EU requirements are for mutual adherence to good practices in agriculture, conservation of natural resources, transparency and predictability. Information technology and digitization are the tools with which a number of activities can be optimized and these requirements can be met. One of the main reasons for the unclear and partial application of information technology in agriculture stems from the fact that farmers are not aware of how it works and can complement each other to benefit them in practice. Their misunderstanding is often accompanied by the expression: “This is too complicated...”. Farmers focus mostly on short-term results and do not pay serious attention to long-term goals. Current farming practices are influenced by wrong incentives, lack of sufficient training and modern knowledge.

Currently offered consulting services to farmers cannot fully provide expert consulting regarding the innovations in the application of digital technologies in agriculture. Usually, the advice that Bulgarian farmers receive regarding innovations is based on foreign experience and products, which are mostly unproven for the conditions in Bulgaria. In the conditions of intensively developing digital technologies, agriculture is also an active environment for their application. The possibilities of these new technologies are able to provide agriculture with solutions through which it becomes possible to ensure and maintain a balance between protecting natural resources and meeting the needs of the rapidly growing population of the planet for quality food and raw materials for industry by taking the right management decisions at different levels of management.

In this way, farmers could be successful despite their differences in knowledge and experience. Even the novice farmer can quickly become successful in his activity, something that other of his colleagues have achieved after years of experience and in which they have not infrequently relied on the “trial and error” method.

The basis of the predominant part of digital technologies in agriculture is the use of mathematical models proven by science and practice, describing separately or in combination various physical, mechanical, biological and other processes occurring during the cultivation of agricultural crops. In this way, technologies in agriculture can acquire adaptive, resp. proactive nature, i.e., to respond promptly to changes in the conditions of their application and to adjust the expected final result. The sustainability of such technologies largely depends on maintaining a constant connection with the environment in which they are implemented. By developing adequate mathematical models, it is possible to predict and adapt processes and phenomena manifested at a later stage as a result of changes in the factors influencing the object of impact.

Proactive technologies provide different opportunities for decision-making at each stage, i.e. at any stage of plant development or state of resources used. Successful decision-making will depend not only on whether farmers have already accumulated knowledge and experience on the correct application of good practices in growing their crops, but also on the analysis of factual material, the conclusions of which are a proposal for decision-making.

Every advance in basic understanding of plant growth and development, as well as every advance in instrumentation, leads to improvements in methods of analysis and interpretation.

1.1. Antecedent Condition

Current advisory services for agricultural producers cannot fully provide expert advice on the latest developments in the application of digital technologies in agriculture. Usually, the advice that Bulgarian farmers receive regarding innovations is based on foreign experience and products, which are mostly unproven for the conditions in Bulgaria.

In the recent past and currently, in the majority of Bulgarian farms, the entire cultivated area is considered as a uniform unit - if it is time to irrigate, the entire field is watered, if fertilization is necessary - the entire area is fertilized with the same fertilizer rate. In reality, however, not all parts of the field have the same needs, due to the heterogeneity of the soil.

Acquiring, analyzing and applying accurate information in the form of analytics is key to making the right decisions. Soil testing is an important tool related to the application of technologies for growing crop plants. The adequacy of soil analyzes largely depends on the capabilities of their methodology to determine the non-uniform nature of the soil in a given field.

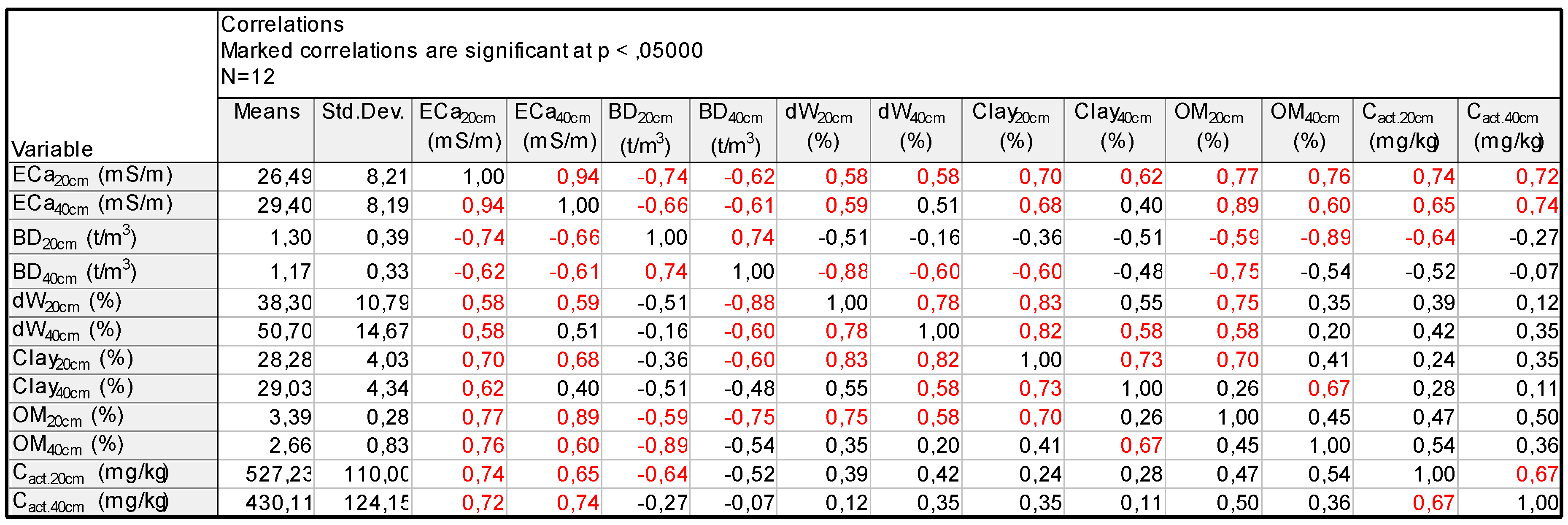

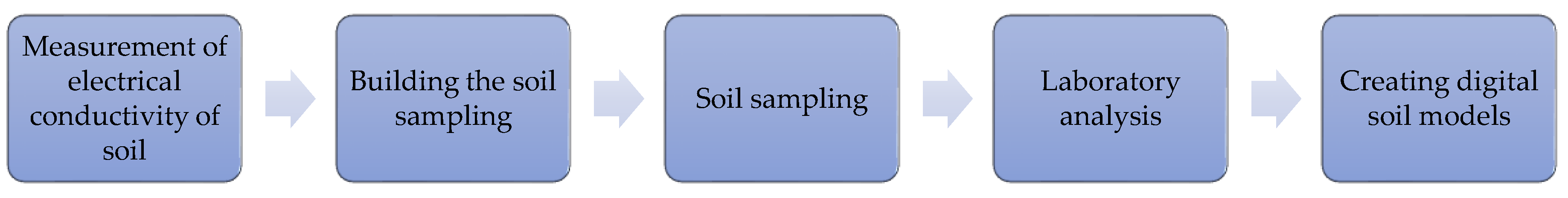

The basis of the existing methods for soil analysis is the classical methodology with its three main stages (

Figure 1), which include:

Stage 1. Building the soil sampling – the surveyed field is divided into modular units (plots) of certain sizes, in which the number and locations for drilling are marked along a pre-defined trajectory. Generally, the “W-scheme” is suitable for most plot shapes and sizes, but “Z-scheme” or “X-scheme” also apply. Thus, one soil sample should be formed from each modular unit, obtained after mixing the samples from the drilling sites. The goal in drawing up a drilling scheme is to capture the soil diversity in the surveyed field. The number of drilling sites in a modular unit varies from 10 to 40, and the size of a modular unit from 0.5 ha to 10-12 ha [

23,

26,

39]; the surveyed field is divided into modular units (plots) of certain sizes, in which the number and locations for drilling are marked along a pre-defined trajectory. Generally, the “W-scheme” is suitable for most plot shapes and sizes, but “Z-scheme” or “X-scheme” also apply. Thus, one soil sample should be formed from each modular unit, obtained after mixing the samples from the drilling sites. The goal in drawing up a drilling scheme is to capture the soil diversity in the surveyed field. The number of drilling sites in a modular unit varies from 10 to 40, and the size of a modular unit from 0.5 ha to 10-12 ha [

23,

26,

39];

Stage 2. Soil sampling – it is done manually or mechanized using special tools that extract samples from soil layers with a depth of 0-30 cm; 30-60 cm and 60-90 cm, according to the purpose of the surveyed field and the goals of the analysis;

Stage 3. Laboratory analysis – soil samples collected from the field are subjected to laboratory tests according to established procedures and standards [

9]. The analysis of the results compares the reported with the reference values of the observed indicators and on this basis a generalized assessment of the soil condition is formed and relevant recommendations can be prepared.

A mandatory requirement for the classic method is soil sampling, and the reliability of the results depends on the sampling density [

27]. This determines the representativeness of the soil material collected. Due to the complexity of ensuring the representativeness of soil samples in Stage 1 of the classical method, modern specific developments such as global navigation satellite system (GNSS), global positioning system (GPS), geographic information systems (GIS) are being used. According to a set algorithm, these systems can divide the field into modular units of a certain shape and size, which forms a network of drilling points on the field. The network density, resp. the density of sounding points is set by the size of the modular unit, which typically ranges from 1.6 to 5ha.

Apart from the stages, the common thing in the individual variants of the classical method is that it works with the use of samples (partial samples) of the soil, which are relied upon to ensure the representativeness and reliability of the analysis results.

1.2. Essence of the Digital Soil Cube (DSC) Method

In the sense of the digital transformation in agriculture, classical soil analysis cannot provide a high enough degree of precision. It also takes a lot of time and resources, which is why farmers often neglect it. A fact that is at odds with the EU’s requirements for mutual adherence to good practices in agriculture.

The idea of the DSC method is related to digitalization of soil analysis. A key point in it is the replacement of the soil sample from the so-called “Digital soil cube” which, by means of mathematical models, provides timely information on the condition of the soil.

To develop the method, a cybernetic approach known from science is applied. The approach is based on the principle of the black box, according to which any object can be studied and managed only by its reactions caused by one or other external influences, without knowing the processes and phenomena that take place inside the object [

6,

7]. The application of this approach is also related to the use of probabilistic statistical methods [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7], in which the reactions shown by the object are viewed as a random event, a random variable or a random process. At the so-called poorly organized systems (objects) including soil, these methods are a means of obtaining objective information. The DSC methodology uses the elements of mathematical statistics, correlation analysis, dispersion analysis and regression analysis [

2,

6,

7].

The reactions of the object (the soil) and the external influences are considered as random quantities that describe a given feature (property) of the general population (the soil in the entire field). A given property of the soil is seen as a reaction of the soil, and the soil itself as an object with an external influence. The entire soil survey process is passive in terms of the statistical data collected [

2,

6,

7]. The methodology for implementing the DSC is distinguished by a dynamic functional scheme (

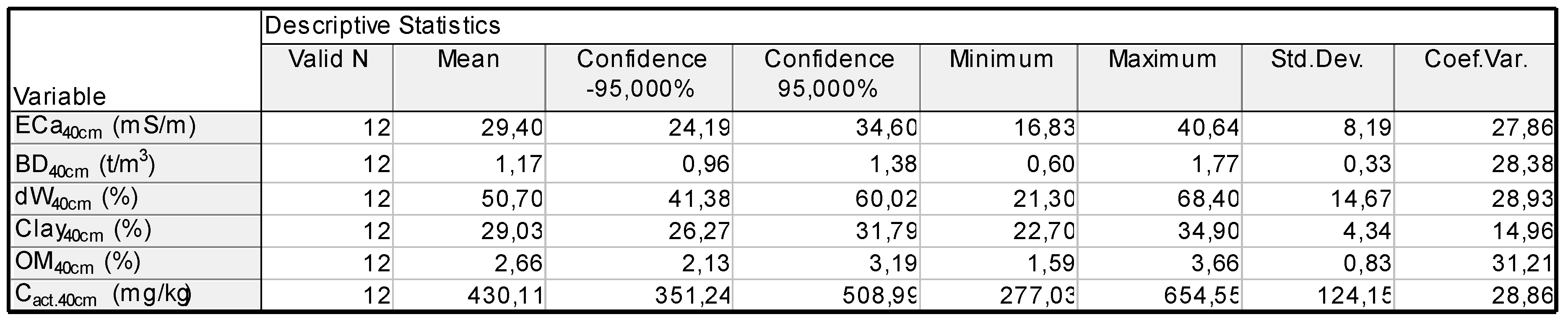

Figure 2). In its entirety, this functional scheme consists of five stages that must be followed to obtain the final digital soil model. Once created, the digital soil model allows the functional scheme to be reduced to two stages - the first and the last, and the soil analysis itself takes on a proactive nature.

Stage 1. Measurement of the electrical conductivity of the soil- one of the significant measurements that can be used as an indicator of soil fertility and digitized is its electrical conductivity [

14,

17,

19,

22,

25,

30].

Soil electrical conductivity (ECa) is a measurement that correlates with soil properties that affect crop productivity, including soil texture, cation exchange capacity (CEC), drainage conditions, organic matter level, salinity, soil characteristics the individual layers of the soil, the presence of nutrients, etc.

Current flow when determining ECa in soil passes through three media [

15,

20,

21,

24,

33,

34,

35,

36]:

liquid phase. It contains dissolved solids contained in the soil water. The liquid medium occupies the large pores;

solid-liquid phase. These are primarily through exchangeable cations associated with clay minerals;

solid soil particles that are in direct and continuous contact with each other.

ECa measurement is affected by several physical and chemical soil properties, such as soil salinity, cation saturation percentage, water content, and bulk density [

10,

25,

37].

Percent saturation and bulk density are directly affected by clay and organic matter (OM) content. Furthermore, the exchange surfaces on clays and OM provide the solid-liquid phase environment primarily through exchangeable cations. Therefore, clay content and type, cation exchange capacity (CEC) and OM are recognized as additional factors affecting ECa measurements. ECa measurements should be interpreted with these influencing factors in mind.

Another factor affecting ECa is temperature. Conductivity increases by approximately 1.9% per 1◦C increase in temperature. It is usually expressed at a reference temperature of 25 °C, [

11,

38].

Studies show that the optimal values of ECa for fertile soils should be in the range of 110 - 570 mS/m [

13,

40]. ECa is usually expressed in units of milliSiemens per meter (mS/m), but can also be expressed in units of deciSiemens per meter (dS/m), which is equal to the reading in mS/m divided by 100.

High values of ECa indicate the presence of negatively charged particles (from clay and organic matter) and therefore the presence of more cations (NH4+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, H+, Fe2+, etc.) that are positively charged and retained in the soil, thereby helping the growth and development of plants.

Soil EC is influenced by a number of its properties. In order to use it as an indicator of soil health and therefore inform the farmer about the actions he needs to take, the interrelationship between ECa and other soil properties must be understood.

A field in which ECa is distributed according to a normal law, whose scattering parameter has small values, is considered homogeneous [

4,

5].

ECa was originally used in agriculture to determine salinity in soils [

18]. Very high ECa values (>1600mS/m) are a sign of significant salinization, and very low ECa values (0-200mS/m) indicate that the soils are not salinized. Sodium cations have the greatest effect on salinization, especially if they exceed 100 mg⁄kg of soil.

Soil texture (sand, clay and silt), salinity, moisture and density are the properties that most influence ECa [

18].

Although soil texture cannot be changed by tillage, it is important to note how it interacts with ECa [

14,

15,

19]. Sand has a low ECa (1-10mS/m), silt have medium values (8-80mS/m), and clay has a high ECa (20-800mS/m). This means that sandy soils have poor capacity to hold cations and lose nutrients easily compared to clay and silt soils. Clay and silty soils have much greater capacity to retain cations and the loss of nutrients will be much less compared to sandy soils. Understanding this interaction, it can be recognized that for any field with a specific texture, at higher values of ECa, lower values of mineral fertilization should be applied, as a small part of what is applied will be lost by washing into the soil. - the lower soil layers. The addition of organic matter to sandy soils can lead to an improvement in their ability to hold cations and thus improve the ECa level.

Another indicator determining the physical properties of the soil is its density. All-season use of heavy and energy-intensive machines, annual plowing of soils at the same depth, as well as other types of treatments at high humidity, worsen their physical properties. Studies [

12] show that when EC values decrease, soil density increases.

The level of soil moisture has a determining role in the uptake of biogenic elements. Only the water-soluble forms of these elements can be absorbed by plants. In case of shortage, biogenic elements can be applied as fertilizers, but again the extent of their absorption is directly dependent on the presence of water in the soil layer inhabited by the roots. When ECa is measured in the field, the higher the ECa, the more moisture is in the soil. The explanation lies in the majority of cations in the soil solution. In general, water is a good conductor of electricity, and therefore the more water there is in the soil, the better the soil conducts electrical impulses.

The content and ratio of biogenic elements in the soil are directly related to soil fertility and plant nutrition. Except for the mineral fraction, organic compounds are composed of different ratios of carbon and nitrogen. An assessment of soil reserves is made on a 5-point scale according to the content of organic carbon (C), total nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and the ratio between organic carbon and total nitrogen in soils (C/N), which is regulated in Ordinance No. 4 on soil monitoring [

29] (

Table 1).

A positive correlation was observed between soil organic carbon and its ECa. The same relationship was observed between soil nitrogen and ECa [

12].

The three main groups of indicators determining the health status of the soil are manifested in complex interrelationships and each of them affects the properties of the others [

10,

11,

31]. Such complex interrelationships can hardly be described by traditional functional dependencies.

By measuring the ECa, the information contained in the soil about its main characteristics is recorded as a numerical series that provides an opportunity to describe the complex interrelationships. In the DSC method, non-contact measurement of ECa is used, based on the principle of electromagnetic induction. Soil EC screening is performed for 100% of the surveyed field area, with the location of each record being marked with geographic coordinates.

Stage 2. Building the soil sampling - the collected data on ECa of the soil in the surveyed field are subjected to statistical processing. The aim is to identify areas of the field in which the ECa can be assumed to be the same from a statistical point of view. In general, zones with strong, medium and weak electrical conductivity of the soil are formed, but in detail the number of zones depends on the observed soil diversity in the field. Statistical processing consists of determining the estimates of numerical characteristics and testing statistical hypotheses. The information from the received assessments is used to find the so-called the maximum relative error, which is accepted in the DSC method, should not exceed 10%. Such an error value determines the number of soil samples that must be taken from an area in order to guarantee the results obtained at a 95% confidence level. By performing a statistical hypothesis test for equality of a row of means is found at what number of zones on the field, it will be rejected. Thus, zones will be formed on the field, which will be significantly different from each other by the measured ECa of the soil in them. The outlines of each of the zones are determined by the GPS coordinates of the individual records during the scan. The field locations where soil samples will be taken are also set with their GPS coordinates, their location being adjusted to avoid autocorrelation with respect to ECa.

Stage 3. Soil sampling - it is carried out manually or mechanized using special tools that extract samples from four soil layers with a depth of 0-0.1m; 0.1-0.4m; 0.4-0.7m and 0.7-1.0m, according to the purpose of the surveyed field and the goals of the analysis. Each soil sample is marked with its GPS coordinates and recorded ECa value.

Stage 4. Laboratory analyses - the soil samples collected from the field are subjected to laboratory tests according to established procedures and standards [

9]. The obtained results of the laboratory analyses are used in the next stage to compile mathematical models.

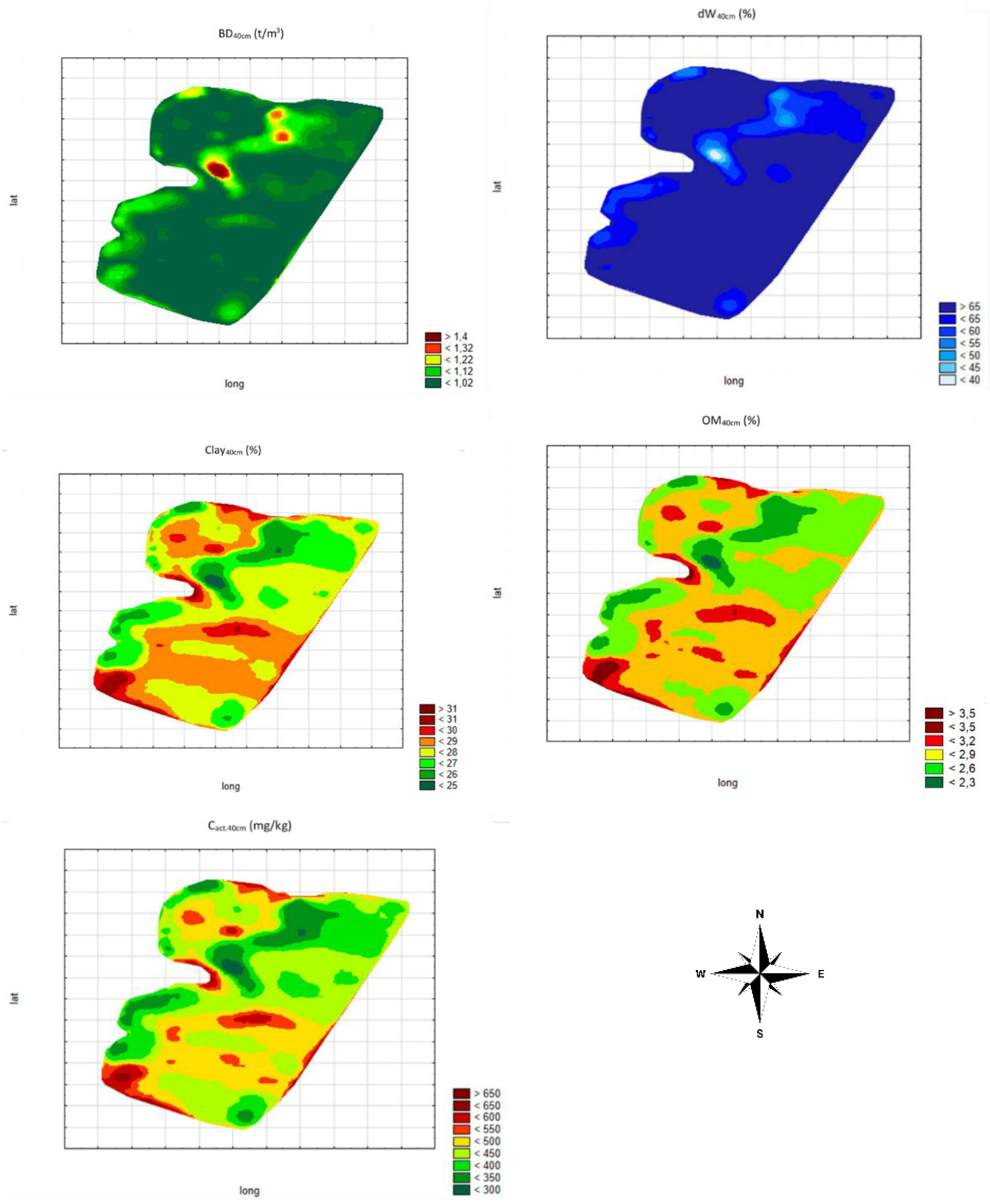

Stage 5. Creating digital soil models - a digital soil model is a collection of separate regression models expressing the relationship between a given soil parameter and the measured soil ECa. To obtain a specific regression model, the ECa data at the drilling (sampling) site and the results obtained from the laboratory analysis for the selected soil indicator are used. With these data, a regression analysis is carried out to quantitatively describe the relationship between the soil index and ECa.

The statistical analysis of the obtained regression models shows that the change of the soil index can be described by ECa and the obtained regression model. Another aspect of the statistical analysis is determining the adequacy of the model, which in the case of individual digital models is confirmed by Fisher’s criterion [

2,

4,

5,

6,

7]. This gives reason to assume that the error of the model does not exceed the error of the experimental data. By including a given regression model to the coordinates of the field, georeferenced data is obtained, with which the values of the observed soil indicator in the given field can be presented visually (through spectral maps) or digitally. The digital soil model created by the DSC method is specific to the surveyed field, but has the potential for universality.

Another proven possibility of the DPC method is to perform a soil health check. A differential method is applied, in which the so-called desirability function (Harrington function) [

6]. One of the functions is formed on the basis of digital models obtained from the DSC, and the other on the basis of soil reference data [

3], to which the surveyed soil can be referred. When the difference between the two desirability functions tends to zero, it can be considered that the soil in the observed field is healthy, i.e., tends to its natural state.

1.3. Application of the DSC Method

The digital nature of the DSC method allows it to be integrated with other modern digital technologies. Such digital technology is a system that offers innovative services and solutions for agriculture. The platform of the SCANFIELD-5S system is built on five main pillars of a digital nature: 3D scanner; Data processing; soil maps; analyzes and decisions.

3D scanner – a patented scanner is used for non-contact measurement of soil electrical conductivity [

28]. Raw data from the ECa scanner is converted into information on several baseline metrics: soil zones, depth to compaction, relative soil moisture and tillage maps. The scanner mounts directly on a vehicle, which can be a tractor, ATV, pickup truck, or similar field vehicle. The sensor can be used on any soil, even when it is covered with vegetation. There is also no restriction on minimum or maximum soil moisture content.

The scanner works on the principle of electromagnetic induction. A magnetic field is induced through a transmission coil (

Figure 3). Four receiving coils then measure electrical conductivity at four cumulative depths, up to 1.0m. The device also permanently records spatial information. No ground contact is required to obtain soil electrical conductivity data. The data is collected and can be processed in real time to be immediately used on the tractor (for example for managing agricultural equipment).

Data processing - raw, raw data is processed with filters and sophisticated algorithms to produce a series of files. Some of these files can be used directly from the agricultural machine’s ISOBUS terminal for further use. With the filtered data, spectral maps of the observed indicators are prepared. From the spectral map for the soil zones, the locations of the soil sampling sites are determined.

Analyzes – physical soil samples are sent to a soil analysis laboratory. The obtained results are processed and analyzed using specialized software and the DSC method, after which the data are transformed into soil maps.

The soil maps are spectral maps for each soil parameter for which a digital model was obtained using the DSC method. Each map is made by specialized software. The data from the maps can also be transformed into a tabular form. The detail in the soil map can be changed according to the needs of the user. The prepared soil map is complemented by a legend explaining the obtained results.

Solutions – the SCANFIELD-5S system provides farmers with sound solutions tailored to their needs and applicable in modern technologies. One such solution is the creation of a variable rate card (VRA). Such a map can be used for sowing, fertilizing with liquid or solid fertilizers, watering and other agricultural operations for which it is advisable to perform them at a high level of precision. Another potential possibility is the issuance of carbon certificates, which would allow farmers to declare the accumulated amount of carbon in their fields. In addition to the direct benefits of carbon certificates, farmers will have information on how much their agricultural practices contribute to improving soil health.