1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) ranks among the foremost contributors to mortality and disability globally, especially affecting young and middle-aged individuals [

1]. Annually, more than 50 million people worldwide experience TBI, leading to substantial declines in quality of life and placing considerable financial strains on both families and society [

2,

3]. TBI can be categorized into mild, moderate, or severe classifications based on the extent of the injury, each leading to different prognoses. It is essential to comprehend the molecular mechanisms linked to secondary brain injuries at various levels of TBI severity to enhance the development of targeted therapeutic interventions [

4].

TBI encompasses both primary and secondary injury phases. Primary injuries arise from the immediate mechanical forces applied to the brain, resulting in structural damage that occurs instantaneously and is frequently irreversible. In contrast, secondary injuries stem from subsequent biochemical alterations and are the main emphasis of therapeutic strategies. Prior research has pinpointed various mechanisms of neuronal death following TBI, including necrosis, apoptosis, pyroptosis, and autophagy dysfunction [

5]. Extensive investigations have been conducted by researchers to elucidate these processes in order to pinpoint potential therapeutic targets; however, clinical interventions aimed at these mechanisms have produced suboptimal outcomes.

Ferroptosis, a recently characterized form of regulated cell death that diverges from conventional apoptotic pathways, was initially described in 2012 by Dixon et al [

6]. It is marked by the buildup of lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) and excessive iron accumulation. Subsequent investigations have revealed that the ferroptotic pathway is triggered post-TBI, leading to neuronal cell death [

7]. The preliminary observations of ferroptosis within the central nervous system were identified in tumor models, and subsequent investigations validated its presence in models of stroke and spinal cord injury [

8,

9]. Nevertheless, the association between ferroptosis and the extent of neuronal damage subsequent to traumatic brain injury, particularly in models exhibiting differing levels of injury severity, is still not well elucidated [

10]. Consequently, this research seeks to develop a rat model of TBI encompassing varying degrees of severity (mild, mild-moderate, and severe) to explore the relationship between cortical ferroptosis and neurological deficits, thus offering a theoretical framework for investigating ferroptosis in the context of neurotrauma [

11].

2. Materials and Methods

The Materials and Methods section must be articulated with sufficient detail to enable replication and further exploration of the published findings. It is imperative to recognize that the submission of your manuscript entails the obligation to make all materials, data, computational code, and protocols related to the publication accessible to the readership. Any limitations regarding the availability of materials or information should be disclosed at the time of submission. Novel methodologies and protocols must be elaborated upon comprehensively, whereas established methods may be succinctly summarized and appropriately referenced.

2.1. Experimental Animals

Healthy adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, classified as specific pathogen-free (SPF) and weighing between 250 and 300 grams, were utilized in the experiments. The rats were maintained in a controlled environment with a temperature range of 20-25°C, humidity levels of 40%-55%, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle for one week prior to the experimental procedures. They were provided with food and water ad libitum. Twelve hours preceding the surgical intervention, the rats were subjected to fasting, although access to water was permitted. The experimental protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Kunming Medical University (Approval number: kmmu20220651), and all measures were taken to minimize the distress experienced by the experimental animals throughout the study.

2.2. TBI Animal Model

TBI model was developed utilizing the Feeney free-fall impact technique. Rats were anesthetized via an intraperitoneal injection of 3% pentobarbital sodium at a dosage of 30-40 mg/kg. Following anesthesia, the rats’ scalps were shaved and disinfected. They were then immobilized on a stereotaxic apparatus, and a midline incision of approximately 3 cm was performed on the scalp to expose the skull. A dental drill was employed to create a 6 mm diameter bone window located 2 mm posterior to the coronal suture and 2.5 mm lateral to the sagittal suture on the right side of the skull, ensuring the integrity of the dura mater was maintained.

In the sham group, only the bone window was drilled without any impact being applied. For the TBI groups, a 40-gram weight was dropped vertically onto the exposed dura mater from varying heights: 15 cm for the mild TBI group (mTBI), 20 cm for the mild-moderate TBI group (mmTBI), and 25 cm for the severe TBI group (sTBI). This impact resulted in contusions and lacerations of the brain tissue. Following the induction of injury, hemostasis was achieved, and the scalp was sutured closed with interrupted stitches. Postoperatively, the rats were placed in an incubator to recover from anesthesia before being returned to their cages. Standard postoperative care included routine wound disinfection and the administration of antibiotics to mitigate the risk of infection.

Twenty-four hours post-injury, the modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) was utilized to evaluate the neurological function of the rats. The mNSS assesses sensorimotor function through five distinct tests: tail suspension, motor function, sensory function, beam balance, and reflexes/abnormal movements. Scores range from 0 (normal) to 18, with higher scores indicating increased neurological impairment. Scores of 1-6 denote mild injury, 7-12 indicate moderate injury, and scores exceeding 13 reflect severe injury.

2.3. Experimental Groups

The rats were randomly divided into four groups (n=9):

Neurological function was assessed using the mNSS test 24 hours after TBI induction, and rats that met the injury criteria were included in the subsequent experiments.

2.4. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Seven days after inducing TBI, the rats underwent MRI scanning to assess brain tissue injury. The MRI scanner used was a Philips Ingenia 3.0T from the Netherlands. Scanning parameters were as follows:

Coronal T2-weighted imaging (T2WI): Resolution 0.3 × 0.33 × 2 mm, Repetition Time (TR) 2000 ms, Echo Time (TE) 80 ms.

Coronal T2* imaging (T2*WI): Resolution 0.53 × 0.53 × 2 mm, TR 510 ms, TE 16 ms, Flip Angle 18°.

2.5. Prussian Blue Staining

Prussian blue staining was employed to identify non-heme iron accumulation in the cortical tissue of the rats. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections, measuring 3-5 µm in thickness, underwent deparaffinization and rehydration through a series of solutions: xylene I for 20 minutes, xylene II for 20 minutes, absolute ethanol I for 5 minutes, absolute ethanol II for 5 minutes, and 75% ethanol for 5 minutes. The sections were subsequently rinsed in tap water and washed three times with distilled water. Following this, the sections were stained for one hour in a freshly prepared Prussian blue staining solution, which consisted of potassium ferrocyanide and hydrochloric acid. After two washes with distilled water, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 1-5 minutes and rinsed in running water. Finally, the sections were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and cleared in xylene prior to mounting with neutral gum. Iron deposition was visualized as brown granules, while the nuclei exhibited a light blue coloration.

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Seven days post-traumatic brain injury (TBI), the rats were euthanized, and the brain tissues adjacent to the injury site were collected. The cortex was sectioned into 1 mm³ tissue blocks and preserved in an electron microscope fixative. Transmission electron microscopy was conducted by Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was utilized to evaluate the expression levels of ferroptosis-related proteins. Protein quantification was performed using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method, and a 10% SDS-PAGE was employed for protein separation. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes at 100 V for one hour. Post-transfer, the membranes were washed twice with TBST for 5 minutes each and subsequently blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. Following blocking, the membranes were washed again with TBST for 5 minutes and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in 0.1% TBST: FTH1 (1:1000) and GPX4 (1:1000). The following day, the membranes were washed three times with TBST for 15 minutes each and incubated with a secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit, 1:5000) for 2 hours at room temperature. After incubation, the membranes were washed three times with TBST, followed by chemiluminescent detection using the Amersham Imager 600 system. Densitometric analysis was conducted using ImageJ software.

2.8. MDA (Malondialdehyde) Content Measurement

Lipid peroxidation was evaluated by quantifying malondialdehyde (MDA) levels using an MDA assay kit (Suzhou Keming, MDA-1-Y). The brain tissue was homogenized in ice-cold extraction buffer at a ratio of 1:5–10 (g tissue: mL buffer). The homogenate was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. MDA levels were measured at 532 nm and 600 nm using a spectrophotometer, and the MDA concentration was determined using a standard curve.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was conducted at least three times. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the correlation between two groups, while one-way ANOVA was utilized for comparisons among multiple groups. A p-value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 8.4.3 software.

3. Results

3.1. MRI Reveals Iron Accumulation in Brain Tissue Adjacent to Injury Site in TBI Rats

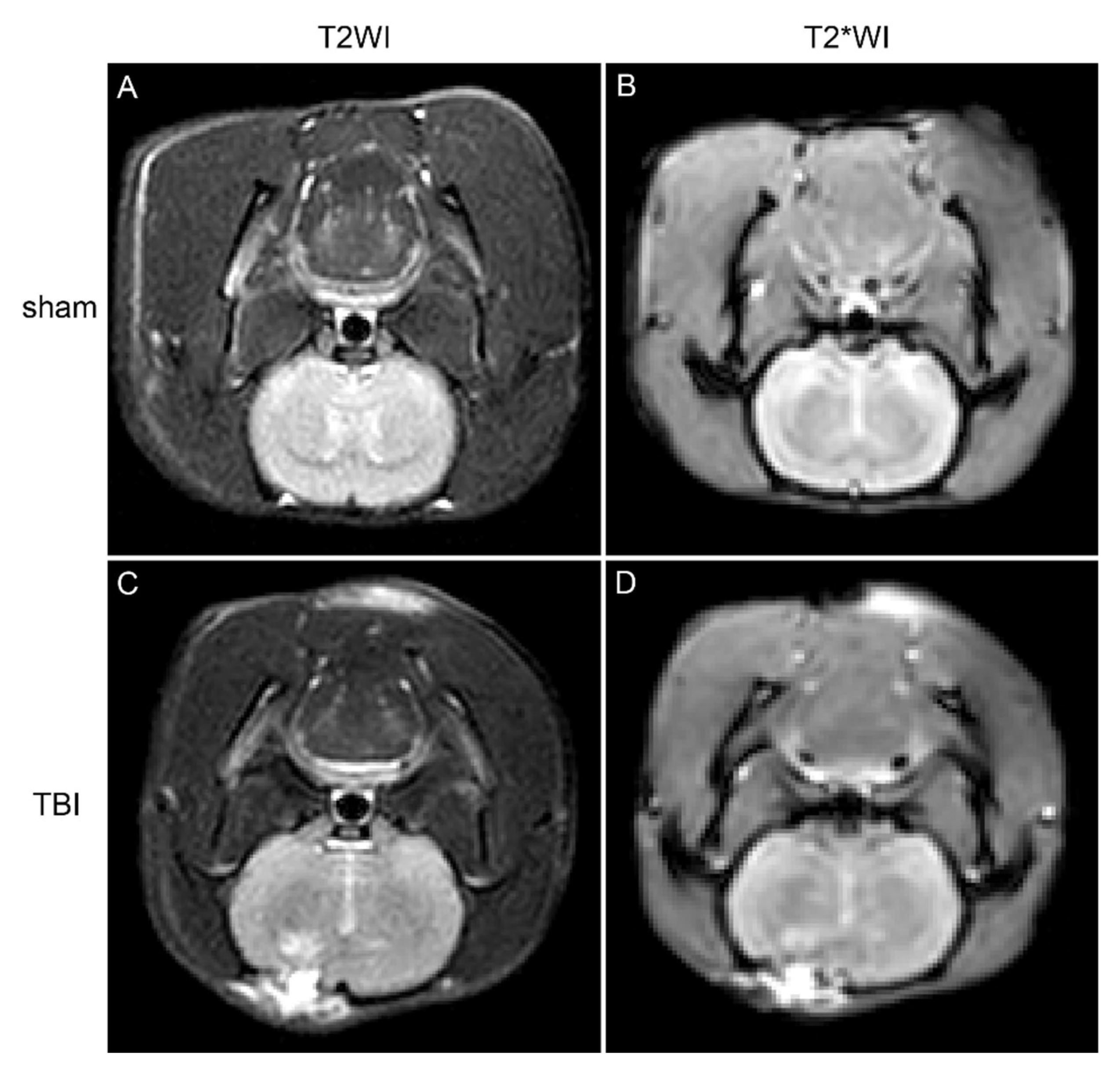

Seven days following the induction of TBI, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was conducted on the rats. In comparison to the sham group, the brain tissue within the injury region of the TBI cohorts exhibited elevated signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) sequences, indicative of brain injury, edema, and hemorrhagic events (

Figure 1). Furthermore, diminished signal intensity was noted on T2*WI sequences surrounding the injury site, implying potential iron accumulation within the brain tissue (

Figure 1).

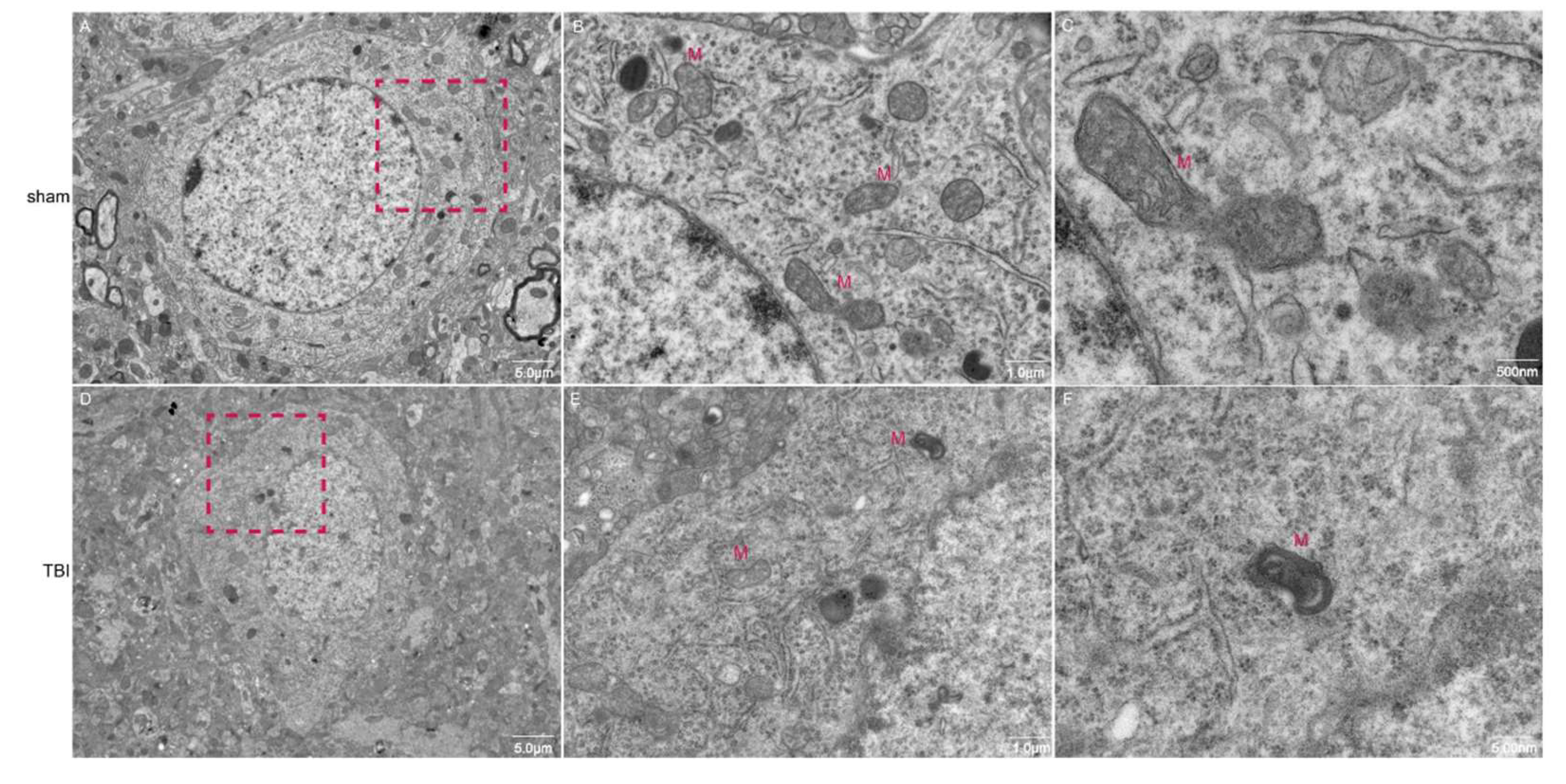

3.2. TEM Demonstrates Evidence of Ferroptosis in Neurons of TBI Rats

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to examine the morphology of neuronal mitochondria. The findings revealed that neurons in the sham group displayed normal morphology, characterized by intact mitochondrial membranes and a typical cristae structure. Conversely, neurons in the TBI group exhibited pronounced morphological alterations, including mitochondrial atrophy, intensified matrix coloration, membrane thickening, and instances of outer membrane rupture, accompanied by both expansion and reduction of internal cristae (

Figure 2). These observations suggest the occurrence of ferroptosis in the neurons of the TBI group.

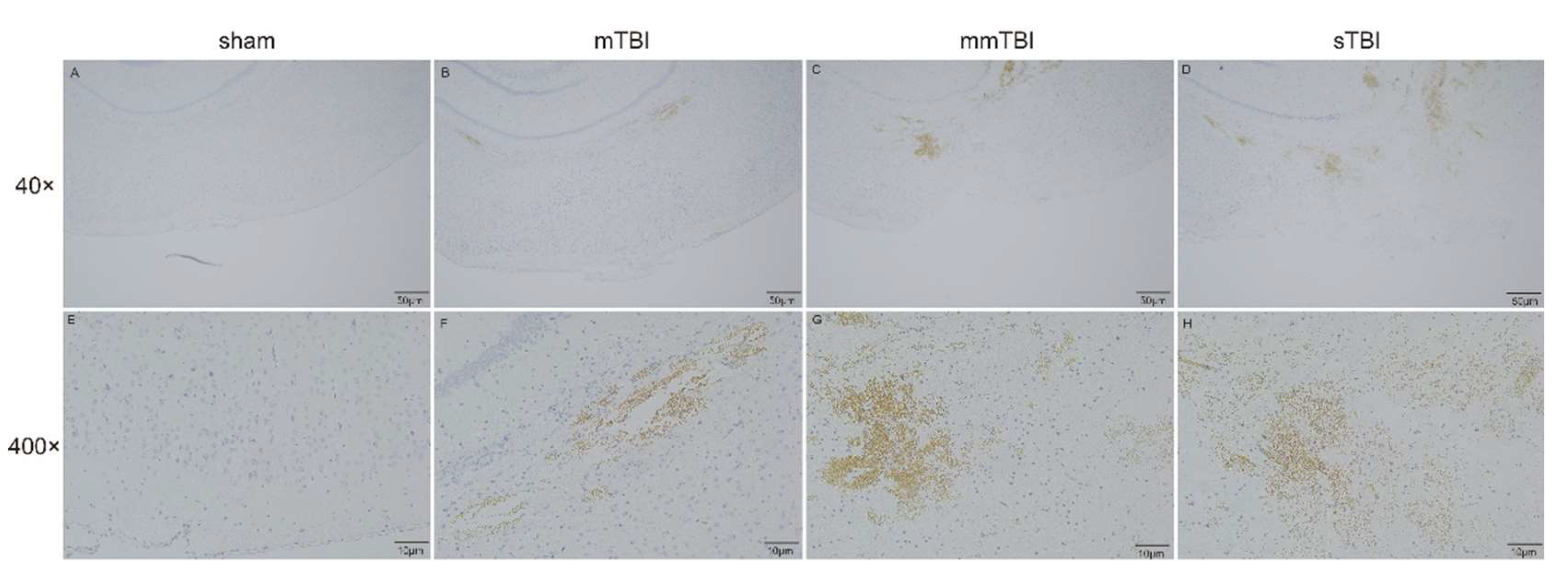

3.3. Prussian Blue Staining Indicates Iron Deposition in the Cortex of TBI Rats

Prussian blue staining was utilized to identify non-heme iron deposition in the cortical tissue surrounding the injury sites in TBI rats. No iron deposition was detected in the sham group. In the mild TBI (mTBI) group, slight iron deposition (brown regions) was observed in the cortex adjacent to the injury site. In the moderate TBI (mmTBI) and severe TBI (sTBI) groups, progressively elevated levels of iron deposition were noted, with the sTBI group exhibiting the most pronounced iron accumulation (

Figure 3).

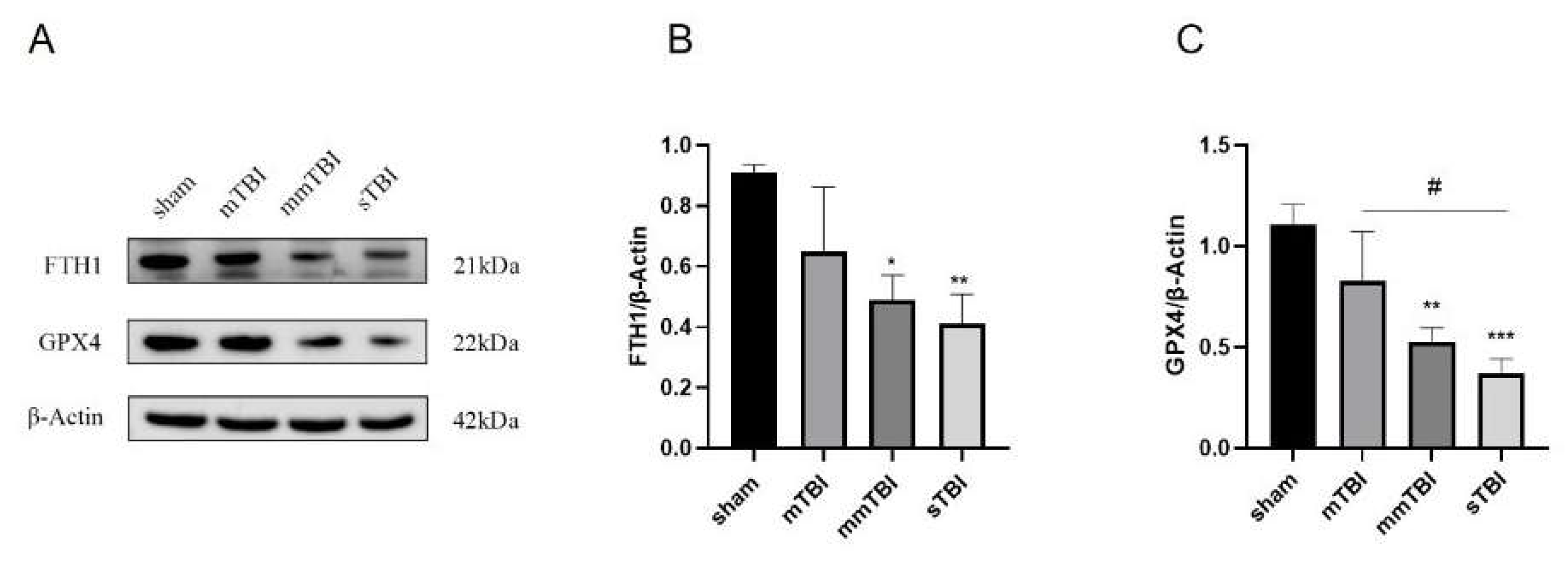

3.4. Reduced Expression of Ferroptosis Negative Regulators in the Cortex Correlates with Increased Neurological Damage

Twenty-four hours post-TBI induction, the expression levels of ferroptosis negative regulators FTH1 and GPX4 in the cortical tissue surrounding the injury area were evaluated via Western blot analysis. Relative to the sham group, the expression levels of FTH1 and GPX4 exhibited a decreasing trend in the mTBI group, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, the mmTBI and sTBI groups demonstrated a significant reduction in the expression levels of FTH1 and GPX4 compared to the sham group (P < 0.05). Additionally, GPX4 expression in the sTBI group was significantly lower than that in the mTBI group (P < 0.05) (

Figure 4).

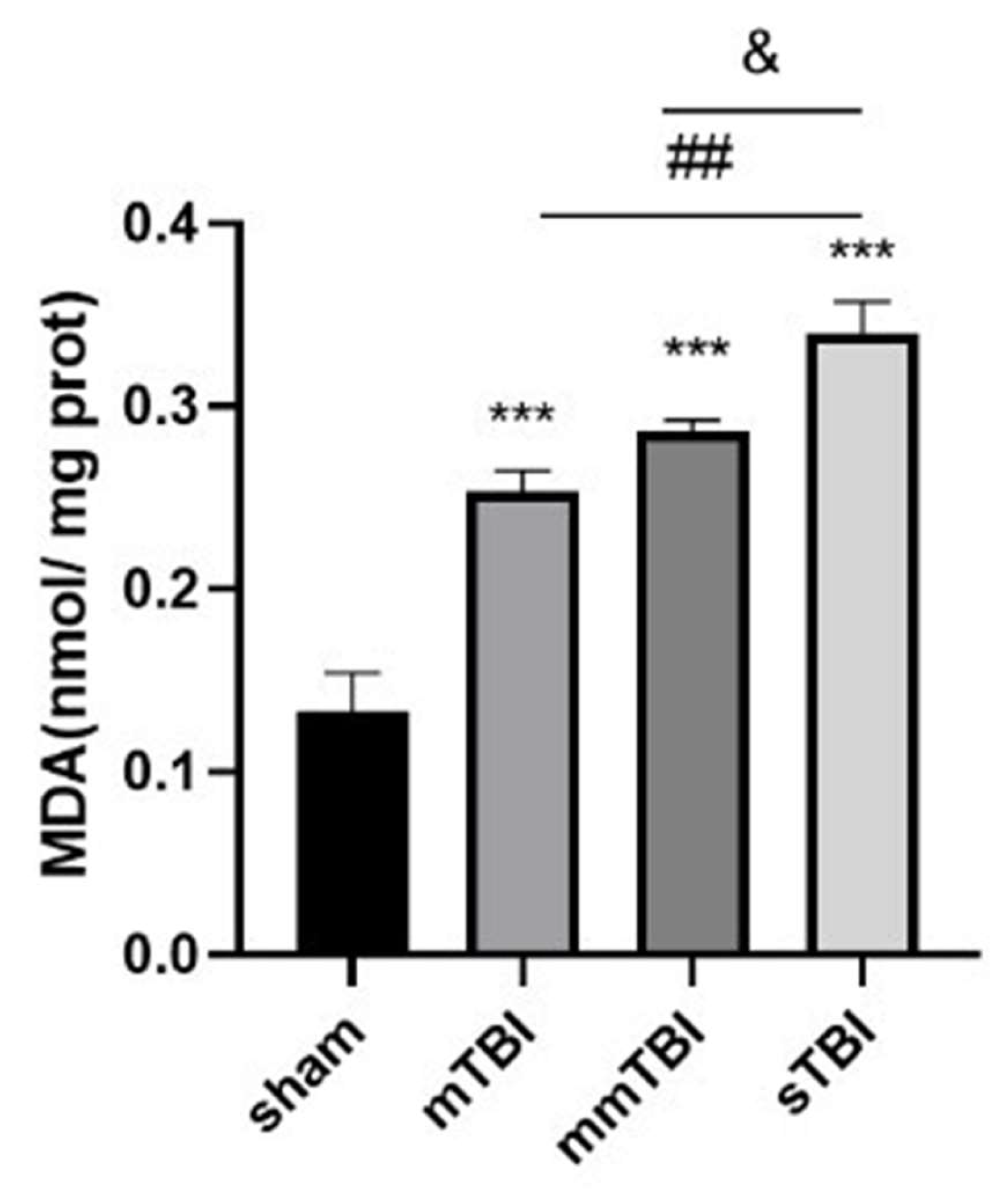

3.5. Elevated Lipid Peroxidation in the Cortex Correlates with Enhanced Neurological Damage

Twenty-four hours following TBI, malondialdehyde (MDA), a biomarker indicative of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, was quantified in the cortical tissue adjacent to the injury site. In comparison to the sham group, MDA concentrations were markedly increased in the mild TBI (mTBI), moderate TBI (mmTBI), and severe TBI (sTBI) cohorts (P < 0.001). A trend towards heightened MDA levels was observed in the mmTBI group relative to the mTBI group, with MDA concentrations significantly elevated in the sTBI group when compared to both the mmTBI and mTBI groups (P < 0.05) (

Table 1,

Figure 5).

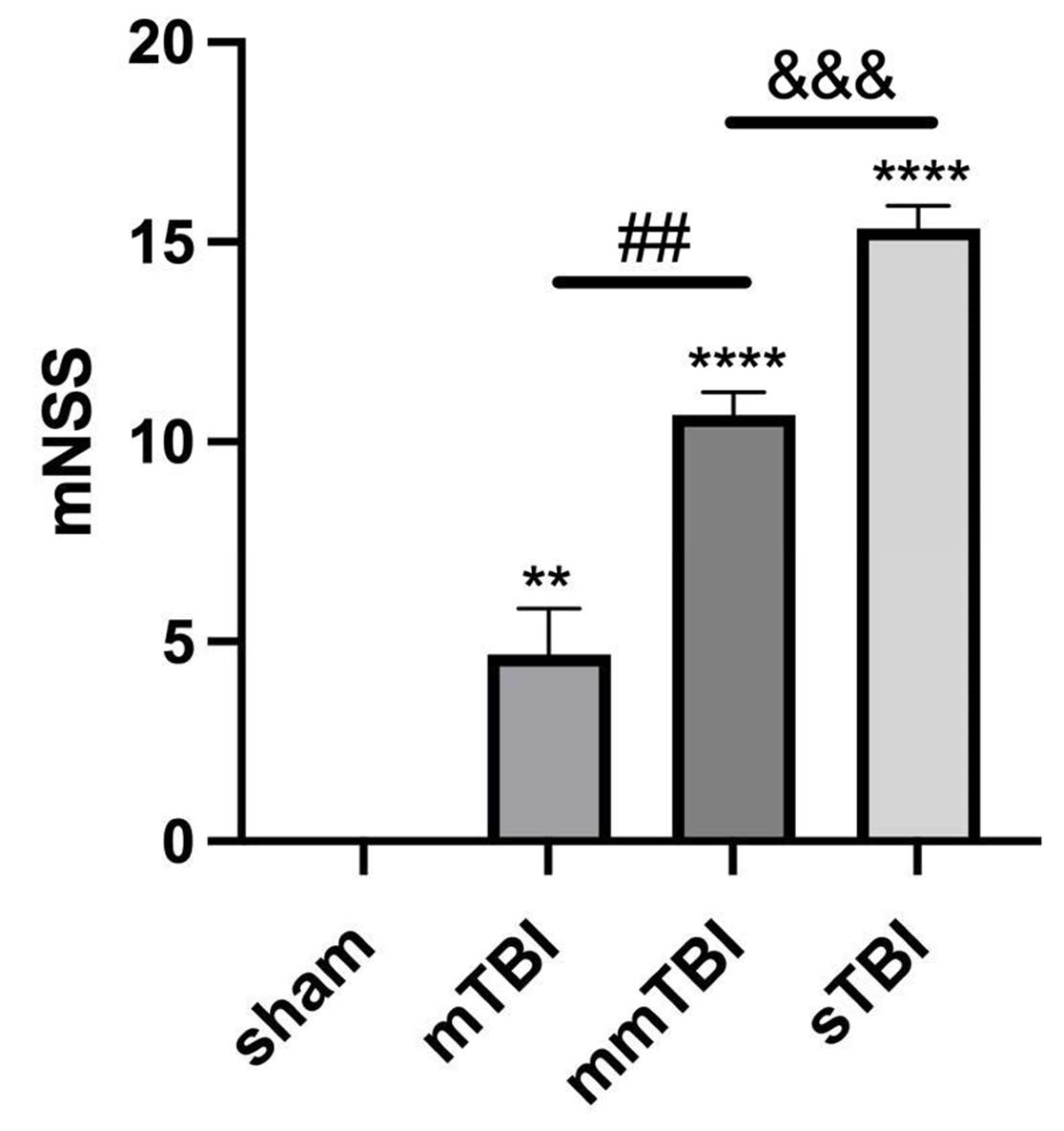

3.6. Increased mNSS Scores Correlate with Increased Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress

Twenty-four hours post-TBI, neurological function was evaluated utilizing the modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) scale. The mNSS scores, reflecting neurological deficits, were significantly elevated in the mTBI, mmTBI, and sTBI groups compared to the sham group (P < 0.001) (

Table 2,

Figure 6).

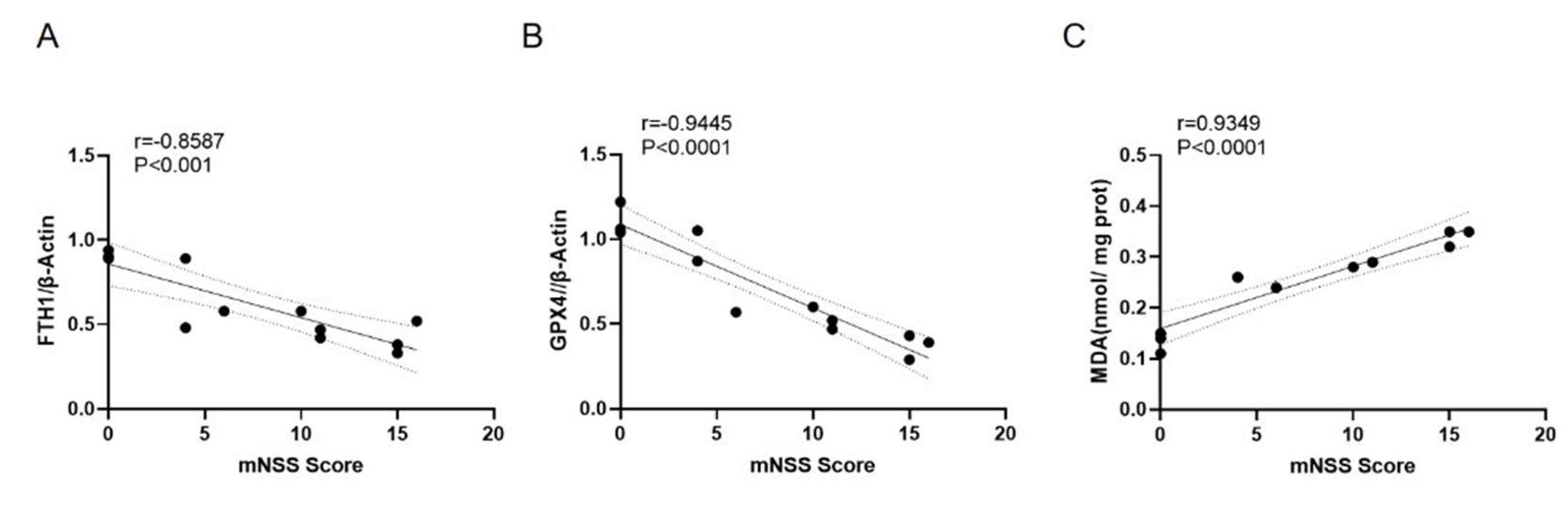

Correlation analysis showed a significant negative correlation between mNSS scores and the relative expression levels of the ferroptosis negative regulators FTH1 and GPX4 (r = -0.8587 and -0.9445, P < 0.001), and a significant positive correlation between mNSS scores and MDA content (r = 0.9349, P < 0.0001) (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

TBI represents a predominant cause of mortality and morbidity globally, particularly among young adults, and imposes considerable economic and societal challenges. The principal etiologies of TBI encompass vehicular collisions, falls from elevations, violent assaults, and slip-and-fall incidents. TBI can be classified into primary and secondary injuries based on the timing and nature of the insult. Primary injury arises from external mechanical forces that inflict immediate and irreversible damage to cerebral structures, including disruption of the blood-brain barrier, axonal injury, and neuronal apoptosis. Current clinical interventions for TBI predominantly focus on decompressive craniectomy and hypothermia therapy; however, these approaches primarily address acute concerns and do not substantially mitigate mortality and disability rates.

Secondary injury pertains to a cascade of biochemical alterations that ensue following primary injury, resulting in additional tissue damage. Historically, it was posited that secondary injury involved mechanisms such as excitotoxicity due to glutamate release, oxidative stress from the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), inflammatory cascades instigated by cytokines and chemokines, vasogenic and cytotoxic edema leading to cerebral swelling, blood-brain barrier compromise, and mitochondrial dysfunction resulting in aberrant energy metabolism [

12]. These mechanisms have been rigorously investigated to pinpoint potential therapeutic targets. Nevertheless, clinical strategies aimed at these pathways have demonstrated limited efficacy in halting the progression of TBI.

Ferroptosis, a recently identified form of regulated cell death, was first described in 2012 by Dixon et al. It is characterized as a programmed, non-apoptotic form of cell death marked by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products and iron deposition. Research has indicated that the ferroptosis pathway is activated post-TBI and contributes to neuronal cell death. In 2017, ferroptosis was first documented in central nervous system tumor models, and subsequent studies have reported its occurrence in animal models of stroke and spinal cord injury. Ferroptosis is distinct from other cell death modalities, such as apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy, in that it is not inhibited by conventional inhibitors of these pathways but can be attenuated by antioxidants and iron chelators [

13].

In this investigation, we sought to elucidate the role of ferroptosis in TBI and its relationship with the severity of neurological deficits. Utilizing a rat model of TBI, we induced brain injuries of varying severities and evaluated iron deposition, ferroptosis markers, and neurological function. The results revealed that iron deposition and ferroptosis were present in the cortical tissue of TBI rats and correlated with the extent of neuronal damage. Our findings bolster the hypothesis that ferroptosis is a pivotal contributor to secondary injury following TBI and that its severity is directly linked to the degree of neurological impairment [

14].

Iron is a crucial trace element that plays a vital role in numerous physiological and biochemical processes, such as oxygen transport, DNA synthesis, and energy metabolism [

15]. However, the accumulation of excess iron is a significant factor that can initiate ferroptosis [

16]. Typically, extracellular iron ions associate with transferrin receptors and are internalized by cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Within endosomes, iron is reduced to ferrous ions (Fe

2+) and subsequently transported into the cytosol, where it is either stored in the labile iron pool or sequestered within ferritin complexes. Under physiological conditions, iron homeostasis is meticulously regulated to avert oxidative damage. Nevertheless, in scenarios such as TBI, disrupted cellular metabolism and hypoxia can result in the excessive accumulation of ferrous ions, which catalyze the Fenton reaction, producing highly reactive hydroxyl radicals. These radicals instigate lipid peroxidation, compromising cell membranes and ultimately leading to cell death.

Our MRI findings demonstrated that TBI-induced brain tissue damage and iron deposition were apparent seven days post-injury. This observation was corroborated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which illustrated mitochondrial atrophy, membrane thickening, and rupture in neurons—hallmarks of ferroptosis. Prussian blue staining further validated that iron accumulation escalated with the severity of brain injury. These results underscore the significant role of ferroptosis in TBI-related neuronal damage and highlight the close association between iron deposition and the extent of injury.

Lipid peroxidation serves as a defining characteristic of ferroptosis, marked by the accumulation of lipid ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA), a byproduct of lipid peroxidation [

17]. In this investigation, we observed that MDA levels were markedly elevated in the cortical tissue of TBI rats, with a positive correlation between the severity of TBI and MDA levels. This finding suggests that oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation are pivotal contributors to ferroptosis in the context of TBI.

Ferroptosis is modulated by critical proteins, including ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). FTH1 is essential for iron storage and detoxification, sequestering excess iron to prevent iron-mediated oxidative damage. GPX4 is a crucial enzyme that safeguards cells from lipid peroxidation by converting lipid hydroperoxides into non-toxic lipid alcohols [

18]. In our study, we noted a significant reduction in the expression levels of FTH1 and GPX4 in the brain tissue of TBI rats, particularly in those with more severe injuries. This decline in FTH1 and GPX4 expression indicates that the protective mechanisms against ferroptosis are compromised in TBI, resulting in heightened oxidative stress and neuronal death.

The modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) was employed to evaluate the extent of neurological impairment in TBI rats. The mNSS scores were significantly elevated in rats with more severe injuries, reflecting greater neurological dysfunction. Correlation analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between mNSS scores and the expression levels of FTH1 and GPX4, alongside a positive correlation between mNSS scores and MDA levels. These findings further substantiate the hypothesis that ferroptosis contributes to neurological deficits following TBI and that the severity of ferroptosis is closely linked to the degree of brain injury [

19].

5. Conclusions

In summary, this investigation elucidates the significant role of ferroptosis in secondary brain injury subsequent to TBI. The processes of iron accumulation, lipid peroxidation, and the downregulation of ferroptosis inhibitors such as FTH1 and GPX4 are intricately linked to the severity of neuronal damage and the degree of neurological dysfunction. Targeting ferroptosis may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for attenuating neuronal loss and enhancing clinical outcomes in TBI patients. Additional research is warranted to identify potential interventions that can modulate ferroptosis and alleviate its impact on cerebral injury.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

LY: conceived and designed the experiments, Writing review and editing. JL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HZ and YY: Investigation, Methodology, and Validation. XZ and QZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. CQ: Investigation. HW and QD: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82260384); Science and Technology Plan Project of Yunnan Science and Technology Department (202301AU070164); Doctoral Research Fund Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (2022BS026); Scientific Research Fund Project of Yunnan Provincial Department of Education(2023Y0597).

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reddi, S.; Thakker-Varia, S.; Alder, J.; Giarratana, A.O. Status of precision medicine approaches to traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res 2022, 17, 2166-2171. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, B.; Peplow, P.V. Biomaterial and tissue-engineering strategies for the treatment of brain neurodegeneration. Neural Regen Res 2022, 17, 2108-2116. [CrossRef]

- Scarboro, M.; McQuillan, K.A. Traumatic Brain Injury Update. AACN Adv Crit Care 2021, 32, 29-50. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.A.; Abbas, A.Y.; Imam, M.U.; Saidu, Y.; Bilbis, L.S. Efficacy of stem cell secretome in the treatment of traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Mol Neurobiol 2022, 59, 2894-2909. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zheng, J.; Fan, Y.; Wu, J. TI: NLRP3 Inflammasome-Dependent Pyroptosis in CNS Trauma: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 821225. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060-1072. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Fan, Z.; Rauh, M.; Buchfelder, M.; Eyupoglu, I.Y.; Savaskan, N. ATF4 promotes angiogenesis and neuronal cell death and confers ferroptosis in a xCT-dependent manner. Oncogene 2017, 36, 5593-5608. [CrossRef]

- Alim, I.; Caulfield, J.T.; Chen, Y.; Swarup, V.; Geschwind, D.H.; Ivanova, E.; Seravalli, J.; Ai, Y.; Sansing, L.H.; Ste Marie, E.J.; et al. Selenium Drives a Transcriptional Adaptive Program to Block Ferroptosis and Treat Stroke. Cell 2019, 177, 1262-1279.e1225. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, E.M.; Fidan, E.; Yang, Q.; Anthonymuthu, T.S.; New, L.A.; Meyer, E.A.; Wang, H.; Kochanek, P.M.; Dixon, C.E.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis Contributes to Neuronal Death and Functional Outcome After Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care Med 2019, 47, 410-418. [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.S.; Wang, Y.Q.; Lin, Y.; Mao, Q.; Feng, J.F.; Gao, G.Y.; Jiang, J.Y. Inhibition of ferroptosis attenuates tissue damage and improves long-term outcomes after traumatic brain injury in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019, 25, 465-475. [CrossRef]

- Roth, T.L.; Nayak, D.; Atanasijevic, T.; Koretsky, A.P.; Latour, L.L.; McGavern, D.B. Transcranial amelioration of inflammation and cell death after brain injury. Nature 2014, 505, 223-228. [CrossRef]

- Sulhan, S.; Lyon, K.A.; Shapiro, L.A.; Huang, J.H. Neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier disruption following traumatic brain injury: Pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. J Neurosci Res 2020, 98, 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.F.; Zou, T.; Tuo, Q.Z.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Belaidi, A.A.; Lei, P. Ferroptosis: mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 49. [CrossRef]

- Geeraerts, T.; Velly, L.; Abdennour, L.; Asehnoune, K.; Audibert, G.; Bouzat, P.; Bruder, N.; Carrillon, R.; Cottenceau, V.; Cotton, F.; et al. Management of severe traumatic brain injury (first 24hours). Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2018, 37, 171-186. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem Biol 2008, 15, 234-245. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Monian, P.; Quadri, N.; Ramasamy, R.; Jiang, X. Glutaminolysis and Transferrin Regulate Ferroptosis. Mol Cell 2015, 59, 298-308. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.L.; Huang, Z.J.; Lin, Z.T.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 88. [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Feng, Y.; Zandkarimi, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kim, J.; Cai, Y.; Gu, W.; Stockwell, B.R.; Jiang, X. Ferroptosis surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by sex hormones. Cell 2023, 186, 2748-2764.e2722. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, D.; Church, D.F.; Torbati, D.; Carey, M.E.; Pryor, W.A. Oxidative stress following traumatic brain injury in rats. Surg Neurol 1997, 47, 575-581; discussion 581-572. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Coronal MRI scans of rat brain tissue, with images A and B depicting the sham group (T2WI and T2WI sequences), and images C and D illustrating the TBI group (T2WI and T2WI sequences).

Figure 1.

Coronal MRI scans of rat brain tissue, with images A and B depicting the sham group (T2WI and T2WI sequences), and images C and D illustrating the TBI group (T2WI and T2WI sequences).

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopy images of neurons. Images A-C represent sham group neurons, and images D-F represent neurons from the TBI group. The scale bars in A, D are 5.0 μm; in B, E, 5.0 μm; in C, F, 500 nm.

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopy images of neurons. Images A-C represent sham group neurons, and images D-F represent neurons from the TBI group. The scale bars in A, D are 5.0 μm; in B, E, 5.0 μm; in C, F, 500 nm.

Figure 3.

Prussian blue staining images showing iron deposition in the cortical tissue surrounding the injury area. Images A, E represent the sham group, B, F the mTBI group, C, G the mmTBI group, and D, H the sTBI group. The scale bars in A-D are 50 μm, and in E-H are 10 μm.

Figure 3.

Prussian blue staining images showing iron deposition in the cortical tissue surrounding the injury area. Images A, E represent the sham group, B, F the mTBI group, C, G the mmTBI group, and D, H the sTBI group. The scale bars in A-D are 50 μm, and in E-H are 10 μm.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of ferroptosis negative regulators FTH1 and GPX4 in the cortex of TBI rats. A: Immunoblot showing protein levels; B, C: Relative quantification of FTH1 and GPX4 protein expression. *P < 0.05 vs. sham, **P < 0.01 vs. sham, #P < 0.05 vs. mTBI.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of ferroptosis negative regulators FTH1 and GPX4 in the cortex of TBI rats. A: Immunoblot showing protein levels; B, C: Relative quantification of FTH1 and GPX4 protein expression. *P < 0.05 vs. sham, **P < 0.01 vs. sham, #P < 0.05 vs. mTBI.

Figure 5.

MDA levels in the cortical tissue of TBI rats. ***P < 0.001 vs. sham, ##P < 0.01 vs. mTBI, &P < 0.05 vs. mmTBI.

Figure 5.

MDA levels in the cortical tissue of TBI rats. ***P < 0.001 vs. sham, ##P < 0.01 vs. mTBI, &P < 0.05 vs. mmTBI.

Figure 6.

mNSS scores in TBI rats. **P < 0.01 vs. sham, ****P < 0.0001 vs. sham, ##P < 0.01 vs. mTBI, &&&P < 0.001 vs. mmTBI.

Figure 6.

mNSS scores in TBI rats. **P < 0.01 vs. sham, ****P < 0.0001 vs. sham, ##P < 0.01 vs. mTBI, &&&P < 0.001 vs. mmTBI.

Figure 7.

Correlation between mNSS scores and the relative expression levels of ferroptosis markers in the cortex of TBI rats. A: Correlation between mNSS score and FTH1 protein expression; B: Correlation between mNSS score and GPX4 protein expression; C: Correlation between mNSS score and MDA levels.

Figure 7.

Correlation between mNSS scores and the relative expression levels of ferroptosis markers in the cortex of TBI rats. A: Correlation between mNSS score and FTH1 protein expression; B: Correlation between mNSS score and GPX4 protein expression; C: Correlation between mNSS score and MDA levels.

Table 1.

Changes in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in cortical tissue (nmol/mg prot).

Table 1.

Changes in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in cortical tissue (nmol/mg prot).

| Group |

MDA (nmol/mg prot) |

| sham |

0.13±0.02 |

| mTBI |

0.25±0.01 |

| mmTBI |

0.29±0.01 |

| sTBI |

0.34±0.02 |

Table 2.

Modified Neurological Severity Scores (mNSS).

Table 2.

Modified Neurological Severity Scores (mNSS).

| Group |

mNSS |

| sham |

0.00±0.00 |

| mTBI |

4.67±1.15 |

| mmTBI |

10.67±0.58 |

| sTBI |

15.33±0.58 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).