Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data

3. Methods

3.1. Front Detection

3.2. Front Mapping, Front Intensity, and Front Stability

3.3. Front Strength and Cross-Frontal Ranges of Oceanic Variables

3.4. Logarithmic Transformation of SST Gradient

4. Results

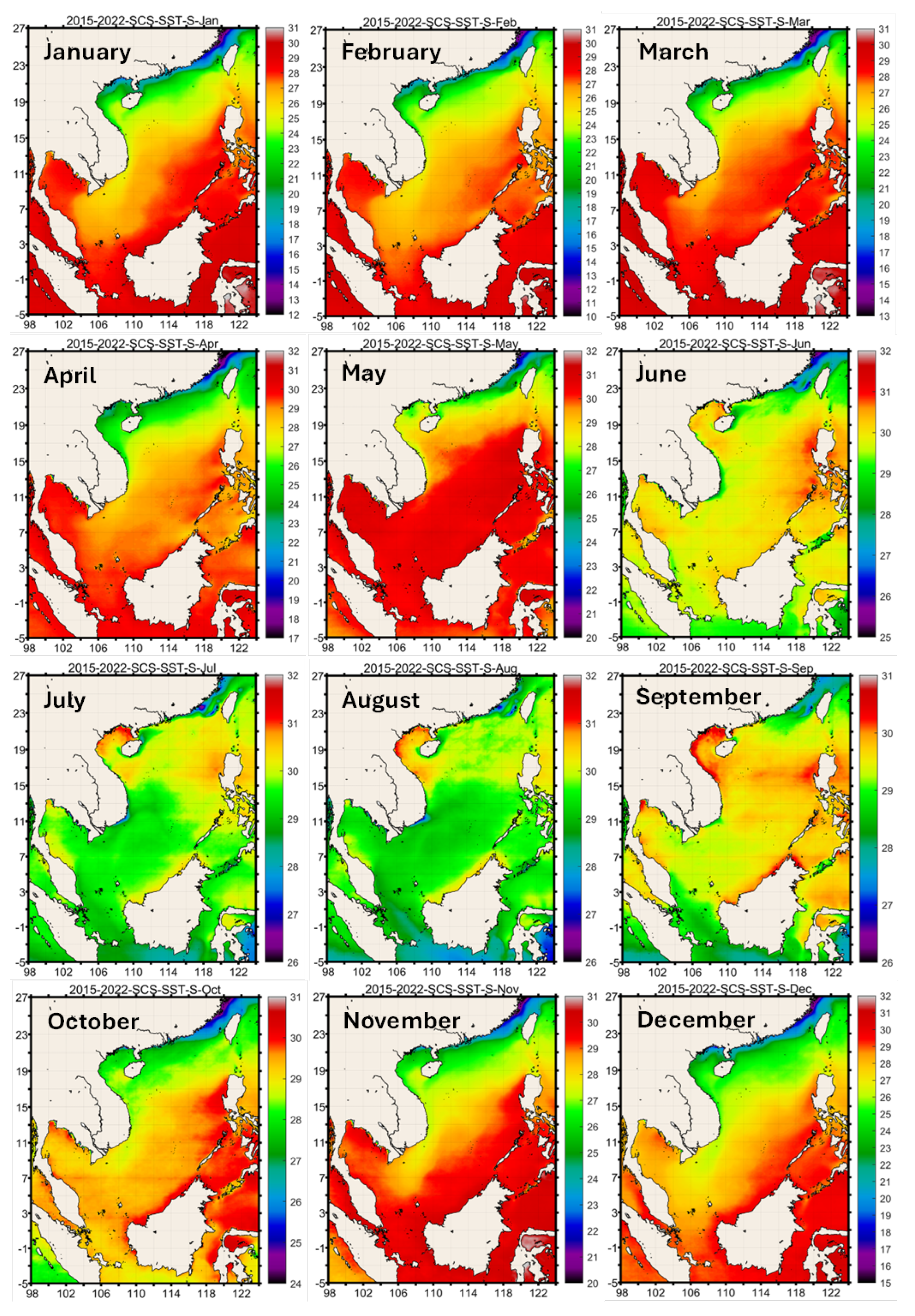

4.1. Sea Surface Temperature and Its Seasonal Variability: Large-Scale Pattern and Meso-Scale Features

4.1.1. Cold Tongue in Winter

4.1.2. Rapid Warming in Spring

4.1.3. Rapid Cooling in June-July

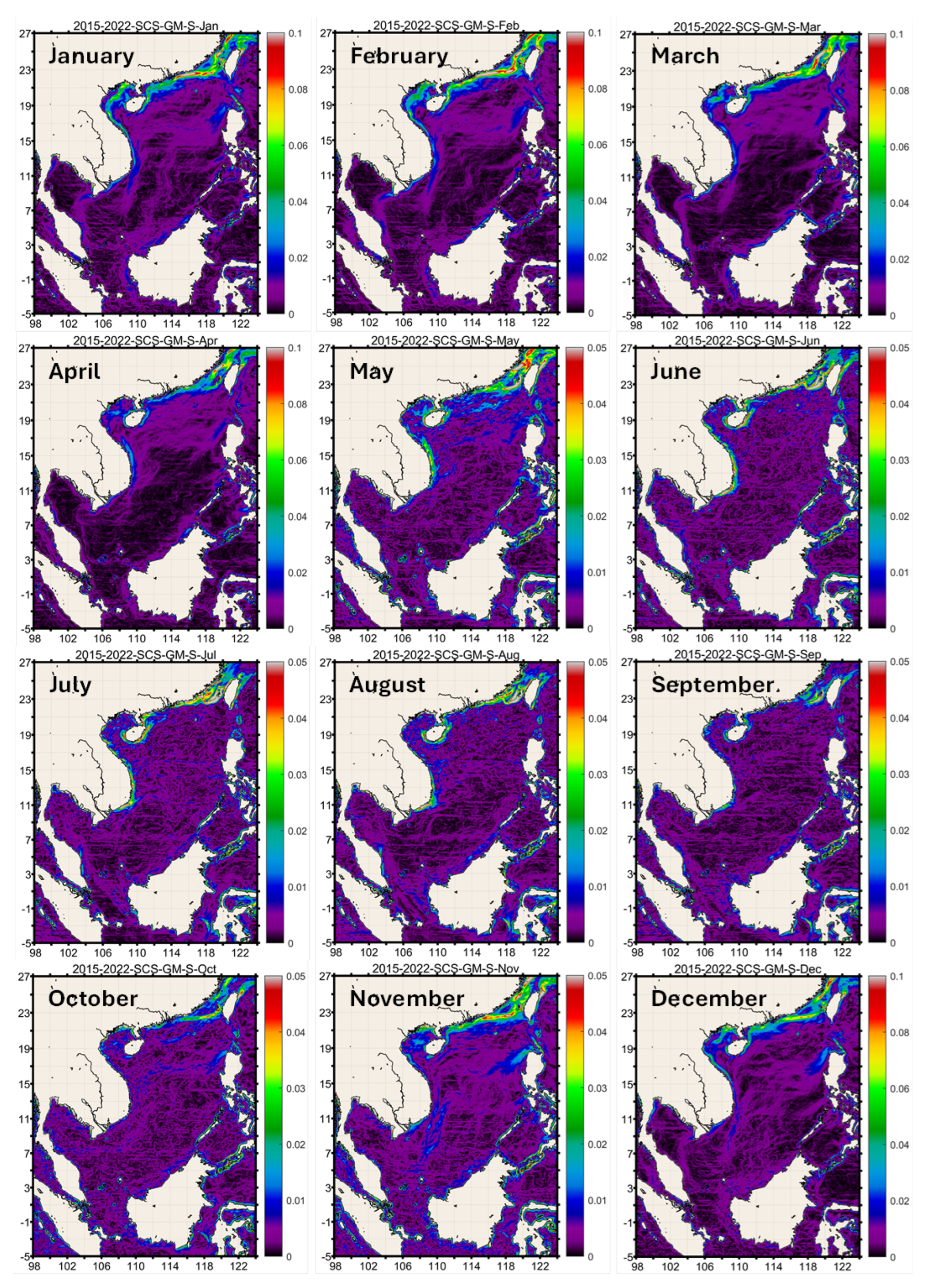

4.2. SST Gradients

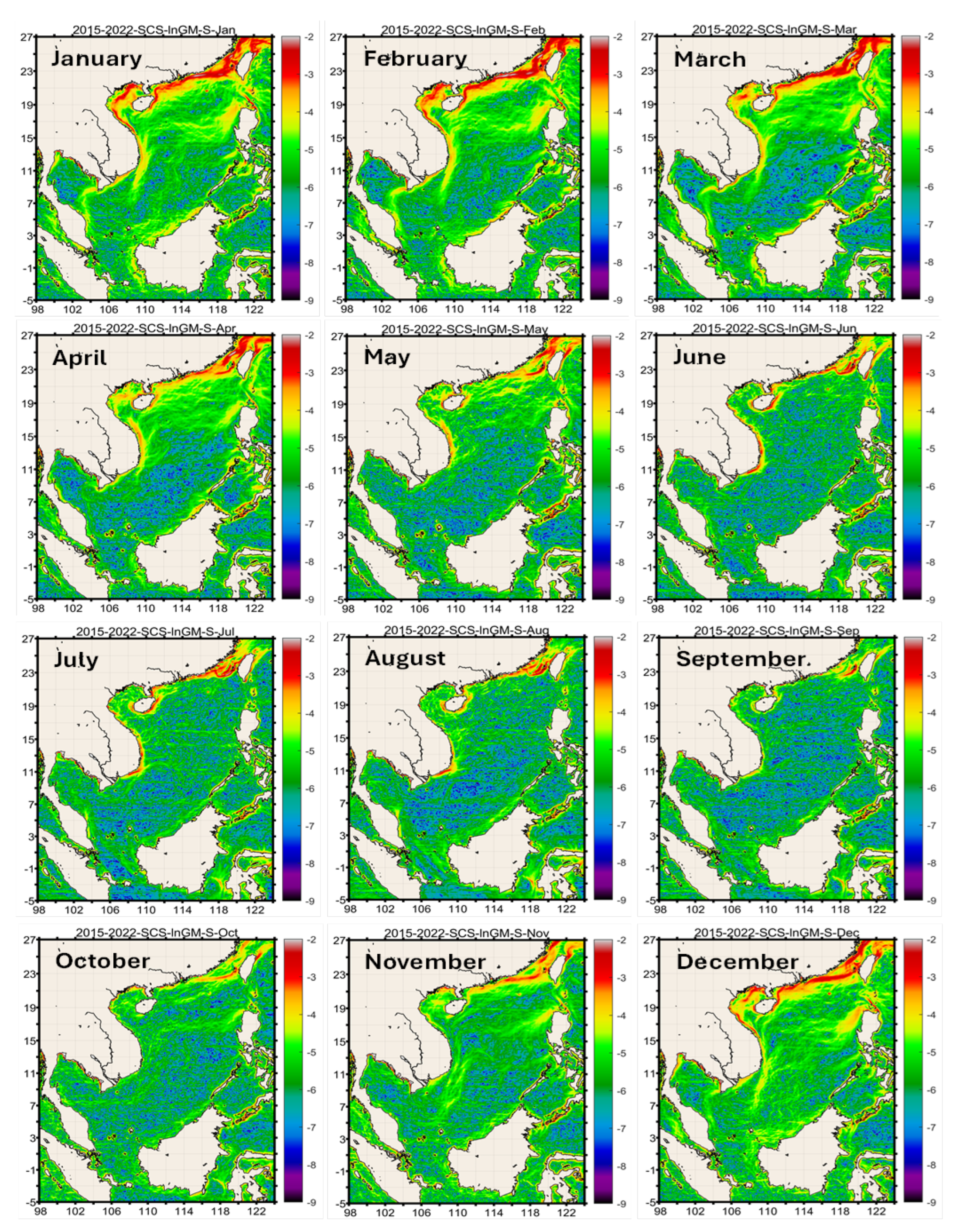

4.3. Log-Transformed Gradient of SST

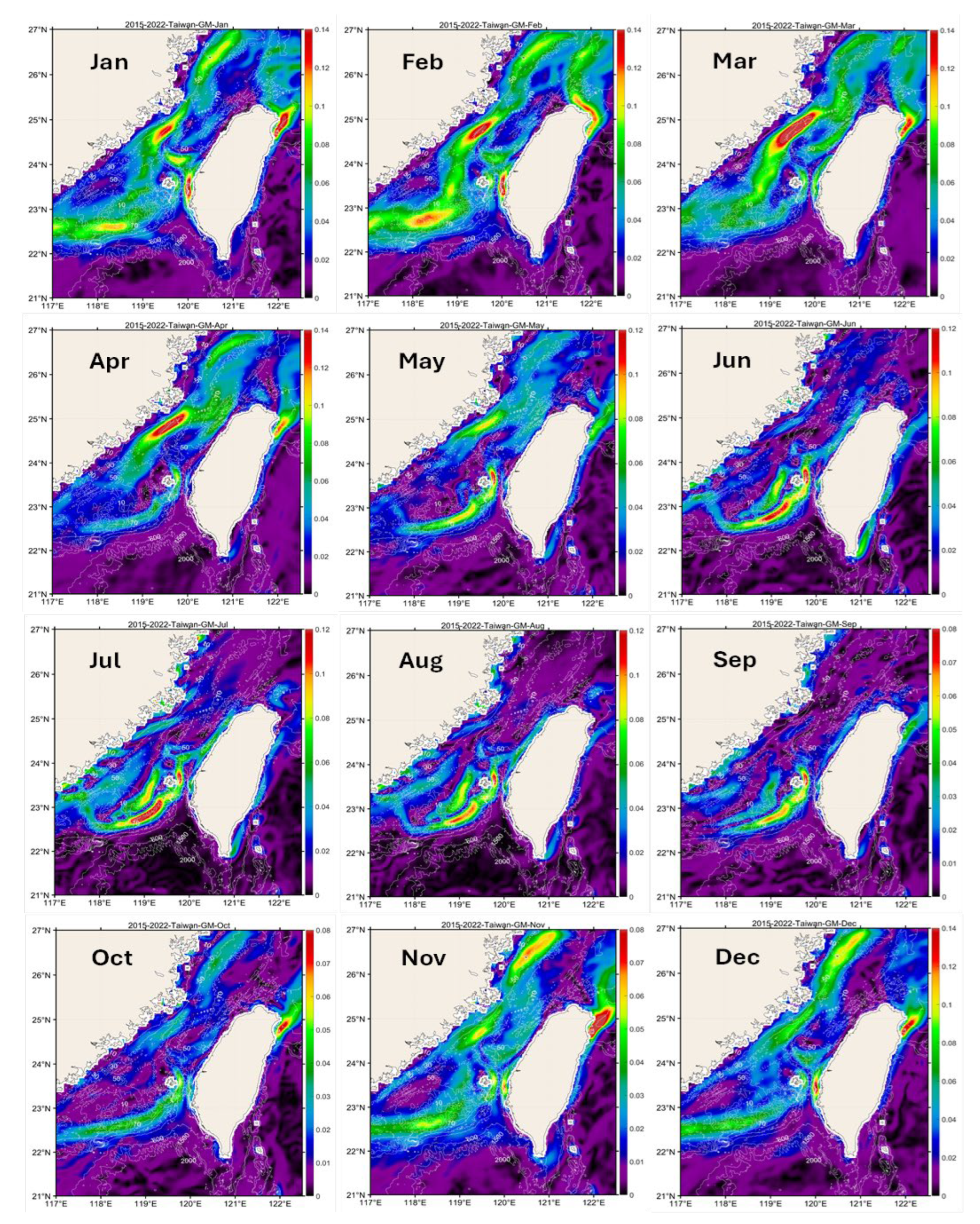

4.4. Region 1: Taiwan Strait

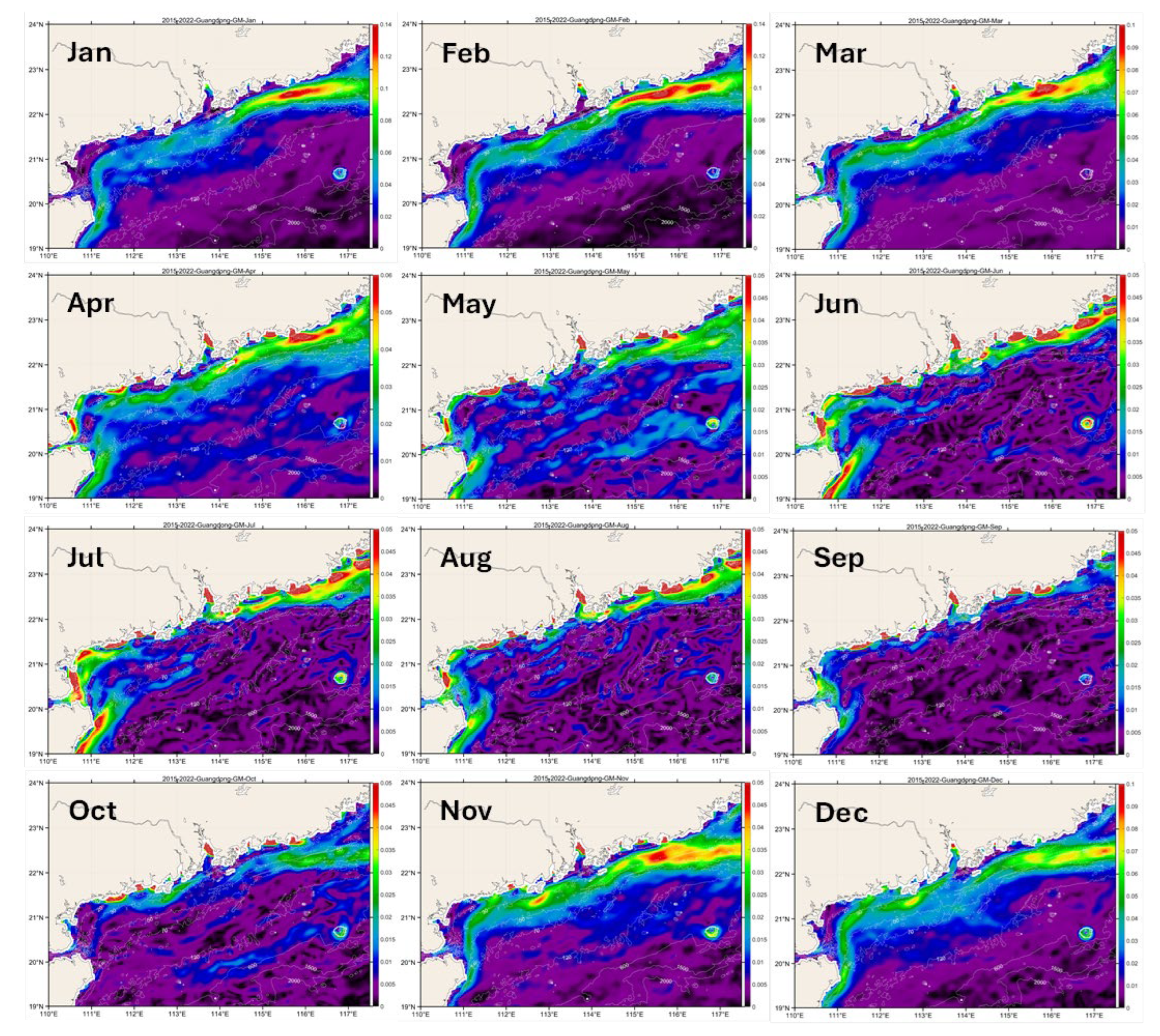

4.5. Region 2: Guangdong Shelf

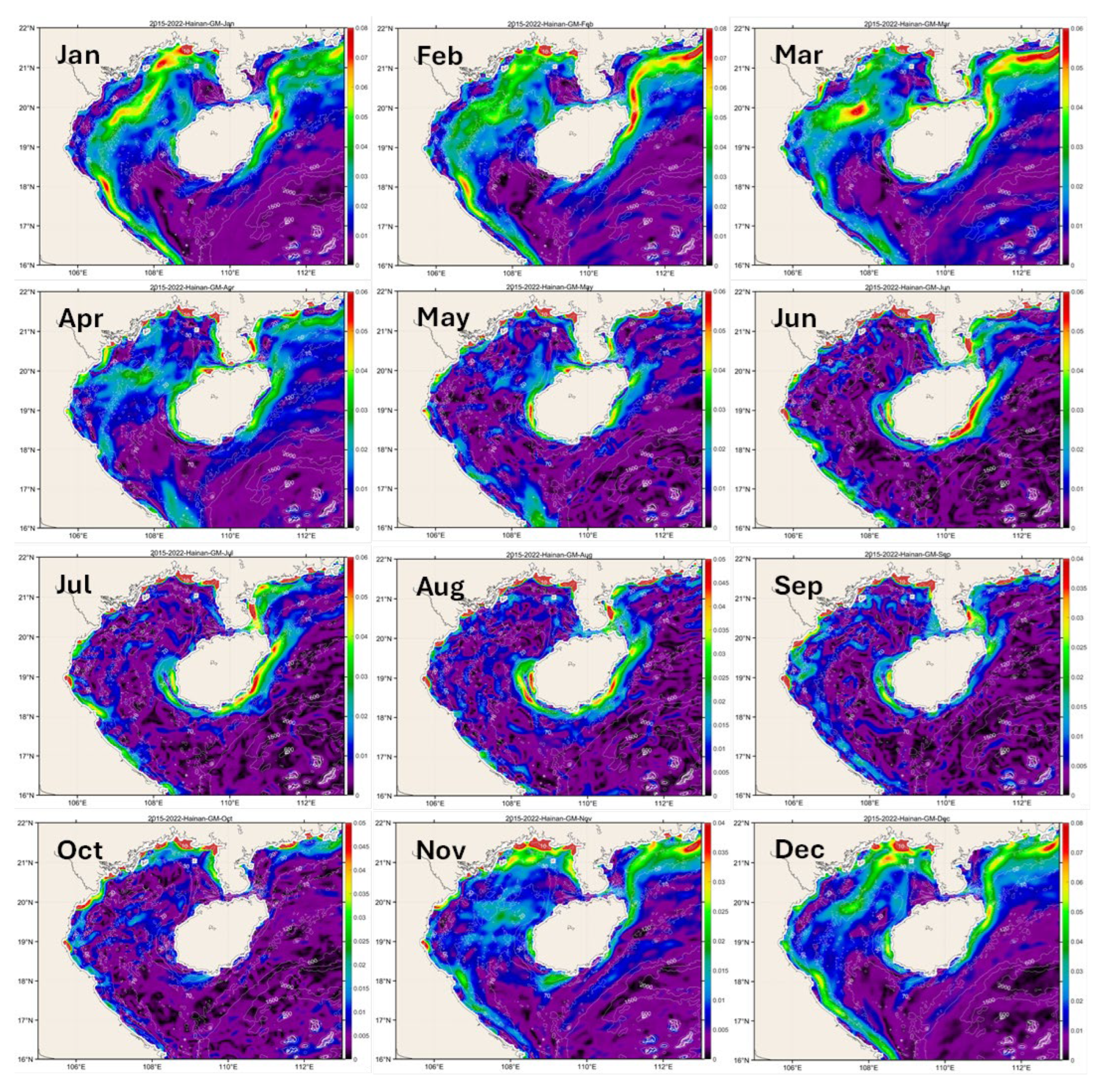

4.6. Region 3: Hainan Island and Beibu Gulf

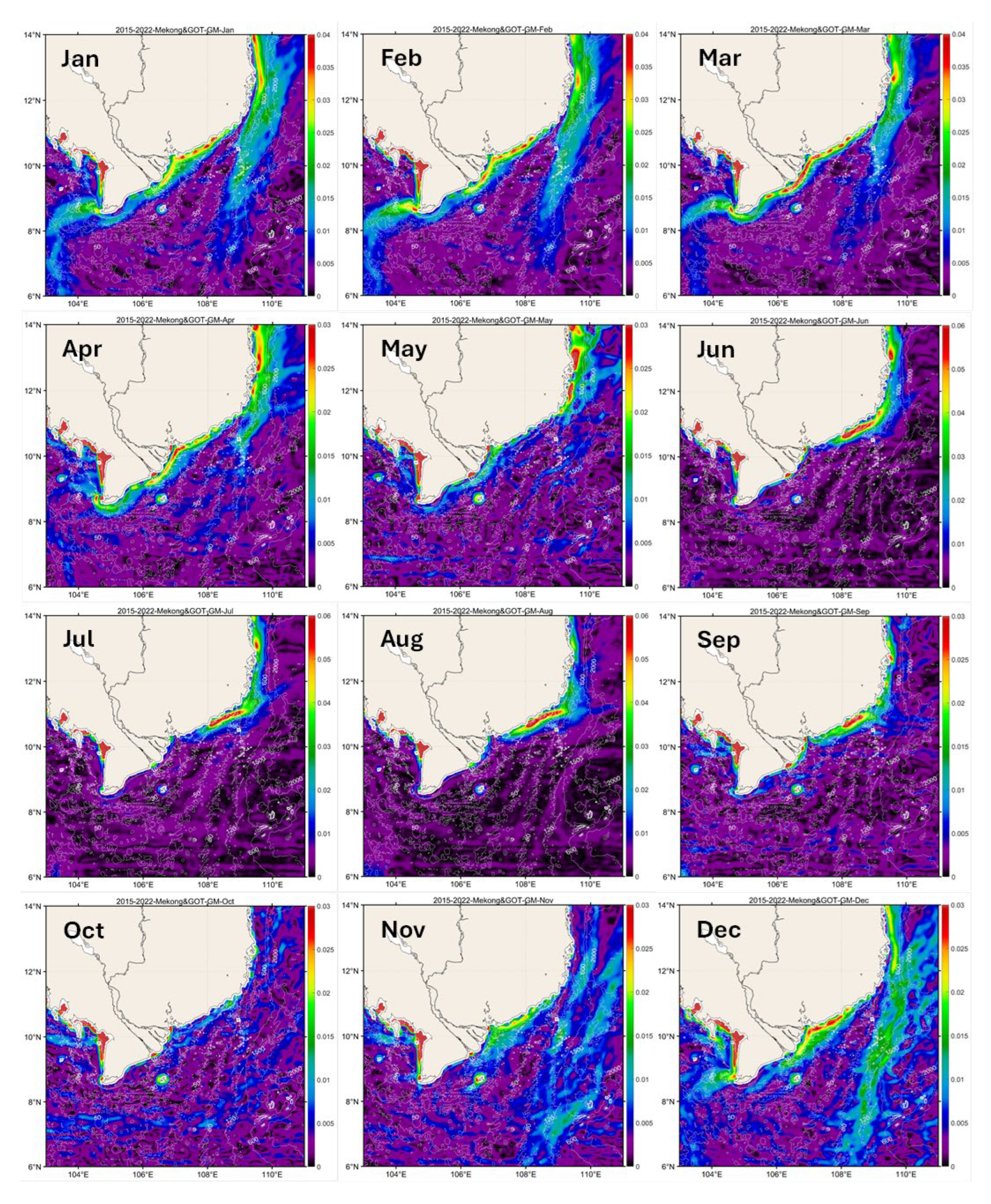

4.7. Region 4: Mekong River Outflow and Gulf of Thailand Entrance

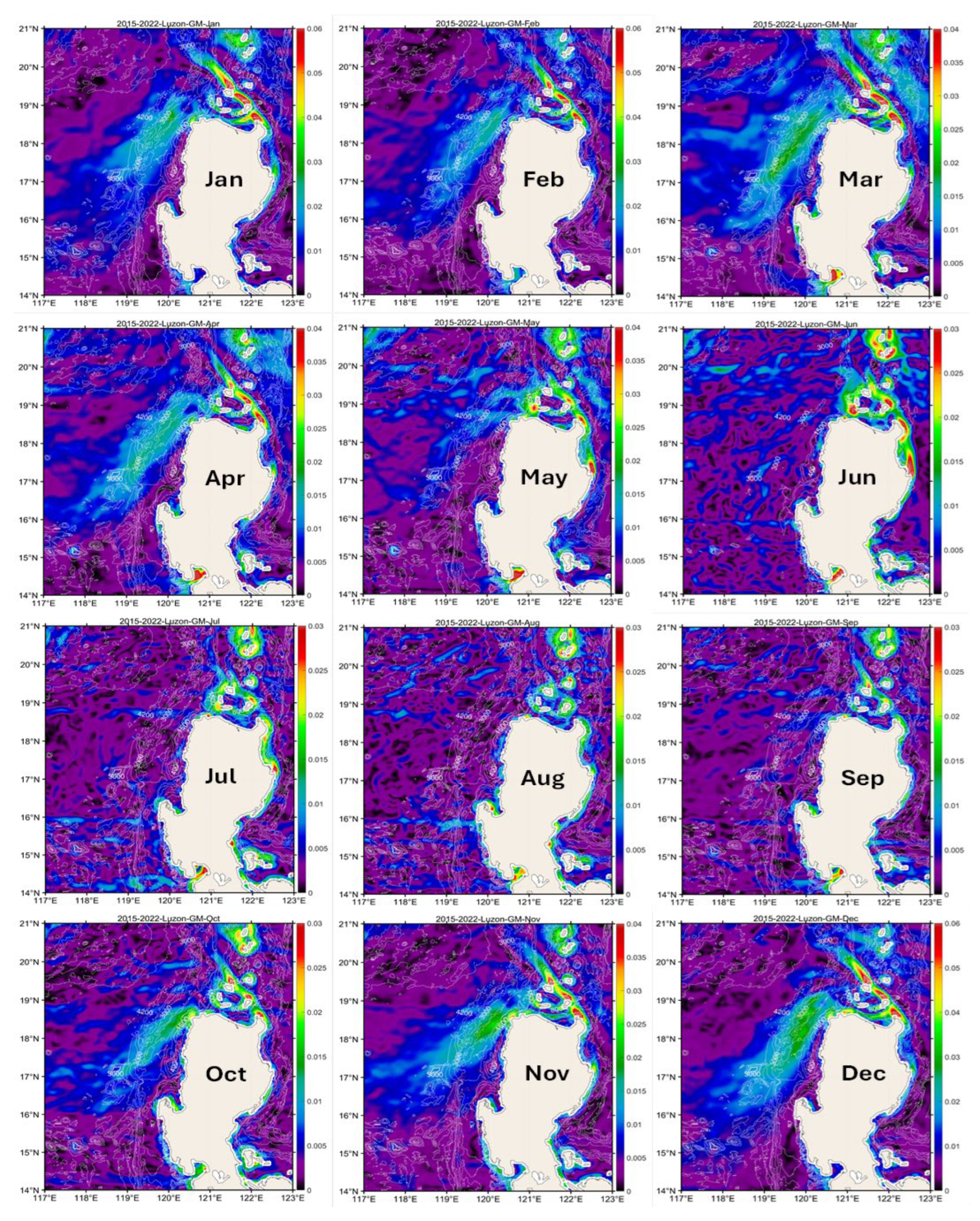

4.8. Region 5: Luzon Strait and West of Luzon

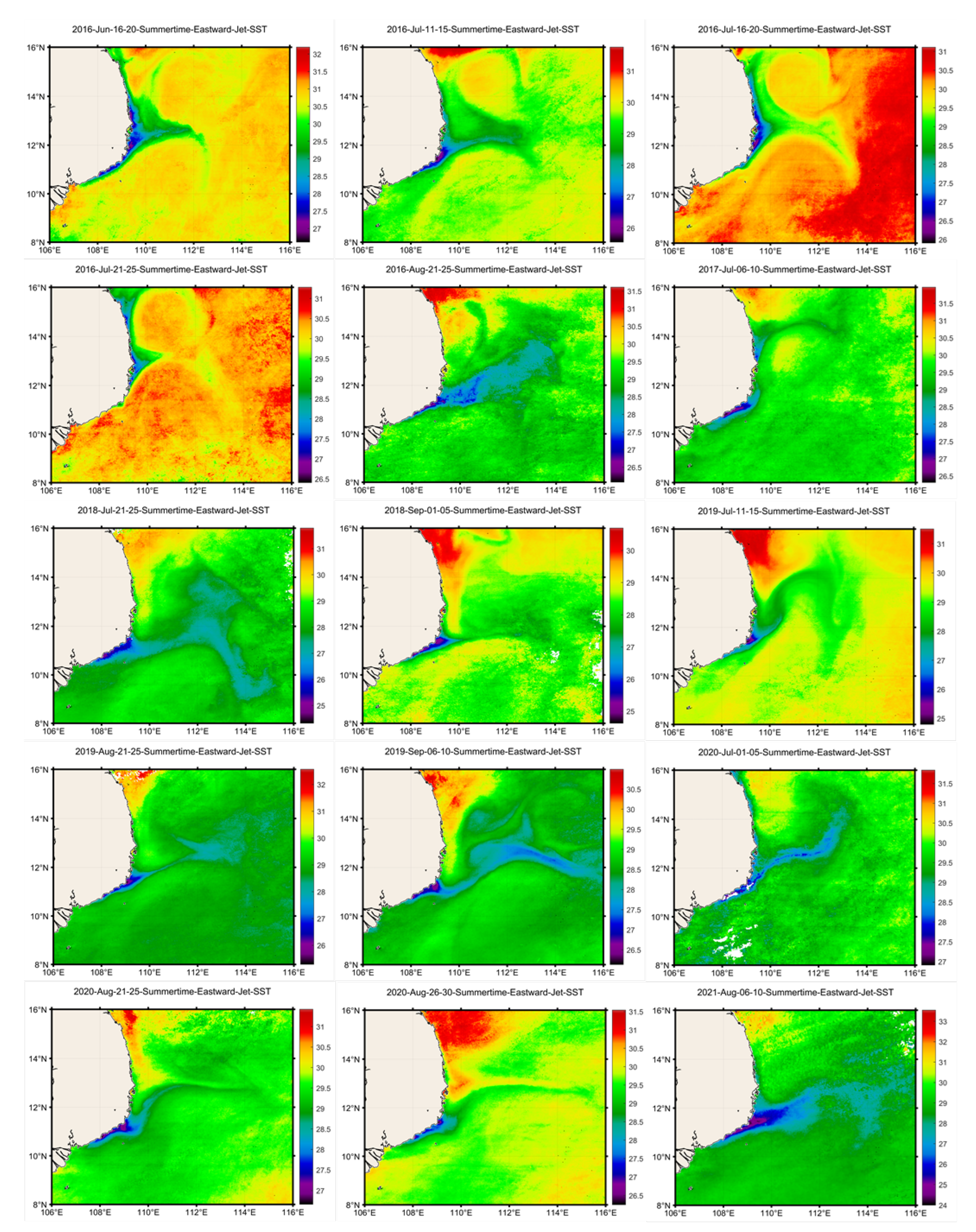

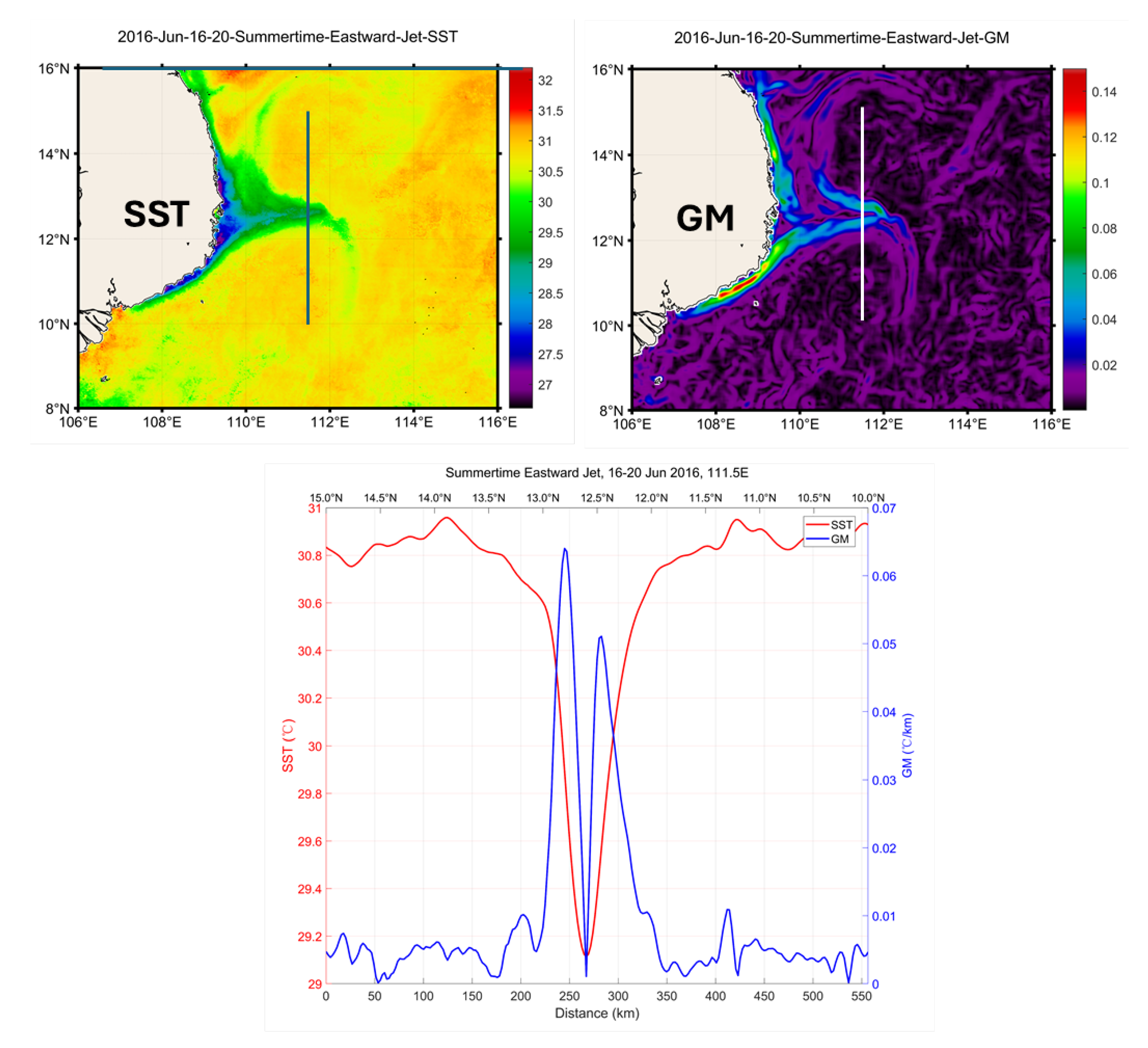

4.9. Summertime Eastward Jet Off SE Vietnam

5. Discussion

5.1. China Coastal Front

5.2. Taiwan Strait and Taiwan Bank

5.3. Eastern Guangdong Shelf

5.4. Pearl River Plume Front

5.5. Western Guangdong Shelf

5.6. Hainan Island

5.7. Beibu Gulf (Gulf of Tonkin)

5.8. Central and SE Vietnam Shelf

5.9. Summertime Eastward Jet Off SE Vietnam

5.10. Mekong Estuary and Shelf

5.11. Gulf of Thailand

5.12. Peninsular Malaysia

5.13. Sunda Shelf

5.14. Borneo Shelf

5.15. West Luzon Front

5.16. Luzon Strait

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akhir MF, Daryabor F, Husain ML, Tangang F, Qiao FL, 2015. Evidence of upwelling along Peninsular Malaysia during southwest monsoon. Open Journal of Marine Science, 5(3), 273-279. [CrossRef]

- Bai P, Yang JL, Xie LL, Zhang SW, Ling Z, 2020. Effect of topography on the cold water region in the east entrance area of Qiongzhou Strait. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 242, Article 106820. [CrossRef]

- Becker JJ, Sandwell DT, Smith WHF, Braud J, Binder B, Depner J, Fabre D, Factor J, Ingalls S, Kim SH, Ladner R, Marks K, Nelson S, Pharaoh A, Trimmer R, Von Rosenberg J, Wallace G, Weatherall P, 2009. Global bathymetry and elevation data at 30 arc seconds resolution: SRTM30_PLUS. Marine Geodesy, 32(4), 355-371. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, 2021. Remote sensing of ocean fronts in marine ecology and fisheries. Remote Sensing, 13(5), Article 883. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Cornillon PC, 2003. SST fronts of the Pacific coastal and marginal seas. Pacific Oceanography, 1(2), 90-113. http://ferhri.ru/images/stories/FERHRI/PacificOceanography/povol1n2.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2024.

- Belkin IM, Cornillon PC, 2007. Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007/D:21, 33 pp. https://www.ices.dk/sites/pub/CM%20Doccuments/CM-2007/D/D2107.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2024.

- Belkin IM, O’Reilly JE, 2009. An algorithm for oceanic front detection in chlorophyll and SST satellite imagery. Journal of Marine Systems, 78(3), 317-326. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Shen XT, 2024. Salinity fronts in the South Atlantic. Remote Sensing, 16(9), Article 1578. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Cornillon PC, Sherman K, 2009. Fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems. Progress in Oceanography, 81(1-4), 223-236. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Lou SS, Yin WB, 2023. The China Coastal Front from Himawari-8 AHI SST Data—Part 1: East China Sea. Remote Sensing, 15(8), Article 2123. [CrossRef]

- Belkin IM, Lou SS, Zang YT, Yin WB, 2024. The China Coastal Front from Himawari-8 AHI SST Data—Part 2: South China Sea. Remote Sensing, 16(18), Article 3415. [CrossRef]

- Bessho K, Date K, Hayashi M, Ikeda A, Imai T, Inoue H, Kumagai Y, Miyakawa T, Murata H, Ohno T, Okuyama A, Oyama R, 2016. An introduction to Himawari-8/9 — Japan’s new-generation geostationary meteorological satellites. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, 94(2), 151-183. [CrossRef]

- Canny J, 1986. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 8(6), 679-698. [CrossRef]

- Caruso MJ, Gawarkiewicz GG, Beardsley RC, 2006. Interannual Variability of the Kuroshio Intrusion in the South China Sea. Journal of Oceanography, 62(4), 559-575. [CrossRef]

- Castelao RM, Wang YT, 2014. Wind-driven variability in sea surface temperature front distribution in the California Current System. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119(3), 1861-1875. [CrossRef]

- Cayula JF, Cornillon P, 1992. Edge detection algorithm for SST images. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 9(1), 67-80. [CrossRef]

- Cayula JF, Cornillon P, 1995. Multi-image edge detection for SST images. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 12(4), 821-829. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Shimada T, Lee MA, Lu HJ, Sakaida F, Kawamura H, 2006. Wintertime sea surface temperature fronts in the Taiwan Strait. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(23), L23603. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Lee MA, Shimada T, Sakaida F, Kawamura H, Chan JW, Lu HJ, 2008. Wintertime high-resolution features of sea surface temperature and chlorophyll-a fields associated with oceanic fronts in the southern East China Sea. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 29(21), 6249-6261. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Shieh WJ, Lee MA, Chan JW, Lan KW, Weng JS, 2010. Fine-scale sea surface temperature fronts in wintertime in the northern South China Sea. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 31(17), 4807-4818. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y, Shih YY, Tsai YC, Lu YH, Liu JT, Hsu TY, Yang JH, Wu XH, Hung CC, 2022. Decreasing trend of Kuroshio intrusion and its effect on the chlorophyll-a concentration in the Luzon Strait, South China Sea. GIScience & Remote Sensing, 59(1), 633-647. [CrossRef]

- Chen CS, Lai ZG, Beardsley RC, Xu QC, Lin HC, Viet NT, 2012. Current separation and upwelling over the southeast shelf of Vietnam in the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 117(C3), Article C03033. [CrossRef]

- Chen JY, Hu ZF, 2023. Seasonal variability in spatial patterns of sea surface cold- and warm fronts over the continental shelf of the northern South China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, Article 1100772. [CrossRef]

- Daryabor F, Ooi SH, Samah AA, Akbari A, 2016. Dynamics of the water circulations in the southern South China Sea and its seasonal transports. PLoS ONE, 11(7), Article e0158415. [CrossRef]

- Daud NR, Akhir MF, Muslim AM, 2019. Dynamic of ENSO towards upwelling and thermal front zone in the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 38(1), 48-60. [CrossRef]

- Deng L, Zhao J, Sun SJ, Ai B, Zhou W, Cao WX, 2024. Two-decade satellite observations reveal variability in size-fractionated phytoplankton primary production in the South China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part I, 206, Article 104258. [CrossRef]

- Dong J, Zhong Y, 2020. Submesoscale fronts observed by satellites over the Northern South China Sea shelf. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans, 91, Article 101161. [CrossRef]

- Dong LX, Su JL, Wong LA, Cao ZY, Chen JC, 2004. Seasonal variation and dynamics of the Pearl River plume. Continental Shelf Research, 24(16), 1761-1777. [CrossRef]

- Fang GH, Fang WD, Fang Y, Wang K, 1998. A survey of studies on the South China Sea upper ocean circulation. Acta Oceanographica Taiwanica, 37(1), 1-16. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Guohong-Fang/research. Accessed 2024-11-24.

- Fang WD, Guo ZX, Huang YT, 1998. Observational study of the circulation in the southern South China Sea. Chinese Science Bulletin, 43(11), 898-905. [CrossRef]

- Fang WD, Fang GH, Shi P, Huang QZ, Xie Q, 2002. Seasonal structures of upper layer circulation in the southern South China Sea from in situ observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 107(C11), Article 3202. [CrossRef]

- Feng YK, Park E, Wang JY, Feng L, Tran DD, 2024. Severe decline in extent and seasonality of the Mekong plume after 2000. Journal of Hydrology, 643, Article 132026. [CrossRef]

- Gan JP, Qu TD, 2008. Coastal jet separation and associated flow variability in the Southwest South China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part I, 55(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Gao JS, Mo LQ, Lu HF, Meng XN, Wu GD, Wang DP, Nguyen KC, Hu BQ, Tran AT, 2024. Spring circulation characteristics and formation mechanism in the Beibu Gulf. Frontiers in Marine Science, 11, Article 1398702. [CrossRef]

- Guo L, Xiu P, Chai F, Xue HJ, Wang DX, Sun J, 2017. Enhanced chlorophyll concentrations induced by Kuroshio intrusion fronts in the northern South China Sea. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(22), 11,565-11,572. [CrossRef]

- Hickox R, Belkin I, Cornillon P, Shan Z, 2000. Climatology and seasonal variability of ocean fronts in the East China, Yellow and Bohai Seas from satellite SST data. Geophysical Research Letters, 27(18), 2945-2948. [CrossRef]

- Hu JY, Kawamura H, Hong HS, Qi YQ, 2000. A review on the currents in the South China Sea: Seasonal circulation, South China Sea warm current and Kuroshio intrusion. Journal of Oceanography, 56(6), 607-624. [CrossRef]

- Hu JY, Kawamura H, Tang DL, 2003. Tidal front around the Hainan Island, northwest of the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 108(C11), Article 3342. [CrossRef]

- Hu JY, Wang XH, 2016. Progress on upwelling studies in the China seas. Review of Geophysics, 54(3), 653-673. [CrossRef]

- Hu JY, San Liang X, Lin HY, 2018. Coastal upwelling off the China coasts. In: X. San Liang and Yuanzhi Zhang (editors), Coastal Environment, Disaster, and Infrastructure: A Case Study of China’s Coastline, IntechOpen, London, UK, pp. 3-25. [CrossRef]

- Hu ZF, Xie GH, Zhao J, Lei YP, Xie JC, Pang WH, 2022. Mapping diurnal variability of the wintertime Pearl River plume front from Himawari-8 geostationary satellite observations. Water, 14(1), Article 43. [CrossRef]

- Huang TH, Chen CTA, Bai Y, He XQ, 2020. Elevated primary productivity triggered by mixing in the quasi-cul-de-sac Taiwan Strait during the NE monsoon. Scientific Reports, 10(1), Article 7846. [CrossRef]

- Huang XL, Jing ZY, Zheng RX, Cao HJ, 2020. Dynamical analysis of submesoscale fronts associated with wind-forced offshore jet in the western South China Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 39(11), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Jing ZY, Qi YQ, Du Y, Zhang SW, Xie LL, 2015. Summer upwelling and thermal fronts in the northwestern South China Sea: Observational analysis of two mesoscale mapping surveys. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(3), 1993-2006. [CrossRef]

- Jing ZY, Qi YQ, Fox-Kemper B, Du Y, Lian SM, 2016. Seasonal thermal fronts on the northern South China Sea shelf: Satellite measurements and three repeated field surveys. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(3), 1914-1930. [CrossRef]

- Kok PH, Akhir MF, Tangang FT, 2015. Thermal frontal zone along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Continental Shelf Research, 110, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Kok PH, Akhir MFM, Tangang F, Husain ML, 2017. Spatiotemporal trends in the southwest monsoon wind-driven upwelling in the southwestern part of the South China Sea. PLoS ONE, 12(2), Article e0171979. [CrossRef]

- Kok PH, Akhir MF, Qiao FL, 2019. Distinctive characteristics of upwelling along the Peninsular Malaysia’s east coast during 2009/10 and 2015/16 El Niños. Continental Shelf Research, 184, 10-20. [CrossRef]

- Kok PH, Wijeratne S, Akhir MF, Pattiaratchi C, Chung JX, Roseli NH, Daud NR, 2022. Modeling approaches in the investigation of upwelling along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia: Its driven mechanisms. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 55, Article 102562. [CrossRef]

- Lan KW, Kawamura H, Lee MA, Chang Y, Chan JW, Liao CH, 2009. Summertime sea surface temperature fronts associated with upwelling around the Taiwan Bank. Continental Shelf Research, 29(7), 903-910. [CrossRef]

- Lao QB, Zhang SW, Li ZY, Chen FJ, Zhou X, Jin GZ, Huang P, Deng ZY, Chen CQ, Zhu QM, Lu X, 2022. Quantification of the seasonal intrusion of water masses and their impact on nutrients in the Beibu Gulf using dual water isotopes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 127(7), Article e2021JC018065. [CrossRef]

- Lao QB, Liu SH, Wang C, Chen FJ, 2023. Global warming weakens the ocean front and phytoplankton blooms in the Luzon Strait over the past 40 years. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 128(12), Article e2023JG007726. [CrossRef]

- Le PTD, Fischer AM, 2021. Trends and patterns of SST and associated frontal frequency in the Vietnamese upwelling center. Journal of Marine Systems, 222, Article 103600. [CrossRef]

- Lee MA, Chang Y, Shimada T, 2015. Seasonal evolution of fine-scale sea surface temperature fronts in the East China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part II, 119, 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Li JY, Li M, Wang C, Zheng QA, Xu Y, Zhang TY, Xie LL, 2023. Multiple mechanisms for chlorophyll a concentration variations in coastal upwelling regions: a case study east of Hainan Island in the South China Sea. Ocean Science, 19(2), 469-484. [CrossRef]

- Li YL, Han WQ, Wilkin JL, Zhang WFG, Arango H, Zavala-Garay J, Levin J, Castruccio FS, 2014. Interannual variability of the surface summertime eastward jet in the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 119(10), 7205-7228. [CrossRef]

- Li YN, Curchitser EN, Wang J, Peng SQ, 2020. Tidal effects on the surface water cooling northeast of Hainan Island, South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125(10), Article e2019JC016016. [CrossRef]

- Lin HY, Hu JY, Liu ZY, Belkin IM, Sun ZY, Zhu J, 2017. A peculiar lens-shaped structure observed in the South China Sea. Scientific Reports, 7(1), Article number 478. [CrossRef]

- Lin HY, Sun ZY, Chen ZZ, Zhu J, JY Hu, 2020. Wintertime Guangdong coastal currents successfully captured by cheap GPS drifters. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 39(1), 166-170. [CrossRef]

- Lin PG, Cheng P, Gan JP, Hu JY, 2016. Dynamics of wind-driven upwelling off the northeastern coast of Hainan Island. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(2), 1160-1173. [CrossRef]

- Liu JP, DeMaster DJ, Nittrouer CA, Eidam EF, Nguyen TT, 2017. A seismic study of the Mekong subaqueous delta: Proximal versus distal sediment accumulation. Continental Shelf Research, 147, 197-212. [CrossRef]

- Liu QY, Jiang X, Xie SP, Liu WT, 2004. A gap in the Indo-Pacific warm pool over the South China Sea in boreal winter: Seasonal development and interannual variability. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 109(C7), Article C07012. [CrossRef]

- Liu ZZ, Fagherazzi S, Liu XH, Shao DD, Miao CY, Cai YZ, Hou CY, Liu YL, Li Xia, Cui BS, 2022. Long-term variations in water discharge and sediment load of the Pearl River Estuary: Implications for sustainable development of the Greater Bay Area. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, Article 983517. [CrossRef]

- Loisel H, Mangin A, Vantrepotte V, Dessailly D, Dinh DN, Garnesson P, Ouillon S, Lefebvre JP, Mériaux X, Phan TM, 2014. Variability of suspended particulate matter concentration in coastal waters under the Mekong’s influence from ocean color (MERIS) remote sensing over the last decade. Remote Sensing of Environment, 150, 218-230. [CrossRef]

- Lü XG, Qiao FL, Wang GS, Xia CS, Yuan YL, 2008. Upwelling off the west coast of Hainan Island in summer: Its detection and mechanisms. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(2), Article L02604. [CrossRef]

- Ma XC, He YW, Gao M, Gong T, 2024. The morphology and formation of a binary sand ridge in the Beibu Gulf, northwestern South China Sea. Geomorphology, 458, Article 109251. [CrossRef]

- Ngo MH, Hsin YC, 2024. Three-dimensional structure of temperature, salinity, and velocity of the summertime Vietnamese upwelling system in the South China Sea on the interannual timescale. Progress in Oceanography, 229, Article 103354. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen QH, Tran VN, 2024. Temporal changes in water and sediment discharges: impacts of climate change and human activities in the Red River basin (1958–2021) with projections up to 2100. Water, 16, Article 1155. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Duy T, Ayoub NK, Marsaleix P, Toublanc F, De Mey-Frémaux P, Piton V, Herrmann M, Duhaut T, Tran MC, Ngo-Duc T, 2021. Variability of the Red River plume in the Gulf of Tonkin as revealed by numerical modeling and clustering analysis. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8, Article 772139. [CrossRef]

- Ou SY, Zhang H, Wang DX, 2009. Dynamics of the buoyant plume off the Pearl River Estuary in summer. Environmental Fluid Mechanics, 9(5), 471-492. [CrossRef]

- Pi QL, Hu JY, 2010. Analysis of sea surface temperature fronts in the Taiwan Strait and its adjacent area using an advanced edge detection method. Science China Earth Sciences, 53 (7), 1008-1016. [CrossRef]

- Ping B, Su FZ, Meng YS, Du YY, Fang SH, 2016. Application of a sea surface temperature front composite algorithm in the Bohai, Yellow, and East China Seas. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 34 (3), 597-607. [CrossRef]

- Piton V, Herrmann M, Marsaleix P, Duhaut T, Ngoc TB, Tran MC, Shearman K, Ouillon S, 2021. Influence of winds, geostrophy and typhoons on the seasonal variability of the circulation in the Gulf of Tonkin: A high-resolution 3D regional modeling study. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 45, Article 101849. [CrossRef]

- Pokavanich T, Worrawatanathum V, Phattananuruch K, Koolkalya S, 2024. Seasonal dynamics and three-dimensional hydrographic features of the eastern Gulf of Thailand: Insights from high-resolution modeling and field measurements. Water, 16(14), Article 1962. [CrossRef]

- Qiu CH, Cui YS, Hu SQ, Huo D, 2017. Seasonal variation of Guangdong coastal thermal front based on merged satellite data. Journal of Tropical Oceanology, 36(5), 16-23 (in Chinese, with English abstract and captions). [CrossRef]

- Qiu Y, Li L, Chen CTA, Guo XG, Jing CS, 2011. Currents in the Taiwan Strait as observed by surface drifters. Journal of Oceanography, 67(4), 395-404. [CrossRef]

- Qu TD, 2001. Role of ocean dynamics in determining the mean seasonal cycle of the South China Sea surface temperature. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 106(C4), 6943-6955. [CrossRef]

- Ren SH, Zhu XM, Drevillon A, Wang H, Zhang YF, Zu ZQ, Li A, 2021. Detection of SST fronts from a high-resolution model and its preliminary results in the South China Sea. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 38(2), 387-403. [CrossRef]

- Robinson MK, 1974. The physical oceanography of the Gulf of Thailand, Naga Expedition. Naga Report, Volume 3, Part 1. The University of California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mf3d0b7. Accessed 2024-12-08.

- Roseli NH, Akhir MF, Husain ML, Tangang F, Ali A, 2015. Water mass characteristics and stratification at the shallow Sunda Shelf of southern South China Sea. Open Journal of Marine Science, 5(4), 455-467. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barradas A, Nigam S, 2024. Hydroclimate variability and change over the Mekong River Basin. In: Hong Quan Nguyen, Heiko Apel, Quang Bao Le, Minh Tú Nguyễn, and Venkataramana Sridhar (editors), The Mekong River Basin, Chapter 1, pp. 3-52. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Shaw PT, Chao SY, 1994. Surface circulation in the South China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part I, 41(11-12), 1663-1683. [CrossRef]

- Shen XT, Belkin IM, 2023. Observational studies of ocean fronts: A systematic review of Chinese-language literature. Water, 15(20), Article 3649. [CrossRef]

- Shi MC, Chen CS, Xu QC, Lin HC, Liu GM, Wang H, Wang F, Yan JH, 2002. The role of Qiongzhou Strait in the seasonal variation of the South China Sea circulation. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 32(1), 103-121. [CrossRef]

- Shi R, Guo XY, Wang DX, Zeng LL, Chen J, 2015. Seasonal variability in coastal fronts and its influence on sea surface wind in the Northern South China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part II, 119, 30-39. [CrossRef]

- Shi R, Chen J, Guo XY, Zeng LL, Li J, Xie Q, Wang X, Wang DX, 2017. Ship observations and numerical simulation of the marine atmospheric boundary layer over the spring oceanic front in the northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 122(7), 3733-3753. [CrossRef]

- Shi R, Guo XY, Chen J, Zeng LL, Wu B, Wang DX, 2022. Effects of spatial scale modification on the responses of surface wind stress to the thermal front in the northern South China Sea. Journal of Climate, 35(1), 179-194. [CrossRef]

- Shi WA, Huang Z, Hu JY, 2021. Using TPI to map spatial and temporal variations of significant coastal upwelling in the northern South China Sea. Remote Sensing, 13, Article 1065. [CrossRef]

- Shimada T, Sakaida F, Kawamura H, Okumura T, 2005. Application of an edge detection method to satellite images for distinguishing sea surface temperature fronts near the Japanese coast. Remote Sensing of Environment, 98(1), 21-34. [CrossRef]

- Shu YQ, Wang Q, Zu TT, 2018. Progress on shelf and slope circulation in the northern South China Sea. Science China (Earth Sciences), 61(5), 560-571. [CrossRef]

- Su JL, 2004. Overview of the South China Sea circulation and its influence on the coastal physical oceanography outside the Pearl River Estuary. Continental Shelf Research, 24(16), 1745-1760. [CrossRef]

- Sun RL, Ling Z, Chen CL, Yan YW, 2015. Interannual variability of thermal front west of Luzon Island in boreal winter. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 34(11), 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Sun RL, Li PL, Gu YZ, Zhou CJ, Liu C, Zhang L, 2023. Seasonal variation of the shape and location of the Luzon cold eddy. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 42(5), 14-24. [CrossRef]

- Sun RL, Li PL, Zhai FG, Gu YZ, Bai P, 2024. New insight into the formation mechanism of wintertime thermal front west of Luzon Island. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 129(6), Article e2023JC020774. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Lan JA, 2021. Summertime eastward jet and its relationship with western boundary current in the South China Sea on the interannual scale. Climate Dynamics, 56(3-4), 935-947. [CrossRef]

- Tan HJ, Cai RS, Wu RG, 2022. Summer marine heatwaves in the South China Sea: Trend, variability and possible causes. Advances in Climate Change Research, 13(3), 323-332. [CrossRef]

- Tan KY, Xie LL, Li MM, Li M, Li JY, 2023. 3D structure and seasonal variation of temperature fronts in the shelf sea west of Guangdong. Haiyang Xuebao (Acta Oceanologica Sinica Chinese Edition), 45(10), 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Tong JQ, Gan ZJ, Qi YQ, Mao QW, 2010. Predicted positions of tidal fronts in continental shelf of South China Sea. Journal of Marine Systems, 82(3), 145-153. [CrossRef]

- Ullman DS, Cornillon PC, 1999. Satellite-derived sea surface temperature fronts on the continental shelf off the northeast U.S. coast. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 104(C10), 23459-23478. [CrossRef]

- Ullman DS, Cornillon PC, 2001. Continental shelf surface thermal fronts in winter off the northeast US coast. Continental Shelf Research, 21(11-12), 1139-1156. [CrossRef]

- Unverricht D, Nguyen TC, Heinrich C, Szczuciński W, Lahajnar N, Stattegger K, 2014. Suspended sediment dynamics during the inter-monsoon season in the subaqueous Mekong Delta and adjacent shelf, southern Vietnam. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 79, 509-519. [CrossRef]

- van Maren DS, 2007. Water and sediment dynamics in the Red River mouth and adjacent coastal zone. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 29(4), 508-522. [CrossRef]

- Varikoden H, Samah AA, Babu CA, 2010. The cold tongue in the South China Sea during boreal winter and its interaction with the atmosphere. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 27(2), 265-273. [CrossRef]

- Wang DX, Liu Y, Qi YQ, Shi P, 2001. Seasonal variability of thermal fronts in the Northern South China Sea from satellite data. Geophysical Research Letters, 28(20), 3963-3966. [CrossRef]

- Wang DX, Luo L, Liu Y, Li SY, 2003. Seasonal and interannual variability of thermal fronts in the Tonkin Gulf. In: Ocean Remote Sensing and Applications (SPIE Proceedings, Vol. 4892), pp. 415-425. SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Wang DX, Liu QY, Xie Q, He ZG, Zhuang W, Shu YQ, Xiao XJ, Hong B, Wu XY, Sui DD, 2013. Progress of regional oceanography study associated with western boundary current in the South China Sea. Chinese Science Bulletin, 58(11), 1205-1215. [CrossRef]

- Wang GH, Chen D, Su JL, 2006. Generation and life cycle of the dipole in the South China Sea summer circulation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 111(C6), Article C06002. [CrossRef]

- Wang GH, Li JX, Wang CZ, Yan YW, 2012. Interactions among the winter monsoon, ocean eddy and ocean thermal front in the South China Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 117(C8), Article C08002. [CrossRef]

- Wang TH, Sun Y, Su H, Lu WF, 2023. Declined trends of chlorophyll a in the South China Sea over 2005−2019 from remote sensing reconstruction. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 42(1), 12-24. [CrossRef]

- Wang TH, Sun Y, Su H, Lu WF, 2023. Declined trends of chlorophyll a in the South China Sea over 2005−2019 from remote sensing reconstruction. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 42(1), 12-24. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang WY, Xie XO, Chen H, Chen BC, 2024. Holocene sedimentary distribution and morphological characteristics reworked by East Asian monsoon dynamics in the Mekong River shelf, South Vietnam. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 302, Article 108784. [CrossRef]

- Wang YC, Chen WY, Chang Y, Lee MA, 2013. Ichthyoplankton community associated with oceanic fronts in early winter on the continental shelf of the southern East China Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 21 (Suppl.), 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Wang YC, Chan JW, Lan YC, Yang WC, Lee MA, 2018. Satellite observation of the winter variation of sea surface temperature fronts in relation to the spatial distribution of ichthyoplankton in the continental shelf of the southern East China Sea. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 39(13), 4550-4564. [CrossRef]

- Wang YT, Castelao RM, Yuan YP, 2015. Seasonal variability of alongshore winds and sea surface temperature fronts in Eastern Boundary Current Systems. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 120(3), 2385-2400. [CrossRef]

- Wang YT, Yu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang HR, Chai F, 2020. Distribution and variability of sea surface temperature fronts in the South China Sea. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 240, 106793. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Lin HY, Hu JY, 2020. Oceanic fronts in the Northern South China Sea. In: Jianyu Hu, Chung-Ru Ho, Lingling Xie, and Quanan Zheng (editors), Regional Oceanography of the South China Sea, World Scientific Publishing, Singapore, pp. 379-402. [CrossRef]

- Wyrtki K, 1961. Scientific Results of Marine Investigations of the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand 1959-1961. Naga Report, Volume 2, 195 pp. The University of California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/49n9x3t4. Accessed 2024-11-14.

- Xie LL, Pallas-Sanz E, Zheng QA, Zhang SW, Zong XL, Yi XF, Li MM (2017). Diagnosis of 3D vertical circulation in the upwelling and frontal zones east of Hainan Island, China. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 47(4), 755-774. [CrossRef]

- Xie SP, Xie Q, Wang DX, Liu WT, 2003. Summer upwelling in the South China Sea and its role in regional climate variations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 108(C8), Article 3261. [CrossRef]

- Xing QW, Yu HQ, Wang H, Ito SI, 2023. An improved algorithm for detecting mesoscale ocean fronts from satellite observations: Detailed mapping of persistent fronts around the China Seas and their long-term trends. Remote Sensing of Environment, 294, Article 113627. [CrossRef]

- Xing QW, Yu HQ, Wang H, 2024. Global mapping and evolution of persistent fronts in Large Marine Ecosystems over the past 40 years. Nature Communications, 15(1), Article 4090. [CrossRef]

- Yanagi T, Takao T, 1998. Seasonal variation of three-dimensional circulations in the Gulf of Thailand. La Mer, 36(2), 43-55.

- Yang CY, Ye HB, 2021. The features of the coastal fronts in the Eastern Guangdong coastal waters during the downwelling-favorable wind period. Scientific Reports, 11, Article 10238. [CrossRef]

- Yang LQ, Huang ZD, Sun ZY, Hu JY, 2021. Surface currents along the coast of the Chinese Mainland observed by coastal drifters in autumn and winter. Marine Technology Society Journal, 55(5), 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Yang LQ, Sun ZY, Hu ZY, Huang ZD, Chen ZZ, Zhu J, Hu JY, 2023. Surface currents along the coast of the Chinese Mainland observed by coastal drifters during April-May 2019. Marine Technology Society Journal, 57(1), 156-167. [CrossRef]

- Yao JL, Belkin IM, Chen J, Wang DX, 2012. Thermal fronts of the southern South China Sea from satellite and in situ data. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 33(23), 7458-7468. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Zhang HR, Jin JB, Wang YT, 2019. Trends of sea surface temperature and sea surface temperature fronts in the South China Sea during 2003–2017. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 38(4), 106-115. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Wang YT, Cao L, Tang R, Chai F, 2020. The ocean-atmosphere interaction over a summer upwelling system in the South China Sea. Journal of Marine Systems, 208, Article 103360. [CrossRef]

- Yu ZT, Fan YL, Metzger EJ, 2023. On the anomalous structure of the Southeast Vietnam Offshore Current during 1994 to 2015. Ocean Modelling, 183, Article 102199. [CrossRef]

- Zeng XZ, Belkin IM, Peng SQ, Li YN, 2014. East Hainan upwelling fronts detected by remote sensing and modelled in summer. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 35(11-12), 4441-4451. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Li XF, Hu JY, Sun ZY, Zhu J, Chen ZZ, 2014. Summertime sea surface temperature and salinity fronts in the southern Taiwan Strait. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 35(11-12), 4452-4466. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Dong J, 2021. Dynamic characteristics of a submesoscale front and associated heat fluxes over the northeastern South China Sea shelf. Atmosphere-Ocean, 59(3), 190-200. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Sun RL, Li PL, Ye GQ, 2024. Seasonal and interannual variabilities of the thermal front east of Gulf of Thailand. Frontiers in Marine Science, 11, Article 1398791. [CrossRef]

- Zhang SR, Lu XX, Higgitt DL, Chen CTA, Han JT, Sun HG, 2008. Recent changes of water discharge and sediment load in the Zhujiang (Pearl River) basin, China. Global and Planetary Change, 60(3-4), 365-380. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Zeng LL, Wang Q, Geng BX, Liu CJ, Shi R, Liu N, Wang WP, Wang DX, 2021. Seasonal variation in the three-dimensional structures of coastal thermal front off western Guangdong. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 40(7), 88-99. [CrossRef]

- Zhao LH, Yang DT, Zhong R, Yin XQ, 2022. Interannual, seasonal, and monthly variability of sea surface temperature fronts in offshore China from 1982–2021. Remote Sensing, 14(21), Article 5336. [CrossRef]

- Zhi HH, Wu H, Wu JX, Zhang WX, Wang YH, 2022. River plume rooted on the sea-floor: Seasonal and spring-neap variability of the Pearl River plume front. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, Article 791948. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Zhang SW, Liu SH, Chen CQ, Lao QB, Chen FJ, 2024. Thermal fronts in coastal waters regulate phytoplankton blooms via acting as barriers: A case study from western Guangdong, China. Journal of Hydrology, 636, Article 131350. [CrossRef]

- Zhu JY, Zhou QY, Zhou QQ, Geng XX, Shi J, Guo XY, Yu Y, Yang ZW, Fan RF, 2023. Interannual variation of coastal upwelling around Hainan Island. Frontiers in Marine Science, 10, Article 1054669. [CrossRef]

- Zhu XM, Wang H, Liu GM, Régnier C, Kuang XD, Wang DK, Ren SH, Jing ZY, Drévillon M, 2016. Comparison and validation of global and regional ocean forecasting systems for the South China Sea. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 16(7), 1639-1655. [CrossRef]

- Zu TT, Gan JP, Erofeeva SY, 2008. Numerical study of the tide and tidal dynamics in the South China Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part I, 55(2), 137-154. [CrossRef]

- Zu TT, Wang DX, Gan JP, Guan WB, 2014. On the role of wind and tide in generating variability of Pearl River plume during summer in a coupled wide estuary and shelf system. Journal of Marine Systems, 136(1), 65-79. [CrossRef]

- Zu TT, Gan JP, 2015. A numerical study of coupled estuary–shelf circulation around the Pearl River Estuary during summer: Responses to variable winds, tides and river discharge. Deep-Sea Research Part II 117, 53-64. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Data | Period | Algorithm | Region |

| Belkin and Cornillon 2003 | AVHRR | 1985-1996 | CCA1992 | SCS |

| Belkin and Cornillon 2007 | AVHRR | 1985-1996 | CCA1992 | SCS |

| Belkin et al. 2009 | AVHRR | 1985-1996 | CCA1992 | SCS |

| Belkin and Zang (this study) | AHI | 2015-2022 | BOA2009 | SCS |

| Chang Y et al. 2006 | AVHRR | 1996-2005 | S2005 | TS |

| Chang Y et al. 2008 | AVHRR | 1996-2005 | S2005 | TS |

| Chang Y et al. 2010 | AVHRR | 2001-2007 | S2005 | NSCS |

| Chang Y et al., 2022 | OSTIA | 1985-2017 | BOA2009 | Luzon Strait |

| Chen JY and Hu ZF 2023 | GHRSST | 2002-2021 | S2005 | NSCS |

| Dong and Zhong 2020 | AVHRR MODIS |

2009-2012 | GM | NSCS |

| Guo L et al. 2017 | G1SST | 2003-2013 | BOA2009 | NW of Luzon Island |

| Hu JY et al. 2003 | AVHRR | 1997-2003 | NA | Hainan I.; Beibu Gulf |

| Jing ZY et al. 2015 | OSTIA | 2006-2013 | GM | NSCS |

| Jing ZY et al. 2016 | GHRSST | 2006-2014 | GM | NSCS |

| Lan KW et al. 2009 | AVHRR | 1996-2005 | S2005 | TS |

| Lao QB et al. 2023 | OSTIA | 1982-2021 | BOA2009 | Luzon Strait |

| Lee MA et al. 2015 | AVHRR | 1996-2009 | S2005 | TS |

| Pi and Hu 2010 | Misc.* | 2002-2008 | PH2010 | NSCS |

| Ping et al. 2016 | MODIS | 2000-2013 | CCA1992 | TS |

| Ren et al. 2021 | Model | 2005-2018 | Canny (1986) | SCS |

| Shi R et al. 2015 | OSTIA | 2006-2011 | GM | NSCS |

| Sun RL et al. 2015 | OISST | 1993-2013 | GM | West of Luzon Island |

| Sun RL et al. 2024 | OISST | 1993-2022 | GM | West of Luzon Island |

| Wang DX et al. 2001 | AVHRR | 1991-1998 | GM | NSCS |

| Wang DX et al. 2003 | AVHRR | 1991-1998 | GM | Beibu Gulf |

| Wang TH et al. 2023 | GHRSST | 2005-2019 | BOA2009 | SCS |

| Wang YC et al. 2013 | AVHRR | 2006-2009 | S2005 | TS |

| Wang YC et al. 2018 | AVHRR | 2005-2015 | S2005 | TS |

| Wang YT et al. 2020 | MODIS | 2002-2017 | W2020 | NSCS |

| Xing QW et al. 2023 | AVHRR | 1982-2021 | CCA1992 | China Seas |

| Yang CY and Ye HB 2021 | MODIS | 2003-2017 | NA | NSCS |

| Yu Y et al. 2019 | MODIS | 2002-2017 | GM | SCS |

| Zeng XZ et al. 2014 | MODIS | 2002-2011 | BOA2009 | East Hainan |

| Zhang L et al. 2024 | OISST | 1982-2021 | GM | Gulf of Thailand |

| Zhang L and Dong J 2021 | MODIS | 2016-2017 | GM | NSCS |

| Zhang Y et al. 2021 | OSTIA | 2006-2015 | GM | NSCS |

| Zhao LH et al. 2022 | OISST | 1982-2021 | CCA1992 | China Seas |

| Zhou X et al. 2024 | OSTIA | 1982-2022 | GM | West Guangdong |

| Region |

May SST (°C) |

June SST (°C) |

July SST (°C) |

Cooling magnitude (July SST – May SST) |

| West of Luzon | 30.7093 | 30.3820 | 30.0098 | 0.70 |

| Central SCS | 30.5234 | 29.9536 | 29.4660 | 1.07 |

| Gulf of Thailand | 30.6651 | 29.8138 | 29.5900 | 1.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).