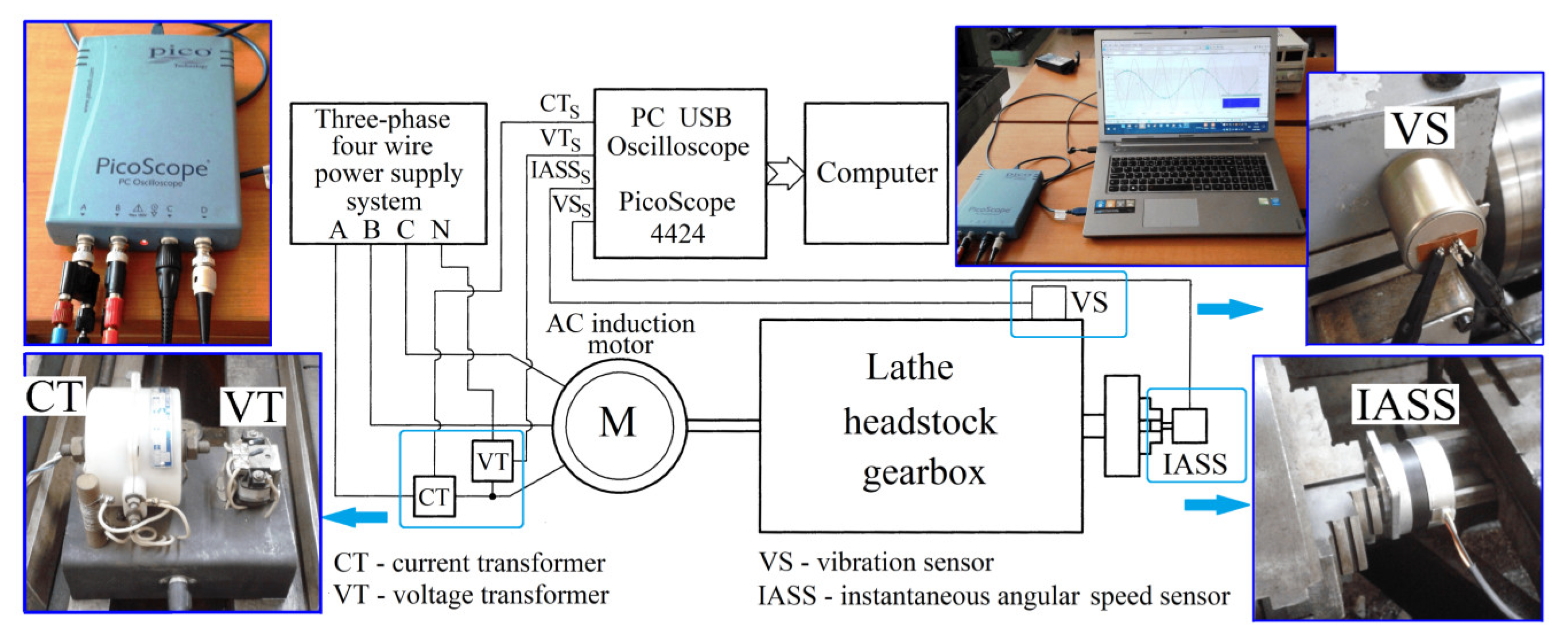

An experimental setup already described in detail in [

3] is used here (

Figure 10 and

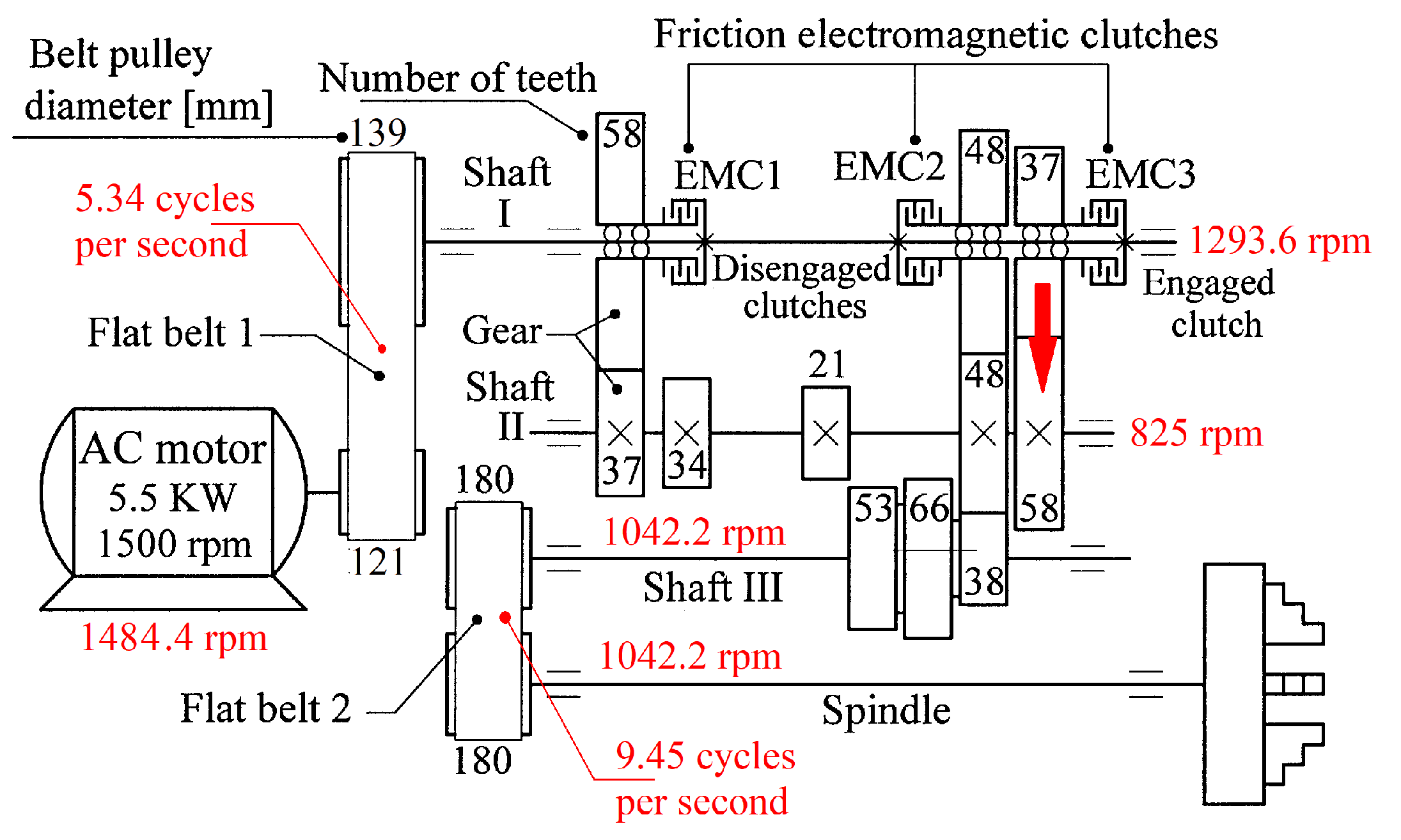

Figure 11). As an electrically driven mechanical system (with a three-phase AC asynchronous motor), a lathe gearbox is used (with the kinematic scheme partially shown in

Figure 11). In this approach, some different signals provided by appropriate sensors are useful for condition monitoring purposes during a steady state regime (at idle) of the lathe gearbox: the active electrical power (

Pa) absorbed by the driving motor, the vibration signal (

Vs) and the instantaneous angular speed (IAS) as signal

Ias. The active electric power

Pa is mathematically defined [

3] based on the signals supplied by a voltage transformer (VT) and a current transformer (CT). The vibration signal

Vs is provided by a vibration sensor (VS) [

3]. The signal

Ias involved in the description of the instantaneous angular speed (IAS) of the spindle is provided by an IAS sensor IASS placed in the jaw chuck of the spindle [

3]. All signals are sampled using a numerical oscilloscope [

3] connected to a computer. The signal processing was done in Matlab.

3.1. Some Results Obtained by Analyzing the Variable Part of the Active Electrical Power Signal Using AMSSRTI

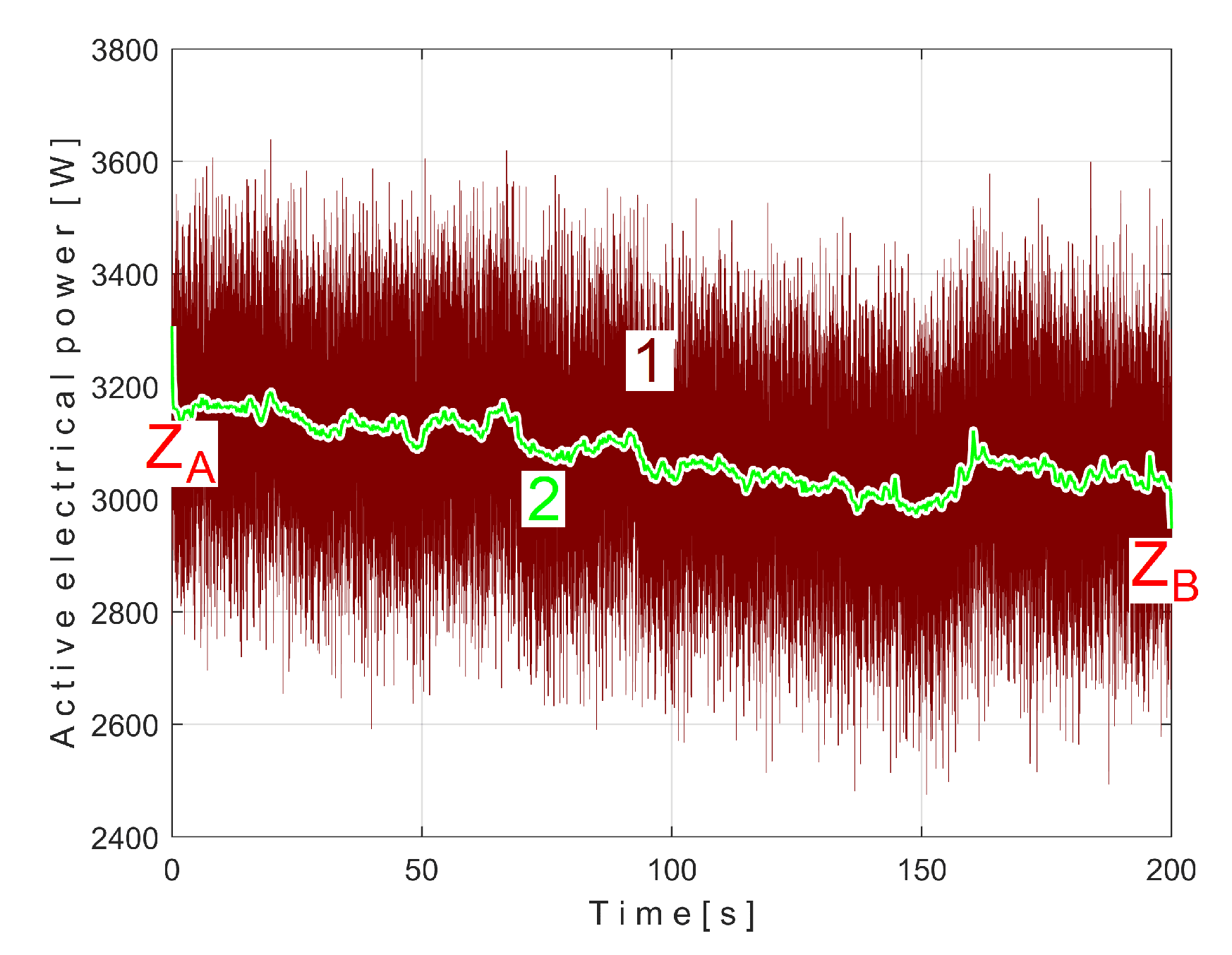

Figure 12 shows the time-domain representation of

Pa (curve 1), a long sequence of 200 s (with

pa = 5,000,000 samples,

Δt = 1/25,000 s, 12 bit resolution). To produce

Pav signal (as

sP signal) the constant and the very low frequency variable part of

Pa were mathematically subtracted from

Pa. This very low frequency variable part (curve 2) was obtained by low pass filtering of

Pa (using numerical multiple moving average filters [

54]). Since this filtering produces false values at the beginning and end of the filtered sequence (zones Z

A and Z

B in

Figure 12), these zones are removed from

Pav (so

Pav is shorter than

Pa, as having just

pav = 4,984,501 samples).

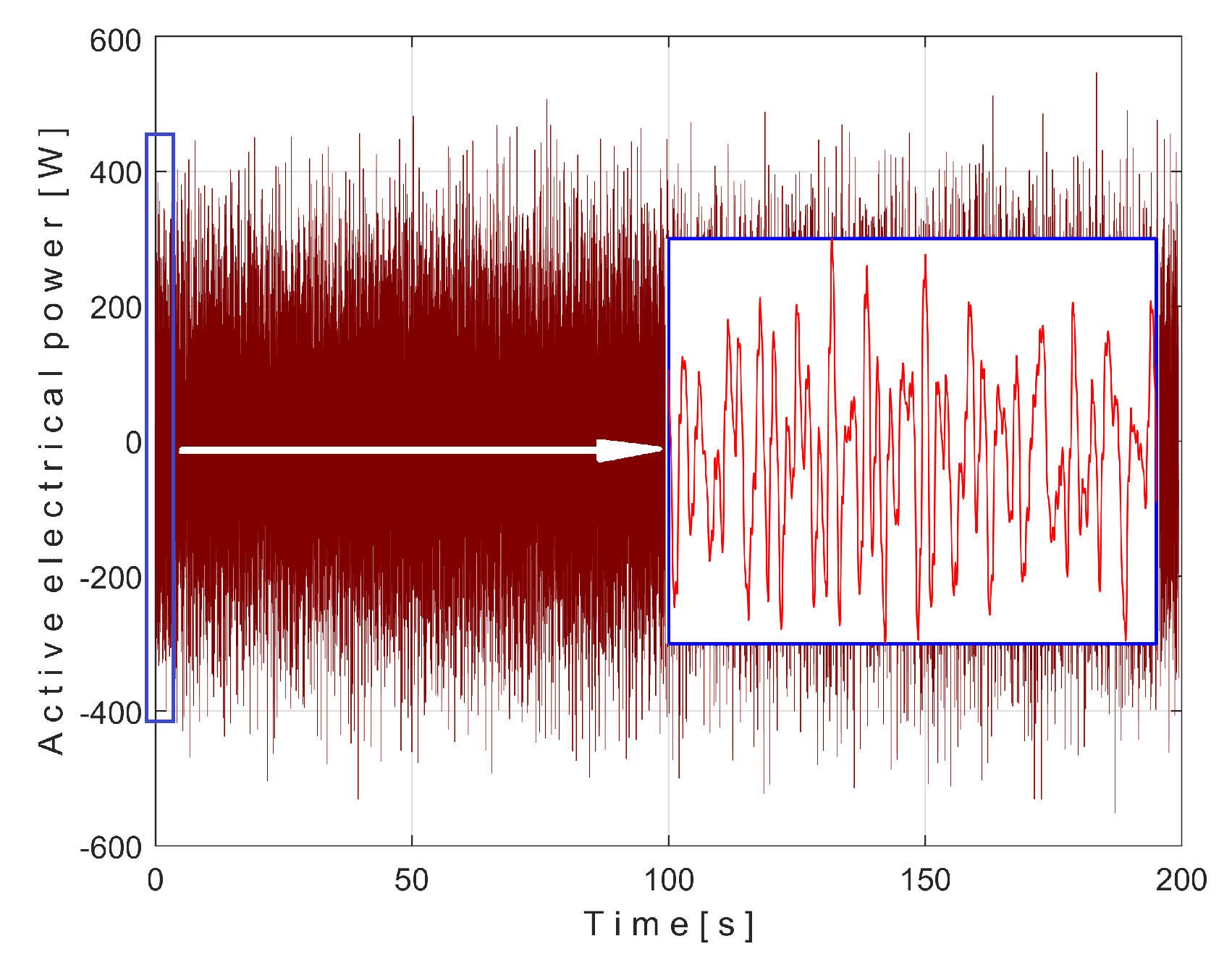

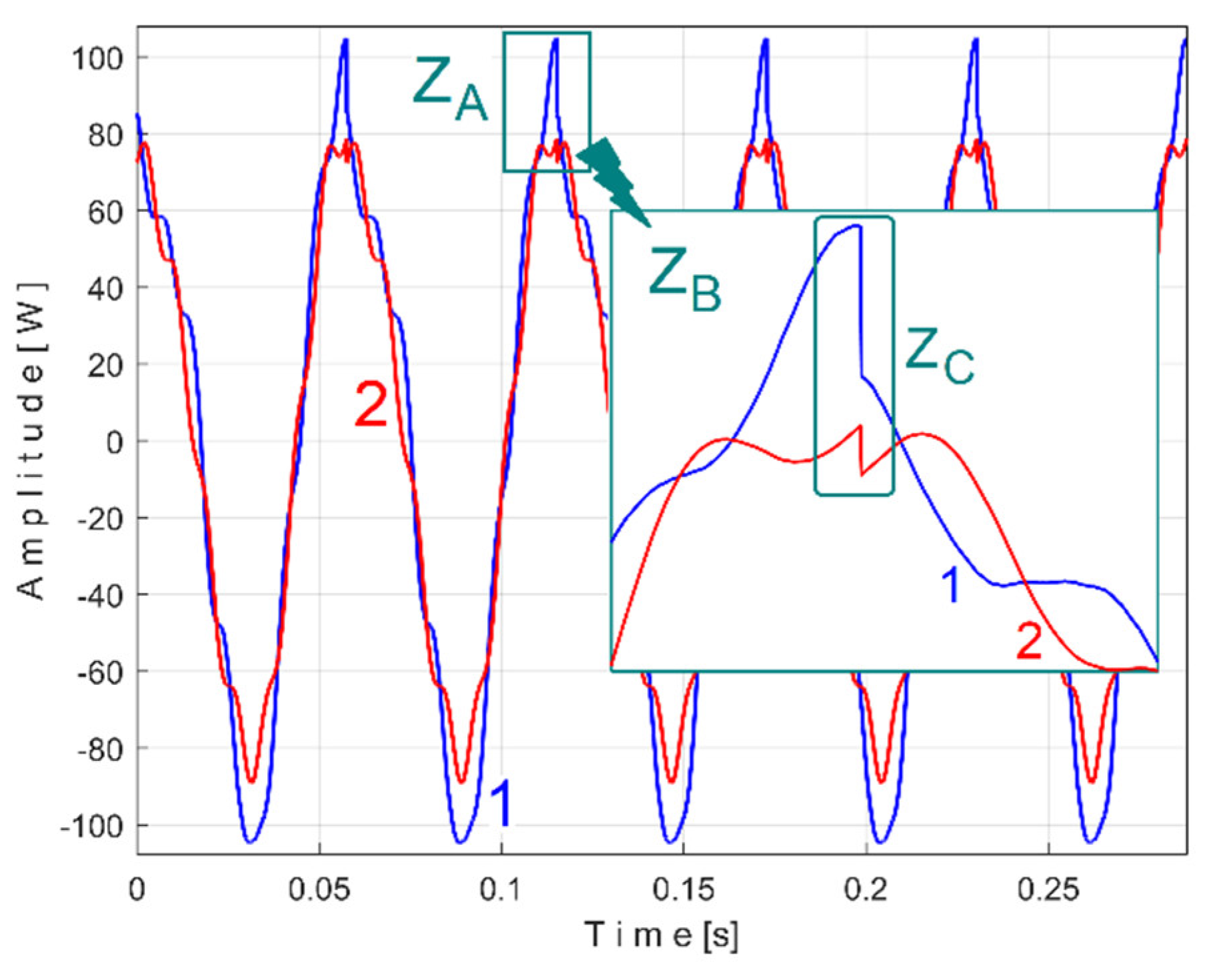

The time-domain representation of

Pav is shown in

Figure 13, with a zoomed-in detail (with 1.5detail with 1.5 s duration) from the beginning, shown in the rectangle on the right. This is a first simple proof that

Pav is a deterministic signal with a very low level of noise. In the time-domain representation of

Pav, many signals are mixed, most of them generated by the parts of gearbox, as will be demonstrated below.

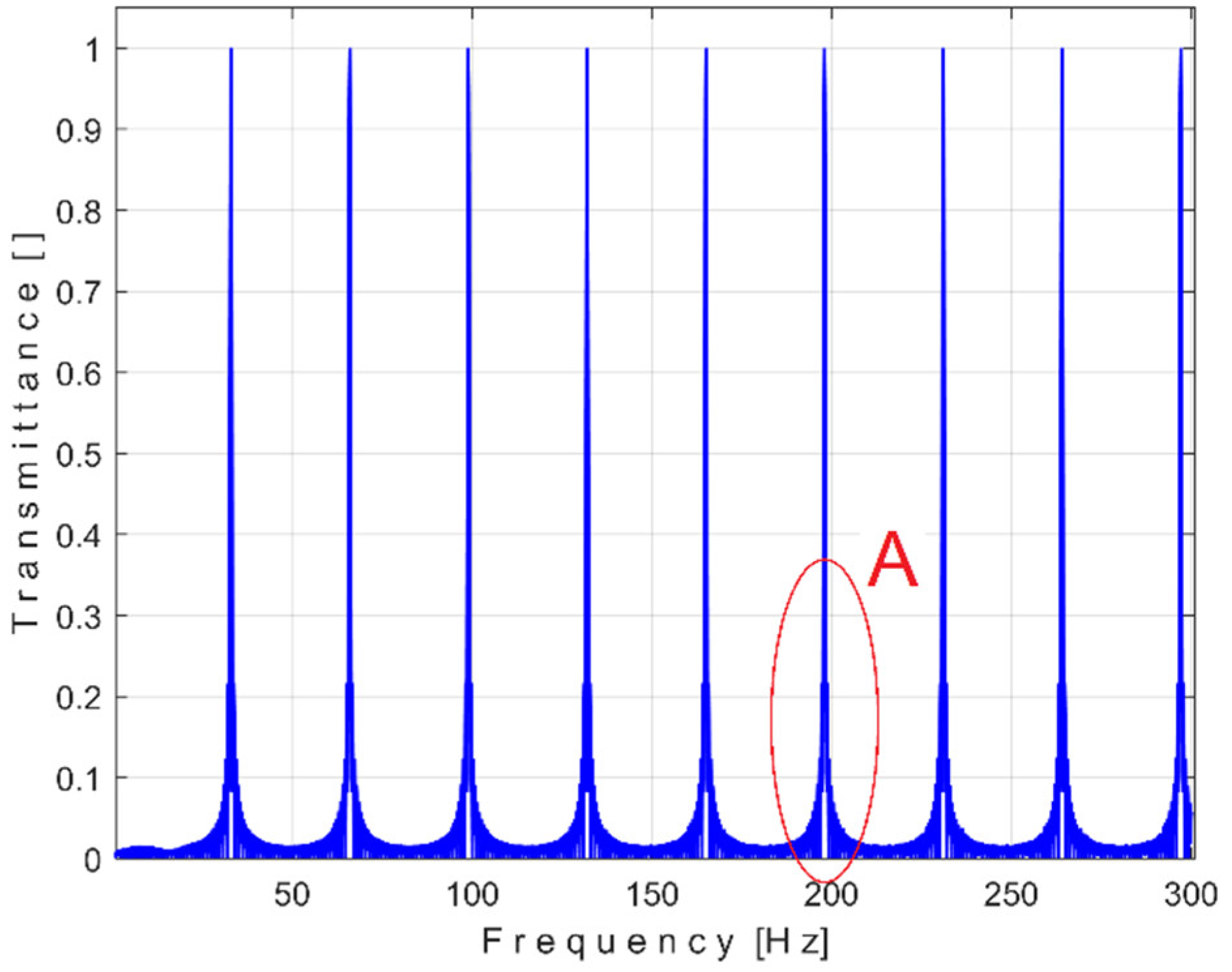

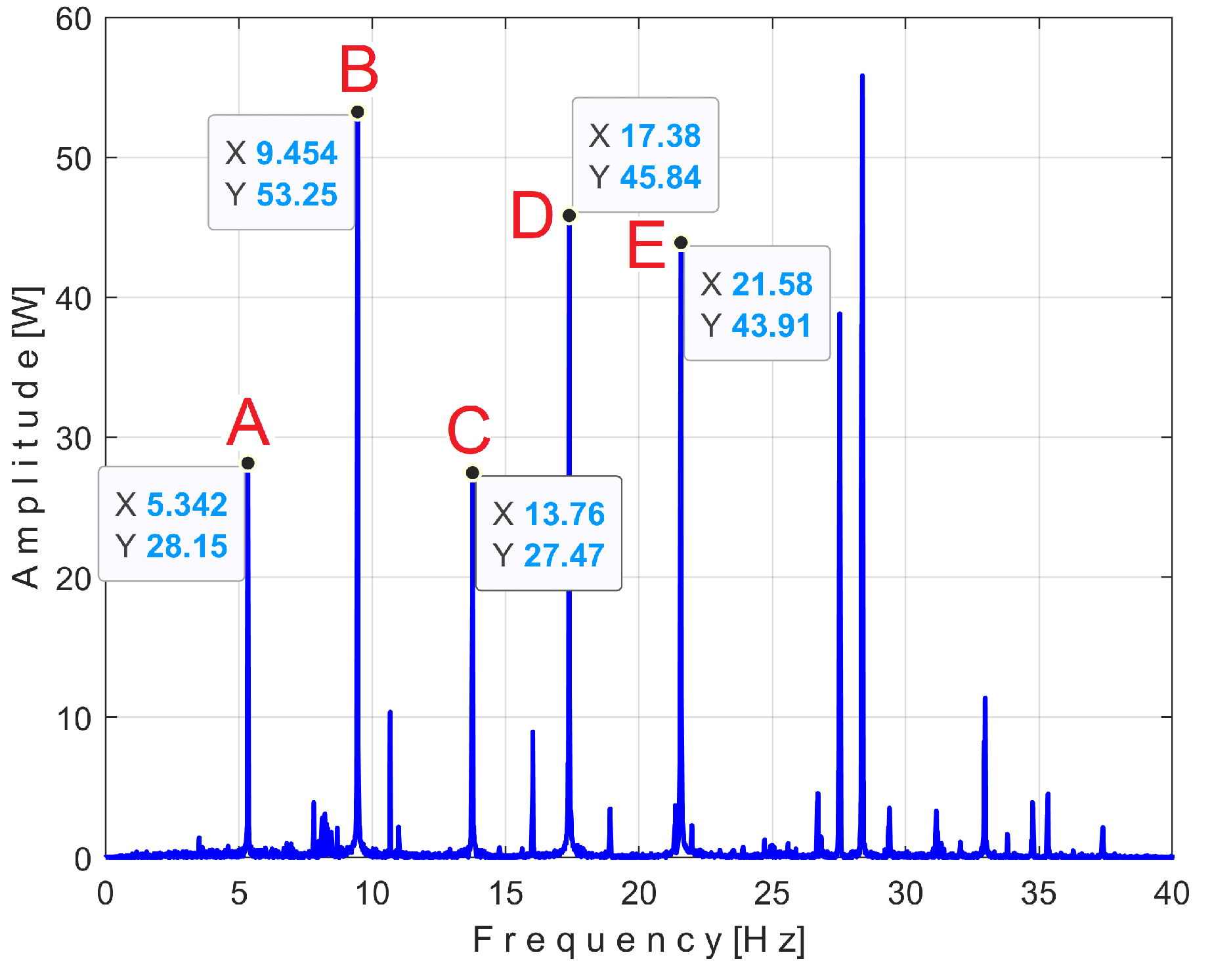

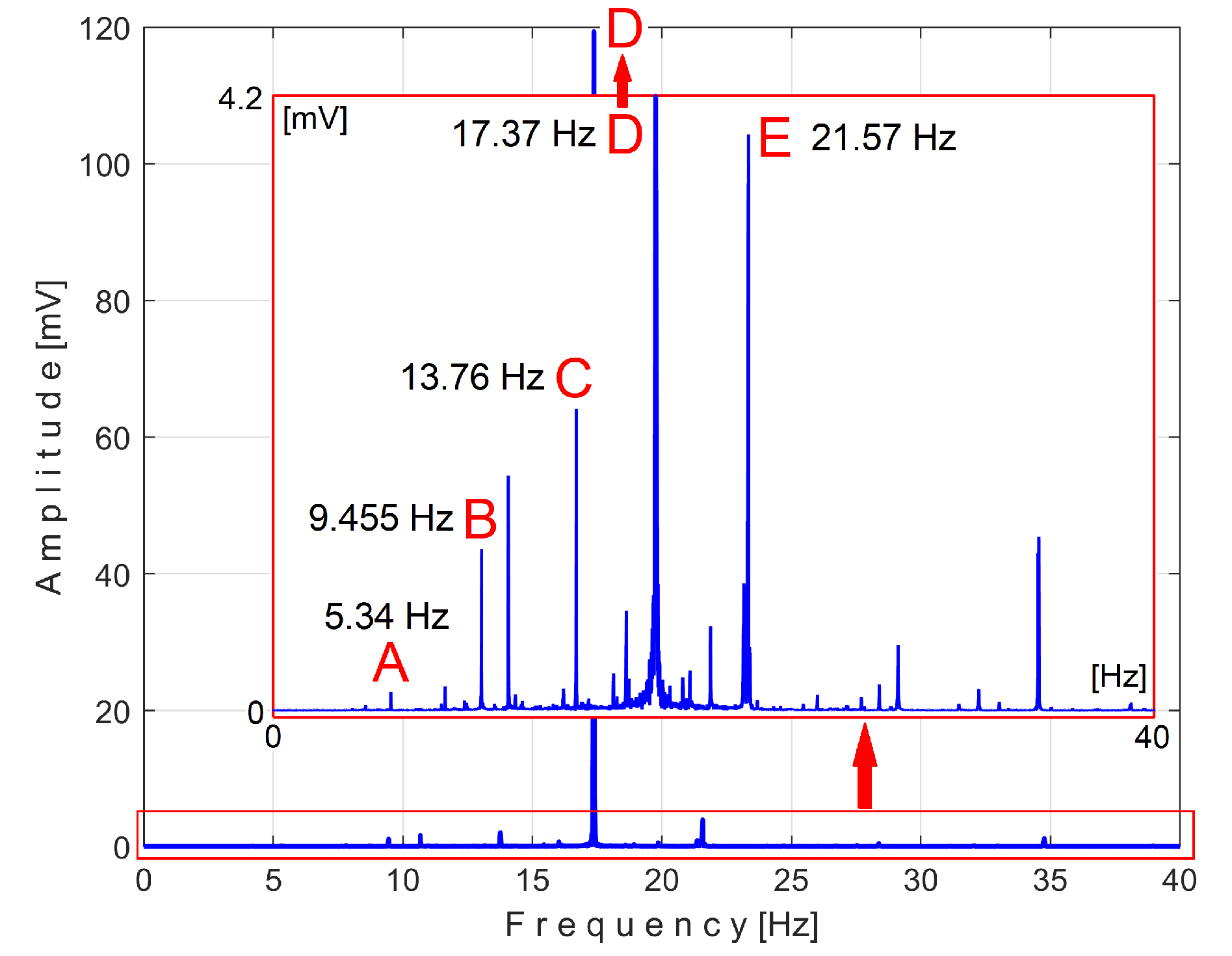

There is a second more reliable proof that the

Pav signal is deterministic with a low level of noise: how the FFT spectrum of

Pav appears, as described in

Figure 14.

According to the study performed before [

3], each of the labeled peaks (A ÷ E) indicates the frequency (inverse of period) and the average amplitude of the fundamental of the periodic components PVSC generated by the flat belt 1 (A), the flat belt 2 (B), the shaft II (C), the shaft III and the spindle (D), the shaft I (E). Some other significant peaks are harmonics of the fundamentals A ÷ E already presented. It should be noted that the peaks in the FFT spectrum describes the average amplitude and frequency of the periodic components. The frequency (and period as well) of some PVSC may vary slightly (here due to a slight variation of motor rotation speed).

The patterns of each of these periodic components (as

sPTA ÷

sPTE) can be extracted from signal

sP by AMSSRTI based on Eq. (1). There is a first way to confirm partially the availability of AMSSRTI, related by the average frequencies

fPA ÷ fPE of peaks A ÷ E revealed in

Figure 14, as already fixed before. For each marked peak in the FFT spectrum (e. g. for the periodic component A), with AMSSRTI applied at the maximum possible value of

m (tending to

mmax =) we search in a small frequency range centered on the value given in the FFT spectrum (e.g.,

fPA = 5.34 Hz) for the frequency (period,

TPA=1/fA) at which the pattern (

sPTA) has the maximum peak-to-peak amplitude. This is the mean value of the frequency of the respective component (

fPA), determined indirectly by AMSSRTI, which is expected to be close to that already shown in the FFT spectrum. This hypothesis is fully confirmed with the results depicted in

Table 1.

For a more understandable graphical representation, we propose a partial extension of the patterns sPTA ÷ sPTE, up to the duration of 5 periods of their fundamentals (as sPTAe5 ÷ sPTEe5 for the MC A), based on Eq. (3) rewritten (as example for the component A), as:

These extended patterns sPTAe5 ÷ sPTEe5 can be obtained by the extension of patterns sPTA ÷ sPTE computed for different numbers of samples (or time durations of the Pav signal) considered in the definition of m < mmax.

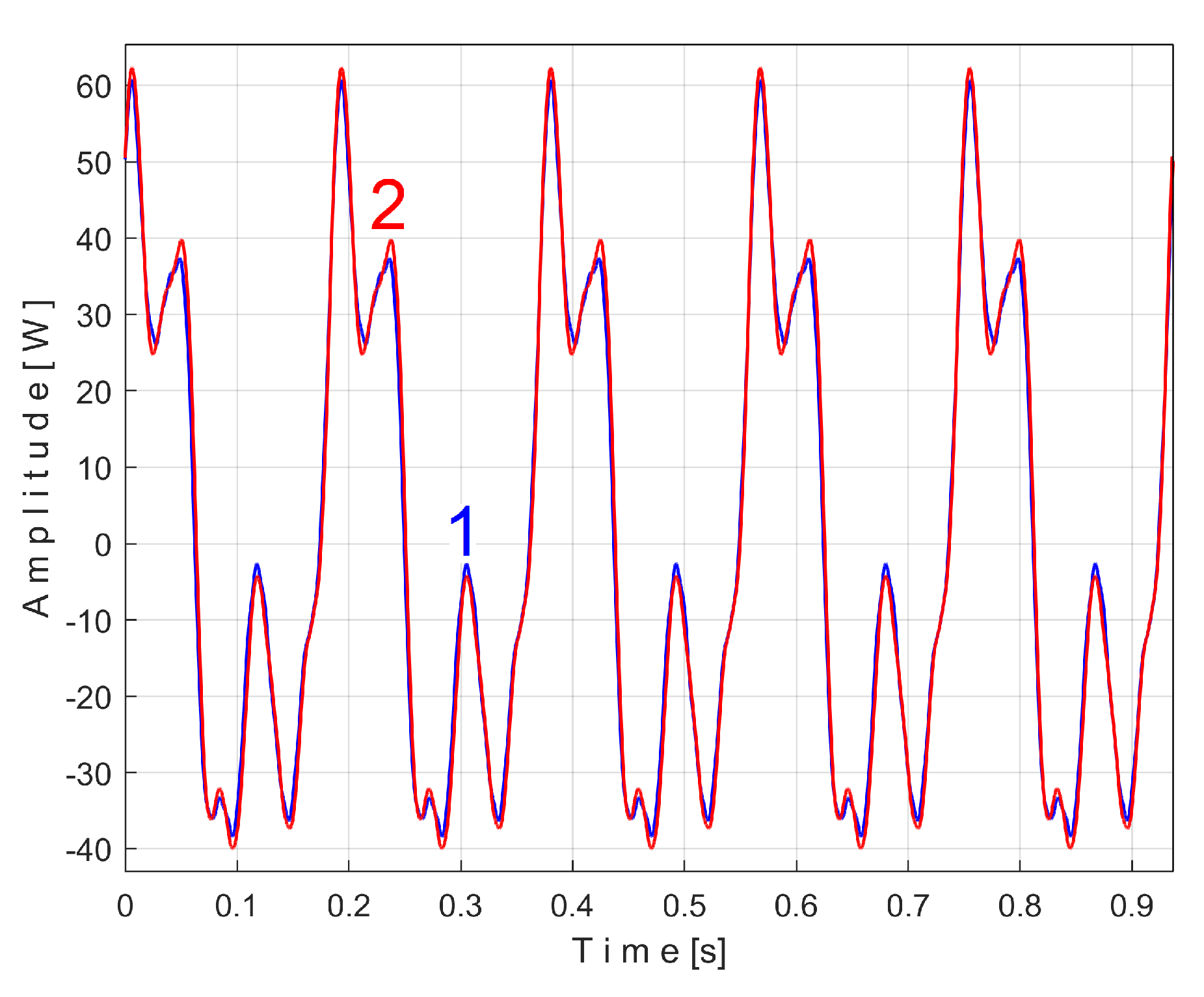

To show the repeatability of the extended patterns sPTAe5 ÷ sPTEe5, there is an interesting possibility: to superimpose each two extended patterns related to the same component (e. g. A), both calculated with AMSSRTI from sPTA ÷ sPTE, for the same m, the first pattern (e. g., as being sPTAe5a) calculated on the first half of the total number of Pav samples (from 1 to pav/2, for almost 100 s), the second pattern (e. g. as being sPTAe5b) calculated on the second half of Pav samples (from pav/2 to pav, also for almost 100 s).

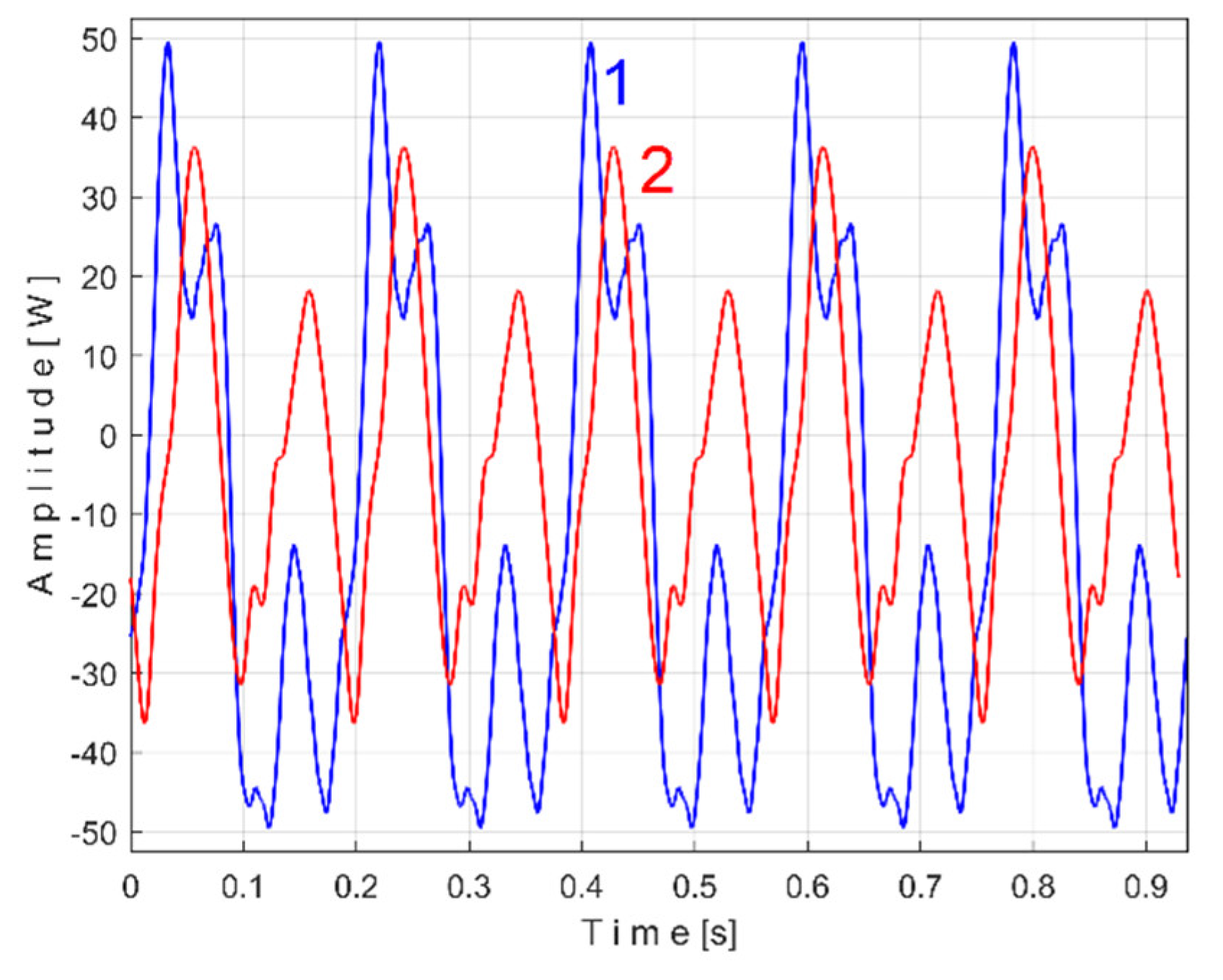

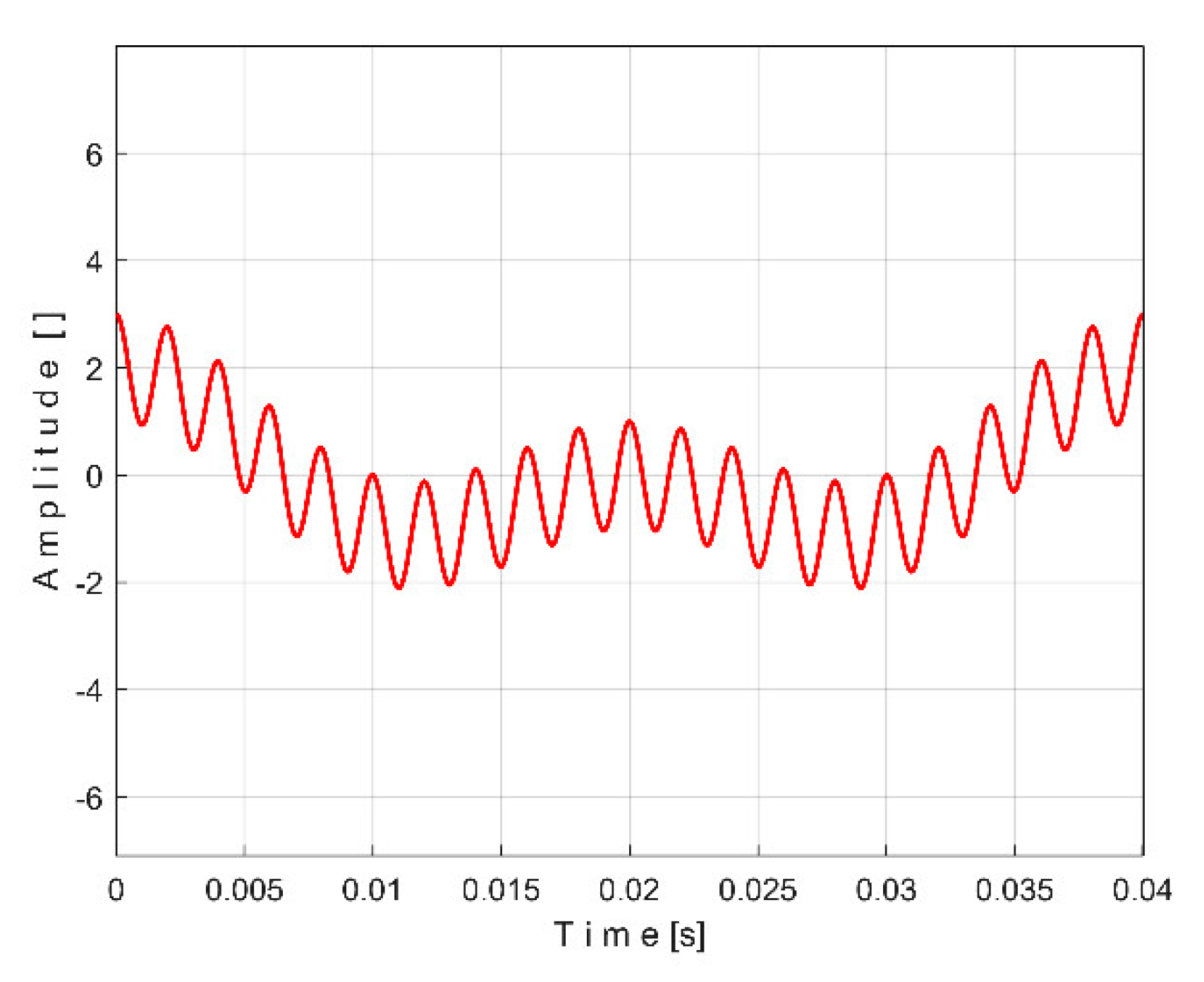

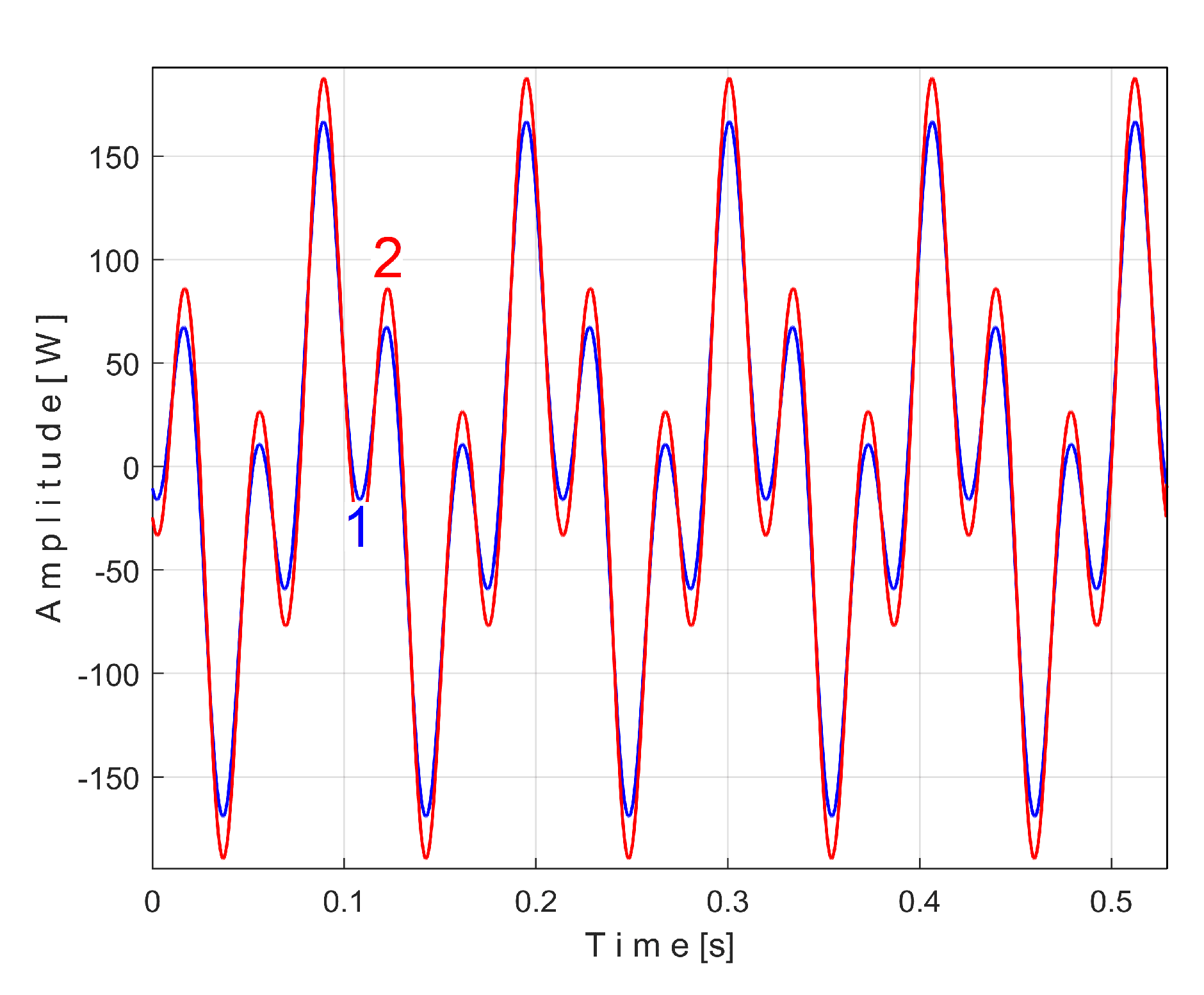

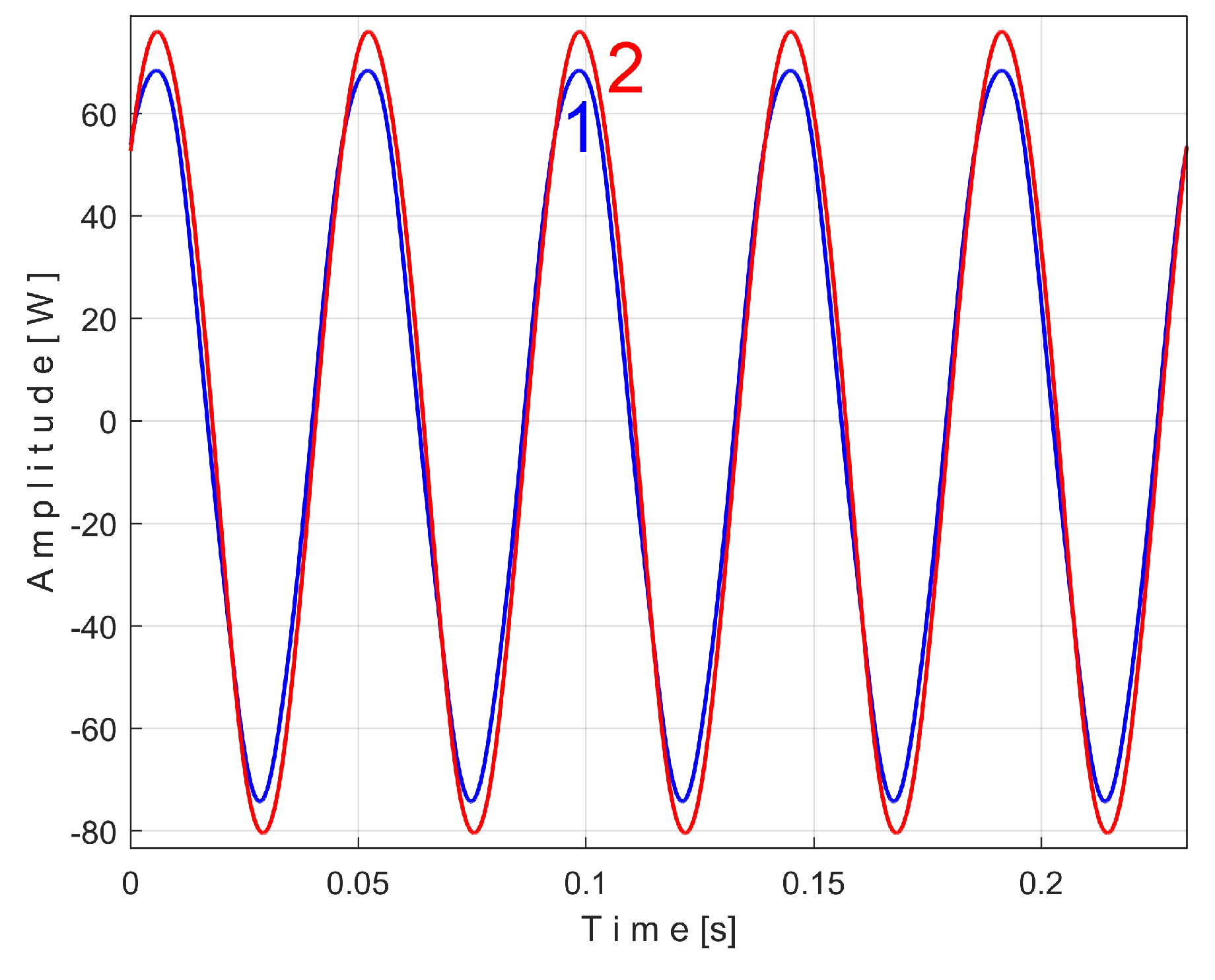

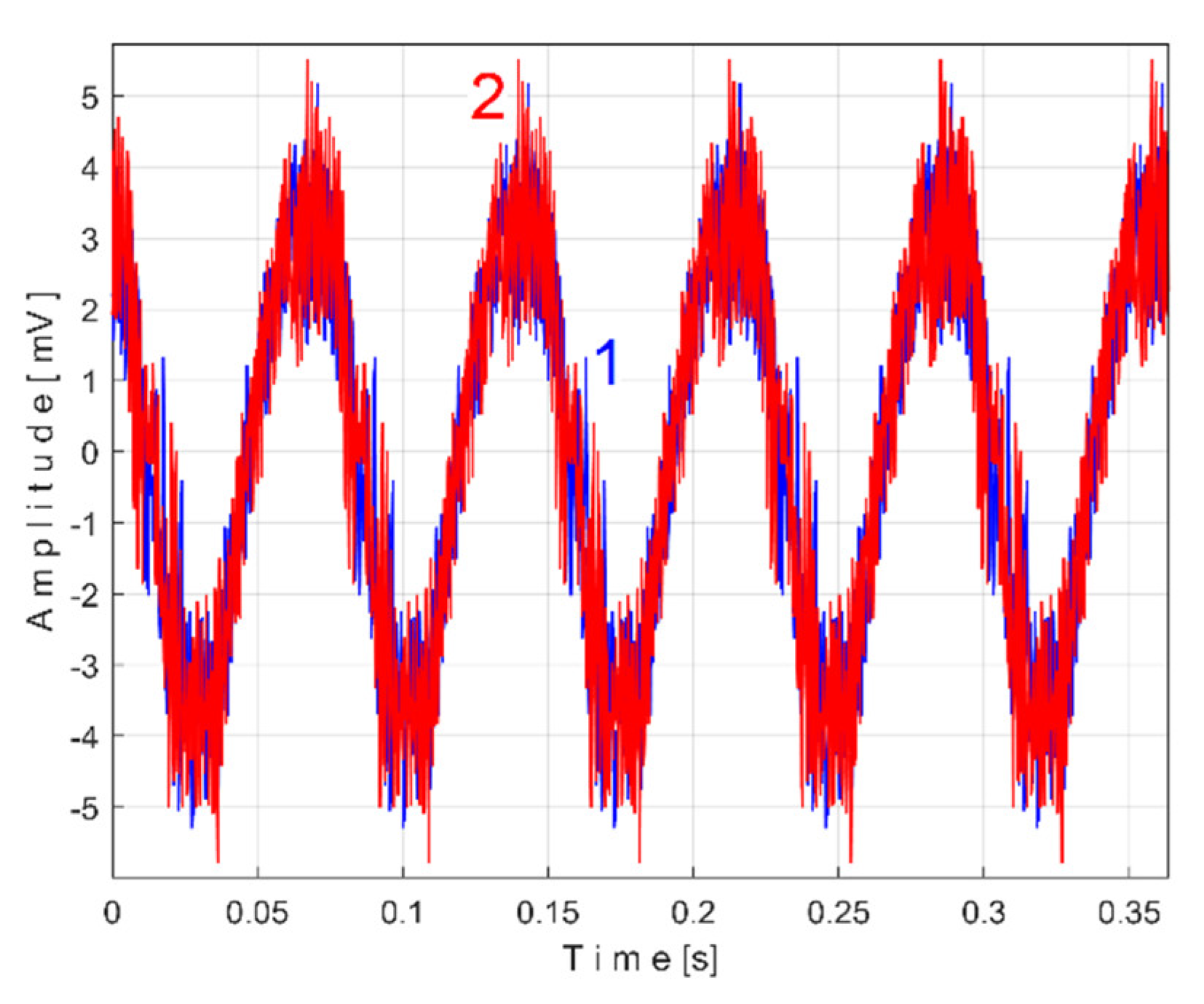

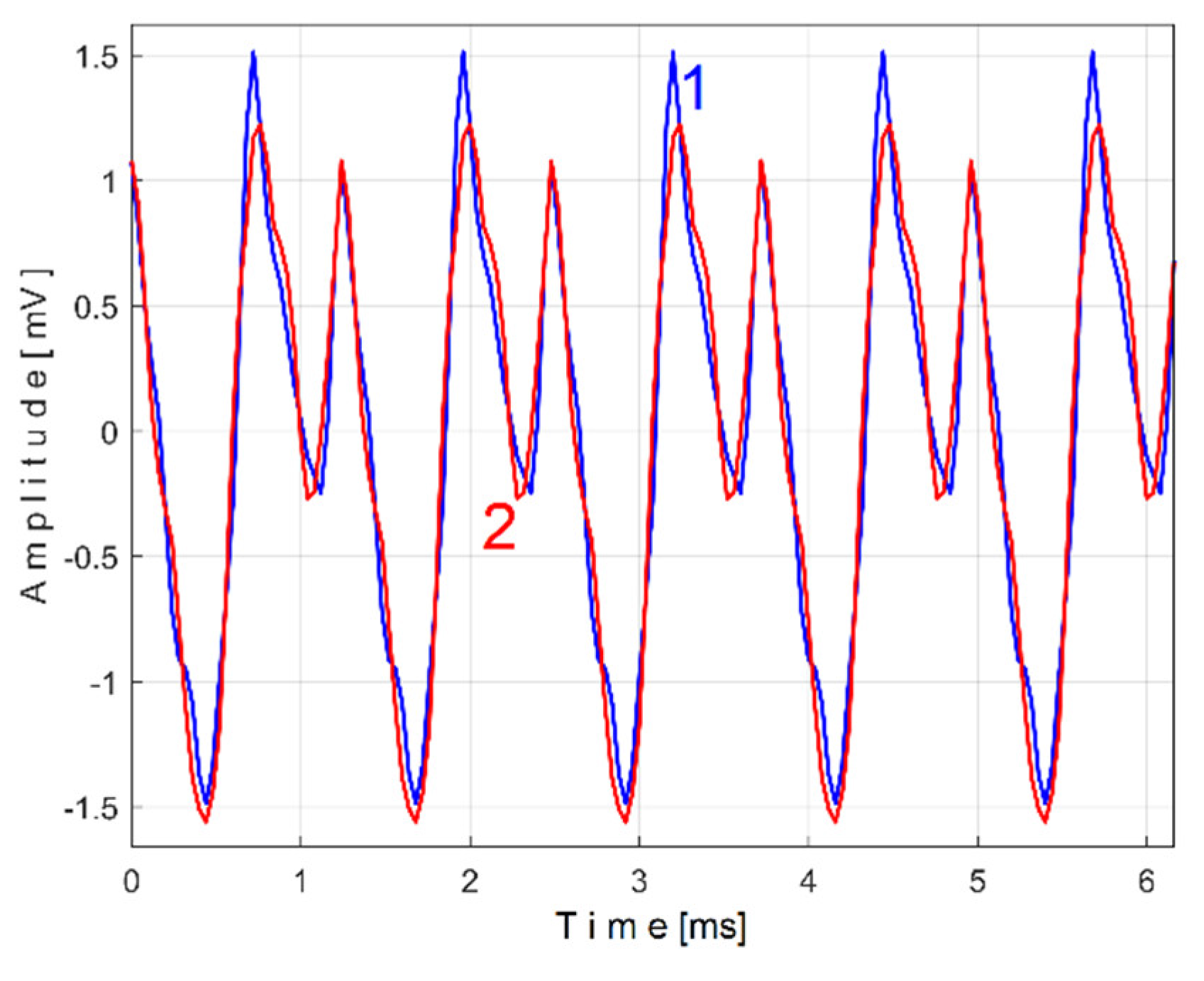

Figure 15 shows the superimposed extended patterns

sPTAe5a (curve 1,

m = 530) and

sPTAe5b (curve 2,

m = 530) related by the periodical component generated by the flat belt 1. We found that the average frequency

fPA (or period

TPA= 1/fPA) to consider in AMSSRTI for each extended pattern (whose which produces maximum peak-to-peak amplitude of the pattern) is slightly different:

fPAa =

5.3368 Hz for

sPTAe5a and

fPAb =

5.3414 Hz for

sPTAe5b. The sample at the beginning of the

Pav sequence from which the second extended pattern (

sPTAe5b) has been deduced (in a first approach

pav/2) is conveniently changed to obtain the most correct possible overlap of the two patterns.

It is obvious that both patterns are quite similar (the flat belt is relatively new), as an argument for the repeatability, for the availability of AMSSRTI in condition monitoring of this flat belt transmission. There are some minor differences (except for the average frequency/period): the behavior of the belt is slightly changed in time probably because of heating due to slippage. This variation of the active electrical power is a direct consequence of the variation of the mechanical power induced by the belt and therefore of the belt behavior. During one period of this pattern, there is full belt circulation on the pulleys. The variation of the active electrical (mechanical) power is caused by the variation of the belt properties (e.g., stiffness) and does not necessarily describes (in this case) a critical belt failure.

The analytical description of the patterns can be found by using the

Curve Fitting Tool application from Matlab, as the sum of harmonically correlated sinusoidal components (sine waves).

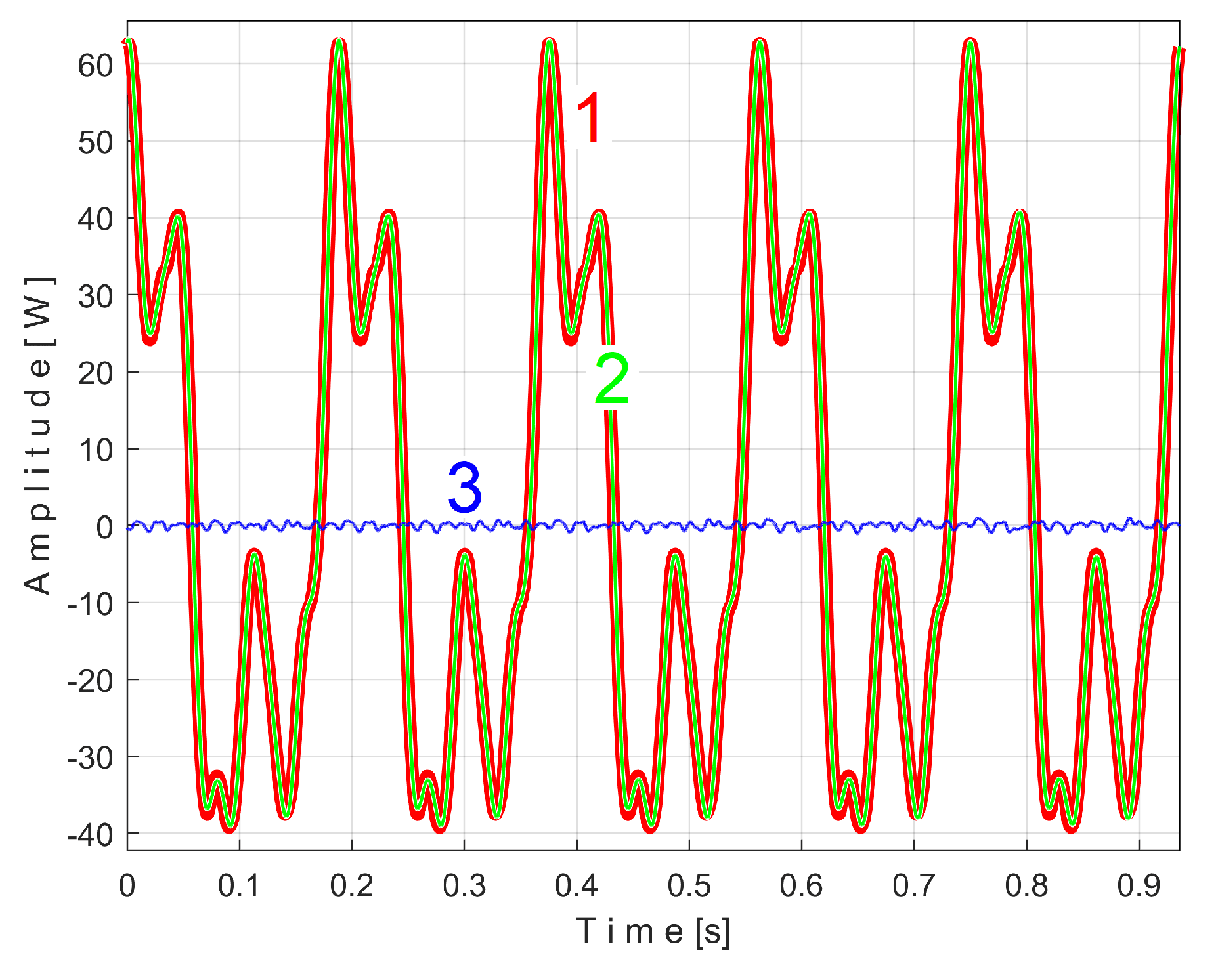

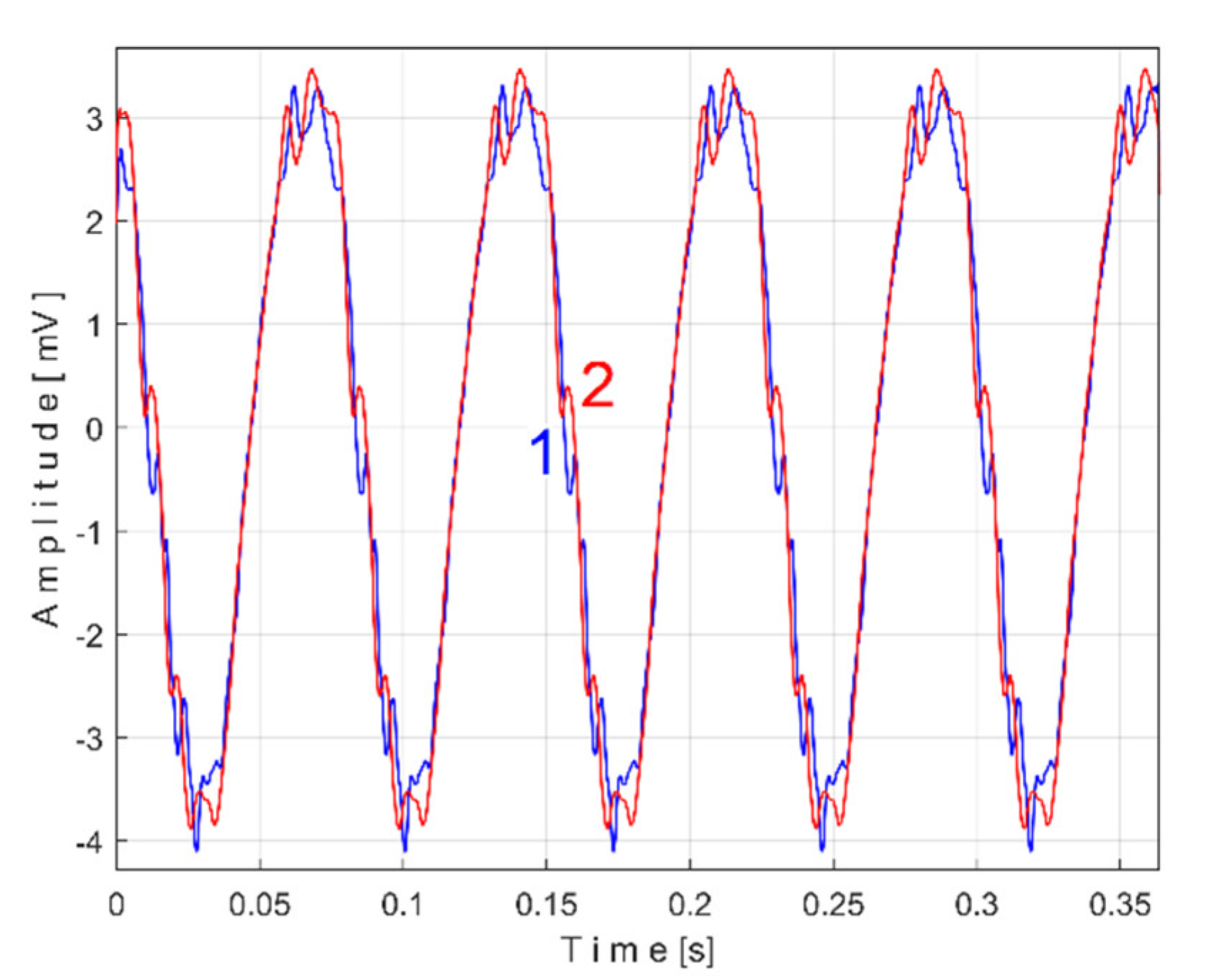

Figure 16 shows the

sPTAe5b pattern (as curve 1), the pattern based on the analytical description as the addition of eight harmonically correlated sinusoidal components (as curve 2, an addition of a fundamental F

PA and seven harmonics H

PA1, H

PA2,…H

PA6 and H

PA8) and the residuals (curve 3) as the difference between. These sinusoidal components are described in

Table 2.

We should mention that a very complicated procedure for finding the shape of the extended pattern for the PVSC generated by the first flat belt has already been presented in a previous work [

3].

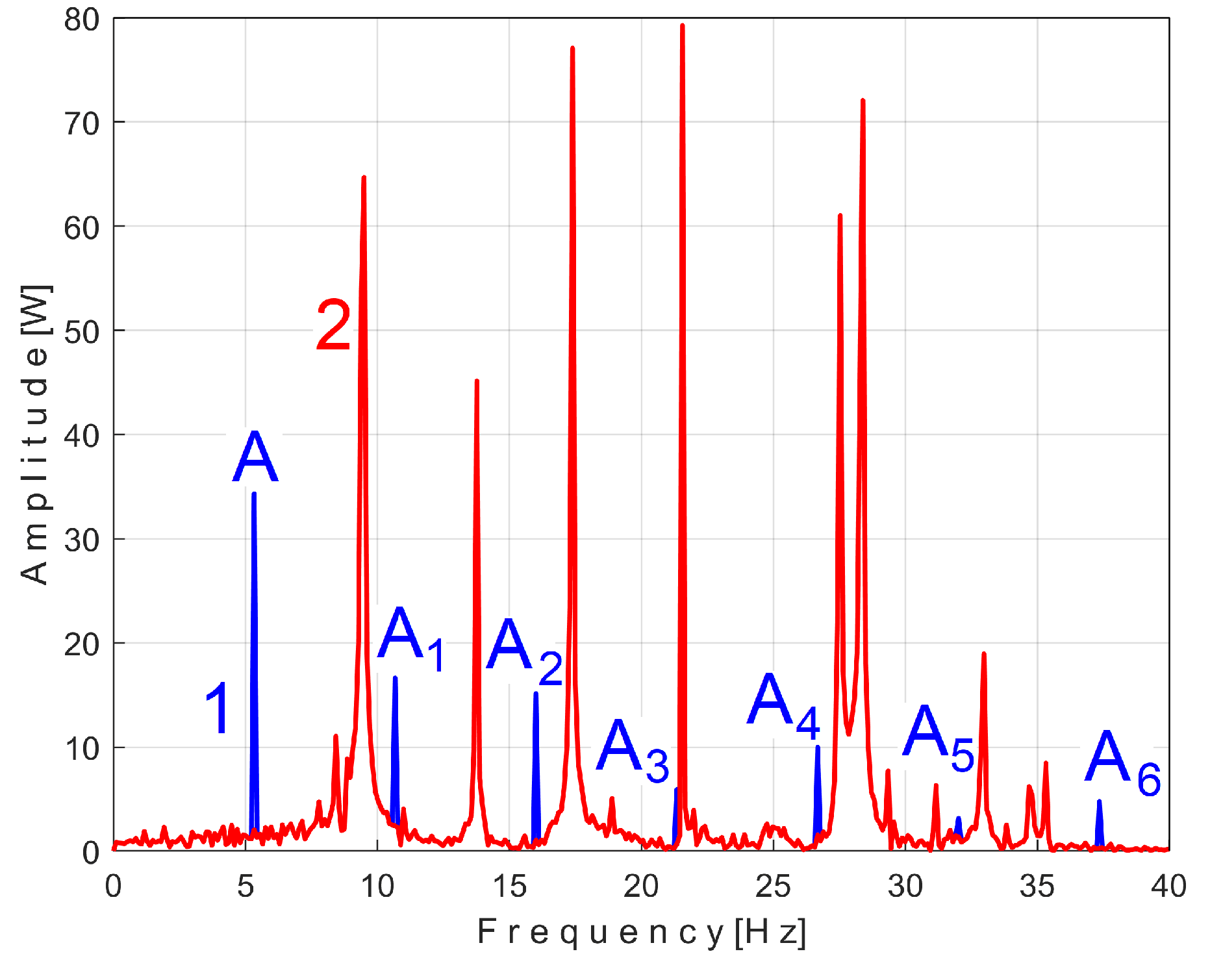

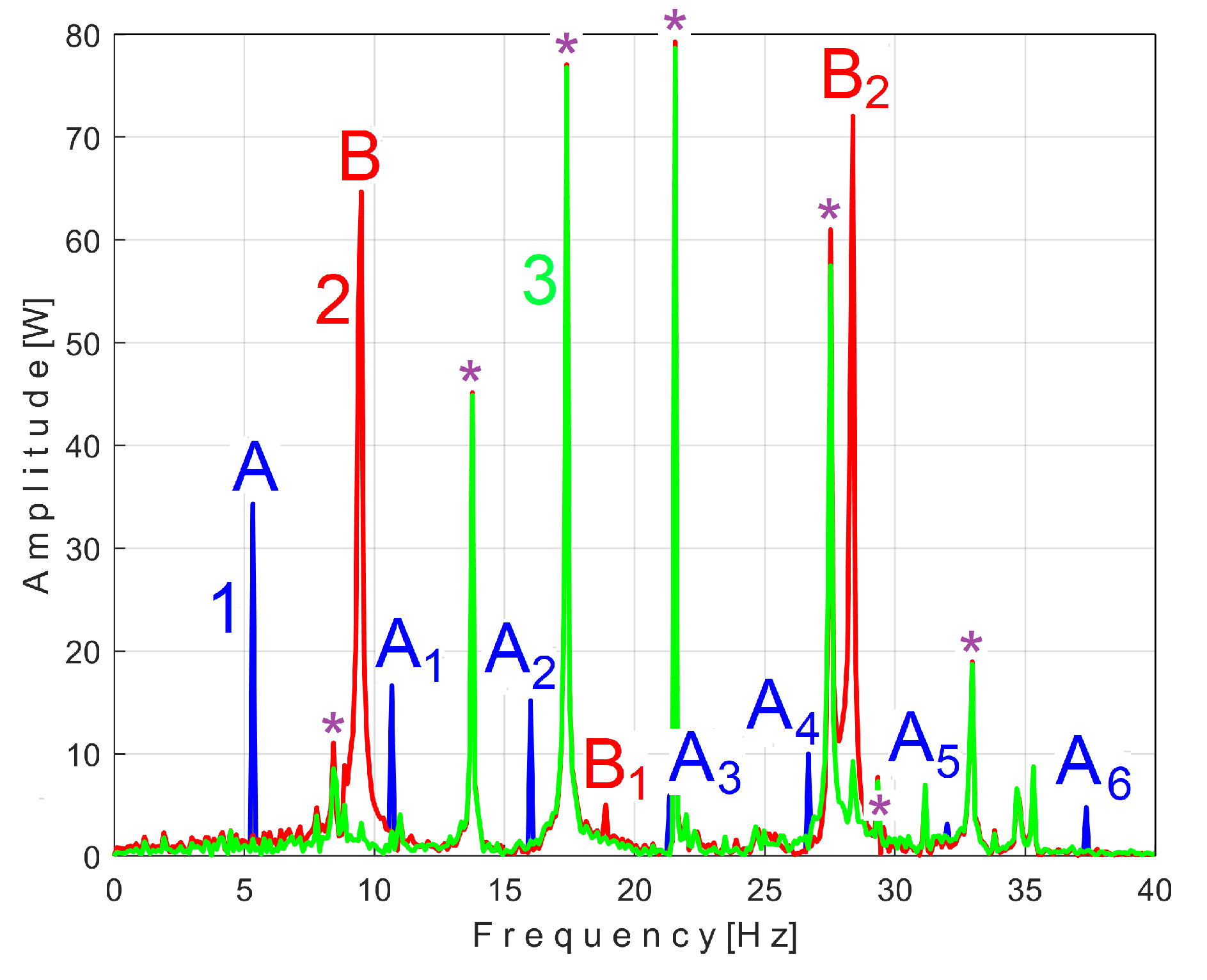

There is another important argument for the correctness of the AMSSRTI approach. Let us take a sequence of

Pav with the duration of 50 periods

TPA (234,300 samples for 9.372 s) from its beginning (as

sP50). Correspondingly, the exact value of the frequency

fPA=5.33448 Hz and the extended pattern

sPTAe50 were determined. In

Figure 17, the FFT spectrum of the sequence

sP50 (in the range 0-40 Hz) is marked as 1. The FFT spectrum of the signal

sP1r50 resulting from the mathematical extraction of this extended pattern from the analyzed sequence (with a sample described as

sP1r50[k] =

sP50[k] - sPTAe50[k]) is marked as 2. It is evident that the fundamental A and its 6 harmonics (A

1 ÷A

6) have disappeared from the spectrum 2 as a result of the elimination of the extended pattern

sPTAe50 from signal

sP50. For any other area (except the blue peaks), the two spectra are identical (the spectrum 2 is perfectly superimposed on spectrum 1).

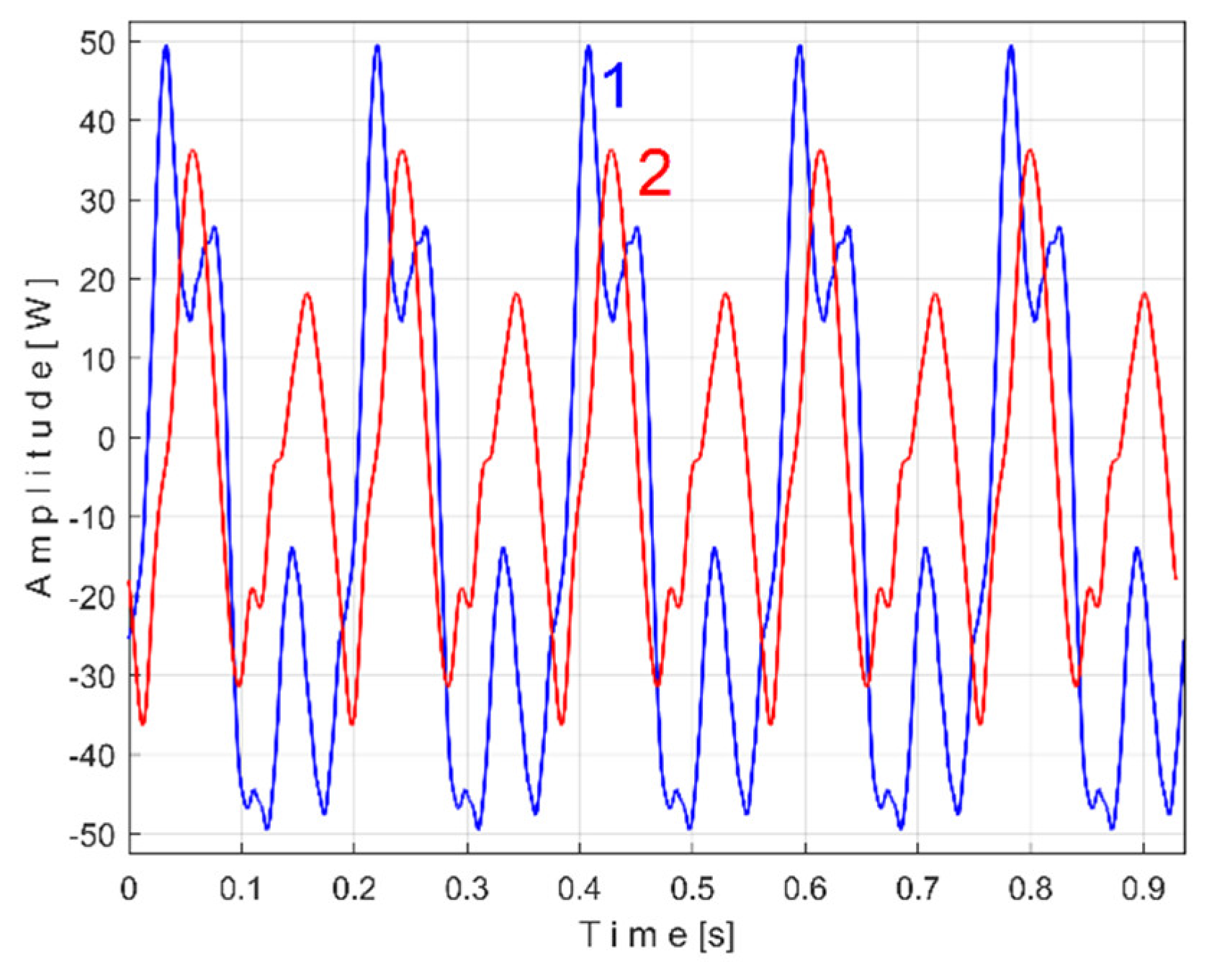

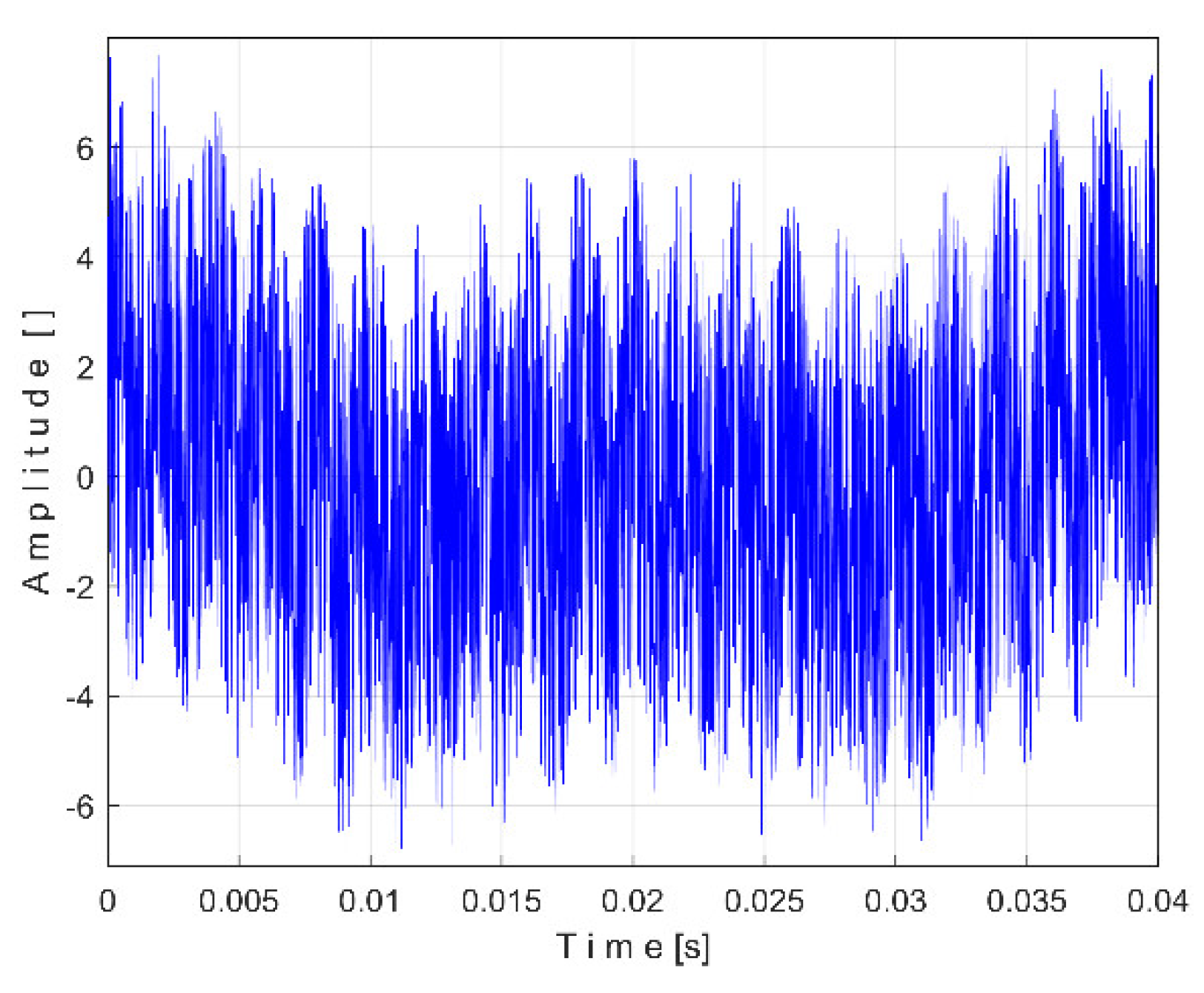

Similarly with

Figure 15,

Figure 18 shows the superimposed extended patterns

sPTBe5a (curve 1,

m = 935) and

sPTBe5b (curve 2,

m = 935) related with the periodical component generated by the flat belt 2. We found that the average frequency

fPB (or period

TPB = 1/fPB) to consider in AMSSRTI for each extended pattern (whose which produces maximum peak-to-peak amplitude of the pattern) is quite similar:

fPBa =

9.45223 Hz for

sPTBe5a and

fPBb =

9.45981 Hz for

sPTBe5b.

There are not very significant differences between the extended patterns, except for the peak-to-peak amplitude, which is most likely related to the increase in temperature. It should be noted, however, that the peak-to-peak amplitude of the variable component of the active electrical power induced by the flat belt 2 is much greater than that induced by the flat belt 1. Most likely, this belt is close to the breakage limit, as it is 35 years older than the first one.

An extended pattern

sPTBe89 with 235.494 samples was generated (from a sequence of 89 periods

TPB at the beginning of

Pav, with

m = 89 and the best approximation of the average value of the frequency

fPB = 9.446896Hz in AMSSRTI). This pattern is downsized at first 234.300 samples, and renamed

sPTBe89*. Now the

sPTBe89* extended pattern has the same number of samples as the sequence

sP50 and the extended pattern

sPTAe50 (both previously used to generate

Figure 17). It can be mathematically eliminated from

sP1r50 signal, a new signal is obtained as

sP2r50, with a sample described as

sP2r50[k] =

sP1r50[k] - sPTBe89*[k] = sP50[k] - sPTAe50[k] - sPTBe89*[k]. The downsizing of

sPTBe89 until

sPTBe89*[k] was necessary to perform the mathematical subtraction above.

In other words, this signal

sP2r50[k] is described with 234,300 samples taken from the beginning of

Pav (as sequence

s50) but after removing from sequence

sP50 the periodical component generated by first and second flat belt (

sPTAe50[k] respectively

sPTBe89*[k]). The result of this subtraction is highlighted in the FFT spectrum of signal

sP2r50 (marked with 3 in

Figure 19, an extension of the result from

Figure 17).

It is clear that, in addition to the result and comments of

Figure 17, the removal of the PVSC generated by the second flat belt also causes the disappearance of the peaks associated with this component (the fundamental B, and the harmonics B

1, B

2) from the FFT spectrum. Obviously, looking at

Figure 19, the components B, and B

2 do not disappear completely, but rather some peaks of the FFT spectrum are diminished (the peaks marked with the symbol *). There is a partial explanation for this shortcoming: the periodic component generated by this second flat belt changes its amplitude more strongly with time (compared to the first flat belt), as already seen in

Figure 18.

It is expected that the removing of these extended patterns from a lengthier Pav signal sequence no longer produces the same results in the FFT spectrum, characterized by the complete disappearance of peaks.

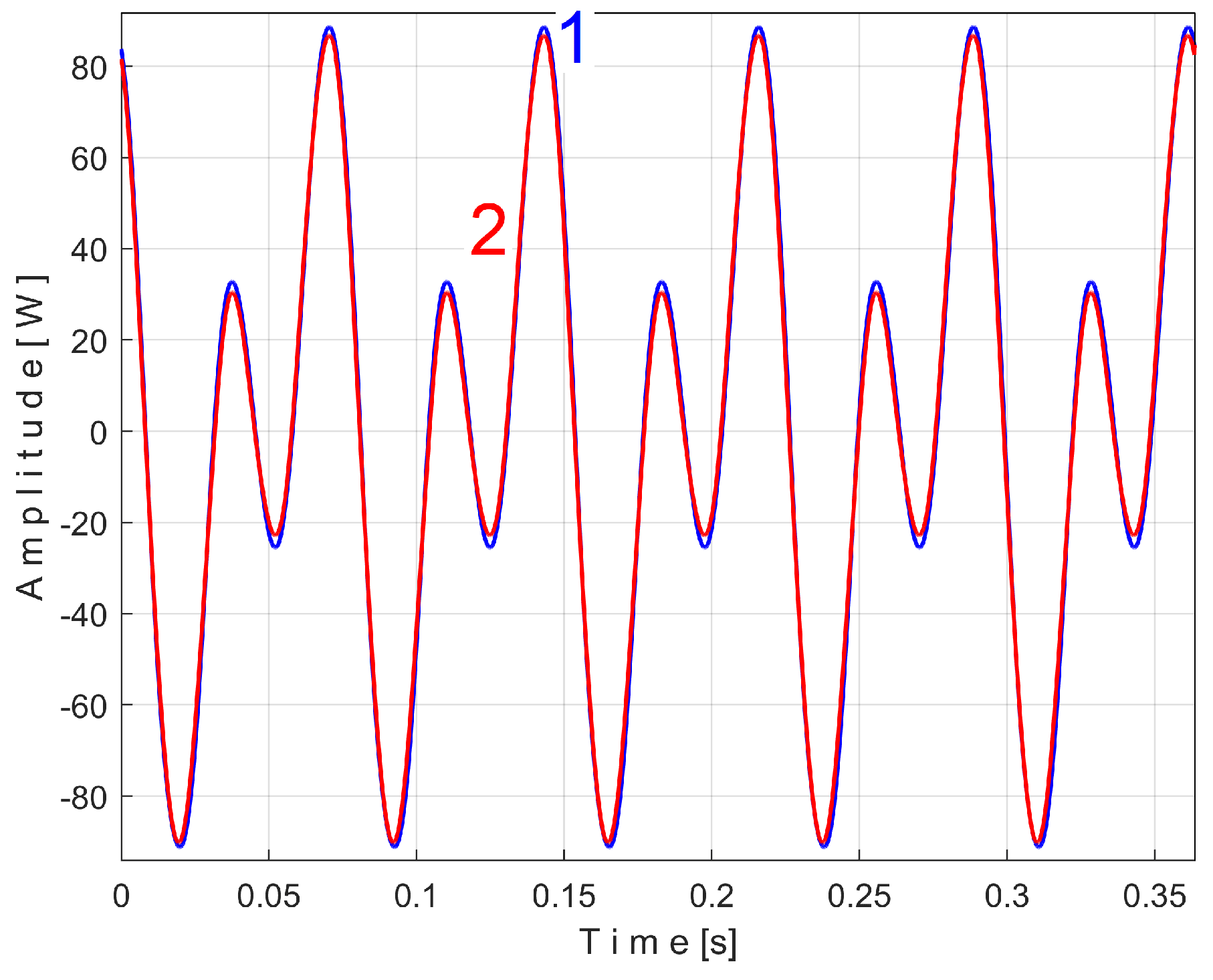

Similarly with

Figure 15 and

Figure 18,

Figure 20 shows the superimposed extended patterns

sPTCe5a (curve 1,

m = 1350) and

sPTCe5b (curve 2,

m = 1350) related with the periodical component generated by the shaft II. We found that the average frequency

fPC (or period

TPC = 1/fPC) to consider in AMSSRTI for each extended pattern (whose which produces maximum peak-to-peak amplitude of the pattern) is quite similar:

fPCa =

13.75435 Hz for

sPTCe5a and

fPCb =

13.759 Hz for

sPTCe5b. Except a small difference between peak-to-peak amplitudes, there is a very good coincidence between patterns.

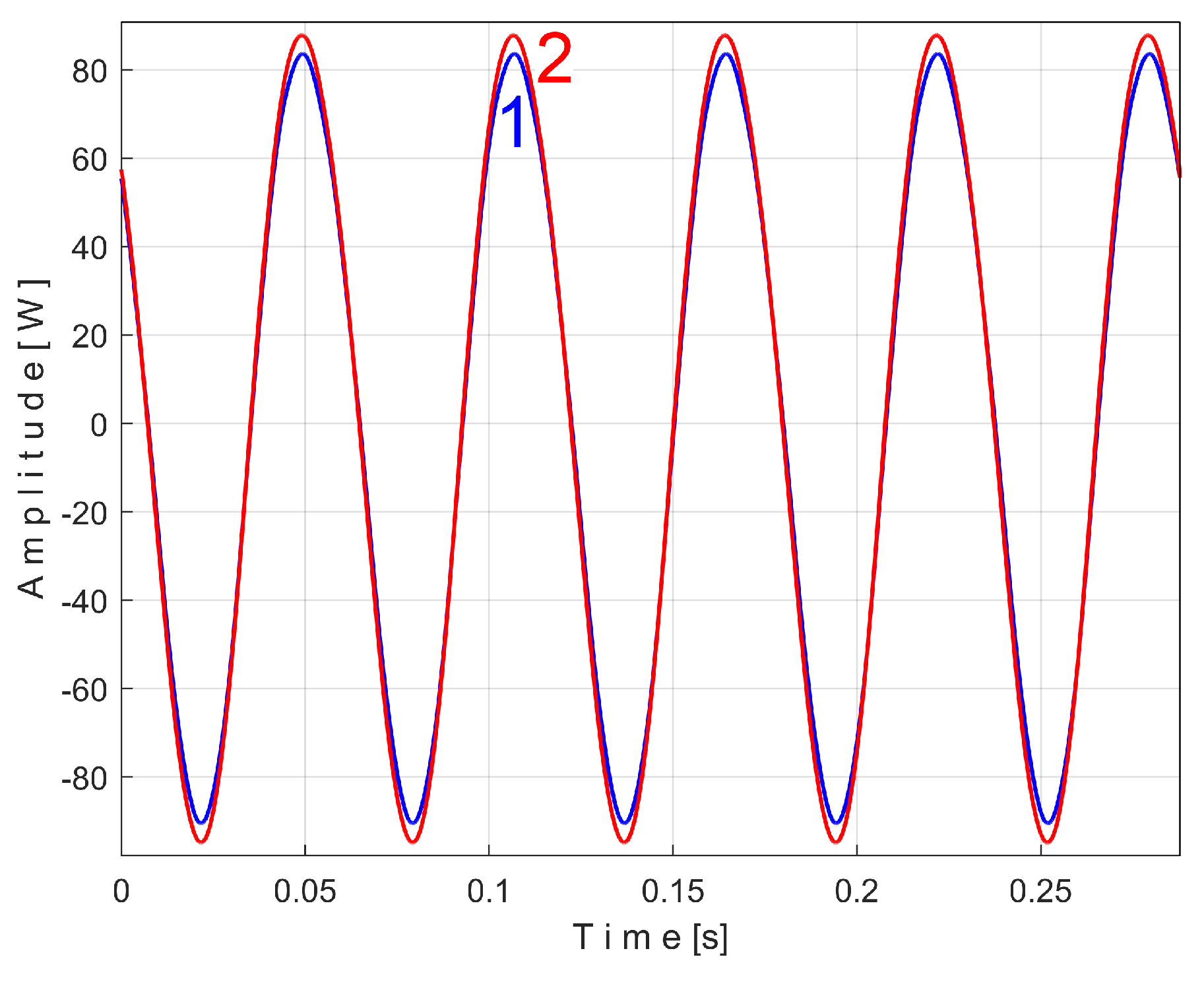

Figure 21 shows the superimposed extended patterns

sPTDe5a (curve 1,

m = 1720) and

sPTDe5b (curve 2,

m = 1720) related with the periodical component generated by the shaft III and spindle. We found that the average frequency

fPD (or period

TPD = 1/fPD) to consider in AMSSRTI for each extended pattern (whose which produces maximum peak-to-peak amplitude of the pattern) is quite similar:

fPDa =

17.37406 Hz for

sPTDe5a and

fPDb=

17.38745 Hz for

sPTDe5b.

Since the two shafts (III and spindle) have theoretically the same rotational speeds (however, the second belt drive’s transmission ratio is not exactly 1, as indicated in

Figure 11), the AMSSRTI cannot generate a pattern for each of them.

Figure 22 shows the superimposed extended patterns

sPTEe5a (curve 1,

m = 2130) and

sPTEe5b (curve 2,

m = 2130) related with the periodical component generated by the shaft I. The average frequency

fPE (or period

TPE = 1/fPE) to consider in AMSSRTI for each extended pattern (which produces maximum peak-to-peak amplitude of the pattern) is quite similar:

fPEa =

21.5606 Hz for

sPTEe5a and

fPEb=

21.5781 Hz for

sPTEe5b. A small changing in amplitude of the pattern

sPTEe5b is evident.

The mechanical inertia of the gearbox affects the shape and the size of the extended patterns of the PVSC inside

Pav. It is obvious that

fPAa < fPAb (

Figure 15),

fPBa < fPBb (

Figure 18)….

fPEa < fPEb (

Figure 22). This is due to the increase of the motor speed (probably because the increase of the supply voltage frequency, and certainly because to the decrease of the internal friction due to lubrication).

3.2. Some Results Obtained by Analyzing Vibration Signal Using AMSSRTI

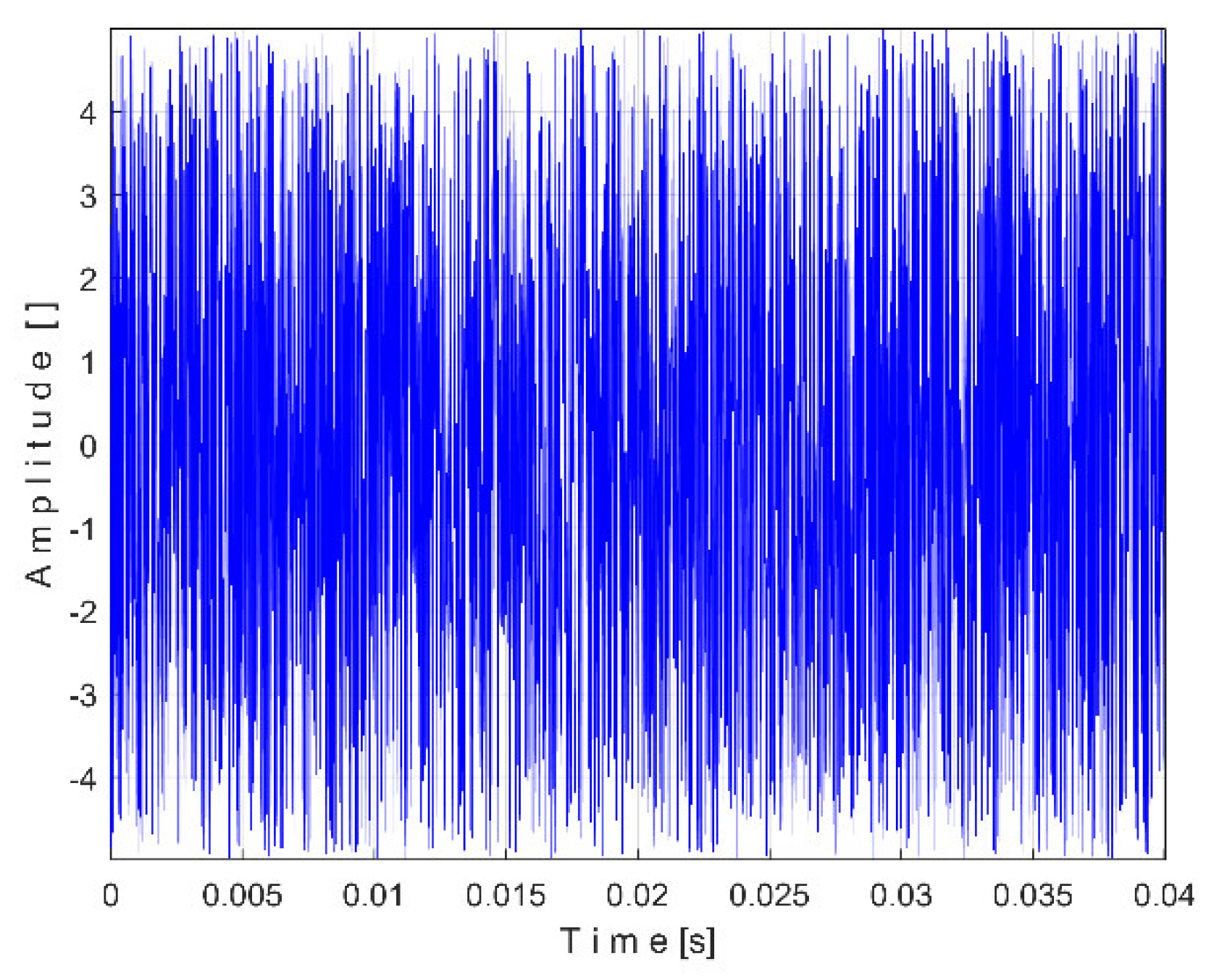

A similar analyze can be done directly on vibration signal

Vs (written as signal

sV). This signal was acquired during the same steady state regime as for active electrical power

Pa previously studied (a sequence of 200 s, with

pa = 5Ms –or 5,000,000 samples-,

Δt = 1/25,000 s as sampling time) and depicted in

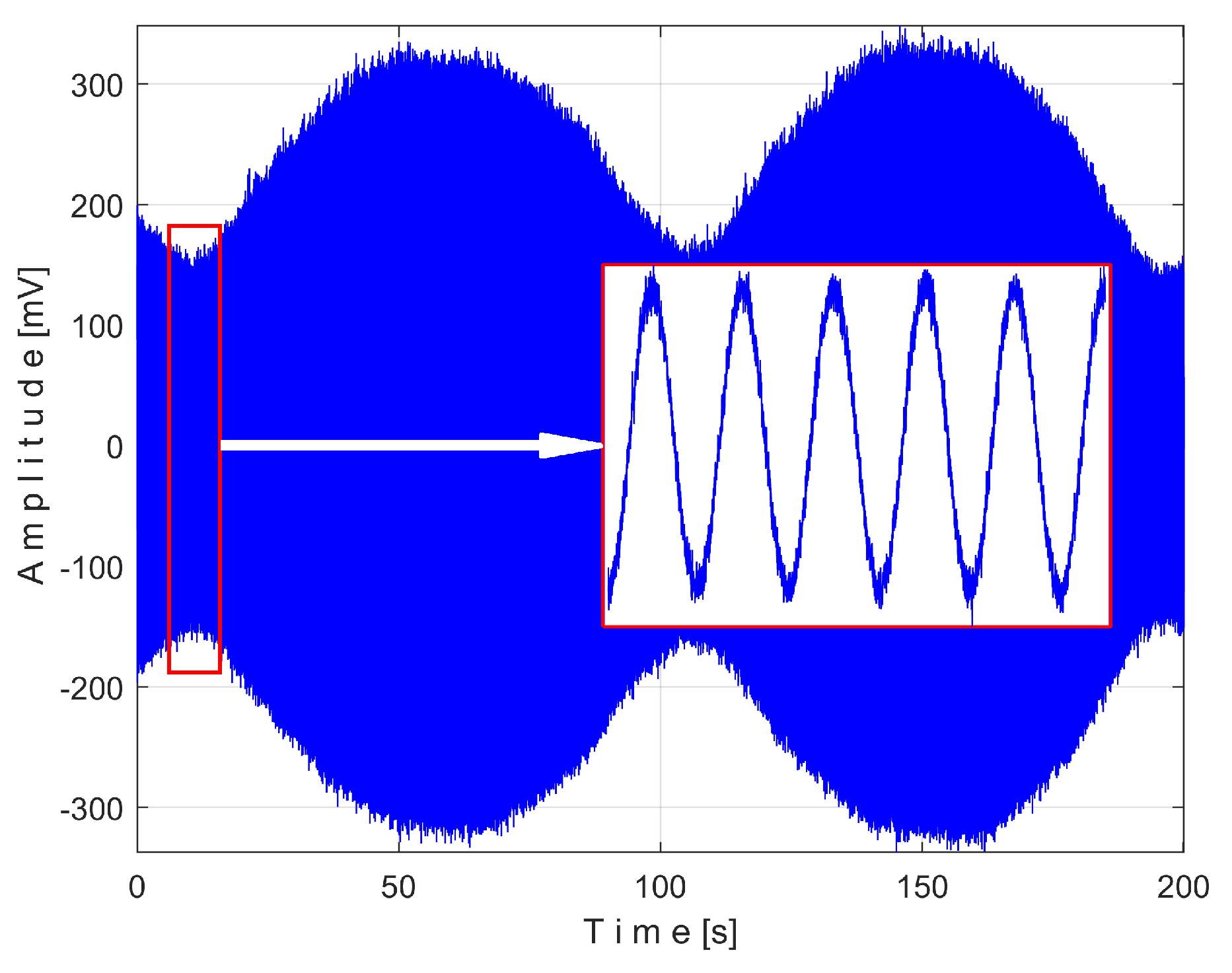

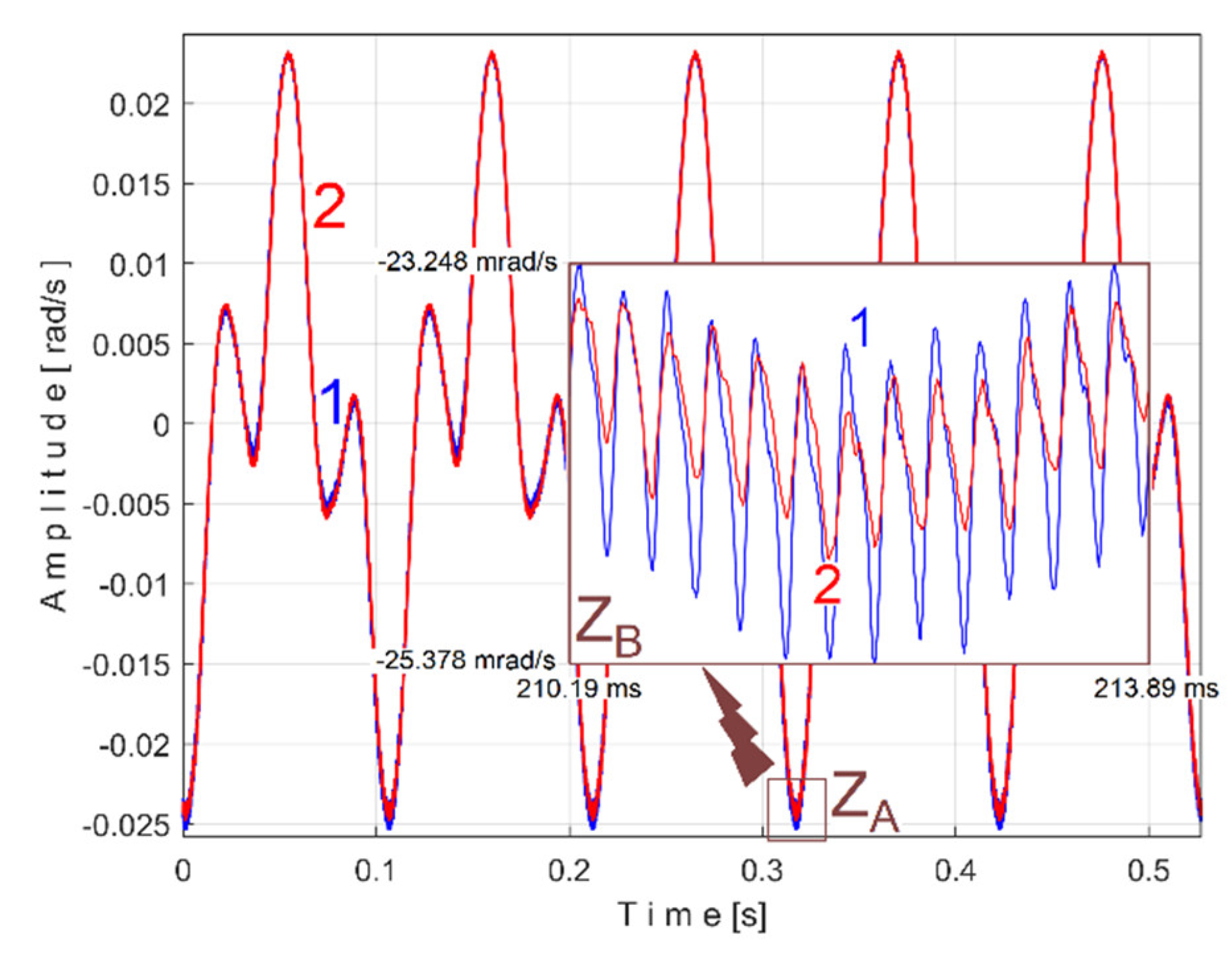

Figure 23.

This signal

Vs describes a beating phenomenon, explained and studied in detail in [

55]. The shaft III and the spindle (both with mechanical unbalance) rotate at almost the same instantaneous angular speed, a beating phenomenon (with nodes and anti-nodes) occurs. There is a dominant vibration, shown in an enlarged detail on

Figure 23 (on the right), with almost the same frequency as the rotation frequency of the spindle. The partial FFT spectrum of this signal (frequency range 0 ÷ 40 Hz) is shown in

Figure 24. A zoomed section of this spectrum is shown in the middle, with the same frequency range and amplitude range severely diminished: 0 ÷ 4.2 mV.

It is surprising that in the FFT spectrum of the

Vs signal, the same A ÷ E fundamentals of the PVSC are present as previously seen in the FFT spectrum of

Pav (

Figure 14). This means that the same phenomena are reflected in the time-domain representation of the active electrical power and vibration. Note that the fundamental A is described with diminished amplitude because it has a frequency below the natural frequency of the sensor (approx. 8 Hz). As expected, there is a dominant PVSC (with D as fundamental, 17 37 Hz frequency and 119.3 mV amplitude) with the origin already explained above (as detailed in

Figure 23).

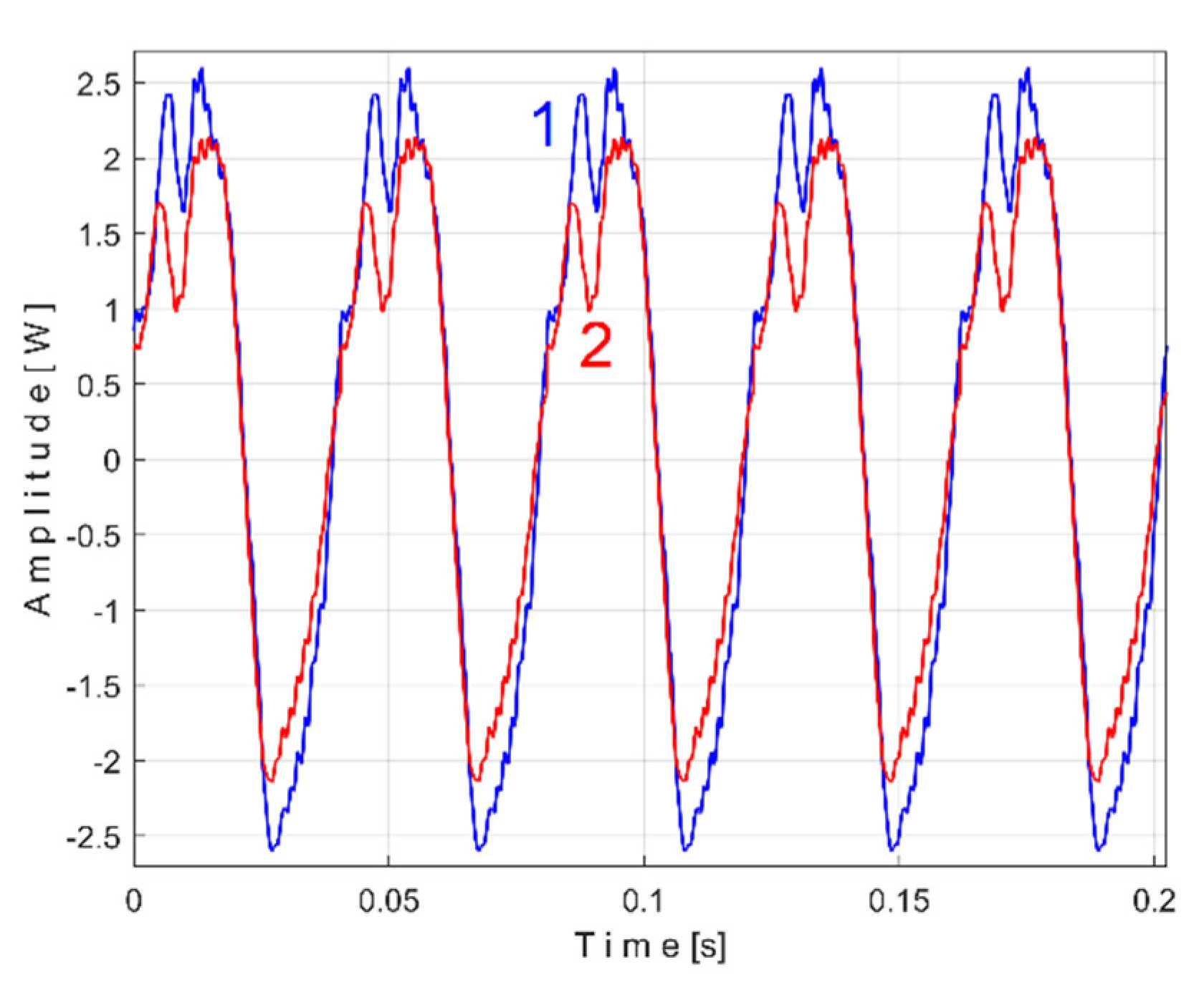

Even if the vibration description signal (

Vs, as

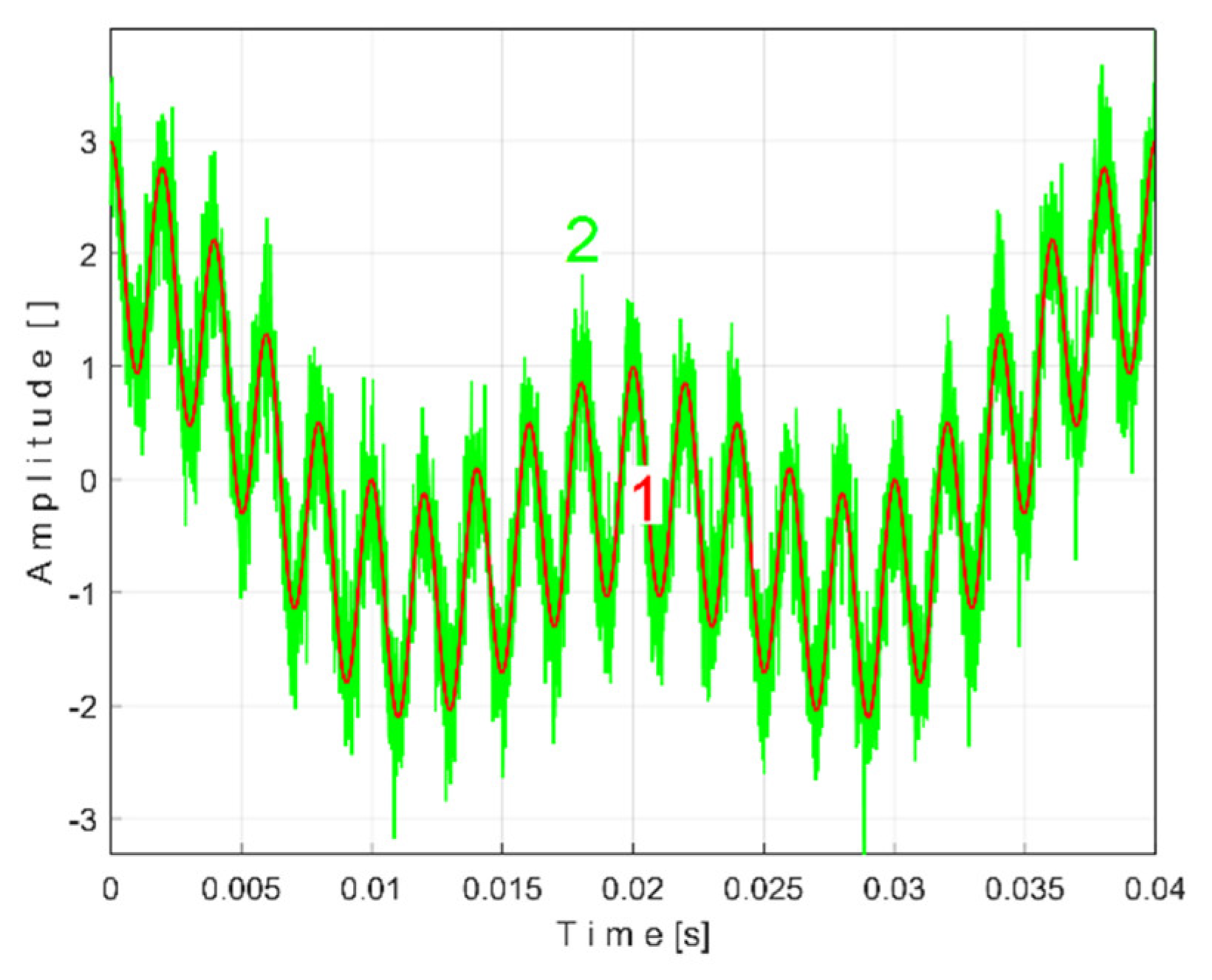

sV) contains the beat phenomenon and even if there is a large dominant VPSC (with D as fundamental), the patterns obtained by AMSSRTI are of interest for monitoring. Related by the behavior of first flat belt,

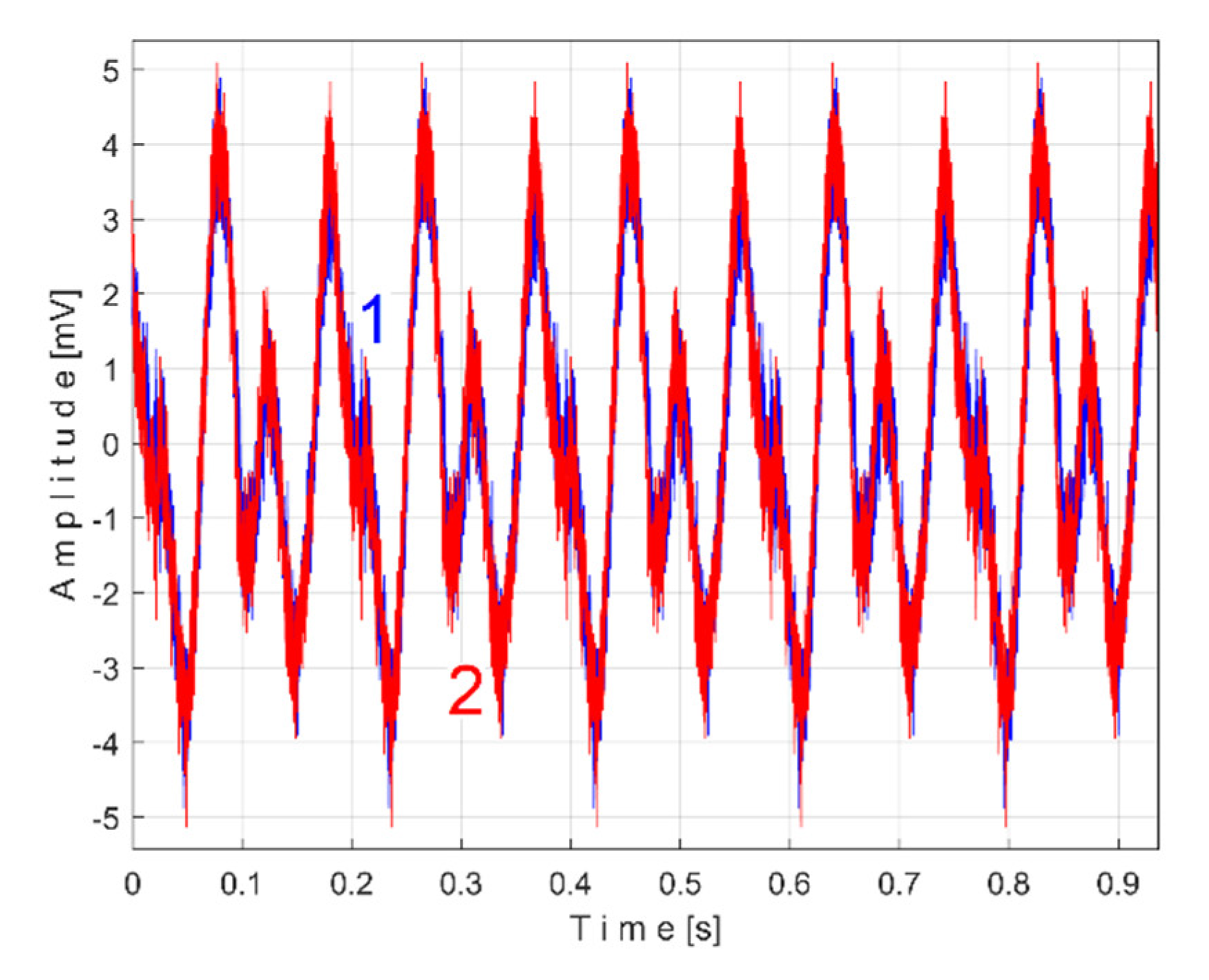

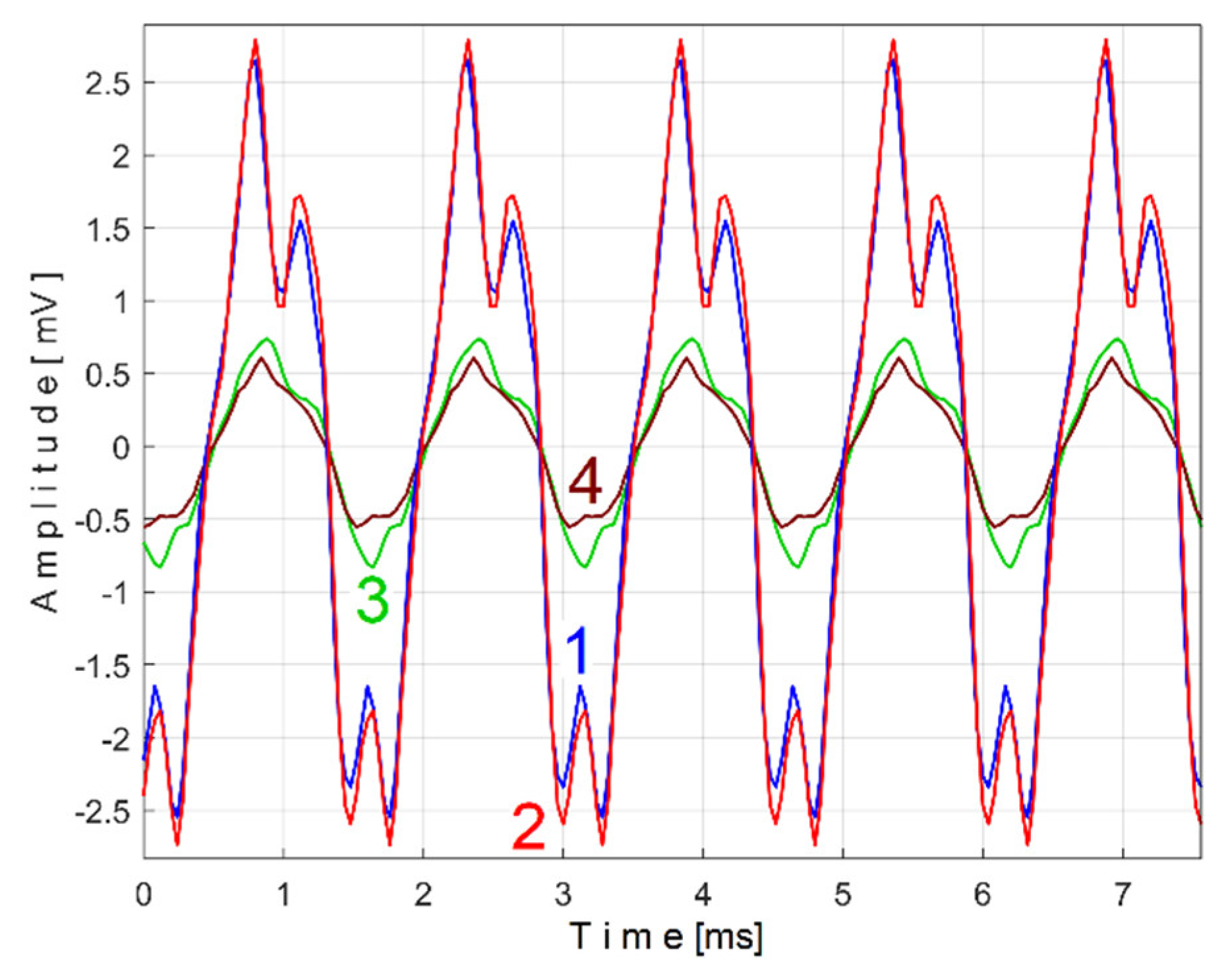

Figure 25 shows the superimposed extended patterns

sVTAe5a (curve 1,

m = 533 for almost 2.5 Ms at the beginning of

sV) and

sVTAe5b (curve 2,

m = 530 for almost next 2.5 Ms of

sV). We found that the average frequency

fVA (or period

TVA= 1/fVA) to consider in AMSSRTI for each extended pattern (whose which produces maximum peak-to-peak amplitude of the pattern) is slightly different:

fVAa =

5.33736 Hz for

sVTAe5a and

fVAb =

5.34151 Hz for

sVTAe5b. As a first approach, since the two patterns appear to be strongly affected by noise, they are plotted in

Figure 25 after a numerical low-pass filtering (using a moving average filter with 100 samples in the average). The sample at the beginning of the

sV sequence from which the second extended pattern (

sVTAe5b) has been deduced (almost

pa/2) is conveniently changed to obtain the most correct possible overlap of the two patterns.

As can be seen on

Figure 25, there are sufficient similarities between the two patterns (despite the relatively long durations between the sequences from which they were derived, almost 100 s) to prove the validity of this resource for describing the condition of the belt using AMSSRTI of vibration signal

sV. It should be noted that in the patterns of this flat belt, the fundamental A has a low amplitude (due to the low sensitivity of the sensor at low frequency), but there are some harmonics with higher amplitudes. It is interesting to highlight the resources offered by the unfiltered time-domain representation of these two patterns, shown in

Figure 26, where there are still obvious similarities between. We propose to realize the extension of one of the patterns (e.g., for unfiltered

sVTAe5b) to several periods (e.g., 50 periods, with 234,000 samples), as

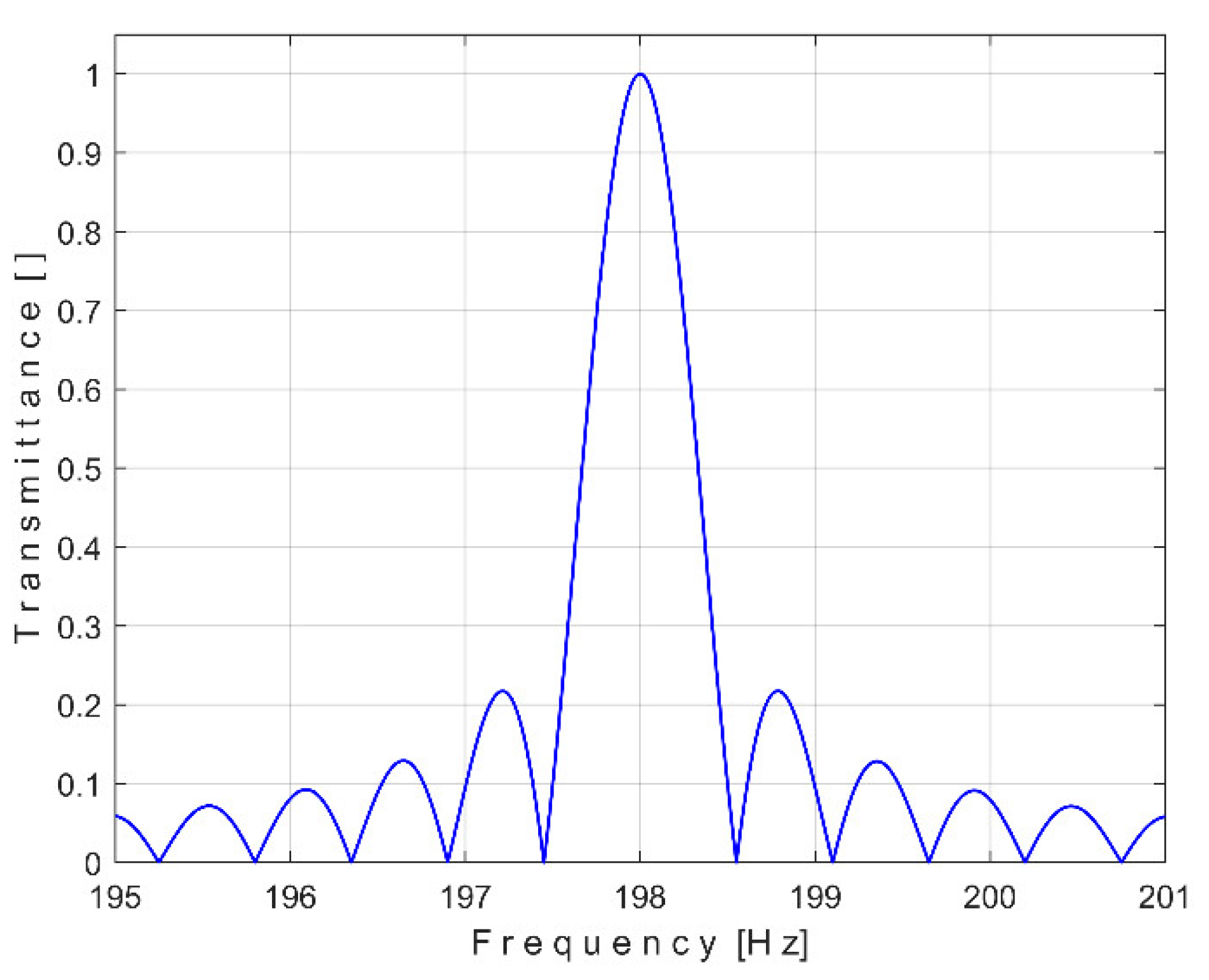

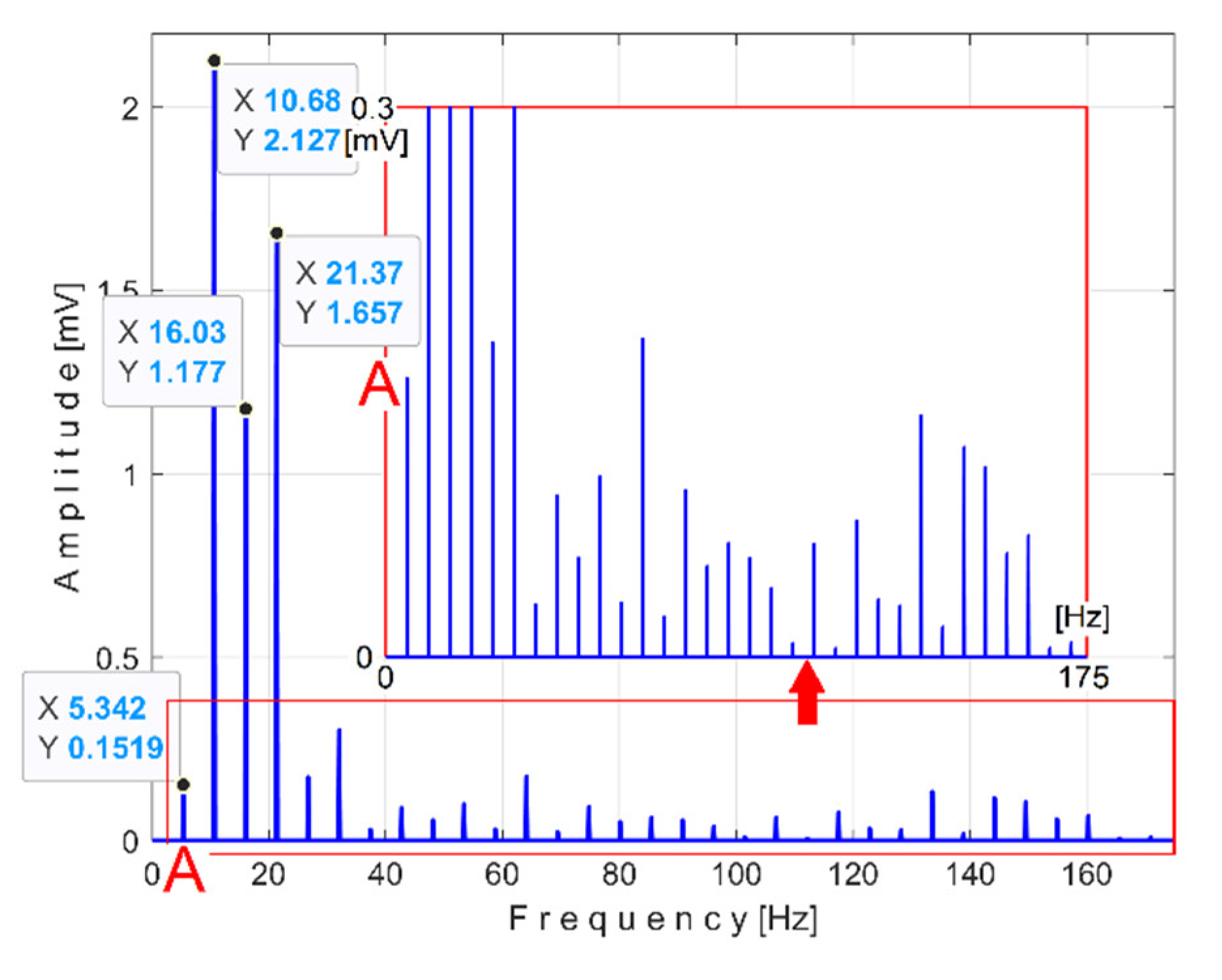

sVTAe50b. The partial FFT spectrum of this pattern (in the range 0 ÷ 175 Hz) is shown in

Figure 27. This figure also shows a zoomed-in detail of this partial spectrum (the same frequency range). This extension of the pattern was necessary to achieve high frequency resolution of the FFT spectrum.

First remark related by

Figure 27: the appearance of the FFT spectrum proves that there is no noise in the extended pattern

sVTAe50b (so neither in unfiltered

sVTAe5a and

sVTAe5b patterns). In addition, this signal is strictly deterministic, being defined as the sum of strictly harmonically correlated components with frequency spacing exactly equal to the value of

fVAb.

This is another strong argument in favor of the usefulness of AMSSRTI for describing the state of a mechanical component of the mechanical system under investigation. The spectral content highlighted here in the case of the first belt vibration pattern was not observed in the case of the active electrical power pattern (

Figure 26 compared to

Figure 25) because this power is defined by numerical low pass filtering of the instantaneous power.

It is very important to note that, in the same way, for all the patterns presented above (in the time-domain representation of the variable part of the active electrical power) it is possible to characterize them by means of the FFT spectrum of the extended patterns. Both variants of the extended pattern (filtered and unfiltered) can be used to monitor the condition of a rotating MC. The filtered version has the advantage of a quick estimation of the condition (e.g., by comparison with a standard pattern).

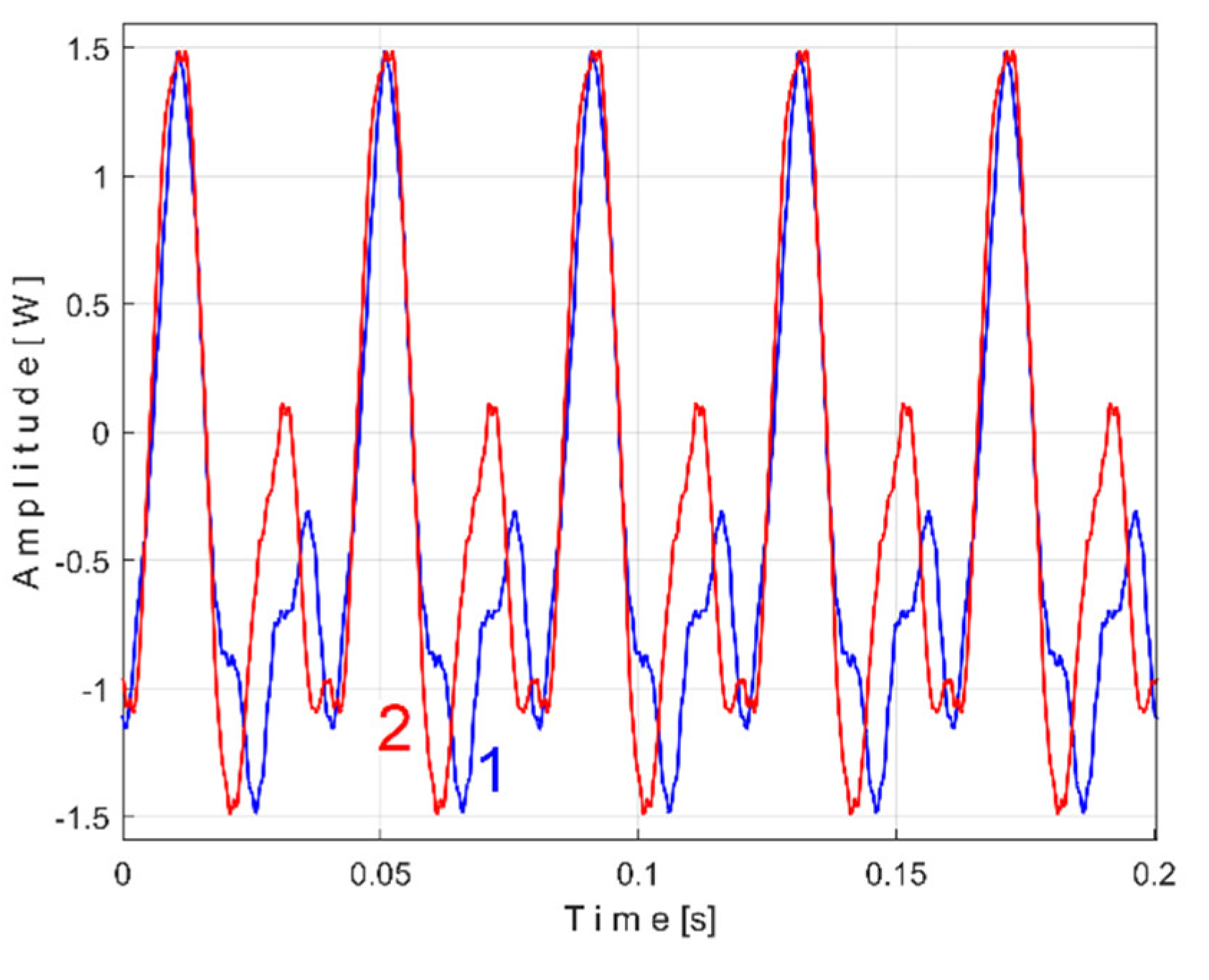

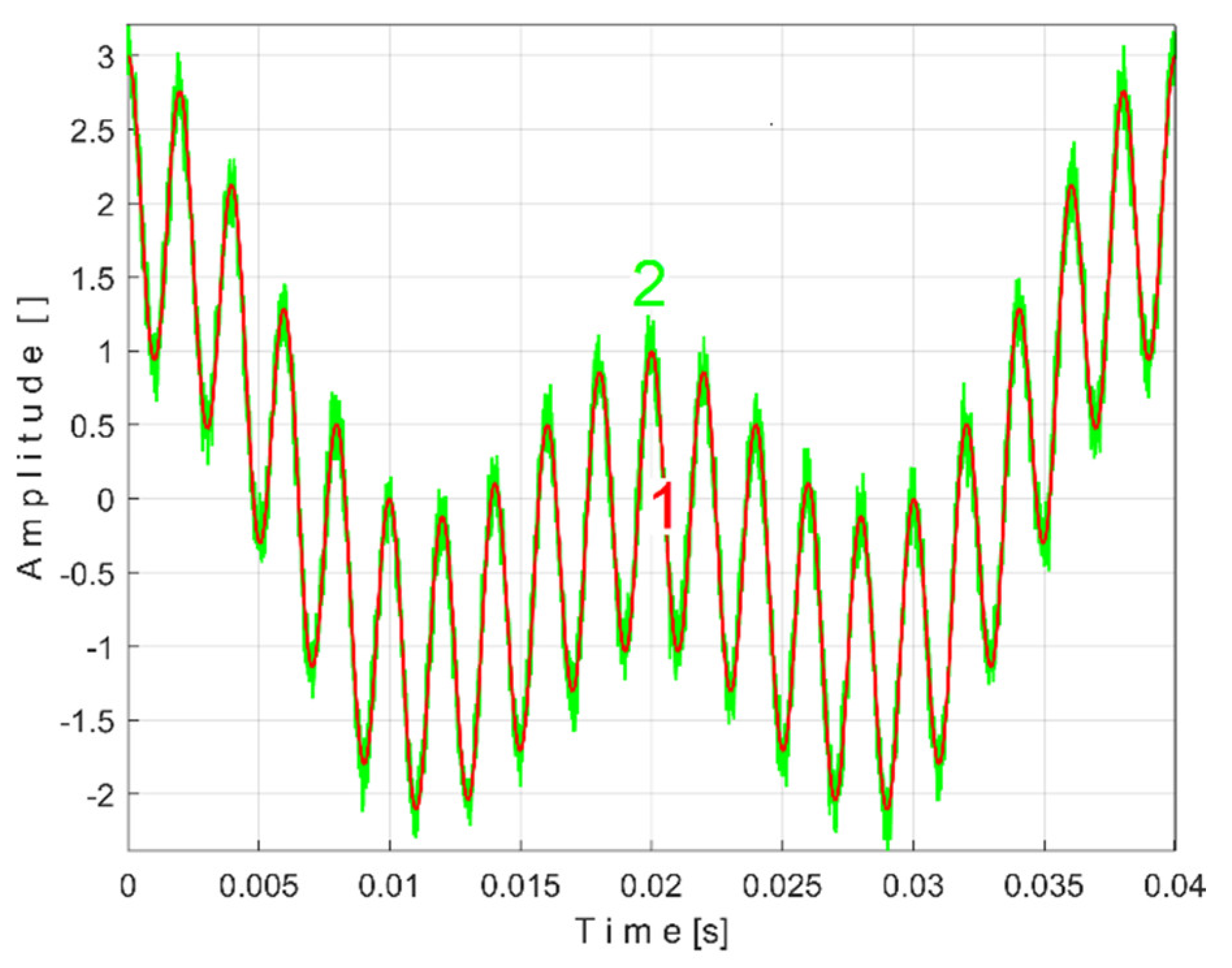

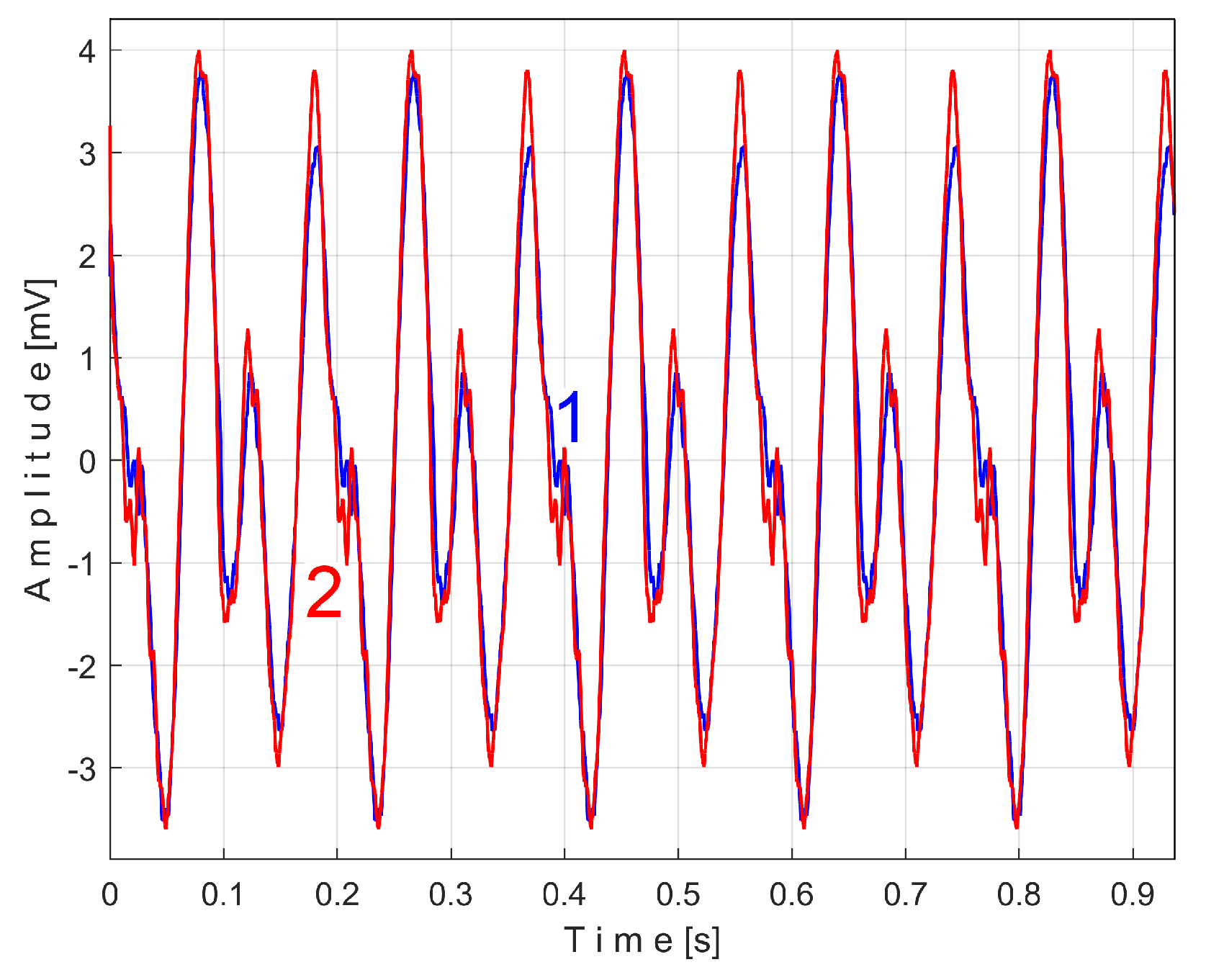

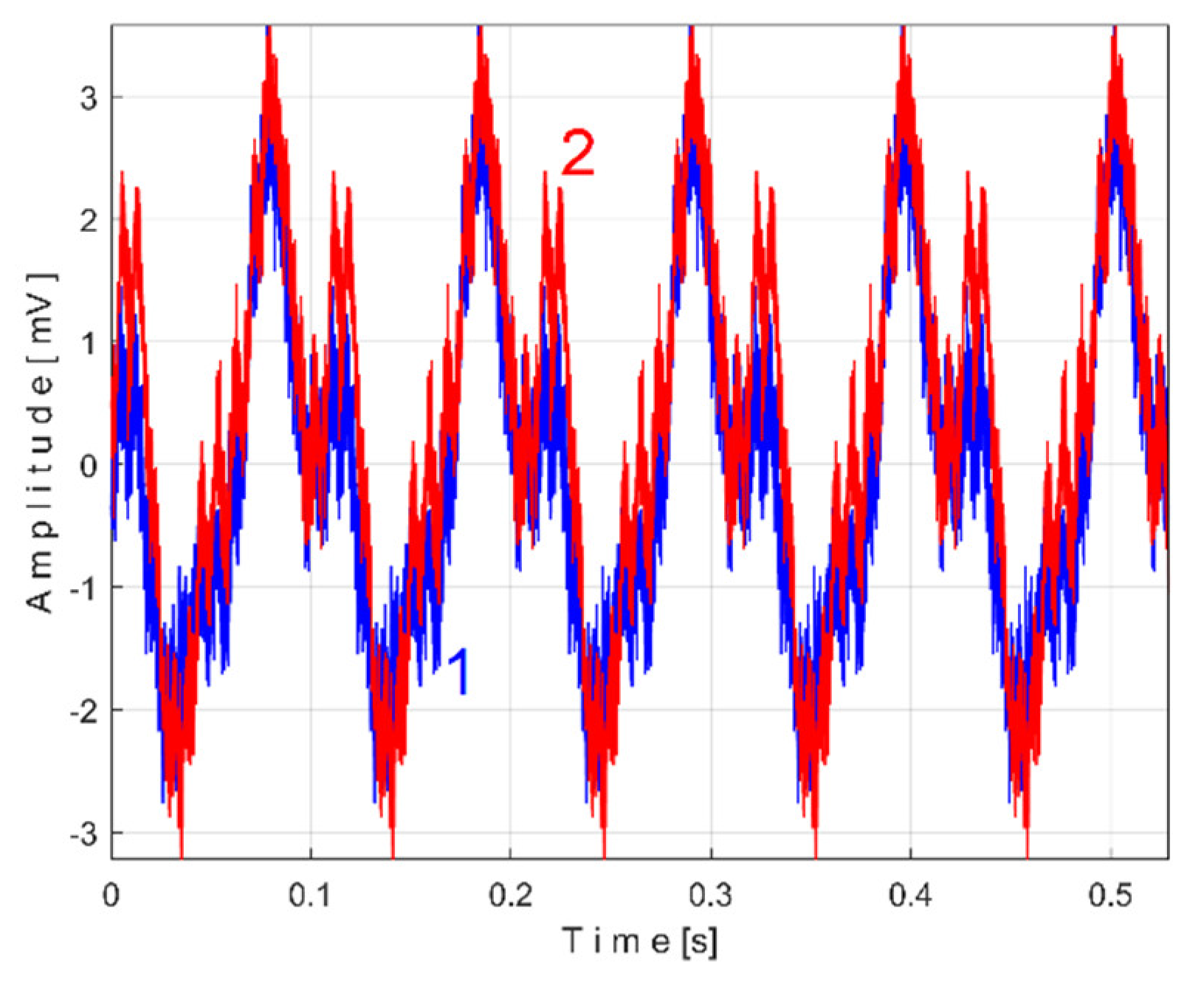

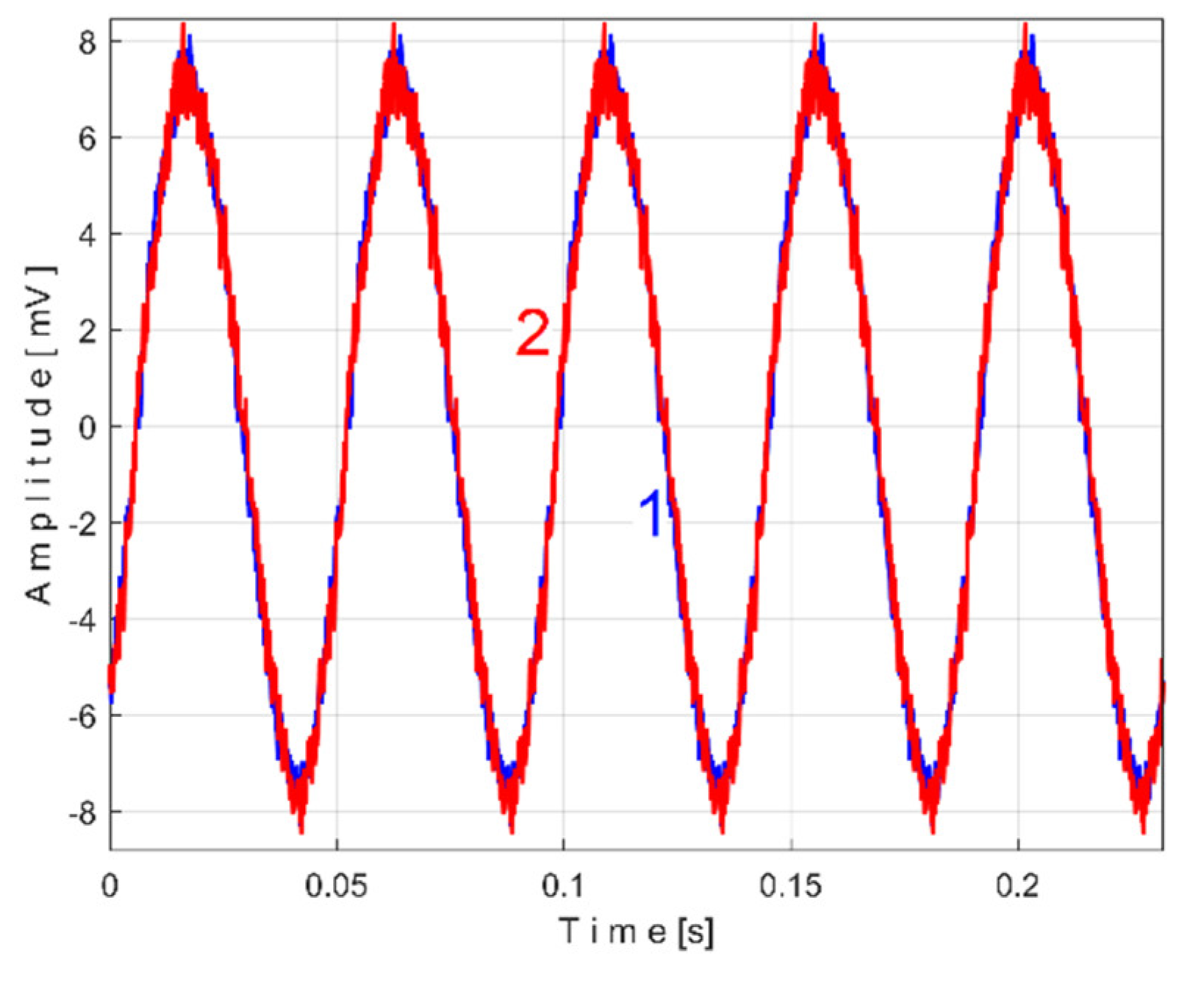

Related by the behavior of second flat belt,

Figure 28 shows the superimposed extended patterns

sVTBe5a (curve 1,

m = 935 for almost 2.5 Ms at the beginning of

sV) and

sVTBe5b (curve 2,

m = 935 for almost next 2.5 Ms samples of

sV). The average frequency

fVB (or period

TVB= 1/fVB) to consider in AMSSRTI for each extended pattern (which produces maximum peak-to-peak amplitude of the pattern) is again slightly different:

fVBa =

9.4525 Hz for

sVTAe5a and

fVBb =

9.4596 Hz for

sVTAe5b.

Figure 29 shows the same extended patterns treated with numerical low-pass filtering, using a moving average filter (with 30 samples in the average).

There are certain similarities between the filtered patterns, but also differences, probably due to the change in temperature of the belt during operation. It should be noted that the flat belt 2 introduces greater peak-to-peak variation in the active electrical power pattern compared to flat belt 1 (see

Figure 18 and

Figure 15). In the description of pattern from vibration, the flat belt 2 introduces less variation than belt 1 (see

Figure 29 and

Figure 25).

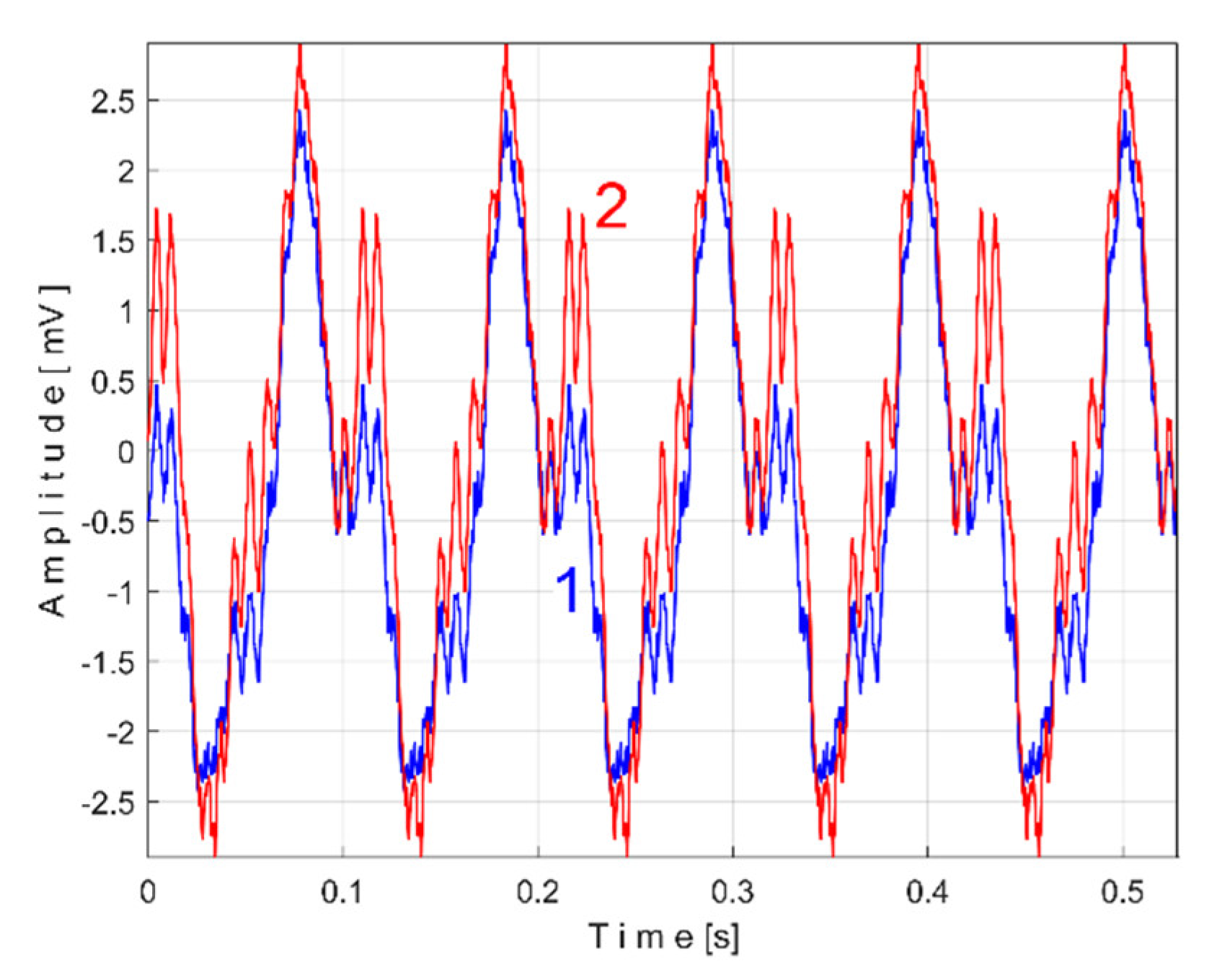

Figure 30 shows the superimposed extended patterns generated by the shaft II:

sVTCe5a (curve 1,

m = 1365 for almost 2.5 Ms at the beginning of

sV, with

fVCa =

13.75399 Hz) and

sVTCe5b (curve 2,

m = 1365 for almost next 2.5 Ms samples of

sV, with

fVCb =

13.76565 Hz).

Figure 31 shows the same extended patterns treated with numerical low-pass filtering, using a double moving average filter (with 37 and 50 samples in the average).

An examination can now be made of the components of one of the unfiltered patterns in

Figure 30 (e.g.,

sVTCe5b). Using the

Curve Fitting Tool application from Matlab, an approximation of this pattern has been identified based on the first two most representative sinusoidal components. This approximation -labeled

sVTCe5b2c- is described as:

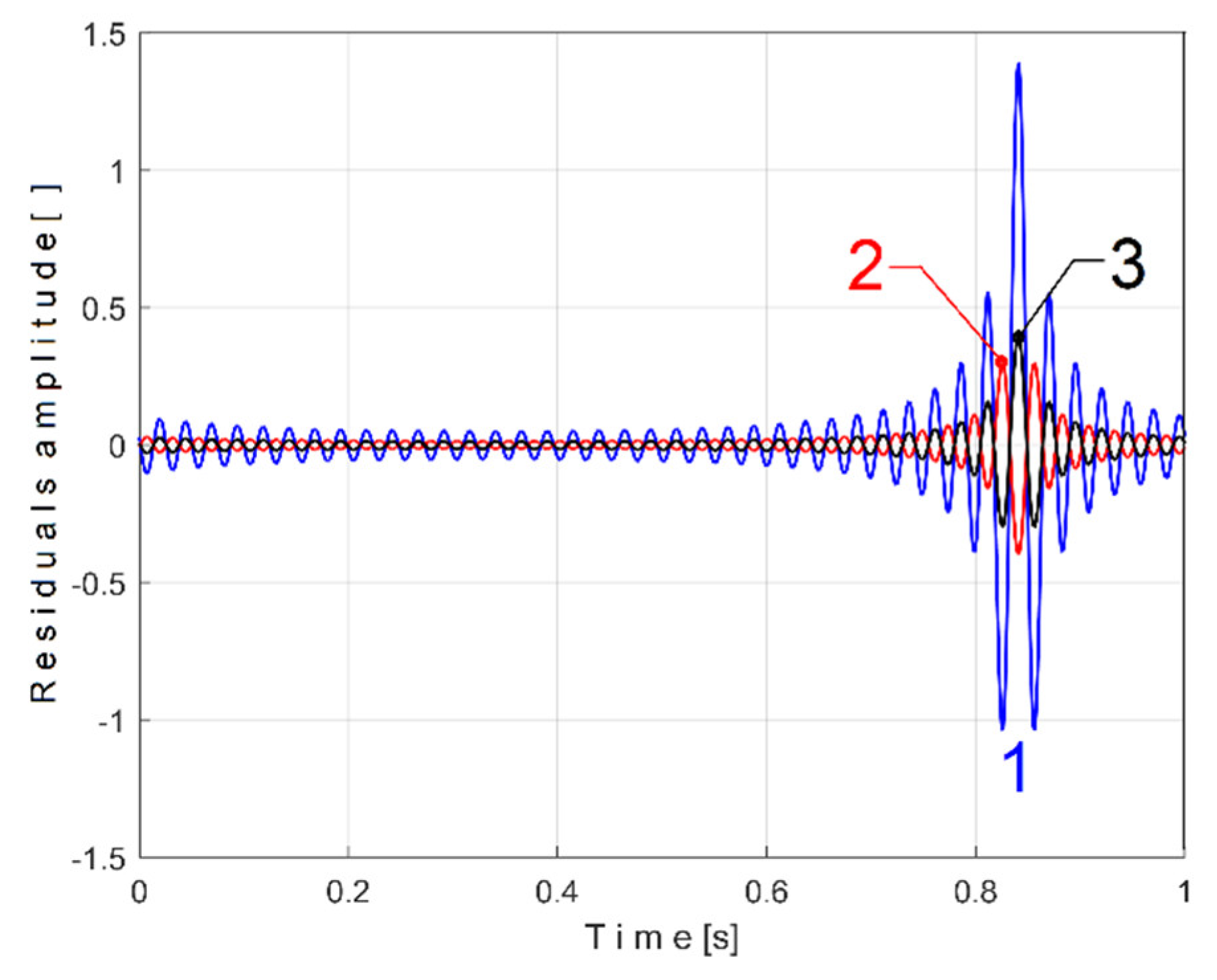

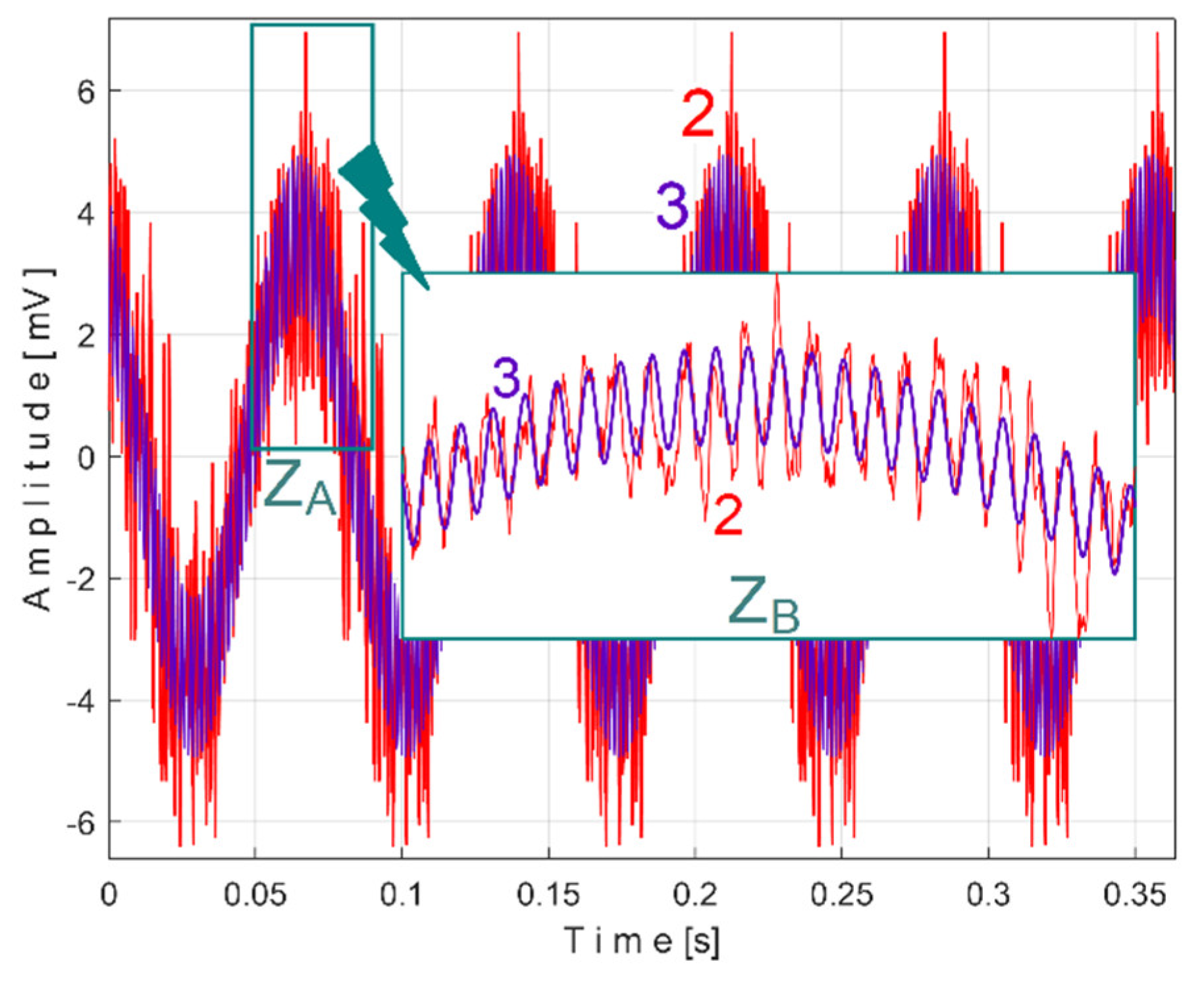

Figure 32 shows these two superimposed patterns:

sVTCe5b pattern as curve 2 (already shown in

Figure 30), and

sVTCe5b2c as curve 3, mathematically described by Eq. (7).

A detail from zone ZA illustrating the fit of the two curves is magnified in region ZB.

As expected, the angular frequency of the first component, or fundamental (as ω1 = 86.57 rad/s), is related to the frequency fVCb (with 2·π·fVCb ≈ ω1, so 86.4921 rad/s≈ 86.57 rad/s). The AMSSRTI ensure that the second component of sVTCe5b2c from Eq. (7) (with angular frequency ω2= 4152 rad/s) is necessarily harmonically correlated with the fundamental. This is totally confirmed, because: ω2/ω1 = 47,9611 ≈ 48. This very small difference is explained by the approximations of the fitting procedure in finding the values of the constants from Eq. (7).

Obviously, this second component in Eq. (7) must correspond to a vibratory phenomenon. The most plausible explanation for the origin of this phenomenon is that in

Figure 11, a 48-toothed gearwheel is mounted on shaft II in free meshing (not transmitting mechanical power). The second component in Eq. (7) is generated by the meshing sequence of the teeth of this wheel as a vibration-generating phenomenon with a frequency 48 times higher than the rotational frequency of the shaft II.

It is clear that this second component of Eq. (7) is always present in the vibration signal

sV. Moreover, it should be emphasized by AMSSRTI applied to signal

sV, related by a variable component with period

TVC48=TVC/48. The extended pattern of this component on five periods

TVC48 (as

sVTC48e5a pattern) is shown as curve 1 in

Figure 33 (

m = 3250, on first 4.94 s of the signal

sV, with the best approximation of the frequency at this variable component

fVC48a = 660.045986 Hz). The same analysis by AMSSRTI was performed on a new

sV signal sequence starting at the 100th second (

m = 3250 with the best approximation of the frequency at this variable component

fVC48b = 660.53362 Hz). An extended pattern (

sVTC48e5b) was generated, represented by curve 2 in

Figure 33 (moved appropriately to get the best overlap with curve 1). The similarity of these patterns is more than obvious, even though they are described with a small number of samples (190).

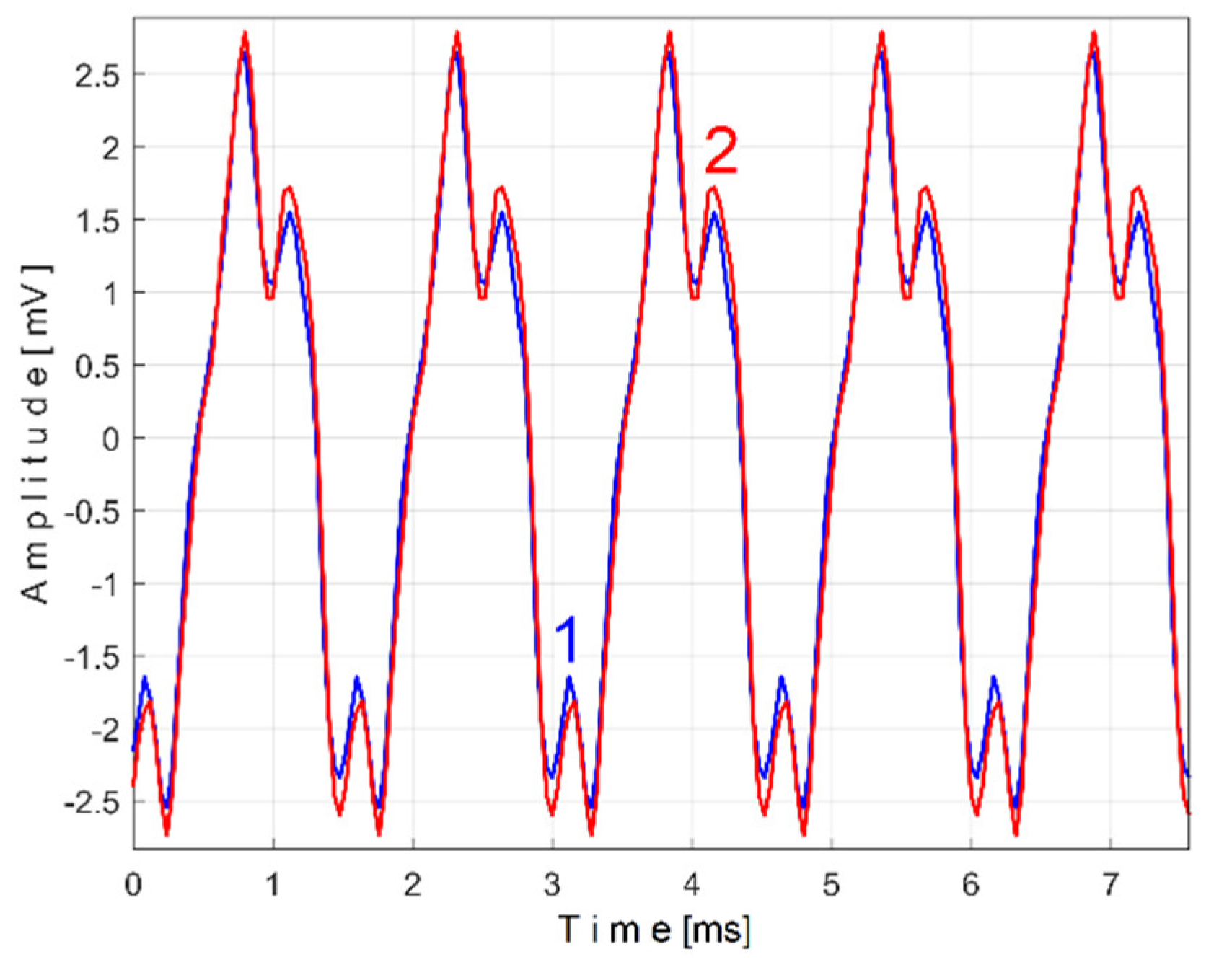

Similarly, AMSSRTI can be used to determine if there is a variable component induced by the 58 -toothed gearwheel placed on shaft II, as a toothed wheel that transmits mechanical power. The extended pattern of this component on five periods

TVC58 (as

sVTC58e5a pattern) is shown as curve 1 in

Figure 34 (

m = 3250, on first 4.04 s of the signal

sV, with the best approximation of the frequency at this variable component

fVC58a = 797.5646 Hz ≈

58· fVCa = 58·13.75399 Hz = 797.73142 Hz). A new extended pattern of this component on five periods

TVC58 (as

sVTC58e5b pattern) is shown as curve 2 in

Figure 34 (

m = 3250, on 4.04 s of the signal

sV, starting with the 100th second, with the best approximation of the frequency at this variable component

fVC58b = 798.1551Hz ≈

58·

fVCb = 58·13.76565 Hz = 798.4077 Hz).

Again, a good similarity of the two patterns from

Figure 34 (each of them described with 155 samples) was obtained. This proves that the vibrations induced by this toothed wheel occur systematically, and that the AMSSRTI is obviously a good option in gearbox condition research. Increasing the sampling rate of the signal

sV increases the number of samples of the patterns from

Figure 33 and

Figure 34.

As the speed of the electromotor driving the gearbox increases slightly over time (due to the decrease of mechanical load, through the effect of the viscosity decreasing of the lubricating oil), all the frequencies of the components studied so far increase slightly over time. Therefore it should be mentioned that the shape of the patterns generated by AMSSRTI depends relatively strong on the value of

m, especially in the case of high frequency components (e.g., for

TVC48 periodic component with the patterns already shown in

Figure 33 for

m = 3250).

Figure 35 reproduces these two patterns (curves 1 and 2) but also the extended patterns resulting from AMSSRTI with the maximum possible value for

m (curves 3 and 4).

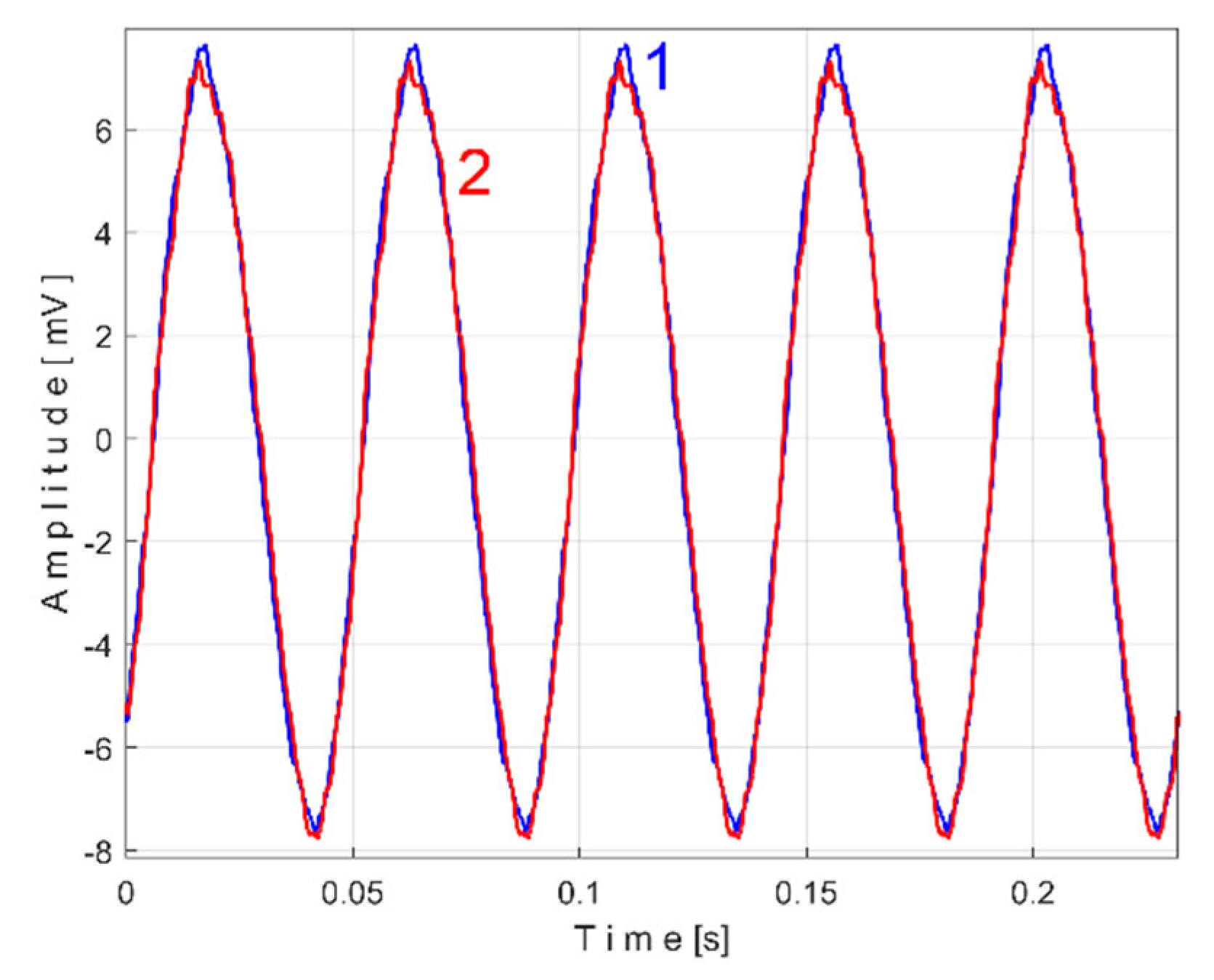

Figure 36 shows the superimposed extended patterns generated by the shaft I, for

m = 2155, as

sVTDe5a (curve 1, for almost 2.5 Ms at the beginning of

sV, with

fVDa =

21.56087 Hz) and

sVTDe5b (curve 2, for almost the next 2.5 Ms samples of

sV, with

fVDb =

21.57886 Hz).

Figure 37 shows the same extended patterns treated with numerical low-pass filtering, using a moving average filter (with 30 samples in the average). It should be noted that the two filtered extended patterns derived from the vibration analysis by AMSSRTI are more similar for this shaft than for any flat belt previously presented (belt 1 in

Figure 25 and belt 2 in

Figure 29). Similar studies can be performed on the periodic components associated with the rotation of the shaft I and spindle.

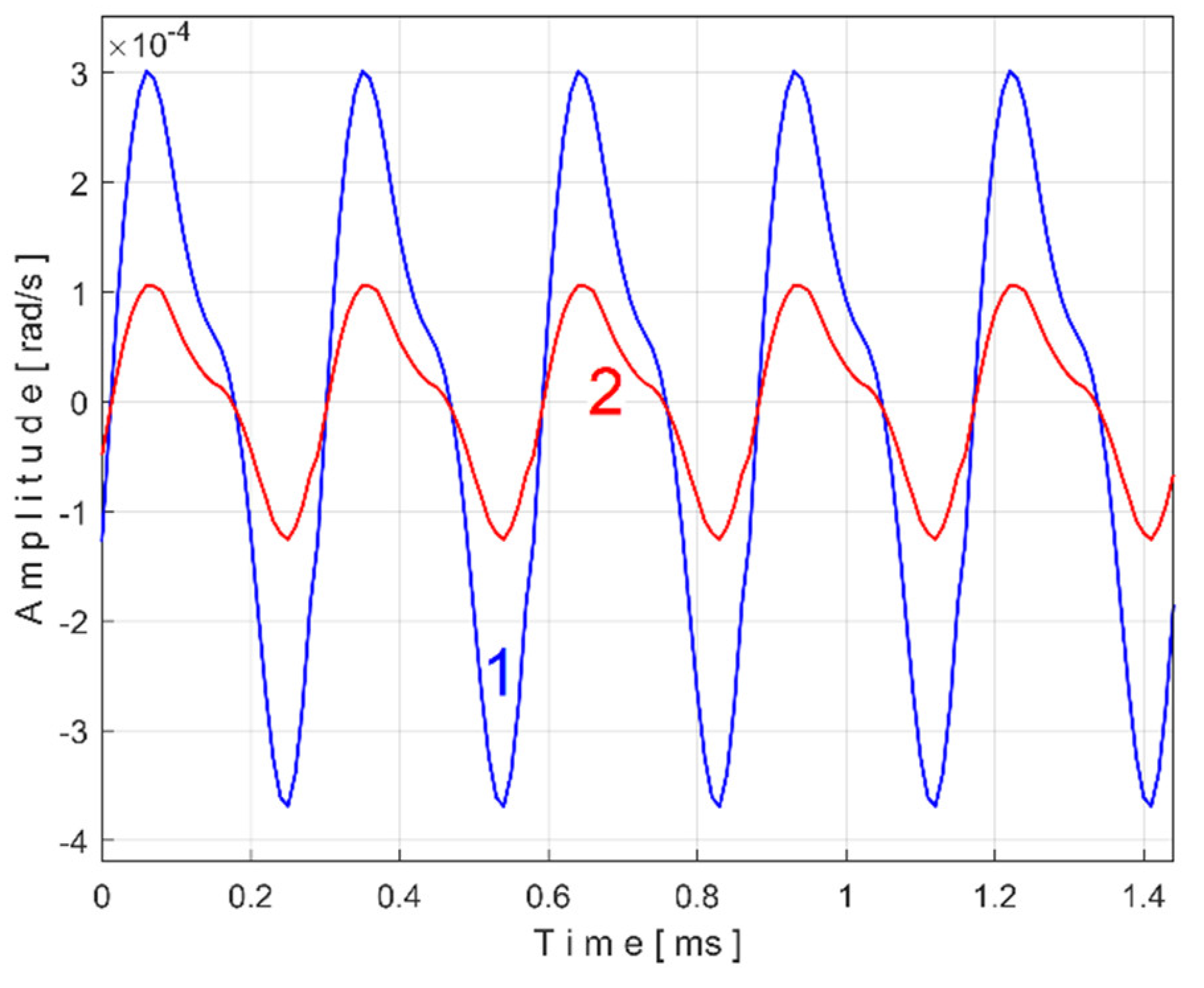

3.3. Some Results Obtained by Analyzing Instantaneous Angular Speed Using AMSSRTI

An instantaneous angular speed (IAS) sensor (as IASS) was placed in the jaw chuck of the spindle (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). This sensor is actually a stepper motor that plays the role of a two-phase, 50-pole AC generator [

53]. At relatively high IAS, this sensor generates two AC signals (equal amplitudes, 90 degrees out of phase) with 50 periods per revolution. These signals are processed appropriately in order to produce IAS, at the same sampling rate, using an interesting approach, presented in [

56]. This approach is based on determining the angle of rotation of the sensor rotor and the numerical derivative of this angle with respect to time. The time-domain representation of the IAS during an identical steady state regime considered previously (but shorter, with duration of only 10 s and a sampling rate of 100,000 s

-1) is shown in

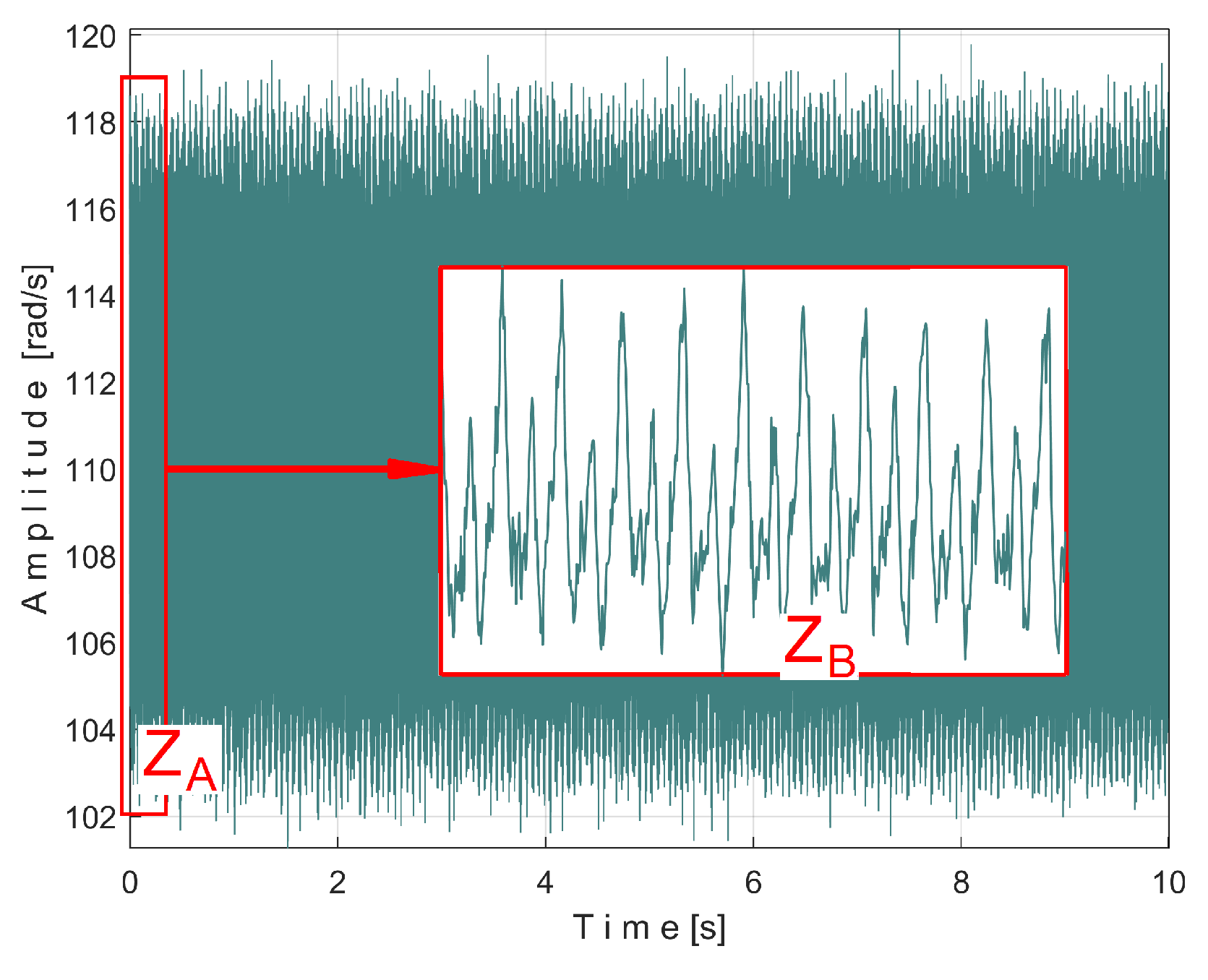

Figure 38.

A detail from zone ZA, at the beginning of IAS (with 587 samples, during 5.87 ms) is shown magnified in zone ZB. A significant variability of the IAS signal is observed (as peak-to-peak amplitude, with a maximum value of 18.87 rad/s) around the mean value of 109.47 rad/s, corresponding to a mean rotation frequency of 109.47/2/π=17.4227 Hz. This high variability is due to the fact that this AC generator has mechanical and electrical design imperfections and introduces a variable component related to these imperfections, which is greatly amplified by numerical derivation.

The fundamental frequency (period) of this variable component is equal to the rotational frequency (period) of the spindle. In order to use AMSSRTI properly (here with a smaller allowed values for

m, because the IAS sequence is short), this variable component should be removed somehow, e.g., using a moving average filter with the number of samples in the average equal to the number of samples per spindle rotation period (here 5,739 samples). This means that the AMSSRTI pattern generated by the spindle cannot be obtained.

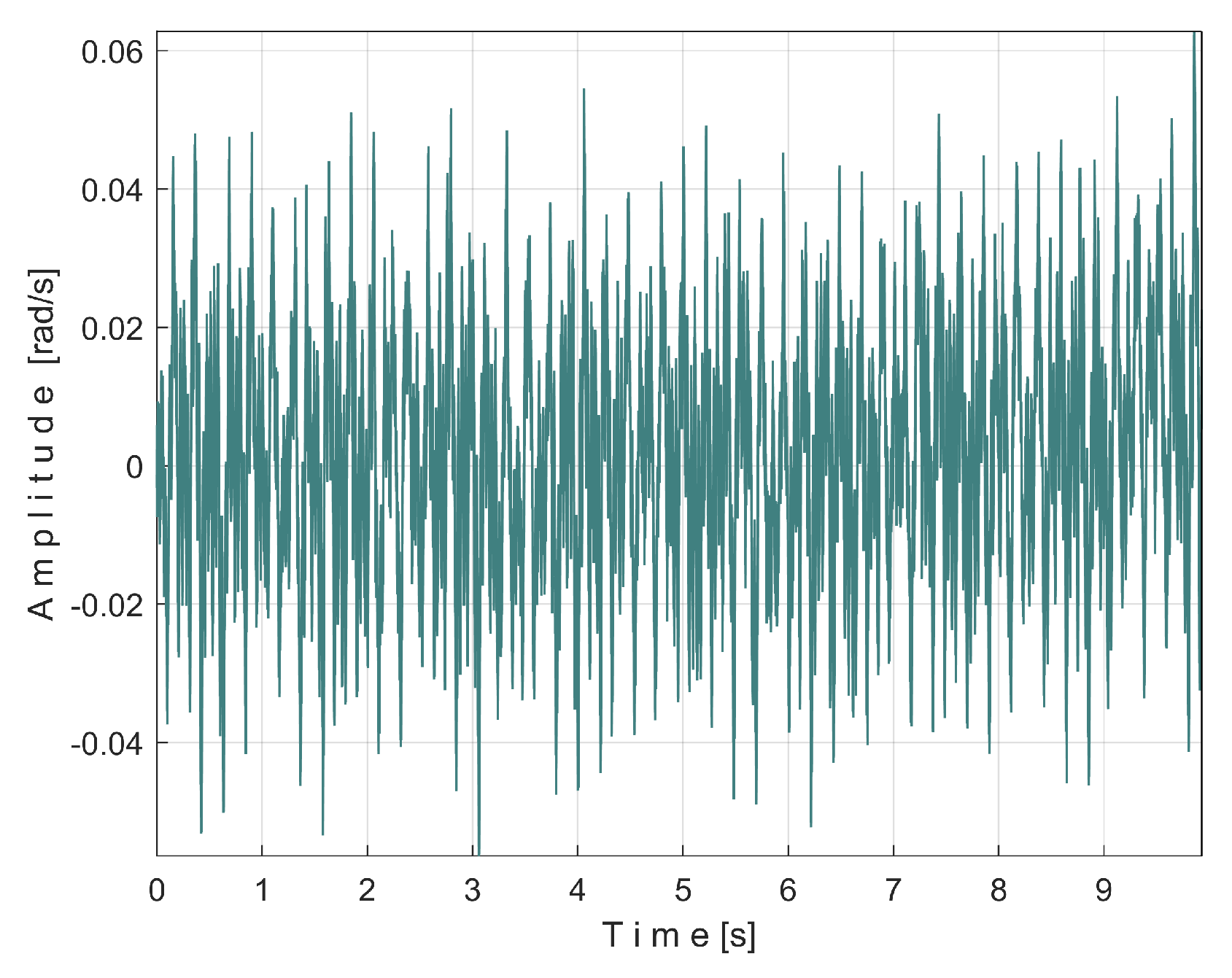

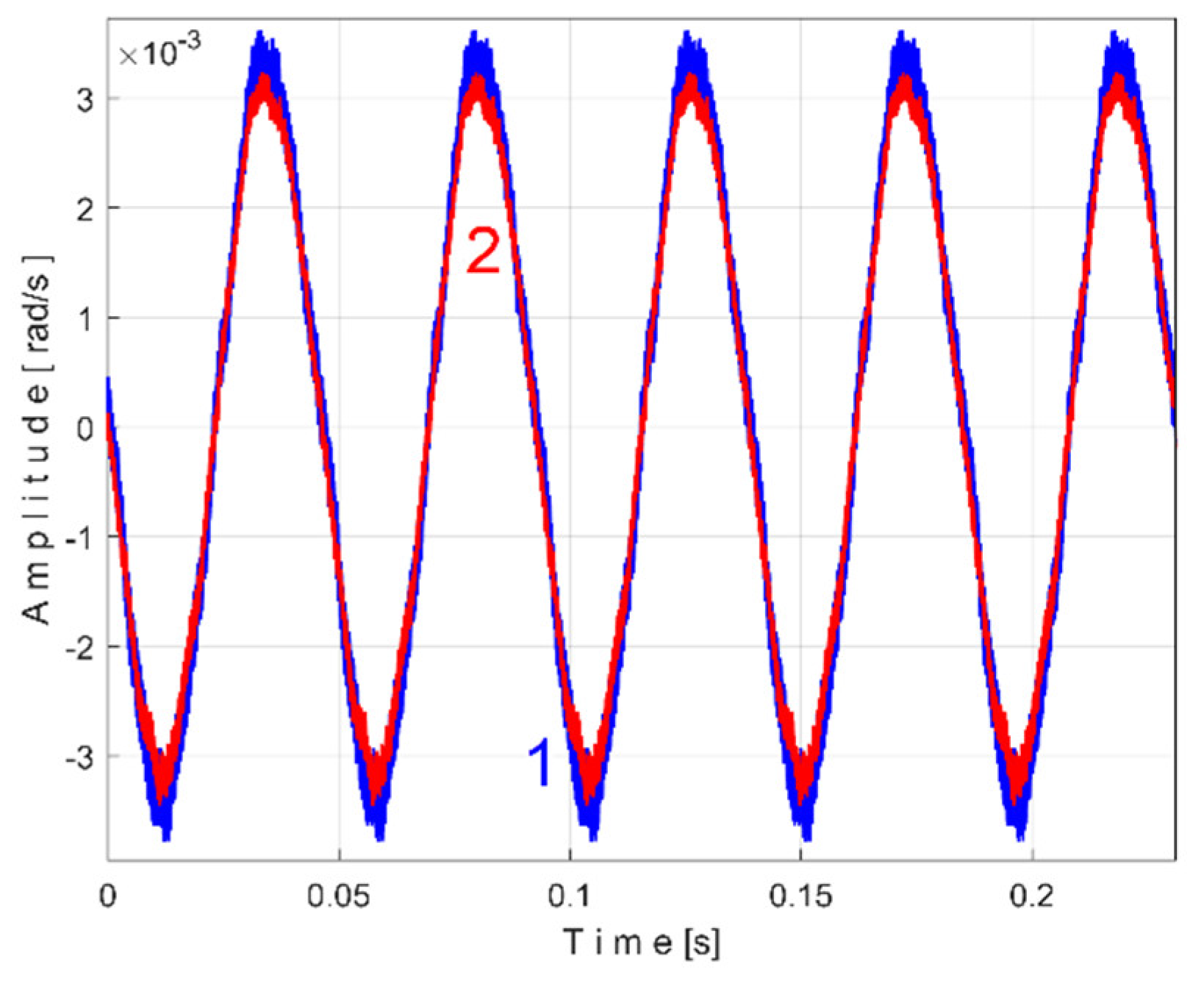

Figure 39 shows the variable part of the filtered IAS, seen from here onwards as signal

sI.

Of course, all other components of the signal sI are affected by this filtering (some with diminished amplitude, others being eliminated). However, some of them can still be revealed by AMSSRTI.

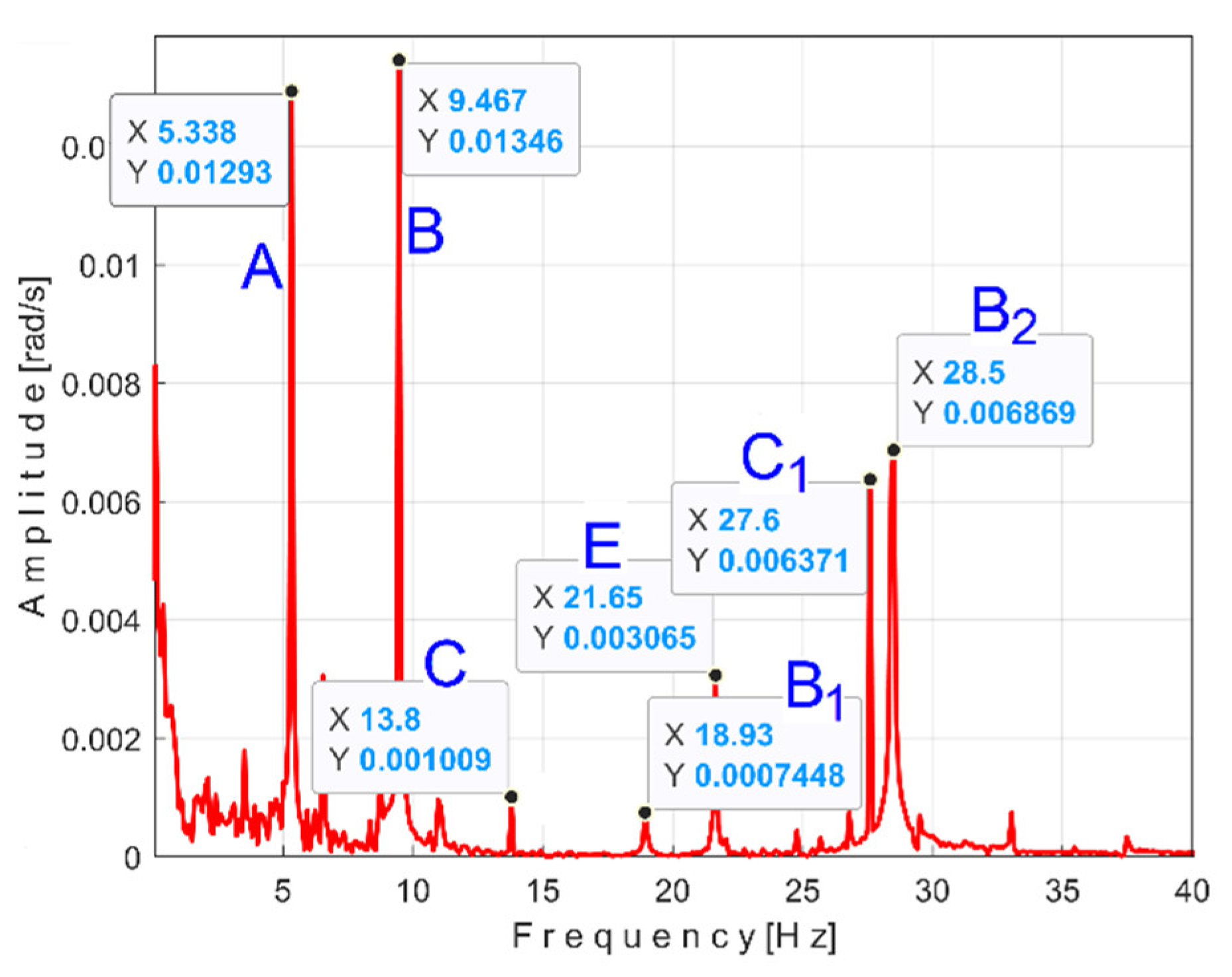

Figure 40 shows the partial FFT spectrum of the signal

sI (0÷40 Hz range, with 0.100715 Hz resolution).

Surprisingly, this spectrum contains the four fundamental (A, B, C and E) and some harmonics (B

1, B

2, C

1) of the PVSCs previously highlighted in the active electrical power spectrum (

Figure 14) and vibration description signal spectrum (

Figure 24). This is the first important argument in favor of using the signal

sI in condition monitoring using AMSSRTI. As clearly indicated, the fundamental of PVSC generated by the rotation of spindle in signal

sI (D in

Figure 14 and

Figure 24) was completely eliminated in the spectrum from

Figure 40 by due to an appropriate filtering of IAS signal.

In the same way as above, AMSSRTI can be used in signal processing of the signal sI to extract the extended patterns of these available variable components.

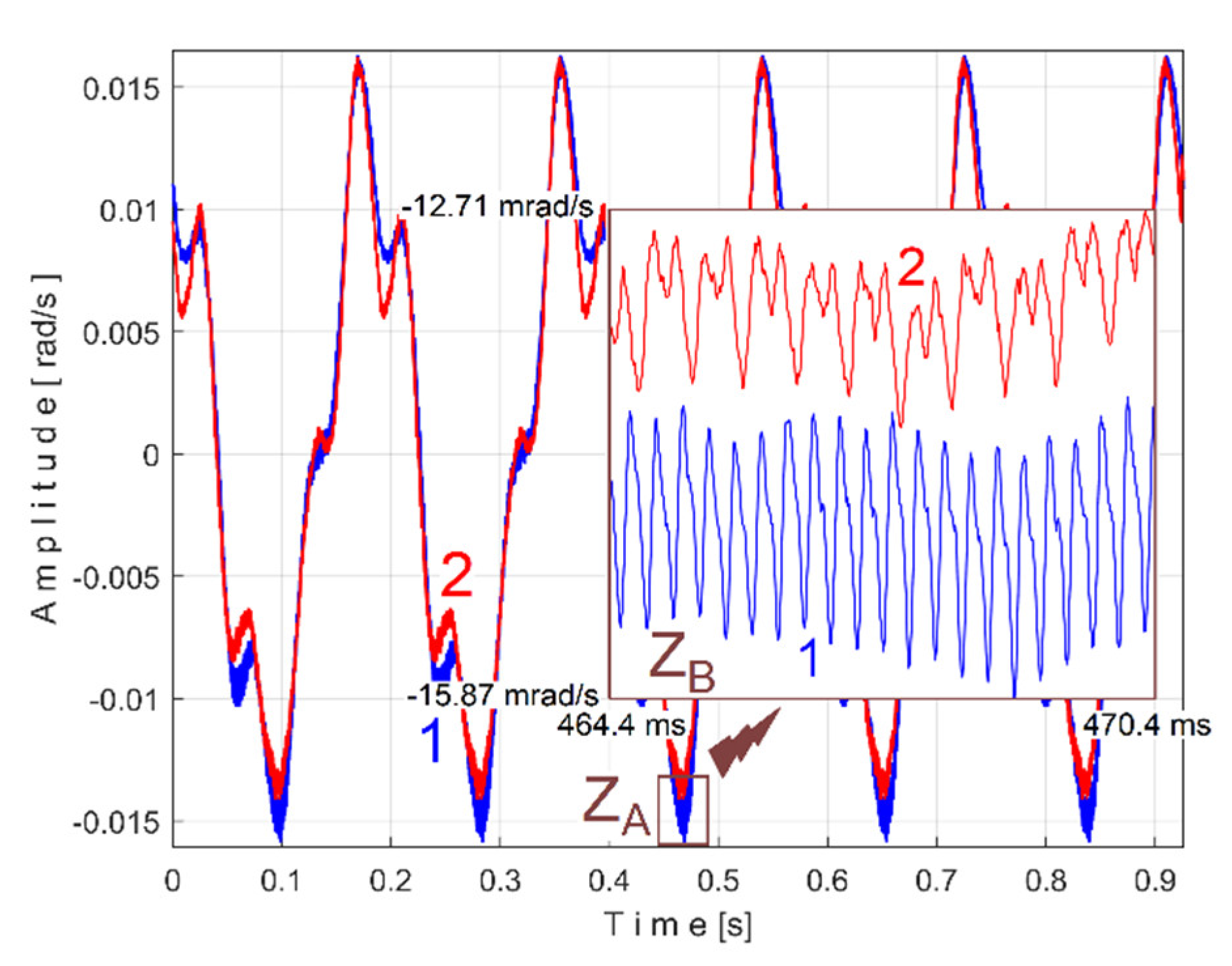

Related by the behavior of first flat belt mirrored in filtered signal

sI (with fundamental A in

Figure 40),

Figure 41 shows the superimposed AMSSRTI extended unfiltered patterns

sITAe5a (curve 1,

m = 25 on 467,075 samples at the beginning of

sI) and

sITAe5b (curve 2,

m = 25 for next 467,800 samples of

sI). The average frequency

fIA is slightly different for each pattern:

fIAa =

5.40021 Hz for

sITAe5a and

fIAb =

5.4107 Hz for

sITAe5b.

As expected, there is a good match between the two extended patterns. Surprisingly, the sI signal variation induced by belt 1 is detected and described by the IAS sensor (via AMSSRTI), even if this sensor is placed far away from this belt.

A detail in zone Z

A on

Figure 41 is magnified in zone Z

B. One can see here (especially with respect to the pattern

sITAe5a) the existence of a variable signal component, the origin of which will be explained later in the discussion about

Figure 42 and

Figure 43.

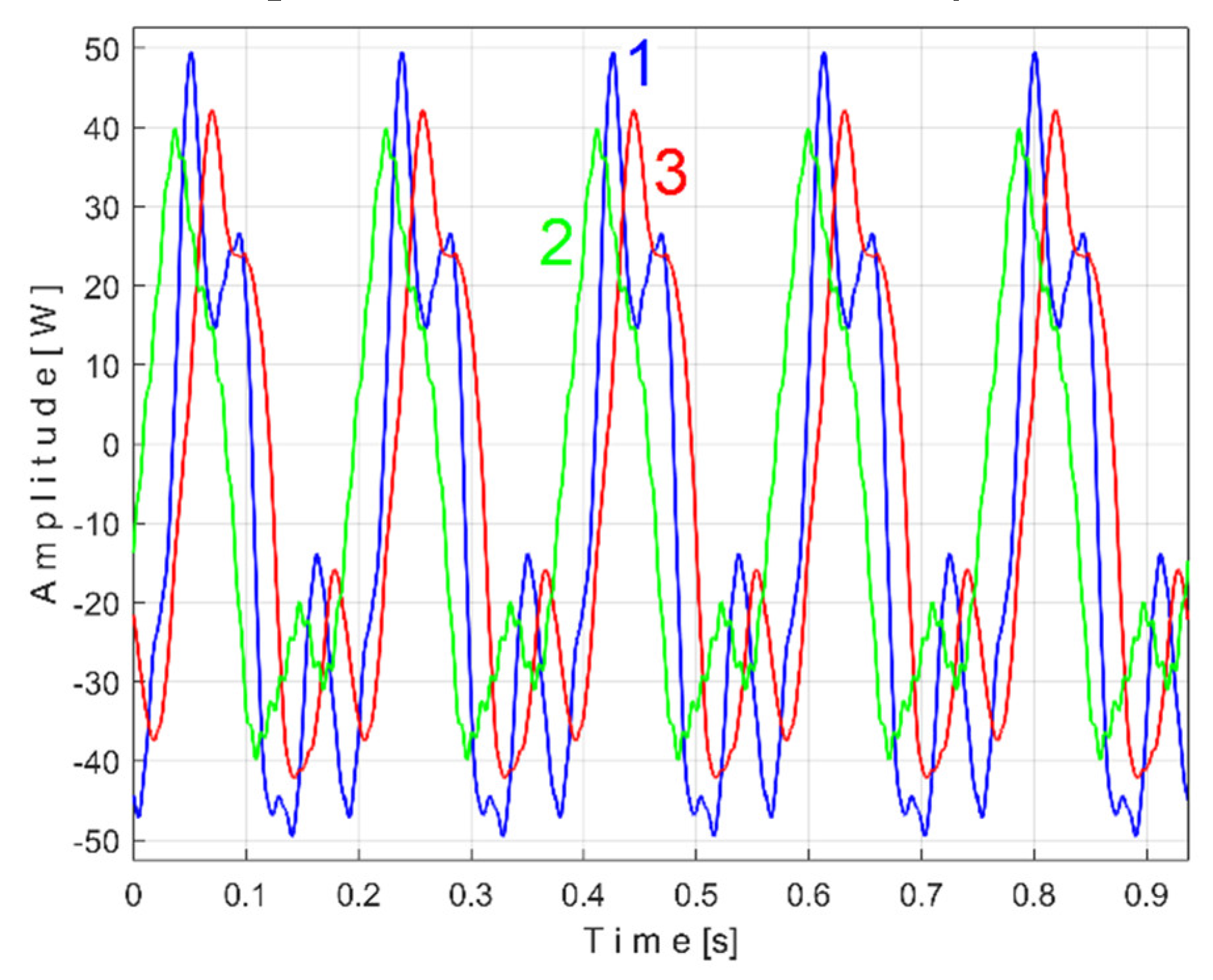

Related by the behavior of second flat belt mirrored in

sI (having the fundamental B in

Figure 40),

Figure 42 shows the superimposed extended unfiltered patterns

sITBe5a (curve 1,

m = 46 on 484,702 samples at the beginning of

sI) and

sITBe5b (curve 2,

m = 46 for next 484,702 samples of

sI). The average value of the frequency used in the AMSSRTI was

fIBa =

9.48999 Hz and

fIBb = 9.49061 Hz.

A detail from zone Z

A (with 370 samples, during 3.7 ms) is shown magnified in zone Z

B. This is an example of a distortion phenomenon of the AMSSRTI patterns (more evident in

sITBe5a compared with

sITBe5b), already anticipated in before in

Section 2 of this paper.

It should be noted that the PVSC generated by the spindle in the signal

sI has not been completely removed by the IAS filtering (only the D fundamental has been completely removed, as

Figure 40 shows that it is missing), some of its upper harmonics still remains in the signal

sI. It was found that the period of the 369th harmonic of the fundamental of the variable component generated by the second belt (as

TIBa369 = TIBa/369 or

TIBb369=

TIBb/369) is practically equal to the period of the 201st harmonic of the fundamental of the PVSC generated by the shaft (as

TIDa201 =TIDa/201 or

TIDb201 =TIDb/201), in other words

369·fIBa ≈201·fIda ≈ 3501.80 Hz or

369·fIBb ≈201·fIDb ≈ 3502.035 Hz. For this reason, the sinusoidal component with period

TIDa201 (or

TIDb201) appears in the extended AMSSRTI pattern

sITBe5a (or

sITBe5b) as false sinusoidal component

TIBa369 (or

TIBb369). Also in these AMSSRTI extended patterns appears any other sinusoidal component having the period

TIDa201/j ≈

TIBa369/j (or

TIDb201/j ≈

TIBb369/j).

Of course, it is possible to find the AMSSRTI extended patterns

sITB369e5a and

sITB369e5b of the false variable component with the fundamental with very small period

TIBa369 and

TIBa369 (or high frequencies as well). These extended patterns (having 145 samples) were each one determined on almost half of number of samples (495,900) from signal

sI (for

m=17,100) and shown in

Figure 43.

As can be clearly seen in

Figure 43, there are some similarities between these patterns (as shapes not as amplitudes), already found earlier in

Figure 42 as shown in region B. We discovered that these false signal variable components

TIDa201 and

TIDb201 also occur in the

sITAe5a and

sITAe5b extended patterns already revealed in

Figure 41 (highlighted in the region Z

B), as having

TIAa648 (or

TIAb648) as periods of the fundamental A.

Related by the behavior of shaft II mirrored in signal

sI (with fundamental C in

Figure 40),

Figure 44 shows the superimposed AMSSRTI extended unfiltered patterns

sITCe5a (curve 1,

m = 68 on 491,776 samples at the beginning of

sI) and

sITCe5b (curve 2,

m = 68 for next 491,776 samples of signal

sI). The average value of the frequency used in the AMSSRTI was

fICa =

13.826942 Hz and

fICb = 13.79066 Hz. Since there are ten periods on each extended pattern, it is obvious that the amplitude of the first harmonic (having period

TICa1 or

TICb1 described in

Figure 40 with the peak C

1) is much bigger than the fundamental (having the period

TICa or

TICb).

Related by the behavior of shaft I mirrored in signal

sI (with fundamental E in

Figure 40),

Figure 45 shows the superimposed AMSSRTI extended unfiltered patterns

sITEe5a (curve 1,

m = 106 on 489,720 samples at the beginning of

sI) and

sITEe5b (curve 2,

m = 106 for next 489,720 samples of

sI).

The average value of the frequency used in the AMSSRTI was

fIEa =

21.6422 Hz and

fIEb = 21.64315 Hz. In

Figure 44 and

Figure 45, false variable components also appear, as described earlier. Eliminating these false variable components in the AMSSRTI patterns requires a simple approach, such as determining their mathematical description (by curve fitting, as was done earlier in

Figure 16) and removing them from the AMSSRTI.

The AMSSRTI can be used to process state signals produced by many other types of sensors describing a steady state regime or a working process (e. g. in milling process).