Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

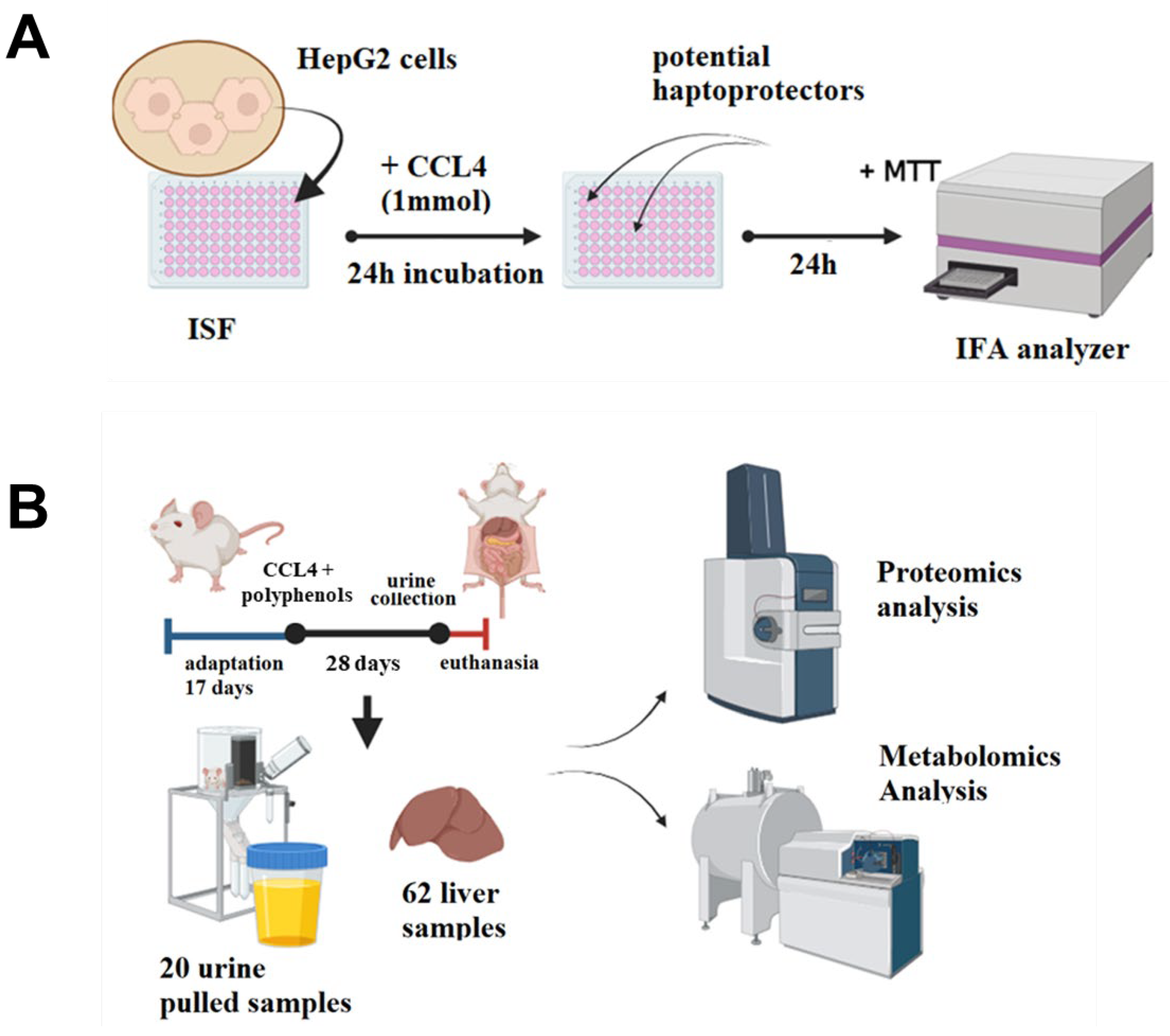

2.1. Overview of the Study Pipeline

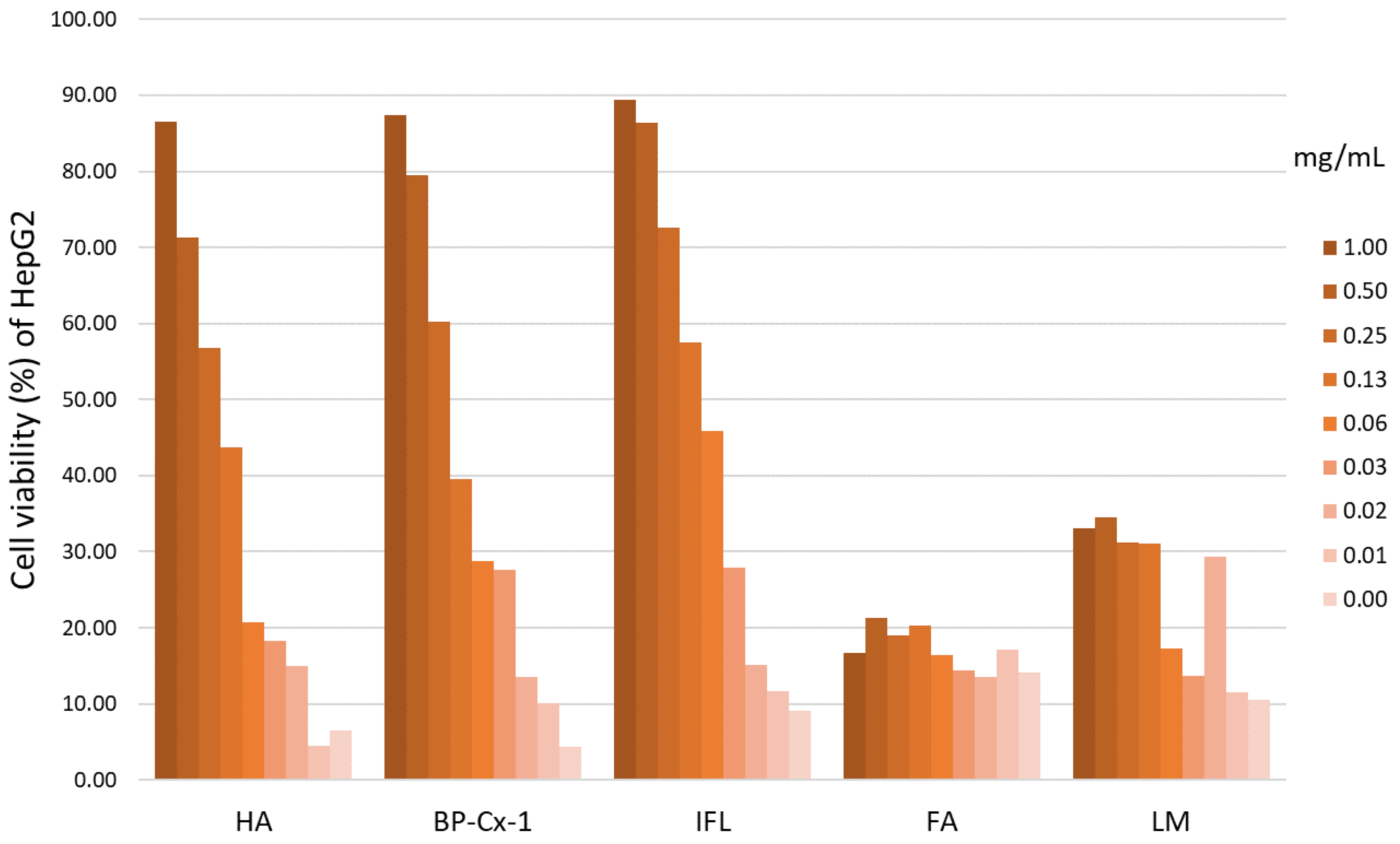

2.2. Determination of the Hepatoprotective Effect In Vitro

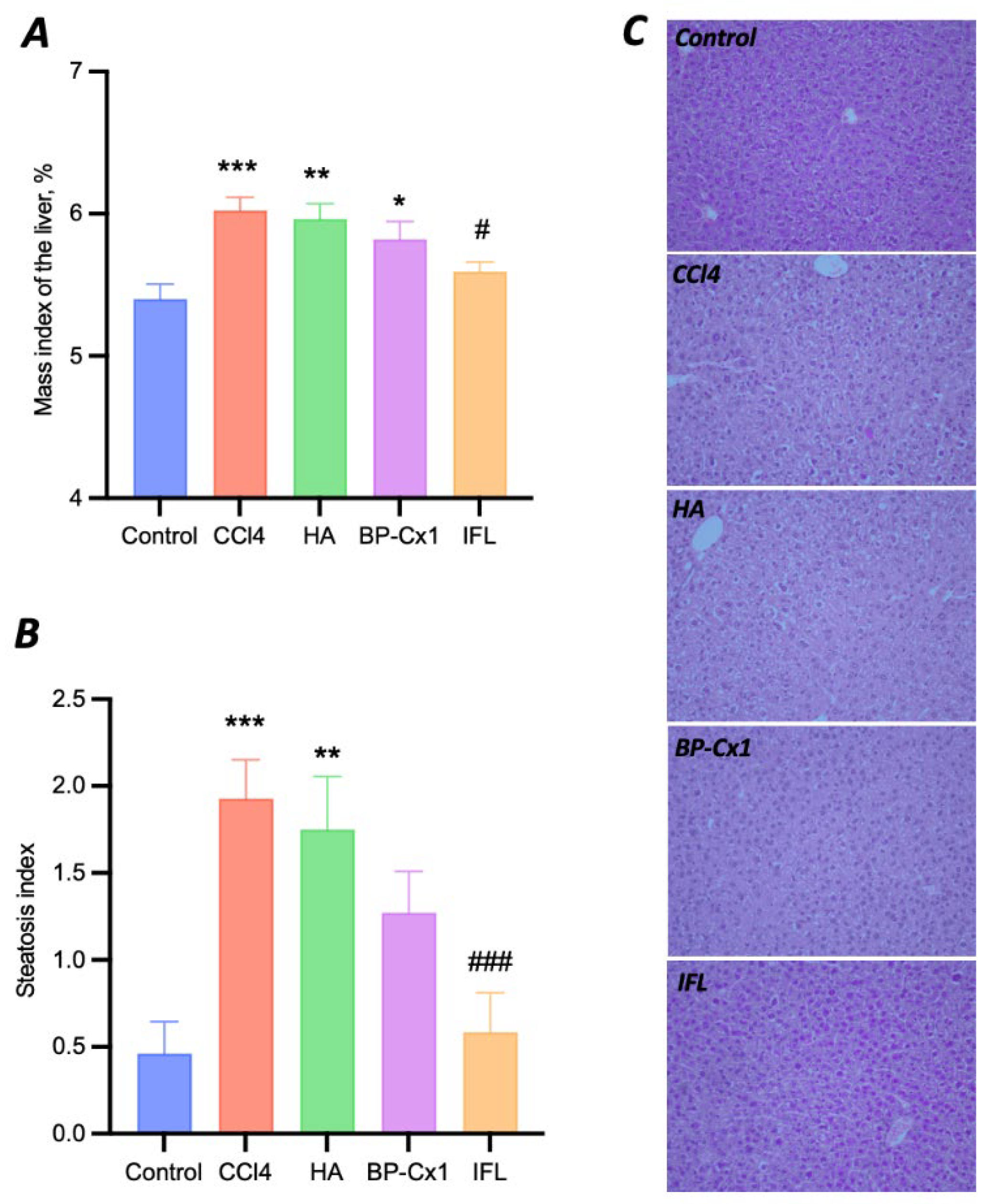

2.3. Determination of the Hepatoprotective Effect In Vivo

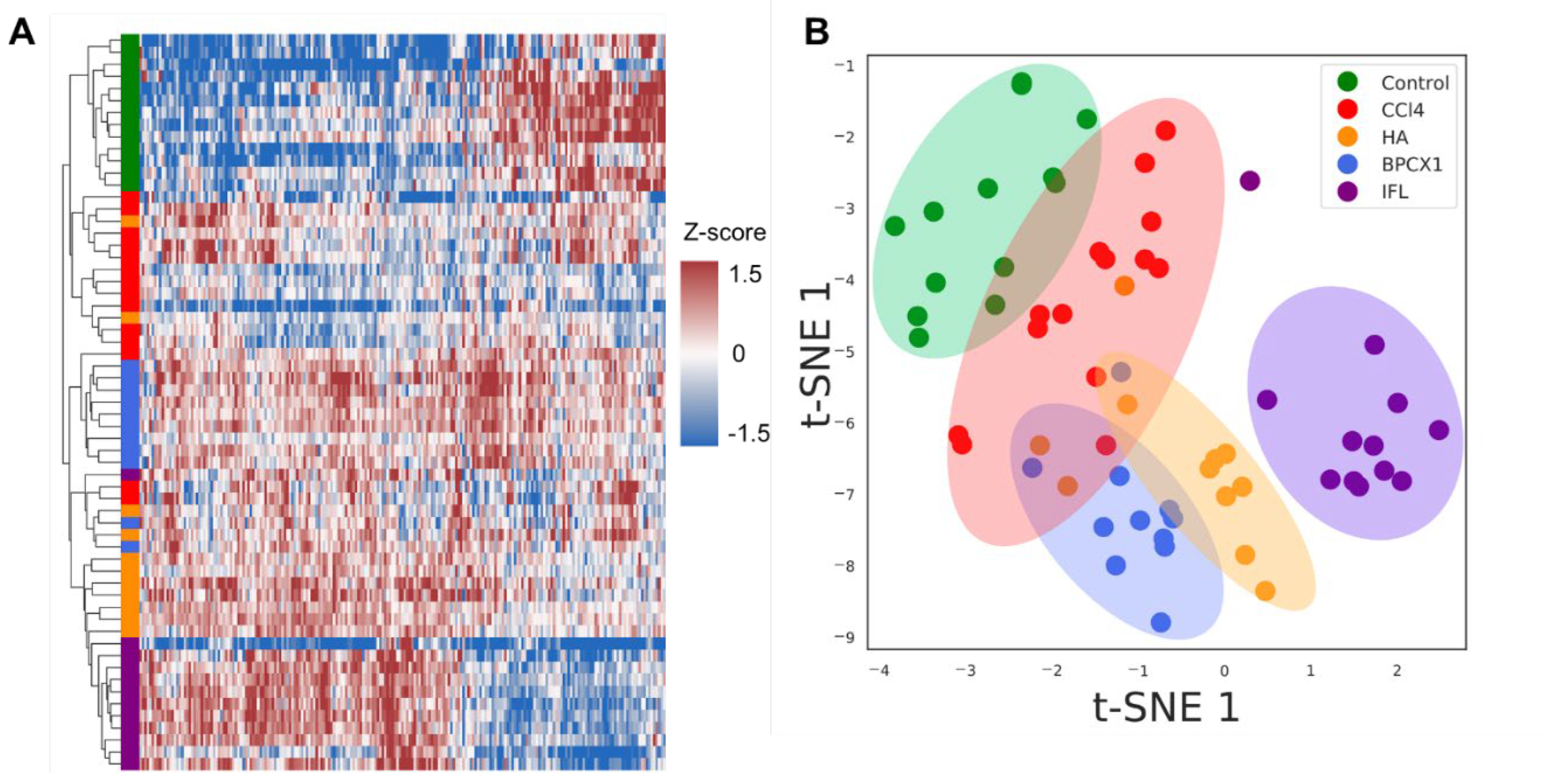

2.4. Proteomic Analysis

Urine proteome Fraction Analysis

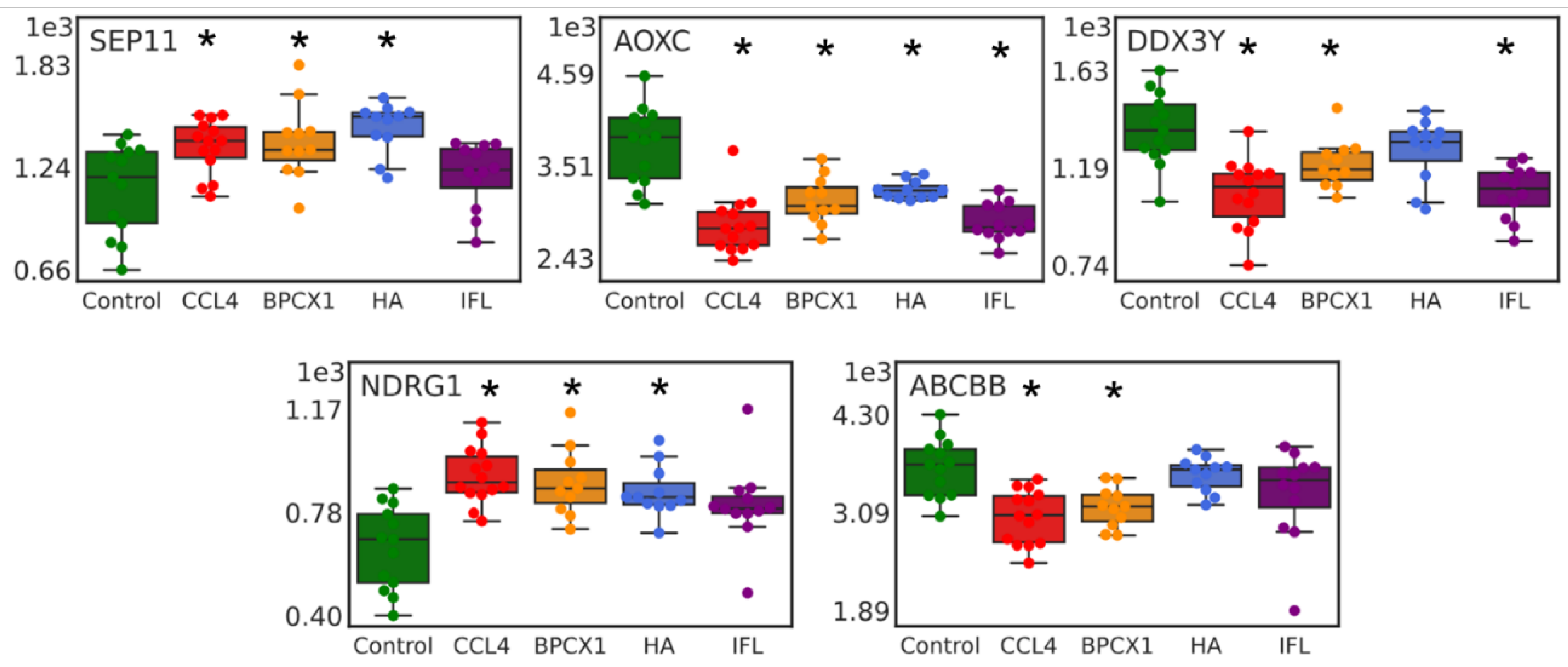

Liver Proteome Fraction Analysis

2.5. Metabolomic Analysis

3. DISCUSSION

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Animal Studies

Experimental Design

- Control – negative control – intraperitoneal injection of sunflower oil (0.2 ml/mouse) (n=13);

- Control CCl4 – positive control – intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 (1 ml/kg) diluted ten times in sunflower oil 2 times per week (6 injections in total) (n=14);

- CCl4 + Fraction of humic acids from low-mineralized silt sulfide mud (peloids) of lake Molochka (MRC “Sergievskie Mineral Waters” FMBA of Russia) (HA) –intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 (1 ml/kg) diluted ten times in sunflower oil 2 times per week (6 injections in total) + intragastric administration of HA (60 mg/kg) 3 times a week, for 4 weeks (n=12);

- CCl4 + BP-Cx-1 –intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 (1 ml/kg) diluted ten times in sunflower oil 2 times per week (6 injections in total) + intragastric administration of BP-Cx-1 (60 mg/kg) 3 times a week, for 4 weeks (n=11);

- CCl4 + isoflavones isolated from the root of Pueralia lobata (IFL) –intraperitoneal injection of CCl4 (1 ml/kg) diluted ten times in sunflower oil 2 times per week (6 injections in total) + intragastric administration of IFL (60 mg/kg) 3 times a week, for 4 weeks (n=12).

3.3. MTT Colorimetric Assay

3.4. Proteomic Analysis

Urine Samples Preparation

Liver Samples Preparation

LC-MS/MS Analysis

Data Analysis

3.5. Metabolomic Analysis

Extraction of Metabolites

FTICR MS Analysis

Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slamenová, D.; Kosíková, B.; Lábaj, J.; Ruzeková, L. Oxidative/Antioxidative Effects of Different Lignin Preparations on DNA in Hamster V79 Cells. Neoplasma 2000, 47, 349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Yagi, T.; Shinohara, S.; Fukunaga, T.; Nakasaka, Y.; Tago, T.; Masuda, T. Production of Phenols from Lignin via Depolymerization and Catalytic Cracking. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 108, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoros, E.I.; Orlov, A.A.; Zherebker, A.; Gubareva, E.A.; Maydin, M.A.; Konstantinov, A.I.; Krasnov, K.A.; Karapetian, R.N.; Izotova, E.I.; Pigarev, S.E.; et al. Novel Water-Soluble Lignin Derivative BP-Cx-1: Identification of Components and Screening of Potential Targets in Silico and in Vitro. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 18578–18593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, A.; Mosca, L.; Puca, R.; Mangino, G.; Rossi, A.; Lendaro, E. Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Phenols Block Cell Cycle Progression and Modulate Chemotherapeutic Toxicity in Bladder Cancer Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 3095–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impellizzeri, J.; Lin, J. A Simple High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method for the Determination of Throat-Burning Oleocanthal with Probated Antiinflammatory Activity in Extra Virgin Olive Oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3204–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza-Acosta, J.L.; Torres-Chávez, P.I.; Ramírez-Wong, B.; López-Saiz, C.M.; Montaño-Leyva, B. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Antimutagenic Properties of Technical Lignins and Their Applications. BioResources 2016, 11, 5452–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lábaj, J.; Slamenová, D.; Kosikova, B. Reduction of Genotoxic Effects of the Carcinogen N-Methyl-N’-Nitro-N-Nitrosoguanidine by Dietary Lignin in Mammalian Cells Cultured in Vitro. Nutr. Cancer 2003, 47, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barapatre, A.; Meena, A.S.; Mekala, S.; Das, A.; Jha, H. In Vitro Evaluation of Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities of Lignin Fractions Extracted from Acacia Nilotica. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Mukai, Y.; Tokuoka, Y.; Mikame, K.; Funaoka, M.; Fujita, S. Effect of Lignin-Derived Lignophenols on Hepatic Lipid Metabolism in Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 34, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, G.; Lisco, A.; Vanpouille, C.; Introini, A.; Balestra, E.; van den Oord, J.; Cihlar, T.; Perno, C.-F.; Snoeck, R.; Margolis, L.; et al. Topical Tenofovir, a Microbicide Effective against HIV, Inhibits Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Replication. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saluja, B.; Thakkar, J.N.; Li, H.; Desai, U.R.; Sakagami, M. Novel Low Molecular Weight Lignins as Potential Anti-Emphysema Agents: In Vitro Triple Inhibitory Activity against Elastase, Oxidation and Inflammation. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 26, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinardell, M.P.; Mitjans, M. Lignins and Their Derivatives with Beneficial Effects on Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zherebker, A.Y.; Rukhovich, G.D.; Kharybin, O.N.; Fedoros, E.I.; Perminova, I. V; Nikolaev, E.N. Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry for the Analysis of Molecular Composition and Batch-to-Batch Consistency of Plant-Derived Polyphenolic Ligands Developed for Biomedical Application. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 34, e8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björklund, L.; Larsson, S.; Jönsson, L.J.; Reimann, E.; Nilvebrant, N.-O. Treatment with Lignin Residue: A Novel Method for Detoxification of Lignocellulose Hydrolysates. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2002, 98–100, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengerovskiĭ, A.I.; Golovina, E.L.; Burkova, V.N.; Saratikov, A.S. Enteric sorbents potentiate hepatoprotective effect of eplir in experimental toxic hepatitis. Eksp. Klin. Farmakol. 2001, 64, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nebbioso, A.; Piccolo, A. Basis of a Humeomics Science: Chemical Fractionation and Molecular Characterization of Humic Biosuprastructures. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhernov, Y. V; Konstantinov, A.I.; Zherebker, A.; Nikolaev, E.; Orlov, A.; Savinykh, M.I.; Kornilaeva, G. V; Karamov, E. V; Perminova, I. V Antiviral Activity of Natural Humic Substances and Shilajit Materials against HIV-1: Relation to Structure. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, N.; Wang, T.; Gan, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant Flavonoids: Classification, Distribution, Biosynthesis, and Antioxidant Activity. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas, M.E.; Peltier-Heap, R.E.; Leveridge, M.; Annan, R.S.; Büttner, F.H.; Trost, M. Advances in High-Throughput Mass Spectrometry in Drug Discovery. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e14850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlov, A.; Semenov, S.; Rukhovich, G.; Sarycheva, A.; Kovaleva, O.; Semenov, A.; Ermakova, E.; Gubareva, E.; Bugrova, A.E.; Kononikhin, A.; et al. Hepatoprotective Activity of Lignin-Derived Polyphenols Dereplicated Using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry, In Vivo Experiments, and Deep Learning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, M.; Cross, T.J.S. Amyloidosis and Subacute Liver Failure. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (N. Y). 2012, 8, 208–211. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, J.G. Acute Liver Failure. Postgrad. Med. J. 2005, 81, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, B.N.; Joshi, Y.K.; Krishnamurthy, L.; Tandon, H.D. Subacute Hepatic Failure; Is It a Distinct Entity? J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1982, 4, 343-346,362-364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.M.; Shrestha, S. Subacute Hepatic Failure : Its Possible Pathogenesis. 2012, 2, 41–46.

- Scholten, D.; Trebicka, J.; Liedtke, C.; Weiskirchen, R. The Carbon Tetrachloride Model in Mice. Lab. Anim. 2015, 49, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mering, C. von; Huynen, M.; Jaeggi, D.; Schmidt, S.; Bork, P.; Snel, B. STRING: A Database of Predicted Functional Associations between Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkar, S.; Weber, G.F.; Panoutsakopoulou, V.; Sanchirico, M.E.; Jansson, M.; Zawaideh, S.; Rittling, S.R.; Denhardt, D.T.; Glimcher, M.J.; Cantor, H. Eta-1 (Osteopontin): An Early Component of Type-1 (Cell-Mediated) Immunity. Science 2000, 287, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchigna, S.; Oh, H.; Wilsch-Bräuninger, M.; Missol-Kolka, E.; Jászai, J.; Jansen, S.; Tanimoto, N.; Tonagel, F.; Seeliger, M.; Huttner, W.B.; et al. Loss of the Cholesterol-Binding Protein Prominin-1/CD133 Causes Disk Dysmorphogenesis and Photoreceptor Degeneration. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 2297–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, N.; Schäffer, A.A.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Elliott, G.; Garrett, L.; Choi, N.T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Mutations in COMP Cause Familial Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeAngelis, A.M.; Heinrich, G.; Dai, T.; Bowman, T.A.; Patel, P.R.; Lee, S.J.; Hong, E.-G.; Jung, D.Y.; Assmann, A.; Kulkarni, R.N.; et al. Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 1: A Link between Insulin and Lipid Metabolism. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2296–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosomi, S.; Chen, Z.; Baker, K.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.-H.; Olszak, T.; Zeissig, S.; Wang, J.H.; Mandelboim, O.; Beauchemin, N.; et al. CEACAM1 on Activated NK Cells Inhibits NKG2D-Mediated Cytolytic Function and Signaling. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 2473–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Pan, H.; Shively, J.E. CEACAM1 Negatively Regulates IL-1β Production in LPS Activated Neutrophils by Recruiting SHP-1 to a SYK-TLR4-CEACAM1 Complex. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrichs, B.; Tepel, C.; Reinheckel, T.; Deussing, J.; von Figura, K.; Herzog, V.; Peters, C.; Saftig, P.; Brix, K. Thyroid Functions of Mouse Cathepsins B, K, and L. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 111, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, M.A.; Ribeiro, A.L.C.; Costa, B.R.C.; Vago, J.P.; Lima, K.M.; Carneiro, F.S.; Ortiz, M.M.O.; Lima, G.L.N.; Carmo, A.A.F.; Rocha, R.M.; et al. Plasmin and Plasminogen Induce Macrophage Reprogramming and Regulate Key Steps of Inflammation Resolution via Annexin A1. Blood 2017, 129, 2896–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croessmann, S.; Wong, H.Y.; Zabransky, D.J.; Chu, D.; Mendonca, J.; Sharma, A.; Mohseni, M.; Rosen, D.M.; Scharpf, R.B.; Cidado, J.; et al. NDRG1 Links P53 with Proliferation-Mediated Centrosome Homeostasis and Genome Stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 11583–11588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Xu, L.; Chu, H.; Peng, J.; Sacharidou, A.; Hsieh, H.-H.; Weinstock, A.; Khan, S.; Ma, L.; Durán, J.G.B.; et al. Macrophage-to-Endothelial Cell Crosstalk by the Cholesterol Metabolite 27HC Promotes Atherosclerosis in Male Mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Zong, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Ji, G. Resveratrol Alleviates FFA and CCl4 Induced Apoptosis in HepG2 Cells via Restoring Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 43799–43809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical Data Visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. Proc. 9th Python Sci. Conf. 2010, 1, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. 2018.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. ofMachine Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, C.E.; Lento, H.G. Chloroform-Methanol Extraction Method for Determination of Fat in Foods: Collaborative Study. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1983, 66, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessner, D.; Chambers, M.; Burke, R.; Agus, D.; Mallick, P. ProteoWizard: Open Source Software for Rapid Proteomics Tools Development. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2534–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goloborodko, A.A.; Levitsky, L.I.; Ivanov, M. V; Gorshkov, M. V Pyteomics--a Python Framework for Exploratory Data Analysis and Rapid Software Prototyping in Proteomics. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 24, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volikov, A.; Rukhovich, G.; Perminova, I. V NOMspectra: An Open-Source Python Package for Processing High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Data on Natural Organic Matter. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 34, 1524–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, A.T.; Kourtchev, I.; Bortolini, C.; Fuller, S.J.; Giorio, C.; Popoola, O.A.M.; Bogialli, S.; Tapparo, A.; Jones, R.L.; Kalberer, M. A New Processing Scheme for Ultra-High Resolution Direct Infusion Mass Spectrometry Data. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 178, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhinov, A.N.; Zhurov, K.O.; Tsybin, Y.O. Iterative Method for Mass Spectra Recalibration via Empirical Estimation of the Mass Calibration Function for Fourier Transform Mass Spectrometry-Based Petroleomics. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 6437–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).