1. Introduction

The Mediterranean Sea has long been a cornerstone for marine biodiversity and a hub for fisheries and aquaculture activities [

1]. Among its valuable marine species, the gilthead seabream (

Sparus aurata) holds a significant position due to its ecological and economic importance. In 2022, total aquaculture production of seabream in Europe and the Mediterranean was estimated at 320,630 tonnes, representing a 1.8% increase compared to 2021. The estimated first-sale value reached 1,574.8 million euros [

2].

Traditionally a target of artisanal fisheries, the increasing demand for seabream in global markets has propelled the growth of marine aquaculture, making it a focal species in Mediterranean aquaculture. The cultivation of seabream has evolved into a highly sophisticated industry, leveraging advances in breeding, nutrition, and environmental monitoring to optimize production and sustainability [

3].

The natural distribution of seabream, which thrives in coastal and estuarine habitats across the Mediterranean, has historically supported robust fisheries. These fisheries, while culturally ingrained and economically vital, face growing challenges such as overfishing, habitat degradation, and climate change. As a response, aquaculture has emerged as a sustainable alternative to supplement the declining yields from wild stocks [

4]. Currently, gilthead seabream ranks among the most farmed fish species in the Mediterranean, with production concentrated in countries such as Greece, Turkey, and Spain [

1]. The ability of this species to tolerate a wide range of salinities and temperatures has further solidified its role in the expansion of marine aquaculture.

The evolution of seabream aquaculture, from traditional net pens to modern recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), reflects the industry's commitment to improving yield and environmental stewardship. Early farming practices, characterized by extensive systems with limited control over environmental variables, often faced challenges such as disease outbreaks and inefficient feed conversion. However, advances in genetic selection, feed formulation, and water quality management have revolutionized the sector. Modern systems now incorporate real-time monitoring technologies and biosecurity protocols, reducing the environmental footprint and enhancing fish welfare [

1].

1.1. Benefits and Drawbacks of Marine Aquaculture in the Mediterranean

Marine aquaculture offers numerous advantages, including the ability to meet growing seafood demand without exacerbating pressures on wild fish populations. The cultivation of seabream provides high-quality protein with a favorable fatty acid profile, contributing to food security and human health. Additionally, the economic benefits extend to job creation and rural development in coastal communities [

1].

However, the industry is not without its drawbacks. Concerns over nutrient enrichment, the spread of diseases, and the potential for genetic introgression with wild populations persist. Regulatory frameworks and adherence to sustainability certifications have sought to mitigate these impacts, but challenges remain, particularly in regions with less stringent enforcement. Moreover, the reliance on fishmeal and fish oil in seabream diets raises questions about the sustainability of feed sources, prompting research into alternative ingredients such as insect meal and algae-based oils [

3].

1.2. Methodologies and Decision-Making Factors in Seabream Aquaculture

Research and development in seabream aquaculture have focused on optimizing production efficiency while minimizing environmental impacts. Experimental studies have evaluated stocking densities, feed formulations, and water quality parameters to establish best practices. The use of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) systems, where seabream is co-cultured with species such as seaweed and shellfish, has shown promise in enhancing nutrient recycling and reducing environmental impacts [3, 5].

Decision-making in the industry often involves balancing economic viability with ecological considerations. Factors such as site selection, water quality, and regulatory compliance play critical roles in the success of aquaculture operations. Additionally, consumer preferences and market trends influence product differentiation strategies, such as organic certification or valorization of niche markets (

https://www.iemed.org/publication/aquaculture-in-the-mediterranean/?utm_source=chatgpt.com).

1.3. Advantages and Limitations of HR-MAS in Fish Studies

In recent years, Metabolomics and Lipidomics have emerged as pivotal tools in understanding biochemical processes in aquatic species, offering comprehensive insights into their physiological state and responses to environmental stressors [

6]. The application of high-resolution magic angle spinning (HR-MAS) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in these fields has gained considerable attention for its non-destructive nature, enabling direct analysis of complex biological matrices. This technique has proven particularly valuable in fish studies, where maintaining tissue integrity is essential for accurate metabolic profiling. Moreover, HR-MAS facilitates the evaluation of biochemical alterations associated with fish spoilage during storage, addressing critical concerns in food safety and quality management [

7].

Metabolomics and Lipidomics are integral to unraveling metabolic networks, revealing biomarkers, and understanding the dynamics of spoilage pathways. In fish, spoilage is a multifactorial process driven by enzymatic activity, microbial proliferation, and oxidative degradation of lipids. Despite advancements in analytical approaches, challenges persist in accurately characterizing these processes due to the complexity of the biochemical milieu in fish tissue. HR-MAS spectroscopy, by enabling the in-situ analysis of intact tissue, bridges this gap, providing both qualitative and quantitative data with exceptional sensitivity and resolution. Unlike conventional techniques such as gas or liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry, HR-MAS eliminates the need for extensive sample preparation, reducing potential artifacts and preserving the native biochemical state [

7].

The evolution of HR-MAS methodologies from early feasibility studies to sophisticated analytical workflows underscores its transformative potential in fisheries science. Initial applications primarily focused on the identification of major metabolites and lipids; however, recent advancements have expanded its scope to include detailed kinetic analyses of spoilage processes and differentiation of storage conditions. These developments have been driven by innovations in pulse sequences, enhanced spectral resolution, and improved quantitative capabilities, collectively enabling deeper insights into metabolic and lipidomic dynamics [

7].

HR-MAS offers numerous advantages, including minimal sample processing, preservation of tissue architecture, and high reproducibility of results. Its ability to analyze both hydrophilic and hydrophobic metabolites simultaneously makes it a versatile choice for metabolomic and lipidomic investigations. However, this technique is not without limitations. The relatively high cost of instrumentation, limited access to facilities, and the requirement for specialized expertise in spectral interpretation may pose challenges for routine adoption. Furthermore, while HR-MAS excels in providing comprehensive profiles, it is less effective in detecting low-abundance compounds compared to advanced mass spectrometry techniques [

8].

The application of HR-MAS to evaluate fish spoilage during storage exemplifies its practical utility. Key studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in monitoring oxidative stress markers, volatile compounds, and lipid oxidation products, all of which are critical indicators of quality deterioration [

8]. Comparative analyses using HR-MAS have also elucidated the effects of different preservation methods, such as freezing, vacuum packaging, and modified atmosphere storage, on metabolic and lipidomic profiles [8, 9]. These findings have direct implications for the seafood industry, enabling the optimization of storage practices to prolong shelf life and ensure product safety [

7].

The cultivation of gilthead seabream in the Mediterranean exemplifies the potential of aquaculture to address global food security challenges while supporting regional economies. However, realizing this potential requires continuous innovation and a commitment to sustainability. By integrating advanced technologies and adopting ecosystem-based approaches, the aquaculture industry can mitigate its impacts and ensure the long-term viability of seabream production. Future research should prioritize the development of sustainable feed alternatives, the refinement of biosecurity measures, and the integration of aquaculture with broader marine spatial planning initiatives.

HR-MAS NMR spectroscopy represents a robust and innovative approach for metabolomic and lipidomic studies in fish, offering unparalleled insights into their biochemical composition and spoilage mechanisms. Its capacity to preserve tissue integrity and provide comprehensive data positions it as an indispensable tool in both research and industrial settings. However, researchers must weigh its benefits against practical limitations, considering factors such as cost, accessibility, and analytical objectives. The continuous evolution of HR-MAS methodologies, coupled with advancements in computational tools for spectral analysis, promises to further enhance its applicability in fisheries science. Future studies should focus on integrating HR-MAS with complementary techniques to achieve a holistic understanding of fish spoilage dynamics, fostering advancements in quality control and food safety [

10].

The objective of this study is to investigate the metabolic and biochemical adaptations of the gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) under varying environmental and nutritional conditions, utilizing High-Resolution Magic Angle Spinning (HRMAS) NMR spectroscopy. By characterizing the metabolomic profiles of muscle and liver tissues, this research aims to identify biomarkers associated with growth performance, stress response, and overall health status. Particular emphasis is placed on evaluating the condition factor (K) as a critical parameter linking metabolic alterations to the fish's somatic growth and welfare [

7]. Additionally, the study seeks to assess the impact of specific dietary formulations and environmental stressors on the fish's physiological state, with the ultimate goal of optimizing aquaculture practices for sustainable and efficient production of

S. aurata.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

D2O (99.9%) and sodium (3-trimethylsilyl)-2,2,3,3-tetradeuteriopropionate (TSP) were purchased from SDS and Sigma–Aldrich, respectively.

2.2. Specimen Collection and Sample Preparation

Three individuals of gilthead seabream were collected from wild populations (via fishing) and aquaculture, with the farmed fish originating from two different locations: Spain and Greece. The fish was purchased from a local fish market in June 2023. The specimens were stored under refrigeration at 4°C for 18 to 23 days, simulating pre-sale storage conditions. Tissue samples were collected five times from wild-caught seabream and four times from farmed specimens. All samples were preserved at -80°C for subsequent analysis.

Wild gilthead seabream had an average weight of 288.3 + 35.9 g, whereas those farmed in aquaculture along the Spanish coasts had an average weight of 510.4 + 95.6 g, and those farmed along the Greek coasts had an average weight of 501.0 + 23.4 g. The Total Length (TL), measured from the tip of the snout to the end of the longest caudal (tail) fin lobe, with the lobes compressed along the midline, was 28.0 + 1.3 cm, 30.1 + 1.6 cm, and 29.7 + 0.3 cm for wild seabream, those farmed along the Spanish coasts, and those farmed along the Greek coasts, respectively. The Fork Length (FL), measured from the tip of the snout to the fork of the caudal fin, was 26.0 + 0.9 cm, 28.5 + 0.9 cm, and 28.0 + 0.5 cm for wild seabream, those farmed along the Spanish coasts, and those farmed along the Greek coasts, respectively. The weight difference between wild and farmed seabream ranged from 42.5% to 43.5%, while the length difference ranged from 7% to 8%.

Following classification, a portion of fish muscle was extracted and frozen at -80 ºC until the HR-MAS analysis.

2.3. NMR Experiments

Approximately 8–10 mg of white muscle tissue from smoked Atlantic salmon were analyzed using HRMAS at 4 °C to minimize tissue deterioration and prevent the degradation of thermolabile compounds. ¹H-HRMAS NMR spectroscopy was performed at 500.13 MHz on a Bruker AMX500 spectrometer operating at 11.7 T.

The samples were loaded into a 50 μl zirconium oxide rotor equipped with a cylindrical insert, along with 20 μl of a 0.1 mM TSP solution in D₂O. Experimental runs were conducted at the lowest possible spinning rates to minimize structural or chemical alterations during the analysis.

Standard solvent-suppressed spectra (NOESYPRESAT), TOCSY-HRMAS, and HSQC-MAS were acquired at the facilities of the Complutense University of Madrid (Centro de Bioimagen Complutense BIOIMAC) following the protocol outlined in the referenced article [

9], using identical parameters for all experiments. Two-dimensional (2D) NMR experiments were conducted on the gilthead seabream samples, and the resulting 2D spectra were utilized to aid in the assignment of signals in the ¹H-HRMAS NMR spectra. All experiments are available in the repository Mendeley Data (see Data Availability Statement section).

3. Results

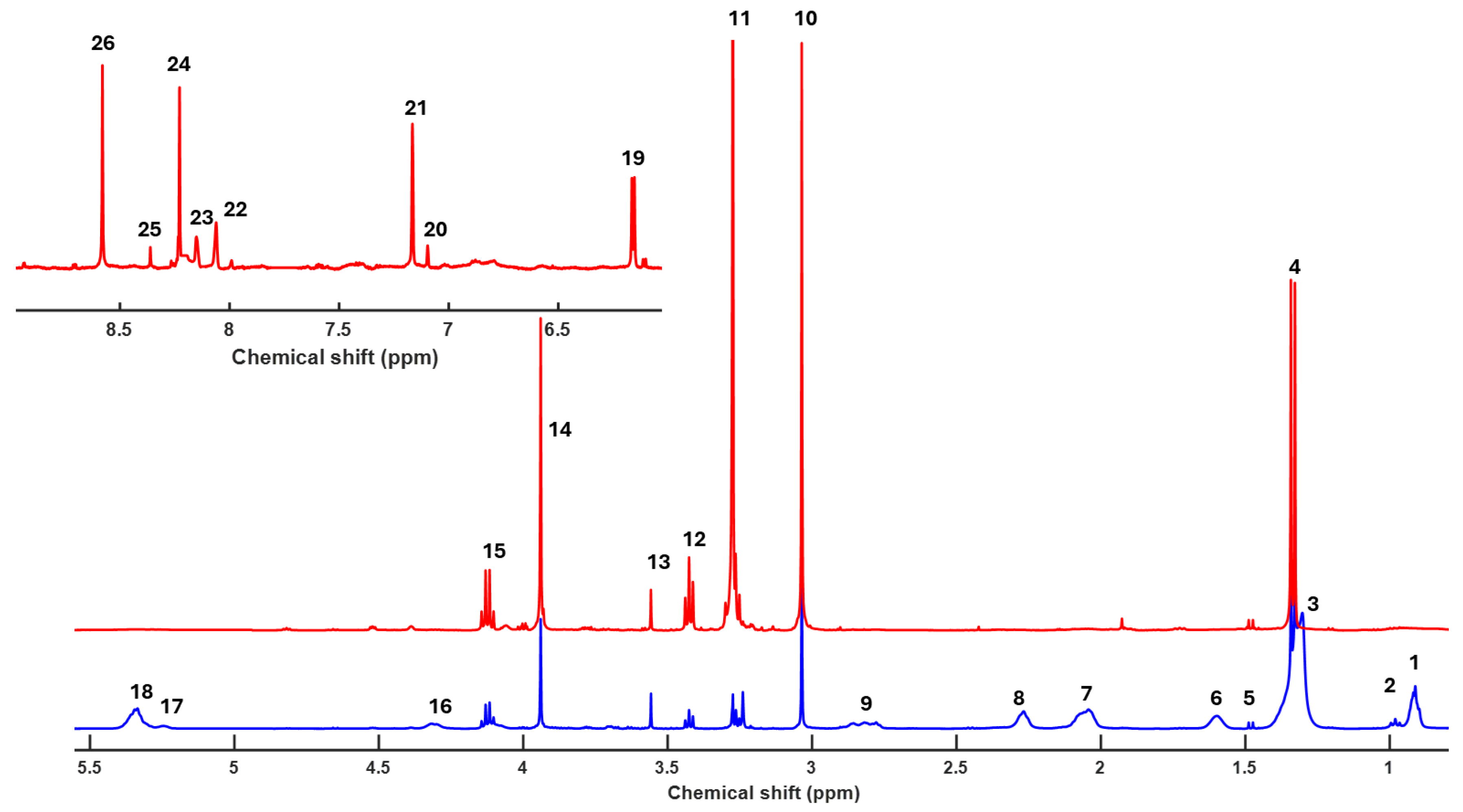

3.1. Analysis of HR-MAS Spectra

Figure 1 presents the 1H-HRMAS spectrum at 500 MHz of muscle samples from wild gilthead seabream and farmed gilthead seabream raised in marine aquaculture systems. Signal assignments were based on 1H-HRMAS spectra complemented with 2D homonuclear correlation experiments (TOCSY-HRMAS and HSQC-HRMAS) [

9]. These assignments were validated against published spectra of standards available in databases [8, 9] (HMDB;

https://hmdb.ca/), as well as other published studies involving fish muscle or fish oil samples [11-19].

The samples from three individuals of each type (wild, farmed in Spain, and farmed in Greece) demonstrated excellent reproducibility, both during the initial analysis and throughout cold storage at 4 °C. It is important to note that 1H-MAS is a direct measurement technique applied to muscle tissue, precluding the possibility of sample mixing [

9].

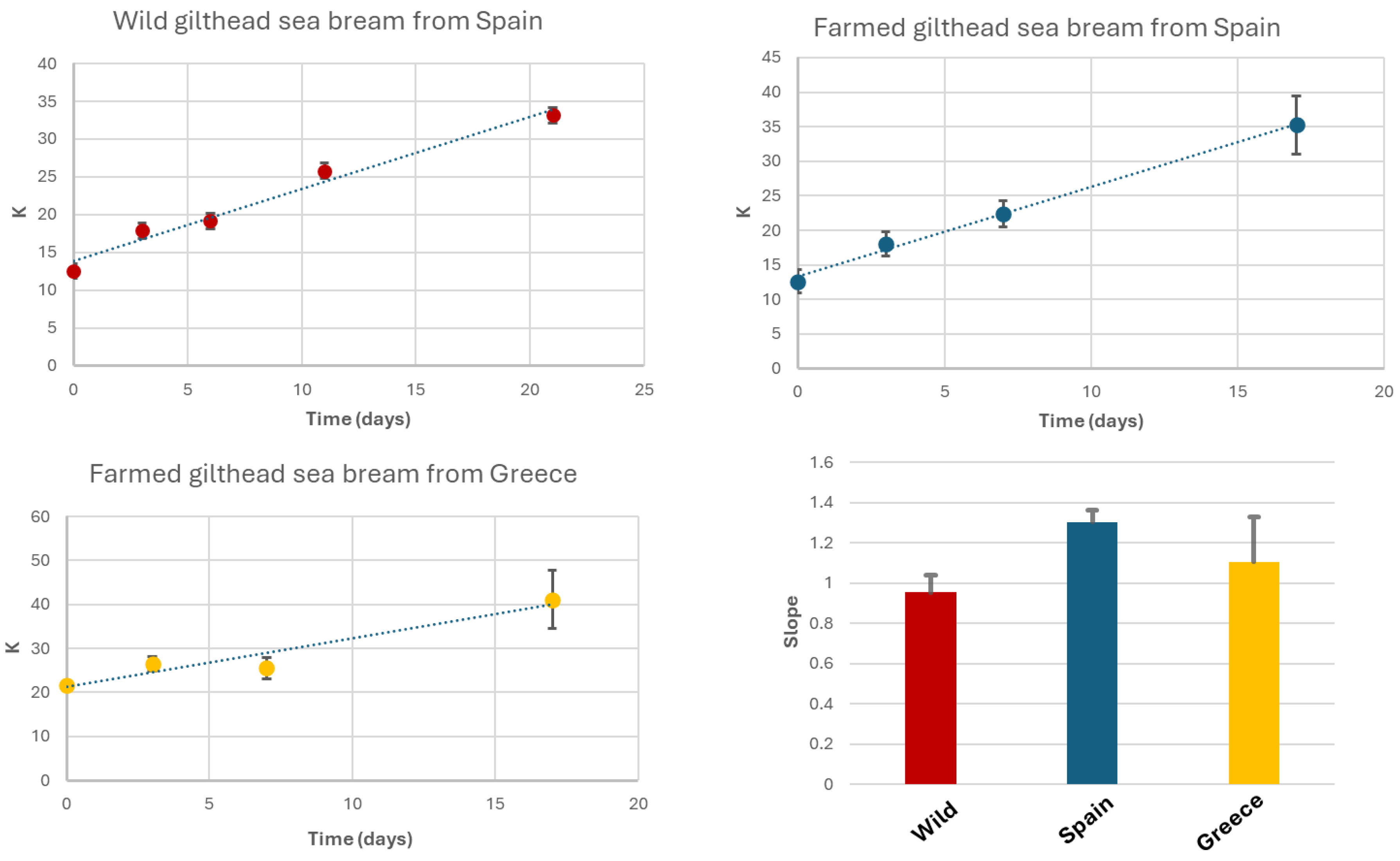

3.2. Deterioration Patterns in Samples by Origin

To calculate the K-value, the corresponding signals from the 1H-HRMAS spectra were integrated. These signals include the doublet of IMP at 6.14 ppm (CH-1 Ribose), the doublet of HxR at 6.09 ppm (CH-1 Ribose), the singlet of Hx at 8.18 ppm (CH-8), and the singlet of ATP/ADP/AMP at 8.49 ppm (CH-2 Purine) . Samples were stored at 4 °C under conditions similar to typical household refrigeration. Under these storage conditions, K-values increased by up to 33% after 21 days for wild gilthead seabream, 35% for seabream farmed in Spanish coastal waters after 17 days, and 41% for seabream farmed in Greek coastal waters after the same 17-day period [

7].

Initial K-values were 12.5% for wild seabream, 12.6% for seabream farmed in Spain, and 21.7% for seabream farmed in Greece. The slope values for K-value increase were 0.95, 1.30, and 1.10 for wild gilthead seabream, farmed seabream from Spain, and farmed seabream from Greece, respectively. The R² values of the linear regressions for K-value variations were 0.98, 0.99, and 0.92 for wild seabream, Spanish farmed seabream, and Greek farmed seabream, respectively. These values are comparable to those reported in other studies, despite differences in fish species or analytical techniques [

7]. The main distinction lies in the slope values, which in our case are slightly lower than those reported by other authors [

7].

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of HR-MAS Analysis

High-resolution magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (HR-MAS NMR) offers multiple advantages in metabolomic studies, particularly for complex tissues like fish muscle. HR-MAS enables the analysis of samples in their natural state, without requiring extractions that could alter metabolite concentrations. This ensures that the results accurately represent the tissue's actual conditions. Compounds such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), which are highly volatile and difficult to quantify using conventional techniques, can be detected with greater precision using HR-MAS. This is because the technique does not involve separation processes that could lead to compound loss [

7].

HR-MAS produces high-resolution spectra that allow for the simultaneous identification and quantification of multiple metabolites, including those present in low concentrations. This is particularly important for comparative studies between tissues under different conditions. Unlike destructive techniques such as extractions, HR-MAS partially preserves cellular structure during analysis, facilitating correlations between metabolite levels and tissue histology. The technique is especially valuable for comparing complex biological samples, such as wild and farmed gilthead seabream (

Figure 1), providing key insights into how environmental and dietary conditions affect metabolism [

20].

Data obtained from HR-MAS are amenable to multivariate statistical analyses such as principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), enabling the identification of specific metabolic patterns and key biomarkers [

21].

4.2. Preliminary Discussion on Lipid Composition of Wild and Farmed Gilthead Seabream

The lipid composition of farmed gilthead seabream shows notable similarities to that of farmed salmon [

8], despite these being different species. This highlights the direct impact of formulated diets in marine aquaculture systems. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating how aquaculture diets, predominantly based on fish oils and meals rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), significantly influence the lipid profile of farmed fish [22, 23].

In particular, omega-3 fatty acids such as DHA (22:6 n-3) and EPA (20:5 n-3) constitute a significant proportion of PUFAs in farmed seabream. This similarity arises from the dietary ingredients used in both cases, which are designed to promote growth and meet market standards for nutritional quality [

24].

Previous studies have shown that lipid accumulation in the myocytes of farmed fish is closely related to diet composition and physiological mechanisms regulating energy storage. These studies indicate that the high availability of PUFAs in lipid-rich diets promotes triglyceride accumulation in myocytes, potentially impacting muscle metabolism and fillet quality [

25].

Lipid accumulation in myocytes is regulated by several key genes involved in lipid metabolism. Among these, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) play a crucial role. PPARγ promotes adipocyte differentiation and triglyceride accumulation, while PPARα regulates fatty acid oxidation, balancing energy storage and utilization. Additionally, fatty acid-binding protein 3 (FABP3) facilitates intracellular fatty acid transport to storage or utilization sites [

26].

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP-1c) stimulates the expression of lipogenic genes, including those involved in triglyceride and fatty acid synthesis. Genes like FASN (fatty acid synthase) and DGAT (acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase) contribute to lipid storage by catalyzing de novo synthesis and triglyceride assembly, respectively. Conversely, lipid oxidation is driven by genes such as CPT1 (carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1), which regulates fatty acid transport to mitochondria, and ACOX, which initiates oxidation in peroxisomes [

27].

In contrast, wild seabream exhibits a significantly different lipid profile (

Figure 1), characterized by a lower overall lipid concentration and a higher prevalence of polar metabolites such as carbohydrates, amino acids, osmolytes, and organic acids. This can be attributed to the diverse, protein-rich diet available in their natural environment, which supports a metabolism oriented toward different energy and functional demands. Appreciable amounts of triglycerides were not detected in wild seabream myocytes, supporting the hypothesis of reduced lipid storage due to a diet lacking the high oil levels found in aquaculture feeds [

28].

The comparison between farmed and wild seabream underscores the determining influence of diet and highlights the specific metabolic adaptations of each environment. High levels of DHA and EPA in farmed seabream and salmon confirm that the lipid profile in aquaculture fish is directly related to dietary composition. In contrast, the lower concentrations of these compounds in wild seabream reflect limited access to marine PUFA sources in their natural diet and excellent adaptation to the natural environment [

29].

These results have important implications for understanding metabolic mechanisms in marine fish and for the aquaculture industry. The potential to adjust the lipid profile of farmed fish through dietary modifications could optimize both production efficiency and final product quality. It is worth noting that excessive triglyceride accumulation in myocytes could pose severe metabolic issues for farmed fish [

30].

4.3. Metabolic Trade-Offs in Gilthead Seabream

Gilthead seabream faces a series of metabolic trade-offs arising from its environment, diet, and physiological activity. These trade-offs reflect adaptations to optimize resource utilization, balancing energy storage with expenditure on critical activities such as locomotion, growth, and reproduction. As a pelagic species, seabream is an active swimmer, necessitating constant access to energy. This limits excessive lipid accumulation, favoring instead the rapid mobilization of stored fatty acids for oxidation. Excessive lipid storage could increase buoyancy, disrupting hydrodynamic balance during swimming [

31].

The activation of genes such as SREBP-1c is moderated in seabream due to its natural diet, which is rich in essential fatty acids (PUFAs). This limits the need for de novo lipogenesis and prioritizes the mobilization of stored lipids for energy demands [

32].

In wild seabream, variability in food availability can limit lipid storage, whereas farmed seabream, provided with a constant lipid-rich diet, achieves higher reproductive success [

30]. During reproductive stages, seabream redirects significant energy reserves toward gonadal development, reducing energy available for somatic growth.

Environmental factors such as temperature and food availability in pelagic habitats cause fluctuations that activate stress responses mediated by cortisol. This diverts energy from anabolic processes, such as growth and reserve accumulation, to catabolic mechanisms for stress management [

33]. These metabolic trade-offs highlight the complex physiological adaptations of gilthead seabream to its environment and feeding conditions.

4.4. Metabolite Profiles of Wild and Farmed Gilthead Seabream

Wild gilthead seabream exhibit significantly higher levels of metabolites such as creatine, taurine, lactate, and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) compared to farmed seabream (

Figure 1). These compounds are intrinsically linked to muscle activity and tissue quality. In wild seabream, the healthy muscle, rich in these metabolites, reflects higher physical activity, in contrast to farmed seabream, whose muscle contains elevated levels of lipids stored in myocytes [23, 34-38]. Creatine is essential for the rapid storage and release of energy during sustained muscle contractions. Dietary supplementation of creatine in gilthead seabream has been shown to improve muscle quality, indicating its vital role in energy metabolism [

39]. Taurine plays a key role as an antioxidant and in stabilizing cell membranes, contributing to muscle tissue integrity. It neutralizes reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stimulates the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT). Dietary taurine supplementation has been found to enhance antioxidant enzyme activity and immune response in fish, highlighting its importance in maintaining muscle health [

40]. Lactate indicates greater anaerobic activity in muscle tissue, which is often associated with higher physical exertion levels in wild fish. Elevated lactate levels in wild seabream suggest a metabolism adapted to burst swimming and escape responses.

TMAO concentration is up to ten times higher in wild seabream. This compound (TMAO) has multiple functions. It acts as a compatible osmolyte, stabilizing proteins in high osmotic pressure environments, such as the pelagic habitat. TMAO is produced in the liver from TMA, a compound generated in the intestine by microbial activity. The intestinal microbiota of wild seabream is likely more diverse due to the absence of antibiotic treatments, favoring higher TMAO production. In farmed seabream, the use of antibiotics alters this microbiota, reducing the levels of this key compound [38, 41]. TMAO enhances osmotic tolerance and is essential for protein stability. The low concentration of TMAO in farmed seabream could reflect reduced adaptation to the natural environment and diminished muscle quality. Conversely, in humans, excessive TMAO accumulation is associated with cardiovascular diseases, highlighting its dual role in different biological contexts [42, 43].

In wild seabream, elevated taurine levels correlate with greater antioxidant capacity, enabling them to cope with oxidative stress associated with intense physical activity and environmental fluctuations. Diets in aquaculture systems often lack sufficient taurine, potentially leading to reduced antioxidant capacity in farmed seabream. This is also associated with increased susceptibility to oxidative damage and inferior muscle quality. Taurine also protects against oxidative damage caused by environmental pollutants and overcrowding in farmed fish [

44]. The antioxidant protection provided by taurine contributes to muscle structure preservation, reducing lipid peroxidation and improving fillet quality. Greater resistance to oxidative stress enhances overall fish well-being, promoting more efficient growth. Adding taurine to farmed fish diets is a key strategy to improve their antioxidant capacity and compensate for the limitations of plant-based diet ingredients [

44].

4.5. Discussion on Key Metabolites and K-Value Assessment

The K-value, also known as the freshness index, is widely used to monitor fish quality. It reflects the degradation of ATP and its derivatives, indicating freshness loss through hypoxanthine accumulation. The formula for the K-value is:

K=([HxR]+[Hx])/([ATP]+[ADP]+[AMP]+[IMP]+[HxR]+[Hx])×100

Where HxR is hypoxanthine riboside (inosine), Hx is hypoxanthine, and ATP, ADP, AMP, and IMP represent adenosine nucleotides and derivatives [7, 45]. A low K-value (<20%) indicates fresh fish, while values above 50% suggest advanced spoilage.

In our study, farmed seabream from Greece exhibited an initial K-value above 20%, potentially due to inadequate handling during transportation. The K-value is closely correlated with sensory properties such as taste, texture, and odor.

Using HR-MAS, we directly quantified IMP, HxR, and Hx without prior extraction, preserving sample integrity and achieving high reproducibility. The K-value enables continuous freshness monitoring during storage and transportation, supports the implementation of quality protocols in the fishing and aquaculture industries, and identifies conditions that extend fish shelf life, minimizing losses due to spoilage.

5. Conclusions

Gilthead seabream exhibits a series of metabolic trade-offs designed to optimize energy and nutrient utilization in its pelagic environment. Understanding these adaptations is essential for managing wild populations and improving aquaculture practices, ensuring a balance between biological performance, fish quality, health status, and sustainability. Differences in muscle quality and metabolism between wild and farmed seabream reflect specific metabolic adaptations to environment and diet. Elevated levels of metabolites such as creatine, taurine, lactate, and TMAO in wild seabream indicate greater muscle activity and a more diverse microbiota. Conversely, limitations in microbiota diversity and higher lipid storage in farmed seabream highlight the effects of aquaculture practices on metabolism and tissue quality.

The K-value emerges as a reliable indicator of fish freshness, and HR-MAS offers an innovative and efficient methodology for quality control in both wild and farmed seabream. Additionally, further studies exploring gene expression related to lipid metabolism in wild and farmed seabream could complement this analysis, providing deeper insights into the observed lipid profile differences.

Furthermore, additional studies exploring gene expression related to lipid metabolism in wild and farmed gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) could complement this analysis, providing a deeper understanding of the observed differences in lipid profiles. Recent research has characterized the stress proteome and metabolome in Sparus aurata, highlighting altered pathways in the liver, a central organ in stress response. These findings could offer valuable insights for future investigations into fish welfare [

5].

Author Contributions

F.C.M.-E. designed the experiment, performed the experiment, analyzed the data, wrote and revised the manuscript, and generated the figures. P.S.-J. designed the experiment, analyzed the data, wrote and revised the manuscript, and collected the fish samples. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONVOCATORIA DEL PROGRAMA PROPIO DEL CENTRO DE GASTRONOMÍA DEL MEDITERRÁNEO (Gasterra 2022-23) UA_DENIA PARA EL FOMENTO DE LA I+D+i EN El ÁMBITO DE LA GASTRONOMÍA (GASTERRA 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Marhuenda, Frutos (2024), “HR-MAS Sparus aurata”, Mendeley Data, V2, doi: 10.17632/rjmjj5vwf2.2.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Palmira Villa-Valverde (Centro de Bioimagen Complutense BIOIMAC, Universidad Complutense de Madrid) for technical assistance with HR-MAS experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture (sofia). Rome, Italy FAO, 2022, #266 p.

- APROMAR. aquaculture in spain 2023. . 2023.

- Mhalhel, K., M. Levanti, F. Abbate, R. Laurà, M. C. Guerrera, M. Aragona, C. Porcino, M. Briglia, A. Germanà and G. Montalbano. Review on gilthead seabream (sparus aurata) aquaculture: Life cycle, growth, aquaculture practices and challenges. 11. 2023.

- Toledo-Guedes, K., J. Atalah, D. Izquierdo-Gomez, D. Fernandez-Jover, I. Uglem, P. Sanchez-Jerez, P. Arechavala-Lopez and T. Dempster. "Domesticating the wild through escapees of two iconic mediterranean farmed fish species." Scientific Reports 14 (2024): 23772. 10.1038/s41598-024-74172-3. [CrossRef]

- Raposo de Magalhães, C., A. P. Farinha, G. Blackburn, P. D. Whitfield, R. Carrilho, D. Schrama, M. Cerqueira and P. M. Rodrigues. Gilthead seabream liver integrative proteomics and metabolomics analysis reveals regulation by different prosurvival pathways in the metabolic adaptation to stress. 23. 2022.

- Lindon, J. C., J. K. Nicholson and E. Holmes. The handbook of metabonomics and metabolomics. Elsevier Science, 2011.

- Heude, C., E. Lemasson, K. Elbayed and M. Piotto. "Rapid assessment of fish freshness and quality by 1h hr-mas nmr spectroscopy." Food Analytical Methods 8 (2015): 907-15. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12161-014-9969-5. [CrossRef]

- Villa, P., D. Castejon, M. Herraiz and A. Herrera. "H-1-hrmas nmr study of cold smoked atlantic salmon (salmo salar) treated with e-beam." Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 51 (2013): 350-57. [CrossRef]

- Castejón, D., P. Villa, M. M. Calvo, G. Santa-María, M. Herraiz and A. Herrera. "1h-hrmas nmr study of smoked atlantic salmon (salmo salar)." Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 48 (2010): 693-703. [CrossRef]

- Ntzimani, A., R. Angelakopoulos, N. Stavropoulou, I. Semenoglou, E. Dermesonlouoglou, T. Tsironi, K. Moutou and P. Taoukis. "Seasonal pattern of the effect of slurry ice during catching and transportation on quality and shelf life of gilthead sea bream." Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10 (2022): 443. [CrossRef]

- AURSAND, M., J. RAINUZZO and H. GRASDALEN. "Quantitative high-resolution c-13 and h-1 nuclear-magnetic-resonance of omega-3-fatty-acids from white muscle of atlantic salmon (salmo-salar)." Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 70 (1993): 971-81. [CrossRef]

- Anedda, R., C. Piga, V. Santercole, S. Spada, E. Bonaglini, R. Cappuccinelli, G. Mulas, T. Roggio and S. Uzzau. "Multidisciplinary analytical investigation of phospholipids and triglycerides in offshore farmed gilthead sea bream (sparus aurata) fed commercial diets." Food Chemistry 138 (2013): 1135-44. [CrossRef]

- Aursand, M., I. Standal and D. Axelson. "High-resolution (13)c nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy pattern recognition of fish oil capsules." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55 (2007): 38-47. [CrossRef]

- Falch, E., T. Storseth and A. Aursand. "Multi-component analysis of marine lipids in fish gonads with emphasis on phospholipids using high resolution nmr spectroscopy." Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 144 (2006): 4-16. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, T., M. Aursand, Y. Hirata, I. Gribbestad, S. Wada and M. Nonaka. "Nondestructive quantitative determination of docosahexaenoic acid and n-3 fatty acids in fish oils by high-resolution h-1 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy." Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 77 (2000): 737-48. [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, S., H. Pedersen and S. Engelsen. "Application of chemometrics to low-field (1)h nmr relaxation data of intact fish flesh." Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 79 (1999): 1793-802. [CrossRef]

- Suarez, E., P. Mugford, A. Rolle, I. Burton, J. Walter and J. Kralovec. "C-13-nmr regioisomeric analysis of epa and dha in fish oil derived triacylglycerol concentrates." Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 87 (2010): 1425-33. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N., E. Goicoechea, M. Manzanos and M. Guillen. "H-1 nmr study of the changes in brine- and dry-salted sea bass lipids under thermo-oxidative conditions: Both salting methods reduce oxidative stability." European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 117 (2015): 440-49. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L., S. Trattner, J. Pickova, P. Gomez-Requeni and A. Moazzami. "H-1 nmr-based metabolomics studies on the effect of sesamin in atlantic salmon (salmo salar)." Food Chemistry 147 (2014): 98-105. [CrossRef]

- Cai, H. H., Y. S. Chen, X. H. Cui, S. H. Cai and Z. Chen. "High-resolution h-1 nmr spectroscopy of fish muscle, eggs and small whole fish via hadamard-encoded intermolecular multiple-quantum coherence." Plos One 9 (2014): <Go to ISI>://WOS:000330237000098. [CrossRef]

- Augustijn, D., H. J. M. de Groot and A. Alia. "Hr-mas nmr applications in plant metabolomics." Molecules 26 (2021): <Go to ISI>://WOS:000624188000001. [CrossRef]

- Houston, S. J. S., V. Karalazos, J. Tinsley, M. B. Betancor, S. A. M. Martin, D. R. Tocher and O. Monroig. "The compositional and metabolic responses of gilthead seabream (sparus aurata) to a gradient of dietary fish oil and associated n-3 long-chain pufa content." British Journal of Nutrition 118 (2017): 1010-22. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/84301CB4F616131CACB2C2E07141C1C1. [CrossRef]

- Stubhaug, I., D. R. Tocher, J. G. Bell, J. R. Dick and B. E. Torstensen. "Fatty acid metabolism in atlantic salmon (salmo salar l.) hepatocytes and influence of dietary vegetable oil." Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1734 (2005): 277-88. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1388198105000880. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M. S., A. Obach, L. Arantzamendi, D. Montero, L. Robaina and G. Rosenlund. "Dietary lipid sources for seabream and seabass: Growth performance, tissue composition and flesh quality." Aquaculture Nutrition 9 (2003): 397-407. [CrossRef]

- Vergara, J. M., G. López-Calero, L. Robaina, M. J. Caballero, D. Montero, M. S. Izquierdo and A. Aksnes. "Growth, feed utilization and body lipid content of gilthead seabream (sparus aurata) fed increasing lipid levels and fish meals of different quality." Aquaculture 179 (1999): 35-44. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0044848699001507. [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, M., A. Felici, R. Branciari, M. Trabalza-Marinucci, R. Galarini, M. Biagetti, A. Manfrin, L. Boriani, E. Radicchi, C. Sebastiani, et al. Gene expression study in gilthead seabream (sparus aurata): Effects of dietary supplementation with olive oil polyphenols on immunity, metabolic, and oxidative stress pathways. 25. 2024.

- Turkmen, S., E. Perera, M. J. Zamorano, P. Simó-Mirabet, H. Xu, J. Pérez-Sánchez and M. Izquierdo. Effects of dietary lipid composition and fatty acid desaturase 2 expression in broodstock gilthead sea bream on lipid metabolism-related genes and methylation of the fads2 gene promoter in their offspring. 20. 2019.

- Wassef, E. A., S. H. Shalaby and N. E. Saleh. "Comparative evaluation of sunflower oil and linseed oil as dietary ingredient for gilthead seabream (sparus aurata) fingerlings." OCL 22 (2015). [CrossRef]

- DÍAz-LÓPez, M., M. J. PÉRez, N. G. Acosta, D. R. Tocher, S. Jerez, A. Lorenzo and C. RodrÍGuez. "Effect of dietary substitution of fish oil by echium oil on growth, plasma parameters and body lipid composition in gilthead seabream (sparus aurata l.)." Aquaculture Nutrition 15 (2009): 500-12. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A., K. B. Andree, I. Sanahuja, P. G. Holhorea, J. À. Calduch-Giner, S. Morais, J. J. Pastor, J. Pérez-Sánchez and E. Gisbert. "Bile salt dietary supplementation promotes growth and reduces body adiposity in gilthead seabream (sparus aurata)." Aquaculture 566 (2023): 739203. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0044848622013217. [CrossRef]

- Perelló-Amorós, M., J. Fernández-Borràs, A. Sánchez-Moya, E. J. Vélez, I. García-Pérez, J. Gutiérrez and J. Blasco. "Mitochondrial adaptation to diet and swimming activity in gilthead seabream: Improved nutritional efficiency." Frontiers in Physiology 12 (2021): https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2021.678985. [CrossRef]

- Benedito-Palos, L., G. Ballester-Lozano and J. Pérez-Sánchez. "Wide-gene expression analysis of lipid-relevant genes in nutritionally challenged gilthead sea bream (sparus aurata)." Gene 547 (2014): 34-42.

- Feidantsis, K., H. O. Pörtner, E. Vlachonikola, E. Antonopoulou and B. Michaelidis. "Seasonal changes in metabolism and cellular stress phenomena in the gilthead sea bream (sparus aurata)." Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 91 (2018): 878-95.

- Calo, J., M. Conde-Sieira, S. Comesaña, J. L. Soengas and A. M. Blanco. "Fatty acids of different nature differentially modulate feed intake in rainbow trout." Aquaculture 563 (2023): 738961. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004484862201078X. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.-M., K. Choi, A. Gonzalez and T. Omlin. "Metabolic fuel kinetics in fish: Swimming, hypoxia and muscle membranes." Journal of Experimental Biology 219 (2016): 250-58. 10.1242/jeb.125294. [CrossRef]

- Ould Ahmed Louly, A. W., E. M. Gaydou and M. V. Ould El Kebir. "Muscle lipids and fatty acid profiles of three edible fish from the mauritanian coast: Epinephelus aeneus, cephalopholis taeniops and serranus scriba." Food Chemistry 124 (2011): 24-28. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308814610006710. [CrossRef]

- Glencross, B. D. "Exploring the nutritional demand for essential fatty acids by aquaculture species." Reviews in Aquaculture 1 (2009): 71-124. [CrossRef]

- Badaoui, W., F. C. Marhuenda-Egea, J. M. Valero-Rodriguez, P. Sanchez-Jerez, P. Arechavala-Lopez and K. Toledo-Guedes. "Metabolomic and lipidomic tools for tracing fish escapes from aquaculture facilities." ACS Food Science & Technology 4 (2024): 871-79. 10.1021/acsfoodscitech.3c00589. [CrossRef]

- Schrama, D., M. Cerqueira, C. S. Raposo, A. M. Rosa da Costa, T. Wulff, A. Gonçalves, C. Camacho, R. Colen, F. Fonseca and P. M. Rodrigues. "Dietary creatine supplementation in gilthead seabream (sparus aurata): Comparative proteomics analysis on fish allergens, muscle quality, and liver." Frontiers in Physiology 9 (2018): https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.01844. [CrossRef]

- Teles, A., L. Guzmán-Villanueva, M. A. Hernández-de Dios, M. Maldonado-García and D. Tovar-Ramírez. "Taurine enhances antioxidant enzyme activity and immune response in seriola rivoliana juveniles after lipopolysaccharide injection." (2024).

- Hoyles, L., M. L. Jiménez-Pranteda, J. Chilloux, F. Brial, A. Myridakis, T. Aranias, C. Magnan, G. R. Gibson, J. D. Sanderson, J. K. Nicholson, et al. "Metabolic retroconversion of trimethylamine n-oxide and the gut microbiota." Microbiome 6 (2018): 73. 10.1186/s40168-018-0461-0. [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L., G. Annunziata, G. Muscogiuri, C. Di Somma, D. Laudisio, M. Maisto, G. de Alteriis, G. C. Tenore, A. Colao and S. Savastano. "Trimethylamine-n-oxide (tmao) as novel potential biomarker of early predictors of metabolic syndrome." Nutrients 10 (2018): <Go to ISI>://WOS:000455073200152. [CrossRef]

- Farmer, N., C. A. Gutierrez-Huerta, B. S. Turner, V. M. Mitchell, B. S. Collins, Y. Baumer, G. R. Wallen and T. M. Powell-Wiley. "Neighborhood environment associates with trimethylamine-n-oxide (tmao) as a cardiovascular risk marker." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (2021): <Go to ISI>://WOS:000644149700001. [CrossRef]

- Sampath, W. W. H. A., R. M. D. S. Rathnayake, M. Yang, W. Zhang and K. Mai. "Roles of dietary taurine in fish nutrition." Marine Life Science & Technology 2 (2020): 360-75. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000649454300005. [CrossRef]

- Grigorakis, K., K. D. A. Taylor and M. N. Alexis. "Seasonal patterns of spoilage of ice-stored cultured gilthead sea bream (sparus aurata)." Food Chemistry 81 (2003): 263-68. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308814602004211. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).