1. Introduction

Communities are the urban units most intimately connected to residents’ daily lives and represent the ‘last mile’ of national governance, underscoring their great significance [

1]. Offering good, smart renewal project for old communities bear the great responsibility of the foundational social governance system at the national level, while it also embodies the public’s longing for a better life [

2]. It emerges as a crucial breakthrough in the reform of local governance mechanisms [

3,

4]. Residents’ sense of gain is a critical criterion for evaluating the performance of old-smart renewal community governance [

5,

6]. Community residents’ sense of gain stems from their recognition of old-smart renewal community services’ actual obtained and subjective feeling. Qi, and Guo suggested [

7] that the sense of gain represents a synthesis of objective gain and subjective feeling, emphasizing the importance of material affluence and spiritual well-being. As a crucial yardstick, improving the residents’ sense of gain is essential for enhancing the governance performance of old-smart renewal communities.

To improve the performance of old-smart renewal communities, the government has formulated incentive policies and invested funds to support old-smart renewal community development [

8]. However, the participation and satisfaction of residents in old-smart renewal communities remain low because of these constraining factors encompassing national policies, the functional capabilities of old-smart renewal community services, and the knowledge reserves of residents. Zhang, et al. [

9] emphasized that institutional norms serve as an effective instrument for old-smart renewal community governance and improve the resident’s sense of gain. Governmental institutions and policy supports offer pivotal safeguards for promoting old-smart renewal communities [

10]. The vision and objectives set by the governments provide a clear direction for developing old-smart renewal communities. Shen, et al. [

11] found that information technology is an effective tool for enhancing community residents’ quality of life and convenience. Old-smart renewal community managers should provide convenient hardware and software to facilitate resident’s use of smart systems. Zhou and Lund indicated that affordable smart operation platforms, convenient operational skills, and knowledge reserves enhance the residents’ enthusiasm for participating in old-smart renewal community development [

12]. Namely, institutional elements and technique values affect residents’ sense of gain in old-smart renewal communities.

A framework is developed to improve old-smart renewal community residents’ sense of gain by adding institutional environment and technique value as antecedents. The sense of gain, which refers to the satisfaction residents feel towards the smart services provided by old-smart renewal communities, is also affected by factors such as the institutional environment and information technology [

13]. Instrumentalist researchers indicated that digital transformation empowers old-smart renewal communities, with information technology facilitating the lives of community residents and humanized information services enhancing their sense of well-being [

14]. It emphasizes the role of technique value in old-smart renewal community governance yet overlooks the counteractive influence of the institutional environment on the application of smart technology. In institutional governance research, the institutional environment exerts a constraining effect on technology, manifesting as both institutional support and institutional constraints that influence users’ intention and behaviour in technology adoption [

15,

16,

17]. Old-smart renewal community residents make behavioural decisions based on their perceptions of the community’s institutional environment and the conveniences it offers [

18]. Existing studies identified the impact of institutional environment and technique value on residents’ sense of gain, but the underlying mechanisms have yet to be further identified. To fill the gap, this study explores the effects of institutional environment and technique values on the old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain. It enriches the antecedents of community residents’ sense of gain and expands the relationships between the institutional environment and their sense of gain.

2. Theoretical Foundation and Hypotheses Development

2.1. An Overview of Resident’s Sense of Gain

The residents’ sense of gain is essential to community governance and is becoming a hot topic. It reveals the resident’s feelings about the quality and satisfaction of old-smart renewal community services. Residents’ sense of gain is defined as the residents’ feelings of the objective obtain and subjective feeling [

19]. Objective gain refers to facts that exist independently of individual feelings and perspectives. It can be measured in terms of observation and verification. The objective gain does not depend on personal feelings or interpretations but presents objective facts. Subjective feeling refers to an individual’s internal feelings and sensations, which are the direct perception and internal response to the facts [

20]. It is usually related to an individual’s emotions, preferences, attitudes, and beliefs. The subjective feeling is personal and varies from person to person. The old-smart renewal community residents’ sense of gain comprises objective obtains and subjective feeling [

21]. Objective gain focuses on residents’ perception of benefits acquired from the old-smart renewal communities, such as information, resources, and community services. It manifests that the old-smart renewal community can improve its residents’ living quality and facility management service level by providing information services and conveniences [

22]. Subjective feeling refers to the sense of satisfaction that community residents derive from the smart services and amenities, which is reflected in the residents’ satisfaction, experience, and identification. Old-smart renewal communities’ objective convenience and value enhances the residents’ feelings. Residents realize that the e-commerce platforms and smart facility management services provided by old-smart renewal communities can save time and energy and recommend old-smart renewal community services to their neighbours and colleagues. Thus, hypotheses (H) 1 is supported as follows:

H1: Old-smart renewal community residents’ objective obtains positively influence their subjective feeling.

2.2. Effects of Institutional Elements on Technical Values in Old-Smart Renewal Communities

Residents’ perception of old-smart renewal community governance is primarily obtained through the institutional environment created by the community and its technical values. Regarding the institutional environments, policies regulate the service content of basic-level governance departments, providing residents with effective smart services and digital platforms [

23]. It enhances community resource allocation, service quality, and management performance by improving old-smart renewal communities’ technical values. Governments formulate incentive policies to develop effective old-smart renewal community service platforms, such as financial subsidies and investment funding [

24]. It provides residents with convenient and humanized community services by developing service circles that are convenient and beneficial to the people. Moreover, governments share with residents the knowledge, operating procedures, and methods of smart renewal project for old communities, reducing the time and energy required to learn and making it easy for residents to use various platforms within old-smart renewal communities. Thus, H2a and H2b are set as follows:

H2a: Institutional environment positively affects the perceived usefulness in the old-smart renewal communities.

H2b: Institutional environment positively affects the perceived ease of use in the old-smart renewal communities.

The available convenient conditions in the community (such as information technology, knowledge, and smart platforms) provide a prerequisite for residents to use innovative service platforms in old-smart renewal communities. The technology acceptance model (TAM) indicates that the convenient conditions affect residents’ perceived usefulness and ease of use of new technologies. Legrisa, et al., [

25] suggested that available conveniences benefit users by allowing them to employ new technologies to improve work efficiency. Community managers create a convenient usage environment for residents by providing digital, smart, and interactive community services, making it easy for residents to use. Besides, grassroots government departments provide professional knowledge to help residents understand the usefulness and convenience of smart technologies in old-smart renewal communities [

26]. In contrast, convenience community services reduce residents’ time and energy learning to use smart technologies, encouraging them to embrace in the old-smart renewal communities. H3a and H3b are set as follows:

H3a: Convenient condition positively affects the residents’ perceived usefulness in the old-smart renewal communities.

H3b: Convenient condition positively affects the residents’ perceived ease of use in the old-smart renewal communities.

2.3. The Mediating Effects of Technical Values in the Old-Smart Renewal Communities

The concept of perceived technical values mainly refers to users’ perceptions of usefulness and the ease of use of the technologies, including perceived usefulness and ease of use [

27,

28]. Perceived usefulness refers to the belief of old-smart renewal communities’ residents that applying smart services can effectively improve the quality of life and living standards. Perceived ease of use refers to the perception of the ease of operability of the old-smart renewal community service systems by old-smart renewal community’s residents when using it [

29]. TAM suggests that users tend to use simple technologies, and operability can affect users’ judgments of its functionality. If learning a new technology requires a lot of time and effort, the utility generated by that technology can be weakened. Thus, H4 is set as follows:

H4: The perceived ease of use positively affects the residents’ perceived usefulness in old-smart renewal communities.

As for the various smart services available in community facilities, residents choose devices and technologies with great convenience and performance to enhance the living environment and service quality. Neirotti, et al. [

30] pointed out that digital management platforms can effectively solve community governance issues such as information blockage and low management efficiency, providing residents with smart and convenient community services, which increases community residents’ sense of gain. Residents often choose information service tools with high functionality and operability to solve daily problems. Thus, H5a and H5b are set as follows:

H5a: Perceived usefulness positively mediates the relationship between convenience condition and old-smart renewal community resident’s objective gain.

H5b: Perceived usefulness positively mediates the relationship between convenience condition and old-smart renewal community resident’s subjective feeling.

As the proponent of old-smart renewal communities, the government designs community governance mechanisms and formulates proactive policies to enhance the gains of community residents. The government regularly holds lectures and policies to raise residents’ awareness about using smart services [

31]. Moreover, the government provides financial subsidies for eligible communities with relevant laws and regulations to enhance old-smart renewal community development, which offers convenient and safe community services for old-smart renewal communities’ residents, which improves their objective gain and subjective feeling [

32,

33,

34]. Besides, the government formulated operation guidelines for smart service platforms and selected functional information technologies for pilot projects, increasing residents’ gains of old-smart renewal community’s services [

35,

36]. However, policies formulated by the government only sometimes receive positive feedback from community residents. For example, the government provides financial subsidies to improve old residential areas’ information facilities and equipment, enhancing the community’s digital management capabilities [

37]. However, several digital technologies are restricted because community residents have yet to enjoy the convenience of smart services, reducing their willingness to use them. Thus, H6a and H6b are set as follows:

H6a: Perceived usefulness positively mediates the relationship between the institutional environment and the old-smart renewal community resident’s objective gain.

H6b: Perceived usefulness positively mediates the relationship between the institutional environment and old-smart renewal community resident’s subjective feeling.

The community provides residents with convenient community resources and information technology equipment. However, some residents are unwilling to use these smart services due to a lack of operational experience and knowledge [

38]. Residents would prefer less effort in learning about old-smart renewal communities -related expertise and operational skills. Residents believe that the operation process of smart service platforms is complex and updates quickly, and the cost of learning old-smart renewal community’s technologies and operational skills is too high, so they prefer to maintain the original way of dealing with life problems. Although convenient conditions are provided for the community residents, no high or low sense of objective gain and subjective feeling are obtained due to the need for much effort to use these community technologies. Thus, H7a and H7b are set as follows:

H7a: Perceived ease of use positively mediates the relationship between convenient conditions and old-smart renewal community resident’s objective gain.

H7b: Perceived ease of use positively mediates the relationship between convenient conditions and old-smart renewal community resident’s subjective feeling.

The government establishes guidelines and allocates financial resources to enhance the convenience and operability of old-smart renewal community’s service systems, increasing residents’ approval and participation in old-smart renewal community development. Governance organizations develop operation manuals for old-smart renewal community’s service systems to reduce the learning costs for residents and improve their sense of gain from using smart technologies. Moreover, governments regularly provide guidance and training to residents to enrich their knowledge of old-smart renewal communities, reducing negative emotions associated with using smart technologies [

39]. The government encourages innovation in related industries such as smart home and security monitoring through policies, promoting the development of user-friendly and highly compatible information products to improve the ease of use of old-smart renewal community’s services, increasing residents’ sense of gain from using smart online platforms. Thus, H8a and H8b are set as follows:

H8a: Perceived ease of use positively mediates the relationship between the institutional environment and old-smart renewal community resident’s objective gain.

H8b: Perceived ease of use positively mediates the relationship between the institutional environment and old-smart renewal community resident’s subjective feeling.

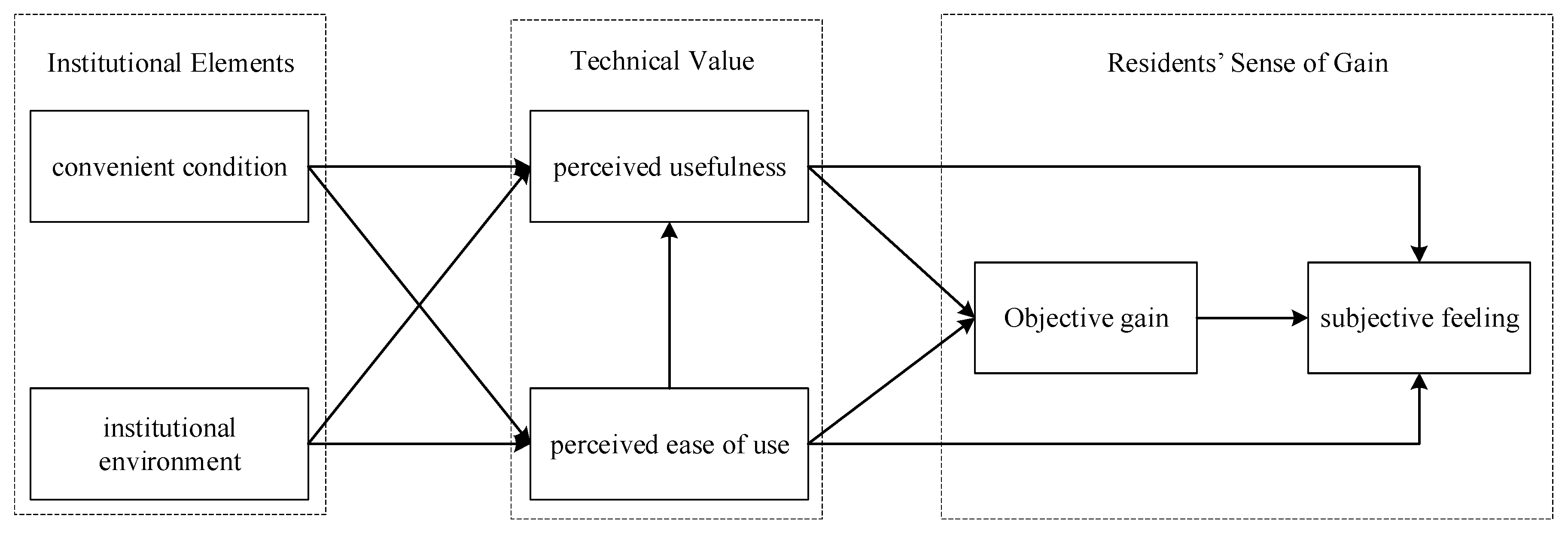

Based on these hypotheses above, a theoretical framework is developed to explore the relationships between institutional elements, technical values, and old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain, as

Figure 1 shows.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Procedure and Sample Characteristics

A questionnaire was designed to test the relationships between institutional elements, technical values, and residents’ sense of gain in the old-smart renewal communities. Data were collected online and offline. The survey questionnaire consists of three parts: antecedents (e.g., convenient conditions, institutional environment, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness), resident’s sense of gain (e.g., objective gain and subjective feeling), and basic information about the respondents. A five-point Likert scale was used to measure the variables (1=Strongly Disagree, 3=Neutral, 5=Strongly Agree). A total of 15 experts were interviewed to ensure the validity of the questionnaire content, with five experts with rich experience in old-smart renewal communities and ten residents from the old-smart renewal community residents. The interview mainly focuses on the applicability and validity of the questionnaire content and optimizes the questionnaire content based on the interview results. After pilot testing, this study selected residents old-smart renewal communities in Shandong Province as data collection samples and conducted random sampling.

A total of 1000 questionnaires were distributed from January 31, 2024, to April 30, 2024, and 587 responses were collected. 384 valid questionnaires were obtained (with a valid rate of 66.4%) by removing samples with less than six months of old-smart renewal community living experience, response times under 240 seconds, and ages under 18. All 384 valid respondents had at least six months of experience living in an old-smart renewal communities and had used three or more smart services listed in the questionnaire. Males accounted for 51.1%, and females accounted for 48.9%. The respondents covered various age groups, mainly concentrated in the 18-40 age range (57.2%), with these over 60 years old accounting for a low proportion of only 1.7%. Most respondents (74.5%) had a college degree or higher education level.

3.2. Measurements

Four steps are conducted to obtain measurement items. (1) The popular measures are first selected from the literature reviews based on high sites. At least three reflective indicators are used to measure each latent variable. (2) Then, the content validity of the variable is verified. The selected scales are translated into Chinese, and two experts are interviewed to verify the content of the latent variables and the fitness of its observed items. These experts identify the item that does not clearly express the accurate meaning. They evaluate the questionnaire based on the fitness of observed items to the measured construct. (3) Next, a pilot survey is conducted to test the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. (4) Finally, the measures are obtained and then used to design the questionnaire. Survey items are assessed on a Likert’s five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (significantly), with a midpoint of 3 (moderately) in this study.

Convenient condition: Convenient condition refers to the accessible resource conditions provided by old-smart renewal communities for residents, such as information technology equipment, information services, and professional service personnel. According to Venkatesh et al. [

40], four items were used to measure the convenient conditions, with an example being: “It provides us with the necessary resources to use old-smart renewal community services, such as equipment, software, and smart service platforms”.

Institutional Environment: Institutional environment refers to the various regulations, rewards, and operational guidelines established by the government to promote old-smart renewal community development [

41]. Four items were selected to measure the institutional environment. An example item is “the street office where our community is located, which prints national policies into brochures and promotes them on public platforms such as public cultural columns and community homes”.

Perceived Usefulness: Perceived usefulness refers to the resident’s judgment of the quality and level of old-smart renewal community services, and it is the perception of the usefulness of old-smart renewal community services by residents. According to Venkatesh [

42], four items were used to measure perceived usefulness. An example item is “the community services provided by the old-smart renewal communities, which have brought convenience to my life”.

Perceived Ease of Use: Perceived ease of use refers to community users’ perception of the ease or difficulty of using old-smart renewal community services. Based on Venkatesh [

42], four items were used to assess perceived ease of use. An example item is: “It is easy for me to learn about the knowledge related to old-smart renewal community devices”.

Objective gain: Objective gain refers to the objective evaluation made by the residents of the old-smart renewal communities regarding the community resources and smart services provided by the community. This study draws on the definition of a sense of gain [

6,

8] and incorporates feedback from old-smart renewal community experts, using four items to measure the objective gain of old-smart renewal community’s residents. An example item is: “The old-smart renewal communities where I live provides infrastructure that meets my daily living needs”.

Subjective feeling: Subjective feeling refers to the resident’s satisfaction, experience, positive emotions, and other subjective feeling towards the smart services provided by the old-smart renewal communities and the level of old-smart renewal community’s development. This study draws on the definition of the sense of gain [

6,

8] and incorporates feedback from old-smart renewal community experts and residents, using four items to measure the subjective feeling of old-smart renewal community’s residents. An example item is: “The smart services provided by my community offer me a pleasant living experience”.

3.3. Analytical Strategy

This study checked the reliability and validity using Cronbach’s а reliability, content validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The reliability level was tested using Cronbach’s α value. A high reliability is suggested when the threshold exceeds 0.7 [

43]. Tests were conducted to ascertain validity using goodness-of-fit, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. A model had a goodness-of-fit with χ2/df ≤ 5.0, incremental fit index (IFI) ≥ 0.90, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.90, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.90, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08. A good convergent validity was obtained with composite reliability (CR) values ≥ 0.7 and average variance extracted (AVE) ≥ 0.5 [

44,

45]. Discriminant validity was verified when the square root of the AVE value was all greater than the absolute value of the inter-construct correlations. Path analysis and moderated mediation analysis were then conducted to test the hypotheses using Mplus 8.0 software. Regression analysis was used to test the relationship between latent variables [

46]. Third, the mediating effects of technical values were tested using the bootstrapping test. The mediating role was verified when a 95% bootstrap confidence interval did not include zero.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Validation

The Cronbach’s alpha for convenient conditions, institutional environment, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, objective gain, and subjective feeling are 0.819, 0.915, 0.885, 0.862, 0.876, and 0.883 (see

Table 1), revealing that all the measures are good because Cronbach’s alpha value of each construct exceeded the acceptable value of 0.7. As

Table 1 shows, the CR values of each construct exceed the acceptable value of 0.7, and the AVE values are all higher than the acceptable 0.5. The factor loading of the variables also exceeds 0.7.

In addition, the square roots of AVE are all greater than the absolute value of the inter-construct correlations (see

Table 2), suggesting an excellent discriminant validity of these constructs. The fit indexes show that the six-factor model fits the data, with χ^2/df=3.083, CFI=0.916, IFI= 0.916, TLI=0.904, and RMSEA=0.074.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.2.1. The Direct Effect Testing

Mplus 8.0 software was used to test the proposed hypotheses. The results are shown in

Table 3. Objective gain positively affects subjective feeling (r=0.622, P<0.001). Namely, H1 is supported. Perceived ease of use positively affects perceived usefulness (r=0.369, P<0.001), revealing that H4 is supported. Perceived usefulness positively affects objective gain (r=0.272, p<0.001) and subjective feeling (r=0.221, p<0.001). Perceived ease of use has a positive effect on objective gain (r=0.468, p<0.001) and subjective feeling perception (r=0.116, p<0.001). Namely, perceived ease of use and usefulness significantly affect old-smart renewal community residents’ sense of gain.

4.2.2. The Mediating Effect Testing

Bootstrapping testing was used to examine the mediating effects of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use on the relationships between convenient conditions, institutional environment, and the old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain. Perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between the institutional environment and the resident’s sense of gain. As

Table 4 shows, perceived usefulness positively affects objective gain and indirectly affects subjective feeling (r=0.073, p<0.05). It demonstrates that institutional environment influences the objective gain of community residents through perceived usefulness and further affects their subjective feeling. However, the mediating effect of perceived usefulness on the relationship between the institutional environment and objective gain was not supported. At the same time, the mediating effect of perceived usefulness on the relationship between convenient conditions and subjective feeling was also not supported.

Table 4 shows that perceived ease of use mediated the relationship between convenient conditions and the sense of gain (r=0.129, p<0.05). perceived ease of use mediates the relationships between convenient conditions and the resident’s subjective feeling, supporting H7b. Perceived ease of use and objective gain formed a serial mediation, affecting the relationship between convenient conditions and subjective feeling (r=0.099, p<0.001), supporting H7a. Moreover, it was found that perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and objective gain formed a serial mediation, affecting the relationship between convenient conditions and subjective feeling (r=0.063, p<0.01).

Perceived ease of use mediated the relationship between the institutional environment and resident’s sense of gain. As

Table 2 shows, perceived ease of use mediated the relationship between the institutional environment and subjective feeling (r=0.049, p<0.05), demonstrating that the institutional environment influences the subjective feeling of community residents through perceived ease of use, supporting H8b. Perceived ease of use and objective gain form a serial mediation, affecting the relationship between the institutional environment and subjective feeling (r=0.038, p<0.05). It indicates that the institutional environment impacts residents’ objective gain through perceived ease of use, indirectly affecting their subjective feeling.

5. Discussions

Technical value directly affects the old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain, while institutional elements do not. Old-smart renewal community is provided many emerging information technologies to enhance the convenience of residents’ lives. Existing research has explored the antecedents of new technology adoption from utilitarian and institutional perspectives, indicating that institutional elements (such as institutional environment and convenient conditions) and technical values (such as perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) influence the promotion and application of new technologies [

47,

48]. Our study found that the roles of institutional elements and technical values differ in technology promotion. The results show that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use directly affect the sense of gain, while the institutional environment and convenient conditions influence old-smart renewal community resident’s technical values. This is attributed to the fact that institutional environments and convenient conditions can affect residents’ cognition but only directly increase their sense of gain if they directly benefit from the old-smart renewal communities. Convenient conditions and institutional environments influence resident’s value perceptions of old-smart renewal communities. On the one hand, the convenient conditions provided by old-smart renewal communities make residents aware that smart technologies can facilitate their lives; the available convenient conditions (i.e., knowledge, professionals, skills, etc.) also increase residents’ confidence in using old-smart renewal community online applications. On the other hand, practical policies lead residents to accept smart technologies. The government has improved resident’s cognition of the performance and efficiency of old-smart renewal communities by formulating policies and vigorous promotion. The findings suggest that relevant departments need to develop convenient conditions and institutional environments to change residents’ perceptions of the utility and efficiency of smart technologies. Our study enriches the significance of institutional elements and technical values in new technology acceptance models by distinguishing their action targets.

Technical values (i.e., perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) serve as mediators that enrich the relationship between institutional elements and the old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain. Existing research indicates that convenient conditions and the institutional environment can influence the acceptance of new technology, but the relationship between these factors and technology use performance has yet to be explored [

49]. Our study found that the mediating effects of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are distinct. Perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between institutional elements (such as convenient conditions and institutional environments) and objective gain. In contrast, perceived ease of use mediates the relationship between institutional elements (such as convenient conditions and institutional environments) and the objective gain, as well as the relationship between institutional elements (such as convenient conditions and institutional environments) and subjective feeling. It is attributed to the fact that perceived usefulness focuses on directly facilitating residents’ use of new technologies in old-smart renewal communities, improving the efficiency of residents’ lives, which is reflected in an increase in objective gain. Perceived ease of use facilitates residents’ use of new technologies in old-smart renewal communities and reduces the psychological burden on residents when using smart technologies. Relevant departments can improve residents’ objective gain by conducting public opinion surveys to select and develop online platforms with high resident demand; meanwhile, they can print brochures and develop operation manuals to facilitate residents’ effective operation of various smart functions. Our study enriches the role of institutional elements in the utility of new technology acceptance models by verifying the mediating role of technical values on the relationships between institutional elements and users’ sense of gain from the latest technology implementation.

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study enriches the literature on the antecedents of resident’s sense of gain. Existing studies indicated that the resident approval is an essential factor in promoting the development of old-smart renewal community [

50]. However, more research is needed to explore its antecedents. Based on the TAM, this study examines the role of institutional elements and technical values in old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain, pointing out that institutional elements (i.e., institutional environment and convenient conditions) indirectly affect the resident’s sense of gain. In contrast, technical values (i.e., perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) directly affect the resident’s sense of gain. It enriches the research on the antecedents of the new technology implementation in the old-smart renewal community’s context.

Our study explores the path of institutional elements on the resident’s sense of gain by expanding the mediators. Existing research indicated that community convenience and institutional environment affect residents’ willingness to participate in developing old-smart renewal community [

51], but the detailed path has yet to be analysed. By integrating research on utilitarianism and institutionalism for technology acceptance, this study explores the factors affecting the sense of gain among old-smart renewal community residents, pointing out that community convenience, institutional environment, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use are essential antecedents affecting the sense of gain among old-smart renewal community residents. It is found that perceived ease of use mediates the relationship between convenient conditions, institutional environment, and subjective gain. Moreover, this study verifies the serial mediating effect of perceived ease of use on objective gain, indicating that convenient conditions and institutional environments affect perceived ease of use, then affect resident’s objective gain and influence the subjective feeling of community residents. In addition, this study verifies the serial mediating effect of perceived usefulness on objective gain, pointing out that the institutional environment affects the subjective feeling of community residents through the serial mediating effect of perceived usefulness and objective gain. The study expands the path of the institutional environment on the sense of gain among community residents and enriches the related research on urban governance mechanisms.

6.2. Practical Implications

Government-related departments should provide institutional guarantees for community residents to use smart services. First, old-smart renewal community managers should provide the residents with equipment, information platforms, and other conditions, laying the foundation for users to utilize smart services. For example, old-smart renewal community should be equipped with essential security devices, smart parking garages, and other information technology equipment, and professional technical personnel skilled in smart technology should be laid in place to lay the foundation for residents to use smart platforms. Secondly, the government needs to establish incentive mechanisms for old-smart renewal community governance to encourage residents to participate in constructing smart renewal project for old communities. Thirdly, grassroots community governance departments, such as neighbourhood offices, should regularly organize events to promote knowledge about old-smart renewal community applications and prepare materials such as brochures on old-smart renewal community service platforms, operation guides, and service manuals to popularize understanding of smart services among community residents. Lastly, the government can promote the development of related industries such as smart homes and security monitoring, increase R&D investment in information technology related to old-smart renewal communities, and cultivate professional talent by increasing financial input and establishing incentive mechanisms.

Emphasize the practicality and convenience of the construction of old-smart renewal community service platforms. The study results indicate that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use mediate the effect of the institutional environment on the sense of gain among old-smart renewal community residents. Therefore, during the construction process of smart renewal project for old communities, it is crucial to focus on the practicality of smart service functions and the convenience of operational processes. Firstly, grassroots community managers should research the smart service needs of community residents, identify their needs in areas such as education, healthcare, elderly care, and home living, and design corresponding online services. Secondly, community management departments should select user-friendly and highly compatible information technology tools and service processes and provide accompanying video tutorials and operation manuals to reduce the learning costs for community residents when using smart services. Thirdly, the government should establish recommendatory standards to encourage software developers, equipment suppliers, and other related companies to provide products and services with solid compatibility, thereby reducing user learning costs.

Develop a performance evaluation index system for old-smart renewal community governance based on the content structure of community residents’ sense of gain and assess the community governance performance of grassroots community management departments. The sense of gain among old-smart renewal community residents is essential for determining community governance performance. The government should design a performance evaluation index system for old-smart renewal community governance based on the content structure of residents’ sense of gain, including both the objective gain and subjective feeling of community residents. This study indicates that constructing an evaluation index system for the sense of gain among old-smart renewal community residents should include antecedents and performance. Firstly, a measurement index system for the convenient conditions and institutional environment will be designed to examine the institutional environment for the old-smart renewal communities. Secondly, the urban governance managers should focus on the perceived usefulness and ease of use of smart technology, and eliminate the dilemma of it being merely a “showpiece”. Thirdly, the objective gain and subjective feeling of community residents should be evaluated and also viewed as important indicators to reveal the governance performance. The government can formulate official guiding documents and recommendatory standards to provide a reference for designing assessment indicators for old-smart renewal community development by grassroots community governance.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has conducted a rigorous research design, but areas still require improvement. Firstly, to ensure the authenticity and reliability of data acquisition, this study selected old-smart renewal communities in Shandong Province as sample for data collection considering that this province is making a big effort to develop smart cities and renovate older neighborhoods. Future research will collect samples from different regions to analyze the impact of regional factors on the old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain. Secondly, this study explores the effects of the institutional environment and technical value on the sense of gain without considering the role of residents’ subjective initiative. Future research will consider a comprehensive set of factors, including the institutional environment and residents’ subjective initiative, to analyze the pathways for enhancing the sense of gain. Thirdly, this study primarily explores the relationships between the institutional environment, technical value, and old-smart renewal community resident’s sense of gain without considering several factors such as age, community culture, neighborhood relationships, perceived fairness, community governance mechanisms, and the level of smart technology, which may also impact the sense of gain. Future research will build upon the theoretical model proposed in this study, incorporate the aforementioned contextual variables, and enrich the related research on urban governance mechanisms.

7. Conclusions

Using path analysis, our study investigates the effects of institutional elements on the old-smart renewal community residents’ sense of gain. The study enriches the relations between the institutional elements, technical values, and residents’ sense of gain by identifying the mediators. The findings reveal that technical value (such as perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) directly affects the resident’s sense of gain, while institutional elements (such as convenient condition and institutional environment) do not. Meanwhile, technical values (i.e., perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) serve as mediators that enrich the relationships between institutional elements and old-smart renewal community residents’ sense of gain. This study enriches TAM by identifying the significance of institutional elements and technical values. It als expands institutional theory by verifying the significance role of institutional elements in the new technology implementation. Meanwhile, this study provides practical roadmaps to promote old-smart renewal community implementation and improve resident’s sense of gains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xiaoyan XUE.; methodology, Xiaoyan XUE; software, Xiaoyan XUE; validation, Hong XUE; formal analysis, Xiaoyan XUE; investigation, Hong XUE; writing—original draft preparation, Xiaoyan XUE; writing—review and editing, Hong XUE. Funding: This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the interviewees who took the time to complete the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coe, A.; Paquet, G.; Roy, J. E-Governance and Smart Communities. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2001, 19, 80–93. [CrossRef]

- Batty, M., et al., Smart cities of the future. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 2012. 214(1): p. 481-518. [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I.; Cobo, C. Unplugging: Deconstructing the Smart City. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 23–43. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.; Bolívar, M.P.R. Governing the smart city: a review of the literature on smart urban governance. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2015, 82, 392–408. [CrossRef]

- O’brien, E.; Kassirer, S. People Are Slow to Adapt to the Warm Glow of Giving. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 30, 193–204. [CrossRef]

- Okulicz-Kozaryn, A.; Mazelis, J.M. Urbanism and happiness: A test of Wirth’s theory of urban life. Urban Stud. 2016, 55, 349–364. [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Guo, J. Development of smart city community service integrated management platform. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Networks 2019, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, B. Residential satisfaction in traditional and redeveloped inner city neighborhood: A tale of two neighborhoods in Beijing. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 23–36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, F.; Xue, B.; Wang, D.; Liu, B. Unpacking resilience of project organizations: A capability-based conceptualization and measurement of project resilience. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 41. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, D.; Jiang, Y. The impacts of relationships between critical barriers on sustainable old residential neighborhood renewal in China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Huang, Z.; Wong, S.W.; Liao, S.; Lou, Y. A holistic evaluation of smart city performance in the context of China. 2018, 200, 667–679. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. and P.D. Lund, Peer-to-peer energy sharing and trading of renewable energy in smart communities─ trading pricing models, decision-making and agent-based collaboration. Renewable Energy, 2023. 207: p. 177-193. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, N.; Bhushan, B. Demystifying the Role of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in Smart City Applications: Background, Motivation, Recent Advances, and Future Research Directions. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 130, 857–908. [CrossRef]

- Vanolo, A. Smartmentality: The Smart City as Disciplinary Strategy. Urban Stud. 2013, 51, 883–898. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Yu, H.; Xue, Y. Study on Carbon Emissions from the Renovation of Old Residential Areas in Cold Regions of China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3018. [CrossRef]

- Huda, N.U.; Ahmed, I.; Adnan, M.; Ali, M.; Naeem, F. Experts and intelligent systems for smart homes’ Transformation to Sustainable Smart Cities: A comprehensive review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 238. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W.; Chervany, N.L. Information Technology Adoption Across Time: A Cross-Sectional Comparison of Pre-Adoption and Post-Adoption Beliefs. MIS Q. 1999, 23, 183. [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Troisi, O.; Grimaldi, M.; Leone, D. Multi-level governance for sustainable innovation in smart communities: an ecosystems approach. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1167–1195. [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Mellander, C.; Rentfrow, P.J. The Happiness of Cities. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 613–627. [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. The Role of Smart City Characteristics in the Plans of Fifteen Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 3–28. [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Competitiveness, distinctiveness and singularity in urban design: A systematic review and framework for smart cities. 2021, 68, 102782. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Chaudhary, R.; Aujla, G.S.; Kumar, N.; Choo, K.-K.R.; Zomaya, A.Y. Blockchain for smart communities: Applications, challenges and opportunities. 2019, 144, 13–48. [CrossRef]

- Alshamaila, Y.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alsawalqah, H.; Aljarah, I. Effective use of smart cities in crisis cases: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 85. [CrossRef]

- Legris, P.; Ingham, J.; Collerette, P. Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 191–204. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Kido, A.; Wang, S. Evaluation Index Development for Intelligent Transportation System in Smart Community Based on Big Data. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2014, 7. [CrossRef]

- Luperto, M.; Monroy, J.; Renoux, J.; Lunardini, F.; Basilico, N.; Bulgheroni, M.; Cangelosi, A.; Cesari, M.; Cid, M.; Ianes, A.; et al. Integrating Social Assistive Robots, IoT, Virtual Communities and Smart Objects to Assist at-Home Independently Living Elders: the MoveCare Project. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 15, 517–545. [CrossRef]

- Lye, G.X.; Cheng, W.K.; Tan, T.B.; Hung, C.W.; Chen, Y.-L. Creating Personalized Recommendations in a Smart Community by Performing User Trajectory Analysis through Social Internet of Things Deployment. Sensors 2020, 20, 2098. [CrossRef]

- Mital, M.; Pani, A.K.; Damodaran, S.; Ramesh, R. Cloud based management and control system for smart communities: A practical case study. Comput. Ind. 2015, 74, 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, P.; De Marco, A.; Cagliano, A.C.; Mangano, G.; Scorrano, F. Current trends in Smart City initiatives: Some stylised facts. Cities 2014, 38, 25–36. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; Cui, C.; Xia, B. Influence of Outdoor Living Environment on Elders’ Quality of Life in Old Residential Communities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6638. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.E.; Melchior, A. Assessing telecommunications technology as a tool for urban community building. J. Urban Technol. 1995, 3, 29–44. [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities 2014, 41, S3–S11. [CrossRef]

- Beck, D.; Ferasso, M.; Storopoli, J.; Vigoda-Gadot, E. Achieving the sustainable development goals through stakeholder value creation: Building up smart sustainable cities and communities. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 399. [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Chen, J.-H.; Wei, H.-H.; Su, Y.-C. Towards people-centric smart city development: Investigating the citizens’ preferences and perceptions about smart-city services in Taiwan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102691. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.N. and M.J. Kim, A Critical Review of Smart Residential Environments for Older Adults With a Focus on Pleasurable Experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 2020. 10.

- Macke, J.; Sarate, J.A.R.; Moschen, S.d.A. Smart sustainable cities evaluation and sense of community. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, D.; Javaid, N.; Ahmed, I.; Alrajeh, N.; Niaz, I.A.; Khan, Z.A. Multi-agent-based sharing power economy for a smart community. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 2074–2090. [CrossRef]

- Stübinger, J.; Schneider, L. Understanding Smart City—A Data-Driven Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8460. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., et al., User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS quarterly, 2003: p. 425-478.

- He, Q.; Dong, S.; Rose, T.; Li, H.; Yin, Q.; Cao, D. Systematic impact of institutional pressures on safety climate in the construction industry. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 93, 230–239. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, S.; Song, M.; Fan, W.; Yang, S. Smart community evaluation for sustainable development using a combined analytical framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 158–168. [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Sakakibara, R.V.; Clark, V.L.P.; Luborsky, M.; Murray, S.M.; Castro, F.G.; Creswell, J.W.; Deutsch, C.; Gallo, J.J. Mixed methods grant applications in the health sciences: An analysis of reviewer comments. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0225308. [CrossRef]

- O'Leary-Kelly, S.W.; Vokurka, R.J. The empirical assessment of construct validity. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 387–405. [CrossRef]

- Arthur Jr, W., D.J. Woehr, and R. Maldegen, Convergent and discriminant validity of assessment center dimensions: A conceptual and empirical reexamination of the assessment center construct-related validity paradox. Journal of Management, 2000. 26(4): p. 813-835. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis.. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Madan, K. and R. Yadav, Understanding and predicting antecedents of mobile shopping adoption: A developing country perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2018. 30(1): p. 139-162. [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Vahidov, R.; Kersten, G.E. Acceptance of technological agency: Beyond the perception of utilitarian value. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103503. [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A.G.; Callegari, A.; Lopez, M.V. European Framework for the Diffusion of Biogas Uses: Emerging Technologies, Acceptance, Incentive Strategies, and Institutional-Regulatory Support. Sustainability 2016, 8, 298. [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Papadopoulou, C.-A.; Panagiotopoulou, M. Tools and Technologies for Planning the Development of Smart Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 43–62. [CrossRef]

- Zavratnik, V.; Podjed, D.; Trilar, J.; Hlebec, N.; Kos, A.; Duh, E.S. Sustainable and Community-Centred Development of Smart Cities and Villages. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3961. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).