1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to develop and propose a method to convert 10–min rain–rate time series into 1–min rain–rate time series, the latter to be afterwards used, in the paper, as input to the Synthetic Storm Technique (SST) for simulating rain–attenuation time series [

1], a very reliable tool that can even reconstruct missing intervals in time series [

2]. The rationale for the need of such a method lies in the fact that several meteorological institues make available time series of quantity of water accumulated every 10 minutes (therefore providing 10–min rain–rate time series), compared to the past when, at most, the quantity of water collected referred from 1 day to 1 hour. Our previous theory on the de–integration of the accumulated rainfall – from 1 day to 1 hour water – refers only to the probability distributions of rain–rate [

3,

4].

To develop the method, we use a very large data bank of 1–min rain–rate time series collected in Spino d’Adda (

Table 1), from 1993 to 2002, 10 years of practically all rain events occurred in the period. First, we convert them to 10–min rain–rate time series for obtaining the measured data bank allegedly provided by some Meteorological Institutes, and then we develop the method that can simulate 1–min rain–rate time series. The comparison between the experimental and simulated 1–min time series will provide how good and precise the method is. The conversion method is then studied and developed for the other sites listed in

Table 1, to assess whether it works well also in different climatic regions.

The sites listed in

Table 1 are useful study–cases because: (a) on–site 1–min rain–rate time series were continuously recorded for several years; (b) in these sites are located important NASA and ESA satellite ground stations (Gera Lario, Fucino, Madrid, White Sands); (c) long–term radio propagation experiments were performed (Fucino, Gera Lario, Spino d’Adda, Madrid, Prague, White Sands); (d) there are important cities (Madrid, Prague, Tampa, Vancouver).

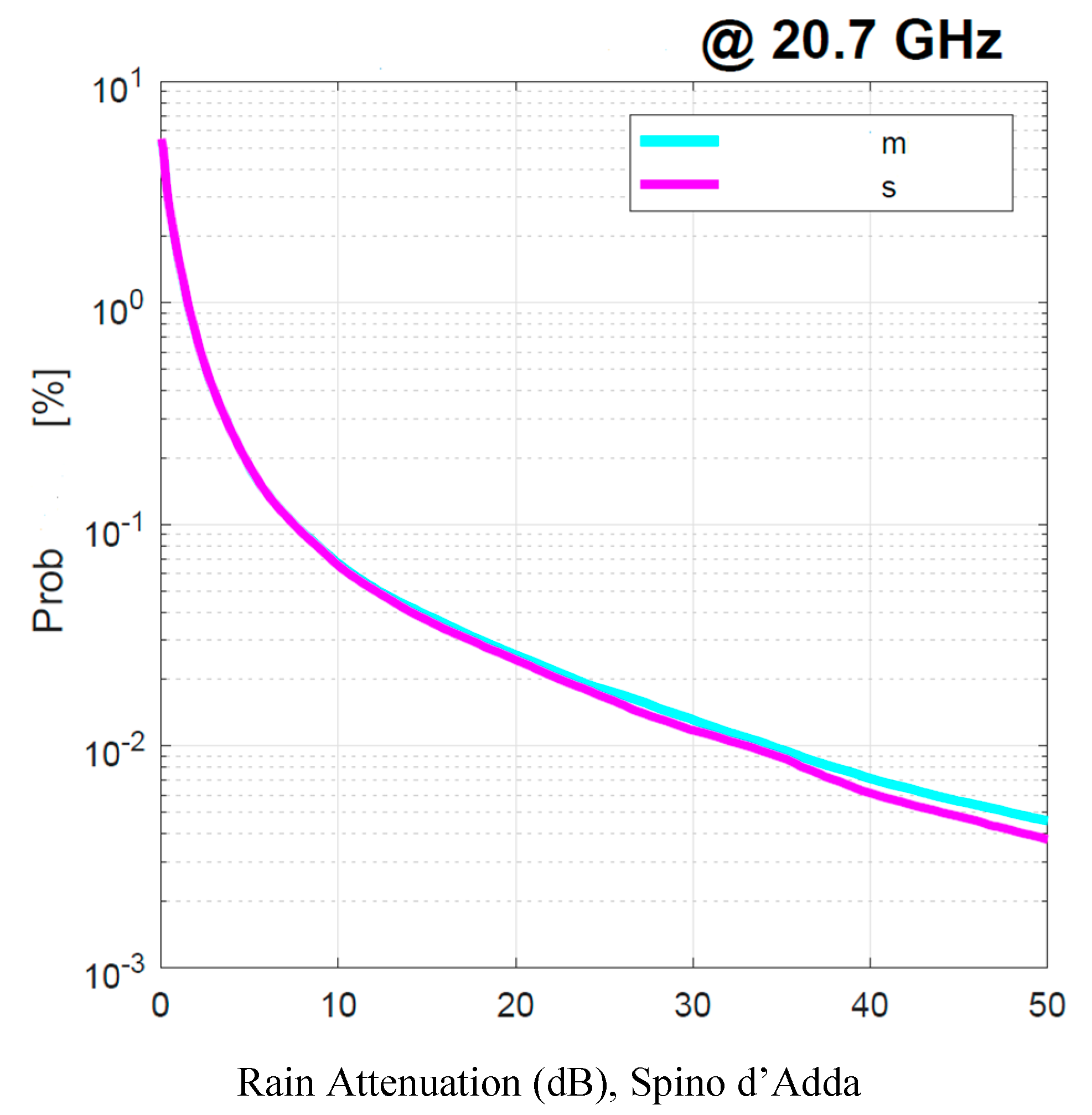

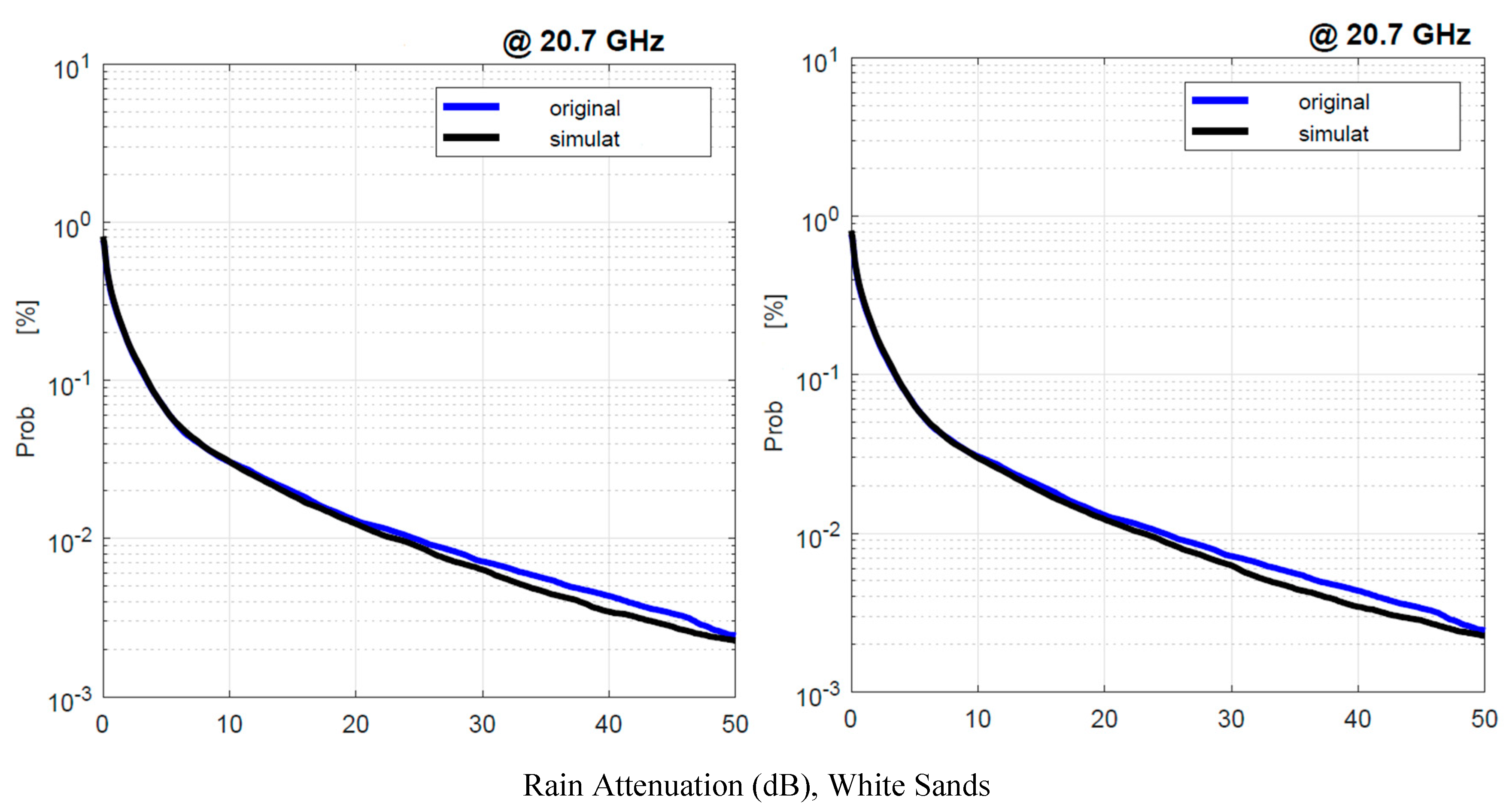

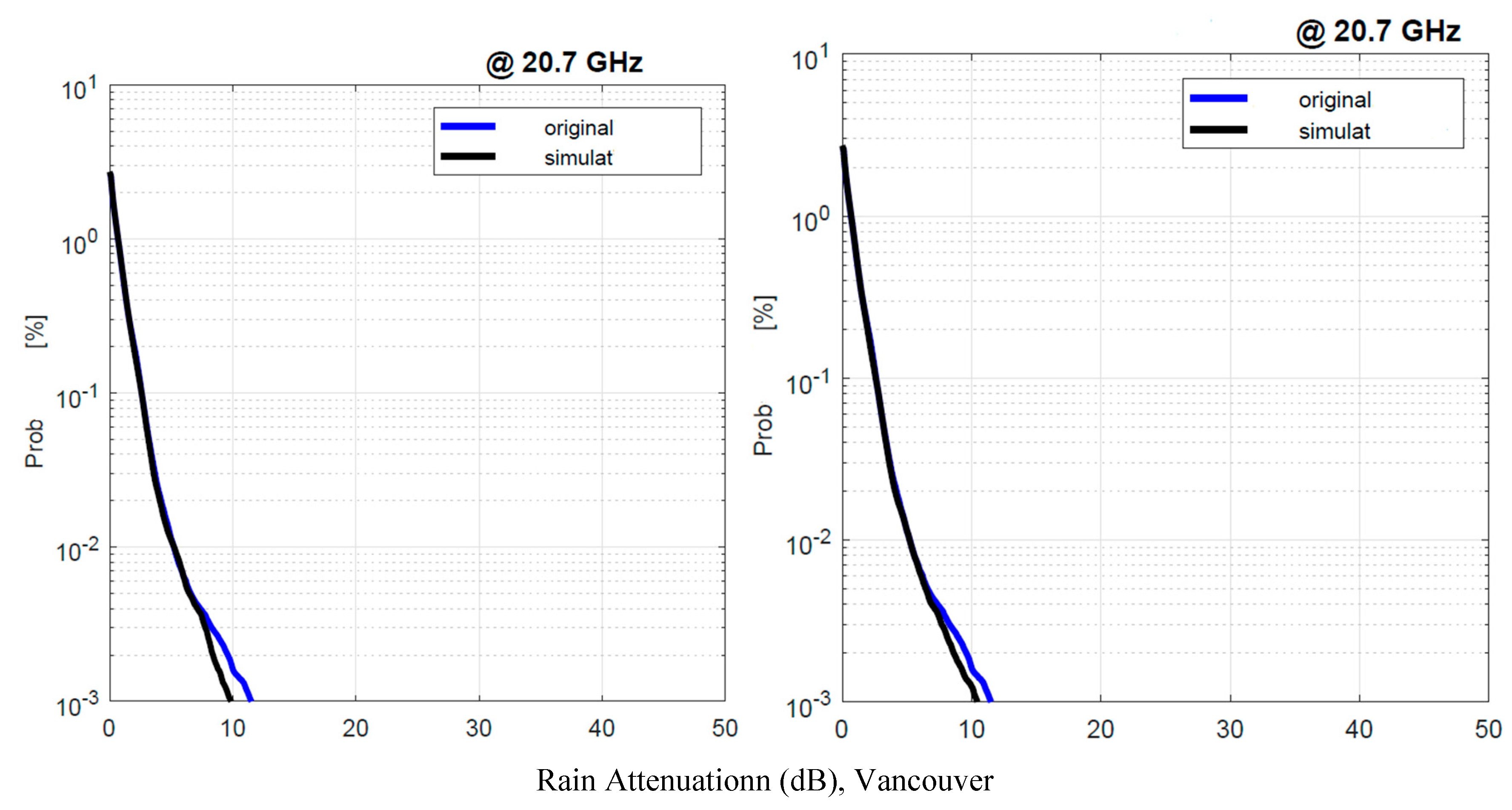

Afterwards, we use the two sets of 1–min rain–rate time series (i.e., that measured and that simulated from 10–min rain–rate time series) as the input to the SST for simulating – as example of application – rain attenuation time series at 20.7 GHz in 35.5° slant paths to geostationary satellites at the sites of

Table 1. The conclusion of our exercise is that the two rain attenuation probability distributions in an average year show no significant differences that can affect satellite systems design at centimeter or millimeter frequencies, so that the method can be used very reliably for this purpose.

The theory, however, can be potentially useful not only in satellite communications and radio propagation studies, but also in other fields. In agriculture, for example, the measured daily rainfall needs to be disaggregated to predict runoff, erosion and pollutant transport [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In hydrology, the kinetic energy determines the potential ability of the rainfall to detach soil and it is used as a rain erosivity index [

6]. Kinetic energy is strictly linked to the rain rate, therefore data of instantaneous rain rate (as 1–min rain rate times series can be considered) could improve the estimates in these fields.

After this introductory section, in

Section 2 we study the 1–min and 10–min rain–rate data bank of Spino d’Adda, our “laboratory” site; in

Section 3 we develop the method to convert

into 1-min rain rate time series, termed

in Spino d’Adda; in

Section 4 we develop and confirm the method for the other sites of

Table 1; in

Section 5 we recall the theory of the Synthetic Storm Technique and report its application to the sites of

Table 1; in Section 6 we draw a conclusion.

2. Exploratory Data Analysis in Spino d’Adda

In this Section we use the 10–year 1–min rain rate data bank collected in Spino d’Adda, our “laboratoty” site, to study how the experimental 1–min rain–rate time series

(mm/h) are connected with the corresponding 10–min time series

(mm/h). The latter is generated by

, according to the following relationhsip, applied to disjoint and contiguous 10–min intervals during the rainfall event:

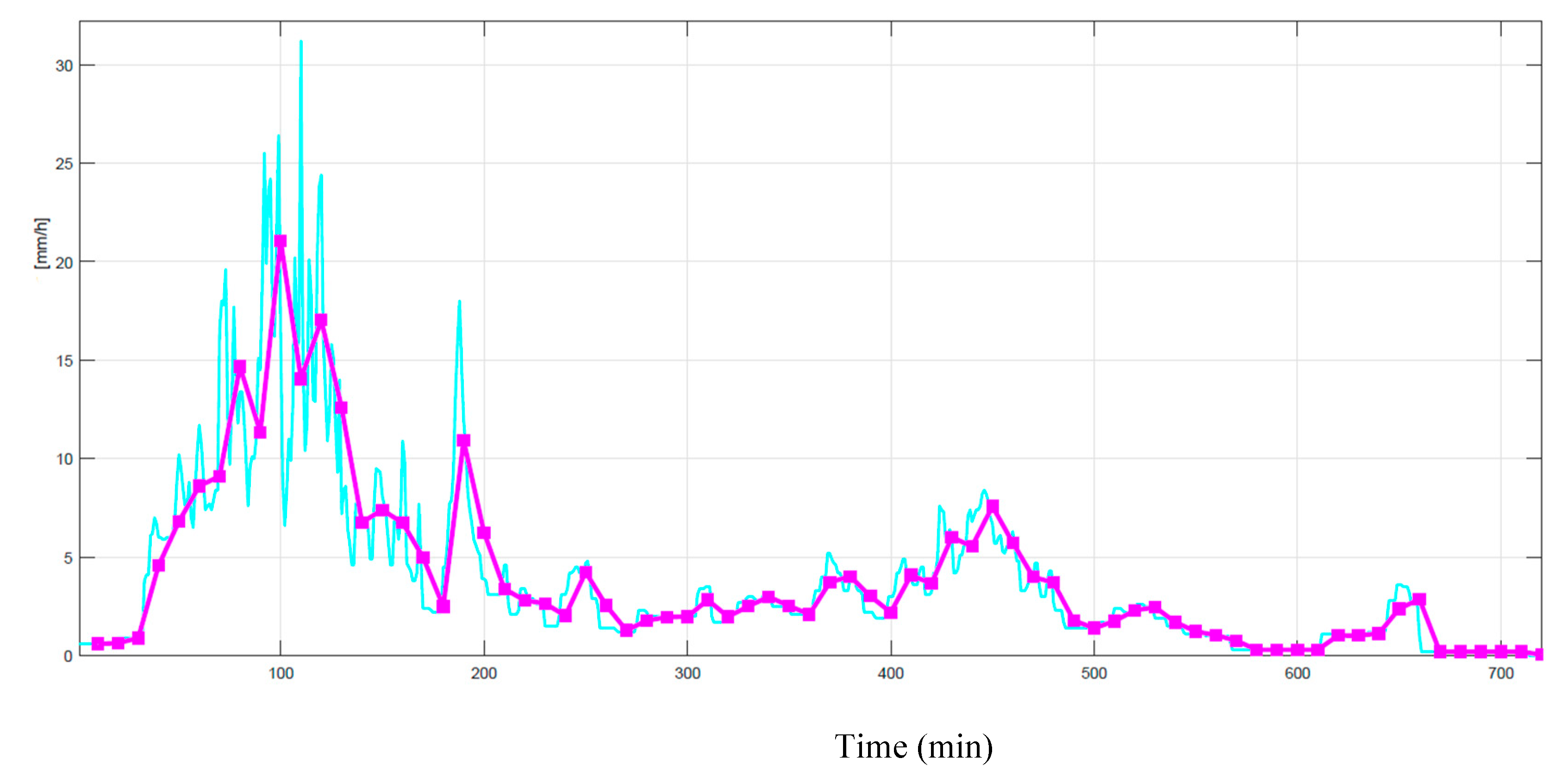

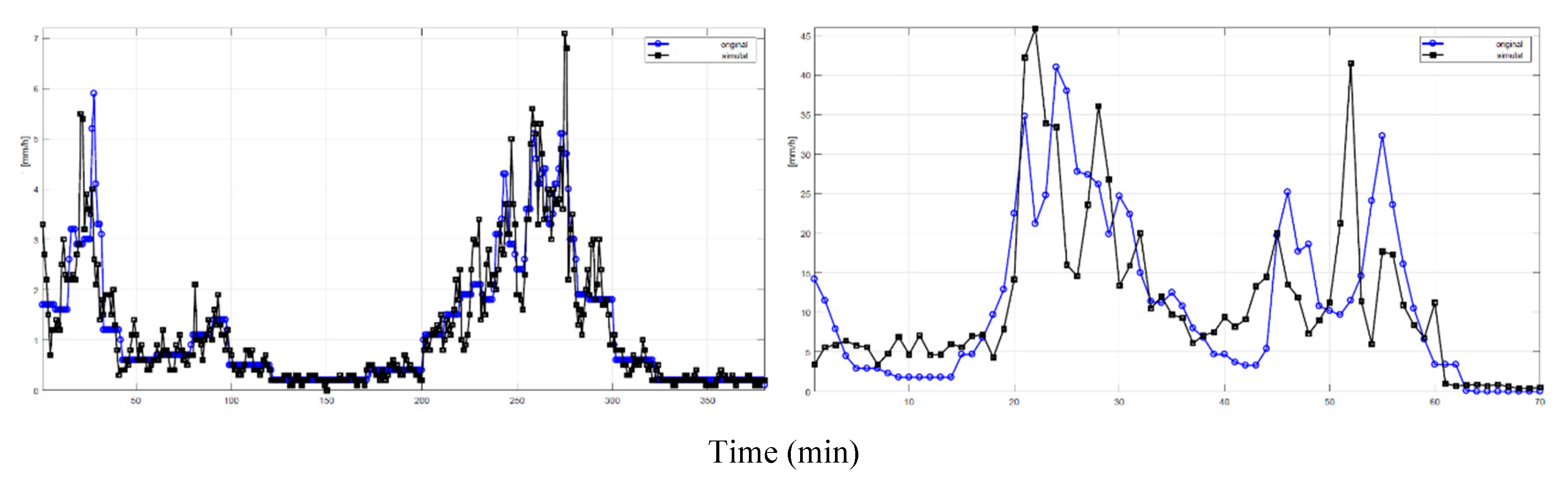

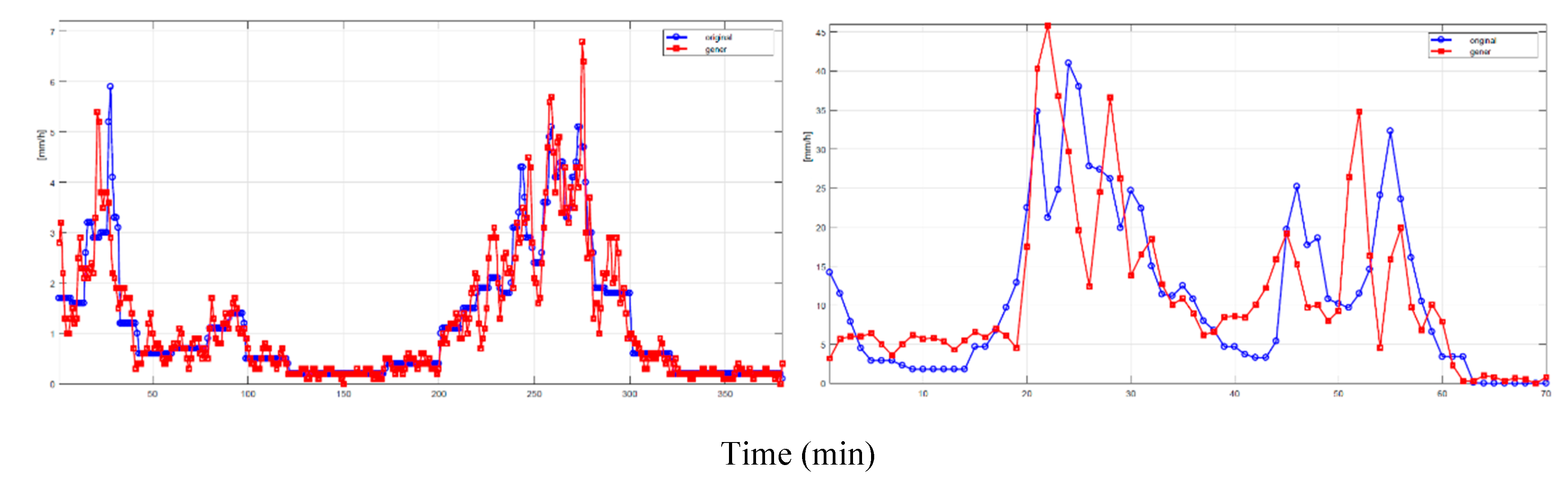

Figure 1 shows an example of this linear tranformation. We notice, of course, that

is smoothed, therefore any application using

will underestimate the effect of the “instantaneous” largest rain rates whose intensity can be significantly reduced.

Since we transform

(mm/h) into an estimated/simulated

, the first step is to study the distribution of

within intervals of 10 min conditioned to

. These conditional distribution will be useful to simulate

from

. This is possible because, as shown in the example of

Figure 1, both

, and

are available for Spino d’Adda and the other sites listed in

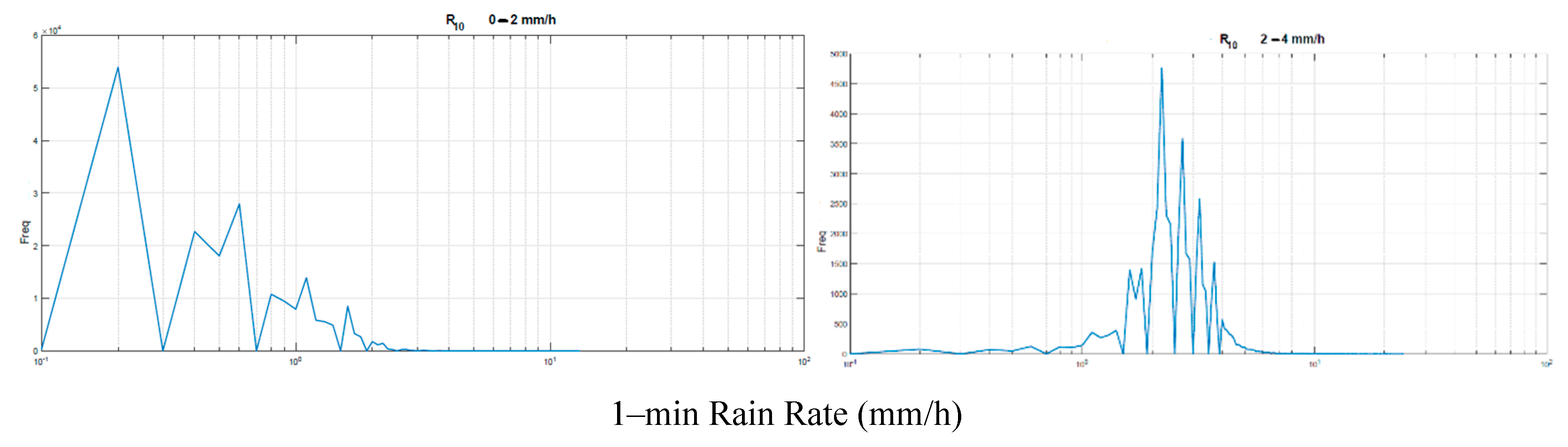

Table 1, for several years. By considering the full data bank of similar results, we have therefore calculated the conditional histograms of

within 10–min intervals, in the following ranges of

: 0–2, 2–4, 4–6, 6–8, 8–10, 10–15, 15–20, 20–30, 30–40, > 40 mm/h (samples with range maximum value are included in that range). Notice that the first range starts at 0.2 mm/h because of rain–gauge technology.

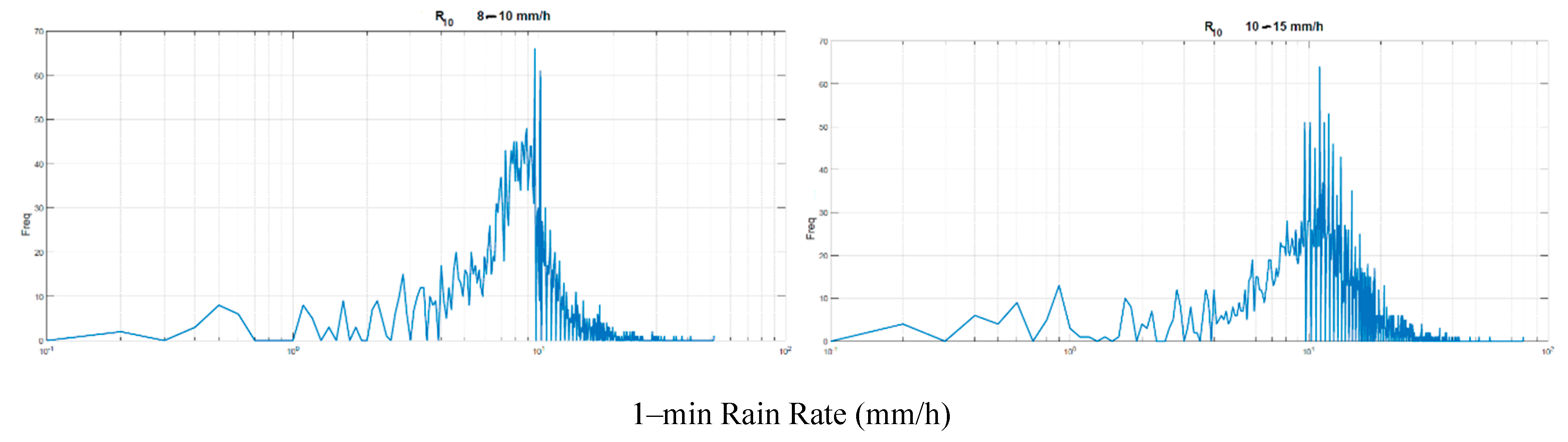

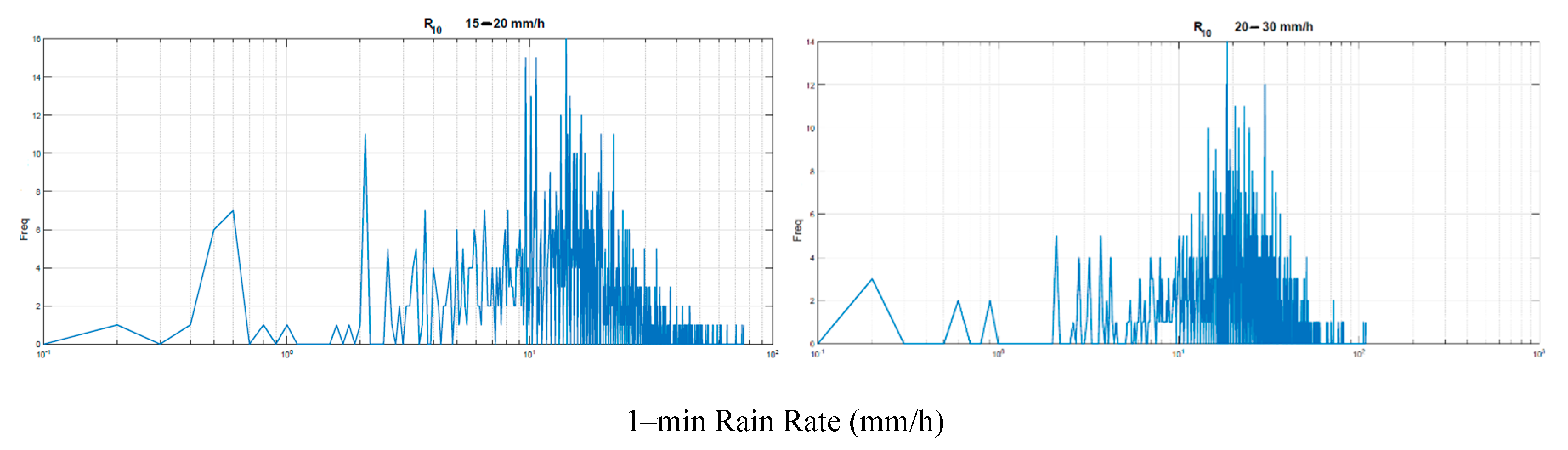

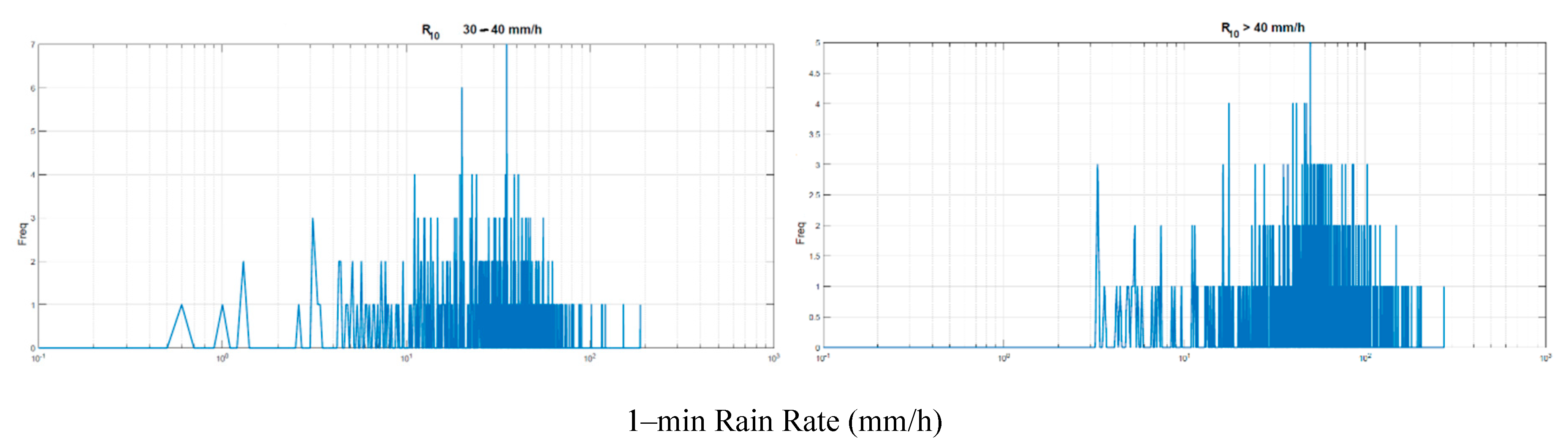

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show these histograms.

From these figures we assume that a log–normal probability density function (PDF) can adequately model the central part of the experimental histograms, therefore we have calculated mean value and standard deviation of

– natural logarithm – and assumed a log–normal probability PDF chacterized by the values reported in Table 2, together with the correlation coefficient between two successive

samples within the same 10–min interval. These parameters are fundamental because they will be used in

Section 3 to simulate

from

.

Table 1.

Mean value, standard deviation of and correlation coefficient between two successive samples within the same 10–min interval, for the indicated ranges. The first range starts at 0.2 mm/h.

Table 1.

Mean value, standard deviation of and correlation coefficient between two successive samples within the same 10–min interval, for the indicated ranges. The first range starts at 0.2 mm/h.

|

(mm/h) |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Correlation Coefficient |

| 0–2 |

–0.60 |

0.75 |

0.94 |

| 2–4 |

0.94 |

0.37 |

0.76 |

| 4–6 |

1.51 |

0.41 |

0.70 |

| 6–8 |

1.83 |

0.49 |

0.72 |

| 8–10 |

2.07 |

0.52 |

0.68 |

| 10–15 |

2.35 |

0.61 |

0.72 |

| 15–20 |

2.62 |

0.76 |

0.71 |

| 20–30 |

3.03 |

0.68 |

0.70 |

| 30–40 |

3.32 |

0.77 |

0.75 |

| > 40 |

3.95 |

0.72 |

0.76 |

4. From to in Other Sites

In this section we apply the method obtained in our “laboratory” of Spino d’Adda at the sites reported in

Table 1, for which 1–min rate times series are available for many years. First, in

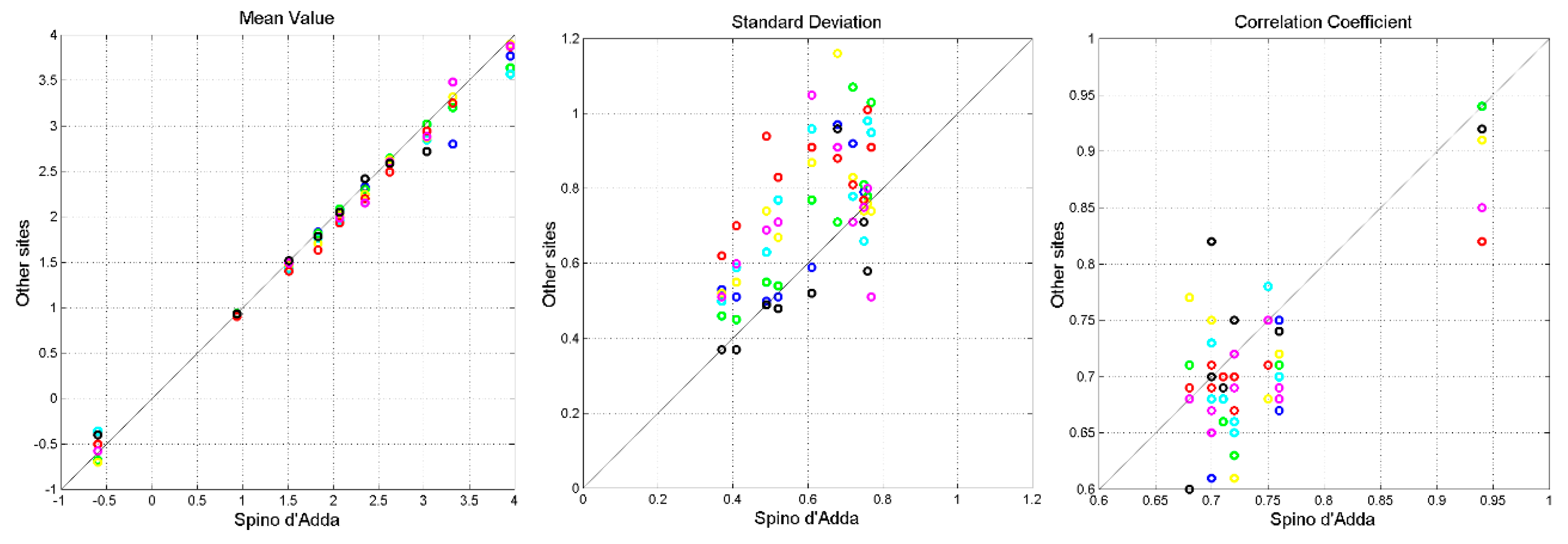

Figure 11, we show the scatterplots between mean values, standard deviations and correlation cofficients of Spino d’Adda (the values of Table 2) versus those of the othe sites of

Table 1 (

Appendix B reports the numerical values). We can see a very tight relationship between the mean values. This means that the rain rate process, although in sites with different weather and rainfall intensity, can be modelled with log–normal PDFs with the same mean value. Differences arise in the standard deviation and correlation coefficient, although these differences do not impact significantly on the simulation predictions as we show next.

Figure 11.

Scatterplots of mean values (left panel), standard deviations (central panel) and correlation coefficients (right panel) between the values of the sites of

Table 1 and Spino d’Adda. Gera Lario: green; Fucino: blue; Madrid: cyan; Prague: yellow; Tampa: red; White Sands: magenta; Vancouver: black.

Figure 11.

Scatterplots of mean values (left panel), standard deviations (central panel) and correlation coefficients (right panel) between the values of the sites of

Table 1 and Spino d’Adda. Gera Lario: green; Fucino: blue; Madrid: cyan; Prague: yellow; Tampa: red; White Sands: magenta; Vancouver: black.

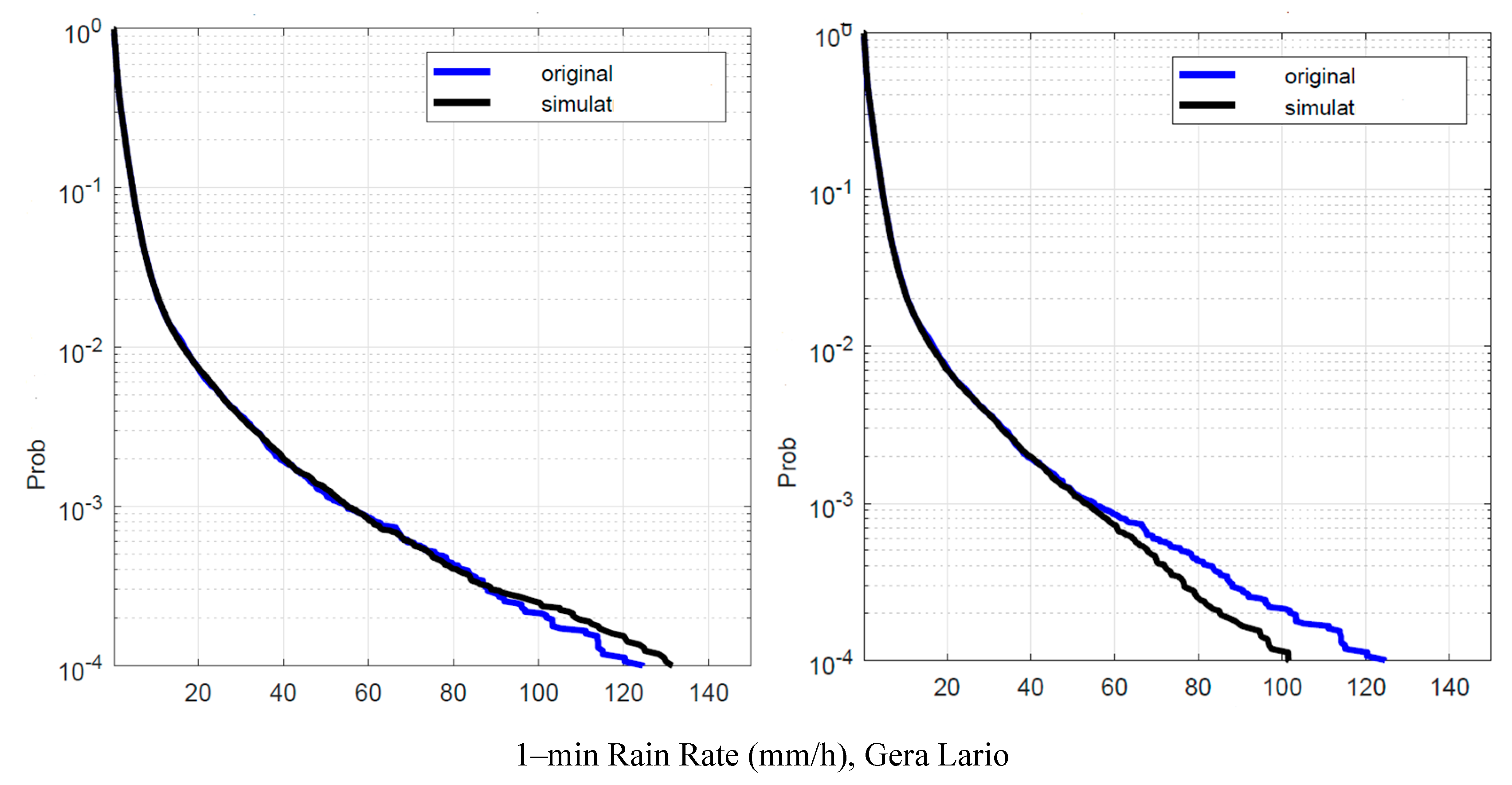

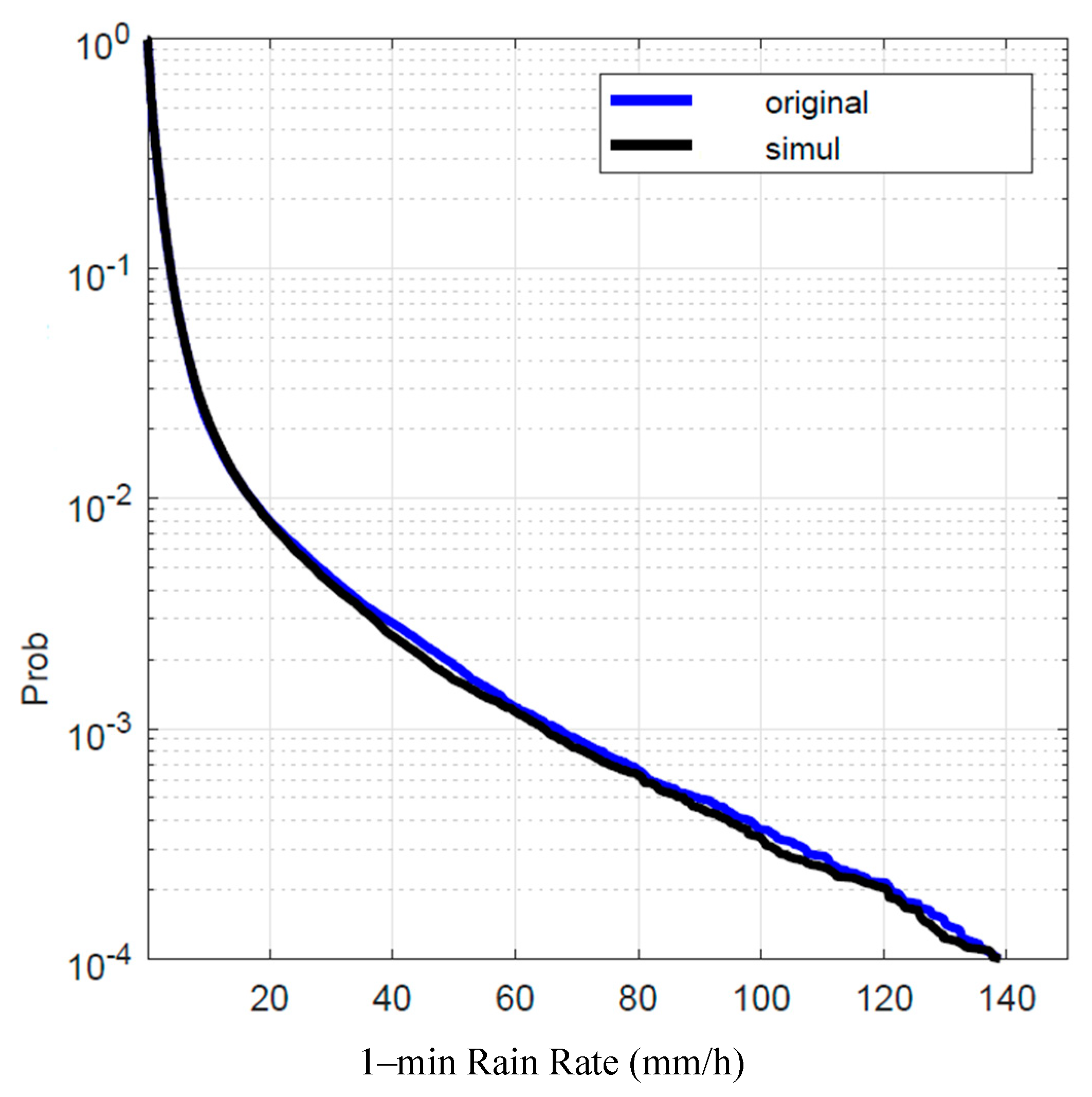

Figure 12.

Gera Lario. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 12.

Gera Lario. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

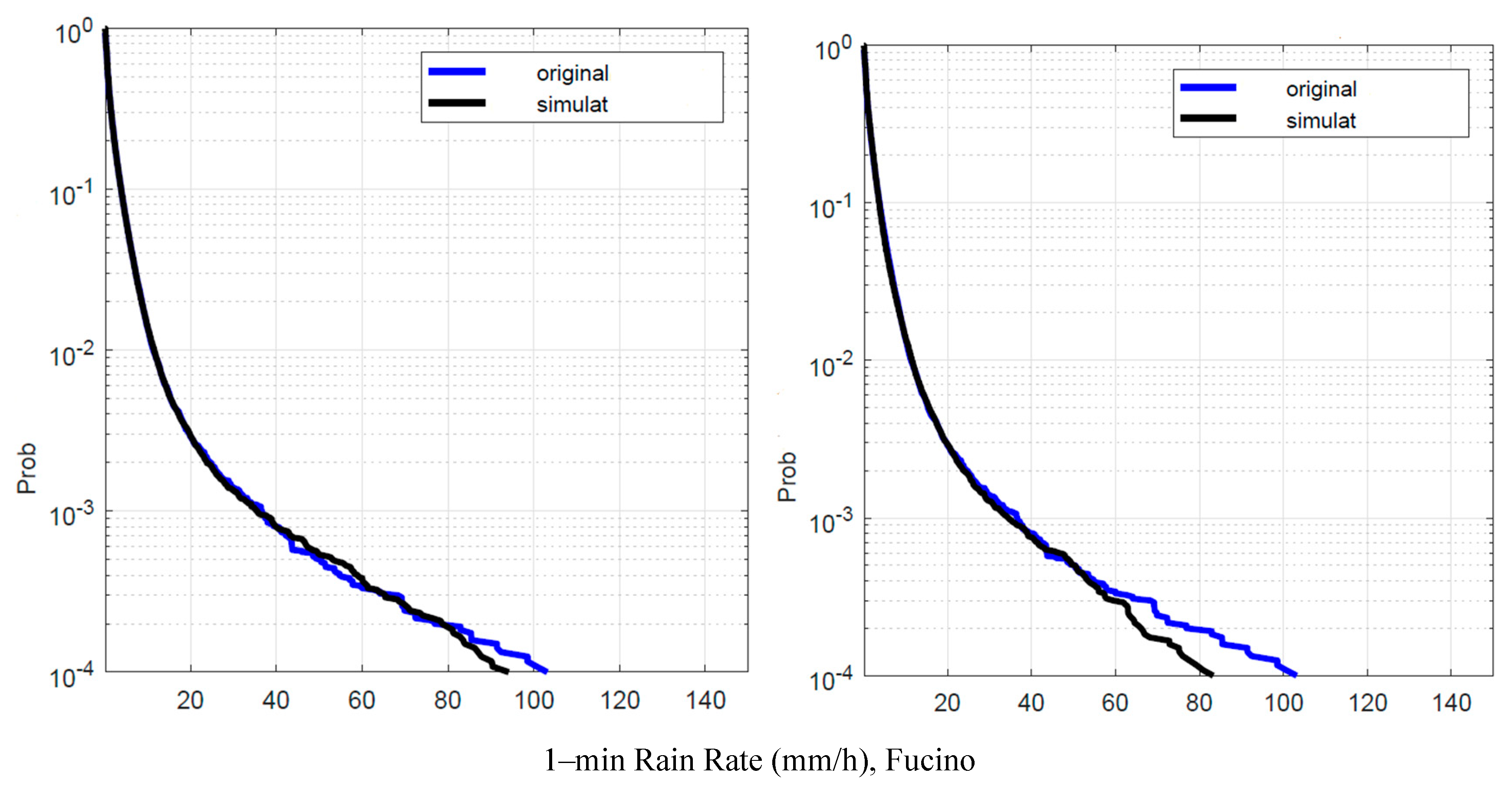

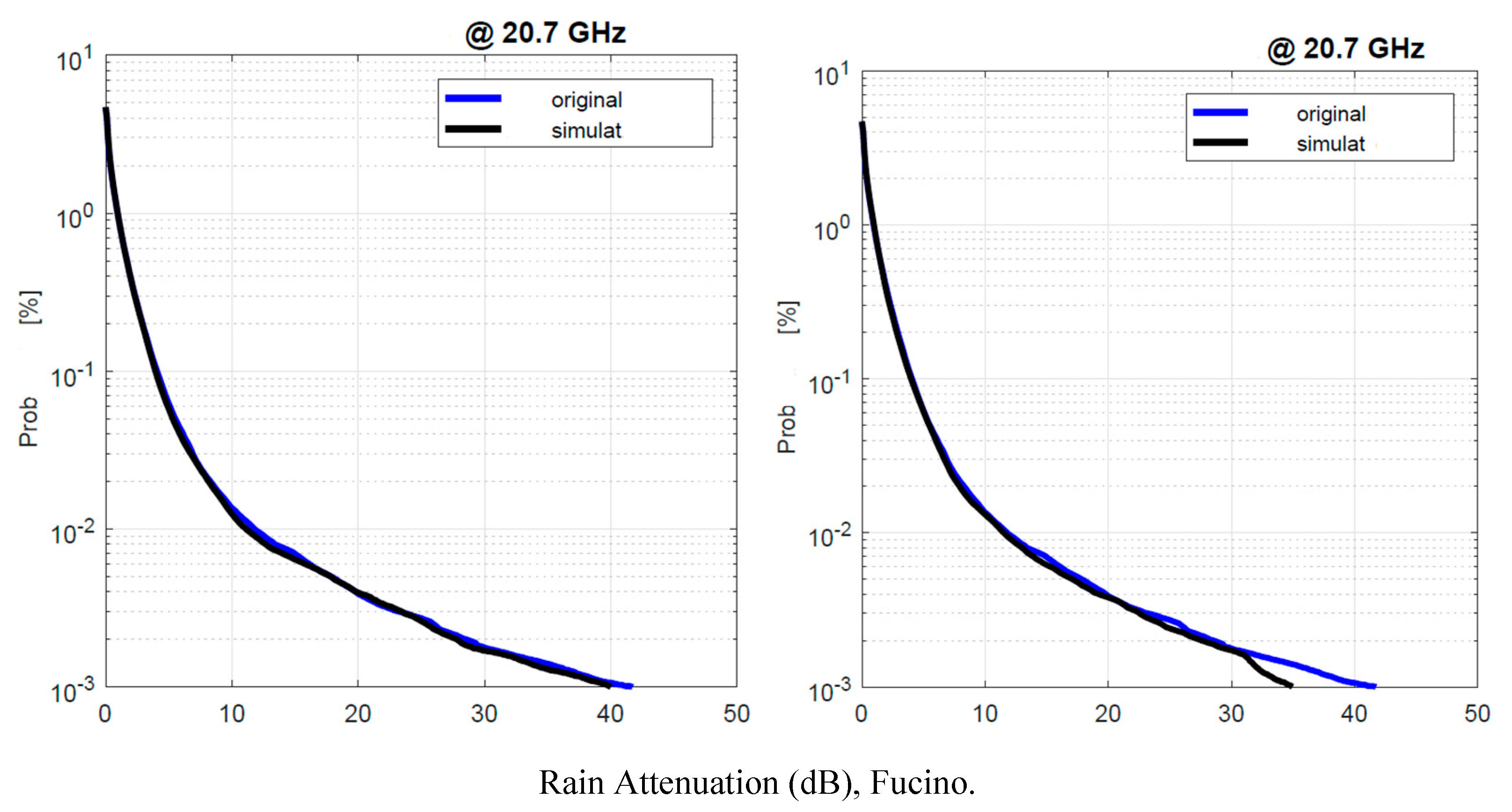

Figure 13.

Fucino. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 13.

Fucino. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

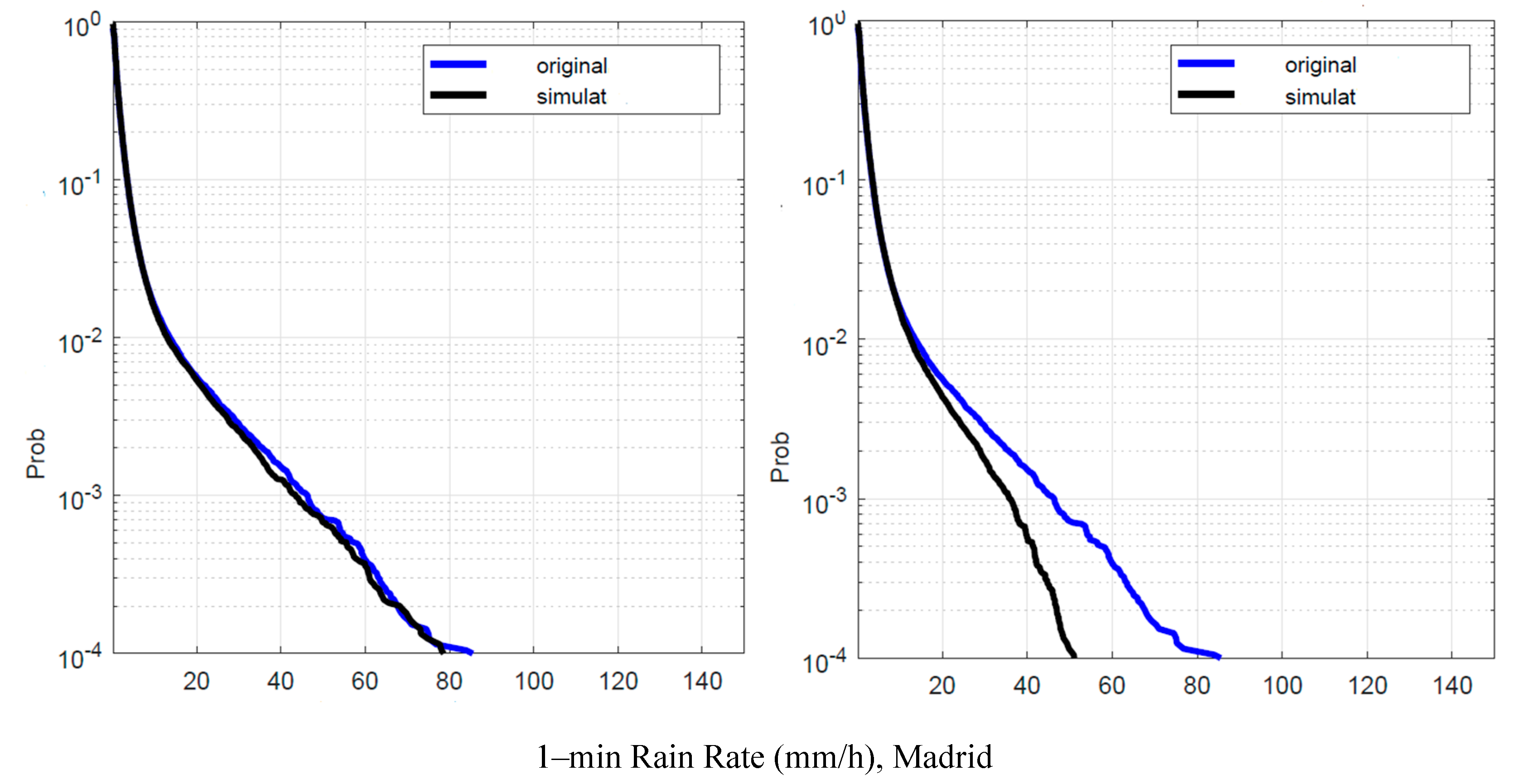

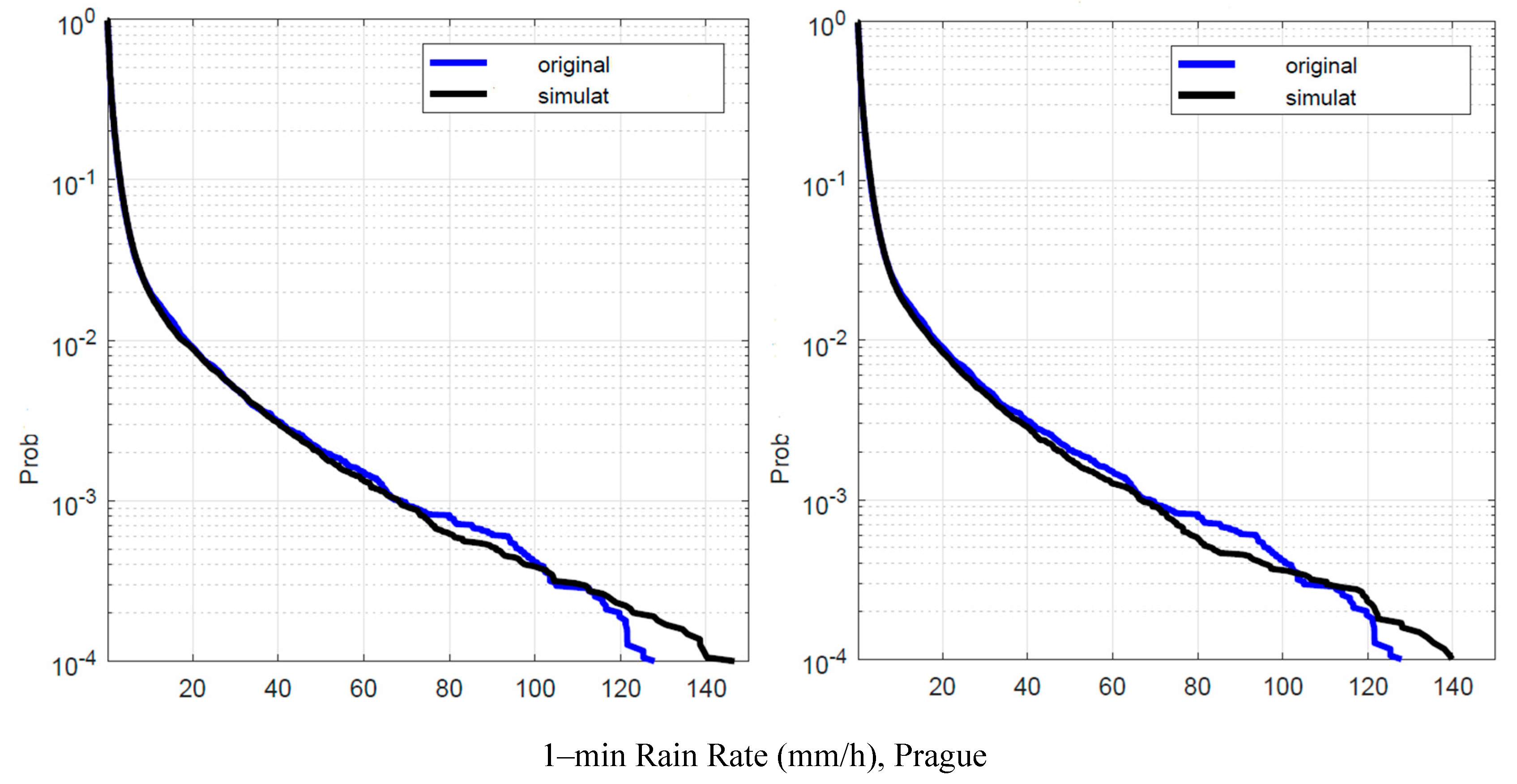

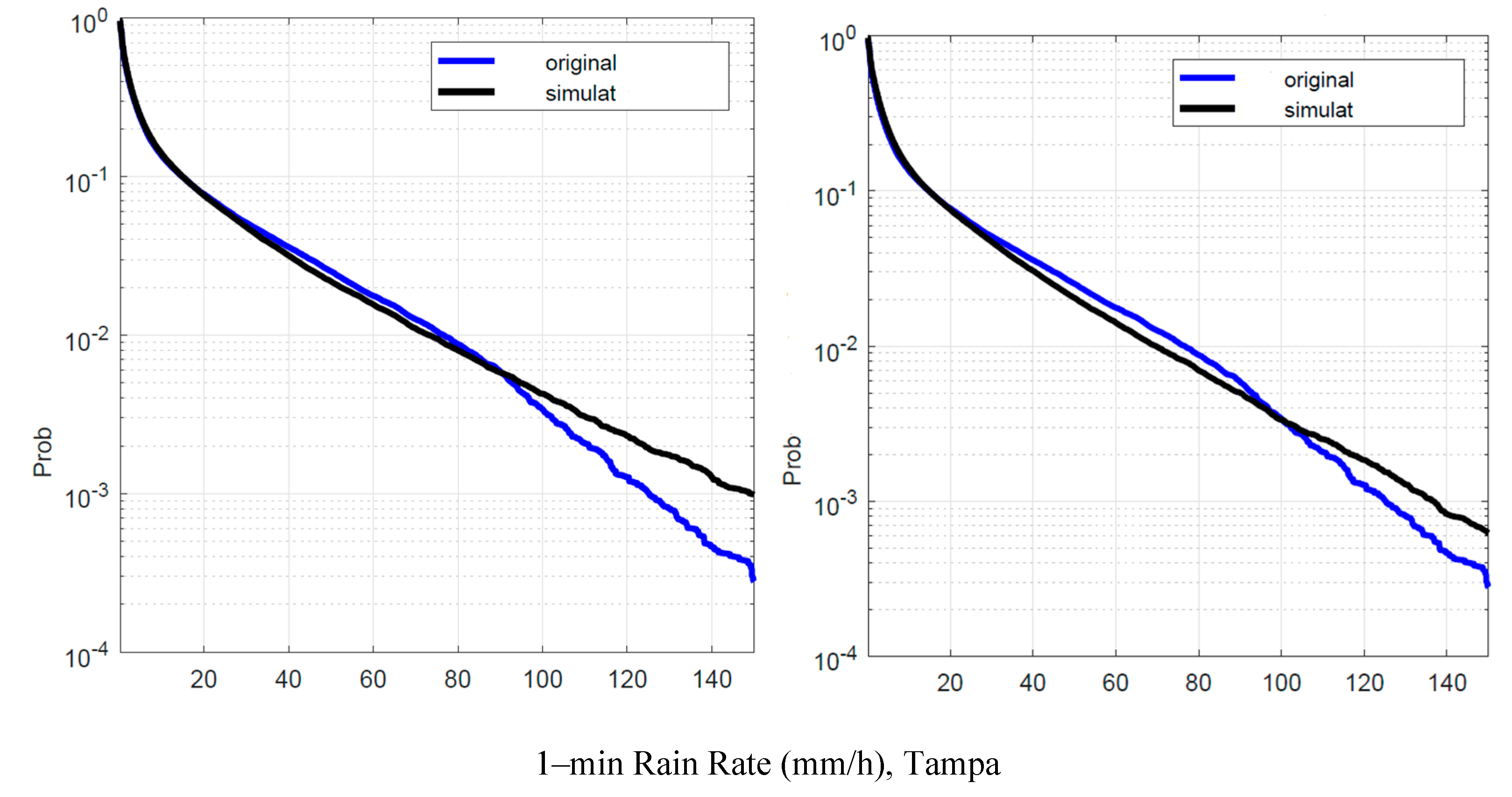

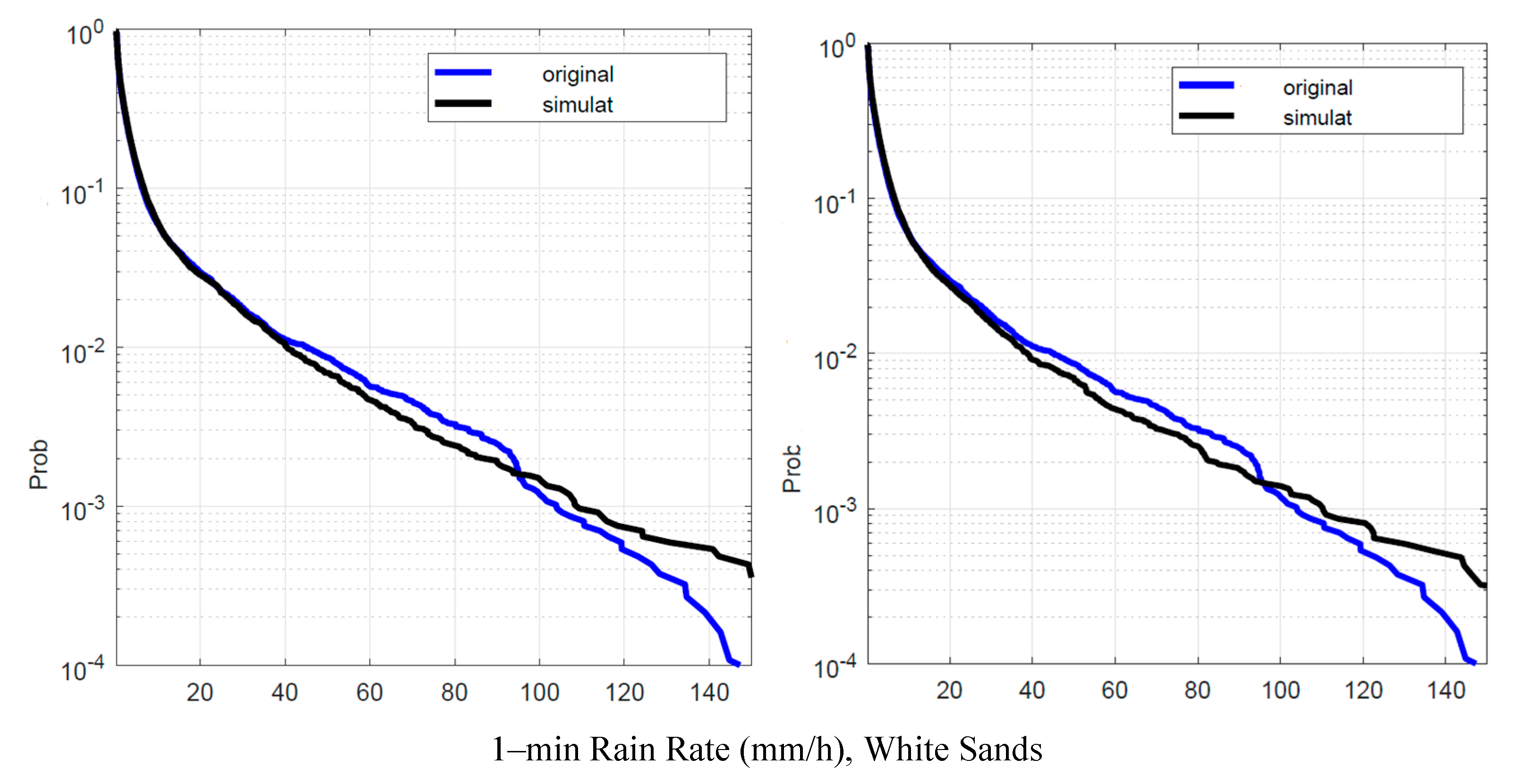

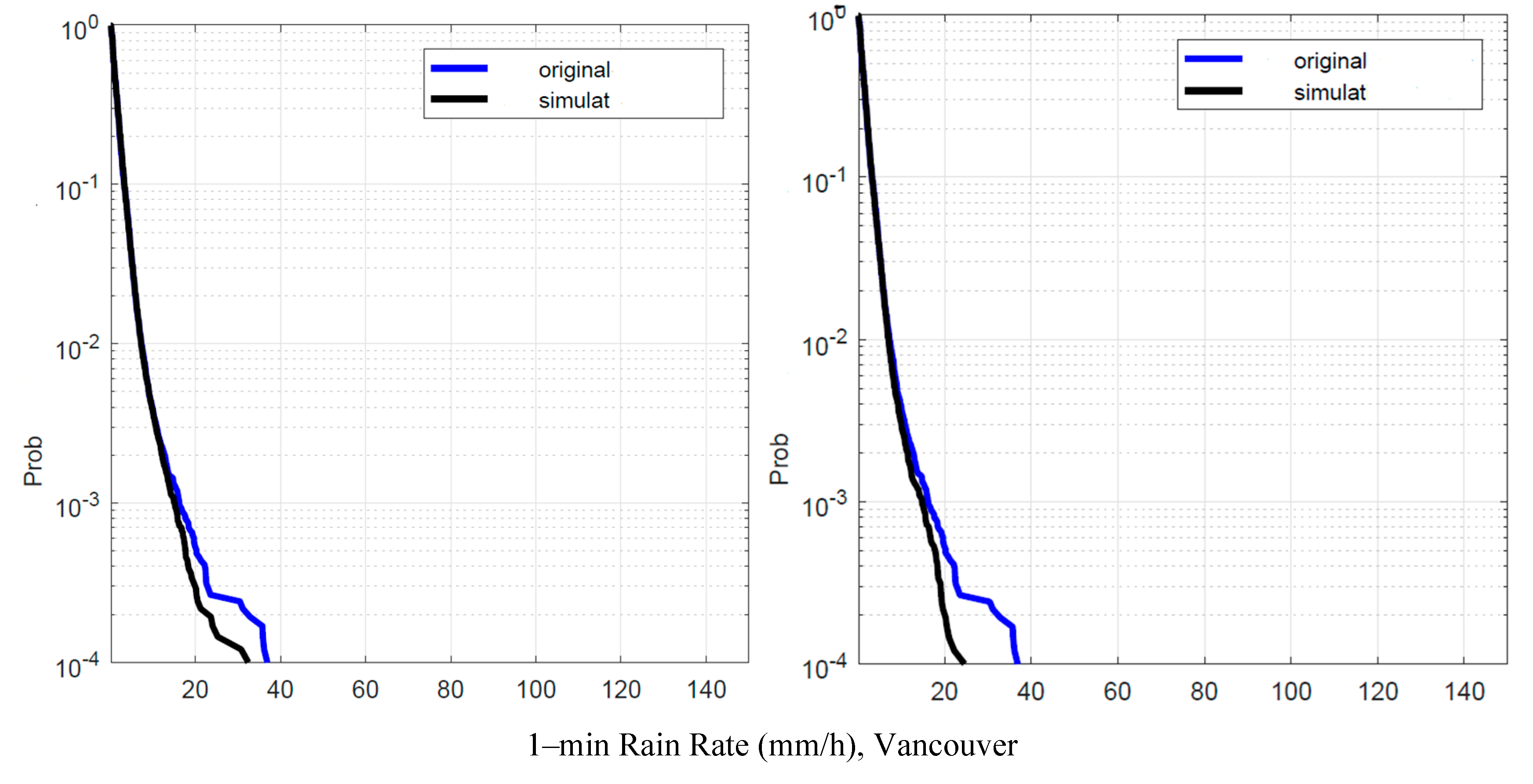

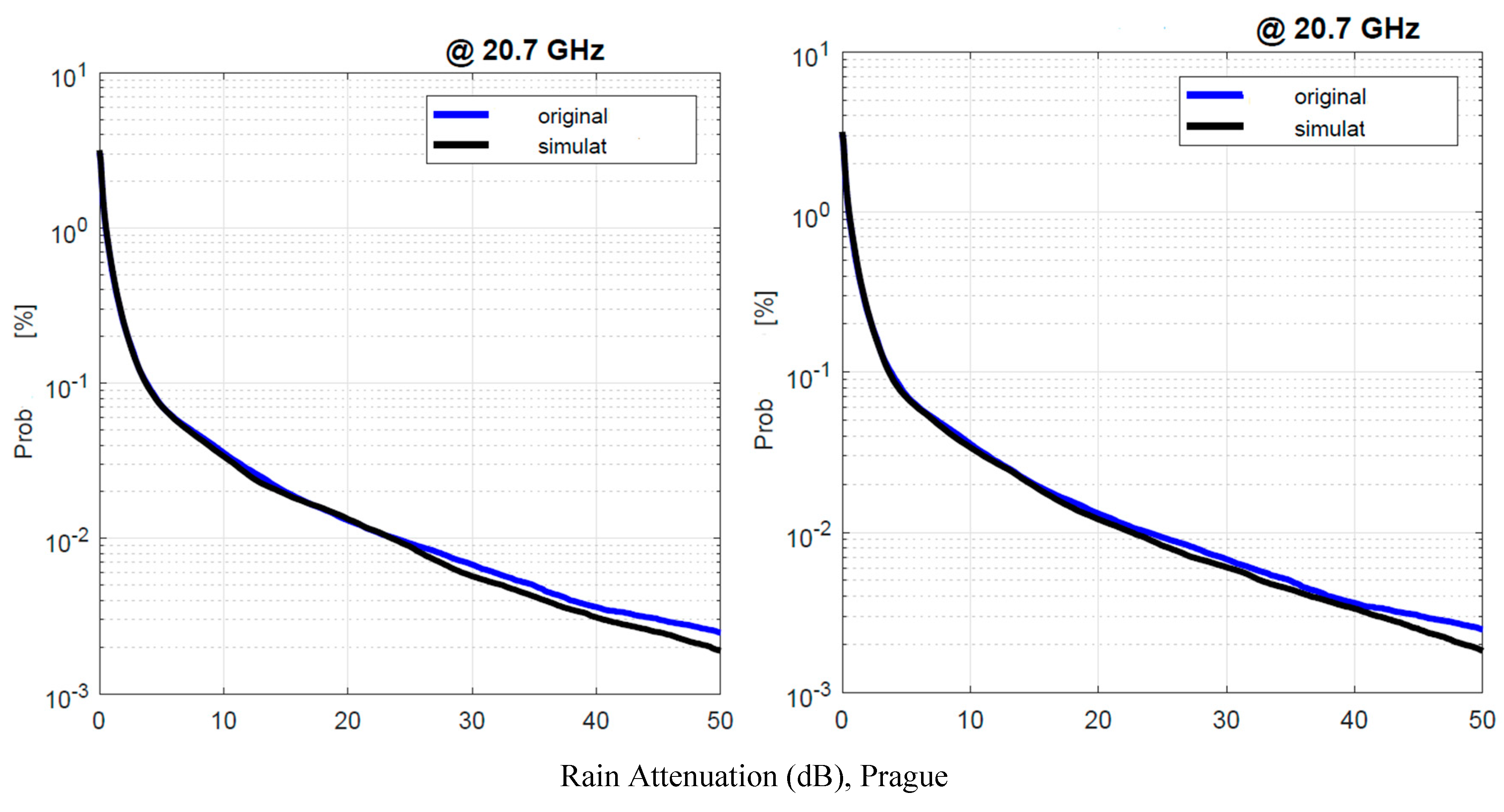

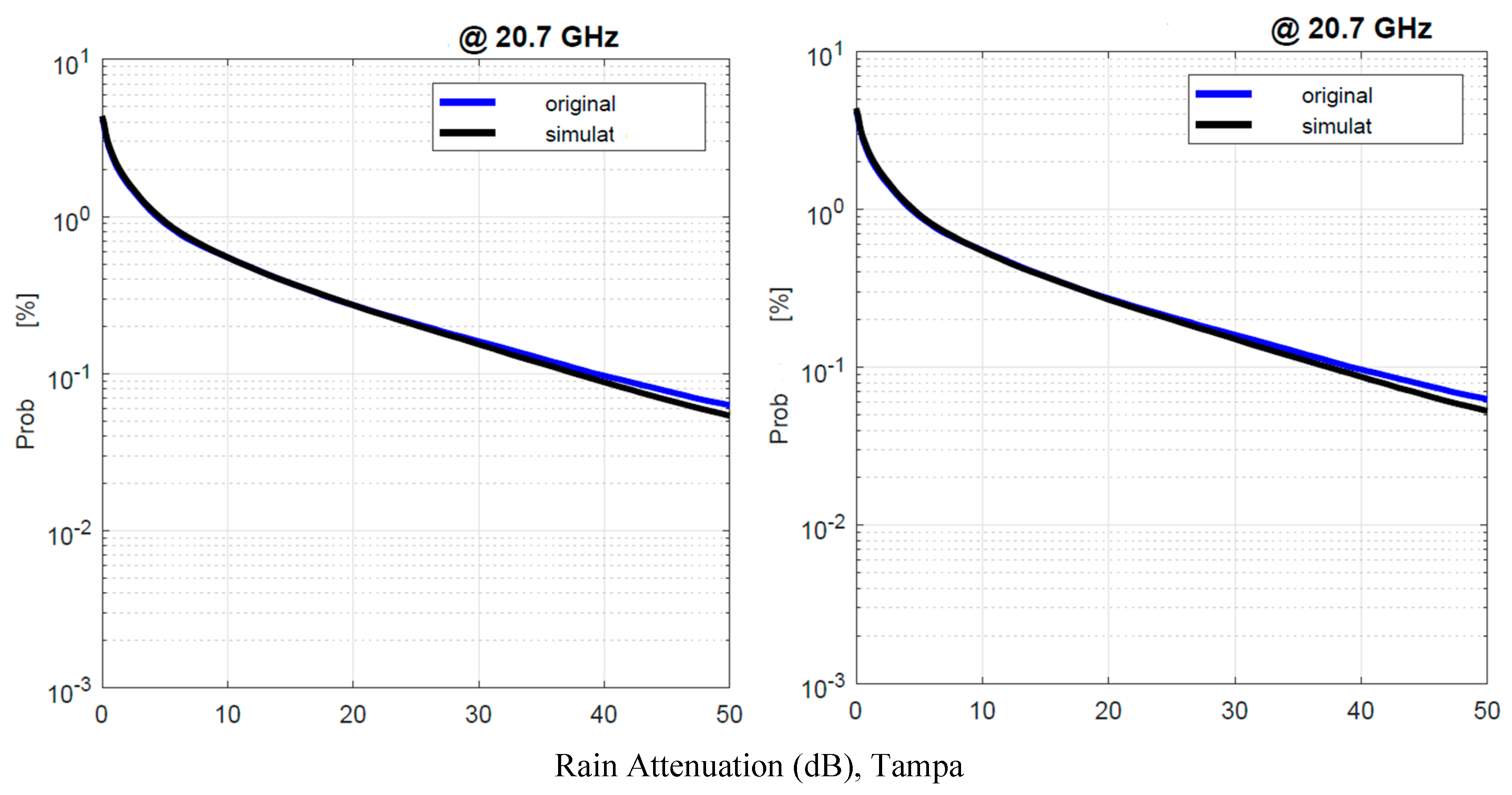

From these figures we notice that the simulation with the local conditional PDFs (

Appendix B) gives better results than that with the parameters of Spino d’Adda (Table 2), as expected. However, notice that in the simulations with the data of Spino d’Adda, the largest errors mostly occur at the lowest probabilities. In real applications, as the one we show in the next sections, these probabilities correspond to few minutes. For example, in Madrid –

Figure 14, the worst site for this comparison –, in the arithmetic average year of the 9–year period here considered,

for about 2.2% of the time, i.e. about

min. Now,

Figure 14 shows that the error is less than

mm/h for probabilities smaller than

therefore only for

minutes the errror is larger than

minutes. In other words, for almost all the time the error is negligible.

Figure 14.

Madrid. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 14.

Madrid. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 15.

Prague. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 15.

Prague. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 16.

Tampa. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 16.

Tampa. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 16.

White Sands. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 16.

White Sands. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 17.

Vancouver. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

Figure 17.

Vancouver. Probability distrbution that the 1–min rain rate in abscissa is exceeded in the experimental data, , blue line, and in the simulated 1–min data, , black line. Left panel: is obtained by using local values of the conditional PDFs; Right panel: is obtained by using Spino d’Adda conditional PDFs (Table 2).

In the next section, as an example of the possible applications, we apply the theory to the important case of estimating the rain attenuation in slant paths to satellites in the Geostationary orbit with a powerful tool, the Synthetic Storm Technique.