Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The work aimed to analyze the PAH content in products smoked in traditional smokehouses with direct and indirect heat sources and in an industrial way as an element of PAH content monitoring in Polish market products. The research material comprised 12 smoked meats (W) and 38 sausages (K), medium or coarsely minced. The content of benzo(a)pyrene and the total content of 4 marker PAHs was determined by GC-MS. The analysis showed a significantly higher level of PAH contamination in products smoked using traditional methods. The results also indicate that the natural casing is not a barrier against PAH contamination during traditional smoking, and a higher degree of meat fragmentation, together with a small cross-section, increases the PAH content in this technological group. Concentrations of benzo(a)pyrene exceeding the permissible levels were found in the sausages smoked for more than 60 min. As part of the strategies for reducing PAH content, among others, changing the furnace to an indirect one, shortening the time, lowering the smoking temperature, using artificial casings or removing casings before consumption, drying the product surface before the smoking process, using seasoned and bark-free wood, as well as additional smokehouse equipment, are recommended.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Material

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2.2. Sampling for Analysis

2.2.2. PAH Content Analysis

Determination of PAHs Using the GC-MS Method

Qualitative–quantitative PAH analysis

2.2.3. Method Validation

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. PAH Content in Smoked Meats

3.2. PAH Content in Smoked Sausages

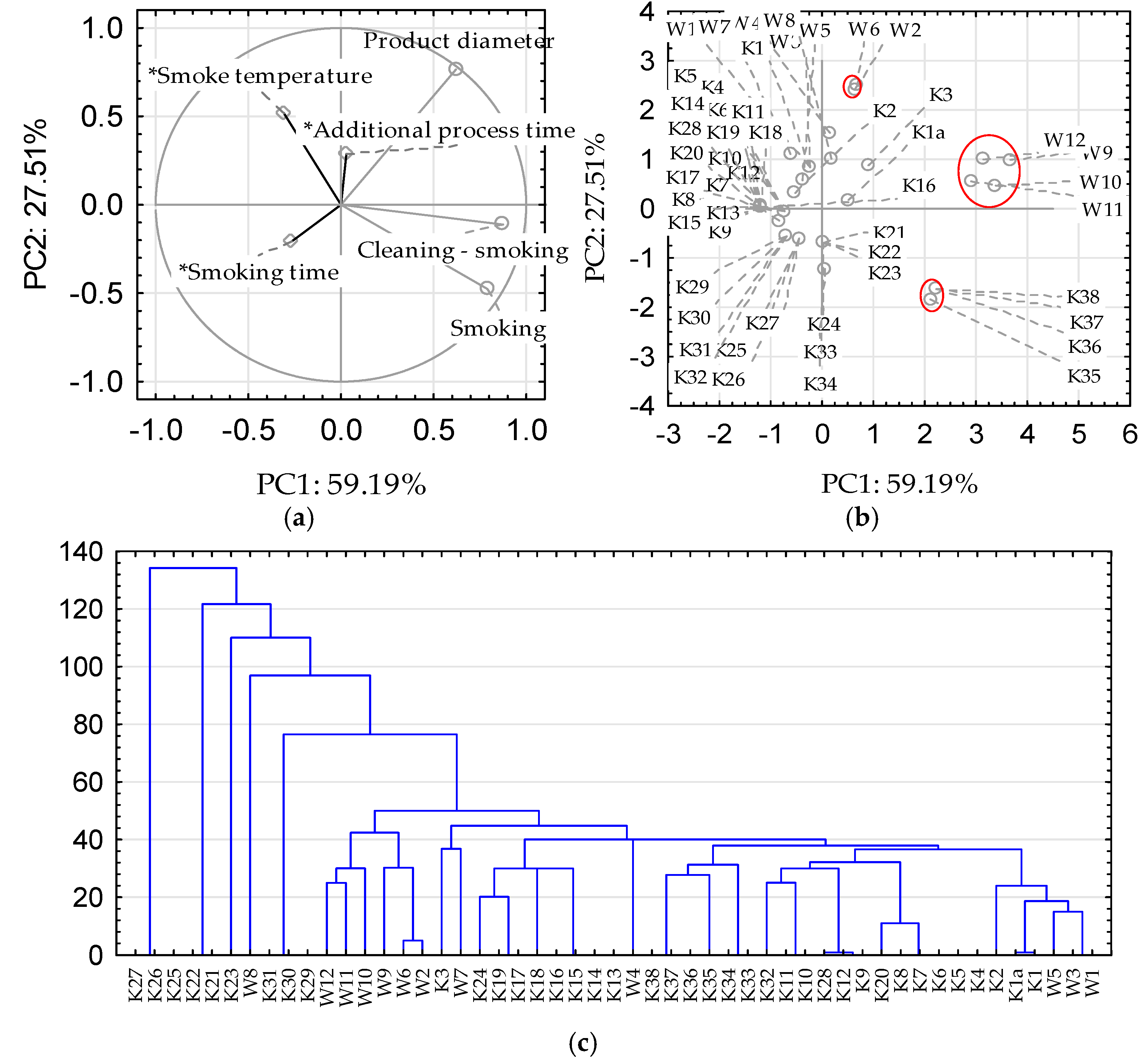

3.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ledesma, E.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M. Contamination of meat products during smoking by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Processes and prevention. Food Control 2016, 60, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L. Concentrations of environmental organic contaminants in meat and meat products and human dietary exposure: A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semanová, J.; Skláršová, B.; Šimon, P.; Šimko, P. Elimination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from smoked sausages by migration into polyethylene packaging. Food Chem. 2016, 201, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Kuhnle, G.K.; Cheng, Q. Heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in commercial ready-to-eat meat products on UK market. Food Control 2017, 73, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jeong, J.H.; Park, S.; Lee, K.G. Monitoring and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in processed foods and their raw materials. Food Control 2018, 92, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachara, A.; Juszczak, L. Contamination of food with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—Legal requirements and monitoring. Food Science Technology Quality-ZNTJ 2016, 3, 5–20, http://www.wydawnictwo.pttz.org/wp-content/uploads/pelne_zeszyty/full_20163106.pdf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.; Varshney, J.G.; Agarwal, T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons’ formation and occurrence in processed food. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciecierska, M.; Obiedziński, M.W. Influence of smoking process on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons’ content in meat products. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2007, 6, 17–28. Available online: https://www.food.actapol.net/volume6/issue4/2_4_2007.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No. 836/2011 Amending Regulation (EC) No. 333/2007 Laying Down the Methods of Sampling and Analysis for the Levels of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, Inorganic tin, 3-MCPD and Benzo(a)pyrene in Foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union 2011. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/836/oj (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No. 915/2023 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels of certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Official Journal of the European Union 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/915/oj (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Migdał, W.; Dudek, R.; Kampinos, F.; Kluska, W. Wędliny wędzone tradycyjnie – zawartość wielopierścieniowych węglowodorów aromatycznych (WWA). In Właściwości produktów i surowców żywnościowych. Wybrane zagadnienia; Tarko, T., Duda-Chodak, A., Witczak, M., Najgebauer-Lejko, D., Eds.; Oddział Małopolski Polskiego Towarzystwa Technologów Żywności: Kraków, Poland, 2014; pp. 75–87. (In Polish). https://pttzm.org/index.php/wydawnictwa-oddzialu/ [Google Scholar]

- Zachara, A.; Gałkowska, D.; Juszczak, L. 2017: Contamination of smoked meat and fish products from Polish market with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Food Control 2017, 80, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migdał, W.; Dudek, R.; Kapinos, F.; Kluska, W. Wędzenie tradycyjne. Punkty krytyczne; Polskie Stowarzyszenie Producentów Wyrobów Wędzonych Tradycyjnie: Kraków, Poland, 2016; pp. 1–70. Available online: https://piw.oswiecim.pl/files/2016%20-%20Migdal%20i%20wsp.%20-%20%20Broszura%20PSPWWT%20-%20%20Tradycyjne%20metody%20wedzenia%20-%20do%20druku.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No 1327/2014 of 12 December 2014 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as Regards Maximum Levels of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Traditionally Smoked Meat and Meat Products and Traditionally Smoked Fish and Fishery Products. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/1327/oj (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi z dnia 15 grudnia 2014 r. w sprawie wymagań weterynaryjnych przy produkcji produktów mięsnych wędzonych w odniesieniu do najwyższych dopuszczalnych poziomów zanieczyszczeń wielopierścieniowymi węglowodorami aromatycznymi (WWA) (Dz. U. 2018 poz. 1102). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20140001845/O/D20141845.pdf (accessed on 01 December 2024). (In Polish)

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission Regulation (EU) No. 836/2011 of 19 August 2011 Amending Regulation (EC) No. 333/2007 Laying Down the Methods of Sampling and Analysis for the Official Control of the Levels of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, Inorganic tin, 3-MCPD and Benzo(a)pyrene in Foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union 2011, L 215/9. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:215:0009:0016:EN:PDF (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Niewiadowska, A.; Kiljanek, T.; Semeniuk, S.; Niemczuk, K.; Żmudzki, J. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in smoked meat and fish. Vet. Med.-Sci. Pract. 2016, 72, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanović, T.; Pleadin, J.; Petričević, S.; Listeš, E.; Sokolić, D.; Marković, K.; Ozogul, F.; Šimat, V. The occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in fish and meat products of Croatia and dietary exposure. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 75, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojinu, O.S.; Olofinyokun, L.; Idowu, A.O.; Mosaku, A.M.; Oguntuase, B.J. Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) In Smoked Fish and Meat Samples In Abeokuta. J. Chem. Soc. Nigeria 2019, 44, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Onopiuk, A.; Kołodziejczak, K.; Szpicer, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Wierzbicka, A.; Półtorak, A. Analysis of factors that influence the PAH profile and amount in meat products subjected to thermal processing. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ng, K.; Warner, R.D.; Stockmann, R.; Fang, Z. Reduction strategies for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in processed foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1598–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciecierska, M.; Dasiewicz, K.; Wołosiak, R. Method of minimizing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content in homogenized smoked meat sausages using different casing and variants of meat–fat raw material. Foods 2023, 12, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racovita, R.C.; Secuianu, C.; Ciuca, M.D.; Israel-Roming, F. Effects of Smoking Temperature, Smoking Time, and Type of Wood Sawdust on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Accumulation Levels in Directly Smoked Pork Sausages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 9530–9536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iko Afé, O.H.; Douny, C.; Kpoclou, Y.E.; Igout, A.; Mahillon, J.; Anihouvi, V.; Hounhouigan, D.J.; Scippo, M.L. Insight about methods used for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons reduction in smoked or grilled fishery and meat products for future re-engineering: A systematic review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 141, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, G.R.; Guizellini, G.M.; da Silva, S.A.; de Almeida, A.P.; Pinaffi-Langley, A.C.C.; Rogero, M.M.; de Camargo, A.C.; Torres, E.A.F.S. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Foods: Biological Effects, Legislation, Occurrence, Analytical Methods, and Strategies to Reduce Their Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokkanen, M.; Luhtasela, U.; Kostamo, P.; Ritvanen, T.; Peltonen, K.; Jestoi, M. Critical Effects of Smoking Parameters on the Levels of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Traditionally Smoked Fish and Meat Products in Finland. J. Chem. 2018, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puljić, L.; Mastanjević, K.; Kartalović, B.; Kovačević, D.; Vranešević, J.; Mastanjević, K. The Influence of Different Smoking Procedures on the Content of 16 PAHs in Traditional Dry Cured Smoked Meat “Hercegovačka Pečenica”. Foods 2019, 8, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malarut, J.A.; Vangnai, K. Influence of wood types on quality and carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) of smoked sausages. Food Control 2018, 85, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinkova, Z.; Wenzl, T. The Occurrence of 16 EPA PAHs in Food—A Review. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2015, 35, 248–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafouris, D.; Koukkidou, A.; Christou, E.; Hadjigeorgiou, M.; Yiannopoulos, S. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in traditionally smoked meat products and charcoal grilled meat in Cyprus. Meat Sci. 2020, 164, 108088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledesma, E.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M. Characterization of natural and synthetic casings and mechanism of BaP penetration in smoked meat products. Food Control 2015, 51, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, E.; Yebra-Pimentel, I.; Martinez-Carballo, E.; Simal-Gándara, J. Profiling, distribution and levels of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in traditional smoked plant and animal foods. Food Control 2016, 59, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastanjević, K.; Kartalović, B.; Petrović, J.; Novakov, N.; Puljić, L.; Kovačević, D.; Jukić, M.; Lukinac, J.; Mastanjević, K. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the traditional smoked sausage Slavonska kobasica. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 83, 103282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadat Mirbod, M.; Hadidi, M.; Huseyn, E.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon in smoked meat sausages: Effect of smoke generation source, smoking duration, and meat content. Food Sci. Technol (Campinas) 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastanjević, K.; Kartalović, B.; Lukinac, J.; Jukić, M.; Kovačević, D.; Petrović, J.; Habschied, K. Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Traditional Dry Cured Smoked Ham Slavonska Šunka. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraqueza, M.J.; Laranjo, M.; Alves, S.; Fernandes, M.H.; Agulheiro-Santos, A.C.; Fernandes, M.J.; Potes, M.E.; Elias, M. Dry-Cured Meat Products According to the Smoking Regime: Process Optimization to Control Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Foods 2020, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozentāle, I.; Yan Lun, A.; Zacs, D.; Bartkevičs, V. The occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in dried herbs and spices. Food Control 2018, 83, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, G.; Potortì, A.G.; Ben Tekaya, A.; Beltifa, A.; Ben Mansour, H.; Sajia, E.; Bartolomeo, G.; Naccari, C.; Dugo, G.; Lo Turco, V. Organic contamination of Italian and Tunisian culinary herbs and spices. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2019, 54, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljanec, I.; Radovčić, N.M.; Karolyi, D.; Petričević, S.; Bogdanović, T.; Listeš, E.; Medić, H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in four different types of Croatian dry-cured hams. Meso 2019, 21, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastanjević, K.; Puljić, L.; Kartalović, B.; Grbavac, J.; Jukić Grbavac, M.; Nadaždi, H.; Habschied, K. Analysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Heregovački pršut-Traditionally Smoked Prosciutto. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozentāle, I.; Stumpe-Vīksna, I.; Začs, D.; Siksna, I.; Melngaile, A.; Bartkevičs, V. Assessment of dietary exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from smoked meat products produced in Latvia. Food Control 2015, 54, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatowski, Z.; Niewiadowska, A.; Kiljanek, T.; Borzęcka, M.; Semeniuk, S.; Żmudzki, J. Poradnik Dobrego Wędzenia. Centrum Doradztwa Rolniczego w Brwinowie O/Radom, Radom. 2014. Available online: https://poznan.cdr.gov.pl/catalog/uploads/2014-PORADNIK-DOBREGO-WEDZENIA.pdf. (In Polish)

- Parker, J.K.; Lignou, S.; Shankland, K.; Kurwie, P.; Griffiths, H.D.; Baines, D.A. Development of a Zeolite Filter for Removing Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) from Smoke and Smoked Ingredients while Retaining the Smoky Flavor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2449–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zastrow, L.; Schwind, K.H.; Schwägele, F.; Speer, K. Influence of Smoking and Barbecuing on the Contents of Anthraquinone (ATQ) and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Frankfurter-Type Sausages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13998–14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustawa 2018. Ustawa z dnia 6 marca 2018 r. - Prawo przedsiębiorców - Act 2018. Act of 6 March 2018 – Entrepreneurs’ Law (tekst jednolity Dz.U. 2024 poz 236). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20240000236/U/D20240236Lj.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024). (In Polish)

| Sample codes | Grinding | Type of smoking | Type of spices | Type of wood | Wood seasoning | Wood debarking | Frequency of cleaning the smoking chamber [per month] | Type of casings | Product diameter [mm] | Smoking time [min] | Smoke temperature [ºC] | Application of an additional process | Additional smokehouse equipment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | S | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | lack | 80 | 60-90 | 70-100/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| W2 | S | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | lack | 150-200 | 60-90 | 70-100/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| W3 | S | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | lack | 80 | 60-90 | 70-100/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| W4 | S | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | lack | 120 | 60-90 | 70-100/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| W5 | S | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | lack | 50 -80 | 60-90 | 70-100/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| W6 | S | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | lack | 150-200 | 60-90 | 70-100/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| W7 | S | 1 | N | O/A | Y/N | Y/N | 2 | lack | 60 - 120 | 90-120 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 90-120 min., steaming | lack |

| W8 | S | 2 | M | O/A | Y | Y/N | 1 | lack | 100 - 140 | 180-240 | 50-60/ rare smoke | drying (W) 90 min., steaming | chokes |

| W9 | S | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | each time after production | lack | 180 | 60 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 90 min., steaming | lack |

| W10 | S | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | each time after production | lack | 150 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 90 min., steaming | lack |

| W11 | S | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | 8 | lack | 150 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min., steaming | lack |

| W12 | S | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | 8 | lack | 150-200 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min., steaming | lack |

| K1 | C | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | O (protein casing) |

80 | 60 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K2 | C | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | O (protein casing) | 50 | 60 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min., steaming | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K3 | C | 2 | N | A | Y | Y/N | 4 | N | 120 | 120 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (H) 120 min., steaming | chokes |

| K4 | M | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 90 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min. | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K5 | M | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 90 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min. | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K6 | M | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 90 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min. | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K7 | M | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 90 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min. | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K8 | M | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 90 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min. | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K9 | M | 1 | N | O/A | Y/N | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 120-150 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 30-60 min. | lack |

| K10 | M | 1 | N | O/A | Y/N | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 90-120 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 30-60 min | lack |

| K11 | M | 1 | N | O/A | Y/N | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 90-120 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 30-60 min | lack |

| K12 | M | 1 | N | O/A | Y/N | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 120-150 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 30-60 min | lack |

| K13 | M | 1 | N | O | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 60 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min., steaming | shafts |

| K14 | M | 1 | N | O | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 60 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min | shafts |

| K15 | M | 1 | N | O | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 60 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min | shafts |

| K16 | M | 1 | M | O | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 60 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min | shafts |

| K17 | M | 1 | N | O | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 120 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min | shafts |

| K18 | M | 1 | N | O | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 90 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min | shafts |

| K19 | M | 1 | N | O | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 120 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 120 min | shafts |

| K20 | M | 1 | N | B | Y/N | Y/N | 4 | N (sheep casing) | 18 | 90 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 80 min | valves, fans, shafts, chokes |

| K21 | M | 2 | N | A | Y | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 420 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (H) 120 min | shafts |

| K22 | M | 2 | N | A | Y | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 420 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (H) 120 min | shafts |

| K23 | M | 2 | N | A | Y | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 300 | 50-60/ dense smoke | drying (H) 120 min | shafts |

| K24 | M | 2 | N | A | Y | Y/N | 4 | N | 28-32 | 120 | 50-60/ dense smoke | drying (H) 120 min., steaming | shafts |

| K25 | M | 2 | N | O-W | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 360 | 50-60/ rare smoke | brak | shafts |

| K26 | M | 2 | N | O-W | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 360 | 50-60/ rare smoke | brak | shafts |

| K27 | M | 2 | N | O-W | Y | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 360 | 50-60/ rare smoke | brak | shafts |

| K28 | M | 1 | N | O/A | Y/N | Y/N | 2 | N | 28-32 | 120-150 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 30-60 min | lack |

| K29 | M | 2 | M | O/A | Y | Y/N | 1 | N | 28-32 | 180-240 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60 min | chokes |

| K30 | M | 2 | M | O/A | Y | Y/N | 1 | N | 28-32 | 180-240 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60 min | chokes |

| K31 | M | 2 | M | O/A | Y | Y/N | 1 | N | 28-32 | 180-240 | 70-80/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60 min | chokes |

| K32 | M | 2 | M | O/A | Y | Y/N | 1 | N | 28-32 | 90-120 | 50-60/ rare smoke | drying (W) 60 min., steaming | chokes |

| K33 | M | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | 1 | N | 28-32 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | lack |

| K34 | M | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | 1 | N | 28-32 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 60-90 min., steaming | lack |

| K35 | M | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | each time after production | N (sheep casing) | 18 | 55 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 45 min., steaming | lack |

| K36 | M | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | each time after production | N | 28-32 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 45 min., steaming, | lack |

| K37 | M | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | each time after production | N | 28-32 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 45 min., steaming | lack |

| K38 | M | 3 | M | B-A | ND | ND | each time after production | N | 28-32 | 30 | 60-70/ dense smoke | drying (W) 45 min., steaming | lack |

| Relative Intensity (% of Base Peak) | EI-GC-MS (Relative) |

|---|---|

| > 50 % | ± 10 % |

| >20 % do 50 % | ± 15 % |

| >10 % do 20 % | ± 20 % |

| ≤10 % | ± 50 % |

| Sample Codes | Benzo(a)pyrene Content [µg/kg] | Measurement Uncertainty | Total Content of 4 PAHs [µg/kg] | Measurement Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | <0.9 (<LOQ) | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W2 | <0.9 | lac | <0.9 | lack |

| W3 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W4 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W5 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W6 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W7 | <0.9 | lack | 2.5 | 0.6 |

| W8 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W9 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W10 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W11 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| W12 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| Sample Codes | Benzo(a)pyrene Content [µg/kg] | Measurement Uncertainty | Total Content of 4 PAHs [µg/kg] | Measurement Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | <0.9 (<LOQ) | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| K2 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| K3 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 10.6 | 2.5 |

| K4 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 10.4 | 2.5 |

| K5 | 20.8 | 5.4 | 31.5 | 7.5 |

| K6 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 18.9 | 3.9 |

| K7 | 6.2 | 1.6 | 22.8 | 5.4 |

| K8 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 13.6 | 3.2 |

| K9 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 15.1 | 3.6 |

| K10 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 17.9 | 4.3 |

| K11 | <0.9 | lack | 5.2 | 1.2 |

| K12 | 10.7 | 2.8 | 37.7 | 9.0 |

| K13 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 6.2 | 1.5 |

| K14 | 6.0 | 1.6 | 13.7 | 3.3 |

| K15 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 8.5 | 2.1 |

| K16 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 7.2 | 1.7 |

| K17 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 13.6 | 3.2 |

| K18 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 5.3 | 1.3 |

| K19 | 5.7 | 1.5 | 15.2 | 3.6 |

| K20 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 12.4 | 3.0 |

| K21 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 20.4 | 4.9 |

| K22 | 20.6 | 5.4 | 35.5 | 8.5 |

| K23 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 11.4 | 2.7 |

| K24 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 11.5 | 2.7 |

| K25 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 12.1 | 2.9 |

| K26 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 7.2 | 1.7 |

| K27 | 4.2 | 1.1 | 16.8 | 4.0 |

| K28 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 21.0 | 5.0 |

| K29 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 17.5 | 4.2 |

| K30 | 12.1 | 3.2 | 32.2 | 7.7 |

| K31 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 12.1 | 2.9 |

| K32 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 4.7 | 1.1 |

| K33 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| K34 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| K35 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| K36 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| K37 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

| K38 | <0.9 | lack | <0.9 | lack |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).