Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

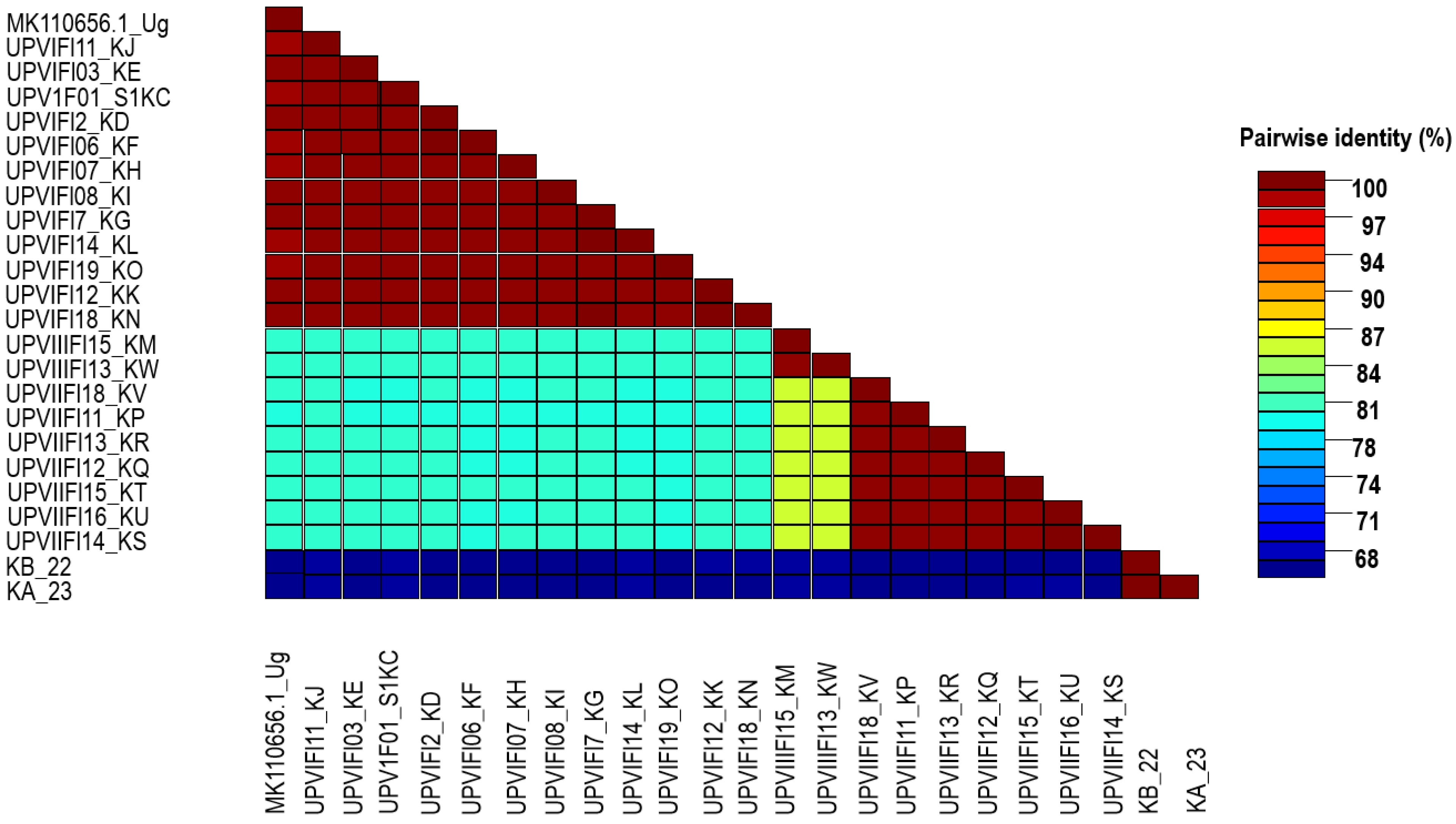

Passion fruit virus diseases (PWDs) pose a significant threat to Kenya's passion fruit industry. To unravel the complexity of these diseases, comprehensive virus surveys were conducted across major passion fruit-growing counties. PWD symptoms like fruit hardening, chlorotic mottling, and leaf distortion, were prevalent. The study unveiled the first 23 complete genomes of Ugandan Passiflora virus (UPV) and two East Asian Passiflora distortion virus (EAPDV) in Kenya. UPV showed 99% nucleotide (nt) match to a UPV genome from Uganda and 66% nt identity match to EAPDV. Phylogenetic analysis revealed distinct lineages (I-III), indicating potential multiple introductions into Kenya. Recombination analysis detected no significant breakpoints. However, the study proposed the renaming of EAPDV to passiflora distortion virus (PDV) and UPV to passiflora virus (PV) for neutral nomenclature. Additionally, the study highlighted the role of coinfections in symptom expression, suggesting a synergistic relationship between UPV, EAPDV (PDV), and other viruses. The results recommend for stringent management strategies and enhanced surveillance to mitigate the economic impact of these viruses to Kenyan passion fruit industry. Overall, the study highlights, need to strengthen phytosanitary measures and border surveillance to safeguard Kenya's agriculture from the threat of emerging plant viral diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

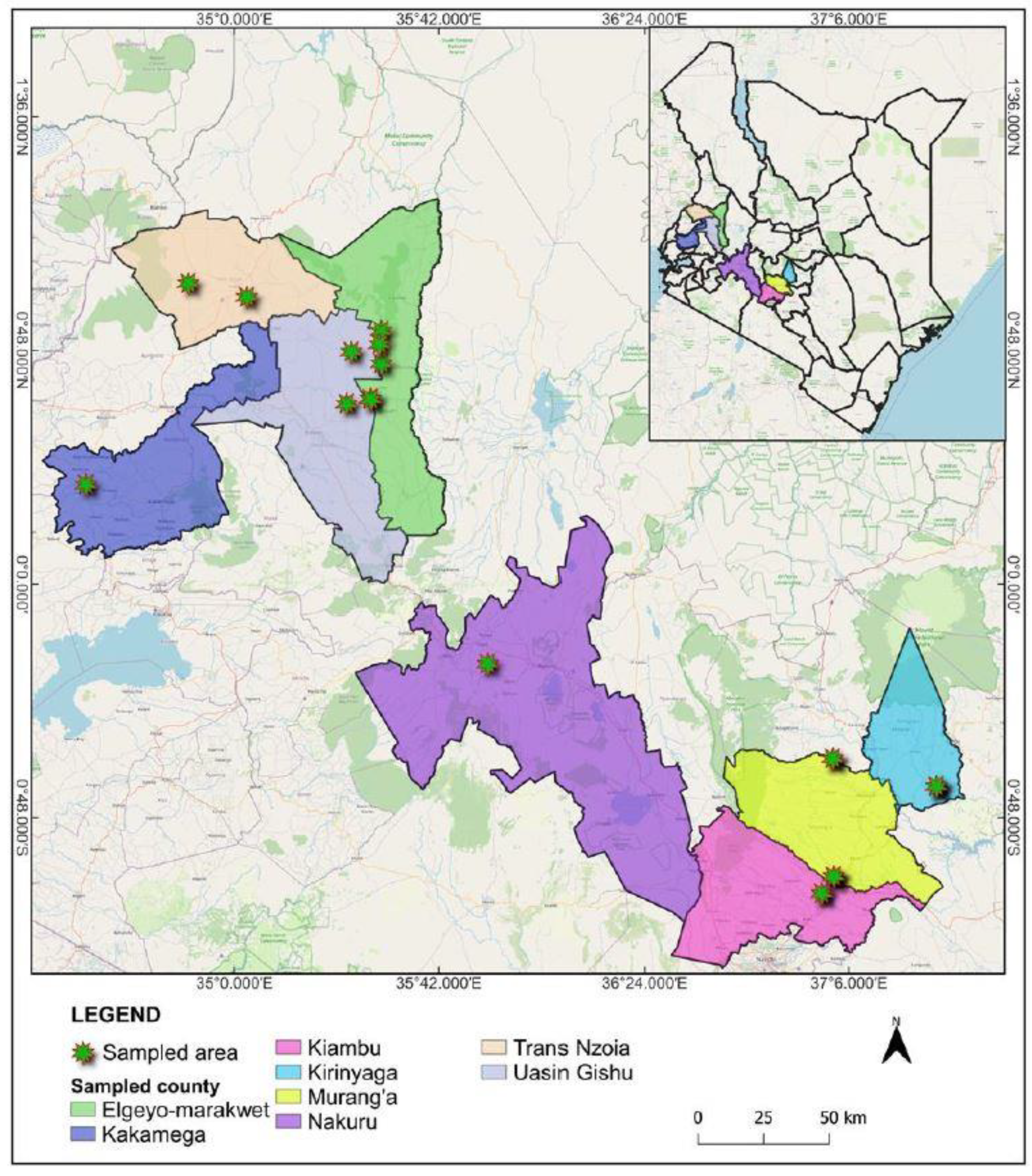

2.1. Collection of Passion Fruit Leaf Samples

2.2. RNA Extraction

2.3. High Throughput Sequencing

2.4. Sequence Analysis

2.5. Phylogenetic and Recombination Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Virus Identification

3.2. Phylogenetic and Recombination Analysis

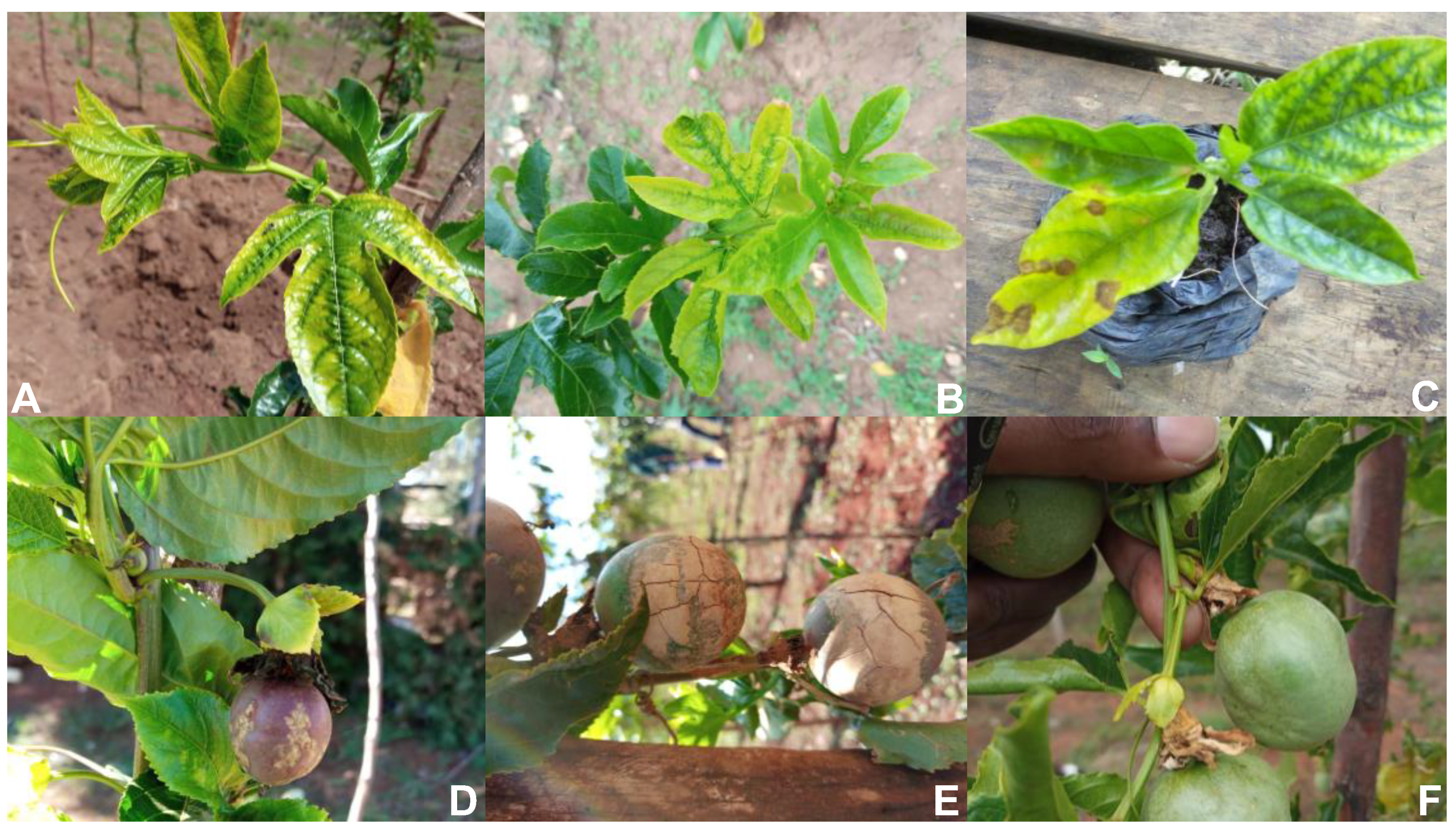

3.3. Symptoms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cervi, A.C.I. , Daniela Cristina. A new species of Passiflora (Passifloraceae) from Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Phytotaxa 2013, 103, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicom, B.; Ruggiero, C.; Ploetz, R.C.; Goes, A.d. Diseases of passion fruit. Diseases of tropical fruit crops 2003, 413–441. [Google Scholar]

- Devi Ramaiya, S.; Bujang, J.S.; Zakaria, M.H.; King, W.S.; Shaffiq Sahrir, M.A. Sugars, ascorbic acid, total phenolic content and total antioxidant activity in passion fruit (Passiflora) cultivars. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2013, 93, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phamiwon Zas, P.Z.; John, S. Diabetes and medicinal benefits of Passiflora edulis. 2016.

- Castillo, N.R.; Ambachew, D.; Melgarejo, L.M.; Blair, M.W. Morphological and agronomic variability among cultivars, landraces, and genebank accessions of purple passion fruit, Passiflora edulis f. edulis. HortScience 2020, 55, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Mishra, P. Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims.)—An underexploited plant of nutraceutical value. Asian Journal of Medical and Health Research 2016, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ochwo-Ssemakula, M.; Sengooba, T.; Hakiza, J.; Adipala, E.; Edema, R.; Redinbaugh, M.; Aritua, V.; Winter, S. Characterization and distribution of a Potyvirus associated with passion fruit woodiness disease in Uganda. Plant Disease 2012, 96, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFA. AFA YEAR BOOK OF STATISTICS. 2022.

- Karani-Gichimu, C.; Mwangi, M.; Macharia, I. Assessment of passion fruit orchard management and farmers’ technical efficiency in Central-Eastern and North-Rift Highlands Kenya. Assessment 2013, 4, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Amata, R.; Otipa, M.; Waiganjo, M.; Wasilwa, L.; Kinoti, J.; Kyamanywa, S.; Erbaugh, M. Management strategies for fungal diseases in passion fruit production systems in Kenya. In Proceedings of the I All Africa Horticultural Congress 911; 2009; pp. 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gesimba, R.M. Screening Passiflora species for drought tolerance, compatibility with purple passion fruit, Fusarium wilt resistance and the relationship between irrigation, drenching and media composition in the control of Fusarium wilt. The Ohio State University, 2008.

- Amata, R.; Otipa, M.; Waiganjo, M.; Wabule, M.; Thuranira, E.; Erbaugh, M.; Miller, S. Incidence, prevalence and severity of passion fruit fungal diseases in major production regions of Kenya. 2009.

- Wangungu, C.; Mwangi, M.; Gathu, R.; Muasya, R.; Mbaka, J.; Kori, N. Reducing dieback disease incidence of passion fruit in Kenya through management practices. 2011.

- HCDA. NATIONAL HORTICULTURE VALIDATED REPORT. 2013.

- Morton, J. Jackfruit. Fruits of warm climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, FL, 1987; 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, C.A.; Jeyaprakash, A.; Webster, C.G.; Adkins, S. Viruses infecting passiflora species in Florida; Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Tallahassee, FL, USA: 2014.

- Coutts, B.A.; Kehoe, M.A.; Webster, C.G.; Wylie, S.J.; Jones, R.A. Indigenous and introduced potyviruses of legumes and Passiflora spp. from Australia: Biological properties and comparison of coat protein nucleotide sequences. Archives of Virology 2011, 156, 1757–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenele, R.S.; Abreu, R.A.; Lamas, N.S.; Alves-Freitas, D.M.; Vidal, A.H.; Poppiel, R.R.; Melo, F.L.; Lacorte, C.; Martin, D.P.; Campos, M.A. Passion fruit chlorotic mottle virus: Molecular characterization of a new divergent geminivirus in Brazil. Viruses 2018, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, T.; Nakamura, M.; Rikitake, M.; Iwai, H. Molecular characterization and specific detection of two genetically distinguishable strains of East Asian Passiflora virus (EAPV) and their distribution in southern Japan. Virus Genes 2012, 44, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbeyagala, E.; Maina, S.; Macharia, M.; Mukasa, S.; Holton, T. Illumina sequencing reveals the first near-complete genome sequence of Ugandan Passiflora virus. Microbiology Resource Announcements 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munguti, F.; Maina, S.; Nyaboga, E.; Kilalo, D.; Kimani, E.; Macharia, M.; Holton, T. Transcriptome sequencing reveals a complete genome sequence of Cowpea aphid-borne mosaic virus from passion fruit in Kenya. Microbiology Resource Announcements 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, A.V.S.d.; Santana, E.N.d.; Braz, A.S.K.; Alfenas, P.; Pio-Ribeiro, G.; Andrade, G.P.d.; De Carvalho, M.; Murilo Zerbini, F. Cowpea aphid-borne mosaic virus (CABMV) is widespread in passionfruit in Brazil and causes passionfruit woodiness disease. Archives of virology 2006, 151, 1797–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrella, G.; Lanave, C. Identification of a new pathotype of Bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV) infecting blue passion flower and some evolutionary characteristics of BYMV. Archives of virology 2009, 154, 1689–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polston, J.; Londoño, M.; Cohen, A.; Padilla-Rodriguez, M.; Rosario, K.; Breitbart, M. Genome sequence of Euphorbia mosaic virus from passionfruit and Euphorbia heterophylla in Florida. Genome announcements 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.S.; Ryu, K.H. The complete genome sequence and genome structure of passion fruit mosaic virus. Archives of virology 2011, 156, 1093–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S.; Zeidan, M.; Sobolev, I.; Beckelman, Y.; Holdengreber, V.; Tam, Y.; Bar Joseph, M.; Lipsker, Z.; Gera, A. The complete nucleotide sequence of Passiflora latent virus and its phylogenetic relationship to other carlaviruses. Archives of virology 2007, 152, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaca-Vaca, J.C.; Carrasco-Lozano, E.C.; López-López, K. Molecular identification of a new begomovirus infecting yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) in Colombia. Archives of Virology 2017, 162, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilalo, D.; Olubayo, F.; Ateka, E.; Hutchinson, J.; Kimenju, J. Monitoring of aphid fauna in passionfruit orchards in Kenya. 2013.

- Iwai, H.; Yamashita, Y.; Nishi, N.; Nakamura, M. The potyvirus associated with the dappled fruit of Passiflora edulis in Kagoshima prefecture, Japan is the third strain of the proposed new species East Asian Passiflora virus (EAPV) phylogenetically distinguished from strains of Passion fruit woodiness virus. Archives of Virology 2006, 151, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brand, R.; Burger, J.; Rybicki, E. Cloning, sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli of the coat protein gene of a new potyvirus infecting South African Passiflora. Archives of Virology 1993, 128, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKern, N.; Strike, P.; Barnett, O.; Dijkstra, J.; Shukla, D.; Ward, C. Cowpea aphid borne mosaic virus-Morocco and South African Passiflora virus are strains of the same potyvirus. Archives of Virology 1994, 136, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilalo, D. Molecular detection of viruses associated with passion fruit (Passiflora edulis sims) woodiness disease, monitoring and management of aphid vectors in Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi. Homepage address: Erepository …, 2012.

- Njuguna, J.; Ndungu, B.; Mbaka, J.; Chege, B. Report on passion fruit diagnostic survey. A Collaborative Research of KARI/MOA/GTZ under promotion of private sector development in Agriculture (PSDA) programme, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Asande, L.K.; Ombori, O.; Oduor, R.O.; Nchore, S.B.; Nyaboga, E.N. Occurrence of passion fruit woodiness disease in the coastal lowlands of Kenya and screening of passion fruit genotypes for resistance to passion fruit woodiness disease. BMC Plant Biology 2023, 23, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ma, F.; Zhang, X.; Tan, Y.; Han, T.; Ding, J.; Wu, J.; Xing, W.; Wu, B.; Huang, D. Research Progress on Viruses of Passiflora edulis. Biology 2024, 13, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuze, J.F.; Perez, A.; Untiveros, M.; Quispe, D.; Fuentes, S.; Barker, I.; Simon, R. Complete viral genome sequence and discovery of novel viruses by deep sequencing of small RNAs: A generic method for diagnosis, discovery and sequencing of viruses. Virology 2009, 388, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, S.; Barbetti, M.J.; Edwards, O.R.; Minemba, D.; Areke, M.W.; Jones, R.A. Genetic connectivity between papaya ringspot virus genomes from Papua New Guinea and Northern Australia, and new recombination insights. Plant disease 2019, 103, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.R.; Constable, F.; Tzanetakis, I.E. Quarantine regulations and the impact of modern detection methods. Annual review of phytopathology 2016, 54, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamor, D.; Ho, T.; Al Rwahnih, M.; Martin, R.; Tzanetakis, I. High throughput sequencing for plant virus detection and discovery. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, F. Trim galore. A wrapper tool around Cutadapt and FastQC to consistently apply quality and adapter trimming to FastQ files 2015, 516, 517. [Google Scholar]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome research 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maina, S.; Coutts, B.A.; Edwards, O.R.; de Almeida, L.; Kehoe, M.A.; Ximenes, A.; Jones, R.A. Zucchini yellow mosaic virus populations from East Timorese and Northern Australian cucurbit crops: Molecular properties, genetic connectivity, and biosecurity implications. Plant Disease 2017, 101, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maina, S.; Coutts, B.A.; Edwards, O.R.; de Almeida, L.; Ximenes, A.; Jones, R.A. Papaya ringspot virus populations from East Timorese and Northern Australian cucurbit crops: Biological and molecular properties, and absence of genetic connectivity. Plant disease 2017, 101, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maina, S.; Edwards, O.R.; de Almeida, L.; Ximenes, A.; Jones, R.A. Metagenomic analysis of cucumber RNA from East Timor reveals an Aphid lethal paralysis virus genome. Genome Announcements 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Chetvernin, V.; Tatusova, T. Improvements to pairwise sequence comparison (PASC): A genome-based web tool for virus classification. Archives of virology 2014, 159, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular biology and evolution 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus evolution 2015, 1, vev003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Varsani, A.; Roumagnac, P.; Botha, G.; Maslamoney, S.; Schwab, T.; Kelz, Z.; Kumar, V.; Murrell, B. RDP5: A computer program for analyzing recombination in, and removing signals of recombination from, nucleotide sequence datasets. Virus Evolution 2021, 7, veaa087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padidam, M.; Sawyer, S.; Fauquet, C.M. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology 1999, 265, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.P.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.; Williamson, C. A modified bootscan algorithm for automated identification of recombinant sequences and recombination breakpoints. Microbiology 2005, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.M. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. Journal of molecular evolution 1992, 34, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: Computer simulations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98, 13757–13762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.F.; Posada, D.; Feldman, M.W. An exact nonparametric method for inferring mosaic structure in sequence triplets. Genetics 2007, 176, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M.J.; Armstrong, J.S.; Gibbs, A.J. Sister-scanning: A Monte Carlo procedure for assessing signals in recombinant sequences. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hirota, R.; Hamamoto, T.; Tomimura, K.; Tan, Z.; Sano, T.; Azuhata, F.; Walsh, J.A.; Fletcher, J. Molecular evolution of Turnip mosaic virus: Evidence of host adaptation, genetic recombination and geographical spread. Journal of General Virology 2002, 83, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, S.; Donovan, N.J.; Plett, K.; Bogema, D.; Rodoni, B.C. High-throughput sequencing for plant virology diagnostics and its potential in plant health certification. Frontiers in Horticulture 2024, 3, 1388028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syller, J. Facilitative and antagonistic interactions between plant viruses in mixed infections. Molecular plant pathology 2012, 13, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Antoniw, J.; Fauquet, C. Molecular criteria for genus and species discrimination within the family Potyviridae. Archives of virology 2005, 150, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancy, W.W.; Dora, C.K.; Martina, K.; Mutuku, J.M. Molecular detection of Ugandan passiflora virus infecting passionfruit (Passiflora edulis sims) in Rwanda. Annual Research & Review in Biology 2019, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Maina, S.; Jones, R.A. Enhancing biosecurity against virus disease threats to Australian grain crops: Current situation and future prospects. Frontiers in Horticulture 2023, 2, 1263604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A.; Naidu, R.A. Global dimensions of plant virus diseases: Current status and future perspectives. Annual review of virology 2019, 6, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuze, J.; Savenkov, E.; Valkonen, J. Complete genome sequence and analyses of the subgenomic RNAs of Sweet potato chlorotic stunt virus reveal several new features for the genus Crinivirus. Journal of Virology 2002, 76, 9260–9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasswa, P. Sweet potato viruses in Uganda: Identification of a new virus, a mild strain of an old virus and reversion. University of Greenwich, 2012.

- Tairo, F.; Mukasa, S.B.; Jones, R.A.; Kullaya, A.; Rubaihayo, P.R.; Valkonen, J.P. Unravelling the genetic diversity of the three main viruses involved in sweet potato virus disease (SPVD), and its practical implications. Molecular Plant Pathology 2005, 6, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugume, A.K.; Mukasa, S.B.; Kalkkinen, N.; Valkonen, J.P. Recombination and selection pressure in the ipomovirus Sweet potato mild mottle virus (Potyviridae) in wild species and cultivated sweetpotato in the centre of evolution in East Africa. Journal of general virology 2010, 91, 1092–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, S. Application of viral genomics to study the connectivity between crop viruses from northern Australia and neighbouring countries. 2018.

- Gonçalves, Z.S.; Lima, L.K.S.; Soares, T.L.; Abreu, E.F.M.; de Jesus Barbosa, C.; Cerqueira-Silva, C.B.M.; de Jesus, O.N.; de Oliveira, E.J. Identification of Passiflora spp. genotypes resistant to Cowpea aphid-borne mosaic virus and leaf anatomical response under controlled conditions. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 231, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.-H.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Cheng, H.-W.; Huang, Y.-C.; Yeh, S.-D. The virus causing passionfruit woodiness disease in Taiwan is reclassified as East Asian passiflora virus. Journal of General Plant Pathology 2018, 84, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Losada, M.; Arenas, M.; Galán, J.C.; Palero, F.; González-Candelas, F. Recombination in viruses: Mechanisms, methods of study, and evolutionary consequences. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2015, 30, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M.J.; Weiller, G.F. Evidence that a plant virus switched hosts to infect a vertebrate and then recombined with a vertebrate-infecting virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1999, 96, 8022–8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefeuvre, P.; Moriones, E. Recombination as a motor of host switches and virus emergence: Geminiviruses as case studies. Current Opinion in Virology 2015, 10, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Candia, C.; Espada, C.; Duette, G.; Ghiglione, Y.; Turk, G.; Salomón, H.; Carobene, M. Viral replication is enhanced by an HIV-1 intersubtype recombination-derived Vpu protein. Virology Journal 2010, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample No. | HTS No. | Cultivar | Fruit type | Viral like disease symptoms | County | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | 1_S1_L001 | KPF 11 | Yellow | Symptomatic | Kirinyaga | Central |

| K2 | 2_S2_L001 | KPF 11 | Yellow | Symptomatic | Kirinyaga | Central |

| K3 | 3_S3_L001 | KPF4 | Yellow | Symptomatic | Kirinyaga | Central |

| K4 | 4_S4_L001 | KPF 12 | Yellow | Symptomatic | Kiambu | Central |

| K5 | 5_S5_L001 | KPF 4 | Yellow | Symptomatic | Kiambu | Central |

| K6 | 6_S6_L001 | KPF4 | Yellow | Asymptomatic | Muranga | Central |

| K7 | 7_S7_L001 | Unknown | Hardy shell | Symptomatic | Muranga | Central |

| K8 | 8_S8_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Kiambu | Central |

| K9 | 9_S9_L001 | Unknown | Sweet yellow | Symptomatic | Kiambu | Central |

| K10 | 10_S10_L001 | Unknown | Sweet yellow | Symptomatic | Kiambu | Central |

| K11 | 11_S11_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Nakuru | Rift Valley |

| K12 | 12_S12_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Uasin Gishu | Rift Valley |

| K13 | 13_S13_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Uasin Gishu | Rift Valley |

| K14 | 14_S14_L001 | Unknown | Yellow | Symptomatic | Elgeyo Marakwet | Rift Valley |

| K15 | 15_S15_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Elgeyo Marakwet | Rift Valley |

| K16 | 16_S16_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Elgeyo Marakwet | Rift Valley |

| K17 | 17_S17_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Elgeyo Marakwet | Rift Valley |

| K18 | 18_S18_L001 | Unknown | Purple | Symptomatic | Elgeyo Marakwet | Rift Valley |

| K19 | 19_S19_L001 | Unknown | Grafted | Symptomatic | Trans Nzoia | Rift Valley |

| K20 | 20_S20_L001 | Unknown | Grafted | Symptomatic | Trans Nzoia | Rift Valley |

| K21 | 21_S21_L001 | Unknown | Grafted | Symptomatic | Trans Nzoia | Rift Valley |

| K22 | 22_S22_L001 | Unknown | Grafted | Symptomatic | Kakamega | Western |

| Sample | Raw reads | Virus identified | Contig length | Sequence reads mapped | Average depth | normalized depth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1_KC | 1,545,706 | UPV-I | 9,684 | 13,294 | 183 | 118.6 | |

| 2_KA 2_KD |

1,509,132 | EAPDV | 9,638 | 17,410 | 232.5 | 154.1 | |

| UPV-I | 9,679 | 175,623 | 2,307. | 1,529 | |||

| 3_KE | 3,200,244 | UPV-I | 9,670 | 36,941 | 516.8 | 161.5 | |

| 6_KF | 2,547,696 | UPV-I | 9,650 | 4,424 | 61.9 | 24.3 | |

| 7_KH 7_KB |

1,149,924 | UPV-I | 9,779 | 66,140 | 939.9 | 817.4 | |

| EAPDV | 9,638 | 11,276 | 162 | 141 | |||

| 8_KI | 1,465,364 | UPV-I | 9,874 | 85,227 | 1,217 | 830.7 | |

| 11_KJ 11_KP |

2,578,474 | UPV-I | 9,669 | 9,217 | 117.9 | 45.8 | |

| UPV-II | 9,654 | 14,188 | 181.7 | 70.5 | |||

| CABMV (Munguti et al. 2020) | 9,846 | 14,888 | 185.9 | 72.1 | |||

| 12_KK 12_KQ |

2,706,154 | UPV-I* | 9,650 | 75,058 | 1,039.6 | 384.2 | |

| UPV-II* | 9,669 | 32,348 | 431.3 | 159.4 | |||

| 13_KR 13_KW |

1,779,280 | UPV-II | 9,877 | 81,444 | 1,151.8 | 647.4 | |

| UPV-III | 9,683 | 43,291 | 620.2 | 348.6 | |||

| 14_KL 14_KS |

2,974,246 | UPV-I* | 9,629 | 9,318 | 131.3 | 44.1 | |

| UPV-II | 9,771 | 220,180 | 3,062.3 | 1,029.6 | |||

| 15_KT 15_KM |

1,706,154 | UPV-II | 9,658 | 77,940 | 1,044.6 | 612.2 | |

| UPV-III | 9,667 | 127,649 | 1,696.5 | 994.3 | |||

| 16_KU | 1,627,772 | UPV-II | 9,677 | 41,050 | 557 | 342.3 | |

| 17_KG | 2,400,688 | UPV-I | 9,651 | 232,782 | 3,159 | 1,315.9 | |

| 18_KN 18_KV |

2,395,822 | UPV-I | 9,671 | 185,274 | 2,619 | 1,093.3 | |

| UPV-II | 9,680 | 126,554 | 1,792.6 | 748 | |||

| 19_KO | 1,847,440 | UPV-I | 9,636 | 55,234 | 735.9 | 398.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).