1. Introduction

The Circular Economy (CE) approach can be an effective response to the challenges of economic growth accompanied by an increase in production and waste.

The poultry industry has witnessed a huge increase in the scale of production with the generation of a large amount of poultry by-products over the years [

1]. Due to this, the disposal of poultry feathers is difficult and cost-effective, these millions of tons of feather waste ultimately end up in the environment, creating a serious solid waste problem [

2]. To date, a negligible amount of this waste has been used industrially for clothing, insulation, production of biodegradable polymers and microbiological culture media. To minimize their environmental hazard, it is necessary to manage them in an environmentally friendly and cost-effective manner [

3]. Chicken feathers contain 90% keratin, 1% lipids and 8% water, and keratin protein is naturally insoluble due to the presence of peptide bonds [

4]. It can also be a good source of organic matter that can help maintain soil fertility and improve productivity. Therefore, chicken feathers are considered as a potential source for the production of nonwoven geotextiles due to their light weight, low cost, high availability and durability. It has been found that some important soil parameters such as bulk density, porosity, water capacity, which are crucial for maintaining soil quality and protection, are changed by the use of geotextile. Some researchers have suggested that the use of natural geotextile increases the nutrient content in the soil [

5].

Geotextiles appears durable and soft and they are designed in a way that allows the flow of liquids through it [

6]. Geotextile can be produced from both biodegradable and non-biodegradable materials. Natural fibres are best suited for geotextile production as they possess properties like high strength, high moisture intake and low elasticity [

7]. Natural geotextiles, after being incorporated into the soil, improve soil structure and soil microbial activity [

8]. During the biodegradation process, they provide organic material and nutrients to the plants and microorganisms which creates an optimum condition for the plant growth. Natural geotextiles have many applications such as crop protection, erosion control, reinforcement systems on embankments, and so on.

An additional advantage of biodegradable nonwoven fabrics is that after the period of use they do not need to be collected from the soil surface, and the products resulting from their decomposition are valuable nutrients for plants.

Polymers’ degradation consists of biodeterioration, biofragmentation and assimilation. The first step is based on the growth of microorganisms on the surface, which influence mechanical, chemical and physical properties [

9,

10]. The second step is based on cutting polymer to oligomers and monomers which leads to obtained dissolved form. The most important process is assimilation which results in production of CO

2, energy and biomass under aerobic conditions and CO

2 and CH

4 under anaerobic conditions [

11].

The experiment assessed the biodegradability of nonwoven fabrics in laboratory conditions and the change in the structure of nonwoven fabrics depending on the composition and degree of feather fragmentation that composite nonwoven fabrics undergo during the biodegradation process.

2. Materials and Methods

MATERIALS:

The test material was nonwovens manufactured by the needle-punching method at the Łukasiewicz Research Network—Łódź Institute of Technology. Four types of nonwovens were selected for testing:

- 100% PLA—PLA_0.1, PLA_0.2—differing in basis weight,

- 50% PLA/50% cotton—PLA.C_01, PLA.C_0.2—differing in basis weight,

- PLA with feathers added—PLA_1—PLA_4—differing in feather content and basis weight,

- PLA/cotton (1:1) with feather addition—PLA.C_1—PLA.C_5—differing in feather content and basis weight.

The following raw materials were used to manufacture the nonwovens:

- shredded chicken feathers (producer: CEDROB S.A. Z.D. Niepołomice),

- PLA (producer: Trevira GmbH, Werk Bobingen QS Stapelfasern) TREVIRA® 400 1,7 dtex bright rd 38 mm,

- cotton (waste from the production of cosmetic pads).

METHODS:

Biodegradability was assessed according to an accredited and validated method carried out on a laboratory scale. The tests were conducted for samples manufactured on a quarter-technical scale. Each 5 x 5 cm sample was tested in triplicate under the conditions of repeatability and reproducibility. For the final result, which was the arithmetic mean of three repetitions, the measurement uncertainty components were determined. The reference material was Cotton 100%. According to the available standards, biodegradable material should achieve 90% of decomposition within a maximum period of 24 weeks.

Due to the potential use of the materials, the research medium for biodegradation studies was soil. The tests were carried out at a temperature of 30± 2°C and humidity of 60-75%. For the tests unfertilized universal soil with a total number of microorganisms of not less than 106 cfu was used. Samples were placed in research reactors filled with the test soil and stored in a heat chamber which enabled the control and maintenance of the set environmental parameters (temperature, humidity). The decomposition process was observed for a maximum of 6 months and the soil moisture was checked daily. The process was carries out in aerobic conditions.

The ecotoxicity tests were conducted. Ecotoxicity tests were aimed at determining the impact of microbiological degradation of test samples on the total number of microorganisms in the test matrix. The tests were performed in accordance with the accredited and validated research procedure “Assessment of the influence of natural and synthetic materials on soil microflora”, developed on the basis on international standards (EN ISO 7218:2008; EN ISO 11133 and EN ISO 11133:2014-07/A1; EN ISO 4833-1:2013-12, and EN ISO 19036:2020-04). The sampling periods for the studies were correlated with intermediate checks of the progress of the biodegradation process.

Due to the complexity and heterogeneity of the nonwovens, it is not possible to describe in detail the reaction stoichiometry. The research included the determination of the carbon to nitrogen ratio in the test medium during the biodegradation process. In soil organic matter this ratio should be relatively constant.

Data were statistically evaluated using statistical analysis package (StatSoft, Po-land STATISTICA, version 9.0.). Correlation and cluster analysis were performed.

3. Results

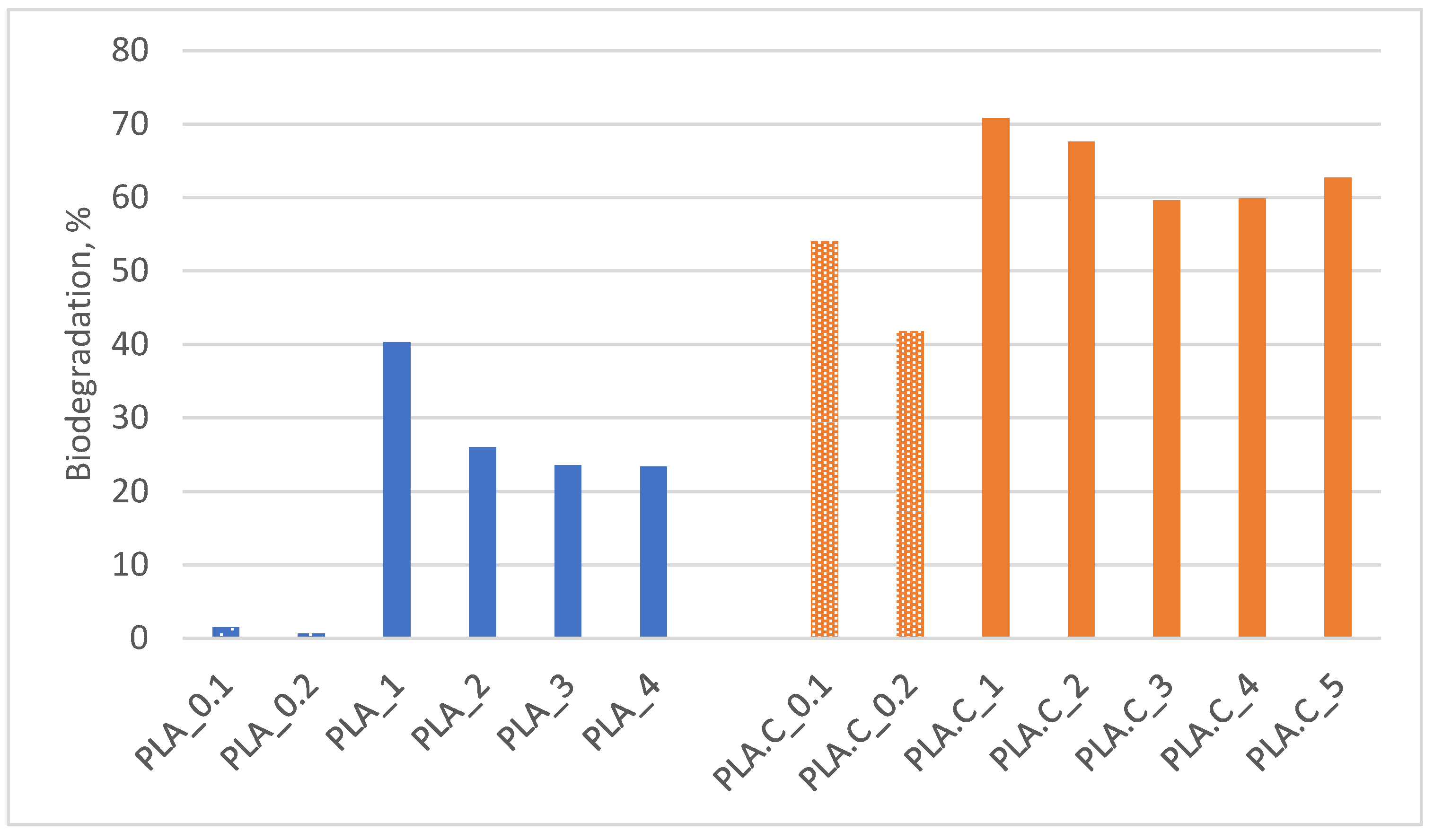

Needle-punched nonwovens made from PLA, cotton and shredded feathers were biodegraded under soil conditions. The degree of biodegradation (mass loss) was calculated in the tested groups of nonwovens. The degree of biodegradation of materials differed in the tested groups and resulted directly from the composition of nonwoven fabrics. The

Table 1 is a summary of the obtained results of the degradation degree together with the composition of the tested samples.

The obtained results were presented in

Figure 1 and divided into groups based on composition. Observations show that the degree of biodegradation of the tested materials is similar in percentage to the content of cotton and/or feathers. For samples consisting of 100% PLA the degree of decomposition was negligible.

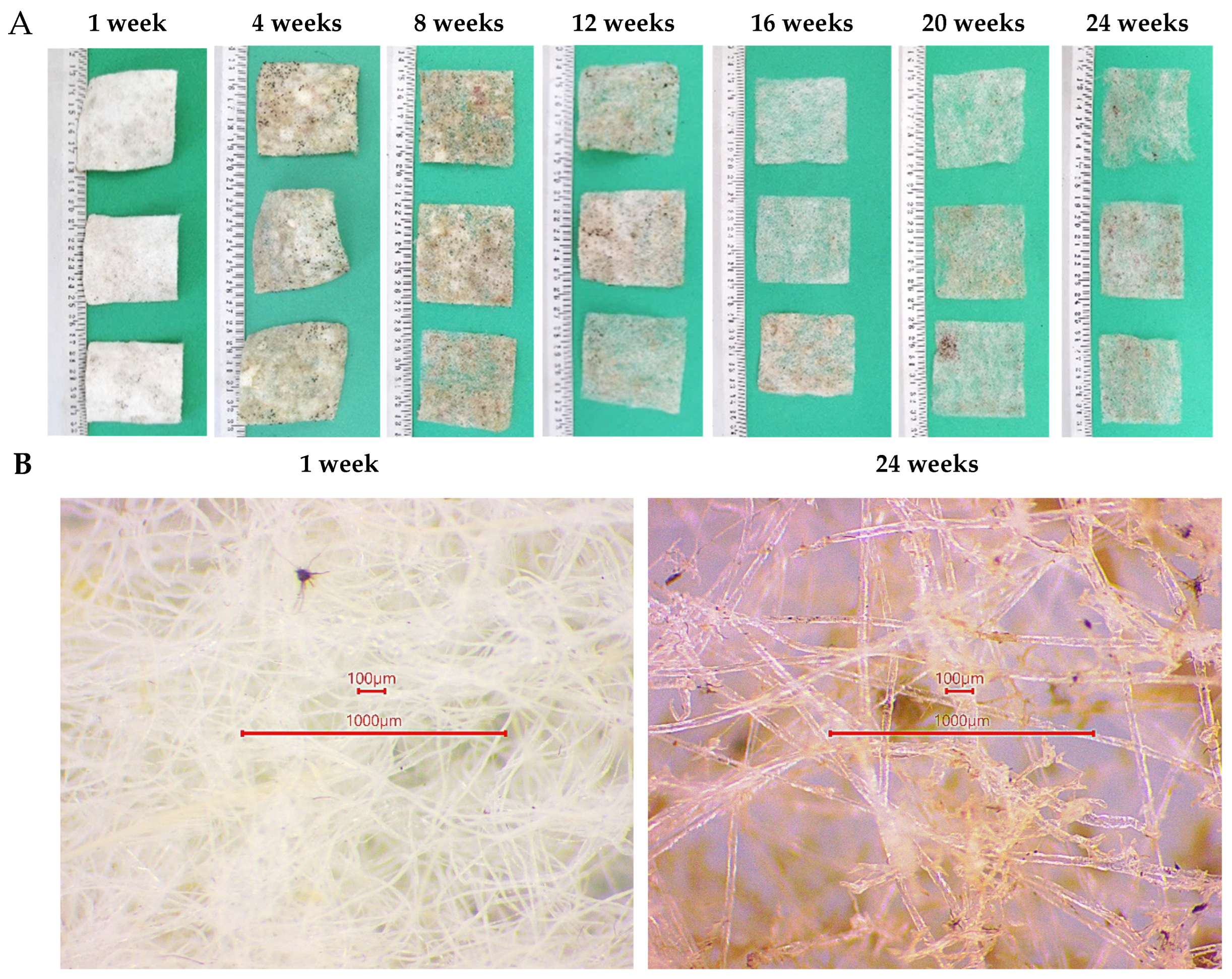

For the sample with the highest degree of biodegradation—PLA.C_1,

Figure 2 shows the progress of biodegradation over time. Changes in the structure of the PLA.C_1 nonwoven can also be observed in the images shown in

Figure 3—both macroscopic images (A) and under the optical microscope (B).

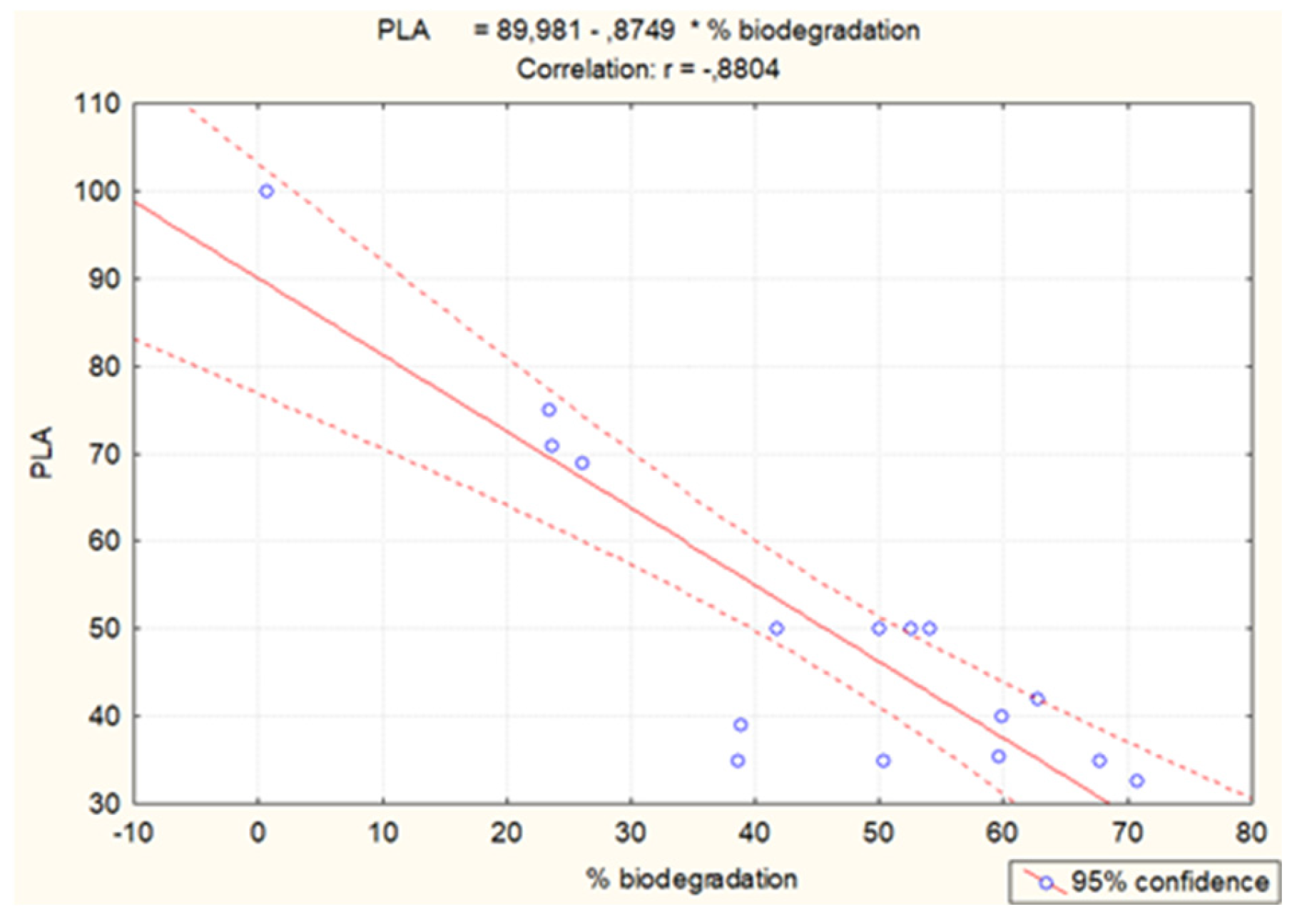

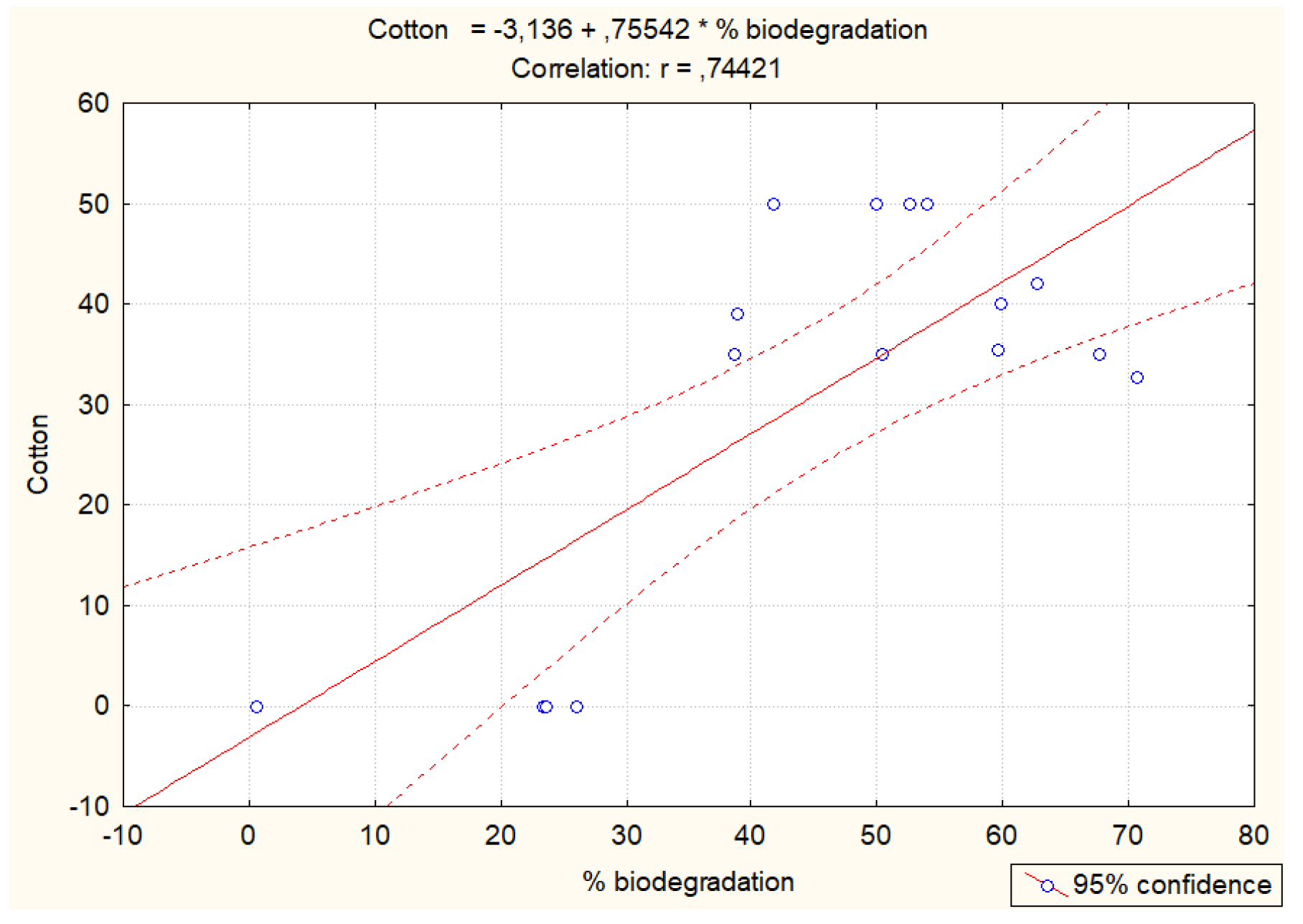

Correlations between selected properties: PLA content (-0.88), cotton content (0.74), feather content (0.17), grammage (-0.38), feather fragmentation degree (0.19) and biodegradation degree were examined. A strong correlation was shown for PLA content (reverse correlation) and cotton (positive correlation).

Figure 4 and 5 present the described dependencies. The obtained results show that the higher the PLA content, the lower the degree of decomposition, and the more cotton, the higher the degree of decomposition.

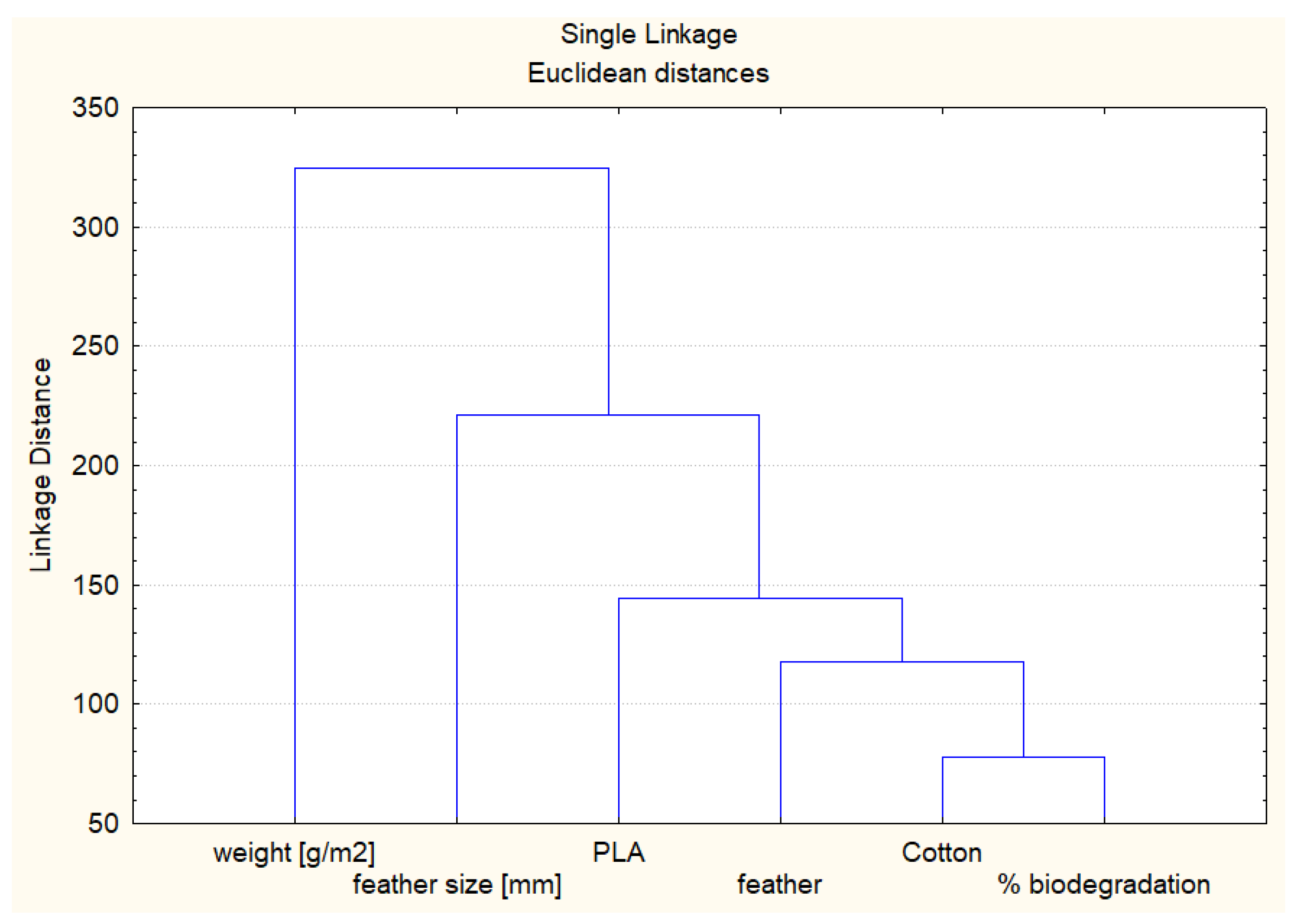

In order to illustrate the relationship between the examined features, the cluster analysis was performed (

Figure 6). The test organizes items (features) into groups, or clusters, on the basis of how closely associated they are.

Cluster analysis confirmed a strong correlation between the degree of biodegradation and cotton content. The analysis also showed a correlation between this group and feather content.

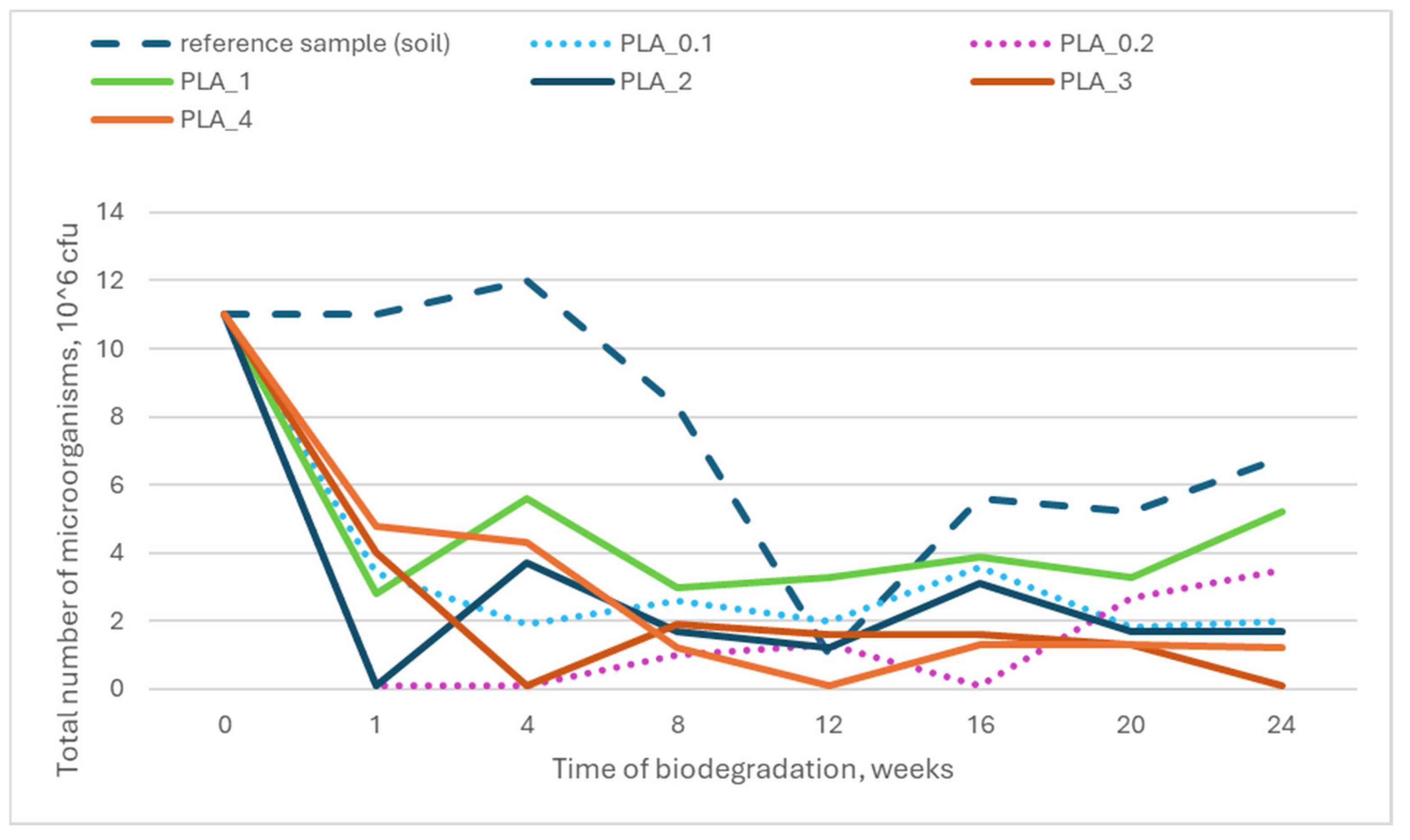

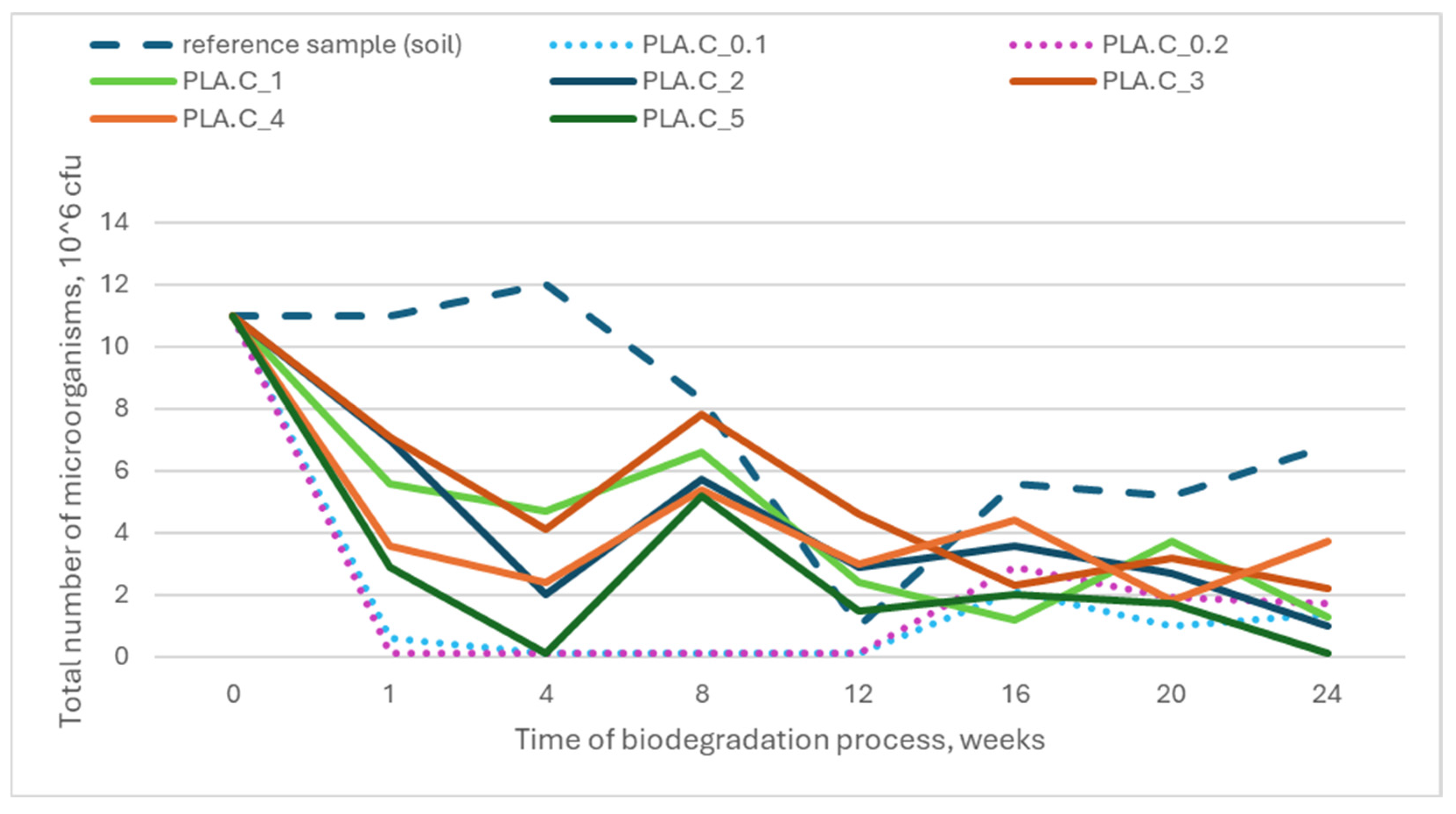

Knowing that biodegradation is a natural process occurring with the participation of microorganisms, ecotoxicity tests were performed. The test consisted of determining the effect of material decomposition on the total number of microorganisms in the soil (responsible for sample decomposition). The results showed no significant deviations from the reference sample (soil without contact with the research samples).

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the total number of microorganisms in the individual research reactors during the process.

4. Discussion

The application of PLA in various purposes is widely reported due to the advantages of the material, such as easy processability, low toxicity, and high transparency. Yet, one of the greatest disadvantages is the low rate of biodegradation in mesophilic and psychrophilic environments [

12]. Cotton fibers are one of the most widely used. The material is naturally biodegradable, however chemical modification can influence the rate of decomposition. The process is based on depolymerization of the cellulose macromolecules [

13]. Our previous studies showed that nonwovens made with the addition of feathers can have a great potential in management of hazardous waste with simultaneous enriching the natural environment [

14].

Our research was aimed at determining the degree of decomposition in soil environment of nonwoven fabrics consisting of 100% PLA or 50% PLA and 50% Cotton and the same nonwoven fabrics with the addition of poultry feathers, and thus at determining the effect of the addition of feathers on the decomposition process.

The presented study showed that nonwovens composed of 100% PLA reached 1.5 % of degradation after 24 weeks of biodegradation process in soil. The obtained results are consistent with data published by other researchers for the PLA. Slezak and al. [

9] performed studies of biodegradation of polylactide (PLA) with polybutylene adipate terephthalate and additives, and PLA-based polyester blend with mineral filler in soil environment. The average temperature was 9.4 °C. After one year the decomposition degree for samples was below 0.6%. authors indicated surface erosion of samples and decrease in tensile strength. Rudnik et al. [

15] conducted long- term studies of decomposition of PLA fibers in soil and reported slow progress of the process. Other studies revealed low or no hydrolysis or biodegradation of PLA in the environment [

16]. The literature [

17] reports that the estimated period of biodegradation of PLA in soil is about 43 years.

Many factors influence the degradation rate of PLA, such as the isomer ratio, temperature, pH, burial time, humidity, oxygen, and the shape and size of the material. PLA is reported to decompose under several possible mechanisms: hydrolytic, oxidative, thermal, microbiological, enzymatic, chemical and photodegradable, which mainly cause cracks in the main and side chains. The greatest interest is focused on enzymatic and microbiological mechanisms, which leads to the decomposition of PLA to CO

2 and H

2O [

18,

19,

20]. Due to the fact that temperature, pH and thermal conditions as well as structure of microorganisms differs in soil and compost the pace of the process is different in these environments [

21,

22].

The biodegradation of PLA in soil depends mainly on the presence of water and temperature. The first step of the process is hydrolytic degradation. Water penetrates into the structure of PLA and breaks the ester bonds and creates oligo- and monomeric structures. The water-soluble oligomers then diffuse into the surrounding environment. Surface erosion occurs when the rate of oligomer release is greater than the rate of water diffusion into the sample. Otherwise, erosion is observed throughout the entire volume of the material. The second stage is connected with microorganisms’ activity and is based on decomposition of water-soluble units and oligomers to simpler compounds, and finally to CO

2 and H

2O. The speed of PLA degradation is strictly dependent on environmental conditions. The higher the temperature and the higher the humidity, the faster the process [

21,

23]. Other factors that have impact on biodegradation of PLA are its size and shape [

24]. Krawczyk-Walach et al. analyzed and described in detail the process of PLA biodegradation in soil [

25].

Nonwovens composed of 50% PLA and 50% Cotton reached about 50% of biological degradation after 24 weeks. The rate of mass loss is almost equal to the amount of Cotton. The obtained results lead to the conclusion that combination of Cotton and PLA does not influence degradability of the latter. The correlation analysis confirmed significant influence of PLA (-0.88) and Cotton (0.74) amount on biodegradation rate (the higher amount of PLA the lower biodegradation degree and the higher amount of Cotton the higher biodegradation degree). Simultaneously, no significant effect of basis weight on biodegradation was shown. Similar conclusions can be drawn based on the interpretation of cluster analysis. The highest degree of biodegradation was recorded for samples consisting of PLA, cotton and feathers.

For nonwoven fabrics with the addition of feathers, the degree of biodegradation after 24 weeks was almost equal to the feather content (PLA_1-PLA_4) or the combined content of cotton and feathers (PLA.C_1-PLA.C_5). Analysis of the progress of biodegradation over time indicates that the process proceeds almost linearly in the initial stage, and after reaching the levels mentioned above, it slows down significantly. However, the sample remaining after this time still retains the nonwoven fabric structure, although it differs in basis weight from the initial sample. Microscopic analysis clearly shows a loosening of structure and an almost intact structure of the PLA fibers.

Biodegradable or partially biodegradable geotextiles can be used for soil reinforcement, particularly in applications where temporary stabilization or support is required during the establishment of vegetation or the initial stabilization phase of a project. Such materials can improve the immediate stability of soil in areas with light loads. They can serve as a temporary layer to hold the soil in place, promoting vegetation growth that will ultimately take over the stabilizing role [

26]. These materials will provide structural support while allowing plants to root, after which the geotextile will decompose. Research confirmed that vegetation grew easily through the feather-based geotextile thanks to its fluffy structure [

27]. The proportions of biodegradable and non-biodegradable fibers in nonwoven can be adjusted based on the difficulty of the soil conditions. In areas more prone to erosion, variants with a higher PLA content will be used. Partial biodegradation will facilitate plant rooting, while the remaining nonwoven layer will support vegetation in stabilizing the ground.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.-P., K.W.-T. and T.K.; methodology: J.J.-P. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.-P. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, J.J.-P., J.W. and K.W-T.; visualization, J.J.-P.; supervision, J.J.-P., K.W.-T., T.K. and J.W.; project administration, K.W.-T.; funding acquisition, K.W.-T.; project Leader and contributed to the final discussion of the results, K.W.-T.; participation in feather-based nonwoven manufacturing, J.W., T.K. and M.P.

Funding

This research ”UNLOCKING A NEW FEATHER-BASED BIOECONOMY FOR KERATIN-BASED AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS”, UNLOCK project was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement Nº 101023306.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results

References

- Ibrahim, A.D.; Rabah, A.B.; Ibrahim, M.L.; Magami, I.M.; Isah J.G.; Muzoh, O.I. Bacteriological and chemical properties of soil amended with fermented poultry bird feather. Int J Biol Chem Sci 2014 Vol. 8(3), 1243–1248. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, WF. Innovative feather utilization strategies. In: Proceedings national poultry waste management symposium. Auburn University Printing Services 1998 19–22.

- Joardar, J.C.; Rahman, M.M. Poultry feather waste management and effects on plant growth. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture, 2018 Vol.7(7), 183–188. [CrossRef]

- Lasekan, A.; Bakar, A.F.; Hashim, D. Potential of chicken by-products as sources of useful biological resources. Waste Manag. 2013; 33(3):552–565. [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Adhikary, R.; Bera, M.; Krishiviswavidyala, B. C.; & Bengal, W. Application of Different Geotextile in Soil to Improve the Soil Health in Humid and Hot Sub Humid Region of West Bengal , India Application of Different Geotextile in Soil to Improve the Soil Health in Humid and Hot Sub Humid Region of West Bengal, India. Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci. 2020 9(6), 2812–2818. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.J.; Barton, A.P.; Fullen, M.A.; Hocking, T.J., Wu Bo, Z.; Zheng, Y. Field studies of the effects of jute geotextiles on runoff and erosion in Shropshire, UK. Soil Use and Management 2003 19(2), 182-184.

- Pritchard, M.; Sarsby, R.W.; Anand, S.C. Textiles in civil engineering. Part 2- natural fibre geotextiles, [In:] A.R. Horrocks, S.C. Anand (Eds.), Handbook of Technical Textiles, Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, England, 2000 pp.372-405. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.; Perween, T.; & Datta, P. Assessing the Effect of Geotextile Mulch on Yield and Physico-Chemical Qualities of Litchi . A New Technical Approach. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 2019 8(07), 1984–1989. [CrossRef]

- Slezak, R.; Krzystek, L.; Puchalski, M.; Krucińska, I. Sitarski, A. Degradation of bio-based film plastics in soil under natural conditions. Science of The Total Environment 2023, Vol. 866, 25, 161401. [CrossRef]

- Emadian, S.M.; Onay, T.T.; Demirel, B. Biodegradation of bioplastics in natural environments. Waste Manag. 2017 Vol. 36 , pp. 576-583. [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, D.; Mistriotis, A. Key parameters in testing biodegradation of bio-based materials in soil. Chemosphere, 2018 Vol. 207, pp. 18-26. [CrossRef]

- Camacho Muñoz, R.; Villada Castillo, H.S.; Hoyos Concha, J.L.; Solanilla Duque, J.F. Aerobic biodegradation of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) in thermoplastic starch (TPS) blends in soil induced by gelatin. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 2024, Vol. 193, 105831. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Ozturk, M.; Frey, M. Soil biodegradation of cotton fabrics treated with common finishes. Cellulose 2021 Vol. 28, 4485–4494. [CrossRef]

- Jóźwik-Pruska, J.; Wrześniewska-Tosik, K.; Mik, T.; Wesołowska, E.; Kowalewski, T.; Pałczyńska, M.; Walisiak, D.; Szalczyńska, M. Biodegradable nonwovens with poultry feather addition as a 2 way of recycling and waste management. Polymers 2022 14 (12), 2370. [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E.; Briassoulis, D. Degradation behaviour of poly(lactic acid) films and fibres in soil under Mediterranean field conditions and laboratory simulations testing. Industrial Crops and Products 2011 Vol. 33 (3), 648-658. [CrossRef]

- Chuensangjun, C.; Pechyen, C.; Sirisansaneeyakul, S. Degradation Behaviors of Different Blends of Polylactic Acid Buried in Soil. Energy Procedia. 2013 Vol. 34, 73-82. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H. Poly (lactic acid). Bio-based plastics: materials and applications 2013 171-239. [CrossRef]

- Zaaba, N.F.; Jaafar, M. A review on degradation mechanisms of polylactic acid: Hydrolytic, photodegradative, microbial, and enzymatic degradation. Polym Eng Sci. 2020 60, 2061–2075. [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, Y.; Calabia, B.P. Biodegradability and biodegradation of poly(lactide). Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006 Vol. 72, 2, 244-51. [CrossRef]

- Khabbaz, F.; Karlsson, S.; Albertsson, A.-C. PY-GC/MS an effective technique to characterizing of degradation mechanism of poly (L-lactide) in the different environment. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000 Vol.78, 2369-2378. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, B.; Pająk, J. Biodegradacja polilaktydu (PLA). Archiwum Gospodarki Odpadami i Ochrony Środowiska 2010 Vol. 2, 1-10, ISSN 1733-4381 in polish.

- Karamanlioglu, M.; Robson, G.D. The influence of biotic and abiotic factors on the rate of degradation of poly(lactic) acid (PLA) coupons buried in compost and soil. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2013 Vol.98, 2063-2071. [CrossRef]

- Jarerat, A.; Tokiwa, Y. Poly(L-lactide) degradation by Saccharothrix waywayandensis. Biotechnol Lett. 2003 Vol.25, 1, 401-404. [CrossRef]

- Artham, T.; Doble, M. Biodegradation of aliphatic and aromatic polycarbonates. Macromol. Biosci. 2008 Vol.8, 1, 14-24. [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk-Walach, M.; Gzyra-Jagieła, K.; Milczarek, A.; Jóźwik-Pruska, J. Characterization of Potential Pollutants from Poly(lactic acid) after the Degradation Process in Soil under Simulated Environmental Conditions. AppliedChem. 2021 Vol.1, 156-172. [CrossRef]

- Mwasha, A. Using environmentally friendly geotextiles for soil reinforcement: A parametric study. Materials & Design. 2009 Vol. 30(5), 1798-1803. [CrossRef]

- Kacorzyk, P.; Strojny, J.; Białczyk, B. The Impact of Biodegradable Geotextiles on the Effect of Sodding of Difficult Terrain. Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13(11), 5828. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).