Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

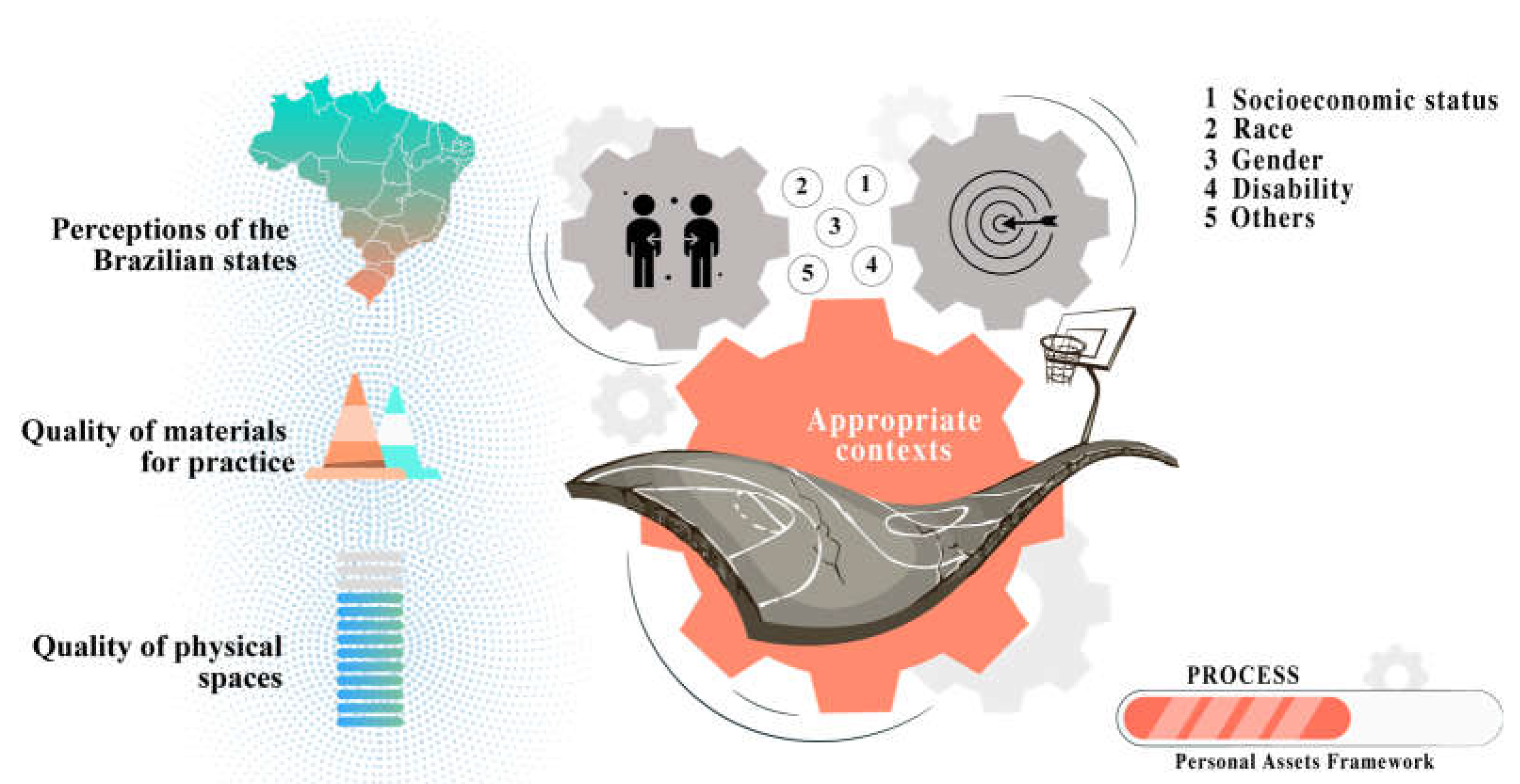

The characteristics of the physical environment where the main sports experiences are experienced are decisive for achieving positive results in sports. The objective of this article was to verify the quality of the facilities and materials for practicing basketball during the formative years. A mixed-method study with a sequential explanatory design was conducted. Quantitative data were collected from Brazilian athletes aged 18 and 19 (n = 141), and then interviews were conducted with 24 athletes. To discover the differences between age groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, and the association between qualitative variables was analyzed using the Chi2 test. The analysis of qualitative data was guided by Thematic Analysis. The results showed that public and private gyms were the most frequented places for practicing basketball, with private gyms being considered better in terms of structure and materials. The athletes' perception of the broader structure of the sports system in the different Brazilian states demonstrated the influence that certain contexts and cultures, more specifically structural and social characteristics, have on sports development. This study demonstrates that options for accessing and remaining in sport are directly influenced by factors such as the geographic location of athletes and their families.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

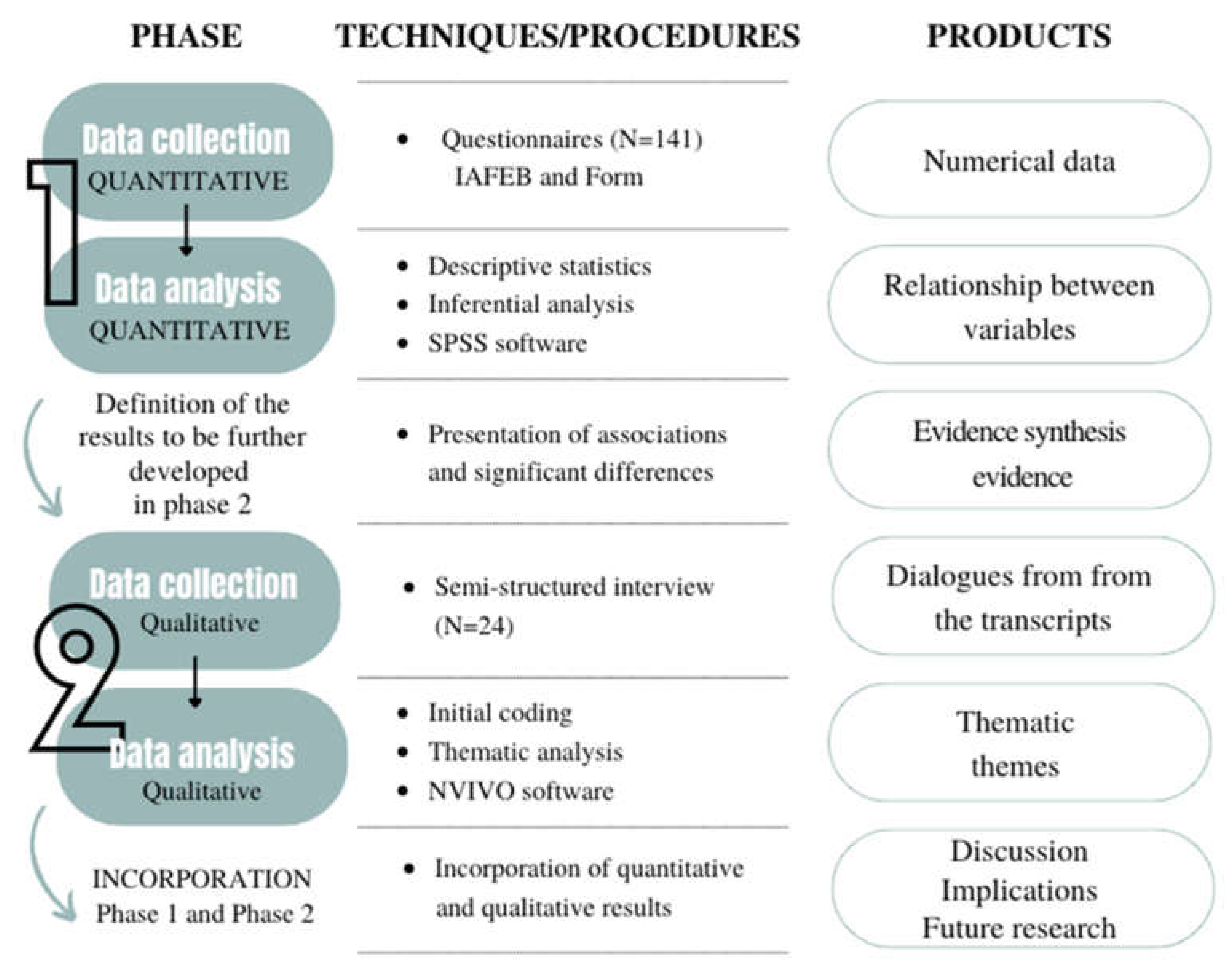

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative stage (Phase 1)

2.2. Qualitative stage (Phase 2)

3. Results

“At the core, the court was open. It wasn't the best option for us to train, but as it wasn't anything serious, we could train calmly; there was a normal table, the balls weren't the best quality, but we could train normally [...]”(Athlete 16, 2022).

“[...] it was a cement court. I remember to this day; I was 11 years old when I said to my coach 'we train on a pigeon poo court', we had to clean the court, clean the balls, and then we played on a court where we had to set up all the timers, set up the scoreboard because it was a rented court. [...]”(Athlete 8, 2022).

“The [name of the club] was the best, the gym is gigantic, full of courts, a gym full of equipment, the biggest structure I've ever seen, that I've ever trained in. There were four courts there so you could train basketball, shoot [...]”(Athlete 33, 2022).

“The structure was much better, much better than the others in terms of courts; the balls were very well preserved. The tables were maintained almost every month, so they were always good for training. We had a gym available, a fitness coach for pre-training warm-ups, as well as tactical and technical training. So it was a much better structure than the others”(Athlete 32, 2022).

“[...] in the beginning, it was those plastic penalty balls, the place was great, the floor was wooden, but we never had help with materials, it was a basket that tore, only the rim was left, the ball was full of pitombo [...]”.(Athlete 54, 2022).

“[...] what was scarcer were the balls, but the rest of the materials we found a way to get, like cones, rope, things like that.”(Athlete 107, 2022).

“As it was the club's subsidiary, it was much better financially, they had much more reinforced equipment, the ball was already made of leather, there was a pump, they had those cones to make the sinuosa [...]”(Athlete 54, 2022).

“[...] it was another world, we got there, and the first thing we saw in the gym was the wooden court, apart from the club which was huge, it was another planet for us [...] in 2018, it was the year I saw the difference between playing in a social project and playing in a club [...]”(Athlete 129, 2022).

“[...] The equipment was enough, obviously for me it could be improved a lot, even the fact that sometimes there was no court to train on or we went to train at a very bad time, so there were conditions, there were things that favored being good, but sometimes it wasn't so perfect. However, it was enough to get started”(Athlete 19, 2002).

“When it rained a lot, we didn't come, but when it rained and stopped, we were able to train even when the court was wet, when the weather was closed, we risked it, but when it rained a lot, he [the coach] gave us an online training session to train at home” [...](Athlete 107,2002).

“[...] The [name of the club] is totally different from the [name of the project]; it's another world! It's a fantastic club, structure-wise, you have a court all day, you have a wonderful gym inside the club, you have physiotherapy inside the club, you have everything [...]”(Athlete 102, 2022).

“Wow, it was very good, because they received all the investment from the government, the courts were very good, every week a new ball arrived, a sensational gym, even more so now that the club has been renovated, but the gym has always been very good, the court is one of the best in [name of city], even the professional volleyball game takes place there [...]”(Athlete 129, 2022).

“Apart from soccer, you have to show that this sport is good for people to want it. Here only schools play, teams that have money and are basketball fanatics”(Athlete 64 - Amazonas/AM, 2022).

“Basketball should improve a lot here, basketball is very undervalued here in Maranhão [...]”(Athlete 46 - Maranhão/MA, 2022).

“[...] here it's one team per city, but not every city competes because there's no money to travel, there's no investment from the city itself, they don't release the bus, sometimes even the city's court is very bad and there's no way to hold a championship there or anything like that. And it ended up being very limited to Salvador and then when you see, of the seven teams there are, six are from Salvador”(Athlete 129 - Bahia/BA, 2022).

“[...] the good thing about the state of Paraná is that it encourages athletes a lot, just because you've been called up [to the state or national team] is already your merit, you've already won a scholarship. If you make the national team, it's another level; if you get a medal, it's another level; participating in a national championship is even more important [...]”(Athlete 8 - Paraná/PR, 2022).

“[...] here in Santa Catarina [name of city] it helps a lot, there's a lot of encouragement from the town hall, they encourage us a lot in sport”(Athlete 90 - Santa Catarina/SC, 2022).

“[...] this is true for any sport, the showcase of sport is usually Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Santa Catarina, usually the showcase of sport is these three, and there's no way you can play professionally in Mato Grosso, for example”(Athlete 120 - Santa Catarina/SC, 2022).

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and practical applications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira, A.P. Preparar talentos para o alto nível: um contraste entre “o que se sabe” e o “que se faz” na zona Euroace. In Nuevas tendencias para el impulso del talento desportivo; Ibáñez, S.J., Medina, A.A., Molina, S.F., Eds.; Wanceulen: Sevilha, 2021; pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Coakley, J. Positive youth development through sport: myths, beliefs, and realities. In Positive Youth Development through Sport, 2nd ed.; ; Holt, N.L., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, 2016; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Sport and Social Class . Social Sci. Inf. 1978, 17, 819–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Turnnidge, J.; Murata, A. Youth sport research: describing the integrated dynamic elements of the personal assets framework. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2020, 51, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Murata, A.; Martin, L.J. The personal and social development of children in sport. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Social Development; Smith, P.K., Hart, C.H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken, 2022; pp. 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folle, A.; Nascimento, J.V.; Souza, E.R.; Galatti, L.R.; Graça, A. Female basketball athlete development environment: proposed guidelines and success factors. Educ. Fís. Ciencia 2017, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Galatti, L.R.; Marques, R.; Barros, C.E.; Paes, R.R. Excellence in women basketball: Sport career development of world champions and Olympic medalists Brazilian athletes. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2019, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Galatti, L.R.; Marques Filho, C.V.; Santos, Y.Y.S.; Watoniki, G.; Korkasas, P.; Mercadante, L.A. Trajetória no basquetebol e perfil sociodemográfico de atletas brasileiras ao longo da carreira: um estudo com a liga de basquete feminino. Movimento 2021, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, L.F.P.; Beirith, M.K.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Galatti, L.R.; Farias, G.O.; Folle, A. Personal engagement of basketball athletes: Insights from mixed methods research. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2024, 24, 1795–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, C.; Folle, A.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Nascimento, J.V. Practice context on sport development of elite Brazilian volleyball athletes. J. Phys. Educ. 2021, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.A.; Reverdito, R.S.; Folle, A.; Subjana, C.L.; Galatti, L.R. Excelência no Handebol: o processo de desenvolvimento esportivo de atletas brasileiras campeãs do mundo. Quad. Psicol. 2022, 24, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.A.; Reverdito, R.S.; Scaglia, A.J. Engagement in athletic career: a study of female Brazilian handball world champions. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching 2022, 0, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, R.B.; Vicentini, L.; Marques, R.F.R. Brazilian women elite futsal players’ career development: diversified experiences and late sport specialization. Motriz 2019, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinha, G.; Oliveira, R.; Gonçalves, L.J. Contextual factors influencing young athletes’ decision to do physical activity and choose a sports’ club: the case of Portugal. Healthcare 2022, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beneli, L.M.; Galatti, L.R.; Montagner, P.C. Analysis of social-sportive characteristics of Brazil women’s national basketball team players. Rev. Psicol Deporte 2017, 26, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, D.L.; Fraiha, G.A.L.; Darido, S.C.; Pérez, B.L.; Galatti, L.R. Trayectoria de los jugadores de baloncesto del nuevo baloncesto Brasil. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2017, 17, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, E.C.; Annerstedt, C.; Dohsten, J. “The individual at the centre” - a grounded theory explaining how sport clubs retain young adults. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 2017, 12, 1361782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Human Nature and Conduct: An Introduction to Social Psychology; Henry Holt: New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, S.J.; Pérez-Goye, E.; García-Rubio, J.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Effects of task constraints on training workload in elite women’s soccer. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching 2019, 15, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, C.; Nascimento, J.V.; Folle, A.; Ibáñez, S.J. Construcción y validación de un instrumento para el análisis de la formación deportiva en voleibol. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2019, 19, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, J.; Turnnidge, J.; Vierimaa, M. A personal assets approach to youth sport. In Routledge Handbook of Youth Sport; Routledge: London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McCrudden, M.T.; McTigue, E.M. Implementing integration in an explanatory sequential mixed methods study of belief bias about climate change with high school students. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2019, 13, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descombe, M. Communities of practice: a research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2008, 2, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; McGannon, K.R. Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Ex Psychol, 2018, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, S.S.; Silva, A.M.; Santos, L.M.S.; Sousa, B.V.N.; Oliveira, E.F. Práticas de atividade física e esporte no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Promoc. Saúde 2019, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, L.F.P.; Folle, A.; Flach, M.C.; Silva, S.C.; Silva, W.R.; Beirith, M.K.; Collet, C. The relative age effect on athletes of the Santa Catarina Basketball Federation. Montenegro J. Sports Sci. Med. 2022, 11, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spaces | Quality | < 10 years | 11 to 14 | 15 to 17 | 18 to 19 | Chi2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Places | Very low | 22 | 20% | 16 | 15% | 1 | 9% | 8 | 11% | x²=9.654 p=0.646 |

| Low | 25 | 23% | 21 | 19% | 1 | 9% | 16 | 22% | ||

| Moderate | 42 | 39% | 44 | 40% | 7 | 64% | 36 | 49% | ||

| High | 14 | 13% | 17 | 16% | 1 | 9% | 8 | 11% | ||

| Very high | 5 | 5% | 11 | 10% | 1 | 9% | 5 | 7% | ||

| Public Gym | Very low | 11 | 11% | 12 | 11% | 2 | 13% | 15 | 22% | x²=25.918 p=0.014 |

| Low | 18 | 18% | 15 | 14% | 2 | 13% | 12 | 17% | ||

| Moderate | 51 | 50% | 48 | 46% | 1 | 7% | 21 | 30% | ||

| High | 16 | 16% | 17 | 16% | 8 | 53% | 15 | 22% | ||

| Very high | 6 | 6% | 12 | 11% | 2 | 13% | 6 | 9% | ||

| Private Gym | Very low | 16 | 14% | 8 | 6% | 1 | 3% | 9 | 10% | x²=43.920 p<0.001 |

| Low | 10 | 9% | 4 | 3% | 1 | 3% | 6 | 7% | ||

| Moderate | 15 | 14% | 11 | 9% | 6 | 18% | 22 | 26% | ||

| High | 46 | 42% | 41 | 32% | 18 | 53% | 20 | 23% | ||

| Very high | 23 | 21% | 63 | 50% | 8 | 23% | 29 | 34% | ||

| School | Very low | 24 | 24% | 21 | 19% | 3 | 25% | 14 | 19% | x²=19.502 p=0.077 |

| Low | 24 | 24% | 13 | 12% | 1 | 8% | 6 | 8% | ||

| Moderate | 31 | 31% | 36 | 33% | 6 | 50% | 24 | 33% | ||

| High | 17 | 17% | 30 | 27% | 1 | 8% | 19 | 26% | ||

| Very high | 4 | 4% | 9 | 8% | 1 | 8% | 10 | 14% | ||

| Another location | Very low | 22 | 37% | 22 | 35% | 0 | 0% | 16 | 36% | x²=17.359 p=0.137 |

| Low | 16 | 27% | 7 | 11% | 1 | 25% | 5 | 11% | ||

| Moderate | 18 | 30% | 19 | 30% | 3 | 75% | 16 | 36% | ||

| High | 2 | 3% | 8 | 13% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 11% | ||

| Very high | 1 | 2% | 6 | 10% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 4% | ||

| Materials | Quality | < 10 years | 11 to 14 | 15 to 17 | 18 to 19 | Chi2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balls, cones, tables | Very low | 3 | 2% | 2 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 2% | x²=139.85 p<0.001 |

| Low | 14 | 10% | 8 | 6% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 2% | ||

| Moderate | 61 | 44% | 17 | 12% | 4 | 10% | 43 | 44% | ||

| High | 41 | 30% | 43 | 31% | 34 | 89% | 13 | 13% | ||

| Very high | 18 | 13% | 69 | 50% | 0 | 0% | 38 | 39% | ||

| Uniforms,vests | Very low | 10 | 7% | 8 | 6% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 3% | x²=192.31 p<0.001 |

| Low | 23 | 17% | 3 | 2% | 0 | 0% | 7 | 7% | ||

| Moderate | 51 | 37% | 16 | 11% | 0 | 0% | 49 | 50% | ||

| High | 38 | 28% | 44 | 32% | 38 | 100% | 9 | 9.2% | ||

| Very high | 15 | 11% | 68 | 49% | 0 | 0% | 30 | 31% | ||

| Variable | Quality | < 10 years | 11 to 14 | 15 to 17 | 18 to 19 | Chi2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influence of location and materials | Very negative | 3 | 2% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | x²=648.58 p<0.001 |

| Negative | 0 | 0% | 9 | 6% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Indifferent | 124 | 90% | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1% | ||

| Positive | 0 | 0% | 21 | 15% | 38 | 100% | 97 | 99% | ||

| Very positive | 10 | 7% | 108 | 78% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).