Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

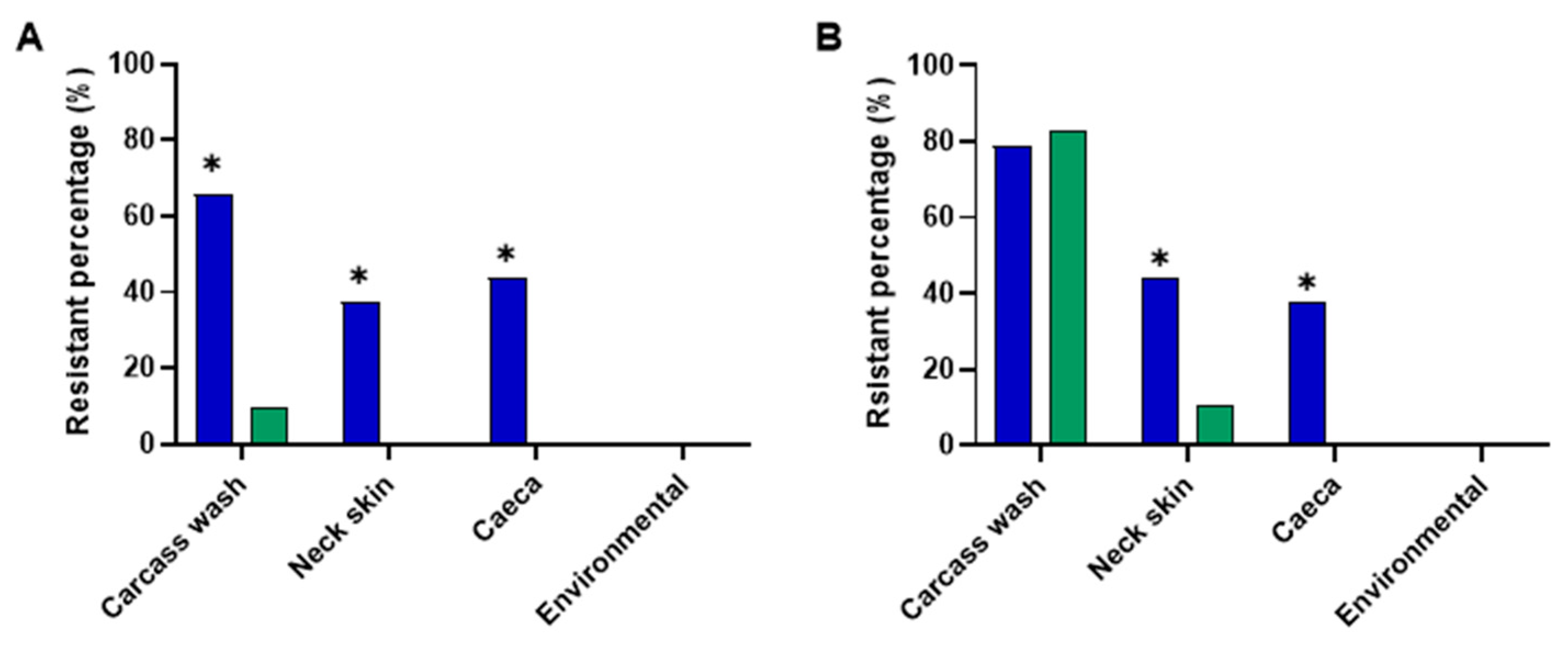

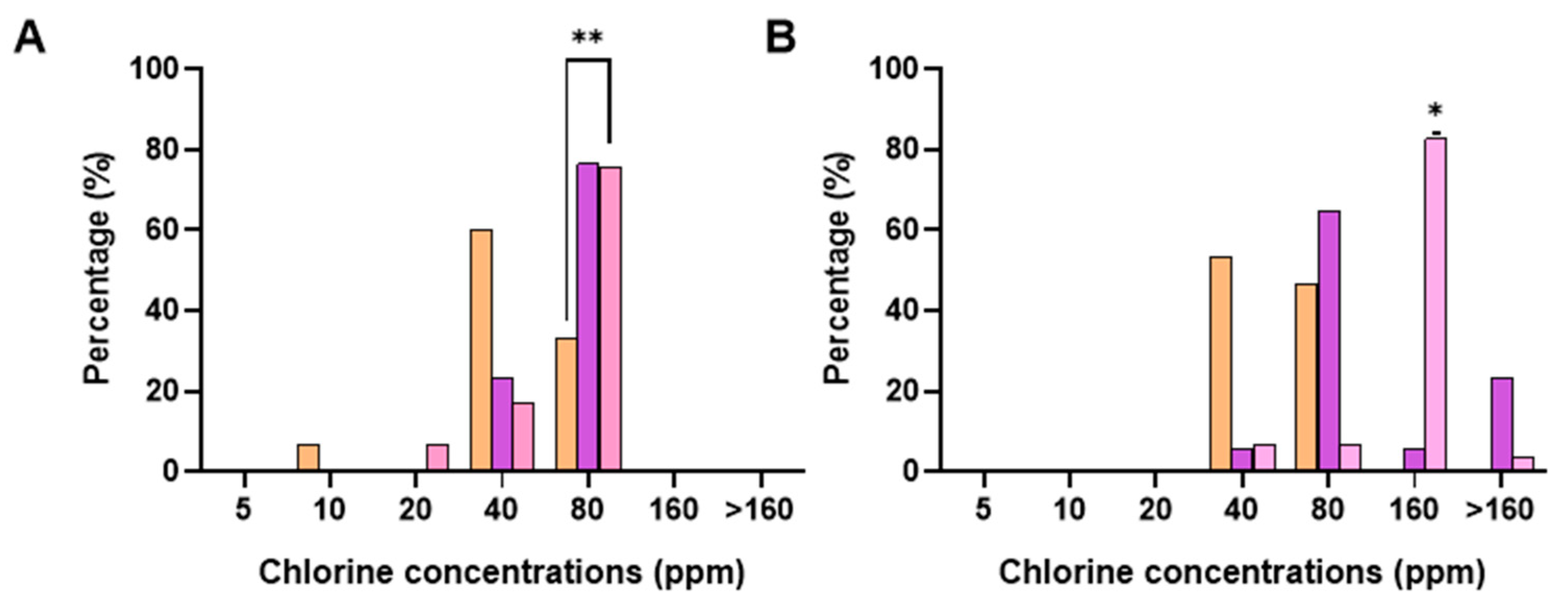

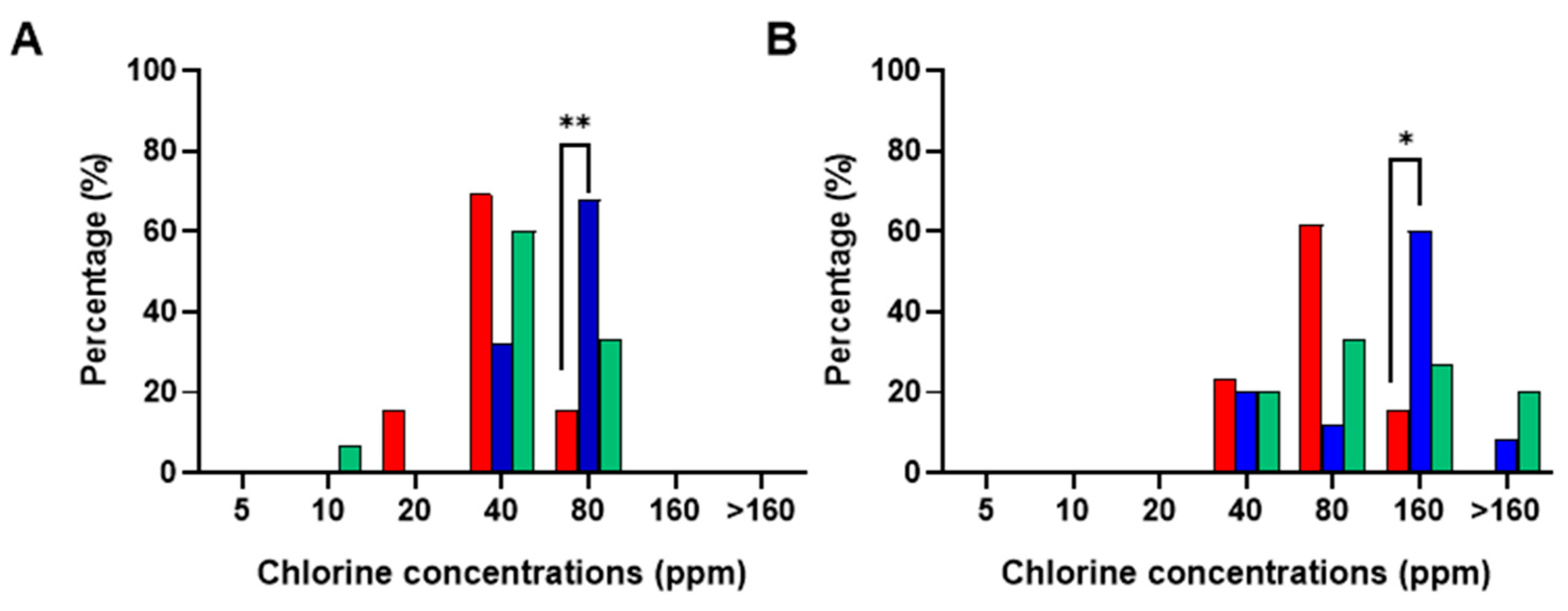

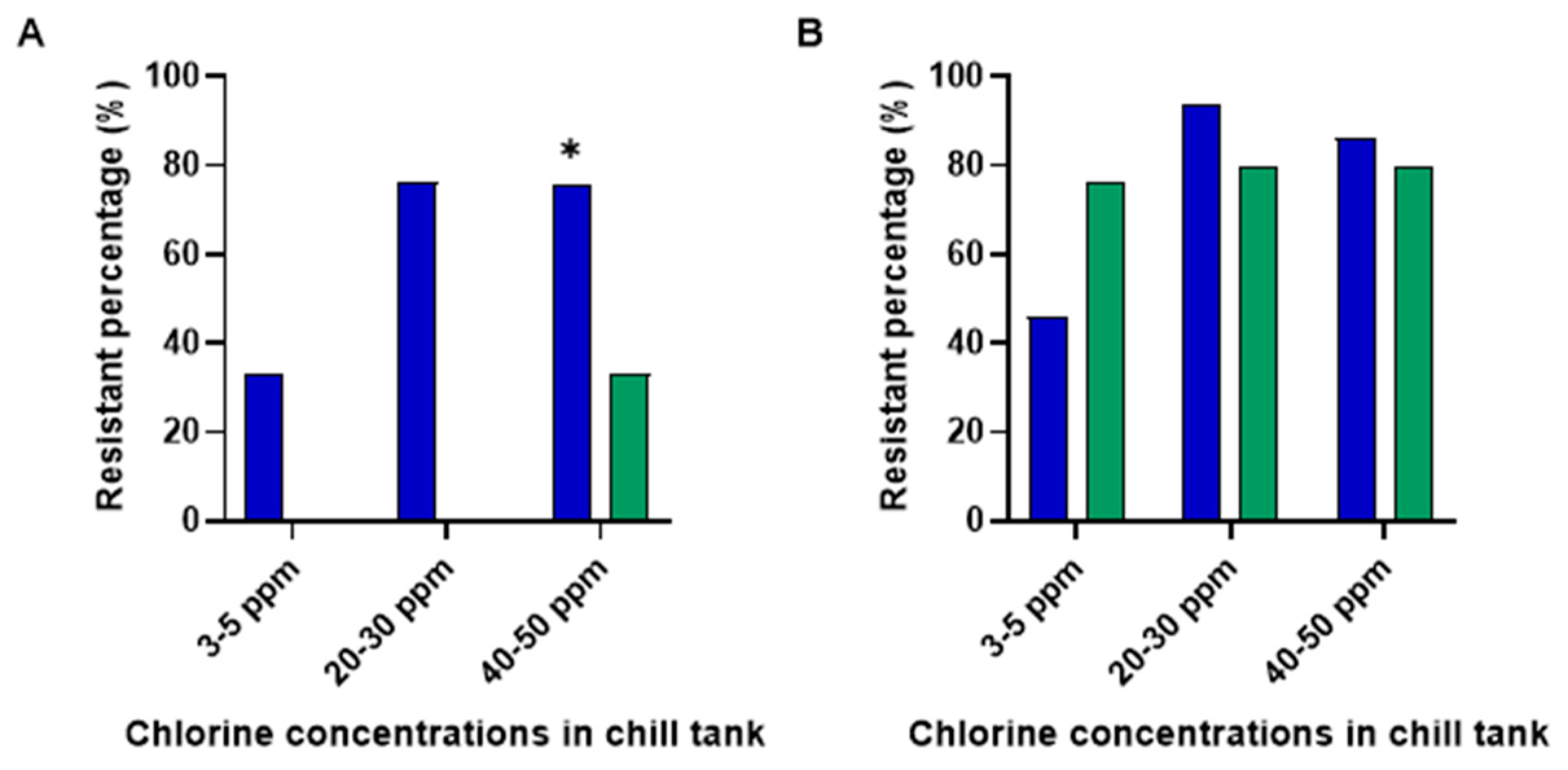

Salmonella Typhimurium and Campylobcater jejuni are major food-borne pathogens that continue to persist in the poultry processing industry and cause health and economic burdens. Chlorine is commonly used to mitigate bacterial contamination in poultry processing. However, inducing of adaptive stress response mechanism in sub-lethal exposure limits the effectiveness of chlorine. In the present study, we determined the effect of pre-exposure to chlorine on chlorine tolerance in S. Typhimurium and C. jejuni. MIC and MBC were determined in caecal, neck skin, post– chill carcass washing, and the environmental isolates. The carcass washings were exposed to either 3-5 ppm, 20-30 ppm, or 40- 50 ppm of chlorine in the chill tank and MICs and MBCs were significantly higher (p<0.05). Notably, 60% of C. jejuni isolated from the carcasses in a 20-30 ppm chill tank showed the highest MBC of 160 ppm. Chlorine-resistant percentage in S. Typhimurium and C. jejuni of the carcass was 78.8% and 83% respectively, while 94.1% and 80% of resistance were detected in 20-30 ppm chill tank isolates. The highest resuscitation detected carcass washing isolates exhibited the sub-lethal injury. Chlorine resistance limits the space to work with concentration adjustments. Therefore moving to alternative chemical and novel multi-huddle interventions is crucial.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Campylobacter and Salmonella Inoculums

2.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) Determination to Chlorine

2.3. Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations (MBC) Determinations to Chlorine

2.4. Resuscitation Assay

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Salmonella Typhimurium and Campylobacter Jejuni Susceptibility to Chlorine: MIC and MBC Determination

3.2. Chlorine Resistance Profiles of S. Typhimurium and C. jejuni

3.3. Effect of Chlorine Concentration in the Chill Tank on MIC/MBC Profiles of S. Typhimurium and C. jejuni

3.4. Chlorine Resistance Profiles of S. Typhimurium and C. jejuni Isolated from Carcass Wash

3.5. Recovery of S. Typhimurium and C. jejuni after Exposed to Chlorine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| HACCP | Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentrations |

| MBC | Minimum bactericidal concentrations |

| ASC | Acidified Sodium Chlorite |

| PAA | PerAcetic Acid |

| SH | Sodium Hypochlorite |

| GRAS | Generally Recognized as Safe |

| FSIS | Food Safety and Inspection Service |

References

- WHO. The Global View of Campylobacteriosis: Report of an Expert Consultation; WHO: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 9–11.

- EFSA, European Food Safety Authority; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union One Health 2019 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06406.

- Antunes, P., Mourão, J., Campos, J., & Peixe, L. Salmonellosis: the role of poultry meat. Clinical microbiology and infection,2016. 22(2): p. 110-121.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [CrossRef]

- Llarena, A.-K., E. Taboada, and M. Rossi, Whole-genome sequencing in epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2017. 55(5): p. 1269-1275. [CrossRef]

- Thames, H.T. and A. Theradiyil Sukumaran, A review of Salmonella and Campylobacter in broiler meat: emerging challenges and food safety measures. Foods, 2020. 9(6): p. 776. [CrossRef]

- Akil, L. and H.A. Ahmad, Quantitative risk assessment model of human salmonellosis resulting from consumption of broiler chicken. Diseases, 2019. 7(1): p. 19. [CrossRef]

- Fouts, D. E., Mongodin, E. F., Mandrell, R. E., Miller, W. G., Rasko, D. A., Ravel, J., Brinkac, L. M., DeBoy, R. T., Parker, C. T., & Daugherty, S. C. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple Campylobacter species. PLoS biology, 2005. 3(1): p. e15. [CrossRef]

- Hardie, K. M., Guerin, M. T., Ellis, A., & Leclair, D. Associations of processing level variables with Salmonella prevalence and concentration on broiler chicken carcasses and parts in Canada. Preventive veterinary medicine, 2019. 168: p. 39-51. [CrossRef]

- Pavic, A., J.M. Cox, and J.W. Chenu, Effect of extending processing plant operating time on the microbiological quality and safety of broiler carcasses. Food Control, 2015. 56: p. 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Chen Fur, C., S.L. Godwin, and A. Kilonzo-Nthenge, Relationship between cleaning practices and microbiological contamination in domestic kitchens. Food Protection Trends, 2011. 31(11): p. 672-679.

- Donelan, A. K., Chambers, D. H., Chambers IV, E., Godwin, S. L., & Cates, S. C. Consumer poultry handling behavior in the grocery store and in-home storage. Journal of food protection, 2016. 79(4): p. 582-588.

- Leone, C., Xu, X., Mishra, A., Thippareddi, H., & Singh, M.A. Interventions to reduce Salmonella and Campylobacter during chilling and post-chilling stages of poultry processing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Poultry Science, 2024: p. 103492. [CrossRef]

- Backert, S., Fighting Campylobacter Infections: Towards a One Health Approach.Springer Nature , 2021.Vol. 431. 2021:.

- USDA-FSIS; The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). USDA Finalizes New Food Safety Measures Reduce Salmonella and Campylobacter in Poultry, Washington. 4 February 2016. Available online: https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2016/02/04/usda-finalizes-new-food-safety-measures-reduce-salmonella-and (accessed on 4 February 2016).

- Northcutt, J., Smith, D., Musgrove, M., Ingram, K., & Hinton Jr, A. Microbiological impact of spray washing broiler carcasses using different chlorine concentrations and water temperatures. Poultry Science, 2005. 84(10): p. 1648-1652.

- Virto, R., Manas, P., Alvarez, I., Condon, S., & Raso, J. Membrane damage and microbial inactivation by chlorine in the absence and presence of a chlorine-demanding substrate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2005. 71(9): p. 5022-5028.

- Anonymous, Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European parliament and of the council of 29 april 2004 Laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. Official Journal L, 2004. 139: p. 55-205.

- Anonymous (2005). Scientific Assessment of the Public Health and Safety of Poultry Meat in Australia. New Zealand: Food Standards Australia New Zealand.

- Chousalkar, K., Sims, S., McWhorter, A., Khan, S., & Sexton, M. The effect of sanitizers on microbial levels of chicken meat collected from commercial processing plants. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2019. 16(23): p. 4807. [CrossRef]

- Lillard, H., Factors affecting the persistence of Salmonella during the processing of poultry. Journal of Food Protection, 1989. 52(11): p. 829-832. [CrossRef]

- Muhandiramlage, G.K., A.R. McWhorter, and K.K. Chousalkar, Chlorine Induces Physiological and Morphological Changes on Chicken Meat Campylobacter Isolates. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2020. 11: p. 503. [CrossRef]

- Obe, T., A.S. Kiess, and R. Nannapaneni, Antimicrobial Tolerance in Salmonella: Contributions to Survival and Persistence in Processing Environments. Animals, 2024. 14(4): p. 578. [CrossRef]

- Weerasooriya, G., Khan, S., Chousalkar, K. K., & McWhorter, A. R. Invasive potential of sub-lethally injured Campylobacter jejuni and Salmonella Typhimurium during storage in chicken meat juice. Food Control, 2022: p. 108823. [CrossRef]

- Keener, K., Bashor, M., Curtis, P., Sheldon, B., & Kathariou, S. Comprehensive review of Campylobacter and poultry processing. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety, 2004. 3(2): p. 105-116. [CrossRef]

- Weerasooriya, G., McWhorter, A. R., Khan, S., & Chousalkar, K. K. Transcriptomic response of Campylobacter jejuni following exposure to acidified sodium chlorite. npj Science of Food, 2021. 5(1): p. 23. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, À., Lenahan, M., Duffy, G., Fanning, S., & Burgess, C. The potential for biocide tolerance in Escherichia coli and its impact on the response to food processing stresses. Food Control, 2012. 26(1): p. 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Braoudaki, M. and A. Hilton, Adaptive resistance to biocides in Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli O157 and cross-resistance to antimicrobial agents. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2004. 42(1): p. 73-78.

- Weerasooriya, G., Dulakshi, H., de Alwis, P., Bandara, S., Premarathne, K., Dissanayake, N., Liyanagunawardena, N., Wijemuni, M., & Priyantha, M. Persistence of Salmonella and Campylobacter on Whole Chicken Carcasses under the Different Chlorine Concentrations Used in the Chill Tank of Processing Plants in Sri Lanka. Pathogens, 2024. 13(8): p. 664. [CrossRef]

- CLSI, M107 Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard-11th edition, December 2018. 2018.

- Murphy, C., C. Carroll, and K.N. Jordan, Environmental survival mechanisms of the foodborne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2006. 100(4): p. 623-632. [CrossRef]

- Karki, A.B., H. Wells, and M.K. Fakhr, Retail liver juices enhance the survivability of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli at low temperatures. Scientific reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Touati, D., Jacques, M., Tardat, B., Bouchard, L., & Despied, S. Lethal oxidative damage and mutagenesis are generated by iron in delta fur mutants of Escherichia coli: protective role of superoxide dismutase. Journal of Bacteriology, 1995. 177(9): p. 2305-2314. [CrossRef]

- Tamblyn, K.C. and D.E. Conner, Bactericidal activity of organic acids against Salmonella Typhimurium attached to broiler chicken skint. Journal of Food Protection, 1997. 60(6): p. 629-633. [CrossRef]

- Thames, H.T. and A. Theradiyil Sukumaran, A review of Salmonella and Campylobacter in broiler meat: emerging challenges and food safety measures. Foods, 2020. 9(6): p. 776. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X., Bai, L., Wang, S., Liu, L., Qu, X., Zhang, J., Xiao, Y., Tang, B., Li, Y., & Yang, H. Chlorine tolerance and cross-resistance to antibiotics in poultry-associated Salmonella isolates in China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022. 12: p. 833743. [CrossRef]

- USDA-FSIS. (United States Department of Agriculture, FSIS). Safe and Suitable Ingredients Used in the Production of Meat, Poultry, and Egg Products–Revision 58. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/policy/fsis-directives/7120.1 (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Condell, O., Iversen, C., Cooney, S., Power, K. A., Walsh, C., Burgess, C., & Fanning, S. Efficacy of biocides used in the modern food industry to control Salmonella enterica, and links between biocide tolerance and resistance to clinically relevant antimicrobial compounds. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2012. 78(9): p. 3087-3097. [CrossRef]

- Obe, T., Nannapaneni, R., Sharma, C. S., & Kiess, A. Homologous stress adaptation, antibiotic resistance, and biofilm forming ability of Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg ATCC8326 on different food-contact surfaces following exposure to sublethal chlorine concentrations. Poultry science, 2018. 97(3): p. 951-961. [CrossRef]

- Molina-González, D., Alonso-Calleja, C., Alonso-Hernando, A., & Capita, R. Effect of sub-lethal concentrations of biocides on the susceptibility to antibiotics of multi-drug resistant Salmonella enterica strains. Food Control, 2014. 40: p. 329-334. [CrossRef]

- Capita, R., Alonso-Calleja, C., Garcia-Fernandez, M. d. C., & Moreno, B. Microbiological quality of retail poultry carcasses in Spain. Journal of food protection, 2001. 64(12): p. 1961-1966. [CrossRef]

- Bauermeister, L. J., Bowers, J. W., Townsend, J. C., & McKee, S. R. Validating the efficacy of peracetic acid mixture as an antimicrobial in poultry chillers. Journal of food protection, 2008. 71(6): p. 1119-1122. [CrossRef]

- Wesche, A. M., Gurtler, J. B., Marks, B. P., & Ryser, E. T. Stress, sublethal injury, resuscitation, and virulence of bacterial foodborne pathogens. Journal of food protection, 2009. 72(5): p. 1121-1138. [CrossRef]

- Rhouma, M., Romero-Barrios, P., Gaucher, M.-L., & Bhachoo, S. Antimicrobial resistance associated with the use of antimicrobial processing aids during poultry processing operations: cause for concern? Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2021. 61(19): p. 3279-3296.

- Guillén, S., Nadal, L., Álvarez, I., Mañas, P., & Cebrián, G. Impact of the Resistance Responses to Stress Conditions Encountered in Food and Food Processing Environments on the Virulence and Growth Fitness of Non-Typhoidal Salmonellae. Foods, 2021. 10(3): p. 617. [CrossRef]

| Sample point | Isolation number ( n) | |

|---|---|---|

| S.Typhimurium | C. jejuni | |

| Ceaca | 16 | 11 |

| Neck skin | 12 | 15 |

| Carcass washing ( 3-5 ppm) | 15 | 13 |

| Carcass washing (20-30 ppm) | 17 | 25 |

| Carcass washing ( 3-5 ppm) | 29 | 15 |

| Environmental samples | 22 | 17 |

| Total isolate number | 111 | 96 |

|

Chorine Concentrations (ppm) |

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) Isolate percentage (%) |

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) Isolate percentage (%) |

||||||

| Carcass wash |

Neck skin | Caeca |

Environment | Carcass wash |

Neck skin | Caeca |

Environment | |

| 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 4.5 |

| 10 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 4.5 |

| 20 | 3.3 | 0 | 6.2 | 35.2 | 3.2 | 11.2 | 6.25 | 36.3 |

| 40 | 29.5 | 62.5 | 50.0 | 41.1 | 18.0 | 44.4 | 56.25 | 54.5 |

| 80 | 65.6 | 37.5 | 43.8 | 0.0 | 68.9 | 44.4 | 37.5 | 0.0 |

| 160 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| >160 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

Chorine Concentrations (ppm) |

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) Isolate percentage (%) |

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) Isolate percentage (%) |

||||||

| Carcass wash |

Neck skin | Caeca |

Environment | Carcass wash |

Neck skin | Caeca |

Environment | |

| 2.5 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 9.0 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.7 |

| 10 | 5.7 | 21.1 | 45.5 | 23.5 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 18.2 | 11.7 |

| 20 | 32.1 | 36.8 | 45.5 | 23.5 | 0.0 | 42.1 | 27.3 | 35.2 |

| 40 | 52.8 | 36.8 | 0.0 | 41.1 | 17.0 | 42.1 | 54.5 | 41.1 |

| 80 | 9.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.0 | 10.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 160 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| >160 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Isolated Sample | S.Typhimurium recovery percentage (%) | C . jejuni recovery percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Carcass wash | 52.4% (32/61) | 58.5 (30/51) |

| Neck skin | 50 % (4/8) | 55.5 % (5/9) |

| Caeca | 33.3 % (5/15) | 16.6 % (1/6) |

| Environmental | 16.6 % (2/12) | 14.2 % (1/7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).