1. Introduction

The future development prospects of many African countries are closely linked to the agricultural sector [

1]. Like any economic activity, agriculture requires the right resources and factors for optimal performance. One key factor is human resources, particularly women, who play a pivotal role in African agriculture. In fact, women represent approximately 43% of the agricultural labor force in developing countries, with their share reaching 70% in Tunisia, 50% Eastern Asia, and 20% in Latin America [

2]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, agriculture accounts for approximately 21% of the continent's GDP and women contribute 60-80% of the labour used to produce food both for household consumption and for sale [

3]. In Congo, women account for 73% of those economically active in agriculture and produce more than 80% of the food crops. In Morrocco, approximately 57% of the female population participates in agricultural activities, with greater involvement in animal (68%) as opposed to vegetable production (46%). Studies have indicated that the proportion of agricultural work carried out by men, women and children is 42%, 45% and 14% respectively [

4]. However, climate change represents one of the most significant global challenges today. Its impact on agriculture is profound, as agriculture is widely recognized as one of the most climate-sensitive human activities [

5,

6]. The effects of climate variations on agriculture differ across regions, leading to significant socio-economic consequences, particularly in developing countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, Agriculture continues to loom large in the development possibilities. Rural populations are especially vulnerable due to their heavy reliance on rain-fed agriculture, which accounts for nearly 93% of cultivated land [

7].

Climate change impacts daily lives and livelihoods unequally, with different gender groups being affected in distinct ways. The prevailing impacts, however, disproportionately affects women more and exacerbate the inequalities between genders [

8]. According to [

9], gender vulnerability to climate change stems from differences in roles and responsibilities, exacerbated by limited resources, poor employment opportunities, and cultural constraints on women’s activities [

10]. While both men and women working in natural resource-dependent sectors like agriculture will face the consequences of climate change, women are particularly vulnerable, especially poor female farmers who rely heavily on rain-fed agriculture [

11,

12]. In fact, research conducted by Oxfam (2015)[

13] posits that women constitute a very vulnerable population group, particularly those in less economically developed countries who suffer from delayed economic development and generally live-in poverty. This heightened vulnerability is due to women’s overrepresentation among the world’s poor and their greater dependence on natural resources that are increasingly under threat. Gender roles, responsibilities, decision-making power, and access to land, resources, and opportunities differ significantly between men and women. Globally, women have less access to resources such as land, credit, agricultural inputs, decision-making structures, technology, training, and extension services. This disparity limits their ability to adapt to the challenges posed by climate change [

14]. Furthermore, rural women are charged with the responsibility to secure water, food, and fuel for cooking which is being marred by unequal access to natural resources [

15], this has limited their mobility and made them more affected by the perils of climate change [

16].

In Tunisia women's role in the agricultural sector is essential, especially in rural areas, yet they are particularly vulnerable to climate change. Although central to agriculture and natural resource management, studies on their vulnerabilities remain limited and often overlook key challenges. For instance, research by LABIADH [

16] and CREDIF [

17] offer insights into gender issues in agriculture but fall short of fully exploring the intersections of climate change and gender. Exclusion from water management schemes, as noted in Houloul’s public policy review in Tunisia, compounds these challenges by preventing effective integration of women into climate resilience strategies [

19].

The purpose of this research is to examine the effects of climate change on the livelihood of rural women, Women’s Agricultural Development Groups in the Sidi Bouzid region of Tunisia, where climate change and water scarcity significantly affect their activities. The study also offered insights into the resilience strategies of Women Agricultural Development Groups members, emphasizing the roles of various stakeholders in shaping these groups' adaptive capacities. Guided by two main questions: “How does climate change, coupled with water scarcity, impact the functioning of female Agricultural Development Groups?” and “How do administrative and associative actors influence either the resilience or vulnerability of these groups?”

2. Materials and Methods

The research employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating questionnaires, focus group discussions, and typological analysis. This combination provided a comprehensive understanding of the resources needed to enhance the livelihoods of rural women affected by climate change.

2.1. Mapping and Profiling of Farmers’ Organizations in Sidi Bouzid

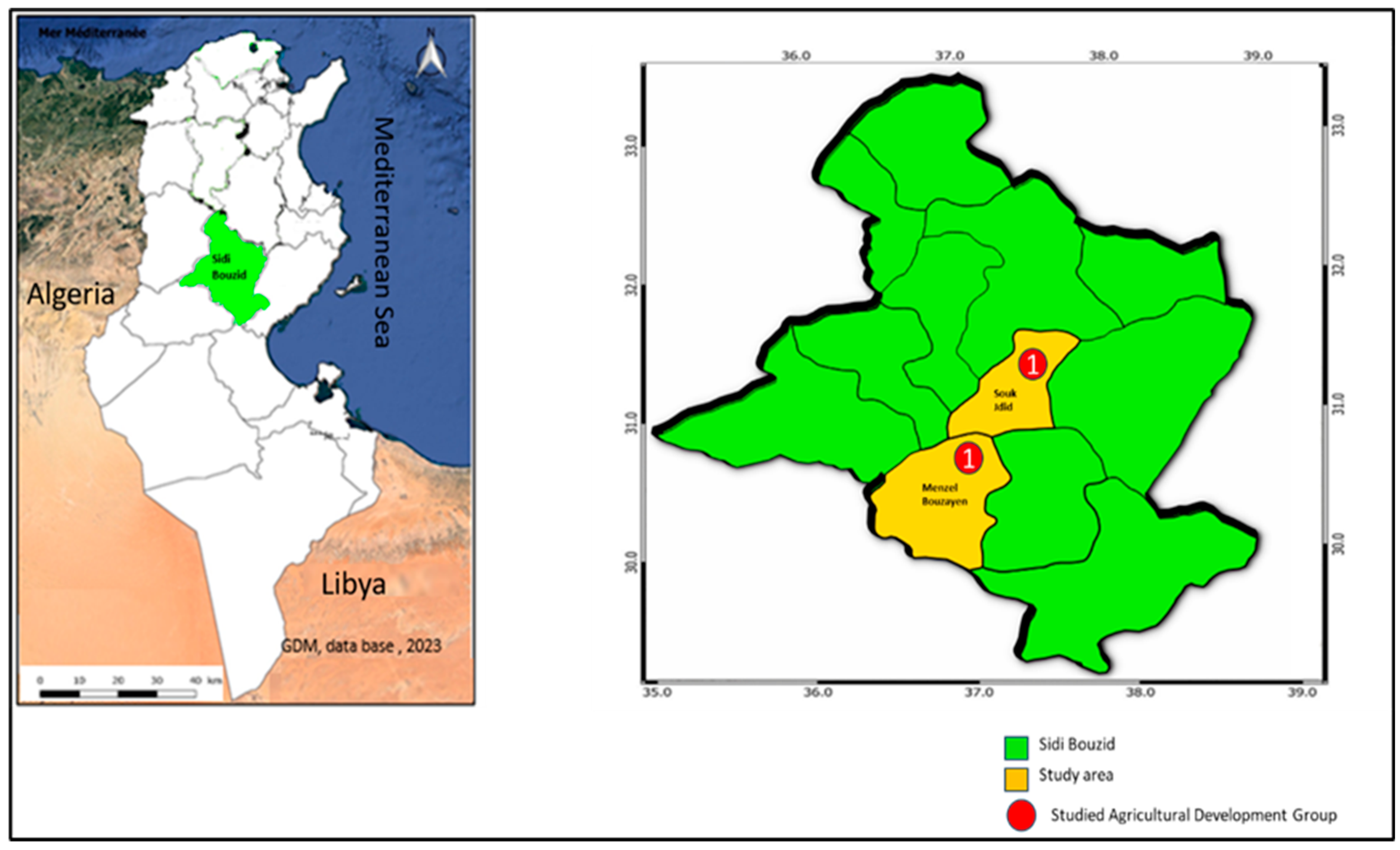

Sidi Bouzid is one of the local 24 governorates of Tunisia. It is situated between latitudes 35°2'17.63"N and longitude 9°29'5.78"E (

Figure 1). It is in central Tunisia and land locked. It covers an area of 7405 km2 and has a population of 400 thousand inhabitants .77% of this population is rural and their income is generated by agriculture activities. Women account for 60% of the total workforce in the agricultural sector [

20]. The illiteracy rate remains high, reaching 29.2% (compared to 18.8% nationally) [

21]. This region falls within the lower arid zone, where precipitation is scarce and irregular, with an annual average ranging from 150 mm to 300 mm [

20]. Itis notable for the scarcity of surface water, estimated at approximately 60 million m³. In 2016, the volume of exploited groundwater exceeded 95 million m³ [

21]. To empower women in the region, the government established six development groups following the revolution. As part of our sample selection process, we conducted a series of working meetings with the Director of the Rural Women’s District at the governorate level, as well as with the presidents of the six agricultural development groups. In-depth interviews with each president provided a clearer understanding of how these groups function, guiding our selection for the study. These development groups were created between 2017 and 2022: Two were established in 2017 and are currently active, two were created in 2020 but are not operational, and two were founded in 2023 and have yet to become active. For the purpose of this study, we are therefore focusing on the currently operational groups. Consequently, the two Agricultural Development Groups chosen to assess the impact of climate change on women are Battoumet and Magdiat. Located in different areas they present specific particularities and difficulties in managing agricultural resources and women's participation.

2.2. Focus Group

In order to explore the impact of climate change on the local community particularly regarding the reduction of water resources, gender issues, and the vulnerability of women, we organized two focus groups with various members of development groups, selected using an observed guideline and participatory exercises. Each focus group included 25 participants, comprising women, men, and stakeholders from government organizations. Observation guidelines were developed for each group of respondents to discuss men’s and women’s activities and the perceived effects of climate change on: (i) vulnerability and gender dynamics; (ii) how extreme weather events disproportionately impact men and women in rural areas; and (iii) women’s social and economic status. The data was recorded in field notes and transcribed.

2.3. Collect Data

To assess rural women’s understanding of climate change, its impact on their households, and their adaptation strategies, data were gathered from both primary and secondary sources. Primary data were collected through surveys targeting a sample of 30 female household members from WADG. These household surveys employed close-ended questionnaires to explore the interplay between climate change and women. Key areas of focus included respondents’ activities, perceptions of climate change, and adaptation strategies.

The questionnaires were distributed based on the geographical spread of the community, with 20 distributed in Souk Jdid and 10 in Menzel Bouzayen. Data collection was conducted between January and February 2024. Questionnaires included an informed consent section that highlights what the study is about, it states how the information given will be used, it noted the rights of the researcher to confdentiality and the protection of their privacy.

In addition to the surveys, interviews were conducted with selected local stakeholders, including representatives from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the forestry department, the Ministry of Agriculture, officials from the CRDA, and the Director of the Rural Women Support Office. These interviews, structured around close-ended questionnaires, aimed to identify the various strategies adopted by governmental and non-governmental organizations to support women in rural areas (

Table 1)

The discussions focused on understanding efforts to enhance the quality and accessibility of essential resources and services while ensuring increased participation of women in these initiatives, thereby maximizing the benefits for rural women. The insights gathered helped to map existing support mechanisms and highlight areas for improvement in addressing gender-specific challenges in rural contexts.

2.4. Analytical Methods

The collected data were analyzed using a two-step approach to provide both a comprehensive overview and in-depth insights. First, descriptive statistics were applied to summarize and visualize the data. This included calculating measures such as mean, frequency, and percentage to explore distributions within the dataset. These analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Second, a more advanced typological analysis was performed to classify and understand relationships between variables and actors [

22]. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), a multivariate statistical method used to classify rural women’s vulnerability using a categorical indicators (

Table 2). This analysis was executed using SPSS.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Profile of Agricultural Development Group Members

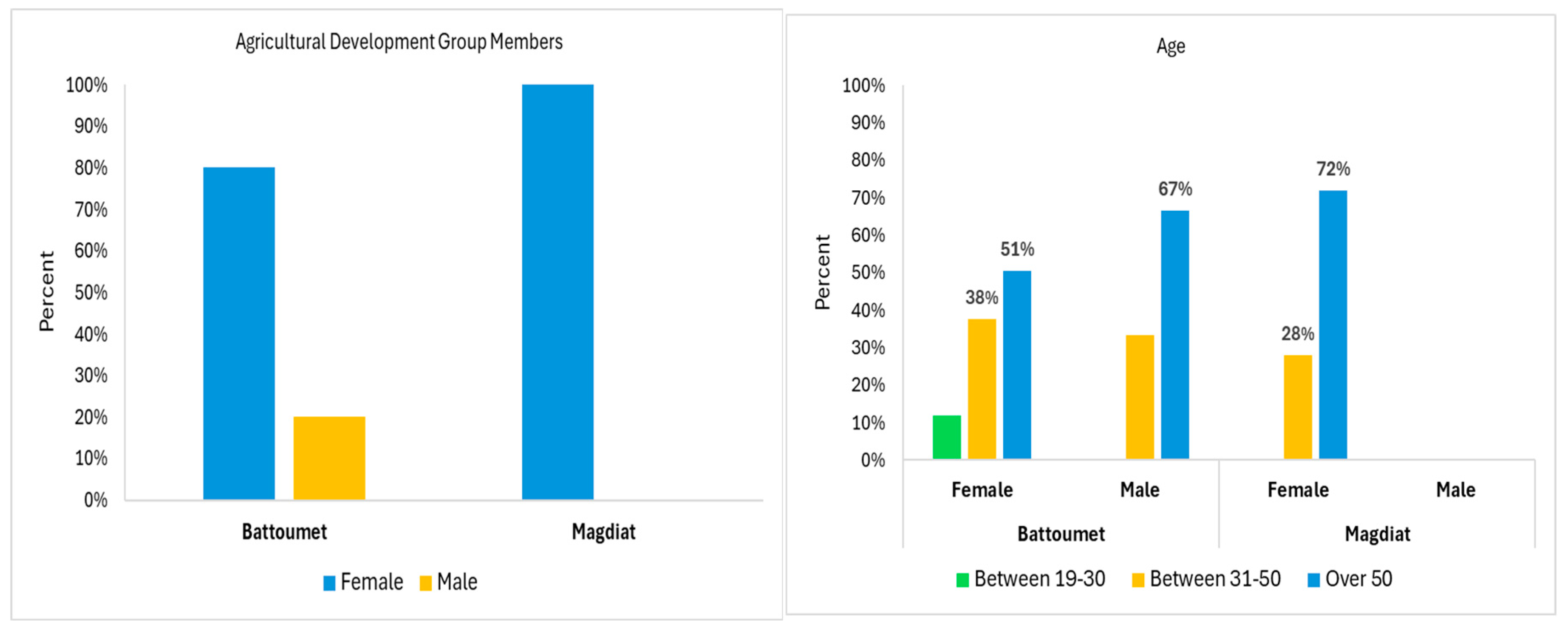

This study focuses on the operational dynamics of two Agricultural Development Groups: Battoumet and Magdiat. Battoumet, created in 2017 in Souk Jdid region, it is the pioneer of agricultural groups in the region, with a mission focused on the empowerment of women in the agricultural sector. It stands out with a predominantly female membership, comprising 60 women, who represent 80% of its members, alongside 15 men (20%) (

Figure 2). This team benefits from the expertise of qualified professionals, including an agronomist engineer and a food technician, thus enhancing the technical skills of the group. The Agricultural Development Group Magdiat is located in Menzel Bouzayen (

Figure 2). Founded in 2021, this group is exclusively female, composed of about 25 members. The age distribution of Agricultural Development Group members indicates that 72% of rural women in Magdiat are over the age of 50. In contrast, in Battoumet, the majority of women are in their most productive and reproductive years, with 18% aged 19–30 and 47% aged 31–50 (

Figure 2).

According to focus group discussion participants, 60 % of the women’s member group of Agricultural Group were not able to read and write, while only 40% of them attended their education . For Magdiat agricultural group, 80% were not able to read and write while only 15 %of them attended primally level and 5% only attended secondary level. However, for Battoumet agricultural group, 20% of women were not able to read and write. 30 % can read and write only and 50% attended high education level (above secondary).

3.1.2. Access to Water

Results showed that rural women have a larger role relative to men in water, sanitation and hygiene activities, including in agriculture and domestic labour. They collected water from different sources. In fact, 25 % of participants mainly in Battoumet agricultural group have access to water though the national water distribution network (e.g., SONEDE), highlighting a severe lack of infrastructure in these rural areas. 35% of the participants have access to water through private wells, a resource that has historically been crucial in the absence of public water networks. However, these individual wells are increasingly becoming unreliable due to the impacts of climate change. Rising temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, and prolonged droughts are making it more difficult for these wells to maintain a steady supply of water. The water levels in wells are dropping, and the quality of water may also be compromised, as reduced rainfall and extreme weather events can lead to contamination from various sources, including agricultural runoff and inadequate sanitation facilities. This situation puts rural women in a particularly vulnerable position. Furthermore, 40% of women, especially those in the Magdiat agricultural group, reported that they do not have reliable access to water. As a result, they are forced to walk long distances to collect water or pay exorbitant amounts to secure it. One participant shared, “Sometimes we drink rainwater, other times water from the pond. We boil it if we can, but we don’t always have the time. This practice underscores the struggle to find safe drinking water, especially during prolonged dry periods when water levels in natural resources decrease. While women are primarily responsible for collecting water, men are often tasked with purchasing water from vendors who charge high prices for water delivery via tankers. This situation puts significant financial strain on households, further exacerbating their economic challenges. As one woman noted, “The high cost of buying water impacts our economic situation,”

3.1.3. Activities by Gender

Results showed that the main activities of Battoumet include the processing of local agricultural products that needed for traditional dishes such as couscous, bsissa (a traditional Mediterranean food from roast cereals mixed with spices) and chorba (a traditional vegetable and meat soup) as well as the drying of garlic and chili peppers. According to the president's statement are Battoumet is also involved in capacity building of their members and in the different stage of production and Marketing of product. Magdiat initially focused on processing cereal products for the traditional production of "Aoula," including items such as couscous and Mhamsa (

Table 3). However, to adapt to contemporary challenges such as climate change, the group is evolving to specialize in new activities, including the collection and distillation of natural aromatic and medicinal plants like rosemary and thyme.

The results of these focus groups revealed significant gender-based disparities in responsibilities and opportunities (

Table 3). Women occupy a crucial social and economic role, managing nearly all domestic activities, including child education, and ensuring the success of their family life. They also contribute significantly to agriculture, often under very harsh and challenging conditions, facing severe climatic challenges during the harvest of cereals and vegetables such as peppers and tomatoes. Women are involved in the transformation and packaging of these products into finished goods like "Aoula." Despite their significant contributions and the tough working conditions, including high temperatures, women earn considerably less than men, who typically hold roles as farm managers, make critical decisions about cereals, and seek paid work in farms, road construction, or as day laborers. Women, in contrast, have limited opportunities for paid employment in the rural sector.

Additionally, 65% of the surveyed female members engage in secondary activities beyond their involvement in agricultural development groups. Many of these women work as seasonal laborers, particularly in olive harvesting, to generate supplementary income crucial for meeting their families' needs. This additional income is vital in a context increasingly marked by climatic uncertainties, which make daily survival even more precarious.

3.2. Rural Women’s Vulnerability to Climate Change

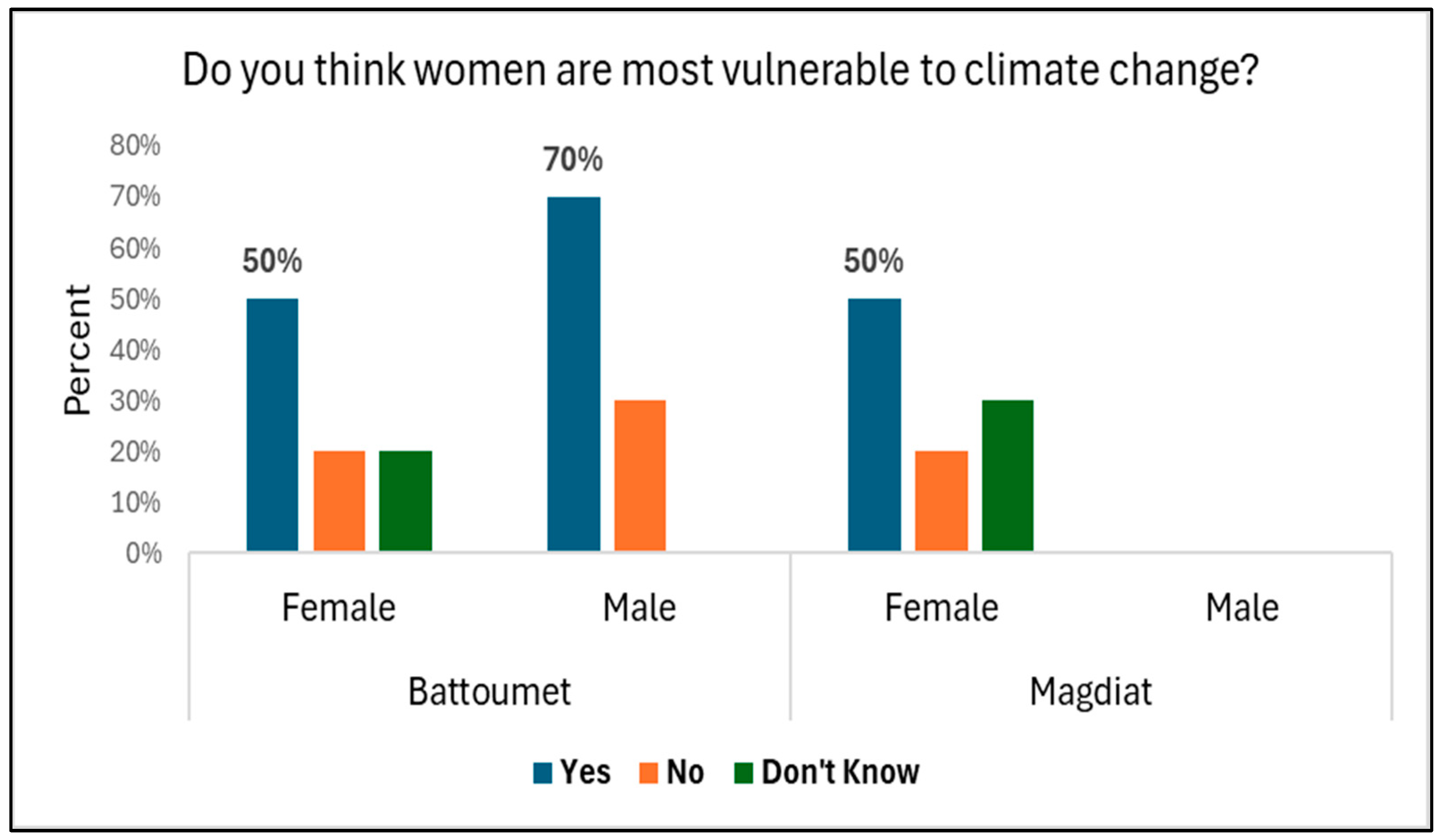

Based on the focus group results, 50% of female respondents and 70% of male respondents agreed that women are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and variability compared to other segments of society (

Figure 3). To evaluate the impact of climate change on rural women women certains factors has to be considered such as their information source , their level understanding of the concept of climate change and rural women ’s perception of climate.

3.2.1. Rural Women ‘s Perception of Climate Change

Results showed that women in sidi Bouzid region access to the climatic information through different sources. In fact, 40% of surveyed women rely on intergenerational knowledge and local practices, observing natural signs such as plant behavior, water availability, increase in temperature, increase and decrease in rainfall amount and seasonal changes. Informal conversations play a significant role for 30% of women, particularly those in the Magdiat Agricultural Development Group, where neighbors and group members exchange information and experiences (

Table 4). Media platforms such as radio and social media remain one of the most accessible tools for disseminating weather forecasts and climate-related advisories for 20% of rural women. However, 10 % of total surveyed rural women get information from non-governmental organizations frequently which are engaged in raising awareness and disseminating tailored climate information, particularly to empower women in vulnerable communities.

3.2.2. Climate Change ‘s Impact on Rural Women

Results showed that this heightened vulnerability of rural women to climate change stems from differing household-level social activity needs, challenges in accessing natural resources—particularly water—and limited adaptive capacity.

In fact, in sidi Bouzid region women bear the sole responsibility for collect water. results revealed that 75 % of the surveyed women face significant challenges in accessing water, exacerbated by climate change. With the scarcity of water resources and decreasing precipitation, these difficulties are becoming increasingly pronounced. Women bear the sole responsibility for water supply, as one member expressed, " I'm everything in one" whether for agricultural, domestic, or professional needs within the Female Agricultural Development Groups. The women highlighted that the obstacles they face in accessing water have significant direct and indirect impacts on their daily lives. Water scarcity in Sidi Bouzid creates social tensions, often leading to conflicts within households, particularly with their spouses. Furthermore, women are required to travel long distances to fetch drinking water (

Figure 4), as one respondent described: “

During the dry season, less water flows downstream, and many local rivers, lakes, and canals have become contaminated due to saline intrusion and wastewater discharges, making it even more difficult to obtain clean water, we have to walk long distances, on average, 7 kilometers to fetch drinking water. Not only is the burden of work increasing, but our health, safety, and education are also affected.” This arduous task not only places a strain on their physical well-being but also impact their safety and limits their opportunities for education and personal development, highlighting the profound challenges posed by limited access to this essential resource.

Additionally, in sidi Bouzid there is a higher use of irrigation for farming. However, climate variability is affecting reliability of water. 60 % of farm confirm that the water scarcity and irregularity of precipitation affect degrade crop production, further reducing available food resources and affect domestic activities of rural women, which in turn impact their income. Women, often seen as the primary managers of domestic resources, face increased pressure to maintain stability and well-being within their families in a context of increasingly limited resources. As a result, they must exert extra efforts to seek alternative activities and generate necessary income to purchase food, reinforcing their essential role in managing family nutrition despite increased environmental challenges.

50 % of rural women confirmed also that climate-related challenges lead to a significant deterioration in activities within the Agricultural Development Group. In fact, water is essential for a variety of their productions, such as aoula, harissa, couscous, and the distillation of oils from forest products. Moreover, the scarcity and increased cost of raw materials exacerbate difficulties, with high prices becoming unsustainable for women. This situation often forces them to seek alternatives or abandon certain activities, reducing their income and potentially leading to unemployment. Furthermore, the cost of water tanks, which have become a necessity for those without direct access to water, is increasingly high, exacerbating the financial difficulties of these women and reinforcing their economic vulnerability.

3.2.3. Understanding Rural Women's Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Classification Approach

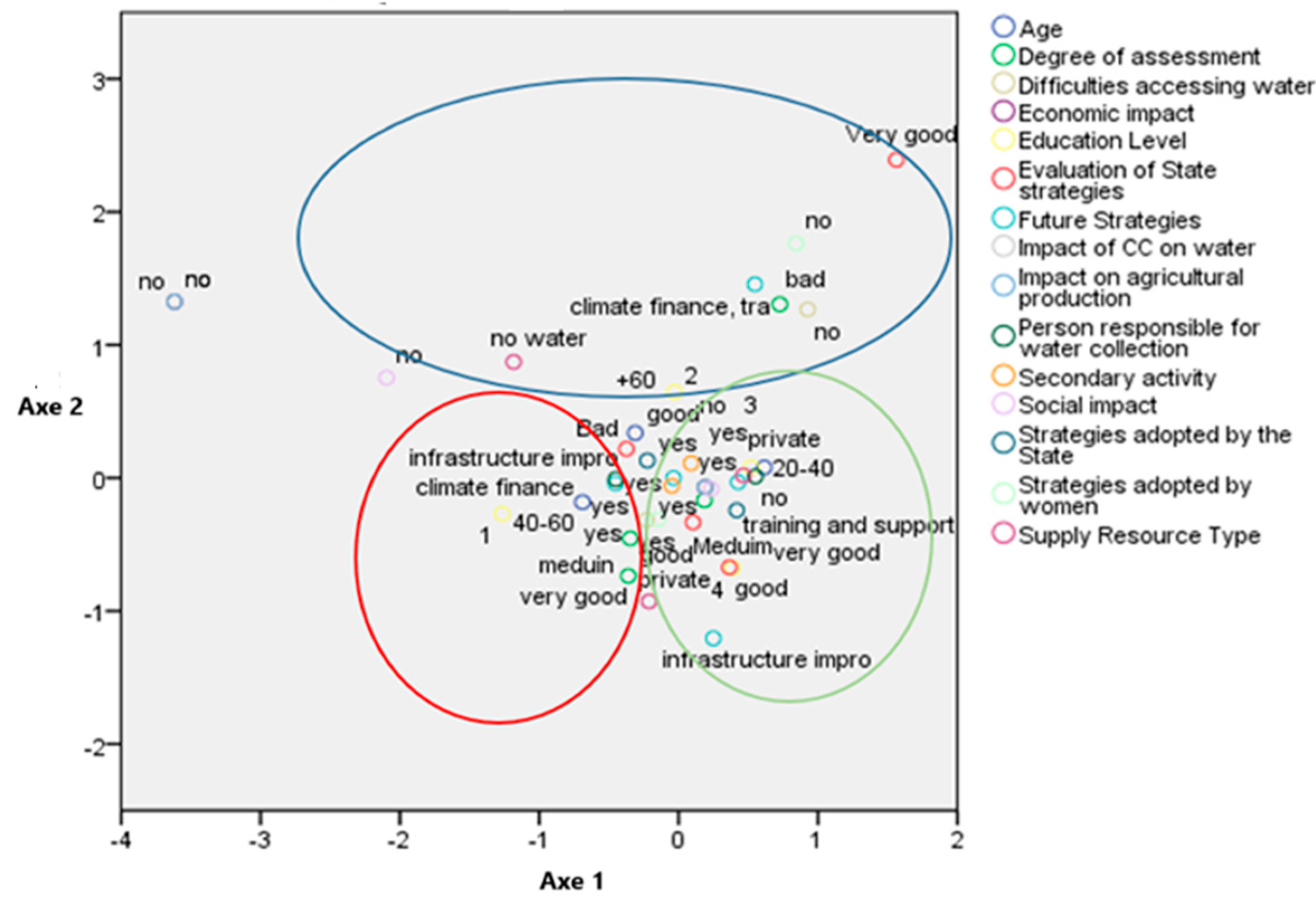

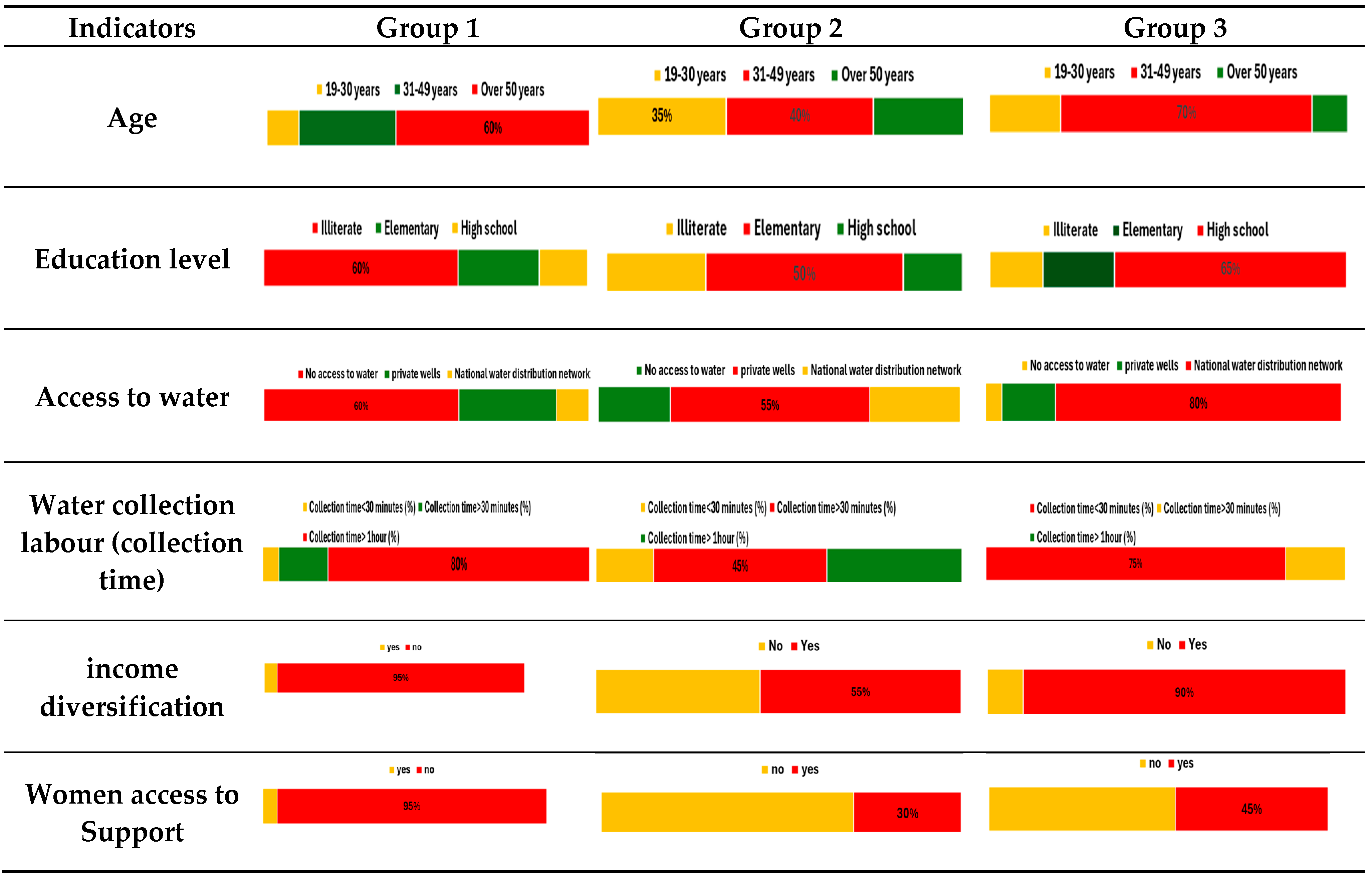

Results showed a significant variability between the women in terms of vulnerability, with each facing distinct challenges related to water access, agriculture, and the impacts of climate change. According to the joint modality diagram graph (

Figure 5), three heterogeneous groups can be noted.

Group1: Severely Vulnerable Women: This group consists of 60 % of female members aged over 50 years. 50% of women were not able to read and write These women, due to the lack of access to reliable water sources, have to travel long distances to reach wells or other water points (

Table 5). On average, these women may spend several hours per day collecting water, which reduces their available time for other activities such as agriculture or education.

These women do not engage in secondary activities outside their work within the Women’s Agricultural Development Group (

Table 5 ). They are constrained to purchase water tanks, the cost of which continues to rise. Despite their responsibility for water collection, they claim not to face water-related difficulties and believe that climate change does not affect agricultural production, their economy (income), or social aspects such as family conflicts. However, they consider the current strategies of their group ineffective and believe that the government does not implement new strategies. For the future, they propose developing climate finance to ensure the availability of crop varieties adapted to the climatic conditions of the Sidi Bouzid region and adopting new agricultural practices.

These women are highly vulnerable due to their age, limited education, and lack of access to water. Their reliance on purchasing water tanks, exacerbated by rising costs, highlights their economic vulnerability (Dependency on Natural Resources). Despite being responsible for water collection, they do not perceive the impact of climate change (Increased Exposure to Environmental Challenges), possibly due to generational perspectives and limited awareness. Additionally, they face challenges related to inadequate agricultural equipment, which further impairs their productivity (Vulnerability Related to Equipment). Their recognition of the ineffectiveness of current strategies and their suggestion to develop climate finance and adopt new agricultural practices show some awareness, though they do not fully grasp the immediate impacts of climate change.

Group 2: Vulnerable Women: It consists of 50 % women aged 31 to 49. 50% of women in this group had primary education degree (elementary) (

Table 5). In addition to their activities within the agricultural development group, these women primarily hold agricultural laborer positions. Although 55 % of women use a private water source from their own well, they encounter severe supply difficulties. There are also responsible for water collection, and these difficulties have a major economic impact due to the effects of climate change on agricultural production, affecting all their activities requiring agricultural raw materials. Socially, this causes conflicts and stress within their families. This group has adopted strategies to overcome climate challenges and rates them as moderately to highly effective. They believe that the government has not implemented elaborate strategies to assist them and propose that infrastructure improvement could facilitate many aspects of their daily lives.

These women are more aware of and proactive in addressing climate-related challenges. Their educational background and secondary employment provide them with more resources and a broader perspective. However, their dependence on a private well, which faces severe supply issues, makes them vulnerable to water scarcity (Increased Exposure to Environmental Challenges). The economic and social repercussions of these difficulties are significant, leading to conflicts and stress within their families (Dependency on Natural Resources). Additionally, the challenges of rainfed agriculture exacerbate their situation, as decreasing precipitation affects their agricultural production (Rainfed Agriculture Challenges). Their moderate success with adaptation strategies indicates some resilience, but they still require better institutional support.

Group 3: Adaptive Women: This group consists of 70 % women aged 31 to 49. 65 % of women in this group had high school education degree. In addition to their membership in the agricultural development group, they have secondary activities. These women depend on public water resources mainly provided by SONEDE (

Table 5) but they face difficulties, including frequent water cuts during the summer. They are responsible for water collection, which has social, economic, and agricultural production repercussions. This group has adopted practices and strategies they deem effective for adapting to and overcoming climate challenges. They believe that even though state strategies exist, there is a need to improve infrastructure and provide more training.

The youngest group is the most adaptive, despite facing significant challenges. Their reliance on public water resources, which are often unreliable, makes them vulnerable, especially during the summer (Increased Exposure to Environmental Challenges). The impact of rainfed agriculture also affects them, as climate variability threatens their crop yields (Rainfed Agriculture Challenges). Their dependency on natural resources, coupled with frequent water cuts, places additional strain on their economic and social well-being (Dependency on Natural Resources). They also face challenges related to access to equipment, though they have been more proactive in adopting strategies to address these issues (Vulnerability Related to Equipment). Their emphasis on the need for improved infrastructure and training reflects their forward-thinking approach.

3.3. Strategy for Coping with Climate Change

Stakeholder engagement is touted as a critical ingredient in climate change decisions and governance at deferent levels to support women in rural area and achieve equitable outcome. In Sidi Bouzid, interviews conducted with various local stakeholders, including National Institute of Agronomic Research of Tunisia (INRAT), the civil society (APEDDUB), National Agronomic Institute of Tunisia (INAT), rural women's district in the Sidi Bouzid region.as well as several officials from the Ministry of Agriculture, reveal a strong commitment to supporting Women's Agricultural Development Groups. In fact, these actors play a crucial role in providing multidimensional support to rural, facilitating their adaptation to climate change. Inter-administrative collaborations, demonstrated through agreements for maintaining essential infrastructure such as roads, improve connectivity and market access, which are vital for women facing climate and economic challenges (

Table 6)

Simultaneously, specific projects like Twiza 3 and Axsses implement integrated approaches to support women. For instance, Twiza 3 enhances market access through fairs, while Axsses works on establishing permanent sales spaces, thereby strengthening commercial opportunities despite scarce raw materials. These initiatives receive support from the regional women's delegation, agriculture authorities, and the Sidi Bouzid labor union, creating a conducive environment for women's economic development. Moreover, projects such as G3CA and Reseauclima, supported by civil society (APEDDUB) and INRAT, focus on enhancing women's resilience to climate challenges. These projects focus on training and awareness, integrating composting techniques and water management to counter water scarcity. Water storage initiatives promote efficient use of water resources in the face of climate variability. Grants support the construction of elevated rainwater tanks, thereby enhancing rural womenadaptive capacity. These efforts are bolstered by inter-administrative collaborations where ministries such as Agriculture, Environment, and Women work together to validate action plans that integrate environmental, agricultural, and gender perspectives (

Table 6). These collaborations, enriched by civil society participation through regular consultations and participatory workshops, effectively raise awareness and mobilize stakeholders, ensuring consistent and tailored project implementation.

Furthermore, in collaboration with APEDDUB, INRAT researchers have adopted a strategy focused on high-impact publications, research, policy papers, and open access policies to strengthen researchers’ scientific credibility and facilitate science-policy engagement processes. Another key output of this partnership was the development of a Best Practices Guide, supported by the INRAT, INAT, and APEDDUB teams. This guide assisted local stakeholders in integrating gender considerations into climate action and empowered women to implement natural solutions to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

4. Discussion

These findings confirmed climate variability poses significant political, economic, social, and moral challenges for rural communities [

28,

29]. In fact, climate variability is a significant threat to rural women, exacerbation their stress and worsening their already poor living conditions [

30]. Access to climatic information, women’s perceptions of climate Variability, non-agriculture activity, the multi-dimensional role of rural women in the society (water collection, Work on Agricultural Holdings ect.) and access to natural resource mainly water are among the determinants of variability of women group to climate change. By analyzing the relationship between gender and climate change in Africa. Bouchama et al. (2018)[

31] suggest that the disparity in how women are affected by climate change arises from differences in resource access and gender roles. Furthermore, results revealed that one of the most significant impacts of climate variability is the alteration in the availability of agricultural and drinking water resources. Due to the impacts of climate change, women in the Sidi Bouzid region face significant challenges, including water shortages, conflicts, and health issues. A finding in line with Md et al.(2022) [

29] confirmed that ,due to climate change, women from Atlia and Chandipur villages are required to cross 2–6.0 km approximately four times per day to provide water to the domestic cattle. The majority of respondents registered that women’s income and economic condition are adversely affected by the worsening effects of climate change . The majority of respondents reported that women’s income and economic conditions are adversely affected by the worsening impacts of climate change. In their study on the effects of climate change on rural communities, including women and youth, Chandra et al. (2017) [

32] found that each day of extreme high temperatures reduces the total value of crops produced by women farmers by 3 percent compared to their male counterparts. The effects of climate variability vary due to the vulnerability levels of different groups with each facing distinct challenges related to water access, agriculture, and the impacts of climate change. Economic, social (age), educational, and environmental factors contribute to the vulnerability of women to climate change in the Sidi Bouzid region. Women over 60 years old, with only primary education and no access to water, are the most vulnerable. In contrast, women aged 20 to 40 with secondary education are more adaptive to the effects of climate change [

33].

However, the observed vulnerability, a great resilience among these women to climate change was detected through the development of various adaptation strategies. In fact adaptation is not an independent process. It’s dépends on the role of women and engagement of stakeholders. In fact, rural women in sidi Bouzid region have diversified their income sources by turning to alternative economic activities such as poultry farming and artisanal production, demonstrating their resourcefulness and adaptive capacity. The impact of climate change on these women is profound, affecting their agricultural production, economy, and social life. Despite their determination, they continue to face major constraints, including limited access to resources and markets. The developed initiatives such as that of Battoumet, collaborating with a company specializing in resilient seeds for crop development, illustrate the women's willingness to find sustainable solutions [

34,

35]. This underscores the importance of increased support from supportive organizations and the integration of climate resilience strategies tailored to the realities of rural women in Sidi Bouzid.

Furthermore, a wide range of stakeholder have supported rural women among different strategy. In fact civil society, national institute of research and university play a crucial role in this well-structured collaboration network to address climate challenges. These actors provide essential knowledge and resources, enriching the overall understanding of local dynamics. However, to further strengthen resilience, it would be beneficial to expand these connections to other actors, such as the ministry of agriculture representative and the forest management of Sidi Bouzid, to maximize synergies and positive impacts of climate initiatives.

Interviews with regional and national stakeholders have highlighted efforts in inter-administrative and research collaboration and active participation of civil society in awareness raising, consultation, and mobilization of stakeholders involved in the adaptation of rural women to climate change [

28]. These interactions show that, while positive initiatives are in place, there are still challenges to overcome to ensure effective participation of civil society in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of initiatives related to rural women and climate change.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of climate change on rural women in Sidi Bouzid region and the Stakeholders adaptation strategies to mitigate the impact of climate change on rural women. To achieve this objective, a rigorous analysis approach combining descriptive and typological analyses was opted by using the Multiple Components Analysis (MCA) method. This approach allowed us to develop our own indicators, largely aligned with those derived from Marie-Joëlle Fluet's (Marie, 2006) fieldwork in her thesis.

Our findings underscore that climate change has significant impacts on the women of the "Battoumet" and "Magdiyet» agriculture development group in Sidi Bouzid, affecting various aspects of their daily lives. Water scarcity leads to family tensions and increased stress, compromising agricultural and domestic activities, and reducing household incomes. Droughts and precipitation variations deteriorate crops and limit access to food resources, increasing the economic vulnerability of women dependent on natural resources.

Limited access to clean water, with 20% of women deprived of direct access and 60% relying on public resources prone to interruptions, exacerbates financial hardships. Inadequate agricultural equipment reduces productivity and increases operational costs, accentuating disparities between rural women. Despite these challenges, women in agriculture development group demonstrate resilience by developing adaptation strategies such as poultry farming and artisanal production, although limited access to resources and markets remains a major obstacle affecting their social and economic well-being.

This work goes beyond analyzing the impacts of climate change from women's perspectives. To strengthen resilience against water scarcity and climate challenges a wide range of stakeholder have supported rural women among different strategy. This research highlighted the crucial role of civil society and associations, emphasizing the importance of a well-structured collaboration network. Extending these connections to other actors such as the Sidi Bouzid Forest and international organizations would maximize synergies and positive impacts of climate initiatives, crucial for supporting women's resilience.

Furthermore, in the present study, only co production of knowledge strategies were investigated. It is suggested that in future studies, governmental adaptation interventions such as infrastructure development, removal of organizational barriers, nd extension infrastructures for rural women also be investigated.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

the research was supported by the RESEAUClima project led by APEDDUB in partnership with INRAT and funded by South South North (SSN), which is a component of the VCA programme.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported first by the RESEAUClima project, led by APEDDUB and by South South North (SSN), which is a component of the VCA programme. In the frame of this project partnerships was signed: between APEDDUB and INRAT. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Najwa Bouraoui, president of the APEDDUB association, and to Professor Mondher Ben Salem the director of INRAT for they support and encouragement. Our sincere thanks also go the reviewers for their valuable feedback and insightful critiques.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| G3CA: |

Gender Climate Change and Community Adaptation |

| INRAT: |

National Institute of Agronomic Research of Tunisia |

| INAT : |

National Agronomic Institute of Tunisia |

References

- World Bank (2007), World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development, Washington DC: World Bank.

- The Food and Agriculture Organization. (2011). The state of food and agriculture – 2010-2011. Women in agriculture: Closing the gender gap for development. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i2050e/i2050e00.htm.

- Amenyah, I. D., & Puplampu, K. P. (2013). Women in agriculture: an assessment of the current state of affairs in Africa.

- FAO,2024. https://www.fao.org/4/X0250E/x0250e03.htm.

- ORAM P. A., 1989 Sensitivity of agricultural production to climatic change, an update. Climate and Food Security, IRRI, Manila, The Philippines: 25-44.

- HANSEN J. W., 2002 Realizing the potential benefits of climate prediction to agriculture: issues, approaches, challenges. Agricultural Systems, 74 : 309-330.

- FAO, 2003 The state of food insecurity in the world. Rome, Food and Agricultural Organisation Author 1, A.B. (University, City, State, Country); Author 2, C. (Institute, City, State, Country). Personal communication, 2012.

- Yadav, S. S., & Lal, R. (2018). Vulnerability of women to climate change in arid and semi-arid regions: The case of India and South Asia. Journal of Arid Environments, 149, 4-17.

- Bhadwal, S., Sharma, G., Gorti, G., & Sen, S. M. (2019). Livelihoods, gender and climate change in the Eastern Himalayas. EnvironmentalDevelopment, 31, 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Schwerhoff, G., & Konte, M. (2020). Gender and climate change: Towards comprehensive policy options. In Women and sustainable human development (pp. 51–67). Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Eastin, J. (2018). Climate change and gender equality in developing states. World Development, 107, 289–305. [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., &Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 74.

- OXFAM, 2015. Annual report. https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/story/oxfam_annual_report_2015_-_2016_english_final_0.pdf.

- ONU Femmes. (2015). L'autonomisation économique: quelques faits et chiffres. https://www.unwomen.org/fr/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures.

- Chigbu U (2013) Rurality as a choice: towards ruralising rural areas in subSaharan African countries. Dev South Afr 30(6):812–825.

- Ifabiyi I, Adedeji A (2014) Analysis of water poverty for irepodun local government area (Kwara state, Nigeria). Geogr Environ Sustain 7(4):81–94.

- Labiadh I 2014. Patrimoine forestier et stratégie de développement territorial. Cas du groupement féminin de développement agricole GFDA Elbaraka dans le Nord-ouest de la Tunisie. In : Grison JB, Rieutort L, eds. Valorisation des savoir-faire productifs et stratégies de développement territorial : patrimoine, mise en tourisme et innovations sociales. Saugues (France): Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, 14 p. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01216828/document.

- CREDIF, 2015. Genre et changement climatique : Une vision différente. https://www.cilg-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/La-Revue-du-CREDIF-n54-FR.pdf.

- Houloul, 2024. Impact of Water Scarcity and Climate Change on Rural. Policy brief. https://houloul.org/en/2024/02/09/impact-of-water-scarcity-and-climate-change-on-rural-women/.

- Afi, M. (2018). Resilience Assessment of Social-Ecological Systems in MENA Region: An Application of Tri-Capital Framework in Jordan, Tunisia & Morocco (Doctoral dissertation, Agronomica).

- Heni, F., & Dhieb, M. (2023). Les disparités socio-économiques dans le gouvernorat de Sidi Bouzid (centre ouest de la Tunisie). Études caribéennes, (56).

- Abebe, T., Bekele, L., & Hessebo, M. T. (2022). Assessment of Future Climate Change Scenario in Halaba District, Southern Ethiopia. Atmospheric and Climate Sciences, 12(2), 283-296.

- UN Women Watch (2022), “Women, gender equality and climate change”, available at: www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/factsheet.html (accessed 3 April 2021).

- Howard, G., Calow, R., Macdonald, A. andBartram,J. (2016), “Climate change and water andsanitation: likely impacts and emerging trends for action”, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, Vol. 41 No.1, pp.253-276.

- Wan, J., Li, R., Wang, W., Liu, Z. and Chen, B. (2016), “Income diversification: a strategy for rural region risk management”, Sustainability, Vol. 8 No. 10. [CrossRef]

- NM, Q. (2022). A method for measuring women climate vulnerability: a case study in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 14(2), 101-124.

- Mulema, A. A., Cramer, L., & Huyer, S. (2022). Stakeholder engagement in gender and climate change policy processes: Lessons from the climate change, agriculture and food security research program. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6, 862654.

- Moayedi, M., & Hayati, D. (2023). Identifying strategies for adaptation of rural women to climate variability in water scarce areas. Frontiers in Water, 5, 1177684.

- Md, A., Gomes, C., Dias, J. M., & Cerdà, A. (2022). Exploring gender and climate change nexus, and empowering women in the south western coastal region of Bangladesh for adaptation and mitigation. Climate, 10(11), 172.

- Georgalakis, J. (2020). A disconnected policy network: The UK’s response to the Sierra Leone Ebola epidemic. Social Science & Medicine, 250, 112851.

- Bouchama, N., Ferrant, G., Fuiret, L., Meneses, A., & Thim, A. (2018). Gender inequality in West African Social Institutions. West African Papers, No. 13, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A., McNamara, K. E., Dargusch, P., Caspe, A. M., & Dalabajan, D. (2017). Gendered vulnerabilities of smallholder farmers to climate change in conflict-prone areas: A case study from Mindanao, Philippines. Journal of rural studies, 50, 45-59.

- Akinsemolu, A. A., & Olukoya, O. A. (2020). The vulnerability of women to climate change in coastal regions of Nigeria: A case of the Ilaje community in Ondo State. Journal of Cleaner Production, 246, 119015.

- Akinbami, C. A. O. (2021). Climatepreneurship: Adaptation Strategy for Climate Change Impacts on Rural Women Entrepreneurship Development in Nigeria. In African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation (pp. 2143-2168). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Etim NA, Etim NN (2019) Rural farmers’ adaptation decision to climate change in Niger Delta region, Nigeria. In: Handbook of climate change resilience. pp 1035–1049. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).