Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgae Strains and Culture Condition

2.2. Microalgae Cultivation in a Photobioreactor

2.2.1. Photobioreactor (PBR) Setup and Operation

2.1.2. Inoculum Preparation

2.2.3. Nutrient Media Preparation and Composition

2.1.4. Salt Stress Treatment

2.1.5. Biomass Harvesting

2.3. Microalgae Growth Determination

- mT: Mass of the filter after drying (g).

- mA: Mass of the filter before filtration (g).

- Vδ: Volume of the filtered sample (L).

2.4. Thermal Pretreatment

2.5. Biomass Composition Analysis

2.5.1. Pigment Determination

2.5.2. Protein Determination

2.5.3. Carbohydrate Determination

2.5.4. Lipid Determination

2.5.5. Fatty Acid Profile Analysis

2.5.6. Volatile Solids (VS) Analysis

2.6. Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Test

- mi: Mass of inoculum (g)

- mtot: Total mass in the bottle (400 g)

-

VSs: Volatile solids in the substrate

- VSi: Volatile solids in the inoculum

- ISR: Inoculum-to-substrate ratio, defined as:

2.7. Energy Output (kJ) Based on the Biogas Production Potential

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

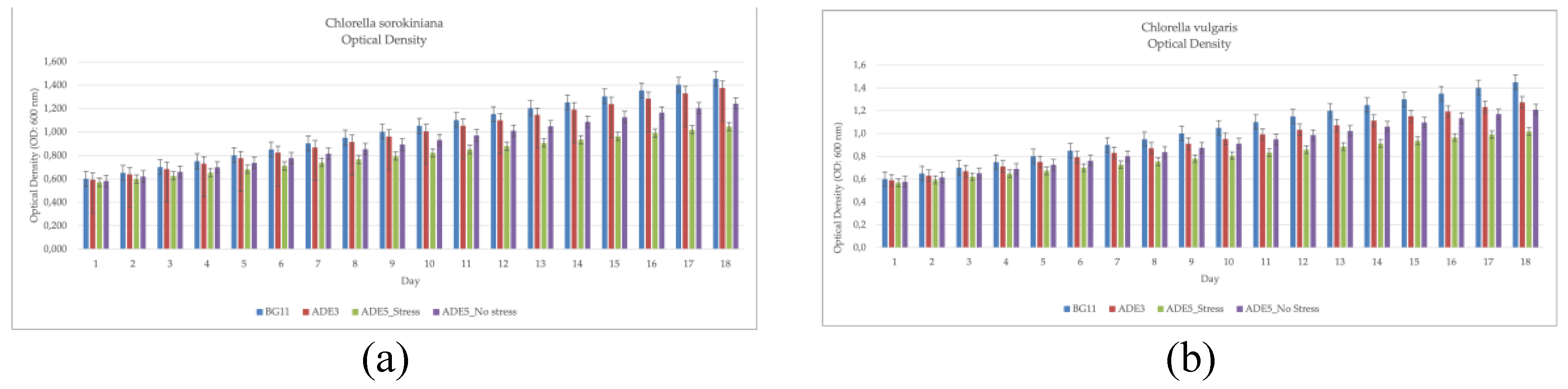

3.1. Optical Density and Biomass Production

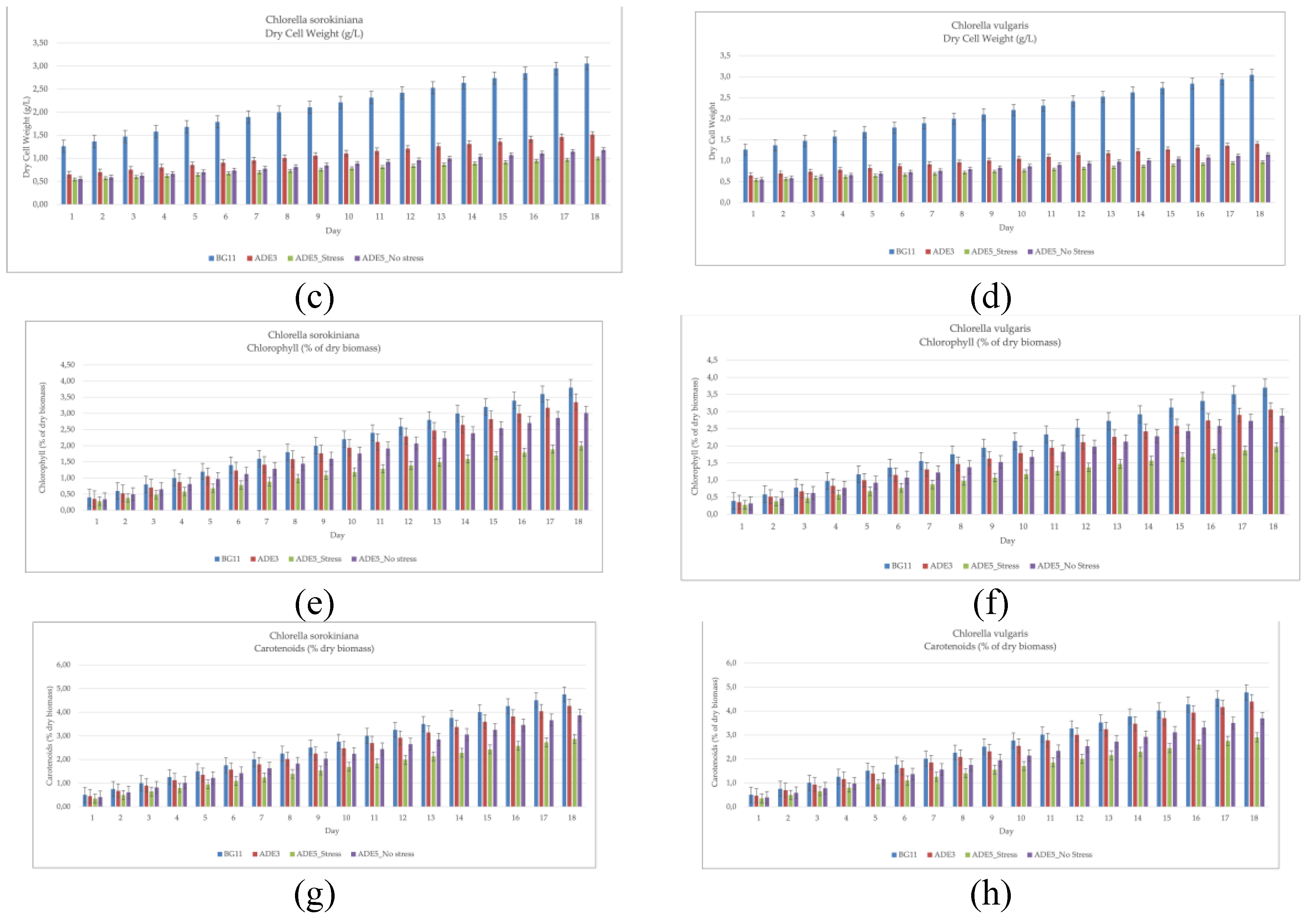

3.2. Protein Accumulation

3.3. Carbohydrates Accumulation

3.4. Lipids Accumulation

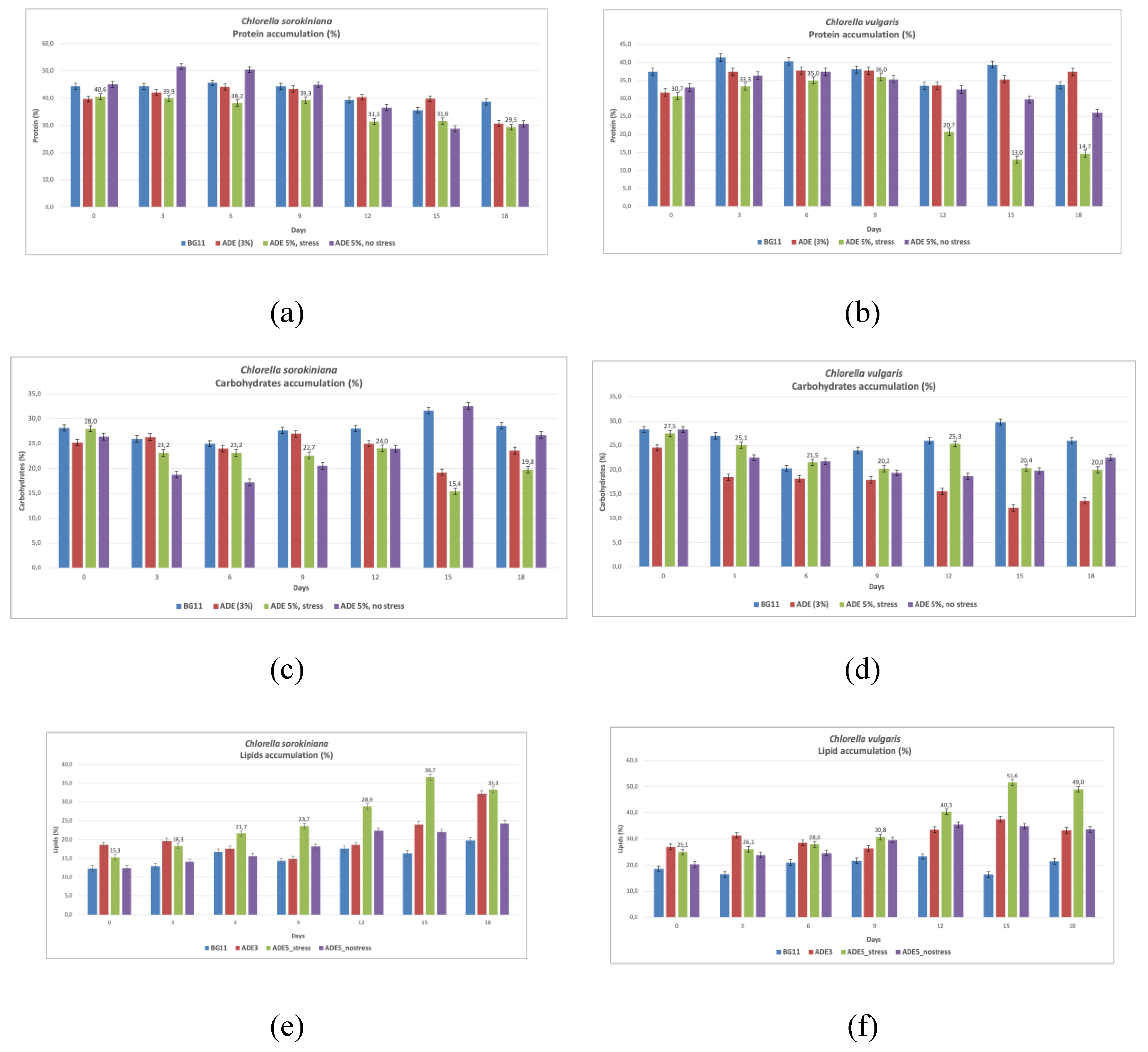

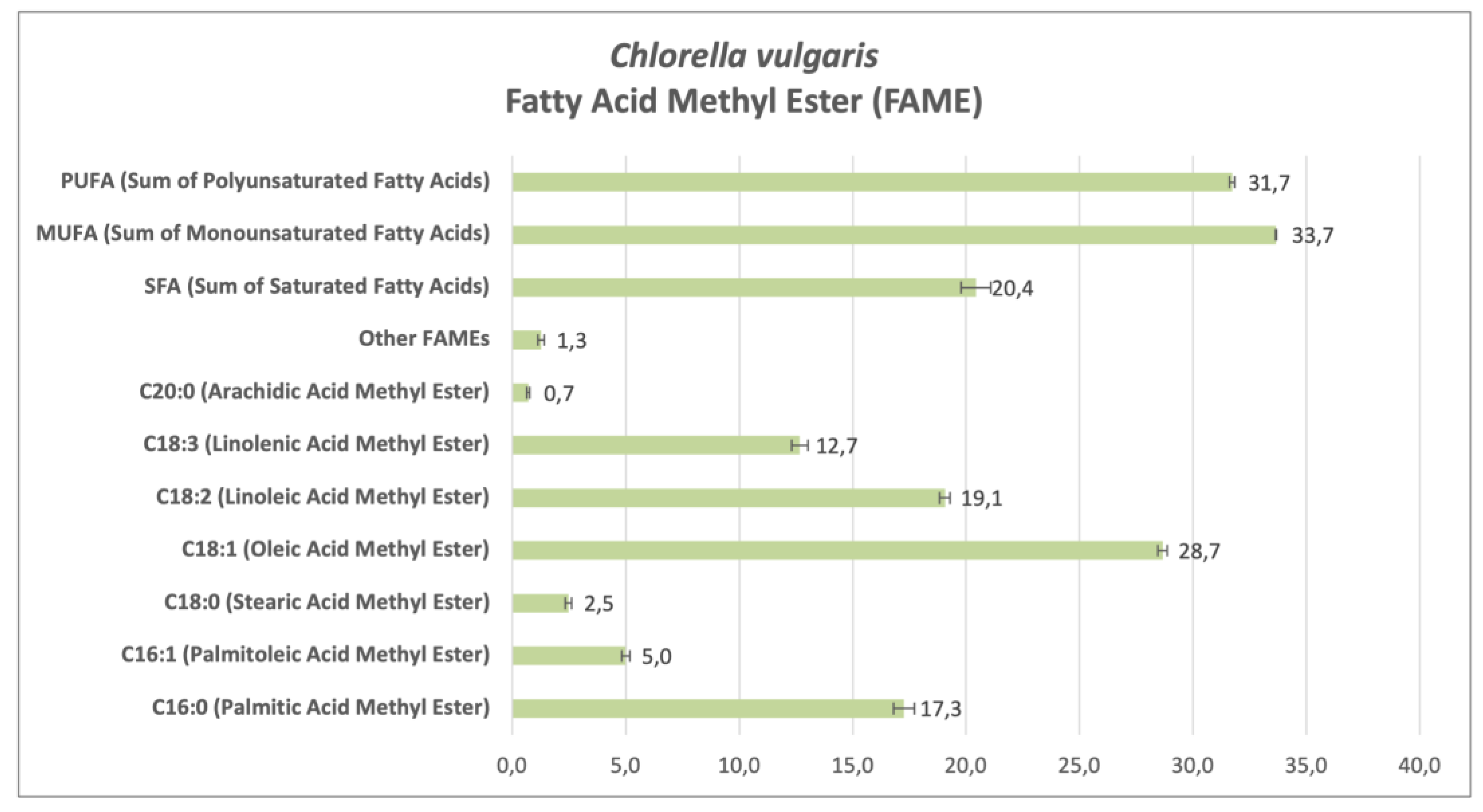

3.5. Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Profiles

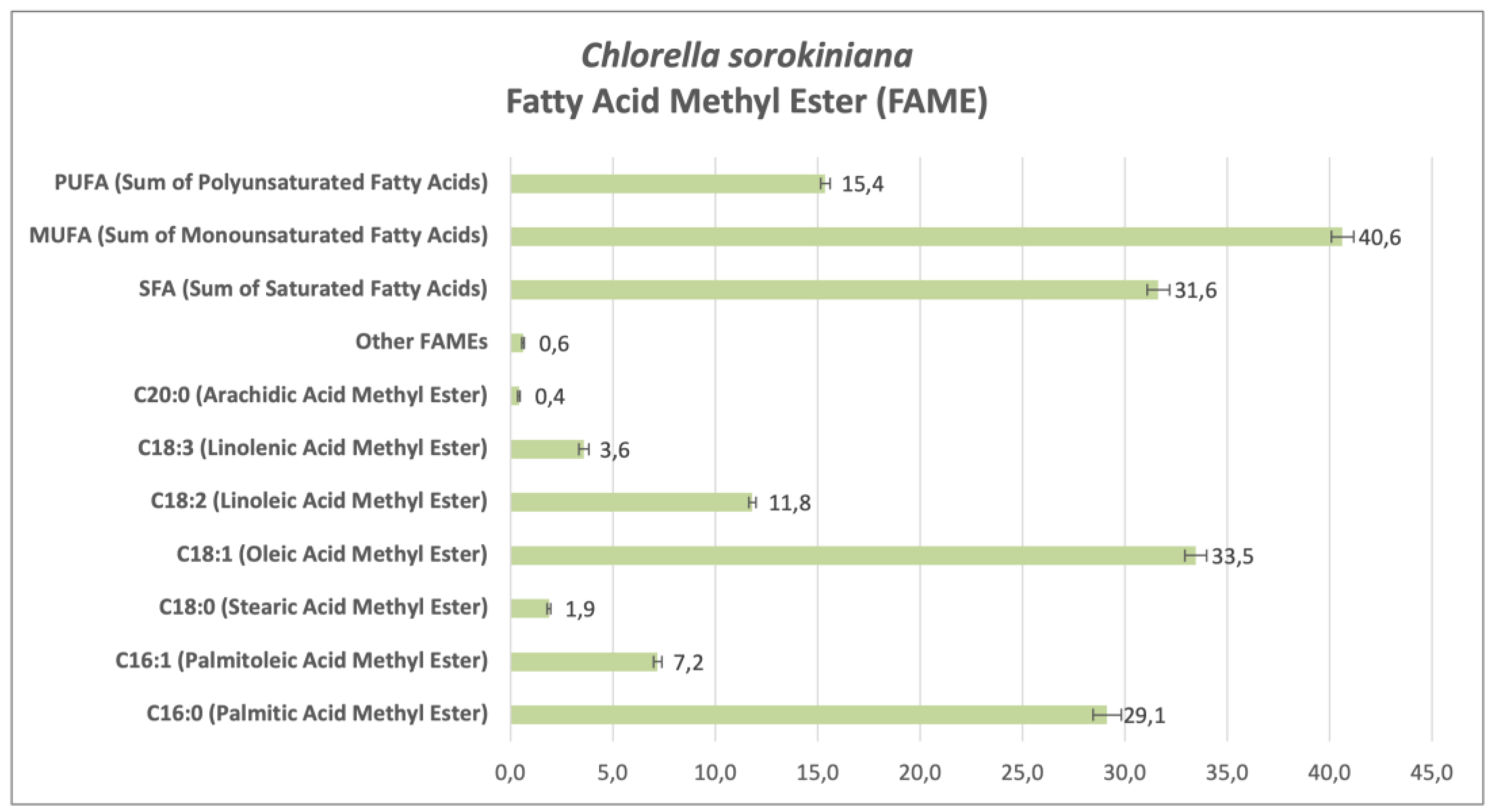

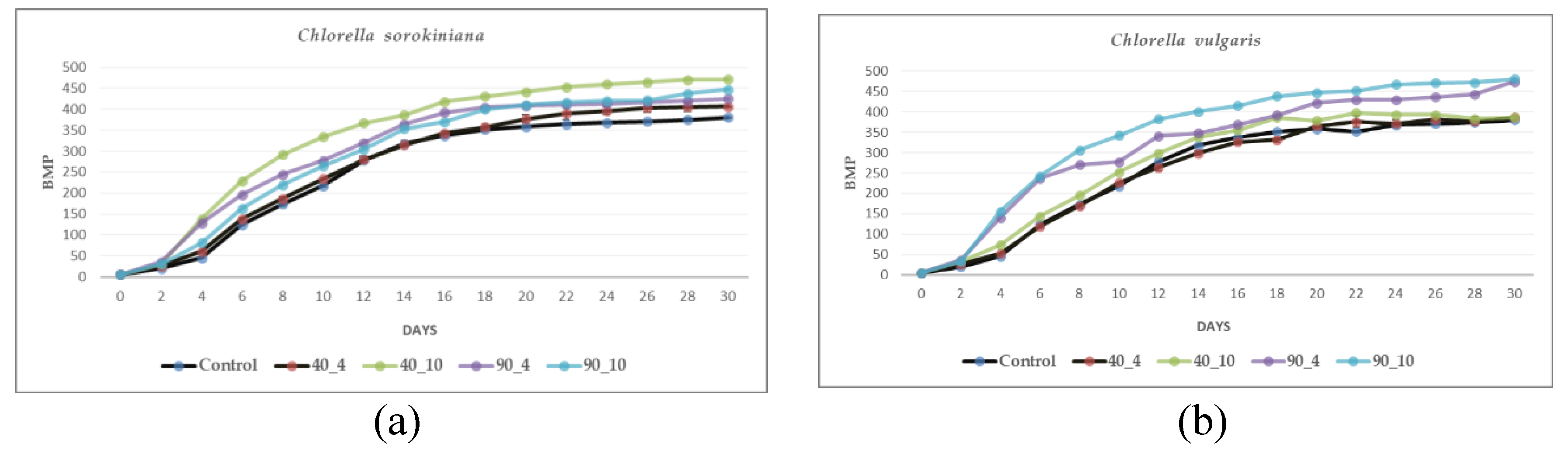

3.6. BMP: Influence of Anaerobic Digestate Effluent and Stress

3.7. Impact of Thermal Pretreatment and Energy Efficiency of Thermal Pretreatment for Enhanced Methane Production

3.7. Economic Feasibility and Scalability of Implementation in Industrial Biofuel Production Plans

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendez, L.; Mahdy, A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Methane production of thermally pretreated Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus sp. biomass at increasing biomass loads. Appl. Energy 2014, 129, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, L.; Mahdy, A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Biomethane production using fresh and thermally pretreated Chlorella vulgaris biomass: A comparison of batch and semi-continuous feeding mode. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 84, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Q.M.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Shahbazi, A. A combined pretreatment, fermentation and ethanol-assisted liquefaction process for production of biofuel from Chlorella sp. Fuel 2019, 257, 116026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsolek, M.D.; Kendall, E.; Thompson, P.L.; Shuman, T.R. Thermal pretreatment of algae for anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 151, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohutskyi, P.; Betenbaugh, M.J.; Bouwer, E.J. The effects of alternative pretreatment strategies on anaerobic digestion and methane production from different algal strains. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 155, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giang, T.T.; Lunprom, S.; Liao, Q.; Reungsang, A.; Salakkam, A. Improvement of hydrogen production from Chlorella sp. biomass by acid-thermal pretreatment. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, G.; Lu, X.; Kobayashi, T.; Kumar, G.; Xu, K. Anaerobic co-digestion on improving methane production from mixed microalgae ( Scenedesmus sp., Chlorella sp.) and food waste: Kinetic modeling and synergistic impact evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 299, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, F.; Hom-Diaz, A.; Blanquez, P.; Vicent, T.; Ferrer, I. Improving biogas production from microalgae by enzymatic pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, O.; Passos, F.; Chamy, R. Enzymatic Pretreatment of Microalgae: Cell Wall Disruption, Biomass Solubilisation and Methane Yield Increase. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 189, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Fernandez, C.; Barreiro-Vescovo, S.; De Godos, I.; Fernandez, M.; Zouhayr, A.; Ballesteros, M. Biochemical methane potential of microalgae biomass using different microbial inocula. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Park, S.; Seon, J.; Yu, J.; Lee, T. Evaluation of thermal, ultrasonic and alkali pretreatments on mixed-microalgal biomass to enhance anaerobic methane production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lee, E.; Dilbeck, M.P.; Liebelt, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ergas, S.J. Thermal pretreatment of microalgae for biomethane production: experimental studies, kinetics and energy analysis. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 92, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarashi, J.Q.M.; El-Zohary, S.E.; Ellabban, M.A.; Abomohra, A.E.-F. Enhancement of lipid production and energy recovery from the green microalga Chlorella vulgaris by inoculum pretreatment with low-dose cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAPP). Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 204, 112314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, A.; Mendez, L.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Autohydrolysis and alkaline pretreatment effect on Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus sp. methane production. Energy 2014, 78, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Enzymatic pretreatment of Chlorella vulgaris for biogas production: Influence of urban wastewater as a sole nutrient source on macromolecular profile and biocatalyst efficiency. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizzul, A.M.; Hellier, P.; Purton, S.; Baganz, F.; Ladommatos, N.; Campos, L. Combined remediation and lipid production using Chlorella sorokiniana grown on wastewater and exhaust gases. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 151, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntila, D.J.; Bautista, M.A.; Monotilla, W. Biomass and lipid production of a local isolate Chlorella sorokiniana under mixotrophic growth conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 191, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psachoulia, P.; Schortsianiti, S.-N.; Lortou, U.; Gkelis, S.; Chatzidoukas, C.; Samaras, P. Assessment of Nutrients Recovery Capacity and Biomass Growth of Four Microalgae Species in Anaerobic Digestion Effluent. Water 2022, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collos, Y.; Harrison, P.J. Acclimation and toxicity of high ammonium concentrations to unicellular algae. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 80, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tan, J.; Mu, Y.; Gao, J. Lipid accumulation of Chlorella sp. TLD6B from the Taklimakan Desert under salt stress. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Pei, H.; Chen, S.; Jiang, L.; Hou, Q.; Yang, Z.; Yu, Z. Salinity-induced cellular cross-talk in carbon partitioning reveals starch-to-lipid biosynthesis switching in low-starch freshwater algae. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, G.; Nishchal; Goud, V.V. Salinity induced lipid production in microalgae and cluster analysis (ICCB 16-BR_047). Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 242, 244–252. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ge, H.; Liu, T.; Tian, X.; Wang, Z.; Guo, M.; Chu, J.; Zhuang, Y. Salt stress induced lipid accumulation in heterotrophic culture cells of Chlorella protothecoides : Mechanisms based on the multi-level analysis of oxidative response, key enzyme activity and biochemical alteration. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 228, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Liao, Q.; Fu, Q.; Liu, Z. Hydrothermal treatment of Chlorella sp.: Influence on biochemical methane potential, microbial function and biochemical metabolism. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellburn, A.R. The Spectral Determination of Chlorophylls a and b, as well as Total Carotenoids, Using Various Solvents with Spectrophotometers of Different Resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.; Silva, A.; Rocha, J. Extraction and quantification of pigments from a marine microalga: a simple and reproducible method. 2007.

- Schwenzfeier, A.; Wierenga, P.A.; Gruppen, H. Isolation and characterization of soluble protein from the green microalgae Tetraselmis sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 9121–9127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuBois, Michel.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, Fred. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guihéneuf, F.; Schmid, M.; Stengel, D.B. Lipids and Fatty Acids in Algae: Extraction, Fractionation into Lipid Classes, and Analysis by Gas Chromatography Coupled with Flame Ionization Detector (GC-FID). In Natural Products From Marine Algae; Stengel, D.B., Connan, S., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2015; Vol. 1308, pp. 173–190 ISBN 978-1-4939-2683-1. [CrossRef]

- Lipps, W.; Baxter, T.; Braun-Howland, E. Standard Methods Committee of the American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, and Water Environment Federation. 2540 Solids. In Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; 23rd ed.; Washington DC: APHA Press, 2018.

- Weik, M. Computer Science and Communications Dictionary; 1 edition.; Springer, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7923-8425-0.

- Haji Abolhasani, M.; Safavi, M.; Goodarzi, M.T.; Kassaee, S.M.; Azin, M. Statistical optimization of medium with response surface methodology for biomass production of a local Iranian microalgae Picochlorum sp. RCC486. Adv. Res. Microb. Metab. Technol. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheadle, C.; Vawter, M.P.; Freed, W.J.; Becker, K.G. Analysis of Microarray Data Using Z Score Transformation. J. Mol. Diagn. 2003, 5, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B. A Zipf-plot based normalization method for high-throughput RNA-seq data. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markou, G.; Nerantzis, E. Microalgae for high-value compounds and biofuels production: A review with focus on cultivation under stress conditions. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juneja, A.; Ceballos, R.; Murthy, G. Effects of Environmental Factors and Nutrient Availability on the Biochemical Composition of Algae for Biofuels Production: A Review. Energies 2013, 6, 4607–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, W.; Yen, H.-W.; Ho, S.-H.; Lo, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.-L.; Ren, N.; Chang, J.-S. Cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris JSC-6 with swine wastewater for simultaneous nutrient/COD removal and carbohydrate production. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 198, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illman, A.M.; Scragg, A.H.; Shales, S.W. Increase in Chlorella strains calorific values when grown in low nitrogen medium. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2000, 27, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriwastav, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Ansari, F.A.; Rawat, I.; Bux, F. Adaptability of growth and nutrient uptake potential of Chlorella sorokiniana with variable nutrient loading. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 174, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, E.; Morales, M. del M.; Gomez, C.; Acién, F.G.; Muñoz, R. Influence of pH and CO2 source on the performance of microalgae-based secondary domestic wastewater treatment in outdoors pilot raceways. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 265, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Owende, P. Biofuels from microalgae—A review of technologies for production, processing, and extractions of biofuels and co-products. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisti, Y. Biodiesel from microalgae. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohutskyi, P.; Kligerman, D.C.; Byers, N.; Nasr, L.K.; Cua, C.; Chow, S.; Su, C.; Tang, Y.; Betenbaugh, M.J.; Bouwer, E.J. Effects of inoculum size, light intensity, and dose of anaerobic digestion centrate on growth and productivity of Chlorella and Scenedesmus microalgae and their poly-culture in primary and secondary wastewater. Algal Res. 2016, 19, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X. Isolation and Characterization of Chlorella Sorokiniana Gxnn01 (chlorophyta) with the Properties of Heterotrophic and Microaerobic Growth. J. Phycol. 2009, 45, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Zhao, F.J.; Yu, D.D. Effect of nitrogen limitation on cell growth, lipid accumulation and gene expression in Chlorella sorokiniana. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2015, 58, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Wei, X.; Wang, Y. The influence of light intensity and organic content on cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris in sludge extracts diluted with BG11. Aquac. Int. 2021, 29, 2131–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, A.J.; Shevchenko, A.; Pick, U.; Katz, A. Enhanced Photosynthesis and Redox Energy Production Contribute to Salinity Tolerance in Dunaliella as Revealed by Homology-Based Proteomics. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2806–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, P.; Deng, Z.; Fan, L.; Hu, Z. Lipid accumulation and growth characteristics of Chlorella zofingiensis under different nitrate and phosphate concentrations. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2012, 114, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, L.; Chen, S. High productivity cultivation of a heat-resistant microalga Chlorella sorokiniana for biofuel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xu, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Growth optimisation of microalga mutant at high CO2 concentration to purify undiluted anaerobic digestion effluent of swine manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 177, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Jin, H.-F.; Lim, B.-R.; Park, K.-Y.; Lee, K. Ammonia removal from anaerobic digestion effluent of livestock waste using green alga Scenedesmus sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8649–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiusi, F.; Wijffels, R.H.; Janssen, M. Doubling of Microalgae Productivity by Oxygen Balanced Mixotrophy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 6065–6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safafar, H.; Uldall Nørregaard, P.; Ljubic, A.; Møller, P.; Løvstad Holdt, S.; Jacobsen, C. Enhancement of Protein and Pigment Content in Two Chlorella Species Cultivated on Industrial Process Water. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2016, 4, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, J.A.; Moreno, J.; Rodrı́guez, H.; Angeles Vargas, M.; Rivas, J.; Guerrero, M.G. Carotenoid content of chlorophycean microalgae: factors determining lutein accumulation in Muriellopsis sp. (Chlorophyta). J. Biotechnol. 2000, 76, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancha, I.; Chokshi, K.; Maurya, R.; Trivedi, K.; Patidar, S.K.; Ghosh, A.; Mishra, S. Salinity induced oxidative stress enhanced biofuel production potential of microalgae Scenedesmus sp. CCNM 1077. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 189, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-M.; Liu, H.-J.; Zhang, X.-W.; Chen, F. Production of biomass and lutein by Chlorella protothecoides at various glucose concentrations in heterotrophic cultures. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.; Lukyanov, A.; Solovchenko, O.; Didi-Cohen, S.; Boussiba, S.; Khozin-Goldberg, I. Interactive effects of salinity, high light, and nitrogen starvation on fatty acid and carotenoid profiles in Nannochloropsis oceanica CCALA 804. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2014, 116, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.W. Micro-algae as a source of protein. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, P.; Min, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ruan, R.R. Anaerobic digested dairy manure as a nutrient supplement for cultivation of oil-rich green microalgae Chlorella sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.J.; Harrison, S.T.L. Lipid productivity as a key characteristic for choosing algal species for biodiesel production. J. Appl. Phycol. 2009, 21, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, E.E.; Bulynina, S.S.; Ziganshin, A.M. Growth Characteristics of Chlorella sorokiniana in a Photobioreactor during the Utilization of Different Forms of Nitrogen at Various Temperatures. Plants 2022, 11, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutra, E.; Mastropetros, S.G.; Ali, S.S.; Tsigkou, K.; Kornaros, M. Assessing the potential of Chlorella vulgaris for valorization of liquid digestates from agro-industrial and municipal organic wastes in a biorefinery approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropetros, S.G.; Koutra, E.; Amouri, M.; Aziza, M.; Ali, S.S.; Kornaros, M. Comparative Assessment of Nitrogen Concentration Effect on Microalgal Growth and Biochemical Characteristics of Two Chlorella Strains Cultivated in Digestate. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.K.; Schuhmann, H.; Schenk, P.M. High Lipid Induction in Microalgae for Biodiesel Production. Energies 2012, 5, 1532–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-H.; Huang, S.-W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hasunuma, T.; Kondo, A.; Chang, J.-S. Characterization and optimization of carbohydrate production from an indigenous microalga Chlorella vulgaris FSP-E. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 135, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chang, J.-S. Effect of light intensity and nitrogen starvation on CO2 fixation and lipid/carbohydrate production of an indigenous microalga Scenedesmus obliquus CNW-N. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 113, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, M.A.; Lombardi, A.T.; da Graça Gama Melão, M.; Parrish, C.C. Combined nitrogen limitation and cadmium stress stimulate total carbohydrates, lipids, protein and amino acid accumulation in Chlorella vulgaris (Trebouxiophyceae). Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 160, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choix, F.J.; de-Bashan, L.E.; Bashan, Y. Enhanced accumulation of starch and total carbohydrates in alginate-immobilized Chlorella spp. induced by Azospirillum brasilense: II. Heterotrophic conditions. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2012, 51, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Li, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, X.; Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Improving carbohydrate and starch accumulation in Chlorella sp. AE10 by a novel two-stage process with cell dilution. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Qi, W.; Cheng, D.; Tang, T.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Enhancing Carbohydrate Productivity of Chlorella sp. AE10 in Semi-continuous Cultivation and Unraveling the Mechanism by Flow Cytometry. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 185, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.-K.; Yun, H.-S.; Park, S.; Lee, H.; Park, Y.-T.; Bae, S.; Ham, J.; Choi, J. Effect of food wastewater on biomass production by a green microalga Scenedesmus obliquus for bioenergy generation. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 179, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markou, G.; Angelidaki, I.; Georgakakis, D. Microalgal carbohydrates: an overview of the factors influencing carbohydrates production, and of main bioconversion technologies for production of biofuels. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, S.; Izumi, Y.; Matsuda, F.; Hasunuma, T.; Chang, J.-S.; Kondo, A. Synergistic enhancement of glycogen production in Arthrospira platensis by optimization of light intensity and nitrate supply. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 108, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Ai, J.; Cao, X.; Xue, S.; Zhang, W. Enhancing starch production of a marine green microalga Tetraselmis subcordiformis through nutrient limitation. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 118, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, M.S.; Cokus, S.J.; Gallaher, S.D.; Walter, A.; Lopez, D.; Erickson, E.; Endelman, B.; Westcott, D.; Larabell, C.A.; Merchant, S.S.; et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and transcriptome of the green alga Chromochloris zofingiensis illuminates astaxanthin production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, R.; Pap, B.; Böjti, T.; Shetty, P.; Lakatos, G.; Bagi, Z.; Kovács, K.L.; Maróti, G. Chlorella vulgaris and Its Phycosphere in Wastewater: Microalgae-Bacteria Interactions During Nutrient Removal. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tale, M.P.; Devi Singh, R.; Kapadnis, B.P.; Ghosh, S.B. Effect of gamma irradiation on lipid accumulation and expression of regulatory genes involved in lipid biosynthesis in Chlorella sp. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, A.; Murphy, J.D. Microalgal Cultivation in Treating Liquid Digestate from Biogas Systems. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwoba, E.G.; Mickan, B.S.; Moheimani, N.R. Chlorella sp. growth under batch and fed-batch conditions with effluent recycling when treating the effluent of food waste anaerobic digestate. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 3545–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yan, C.; Li, Z. Microalgal cultivation with biogas slurry for biofuel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 220, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, J.M.; Moheimani, N.R.; Borowitzka, M.A. Growth of microalgae on undiluted anaerobic digestate of piggery effluent with high ammonium concentrations. Algal Res. 2017, 24, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornsson, W.J.; Nicol, R.W.; Dickinson, K.E.; McGinn, P.J. Anaerobic digestates are useful nutrient sources for microalgae cultivation: functional coupling of energy and biomass production. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G. Improving biodiesel fuel properties by modifying fatty ester composition. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G. “Designer” Biodiesel: Optimizing Fatty Ester Composition to Improve Fuel Properties. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 1358–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Wu, Q. Biodiesel production from heterotrophic microalgal oil. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F. Differential lipid and fatty acid profiles of photoautotrophic and heterotrophic Chlorella zofingiensis: Assessment of algal oils for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talebi, A.F.; Mohtashami, S.K.; Tabatabaei, M.; Tohidfar, M.; Bagheri, A.; Zeinalabedini, M.; Hadavand Mirzaei, H.; Mirzajanzadeh, M.; Malekzadeh Shafaroudi, S.; Bakhtiari, S. Fatty acids profiling: A selective criterion for screening microalgae strains for biodiesel production. Algal Res. 2013, 2, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegazzo, M.L.; Ulusoy-Erol, H.B.; Hestekin, C.N.; Hestekin, J.A.; Fonseca, G.G. Evaluation of the yield, productivity, and composition of fatty acids methyl esters (FAME) obtained from the lipidic fractions extracted from Chlorella sorokiniana by using ultrasound and agitation combined with solvents. Biofuels 2022, 13, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sahu, A.K.; Rusten, B.; Park, C. Anaerobic co-digestion of microalgae Chlorella sp. and waste activated sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 142, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, C.; Sialve, B.; Bernet, N.; Steyer, J.P. Thermal pretreatment to improve methane production of Scenedesmus biomass. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 40, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sialve, B.; Bernet, N.; Bernard, O. Anaerobic digestion of microalgae as a necessary step to make microalgal biodiesel sustainable. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, J.N.; Kobayashi, N.; Barnes, A.; Noel, E.A.; Betenbaugh, M.J.; Oyler, G.A. Comparative Analyses of Three Chlorella Species in Response to Light and Sugar Reveal Distinctive Lipid Accumulation Patterns in the Microalga C. sorokiniana. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, L.; Mahdy, A.; Timmers, R.A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Enhancing methane production of Chlorella vulgaris via thermochemical pretreatments. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 149, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, F.; Ferrer, I. Influence of hydrothermal pretreatment on microalgal biomass anaerobic digestion and bioenergy production. Water Res. 2015, 68, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.J. le B.; Laurens, L.M.L. Microalgae as biodiesel & biomass feedstocks: Review & analysis of the biochemistry, energetics & economics. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 554–590. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanan, R.; Kim, B.-H.; Cho, D.-H.; Oh, H.-M.; Kim, H.-S. Algae–bacteria interactions: Evolution, ecology and emerging applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composition (mg/L) | ADE | 3% ADE | 5% ADE | BG-11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-NH₄ | 3536 ± 36 | 107 ± 1.08 | 175.4 ± 1.8 | n.d.1 |

| N-NO₃ | 92 ± 8.1 | 2.77 ± 0.24 | 4.6 ± 0.41 | 247.84 |

| TN | 3920 ± 66 | 117.6 ± 1.98 | 195 ± 3.3 | 247.84 |

| P | 81.4 ± 5.8 | 2.1 ± 0.17 | 4.2 ± 0.29 | 5.50 |

| Organic N | 292 ± 21.9 | 7.83 ± 0.68 | 15 ± 1.1 | n.d. |

| COD | 24,200 ± 153 | 726 ± 4.59 | 1210 ± 7.65 | n.d. |

| Ca | 369 ± 3.1 | 11.07 ± 0.09 | 18.45 ± 0.16 | 9.81 |

| Fe | 54 ± 1.4 | 1.62 ± 0.04 | 2.71 ± 0.07 | 1.28 |

| Mg | 225 ± 5.3 | 6.75 ± 0.16 | 11.25 ± 0.27 | 6.98 |

| Mn | 6.33 ± 0.35 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.50 |

| Na | 1884.6 ± 4.5 | 56.54 ± 0.14 | 94.23 ± 0.23 | 212.28 |

| Cl | 1633.6 ± 5.9 | 49.01 ± 0.18 | 81.68 ± 0.3 | 18.02 |

| K | 3161 ± 2.7 | 94.83 ± 0.08 | 158.05 ± 0.14 | 13.70 |

| Cu | 2 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.02 |

| EC | 49.7 dS/m | 2.17 dS/m | 3.15 dS/m | n.a.2 |

| pH | 8.3 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 7.1 |

| Cultivation conditions | OD600 | DCW (g/L) | Chlorophyll (μg/L) | Carotenoids (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSO BG11 | 1.30 a 1 | 2.74 a | 3.20 a | 4.01 a |

| CSO ADE3 | 1.24 b | 1.36 b | 2.82 b | 3.60 b |

| CSO ADE5_stress | 0.96 e | 0.92 e | 2.55 cd | 2.43 d |

| CSO ADE5_nostress | 1.13 cd | 1.07 d | 2.43 d | 3.26 c |

| CVU BG11 | 1.30 a | 2.73 a | 3.12 a | 4.02 a |

| CVU ADE3 | 1.15 c | 1.27 c | 2.58 c | 3.70 b |

| CVU ADE5_stress | 0.94 e | 0.89 e | 1.67 e | 3.11 c |

| CVU ADE5_nostress | 1.10 d | 1.04 d | 1.69 e | 2.45 d |

| Mean | 1.14 | 1.50 | 2.51 | 3.32 |

| LSD 2 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| Cultivation conditions | Proteins (%) | Carbohydrates (%) | Lipids (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSO BG11 | 35.67 ab 1 | 31.70 a | 16.37 e |

| CSO ADE3 | 39.80 a | 19.25 b | 24.07 d |

| CSO ADE5_stress | 31.63 bc | 15.40 bc | 36.67 bc |

| CSO ADE5_nostress | 28.83 c | 32.57 a | 22.00 d |

| CVU BG11 | 39.40 a | 29.82 a | 16.37 e |

| CVU ADE3 | 35.33 ab | 12.13 c | 37.53 b |

| CVU ADE5_stress | 13.00 d | 20.37 b | 51.57 a |

| CVU ADE5_nostress | 29.70 bc | 19.81 b | 34.87 c |

| Mean | 31.67 | 22.63 | 29.93 |

| LSD 2 | 6.00 | 6.27 | 2.08 |

| Cultivation conditions | mL(biogas)/gVS |

|---|---|

| CSO BG11 | 407.1 c 1 |

| CSO ADE3 | 399.3 d |

| CSO ADE5_stress | 418.3 b |

| CSO ADE5_nostress | 407.9 c |

| CVU BG11 | 414.5 b |

| CVU ADE3 | 408.1 c |

| CVU ADE5_stress | 432.8 a |

| CVU ADE5_nostress | 409.2 c |

| Means | 412.1 |

| LSD 2 | 4.8 |

| Cultivation conditions | BMP (mL biogas/gVS) |

Energy Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CSO 40_4 | 407 e 1 | 2.67 a 2 |

| CSO 40_10 | 472 b | 1.24 c |

| CSO 90_4 | 425 d | 0.93 f |

| CSO 90_10 | 448 c | 0.49 h |

| CVU 40_4 | 380 f | 2.54 b |

| CVU 40_10 | 387 f | 1.01 e |

| CVU 90_4 | 474 b | 1.03 d |

| CVU 90_10 | 481 a | 0.55 g |

| Means | 434 | 1.31 |

| LSD 3 | - | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).