Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

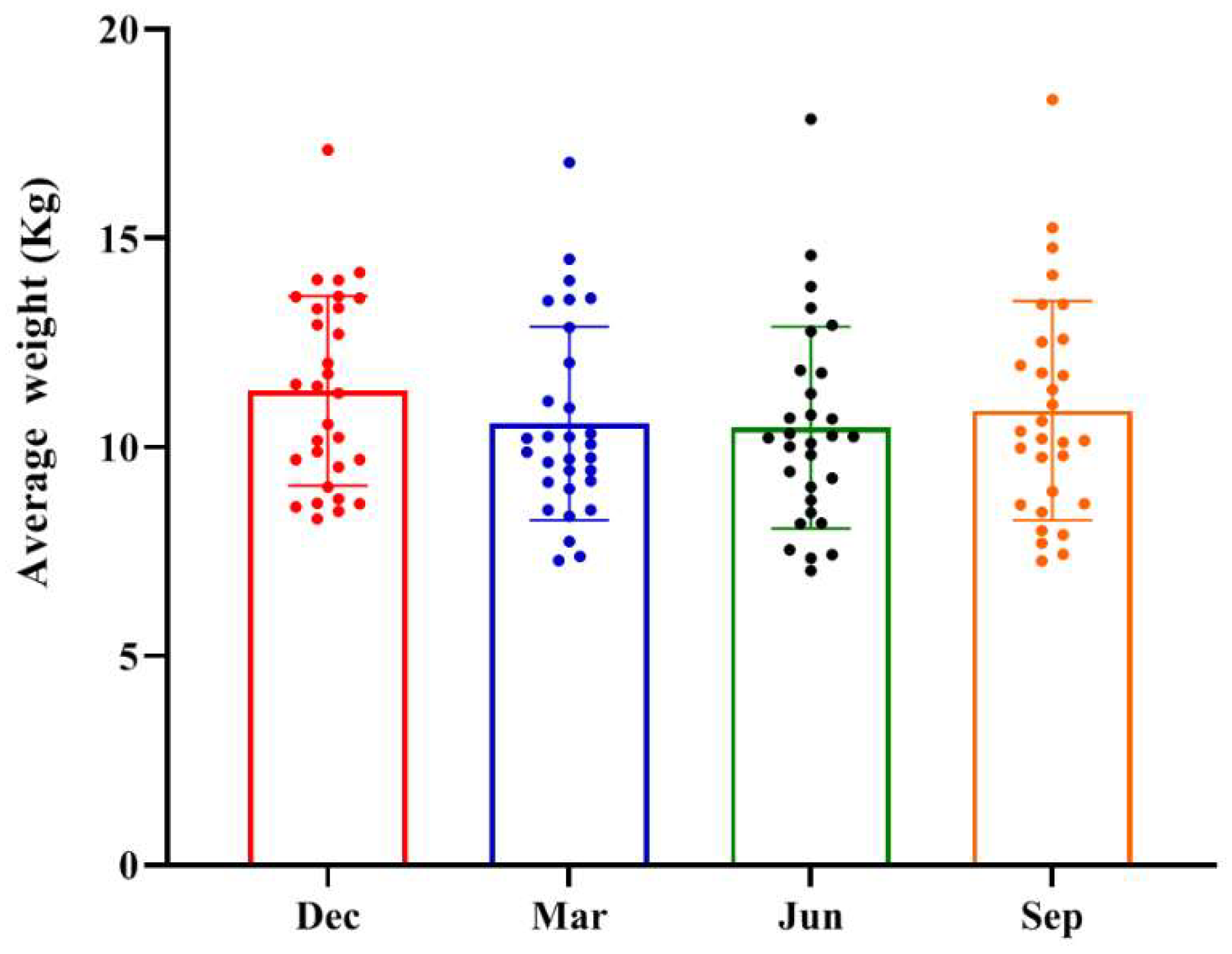

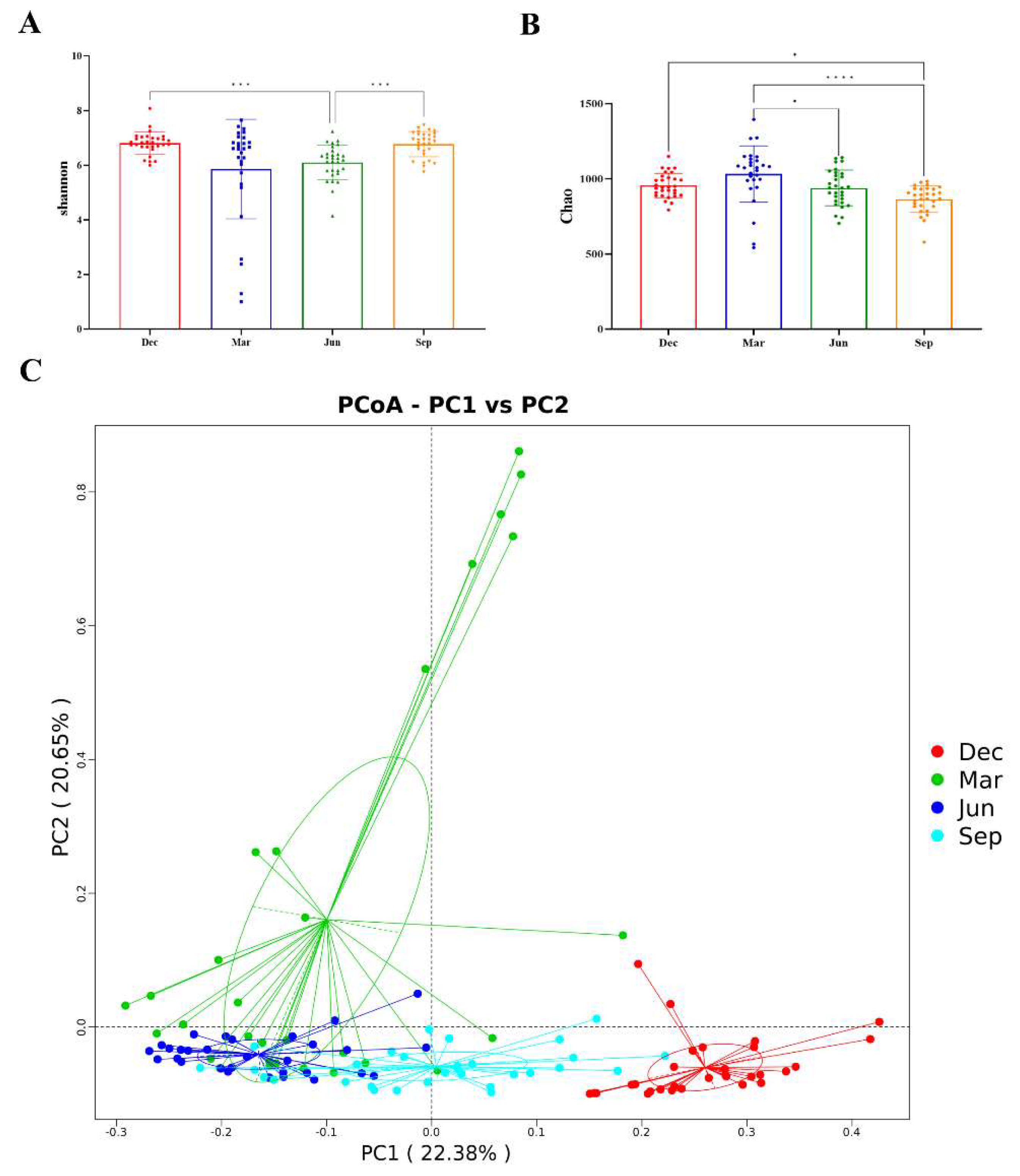

The seasonal variations that occur in the gut microbiota of healthy adult rhesus monkeys kept in outdoor groups under conventional rearing patterns, and how these variations are affected by environmental variables, are relatively poorly understood. In this study, we collected 120 fecal samples from 30 adult male rhesus monkeys kept in outdoor groups across four seasons and recorded the temperature and humidity of the housing facilities as well as the proportions of fruit and vegetables in their diet. 16S rRNA sequencing analysis showed that the alpha diversity of the gut microbiota of the rhesus monkeys was higher in winter and spring than in summer and autumn. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) also revealed significant seasonal differences in the structure and function of the gut microbiota in the rhesus monkeys. The phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes and the genus Prevotella 9 were the significantly dominant groups in all 120 fecal samples from the rhesus monkeys. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis (LDA > 4) indicated that, at the phylum level, Firmicutes was significantly enriched in winter, Bacteroidetes was significantly enriched in summer, and Proteobacteria and Campylobacter were significantly enriched in spring. At the genus level, Helicobacter and Ralstonia were significantly enriched in spring; Prevotella 9, Streptococcus, and Prevotella were significantly enriched in summer, and UCG_005 was significantly enriched in autumn. The beneficial genera Lactobacillus, Limosilactobacillus, and Ligilactobacillus, and the beneficial species Lactobacillus johnsonii, Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus murinus, and Lactobacillus amylovorus, all showed the same seasonal trend, namely, their average relative abundance was significantly higher in winter than in other seasons. Compared with other seasons, carbohydrate metabolic function was significantly upregulated in winter (p < 0.01), amino acid metabolic function was relatively increased in spring, and energy metabolic function and the metabolic function of cofactors and vitamins were significantly downregulated in winter and relatively upregulated in summer. Variance partitioning analysis (VPA) and redundancy analysis (RDA) showed that the proportions of fruits and vegetables in the diet, but not climatic factors (temperature and humidity), significantly influenced the seasonal changes in the gut microbiota. These variations were related to changes in the proportions of fruits and vegetables. This study provides new evidence relating to how external environmental factors affect the intestinal environment of rhesus monkeys.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

2.2. Fecal Sample Collection

2.3. Environmental Factors

2.4. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Data Quality Control

2.5.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

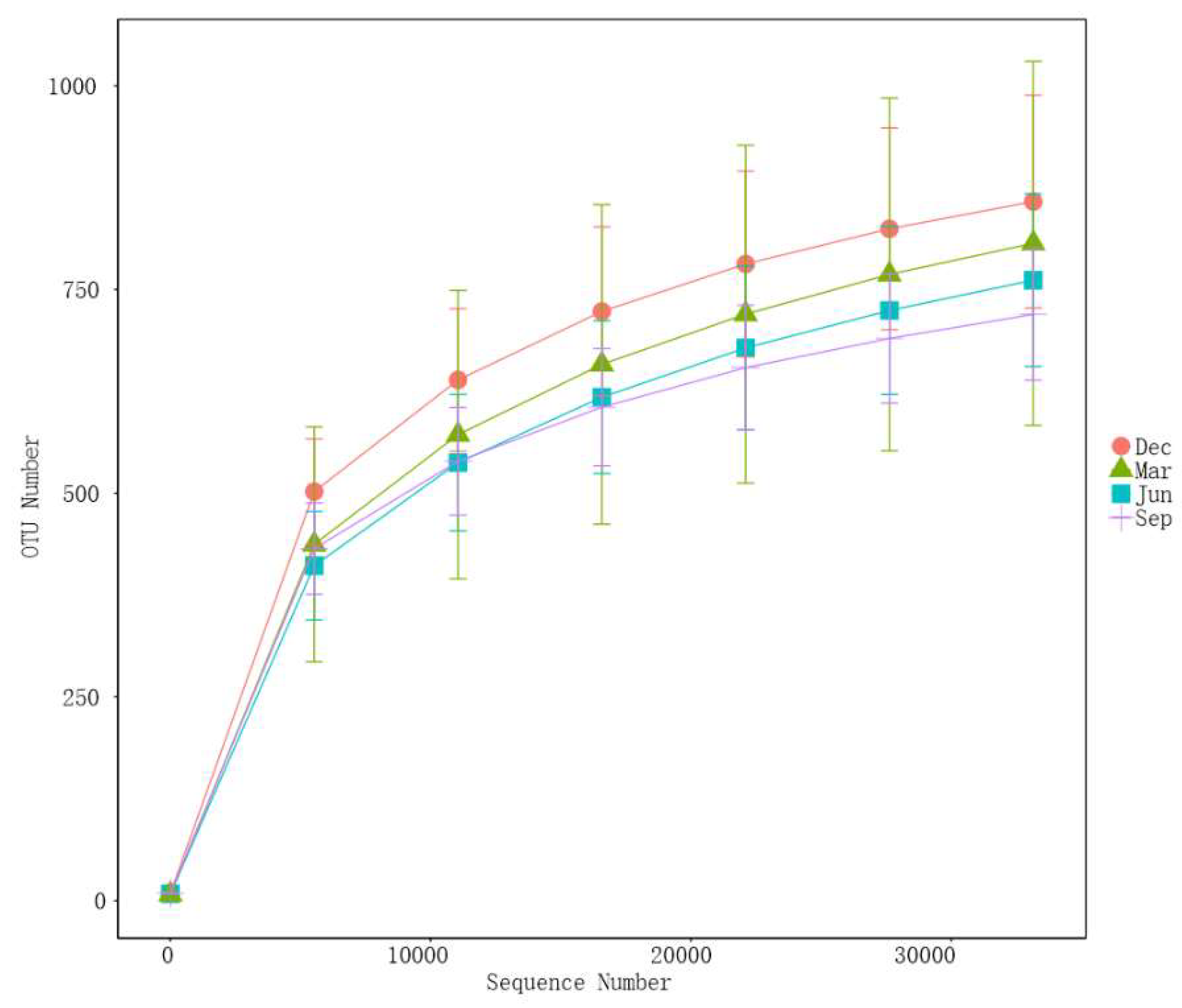

3.1. Assessment of Sequencing Data

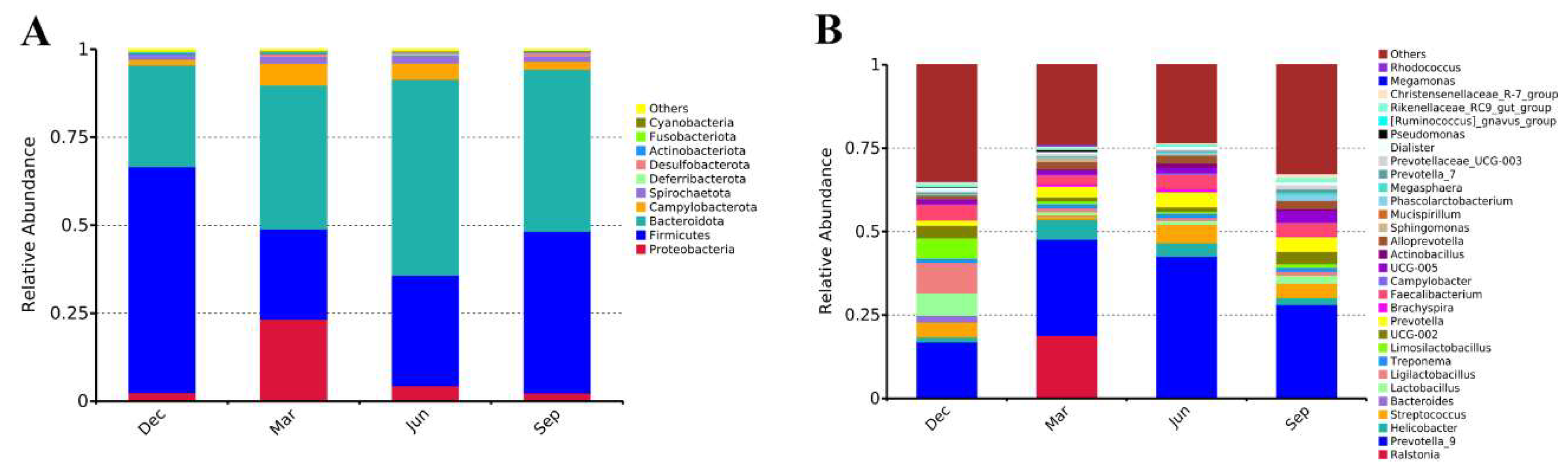

3.2. Gut Microbiota Composition in Adult Rhesus Macaques Across Seasons

3.3. Analysis of the Seasonal Differences in the Gut Microbiota

3.3.1. Seasonal Variation in Alpha Diversity

3.3.2. Seasonal Variations in Beta Diversity

3.3.3. Seasonal Variations in Microbial Communities

3.4. Analysis of Beneficial and Harmful Microorganisms

3.5. The effects of environmental factors on the seasonal variation in the gut microbiota of rhesus macaques

3.6. Seasonal Differences in Gut Microbial Functions

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shan, Y.; Lee, M.; Chang, E.B. The Gut Microbiome and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Annual Review of Medicine 2022, 73, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Yin, B.; Li, W.; Chai, T.; Liang, W.; Huang, Y.; Tan, X.; Zheng, P.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Age-related changes in microbial composition and function in cynomolgus macaques. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 12080–12096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Q.; He, X.; Zeng, B.; Meng, X.; Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Variation in Gut Microbiota of Captive Bengal Slow Lorises. Current Microbiology 2020, 77, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, S.; Yeoman, C.J.; Sipos, M.; Torralba, M.; Wilson, B.A.; Goldberg, T.L.; Stumpf, R.M.; Leigh, S.R.; White, B.A.; Nelson, K.E. Characterization of the Fecal Microbiome from Non-Human Wild Primates Reveals Species Specific Microbial Communities. Plos One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.-Z.; Li, X.-J.; Zhang, P.-W.; Chen, J.-X. A review of antibiotics, depression, and the gut microbiome. Psychiatry Research 2020, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochman, H.; Worobey, M.; Kuo, C.H.; Ndjango, J.B.; Peeters, M.; Hahn, B.H.; Hugenholtz, P. Evolutionary relationships of wild hominids recapitulated by gut microbial communities. PLoS Biol 2010, 8, e1000546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, K.R.; Leigh, S.R.; Kent, A.; Mackie, R.I.; Yeoman, C.J.; Stumpf, R.M.; Wilson, B.A.; Nelson, K.E.; White, B.A.; Garber, P.A. The gut microbiota appears to compensate for seasonal diet variation in the wild black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra). Microb Ecol 2015, 69, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, H.V.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R. Seasonal restructuring of the ground squirrel gut microbiota over the annual hibernation cycle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2013, 304, R33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkin, J.D.; Campos, F.A.; Myers, M.S.; Cheves Hernandez, S.E.; Guadamuz, A.; Melin, A.D. Seasonality of the gut microbiota of free-ranging white-faced capuchins in a tropical dry forest. Isme j 2019, 13, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, L.; Jia, S.; Tang, X.; Fu, H.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Y. Seasonal variations in the composition and functional profiles of gut microbiota reflect dietary changes in plateau pikas. Integr Zool 2022, 17, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajni, E.; Goel, P.; Sarna, M.K.; Jorwal, A.; Sharma, C.; Rijhwani, P. The genus Ralstonia: The new kid on the block. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2023, 53, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Gao, H.; Qin, W.; Song, P.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T. Marked Seasonal Variation in Structure and Function of Gut Microbiota in Forest and Alpine Musk Deer. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 699797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, C.; Ottem, K.F.; Brevik Ø, J.; Davey, M.; Sørum, H.; Winther-Larsen, H.C. The environmental and host-associated bacterial microbiota of Arctic seawater-farmed Atlantic salmon with ulcerative disorders. J Fish Dis 2017, 40, 1645–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Q.; Hu, Z.F.; Du, X.P.; Bie, J.; Wang, H.B. Effects of Seasonal Hibernation on the Similarities Between the Skin Microbiota and Gut Microbiota of an Amphibian (Rana dybowskii). Microb Ecol 2020, 79, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesnerova, L.; Emery, O.; Troilo, M.; Liberti, J.; Erkosar, B.; Engel, P. Gut microbiota structure differs between honeybees in winter and summer. Isme Journal 2020, 14, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Mishra, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Ning, R.; Kong, F.; Zeng, B.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. Comparative Study of Gut Microbiota in Wild and Captive Giant Pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestion, E.; Jacob, S.; Zinger, L.; Di Gesu, L.; Richard, M.; White, J.; Cote, J. Climate warming reduces gut microbiota diversity in a vertebrate ectotherm. Nat Ecol Evol 2017, 1, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, J.A.; Margesin, R. Seasonal soil microbial responses are limited to changes in functionality at two Alpine forest sites differing in altitude and vegetation. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Nong, D.; Li, Y.; Huang, Z. Evaluation of Gut Microbiota Stability and Flexibility as a Response to Seasonal Variation in the Wild François' Langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) in Limestone Forest. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e0509122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, A.; He, X.; McNiven, E.M.; Hinde, K.; Haggarty, N.W.; Lönnerdal, B.; Slupsky, C.M. Metabolomic phenotyping validates the infant rhesus monkey as a model of human infant metabolism. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013, 56, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Yang, F.; Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Jin, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, F.; et al. Composition of the intestinal microbiota of infant rhesus macaques at different ages before and after weaning. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.T.; Coe, C.L. Intestinal microbial patterns of the common marmoset and rhesus macaque. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2002, 133, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baniel, A.; Amato, K.R.; Beehner, J.C.; Bergman, T.J.; Mercer, A.; Perlman, R.F.; Petrullo, L.; Reitsema, L.; Sams, S.; Lu, A.; et al. Seasonal shifts in the gut microbiome indicate plastic responses to diet in wild geladas. Microbiome 2021, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breed, M.W.; Perez, H.L.; Otto, M.; Villaruz, A.E.; Weese, J.S.; Alvord, G.W.; Donohue, D.E.; Washington, F.; Kramer, J.A. Bacterial Genotype, Carrier Risk Factors, and an Antimicrobial Stewardship Approach Relevant To Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Prevalence in a Population of Macaques Housed in a Research Facility. Comp Med 2023, 73, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Subramanian, S.; Faith, J.J.; Gevers, D.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R.; Mills, D.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods 2013, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, G.; Shafer, A.B.A.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lin, S.; Wu, H.; Zhou, M.; Hu, D.; Liu, S. Comparative Analysis of the Gut Microbial Communities in Forest and Alpine Musk Deer Using High-Throughput Sequencing. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Ma, T.; Tang, W.; Li, D.; Mishra, S.K.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Jie, H. Gut Microbiome of Chinese Forest Musk Deer Examined across Gender and Age. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019, 9291216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, P.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y. Bacterial community diversity associated with different levels of dietary nutrition in the rumen of sheep. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2017, 101, 3717–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yang, C.; Guan, L.L.; Wang, J.; Xue, M.; Liu, J.X. Persistence of Cellulolytic Bacteria Fibrobacter and Treponema After Short-Term Corn Stover-Based Dietary Intervention Reveals the Potential to Improve Rumen Fibrolytic Function. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Rios-Covian, D.; Huillet, E.; Auger, S.; Khazaal, S.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Sokol, H.; Chatel, J.M.; Langella, P. Faecalibacterium: a bacterial genus with promising human health applications. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matulova, M.; Nouaille, R.; Capek, P.; Péan, M.; Delort, A.M.; Forano, E. NMR study of cellulose and wheat straw degradation by Ruminococcus albus 20. Febs j 2008, 275, 3503–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Callaghan, J.; O'Toole, P.W. Lactobacillus: host-microbe relationships. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013, 358, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compo, N.R.; Mieles-Rodriguez, L.; Gomez, D.E. Fecal Bacterial Microbiota of Healthy Free-Ranging, Healthy Corralled, and Chronic Diarrheic Corralled Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta). Comp Med 2021, 71, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.F.; Wang, F.J.; Yu, L.; Ye, H.H.; Yang, G.B. Metagenomic comparison of the rectal microbiota between rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) and cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Zool Res 2019, 40, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, C.F.; Knowles, S.C.; Ladau, J.; Pollard, K.S.; Fenton, A.; Pedersen, A.B.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Marked seasonal variation in the wild mouse gut microbiota. Isme j 2015, 9, 2423–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trosvik, P.; de Muinck, E.J.; Rueness, E.K.; Fashing, P.J.; Beierschmitt, E.C.; Callingham, K.R.; Kraus, J.B.; Trew, T.H.; Moges, A.; Mekonnen, A.; et al. Multilevel social structure and diet shape the gut microbiota of the gelada monkey, the only grazing primate. Microbiome 2018, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Hou, R.; Zhang, M.; Fei, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Bridgewater, L.C.; Jiang, Y.; et al. The bamboo-eating giant panda harbors a carnivore-like gut microbiota, with excessive seasonal variations. mBio 2015, 6, e00022–00015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartzinel, T.R.; Hsing, J.C.; Musili, P.M.; Brown, B.R.P.; Pringle, R.M. Covariation of diet and gut microbiome in African megafauna. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 23588–23593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, M.A.; Acevedo-Whitehouse, K.; Morales-Durán, N.; Grosser, S.; Chakarov, N.; Krüger, O.; Nichols, H.J.; Elorriaga-Verplancken, F.R.; Hoffman, J.I. Early sexual dimorphism in the developing gut microbiome of northern elephant seals. Mol Ecol 2020, 29, 2109–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.B.; Firek, B.; Shi, M.; Yeh, A.; Brower-Sinning, R.; Aveson, V.; Kohl, B.L.; Fabio, A.; Carcillo, J.A.; Morowitz, M.J. Disruption of the microbiota across multiple body sites in critically ill children. Microbiome 2016, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Shang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Gut Microbiota in Dholes During Estrus. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 575731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Yun, T.T.; Qi, W.T.; Liang, X.X.; Wang, Y.W.; Li, A.K. Effects of pre-encapsulated and pro-encapsulated Enterococcus faecalis on growth performance, blood characteristics, and cecal microflora in broiler chickens. Poult Sci 2015, 94, 2821–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P.; Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R.D.; Gordon, J.I. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 11070–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licht, T.R.; Hansen, M.; Bergström, A.; Poulsen, M.; Krath, B.N.; Markowski, J.; Dragsted, L.O.; Wilcks, A. Effects of apples and specific apple components on the cecal environment of conventional rats: role of apple pectin. BMC Microbiol 2010, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsirma, Z.; Dimidi, E.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Whelan, K. Fruits and their impact on the gut microbiota, gut motility and constipation. Food Funct 2021, 12, 8850–8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, K.; Ohashi, Y.; Kawasumi, K.; Terada, A.; Fujisawa, T. Effect of apple intake on fecal microbiota and metabolites in humans. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H.; Branch, W.; Jenkins, D.J.; Southgate, D.A.; Houston, H.; James, W.P. Colonic response to dietary fibre from carrot, cabbage, apple, bran. Lancet 1978, 1, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rhesus Monkey Number | Age | Salmonella | Diarrhoea | Five-pathogens negative | Have not used any medication or probiotics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /Shigella | |||||

| 1 | 15 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | 15 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | 14 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | 13 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | 13 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | 11 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | 11 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | 11 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 20 | 12 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | 15 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | 15 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 23 | 11 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | 11 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 26 | 10 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 27 | 12 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 28 | 12 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 29 | 12 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| 30 | 12 | Negative | No | Yes | Yes |

| R-value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| December versus June | 0.806 | 0.001 |

| December versus September | 0.5652 | 0.001 |

| March versus December | 0.5899 | 0.001 |

| March versus September | 0.2947 | 0.001 |

| March versus June | 0.2035 | 0.001 |

| June versus September | 0.3278 | 0.001 |

| December (%) | March (%) | June (%) | September (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia-Shigella | 17/30 (56.67) | 13/30 (43.33) | 8/30 (26.67)# | 7/30 (23.33)# |

| Pseudomonas | 30/30 (100) | 24/30 (80)‡ | 3/30 (10)+$ | 2/30 (6.67)+$ |

| Campylobacter | 30/30 (100) | 27/30 (90) | 28/30 (93.33) | 23/30 (76.67)& |

| Vibrio | 2/30 (6.67) | 9/30 (30) | 0/30 (0) | 1/30 (3.33) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).