Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

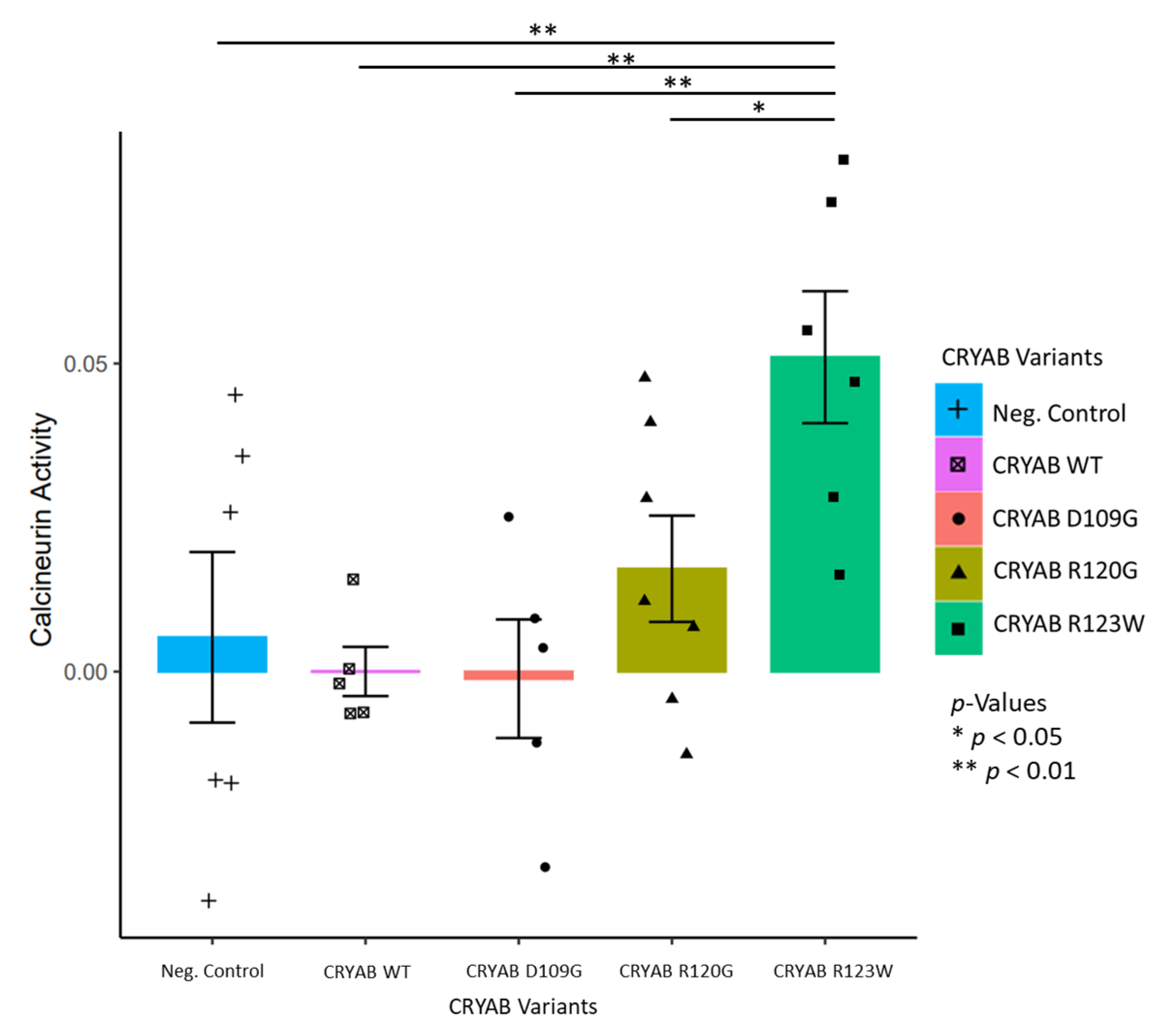

CRYABR123W Increases Calcineurin Activity

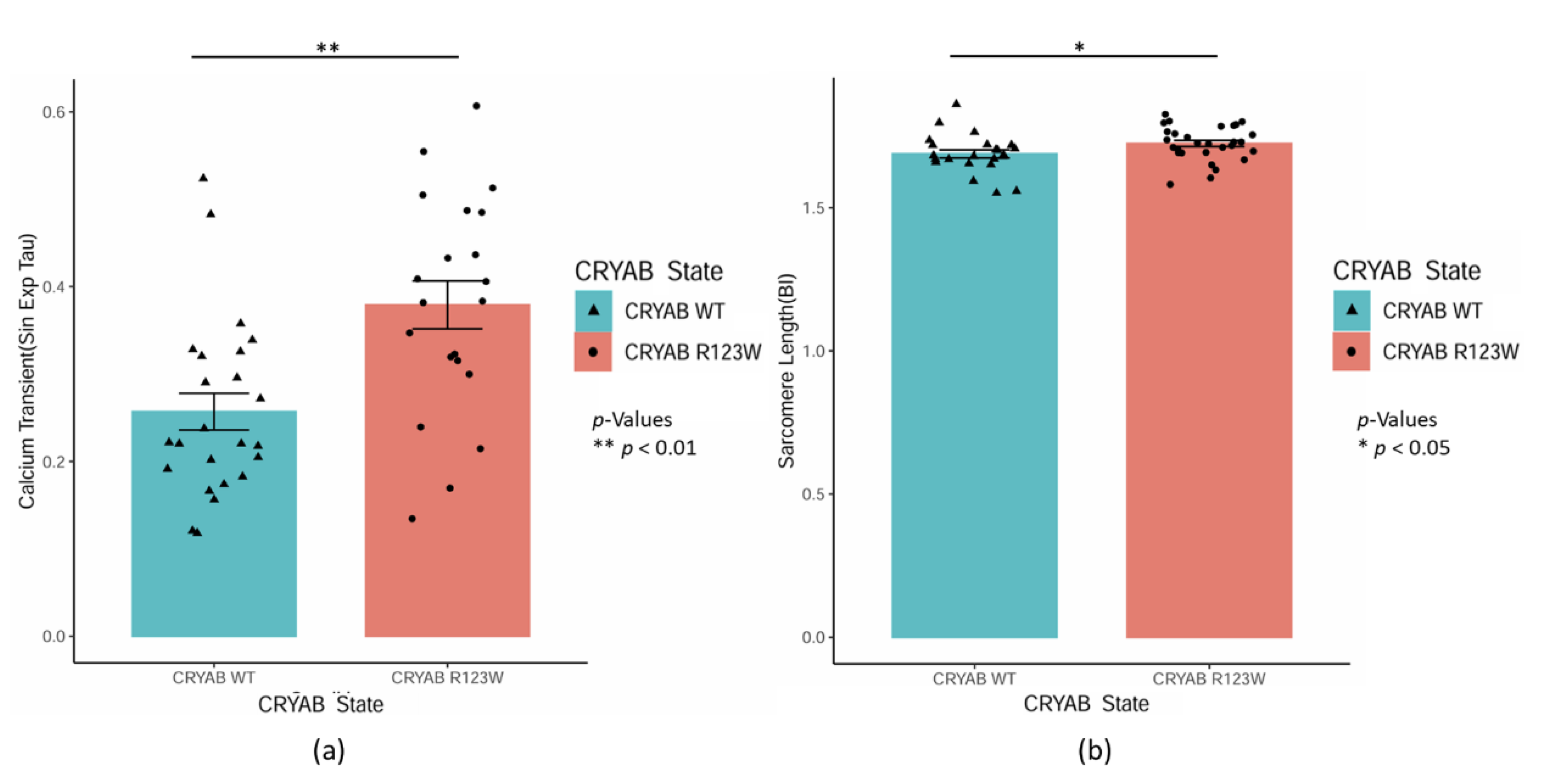

CRYABR123W Causes Impaired Calcium Reuptake and Myocyte Relaxation

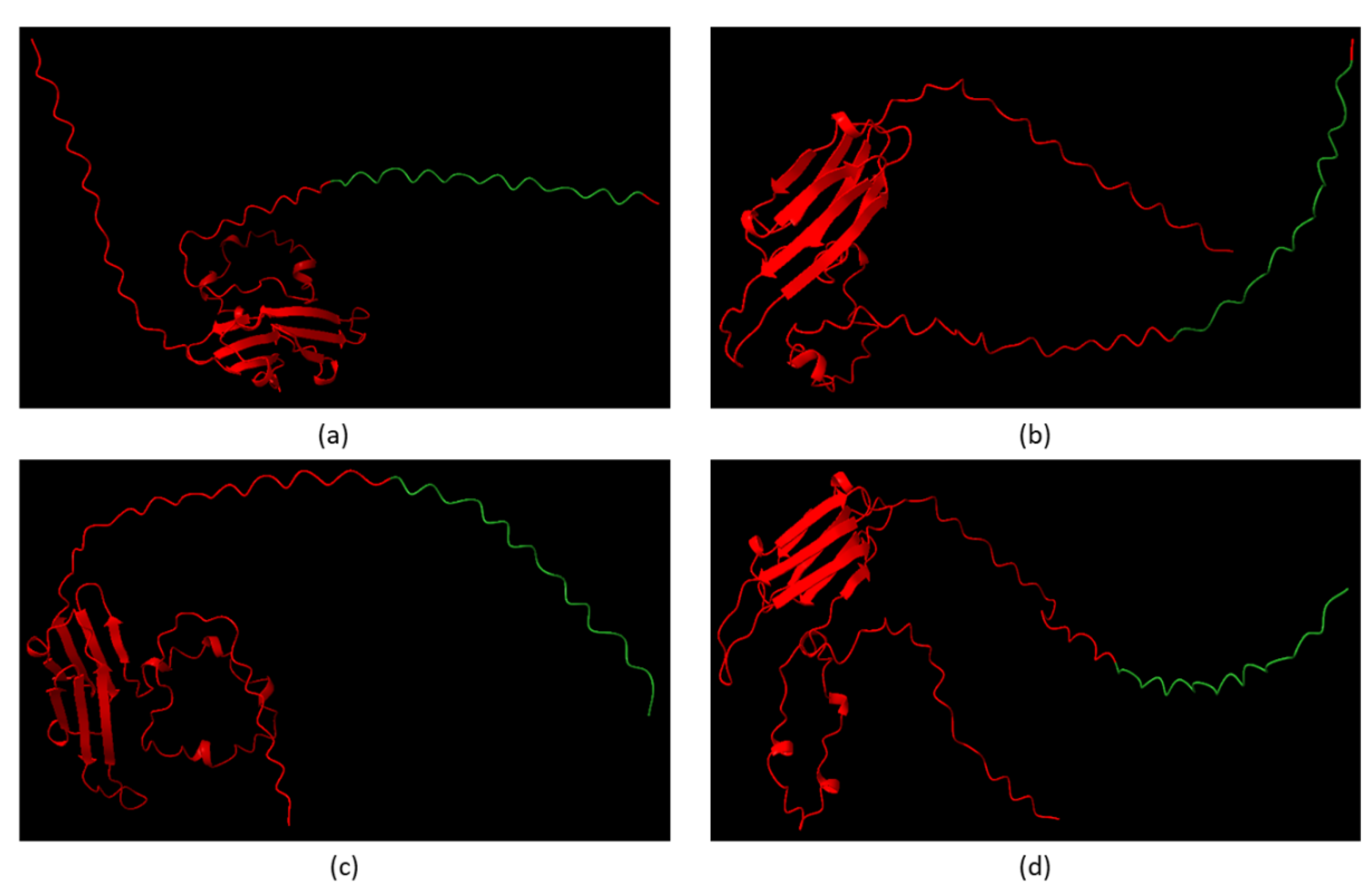

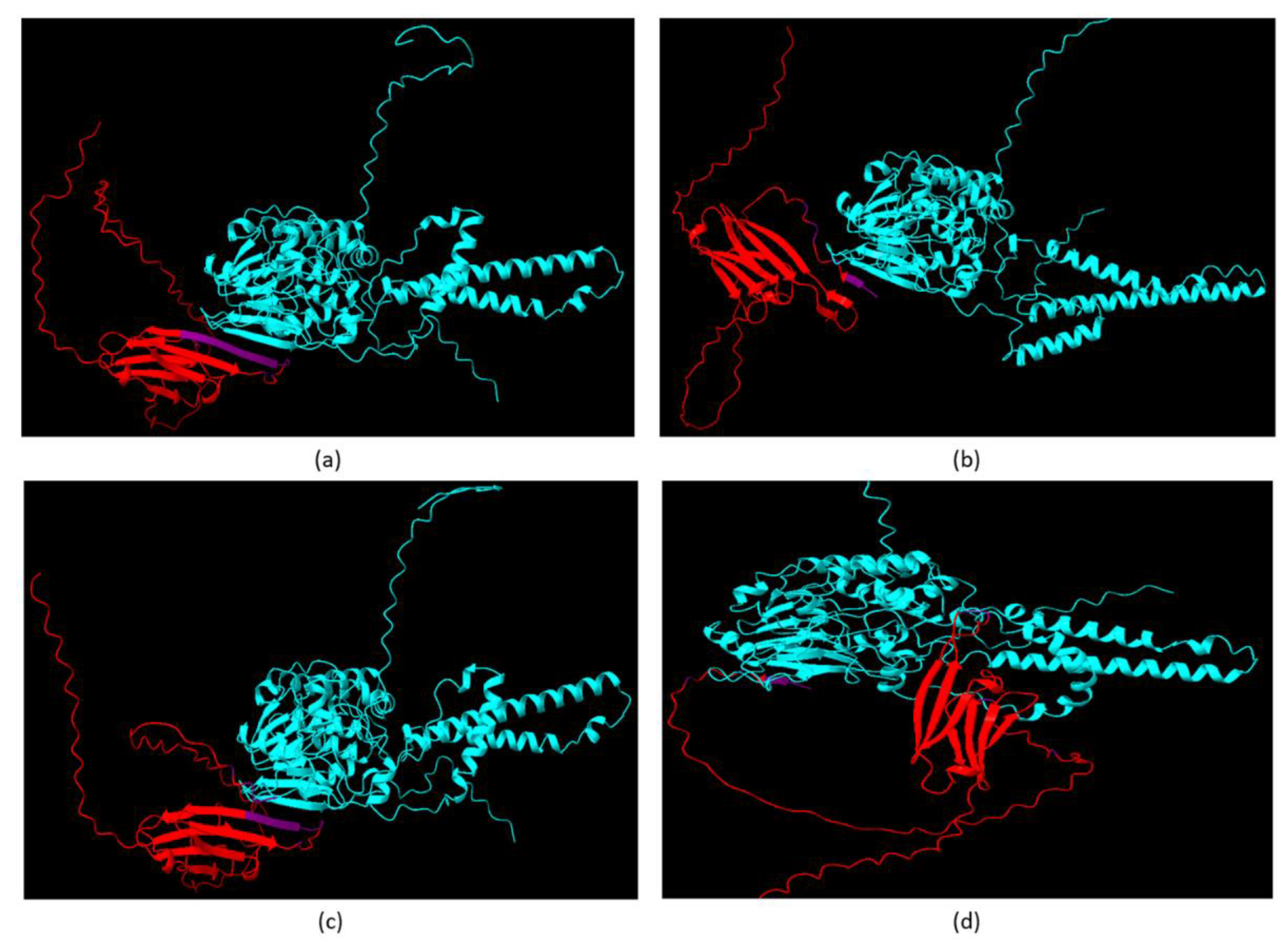

Alphafold Predicts CRYABR123W Binds to the Autoinhibitory Domain of Calcineurin

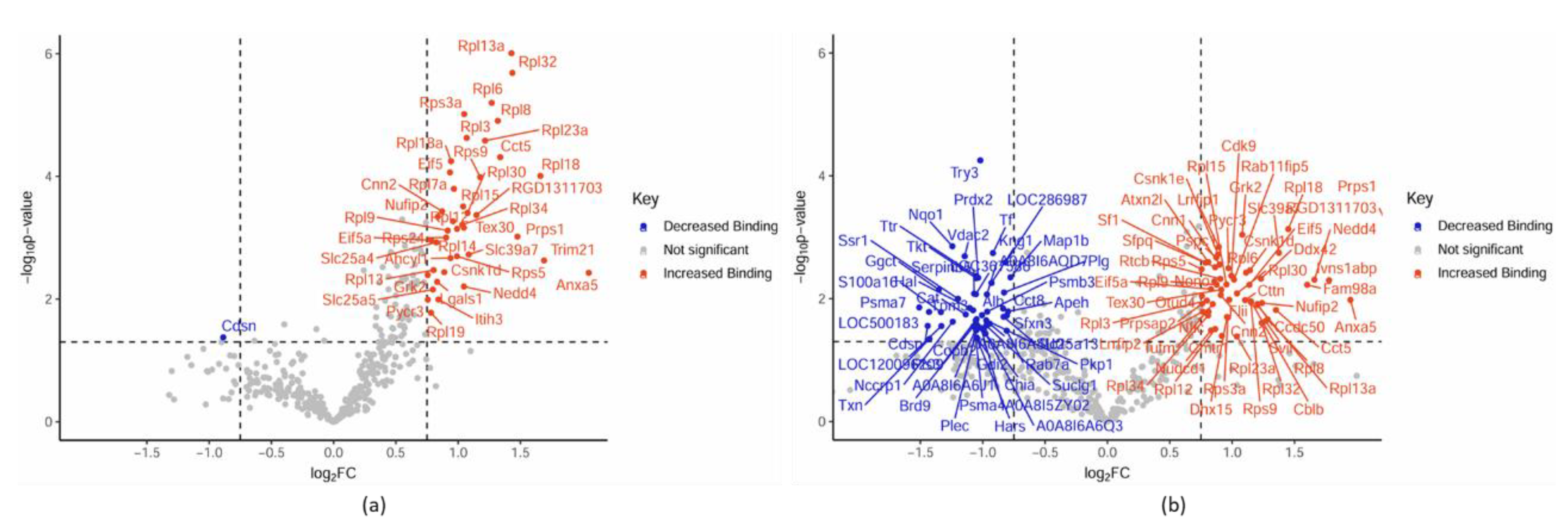

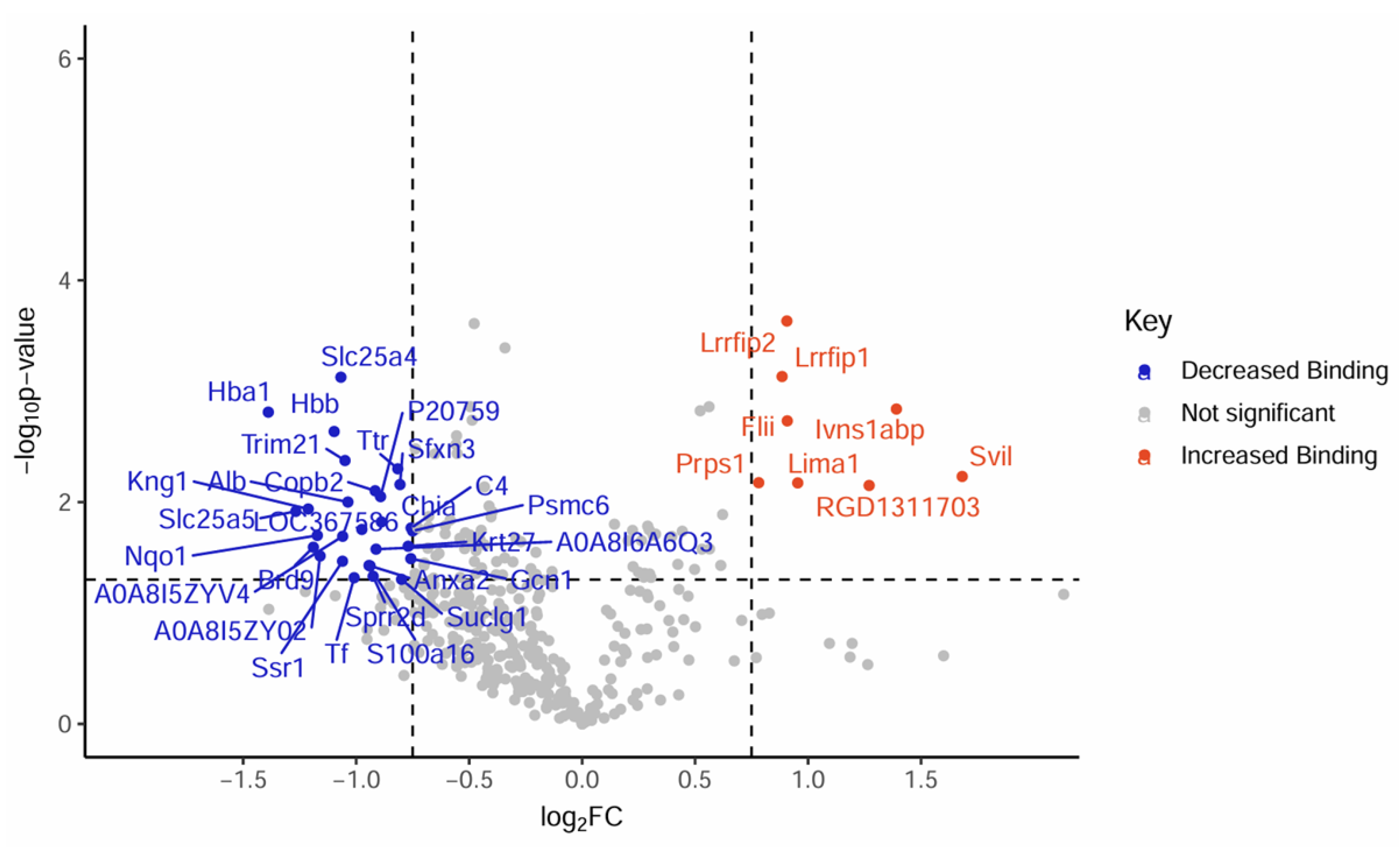

The CRYABR123W Protein Interactome Diverges from CRYAB and CRYABR120G

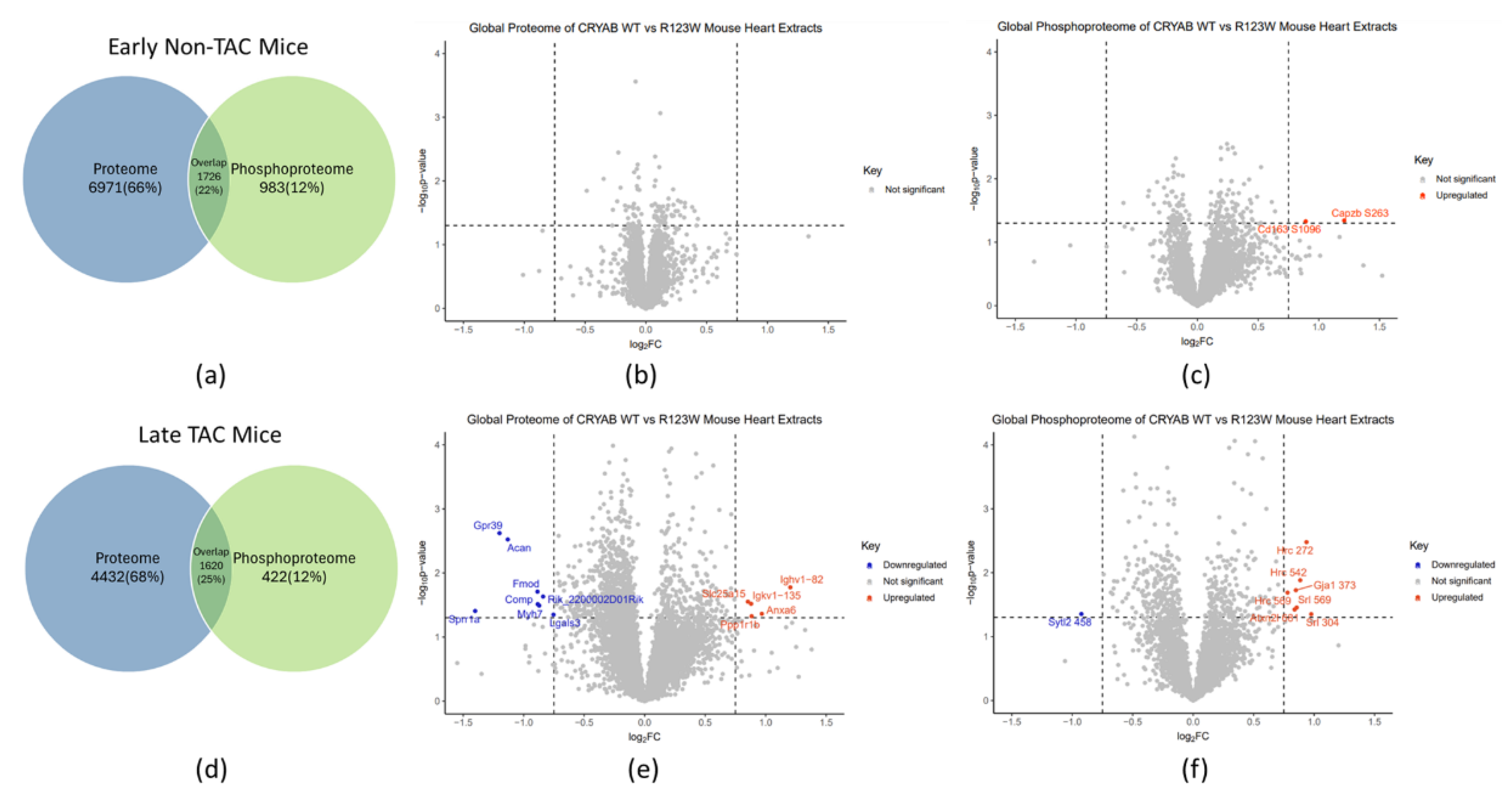

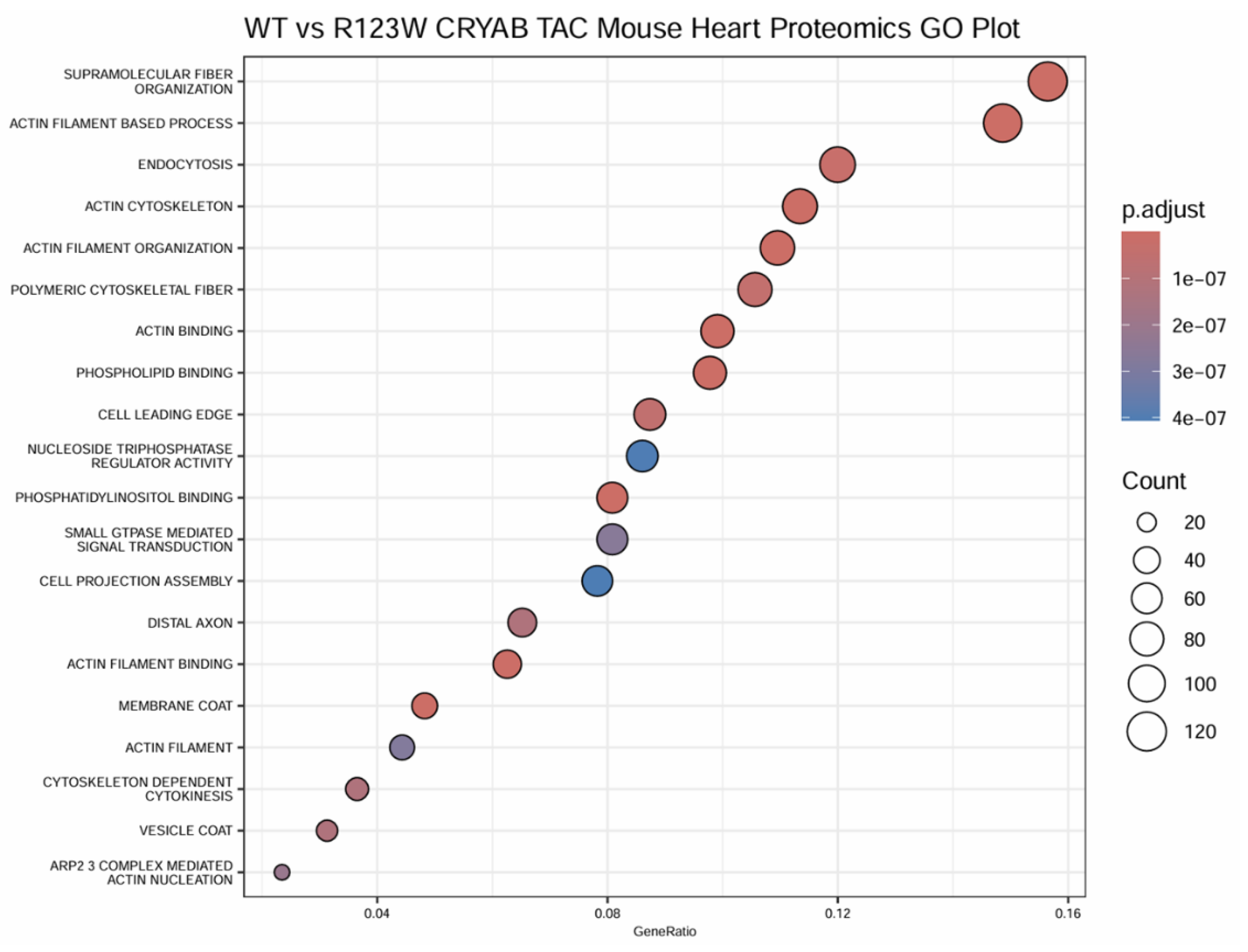

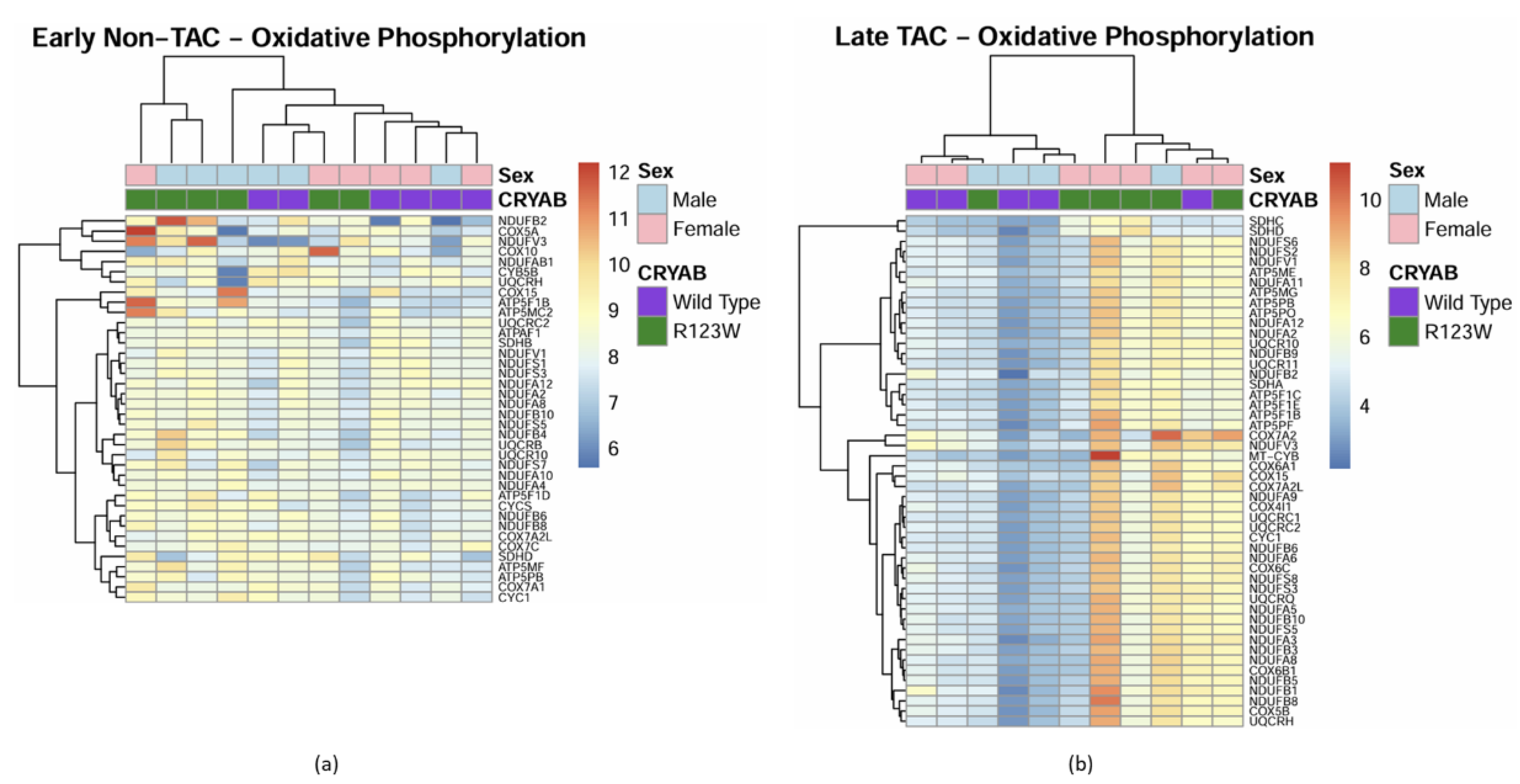

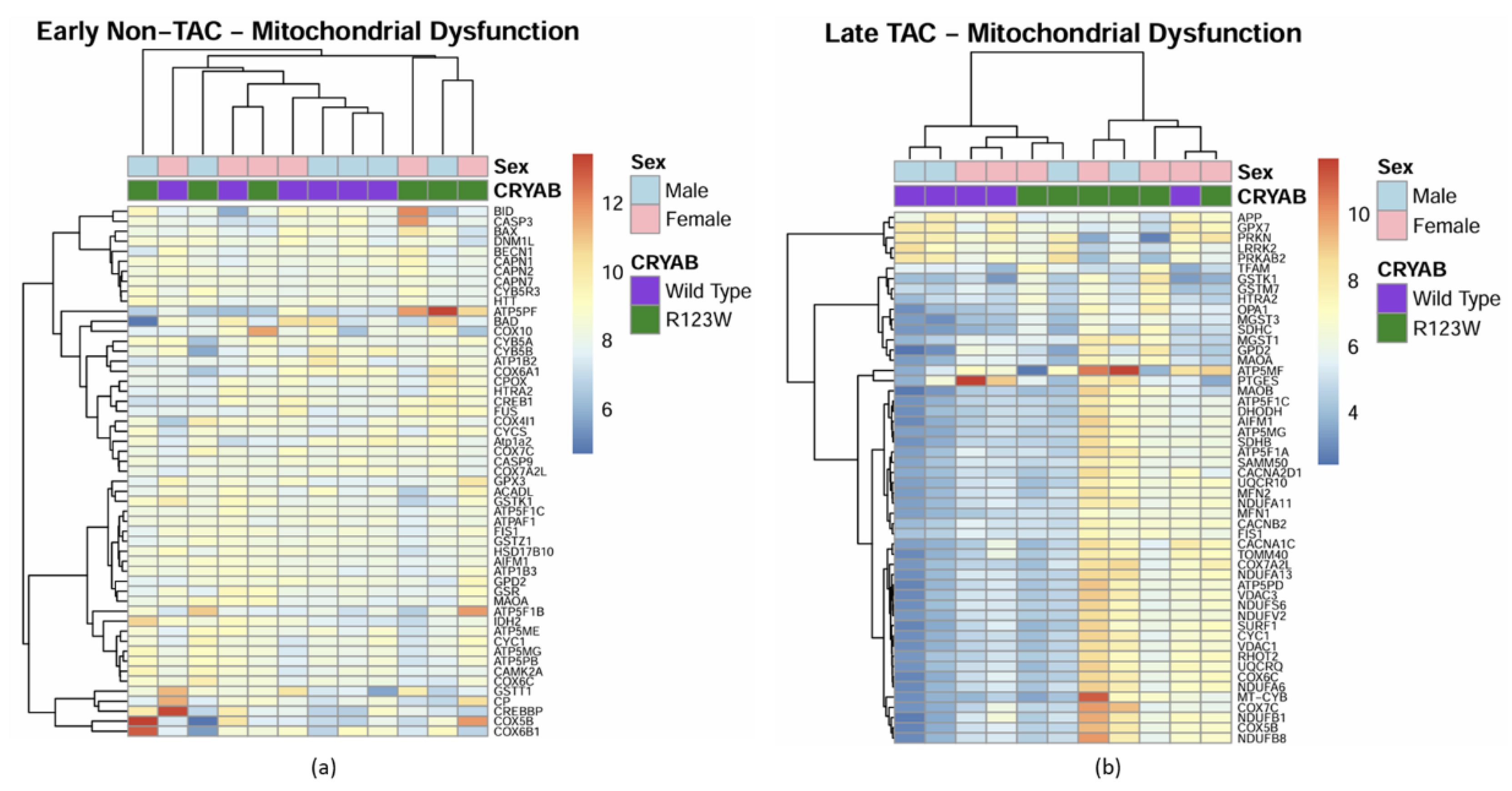

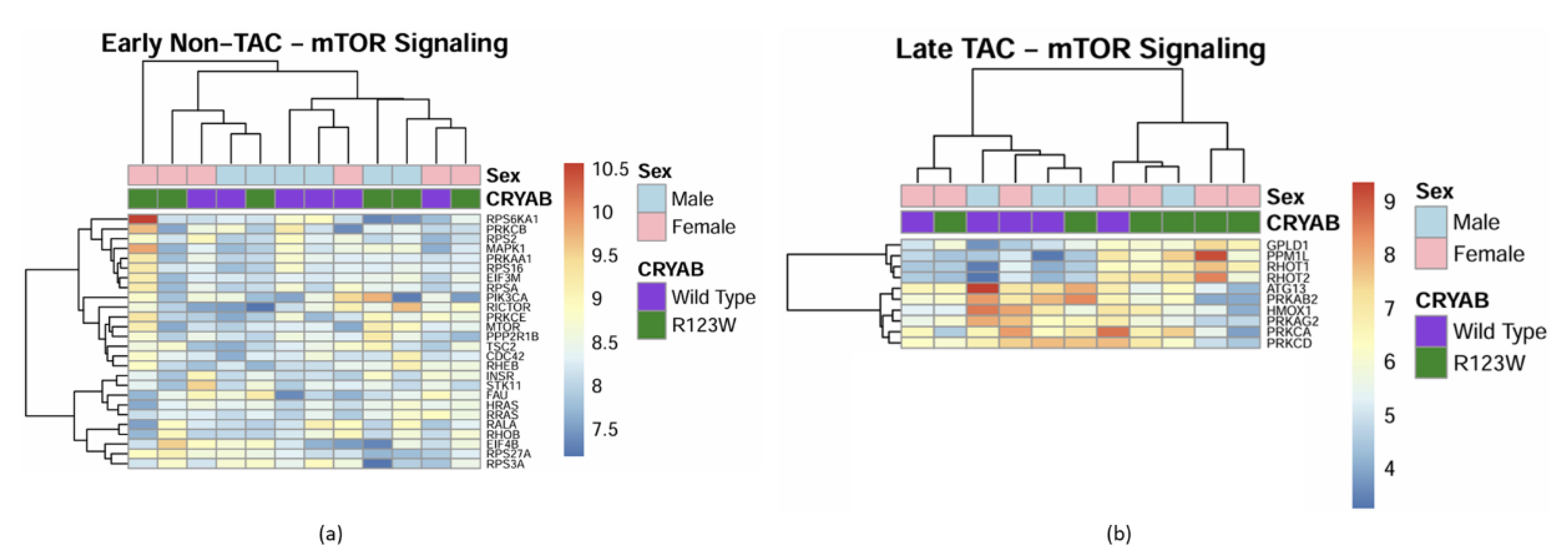

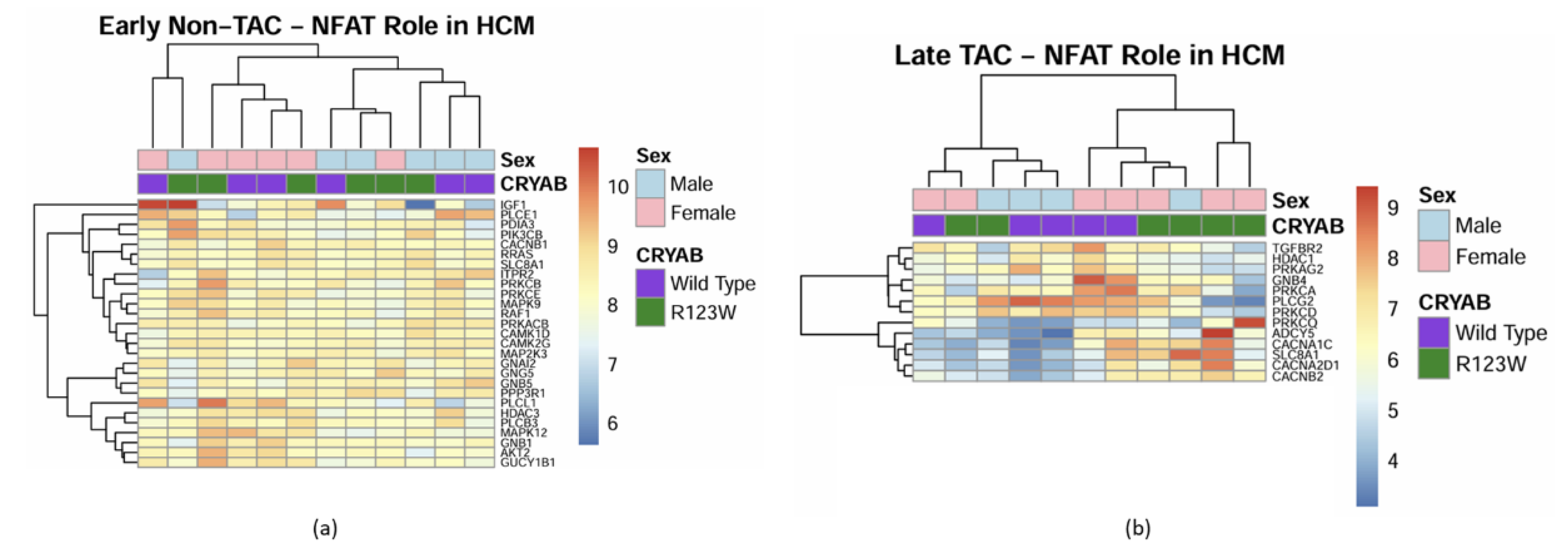

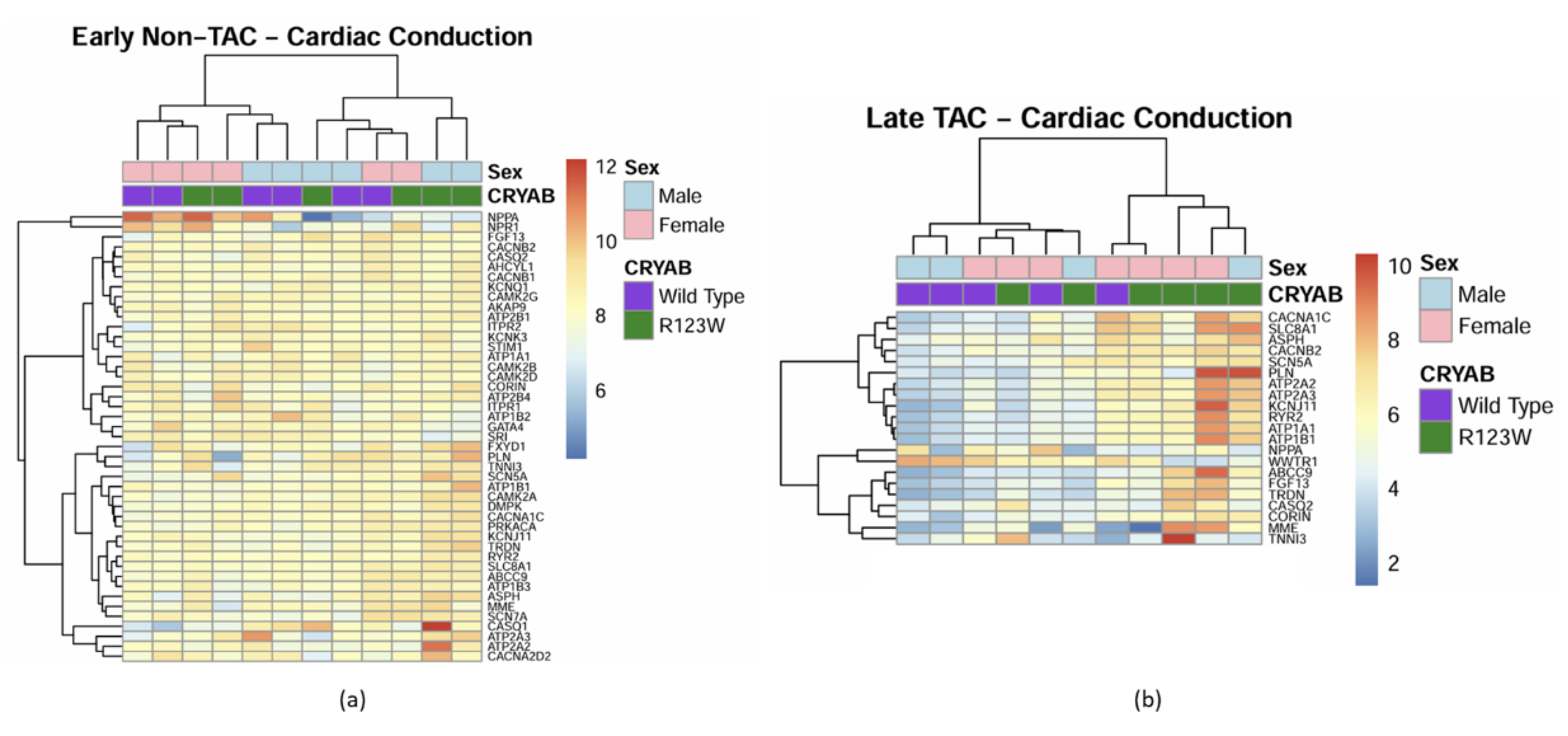

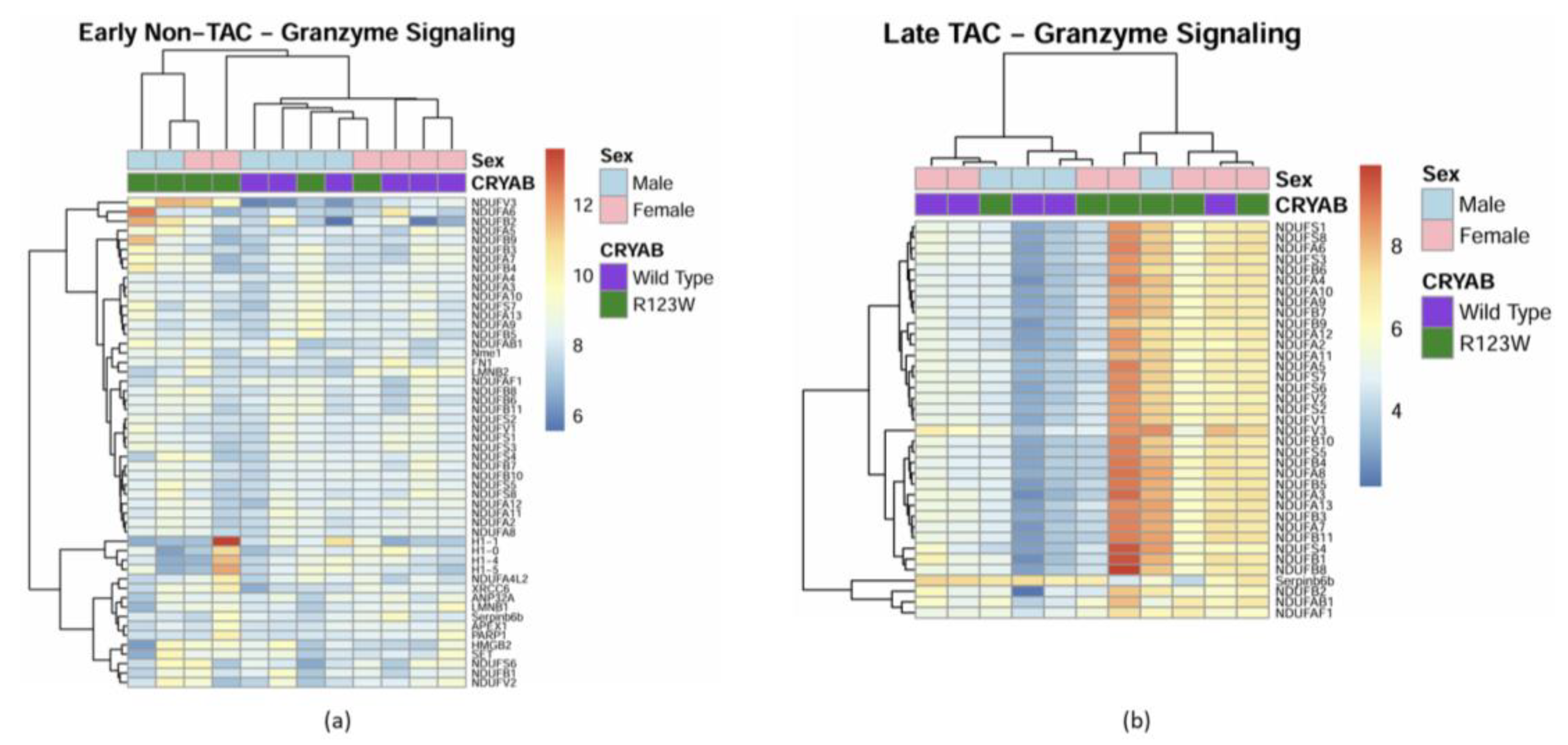

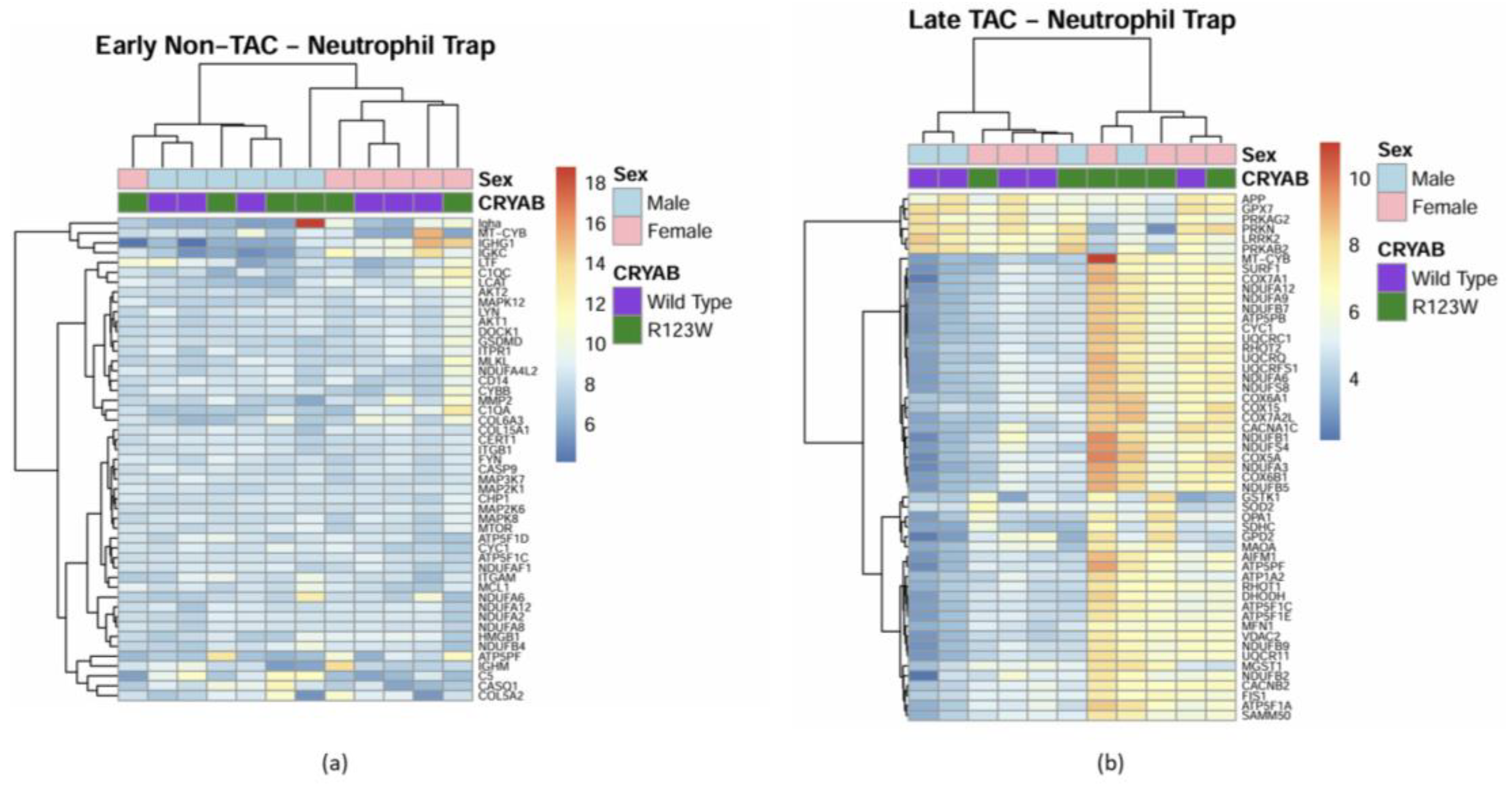

Global Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics Reveal Cytoskeletal, Metabolic, Immune and Cardiac Dysfunction in CRYABR123W Mouse Hearts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002 Mar 13;287(10):1308-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marian AJ, Roberts R. The molecular genetic basis for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001 Apr;33(4):655-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marian AJ. Modifier genes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2002 May;17(3):242-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Geisterfer-Lowrance AA, Kass S, Tanigawa G, Vosberg HP, McKenna W, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. A molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a beta cardiac myosin heavy chain gene missense mutation. Cell. 1990 Sep 7;62(5):999-1006. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins H, MacRae C, Thierfelder L, Chou YH, Frenneaux M, McKenna W, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. A disease locus for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy maps to chromosome 1q3. Nat Genet. 1993 Apr;3(4):333-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thierfelder L, Watkins H, MacRae C, Lamas R, McKenna W, Vosberg HP, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Alpha-tropomyosin and cardiac troponin T mutations cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a disease of the sarcomere. Cell. 1994 Jun 3;77(5):701-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Identifying sarcomere gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a personal history. Circ Res. 2011 Mar 18;108(6):743-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Watkins H, Ashrafian H, Redwood C. Inherited cardiomyopathies. N Engl J Med. 2011 Apr 28;364(17):1643-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013 Jan 19;381(9862):242-55. Epub 2012 Aug 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron BJ, Maron MS, Maron BA, Loscalzo J. Moving Beyond the Sarcomere to Explain Heterogeneity in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Apr 23;73(15):1978-1986. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ingles J, Burns C, Bagnall RD, Lam L, Yeates L, Sarina T, Puranik R, Briffa T, Atherton JJ, Driscoll T, Semsarian C. Nonfamilial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Prevalence, Natural History, and Clinical Implications. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017 Apr;10(2):e001620. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerull B, Klaassen S, Brodehl A. The genetic landscape of cardiomyopathies. Genetic Causes of Cardiac Disease. (2019):45–91. [CrossRef]

- Vicart P, Caron A, Guicheney P, Li Z, Prévost MC, Faure A, Chateau D, Chapon F, Tomé F, Dupret JM, Paulin D, Fardeau M. A missense mutation in the alphaB-crystallin chaperone gene causes a desmin-related myopathy. Nat Genet. 1998 Sep;20(1):92-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumarapeli AR, Su H, Huang W, Tang M, Zheng H, Horak KM, Li M, Wang X. Alpha B-crystallin suppresses pressure overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008 Dec 5;103(12):1473-82. Epub 2008 Oct 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bennardini F, Wrzosek A, Chiesi M. Alpha B-crystallin in cardiac tissue. Association with actin and desmin filaments. Circ Res. 1992 Aug;71(2):288-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholl ID, Quinlan RA. Chaperone activity of alpha-crystallins modulates intermediate filament assembly. EMBO J. 1994 Feb 15;13(4):945-53. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang K, Spector A. alpha-crystallin stabilizes actin filaments and prevents cytochalasin-induced depolymerization in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Eur J Biochem. 1996 Nov 15;242(1):56-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannous P, Zhu H, Johnstone JL, Shelton JM, Rajasekaran NS, Benjamin IJ, Nguyen L, Gerard RD, Levine B, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Autophagy is an adaptive response in desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Jul 15;105(28):9745-50. Epub 2008 Jul 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bhuiyan MS, Pattison JS, Osinska H, James J, Gulick J, McLendon PM, Hill JA, Sadoshima J, Robbins J. Enhanced autophagy ameliorates cardiac proteinopathy. J Clin Invest. 2013 Dec;123(12):5284-97. Epub 2013 Nov 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mitra A, Basak T, Datta K, Naskar S, Sengupta S, Sarkar S. Role of α-crystallin B as a regulatory switch in modulating cardiomyocyte apoptosis by mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum during cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial infarction. Cell Death Dis. 2013 Apr 4;4(4):e582. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chis R, Sharma P, Bousette N, Miyake T, Wilson A, Backx PH, Gramolini AO. α-Crystallin B prevents apoptosis after H2O2 exposure in mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012 Oct 15;303(8):H967-78. Epub 2012 Aug 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bagnéris C, Bateman OA, Naylor CE, Cronin N, Boelens WC, Keep NH, Slingsby C. Crystal structures of alpha-crystallin domain dimers of alphaB-crystallin and Hsp20. J Mol Biol. 2009 Oct 9;392(5):1242-52. Epub 2009 Jul 30. Erratum in: J Mol Biol. 2009 Dec 4;394(3):588. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganowsky A, Benesch JL, Landau M, Ding L, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Huang Q, Robinson CV, Horwitz J, Eisenberg D. Crystal structures of truncated alphaA and alphaB crystallins reveal structural mechanisms of polydispersity important for eye lens function. Protein Sci. 2010 May;19(5):1031-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mchaourab HS, Godar JA, Stewart PL. Structure and mechanism of protein stability sensors: chaperone activity of small heat shock proteins. Biochemistry. (2009) 48:3828–37. [CrossRef]

- Ito H, Okamoto K, Nakayama H, Isobe T, Kato K. Phosphorylation of alphaB-crystallin in response to various types of stress. J Biol Chem. 1997 Nov 21;272(47):29934-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacconi S, Féasson L, Antoine JC, Pécheux C, Bernard R, Cobo AM, Casarin A, Salviati L, Desnuelle C, Urtizberea A. A novel CRYAB mutation resulting in multisystemic disease. Neuromuscul Disord. 2012 Jan;22(1):66-72. Epub 2011 Sep 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodehl A, Gaertner-Rommel A, Klauke B, Grewe SA, Schirmer I, Peterschröder A, Faber L, Vorgerd M, Gummert J, Anselmetti D, Schulz U, Paluszkiewicz L, Milting H. The novel αB-crystallin (CRYAB) mutation p.D109G causes restrictive cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat. 2017 Aug;38(8):947-952. Epub 2017 Jun 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, van Hessem L, Jongbloed JD, de Walle HE, Capetanaki Y, van der Kooi AJ, van Langen IM, van den Berg MP, van Tintelen JP. Desmin-related myopathy. Clin Genet. 2011 Oct;80(4):354-66. Epub 2010 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Gerdes AM, Nieman M, Lorenz J, Hewett T, Robbins J. Expression of R120G-alphaB-crystallin causes aberrant desmin and alphaB-crystallin aggregation and cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ Res. 2001 Jul 6;89(1):84-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bova MP, Yaron O, Huang Q, Ding L, Haley DA, Stewart PL, Horwitz J. Mutation R120G in alphaB-crystallin, which is linked to a desmin-related myopathy, results in an irregular structure and defective chaperone-like function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 May 25;96(11):6137-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Arkun K, Rastegar H, Larson AM, Maron MS, Chin MT. Adult Monozygotic Twins With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Identical Disease Expression and Clinical Course. Am J Cardiol. 2020 Jul 15;127:135-138. Epub 2020 Apr 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou C, Martin GL, Perera G, Awata J, Larson A, Blanton R, Chin MT. A novel αB-crystallin R123W variant drives hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by promoting maladaptive calcium-dependent signal transduction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023 Jun 26;10:1223244. Erratum in: Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024 Aug 16;11:1455263. 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1455263. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Somee LR, Barati A, Shahsavani MB, Hoshino M, Hong J, Kumar A, Moosavi-Movahedi AA, Amanlou M, Yousefi R. Understanding the structural and functional changes and biochemical pathomechanism of the cardiomyopathy-associated p.R123W mutation in human αB-crystallin. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2024 Apr;1868(4):130579. Epub 2024 Feb 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A, Potapenko A, Bridgland A, Meyer C, Kohl SAA, Ballard AJ, Cowie A, Romera-Paredes B, Nikolov S, Jain R, Adler J, Back T, Petersen S, Reiman D, Clancy E, Zielinski M, Steinegger M, Pacholska M, Berghammer T, Bodenstein S, Silver D, Vinyals O, Senior AW, Kavukcuoglu K, Kohli P, Hassabis D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021 Aug;596(7873):583-589. Epub 2021 Jul 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Evans R, O’Neill M, Pritzel A, Antropova N, Senior A, Green T, Žídek A, Bates R, Blackwell S, Yim J, Ronneberger O, Bodenstein S, Zielinski M, Bridgland A, Potapenko A, Cowie A, Tunyasuvunakool K, Jain R, Clancy E, Kohli P, Jumper J, Hassabis D. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. bioRxiv. (2021) doi:2021.10.04.463034.

- Varadi M, Bertoni D, Magana P, Paramval U, Pidruchna I, Radhakrishnan M, Tsenkov M, Nair S, Mirdita M, Yeo J, Kovalevskiy O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Laydon A, Žídek A, Tomlinson H, Hariharan D, Abrahamson J, Green T, Jumper J, Birney E, Steinegger M, Hassabis D, Velankar S. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Jan 5;52(D1):D368-D375. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Varadi M, Anyango S, Deshpande M, Nair S, Natassia C, Yordanova G, Yuan D, Stroe O, Wood G, Laydon A, Žídek A, Green T, Tunyasuvunakool K, Petersen S, Jumper J, Clancy E, Green R, Vora A, Lutfi M, Figurnov M, Cowie A, Hobbs N, Kohli P, Kleywegt G, Birney E, Hassabis D, Velankar S. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jan 7;50(D1):D439-D444. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meng EC, Goddard TD, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Pearson ZJ, Morris JH, Ferrin TE. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023 Nov;32(11):e4792. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thorkelsson A, Chin MT. Role of the Alpha-B-Crystallin Protein in Cardiomyopathic Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Feb 29;25(5):2826. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pope RK, Pestonjamasp KN, Smith KP, Wulfkuhle JD, Strassel CP, Lawrence JB, Luna EJ. Cloning, characterization, and chromosomal localization of human superillin (SVIL). Genomics. 1998 Sep 15;52(3):342-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maul RS, Song Y, Amann KJ, Gerbin SC, Pollard TD, Chang DD. EPLIN regulates actin dynamics by cross-linking and stabilizing filaments. J Cell Biol. 2003 Feb 3;160(3):399-407. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Filippakopoulos P, Picaud S, Mangos M, Keates T, Lambert JP, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Felletar I, Volkmer R, Müller S, Pawson T, Gingras AC, Arrowsmith CH, Knapp S. Histone recognition and large-scale structural analysis of the human bromodomain family. Cell. 2012 Mar 30;149(1):214-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oltion K, Carelli JD, Yang T, See SK, Wang HY, Kampmann M, Taunton J. An E3 ligase network engages GCN1 to promote the degradation of translation factors on stalled ribosomes. Cell. 2023 Jan 19;186(2):346-362.e17. Epub 2023 Jan 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li X, Yang L, Chen S, Zheng J, Zhang H, Ren L. Multiple Roles of TRIM21 in Virus Infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 14;24(2):1683. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asher G, Tsvetkov P, Kahana C, Shaul Y. A mechanism of ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation of the tumor suppressors p53 and p73. Genes Dev. 2005 Feb 1;19(3):316-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Burger A, Berendes R, Liemann S, Benz J, Hofmann A, Göttig P, Huber R, Gerke V, Thiel C, Römisch J, Weber K. The crystal structure and ion channel activity of human annexin II, a peripheral membrane protein. J Mol Biol. 1996 Apr 12;257(4):839-47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barefield D, Kumar M, Gorham J, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, de Tombe PP, Sadayappan S. Haploinsufficiency of MYBPC3 exacerbates the development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in heterozygous mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015 Feb;79:234-43. Epub 2014 Nov 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vikstrom KL, Factor SM, Leinwand LA. Mice expressing mutant myosin heavy chains are a model for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mol Med. 1996 Sep;2(5):556-67. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ertz-Berger BR, He H, Dowell C, Factor SM, Haim TE, Nunez S, Schwartz SD, Ingwall JS, Tardiff JC. Changes in the chemical and dynamic properties of cardiac troponin T cause discrete cardiomyopathies in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Dec 13;102(50):18219-24. Epub 2005 Dec 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lowey S, Lesko LM, Rovner AS, Hodges AR, White SL, Low RB, Rincon M, Gulick J, Robbins J. Functional effects of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy R403Q mutation are different in an alpha- or beta-myosin heavy chain backbone. J Biol Chem. 2008 Jul 18;283(29):20579-89. Epub 2008 May 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vakrou S, Fukunaga R, Foster DB, Sorensen L, Liu Y, Guan Y, Woldemichael K, Pineda-Reyes R, Liu T, Tardiff JC, Leinwand LA, Tocchetti CG, Abraham TP, O'Rourke B, Aon MA, Abraham MR. Allele-specific differences in transcriptome, miRNome, and mitochondrial function in two hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mouse models. JCI Insight. 2018 Mar 22;3(6):e94493. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marstrand P, Han L, Day SM, Olivotto I, Ashley EA, Michels M, Pereira AC, Wittekind SG, Helms A, Saberi S, Jacoby D, Ware JS, Colan SD, Semsarian C, Ingles J, Lakdawala NK, Ho CY; SHaRe Investigators. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy With Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction: Insights From the SHaRe Registry. Circulation. 2020 Apr 28;141(17):1371-1383. Epub 2020 Mar 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beltrami M, Bartolini S, Pastore MC, Milli M, Cameli M. Relationship between measures of left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction and clinical and biomarker status in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2022 Nov;115(11):598-609. Epub 2022 Sep 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team (2024). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. <https://www.R-project.org/>.

- Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014 Feb 15;30(4):523-30. Epub 2013 Dec 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrino BA. Regulation of calcineurin phosphatase activity by its autoinhibitory domain. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999 Dec 1;372(1):159-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou C, Chin MT. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy beyond Sarcomere Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Aug 19;22(16):8933. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Golenhofen N, Ness W, Koob R, Htun P, Schaper W, Drenckhahn D. Ischemia-induced phosphorylation and translocation of stress protein alpha B-crystallin to Z lines of myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1998 May;274(5):H1457-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksimiuk M, Sobiborowicz A, Tuzimek A, Deptała A, Czerw A, Badowska-Kozakiewicz AM. αB-crystallin as a promising target in pathological conditions - A review. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2020 Sep 11;27(3):326-334. Epub 2019 Sep 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head MW, Hurwitz L, Kegel K, Goldman JE. AlphaB-crystallin regulates intermediate filament organization in situ. Neuroreport. 2000 Feb 7;11(2):361-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbard JB, Kurnellas MP, Brownell S, Adams CM, Su L, Axtell RC, Chen R, Fathman CG, Robinson WH, Steinman L. Therapeutic effects of systemic administration of chaperone αB-crystallin associated with binding proinflammatory plasma proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012 Mar 23;287(13):9708-9721. Epub 2012 Feb 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu W, Guo Y, Huang Z, Zhao H, Zhou M, Huang Y, Wen D, Song J, Zhu Z, Sun M, Liu CY, Chen Y, Cui L, Wang X, Liu Z, Yang Y, Du P. Small heat shock protein CRYAB inhibits intestinal mucosal inflammatory responses and protects barrier integrity through suppressing IKKβ activity. Mucosal Immunol. 2019 Nov;12(6):1291-1303. Epub 2019 Sep 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arac A, Brownell SE, Rothbard JB, Chen C, Ko RM, Pereira MP, Albers GW, Steinman L, Steinberg GK. Systemic augmentation of alphaB-crystallin provides therapeutic benefit twelve hours post-stroke onset via immune modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Aug 9;108(32):13287-92. Epub 2011 Jul 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Velotta JB, Kimura N, Chang SH, Chung J, Itoh S, Rothbard J, Yang PC, Steinman L, Robbins RC, Fischbein MP. αB-crystallin improves murine cardiac function and attenuates apoptosis in human endothelial cells exposed to ischemia-reperfusion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011 Jun;91(6):1907-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms AS, Alvarado FJ, Yob J, Tang VT, Pagani F, Russell MW, Valdivia HH, Day SM. Genotype-Dependent and -Independent Calcium Signaling Dysregulation in Human Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2016 Nov 29;134(22):1738-1748. Epub 2016 Sep 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coppini R, Ferrantini C, Mugelli A, Poggesi C, Cerbai E. Altered Ca2+ and Na+ Homeostasis in Human Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Implications for Arrhythmogenesis. Front Physiol. 2018 Oct 16;9:1391. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Bueno OF, Parsons SA, Xu J, Plank DM, Jones F, Kimball TR, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin/NFAT coupling participates in pathological, but not physiological, cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2004 Jan 9;94(1):110-8. Epub 2003 Dec 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden RJ, Chen B, Li T, Braun J, Manjunath H, Chen X, Wu J, Schmid V, Chang TC, Kopp F, Ramirez-Martinez A, Tagliabracci VS, Chen ZJ, Xie Y, Mendell JT. An Argonaute phosphorylation cycle promotes microRNA-mediated silencing. Nature. 2017 Feb 9;542(7640):197-202. Epub 2017 Jan 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009 May;6(5):343-5. Epub 2009 Apr 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froger A, Hall JE. Transformation of plasmid DNA into E. coli using the heat shock method. J Vis Exp. 2007;(6):253. doi: 10.3791/253. Epub 2007 Aug 1. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. (1998) 72:8463–71. [CrossRef]

- Richards DA, Aronovitz MJ, Calamaras TD, Tam K, Martin GL, Liu P, Bowditch HK, Zhang P, Huggins GS, Blanton RM. Distinct Phenotypes Induced by Three Degrees of Transverse Aortic Constriction in Mice. Sci Rep. 2019 Apr 10;9(1):5844. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hughes CS, Moggridge S, Müller T, Sorensen PH, Morin GB, Krijgsveld J. Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation for proteomics experiments. Nat Protoc. 2019 Jan;14(1):68-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweppe DK, Prasad S, Belford MW, Navarrete-Perea J, Bailey DJ, Huguet R, Jedrychowski MP, Rad R, McAlister G, Abbatiello SE, Woulters ER, Zabrouskov V, Dunyach JJ, Paulo JA, Gygi SP. Characterization and Optimization of Multiplexed Quantitative Analyses Using High-Field Asymmetric-Waveform Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2019 Mar 19;91(6):4010-4016. Epub 2019 Feb 26. Erratum in: Anal Chem. 2020 Mar 17;92(6):4690. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00888. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007 Mar;4(3):207-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rad R, Li J, Mintseris J, O'Connell J, Gygi SP, Schweppe DK. Improved Monoisotopic Mass Estimation for Deeper Proteome Coverage. J Proteome Res. 2021 Jan 1;20(1):591-598. Epub 2020 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng JK, Jahan TA, Hoopmann MR. Comet: an open-source MS/MS sequence database search tool. Proteomics. 2013 Jan;13(1):22-4. Epub 2012 Dec 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttlin EL, Jedrychowski MP, Elias JE, Goswami T, Rad R, Beausoleil SA, Villén J, Haas W, Sowa ME, Gygi SP. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell. 2010 Dec 23;143(7):1174-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Navarrete-Perea J, Yu Q, Gygi SP, Paulo JA. Streamlined Tandem Mass Tag (SL-TMT) Protocol: An Efficient Strategy for Quantitative (Phospho)proteome Profiling Using Tandem Mass Tag-Synchronous Precursor Selection-MS3. J Proteome Res. 2018 Jun 1;17(6):2226-2236. Epub 2018 May 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li J, Cai Z, Bomgarden RD, Pike I, Kuhn K, Rogers JC, Roberts TM, Gygi SP, Paulo JA. TMTpro-18plex: The Expanded and Complete Set of TMTpro Reagents for Sample Multiplexing. J Proteome Res. 2021 May 7;20(5):2964-2972. Epub 2021 Apr 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schweppe DK, Eng JK, Yu Q, Bailey D, Rad R, Navarrete-Perea J, Huttlin EL, Erickson BK, Paulo JA, Gygi SP. Full-Featured, Real-Time Database Searching Platform Enables Fast and Accurate Multiplexed Quantitative Proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2020 May 1;19(5):2026-2034. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gassaway BM, Li J, Rad R, Mintseris J, Mohler K, Levy T, Aguiar M, Beausoleil SA, Paulo JA, Rinehart J, Huttlin EL, Gygi SP. A multi-purpose, regenerable, proteome-scale, human phosphoserine resource for phosphoproteomics. Nat Methods. 2022 Nov;19(11):1371-1375. Epub 2022 Oct 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sambrano, G. R.; Fraser, I.; Han, H.; Ni, Y.; O'Connell, T.; Yan, Z.; Stull, J. T. , Navigating the signalling network in mouse cardiac myocytes. Nature 2002, 420, (6916), 712–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, F.; Sakata, Y.; Cui, L.; Youngblood, J. M.; Nakagami, H.; Liao, J. K.; Liao, R.; Chin, M. T. , Transcription factor CHF1/Hey2 suppresses cardiac hypertrophy through an inhibitory interaction with GATA4. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006, 290, (5), H1997–H2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Korte, F. S.; Moussavi-Harami, F.; Yu, M.; Razumova, M.; Regnier, M.; Chin, M. T. , Transcription factor CHF1/Hey2 regulates EC coupling and heart failure in mice through regulation of FKBP12. 6. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012, 302, (9), H1860–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connell TD, Rodrigo MC, Simpson PC. Isolation and culture of adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;357:271-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Wickham. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York, 2016.

- Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K, Vaughan D (2023). _dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation_. R package version 1.1.4, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr>.

- Hadley Wickham (2007). Reshaping Data with the reshape Package. Journal of Statistical Software, 21(12), 1-20. URL http://www.jstatsoft.org/v21/i12/.

- Kassambara A (2023). _ggpubr: 'ggplot2' Based Publication Ready Plots_. R package version 0.6.0, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr>.

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, François R, Grolemund G, Hayes A, Henry L, Hester J, Kuhn M, Pedersen TL, Miller E, Bache SM, Müller K, Ooms J, Robinson D, Seidel DP, Spinu V, Takahashi K, Vaughan D, Wilke C, Woo K, Yutani H (2019). “Welcome to the tidyverse.” _Journal of Open Source Software_, *4*(43), 1686. [CrossRef]

- Neuwirth E (2022). _RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer Palettes_. R package version 1.1-3, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RColorBrewer>.

- Slowikowski K (2024). _ggrepel: Automatically Position Non-Overlapping Text Labels with 'ggplot2'_. R package version 0.9.6, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggrepel>.

- Xu S, Hu E, Cai Y, Xie Z, Luo X, Zhan L, Tang W, Wang Q, Liu B, Wang R, Xie W, Wu T, Xie L, Yu G. Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nat Protoc. 2024 Nov;19(11):3292-3320. Epub 2024 Jul 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu G, Wang LG, Yan GR, He QY. DOSE: an R/Bioconductor package for disease ontology semantic and enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015 Feb 15;31(4):608-9. Epub 2014 Oct 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson M (2024). _org.Mm.eg.db: Genome wide annotation for Mouse_. R package version 3.19.1.

- Yu G (2024). _enrichplot: Visualization of Functional Enrichment Result_. R package version 1.24.4, <https://yulab-smu.top/biomedical-knowledge-mining-book/>.

- Ahlmann-Eltze C (2024). _ggupset: Combination Matrix Axis for 'ggplot2' to Create 'UpSet' Plots_. R package version 0.4.0, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggupset>.

- Kolde R (2019). _pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps_. R package version 1.0.12, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap>.

| Enzymes | Kinases | G Protein Coupled Receptors | Phosphatases | Ion Channels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDX3X DHX36 |

EEF2K EGFR |

ADORA2A ADRB1 |

PPP3CA PTP4A1 |

KCNJ2 MCOLN1 |

| FAAH | EIF2AK4 | AGTR2 | SCN1B | |

| HRAS | FLT1 | CX3CR1 | ||

| KRAS | INSR | GPR174 | ||

| POLG | IPMK | MC5R | ||

| MAP2K6 | ||||

| MAP3K12 | ||||

| MAPK14 | ||||

| MKNK1 | ||||

| MOS | ||||

| PRKAG3 | ||||

| PRKCZ | ||||

| PTK2 | ||||

| RAF1 | ||||

| RET | ||||

| ROCK1 | ||||

| ROCK2 TGFBR2 TK1 TTN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).