Introduction

Issues relating to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) have for some decades remained a great public health concern. In other to reduce the prevalence of resistance in bacterial isolates and the risk of infection in human and animal, the potential mechanisms and the forces that drive the spread of the genes encoding antimicrobial resistance between bacteria needs to be well understood. New resistance genes acquisition is a phenomenon that frequently occurs naturally among bacterial isolates from humans, animals and even the environments; this was delineated in the model referred to as ‘’epidemiology of AMR’’ [

1] where

some insight into potential horizontal gene transfer events of antimicrobial resistance genes between

E.

coli and

Salmonella species was provided.

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella species are bacterial pathogens responsible for foodborne infections and gastrointestinal diseases in human and animals, respectively [

2].

Escherichia coli are genetically diverse strains that are both commensals and pathogenic, while

Salmonella enterica, for example, are enteric pathogens. These two bacterial species are closely related as they share approximately 85% common genomes at nucleotide level [

3]. Infections due to

Salmonella are serious public health challenge that goes along with substantial social and economic effect. Many of the animal species such as chickens, pigeons and reptiles are potential reservoirs of

Salmonella species from which human can be infected through the food chain. The young and the immunocompromised individuals belongs to the high risk group and, if exposed, could lead to dangerous complications which will requires treatment with antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones and extended-spectrum cephalosporins generally used in veterinary medicine [

4].

The purpose of using antimicrobial in poultry industries is for the improvement of animal health, their welfare and production as well as preventing and treatment of animal disease, thereby reducing mortality rate. However, this usage could lead to AMR resistance selection in microorganisms [

5]. Encounter with

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella species that are Multi-Drug Resistant (MDR) could lead to employing the antibiotics of last resort for the treatment of MDR Gram-negative infections. Hence, strains of

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella that are MDR are a major cause clinical worry, especially those that are Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) producers. Another challenge that could be associated with these types of isolates is that in routine susceptibility testing, they are not always being detected ((Mohanty et al.

, 2010). In both the chromosome and plasmids of many of the Gram-negative bacteria like

E. coli and

Salmonella, AmpC-type CMY beta lactamase genes (bla

CMY) has been detected of which CMY-2 is found to be the most common plasmid-carried AmpC-type CMY in

E. coli and

Salmonella species from various regions of the world including the Asia, North America, and Europe [

1].

The ESBL producers are Gram-negative bacteria producing enzymes conferring resistance to most beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins, cephalosporins, and the monobactam aztreonam [

6]. Production of ESBL are noticed mainly among bacteria that belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae which may be habouring a number of antibiotic resistance determinants, thereby resulting in difficulty of treating infections which are due to these kind of pathogens [

6]. The epidemiology of ESBL producers are very complex;

E coli and

Klebsiella pneumonia in the environment (such as soil and water), wild and farm animals, pests and foods are the most prominent bacteria involved in its production. It has also been noted that in some communities, backyard poultry in residential premises may also be a source by which antimicrobial resistant bacteria that produces ESBL in the environment are disseminated [

7].

In Zambia, out of 384 poultry samples analysed, 20.1% of the isolated

E. coli were found to be ESBL producers, out of which 85.7% conferred resistance to beta-lactam and other antimicrobial agents [

8]. This is an indication that poultry may be potential reservoir for ESBL-producing bacteria, including

E. coli Also, in northeastern Algeria, 26.7% of the

Salmonella species isolated from contaminated broiler chicken farms and slaughterhouses were identified as ESBL producers which carried genes such as bla

CTX-M-1, bla

CTX-M-15 and bla

TEM group [

9]. Moreover, in another study carried out in Spain where bacteria producing ESBL were obtained in poultry, the

E coli strains identified carried ESBL genes that included ESBL CTX-M-14, CTX-M- 9, and SHV-12 [

9]. Also in Britain,

E. coli isolated from samples collected form broilers were reported to habour CTX-M gene [

9]. This is an indication that food animals that are colonized with ESBL-producing bacteria can serve as vehicle for its dissemination at the community level [

6]. Antibiotics-resistant

E. coli colonises the intestine of food animals without any form of symptoms manifestation; however, consumption via the food chain by humans can lead to the likelihood of becoming infectious [

10].

In Nigeria, the poultry industry has experienced a remarkable growth in the last few decades; and because of the harsh economic situation in the country, many individuals has ventured into backyard poultry farming and has been increasing within communities. Nevertheless, due to the unhygienic conditions and operations in the poultry farms, there is possibility of poultry infection which may also constitute risk to human health. This scenario has further been complicated by the shortfall of stringent laws guiding the use of antibiotics for human and veterinary care [

11]. In a recent study carried out in Nigeria on poultry birds, ESBL production was detected in 81.6% of the 106 Salmonella ser. Typhimurium (

S. Typhimurium) of which bla

SHV, bla

TEM and bla

TEM-SHV but bla

CTX was not detected [

12], while in Maiduguri, 32% ESBL production was reported among the

E coli from layers [

13]. This study was designed to determine the antibiotics resistance patterns and ESBL production in

E. coli and

Salmonella species isolated from poultry farms across Nigeria.

Study Design and Location

A purposive sampling method was used to collect samples from commercial poultry farms (5 farms from each Local Government Areas: Ibadan North, Akinyele. Lagelu. Egbeda and Ido; n=25). Samples collected include: Boot swabs for litter (n=200); Waste run off water (n=200), fresh faeces (n=200). All samples were collected aseptically into sterile sample bags/bottles and immediately transported on ice to the laboratory for storage at 40C. Analysis of samples was done within 4 hours.

Isolation and Identification of Salmonella Species

Isolation and identification of

Salmonella was carried out according to ISO guidelines [

14]. Boot swabs and environmental swabs were pre-enriched in buffered peptone water (BPW; Oxoid, UK) with a 1:10 dilution then incubated at 37°C for 18-24 hours. A 0.1 ml pre-enriched sample was then added separately to three different locations on Modified Semisolid Rappaport Vassiliadis (MSRV; Oxoid, UK) agar medium and incubated at 41.5°C for 20-24 hours. Further, MSRV-positive samples were streaked into xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD; Oxoid, UK) and incubated overnight at 37°C [

15]. Confirmation was performed by slide-testing isolates using PolyA-S antisera as well as PolyO-H (Prolabs) for motility [

16].

Salmonella isolates were shipped to the UK according to IATA guidelines on charcoal swabs for further testing. The antigenic formula of each strain was then determined using standard methods [

17] and serovar assigned according to the White–Kauffmann–Le Minor scheme [

18].

Isolation and Identification of Escherichia coli

Isolation of E. coli was carried out according to ISO guidelines. The overnight BPW culture was plated out onto MacConkey agar (Thermo Scientific) which was incubated for 18-22 hours at 37°C. Lactose fermenting colonies were then sub-cultured onto Nutrient agar for biochemical testing. Oxidase and indole testing was carried out and oxidase negative/ indole positive isolates were confirmed as E. coli.

A selection of putative E. coli isolates were shipped to the UK on charcoal swabs according to IATA guidelines and cultured onto CHROMagar ECC (CHROMagar) to check for purity. Blue/pale isolates were sub-cultured onto MacConkey (Thermo Scientific) to confirm as lactose-fermenters. Isolates were then sub-cultured onto Nutrient agar (Thermo Scientific) where biochemical tests could be carried out for oxidase and indole. MALDI-ToF was used on isolates where oxidase/indole testing was not conclusive.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution using commercial plates (Sensititre™ EU Surveillance Salmonella/E. coli EUVSEC3 plate, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 2021), according to CLSI and EUCAST guidelines. A suspension of each isolate was prepared to a density of 0.5 McFarland in 5 ml demineralised water, 10µl of the suspension was transferred to 11ml of Mueller Hinton broth to obtain a target inoculum density of between 1 x 10⁵ and 1 x 10⁶ CFU/ml. Fifty microlitres was dispensed into each well of the microtitre plate using a Sensititre AIM and incubated at 35-37 °C for 18 to 22 hours.

15 antimicrobials were tested in this manner (Amikacin, Ampicillin, Azithromycin, Cefotaxime, Ceftazidime, Chloramphenicol, Ciprofloxacin, Colistin, Gentamicin, Meropenem, Nalidixic Acid, Sulfamethoxazole, Tetracycline, Tigecycline and Trimethoprim). Isolates presenting with an AmpC/ESBL resistance phenotype were further tested using the commercially available EUVSEC2 plate, which tests 10 antimicrobials including three from the original EUVSEC3 plate (Cefepime, Cefotaxime, Cefotaxime and Clavulanic acid, Cefoxitin, Ceftazidime, Ceftazidime and Clavulanic acid, Ertapenem, Imepenem, Meropenem and Temocillin). Escherichia coli NCTC 12241 (ATCC 25922) was used as control strain. Susceptibility was assessed using CLSI (2021) Clinical breakpoints and ECOFF values, where clincal breakpoints were not available, EFSA cut-offs or No Interpretation were given. Where isolates presented with phenotypic or resistance genes for three or more antimicrobial classes they were classified as MDR (multidrug resistant).

Whole Genome Sequencing

DNA extracts were prepared from overnight Luria Broth cultures and extracted with the MagMAX™ CORE extraction kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Basingstoke, UK) using the semi-automated KingFisher Flex system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Basingstoke, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted DNA was processed for whole genome sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq platform. The resulting raw sequences were analysed using the Nullabor 2 pipeline (Seemann, 2020), using as reference the published genome

E. coli K12, Spades for genome assembly (version 3.14.1) [

19] and Prokka for annotation (version 1.14.60) [

20]. The presence of genes and point mutations conferring AMR was assessed using AMRFinderPlus [

21]. The Sequence Type (ST) was determined with MLST (version 2.19.0;

https://github.com/tseemann/mlst) using the pubMLST database [

22]. Phylogenetic trees were built using RAX-ML and annotated using iTOL.

Results

A subset of 102 isolates from a collection obtained at poultry farms in Nigeria, consisting of 25 putative Salmonella and 77 putative E. coli, were analysed in this study. These isolates were selected due to their unusual or notable suspected AST profile which was measured by disc diffusion in Nigeria. The AMR Reference Centre provides confirmatory testing of these isolates as well AST determination by broth microdilution assays and WGS analysis.

Salmonella Serotyping Results

All isolates were verified as

Salmonella, except one, and serotyping revealed 12 different serovars for the selection of isolates. The serovars of note are the two Kentucky isolates which have been reported widely around Africa with multidrug resistant (MDR) strains. This is the same ST198 strain, as reported in Igomu, E. [

23] and Fagbamila, et al. [

24]. The most prevalent serovars found was S. Isangi, which has also been reported widely in Nigeria.

S. Poona was not detected in this study, which has previously been found to be the second most prevalent serovar in Nigeria [

24]. No typhoidal

Salmonella were found in this surveillance on poultry farms. All serovars found in this study are shown in

Table 1 along with the percentage of occurrence in this study.

Salmonella AST Results

Of the 24 confirmed Salmonella, 7 isolates were fully susceptible and had no resistance genes, these were the two Dugbe’s and five Isangi serovars. The antimicrobial class with the highest prevalence of resistance was the quinolones with 71% of isolates having resistance to Ciprofloxacin and Nalidixic Acid. 21% of isolates have a high level of resistance to Sulfamethoxazole, with a further 16% having a low level of resistance. And 25% of isolates were resistant to Tetracycline, which is lower than what would be expected. 21% of isolates have resistance to Gentamycin. Three isolates have resistance to Ampicillin, and one isolate had resistance to Chloramphenicol. This resistance could not be verified by genotypic analysis, and no genes could be found to account for the Chloramphenicol resistance.

None of the

Salmonella isolates had resistance to Amikacin, Azithromycin, Cephalosporins (2nd – 4th generation), Colistin, Meropenem, Tigecycline and Trimethoprim. There was absence of Trimethoprim, chloramphenicol and Colistin resistance. The MIC results for the Salmonella can be found in

Table 2, where isolate resistances were grouped. Ciprofloxacin had the largest differentiation with MIC values differing by 8 doubling dilutions between sensitive isolates and resistant isolates depending on what genes were present.

Salmonella WGS Results

There was a 98.7% correspondence between the observed phenotype, and the WGS genotype. This does not include the four isolates with low levels of resistance to Sulfamethoxazole.

Only four of the

Salmonella isolates were multidrug resistant (MDR) (resistant to three or more antimicrobial classes), of which two were the Kentucky ST198 strain. The Kentucky isolates were the only

Salmonella with

gyrA and

parC mutations, associated with

resistant to fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and ciprofloxacin. All other serovars with quinolone resistance have acquired

qnrB and

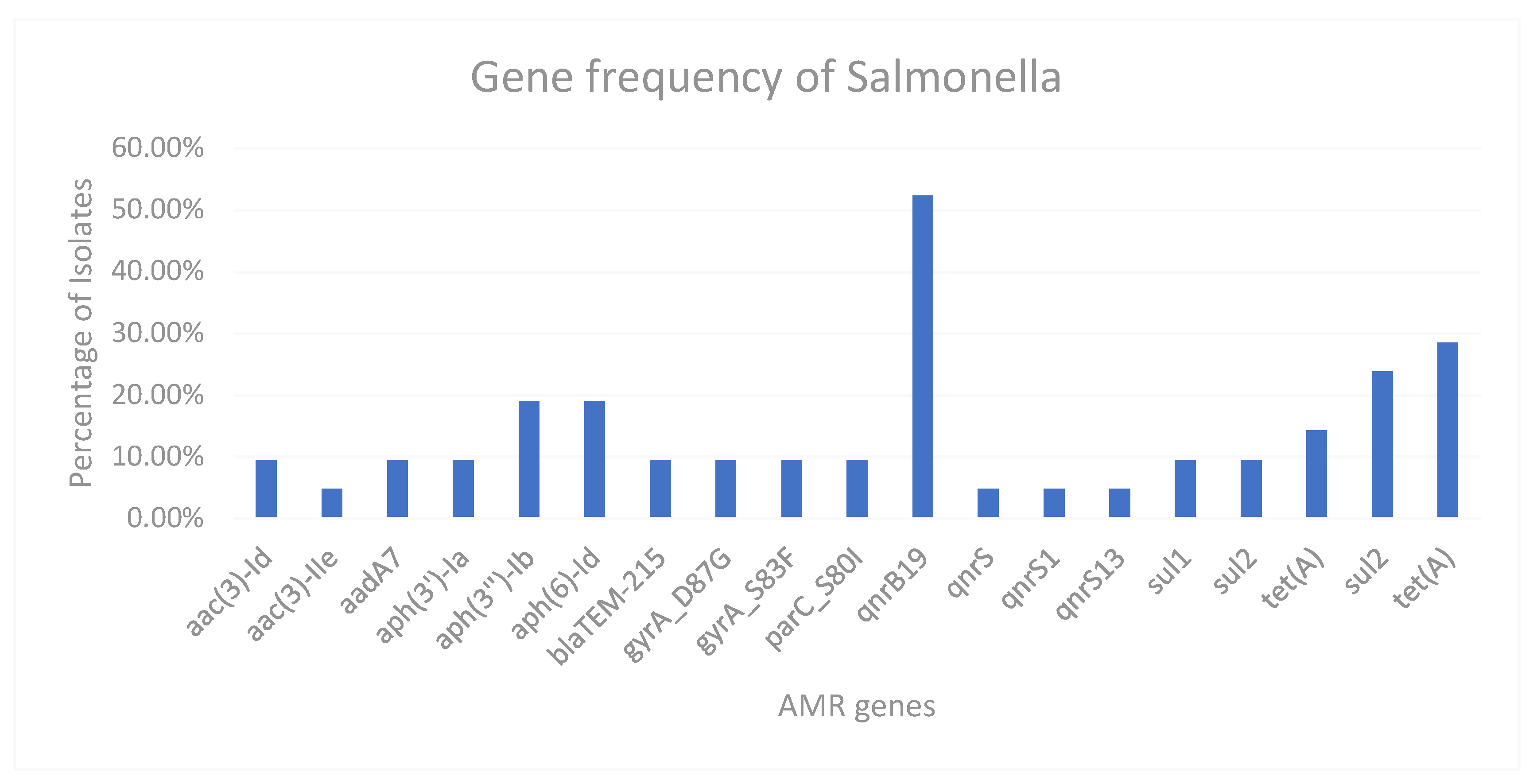

qnrS genes. The prevalence of genes is detailed in

Figure 1 and over 50% of the Salmonella isolates expressed the qnrB19 gene.

There were no unusual resistance genes found in the Salmonella, the resistances observed were in line with what has been previously observed in Nigeria in poultry farms. Pheno/Geno analysis confirmed that no genes conferring resistance to Cephalosporins or Carbapenems were detected and this correlated with the AST data.

Salmonella Plasmid Findings

Despite many of the Salmonella isolates being fully susceptible, 18/21 isolates have acquired at least one plasmid. Most of the plasmids found were Col440I, or Col-RNAI, which can be found in 16 of the 18 isolates with plasmids. Plasmids of note are IncN found in 2 isolates, both of which are MDR. IncBOKZ was also found but this isolate only possesses qnr genes which confer resistance to the quinolones.

E. coli AST Results

There was a much higher resistance frequency in the E. coli compared to the Salmonella. Over 80% of isolates have resistance to Fluoroquinolones (Ciprofloxacin and Nalidixic Acid) with a similar percentage having resistance to tetracyclines. Also, 41% of isolates have resistance to 3rd generation cephalosporins (ESBL), and 3 isolates have resistance to 4th generation cephalosporins (Cefepime). No isolates had an AmpC phenotype. Furthermore, 77% of isolates had resistance to Ampicillin and 20.8% of isolates have Azithromycin resistance. No isolates had resistance to Amikacin, Colistin, Meropenem or Tigecycline.

The MIC results can be seen below in

Table 3, where the top 15 antibiotic results are from the commercially available EUVSEC3 plates. The second set of results from the 10 antibiotics are from the commercially available EUVSEC2 plate, used for ESBL/AmpC

E. coli or Carbapenem resistant

E. coli. None of the isolates presented with any carbapenem resistance. The MIC distribution for the

E. coli is also far greater than the

Salmonella with a higher prevalence of MDR strains (75%). The ESBL isolates were selected based on the resistances characterised by the Department of Veterinary Public Health and Preventive Medicine in Nigeria, so these results are not being interpreted for scanning surveillance of

E. coli in Nigeria.

E. coli WGS Results

There was a 99.4% correspondence between the observed phenotype, and the genotype from WGS. This infers both phenotypic and genotypical analysis are accurate for the study. This study found over 32% more AMR genes in the E. coli compared to the Salmonella, this includes both chromosomal mutations as well as acquired or plasmid mediated AMR genes.

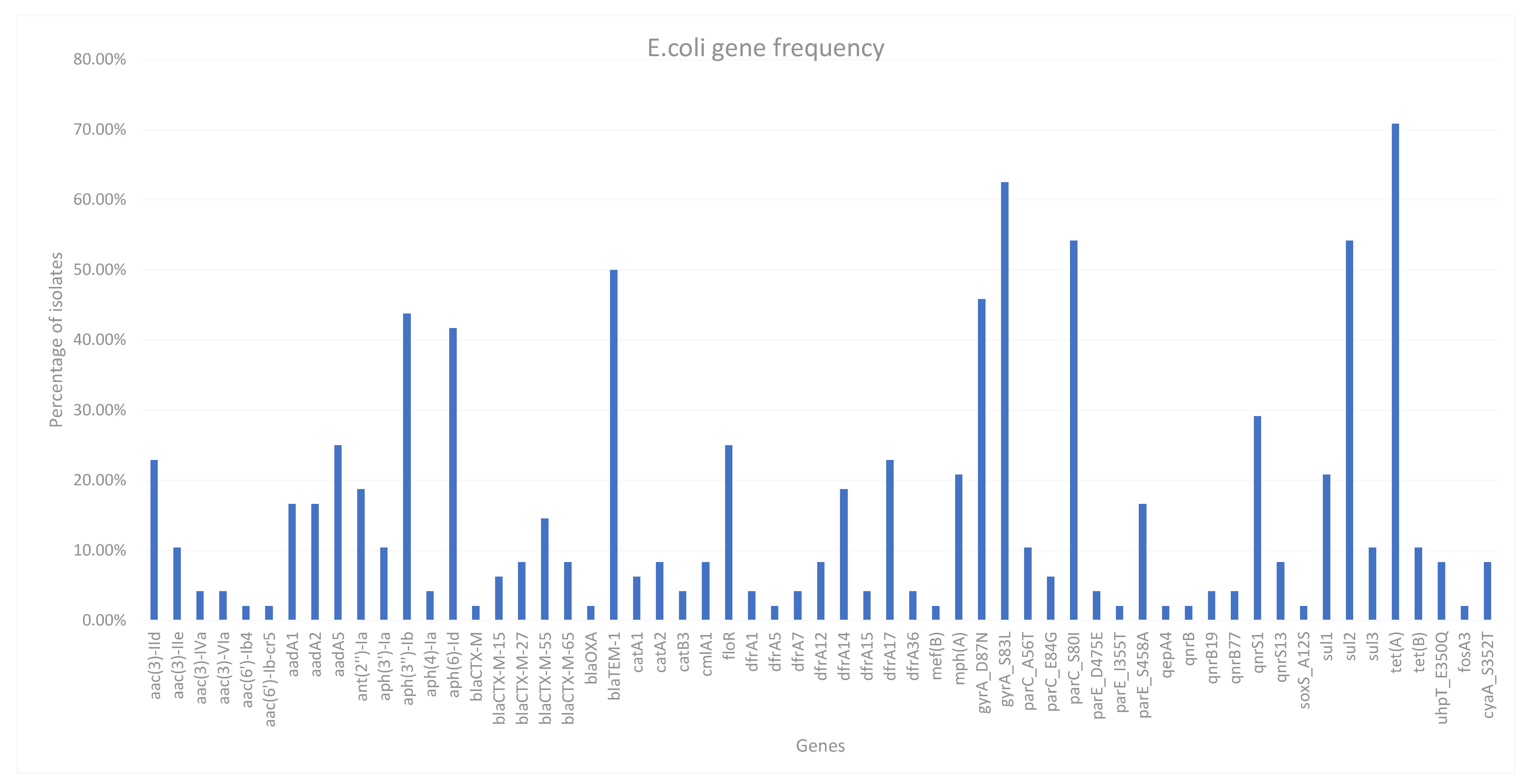

For this panel of isolates, 75% were MDR by WGS. Many resistant genes were found for antimicrobials not tested with our standard surveillance plates, such as Streptomycin and Fosmidomycin. All genes found using AMRfinderPlus can be found in

Figure 2, which also demonstrates the prevalence of the genes found. There is a very high gene diversity, even within antimicrobial classes. There 14 different genes that are associated with quinolone resistance, the most prevalent of which are

gyrA and

parC chromosomal mutations which confer a high level of resistance to both Ciprofloxacin and Nalidixic acid as demonstrated by a high MIC value for isolates with this acquired mutation. The most prevalent gene found was

tet(A) which can be found in over 70% of isolates.

Many of the isolates were also resistant to Sulphonamides, 3 of 4 sul genes being identified (sul1-3) with sul2 being the most frequently identified. aph(3’‘)-Ib and aph(6)-Id were also found in 21 and 20 isolates respectively which are associated with resistance to Streptomycin as well as three aadA genes also conferring resistance to Streptomycin, these genes are very common to find in resistant isolates.

More notable genes are from the 19 ESBL isolates, with four different blaCTX-M genes identified as well as one isolate with blaOXA gene as well as blaCTX-M-15. Two other isolates also have CTX-M-15, four isolates have CTX-M-27, four isolates have CTX-M-65 and the most prevalent CTX-M gene identified was CTX-M-55 with seven isolates. No isolates have multiple CTX-M genes, one isolate has a CTX-M gene which could not be identified by AMRFinderPlus. 50% of isolates including all ESBL E. coli contained a blaTEM-1b gene conferring resistance to Ampicillin.

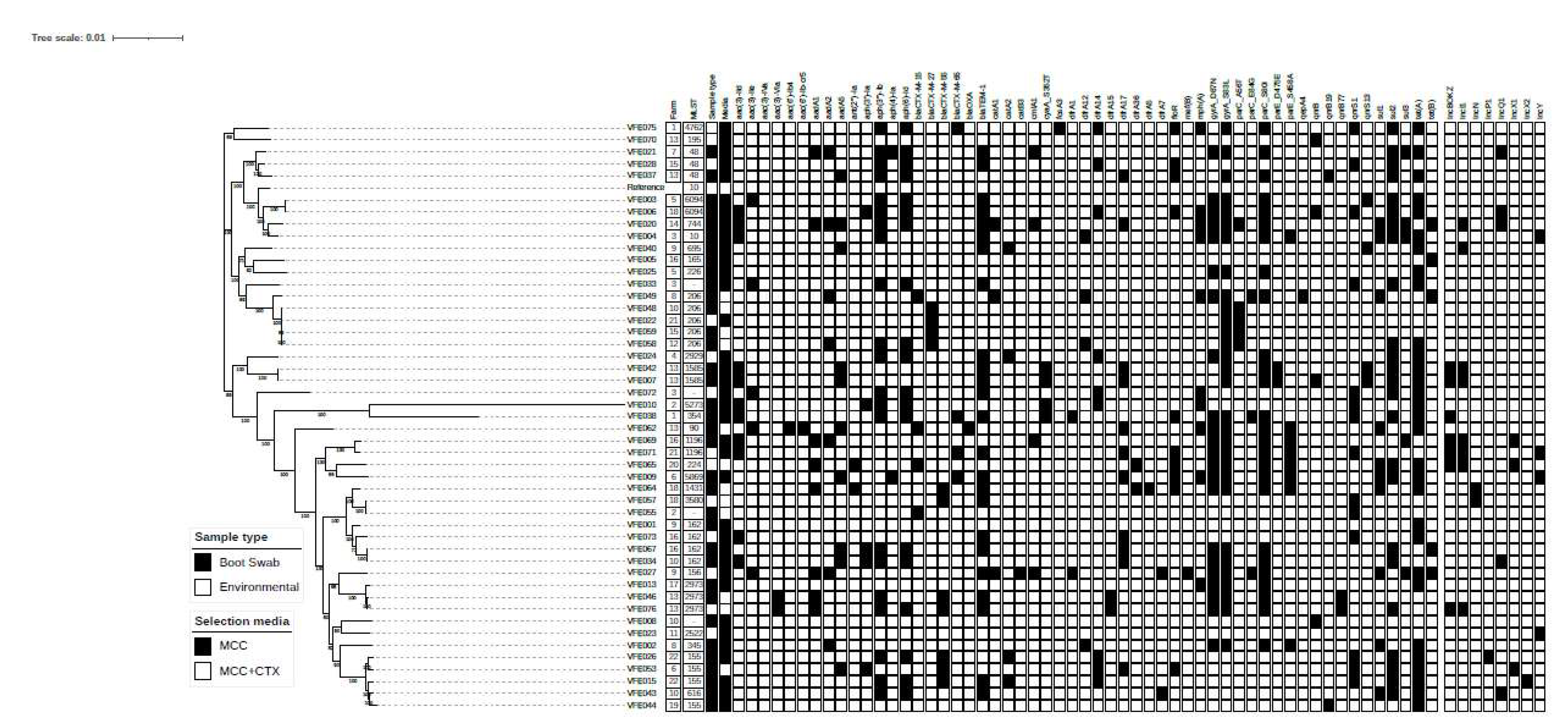

A phylogenetic tree can be seen for the

E. coli isolates in

Figure 3. There are three distinct clades for the isolates, with one small clade of 2 isolates, VFE070 and VFE075 both are from different farms and have different resistance profiles. The second clade contains 16 isolates plus the reference strain. Five (5) isolates have the sequence type 206, 3 of which have the same AMR genes and have a SNP distance of less than 50 which indicates these isolates are clonal. Also, VFE058 and VFE059 have a SNP distance of 7, however VFE058 contains 6 more resistance genes. These isolates all came from different farms.

The third clade has the most diversity as well as the most clonal isolates. VFE010 and VFE038 are the most diverse isolates with a phylogeny very different to all the isolates in this study. The resistance genes these isolates have acquired are not unusual compared to other isolates. VFE010 and VFE055 are from the same farm, with VFE055 not having an identifiable sequence type, but both isolates have very different resistance profiles, with VFE055 being a non MDR ESBL, and VFE010 being MDR and no ESBL genes. The VFE007 and VFE042 are both from the same farm and have the same sequence type. These isolates have a SNP distance of 4 as well as having the same resistance genes making them clonal.

There are several other isolates with the same sequence types, as well as having small SNP distances but have different resistance genes and are mostly from different farms. The VFE015 and VFE026 are both from the same farm and have the same sequence type 155. There resistance genes are also very similar (both ESBL) but have a SNP distance of over 2600. One also contains an IncX2 plasmid, where the other contains an IncP1 plasmid.

Discussion

Bacteria in food-producing animals can be spread through the food chain. In the low income countries especially in Africa, the urge to improve animal production has been the reason for indiscriminate use of antibiotics of which the heavy usage has been identified as one of the factors through which ESBL–producing microorganisms are acquired. This has also been a contributory factor for increase in trend of development of resistance to commonly used antibiotics. In this study, it was contemplated that the use of antibiotics in poultry settings can exacerbate resistance to antibiotics especially in settings where there is low level of antibiotic stewardship and where there is high prevalent of unregulated antibiotic use, such as Nigeria [

25]. This study involved a collection of subset of 102

E. coli and

Salmonella species from different poultry farms across Nigeria. Attention was therefore on

E. coli and

Salmonella because the burden of death due to antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens notably

E. coli and

Salmonella S. Typhimurium is high disproportionately in low- and middle-income countries such as Nigeria, compared to high income countries [

26].

Isolation of these bacterial isolates from poultry farms are in accordance with similar studie. For instance, in Ibadan, they were recovered from poultry meat contaminated from a processing plant and retail markets as well as broiler chicken farms in China [

1]. In the present study, 12 different serovars were identified with

S. Isangi being the most prevalent, while, in a study on broiler chickens, seven serovars were isolated for which Mbandaka predominated [

27]. The Kentucky serovar isolated in this study is of note, because of the assertion that this serotype, Mbandaka and Indiana could be clonally transmitted between broiler farm and slaughterhouse [

27]. Furthermore, in Algeria, the isolated

Salmonella strains belonged to two serovars mainly of Kentucky and Heidelberg [

9] as against 12 in the present study which also included Kentucky. This observation is an evidence of the heterogeneous distribution of serovars in poultry farms.

In order to estimate the scale of the problem and the extent of the penetration of antibiotic resistant strains of these bacteria, we profiled the isolates for resistance to 15 antibiotics, and reported high level of resistance especially of

E. coli to several of the tested antibiotics. For

Salmonella, the absence of Trimethoprim resistance and general absence of chloramphenicol resistance is unusual as both resistances have been well characterised in salmonella from poultry in Nigeria [

28,

29]. The lack of Colistin resistance is noteworthy as MCR (mediated colistin resistance) genes are increasing in prevalence in northern African countries.

It was observed that

S. Typhimurium presented low level resistance, and were for the most part, susceptible. However, this was not the case with

E. coli as 80% were resistant to fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid). The fact that quinolones and fluoroquinolones are vital antibiotics used in the treatment of blood poisoning and other infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria informed the categorization of these agents as veterinary highly important and veterinary critically important antimicrobials, respectively [

30].

Resistance to fluroquinolones in

E. coli is high priority on the WHO’s list of priority pathogens for research and development of new antimicrobials because of its effectiveness in the treatment of Gram-negative pathogens [

31]. It can therefore be summarized that the level of resistance of the

E. coli strains to fluoroquinolones in this study is disturbing. Furthermore, as was the case with fluoroquinolones, so it was with tetracycline where 80% of

E. coli expressed phenotypic resistance. In both human and animal medicine, tetracyclines are highly important antimicrobials [

30,

32] with broad-spectrum activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [

33]. The level of resistance to tetracycline by

E. coli in this study is possibly due to the use of the tetracycline antibiotic as alternative to fluoroquinolones in treatment of infections; this was evidenced in the treatment of campylobacteriosis [

34]. Thus, the resistance observed in this study may not be dissociated from clinical failures of tetracycline in the prevention and control of bacterial infections [

35]. The resistance of

E. coli (83%) in this study to tetracycline is in agreement with the over 80% that was reported by Adeyanju and Ishola [

36]. The ESBL genes detected in this study which showed that bla

CTX-M was the most prevalent is also in agreement with the report of Chishimba et al. [

8].

It suffices that the report of high level of fluoroquinolone resistance in

Enterobacterales such as

E. coli reportedly matched with consistent fluoroquinolone use in Nigeria and even in several parts of Africa [

18]. The current study and that of Afolayan et al. [

37] underscored the fact that resistance to nalidixic acid is presently a common happenstance in Nigeria. It was observed that 41%

E. coli were resistant to 3rd generation cephalosporins with additional

E. coli (n = 3) showing resistance to cefepime, and this highlighted the average incidence and spread of the ESBL resistance phenotype in the poultry sector. Still, the relevance of this study within the purview of the WHO tricycle protocol that used a single key indicator of the prevalence of ESBL producing

E. coli in the interrogation of the dissemination ESBL-

E. coli using the context of One Health is considered. In this circumstance, it can only be truer that food animals are potent reservoir of ESBL-producing

E. coli capable of wide dissemination to humans [

38,

39] as

blaCTX-M,

blaCTX-M-15,

blaCTX-M-27,

blaCTX-M-55 and

blaCTX-M-65 were the only ESBL drivers found in the current study. Thus, we justified the performance of the whole genome sequencing as tool that guarantees the accurate AMR profiling of bacterial species. It might be interesting to recall that resistance to 3rd generation cephalosporin surfaced and started to disseminate much more rapidly in the continent of Africa compared to other part of the world because these antibiotics were the drug of choice for the treatment of infections and diseases caused by MDR pathogens [

40].

The recovery of ESBL-producing

E. coli in this study is comparable with that of Falgenhauer et al. [

41] that described similar strains from humans and poultry in Ghana as was the case with migratory birds in Pakistan [

42]. Moreover, ESBL resistance factors are usually borne on plasmids, and chances are, that the ESBL

blaCTX-M,

blaCTX-M-15,

blaCTX-M-27,

blaCTX-M-55 and

blaCTX-M-65 resistance genes, can easily be acquired by human-associated

E. coli, a prelude to its further dissemination among humans, or these traits can be transferred through horizontal gene transfer to another enterobacteriales such as

Klebsiella pneumoniae, reputed as key trafficker of mobile antimicrobial resistance genes. Either of these snap pictures only makes it worse and thus constitutes a significant threat to the continuous effectiveness of the cephalosporins.

The observation from the present study that showed seven of the

Salmonella isolates being fully susceptible to all the tested antibiotics is in accordance with the report of a study on isolates obtained from broiler chicken farms and slaughter houses from which it was observed that eight of the

Salmonella isolates were also fully susceptible to all the antibiotics they were tested against [

1]. However, 71% of the

Salmonella species that showed resistance to ciprofloxacin in this study is higher than the 51.1% that was reported from another study on

Salmonella species isolated from poultry in northern Algeria [

9]. The reason for the slight disparity might be due to the numbers of isolates involved in the studies. While 77 isolates were used in this study, it was 45 isolates in the latter study. However, a similar resistance of the isolates to gentamycin in both studies which were 21% and 22.2%, respectively was obtained. Similarly, the numbers of

Salmonella species that were MDR (16.6%) in this study is comparably similar to the 16% in the latter study. The observed resistance patterns of the

Salmonella species in this study are at variance with the report of another study on contaminated poultry meat from a processing plant [

36] in Ibadan from which 13%, 33% and 42% were resistant to gentamicin, nalidixic acid and tetracycline, respectively, as against the 21%, 71% and 25%, respectively in this study. The generalised increase in MIC for the quinolones can be attributed to the increase in presence of gyrA and parC chromosomal mutations. These along with qnrS genes lead to a much higher MIC value.

In conclusion, MDR isolates were subsequently identified among E. coli and Salmonella species with ESBL phenotypes. The outcome of the study suggests there are MDR bacteria in the poultry environments with characteristics that potentially could allow their flourishing in the poultry environment. This has further given confirmation that poultry can be potential reservoirs and a means by which ESBL resistant genes can find its way to food chain. Hence, the use of antibiotics in poultry should be properly regulated.