1. Introduction

Solid cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality and effective treatment of cancer is very challenging. The efficacy of conventional chemotherapy is reduced due to the non-specific distribution, low efficiency, and significant toxicity of many chemo agents in the human body when administered at high doses. [

1,

2,

3] Cancer patients often require chemotherapy after surgical resection of the lesion. Chemotherapy drugs are toxic, and once they enter the human body, they will spread throughout the body, making it difficult to concentrate on the lesion. Therefore, chemotherapy can bring systemic toxicity to patients. [

4,

5,

6] Meanwhile, it is necessary to maintain a higher dosage of chemotherapy drugs for systemic administration in order to achieve the therapeutic concentration at the tumor site, which further enhances the toxicity of drugs to adjacent and remote normal tissues. The concept of drug delivery system (DDS) has hence been popularized. Among them, the magnetic targeted drug delivery system (MTDDS) has attracted high attention due to its safety, high efficiency, and minimal side effects on the human body.[

7,

8,

9] However, most research on magnetic targeted drug delivery systems rely on the strategy to use external magnetic fields to guide magnetic drugs to the lesion.[

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] Although this may be relatively straight forward for the treatment of surface lesions or superficial organs, the technique appears difficult and inconvenient to accurately delivery of MTDDS to the deeper tissues and organs such as bones.

In clinical management of malignant tumors such as osteosarcoma, a common practice is the surgical removal of the primary tumor with adjuvant chemotherapy before and/or after surgery. The research concept of this study is that by implanting a magnetic tissue engineering scaffold into the void space left by the surgical resection, it not only can serve as a tissue reconstruction scaffold, but also become an attraction source to gather/concentrate the chemotherapeutic agent-capsulated magnetic drug delivery particles. Therefore, it is of great significance to construct magnetic tissue engineering scaffolds and study their properties in vitro and in vivo.

Our research laboratory has developed various compositional magnetic engineering scaffolds. In the current study, we prepared ferro ferric oxide (Fe3O4) / polycaprolactone (PCL) magnetic tissue engineering scaffolds and tested their degradation performance in SBF. After in vitro evaluated the cytotoxicity of the scaffolds to the osteoblasts induced by BALB/c mouse bone marrow stem cells, a murine air pouch model was adopted to assess the feasibility of the MTDDS trafficking and tissue responses to the particles in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fe3O4/PCL Scaffolds Preparation

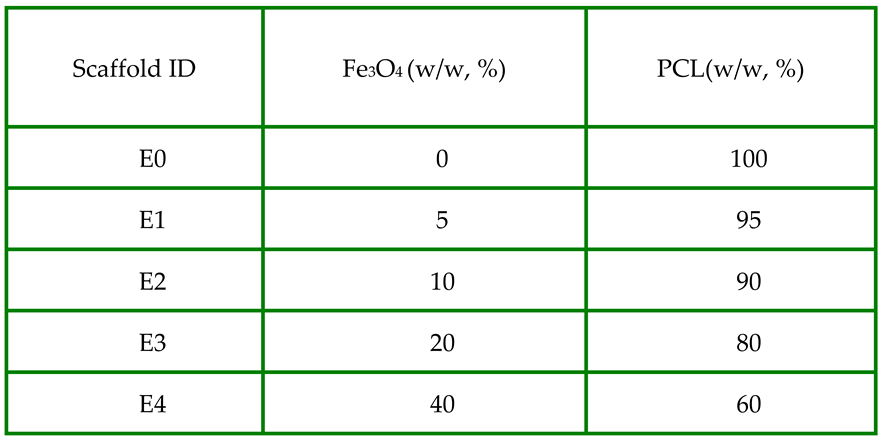

Polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds with iron(II,III) oxide (Fe

3O

4) were prepared using a sodium chloride (NaCl) particulate leaching technique[

16]. In brief, Fe

3O

4 particles (<5μm, 95%, Sigma-Aldrich) and PCL (Mn80,000, Sigma) were mixed at 0:1 (E0), 0.05:0.95 (E1), 0.10:0.90 (E2), 0.20:0.80 (E3) and 0.40:0.60 (E4) wt/wt ratios (

Table1).

NaCl particles sized in 355–500 um at 9 folds of the total weight of Fe3O4 and PCL were used to generate a controlled porosity in the scaffold. PCL was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (Sigma-Aldrich, US) followed by homogeneously mixed in Fe3O4 particles and NaCl particles until a viscous slurry developed. The mixture was cast into a mold. After evaporation of the solvent, the samples were taken out of the mold, and washed in excess distilled water to leach out NaCl. The ultrastructures of scaffolds were observed using a scanning electronic microscope SEM (FE-SEM SU-70).

2.2. Degradability of Scaffolds in Simulated Body Fluid

The simulated body fluid (SBF) used in this research was prepared according to the literature [

17] and have a pH value of 7.4. Its components are similar to human plasma. Scaffold dices (10 mm x10 mm x 2.5 mm) were incubated in 5 ml SBF in test tubes which were agitated at 37 °C at a rate of 160 rpm. SBF solution was changed weekly.

The dry weight of scaffolds was measured before immersed in SBF (designated as “Wi”). After incubation in SBF for one week, scaffolds were taken out and washed with ddH2O thoroughly. After being dried out, their weight was measured again (designated as “Ws”). The percentage of mass loss was recorded as mass loss (%) = (Wi − Ws) / Wi × 100%. If Wi < Ws, the calculation formula would be changed to (Ws-Wi)/Wi x 100% as the increase weight ratio of the scaffolds showing in the figure. pH value change of SBF and weight change of scaffolds were continually recorded for 4 weeks.

2.3. Mouse Cells Culture

Primary bone marrow-derived stromal cells (BMSCs) were isolated from Balb/C mice of 6 - 8 weeks of age and were induced to differentiate to osteoblasts in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, US), 10 mM β-glycerolphosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, US), 100 mM L-ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, US), and 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, US), 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen, US), 100 U/ml penicillin (Invitrogen, US), and 0.1mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, US)[

18]. Medium was changed every third day until use for scaffold cytotoxicity experiments.

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay of Fe3O4/PCL Scaffolds

Each sample (square,10mm x 10mm x 2.5mm) was immersed in 1ml culture medium in a sterile tube for 24 hours at 37oC before harvesting the supernatant for Day1 release. The same amount (1ml) of fresh medium was added to the tube, and then the medium was harvested after 24h at 37 oC and labeled Day 2. The above procedure was repeated every day till Day7 release media were yielded.

Primary mouse osteoblasts were seeded in a 96-well plate at 10

4 /100μl medium/well for 24h in an incubator (37

oC, 5%CO

2 in air) before introduction of the samples release media (100μl medium/well) including control wells with fresh medium. AlamarBlue® reagent (ThermoFisher) at 1 to 10 ratio were added to the culture medium. Absorbance detection of the culture media 6 hours later, on a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, SPECTRA max, PLUS) after transferred to a new reading plate [

19]. Cells were continued to culture in a fresh medium and repeated the next day for a total of 7 days. The cell proliferation/cytotoxicity ratios among groups were calculated based on the absorbance readings of alamarBlue® at 570 nm normalized the 600 nm value.

2.5. Animal Experiment

Twenty Balb/C mice of ~20 gm body weight were recruited to establish the air pouch model as previously described[

20]. Briefly, 3 ml of filtered air was subcutaneously injected on the back of the mice, with a repeated 1 ml of air injection 3 days later. At day 7 when the air pouches were established, scaffold dices (8mmX8mmX1mm) of E0 and E3 were surgically implanted into the pouches. At the following day, 0.5 ml fluorescence-magnetic suspensoid was peritoneally injected into each mouse. The mice were sacrificed 5 days later, the pouches were collected for histological and molecular assessments.

The fluorescence-magnetic suspensoid were fabricated by mixing 14 mg of Fe3O4 particles (<50nm, Sigma-Aldrich) with 4 mg 1,6-Diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH, 98%, Aldrich) in 10ml of sterile PBS.

2.6. Histological Assessment

Cryosections of implanted scaffolds at 10μm thickness were processed at the Pathology Core in Via Christi St. Francis Hospital and stored in -20°C till used. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed, and the images of stained sections were digitally captured under a Nikon Eclipse fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY USA). The fluorescence images of the frozen sections of the pouches and organ tissues were digitally captured under a dark-field fluorescence Microscope (Axio Imager A2, Zeiss).

2.7. Real-Time PCR

The expression of inflammatory cytokines in the air pouch tissues around the implant scaffolds were quantified by a real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technique with the standardized protocol previously described[

21,

22]. In brief, mouse pouch tissues were homogenized using a polytron Homogenizer (Brinkman Instrument), and total RNAs from the homogenates were isolated by TRIzol

TM (Invitrogen) / chloroform. Reverse transcription and real-time PCR were performed in the StepOne Plus, Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), with murine IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 primer pairs. The fluorescent signals were recorded dynamically. Normalization and analysis of the reporter signals (∆Rn) at the threshold cycle was carried out, and the relative target gene quantitation among samples were calculated using the software provided by the manufacturer[

23].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

In vitro experimental data from 3 individual experiments were combined for statistical analysis. Sample size of the animal experiment was estimated using a PSTM program (Power and Sample Size Calculations, version 3.1.2). Student T-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with LSD post hoc multiple sample comparisons were performed among groups (IBM SPSS, version 22). Data were expressed as Mean and standard error of mean (SEM), and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Scaffold Morphology Under Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

SEM images confirmed the uniform open-porous structures on the surface of the scaffolds with various concentrations of Fe

3O

4 (

Figure 1), which is essential for cell adhesion and proliferation. According to our previous work [

24], an increase of Fe

3O

4 ratio in the scaffolds enhanced the magnetism, but diminished the structural stability of the scaffolds. When the percentage of Fe

3O

4 was higher than 40%, the scaffolds would be difficult to fabricate, or they became very fragile. For the current study, five different weight ratios Fe

3O

4/PCL scaffolds were tested with Fe

3O

4 powders of 0, 5, 10, 20 and 40%, respectively. Although all the scaffolds formed an even open-porous structure, the higher magnification power of SEM examination revealed uniformly embedded Fe

3O

4 particles in the matrix of PCL on the 5% and 10% concentrated samples (

Figure 2B,C), in that the Fe

3O

4 granules were separated from each other. Conversely, the two higher concentrated specimens appeared packed with Fe

3O

4 particles (

Figure 2D,E).

3.2. Degradability of Scaffolds in SBF

To test the stability of the Fe

3O

4 embedded scaffolds, they were immersed in SBF with physiological pH at 37 °C for a period of time.

Figure 2 illustrated the morphological appearance of the samples prior to and after SBF immersion for 2 weeks. Some sediments appeared on the original smooth surface of the pure PCL scaffolds after immersion in SBF (

Figure 2A1); and the morphological changes were also noticeable on other groups of scaffolds: the original Fe

3O

4 particles became smooth but at the same time the new sediments formed under the SEM. Further, dry weight measurements of the scaffolds prior to and after SBF immersion were performed among groups. All the samples gained mass weight following immersion in the simulated body fluid and the scaffold mass addition was correlated with the immersion time (

Figure 3A).

3.3. Biocompatibility of the Scaffolds

To test the biocompatibility of the scaffolds, daily elution SBF of the scaffolds was added to the primary mouse osteoblast cultures. The alamarBlue® proliferation assay suggested comparable cell proliferation patterns among all groups over the experimental period, suggesting that the components released from the scaffolds were not likely to cytotoxic or inhibit cell growth (

Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

High magnification of SEM images revealing the morphological changes of the scaffolds with various concentration of the magnetic particles. Left column: prior to immersion in SBF; and right column: immersion for 2 weeks.

Figure 2.

High magnification of SEM images revealing the morphological changes of the scaffolds with various concentration of the magnetic particles. Left column: prior to immersion in SBF; and right column: immersion for 2 weeks.

Figure 3.

Plot A quantifies the mass changes of the scaffolds following immersion in SBF over periods of time (*p < 0.05 compared to #); while B summarizes cell growth patterns with co-culturing of elution from various groups of scaffolds by an alamarBlue® proliferation assay.

Figure 3.

Plot A quantifies the mass changes of the scaffolds following immersion in SBF over periods of time (*p < 0.05 compared to #); while B summarizes cell growth patterns with co-culturing of elution from various groups of scaffolds by an alamarBlue® proliferation assay.

3.4. Murine Air Pouch Model for Targeted Drug Delivery

To ensure the effective magnetic attraction for potential drug delivery, the trafficking of the fluorescent magnetic particles was examined using the mouse air pouch model [

20]. Following peritoneal injection of fluorescent particles, extensive fluorescent signals were accumulated in the pouches with Fe

3O

4/PCL scaffolds, while no fluorescence appeared on pouches bearing PCL alone scaffolds (

Figure 4A,B). It is apparent that magnetic composite scaffolds have great potential to attract/home magnetic drug delivery substances. Histological assessment of the pouch tissues bearing Fe

3O

4/PCL scaffolds illustrated benign tissue response to the embedded materials, no significant inflammatory cell infiltrations (

Figure 4C,D) and inflamed pouch tissues compared to the scaffold-free control group (

Figure 4E). Real-time PCR analysis did not reveal significant elevation of IL-1α, IL-6, and TNFβ expressions among the groups (

Figure 4F).

4. Discussion

MTDDS has attracted widespread attention for its ability to gather chemotherapy drugs at the affected area through magnetic field guidance, thereby reducing the chemo-agents’ systemic side effects. Studies have shown that external magnetic fields may guide magnetic chemotherapy drugs to the affected area for targeted drug delivery [

25]. The use of external magnetic fields increases the difficulty of drug administration in clinical practice and may not be sufficient to accurately dispatch drugs to certain targeted areas. We have been investigating an implantable magnetic tissue engineering scaffold to serve as a tissue void filler following surgical tumor resection and an internal driving force for drug enrichment towards the affected area. Previously

in vitro studies from our laboratories have suggested Fe

3O

4 /poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) and Fe

3O

4/chitosan biocomposites possessed good biocompatibility with high magnetism [

16,

26]. Mixing various sized magnet particles with polycaprolactone (PCL) were also examined to screen magnetic composites for their mechanical properties and cell biocompatibility [

19]. The current study further evaluated the Fe

3O

4/PCL scaffold mass changes during the extended immersion in a simulated body fluid. More importantly, this investigation evaluated the

in vivo biocompatibility and internal magnetic particles’ trafficking in response to virously concentrated Fe

3O

4 granules in PCL composites using a murine model.

Scaffolds used in tissue engineering should remain stable before the implanted cells produce their own extracellular matrix [

27], prior to their degradation. There was an interesting finding that the mass weight of Fe

3O

4/PCL scaffolds increased during immersion in SBF for 2 weeks or more. Material sediments were deposited on the scaffolds, and the dry weights were increased in an immersion time-dependent fashion. These new sediments appear to be hydroxyapatite as we reported previously [

26]. It is apparent that the deposition rate of sediments to the scaffolds was higher than the degradation rate of the scaffolds. The cell proliferation assay also indicated that the biocomposite scaffolds were stable and no cytotoxic elution was generated during the testing period. The pH values of the SBF elution samples, up to 4 weeks, did not show significant variations (data not shown).

For the animal experimentation, established air pouches were surgically implanted either pure PCL scaffold (E0) or magnetic scaffolds containing 20% Fe3O4 (E3). Fluorescent-labeled magnetic particles were then peritoneal injected into all the groups of mice. It is amazingly observed that significantly enhanced fluorescent signals were attracted back into the air pouches containing Fe3O4/PCL biocomposite, indicating the successful particle homing. Histological and molecular assessment complementarily confirmed the benign tissue response to the scaffolds.

5. Conclusions

This report suggests that inclusion of certain concentrations of micron-sized Fe3O4 in PCL can be fabricated into porous biocomposite scaffolds that are biocompatible, sustainable, and potentially sufficient to attract MTDDS for targeted delivery. Further investigations are warranted to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of the magnetic engineering scaffolds and potential long-term safety issues using animal models of experimental tumors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.Y. and J.G.; methodology, J.G. and R.D.; validation, S.Y.Y., and A.W.; formal analysis, S.Y.; investigation, J.G.; resources, S.Y.Y.; data curation, J.G., and B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.Y.; visualization, R.D.; supervision, S.Y.Y.; project administration, J.G.; funding acquisition, S.Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Wichita Medical Research & Education Foundation, and Level 1 Dean’s Fund, University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) of Wichita State University.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the research data can be shared by requesting to the first and corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the excellent technical support of Dr. Ling Bai and Ms. Zheng Song.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The grant funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCL |

polycaprolactone |

| MTDDS |

Magnetic Targeted Drug Delivery System |

| SBF |

simulated body fluid |

| H&E |

Hematoxylin and eosin staining |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Jensen C, Madsen DH, Hansen M, Schmidt H, Svane IM, Karsdal MA, et al. Non-invasive biomarkers derived from the extracellular matrix associate with response to immune checkpoint blockade (anti-CTLA-4) in metastatic melanoma patients. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6(1):152. [CrossRef]

- Paolini L, Poli C, Blanchard S, Urban T, Croue A, Rousselet MC, et al. Thoracic and cutaneous sarcoid-like reaction associated with anti-PD-1 therapy: longitudinal monitoring of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression after stopping treatment. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6(1):52. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Fan L, Xu H, Qin Z, Zhu Z, Wu D, et al. HSP90AA1 is an unfavorable prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma and contributes to tumorigenesis and chemotherapy resistance. Transl Oncol 2024;50:102148. [CrossRef]

- Bi H, Han X. Magnetic field triggered drug release from lipid microcapsule containing lipid-coated magnetic nanoparticles. Chemical Physics Letters 2018;706:455-60. [CrossRef]

- Cai X, Yu X, Qin W, Wang T, Jia Z, Xiao R, et al. Preparation and anti-Raji lymphoma efficacy of a novel pH sensitive and magnetic targeting nanoparticles drug delivery system. Bioorg Chem 2020;94:103375. [CrossRef]

- Ceylan M, Misak HE, Strong N, Yang S-Y, Asmatulu R. Reduced toxicity of protein/magnetic targeted drug delivery system for improved skin cancer treatment in mice model. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2021;539:168404. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Bi H-Y, Li H, Mao X-M, Liang Y-Q. Synthesis, characterization, and sustained release property of Fe3O4@(enrofloxacin-layered double hydroxides) nanocomposite. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017;78:886-91. [CrossRef]

- Mahdieh A, Yeganeh H, Motasadizadeh H, Nekoueifard E, Maghsoudian S, Hossein Ghahremani M, et al. Waterborne polyurethane magnetic nanomicelles with magnetically governed functions for breast cancer therapy. Int J Pharm 2023;645:123356. [CrossRef]

- Sattarahmady N, Azarpira N, Hosseinpour A, Heli H, Zare T. Albumin coated arginine-capped magnetite nanoparticles as a paclitaxel vehicle: Physicochemical characterizations and in vitro evaluation. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2016;36:68-74. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Wang Y, Zhang L, Xu M, Zhang J, Dong W. Magnetic field-driven drug release from modified iron oxide-integrated polysaccharide hydrogel. International journal of biological macromolecules 2018;108:558-67. [CrossRef]

- Dai Z, Wen W, Guo Z, Song X-Z, Zheng K, Xu X, et al. SiO2-coated magnetic nano-Fe3O4 photosensitizer for synergistic tumour-targeted chemo-photothermal therapy. Colloids and surfaces B: biointerfaces 2020;195:111274. [CrossRef]

- Gonbadi P, Jalal R, Akhlaghinia B, Ghasemzadeh MS. Tannic acid-modified magnetic hydrotalcite-based MgAl nanoparticles for the in vitro targeted delivery of doxorubicin to the estrogen receptor-overexpressing colorectal cancer cells. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2022;68:103026. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Tan Z, Zheng D, Qiu X. pH-responsive magnetic Fe3O4/carboxymethyl chitosan/aminated lignosulfonate nanoparticles with uniform size for targeted drug loading. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023;225:1182-92. [CrossRef]

- Maheswari PU, Muthappa R, Bindhya KP, Begum KMS. Evaluation of folic acid functionalized BSA-CaFe2O4 nanohybrid carrier for the controlled delivery of natural cytotoxic drugs hesperidin and eugenol. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021;61:102105. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Zhu L, Li Y, Wang H, Xu S, Zhang X, et al. Superparamagnetic chitosan nanocomplexes for colorectal tumor-targeted delivery of irinotecan. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2020;584:119394. [CrossRef]

- Ge J, Zhang Y, Dong Z, Jia J, Zhu J, Miao X, et al. Initiation of targeted nanodrug delivery in vivo by a multifunctional magnetic implant. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2017;9(24):20771-8. [CrossRef]

- Cho S, Miyaji F, Kokubo T, Nakanishi K, Soga N, Nakamura T. Apatite formation on silica gel in simulated body fluid: effects of structural modification with solvent-exchange. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 1998;9:279-84. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Wooley PH, Yang S-Y. Biocompatibility of Poly-ε-caprolactone-hydroxyapatite composite on mouse bone marrow-derived osteoblasts and endothelial cells. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2009;4:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ge J, Asmatulu R, Zhu B, Zhang Q, Yang SY. Synthesis and Properties of Magnetic Fe(3)O(4)/PCL Porous Biocomposite Scaffolds with Different Sizes and Quantities of Fe(3)O(4) Particles. Bioengineering (Basel) 2022;9(7). [CrossRef]

- Wooley PH, Morren R, Andary J, Sud S, Yang SY, Mayton L, et al. Inflammatory responses to orthopaedic biomaterials in the murine air pouch. Biomaterials 2002;23(2):517-26. [CrossRef]

- Yang SY, Wu B, Mayton L, Mukherjee P, Robbins PD, Evans CH, et al. Protective effects of IL-1Ra or vIL-10 gene transfer on a murine model of wear debris-induced osteolysis. Gene Ther 2004;11(5):483-91. [CrossRef]

- Jiang J, Jia T, Gong W, Ning B, Wooley PH, Yang SY. Macrophage Polarization in IL-10 Treatment of Particle-Induced Inflammation and Osteolysis. Am J Pathol 2016;186(1):57-66. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001;25(4):402-8. [CrossRef]

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [19, 24].

- Yang X, Kubican SE, Yi Z, Tong S. Advances in magnetic nanoparticles for molecular medicine. Chem Commun (Camb) 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ge J, Zhai M, Zhang Y, Bian J, Wu J. Biocompatible Fe(3)O(4)/chitosan scaffolds with high magnetism. Int J Biol Macromol 2019;128:406-13. [CrossRef]

- Sung HJ, Meredith C, Johnson C, Galis ZS. The effect of scaffold degradation rate on three-dimensional cell growth and angiogenesis. Biomaterials 2004;25(26):5735-42. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).