Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of disability worldwide, and its sequela, hemiparesis, significantly limits patients’ activities of daily living (ADL) and reduces their quality of life (QOL) [

1]. Recently, innovative therapies have been developed to restore upper limb function in patients with post-stroke hemiparesis [

2,

3]. These approaches are based on the neurophysiological basis of use-dependent plasticity, which strengthens the central nervous circuitry and restores function through repeated activation of specific neurons [

4]. Based on this principle, active and continuous use of the paretic upper extremity is essential for patients to regain upper extremity function [

5]. To promote effective use of the upper limb, it is necessary to provide tasks that are appropriate for the severity of the patient’s disability, avoid frustrating the patient by setting relatively high difficulty level, and prevent inadequate stimulation by setting a significantly low difficulty level. Therefore, an accurate and detailed assessment of bilateral upper extremity use in daily life is essential [

6]. The clinically used upper extremity functional assessment evaluates individualized joint range of motion, muscle power, isolated movement, coordination, and dexterity and subsequently measures the combined movement ability of these elements in combination. Additionally, the degree of dysfunction of the patient’s paretic upper limb is quantified by comparing it to the non-paretic side [

7]. The Fugl–Meyer Assessment (FMA) evaluates motor separation and coordination, and the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) assesses the ability to grasp and manipulate objects [

8]. These assessments accurately determine the degree to which the paretic upper limb compared to the non-paretic limb retains function. This comparison is important, not only to determine the degree of disability but also to predict the potential for the efficient use of the bilateral upper limbs in ADL. For example, shoulder abduction and hand extension movements on the paretic side has been shown to be predictive of bimanual movement recovery in ADL [

9]. Accurate assessment of disability can also identify the pattern of compensatory movements performed by the patient. The excessive use of shoulder abduction movements to reach a target object to compensate for elbow extension movements is usually observed in patients with post-stroke hemiparesis [

10]. These observations provide valuable information for targeting rehabilitation therapy. Therefore, obtaining accurate understanding of the functional differences between the paretic and non-paretic sides based on upper limb functional assessment results and predicting the efficiency of both upper limbs use in ADL are essential for developing individualized rehabilitation treatment strategies.

Several studies have used motor time as a parameter to differentiate between paretic and non-paretic sides and gauge the severity of motor impairments in patients with stroke [

11,

12]. For example, research has shown that increased motor time on the affected side is correlated with greater impairment, as measured by traditional clinical scales, such as the Fugl–Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity (FMA-UE) [

13,

14]. However, many of these approaches rely on gross motor tasks that may not capture subtle differences in dexterity and fine motor control. The coordination subtest of the FMA-UE compares the time spent in repetitive elbow flexion and extension movements between the paretic and non-paretic sides, whereas a difference in movement time of <2 s is a full score that limits the assessment of functional changes in joint movement speed and coordination in patients with mild hemiparesis [

15]. ARAT specifies a scoring method where points are deducted if completing a movement on the paraplegic side takes abnormally long compared to the non-paraplegic side; however, no clear cut point exists for the movement time that would be deducted for each subtest [

16]. The FMA-UE and ARAT are assessment methods with established reliability and validity, although they produce ceiling effects, limiting their utility for patients with mild hemiparesis [

17,

18]. Furthermore, the Box and Block Test is a simple assessment that measures the number of blocks carried in 1 min and focuses on the difference in results between the paretic and non-paretic sides but does not assess the qualitative aspects of movement [

19]. The Motor Activity Log and the Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living (JASMID) have been used to assess the use of the paraplegic upper limb in ADL [

20,

21]. However, these results may conflict with scores from upper limb function assessment or be invalid for patients with aphasia or cognitive impairment [

22,

23]. These highlight the need for more nuanced, time-based evaluations that can detect fine motor impairments and their impact on daily functioning.

The Southampton Hand Assessment Procedure (SHAP) is recognized for its ability to assess hand function across various impairment levels, including mild hemiparesis, making it a valuable tool in clinical rehabilitation [

24]. Its focus on timing provides a quantitative measure of task performance, which aligns with the demands of everyday activities, such as lifting, carrying, and manipulating objects. Therefore, clinicians can objectively assess improvements in motor function over time while minimizing subjective biases by focusing on the time taken to complete these tasks. The heavy-weight item in SHAP, which involves moving weighted objects, simulates real-world tasks that require both strength and dexterity. Previous studies have suggested that the heavy-weight item of SHAP is the easiest test item to perform with the highest success rate and that its performance time provides an estimate of the FMA-UE score and the paretic upper limb use in ADL [

25]. However, in clinical practice, the challenges are to reduce assessment time and ensure sufficient treatment time, and the SHAP is an upper limb function test with a long assessment time, which makes applying it to patients difficult. If the assessment of movement time on the heavy-weight item of SHAP could be substituted for that of patients’ upper limb function and the use of the paretic side, therapists could perform the assessment more efficiently and spend more time providing treatment to help patients regain their upper limb function.

Therefore, this study aimed to verify the relationship between the motor time obtained by the SHAP heavy-weight item instrument developed to assess upper limb motor function in patients with stroke and the results of other functional assessments to discriminate between the paretic and non-paretic sides as well as estimate upper limb motor function and the use of the upper limb on the paretic side in ADL. This study’s focus on identifying key motor timing differences between the paretic and non-paretic sides could lead to more personalized rehabilitation approaches, allowing clinicians to assess improvements more precisely and modify interventions accordingly. Furthermore, by streamlining the assessment of motor function, this study’s findings may reduce the time required for evaluation, enabling more efficient rehabilitation sessions that maximize recovery outcomes.

Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study. We hypothesized that the motor times obtained during the task of moving the cylinder in patients with post-stroke hemiparesis would be related to the results of other functional assessments, that the measured motor times would allow the determination of patients’ paretic and non-paretic sides, and that the motor time results would provide an estimate of patients’ upper limb motor function and the paretic upper limb use in ADL.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

All patients provided written informed consent to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine (approval number: 22-061-6238).

2.3. Setting

This study was conducted at the Jikei University Hospital. Five occupational therapists working at the hospital and engaged in rehabilitation in the field of cerebrovascular diseases clinically assessed the patients and measured motor tasks. The correlation test of the clinical evaluation was performed among these therapists, which confirms a similar application of the tests. Furthermore, the acquisition of patients’ medical information, clinical evaluation, and measurement of motor tasks began on April 1, 2023 and ended on February 1, 2024.

2.4. Participants

The eligibility criteria for the participants were patients with post-stroke hemiparesis who had undergone occupational therapy at The Jikei University Hospital between April 1, 2023 and February 1, 2024, those aged ≥18 years, and those able to grasp and release a cylinder on a table with the upper limb on the paretic side or hold an end-sitting position independently. In contrast, the exclusion criteria were impaired consciousness, mental or cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination score ≤25) [

26] that could affect the patient’s ability to understand test instructions and perform tasks with a diagnosis of cognitive impairment post-stroke; visual field impairment; patients with motor paralysis or sensory impairment in the bilateral upper limbs; those with central nervous system or orthopedic diseases other than stroke; those with pain in the joints of the upper limbs or fingers during movement; those with marked limitations in the range of motion of the upper limbs; and patients with an amputated upper limb, hand, or fingers. Patients who met the study eligibility criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria were asked to participate in the study, and those who consented were included. The minimum sample size was calculated as 58 patients using G*Power 3.1 (University of Dusseldorf, Dusseldorf, Germany), and the sample size was calculated by setting the test to logistic regression (z test). For calculating the required sample size, the odds ratio was 2.33, the percentage of incidence in the group with factors was 0.5, the percentage of incidence in the group with no factors was 0.3, α was 0.05, power (1-β) was 0.8, and the distribution was log distributed.

2.5. Participant Characteristics

The participants’ basic characteristics and medical information, (including sex, age, height, body weight, body mass index, dominant hand before the stroke, stroke type, post-stroke duration, and paretic side), were obtained from their medical records.

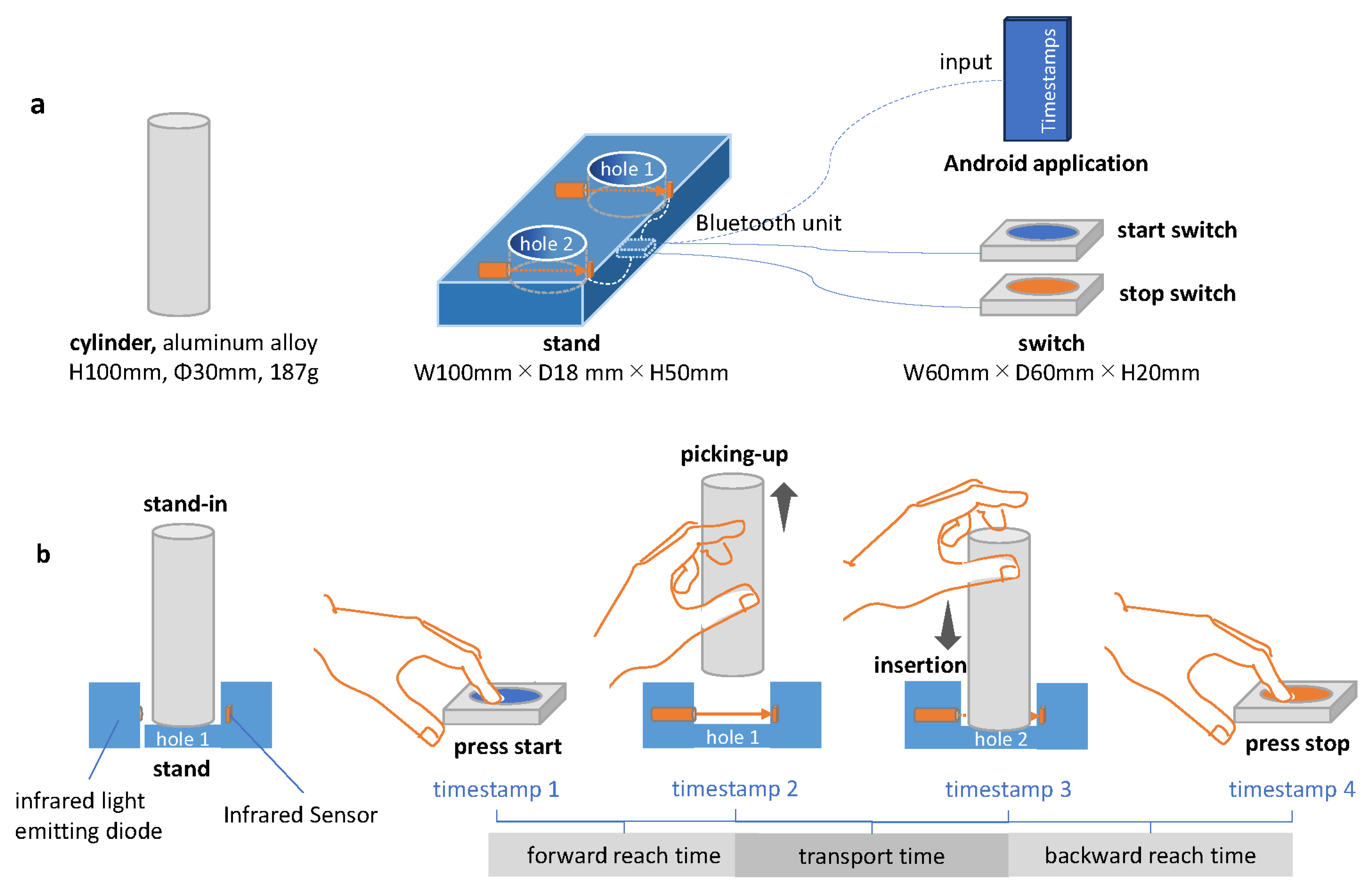

2.6. Measurement Instrument

The motor task was measured using an instrument developed for this study (Inter Reha Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan, 2021), which consists of a cast aluminum cylinder, a stand holes (diameter = 35 mm, depth = 5 mm) in the stand of the cylinder are equipped with an infrared light-emitting diode and sensor. When the cylinder enters or leaves the hole in the stand, the infrared light is received, and a timestamp is automatically recorded in the Android application via Bluetooth. This device can be used to record the intervals from when the competitors press the start button until they lift the cylinder (forward reach time), when the cylinder is transported to another hole until it is placed (transport time), and when the cylinder is placed until the competitors press the end button after the cylinder is placed. The three motor times are recorded as follows: the interval from when the cylinder is placed to when the competitors press the end switch (backward reach time) (

Figure 1-b). Furthermore, the recorded motor time is stored as a CSV file in the internal memory of the Android application paired with the dynamometer after the participants’ IDs and measurement conditions are entered.

2.7. Experimental Procedure

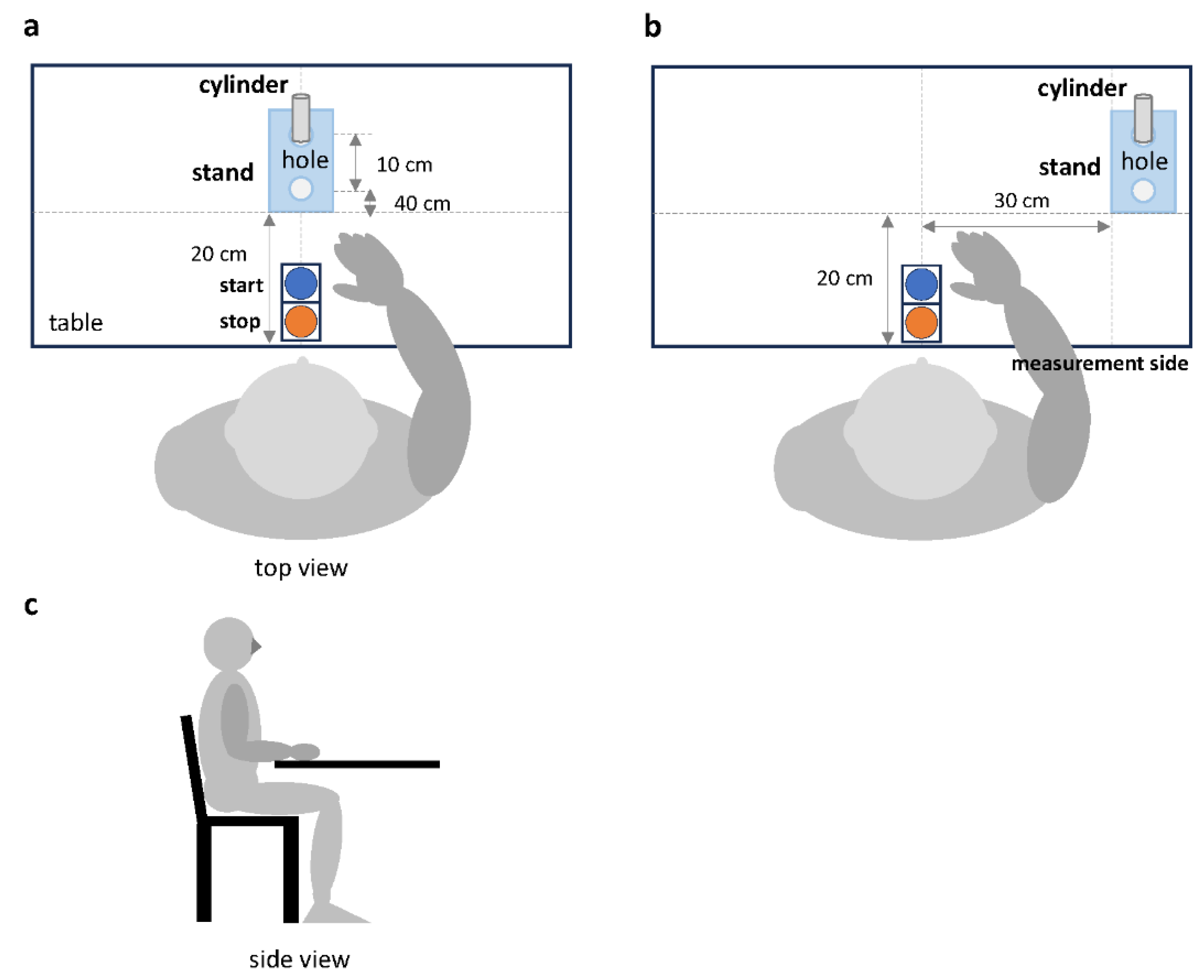

The examiner activated the application program on the cell phone and connected it to the instrument via Bluetooth. Once the connection to the device was established, the cylinder, cylinder stand, and switch were placed in the specified locations. In the condition where the cylinder stand was placed in front of the participant (frontal task), the stand was placed 20 cm away from the bottom edge of the desk (

Figure 2-a). In the condition where it was placed on the ipsilateral side of the upper limb being measured (ipsilateral task), the stand was placed 20 cm away from the bottom edge of the desk and 30 cm away from the midline of the start and stop switches (

Figure 2-b). Next, the stand was placed in a vertical line with two holes, and the cylinder was placed in hole 1 at the back of the stand. The manual switches were placed in front of the participant and aligned with the bottom edge of the table, with the start and end switches at the back and front, respectively. Additionally, the examiner checked the equipment to ensure it was positioned correctly before the measurement began.

The examiner had the participants sit in a chair with a backrest and adjusted the height of the desk so that the flexion angle of the participant’s elbow joint was 90˚. Specifically, the starting position of the measurement was with the participant’s hands on the desk, with the palms of both hands facing down. The examiner demonstrated the exercise task to the participants, instructing them to press the start switch with the examiner’s hand first, to press the end switch after moving the cylinder from hole 1 in the back to hole 2 in the front, and to perform the movement as quickly and error-free as possible. Participants were checked to ensure they understood the instructions given by the examiner. Measurement of the motor task was performed by an occupational therapist trained to understand the operation of the equipment and perform the measurement appropriately. This was performed in the same manner for all participants according to the written instructions.

2.8. Reaching Task

The movement task consisted of pressing the start button with the upper limb of the side to be measured, moving the cylinder 10 cm toward the participant, and pressing the end button (

Figure 2). Measurements were performed in the following order: frontal task with the non-paretic upper limb, frontal task with the paretic upper limb, ipsilateral task with the non-paretic upper limb, and ipsilateral task with the paretic upper limb. The order of the measurements was fixed, and the same method was used for all participants. A 15-s rest period was observed between measurements. During the rest period, participants were allowed to stretch their muscles independently; however, the therapist was not allowed to provide any therapeutic intervention. If the participant failed to press the switch correctly or tipped the cylinder during the measurement, the motor task was remeasured. In contrast, the task was considered unperformable if the participant failed to perform the task on the third measurement. Forward reach, transport, backward reach, and total motor times, which were calculated by adding the three motor times, were used for data analysis.

2.9. Clinical Evaluation

The FMA-UE was used to evaluate the participants’ motor paralysis [

15]. Specifically, the severity of the participants’ motor paralysis was classified into five levels (no capacity: 0–10, poor capacity: 23–31, limited capacity: 32–47, notable capacity: 48–52, and full capacity: 53–66) using the FMA-UE score [

27]. The passive range of motion of the paretic shoulder joint of the participants was measured using a goniometer. Additionally, the participants’ superficial sensation in the paretic arm and fingers was scored on a three-point ordinal scale as follows: normal, dull, or absent. The participants’ joint position sense in the upper limb was evaluated using the Thumb Search Test [

28]. The Thumb Search Test is scored on a four-point ordinal scale for recognizing the position of the thumb in space. JASMID was used to investigate the use of the paretic upper limb in the participants’ daily activities [

21]. With JASMID, patients answered a total of 20 questions about the amount of use of the paretic upper limb (0: never use, 3: sometimes used, and 5: always used) and their satisfaction with use (0: almost impossible to use, 3: feel moderate difficulty, and 5: feel no difficulty at all) on a five-point ordinal scale, and the quantity and quality scores were calculated.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The clinical ratings, baseline information, and medical information obtained from the participants were subjected to descriptive statistics, and n (%) or median (25th, 75th percentile) was calculated. In particular, the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum of the motor time were calculated for the two conditions of the task, separately for the paretic and non-paretic sides. To examine the association of the total motor time on the paretic side with the FMA-UE and JASMID scores, correlation analysis was performed to calculate the correlation coefficient. A scatterplot was created with the total motor time on the paretic side on the x-axis and the FMA-UE or JASMID score on the y-axis to visualize the relationship between the data. JASP version 0.16 (

https://jasp-stats.org/) was used for these analyses.

Binomial logistic regression analysis was used to differentiate between the paretic and non-paretic sides based on total motor time. The dependent variable in this analysis was the paretic and non-paretic sides, the independent variable was total motor time, and the covariates were age, sex, and whether the dominant hand was the same as the paretic side [

29,

30]. After confirming the fit of the binomial logistic regression model, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted, and the area under the curve was calculated. Youden’s index was used to determine the optimal cutoff value to discriminate between the paretic and non-paretic sides, and the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated.

A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to reduce the dimensionality of the object motor time data collected from patients with post-stroke hemiparesis. The analysis used a “varimax” rotation method to extract significant components for predicting the FMA-UE and JASMID scores. Specifically, the variables of forward reach, transport, and backward reach times measured on the paretic side were used to calculate PCA and were calculated for the frontal and ipsilateral tasks. The component scores derived from PCA were used in subsequent models. Generalized linear models (GLM) were applied using the principal component scores as independent variables to estimate the FMA-UE and JASMID scores. The GLM employed a gamma distribution with a log link function to account for the skewed distribution of the outcome variables (FMA-UE, JASMID quantity, and JASMID quality). Additionally, the model fit was evaluated using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion, and deviance measures. For each outcome, the following models were constructed: FMA-UE as the dependent variable, JASMID quantity as the dependent variable, and JASMID quality as the dependent variable. Furthermore, jamovi version 2.2.1 (

https://www.jamovi.org) was used for these analyses, and the statistical significance level was set at 5%. The motor times obtained using the measuring device were checked for missing values as a preliminary data processing step, and the data of participants with such values were deleted from the data set.

3. Results

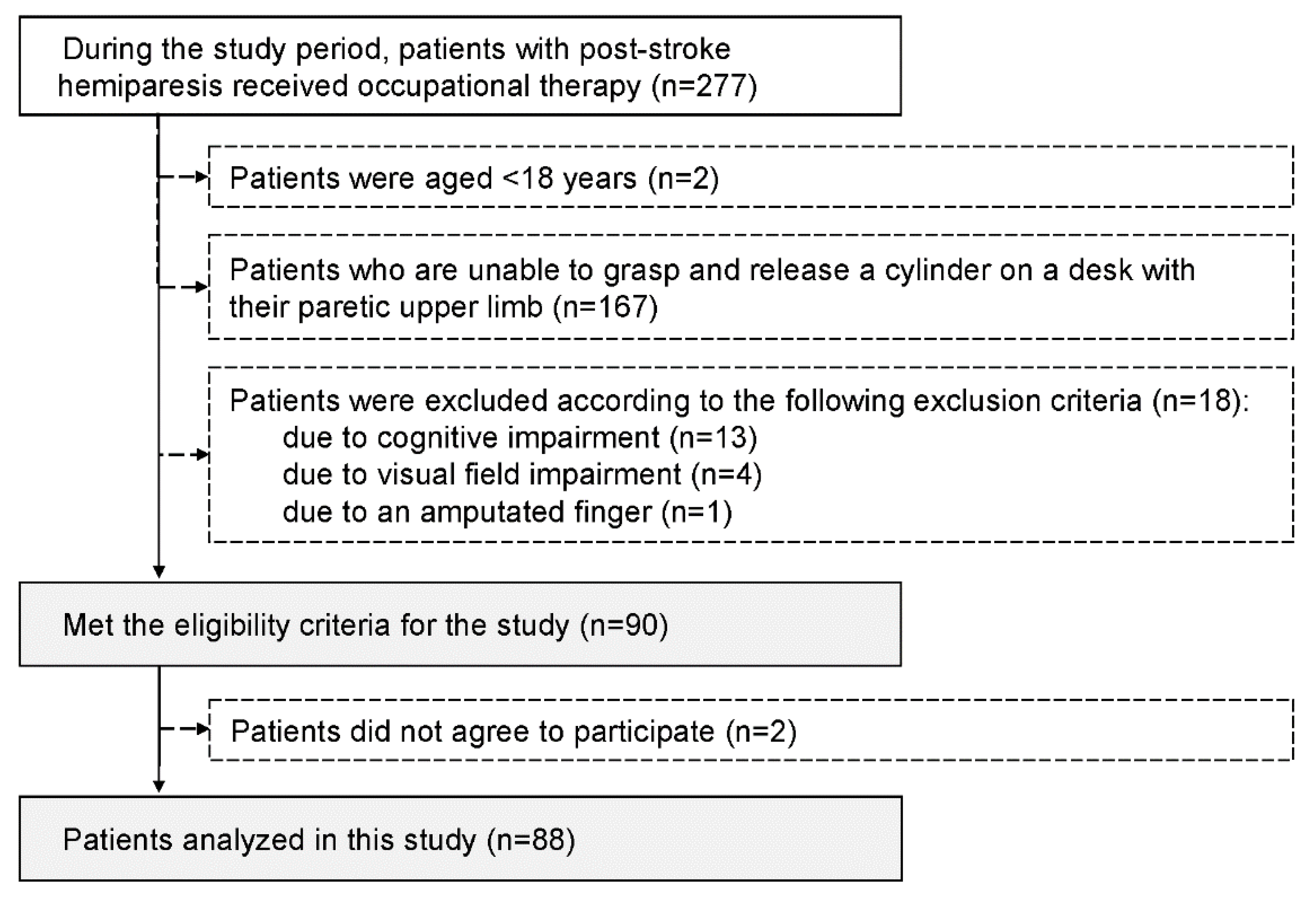

3.1. Participants

During the study period, 277 patients with post-stroke hemiparesis received occupational therapy, and 90 who met the study criteria were invited to participate in the study. Ultimately, 88 patients who agreed to participate in the study were enrolled (

Figure 3).

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the participants. No participant had missing data for clinical assessment, basic information, or medical information.

3.2. Correlation of Motor Times with Functional Assessments

The motor times for the paretic and non-paretic sides obtained during the reach task are shown in Table No missing values were found in the motor time data set.

Table 2.

Motor time during the reaching tasks.

Table 2.

Motor time during the reaching tasks.

| Motor time (s) |

Paretic side |

|

Non-paretic side |

| Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

|

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

| Frontal task |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

4.12 |

2.46 |

1.43 |

14.76 |

|

2.79 |

0.82 |

1.38 |

5.57 |

| Forward reach |

1.39 |

1.02 |

0.30 |

6.60 |

|

0.95 |

0.33 |

0.30 |

2.00 |

| Transport |

1.05 |

0.53 |

0.34 |

3.29 |

|

0.81 |

0.35 |

0.29 |

2.82 |

| Backward reach |

1.69 |

1.50 |

0.35 |

10.95 |

|

1.02 |

0.36 |

0.55 |

2.44 |

| Ipsilateral task |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total |

4.22 |

2.42 |

1.43 |

12.73 |

|

2.76 |

0.77 |

1.55 |

5.91 |

| Forward reach |

1.51 |

1.03 |

0.25 |

6.53 |

|

0.95 |

0.30 |

0.25 |

1.96 |

| Transport |

0.99 |

0.46 |

0.29 |

2.97 |

|

0.78 |

0.25 |

0.39 |

1.55 |

| Backward reach |

1.72 |

1.28 |

0.32 |

8.06 |

|

1.03 |

0.33 |

0.52 |

2.40 |

| Max, maximum; Min, minimum; SD, standard deviation. |

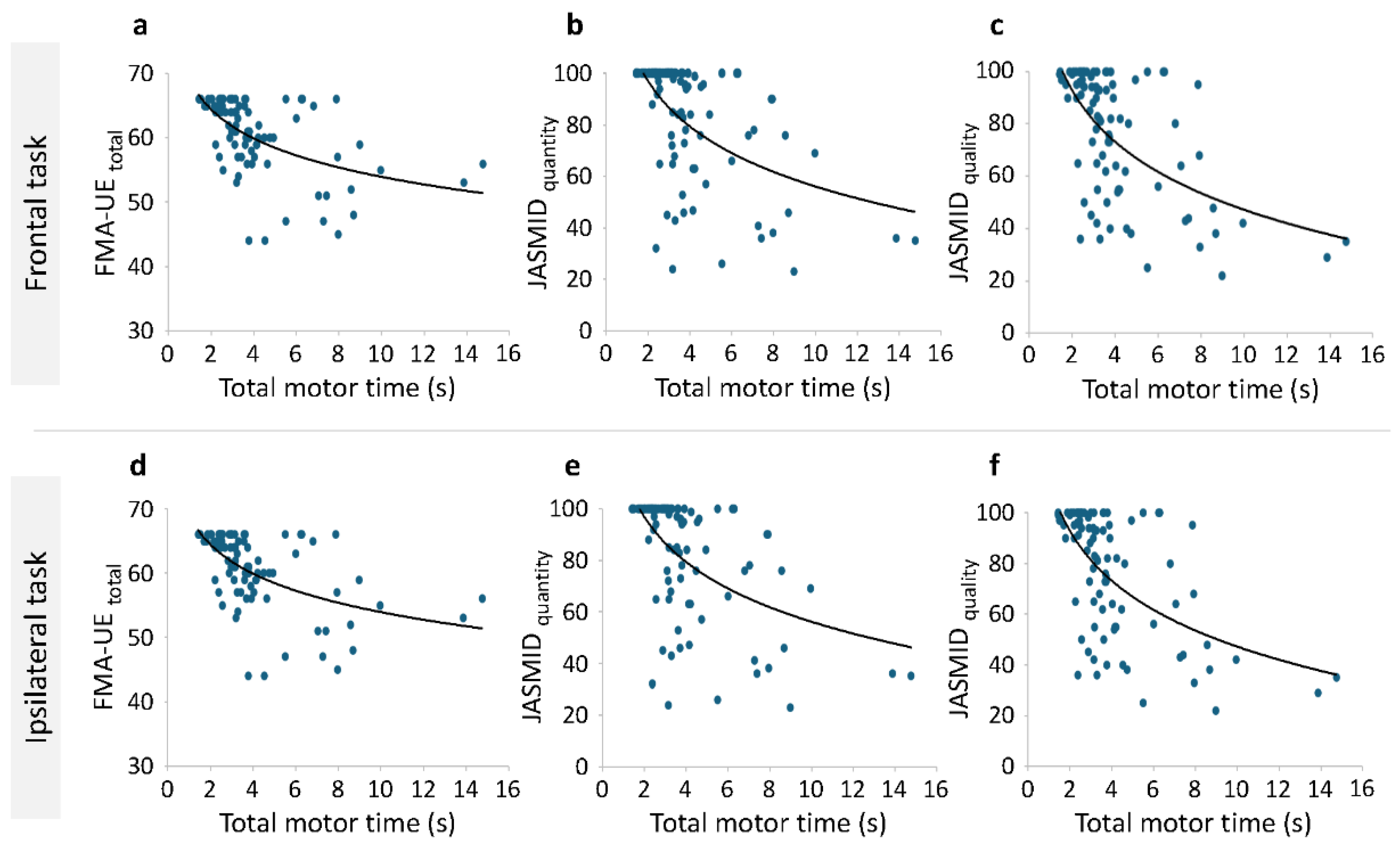

Correlation analysis was performed on the total motor time of the paretic side, the total score of the FMA-UE, and the JASMID score, and Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was calculated. A negative correlation was found between the total motor time of the paretic side and total score of the FMA-UE (Spearman's rho = -0.568, p < .001) as well as between the JASMID quantity (Spearman's rho = -0.578, p < .001) and quality (Spearman's rho = -0.537, p < .001) scores. Additionally, a negative correlation was found between the total motor time of the paretic side in the same side task and the total score of the FMA-UE (Spearman's rho = -0.534, p < .001), as well as between the JASMID quantity (Spearman's rho = -0.552, p < .001) and quality (Spearman's rho = -0.541, p < .001) scores.

Figure 4 shows the scatterplot of the total motor time on the paretic side on the x-axis and the FMA-UE or JASMID score on the y-axis. The scatterplots presented in

Figure 4 visualize the relationship between motor time and both the FMA-UE and JASMID scores, illustrating clear trends across different levels of motor impairment and functional ability. In both frontal and ipsilateral tasks, a sharp decline is observed in FMA-UE scores as total motor time increases, confirming that patients with greater impairments exhibit slower task completion times (

Figure 4a and d). Similarly, a negative trend was observed between exercise time and the JASMID scores (both quantity and quality), confirming that patients with strongly limited ADL had slower motor times (

Figure 4b, c, e, and f).

3.3. Detection of the Paretic Upper Limb with Motor Time

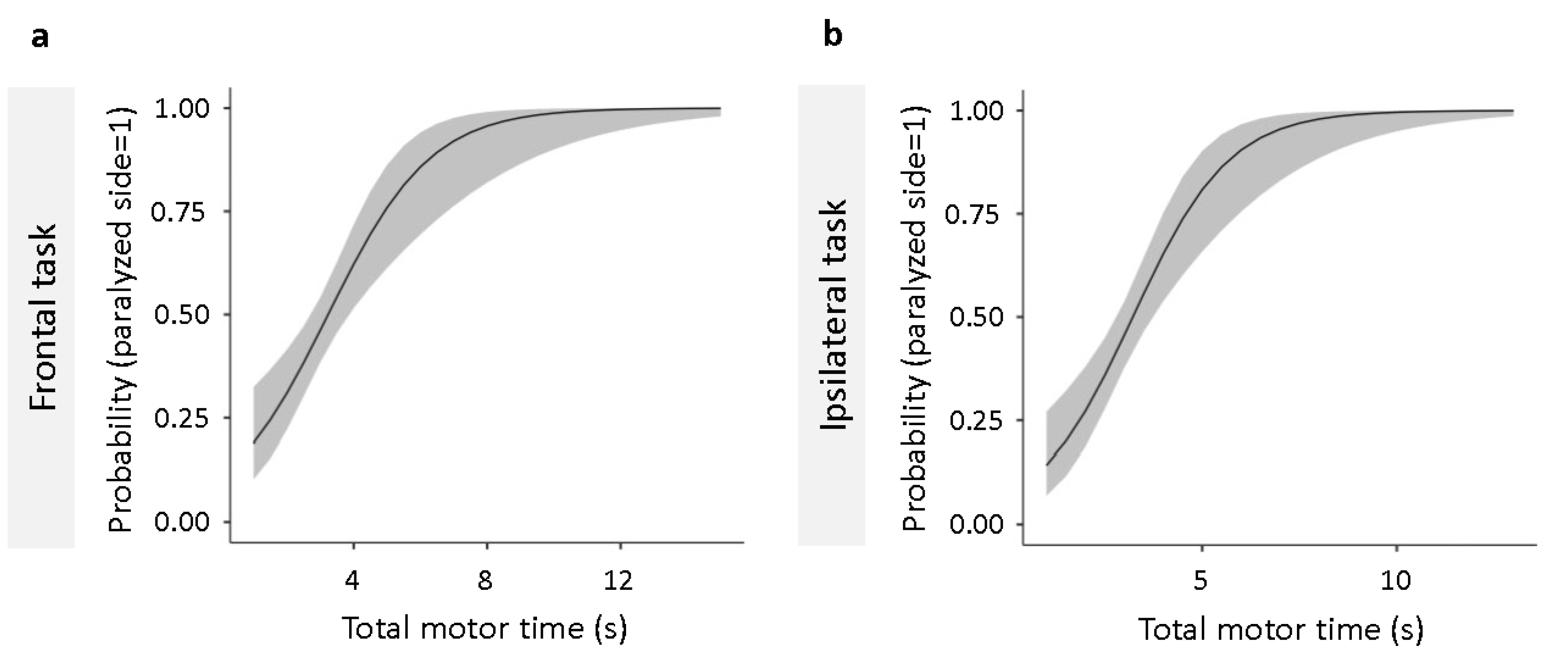

Binomial logistic regression analysis performed to determine the cutoff value that discriminates the paretic side from the non-paretic side showed that the total motor time in frontal (

Figure 5a) and same side (

Figure 5b) tasks both fit the regression model (

Table 3). Using ROC analysis, we calculated the cutoff values for discriminating between the paretic and non-paretic sides for the total motor time in the frontal and ipsilateral tasks that fit the regression model. The cutoff values for total motor time were calculated to be 3.09 and 3.22 s for the frontal and ipsilateral tasks, respectively (

Table 4).

3.4. Estimation of the Upper Limb Motor Function and Use of the Paretic Side of the Upper Limb in ADLs by Motor Time

PCA was performed to reduce the dimensionality of the data for the motor time measured on the paretic side, and one principal component (components 1–3) was clearly identified for each of the motor times on the paretic side for the frontal and ipsilateral tasks (

Table 5).

Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy indicated that the dataset was appropriate for factor analysis. A significant factor load was found for the variable of the motor time of the paretic side in each component. The formulas for components 1–3 are shown below (Equations 1–3).

We applied GLM using the principal component scores as independent variables to estimate the FMA-UE and JASMID scores, and the results showed that all components were significant predictors of the FMA-UE, JASMID quantity, and JASMID quality scores (

Table 6). To evaluate the goodness of fit of the models, we compared the AICs of the three models and found that the AIC of component 1 was lower than that of the other models for FMA-UE, JASMID quantity, and JASMID quality.

Table 7 shows the results of the GLM with component 1 as the independent variable. The estimated regression equations for the quantity and quality of the FMA-UE and JASMID scores were calculated. For FMA-UE, the negative coefficient for component 1 indicates that higher manipulation times are associated with lower FMA-UE scores (Eq 4). For JASMID quantity, longer motor times lead to a lower score, reflecting reduced hand use in ADLs (Eq 5). Similarly, for JASMID quality, this indicates that longer motor times are associated with a lower score, reflecting poorer quality of hand use in functional tasks (Eq 6).

Discussion

In this study, we hypothesized that the motor time obtained during the task of moving a cylinder on the paretic side by patients with post-stroke hemiparesis would be related to the results of other functional assessments, that the motor time could be used to determine the paretic and non-paretic sides, and that it would be possible to estimate the use of the paretic upper limb. First, we performed a correlation analysis of the total motor time of the paretic side, the total score of the FMA-UE, and the JASMID score. Our results demonstrated that total motor time during simple reaching tasks significantly correlates with established clinical measures, such as the FMA-UE and JASMID. Additionally, to estimate the use of the paretic side for upper limb motor function and ADL from the forward reach, transport, and backward reach times of the paretic side, we applied GLM using the principal component scores obtained by PCA as independent variables. All components were shown to be significant predictors of FMA-UE, JASMID quantity, and JASMID quality scores, and the estimated regression equations for each score were calculated. These findings suggest that motor time can serve as a quick, reliable, and clinically relevant indicator of motor impairment and functional use of the upper limb in daily activities. The primary advantage of this tool lies in its simplicity and time efficiency. Compared to traditional assessments, which are usually time-consuming and require specialized training, this tool uses a straightforward reaching task and readily available technology to record motor time. Consequently, this allows for rapid assessment and helps therapists spend more time with their patients in rehabilitation. This is believed to be beneficial in busy clinical environments where time constraints are a major issue [

31]. Furthermore, the quantitative nature of motor time eliminates subjective bias, providing clinicians with objective data to guide rehabilitation interventions. The correlation between motor time and functional use of the upper limb, as measured by JASMID, suggests that this tool can be used to monitor progress in ADLs.

To determine the cutoff value for discriminating the paretic and non-paretic sides of the patients, we performed ROC analysis on the total motor time for both the frontal and ipsilateral tasks that fit the regression model using binomial logistic regression analysis. The cut-off value for the total motor time to discriminate between the paretic and non-paretic sides was calculated to be 3.09 and 3.22 s for the frontal and ipsilateral tasks, respectively. In clinical practice, the degree of functional impairment is sometimes assessed by simply comparing the differences in movement between the paretic and non-paretic sides of the patient's upper limbs and fingers. The measurement method used in this study follows the flow of diagnosis and evaluation by comparing the paretic and non-paretic sides in clinical practice and provides a cut-off value that can distinguish between the paretic and non-paretic sides based on the time taken for the simple movement task of carrying a cylinder. Additionally, the development of this motor time-based tool has important implications for clinical practice. By establishing cut-off values that distinguish between the paretic and non-paretic sides, this tool enables clinicians to quickly identify the affected limb. Notably, this is particularly valuable in early rehabilitation stages, where timely intervention is critical for optimizing recovery outcomes. Clinicians can use motor time as a practical metric to adjust rehabilitation programs based on objective performance data, enhancing the personalization of therapy [

32].

Previous research [

24] has shown that the heavy-weight item in the SHAP movement task is a simple test item that patients are most likely to succeed with [

25]. This is believed to be because the item can be grasped using a group flexion and partial extension movement without requiring a high level of voluntary control of the fingers, and it does not require a change in forearm position during transport. Although SHAP also has items that carry light cylinders, receiving feedback from deep sensory when carrying heavy cylinders is easier; therefore, the weight of the item may not have increased the difficulty level but may have been a factor in improving the accuracy of the movement [

33]. Patients with hemiparesis often experience difficulty improving motor coordination and reducing the time required to perform movements. Therefore, measuring the motor time required to complete a movement is important for assessing functional impairment and treatment response in patients with mild hemiparesis [

34]. In summary, an assessment of the upper limb function that uses time spent on simple motor tasks as an outcome, such as the one used in this study, has various applications in clinical practice, and it is beneficial to use it in conjunction with existing upper limb function assessments that have a ceiling effect in patients with mild hemiparesis.

One limitation of this study is the potential difficulty in generalizing the cut-off values for total motor time to different populations or types of patients with stroke. The cut-off values identified in this study were derived from a specific cohort of patients with post-stroke hemiparesis and may not apply to individuals with varying levels of impairment, different stroke etiologies, different periods after onset, or those undergoing different rehabilitation programs. Sensory perception is related to the ability to manipulate objects, such as the measurement task in this study [

35]. Although few of the participants in this study had severe sensory impairments, the effect of the presence or absence of sensory impairments on the motor time of the movement task in this study has not been clarified. Additionally, variability may have existed in how patients were instructed to perform or how they performed the tasks, potentially introducing bias in the motor time measurements. While efforts were made to standardize task instructions and procedures, differences in patient understanding, motivation, or fatigue could have influenced performance, thereby affecting the accuracy of the motor time as an indicator of upper limb function.

Moving forward, this motor time-based tool has the potential for widespread application beyond stroke rehabilitation. Its ease of use and objective nature make it a promising candidate for assessing motor function in other neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis [

36,

37]. Moreover, integrating this tool with wearable technology or mobile applications could facilitate remote assessments, enabling continuous monitoring of motor function in home-based rehabilitation programs [

38]. This would not only enhance patient engagement but also allow clinicians to track recovery in real time, adjusting interventions as needed. Notably, recognizing that this study represents the first step in the development process is essential. Further research is needed to refine the tool, including the exploration of its utility across different stroke populations and in various clinical settings. Additionally, longitudinal studies are required to determine whether changes in motor time correspond to long-term improvements in upper limb function and ADL performance.

Conclusions

This study presents the development of a novel, time-efficient evaluation tool for assessing upper limb motor function in patients with stroke. By leveraging on total motor time, this tool provides clinicians with a quick and objective method to evaluate motor impairment and functional use of the upper limb. While further validation is necessary, the tool holds promise for enhancing rehabilitation assessment and improving patient outcomes in various clinical contexts.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

D.S. and T.H. collated the literature and conceived the study. D.S., T.H., and Y.N. developed the protocol. D.S., M.Y., R.A., and K.S. recruited participants and collected data. D.S. and T.H. were involved in data analysis. D.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.H., Y.N., and M.A. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have agreed with the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant number: JP 24K14384).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine (Approval Number 22-061-6238, Approval date 7 September 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. These data are not publicly available because of privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the occupational therapists at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Jikei University Hospital, for their cooperation in obtaining the data for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- van Mierlo, M.L.; van Heugten, C.M.; Post, M.W.M.; Hajós, T.R.S.; Kappelle, L.J.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A. Quality of life during the first two years post stroke: The Restore4Stroke cohort study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2016, 41, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Lin, T.; Wu, M.; Cai, G.; Ding, Q.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Lan, Y. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on upper-limb and finger function in stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.L.; Yang, Y.X.; Jiang, H.; Duan, X.Y.; Gu, L.J.; Qing, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.X. Brain-machine interface-based training for improving upper extremity function after stroke: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurosci 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nudo, R.J.; Milliken, G.W.; Jenkins, W.M.; Merzenich, M.M. Use-dependent alterations of movement representations in primary motor cortex of adult squirrel monkeys. J Neurosci 1996, 16, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.A.; Allred, R.P.; Jefferson, S.C.; Kerr, A.L.; Woodie, D.A.; Cheng, S.Y.; Adkins, D.L. Motor system plasticity in stroke models: Intrinsically use-dependent, unreliably useful. Stroke 2013, 44, S104–S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.; Kanzler, C.M.; Lambercy, O.; Luft, A.R.; Veerbeek, J.M. Systematic review on kinematic assessments of upper limb movements after stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, G.; van Wegen, E.E.H.; Burridge, J.H.; Winstein, C.J.; van Dokkum, L.E.H.; Alt Murphy, M.; Levin, M.F.; Krakauer, J.W.; Lang, C.E.; Keller, T.; A., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Standardized measurement of quality of upper limb movement after stroke: Consensus-based core recommendations from the second stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2019, 33, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, L.; Térémetz, M.; Bleton, J.P.; Baron, J.C.; Maier, M.A.; Lindberg, P.G. Upper limb outcome measures used in stroke rehabilitation studies: A systematic literature review. PLOS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantin, J.; Verneau, M.; Godbolt, A.K.; Pennati, G.V.; Laurencikas, E.; Johansson, B.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L.; Baron, J.C.; Borg, J.; Lindberg, P.G. Recovery and prediction of bimanual hand use after stroke. Neurology 2021, 97, e706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukal, T.M.; Ellis, M.D.; Dewald, J.P.A. Shoulder abduction-induced reductions in reaching work area following hemiparetic stroke: Neuroscientific implications. Exp Brain Res 2007, 183, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Park, D.; Rha, D.W.; Nam, H.S.; Jo, Y.J.; Kim, D.Y. Kinematic analysis of movement patterns during a reach-and-grasp task in stroke patients. Front Neurol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, D.; Hamaguchi, T.; Kanemura, N.; Yasojima, T.; Kubota, K.; Suwabe, R.; Nakayama, Y.; Abo, M. Feature analysis of joint motion in paralyzed and non-paralyzed upper limbs while reaching the occiput: A cross-sectional study in patients with mild hemiplegia. PLOS ONE 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.Y.; Lin, K.C.; Chen, C.K.; Liing, R.J.; Wu, C.Y.; Chang, W.Y. Concurrent and predictive validity of arm kinematics with and without a trunk restraint during a reaching task in individuals with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015, 96, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rech, K.D.; Salazar, A.P.; Marchese, R.R.; Schifino, G.; Cimolin, V.; Pagnussat, A.S. Fugl-Meyer assessment scores are related with kinematic measures in people with chronic hemiparesis after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugl-Meyer, A.R.; Jääskö, L.; Leyman, I.; Olsson, S.; Steglind, S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med 1975, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, R.C. A performance test for assessment of upper limb function in physical rehabilitation treatment and research. Int J Rehabil Res 1981, 4, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Hsu, M.J.; Sheu, C.F.; Wu, T.S.; Lin, R.T.; Chen, C.H.; Hsieh, C.L. Psychometric comparisons of 4 measures for assessing upper-extremity function in people with stroke. Phys Ther 2009, 89, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, G.; Sunnerhagen, K.S.; Persson, H.C.; Opheim, A.; Alt Murphy, M. Kinematic upper extremity performance in people with near or fully recovered sensorimotor function after stroke. Physiother Theory Pract 2019, 35, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Volland, G.; Kashman, N.; Weber, K. Adult norms for the Box and Block Test of manual dexterity. Am J Occup Ther 1985, 39, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, E.; Miller, N.E.; Novack, T.A.; Cook, E.W.; Fleming, W.C.; Nepomuceno, C.S.; Connell, J.S.; Crago, J.E. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993, 74, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, A.; Kakuda, W.; Taguchi, K.; Uruma, G.; Abo, M. The reliability and validity of a new subjective assessment scale for poststroke upper limb hemiparesis, the Jikei assessment scale for motor impairment in daily living. Tokyo Jikei Medical Journal 2010, 125, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.C.; Cramer, S.C. Patient-reported measures provide unique insights into motor function after stroke. Stroke 2013, 44, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, C.C.; Harnish, S.M.; Brello, J.; Lanzi, A.M.; Cohen, M.L. Poststroke communication ability predicts patient-informant discrepancies in reported activities and participation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2024, 33, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, C.M.; Chappell, P.H.; Kyberd, P.J. Establishing a standardized clinical assessment tool of pathologic and prosthetic hand function: Normative data, reliability, and validity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Hamaguchi, T.; Suzuki, M.; Sakamoto, D.; Shikano, J.; Nakaya, N.; Abo, M. Estimation of motor impairment and usage of upper extremities during daily living activities in poststroke hemiparesis patients by observation of time required to accomplish hand dexterity tasks. BioMed Res Int 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, F.; Costaggiu, D.; Mandas, A.; State, M.M. Mini-Mental State Examination: Optimal cut-off levels for mild and severe cognitive impairment. Geriatrics (Basel) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoonhorst, M.H.; Nijland, R.H.; van den Berg, J.S.; Emmelot, C.H.; Kollen, B.J.; Kwakkel, G. How do Fugl-Meyer arm motor scores relate to dexterity according to the action research arm test at 6 months poststroke? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015, 96, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, K. Maternal finger search test – Examination of joint localization disorder (in Japanese). Clin Neurol 1986, 26, 448. [Google Scholar]

- Coupar, F.; Pollock, A.; Rowe, P.; Weir, C.; Langhorne, P. Predictors of upper limb recovery after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2012, 26, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Hu, H.J.; Li, L.F.; Li, L. Comparison of dominant hand to non-dominant hand in conduction of reaching task from 3D kinematic data: Trade-off between successful rate and movement efficiency. Math Biosci Eng 2019, 16, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Whitall, J.; Kwakkel, G.; Mehrholz, J.; Ewings, S.; Burridge, J. The effect of time spent in rehabilitation on activity limitation and impairment after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prange-Lasonder, G.B.; Alt Murphy, M.; Lamers, I.; Hughes, A.M.; Buurke, J.H.; Feys, P.; Keller, T.; Klamroth-Marganska, V.; Tarkka, I.M.; Timmermans, A.; et al. European evidence-based recommendations for clinical assessment of upper limb in neurorehabilitation (CAULIN): Data synthesis from systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines and expert consensus. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aman, J.E.; Elangovan, N.; Yeh, I.L.; Konczak, J. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training for improving motor function: A systematic review. Front Hum Neurosci 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodbury, M.L.; Velozo, C.A.; Richards, L.G.; Duncan, P.W.; Studenski, S.; Lai, S.M. Dimensionality and construct validity of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the upper extremity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007, 88, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, L.M.; Matyas, T.A.; Baum, C. Effects of somatosensory impairment on participation after stroke. Am J Occup Ther 2018, 72, 7203205100p7203205101–7203205100p7203205110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, C.; Domingos, J.; Cunha, G.; Santos, A.T.; Fernandes, R.M.; Abreu, D.; Gonçalves, N.; Matthews, H.; Isaacs, T.; Duffen, J.; et al. A systematic review of the characteristics and validity of monitoring technologies to assess Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beswick, E.; Fawcett, T.; Hassan, Z.; Forbes, D.; Dakin, R.; Newton, J.; Abrahams, S.; Carson, A.; Chandran, S.; Perry, D.; et al. A systematic review of digital technology to evaluate motor function and disease progression in motor neuron disease. J Neurol 2022, 269, 6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerzopf, L.; Luft, A.R.; Baldissera, A.; Frey, S.; Klamroth-Marganska, V.; Spiess, M.R. Remotely assessing motor function and activity of the upper extremity after stroke: A systematic review of validity and clinical utility of tele-assessments. Clin Rehabil 2024, 38, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Configuration of the instrument and method of measuring motion time. (a) Configuration and dimensions. (b) Methods of measuring motor time.

Figure 1.

Configuration of the instrument and method of measuring motion time. (a) Configuration and dimensions. (b) Methods of measuring motor time.

Figure 2.

Measurement setup and limb positions of the participants. The two conditions of the motor task were (a) the frontal task, in which the stand was placed 20 cm away from the bottom edge of the desk; and (b) the ipsilateral task, in which the stand was placed 20 cm away from the bottom edge of the desk and 30 cm away from the midline of the start and stop switches. (c) Participants' limb positions.

Figure 2.

Measurement setup and limb positions of the participants. The two conditions of the motor task were (a) the frontal task, in which the stand was placed 20 cm away from the bottom edge of the desk; and (b) the ipsilateral task, in which the stand was placed 20 cm away from the bottom edge of the desk and 30 cm away from the midline of the start and stop switches. (c) Participants' limb positions.

Figure 3.

Patient selection procedure.

Figure 3.

Patient selection procedure.

Figure 4.

Correlation between total motor time and functional assessment scores. Scatterplots show the relationship between total motor time and FMA-UE scores (a, d), as well as between the JASMID quantity (b, e) and quality (c, f) scores in frontal (a–c) and ipsilateral (d–f) tasks. The logarithmic trend lines illustrate significant negative correlations (p < .001), indicating that longer motor times are associated with greater motor impairment and reduced upper limb use in daily activities. FMA-UE, Fugl–Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity; JASMID, Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living.

Figure 4.

Correlation between total motor time and functional assessment scores. Scatterplots show the relationship between total motor time and FMA-UE scores (a, d), as well as between the JASMID quantity (b, e) and quality (c, f) scores in frontal (a–c) and ipsilateral (d–f) tasks. The logarithmic trend lines illustrate significant negative correlations (p < .001), indicating that longer motor times are associated with greater motor impairment and reduced upper limb use in daily activities. FMA-UE, Fugl–Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity; JASMID, Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living.

Figure 5.

Binomial logistic regression analysis for total motor time in frontal and ipsilateral tasks. The logistic regression models predict the probability of the upper limb being on the paretic side based on total motor time. (a) shows the regression curve for the frontal, and (b) indicates that for the ipsilateral task. The vertical axis represents the probability that the limb is paretic, with higher values indicating a greater likelihood. Both models demonstrate significant predictive accuracy (p < .001). ROC curve analysis was used to determine cut-off values for distinguishing between the paretic and non-paretic sides. FMA-UE; Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity; JASMID, Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Figure 5.

Binomial logistic regression analysis for total motor time in frontal and ipsilateral tasks. The logistic regression models predict the probability of the upper limb being on the paretic side based on total motor time. (a) shows the regression curve for the frontal, and (b) indicates that for the ipsilateral task. The vertical axis represents the probability that the limb is paretic, with higher values indicating a greater likelihood. Both models demonstrate significant predictive accuracy (p < .001). ROC curve analysis was used to determine cut-off values for distinguishing between the paretic and non-paretic sides. FMA-UE; Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity; JASMID, Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the analyzed patients.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the analyzed patients.

| Characteristics |

All (n=88) |

| Age (years) |

|

63 (52, 73) |

| Sex |

Female |

38 (43) |

| |

Male |

50 (57) |

| Weight (kg) |

|

62 (52, 71) |

| Height (cm) |

|

163 (156, 170) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

|

23 (21, 25) |

| Paretic hand |

Left |

36 (41) |

| |

Right |

52 (59) |

| Dominant hand |

Left |

5 (6) |

| |

Right |

83 (94) |

| Laterality in the paretic and dominant hand |

Ipsilateral side |

53 (60) |

| |

Contralateral side |

35 (40) |

| Diagnosis |

CI |

53 (60) |

| |

ICH |

35 (40) |

| Time from onsets (months) |

|

0 (0, 31) |

| FMA-UE |

Total |

62 (57, 65) |

| |

Part A |

35 (33, 36) |

| |

Part B |

10 (9, 10) |

| |

Part C |

14 (13, 14) |

| |

Part D |

5 (3, 6) |

| FMA-UE severity |

Limited capacity (32 ≤ score ≤ 47) |

5 (6) |

| |

Notable capacity (48 ≤ score ≤ 52) |

4 (10) |

| |

Full capacity (53 ≤ score ≤ 66) |

79 (90) |

| Range of motion for shoulder flexion (˚) |

|

180 (170, 180) |

| Sense of touch |

Finger |

Normal |

67 (76) |

| |

|

Decline |

21 (24) |

| |

Arm |

Normal |

72 (82) |

| |

|

Decline |

16 (18) |

| Thumb Localizing Test |

Normal |

72 (82) |

| |

Mild |

10 (11) |

| |

Moderate |

5 (6) |

| |

Severe |

1 (1) |

| JASMID |

Quantity |

95 (69, 100) |

| |

Quality |

83 (55, 97) |

| Values are presented as n (%) or median (25th, 75th percentile). CI, cerebral infarction; FMA-UE, Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; JASMID, Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living. |

Table 3.

Model goodness of fit results of the binomial logistic regression analysis.

Table 3.

Model goodness of fit results of the binomial logistic regression analysis.

| Model |

Deviance |

AIC |

McFadden’s R2

|

Overall model test |

|

Estimate |

95% CI |

SE |

Z |

p |

| X2

|

df |

p |

|

Lower |

Upper |

| Total motor time of frontal task |

215.48 |

225.48 |

0.12 |

28.50 |

4 |

<.001 |

|

0.65 |

0.34 |

0.96 |

0.16 |

4.07 |

<.001 |

| Total motor time of ipsilateral task |

208.5 |

218.05 |

0.15 |

35.94 |

4 |

<.001 |

|

0.81 |

0.45 |

1.17 |

0.18 |

4.39 |

<.001 |

| AIC, Akaike’s information criterion; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error. Binomial logistic regression was used, with the statistical significance set at 0.05 (N = 88). |

Table 4.

Results of the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis.

Table 4.

Results of the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis.

| Scale |

Cut off point |

Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

Youden’s index |

AUC |

| Total motor time of frontal task |

3.09 |

69.32 |

63.64 |

65.59 |

67.47 |

0.33 |

0.69 |

| Total motor time of ipsilateral task |

3.22 |

79.55 |

57.95 |

65.42 |

73.91 |

0.38 |

0.73 |

| AUC, Area under the curve: NPV, Negative predictive value; PPV, Positive predictive value. |

Table 5.

Results of the principal component analysis.

Table 5.

Results of the principal component analysis.

| Component |

% of variance |

Bartlett’s test of sphericity |

KMO measure of sampling adequacy |

| X2

|

df |

p |

| 1 |

62.91 |

359.76 |

15 |

<.001 |

0.74 |

| 2 |

59.99 |

41.34 |

3 |

<.001 |

0.61 |

| 3 |

72.69 |

93.41 |

3 |

<.001 |

0.67 |

| KMO, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin. |

Table 6.

Models calculated using generalized linear model with component scores as independent variables.

Table 6.

Models calculated using generalized linear model with component scores as independent variables.

| Model |

Deviance |

AIC |

McFadden’s R2

|

Log-likelihood ratio test |

| X2

|

df |

p |

| FMA-UE |

| Component 1 |

0.63 |

542.64 |

0.28 |

34.89 |

1 |

<.001 |

| Component 2 |

0.64 |

543.93 |

0.26 |

32.88 |

1 |

<.001 |

| Component 3 |

0.64 |

544.57 |

0.26 |

32.29 |

1 |

<.001 |

| JASMID quantity |

| Component 1 |

7.88 |

810.07 |

0.22 |

33.00 |

1 |

<.001 |

| Component 2 |

7.91 |

810.41 |

0.22 |

33.06 |

1 |

<.001 |

| Component 3 |

8.08 |

812.30 |

0.20 |

29.35 |

1 |

<.001 |

| JASMID quality |

| Component 1 |

7.69 |

793.61 |

0.31 |

45.11 |

1 |

<.001 |

| Component 2 |

7.76 |

794.34 |

0.31 |

44.43 |

1 |

<.001 |

| Component 3 |

8.04 |

797.56 |

0.28 |

38.83 |

1 |

<.001 |

| AIC, Akaike's information criterion; FMA-UE, Fugl–Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity; JASMID, Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living. |

Table 7.

Generalized linear model for the prediction of FMA-UE and JASMID.

Table 7.

Generalized linear model for the prediction of FMA-UE and JASMID.

| Prediction |

Parameter |

Estimate |

SE |

95% CI |

exp (B) |

95 exp (B) CI |

z |

p |

| Lower |

Upper |

Lower |

Upper |

| FMA-UE |

Intercept |

4.10 |

0.01 |

4.09 |

4.12 |

60.49 |

59.45 |

61.55 |

464.31 |

<.001 |

| component 1 |

-0.05 |

0.01 |

-0.07 |

-0.04 |

0.95 |

0.93 |

0.97 |

-5.92 |

<.001 |

| JASMID quantity |

Intercept |

4.39 |

0.03 |

4.34 |

4.45 |

80.90 |

76.61 |

85.51 |

156.70 |

<.001 |

| component 1 |

-0.17 |

0.03 |

-0.22 |

-0.11 |

0.84 |

0.80 |

0.89 |

-6.02 |

<.001 |

| JASMID quality |

Intercept |

4.31 |

0.03 |

4.25 |

4.37 |

74.52 |

70.34 |

79.04 |

144.83 |

<.001 |

| component 1 |

-0.21 |

0.03 |

-0.27 |

-0.15 |

0.81 |

0.76 |

0.86 |

-7.07 |

<.001 |

| CI, confidence interval; FMA-UE, Fugl–Meyer Assessment of the Upper Extremity; JASMID, Jikei Assessment Scale for Motor Impairment in Daily Living; SE, standard error. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).