Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

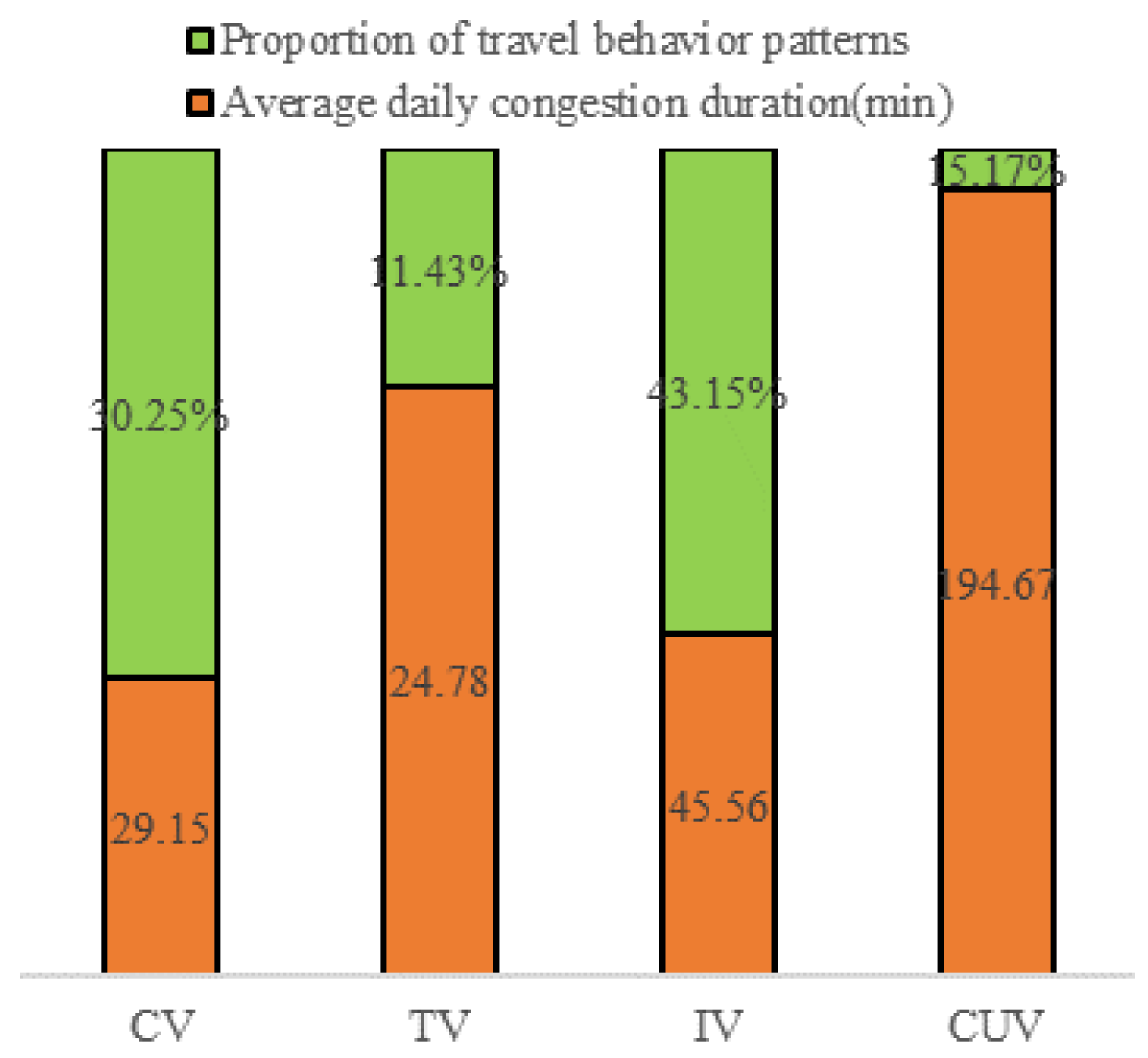

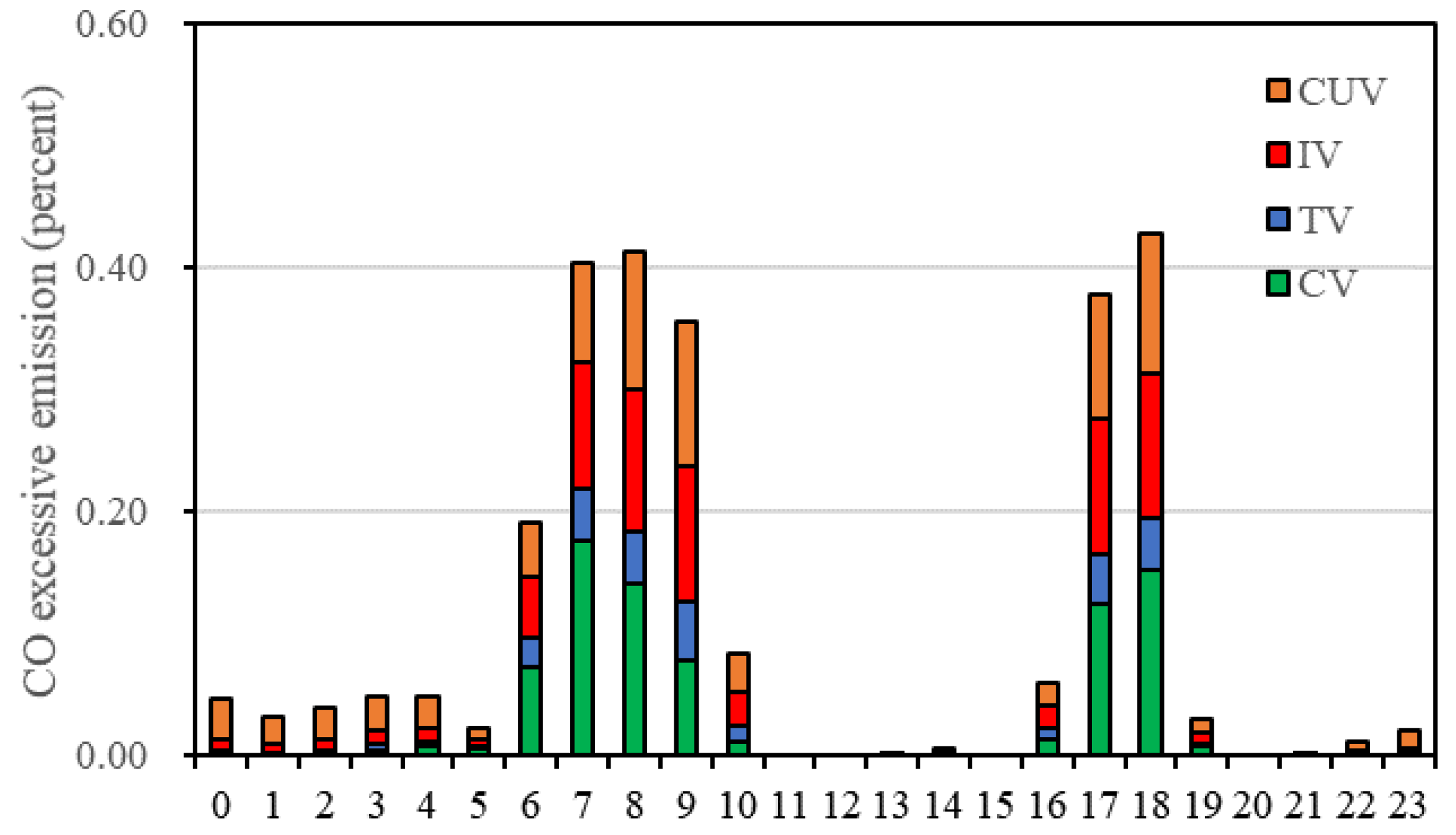

Understanding vehicle travel behavior patterns is essential for managing urban traffic congestion, as well as for addressing the associated congestion risks and excess emissions. This study, based on one week of License Plate Recognition (LPR) data from urban expressway networks, investigates different travel behavior patterns and their related congestion risks and emissions. First, we classify vehicles into distinct travel patterns based on spatiotemporal features extracted from LPR data and propose a scalable pattern recognition method suitable for large-scale applications. We then assess the congestion risks associated with each pattern and estimate the excess emissions resulting from congestion. The results reveal substantial variation in congestion risks across different travel patterns, with congestion risks following a bimodal distribution, influenced by temporal traffic flow rhythms. Furthermore, the excess emissions from congestion caused by commercially used vehicles (CUVs) are comparable to those of individually owned vehicles (IVs), despite CUVs constituting only one-third of the total vehicle count. This suggests that focusing solely on commuter travel modes underestimates both congestion risks and excess emissions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A novel method for dividing travel behavior patterns based on a unique set of spatiotemporal feature indicators is proposed. This method uses clustering to identify homogeneous clusters from data features, overcoming the subjectivity and limitations of traditional threshold-based approaches.

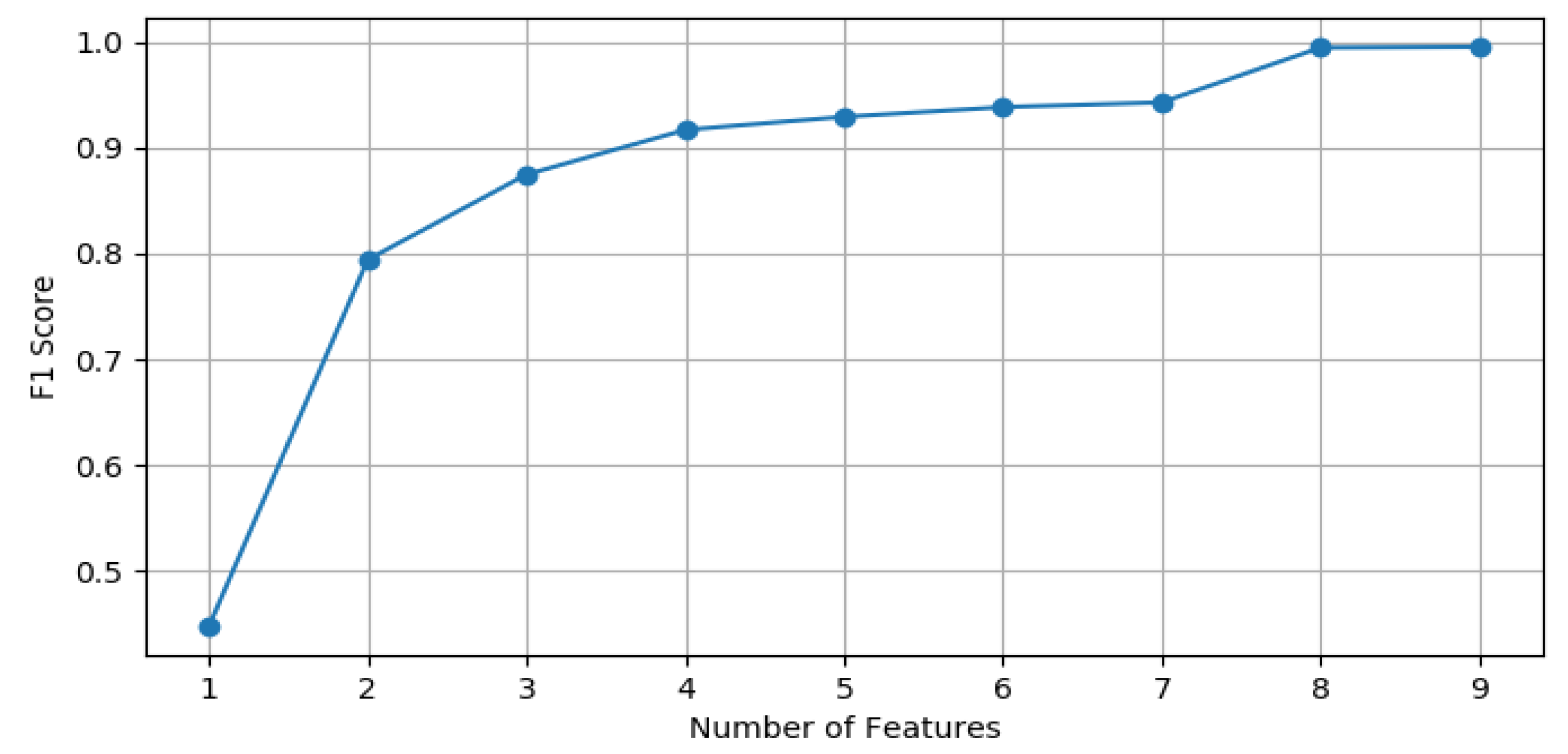

- A pattern recognition method suitable for large-scale applications is presented, demonstrating strong recognition performance with only three feature values.

- The congestion risks and excess emissions of various travel patterns are analyzed based on real-world LPR data. The findings offer important insights for individual travel time planning and health management, and provide support for the development of personalized, proactive traffic demand management measures.

2.1. Study Area and Data

| Name | Information | Explanation |

| CardID | 442311111111111111 | Serial number of the detector |

| PlaceCode | 50122 | Serial number of detector’s location |

| Latitude | 39.921111 | Information of latitude |

| Longitude | 116.461111 | Information of longitude |

| Name | Information | Explanation |

| MotorVehicleID | 114211111111111111 | Serial number of the record |

| PlateNo | Yue B.XXXXX | License plate number |

| PlateColor | 02 | Type of car |

| PassTime | 2022-08-05 02:29:30 | Time of record |

| Roadclid | 7285 | Serial number of the road segment |

| CardID | 442311111111111111 | Serial number of the detector |

2.2. Identification of Travel Behavior Patterns

2.2.1. Construction of Spatiotemporal Feature Indicators

2.2.2. Classification of Travel Behavior Patterns

2.2.3. Travel Behavior Pattern Recognition

2.3. Estimation of Congestion Risk and Excessive Emissions

3. Result

3.1. Identification Results of Travel Behavior Patterns

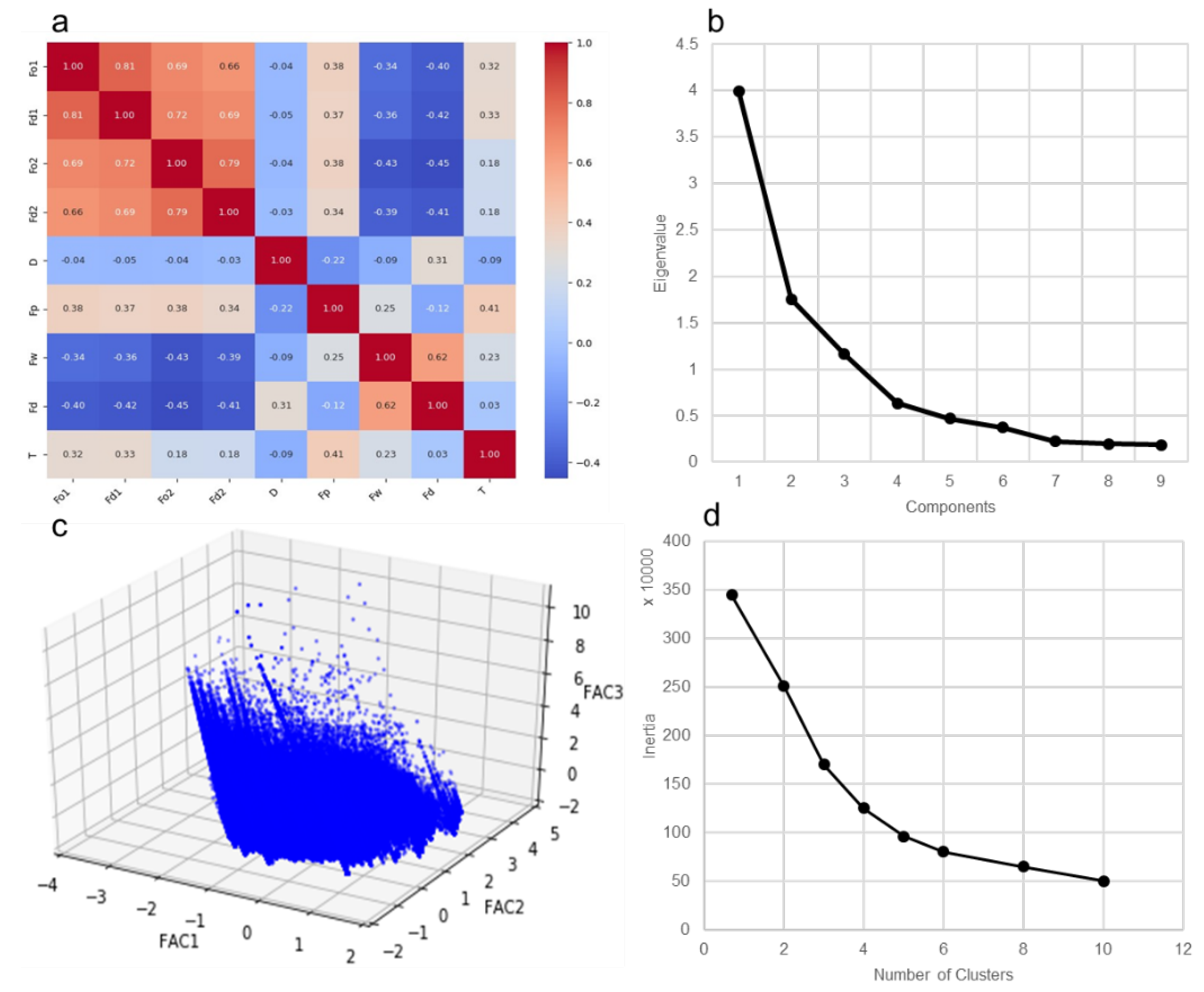

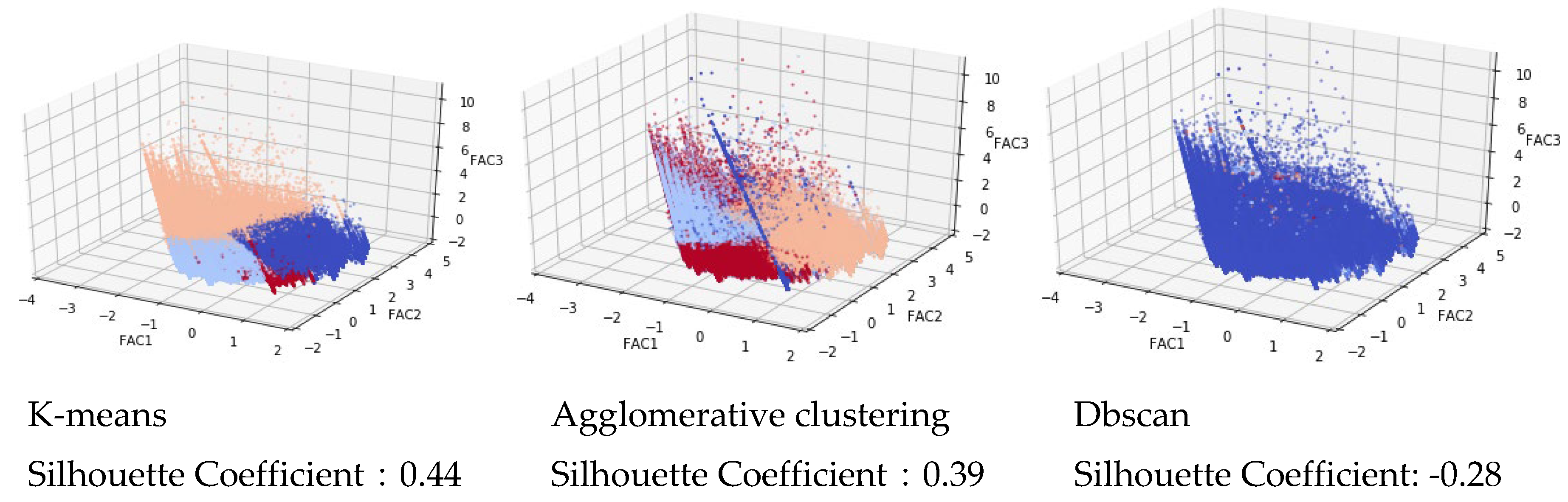

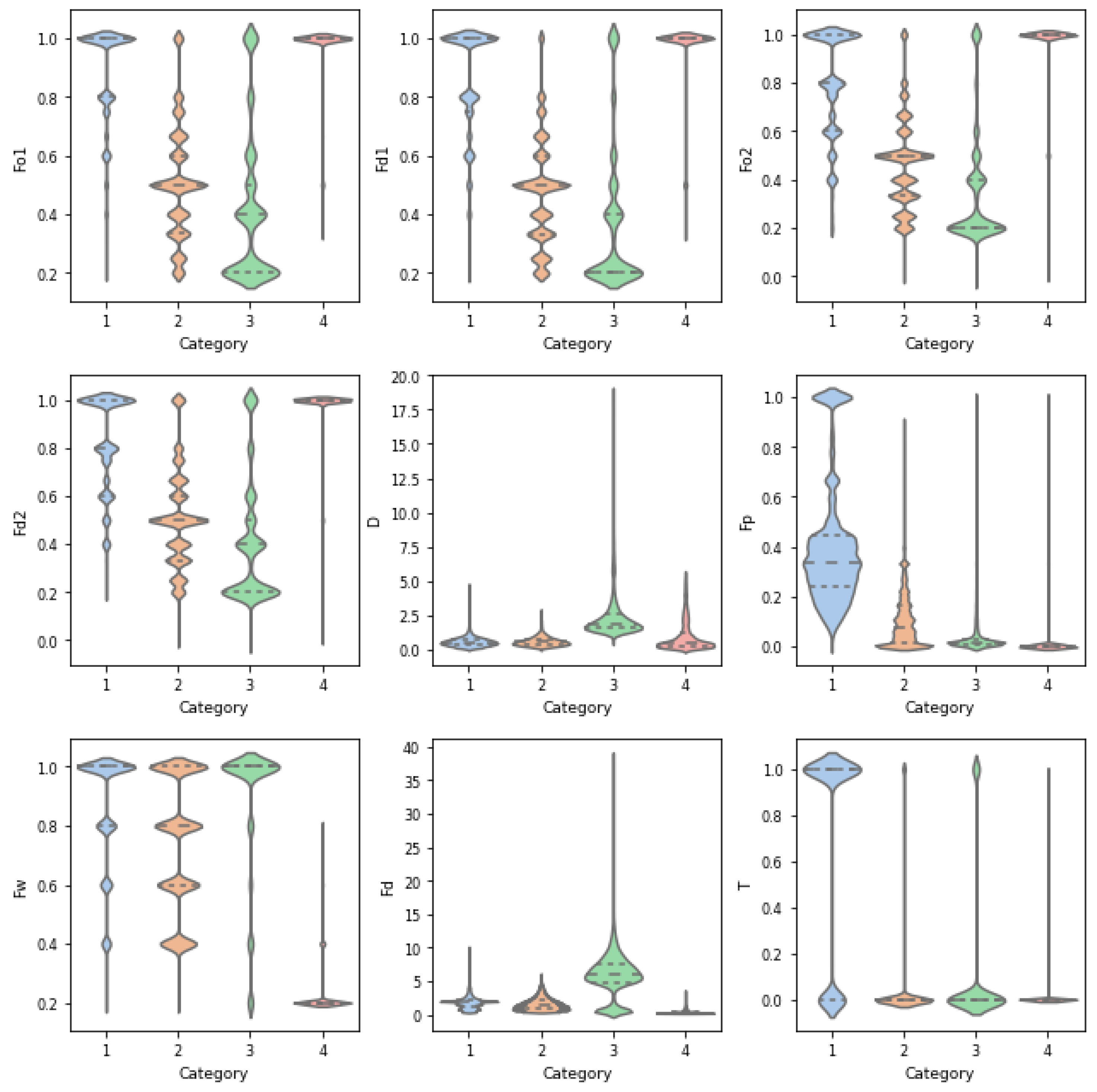

3.1.1. Results of Clustering: Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering Outcomes

| Travel partterns | Fo1 | Fd1 | Fo2 | Fd2 | D | Fp | Fw | Fd | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.28 | 0.4 | 0.86 | 2.09 | 0.68 |

| 2 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.1 | 0.74 | 2.18 | 0.04 |

| 3 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 1.16 | 0.04 | 0.89 | 6.66 | 0.1 |

| 4 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 1.59 | 0 |

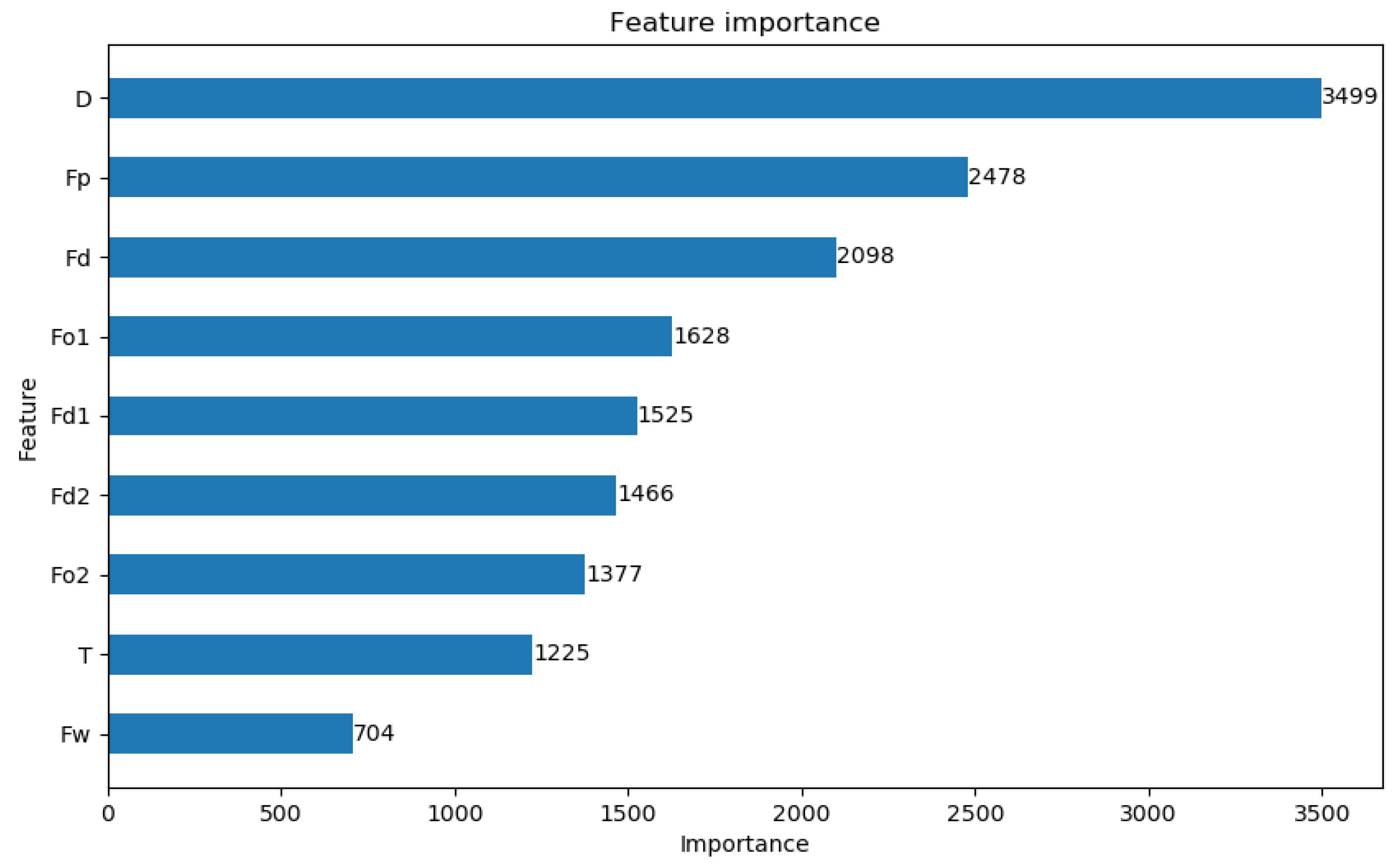

3.1.2. Recognition Results of Classification Model

3.2. Congestion Risk Associated with Different Travel Behavior Patterns

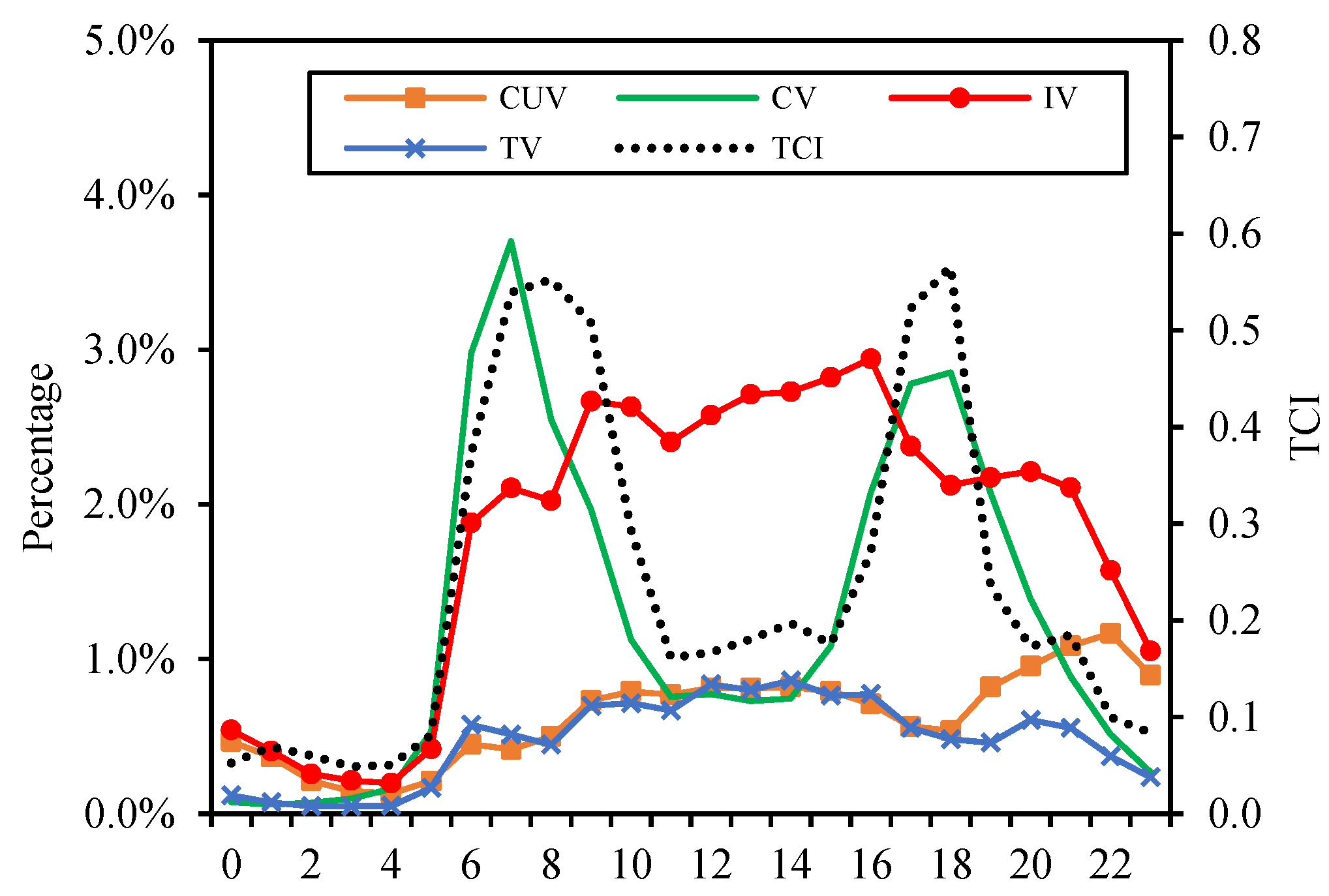

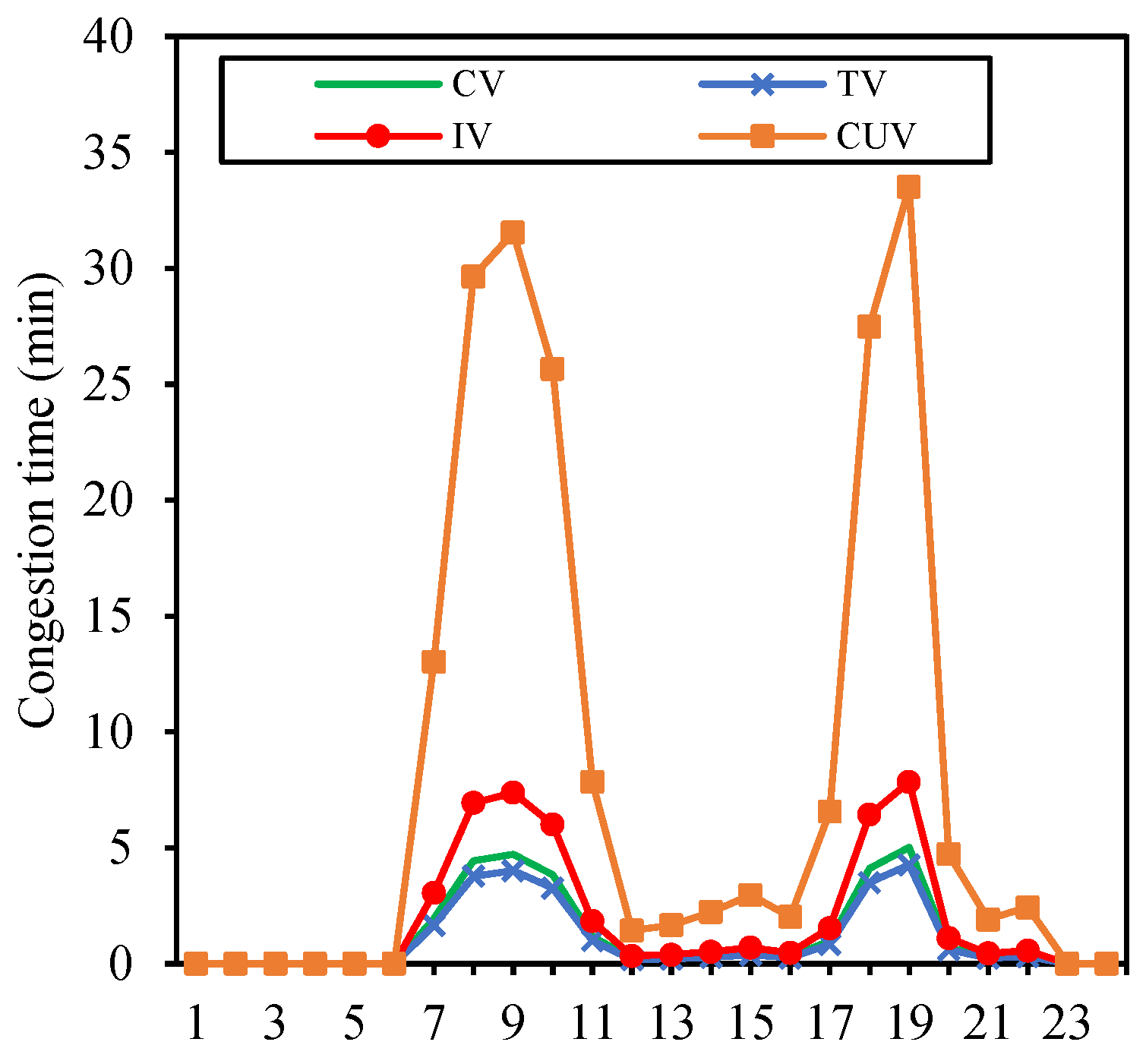

3.2.1. Time Distribution of Congestion for Each Pattern

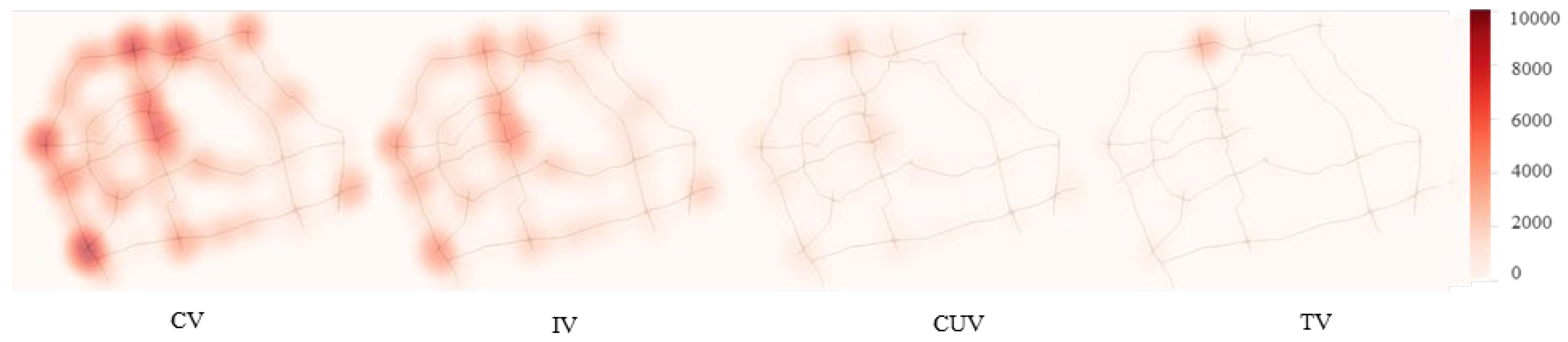

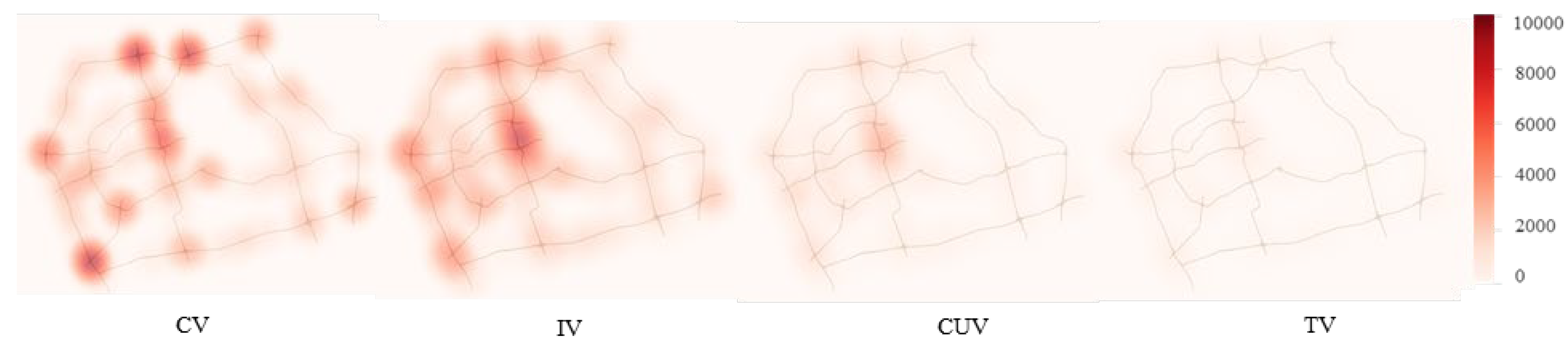

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution of Congestion for Each Pattern

3.3. Excessive Emissions from Various Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on the Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Congestion Risks of Various Patterns

4.2. Discussion on Strategies to Reduce Congestion Risks

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Disclosure statement

Data availability statement

References

- Sandow, E.; Westerlund, O.; Lindgren, U. Is Your Commute Killing You? On the Mortality Risks of Long-Distance Commuting. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2014, 46, 1496–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, J.; Walker, R. Traffic Congestion and Infant Health: Evidence from E-ZPass. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2011, 3, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigazzi, A. Y.; Figliozzi, M. A.; Clifton, K. J. Traffic Congestion and Air Pollution Exposure for Motorists: Comparing Exposure Duration and Intensity. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2015, 9, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, M. (Xin); Zhang, F. Commuting Behavior and Congestion Satisfaction: Evidence from Beijing, China. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2019, 67, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Cui, Y.; Chen, X.; Bachmann, C.; Yuan, Q. Who Are on the Road? A Study on Vehicle Usage Characteristics Based on One-Week Vehicle Trajectory Data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 1962–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KhorramDehnavi, S.; MorovatiSharifabadi, A.; AghidiKheyrabadi, S.; HosseiniBamakan, S. M. Evaluating Private Car Users’ Preference to Congestion Pricing: A Study on Trip Cancellation Behavior. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2024, 18, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z. An Empirical Study on Travel Patterns of Internet Based Ride-Sharing. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 86, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. (Michael); Zahiri, M.; Zhang, S. Understanding Ridesplitting Behavior of On-Demand Ride Services: An Ensemble Learning Approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 76, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Cao, J.; Chen, C.; Ban, X. (Jeff). Extracting Trips from Multi-Sourced Data for Mobility Pattern Analysis: An App-Based Data Example. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 105, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiola, N.; Raveau, S.; Galilea, P. Modelling Preferences towards Activities and Their Effect on Departure Time Choices. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2019, 129, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Akther, S. Intercity Commuting in Metropolitan Regions: A Mode Choice Analysis of Commuters Traveling to Dhaka from Nearby Cities. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, R.; McNally, M. G. A Structural Analysis of the Work Tour Behavior of Transit Commuters. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2022, 160, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yang, Y.; Gupta, S.; Veneziano, D.; Athavale, S.; González, M. C. The TimeGeo Modeling Framework for Urban Motility without Travel Surveys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, E5370–E5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cai, M.; Xiong, C. Research on Human Travel Correlation for Urban Transport Planning Based on Multisource Data. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, F.; Yan, H.; Xie, S.; Liu, H.; Dai, Z. Activity-Based Model Based on Multi-Day Cellular Data: Considering the Lack of Personal Attributes and Activity Type. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. n/a. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Capra, L.; Wolfson, O.; Yang, H. Urban Computing: Concepts, Methodologies, and Applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiong, G.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, X.; Tarkoma, S.; Huang, M.; Lv, Y.; Wu, C. Trip Purposes Mining From Mobile Signaling Data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 13190–13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Wang, J. Exploring Activity Patterns and Trip Purposes of Public Transport Passengers from Smart Card Data. J. Transp. Eng. Part Syst. 2023, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Shang, P. Effects of Vehicle Restriction Policies: Analysis Using License Plate Recognition Data in Langfang, China. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Yang, D. Using ALPR Data to Understand the Vehicle Use Behaviour under TDM Measures. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 12, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet-Langlois, G.; Koutsopoulos, H. N.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J. Measuring Regularity of Individual Travel Patterns. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chen, X.; He, Z.; Miranda-Moreno, L. F. Routine Pattern Discovery and Anomaly Detection in Individual Travel Behavior. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2023, 23, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zhang, M.; Jin, S.; Ma, D. Understanding Vehicles Commuting Pattern Based on License Plate Recognition Data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Schooling, J. Understanding Non-Commuting Travel Demand of Car Commuters – Insights from ANPR Trip Chain Data in Cambridge. Transp. Policy 2021, 106, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrill, P.; Nachtigall, F.; Javaid, A.; Milojevic-Dupont, N.; Wagner, F.; Creutzig, F. Comparing Urban Form Influences on Travel Distance, Car Ownership, and Mode Choice. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2024, 128, 104087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, T.; Loo, B. P. Y. Cost of Travel Delays Caused by Traffic Crashes. Commun. Transp. Res. 2024, 4, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C. D.; Sweet, M. N.; Kanaroglou, P. S. All Minutes Are Not Equal: Travel Time and the Effects of Congestion on Commute Satisfaction in Canadian Cities. Transportation 2018, 45, 1249–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beland, L.-P.; Brent, D. A. Traffic and Crime. J. Public Econ. 2018, 160, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirimoglu, M.; Ramezani, M.; Amirgholy, M. Staggered Work Schedules for Congestion Mitigation: A Morning Commute Problem. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 132, 103391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravalet, E.; Rérat, P. Teleworking: Decreasing Mobility or Increasing Tolerance of Commuting Distances? Built Environ. 2019, 45, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, C.; Xu, X. Clustering Vehicle Temporal and Spatial Travel Behavior Using License Plate Recognition Data. J. Adv. Transp. 2017, 2017, e1738085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandretti, L.; Lehmann, S. Trip Frequency Is Key Ingredient in New Law of Human Travel. Nature 2021, 593, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warne, R. T.; Larsen, R. Evaluating a Proposed Modification of the Guttman Rule for Determining the Number of Factors in an Exploratory Factor Analysis. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2014, 56, 104–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, Z.; Kwan, M.-P.; Liu, D.; Tang, L.; Chen, Y.; Fang, M. Assessing Individual Activity-Related Exposures to Traffic Congestion Using GPS Trajectory Data. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 98, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, S.; Niu, T.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, K. M.; Wu, Y. High-Resolution Mapping of Vehicle Emissions of Atmospheric Pollutants Based on Large-Scale, Real-World Traffic Datasets. Atmospheric Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 8831–8843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Batterman, S.; Dion, F. Vehicle Emissions in Congestion: Comparison of Work Zone, Rush Hour and Free-Flow Conditions. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 1929–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baro, R.; Rao, K. V. K.; Velaga, N. R. Role of Private Vehicle Commuters’ Travel Wellbeing Perception in Mode Shift Behavior towards an Upcoming Metro in Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2024, 16, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kamargianni, M. Steering Short-Term Demand for Car-Sharing: A Mode Choice and Policy Impact Analysis by Trip Distance. Transportation 2020, 47, 2233–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van ’t Veer, R.; Annema, J. A.; Araghi, Y.; Homem de Almeida Correia, G.; van Wee, B. Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS): A Latent Class Cluster Analysis to Identify Dutch Vehicle Owners’ Use Intention. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2023, 169, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Saberi, M.; Waller, S. T. Capacity Allocation and Tolling-Rewarding Schemes for the Morning Commute with Carpooling. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 142, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavieri, P. S.; Bhat, C. R. Modeling Individuals’ Willingness to Share Trips with Strangers in an Autonomous Vehicle Future. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2019, 124, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, R. Manage Morning Commute for Household Travels with Parking Space Constraints. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 185, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lin, Q.; Jia, N.; Tian, J. The Actual Impact of Ride-Splitting: An Empirical Study Based on Large-Scale GPS Data. Transp. Policy 2024, 147, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (44) Deng, J.; Li, T.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, X. Heterogeneity in Route Choice during Peak Hours: Implications on Travel Demand Management. Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 38, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S. K.; Elumalai, S. P. Assessment of Sustainable School Transport Policies on Vehicular Emissions Using the IVE Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbiasov, T.; Heine, C.; Sabouri, S.; Salazar-Miranda, A.; Santi, P.; Glaeser, E.; Ratti, C. The 15-Minute City Quantified Using Human Mobility Data. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, F.; Zeng, M.; Li, Y.-X. Congestion Pricing for Sustainable Urban Transportation Systems Considering Carbon Emissions and Travel Habits. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J.; Yan, Y.; Chen, L. Bibliometric Analysis of Sustainable Tourism Using CiteSpace. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 202, 123310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).