Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Suppliers

2.2. Human Sample Preparation

2.3. Equine Sample Preparation

2.4. Bovine Sample Preparation

2.5. Canine Sample Preparation

2.6. Impact of cumene hydroperoxide on sperm motility

2.7. The antioxidant assay system

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

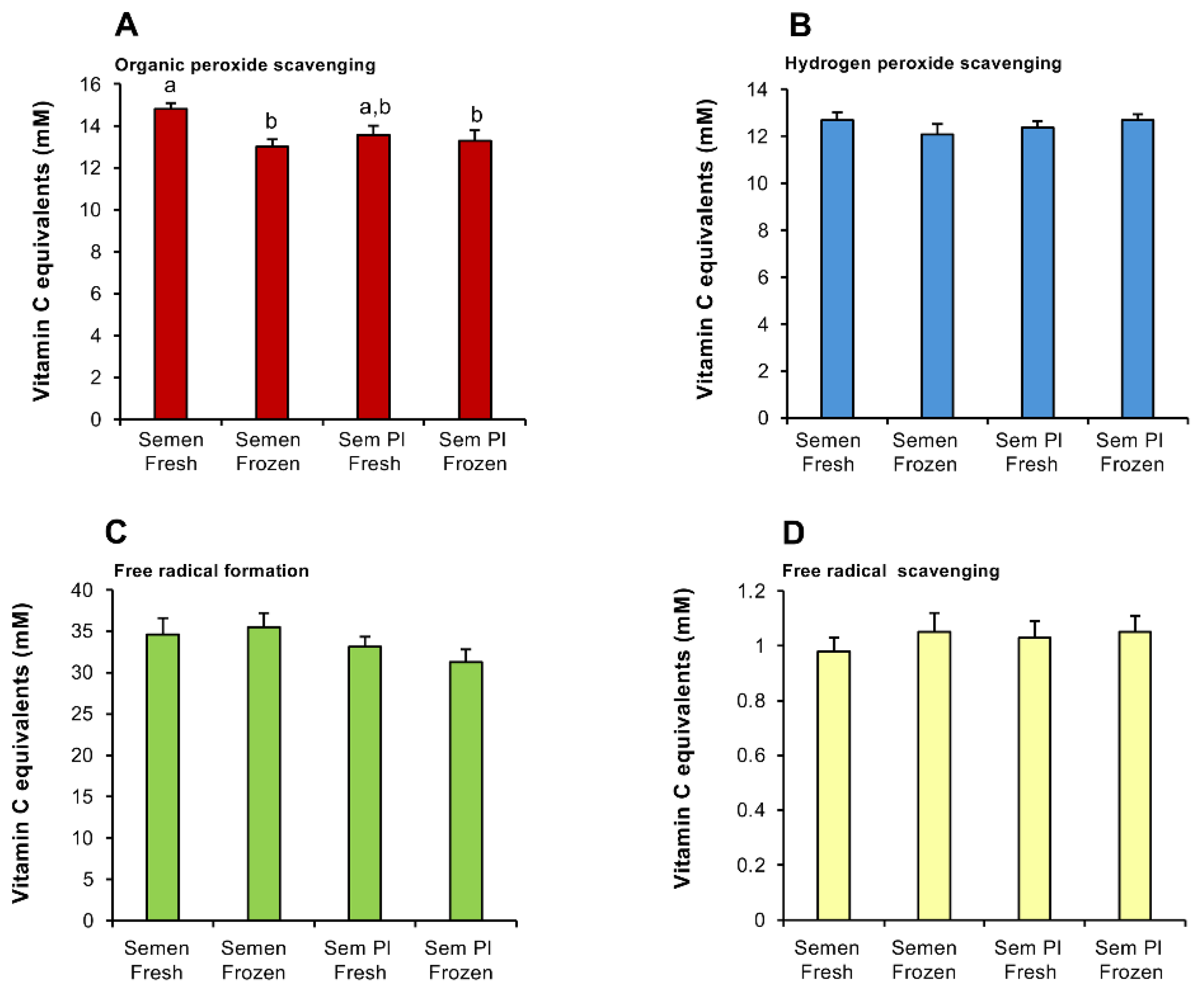

3.1. Impact of spermatozoa and freezing on the antioxidant activity of human semen

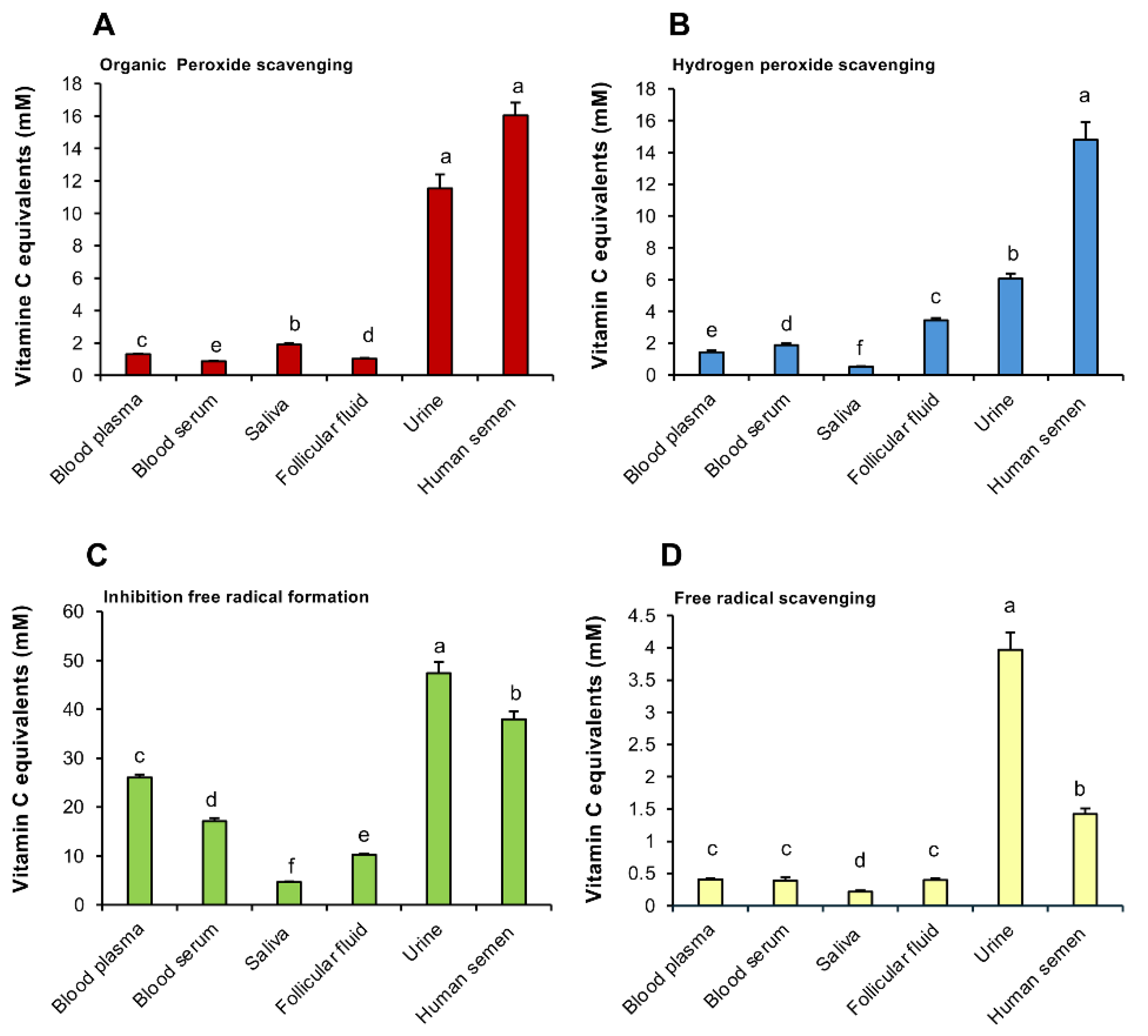

3.2. Antioxidant activity of semen relative to other biological fluids

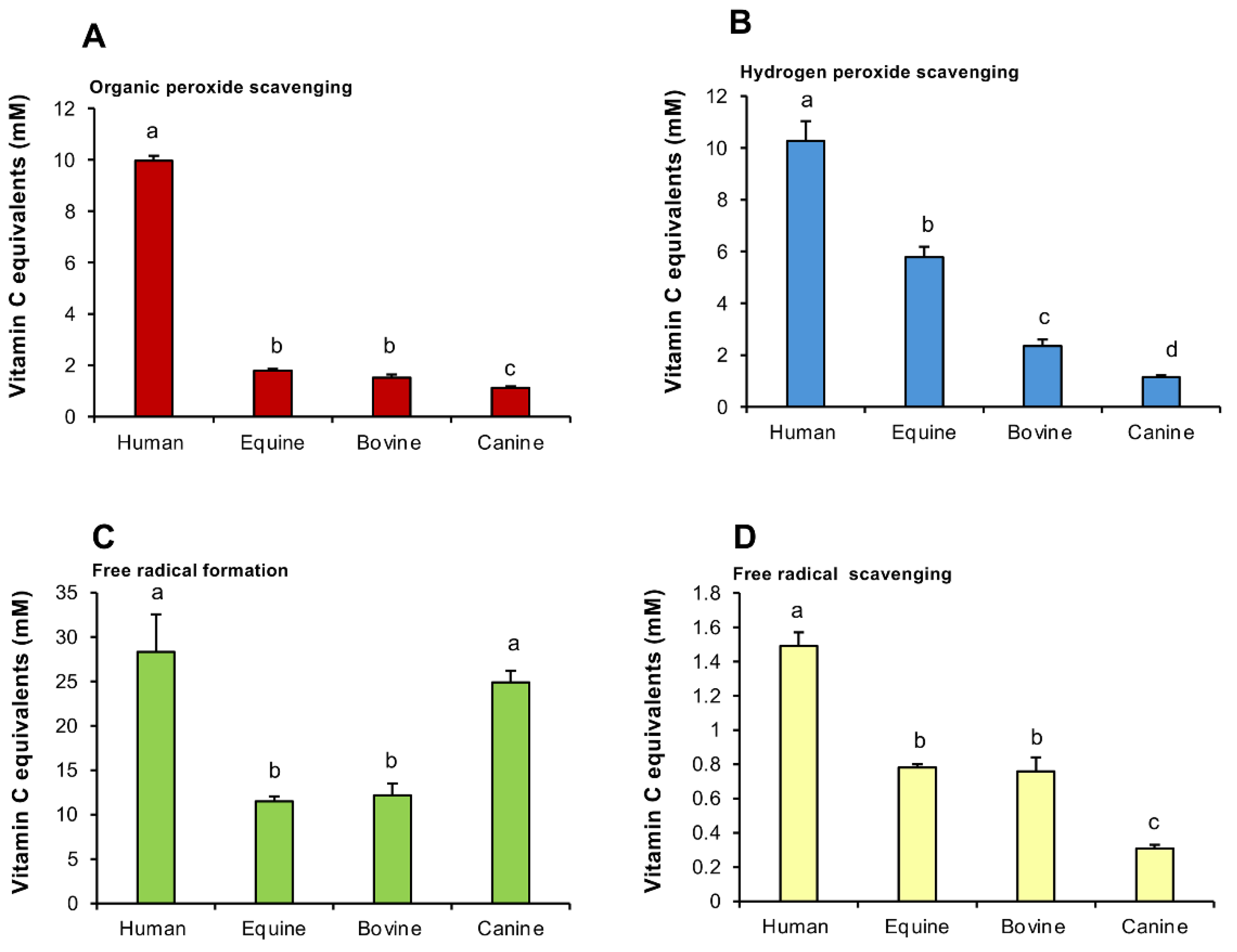

3.2. Seminal plasma in different species

3.3. Impact of oxidative stress on sperm motility in different species

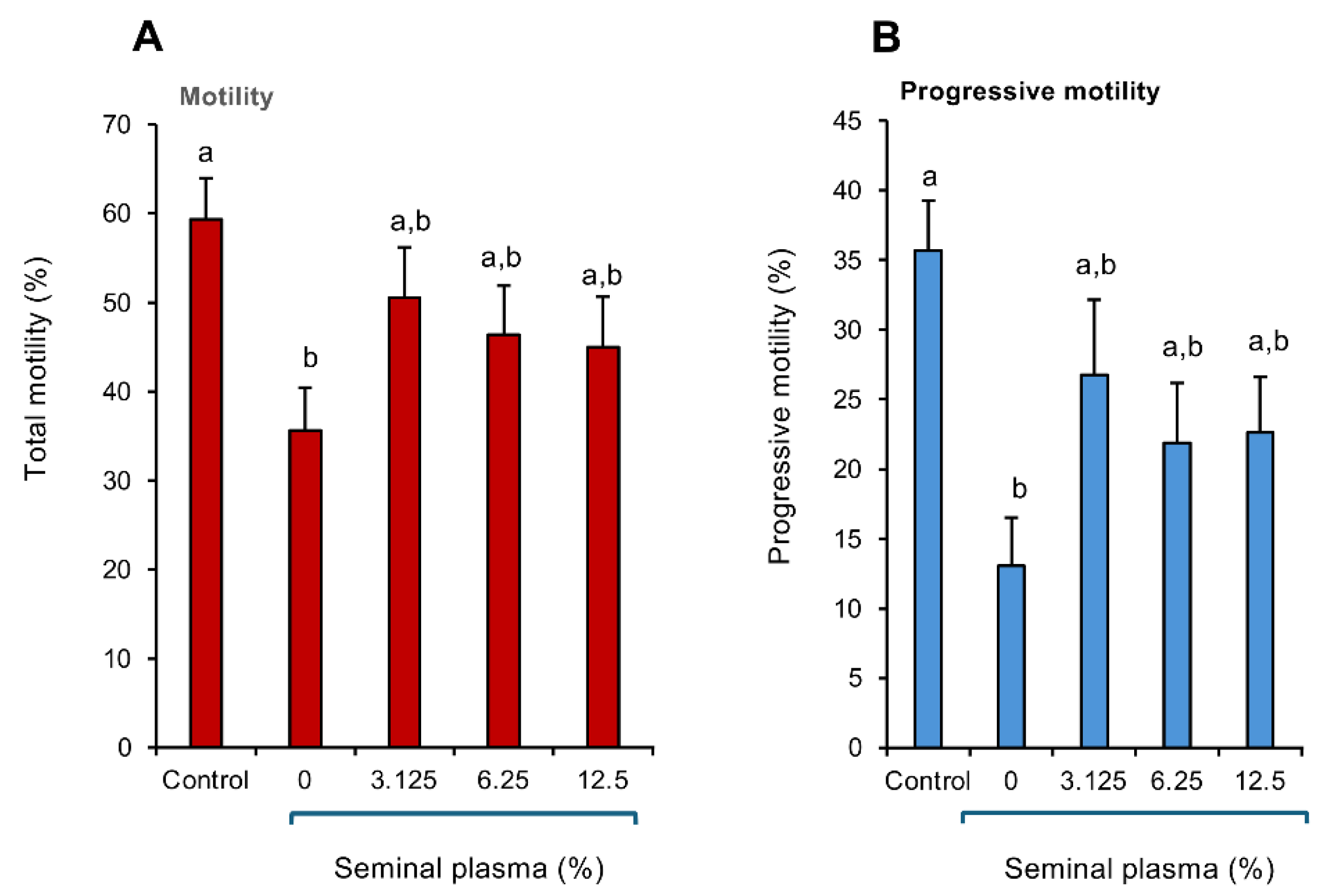

3.4. Impact of seminal plasma on peroxide-mediated toxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Baker, M.A. The role of genetics and oxidative stress in the etiology of male infertility-a unifying hypothesis? Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 581838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. . Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, A.Z.; Hansen, K.R.; Barnhart, K.T.; Cedars, M.I.; Legro, R.S.; Diamond, M.P.; Krawetz, S.A.; Usadi, R.; Baker, V.L.; Coward, R.M.; et al. The effect of antioxidants on male factor infertility: the Males; Antioxidants; and Infertility (MOXI) randomized clinical trial. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 552–560.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, Y. Comparison of L-Carnitine vs. Co Q10 and Vitamin E for idiopathic male infertility: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. Rev. Med Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 4698–4704. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.L.; Wei, Y.; Deng, W.; Wang, C.; Yang, B. Effects of alpha-lipoic acid on sperm quality in patients with varicocele-related male infertility: study protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. Trials 2022, 23, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannatifar, R.; Parivar, K.; Roodbari, N.H.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Effects of N-acetyl-cysteine supplementation on sperm quality; chromatin integrity and level of oxidative stress in infertile men. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2019, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, H.; Shaeer, O.; El-Segini, A. Combination clomiphene citrate and antioxidant therapy for idiopathic male infertility: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 2232–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSheikh, M.G.; Hosny, M.B.; Elshenoufy, A.; Elghamrawi, H.; Fayad, A.; Abdelrahman, S. Combination of vitamin E and clomiphene citrate in treating patients with idiopathic oligoasthenozoospermia: A prospective; randomized trial. Andrology 2015, 3, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarinejad, M.R.; Shafiei, N.; Safarinejad, S. A prospective double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of the effect of saffron (Crocus sativus Linn.) on semen parameters and seminal plasma antioxidant capacity in infertile men with idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comhaire, F.H.; El Garem, Y.; Mahmoud, A.; Eertmans, F.; Schoonjans, F. Combined conventional/antioxidant “Astaxanthin” treatment for male infertility: a double blind; randomized trial. Asian J. Androl. 2005, 7, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, M.; Fakhari Zavareh, Z.; Abbasi, B.; Esmaeili, V.; Shahverdi, A.; Sadighi Gilani, M.A.; Tavalaee, M.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Alpha-lipoic acid supplementation for male partner of couples with recurrent pregnancy loss: a post hoc analysis in clinical trial. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 17, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- de Ligny, W.; Smits, R.M.; Mackenzie-Proctor, R.; Jordan, V.; Fleischer, K.; de Bruin, J.P.; Showell, M.G. Antioxidants for male subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 5, CD007411. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, P.; Dutta, S.; Alahmar, A.T. reductive stress and male infertility. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2022, 1391, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suleiman, S.A.; Ali, M.E.; Zaki, Z.M.; el-Malik, E.M.; Nasr, M.A. Lipid peroxidation and human sperm motility: protective role of vitamin E. J. Androl. 1996, 17, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J. Antioxidant trials-the need to test for stress. Hum. Reprod. Open 2021, 2021, hoab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Wilkins, A.; Harrison, N.; Kobarfard, K.; Lambourne, S. Development of novel; rapid point-of-care assays for monitoring different forms of antioxidant activity – the RoXsta™ system. Antioxidants 2024.

- Aitken, R.J.; Buckingham, D.W.; Harkiss, D.; Paterson, M.; Fisher, H.; Irvine, D.S. The extragenomic action of progesterone on human spermatozoa is influenced by redox regulated changes in tyrosine phosphorylation during capacitation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1996, 117, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linde-Forsberg, C. Artificial insemination with fresh; chilled extended and frozen-thawed semen in the dog. Sem. Vet. Med. Surg. 1995, 10, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, R.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, D.; Sabanegh, E.; Agarwal, A. Diagnostic value of the total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in human seminal plasma. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarboush, N.A.; Al Masoodi, O.; Al Bdour, S.; Sawair, F.; Hassona, Y. Antioxidant capacity and biomarkers of oxidative stress in saliva of khat-chewing patients: a case-control study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, C.P.; Mainau, E.; Cerón, J.J.; Contreras-Aguilar, M.D.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; Navarro, E.; Tecles, F.; Manteca, X.; Escribano, D. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in saliva in pigs: analytical validation and changes in lactation. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, E.C.; Cavinder, C.A.; Wang, S.; Smith, T.; Lemley, C.O.; Dinh, T.T.N. Oxidative stress biomarkers and free amino acid concentrations in the blood plasma of moderately exercised horses indicate adaptive response to prolonged exercise training. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michałek, M.; Tabiś, A.; Noszczyk-Nowak, A. Serum total antioxidant capacity and enzymatic defence of dogs with chronic heart failure and atrial fibrillation: a preliminary study. J. Vet. Res. 2020, 64, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, B.K.; Singh, S.K.; Nakade, U.P.; Singh, V.K.; Sharma, A.; Srivastava, M.; Yadav, B.; Singh, Y.; Sirohi, R.; Garg, S.K. Ameliorative potential of prepartal trace mineral and vitamin supplementation on parturition-induced redox balance and myeloperoxidase activity of periparturient sahiwal cows. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 177, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth-Szalai, Z.; Jakabfi-Csepregi, R.; Szirmay, B.; Ragán, D.; Simon, G.; Kovács-Ábrahám, Z.; Szabó, P.; Sipos, D.; Péterfalvi, Á.; Miseta, A.; Csontos, C.; et al. Serum total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and TAC/Lymphocyte ratio as promising predictive markers in COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Chia, M. Urinary total antioxidant capacity in soccer players. Acta Kinesiologica. 2009, 3, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ziobro, A.; Bartosz, G. A comparison of the total antioxidant capacity of some human body fluids. Cell. Mol. Biol Lett. 2003, 8, 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kosior, M.A.; Esposito, R.; Cocchia, N.; Piscopo, F.; Longobardi, V.; Cacciola, N.A.; Presicce, G.A.; Campanile, G.; Aardema, H.; Gasparrini, B. Seasonal variations in the metabolomic profile of the ovarian follicle components in Italian Mediterranean Buffaloes. Theriogenology 2023, 202, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyawoye, O.A.; Abdel-Gadir, A.; Garner, A.; Leonard, A.J.; Perrett, C.; Hardiman, P. The interaction between follicular fluid total antioxidant capacity; infertility and early reproductive outcomes during in vitro fertilization. Redox Rep. 2009, 14, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Choi, A.; Yu, H.Y.; Czerniak, S.M.; Holick, E.A.; Paolella, L.J.; Agarwal, A.; Combelles, C.M. Fluctuations in total antioxidant capacity; catalase activity and hydrogen peroxide levels of follicular fluid during bovine folliculogenesis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2011, 23, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.F.; Reinholz, N.; Ozçelik, T.; Leipert, B.; Gerlach, E. Uric acid as radical scavenger and antioxidant in the heart. Pflugers Arch. 1989, 415, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.M.; Aberdroth, R.E.; Hochstein, P. Inhibition of free radical-induced DNA damage by uric acid. FEBS Lett. 1984, 174, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, H.; Halliwell, B. Action of biologically-relevant oxidizing species upon uric acid. Identification of uric acid oxidation products. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1990, 73, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ialongo, C. Preanalytic of total antioxidant capacity assays performed in serum; plasma; urine and saliva. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 50, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Mann, T.; Sherins, R. Peroxidative breakdown of phospholipids in human spermatozoa; spermicidal properties of fatty acid peroxides; and protective action of seminal plasma. Fertil. Steril. 1979, 31, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetti, S.; Tagliamonte, M.C.; Catalani, S.; Primiterra, M.; Canestrari, F.; De Stefani, S.; Palini, S.; Bulletti, C. Differences in blood and semen oxidative status in fertile and infertile men; and their relationship with sperm quality. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2012, 25, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Vantman, D.; Ponce, J.; Escobar, J.; Lissi, E. Total antioxidant capacity of human seminal plasma. Hum. Reprod. 1996, 11, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosrowbeygi, A.; Zarghami, N. Levels of oxidative stress biomarkers in seminal plasma and their relationship with seminal parameters. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2007, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahune, P.P.; Choudhari, A.R.; Muley, P.A. The total antioxidant power of semen and its correlation with the fertility potential of human male subjects. J. Clin. Diagn Res. 2013, 7, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, F.; Valojerdi, M.R.; Amanlou, M.; Karimian, L.; Abolhassani, F. Relationship of seminal reactive nitrogen and oxygen species and total antioxidant capacity with sperm DNA fragmentation in infertile couples with normal and abnormal sperm parameters. Andrologia 2014, 46, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulini, S.; Sblendorio, V.; Xella, S.; La Marca, A.; Palmieri, B.; Volpe, A. Seminal plasma total antioxidant capacity and semen parameters in patients with varicocele. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2009, 18, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, C.; Serra, L.; El Balkhi, S.; Lefort, G.; Ramé, C.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Glyphosate presence in human sperm: First report and positive correlation with oxidative stress in an infertile French population. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 278, 116410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, R.A.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Nelson, D.R.; Thomas, A.J. Jr. Effect of cigarette smoking on levels of seminal oxidative stress in infertile men: a prospective study. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 78, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasihormozi, S.H.; Babapour, V.; Kouhkan, A.; Niasari Naslji, A.; Afraz, K.; Zolfaghary, Z.; Shahverdi, A.H. Stress hormone and oxidative stress biomarkers link obesity and diabetes with reduced fertility potential. Cell J. 2019, 21, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Said, T.M.; Kattal, N.; Sharma, R.K.; Sikka, S.C.; Thomas, A.J., Jr.; Mascha, E.; Agarwal, A. Enhanced chemiluminescence assay vs colorimetric assay for measurement of the total antioxidant capacity of human seminal plasma. J. Androl. 2003, 24, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakop, U.; Müller, K.; Müller, P.; Neuhauser, S.; Callealta Rodríguez, I.; Grunewald, S.; Schiller, J.; Engel, K.M. Seminal lipid profiling and antioxidant capacity: A species comparison. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0264675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürler, H.; Calisici, O.; Bollwein, H. Inter- and intra-individual variability of total antioxidant capacity of bovine seminal plasma and relationships with sperm quality before and after cryopreservation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 155, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, L.A.; Matás, C.; Torrecillas, A.; Saez, F.; Gadea, J. Seminal plasma components from fertile stallions involved in the epididymal sperm freezability. Andrology 2021, 9, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risso, A.; Pellegrino, F.J.; Corrada, Y.; Schinella, G. Evaluation of total antioxidant activity and oxidative stress in seminal plasma from dogs supplemented with fish oil and vitamin E. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 15, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Afrough, M.; Nikbakht, R.; Hashemitabar, M.; Ghalambaz, E.; Amirzadeh, S.; Zardkaf, A.; Adham, S.; Mehdipour, M.; Dorfeshan, P. Association of follicular fluid antioxidants activity with aging and in vitro fertilization outcome: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 18, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J.; Roman, S.D. Antioxidant systems and oxidative stress in the testes. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2008, 1, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernet, P.; Aitken, R.J.; Drevet, J.R. Antioxidant strategies in the epididymis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004, 216, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahiminejad, M.E.; Moaddab, A.; Ganji, M.; Eskandari, N.; Yepez, M.; Rabiee, S.; Wise, M.; Ruano, R.; Ranjbar, A. Oxidative stress biomarkers in endometrial secretions: A comparison between successful and unsuccessful in vitro fertilization cycles. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 116, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, E.H.; Lykke-Hartmann, K. Transcripts encoding free radical scavengers in human granulosa cells from primordial and primary ovarian follicles. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualotto, E.B.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Izzo, V.M.; Pinotti, J.A.; Joshi, N.J.; Rose, B.I. Effect of oxidative stress in follicular fluid on the outcome of assisted reproductive procedures. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 81, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H.; Nixon, B.; Café, S.L.; Aitken, R.J.; Bromfield, E.G.; Lord, T. Oxidative stress and in vitro ageing of the post-ovulatory oocyte: an update on recent advances in the field. Reproduction 2022, 164, F109–F124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, F.J.; Ortiz-Rodríguez, J.M.; Gaitskell-Phillips, G.L.; Gil, M.C.; Ortega-Ferrusola, C.; Martín-Cano, F.E. An integrated overview on the regulation of sperm metabolism (glycolysis-Krebs cycle-oxidative phosphorylation). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 246, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foutouhi, A.; Meyers, S. Comparative oxidative metabolism in mammalian sperm. Anim. Reprod Sci. 2022, 247, 107095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, Z.; Lambourne, S.R.; Aitken, R.J. The paradoxical relationship between stallion fertility and oxidative stress. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 91, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, Z.; Lambourne, S.R.; Curry, B.J.; Hall, S.E.; Aitken, R.J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase plays a pivotal role in the maintenance of stallion sperm motility. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.C.; Ford, W.C. The role of glucose in supporting motility and capacitation in human spermatozoa. J. Androl. 2001, 22, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hereng, T.H.; Elgstøen, K.B.; Cederkvist, F.H.; Eide, L.; Jahnsen, T.; Skålhegg, B.S.; Rosendal, K.R. Exogenous pyruvate accelerates glycolysis and promotes capacitation in human spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 3249–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).