1. Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy (VH), defined as the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccination services, remains a major threat to global immunization goals [

1,

2]

. In East and Southern Africa, challenges in achieving high vaccination coverage rates persist, including VH, which undermines the effectiveness of vaccines critical for preventing high-burden diseases such as cervical cancer, hepatitis B, and COVID-19 [

3,

4,

5]. AGYW in this region face intersecting social, cultural, and informational vulnerabilities that shape their risk of VH [

6]. These include limited autonomy in health decision making, low levels of vaccine literacy, gender power dynamics that often prioritize community or parental and peer influence over individual agency [

7,

8] high exposure to misinformation particularly through social media platforms [

9,

10,

11] and due to low educational attainment and misconceptions about fertility and vaccine safety [

12]. Additional influences include mistrust in health systems [

13].

While VH is a global issue, its impact may be profound in vulnerable populations, particularly AGYW at risk for HIV. This is partly because they represent a crucial demographic at a high risk of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs), such as Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), Hepatitis B and C [

14]. VH may further hinder efforts to study, test, and deploy any future vaccines, including HIV vaccines.

The Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) acknowledges that many factors contribute to VH and that there is no unique group of determinants behind VH in all settings. According to the “3Cs” model, VH is linked to confidence, convenience, and complacency [

2]. Confidence is defined as trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines; the system that delivers them, including the reliability and competence of health services and health professionals; and the motivations of policymakers who guide recommended vaccines. Convenience is defined as the perceived level of access to vaccinations. It depends on physical availability, affordability, geographical accessibility, ability to understand information (language and health literacy), and appeal of immunization services (the quality of the service). Complacency is defined as the perceived risk of contracting the disease; when the perceived risk is low, vaccination may be thought of as an unnecessary preventive action.

Understanding the drivers of VH among AGYW in East and Southern Africa is essential to inform targeted, gender-responsive interventions to improve vaccine coverage. To understand VH among AGYW, IAVI included a VH module in the Multisite study for AGYW for future HIV vaccine and antibodies for prevention (MAGY) study, conducted in Uganda, Zambia, and South Africa. The MAGY study partly aimed to establish cohorts of AGYW for the evaluation of HIV prevention products in sub-Saharan Africa. This publication presents findings from MAGY that focused on assessing vaccine confidence among AGYW.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

This cross-sectional survey was embedded within the MAGY study, a prospective observational cohort study. MAGY was a flagship study under the IAVI ADVANCE program, enrolling AGYW (15-24 years old) between June 2023 and February 2024. Data on vaccine confidence were collected from each participant as part of the baseline assessment at enrollment.

2.2. Study Setting

We recruited participants from fishing communities around Lake Victoria, including both islands (Kimi and Nsazi) and landing sites (Kasenyi, Kigungu, and Nakiwogo), in Uganda; urban and peri-urban areas, including primary health care settings for single, sexually active mothers, and known hot spots for female sex workers (FSW) in Lusaka and Ndola, Zambia and from various healthcare facilities, youth groups, and community outreach activities in Rustenburg, a mining town in the North West Province, South Africa. Additional recruitment strategies across sites included peer referrals, participant recommendations, flyers and posters, and social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

2.3. Study Participants

Eligible participants were 15 to 24 years old, HIV negative, non-pregnant, reported sexual activity in the past three months, and met at least one criterion from a validated risk assessment questionnaire that adapted the VOICE risk assessment questionnaire (developed for adult women for PrEP trials in sub-Saharan Africa) [

15], and the Ayton risk assessment (designed for AGYW in rural South Africa) [

16]. HIV risk assessment was based on any one of the following: sexual intercourse in the past three months; use of contraception in the last year; perceived high HIV risk; ever been pregnant; low HIV knowledge; financial dependence (relying on sexual partners for financial support); and any alcohol or illicit drug use in the past year.

2.4. Data Collection

Trained study clinicians used a face-to-face structured interview questionnaire to obtain social demographic data such as age, level of education, marital status, religion, source of income, and information about vaccines. Information about VH was obtained through administering the validated Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS) [

17] which included 10 Likert scale questions assessing thoughts on general vaccine confidence; responses were coded 1 for “strongly disagree”, 2 “disagree”, 3 “neither disagree or agree”, 4 “agree” or 5 “strongly agree”. The ten questions included; 1) Vaccines are important for my health; 2) Vaccines are effective; 3) Being vaccinated is important for the health of others in the community; 4) All routine vaccinations recommended by the local authority on vaccination (this varied by country) are beneficial; 5) New vaccines carry more risks than others; 6) The information I receive from the local authority on vaccination is reliable & trustworthy; 7) Getting vaccines is a good way to protect me from diseases; 8) Generally, I do what my doctor or health care provider recommends about vaccines for me; 9) I am concerned about serious adverse effects of vaccines; and 10) I don’t need vaccines for diseases that are not common anymore.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were electronically captured in the REDCap (Westlake, TX, USA) software database, and data analysis was done using STATA SE version 18 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Participant characteristics were summarized overall and by study site.

To determine the latent traits or factors in the VHS, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on half the sample (n = 606; randomly selected) using Principal Component Factor method (PCF) and maximum likelihood (ml) method for the factor loadings of the VHS with oblique rotation (Promax). Oblique rotation was chosen because the factors were expected to be correlated, allowing for a more accurate representation of the underlying structure. To examine model fit, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed on the second half sample (n = 607; randomly selected). To determine the internal consistency, we used Cronbach’s alpha to determine scale reliability.

To determine the level of vaccine confidence for each item on the VHS, we constructed a 5-point scale of the class intervals for interpreting the VHS items’ average score. We reverse-coded items 1,2,3,4,6,7, and 8 on the VHS to ensure that higher values consistently represent lower vaccine confidence. Scores (1-5) were grouped into class intervals to simplify analysis and interpretation. The interval width was calculated by dividing the score range (5-1=4) by the number of scores (5), resulting in a width of 0.8. Intervals were created by adding this width to the minimum score (1) (

Table 1). Average scores, frequencies, and percentages were then calculated. This approach follows best practices in interpreting Likert scale data by converting continuous-like scores into meaningful categorical groupings, facilitating clearer insights and comparisons [

18]

A composite score for each respective factor was calculated by taking the mean values of its respective component questions. These scores were then dichotomized: values less than or equal to 2 (representing “Strongly Agree” or “Agree” responses, with regards to confidence in vaccines or risk tolerance) were coded as 0, while values greater than 2 (representing “Neither Agree nor Disagree,” “Disagree,” or “Strongly Disagree” responses) were coded as 1.

Bivariate logistic regression analyses were performed between covariates and both hesitancy scores (confidence and risk tolerance). We analyzed individual associations between demographic characteristics (including country, age, relationship status, religious affiliation, education level, source of income, and school attendance) and each outcome and calculated crude odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and p-values. Covariates that showed statistical significance (p < 0.2) were then included in multivariate logistic regression models to identify factors independently associated with vaccine confidence. To control potential confounding factors, adjusted odds ratios were calculated for significant predictors.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

A total of 1213 AGYW were interviewed, 656 (54%) were aged between 15-19 years. The mean age was 19.4 (SD±2.6) years. The majority of AGYW, 1197 (99%), previously attended school, while only 351 (29%) were still in school. Most, 1107 (91%) of the AGYW had never married, and 750 (62%) were single with steady sexual partners. Details of the demographic characteristics are depicted in

Table 2.

3.2. Responses to Vaccine Hesitancy Scale Items

The MAGY cohort showed strong positive beliefs about vaccines, with favourable mean scores regarding vaccines’ importance for personal health (1.77) and community benefit (1.78). They strongly agreed that vaccination is effective for disease prevention (1.72). However, they expressed significant concerns about vaccine safety, with a high mean score of 3.56 regarding serious adverse effects. They also showed moderate confidence towards new vaccines, perceiving them as riskier than established vaccines (mean score 2.74).

Most AGYW agreed or strongly agreed that vaccines were important for their health (94%); vaccines were effective (87%); being vaccinated was important for the health of others in the community (93%); and all routine vaccinations recommended by national vaccination programs were beneficial (91%). About two-thirds (66%) of the AGYW agreed or strongly agreed that they were concerned about the serious adverse effects of vaccines, while 30% agreed or strongly agreed that they don’t need vaccines for diseases that are not common anymore. Details of the responses and average scores to the VHS items are shown in

Table 3 below.

3.3. Structure, Model Fit, and Internal Consistency of the VHS.

To examine the structure of our VHS items, we performed Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Promax rotation was used in the EFA because it allows factors to correlate with each other, which is more realistic for behavioral constructs and helps identify a clearer factor structure. The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) remained unrotated since it tested a pre-specified factor structure based on theory, making rotation unnecessary. The analysis revealed two distinct factors that describe the 10 VHS items, with Eigenvalues greater than 1. These two factors together accounted for 52% of the total variance in the items. We describe these two factors as “vaccine confidence” and “risk tolerance”. Vaccine confidence was dominant, explaining 40% of the variance, while risk tolerance explained 12%. As shown in

Table 4, 7 VHS items were loaded on vaccine confidence, and two items were loaded on risk tolerance. Only 9 of the 10 VHS items loaded on our factors. Item 9, “I am concerned about the serious adverse effects of vaccines,” didn’t load on either factor.

We conducted a CFA on two sets of the VHS items: one with nine items, excluding item 9 (“I am concerned about the serious adverse effects of vaccines”), and another with all ten items included. Using data from 607 participants, the analysis revealed that item 9 had a very weak loading of 0.14 on the risk tolerance factor. The CFA results demonstrated that all the remaining nine items loaded strongly onto their respective factors, providing robust support for our two-factor model, as detailed in the test statistics presented in

Table 5.

To assess the internal consistency of both factors, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha based on data from 1213 participants. For vaccine confidence, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85, indicating excellent scale reliability. However, for risk tolerance, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.44, which is considered poor. This low value is likely due to the small number of items on the risk tolerance factor, as scale reliability typically improves with more items. On including item 9 of our VHS to risk tolerance, our Cronbach’s alpha dropped to 0.34, implying that question 3 reduces the reliability of this factor. The correlation between the two factors was 0.26, suggesting a weak association and indicating that they represent separate dimensions of VH.

Table 4.

Exploratory Factor analysis, showing rotated and unrotated factor loadings (N=606).

Table 4.

Exploratory Factor analysis, showing rotated and unrotated factor loadings (N=606).

Vaccine Hesitancy Scale Items |

Rotated EFA loadings (blanks for values less than 0.32) |

CFA unrotated loadings |

| Factor1: confidence |

Factor2: risk tolerance |

Factor1: confidence |

Factor2: risk tolerance |

| Vaccines are important for my health (R) |

0.68 |

|

0.75 |

|

| Vaccines are effective (R) |

0.66 |

|

0.57 |

|

| Being vaccinated is important for the health of others in the community (R) |

0.78 |

|

0.70 |

|

| All routine vaccinations recommended by the local authority on vaccination are beneficial (R) |

0.68 |

|

0.71 |

|

| New vaccines carry more risks than others. |

|

0.54 |

|

0.60 |

| The information I receive from the local authority on vaccination is reliable & trustworthy (R) |

0.53 |

|

0.68 |

|

| Getting vaccines is a good way to protect me from disease (R) |

0.76 |

|

0.75 |

|

| Generally, I do what my doctor or health care provider recommends about vaccines for me (R) |

0.67 |

|

0.54 |

|

| I am concerned about the serious adverse effects of vaccines. |

|

|

|

|

| I don’t need vaccines for diseases that are not common anymore. |

|

0.42 |

|

0.53 |

Note: EFA, Exploratory Factor Analysis. Method: maximum likelihood. Participants are randomly selected. 2 Factors.

Rotation: oblique Promax (Kaiser off).

CFA: Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Method: maximum likelihood. |

Table 5.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of putative latent factors (n=606).

Table 5.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of putative latent factors (n=606).

| Factors |

Eigen Value |

Proportion |

| Factor1 |

4.24 |

0.40 |

| Factor2 |

1.25 |

0.12 |

| Factor3 |

0.91 |

0.09 |

| Factor4 |

0.74 |

0.07 |

| Factor5 |

0.69 |

0.07 |

| Factor6 |

0.61 |

0.06 |

| Factor7 |

0.51 |

0.05 |

| Factor8 |

0.44 |

0.04 |

| Factor9 |

0.43 |

0.04 |

| Factor10 |

0.37 |

0.04 |

| Note: Method: principal-component factor method to describe latent factors in half the cohort (randomly selected). Retained 2 factors. We retain factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 (the Kaiser Criterion). No Rotation. |

Table 6.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Fit statistics for a 2-factor model.

Table 6.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Fit statistics for a 2-factor model.

| |

chi2 |

RMSEA |

CFI |

TLI |

SRMR |

| Model 1 with 9 VHS items (Excluding item 9) |

127.88 |

0.08 |

0.94 |

0.91 |

0.04 |

| Model 2 with 10 VHS items |

169.10 |

0.08 |

0.92 |

0.89 |

0.06 |

| Value for good fit |

Low value |

<0.06 |

≥0.95 |

≥0.95 |

<0.08 |

| Note. Chi2: Chi-Square Test Statistic, RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, CFI: Comparative Fit Index, TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index, SRMR: Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

3.4. Relationship Between Demographic Characteristics and Vaccine Confidence

3.4.1. Correlates of Vaccine Confidence.

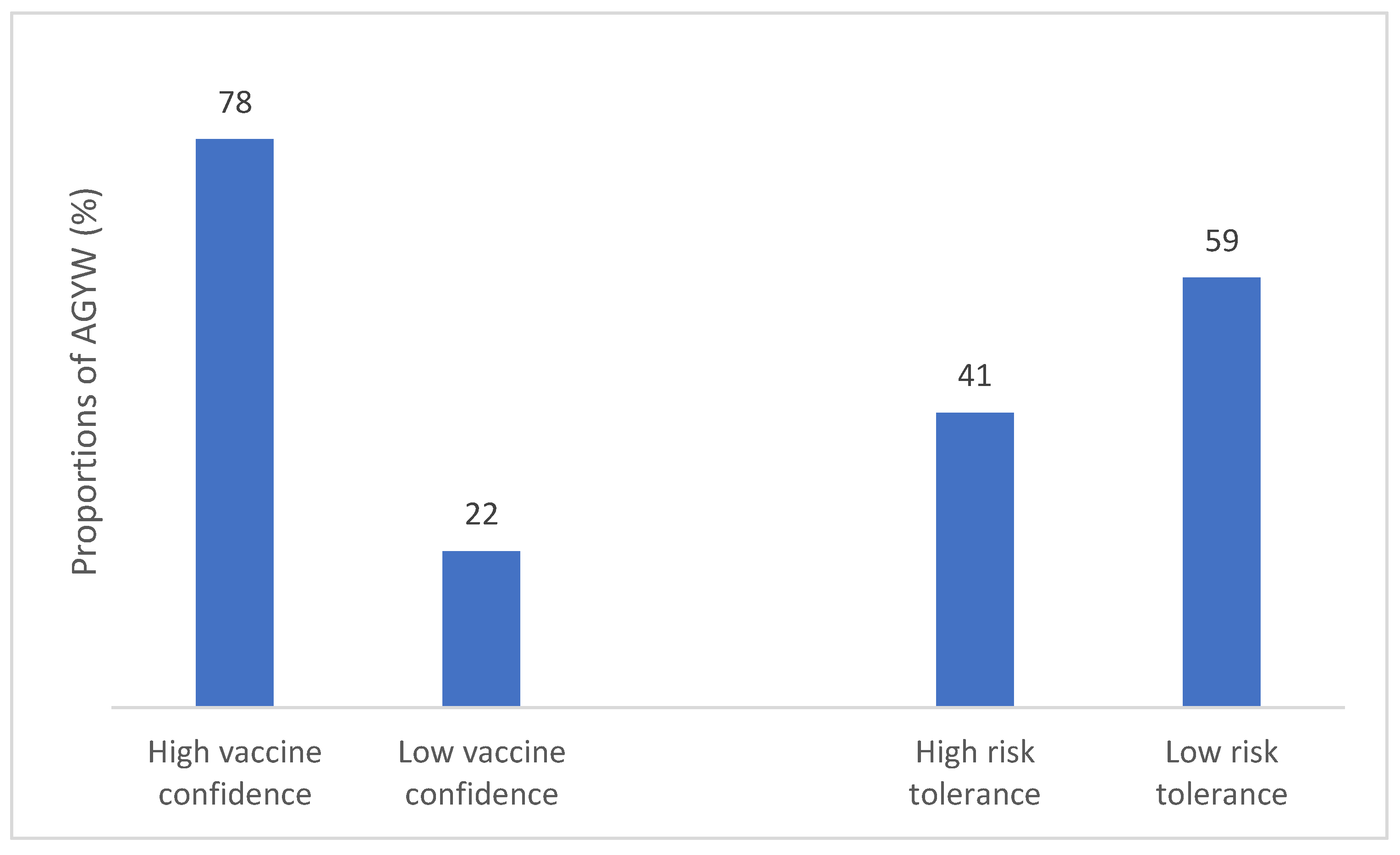

As shown in

Figure 1, a total of 951 (78.4%) of AGYW exhibited high vaccine confidence. We observed significant variations in vaccine confidence levels among countries, with AGYW in Zambia (adjusted odds ratios (aOR): 0.26, 95% CI: 0.18 – 0.39) showing a lower likelihood of vaccine confidence followed by Uganda [aOR]: 0.44 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.29 – 0.66) in comparison to South Africa. Participants not currently in school showed lower vaccine confidence compared to those who were in school (aOR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.50 – 0.97).

Participants with formal employment (aOR 0.55, 95% CI: 0.31 – 0.96) and those receiving Support/assistance (aOR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.40 – 0.87) showed lower vaccine confidence than the participants with no source of income.

Table 7 shows the details of demographic characteristics and vaccine confidence.

3.4.2. Correlates of Risk Tolerance

As shown in

Table 8, 41% of respondents demonstrated high risk tolerance. There was a significant variation in risk tolerance levels across the three countries, with Zambia (aOR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.16 – 0.31) showing notably lowest risk tolerance and Uganda (aOR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.37 – 0.76) compared to South Africa.

Participants in formal employment (aOR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.26 – 0.73), informal employment (aOR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.33 – 0.94) and those receiving support/assistance (aOR 0.39, 95% CI: 0.26 – 0.60) showed significantly lower risk tolerance than the participants with no source of income.

Participants who were not in school showed lower risk tolerance compared to those who were in school (OR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.48 – 0.91). Details are shown in

Table 8 below.

4. Discussion

Vaccination is one of the most cost-effective strategies to reduce the global burden of infectious diseases. In this cohort of AGYW, we observed a high level of vaccine confidence and risk tolerance for vaccines. Specifically, greater than 90% of AGYW believed that vaccines were effective, safe, and that getting vaccinated was important to protect themselves and the community against diseases. This is a promising finding with significant public health implications, as high vaccine confidence and risk tolerance could ultimately lead to increased vaccine uptake, hence reducing the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases. While the MAGY study aimed at preparing a cohort of AGYW for future HIV vaccine and broadly neutralizing antibody studies, the high level of vaccine confidence and risk tolerance reported in this study holds potential for future acceptance of HIV vaccines. A systematic review about knowledge, attitudes, and practices on adolescent vaccination among adolescents in Africa reported high acceptability of vaccines among adolescents [

19]. On the contrary, Bing Wang et al. reported lower levels of vaccine confidence among adolescents, with adolescents being less likely to believe that vaccines are beneficial and/or safe [

20]. However, the study by Bing Wang et al looked at vaccine confidence among adolescent males and females, and the males were found to be less confident about vaccines than the females. It also compared vaccine confidence among adolescents and adults, but never examined vaccine confidence among adolescents alone.

Despite ongoing efforts to promote vaccination uptake, VH remains a significant issue [

14,

21] and has been identified as one of the ten leading global health threats by the WHO [

1]. To address this challenge, the WHO recommends regularly investigating vaccine confidence. Generally, vaccine confidence among adolescents has been under-researched [

22,

23]. Most of the recent studies have looked at vaccine confidence about COVID-19 vaccines [

3,

24], while others focus on HPV vaccines [

7,

25,

26,

27,

28]. This study is among the first to assess vaccine confidence among AGYW at risk of HIV acquisition in sub-Saharan Africa using the VHS. The VHS has been widely used in different populations to assess VH and is more reliable in measuring “lack of confidence” than “risk tolerance” [

29,

30]. It demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity when applied to AGYW at risk of HIV, a finding similar to that of Shapiro

et al [

17]. In our study, we found strong scale reliability for the “vaccine confidence” factor, with a high Cronbach’s alpha (0.85), while the “vaccine risk tolerance” factor showed poor reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.44.

We observed several covariates that correlated both with vaccine confidence and tolerance for risk. We found that AGYW living in Zambia were less likely to accept vaccines than those living in Uganda and South Africa. The AGYW from Zambia also demonstrated a lower risk tolerance for vaccines. This finding is not surprising, as vaccine confidence has been reported to vary from time to time and place to place. Geographical location could significantly influence vaccine confidence. Access to healthcare may vary from region to region, and this could directly affect access to information. Lack of access to health-related information may affect vaccine confidence [

13,

31]. Cultural beliefs and values may vary from region to region and may influence vaccine confidence, e.g., some cultures may be skeptical about vaccination [

8,

32].

While several studies have reported an association between the level of education and VH [

33], we observed that there was no association between the level of education and vaccine confidence. A study by Wegner et al among mothers aged 21-40 years in India reported an association between the level of education and vaccine confidence. Women with a high school education were considerably more likely to report high confidence in vaccines than women with less than a high school education [

34]. The relationship between the level of education and VH could be influenced by various factors, including knowledge, perception, access to information, trust in healthcare systems, and sociocultural contexts [

35]. AGYW with lower education levels may face challenges in accessing reliable health information or understanding and interpreting public health information. This could make them more susceptible to misinformation or confusion about vaccines, potentially contributing to VH. Furthermore, AGYW with no or less education might not fully understand the severity of vaccine-preventable diseases or may underestimate the potential risks of not vaccinating, leading to complacency [

36]. This study, however, reported that AGYW who were not in school showed lower vaccine confidence compared to those who were in school. We did not observe any association between

vaccine hesitancy (VH) and

level of education, likely because more than

three-fourths of the MAGY cohort were either currently in

secondary school, had

completed secondary school, or were enrolled in

tertiary education. As a result, the educational status of participants was skewed toward AGYW with at least some

high school education. Additionally, recruitment for the MAGY study began shortly after the

peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a period during which communities had experienced first-hand the

life-saving impact of vaccines through the scale-up of COVID-19 vaccination efforts. This likely reduced the influence of formal education as the sole source of vaccine information, as community members were exposed to messaging on the benefits of vaccination from

multiple sources beyond formal schooling. However, we did observe that AGYW who were

currently in school had

significantly higher vaccine confidence compared to those who were not. This may be attributed to the role that

formal education played in vaccine education during the pandemic, reinforcing positive perceptions about vaccination.

We further report that the source of income was associated with vaccine confidence and risk tolerance. The AGYW who had no source of income were more likely to be vaccine-confident than those who were working. AGYW with formal employment and those receiving support/assistance showed significantly lower vaccine confidence than the participants with informal or no source of income. The association between socioeconomic status and vaccine confidence is multifactorial [

37]. Our finding that low socioeconomic status was associated with vaccine confidence could demonstrate the trust in healthcare systems among these AGYW. Individuals with low socio-economic status might heavily rely on information provided by the healthcare providers, thus building trust in vaccines and the healthcare systems that deliver them [

38].

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First and foremost, our study population included AGYW at risk for HIV, and we screened out AGYW who were pregnant, living with HIV, and lower risk (typically those who did not report sexual activity in the previous three months). Thus, our study population should not be considered broadly representative of Ugandan, Zambian, and South African AGYW. However, the study benefits from a relatively large sample of diverse AGYW across three countries. Secondly, ‘’vaccine confidence’’ items on the VHS were worded positively, and all ‘‘risk tolerance’’ items were worded negatively. Consequently, the focus and content of the items on the scale got intertwined. Therefore, the item that was eliminated for not loading on either factor could have been due to the intertwining. Thirdly, only two items loaded on the second factor assessing ‘’tolerance for risks’’. Scales with factors that are composed of less than three items are considered unstable, and calculating Cronbach’s alpha for a two-item sub-scale has limitations. Fourthly, this study assessed responses to the VHS for vaccines in general; thus, these findings do not represent confidence in specific vaccines. It is well known that vaccine confidence varies according to the type of vaccine. Finally, this study is cross-sectional, and it is therefore not advisable to draw causal conclusions between our covariates and the respective correlated elements of confidence.

5. Conclusions

Our study reports that the VHS consisted of two factors, including “vaccine confidence” and “tolerance for risks.” However, the few items on the fewer items on the risk tolerance could affect the scale reliability in measuring concerns and risks associated with vaccines. Vaccine confidence among AGYW was driven more by the trust in vaccine safety and the need to protect communities against diseases. This highlights the importance of addressing the perceptions and attitudes that the AGYW may have about vaccines, particularly newer ones. Demographic factors such as being in school, socioeconomic status, and country of origin were associated with vaccine confidence levels among AGYW in our study. Therefore, future interventions aimed at increasing vaccine uptake among AGYW should focus on improving education about vaccine safety tailored to the audience (e.g., cultural background, education, and socio-economic status), addressing specific concerns related to side effects, and leveraging trusted community leaders to build confidence in vaccines. Additionally, health communication strategies should be tailored to address the unique concerns of AGYW who may be more vulnerable to vaccine misinformation. This is crucial for informing future interventions aimed at enhancing vaccine uptake in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., A.N. and M.A.P.; methodology, N.K., M.A.P. and J.A.M.; software, N.K.; validation, J.B., and formal analysis, J.A.M., M.A.P.; investigation, X.X.; resources, M.K., S.C.F.,; data curation, C.K., K.M., N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K., and J.A.M; writing—review and editing, A.S., W.K., M.K., A.N., M.A.P. J.M., B.O., K.O., M.I., P.M., and V.E.; visualization, N.K., J.A.M., A.S.; supervision, A.S., W.K., P.M., M.K.; project administration, A.S., W.K., P.M., K.O., funding acquisition, M.K., P.M., B.O., K.O., S.C.F., and W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by IAVI and made possible by the support of many donors, including the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The full list of IAVI donors is available at

http://www.iavi.org. The contents of this manuscript are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research and Ethics Committee (UVRI-REC) approval number GC/127/947, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) approval number HS2741ES, University of Zambia Biomedical Research Committee (Ref No. 3414-2022) and National Health Research Authority (Ref: NHREB0006/05/02/2023), in Zambia. In South Africa, the study was reviewed and approved by the University of Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref No. 221114B) and the Research Committee of the Northwest Provincial Department of Health.

Informed Consent Statement

Written Informed consent was sought from AGYW aged 18 years and above. Both parental consent and assent were sought for all minors, while emancipated minors assented to participate in the study. All participants’ data were anonymized to ensure confidentiality, and strict measures were taken to protect participant privacy throughout the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study participants. We wish to acknowledge the support from the University of California, San Francisco’s International Traineeships in AIDS Prevention Studies (ITAPS), U.S. NIMH, R25MH123256. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. IAVI participated in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The corresponding authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. IAVI’s donors had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. We further acknowledge the research teams at UVRI-IAVI HIV vaccine program, the Center for Family Health Research in Zambia (CFHRZ), and the Aurum Institute for collecting the data from the research participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| 95%CI |

95% Confidence Interval |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| UVRI |

Uganda Virus Research Institute |

| IAVI |

International AIDS Vaccine Initiative |

| UNCST |

Uganda National council for science and Technology |

| USAID |

United States Agency for International Development |

Appendix 1

Socio-demographic questionnaire

Appendix 2

Vaccine Hesitancy module questionnaire

References

- WHO. Ten threats to global health in 2019. 2019 [cited 2024 27 Sep 2024].

- MacDonald, N.E. , Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 2015. 33(34): p. 4161-4164. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. , et al., COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its determinants among sub-Saharan African adolescents. PLOS global public health, 2022. 2(10): p. e0000611. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J. , et al., A call for low-and middle-income countries to commit to the elimination of cervical cancer. The Lancet Regional Health–Americas, 2021. 2. [CrossRef]

- Ochola, E. , et al., High burden of hepatitis B infection in Northern Uganda: results of a population-based survey. BMC public health, 2013. 13(1): p. 727. [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, G.C. , et al., Examining enablers of vaccine hesitancy toward routine childhood and adolescent vaccination in Malawi. Global health research and policy, 2022. 7(1): p. 28. [CrossRef]

- Rujumba, J. , et al., Why don’t adolescent girls in a rural Uganda district initiate or complete routine 2-dose HPV vaccine series: Perspectives of adolescent girls, their caregivers, healthcare workers, community health workers and teachers. PloS one, 2021. 16(6): p. e0253735. [CrossRef]

- Sacre, A. , et al., Socioeconomic inequalities in vaccine uptake: A global umbrella review. PLoS One, 2023. 18(12): p. e0294688. [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D. , et al., Beliefs, behaviors and HPV vaccine: correcting the myths and the misinformation. Preventive medicine, 2013. 57(5): p. 414-418.

- Ortiz, R.R., A. Smith, and T. Coyne-Beasley, A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 2019. 15(7-8): p. 1465-1475. [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, G.C. , et al., Caregivers’ willingness to vaccinate their children against childhood diseases and human papillomavirus: A cross-sectional study on vaccine hesitancy in Malawi. Vaccines, 2021. 9(11): p. 1231. [CrossRef]

- Essoh, T.-A. , et al., Exploring the factors contributing to low vaccination uptake for nationally recommended routine childhood and adolescent vaccines in Kenya. BMC Public Health, 2023. 23(1): p. 912. [CrossRef]

- Unfried, K. and J. Priebe, Vaccine hesitancy and trust in sub-Saharan Africa. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 10860. [CrossRef]

- English, A. and A.B. Middleman, Adolescents, young adults, and vaccine hesitancy: who and what drives the decision to vaccinate? Pediatric Clinics, 2023. 70(2): p. 283-295.

- Giovenco, D. , et al., Assessing risk for HIV infection among adolescent girls in South Africa: an evaluation of the VOICE risk score (HPTN 068). African Journal of Reproduction and Gynaecological Endoscopy, 2019. 22(7). [CrossRef]

- Ayton, S.G., M. Pavlicova, and Q. Abdool Karim, Identification of adolescent girls and young women for targeted HIV prevention: a new risk scoring tool in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Scientific reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 13017. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, G.K. , et al., The vaccine hesitancy scale: Psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine, 2018. 36(5): p. 660-667. [CrossRef]

- Alkharusi, H. , A descriptive analysis and interpretation of data from Likert scales in educational and psychological research. Indian Journal of Psychology and Education, 2022. 12(2): p. 13-16.

- Abdullahi, L.H. , et al., Knowledge, attitudes and practices on adolescent vaccination among adolescents, parents and teachers in Africa: A systematic review. Vaccine, 2016. 34(34): p. 3950-3960. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. , et al., Adolescent confidence in immunisation: assessing and comparing attitudes of adolescents and adults. Vaccine, 2016. 34(46): p. 5595-5603. [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, P.G. , et al., Prevalence and characteristics of HPV vaccine hesitancy among parents of adolescents across the US. Vaccine, 2020. 38(38): p. 6027-6037. [CrossRef]

- Cadeddu, C. , et al., Understanding the determinants of vaccine hesitancy and vaccine confidence among adolescents: a systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2021. 17(11): p. 4470-4486. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J. , et al., The demographics of vaccine hesitancy in Shanghai, China. PLoS One, 2018. 13(12): p. e0209117.

- Willis, D.E. , et al., COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among youth. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 2021. 17(12): p. 5013-5015. [CrossRef]

- Omayo, L. , et al., Determinants of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Journal of the African Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, 2023. 2: p. 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Bitariho, G.K. , et al., Knowledge, perceptions and uptake of human papilloma virus vaccine among adolescent girls in Kampala, Uganda; a mixed-methods school-based study. BMC pediatrics, 2023. 23(1): p. 368. [CrossRef]

- Nakibuuka, V. , et al., Uptake of human papilloma virus vaccination among adolescent girls living with HIV in Uganda: A mixed methods study. Plos one, 2024. 19(8): p. e0300155. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, L. , et al., Encouraging improvement in HPV vaccination coverage among adolescent girls in Kampala, Uganda. PloS one, 2022. 17(6): p. e0269655. [CrossRef]

- Luyten, J., L. Bruyneel, and A.J. Van Hoek, Assessing vaccine hesitancy in the UK population using a generalized vaccine hesitancy survey instrument. Vaccine, 2019. 37(18): p. 2494-2501. [CrossRef]

- Domek, G.J. , et al., Measuring vaccine hesitancy: Field testing the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy survey tool in Guatemala. Vaccine, 2018. 36(35): p. 5273-5281. [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, A. , et al., Declining trends in vaccine confidence across sub-Saharan Africa: A large-scale cross-sectional modeling study. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 2023. 19(1): p. 2213117. [CrossRef]

- Mwiinde, A.M. , et al., Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among adolescents and youths aged 10-35 years in sub-Saharan African countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one, 2024. 19(10): p. e0310827. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M. , et al., Assessing vaccine hesitancy using the WHO scale for caregivers of children under 3 years old in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 2023. 11: p. 1090609. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.L. , et al., Demographics of vaccine hesitancy in Chandigarh, India. Frontiers in medicine, 2021. 7: p. 585579. [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.A. , et al., Drivers of hesitancy towards recommended childhood vaccines in African settings: a scoping review of literature from Kenya, Malawi and Ethiopia. Expert Review of Vaccines, 2021. 20(5): p. 611-621. [CrossRef]

- Obohwemu, K., F. Christie-de Jong, and J. Ling, Parental childhood vaccine hesitancy and predicting uptake of vaccinations: a systematic review. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 2022. 23: p. e68. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, F.S.M., Y. Kew, and F.M. Moy, Vaccine hesitancy among parents in a multi-ethnic country, Malaysia. Vaccine, 2017. 35(22): p. 2955-2961. [CrossRef]

- Périères, L. , et al., Reasons given for non-vaccination and under-vaccination of children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 2022. 18(5): p. 2076524. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).