Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification of the Typical Tandem Repeats in Water Hyacinth Genome

2.2. Chromosome Distribution Patterns of Candidate Typical Tandem Repeats in Water Hyacinth Genome

2.3. Genomic Structure of the Centromeric Tandem Repeat in Water Hyacinth Genome

2.4. Genomic Structure of the Telomere and Tandem Repeat of Interstitial Chromosome Regions (ICREc) at the Chromosome Ends of Water Hyacinth

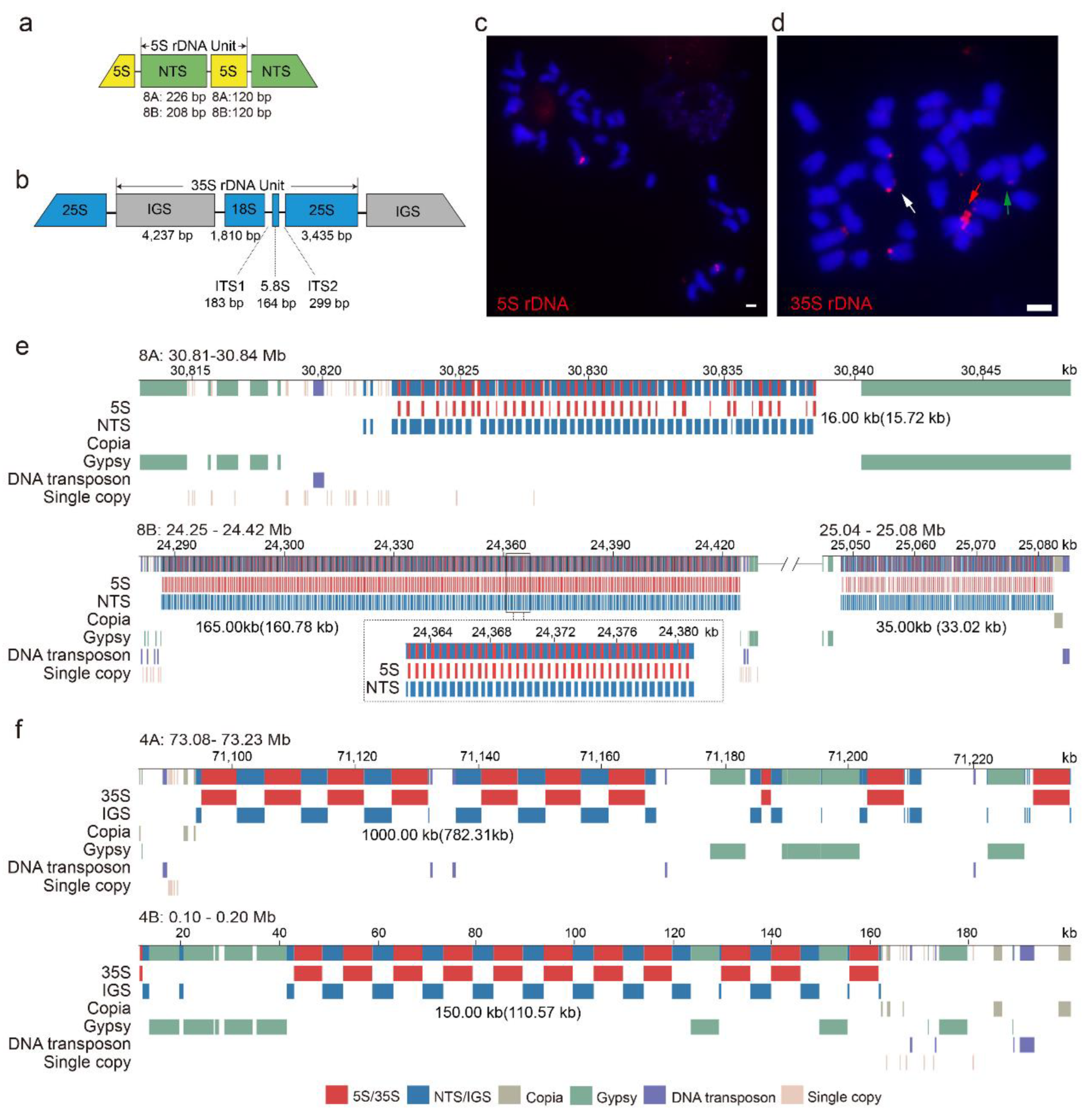

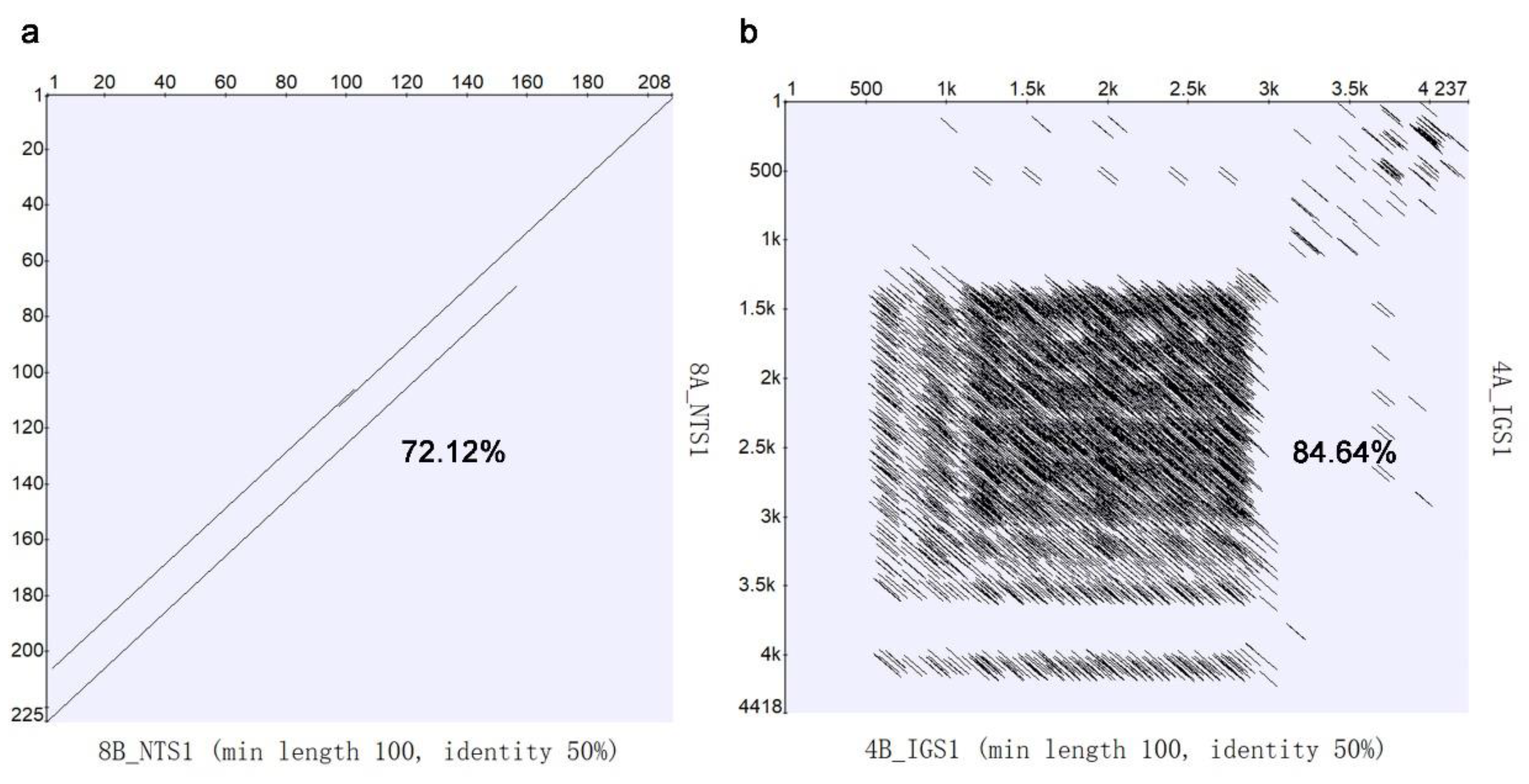

2.5. Genomic Structure of 5S and 35S rDNA Arrays in Water Hyacinth Genome

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Genomic DNA Extraction

4.2. De Novo Identification of Genomic Repeats and Chromosome Distribution Analysis

4.3. PCR Amplification and Probe Preparation

4.4. Chromosome Preparation and FISH

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ben Bakrim, W.; Ezzariai, A.; Karouach, F.; et al. Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms: A comprehensive review of its chemical composition, traditional use, and value-added products. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 842511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzariai, A.; Hafidi, M.; Ben Bakrim, W.; et al. Identifying advanced biotechnologies to generate biofertilizers and biofuels from the world's worst aquatic weed. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9, 769366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamood, M.; Khan, F. R.; Zahir, F.; et al. Bagarius bagarius, and Eichhornia crassipes are suitable bioindicators of heavy metal pollution, toxicity, and risk assessment. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, S.; Lv, X.; et al. Eichhornia crassipes-rhizospheric biofilms contribute to nutrients removal and methane oxidization in wastewater stabilization ponds receiving simulative sewage treatment plants effluents. Chemosphere 2023, 322, 138100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M. N.; Rahman, F.; Papri, S. A.; et al. Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms.) as an alternative raw material for the production of bio-compost and handmade paper. J Environ Manage 2021, 294, 113036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Navrátilová, A.; Koblížková, A.; et al. Plant centromeric retrotransposons: A structural and cytogenetic perspective. Mob DNA 2011, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingerhut, J. M.; Yamashita, Y. M. The regulation and potential functions of intronic satellite DNA. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2022, 128, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Wettstein, D.; Rasmussen, S. W.; Holm, P. B. The synaptonemal complex in genetic segregation. Annu Rev Genet 1984, 18, 331–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemayel, R.; Cho, J.; Boeynaems, S.; et al. Beyond junk-variable tandem repeats as facilitators of rapid evolution of regulatory and coding sequences. Genes 2012, 3, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anamthawat-Jónsson, K.; Wenke, T.; Thórsson, A. T.; et al. Evolutionary diversification of satellite DNA sequences from Leymus (Poaceae: Triticeae). Genome 2009, 52, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naish, M.; Alonge, M.; Wlodzimierz, P.; et al. The genetic and epigenetic landscape of the Arabidopsis centromeres. Science 2021, 374, eabi7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J. M.; Xie, W. Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Two gap-free reference genomes and a global view of the centromere architecture in rice. Mol Plant 2021, 14, 1757–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altemose, N.; Logsdon, G. A.; Bzikadze, A. V.; et al. Complete genomic and epigenetic maps of human centromeres. Science 2022, 376, eabl4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, B.; Hua, X.; et al. A complete gap-free diploid genome in Saccharum complex and the genomic footprints of evolution in the highly polyploid Saccharum genus. Nat Plants 2023, 9, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, B.; Hua, X.; et al. A near-complete genome assembly of the allotetrapolyploid Cenchrus fungigraminus (JUJUNCAO) provides insights into its evolution and C4 photosynthesis. Plant Commun 2023, 4, 100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamusová, K.; Khosravi, S.; Fujimoto, S.; et al. Two combinatorial patterns of telomere histone marks in plants with canonical and non-canonical telomere repeats. Plant J 2020, 102, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Leandre, B.; Levine, M. T. The telomere paradox: Stable genome preservation with rapidly evolving proteins. Trends Genet 2020, 36, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G. A.; Gong, Z.; Iovene, M.; et al. Organization and evolution of subtelomeric satellite repeats in the potato genome. G3 2011, 1, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.; Kovařík, A.; Leitch, A. R.; et al. Cytogenetic features of rRNA genes across land plants: Analysis of the Plant rDNA database. Plant J 2017, 89, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, P.; Schaefer, H.; Telford, I. R.; et al. Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and melon (C. melo) have numerous wild relatives in Asia and Australia, and the sister species of melon is from Australia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 14269–14273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, R. A.; Panchuk, I.I.; Borisjuk, N. V.; et al. Evolutional dynamics of 45S and 5S ribosomal DNA in ancient allohexaploid Atropa belladonna. BMC Plant Biol 2017, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam-Faridi, N.; Hodnett, G. L.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; et al. Cyto-molecular characterization of rDNA and chromatin composition in the NOR-associated satellite in Chestnut (Castanea spp.). Sci Rep 2024, 14, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Li, R.; Ren, X.; et al. Genomic architecture of 5S rDNA cluster and its variations within and between species. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Garcia, S.; et al. Intragenomic rDNA variation - the product of concerted evolution, mutation, or something in between? Heredity 2023, 131, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolzhenko, E.; English, A.; Dashnow, H.; et al. Characterization and visualization of tandem repeats at genome scale. Nat Biotechnol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logsdon, G. A.; Vollger, M. R.; Eichler, E. E. Long-read human genome sequencing and its applications. Nat Rev Genet 2020, 21, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, P.; Neumann, P.; Macas, J. Global analysis of repetitive DNA from unassembled sequence reads using RepeatExplorer2. Nat Protoc 2020, 15, 3745–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.; Yu, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K. Species-specific abundant retrotransposons elucidate the genomic composition of modern sugarcane cultivars. Chromosoma 2020, 129, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, T.; et al. Amplification and adaptation of centromeric repeats in polyploid switchgrass species. New Phytol 2018, 218, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Pavlíková, Z.; Koblížková, A.; et al. Centromeres off the hook: Massive changes in centromere size and structure following duplication of CenH3 gene in Fabeae species. Mol Biol Evol 2015, 32, 1862–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitkam, T.; Weber, B.; Walter, I.; et al. Satellite DNA landscapes after allotetraploidization of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) reveal unique A and B subgenomes. Plant J 2020, 103, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Ding, W.; Zhang, M.; et al. The formation and evolution of centromeric satellite repeats in Saccharum species. Plant J 2021, 106, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Genomic and cytogenetic analyses reveal satellite repeat signature in allotetraploid okra (Abelmoschus esculentus). BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macas, J.; Ávila Robledillo, L.; Kreplak, J.; Novák, P.; Koblížková, A.; Vrbová, I.; Burstin, J.; Neumann, P. Assembly of the 81. 6 Mb centromere of pea chromosome 6 elucidates the structure and evolution of metapolycentric chromosomes. PLoS Genet 2023, 19, e1010633. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Dong, F.; Langdon, T.; et al. Functional rice centromeres are marked by a satellite repeat and a centromere-specific retrotransposon. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1691–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. O.; Watase, G. J.; Warsinger-Pepe, N.; et al. Mechanisms of rDNA copy number maintenance. Trends Genet 2019, 35, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almojil, D.; Bourgeois, Y.; Falis, M.; Hariyani, I.; Wilcox, J.; Boissinot, S. The Structural, Functional and Evolutionary Impact of Transposable Elements in Eukaryotes. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henikoff, S.; Ahmad, K.; Malik, H. S. The centromere paradox: Stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science 2001, 293, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Ishii, T.; Brown, C. T.; et al. Centromere location in Arabidopsis is unaltered by extreme divergence in CENH3 protein sequence. Genome Res 2017, 27, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miga, K. H. The promises and challenges of genomic studies of human centromeres. Prog Mol Subcell Biol 2017, 56, 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, L.; Xie, L.; Shang, N.; Wu, D.; Ye, C.; Rudell, E. C.; Okada, K.; Zhu, Q. H.; Song, B. K.; Cai, D.; Junior, A. M.; Bai, L.; Fan, L. A reference genome of Commelinales provides insights into the commelinids evolution and global spread of water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes). Gigascience 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Shi, Q.; Huang, Y.; Han, F. Centromere Satellite Repeats Have Undergone Rapid Changes in Polyploid Wheat Subgenomes. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 2035–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Birchler, J. A.; Han, F.; Yang, N.; Su, H. Three near-complete genome assemblies reveal substantial centromere dynamics from diploid to tetraploid in Brachypodium genus. Genome Biol 2024, 25, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Gill, N.; Kim, H. R.; et al. A lineage-specific centromere retrotransposon in Oryza brachyantha. Plant J 2009, 60, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Masonbrink, R. E.; Shan, W.; et al. Rapid proliferation and nucleolar organizer targeting centromeric retrotransposons in cotton. Plant J 2016, 88, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naish, M.; Henderson, I. R. The structure, function, and evolution of plant centromeres. Genome Res 2024, 34, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Wolfgruber, T. K.; Presting, G. G. Tandem repeats derived from centromeric retrotransposons. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tek, A. L.; Jiang, J. The centromeric regions of potato chromosomes contain megabase-sized tandem arrays of telomere-similar sequence. Chromosoma 2004, 113, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrátilová, P.; Toegelová, H.; Tulpová, Z.; et al. Prospects of telomere-to-telomere assembly in barley: Analysis of sequence gaps in the MorexV3 reference genome. Plant Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulnecková, J.; Sevcíková, T.; Fajkus, J.; et al. A broad phylogenetic survey unveils the diversity and evolution of telomeres in eukaryotes. Genome Biol Evol 2013, 5, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Tan, K.; et al. A complete telomere-to-telomere assembly of the maize genome. Nat Genet 2023, 55, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricchetti, M.; Dujon, B.; Fairhead, C. Distance from the chromosome end determines the efficiency of double strand break repair in subtelomeres of haploid yeast. J Mol Biol 2003, 328, 847–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, H. W. Telomere dynamics unique to meiotic prophase: Formation and significance of the bouquet. Cell Mol Life Sci 2003, 60, 2319–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mefford, H. C.; Trask, B. J. The complex structure and dynamic evolution of human subtelomeres. Nat Rev Genet 2002, 3, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, Y.; Engel, C.; Kobayashi, T. Regulation of ribosomal RNA gene copy number, transcription and nucleolus organization in eukaryotes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2023, 24, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselló, J. A.; Maravilla, A. J.; Rosato, M. The Nuclear 35S rDNA World in Plant Systematics and Evolution: A Primer of Cautions and Common Misconceptions in Cytogenetic Studies. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 788911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.; Yu, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K. Species-specific abundant retrotransposons elucidate the genomic composition of modern sugarcane cultivars. Chromosoma 2020, 129, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, T.; Fujisawa, M.; Takenaka, M.; et al. Bryophyte 5S rDNA was inserted into 45S rDNA repeat units after the divergence from higher land plants. Plant Mol Biol 1999, 41, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galián, J. A.; Rosato, M.; Rosselló, J. A. Early evolutionary colocalization of the nuclear ribosomal 5S and 45S gene families in seed plants: Evidence from the living fossil gymnosperm Ginkgo biloba. Heredity 2012, 108, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganley, A. R.; Kobayashi, T. Highly efficient concerted evolution in the ribosomal DNA repeats: Total rDNA repeat variation revealed by whole-genome shotgun sequence data. Genome Res 2007, 17, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, U. K.; Weiss, M. Intragenomic variation of fungal ribosomal genes is higher than previously thought. Mol Biol Evol 2008, 25, 2251–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, M. M.; Kurylo, C. M.; Dass, R. A.; et al. Variant ribosomal RNA alleles are conserved and exhibit tissue-specific expression. Sci Adv 2018, 4, eaao0665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, I.; Chintauan-Marquier, I. C.; Veltsos, P.; et al. Ribosomal DNA in the grasshopper Podisma pedestris: Escape from concerted evolution. Genetics 2006, 174, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, J.; Sestini, G.; Elgert, C.; et al. Sequencing of the Arabidopsis NOR2 reveals its distinct organization and tissue-specific rRNA ribosomal variants. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulpová, Z.; Kovařík, A.; Toegelová, H.; et al. Fine structure and transcription dynamics of bread wheat ribosomal DNA loci deciphered by a multi-omics approach. Plant Genome 2022, 15, e20191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodzimierz, P.; Rabanal, F. A.; Burns, R.; et al. Cycles of satellite and transposon evolution in Arabidopsis centromeres. Nature 2023, 618, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miga, K. H. Centromere studies in the era of 'telomere-to-telomere' genomics. Exp Cell Res 2020, 394, 112127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, I.; et al. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).