1. Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) affects approximately 39.9 million people worldwide with an incidence rate of 1.3 million individuals per year.[

1,

2] Despite advancements in treatment, it remains a major global public health challenge. HIV is a retrovirus that compromises the immune system by targeting CD4+ T cells, weakening the body’s ability to fight infections and increasing vulnerability to opportunistic diseases. This virus is particularly challenging to eliminate due to its ability to integrate into the host’s DNA, forming latent reservoirs that are not easily targeted by antiretroviral therapies (ART).[

3] Additionally, HIV's rapid mutation rate complicates the development of a universal cure or vaccine, as the virus can quickly adapt and evade immune detection.[

3]

Sub-Saharan Africa bears a disproportionate burden of the global HIV epidemic, with Uganda ranking among the top five countries with the highest prevalence of people living with HIV.[

4] The national prevalence hovers around 5.4%, with a higher concentration of cases in urban areas and among key populations (people who sell or exchange sex, people who inject drugs (PWID), men who have sex with men (MSM), and transgender individuals) who are particularly vulnerable to HIV acquisition due to a combination of behavioral, biological, and social factors.[

5] These groups often face structural barriers, including criminalization, stigma, and limited access to healthcare services, which further exacerbates their risk.[

6] Among the general population, young adults, particularly women and adolescent girls, are at an elevated risk of acquiring HIV.[

7] In sub-Saharan Africa,[

8] young women are twice as likely as young men to be living with HIV, a disparity driven by gender inequalities, limited access to sexual and reproductive health services, and higher levels of gender-based violence.[

7] Addressing these vulnerabilities requires not only medical solutions but also comprehensive strategies that reduce stigma and discrimination while increasing access to care.

Over the past few decades, considerable progress has been made in the development of HIV prevention technologies. Current preventative measures include oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and condom use, yet these methods face challenges related to adherence and consistent use (6). For populations with limited autonomy over their health decisions or those in stigmatized environments, the logistical and social challenges of maintaining daily PrEP regimes can be significant. The advent of long-acting injectable PrEP represents a promising advancement, offering sustained protection with a reduced burden on daily adherence.[

9,

10] Longer-term preventative options under consideration include not only injectable PrEP but also implants and vaccines.[

9] However, the development of a preventative HIV vaccine remains elusive despite clinical trials since the 1990s. The complexity of HIV's structure, its mutability, and the challenge of targeting the virus in latent reservoirs have stymied progress in vaccine development.[

3] Nonetheless, the recent approval of long-acting injectable PrEP marks a pivotal moment in HIV prevention. This new method provides discreet, sustained protection for high-risk populations, offering a pathway to overcome some of the social challenges associated with existing options.[

8]

In summary, investigating how key populations, particularly those in Uganda, value features of long-acting prevention strategies, such as injectable PrEP, will be crucial in shaping the future landscape of HIV prevention.[

8] This information is essential to inform healthcare providers, policymakers, and intervention designers on how best to facilitate access and adoption of these novel technologies, ensuring that they meet the needs of those most vulnerable to HIV acquisition. This study examined factors that are most preferable to at-risk populations, and therefore affect their decisions to accept a preventative HIV vaccine in comparison to other preventative methods with the primary objective to inform the implementation of a discrete choice experiment (DCE) in Uganda.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site

The Makerere University Walter Reed Project (MUWRP), the site where this protocol was implemented, is a biomedical research organization located in Kampala, Uganda. MUWRP has a long history of vaccine and therapeutic research in infectious diseases including HIV, Ebola, Marburg and tropical neglected diseases, such as schistosomiasis. MUWRP is also supported by the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) for comprehensive HIV prevention and treatment in four districts in central Uganda. Interviews took place at MUWRP HIV Clinics and other partnering sites, primarily in Kampala, the capital city of Uganda with approximately 1.5 million (SD:1.4,1.6 mill) people living with HIV (PLWH) as of 2023.[

5]

2.2. Population

The study population included experts in the field of HIV prevention, and People at Substantial Risk for HIV Acquisition (PSRHA) in Uganda. HIV experts were recruited based on their experience working with at-risk populations, distributing or prescribing HIV prevention products, or consulting with at-risk populations regarding their HIV prevention choices with a specific emphasis on the following categories: Nurses, peers/community workers, prevention program managers, policy makers.

PSRHA were defined in this study based on an adapted shortened criteria version of the Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Screening for (High) Substantial Risk and Eligibility form used by the Ugandan Ministry of Health (HIMS ACP 028, 2019). These criteria included: being sexually active AND reporting vaginal or anal intercourse without condoms with more than one partner OR having a sex partner with one or more HIV risk(s), OR having a history of a sexually transmitted (STI), OR having a history of use of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), OR if an injection drug user, reports a history of sharing injection materials/equipment, OR has a sexual partner that is HIV positive and has not been on effective HIV treatment (see Supplementary S1 for more detail on inclusion criteria). Other criteria from the PrEP Screening Form were not included because they asked questions that were considered too sensitive at the time of the study commencement due to the country’s enactment of the Anti-Homosexuality Act[

11] and may have endangered participants. Participants were excluded from the key informant interviews if they were under the age of 18.

A sample size of 20 participants was determined

a priori based on previous literature that states that 16 interviews or fewer should be sufficient to identify common themes when sampling from similar sites, and at least 20 needed to identify meta themes.[

12] We therefore recruited ten experts in the field of HIV prevention and ten PSRHA. Our research team debriefed after each interview to discuss the degree of saturation of the data reached to determine if more participants were required past the original 20 planned. The team mutually decided that there was no need for additional recruitment after the last participant completed the interview as no new major themes were emerging.

2.3. Community Engagement

We consulted with the MUWRP community advisory board (CAB) and asked for their advice before beginning community engagement. These participants were purposively sampled with the help of MUWRP Community Engagement team to gather data from diverse sources using the MUWRP existing networks from previous MUWRP clinical research studies or PEPFAR activities.

Research assistants conducted recruitment either via phone calls or face-to-face. Participants for the expert interviews were workers at HIV prevention programs in Kampala, Mukono, and Kayunga, HIV researchers, leaders of network organizations of the key populations, and researchers currently working on the HIV clinical trials. Experts and PSRHA were screened to ensure eligibility before the interview commenced. All participants who were engaged were interviewed, and there were no drop-out participants.

Due to the sensitive nature of the questions, and concerns for the safety of participants, some protective measures were put into place. For instance, if participants were unable to complete the interview at that time, they had the option to complete the process either at MUWRP or in the field at a later appointment time. Participants were also gender matched with the research assistant for the interviews as often as possible. Interviews were held in a private location where the conversation could not be overheard by others, for example a private room in a clinic or an office with a door that could be closed for privacy. Interviewers were trained to identify if the participant was uncomfortable. If they perceived that a participant was uncomfortable at any time, they reminded the participant that they could exit the study at any time.

Participants were also given the opportunity to ask any questions, or request that the research team delete their data if they finally decided that they did not want to be a part of the study in the end. Data collected during this study was stored with utmost care and confidentiality in double locked rooms if in person or encrypted secure shared drives with limited accessibility.

2.4. Lancaster’s Consumer Theory

We used Lancaster’s new consumer economic theory as the main guide for this study.[

13] This theory is founded in the economic principles of supply and demand, where the world is assumed to have limited resources and people are assumed to have to therefore make choices based on what they value, or get the most utility from. People are assumed to try to maximize the utility they are gaining from the resources they have by trading resources. In Lancaster’s new consumer economic theory, he proposes that people do not simply derive utility from the goods or services they are trading but rather from the characteristics of those goods and services. The random utility model derived from this theory demonstrates the overall utility of a resource (i.e., a good or service) that a person may trade as a summation of the utility of each relevant characteristic of that resource plus an error term that represents the random heterogeneity underlying the population that we, the researchers, have not measured. This theory is appropriate to use for the design of this study and the analysis of the study findings because the interviews were conducted with the purpose to act as a foundation for the design of a discrete choice experiment which is based on Lancaster’s economic theory and utilizes the Random Utility Model for its analysis.[

14]

2.5. Data Collection

Interviews took place in March 2024. All consent, screening and data collection procedures took place in person. After consenting participants, research assistants asked them to provide some demographic information (Supplementary S2). The demographic and eligibility questionnaires were administered on a tablet or on paper, if the tablet was not available or working. The research assistants then proceeded to data collection. There were two trained research assistants at each session, alternating roles for each interview. One research assistant acted as the interviewer, asking questions from participants, and the other acted as a notetaker, responsible for taking field notes in a structured format, on body language and tone, as well as audio recording interviews, keeping time, and suggesting probes to the interviewer as needed. The notes for each interview were taken in a matrix format structured according to similar questions in the guide to facilitate the rapid analysis process, described in more detail below.

The semi-structured key informant guides were created in English based on a previous similar DCE key informant interview guide.[

15] Adaption of the questions was guided by the research question, the context in which the guide was to be administered, economic theory of preference elicitation methods, specifically Lancaster’s consumer theory[

13] where, people are assumed to be rational decision makers in search of a maximized and stable set of preferences. The guide was translated by vetted contracted translators into Luganda, the most spoken local language in Kampala, Kayunga and Mukono (Supplementary S1). The focus of the interview was to identify preferences of Ugandan key and priority populations regarding a future HIV vaccine or injectable preventative medication and to derive important factors that could influence their decision in receiving this medication, to be used to design a discrete choice experiment.

Topics discussed in expert and PSRHA interviews included: HIV vaccine in general (e.g., “what have you heard about the vaccine?”), preferred injectable characteristics (e.g., side effects, duration, effectiveness, frequency of administration, cost, dissemination points, person who dispenses), and other relevant health promotion and preference questions (e.g., feasibility of recruitment, messaging, moral foundations). The expert interview guide additionally focused on the preferences of the PSRHA with whom they work in their workplace, rather than on their personal preferences. The guide for expert participants had a few additional questions regarding approval and dissemination processes for a future HIV vaccine. The guide was pilot tested ahead of actual data collection within the study team.

Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. The process of interviewing was iterative, and varied slightly depending on previous interviews, and the interviewing style of the four interviewers, who were involved in the data collection process. After each interview, the research assistant thanked the participant and provided 50,000 UGX (approximately 13.64 USD) as compensation for their time and transportation costs. Following the interview, the notetaker and interviewer debriefed together, or with a senior research team member to take note of any thoughts which emerged as part of the data collection process to inform the preliminary rapid analysis. During the debrief, the researchers took note of any new themes emerging to monitor for data saturation. Interviewers subsequently transcribed and translated all interviews into English using the audio recording. Notetakers subsequently reviewed and edited transcripts to ensure accuracy. Transcripts were not returned to participants for discussion since participant contact information was not collected to respect confidentiality. No repeat interviews were conducted.

2.6. Data Analysis

Two interviewers (JK, SM) and the principal investigator (MBN) worked together to conduct a preliminary rapid analysis of the findings based on the notes for a rapid report of findings with the primary purpose to inform the design of the discrete choice experiment. Interviewers provided insights regarding cultural context as part of the analysis process since they were from Uganda. An adjusted version of an established rapid analysis process was used where the matrices of notes were used to help break down and summarize findings.[

16] The report of the rapid analysis findings was made to the MUWRP CAB for member checking and validation of the results. rapid analysis summary was also used to form the initial coding tree (Supplementary S2), which was adjusted iteratively during the subsequent thematic analysis of the data.

For the purpose of this manuscript, the team used an inductive and iterative approach to further develop the coding tree from the rapid analysis and add any new themes that emerged from the data.[

17] The codebook and transcripts were entered into the qualitative analysis software Dedoose (version 9.0.17) for coding, data management and subsequent analysis (Supplementary S3).[

18] The analysts each independently coded a transcript, which was chosen due to its comprehensiveness of ideas mentioned in the interview. The team then discussed the codebook as they resolved coding discrepancies. All conflicts were resolved through discussion; and when that was not possible, the principal investigator made the final decision regarding the coding. We finally created a conceptual map of findings using Lancaster’s economic consumer model as a lens.

We present our findings in a narrative analysis using coded data. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was used to help guide the reporting of our findings.[

19]

2.7. Reflexivity Statement

The four interviewers (JK, BN, MS, RM) are Ugandans with experience in qualitative data collection, and one of whom had experience leading qualitative data collection teams and conducting discrete choice experiments (RM). Three of them were men (JK, MS, RM) and one was a woman (BN). All researchers had at least a bachelor's degree in either social work or public health; two were completing master’s in public health at the time of this study (JK, RM), one was working in public service (BN), and two were actively conducting public health research for other projects at the same time (JK, RM). Two were counselors, one was working for the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, and the other was a project coordinator for a renowned research institute in Uganda. All received additional training on qualitative research before beginning data collection.

The three data analysts who coded the data were all women based at an American institution at the time of the study (MN, WH, CD). One of them was studying for her PhD in public health (MN), one had completed two master’s degrees, one of which was in public health (CD), and the other had completed a Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery (MBBS) and was completing her master’s in public health at the time of data analysis (WH). One of the researchers was from Asia (WH) and the other two were from the USA (MN, CD). Two had prior research knowledge in a global health context from previous research experiences (MN, WH).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

Experts were primarily Counselors / KP Focal Persons (n=4) but also included one of each of the following positions: HIV Prevention Officer, Team leader, Drop-in Center (DIC) Coordinator, Senior research supervisor, Fieldworker, and Program officer.

Among PSRHA participants, a diverse range of key populations were represented in the. Key populations identified in the KIIs included: men who have sex with men (MSM), adolescent girls and young women (AGYW), transgender men and women, fisherfolk, female sex workers (FSWs), PWIDs, truck drivers, boda-boda drivers, uniformed personnel, and the general population. Of the PSRHA participants, 50% were female (n=10), 35% were male (n=7), and 15% identified as other genders (n=3), though specific gender identities were not disclosed.

In terms of marital status, two PSRHA participants were married, while eight were single or had never been married. Education levels varied, with two PSRHA participants having finished primary school, three having attended some secondary school, and five completing secondary school. Regarding employment status, five PSRHA participants were employed full time, three were employed part time, and two were unemployed. The average number of adults in each participant's household was 8.6 (median: 3, range: 1-50) while the average number of children was 5.5 (median: 4, range: 0-30).

When asked how many people they provided monetary support for, two PSRHA participants supported one person, three supported two to five people, four supported six to ten people, and one participant supported more than ten people. The average monthly income among participants was 275,000 UGX (~75 USD), with a range from 50,000 (~14 USD) to 700,000 UGX (~190 USD), where the international poverty line is approximately 200,000 UGX (~55 USD) (20). In relation to HIV, six participants knew a friend living with HIV, three knew a family member, and one participant did not know anyone living with HIV. Eight participants expressed concern about acquiring HIV, one was somewhat concerned, and one was not concerned at all.

Additionally, eight participants reported having had a sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the past six months, four had taken post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), six shared injecting materials, and one participant had a partner living with HIV. See demographic information in

Table 1.

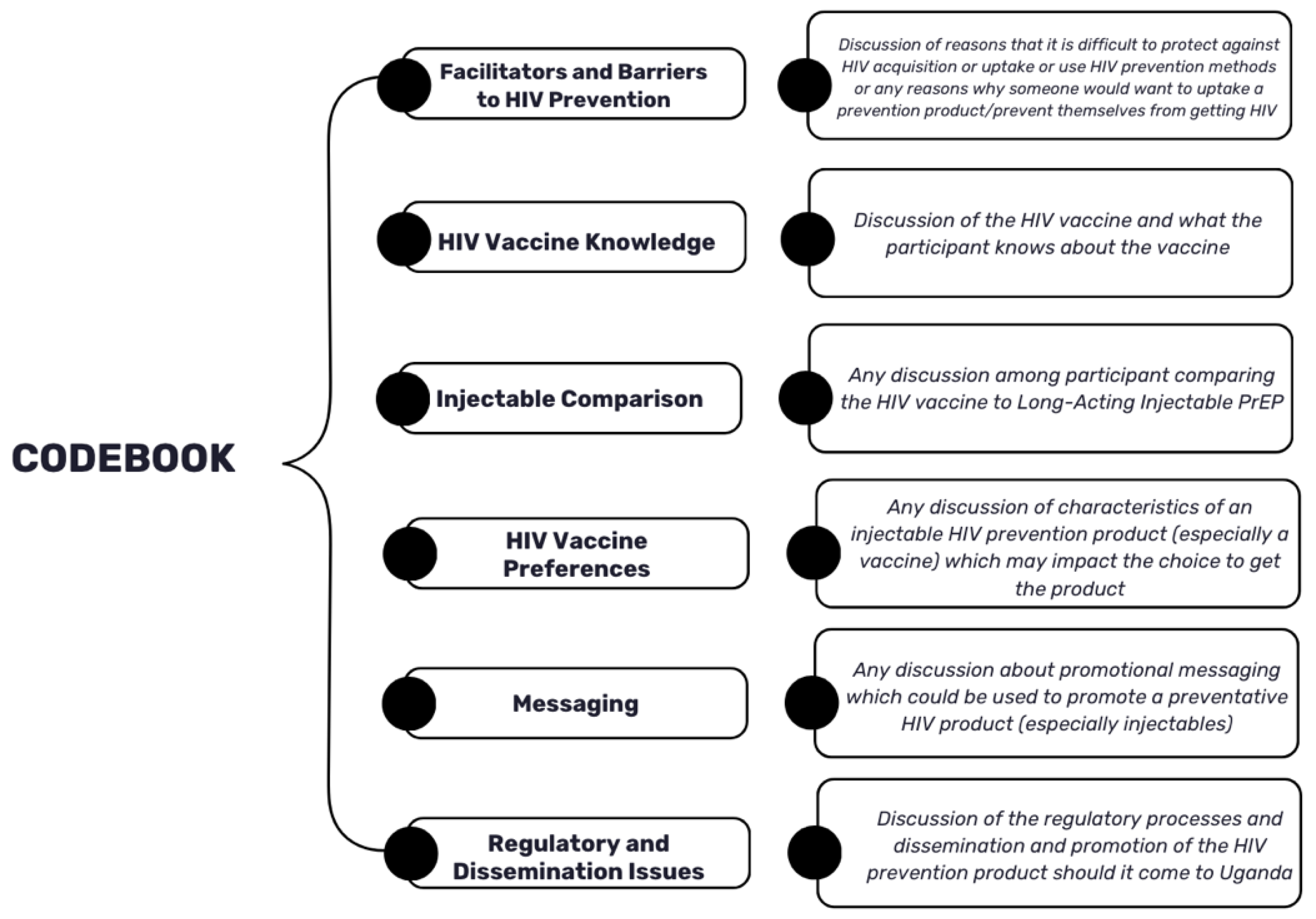

3.2. Overview of Themes

While the codebook for the thematic analysis aligned closely with the guide and its questions, some inductive themes emerged such as some barriers to prevention like the “pill burden”, accessibility issues and stigma-related issues. Topics which were discussed during the interviews fell under six primary themes: Facilitators and Barriers to HIV Prevention, HIV Vaccine Knowledge, Injectable Comparison, HIV Vaccine Preferences, Messaging and Regulatory and Dissemination Issues. It is important to note that the last theme about regulatory and dissemination issues was only discussed by the expert participants. Please see a summary of all codes below in

Figure 1. The full codebook is included in Supplementary S3. Findings related to each of these major theme groups are included below.

3.3. Barriers to HIV Prevention

The most frequently mentioned prevention methods used in communities were condoms and PrEP, followed by post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and HIV testing. Several different barriers to HIV prevention were discussed among the participants. These barriers consisted of ‘tablet fatigue’ or ‘pill burden’, stigma, misconceptions, location, accessibility, transportation, availability and cost.

The pill burden barrier coincided frequently with stigma. Stigma as a barrier was discussed in relation to barriers to using certain HIV prevention methods. One concern was the packaging for PrEP being similar to ART. Many mentioned not wanting to be perceived as taking ART and being misidentified as HIV-infected. One interviewee stated,

“[P]eople would easily think that you have HIV/AIDS. ‘They think it isn’t for prevention but ART treatment.’” (PKAY09)

It was mentioned that some, put off getting refills of oral PrEP, sometimes due to side effects, and thus use the method on and off. Taking a daily tablet was more difficult for certain key populations, like PWIDs and FSWs, who move around frequently. For those populations that moved around frequently, they sometimes forgot to carry their pills with them or were unable to get the medication leading to them missing their daily dose.

This concern was mentioned as a reason people do not adhere to taking the drugs because they do not want other people to see that they have the pills. Some did not want to disclose to partners, which made it hard for them to take the pills, and not have partners find out. Health centers were discussed as being places where key populations experienced stigmatization:

“They have their reasons like they will be stigmatized by the health workers and pointing fingers.” (EMUK10)

For example, it was discussed that transgender people were judged by their physical appearance when visiting the facilities for refills. Some health workers were reported as perceiving young adolescents and young key populations negatively for accessing condoms and PrEP. However, it was mentioned in a few interviews that there were often a few trusted healthcare workers who worked closely with stigmatized populations to whom these populations were often delegated.

Participants discussed misconceptions regarding different HIV prevention methods. These misconceptions included how these methods affect people's bodies and the side effects that they were concerned about. These misconceptions were that PrEP caused cancer, hallucinations, as well as thinking it was brought by the government to get rid of sex workers. Additional misconceptions regarding tablets included that HIV was in the tablets and brought to kill them and that the tablets could affect the liver, and fertility, and lead to loss of sexual activity:

“When we looked at the size of the PrEP tablet, it was just as big as ART pills, so, we thought it was simply an HIV drug, and they were just lying to us, and it was to be administered daily the same way with ART pills.” (PKAY09)

Location, accessibility and transportation were three barriers that were interconnected in the interviews. In some locations, key populations did not have access to PrEP. Even if they were in locations with health facilities or drop-in centers, some facilities administering PrEP were mentioned to not be open on the weekends, or not have health workers working on the weekends. For those who did not have transportation, picking up refills had become difficult. Long distances also prevented people from accessing the prevention methods they needed. Additionally, in most health facilities, for PrEP to be given, someone must first self-identify as a key population or be at high risk of acquiring HIV, making it difficult for some people to get the PrEP drug, especially those that did not want to disclose their identity due to fear of being stigmatized. As one participant said,

“So, there is a barrier for refills, and then there is a barrier of transport for them coming to pick PrEP after every three months or after one month. And then also there is inaccessibility, whereby it is not accessible at every health center within Uganda.” (EKAM02)

The limited availability of methods was a barrier discussed. Vaginal rings and PrEP are not always available in all health centers. In some instances, key populations were not aware of PrEP availability, this limited information, or even lack of information impacted access to HIV prevention methods.

3.4. HIV Vaccine Knowledge

While most participants appeared to have heard about the HIV vaccine, most did not have a lot of specific knowledge about the vaccine. Participants said that the vaccine protected against HIV when having unprotected sex, or would “boost” their body, or their “cells-blood cells” (PMUK10). Others thought the vaccine would act more like antiretroviral medications or a cure, saying it would “stop [HIV] from progressing to AIDS” (EKAY09). Many knew that vaccines were still under clinical trials. A few mentioned that the vaccine could cause side effects:

“I heard them say that if any vaccine is still new in the body, it first weakens you, it causes dizziness because it is not used to the body. Sometimes you can even get some running whatever.” (PKAM05)

There was also some confusion regarding the duration of the vaccine, possibly due to remembering information about injectable PrEP; some participants thought the HIV lasted for one to two months, others for six months, others for one year, while others said they did not know. A few seemed to have received information that it “prevents HIV but it will not prevent other diseases” (PKAM03) or pregnancy. When asked about mRNA HIV vaccine technology, participants had limited knowledge and understanding of the technology. One expert participant mentioned that they thought everyone would be required to get the vaccine, like the polio vaccine, though others were not sure. Another participant said they thought it would be expensive. One participant additionally mentioned concern that political will may interfere with the delivery of a future HIV vaccine:

“But if this vaccine is approved and introduced, then I believe everyone would prefer the vaccine instead. So, it would be nice to introduce the vaccine, only those politicians and other opportunists always tend to sabotage such kind of initiatives for their selfish interests.” (PKAM06)

Participants mentioned a variety of sources from whom they had heard information about the HIV vaccine including peers, friends, health educators, the news, the radio, talks from organizations like USAID, and community dialogues. A few participants mentioned that community talks had tried to preemptively address myths circulating in the community. Misinformation mentioned by participants primarily circulated safety issues (e.g., reduced lifespan, mental problems, reproduction issues). Experts, on the other hand, tended to view these concerns as myths that needed to be addressed through sensitization and education, focusing on the potential of the vaccine to reduce stigma and protect public health.

Participants also mentioned a worry that the HIV vaccine may encourage risky behaviors like unprotected sex, which may increase rates of unplanned pregnancy and STDs as a result:

“Getting vaccinated against HIV doesn’t mean living more recklessly with life, however, some would do exactly that, left and right, upon realizing that they cannot contract HIV any longer, which is very wrong.” (PKAM06)

Participants mentioned that key populations generally want the vaccine though, as one expert participant said, “They welcome it. Ok? They welcome it” (EKAM05). But there are still worries about safety. A clear message from participants was that key populations need enough information to feel motivated to get the vaccine, especially if that information comes from those doing the research.

3.5. HIV Vaccine Compared to Long-Acting Injectable PrEP

When asked which they would prefer, some preferred a vaccine because they think it will last longer, even for the rest of one’s life “you receive once and for all” (EKAM08). For instance, one participant mentioned,

“[W]ith vaccination, it would be protection for a longer period of time as opposed to the short while for the preventive injectable PrEP.” (PKAM07)

An expert acknowledged this duration preference and said that when comparing the two, they thought that people would go for the product that lasts longer. On the other hand, some thought PrEP was preferable because they had been using it and did not know much about the new HIV vaccine. It is also important to note that participants often confused PrEP and the HIV vaccine in conversation. For example, one participant mentioned, “We are told that PrEP also vaccinates” (PKAM08).

3.6. HIV Vaccine Preferences

Participants were asked to talk about different factors that may influence their decision to get an HIV vaccine with prompts about common issues mentioned previously in the literature. A few key findings were that preferences for efficacy were for it to be as high as possible, though minimally acceptable efficacy varied significantly. Still, experts tended to have higher minimal acceptable efficacy percentages than PSRHA participants overall. There was a strong preference among participants for the HIV vaccine to be free of cost. It was mentioned that even a small cost for the vaccine would be prohibitive for those unemployed or financially unstable.

Some participants mentioned concerns about the safety of the HIV vaccine causing severe health problems. Safety fears included becoming “lame”, getting cancer, liver damage, diabetes, death, infertility, decreased libido, and lower sperm count. Some participants mentioned worries that new vaccines are experimental, perceiving them as a trial conducted on their population. They mentioned a need for proper education and transparency from health workers about the vaccine’s safety and side effects, expressing a desire to see endorsements from health authorities like the Ministry of Health.

As mentioned above, accessibility was a key issue that was identified as a limitation participants anticipated in the rollout of a future HIV vaccine, expressing a preference for lower transportation costs and less documentation requirements, for instance. There was a preference for injections regarding mode of administration due to the perception that they worked faster, were more reliable, and provided long-lasting protection. Concerning the number of doses, many participants favored a single dose that provided lifetime protection to avoid forgetfulness and reduce the number of visits.

Participants preferred taking the HIV vaccine whenever they needed it, emphasizing the importance of ensuring flexibility and convenience. There were varied responses regarding the duration or frequency of doses, but most of the participants preferred quarterly doses, stating that this interval was practical and compatible with existing health practices like family planning injections, while also avoiding multiple frequent visits and site complications.

Regarding the question of who should administer the vaccine, overall, respondents preferred health workers like nurses or doctors to administer vaccines because they were perceived as more trustworthy, knowledgeable, and trained. For the place of administration, many respondents preferred clinics and hospitals because of their accessibility, availability of trained staff, safety, and reliability. Some of the participants preferred community-based locations such as hotspots for the key population like drop-in centers which were seen as safer, and less stigmatizing environments. See a summary of the findings related to preferences in

Table 2.

3.6. Regulatory and Dissemination Issues

When asked about the regulatory and dissemination processes, some participants responded enthusiastically that a vaccine should be required for all key populations. As one expert participant said,

“I: Should it be required for all the KPs to take such vaccine for HIV?

R: Yes, if its effective and available, yes.” (EKAM07)

Others were more hesitant about requiring a vaccine but instead emphasized the importance of having a vaccine that is safe and highly effective. Others also said, that instead of requiring a vaccine it could be helpful to have a promotion plan early on to encourage high uptake rates in the at-risk populations. Participants emphasized that people would want to know how a future preventative injection would be disseminated in the future:

“They would be interested in knowing about the side effects of the vaccine, places of dissemination, availability, and cost. With the condoms, there are really no concerns apart from some brands at some point that they were not comfortable with, that the brand wasn’t good.” (EMUK10)

Experts mentioned that involving the community will be an important part of the process of getting an HIV vaccine effectively disseminated. They expressed the importance of forming community advisory boards and engaging community leaders to help promote and build confidence among their constituents:

“So, when we are making policies, we need to involve them, at least we have the community advisory boards, so, if they are involved then to give feedback from the Key Populations themselves, it would help us to get informed on where and how best they would be preferring to get these vaccines.” (EKAM06)

Several organizations were mentioned that will be key in organizing the process of approval and dissemination including the World Health Organization and other international health organizations will need to approve the product; the institutional review boards, and the Ugandan National Council of Science and Technology, to ensure ethical research is conducted when researching the new products; the National Drug Authority to monitor and approve the drug for distribution in the country; the Ministry of Health to make sure the drug is approved, promoted and disseminated appropriately; pharmacies, health care facilities, drop-in centers, village health teams, peer leaders, and religious leaders to aid in dissemination at a local level. One participant mentioned that some have concerns about receiving preventative products from pharmacies.

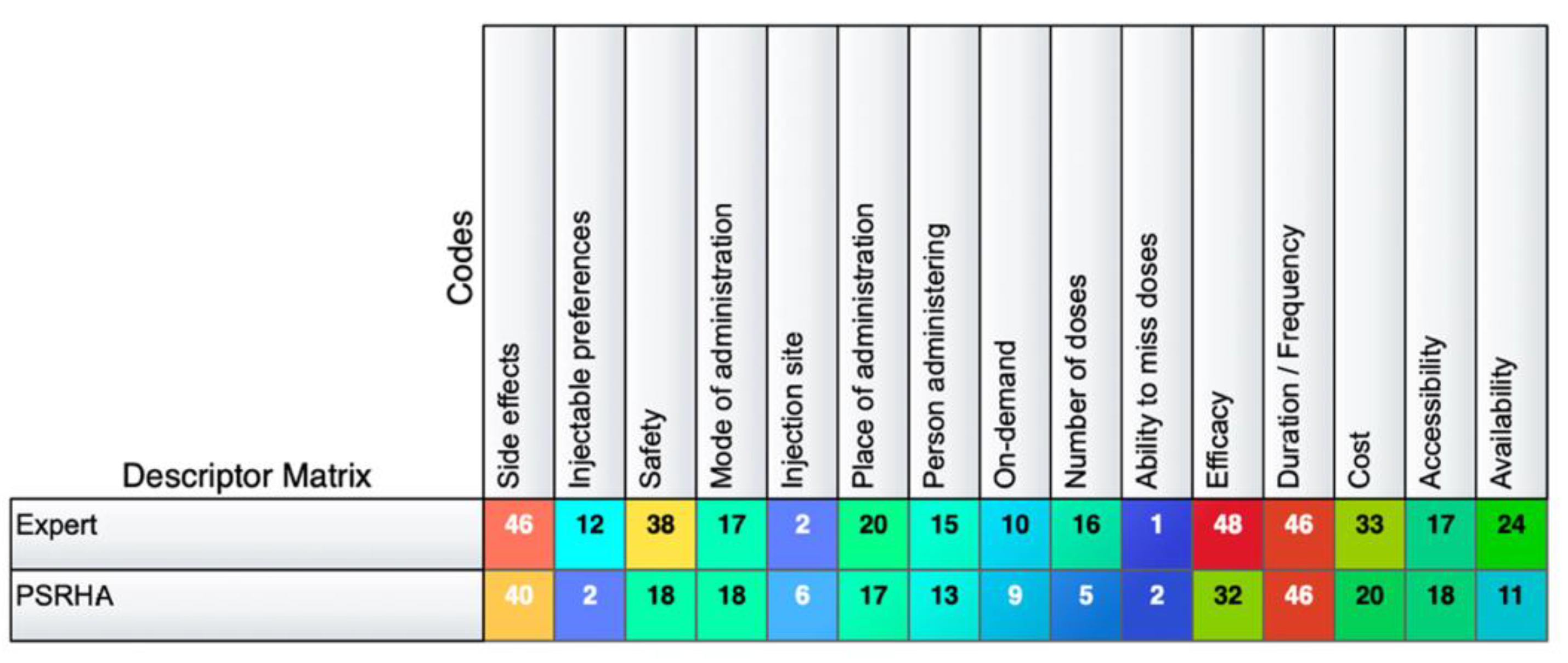

3.6. Comparison of Expert and PSRHA Participant Discussions About Injectable Preferences

Expert and PSRHA participants were asked almost the same questions, however their emphasis in responses were slightly different. For instance, while all participants discussed all preference characteristics, there were more instances of discussions coded about safety, availability, cost and efficacy among experts. On the other hand, there were more coded segments of discussions about the injection site, the ability to miss a dose, the number of doses, and accessibility among PSRHA participants. However, overall, the most discussed preferences among both groups were side effects, duration, efficacy, and cost.

Figure 2.

Number of coded segments for expert and PSRHA participants in each group. .

Figure 2.

Number of coded segments for expert and PSRHA participants in each group. .

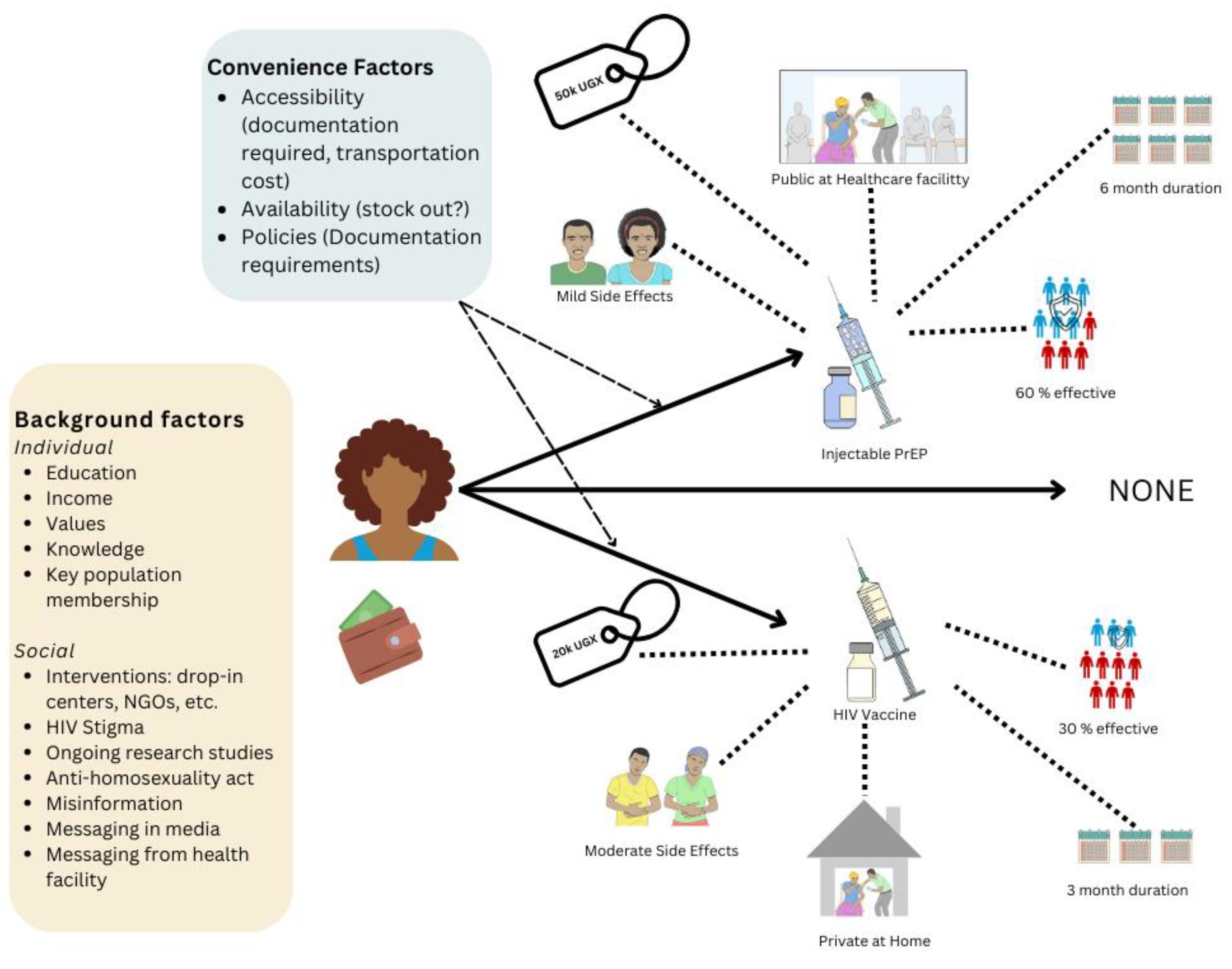

3.7. Interpretation of Findings Using Lancaster’s Consumer Economic Theory

In this analysis, we found that there were several factors which appeared to be preferred among the at-risk populations according to our participants, and yet a few factors emerged as being especially salient for PSRHA: side effects, cost, confidentiality, duration of effectiveness and percentage of effectiveness. In Lancaster’s new consumer economic theory, we would consider each of these characteristics as having their own unique value, and the different types of those “attributes” as also having their own unique values which would be revealed based on the choices that people make. In summary, a person would view the choice to get a particular type of injection product to prevent themselves from getting HIV as bundles of these different characteristics which sum up to create a lump sum of their preference for that product. The person would weigh their preferences and choose which one they would prefer, revealing what they valued more by spending their money (or not if there is a free option and cost was a significant driver of their choice).

Based on our interviews, however, we can also see that background factors such as education status, income level, individual values, background knowledge about the subject of HIV, and membership of different key populations (and their relative HIV risk statuses), as well as other social factors like interventions experienced, ongoing research studies they are a part of or had heard of on these HIV prevention technologies, policies like the Anti-Homosexuality Act, and different messaging and information (or misinformation) the person had been exposed to influences a person and their decisions. Then convenience factors such as accessibility, availability and other policies such as documentation requirements may also influence the person’s ability to decide which injectable product to get for their HIV prevention method. All these factors may fall under the error term in the random utility theory in the economic theoretical lens we are using in this study. However, ultimately, the assumption is that Lancaster’s consumer theory makes is that the person will make their decision regarding which product to get based on the bundle of attributes associated with each option they are presented with. In this case, since the most important attributes in this study appeared to be cost, side effects, duration, effectiveness and accessibility (with an emphasis on confidentiality), we present these attributes in our model as a bundle of characteristics which influence the decision of a participant to get their injection product. We also present a “None” option, since the injection will likely not be required for key populations. Should they choose none of the injection products we would assume that they will continue with whichever injection product they receive. In making their choice, the individual will weigh the relative utilities (a summation of the utility of each of the attributes for each choice) and finally make their decision (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that key populations in Uganda prefer high efficacy, lower side effects and consideration of confidentiality in their services. Duration was also a key attribute which was important in decision making, but preferences varied. Although a longer duration was typically preferred, some preferred shorter dosing periods to return more frequently for check-ups and tests. In the interviews, it was clear that key and priority populations needed motivational messaging to increase their interest and willingness to engage in HIV prevention services.

Participants emphasized the need for sufficient information about HIV prevention methods to best improve uptake of these products. This is further demonstrated by the finding that some participants appeared to be confused about the differences between the HIV vaccine and injectable PrEP, possibly due to miscommunication from people giving out information in communities or some information may be lost in translation from English to Luganda which does not have an exact translation for vaccine or injectable PrEP. Additionally, a variety of partnering organizations at different levels were mentioned as being needed to ensure that an HIV vaccine, or any other novel prevention product, is approved and effectively disseminated in a way that inspires trust in the population.

In summary, these findings emphasize the importance of tailored messaging, and of providing choices between different services to accommodate heterogeneity of preferences, and best ensure the uptake of HIV prevention services among key and priority populations. There is also a need to consult key populations themselves about HIV prevention issues to ensure that accurate information is attained about preferences as there are slight differences between what the people think compared to what providers, administrators and other experts in the field of HIV prevention think is important.

A similar mixed-method study on HIV prevention products found high interest among adolescent girls and young women in an HIV vaccine (34.7%) followed by oral PrEP (25.7%) and injectable PrEP (24.9%) compared to an implant or vaginal ring.[

20] While this is one of the few studies concerning preferences about a future HIV vaccine in Uganda, there have been several studies that have assessed willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials, as Uganda is one of the first locations in Africa to engage in HIV vaccine trials.[

21] Previous research in Uganda focusing on willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials have mostly found a high level of willingness (77-95%) to participate in the HIV trials.[22-26] However, this willingness was found to be curbed by concerns about vaccine safety, blood draws, and time required to participate, and increased by concerns of infidelity of current sexual partners.[

23,

27]

A discrete choice experiment on the future uptake of PrEP in different forms, including an injection, among fisherfolk in Uganda similarly found preferences for higher effectiveness, although in this study oral PrEP was preferred compared to an injection.[

28] This same study also found a significant preference for discretion of administration among men, although not among women. Another study conducted among key populations in seven countries around the world, including Uganda, found significant importance given to the route of administration for the acceptability of oral PrEP, although side effects did not appear to impact their acceptance.[

29] The study additionally emphasized the importance of efficacious and affordability for the participants to accept and uptake the product.[

29] Additionally, a study in rural Uganda and Kenya among demographically diverse populations found that providing patients with dynamic choice during their study increased prevention practices.[

30] This demonstrates that person-centered model incorporating structured choice may be an important tool for increasing prevention product uptake overall.

Among PSRHA, convenience issues were a major barrier to accessing prevention services, namely the pill burden, location, transportation, and side effects. Barriers which have arisen in other studies regarding PrEP uptake in Uganda include fear of side effects, inconvenience of taking pills often, weakening of the body due to the medication, aversion to taking drugs when healthy, stigma, perceived efficacy, and partner approval.[

31,

32] In one qualitative study in Uganda and Kenya, PrEP uptake was motivated by high perceived HIV risk and beliefs that PrEP use supported life goals.[

31] Another study in Uganda among community health workers found that counseling and motivational interviewing could significantly improve the uptake of PrEP.[

33]

A few studies in Uganda have also emphasized the importance of messaging in promoting HIV prevention efforts. For instance the World Health Organization’s MEASURE Evaluation found that it was effective to increase knowledge on prevention measures like condoms to increase disease prevention.[

34] Another study demonstrated the importance of tailoring messaging for HIV prevention promotion due to demographic differences leading to differences in misconceptions and attitudes.[

35] A study in Mukono, Uganda found that SMS messages as reminders have the potential to increase PrEP adherence which may be a good platform to explore for sending out informational and motivational messages.[

36]

One strength of the study is the breadth of expertise and diversity of participants represented in the sample. This study was additionally conducted at a key point in time, just before the release of a new long-acting PrEP injection in Uganda, right after the end of another unsuccessful yet well publicized HIV Vaccine trial that reached Phase III trials,[

37] and during that time Discovery Medicine HIV vaccine trials were being launched. A limitation of the study was that there was some risk of response bias, such as social desirability bias, since participants may have wanted to respond in a manner which they thought the researchers wanted to hear.[

38] While interviewers were trained on how to increase the comfort of participants and dispel power imbalances, it is impossible to eliminate, especially since there were two researchers in the room. Some participants may have felt inclined to try to please the interviewers by reporting higher willingness to take the HIV vaccine since they knew that was the focus of the research, so our findings of high acceptability of the vaccine should be considered critically and explored further in future studies which may not have as high interaction with facilitators, like anonymous online surveys. One last limitation was that the data analysts for the final thematic analysis were not from Uganda and therefore were less familiar with common practices there, putting the analysis at risk of missing some cultural contexts. However, to remedy this issue, the local Ugandan interviewers, the local Community Advisory Board and other Ugandan researchers were asked to review the analysis findings to ensure all results presented were culturally validated.

Future studies should focus on better understanding the intersectionality between the identities of key populations. In this study, many participants belonged to multiple key populations which made it challenging to understand which issues were unique to one group, or another, or maybe only to those in both groups. More purposeful sampling methods with a lens and a better understanding of the overlap between different key and priority populations in Uganda may help address this issue. Additionally, this study has shown that even before the release of a new product, especially due to the presence of clinical trials in these at-risk communities, people are already talking about new products, setting the groundwork for misinformation to emerge. Therefore, HIV prevention promotion programs should already start ensuring that knowledge about the progress in clinical trials are reported to communities in advance to inoculate against misinformation and ensure that rumors do not spread that are false. Future studies may also explore the added benefits of pairing evidence-based motivations with counseling and motivational interviewing techniques.

Future promotion campaigns for HIV prevention injections should consider revising the messaging strategies to differentiate between PrEP and the HIV vaccine. This could involve using simple, accessible language, avoiding technical jargon, and providing community-specific educational materials that explain how each intervention works, their purpose, and their differences. Finally, health promotion campaigns should be transparent about the political approval and dissemination process to help build trust and ensure the population knows when and how the product will reach them.