1. Introduction

Reducing energy consumption in the production of construction materials is a critical issue in the context of sustainable construction [

1,

2,

3]. Switching to self-compacting concrete (SCC) technologies in the production of reinforced concrete structures is strongly recommended to significantly lower energy costs. For this purpose, SCC compositions have been developed using local raw materials. The influence of individual concrete components and their interactions on the formation of concrete properties has been studied. Concrete with reduced binder content and average strength indicators was successfully produced [

4,

5,

6,

7].

The technological and operational advantages of SCC are well-documented. These include the production of highly functional concretes, including high-strength concretes; the potential for enhancing advanced technologies to manufacture new high-performance precast reinforced concrete elements with smaller cross-sections; the emergence of innovative materials tailored to meet the needs of modern architecture; and the ability to ensure high product quality, including textured surfaces [

8,

9,

10,

11].

2. Materials and Methods

One of the most important factors in the efficient use of self-compacting concrete (SCC) for sustainable construction is its ability to reduce energy consumption in the production of materials. SCC eliminates the need for heat and moisture treatment, as well as mechanical compaction of the concrete mix, particularly vibration compaction. Additionally, an essential prerequisite for the effective use of SCC is the reliance on local raw materials. This not only avoids the transportation of raw materials over long distances—reducing the environmental impact—but also lowers fuel and lubricant consumption for vehicles, and, consequently, energy resources [

12,

13].

Compared to other methods, the use of SCC with average strength in reinforced concrete construction technologies allows for a reduction in cement consumption, which is itself a highly energy-intensive material.

In the Republic of Kazakhstan, SCC has not been widely used until now. This is partly due to a lack of knowledge about the material, insufficient regulatory documentation, and underdevelopment of SCC compositions based on local raw materials. However, Kazakhstan has gained some unique experience with SCC for monolithic construction. For example, NIIStroyProekt LLC and BI-Group are jointly developing and testing SCC at construction sites in Astana [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Currently, there is growing interest in the use of SCC in Kazakhstan. Several enterprises in the Republic produce precast reinforced concrete structures. At the request of Kazakh Leading Academy of Architecture and Civil Engineering, JSC Remstroytekhnika has conducted scientific and experimental work to select SCC compositions aimed at reducing production energy costs. SCC based on local raw materials is now being used in the production of composite reinforced concrete floor slabs.

3. Results and Discussion

As a result of the study, self-compacting concrete (SCC) demonstrated a strength class of B30, a concrete mix viscosity class of BC2/VF1 (25 seconds), and a mobility class of SF2 (63 cm). The raw materials used included Portland cement PK M500 from JSC "Buktarma Cement Company," gravel (5–10 mm fraction) from effusive and intrusive igneous rocks of the Baltabay-1 quarry, sand (2.5–5 mm fraction), fine sand mineral fillers, the superplasticizer Master Glenium 977, and the hardening accelerator Master X-SEED 100 supplied by JSC "BASF Central Asia." The selection of raw materials was guided by the availability of local sources.

The study was complicated by the challenge of utilizing widely available ash and slag due to specific limitations in the local raw material base. In Kazakhstan, SCC remains under-researched, partly because of the transition of all thermal power plants in Almaty to gas, which has reduced the availability of ash. The use of zeolite (specific surface area of 1800 cm²/g) from the Shangkanai deposit and stone flour (specific surface area of 1900 cm²/g) obtained from filter gravel was investigated as alternative fillers. While the use of fillers from igneous rocks and zeolite as modifiers for high-performance concrete has shown potential, their application in SCC is still underexplored, with some contradictory experimental results reported [

20].

Research conducted at the Kazakh Leading Academy of Architecture and Civil Engineering demonstrated the efficiency of using local natural zeolites, characterized by a high clinoptilolitecontent, and stone flour derived from stone crusher filters as fillers in SCC. The gravel used originated from acid rocks containing amorphous and crystallized silicon dioxide. The combined introduction of mineral additives with such a mineralogical composition reduced the binder content while achieving the required rheology and ensuring homogeneity and strength of the concrete properties.

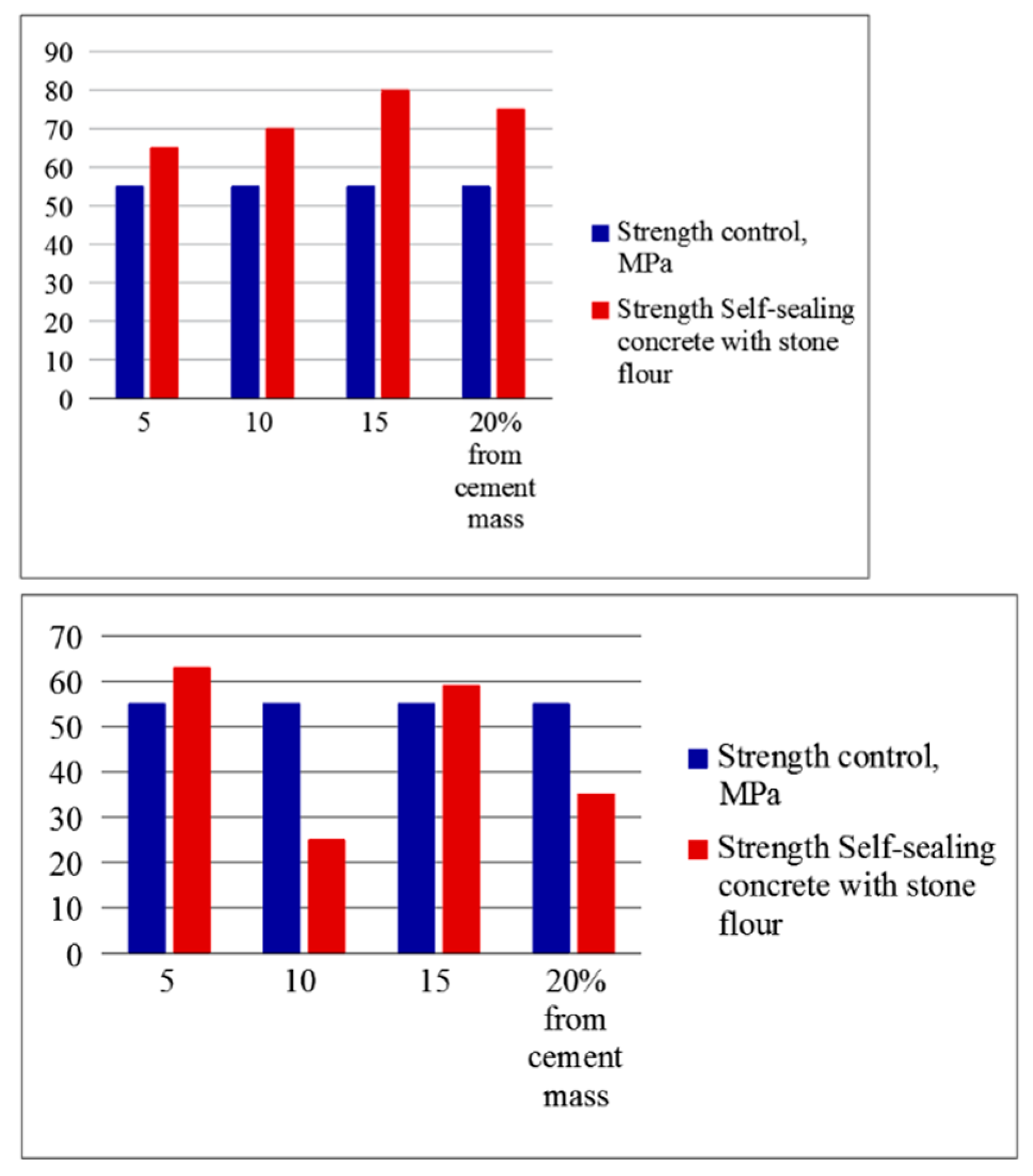

The experiments confirmed that stone flour exhibits high rheological capacity due to its inertness to water, which minimizes resistance during gravitational distribution. The optimal dosage was determined to be 15% stone flour, which increased the concrete strength by 50% when replacing 20–40% of the cement with stone flour. However, insufficient viscosity in the finely dispersed system caused sedimentation (

Figure 1a). Zeolite, when introduced at an optimal content of 7%, provided high stabilizing and binding properties, increasing concrete strength by 55% (

Figure 1b).

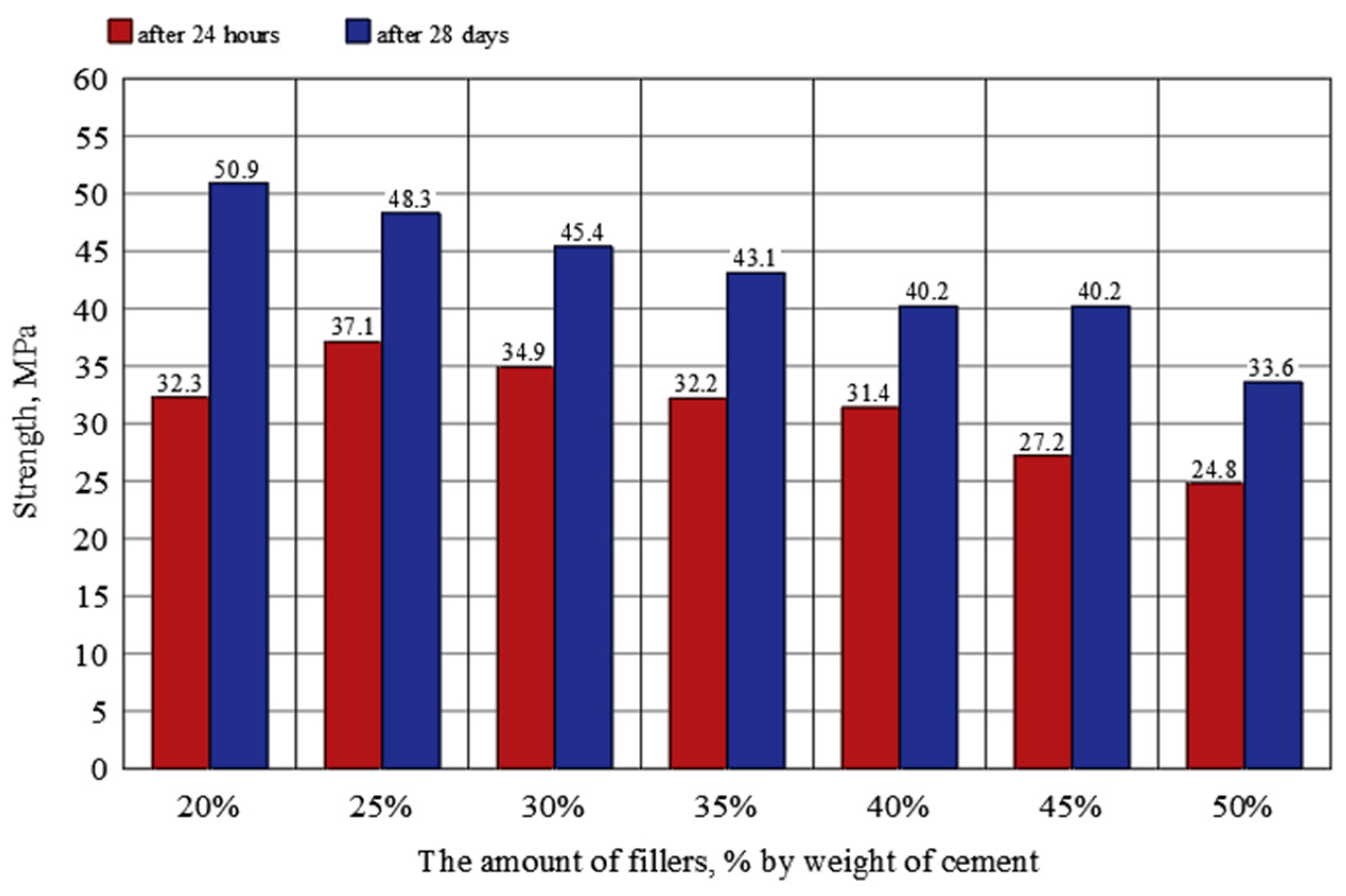

It should also be noted that the required strength indicators are achieved with a relatively low binder content: 320–360 kg of cement is required per cubic meter of concrete. For comparison, switching to modern free-forming technologies can result in cement consumption of up to 450 kg per cubic meter.Without relying on heat treatment, one of the primary objectives in developing the concrete composition using factory technology—accelerating strength gain—was achieved by using high-quality cement PC M500 DO and the hardening accelerator Master X-SEED 100. The accelerator is based on a plasticizer and synthetic C-S-H crystals. Additionally, experiments revealed that the specific mineralogical composition of stone flour and zeolite contributes to significantly extending the initial setting time and overall hardening time of cement, potentially doubling these durations (

Figure 2).

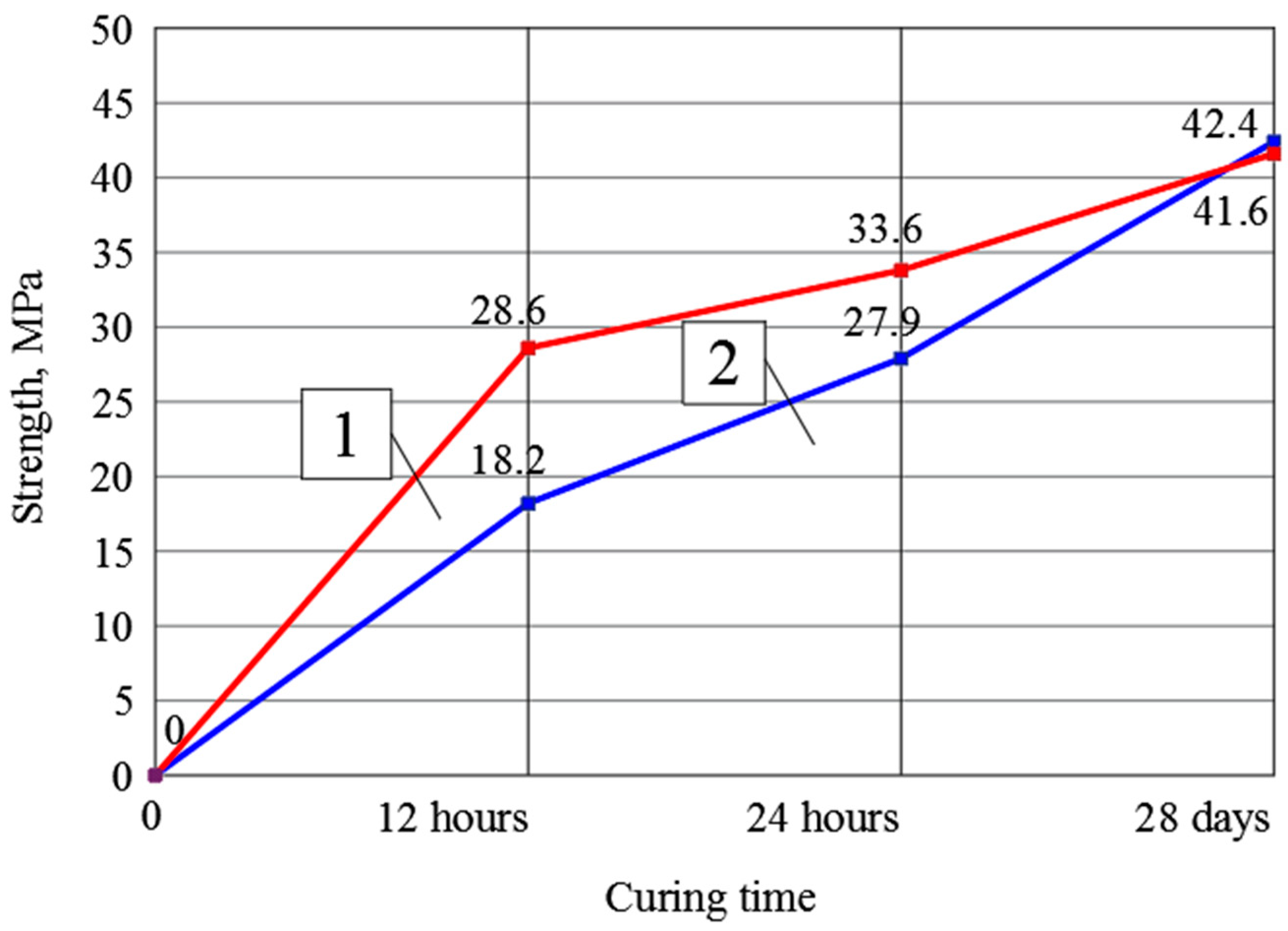

The period of heat treatment of reinforced concrete floor slabs at the enterprise is 12 hours. For the same composition of SCC, the hardening strength needed for floor slab production is 70% within 22–24 h under natural curing (

Figure 3). Such processing time is necessary to achieve the level of productivity that is required. Excluding thermal and wet treatment has other advantages, especially for the concrete’s durability. There is evidence that the improvement of the concrete strength under thermal treatment tends to slow down and even almost stop, while natural curing contributes to the continuous kinetic increase of the strength characteristics of concrete.

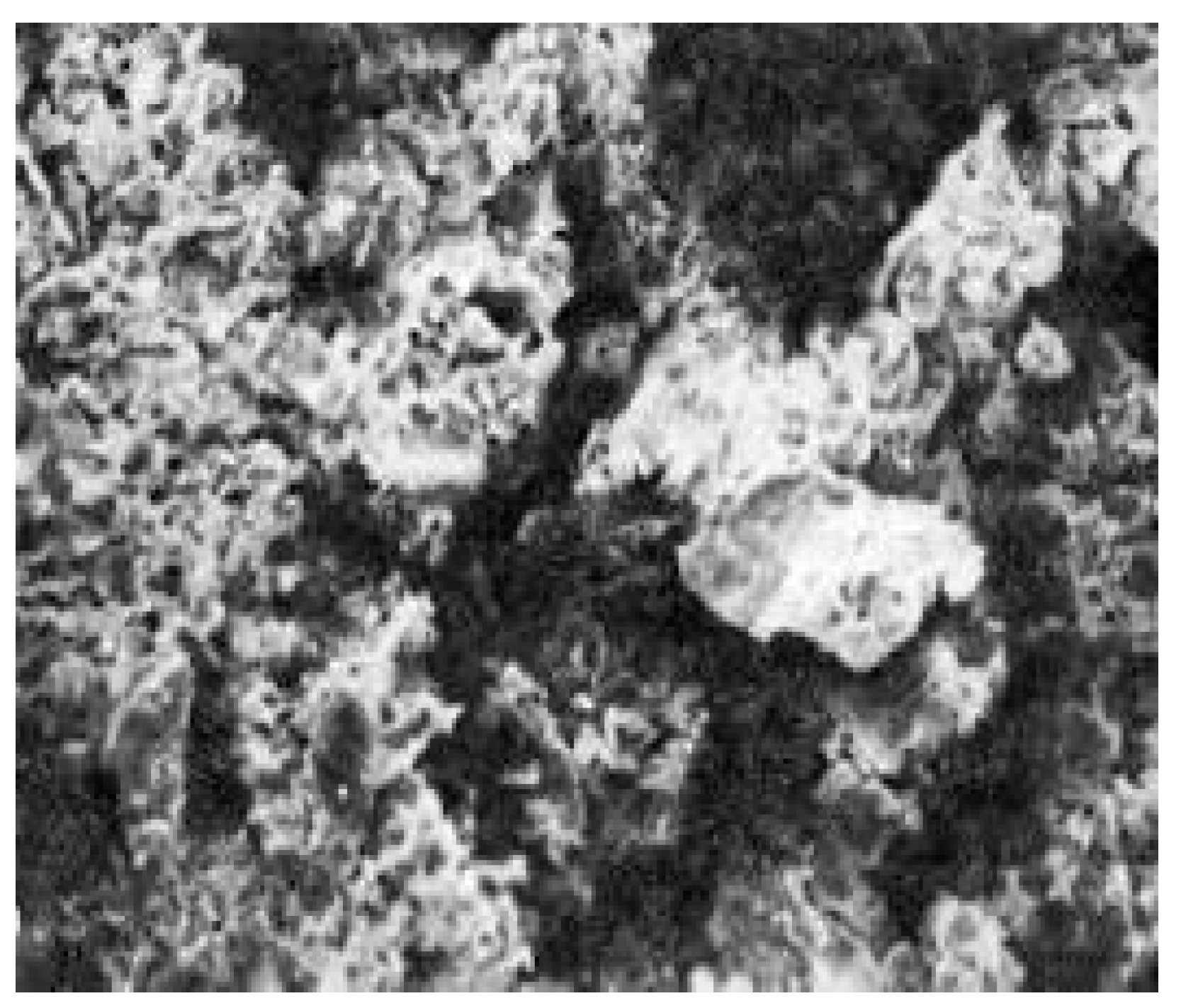

The microstructural analysis of the obtained concrete revealed changes in the morphology of the crystal hydrates formed during cement hardening, as well as the fixation of capillary pores with newly formed structures. These structural changes are attributed to the incorporation of active fillers and natural curing conditions, which contribute to improved strength and density of the concrete (

Figure 4).

The efficiency of utilizing the developed self-compacting concrete (SCC) in floor slab production is confirmed by analyzing the energy consumption of the plant’s existing technology. Under the current process, energy costs for the production and sale of 1 m³ of concrete range from approximately 85 to 160 kWh/m³. Of this, about 6–10% is attributed to heat and moisture treatment, and 0.5–0.8% to the compaction of the concrete mix.

Electricity consumption for heat and moisture treatment of reinforced concrete slabs in a steam chamber for 8–12 hours ranges from 1200 to 2000 kW. Additionally, vibration compaction of 30–35 slabs (including backfill and steam chamber operations) requires approximately 66.5 kW. Therefore, eliminating heat treatment and compaction from the slab production process leads to significant energy savings.

5. Conclusions

The transition to SCC technology in reinforced concrete slab production makes it possible to produce structures with enhanced performance characteristics, decrease direct energy costs at the enterprise by 20–25% and reduce overall energy consumption. The decrease in the utilization of energy-intensive Portland cement is realized through the utilization of locally available raw materials to reduce on the transportation of resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization D.G. and N.S.; Methodology: D.G. and N.S.; Software: D.G. and G.Zh.; Visualization: G.Zh.; Validation: D.G. and N.S.; Formal analysis: D.G.; Investigation: D.G., N.S. and G.Zh.; Resources: D.G.; Data curation: S.Zh. and M.R.; Writing—original draft preparation: S.Zh. and M.R.; Writing—review and editing: S.Zh. and M.R.; Supervision: S.Zh. and M.R.; Project administration: S.Zh. and M.R.; Funding acquisition: S.Zh. and M.R.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding was provided by the West Kazakhstan Agrarian and Technical University named after Zhangir khan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCC |

Self-compacting concrete |

| NIIStroyProekt |

Research Institute of Building Materials and Design |

References

- N.Krishna Murthy, A.V.NarasimhaRao, I.V.Ramana Reddy Comparison of cost analysis between self-compacting concrete and normal vibrated concrete // International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET), Volume 5. – 20147 – P. 34-41.

- Seo J., Torres E., Schaffe W. Self-Consolidating Concrete for Prestressed Bridge Girders // WisDOT ID no. 0092-15-037 – 2017. P. 181.

- Cazacu N., Bradu A., Florea N7 Self-compacting concrete in building industry // UniversitateaTehnică"GheorgheAsachi" din LașiVolumul 62 (66), № 1. – 2016. – P.85-94.

- Chang Seon Shona, Young Su Kim Evaluation of West Texas natural zeolite as an alternative of ASTM Class F fly ash //Construction and Building Materials. – 2013. – №47. – Р. 389-396. [CrossRef]

- Lankin C.V. Features of the strength of concrete filled with zeolites //Problems of ecology of the Upper Amur region. - 2014. – No. 14. – pp. 10-17.

- Kunecki P., Panek R., Kotejac A., Franus W. Influence of the reaction time on the crystal structure of Na-P1 zeolite obtained from coal fly ash microspheres //Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. – 2018. – №266. – P. 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Mahoutian M., Shekarchi M. Effect of inert and pozzolanic materials on flow and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete //Journal of Materials. – 2015. – P. 11-33. [CrossRef]

- Wen Chaokai, Chen Jing, Liu Qibin Research on influence of zeolite powder on internal humidity and autogenous shrinkage of self-compacting concrete //2nd International Conference on Advances in Materials, Mechatronics and Civil Engineering. – 2017. – Р. 195-200. [CrossRef]

- Bernardo L., Joejie J., Jewill D., Ramon C., Lance R. Effects of pernaviridis and zeolite on the properties of self-compacting concrete //Presented at the DLSU Research Congress De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines June 20 to 22, 2018.

- SamimiК., Bernard S. Microstructure, compressive strength and transport properties of high strength self-compacting concretes containing natural pumice and zeolite //International Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering. – 2018. – №3 (12). – P. 227-236.

- Robert C., Tydlutat V. Early-stage hydration heat development in blended cements containing natural zeolite studied by isothermal calorimetry //ThermochimicaActaVolume 582, 20 April 2014. – P. 53-58. [CrossRef]

- Bohac M., Kubatova D., Necas R. Properties of cement pastes with zeolite during early stage of hydration //Procedia Engineering. – 2016. – №151. – Р. 2-9. [CrossRef]

- Bychkov M.V., Self-sealing concretes of reduced density using volcanic tuff // Engineering Bulletin of the Don. - 2013. - No. 3(26.. p.;

- Smirnov S.I., Features of self-sealing concrete in the construction of unique buildings and structures // Dissertation.- 2015. – p.16.;

- Kalashnikov V. I., Calculation of compositions of high-strength self-sealing concretes / / Building materials. - 2008. – No. 10. – pp. 4-6.;

- Polyakov D. M., Koval S. V., Starsky M. M., Tsiak M. M. designing self-compacting concretes / / Bulletin of the Odessa State Academy of construction of architecture. 2008, No. 31, pp. 287-294.

- Khalyushev, A. K. optimization of the composition of composite Cements with mineral additives based on industrial waste. scientific works "resource-efficient materials, structures, buildings and structures". - Exactly: Vidvo NUVGP. - 2008. - Issue 16 (Part 1.. - P.103-110.

- Development of self-compacting concrete using stone crushing residues of Panikin D.A. / Messenger of the Donbass National Academy of Construction and Architecture. 2015. №3(113). 38-42 pages.

- Effects of shredding and removal of mineral filler on the characteristics of self-pressing concretes of small granules kastornykh L.I., Taroyan A.G., Usepian L.M. / Engineering messenger of Don. 2017. № 3 (46). B. 107.

- Temirova, A.M., Tuktin, B.T., Omarova, A.A. et al. Conversion of Light Hydrocarbons on Modified Zeolite Catalysts. Theor Found Chem Eng 56, 892–899 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0040579522310037. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).