Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The rapid evolution of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) has created significant opportunities for industrial transformation, while simultaneously presenting substantial challenges to network security. Among these challenges, physical layer security emerges as a critical factor in ensuring the integrity and reliability of message transmission across interconnected devices and sensors within complex industrial environments. In our previous work, we proposed a mechanism for assessing the Spatial Secrecy Outage Probability (SSOP) in a Rayleigh Channel with a single eavesdropper, achieving promising simulation results. This paper focuses on the Nakagami-m Wiretap Channel and multiple eavesdroppers assuming that the location of legitimate devices is known, while the eavesdropper devices have a spatially homogeneous Poisson point process distribution of locations, forming the SSOP models related to the device locations from the perspective of insecure regions (ISRs) and secure regions (SRs), and the closed-form expression for its upper bound is derived. Subsequently, under the constraints imposed by SSOP conditions, we establish an optimization model aimed at maximizing system secrecy throughput. Finally,we analyze ISRs and SRs based on geographical location information through the lens of Secrecy Outage Probability (SOP), evaluating the security performance of our system. Through advanced modeling and simulation in MATLAB, we validated the accuracy of the proposed definition and derived the upper bound for the SSOP under Nakagami-m Channel. The experimental results further demonstrate the deep relationship between Secrecy Rate and Throughput. Additionally, it was observed that as the secrecy rate increases, the secrecy outage probability also rises, necessitating careful consideration of the trade-off. These insights are crucial for understanding and enhancing the security performance of IIoT communication systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Focusing on the scenario in MISO systems with multiple eavesdropping users, the paper models the locations of eavesdroppers using a Poisson point process. It analyzes the spatial outage probability under Nakagami-m channel fading and derives a closed-form expression for its upper bound.

- After deriving the spatial outage probability, this paper investigates and analyzes the relationship between secrecy rate and secrecy throughput in the given scenario. With the optimization objective of maximizing the minimum average secrecy rate and under the constraint of secrecy outage probability, the system’s secrecy throughput is validated.

- In this channel environment, the paper also explores the issues of secure and non-secure regions under the constraint of secrecy outage probability. It analyzes the system’s security performance, providing theoretical guidance for practical applications.

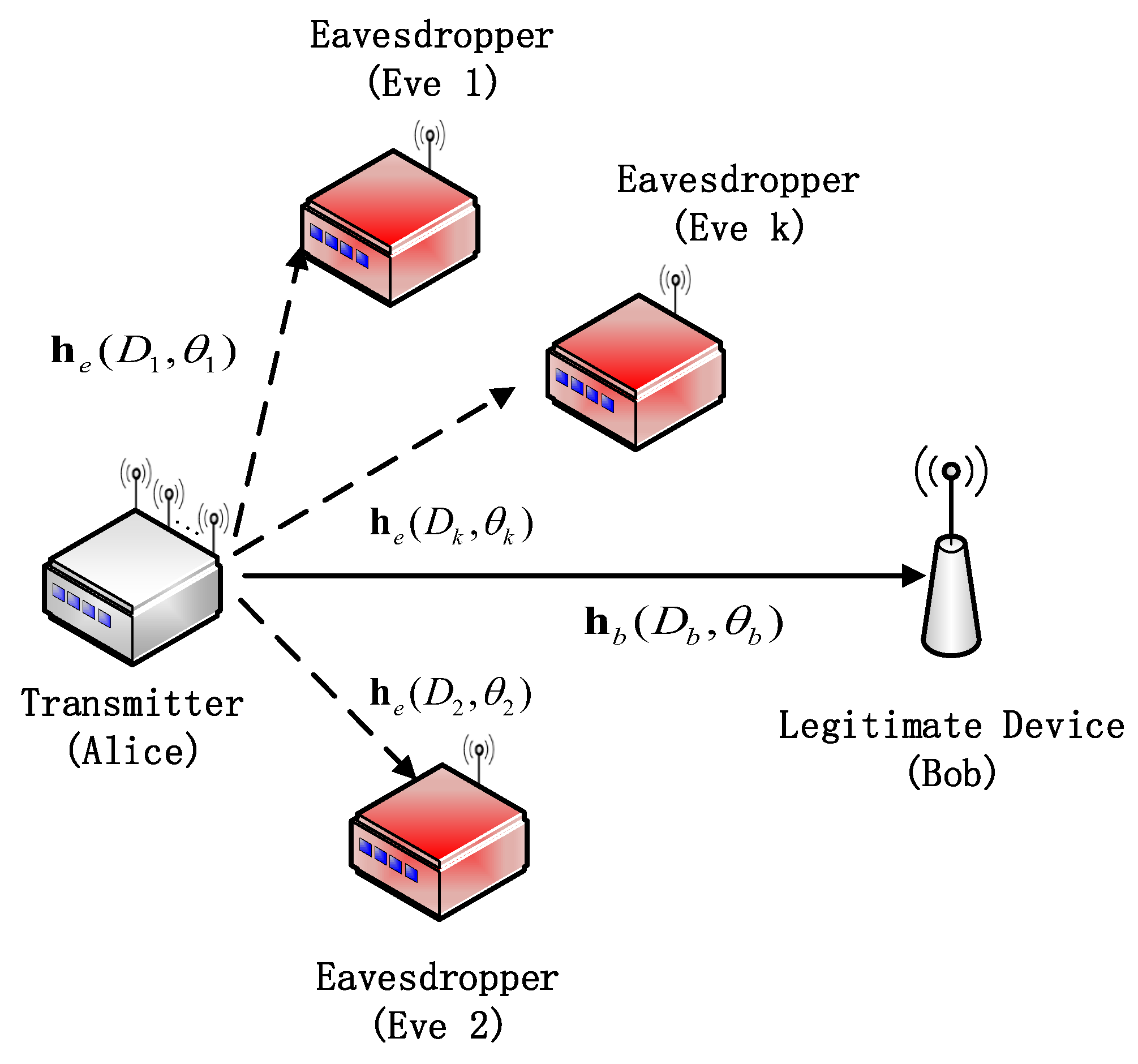

2. SYSTEM MODEL

3. Algorithm Design and Implementation

3.1. Analysis of Spatial Secrecy Outage Probability under Nakagami-m Channel Fading

- : in this situation, the secrecy capacity of the legitimate channel is less than , resulting that Transmission errors or distortions are inevitable in the transmitted information, and transmission interruption occurs.

- : for this scenario, If the channel capacity of Eve is greater than , at this time Eve can eavesdrop on the confidential information and the system will experience a secrecy outage.

- and : under this circumstance, the system is able to achieve the secure and confidential transmission of data.

3.1.1. Determine the Insecure Region

3.1.2. Construct the SSOP Based on the Number of Eavesdropping Users in the Insecure Region

3.1.3. Closed-Form Solution of SSOP

3.2. Analysis of Secrecy Throughput

3.3. Analysis of Secure Region Based on Secrecy Outage Probability

4. Simulation Results

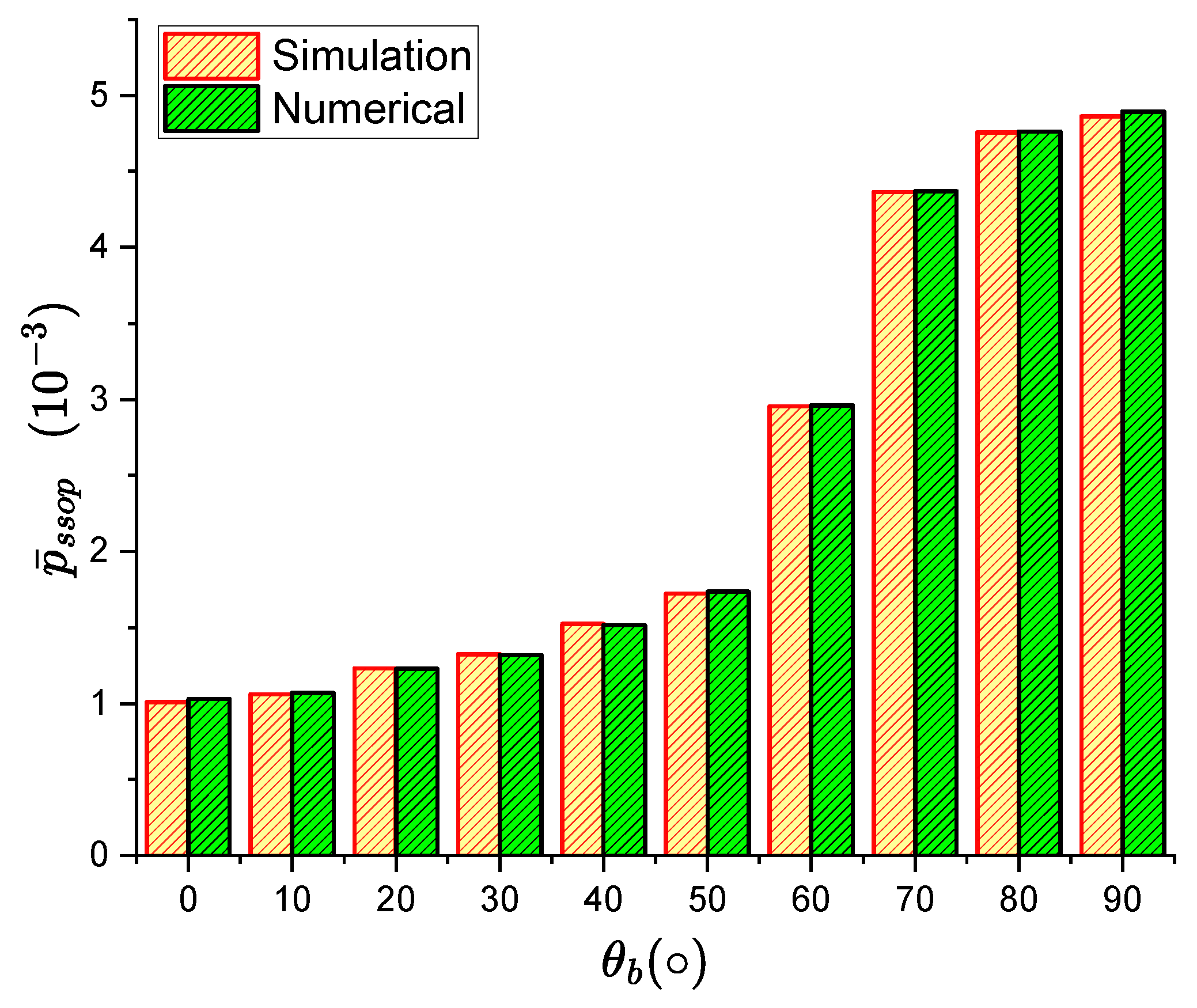

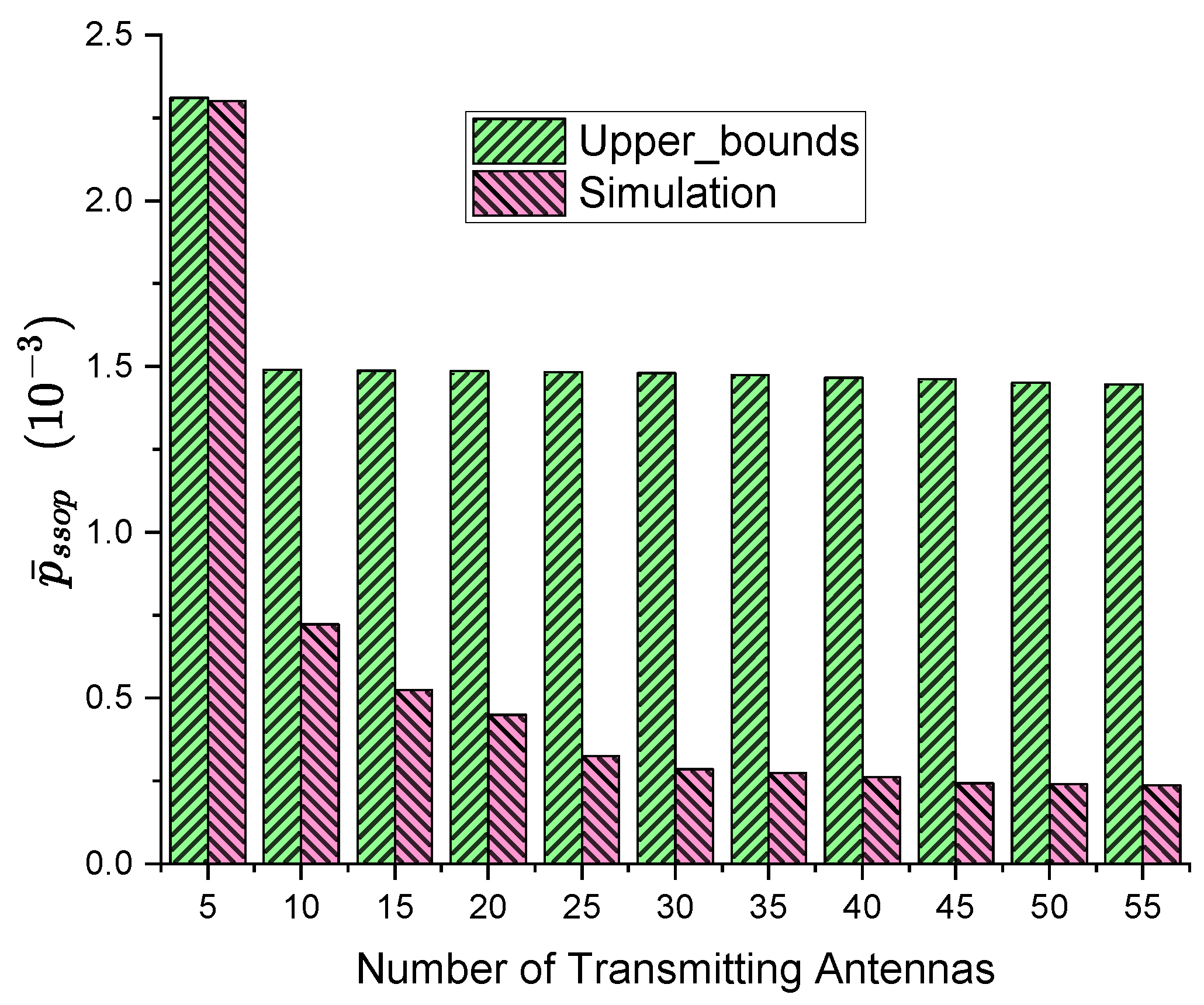

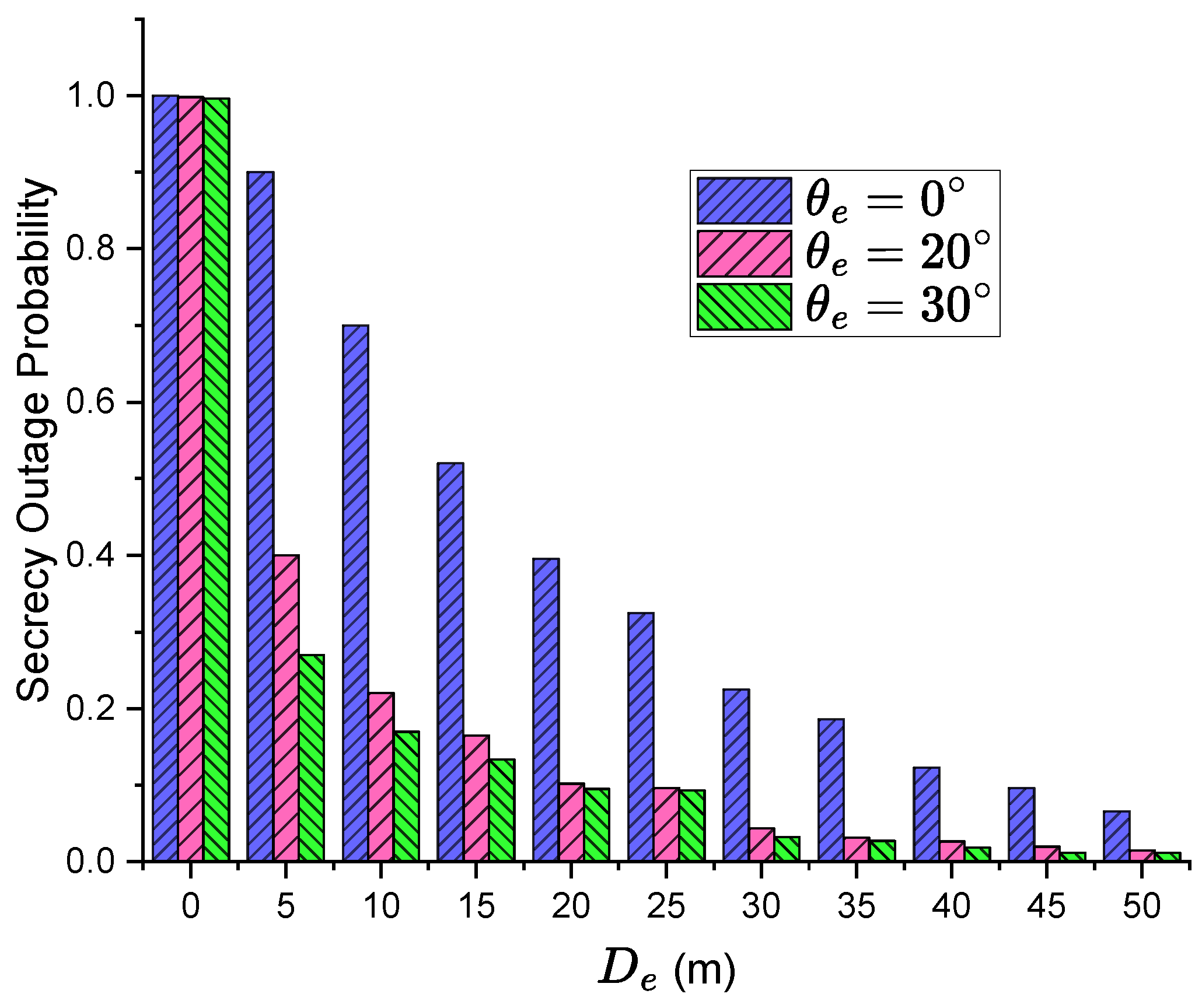

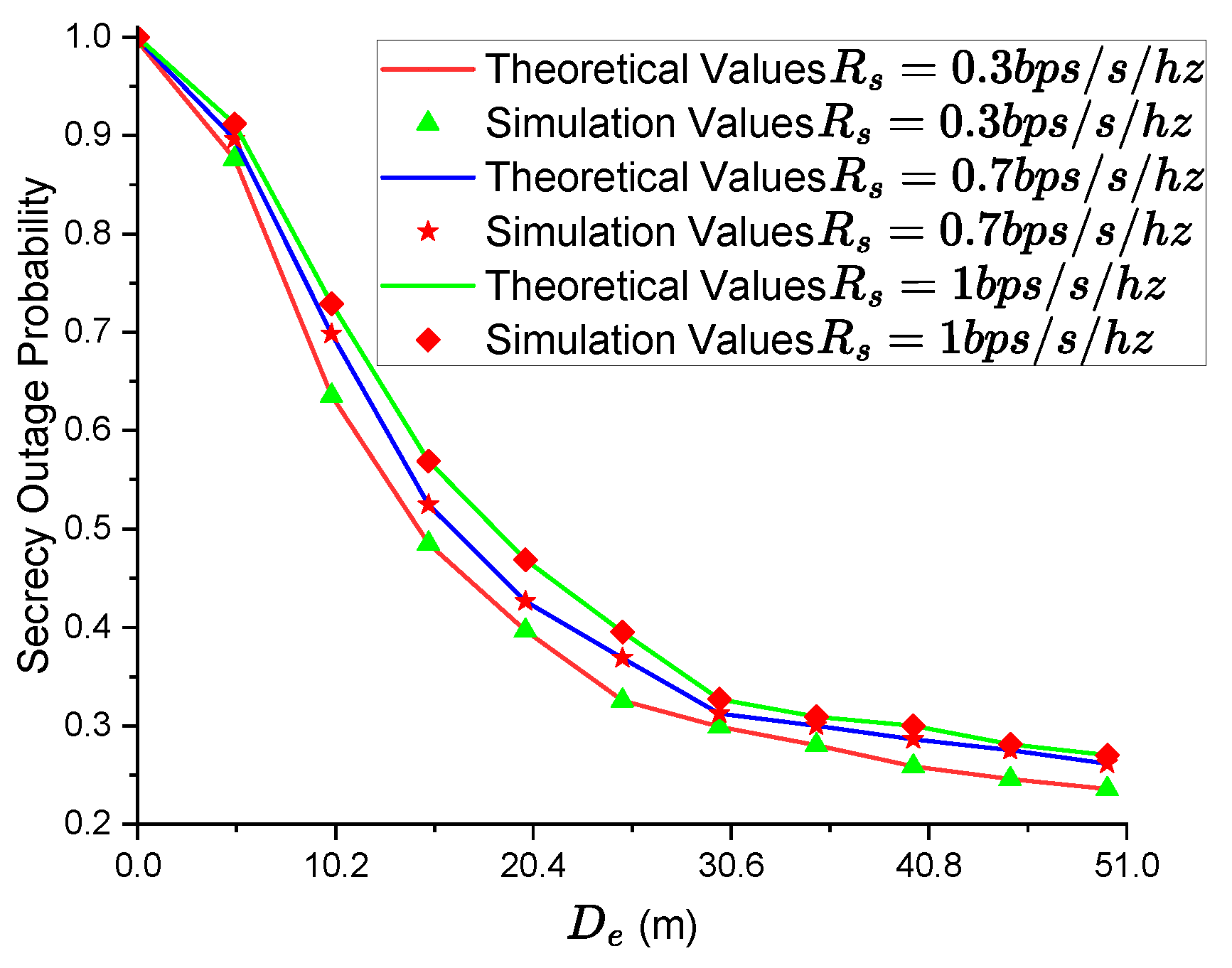

4.1. Simulation and Analysis of Spatial Secrecy Outage Probability

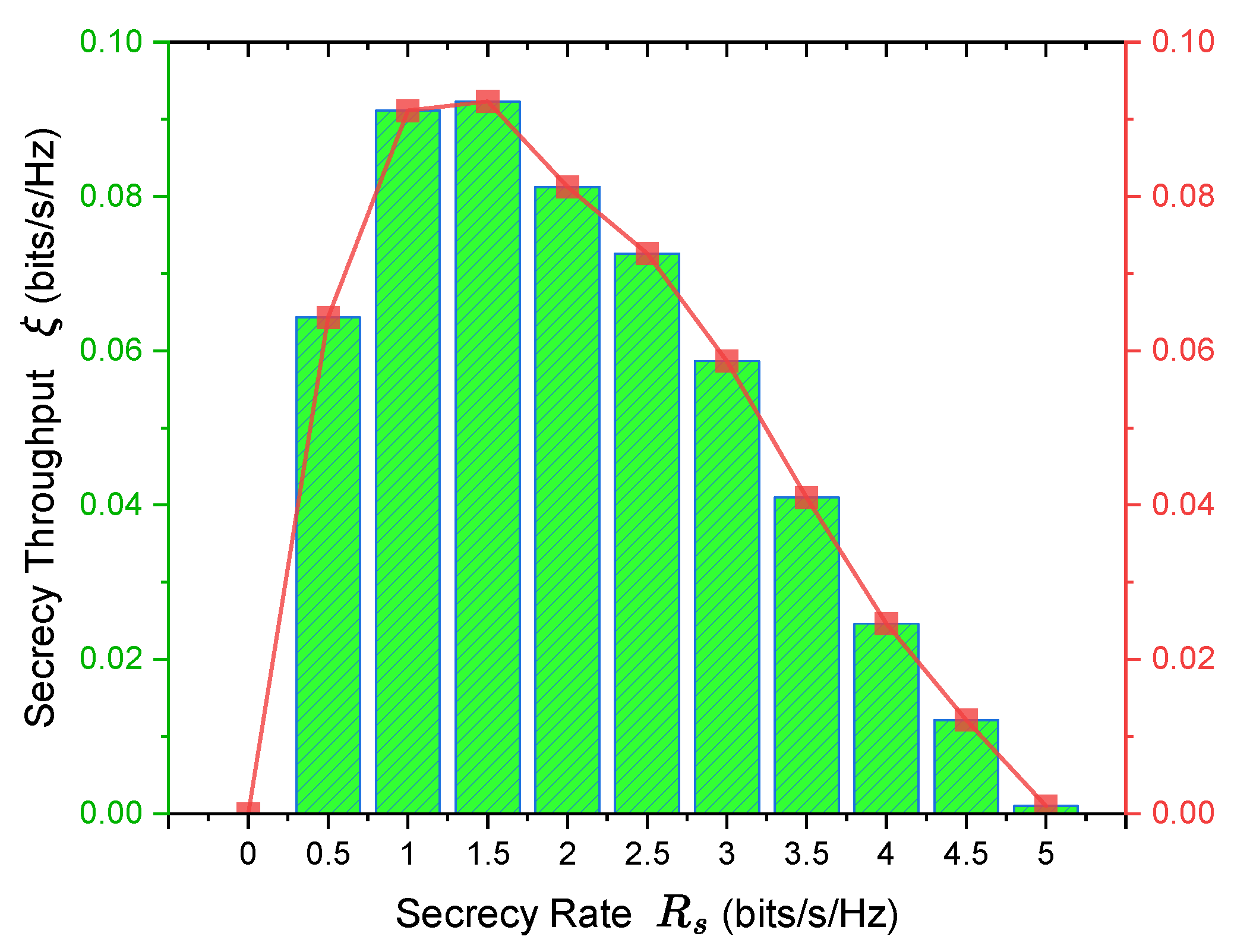

4.2. Analysis of Secrecy Throughput

4.3. Analysis of Secure Area Based on Secrecy Outage Probability

5. Conclusions

Appendix A Appendix A

References

- Liu, X.; Xu, F.; Ning, L. A Novel Approach for the Enhancement of Security through Defining the Spatial Secrecy Outage Probability in the Industrial Internet of Things. ELECTRONICS 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wen, L.; Feng, H.; Fang, K.e. An Overview of Security Threats, Attack Detection and Defense for Large-Scale Multi-Agent Systems (LSMAS) in Internet of Things (IoT). IEEE Transactions on Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems 2025, 3, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidlou, S.; Ghadiminia, N.; Oti-Sarpong, K. Cyber-physical System Security for Manufacturing Industry 4.0 using LSTM-CNN Parallel Orchestration. IEEE Access 2025, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, L.; Tang, C. A Vehicle Path Planning and Prediction Algorithm Based on Attention Mechanism for Complex Traffic Intersection Collaboration in Intelligent Transportation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Othman, M.A.; Mohamed, W.M. Internet of Things in Smart Cities: Comprehensive Review, Open Issues, and Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 34941–34952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, H.; Liu, S. Physical Layer Authentication for Industrial Control Based on Convolutional Denoising Autoencoder. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 15633–15641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chi, C.; Zhang, Y. Identification and Resolution for Industrial Internet: Architecture and Key Technology. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 16780–16794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serror, M.; Hack, S.; Henze, M. Challenges and Opportunities in Securing the Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 17, 2985–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcginthy, J.M.; Michaels, A.J. Secure Industrial Internet of Things Critical Infrastructure Node Design. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 8021–8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Yan, B.; Yang, T. Security-Enhanced Operational Architecture for Decentralized Industrial Internet of Things: A Blockchain-Based Approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 11073–11086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ud Din, I.; Bano, A.; Awan, K.A. LightTrust: Lightweight Trust Management for Edge Devices in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 2776–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; Lee, M.H.; Wu, B.C. A Lightweight Power Side-Channel Attack Protection Technique With Minimized Overheads Using On-Demand Current Equalizer. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2022, 69, 4008–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; He, D.; Qiao, Q. A Lightweight and Secure Communication Protocol for the IoT Environment. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2024, 21, 1050–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbasiya, T.; Das, D.; Das, S.K. MComIoV: Secure and Energy-Efficient Message Communication Protocols for Internet of Vehicles. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 2021, 29, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Yin, L.; Tan, J. An Autoencoder-Based Hybrid Detection Model for Intrusion Detection With Small-Sample Problem. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2024, 21, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaidja, T.E.T.; Brik, B.; Senouci.etl, M. Early Network Intrusion Detection Enabled by Attention Mechanisms and RNNs. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024, 19, 7783–7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Mehmood, A.; Maple, C. Performance Analysis of Blockchain-Enabled Security and Privacy Algorithms in Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024, 25, 4773–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, Z.; Wang, Y. Energy-Efficient and Physical-Layer Secure Computation Offloading in Blockchain-Empowered Internet of Things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 6598–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, T.; Mahmoud. Internet of Things (IoT) Security: Current Status, Challenges and Countermeasures. International Journal for Information Security Research (IJISR) 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fuqaha, A.; Guizani, M.; Mohammadi, M. Internet of Things: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications. IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials 2015, 17, 2347–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoris-Kogias, E.; Voutyras, O.; Varvarigou, T. TRM-SIoT: A scalable hybrid trust and reputation model for the social Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation, 2016.

- Lin, J.; Yang, X.; Yu, W.; Fu, X. Towards Effective En-Route Filtering against Injected False Data in Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the Global Telecommunications Conference, 2011.

- Suo, H.; Wan, J.; Zou, C. Security in the Internet of Things: A Review. IEEE 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A. Physical-Layer Security in the Internet of Things: Sensing and Communication Confidentiality Under Resource Constraints. Proceedings of the IEEE 2015, 103, 1747–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcginthy, J.M.; Michaels, A.J. Secure Industrial Internet of Things Critical Infrastructure Node Design. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 8021–8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, C.; Herbst, J.; Klingel, S. Connectivity in the era of the (I) IoT: about security, features and limiting factors of reconfigurable intelligent surfaces. Discover Internet of Things 2023, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wu, F.; Chen, B. A parallel game model-based intrusion response system for cross-layer security in industrial internet of things. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2023, 35, 7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hu, M.; Yan, H. Research on industrial internet of things security architecture and protection strategy. In Proceedings of the 2019 International conference on virtual reality and intelligent systems (ICVRIS). IEEE, 2019, pp. 365–368.

- Islam, S.N.; Baig, Z.; Zeadally, S. Physical layer security for the smart grid: Vulnerabilities, threats, and countermeasures. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2019, 15, 6522–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. Secure transmission strategy of network communication layer relay based on satellite transmission. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Information Technology and Computer Application (ITCA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 268–271.

- Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, N.L.; Nguyen, N.T. Reliable and secure transmission in multiple antennas hybrid satellite-terrestrial cognitive networks relying on NOMA. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 215044–215056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Lu, W. Distributed few-shot learning for intelligent recognition of communication jamming. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2021, 16, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, N. Radio frequency fingerprint collaborative intelligent identification using incremental learning. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 2021, 9, 3222–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, C.; Li, M. Intelligent passive detection of aerial target in space-air-ground integrated networks. China Communications 2022, 19, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Woods, R.; Ko, Y. Security Optimization of Exposure Region-Based Beamforming With a Uniform Circular Array. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2018, 66, 2630–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ko, Y.; Woods, R. Defining Spatial Secrecy Outage Probability for Exposure Region-Based Beamforming. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2017, 16, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H. Efficient beamforming training for 60-GHz millimeter-wave communications: A novel numerical optimization framework. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2013, 63, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashar, B.S.; Rhazali, Z.; Elwi, T.A. Antenna Beam forming Technology Based Enhanced Metamaterial Superstrates. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 3rd KhPI Week on Advanced Technology (KhPIWeek). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–5.

- Xiong, Q.; Gong, Y.; Liang, Y.C. Achieving secrecy of MISO fading wiretap channels via jamming and precoding with imperfect channel state information. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2014, 3, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barb, G.; Otesteanu, M. Digital GoB-based Beamforming for 5G communication systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 international symposium on antennas and propagation (ISAP). IEEE, 2021, pp. 469–470.

- Wang, B.; Mu, P.; Li, Z. Artificial-Noise-Aided Beamforming Design in the MISOME Wiretap Channel Under the Secrecy Outage Probability Constraint. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2017, 16, 7207–7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wen, H.; Wu, B. Cooperative-Jamming-Aided Secrecy Enhancement in Wireless Networks With Passive Eavesdroppers. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2018, 67, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mu, P.; Li, Z. An Adaptive Transmission Scheme for Slow Fading Wiretap Channel with Channel Estimation Errors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Globecom 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Talak, R.; Karaman, S.; Modiano, E. Improving age of information in wireless networks with perfect channel state information. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 2020, 28, 1765–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Pang, S.; Zhang, W. Linear shrinkage receiver for slow fading channels under imperfect channel state information. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Information Theory Workshop (ITW). IEEE, 2022, pp. 338–343.

- Xie, R.; Tang, Q.; Liang, C. Dynamic computation offloading in IoT fog systems with imperfect channel-state information: A POMDP approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 8, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.B.; Prvulovic, M.; Zajić, A. Electromagnetic side channel information leakage created by execution of series of instructions in a computer processor. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2019, 15, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Xiao, Y.; Lei, X. When the CSI from Alice to Bob is Unavailable: What Can Eve Do to Eliminate the Artificial Noise? In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 96th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2022-Fall). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–5.

- Xia, G.; Lin, Y.; Liu, T. Transmit antenna selection and beamformer design for secure spatial modulation with rough CSI of Eve. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2020, 19, 4643–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, G.; Xu, J. Over-the-air computation with imperfect channel state information. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 23rd International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communication (SPAWC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–5.

- Wang, J.; Lee, J.; Wang, F. Jamming-aided secure communication in massive MIMO Rician channels. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2015, 14, 6854–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, S.; Shukla, S.; Kuri, J. Joint scheduling & jamming for data secrecy in wireless networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 11th International Symposium and Workshops on Modeling and Optimization in Mobile, Ad Hoc and Wireless Networks (WiOpt). IEEE, 2013, pp. 248–255.

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Hou, W. Security enhancement in cooperative jamming using compromised secrecy region minimization. In Proceedings of the 2013 13th Canadian Workshop on Information Theory. IEEE, 2013, pp. 214–218.

- Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Kuo, Y. Artificial-Noise-Aided Optimal Beamforming in Layered Physical Layer Security. IEEE Communications Letters 2019, 23, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Zang, G. Artificial-Noise-Aided Robust Beamforming for MISOME Wiretap Channels with Security QoS. IEEE 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, J. Secrecy Outage Probability Analysis of Friendly Jammer Selection Aided Multiuser Scheduling for Wireless Networks. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2019, pp. 1–1.

- Wang, X.; Mu, P.; Zhang.etl. Secrecy CPS transmission scheme for slow fading independent parallel wiretap channels with new SOP constraint. 2018, pp. 1–6.

- Zhou, Y.; Yeoh, P.L.; Chen, H. Improving Physical Layer Security via a UAV Friendly Jammer for Unknown Eavesdropper Location. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2018, 67, 11280–11284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Details | Setting Value |

|---|---|---|

| Transmit Power | 40dBm | |

| Number of Antennas | 8 | |

| Noise variance | 30dBm | |

| Outage Probability Threshold | 0.1 | |

| Angle of Incidence | ||

| , | Nakagami-m Distribution Parameter | 1,1 |

| , | Nakagami-m Distribution Parameter | 1,1 |

| Secrecy Rate | 0.5bps/hz | |

| Poisson Distribution Parameter | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).