Keywords PEFC; SFM; forest certification; economy; governance

1. Introduction

Forests are an important component of ecosystems and natural landscapes. It provides crucial ecosystem services and valuable products to the nation and community. Forests have benefited humans by providing resources such as timber for housing and construction, fuel for heating, food, and medicine. At the same time, they also play important roles as carbon sinks, watersheds for clean water, soil protection and function, as well as providing habitat for flora and fauna. Over the past few decades, the world’s forests experienced huge pressure from the demand for timber, rapid economic growth, and urbanization processes, which led to increasing deforestation. From 1980 until 1990, natural forest faced an average net loss of 9.9 million hectares annually [

1]. For a developing country, the figure is much higher, with a loss of 13.6 million hectares annually.

Latest statistics from the Global Forest Resource Assessment 2020 Report showed that forest areas continue to decline but at a slower rate for the period of 2000 to 2010, registering a net loss of 5.17 million hectares annually [

2]. Consequently, for the period of 2010 to 2020, a total annual net loss was recorded at 4.74 million hectares. Even though the rate of decline of net loss slowed over the past two decades, the continued trend in the reduction of forest areas, particularly in tropical regions, has attracted global concerns to address the crisis.

In response to this issue, in 1985 the World Bank, FAO, World Resources Institute (WRI), and United Nations Development Program (UNDP) launched the Tropical Forestry Action Plan (TFAP), which was later named the Tropical Forestry Action Programme [

3,

4]. Because the program was not very encouraging, in 1992 The Earth Summit, also known as the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The conference was recognized as a watershed event, and it made a number of significant decisions. The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Non-Legally Binding Authoritative Statement of Principles for A Global Consensus on the Management, Conservation, and Sustainable Management of All Types of Forests, also known as Forest Principles, and Agenda 21 were all adopted at the Summit [

5]. The importance of maintaining the various roles and functions of all types of forests was emphasized in the Forest Principles and Chapter 11 of Agenda 21: Combating Deforestation. These documents also highlighted the need to improve the protection, sustainable management, and conservation of all types of forests. They also encouraged the effective utilization and thorough evaluation of forest goods and services, as well as the systematic monitoring of forests and related forest issues.

Forest issues have continued to dominate and draw attention globally in numerous international policy and political agendas after the Earth Summit. The UN Commission on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) was established to track developments and pinpoint issues with the implementation of Agenda 21. It was recognized in the field of forestry that ongoing discussion and debate were necessary to strengthen political commitment through an intergovernmental forum to handle new forest concerns. The Intergovernmental Panel on Forests (IPF) was subsequently created under the auspices of UNCSD during the Third Session in 1995 in New York. The goal of the IPF was to generate coordinated recommendations and work toward consensus for the management, protection, and sustainable development of all types of forests. To carry out the objectives of the IPF, an Intergovernmental Forum on Forests (IFF) was established in 1997. Its mission is to maintain the intergovernmental policy debate on forests and to support and facilitate the implementation of the suggestions of action.

In order to offer a venue for ongoing policy creation and conversation among states that would incorporate international organizations and other interested parties, as stated in Agenda 21, UNCSD founded the United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF) in 2000. UNFF serves as a forum for ongoing policy development and dialogue among governments that would involve international organizations and other interested parties, as identified in Agenda 21. One of the responsibilities is to follow through on the 270 diverse IPF/IFF Proposals for Action, which include developing criteria and indicators for forests. The first UN Forest Instrument was adopted in 2007, and the Global Forest Financing Facilitation Network was established in 2015. Since its founding, UNFF has produced a number of noteworthy results. The first UN Strategic Plan for Forests 2017–2030 was recently adopted. A world where forests are sustainably maintained, contribute to sustainable development, and provide economic, social, environmental, and cultural benefits for both current and future generations is envisioned in the Strategic Plan for Forests’ vision statement.

The idea of forest sustainability is not new because it has long served as the foundation for forest planning and management in many nations. The idea has been applied for many years to maintain a steady supply of goods and services. The production of timber equal to the annual growth of a forest was the foundation of early efforts to sustainability. Simply said, it indicates that depending on the annual increment, the volume and amount of timber collected is determined. Since then, various interpretations of Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) have been translated from academia and international institutions. This sustainable forest also uses the three main pillars of sustainable development, which are economic, social, and environmental, as the core of forest management. By considering these three cores, Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) is developed considering the products and services produced from forests. Therefore, SFM can be interpreted as “the process of managing permanent forest land to achieve one or more management objectives related to the production of forest products and desired services without reducing the natural value that affects the social and physical environment” [

6].

Many researchers and academics have viewed forest certification as a novel form of governance. Forest certification was created as a market-driven, voluntary approach. Forest certification is referred to as a new institution by Cashore et al. [

7] as “Non-State Market-Driven” governance systems because companies along the market’s supply chain, rather than a state-centered authority, determine whether to abide by the rules and procedures of these private governance systems. This has drawn numerous academics and researchers who are interested in examining the theoretical underpinnings as well as a wide range of causes and reasons. According to a number of scholars [

8,

9,

10,

11], certification may have positive effects on forest management, economics, social issues, and the environment. Benefits of forest management include better performance standards, improved resource control, and improved forest management systems. Market access improvements, as well as improvements to company reputation and corporate ethics, are anticipated economic benefits. For example, balancing the goals of forest owners, reducing poverty, enhancing labor rights and living conditions, and encouraging community involvement are all examples of social benefits. Among other things, the environmental advantages include forest identification with high conservation value, biodiversity preservation and promotion, and environmental conservation.

The certification program’s emphasis on monitoring, auditing, and improving forest practices, along with the stand-level economic, ecological, and social benefits, can make it a potent tool for bringing about change in forest management practices. Many nations have taken the effort to create national forest certification programs that are referenced and recognized by international programs like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes (PEFC). The FSC scheme, which focuses on environmental, social, and economic viability components, was established in 1993 by environmental and social non-governmental organizations like Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth (FOE), and the World-Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). The FSC promotes the environmentally friendly production of wood and non-timber forest products while preserving the biodiversity, productivity, and ecological processes of the forest without compromising the respect for the rights of the workers and the communities that rely on the forests for their livelihoods. The FSC has created a set of Principles and Criteria that define responsible forest management at the international level and apply to all types of forests: temperate, tropical, and boreal; natural forests and plantations. Meanwhile, the PEFC scheme (initially named the Pan-European Forest Certification Scheme) was established as a response to the implementation of the FSC, where the FSC process did not address the needs of the small private forest owners and was dominated by NGOs. PEFC was set up as an umbrella organization to assess independent national forestry management standards against internationally recognized criteria and provide a framework for the mutual recognition of regional or national certification schemes for sustainable forest management.

The worldwide demand for forest certification among landowners and the public shows an increasing trend in recent years, and there is a concern that forest consumers might assume that all certification standards are equivalent. Clark et al. [

12] stated that there is a lack of mechanism to allow consumers to decide which certification program label has relevance to the most sustainably managed forests. Due to that, academic institutions from Europe have an interest in comparing the strengths and weaknesses of certification programs such as Basso et al. [

13] focusing on the process of the FSC program in North and South America. The study finds out that the establishment of certification was not similar among the American countries. Laclau et al. [

14] study the challenges in implementing national standards for sustainable forest management in Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile; meanwhile, Bhattarai et al. [

15] focus on the challenges faced by Nepal in FSC certification. Recent study done by Garzon [

6] focusing on comparative analysis of five certification programs.

The literature analysis findings show that most of the recent studies comparing the different forest certification programs at the national and international levels are focusing on North America and southern European countries. Not many studies were conducted to compare and analyze the certification standard application between Southeast Asian and European countries. With the acceptance level of certification found to be varied, especially among the developed and developing countries, as the requirements are based on the country needs. Therefore, these differences give an implication that cause the acceptance of certification to be interrupted or receive a good response from the timber industry. In connection with that, this study was conducted by comparing two countries that use their respective forest certification programs. The main question of the study is to determine whether there is a difference in the application and level of acceptance of forest certification between developed and developing countries; hence, to provide an answer to this question, this study outlines two objectives. The first objective is to determine the difference in governance, focusing on the similarities and differences of principles and criteria of sustainable forest management used in Malaysia and Sweden. The second objective is to analyze the impacts of forest certification on economics and governance within Asia Pacific and Europe. The study findings will help to improve the governance of the certification program, especially for Malaysia.

2. Methods

For the first objective, the research utilized document analysis to identify and describe the differences in characteristics of principals among forest certification programs in Sweden and Malaysia, which adopted the PEFC certification standard. Meanwhile, for the second objective, the analysis for the literature review is based on an extensive body of reports, books, and journal articles selected from diverse academic scholars and researchers around the globe. Numerous studies have attempted to analyze the contribution of forest certification, reasons and barriers for the adoption of forest certification and chain of custody, premium price and market access, cost of certification, consumers and industries perceptions of certified and non-certified wood products, forest owners’ perceptions and motivation for certification on forest management, smallholder certified communities, and consumer willingness to pay for certified wood products. This literature review aims to highlight the issues of forest certification, specifically the experience gained and the impacts of forest certification. The literature review report focuses on two geographical regions, specifically the Asia Pacific and Europe. The two thematic areas selected were economic and governance, as these themes provide information on the process and benefits of forest certification in the context of SFM.

3. Criteria, indicator and certification standards

The main objective of the formulation of criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management is to measure progress and improvement of management practices in the field. While certification is a process to ascertain the level of achievement based on sets of standards for sustainable forest management. The auditing process is undertaken in a given forest area or at the Forest Management Unit level and at a given time. Therefore, the differences between criteria and indicators for SFM and forest certification are unique because C&I for SFM are usually developed at the national level, which are descriptive in nature, mainly used for reporting and information for policymakers and governments. Meanwhile, forest certification focuses on forest management unit level, prescriptive in nature with standards and used for establishing the degree of progress in the implementation of sustainable forest management [

17]. In this regard, C&I for SFM is a reference basis for the development of forest certification standards.

The certification in Malaysia is under the purview of the Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC); they adopted the Malaysian Criteria and Indicator (MC&I) as the baseline for the certification program. This program consists of 9 principles and 49 criteria under The Malaysian Criteria and Indicator (MC&I) for Sustainable Forest Management (SFM), or, in short, MC&I SFM. Meanwhile, Sweden, as a member of PEFC, has adopted the Pan-European criteria and indicators as a basis for creating its forestry standard. This standard consists of two chapters, twenty-five objectives, and one hundred and thirty-three fundamental guidelines. Towards understanding the application of certification programs for these two countries, the main document of each certification program was reviewed. Mapping analysis was conducted to determine whether there is similarity or difference of subjects by comparing other certification programs principles.

Table 1 shows the structure of the forestry standard of certified programs. For MTCC, the description of certification programs is divided into principles, criteria, indicators, and verifiers [

18]. Meanwhile, for PEFC Sweden, the terms used in explaining the standards are chapter, objective, fundamental guidelines, and requirement [

19,

20]. The difference of term used for these two certification programs is shown in

Table 2 below.

4. Results and Discussion

As a tropical country, Malaysia has a total area of 33 million hectares, and it consists of three regions, namely Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah, and Sarawak. The total forested area in Malaysia is approximately 54% of its total land area, with peninsular Malaysia around 5.73 million hectares, Sabah 4.68 million hectares, and Sarawak 7.72 million hectares [

21]. Forests in Malaysia are classified by their roles and functions, as stated by the Forestry Department of Peninsular Malaysia, the Sabah Forestry Department, and the Sarawak Forestry Department. The categorization of forests primarily includes permanent reserves forests, protection forests, and productivity forests. Forest management in Malaysia is separated into three regions: Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah, and Sarawak. Each of these regions in Malaysia has its own distinct administrative structure, regulations, and legislation for managing its own forest areas. Peninsular Malaysia is divided into two levels, namely Federal and State. The Forest Department of Peninsular Malaysia (FDPM) and the State Forestry Department are responsible for managing the forests in Peninsular Malaysia. This is regulated by the National Forest Act 1984 (amended 1993) and the National Forestry Policy 1978 (revised 1992) and subsequently, the Forestry Policy of Peninsular Malaysia (FPPM). The FDPM is entrusted with an essential role at the federal level in creating policies and procedures connected to regulations, as well as providing advice and technical services to the states. Meanwhile, forest management and administration at the state level are under the jurisdictions of the State Forests Enactment, State Forests Rules, Wood-Based Industrial Enactment, and Wood-Based Industrial Rules. For Sabah, forests are managed by the Sabah Forestry Department, and they are regulated under the Sabah Forest Enactment 1968, Forest Rules 1969, Forest (Timber) Enactment 2015, and Sabah Forest Policy. Whereas for Sarawak, it is led by the Forest Department Sarawak (FDS) and adopted the Forests Ordinance 2015 (Cap.71), Forests Regulations, and Sarawak Forest Policy (2019).

Sweden is one of the developed nations, and their economy is focused on exports, such as iron ore, hydropower, and timber products. An estimated two-thirds of the 40.7 million hectares that make up Sweden are covered in coniferous forest. Sweden’s forests have a very homogeneous species with Scots Pine accounting for 37%, Norway Spruce for 46%, and other deciduous species making up about 15%. In the last century, woods in Sweden have undergone a process of regeneration after being subjected to logging for cattle, building, and shipping purposes. Forests are extensively cleared to provide charcoal and poles for mining operations. Forest restoration initiatives were initiated in the twentieth century, coinciding with the implementation of the Forestry Act in 1903. The current yearly growth rate of forests is predicted to be 122 million cubic meters [

19]. Approximately 28 million hectares, which is equivalent to 70% of Sweden’s total land area, is forested. Forest ownership in Sweden is comprised of private people, private enterprises, government entities, and other private owners. Approximately 48% of productive woods are owned by private enterprises, including physical assets, farms, and single proprietorships. The private owners held around 220,000 management units that are owned by 300,000 individuals, with women accounting for 38% of the ownership. According to the Swedish EPA [

22], private firms own 24% of the forest area, state-owned enterprises own 12%, state forests account for 8%, forests owned by other private entities such as churches and charities account for 6%, and other public ownership accounts for 1% of productive forests. The Swedish Forest Agency is the regulatory body responsible for ensuring that individual or corporate forest owners adhere to the rules outlined in the forestry act. The Swedish forestry act was approved by legislators in 1993 [

23], and subsequent modifications and additions to this policy have consistently had majority approval from both the government and members of parliament. Two laws were introduced: the “Forestry policy in line with the times” bill in 2008 and the newest bill in 2022, which focuses on strengthening property rights, implementing flexible protection measures, and enhancing incentives for nature conservation in forests [

23].

In addition to overseeing the implementation of the Forestry Act, the Forest Agency is also tasked with ensuring adherence to environmental regulations. The objective is to guarantee progress towards sustainable development as outlined in Agenda 2030. The Swedish government has established 16 environmental quality objectives and a number of significant targets to ensure compliance with the environmental code [

22]. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, commonly referred to as the Swedish EPA, is the governing body tasked with overseeing and evaluating these environmental goals. Sweden also employs other compliance acts and codes to ensure forest sustainability. One such example is The Land Code (1970:994), which is overseen by the Land Registration Division under the Ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure, and The Reindeer Husbandry Act and The Heritage Conservation Act [

11]. In the context of the certification program under PEFC for both countries, the forestry standards set by them are based on their forest structure, policy, and governance.

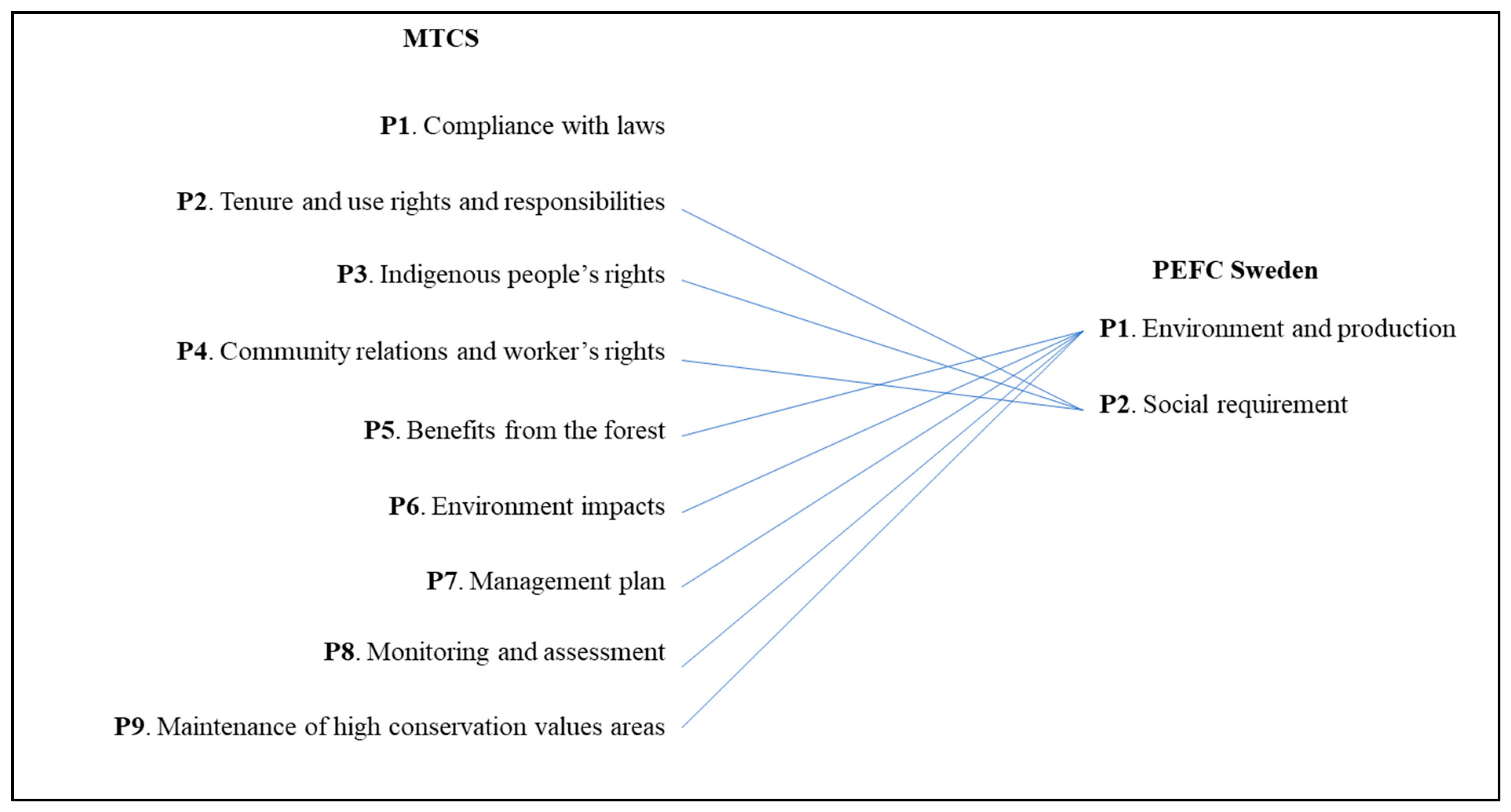

Figure 1 below illustrated the consistency for both principles under the PEFC Sweden and MTCS forestry standards.

Table 3 show a breakdown of PEFC Sweden criteria for further understanding.

Figure 1 shows that the MTCS program used the Malaysian Criterion and Indicator for Sustainable Forest Management (MC&I) as a basis for the forestry certification standard. Meanwhile, for PEFC Sweden, the criteria, indicators, and operative guidelines from the Libson resolution (1998) L1 and L2, Swedish forestry legislation, and other applicable legislation were applied as a platform for the standard. To further understand the consistency,

Table 3 shows a PEFC Sweden forestry standard criteria. It is important to understand that the consistency of both forestry standards is not just at the principle level but might also occur at the criteria level depending on the style of documentation for both programs. From nine principles under the MTCS program, eight principles appear in the PEFC Sweden forestry standard. P2, P3, and P4 under MTCS appeared in P2 for PEFC Sweden. While P5, P6, P7, P8, and P9 under MTCS are appearing in P2 for PEFC Sweden. To elaborate on the consistency of each standard, the MTCS Malaysian Criterion and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management (MC&I) was used as a comparison with the PEFC Sweden forestry standard. Thus, the findings of the analysis for the nine principles were discussed accordingly as follows:

4.1. Principle 1: Compliance with laws

The forestry standard under the MTCS program contains more indicators for regulatory compliance and is more detailed in the description. Law, act, and regulation were outlined for each criterion under the verifier. Meanwhile, for PEFC Sweden, the list of laws or regulations that are related to the standard is explained in simpler form, and information on current legislation can be obtained from the web-based services [

19]. Under the MTCS program, the law and regulation related to the forest are clearly listed in the standard, and it gives a deep insight to understand more on the regulatory framework. Since Malaysia is divided into three regions named Peninsular, Sabah, and Sarawak, it’s crucial to elaborate on how the regulatory framework in each region is different because the regulation and governance in each region are different. Meanwhile, for Sweden, they have centralized information, and it is convenient to refer to web-based services that are provided by related forest agencies.

4.2. Principle 2: Tenure and use rights and responsibilities; Principle 3: Indigenous people’s rights; Principle 4: Community relations and worker’s rights.

In terms of social aspects, the standard under the MTCS program is elaborated into three areas, which are P2, P3, and P4. P2 explained criteria for long-term tenure and use rights to the land and forest resources. For P3, the focus is on legal and customary rights of indigenous people. This principle acknowledges the indigenous peoples right to own, use, and manage their land, territories, and resources. Meanwhile, P4 is focusing on community and workers’ rights, where the forest management operations must maintain and enhance the long-term social and economic well-being of local communities and forest workers. Under the PEFC Sweden forestry standard, the explanation about the social aspect is elaborate in P2: Social requirements. This principle focuses on forest ownership, workers well-being, social and community economic enhancement, relationships among stakeholders, and rights of public access in forests. In terms of community and workers aspects, MTCS and PEFC Sweden forestry standards show a similarity in terms of well-being and economics, and both standards also emphasize providing job opportunities, as well as the health of the working environment. Another aspect of social values is a public relationship; PEFC Sweden is more specific by explaining the role of forest owners in ensuring the rights for public access for recreation and outdoor life; meanwhile, MTCS didn’t have an aspect on public access. The forest governance in Sweden is different from Malaysia, where people have the right to access forests for recreational use and outdoor activities. Meanwhile in Malaysia, there are rules and requirements that were set to limit the public from entering the forest, especially the Forest Management Unit (FMU) area.

4.3. Principle 5: Benefits from forest; Principle 6: Environment impacts; Principle 7: Management plan; Principle 8: Monitoring and assessment; Principle 9: Maintenance of high conservation values areas.

The MTCS program notes that the forestry planning should include environmental aspects. Under this program, there are five principles that emphasize the importance of the environment, which are P5, P6, P7, and P8. The standard covers from forest planning until ensuring the sustainability of the natural forest as well as forest plantation. On top of that, forest owners were giving a mandate to monitor and assess the forest within the FMU and the FMU itself in terms of forest products, chain of custody, management activities, and social and environmental impacts. Thus, it gives the forest manager a clear picture of what they should comply with under this standard. The structure of these 5 principles mentioned above shows a similarity with PEFC Sweden. Under PEFC Sweden, they combine all these 5 principles into 1 principle, which is P2: Environment and production. The explanation in this principle is not as detailed as the MTCS program, but it is understandable for the first-time reader. Even though there are some similarities, both programs have focus areas that are based on country adaptation. For productive forests, PEFC Sweden clearly stated that all productive forest land that is more than 20 acres must set aside at least 5% for environmental consideration under their forest management plan. This set-aside means forest owners are responsible for creating conditions that tie with habitats that require protection and areas that were given priority in areas with high conservation value, areas with high conservation values or areas of great significance for recreation and outdoor life, and areas with developable conservation values, other social values, or cultural heritage sites [

19]. Meanwhile, for MTCS, the forest management activities that are in high conservation value areas shall maintain or enhance the area. The forest managers need to conduct an assessment to identify if the FMU area has a criterion to be considered as high conservation value in accordance with relevant guidelines and consultation with relevant stakeholders and experts.

5. Element of Economy and Governance Impact of Forest Certification

To look into the impact of forest certification for both region, document analysis from several study is collected and compile together in order to get the full spectrum of forest certification.

5.1. Europe

FSC and PEFC are the most prevalent certification schemes in Europe. Many companies in Europe choose to be certified under both schemes for the suitability and higher potential to trade certified timber products with reference to the demand of the buyer and market trends. As of 2014, the total number of European countries that implemented forest certifications is 32 countries [

24]. The application and achievement of forest certifications are at different levels, where the lowest is recorded at 3.13% and the highest at 95.3%. There are countries that applied only one certification program; however, most European countries applied both certification programs. The total areas of forest in Europe certified based on programs are 70,416,019 hectares certified by FSC and 85,784,952 hectares by PEFC [

24]. The forest certification implementation process in Europe has significant implications for the industry, the country, local communities, and consumers.

a. Economic

In terms of economic benefit, several scholars indicate that through Chain of Custody certification, positive changes have been recorded to the certified companies. In Romania, the number of Chain of Custody (CoC) certified companies has rapidly increased, and the adoption of FSC CoC certification had an impact on obtaining new customers and improving Romanian forestry companies’ image and reputation [

25]. Similar benefits are received by the Croatian FSC holders, where FSC helps them to keep existing customers and obtain new customers and also facilitates increasing competitiveness, exports, and the company’s image [

26]. Meanwhile, in the Finnish wood products industry, through CoC certification, the industries received acceptance from environmentally sensitive consumers and were able to satisfy existing customers and, at the same time, create a good public reputation [

27].

In their study on the expansion of FSC certification among Italian forest-based industry, Galati et al. [

28] show that most companies are mainly driven to adopt certification for better recognition by customers, as it creates a positive corporate image related to its commitment in the protection and responsible use of resources. Furthermore, demand by consumers and the aim to increase market competitiveness are also key reasons that guide companies to adopt FSC certification. A similar result was obtained by Klarić et al. [

26], where Croatian wood industry companies implemented FSC CoC certification due to demand by consumers and to stay competitive and survive in the market. Other reasons for certification adoption in Europe are increases in sales and new market penetration [

29], pressure by the public and media [

30], and also maintaining market access and gaining international recognition [

25]. In Finland, strong demand for certified products from the United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Germany has driven Finnish companies to adopt CoC certification, and the adoption of CoC certification is mainly limited to suppliers of primary wood products [

27].

An assessment of CoC in the Czech and Slovak Republic found that the key problems in the certified supply chain faced among certified companies are the sufficient quantity of certified material inputs and the overpriced certified materials [

29]. The overpriced certified materials are more problematic for companies that hold double certification schemes (PEFC and FSC) and FSC-certified companies compared to the PEFC-certified companies. This is due to the better availability of PEFC-certified raw material and the shortage of domestic FSC wood. A similar problem was also reported in [

31], where companies that sell in foreign markets encountered a shortage of certified timber markets. Operational costs also can be found as barriers and disinterest for Czech business entities in the certification systems [

30]. For the paper industry and construction industry in the United Kingdom, the lack of supply of certified paper and certified hardwood are the external market barriers to the uptake of certified materials [

32].

In terms of premium price, Palus et al. [

29] pointed out that 51% of respondents do not pay more for certified products, and only 43% of respondents pay more in the range from 1% to 10% of premium price, especially primary and secondary wood processing companies. This study highlighted that 93% of respondents do not receive any green premium sale of their certified products due to the value of the premium price that is not able to cover the costs of CoC certification and therefore does not increase profitability and enhance business performance in the short term. Similar findings from Owari et al. [

26] also found that wood products companies in Finland expressed that it is impossible to charge a premium price for certified products and no longer expect to gain a premium price. Likewise, Romanian forestry companies also do not consider premium price as an important benefit [

25,

31].

A study on the willingness to pay of secondary wood manufacturers in Italy shows that the majority of respondents are willing to pay a higher premium price for local wood materials compared to certified wood products [

33]. This study shows that 20.7% of respondents would be willing to pay a mean premium price of 4.13% for local wooden panels and 23.1% of them would be willing to pay a mean premium price of 2.95% for local wooden planks. Main reasons for them to pay a premium price for local products are to promote the local wood market, to support the environmental protection of local forests, and the high quality of local wood materials. As for certified wood products, 19.0% of respondents are willing to pay a mean premium price of 2.68% for certified wooden panels and 29.7% of them are willing to pay a mean premium price of 2.40% for certified wooden planks.

On the contrary, in terms of economic changes after FSC certification, Halalisan et al. [

34] found that revenues did not increase after certification, and sold certified wood did not have a higher price than the uncertified wood. Halalisan et al. [

34] also highlighted that there was no significant impact on profits as the revenues remain unchanged after the adoption of FSC CoC certification, where most companies in Romania adopted different types of certification other than FSC, such as ISO 9001 and ISO 140001, in order to maintain the export markets and to meet customer requirements. Furthermore, the costs of certification were frequently mentioned to be the negative aspect of the certifications among Czech business entities that did not have the relevant series of the ISO management system or another system that would simplify the process of CoC certification [

30].

b. Governance

A case study in Russia by Sundstrom and Henry [

35] uncovered the impact of FSC standards that have influenced state policy, domestic forest governance, laws, and enforcement practices. The introduction of FSC at first in Russia has been conflicted as the state forest regulators rejected the idea of a private certification. However, the need to meet FSC standards has led to greater changes in Russia. Sundstrom and Henry [

35] discovered that FSC has indirectly influenced the Russian state forest governance where new policies have been revised, competitive domestic certification schemes have been created, and new enforcement practices have been implemented to accommodate certification. The impact of FSC in the Russian were facilitated by few conditions that include poor quality and decentralized governance, contradictions among overlapping standards, and foreign market demand.

The challenges of institutional development in the implementation and roles of forest certification in Russia as an element of the multi-level governance system show that the Russian forestry actors and stakeholders are willing to become more involved in sustainable forest management [

36]. Clearly, forest certification has expanded the stakeholders’ roles, particularly NGOs and local communities, in forest management. Furthermore, forest certification as a multi-level governance institution has created a new mechanism in Russia for linking and coordinating between local and global standards. The authors highlighted that the success and failure of forest certification as a multi-level governance mechanism is also disproportionately dependent on ground-level players such as logging operators in the forest, local bureaucrats, audit inspectors, and communities living near the forest. Nevertheless, the value and attitude of local stakeholders also can be the determining factors for the outcomes of certification efforts.

Forest certification is voluntary and can be regarded as a new governing mechanism. Hysing [

37] highlighted that forest certification can be governed through private governance without the intervention and authority from the government. In the case of forest certification in Sweden, the Swedish forest certification scheme can be depicted as private governance where non-governmental actors are involved as a capacity to govern based on voluntary self-regulation rather than the sovereign authority of the government. This situation created a high degree of discretion for the participating non-governmental actors to design and implement forest certification in Sweden. However, to some extent, forest certification has enabled the government to indirectly involve the private governing arrangements through facilitation and support, shaping public procurement policies, and providing legitimacy. With continuous interaction between governmental actors, forest certification schemes have reinforced the capability and effectiveness of public policy instruments and moulded their environment in line with government objectives.

5.2. Asia Pacific

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) schemes are increasingly used in the Asia Pacific countries, and many countries have developed their own national forest certification schemes, such as the Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC) in Malaysia, the Indonesian Ecolabelling Institute and Indonesian Forestry Certification Cooperation (IFCC) in Indonesia, the China Forest Certification Council (CFCC) in China, and the Japanese Sustainable Green Ecosystem Council (SGEC) in Japan. The experience and impacts of these certification schemes implemented by countries in the Asia Pacific were discussed within the context of the four main thematic areas.

a. Economic

Economically, the impact of forest certification can dramatically increase certified forest companies’ competitiveness as it aims at promoting economically viable forest management in certified enterprises. In Japan, Yusuhara Forest Owners’ Cooperative (YFOC) began to seek FSC forest certification in late 1998, and the economic changes took place slowly [

38]. With the continuous efforts of selling FSC-certified wood in the domestic housing construction market, YFOC has substantially increased their timber sales in recent years. The profitability of YFOC started to grow as they began to receive demand for certified sawn timber from builders who were building ecology-oriented houses. The builders perceived that FSC-certified timber was an environmentally sound material. Indirectly, the FSC certification system acts as a tool that rejuvenates small-scale forestry in Japan and also creates many opportunities to develop businesses using certified timber with similar business models like YFOC [

39].

Maraseni et al. [

40] highlight that with the increasing demand for certified timber from the market, smallholder growers of Acacia in Central Vietnam may not receive the same financial returns of total benefit compared to the sawmiller company. Even though most of the certification costs of growers are covered by WWF and SNV (Netherlands Development Organisation), the difference in returns is higher for sawmillers and still profitable even if the price of logs increases by 20% or the selling price of the product decreases by 10%. In China, Zhao et al. [

41] also found that the cost of certification was a major concern among landowners. The same study also mentioned that forest certification was not widely understood by the landowners in China, another major factor limiting participation.

However, Japanese forestry enterprises emphasised that FSC certification has not brought economic benefits through the sale of certified wood as they have to bear the cost of certification [

42]. Similar studies by Sugiura and Oki [

43] found that forestry enterprises did not receive the expected profits from certification despite a heavy outlay of cost and effort for their certifications. Therefore, it proves that the market for certified wood products has proven difficult to build for many other reasons, ranging from poor public relations to weak relations between producers and regional wood dealers, as well as the scarcity of such dealers [

42].

In terms of the premium market of certified wood products, comparative price analysis conducted by Kollert and Lagan [

44] highlighted that forest management certification can achieve a market premium for certified logs. In particular, high-quality hardwood logs, especially Selangan Batu and Keruing destined for the export market, fetch a premium price of 27% to 56%. Even the lower-quality log examples, Kapur and Seraya, also fetch a premium price; however, the difference is less pronounced, 2% to 30%. The high market demand and good prices for certified timber help to pursue sustainable forest management standards and have been a key driver for improvements in forest management in some forests of the tropics. Nonetheless, certified forest products rarely resulted in a premium price in Japan, as the Japanese market has little influence on the trade of certified wood products [

45]. Moreover, premiums may not provide enough profit to cover the cost of certification. Iwanaga et al. [

46] elucidate factors and tendencies among certified stakeholders in expanding forest certification in Quang Tri Province, Vietnam. In the study, two certified companies obtained a higher selling price of timber after obtaining FSC certification. However, the selling price of logs for wood chips remains steady at USD 60 per ton, as there is no wood chip company willing to buy for a premium price even with the FSC certification. Meanwhile, the income of the smallholders’ group certification increased due to the rise in timber prices on a long-term basis.

From the aspect of chain of custody (CoC) certification, Ratnasingam et al. [

47] in a study of Malaysian wooden furniture manufacturers’ readiness to embrace CoC certification highlight that the lack of premium price, limited market potential, and high cost were cited as the primary reasons deterring furniture manufacturers from adopting chain of custody certification. Furthermore, the benefits derived from the adoption of chain of custody certification by furniture manufacturers in Malaysia are not apparent. On the other hand, the lack of demand for certified furniture products within the domestic and international markets of Southeast Asia are the primary factors for the reduced number of companies that are or consider being chain of custody (CoC) certified. Furthermore, Shukri [

48] highlighted that Malaysians do not place a high importance on the environmental or ecological attributes of a product when making their purchases. This is due to the lack of effort in promoting and developing ecologically conscious products towards Malaysian consumers. Regardless of the lack of purchases among Malaysians of certified timber products, manufacturers in Malaysia who are export-oriented companies used certified wood materials to improve their image and reputation in the green wood products and also to meet customer demand, especially from the environmentally concerned consumers in the European market [

49].

The most recent study on the export performance by Saadun et al. [

50] shows that there is significant positive growth of the export volume of certified timber products under the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS) between 2003 and 2015 with an estimated average rate of 22%. Several factors may contribute to the positive trends, including the increasing demand for certified timber from the industrialised countries and also the endorsement of MTCS by the PEFC scheme, which is exposed to new market access, especially in East Asia.

b. Governance

The governance of the certification process in the Asia Pacific countries is mostly established and governed by the government agencies that are responsible for forest management and the timber industry. For example, the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS), which was designed with reference to PEFC guidelines and criteria and moulded to cater to the needs of local forest owners, managers, and the timber industry, as well as to furnish the requirements by global standards such as PEFC and global market standards. Malaysia’s forests are regarded as generally well managed. As of 2022, 5.35 million hectares of forests had acquired MTCS Forest Management Certification (FMC), and 384 timber companies had gained MTCS CoC (Chain of Custody) certification [

51]. Almost all the state-owned forest management units in Peninsular Malaysia are MTCC-certified, while the area of certified forests in Sabah and Sarawak is more limited.

Although top-down in nature, however, the practice also illustrates that there are also bottom-up approaches to practice, with the participation of local communities and non-governmental organizations. Their participation comes from many aspects. For example, an initiative by the Bornion Timber Sdn. Bhd. in Sabah, Malaysia, established a rubber plantation that covers an area of 25,000 hectares, which is located within their timber concession areas. This plantation helps the local community for economic opportunity, where it created an economical timber crop for sustainable forest development while producing a secondary product, latex, that plays a major role for local community benefit. They recruit local community members as rubber tappers and provide training for them to become professional rubber tappers. They also provide facilities such as quarters with electricity and gravity water, all safety measures such as fire extinguishers based on forest certification requirements, and sports facilities. In addition, the company established a Bornion Rainforest Research Area for conservation purposes that covers an area of 688 hectares. The management of this forest was done with support from the Sabah Wildlife Department, WWF, and other NGOs for training and joint operations of wildlife wardens, who were participated in by the local communities. The function of community forest and the provision of livelihood of the community must be preserved and maintained. The main activities in forest plantation, natural forest, and conservation can be utilized to empower local community benefits. The forest certification process created an opportunity for the industry and local community in the governance process and system, as this ensures sustainability for the forest ecosystem and its provision potential for the timber industry in the future.

6. Conclusion

Forest certification is currently an important tool as a policy instrument to ensure sustainable forest management implementation to achieve its objectives and targets. It is a voluntary market-based instrument with the emergence of non-state authority in governing the process. Furthermore, several authors have indicated that certification could bring a range of potential benefits in forest management, economics, and social and environmental impacts. However, despite many years of implementing forest certification, evaluating potential impact from the implementation process has generated mixed results and will continue to remain as a challenging task.

Results from this study show that both Malaysia and Sweden have some similarities and differences in each forest management standard. Malaysia is considered a megadiverse country that has more complex flora and fauna species; thus, its timber species are also diverse. On top of that, Malaysia was divided into three regions: Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah, and Sarawak, which consist of different sets of governance and regulation. Hence it led to challenges in setting up the standard for forest management. As a result, the certification standard developed by Malaysia is more complex and detailed by considering the regional governances, rules, and regulations. Meanwhile, in Sweden the standard for forest management is written down in simpler form and sufficient information, yet it also provides additional info or links for users to understand more about forests and regulation’s structure. This approach is seeming more practical and easier for first-time users to understand the standard and structure of forest management in Sweden. The similarities for both countries’ standards occur in each set of principles. The information of P2, P3, and P4 under the Malaysia forest management standard is also in the Sweden forest standard, but it was combined together in one principle under P2 (social requirement). Meanwhile, for P5, P6, P7, P8, and P9, the Malaysia standard is appeared in P1 (Environment and production) in the Sweden standard.

The current review on impact studies covering two geographical regions, specifically the Asia Pacific and Europe, indicated positive impacts on economic and governance aspects of forest certification. In terms of economic benefits, findings indicated that forest concessionaires, timber companies, and traders acknowledge that they were able to experience improved market access for their timber products. Consequently, it created better competitiveness and improved corporate image in the international timber markets. On the contrary, there were diverse results with respect to receiving premium prices for their timber products. Substantial changes in institutions have taken place to accommodate the requirements of forest certification. To improve the uptake of forest certification on a wider scale, it would be advisable that the consumer in developed countries pay a premium price for certified timber as a motivation for more companies and concession holders to have their forest certified. It must be realized that sustainable forest management is a process and requires time to achieve the desired goals. It involves complex ecological, economic, social, and environmental factors that determine the success of SFM in the long run. Furthermore, sound policy, strong legislation, adequate manpower, and efficient organisations are prerequisites for continuous improvement of sustainable forest management. Finally, strong and lasting political commitment, sufficient financial support, and investment in forest management are of utmost critical importance to ensure forest sustainability.

By having PEFC certification, both countries show commitment in developing their standards based on country needs and ultimately achieving sustainable production without damaging the environment. Even though there are differences in each approach, it suits the current situation. Political influences play major roles in ensuring the forest management in each country and following consumer awareness. Some of the findings were evident in this analysis, and yet more investigation is needed to seek into deeper linkages between national legislation and forest certification languages.

Author Contributions

Shah Badri Mohd Nor drafted manuscript, conceptualization, collected and analysed the data. Ahmad Fariz Mohamed approved the final manuscript, reviewed, edited the manuscript and provide guidance for the entire research study process. Shamsul Khamis reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- FAO. State of the World’s Forests 2001. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2001, 1-3. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y0900e/y0900e03.htm (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- FAO. (2020). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020, 1-6. Available online: https://www.fao.org/interactive/forest-resources-assessment/2020/en/ (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Douglas, J.; Simula, M. The future of the world’s forests: Ideas vs ideologies (Vol. 7). Springer Science & Business Media. 2010.

- Teplyakov, Victor.; Poore, Duncan. Changing Landscapes: The Development of the International Tropical Timber Organization and Its Influence on Tropical Forest Management. Environmental History - ENVIRON HIST. 2004, 9.

- LESTARI. The Impact of Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS) On Forest Management, Industry and Trade. Institute For Environment and Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Malaysia. 2023.

- International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO). ITTO Criteria for the Measurement of Sustainable Tropical Forest Management. ITTO Policy Development Series No. 3. 1992.

- Cashore, B.W.; Auld, G.; Newsom, D. Governing through Markets: Forest Certification and the Emergence of Non-State Authority. Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA. 2004.

- Bass, S.; Simula, M. Independent Certification/Verification of Forest Management. Background Paper. World Bank/WWF Alliance Workshop. 1999.

- Bass, S. ; Thornber.; Markopoulos M.; Roberts S.; Grieg-Gran M. Certification’s impacts on forests, stakeholders and supply chains International Institute for Environment and Development. 2001.

- C., E. Forest certification: a policy perspective; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Bogor, Jawa Barat, Indonesia, 2000; ISBN.

- Vogt, K.A.; Larson, B.C.; Gordon, J.; Vogt, D.J.; Fanzeres, A. Forest Certification Roots, Issues, Challenges, and Benefits. CRC Press. 2000, pp. 318-352.

- Clark, M.R.; Kozar, J.S. Comparing Sustainable Forest Management Certifications Standards: A Meta-analysis. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, V.; Jacovine, L.; Nardelli, A.; Alves, R.; Silva, E.; Silva, M.; Andrade, B. FSC forest management certification in the Americas. Int. For. Rev. 2018, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laclau, P.; Meza, A.; De Lima, J.G.S.; Linser, S. Criteria and Indicators for sustainable forest management: lessons learned in the Southern Cone. Int. For. Rev. 2019, 21, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, B.; Kunwar, R.; Kc, R. Forest certification and FSC standard initiatives in collaborative forest management system in Nepal. Int. For. Rev. 2019, 21, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez Garzon, A.R.; Bettinger, P.; Siry, J.; Abrams, J.; Cieszewski, C.; Boston, K.; Mei, B.; Zengin, H.; Yeşil, A. A Comparative Analysis of Five Forest Certification Programs. Forests 2020, 11, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rametsteiner, E.; Simula, M. Forest certification - An instrument to promote sustainable forest management? Journal of Environmental Management. 2003, 67, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC). (2021). Malaysian Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management. MTCS ST 1002:2021. Malaysian Timber Certification Council. 2021. Available online: https://mtcc.com.my/certification-standard/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Swedish PEFC Forestry Standard. PEFC SWE 002:5. PEFC Sweden. 2023. Available online: https://www.pefc.org/discover-pefc/our-pefc-members/national-members/pefc-sweden (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Swedish PEFC Forestry Standard. PEFC SWE 002:5. PEFC Sweden. 2022. Available online: https://www.pefc.org/discover-pefc/our-pefc-members/national-members/pefc-sweden (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Malaysia Policy on Forestry. 2022. Available online: https://www.nres.gov.my/ms-my/pustakamedia/Penerbitan/Malaysia%20Policy%20on%20Forestry%20(Ver%202.0).pdf (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Naturvardsverket. Swedish Environmental Objective. Swedish EPA. 2024.

- Certification System for Sustainable Forest Management. PEFC SWE 001:4. PEFC Sweden. 2017. Available online: https://cdn.pefc.org/pefc.se/media/2021-02/943d15e8-5404-406f-8ab1-6ad6250559f8/d94ba434-aa43-5c12-89fd-343b87fa008f.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Maesano, M.; Ottaviano, M.; Lidestav, G.; Lasserre, B.; Matteucci, G.; Mugnozza, G.S.; Marchetti, M. Forest certification map of Europe. iForest - Biogeosciences For. 2018, 11, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halalisan, A.; Popa, B.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Ioras, F.; Abrudan, I. Drivers, perceived benefits and impacts of FSC Chain of Custody Certification in a challenging sectoral context: the case of Romania. Int. For. Rev. 2019, 21, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarić, K.; Greger, K.; Klarić, M.; Andrić, T.; Hitka, M.; Kropivšek, J. An Exploratory Assessment of FSC Chain of Custody Certification Benefits in Croatian Wood Industry. Drv. Ind. 2016, 67, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owari, T.; Juslin, H.; Rummukainen, A.; Yoshimura, T. Strategies, functions and benefits of forest certification in wood products marketing: Perspectives of Finnish suppliers. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 9, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Gianguzzi, G.; Tinervia, S.; Crescimanno, M.; La Mela Veca, D.S. Motivations, adoption and impact of voluntary environmental certification in the Italian Forest based industry: The case of the FSC standard. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 83, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluš, H.; Parobek, J.; Dudík, R.; Šupín, M. Assessment of Chain-of-Custody Certification in the Czech and Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michal, J.; Březina, D.; Šafařík, D.; Kupčák, V.; Sujová, A.; Fialová, J. Analysis of Socioeconomic Impacts of the FSC and PEFC Certification Systems on Business Entities and Consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halalisan, A.; Marinchescu, M.; Popa, B.; Abrudan, I. Chain of Custody certification in Romania: profile and perceptions of FSC certified companies. Int. For. Rev. 2013, 15, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werndle, L.; Brown, N.; Packer, M. Barriers to certified timber and paper uptake in the construction and paper industries in the United Kingdom. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2005, 13, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Notaro, S. Secondary wood manufactures' willingness-to-pay for certified wood products in Italy. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 92, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halalisan, A.F.; Abrudan, I.V.; Popa, B. Forest Management Certification in Romania: Motivations and Perceptions. Forests 2018, 9, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, L.M.; Henry, L.A. Private Forest Governance, Public Policy Impacts: The Forest Stewardship Council in Russia and Brazil. Forests 2017, 8, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulybina, O.; Fennell, S. Forest certification in Russia: Challenges of institutional development. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 95, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysing, E. Governing without government? The private governance of forest certification in Sweden. Public Administration 2009, 87, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, I. Experiences of a Forest Owners’ Cooperative in using FSC forest certification as an environmental strategy. Small-scale For. 2006, 5, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, I. Ecology-oriented House Builders and FSC-certified Domestic Timber in Japan. Small-scale For. 2009, 9, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraseni, T.N.; Son, H.L.; Cockfield, G.; Duy, H.V.; Nghia, T.D. The financial benefits of forest certification: Case studies of acacia growers and a furniture company in Central Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xie, D.; Wang, D.; Deng, H. Current Status and Problems in Certification of Sustainable Forest Management in China. Environ. Manag. 2011, 48, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, K.; Yoshioka, T.; Inoue, K. Effects of acquiring FSC forest management certification for Japanese enterprises using SmartWood Audits. J. For. Res. 2012, 23, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, K.; Oki, Y. Reasons for Choosing Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Sustainable Green Ecosystem Council (SGEC) Schemes and the Effects of Certification Acquisition by Forestry Enterprises in Japan. Forests 2018, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollert W; Lagan P. Do certified tropical forest logs fetch a market premium? A comparative price analysis from Sabah, Malaysia. Forest Policy and Economics. 2007, 9, 862–868. [CrossRef]

- Owari, T.; Sawanobori, Y. Analysis of the certified forest products market in Japan. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2007, 65, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga, S.; Duong, D.T.; Ha, H.T.; Van Minh, N. The Tendency of Expanding Forest Certification in Vietnam: Case Analysis of Certification Holders in Quang Tri Province. Jpn. Agric. Res. Quarterly: JARQ 2019, 53, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingam, J.; Macpherson, T.; Ioras, F.; Abrudan, V. Chain of Custody certification among Malaysian wooden furniture manufacturers: status and challenges. Int. For. Rev. 2008, 10, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukri, M. Marketing certified wood products to Malaysian consumers: Exploring issues for the local wood-based industry. Malaysian Forester. 2008, 71, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Shukri, M.; Ainul Mardhiah, A. Willingness to pay for certified wood materials among builders’ joinery and carpentry manufacturers in Malaysia. Malaysian Forester. 2014, 77, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Saadun, N.; Noor, K.M.; Azhar, B.; Omar, M.; Hishamudin, S. Export Performance of Tropical Timber Products Certified by the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme. Article in Journal of Sustainability Science and Management. 2019, 14, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Malaysian Timber Certification Council (MTCC). Annual Report 2018. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Timber Certification Council. 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).