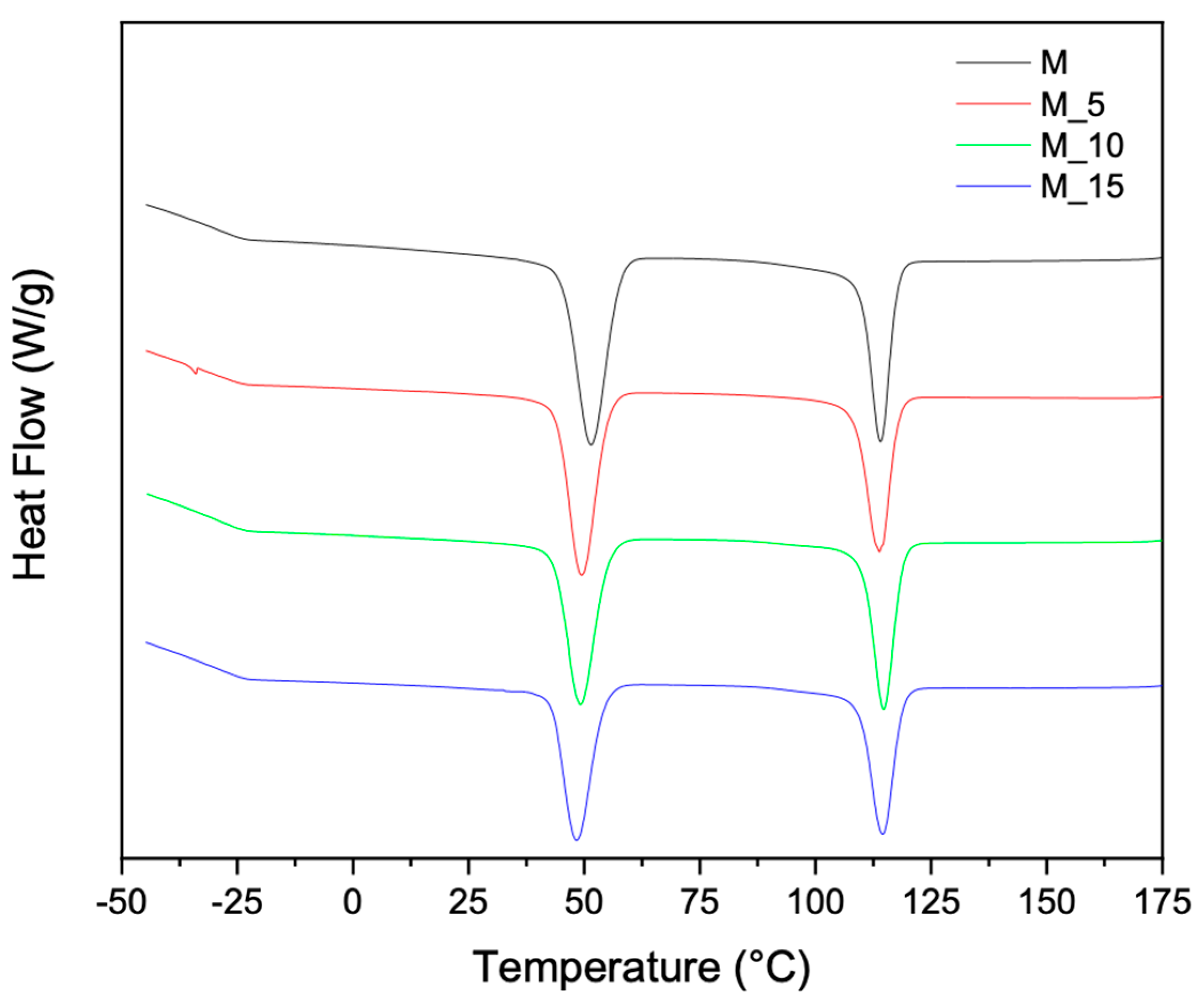

To implement the characterization of the thermal properties and structure of the materials, additional thermal analyses were performed, allowing the determination of melting and crystallization characteristics using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC). The second melting and cooling curves in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 respectively, offer further insights into how polymer blending and the introduction of fibrous materials influence the thermal properties of these biocomposites. This combined analysis ensures a clear and cohesive understanding of the thermal behaviour of the materials. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis was carried out on all samples and the results recorded during the second heating are summarised in

Figure 3.

Table 3.

Thermal data, from DSC analysis, of the investigated samples.

Table 3.

Thermal data, from DSC analysis, of the investigated samples.

| Sample |

Tm (°C) |

Tc (°C) |

Xc (%) |

| |

PBSA |

PHBV |

PBSA |

PHBV |

PBSA |

PHBV |

| M |

88.2 |

170.6 |

51.5 |

113.1 |

49.8 |

60 |

| M_5 |

88 |

170.5 |

49.5 |

113.8 |

44.8 |

63.6 |

| M_10 |

87.8 |

169.1 |

49.2 |

114.7 |

42.6 |

66.2 |

| M_15 |

87.5 |

168.3 |

48.3 |

114.5 |

41 |

67.3 |

The PBSA/PHBV blend displayed two major melting phenomena (

Figure 3) and two melt crystallization phenomena,

Figure 4, corresponding to PBSA and PHBV, respectively. PHBV is a semi crystalline polymer with a glass transition temperature of around 5 °C and a melting temperature of 145-150°C [

28]. The PBSA/PHBV blend, PBSA, displayed double melting peaks, with the first less intense melting peak (Tm1) at 77.60°C and the second main melting peak (Tm2) at 87.40°C. PHBV displayed a single melting peak at 113 °C. The double melting behaviour of polymers, such as PBSA, has been widely reported in the literature. It is ascribed to the melt recrystallization of polymers during the heating process. Imperfect crystals may melt at lower temperatures, recrystallize, and subsequently melt at higher temperatures, leading to double melting peaks [

28,

29,

30,

31]. In general, the melting temperatures of PBSA and PHBV in the blend and the bio-composites containing the insect biomass occurred in the same range, with Tm1 for both PBSA and PHBV slightly decreasing with biomass filler loading.

The PBSA/PHBV blend had two melt recrystallization peaks, with the first melt recrystallization peak (Tc1) at 51.33 °C corresponding to PBSA and the second melt recrystallization peak (Tc2) at 113 °C corresponding to PHBV

Figure 4. The melt crystallization temperatures of PBSA shifted to lower temperatures with addition of the filler. This indicates that the crystallization of PBSA is restricted by the presence of the biomass due to the suppressed nucleation. On the contrary, in the case of PHBV, there is an increase in crystallinity with the addition of filler load. This behaviour is attributed to the interactions between the polymeric matrix and the filler, which promote a more ordered arrangement of polymer chains. As the filler content increases, it acts as a nucleating agent, encouraging the formation of crystalline regions within the composite.

This enhanced crystallinity positively influences the mechanical properties and thermal stability of the developed composites PHBV-based. It underscores the intricate relationship between filler concentration and crystallinity, a crucial consideration in tailoring composite materials for specific applications.

3.2. Mechanical and Rheological Analysis of Composites

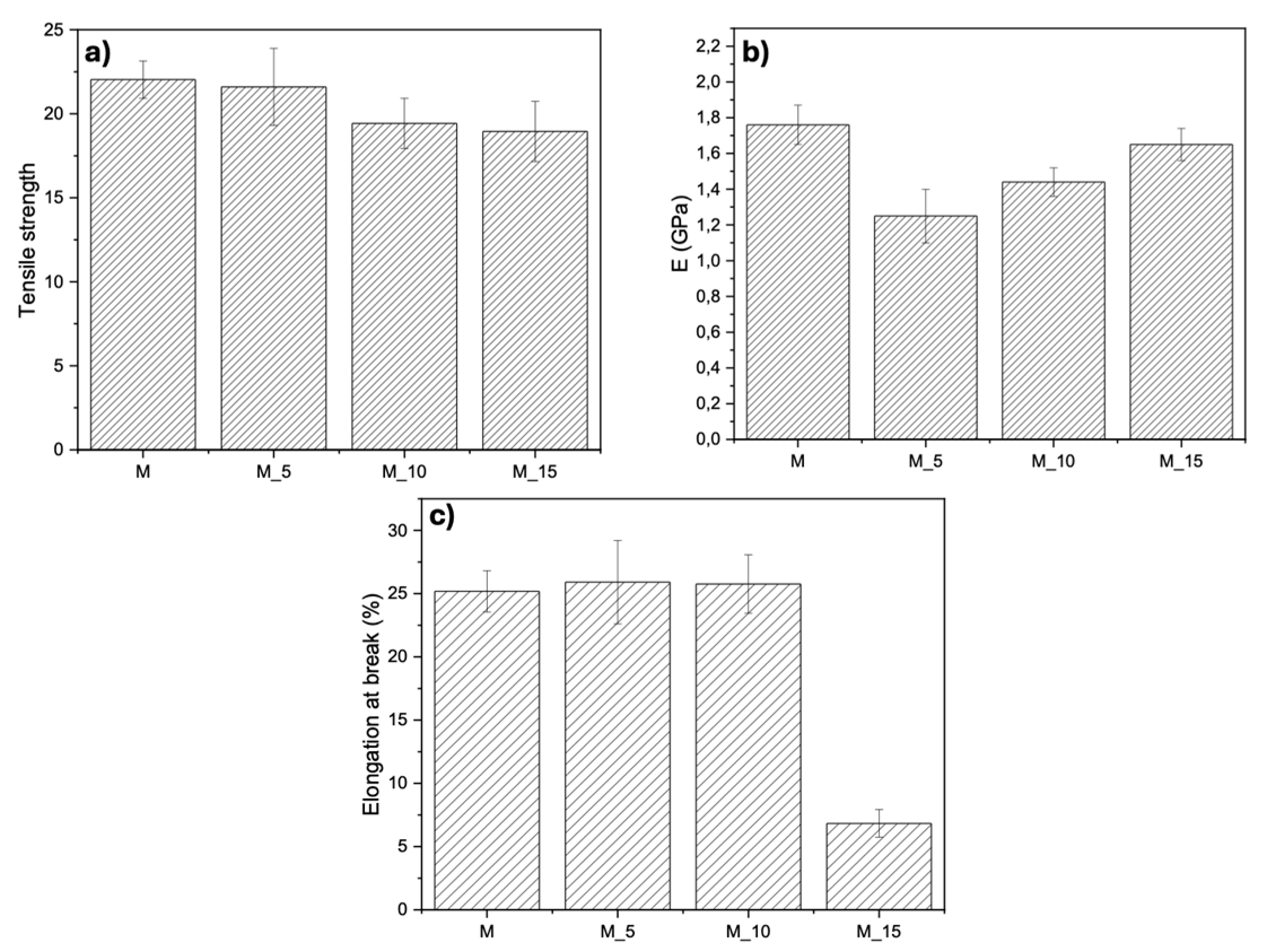

Results of tensile tests, shown in

Figure 5, reveal that as the filler content within the matrix increases, the mechanical properties remain relatively consistent. Tensile strength

Figure 5a), remained relatively unchanged as the filler load increased within the matrix. For the Young module

Figure 5b), a slight increase was observed when the fibre load was increased from 5% to 15%, however, this increase did not significantly impact the mechanical properties. Elongation at break

Figure 5c), showed a notable decrease from 5% to 10% of filler load, with a more drastic reduction occurring at 15%. This suggests that, in this scenario, the primary role of the filler is to act as a filler rather than reinforcing the composite, emphasizing the importance of considering filler content when tailoring material properties.

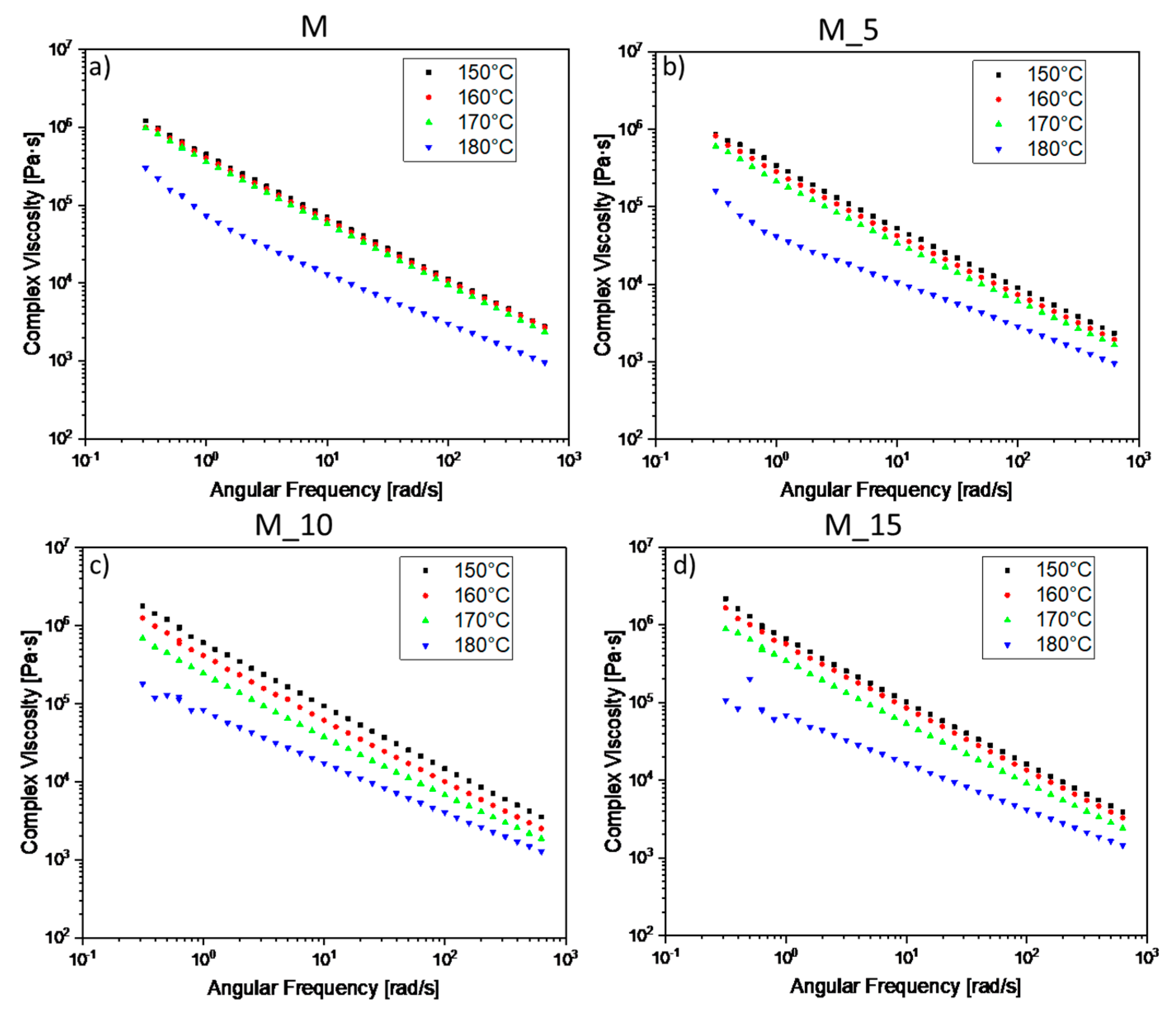

In

Figure 6 the PBSA-PHBV matrix between 150-160°C and 170°C exhibits overlapping viscosity behaviour, while a distinct change occurs at 180°C, signifying that fusion truly begins at this temperature. Although the material is not fully melted at 150-160°C and 170°C, the viscosity does not change as significantly with temperature in these ranges. In the case of sample M_5, viscosities start to differentiate minimally, with a notable increase in viscosity values at 180 °C. For sample M_10, viscosities begin to determine, with the lowest value at 180 °C, and the values at 150-160-170 °C are distinguishable. Sample M_15 shows an intermediate behaviour between M_5 and M_10, with values at 150-160°C very close, while samples at 170 and 180°C are markedly different.

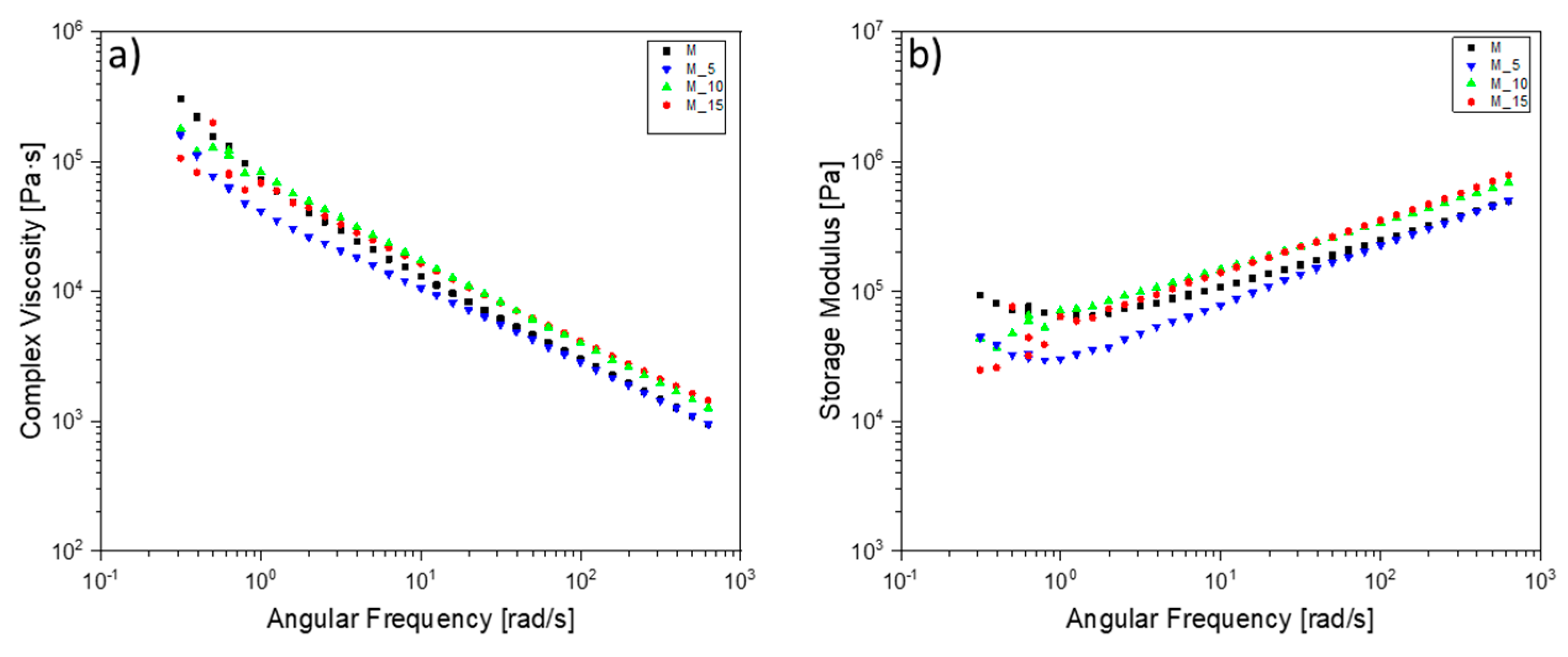

Figure 7 shows values for a blend of M_10 and M_15 that are similar, especially in the higher angular frequency range. The pure matrix exhibits a more pronounced shear-thinning behaviour compared to the others, while the M_5 blend shows a lower viscosity value than the other blends up to a range of average angular frequencies, then aligns with the matrix values at high angular frequencies.

At the melting temperature of 180 °C, the storage modulus exhibits a noticeable deviation from the normal behaviour in the modulus curve for both M and M_5 at low angular frequencies. This implies potential material degradation, likely associated with the matrix itself, particularly concerning the degradation of PHBV. In contrast, for samples M_10 and M_15, this degradation seems to be mitigated by the reinforcing effect of the filler, effectively concealing this degradation effect.

3.3. Morphological Analysis of Composites

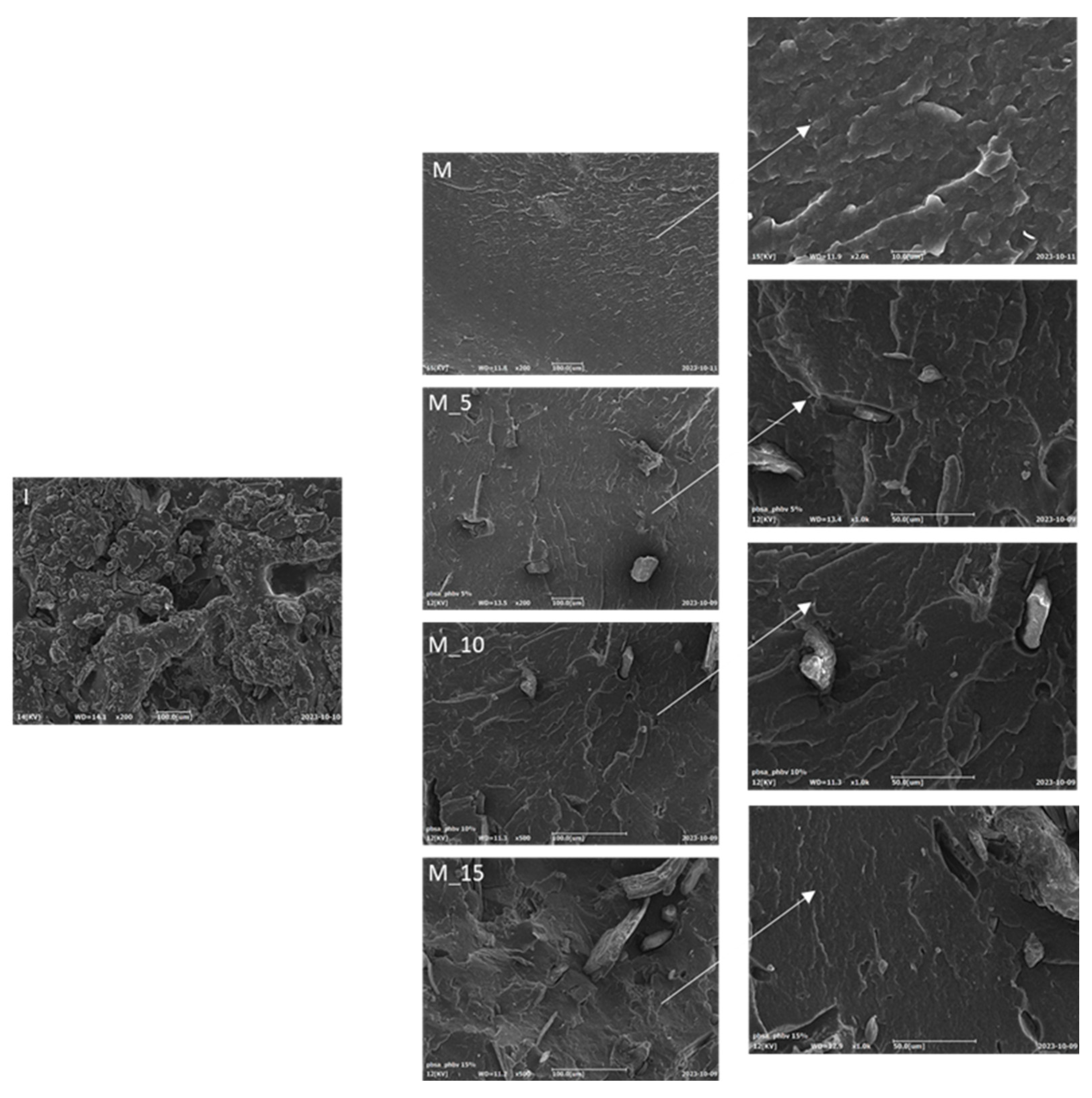

Conducting a morphological analysis is a pivotal step in assessing the efficacy of insect fillers' dispersion within the polymeric matrix and comprehending the interactions between the matrix and fillers. This analysis involves a detailed examination of the fractured surfaces of the specimens, providing critical insights into the structure and composition of these composites. The SEM images presented in

Figure 8 reveals key observations. SEM analysis of the filler added to the matrix has revealed its uneven morphology. Specifically, it appears in the form of flakes and short fibres, which suggests a lack of uniformity in its structure. This detailed examination provides valuable insights into the filler's characteristics within the composite. The surface morphology of the pure matrix a (M) appears exceptionally smooth. This observation holds across all SEM images, irrespective of the filler loading, signifying a consistent and uniform distribution of (I) fillers throughout the thermoplastic matrix. Notably, the biocomposite containing 15 wt% of filler stands out due to its remarkable dispersion within the matrix, showcasing an exceptionally even distribution.

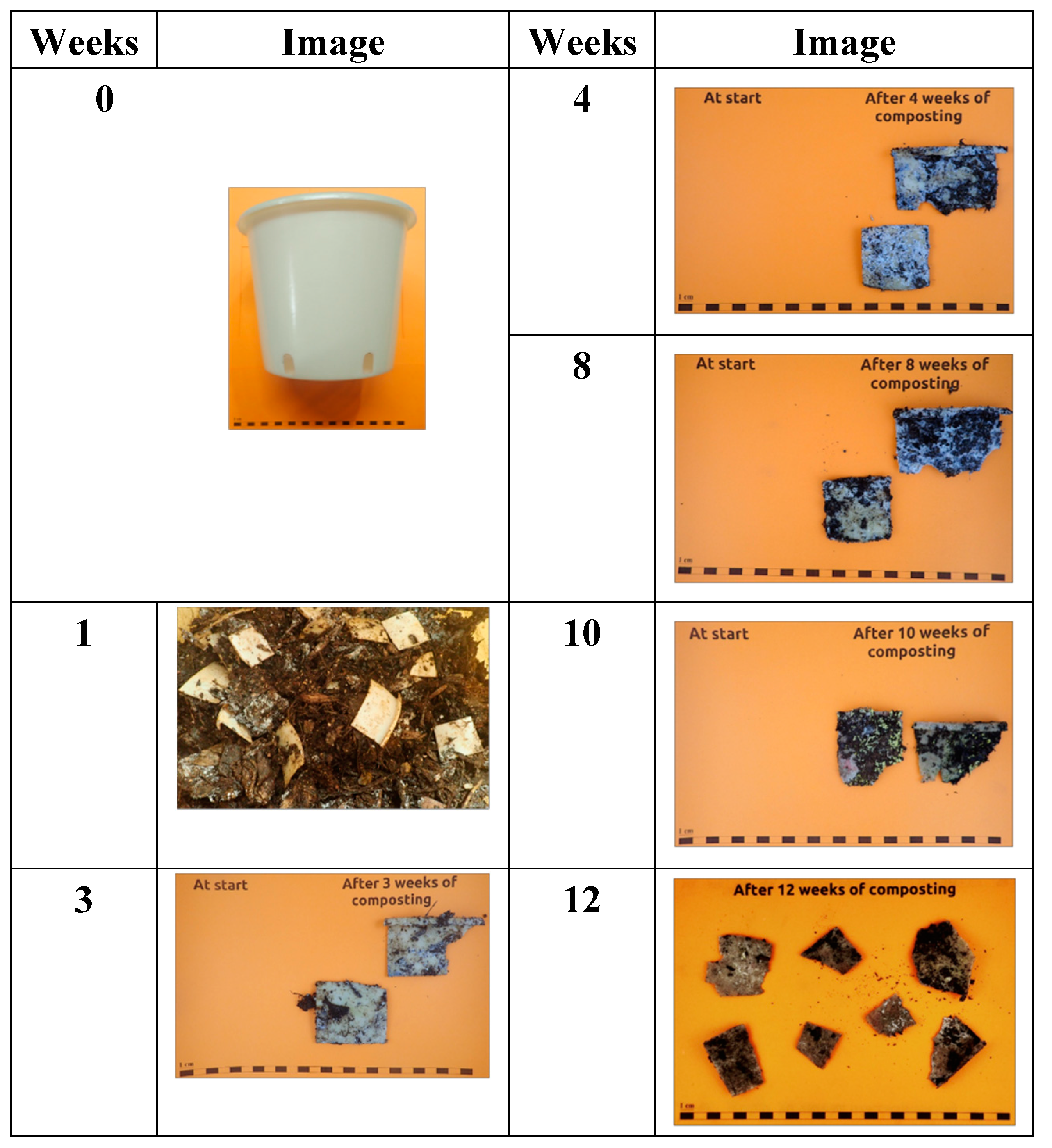

3.4. Disintegration in Compost

The disintegration of PBSA/PHBV pot (thickness: ± 1.55 mm (bottom), ± 1.56 mm (sidewall)), cut into 5 cm × 5 cm pieces, is reported in

Figure 9.

After one week in the composting process the samples test material was abundantly present and mostly intact, then at week 3 the material turned very fragile with cracks and tear After 4 weeks was noted even the growth of fungi on sample surfaces, after 8 week large presence of fungi was observed but the pieces of materials remained mainly intact, after 10 weeks, tears increased but after 12 weeks still a lot of large test material pieces could be retrieved. Thus, with the present thickness the pot would not pass the standard for compost ability failing in disintegration step. However, by reducing the thickness of the pots this requirement might still be fulfilled.

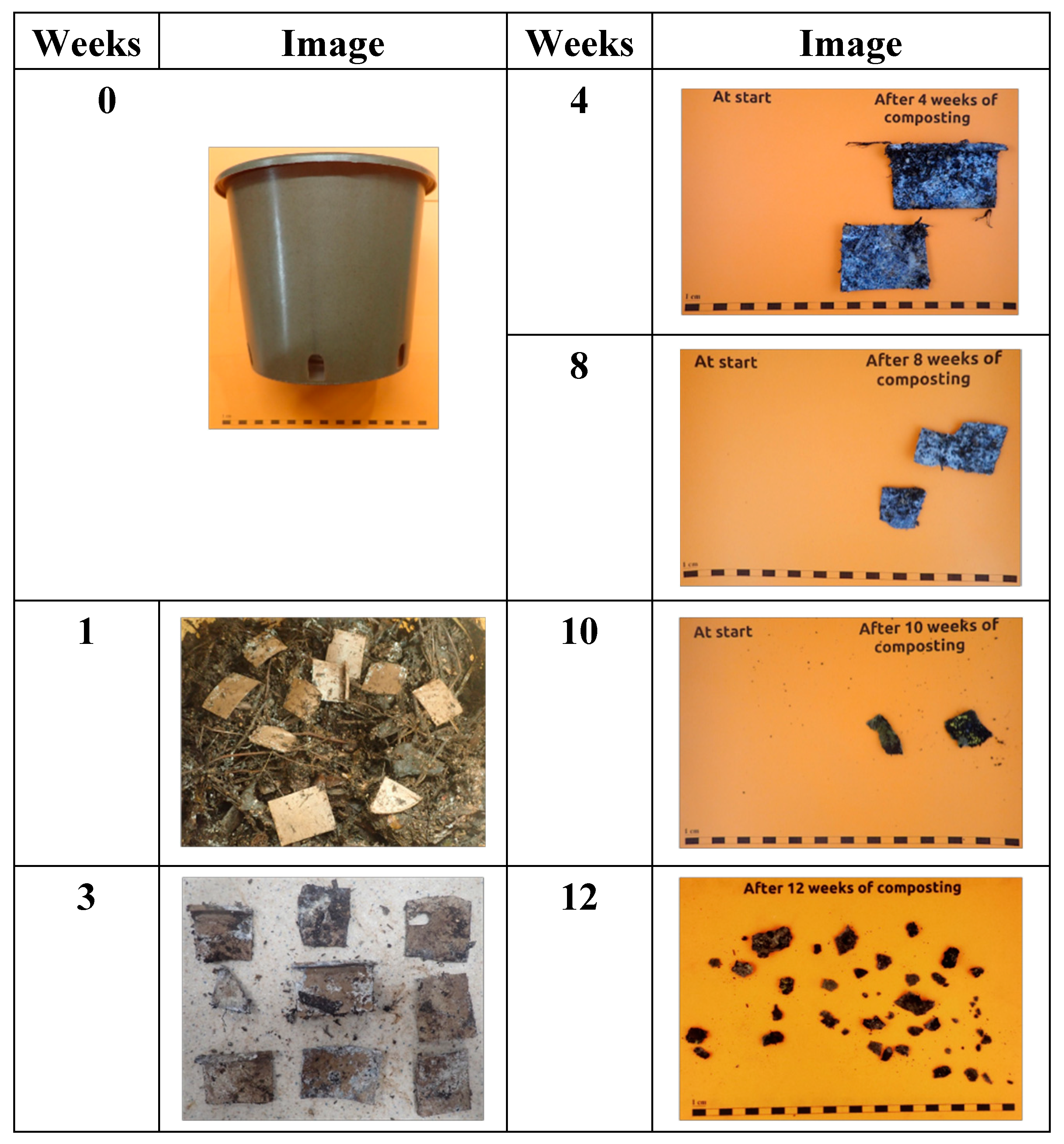

In

Figure 10 is reported the visual observation of PBSA/PHBV/15%insect powder pot (thickness: ± 1.52 mm bottom, ± 1.60 mm sidewall), cut into 5 cm × 5 cm pieces. After one week in the composting process the samples test material was abundantly present and mostly intact, then at week 3 the material turned very fragile and at 4 weeks was noted the growth of fungi but still the material was mostly intact. After 8 weeks large presence of fungi was observed and the test material had mostly fallen apart into pieces of variable size., after 10 weeks material had completely fallen apart into pieces of variable size. At 12 weeks only a few small pieces of test item could be retrieved. Thus, with the presence of the biomass in the composite the pots with current thickness plenty meet the requirements of the standard for compost ability in terms of disintegration.

5. Conclusions

Various prototype demonstrators, designed to enhance the value of byproducts within the framework of a circular economy approach, have been manufactured on an industrial scale and are currently undergoing validation. The targeted low value biomass in this process is the insect exoskeleton as the remaining after protein extraction, for animal feed. Extrusion processing, conducted at both laboratory and industrial scales, has affirmed the suitability of insect powder as a filler in biodegradable polymeric matrices. This includes maintaining thermal stability, morphological integrity, and adequate mechanical properties necessary for the industrial production of demonstrators, such as plant pots currently undergoing validation for their performance in plant growth. The production of the pots has proceeded seamlessly, aligning with industrial production cycles. At the end of the disintegration test for polymeric matrix with no filler, after 3 months, still quite a lot of large test item pieces were retrieved and therefore it can be concluded that the disintegration was insufficient. While when the insect filler was present at the end of the disintegration test in compost only some few small pieces were retrieved allowing the material to pass the disintegration tests requirements. Thus, the presence of the filler has a relevant effect in promoting the material degradability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Patrizia Cinelli; Methodology, Norma Mallegni and Vito Gigante; formal analysis, Damiano Rossi; investigation, Steven Verstichel, Marco Sandroni, Neetu Malik; resources, Maurizia Seggiani, Sara Filippi, Andrea Lazzeri; data curation, Miriam Cappello; writing—original draft preparation Norma Mallegni, Vito Gigante; writing—review and editing, Patrizia Cinelli; supervision, Maurizia Seggiani; funding acquisition, Patrizia Cinelli. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has received funding from the Bio Based Industries Joint Undertaking (JU) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme grant agreement “GA887648” project RECOVER “Development of innovative biotic symbiosis for plastic biodegradation and synthesis to solve their end of life challenges in the agriculture and food industries. The JU receives support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and the Bio Based Industries Consortium.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the company Nutrinsect srl, Italy, for providing insect exoskeleton and the company LCI/FEMTO Engineering, San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Italy for injection moulding the pots on industrial scale.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN Environment Programme, access 24.02.2025; https://www.unep.org/interactives/beat-plastic-pollution/.

- Nath, D.; Misra, M.; Al-Daoud, F.; Mohanty, A.K. Studies on Poly(Butylene Succinate) and Poly(Butylene Succinate- Co -Adipate)-Based Biodegradable Plastics for Sustainable Flexible Packaging and Agricultural Applications: A Comprehensive Review. RSC Sustainability 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .

- Fujimaki, T. Processability and Properties of Aliphatic Polyesters, “BIONOLLE”, Synthesized by Polycondensation Reaction. Polym Degrad Stab 1998, 59, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratto, J.A.; Stenhouse, P.J.; Auerbach, M.; Mitchell, J.; Farrell, R. Processing, Performance and Biodegradability of a Thermoplastic Aliphatic Polyester/Starch System. Polymer (Guildf) 1999, 40, 6777–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, M.; Rossi, D.; Filippi, S.; Cinelli, P.; Seggiani, M. Wood Residue-Derived Biochar as a Low-Cost, Lubricating Filler in Poly(Butylene Succinate-Co-Adipate) Biocomposites. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasirajan, S.; Ngouajio, M. Polyethylene and Biodegradable Mulches for Agricultural Applications: A Review. Agron Sustain Dev 2012, 32, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, G.; Carlozzi, P.; Seggiani, M.; Cinelli, P.; Vitolo, S.; Lazzeri, A. PHB-Rich Biomass and BioH2 Production by Means of Photosynthetic Microorganisms. Chem Eng Trans 2016, 49, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnicourt, E.; Cinelli, P.; Lazzeri, A.; Alvarez, V. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): Review of Synthesis, Characteristics, Processing and Potential Applications in Packaging. Express Polym Lett 2014, 8, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudesh, K.; Abe, H.; Doi, Y. Synthesis, Structure and Properties of Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Biological Polyesters. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2000, 25, 1503–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, B.; Halley, P.; Pratt, S.; Werker, A.; Lant, P. The Chemomechanical Properties of Microbial Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Prog Polym Sci 2013, 38, 536–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, G.; Klzll, G.; Bechelany, M.; Pochat-Bohatier, C.; Öner, M. Potential of Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Polymers Family as Substitutes of Petroleum Based Polymers for Packaging Applications and Solutions Brought by Their Composites to Form Barrier Materials. Pure and Applied Chemistry 2017, 89, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seggiani, M.; Cinelli, P.; Balestri, E.; Mallegni, N.; Stefanelli, E.; Rossi, A.; Lardicci, C.; Lazzeri, A. Novel Sustainable Composites Based on Poly(Hydroxybutyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) and Seagrass Beach-CAST Fibers: Performance and Degradability in Marine Environments. Materials 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deroiné, M.; Le Duigou, A.; Corre, Y.M.; Le Gac, P.Y.; Davies, P.; César, G.; Bruzaud, S. Seawater Accelerated Ageing of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate). Polym Degrad Stab 2014, 105, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnicourt, E.; Cinelli, P.; Lazzeri, A.; Alvarez, V. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): Review of Synthesis, Characteristics, Processing and Potential Applications in Packaging. Express Polym Lett 2014, 8, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, K.G.; Arizaga, G.G.C.; Wypych, F. Biodegradable Composites Based on Lignocellulosic Fibers-An Overview. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2009, 34, 982–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Hinrichsen, G. Biofibres, Biodegradable Polymers and Biocomposites: An Overview. Macromol Mater Eng 2000, 276–277, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A.K.; Fink, H.P.; Sain, M. Biocomposites Reinforced with Natural Fibers: 2000-2010. Prog Polym Sci 2012, 37, 1552–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, J.K.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, C.S.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Recent Advances in the Application of Natural Fiber Based Composites. Macromol Mater Eng 2010, 295, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.J.; Dhakal, H.N. Sustainable Biobased Composites for Advanced Applications: Recent Trends and Future Opportunities – A Critical Review. Composites Part C: Open Access 2022, 7, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. V.; Singh, A.; Sabyasachi Mohanty, S.; Kumar Srivastava, V.; Varjani, S. Organic Solid Waste: Biorefinery Approach as a Sustainable Strategy in Circular Bioeconomy. Bioresour Technol 2022, 349, 126835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seggiani, M.; Cinelli, P.; Mallegni, N.; Balestri, E.; Puccini, M.; Vitolo, S.; Lardicci, C.; Lazzeri, A. New Bio-Composites Based on Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Posidonia Oceanica Fibres for Applications in a Marine Environment. Materials 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strangis, G.; Rossi, D.; Cinelli, P.; Seggiani, M. Seawater Biodegradable Poly(Butylene Succinate-Co-Adipate)—Wheat Bran Biocomposites. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO 1133-1:2011; Plastics—Determination of the Melt Mass-Flow Rate (MFR) and Melt Volume-Flow Rate (MVR) of Thermoplastics—Part 1: Standard Method. ISO Copyright Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Malz, F.; Arndt, J.H.; Balko, J.; Barton, B.; Büsse, T.; Imhof, D.; Pfaendner, R.; Rode, K.; Brüll, R. Analysis of the Molecular Heterogeneity of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(Butylene Succinate-Co-Adipate) Blends by Hyphenating Size Exclusion Chromatography with Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Infrared Spectroscopy. J Chromatogr A 2021, 1638, 461819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsubishi Chemical Group. Available Online: Www.Pttmcc.Com/New/Download/BioPBS_FD92PM_and_FD92PB_Technical_ Data_Sheet_for_film.Pdf.

- Zembouai, I.; Amirouche, C. Blends Based on Polyhydroxyalkanoates : From the Elaboration to the Recycling Blends Based on Polyhydroxyalkanaotes: 2018, 1–3.

- Le Delliou, B.; Vitrac, O.; Castro, M.; Bruzaud, S.; Domenek, S. Characterization of a New Bio-Based and Biodegradable Blends of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) and Poly(Butylene-Co-Succinate-Co-Adipate). J Appl Polym Sci 2022, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Uribe, A.; Wang, T.; Pal, A.K.; Wu, F.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Injection Moldable Hybrid Sustainable Composites of BioPBS and PHBV Reinforced with Talc and Starch as Potential Alternatives to Single-Use Plastic Packaging. Composites Part C: Open Access 2021, 6, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masanabo, M.A.; Tribot, A.; Luoma, E.; Sharmin, N.; Sivertsvik, M.; Emmambux, M.N.; Keränen, J. Faba Bean Lignocellulosic Sidestream as a Filler for the Development of Biodegradable Packaging. Polym Test 2023, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.S.; Im, S.S. Melting Behavior of Poly(Butylene Succinate) during Heating Scan by DSC. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys 1999, 37, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).