Resumo

A indústria de ferramentas vem ano-a-ano desenvolvendo soluções que buscam incrementar a eficiência operacional. Nos canteiros de obra o consumo de recursos é objeto de atenção para a redução de custos para dar competitividade às unidades residenciais e comerciais, em um mercado cada vez mais exigente. Clientes e acionistas, além do preço da área construída e dos lucros oriundos do negócio, buscam valores tangíveis no que antes era tratado como qualitativo. A segurança já não se resume aos número de casos, mas é custo de afastamento de trabalhadores e de imagem. O prazo de entrega, já não é mais único para auferir eficiência; há que se fazer mais com menos. Receitas podem ser antecipadas e lucros ampliados se o planejado for realizado com tempo e energia menores. Tomando como exemplo um elementos típicos de suporte metálico da infraestrutura de utilidades (água, eletricidade, ar comprimido, gás entre outros), esse artigo demonstra o potencial expressivo de redução de consumo de eletricidade quando se opta pelo sistema modular em detrimento do convencional soldado, principalmente se considerado o uso de ferramentas à bateria. A opção por elementos fixados por parafusos, arruelas e porcas, reduz a complexidade da montagem com tempo 72% menor e massa de materiais até 83% menor, utilizando mão-de-obra em menor número e 42% mais barata. Com investimento em ferramental 1/5 a 1/3 menor que a solução convencional soldada, o trabalho se torna mais seguro e ergonômico. Graças à menor massa da estrutura, o sistema modular poupa atmosfera de emissões de CO2 no transporte em 50%, se comparado à solução tradicional.

Palavras-chaves: construção civil; eletricidade; modularidade; baterias; BIM; indústria

1. Introduction

According to recent studies, the construction industry is the largest value creator in the global economy. It alone accounts for 13% of global GDP, with an estimated $10 trillion spent annually on goods and services. It is highly labor-intensive, both directly and indirectly, employing approximately 220 million people worldwide.

Despite its numerical strength, the construction industry's weakness is productivity. Compared to other sectors of the economy, construction has low productivity. Over the past 20 years, the industry has grown by only 1% per year, while other industries have grown by an average of 3.6% per year and the global economy by 2.8% per year. The potential for productivity gains is estimated at $1.6 trillion, or a 2% increase in global GDP.

In terms of energy consumption, the sector will consume 39% of the fossil energy generated in 2023. And this demand is growing at a rate of 4% per year since 2021, the highest growth rate since 2011.

The main player in this construction scenario is China, followed by the US and India. China alone accounts for 40.8% of the market value in 2022, and together with the US and India, will account for 57% of the total growth of the sector by 2030.

The current scenario demands change from the sector, both financially and environmentally. And a powerful driver for achieving results is governance. Whether it's a project or an operation, ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) management has demanded clear commitments to a low carbon footprint, biodiversity, circularity, lower waste emissions, occupational safety, process standardization, modularity, digitalization, modularity, mobility, skills training and much more. This framework of challenges may seem like a problem, but from the perspective of a better business environment, it is certainly a great opportunity to increase return on investment (ROI), mitigate the negative effects of logistics and inflation, create better paid and more efficient jobs, and above all, make the environment and people safer.

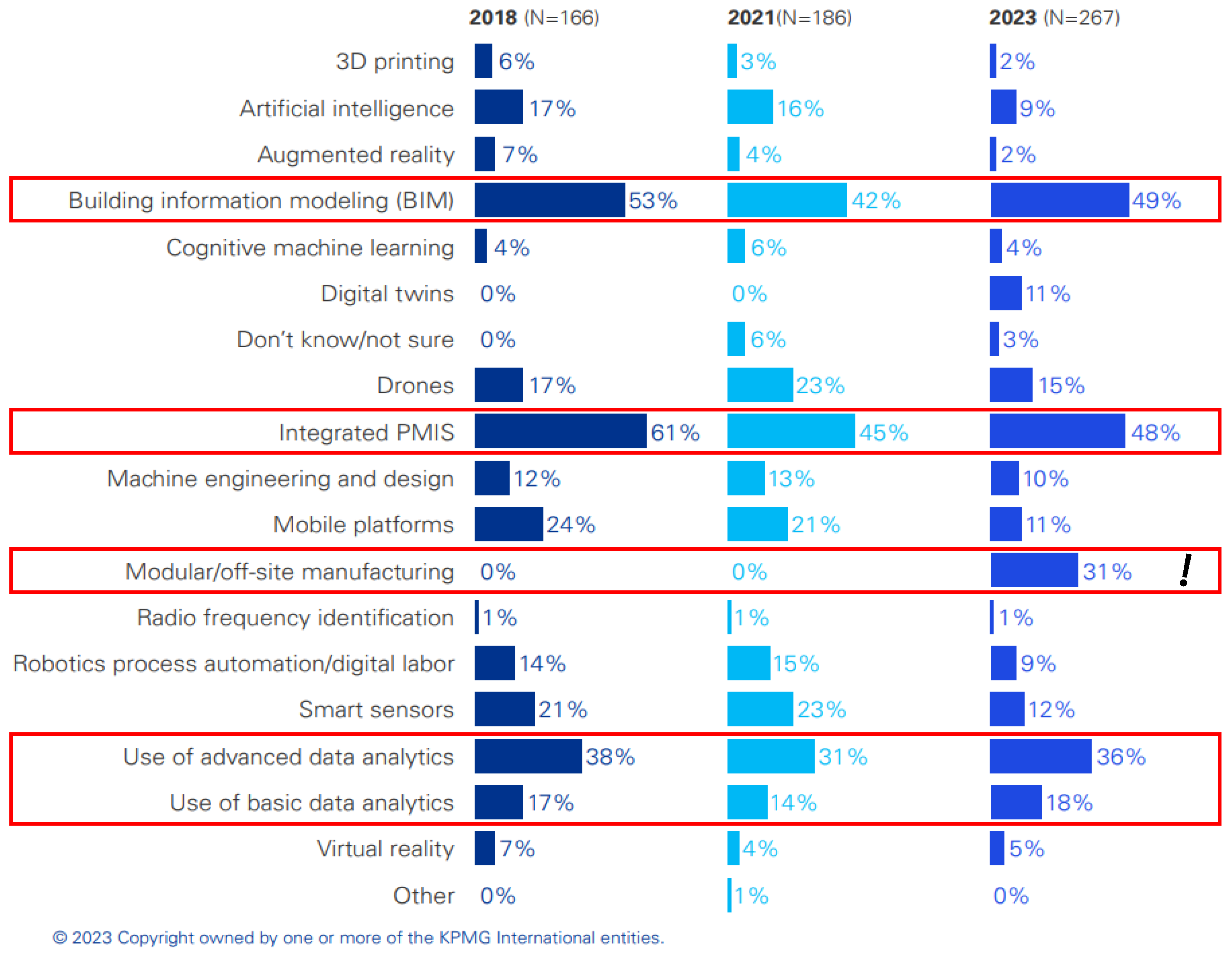

In a project launched in 2017, consulting firm KPMG conducts an annual global survey of the construction industry, looking at the major global players in the sector and where they are investing resources in technology to evolve their businesses (KPMG, 2023). In the last 3 editions, the adoption of Project Management Information System (PMIS), Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Data Analytics stands out, the latter suggesting a real concern for performance. These 3 (three) technologies seem to persist over the years, and any fluctuations can be explained by seasonality and the stage of each project at the time of the surveys. But what really stands out is the use of modularity technology, or off-site construction. As shown in

Figure 1, the 2023 survey indicates that the values embedded in this technology, such as safety, speed of construction, flexibility of assembly and maintenance, and performance, are already beginning to be understood by business decision makers.

The scientific world has confirmed the paradigm shift away from the old ways of construction and towards technological innovation. In his article, the author Zhao et al. makes a comparison between the current primary education and the need to address issues of entrepreneurship and innovation, and higher education in civil engineering. The change in the technological level will only be possible if the training of engineering operators is made aware of the interconnection between environmental, economic and social needs (ZHAO; ZHANG; WANG, 2018). Soliman adds that innovations in materials and technologies are the tools for engineers to achieve significant results in reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions. Based on this knowledge, designers can use the correct selection of materials, their formulations, life cycle analysis, available construction techniques, and other variables to feed models that can predict results that can be compared with old practices (SOLIMAN et al., 2022). Using the case of workers constructing drywall as an example, Hasan et al. applied an event processing model (EPM) that uses multiple monitoring technologies in parallel and a set of algorithms to interpret data from multiple streams for operations control. The results suggest that collecting, fusing, and interpreting multiple data streams using a system of multiple on-site monitoring technologies can provide more complete and accurate information about the status of the project than can be obtained using any single technology. In other words, you get the essentials for automating project progress monitoring, which is important for automating production planning and control tasks (HASAN; SACKS, 2023).

Even the use of cordless tools has been the subject of academic study to understand the competitive advantages between corded and cordless technologies and the manufacturer brands that offer them in the marketplace. Ghena et al. examined the predicament of the premium brands and products available and identified a sustainable competitive advantage, whether for manufacturers or users. The result was the need to implement quality methodologies to design and manufacture products that meet the ever-increasing demands of customers. It is also necessary to use forecasting methods in order to be able to adapt the organization's strategies and objectives at the right time, at the risk of falling short of what is required by the market (GHENA; IAMANDI; GHICULESCU, 2022).

Modularity, as a way to optimize the construction of structures regardless of the loads involved, is also the subject of academic research that seeks to answer questions about safety, productivity, environmental impact, and economic viability. In a 2019 article, the authors Innella discuss the implementation of lean techniques in the modular construction industry, including all stages of the production process (i.e., design, manufacturing, transportation, field assembly, and supply chain) through a systematic review. In addition, the article provides a chronological and comprehensive review of lean methods and tools in manufacturing and traditional construction industries to further explore the interface between lean and modular construction (INNELLA; ARASHPOUR; BAI, 2019). By reading it, practitioners can gain an overview of lean strategies and their associated potential benefits and obstacles for future case studies.

Despite the abundance of material found on the paths taken by the construction sector, especially in residential and commercial projects, no case studies were found for industrial infrastructure. The construction industry is also active in industries such as oil and gas, chemicals and petrochemicals, power generation and distribution, food, automotive, and others, building facilities whose specific needs and constraints require the use of more efficient solutions. The vendors of these solutions have their own special marketing campaigns, but they don't provide case studies and/or technical and economic comparisons to help people decide whether or not to use a particular technology.

2. Objective

This article aims to encourage decision-makers to measure the social, financial, environmental and image impact of using new technologies compared to the usual practices used in industrial infrastructure works carried out by construction companies.

3. Methodology

In line with the market's perception that modularity, greater work efficiency, safety, and reduced energy consumption and emissions are the drivers that can guide technological change, the author looked within the factory infrastructure construction to find a construction model that is still widely used in utility projects in industrial plants and that definitely does not meet today's expectations, and whose functionality is already compromised by limitations in assembly and maintenance.

3.1. Design Model – Materials, Specifications, Assembly and Maintenance

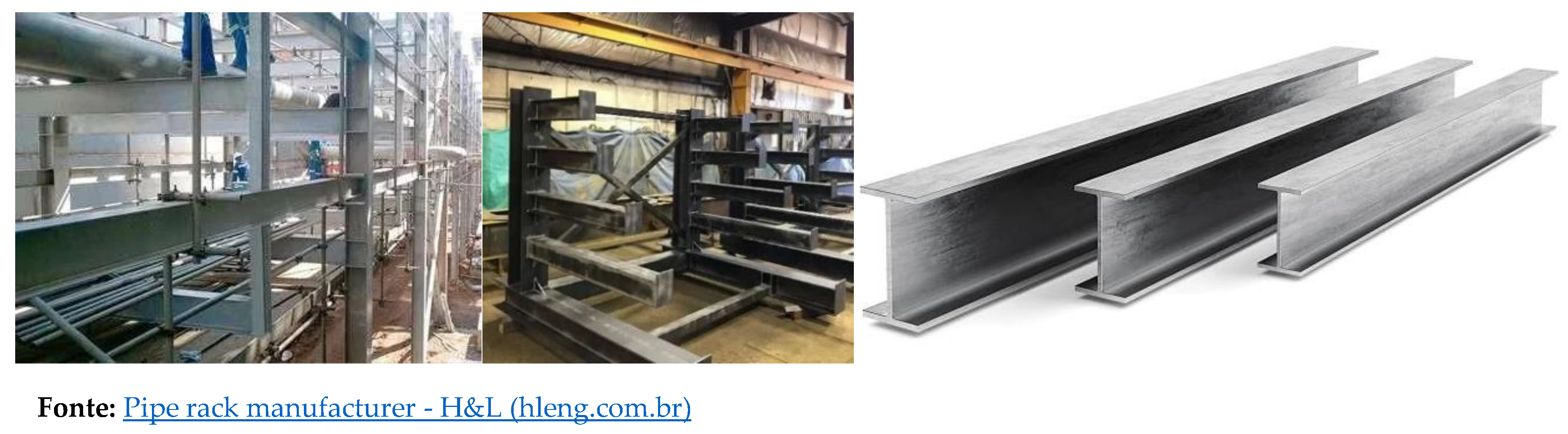

There are still many old practices used in the construction industry, and one in particular that attracts a lot of attention is the metal structure model for supporting pipes, cables and electrical fittings, based on welded carbon steel profiles (see

Figure 2). Very heavy in itself, generally many times the mass it is supposed to support, it is very labor- and energy-intensive, costly to manufacture and maintain, and presents many hazards that compromise safety in the workplace.

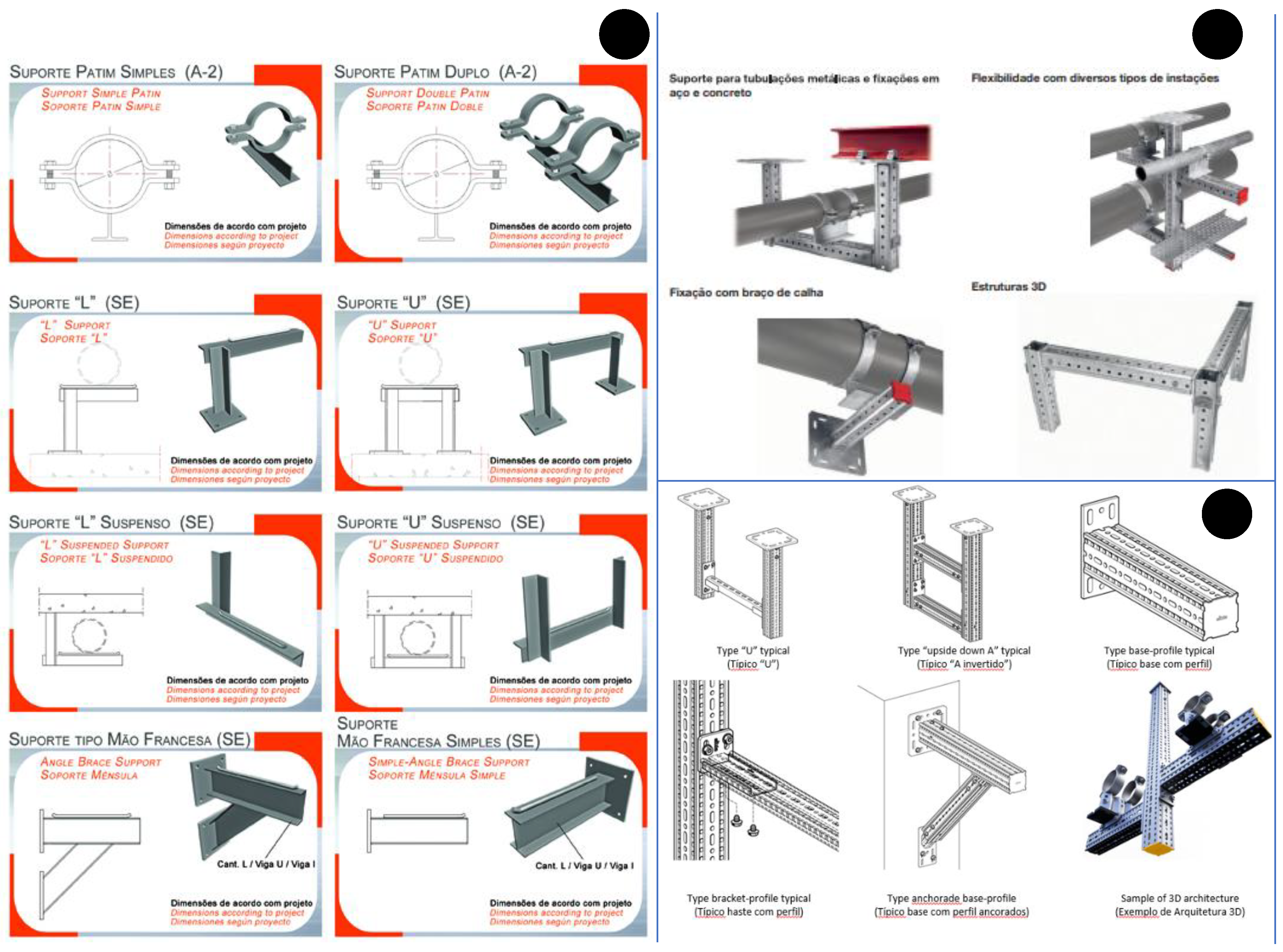

On the other hand, it is already possible to find a modular structure solution on the market (see

Figure 3), which uses alloy profiles, sized according to the project, lighter, assembled with screwed elements, with lower electricity and labor consumption, easy to maintain, and whose modularity offers speed and safety in assembly.

The design of structures to support utilities such as water, electricity, steam, gas, compressed air, and others is approached from the point of view of the support that is repeated along the length of a utility supply line, or simply what is known as a TYPICAL. To illustrate the different types used in support projects,

Figure 4 shows the most common examples found in industrial plants.

Made from steel sections manufactured by the steel industry, the structures are very heavy, lack surface protection and therefore do not guarantee performance in inclement weather, require surface covering (i.e. painting), cutting to size is time consuming, and assembly/disassembly/maintenance depends on a lot of welding and skilled labor (i.e. welders).

The modular structure, on the other hand, is supplied by manufacturers using alloy steel profiles, which are lighter, guaranteed for use in bad weather, already dimensioned according to the project, without the need for painting, ready-to-use bolted connections (i.e. no welding), assembly work with light and portable tools and, above all, elements made available for the BIM environment, making projects more flexible, faster, leaner and more competitive.

Unlike the heavy and power-hungry tools such as arc welders, band saws and air compressors for spray guns used by locksmiths and boilermakers, the modular system, which does not require welders and painters, allows assemblers to eliminate corded power tools and replace them with battery-powered cordless tools. Portable, compact, lightweight, fast-charging and low-current, their energy consumption is significantly lower than that of the conventional support system.

Table 1 below provides technical information on the tools for comparison and calculation of estimated power consumption per hour of use.

Modular system manufacturers provide comparisons of typical assembly times on their websites and on the YouTube video platform.

Table 2 shows the comparative assembly times for modular and conventional welded systems. In order to provide a neutral reference for the time and motion analysis, a range of potential mass and labor reductions are used for the competitiveness calculations.

3.2. Manpower – Skills, Rates, Availability and Cost

Another important factor in the competitiveness of the modular solution, in addition to the lighter and more mobile tools thanks to battery power, is labor. The type or qualification of the operators, the quantity required to perform the work, as well as its availability on the market and its impact on the value, is a determining factor in the competitiveness of the solution. As shown in the evaluation of work execution times for the construction of the most common shapes,

Table 3 below presents practical comparisons found on a daily basis, as well as the presentation of technologies by manufacturers on the market.

While conventional welded structures require specialists in welding, assembly and painting, modular structures require only assemblers to get them up and running. Conventional structures often use carbon steel profiles that require painting to protect them. Modular structures, on the other hand, are constructed from metal alloy profiles, giving them a much higher mechanical strength-to-weight ratio and unparalleled chemical surface resistance.

The competitiveness of the modular solution can also be seen in the cost of the labor required to assemble it. Compared to the conventional welded solution, the absence of painters and welders means that the variable labor costs can be significantly reduced.

Table 4 shows the market values for the required trades.

3.3. Sustainability – Manufacturing and Transportation Carbon Emissions

Using the financial, social and environmental tripod as a reference, the sustainability of the modular model can be measured. The financial and social aspects already mentioned are guaranteed by the data already presented, whether they contribute positively or negatively.

The environmental aspect, on the other hand, can be compared and measured according to the carbon emissions found in the literature. In addition to the emissions recorded in the production of raw materials, whether carbon steel or a structural alloy, freight is an important factor, since the transport of the mass of material from the hatchery to the installation on site emits carbon through the burning of fossil fuels in transport.

The steel sector accounts for approximately 7-9% of global CO2 emissions (IEA, 2020). The main focus of emissions is due to the sector's high energy intensity and its reliance on fossil carbon sources to provide energy and as an input for iron oxide reduction. The global average carbon intensity of steel is 1.91 t CO2/t crude steel. As with many other products, Life Cycle Inventories (LCIs) can be used to estimate the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their production chains. These assessments are based on standards and methodologies, including the GHG Protocol, which has been in operation since the 1990s and is an international benchmark for the development of methodologies and standardizations for quantifying corporate emissions (GHG, 2023). In particular, there are specific carbon inventory standards for steel production in ISO 14404:2013 (ISO, 2013).

Freight is a major variable in the global economy. Every year, billions of tons of products are transported around the world by trucks, planes, ships and trains. Transportation accounts for up to 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and up to 11% if warehouses and ports are included (GREENE, 2020). In economically developing regions such as Asia, Africa and Latin America, global freight demand is expected to triple by 2050, resulting in a doubling of emissions (OECD, 2023). Even if other sectors of the economy reduce their emissions by reducing the use of fossil fuels, business as usual will keep transport as the largest emitter of greenhouse gases by 2050 (IPCC, 2022). It is possible to quantify GHG emissions in transportation, as shown in equation I (MATHERS, 2015). As shown below, the emission is a directly proportional function of the mass to be transported, i.e. lighter loads contribute to reducing the impact on the atmosphere for the same mode of transport.

Where:

− GGE is the calculated GHG emission (in g CO2 eq)

− D is the distance to be transported (in km or miles)

− W is the mass to be transported (in kg or t)

− EF is the emission factor of the chosen mode of transport (in g/t.km)

The result is also a direct function of the type of transport mode chosen, as shown in

Table 5. Compared to rail, road transport emits 14 times more CO

2 per ton transported in km.

4. Results and Discussions

When it comes to

ASSEMBLY, the use of less energy-intensive, lighter and more portable equipment puts the worker and the work itself in a much more efficient position than conventional practices, if best practices in occupational health and safety are followed. While in the system with robust profiles the handling of parts is unhealthy due to the heavy mass and time-consuming cuts, the modular system is positioned with significantly less mass and parts with optimized designs, assembled with very light and portable tools. According to the references shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Table 1 and

Table 2, depending on the type of building to be constructed, regardless of the system supplier, the

MASS of the structure can be reduced by more than 80% when assembled with equipment weighing no more than 1 kg, whereas in the traditional system the machines weigh between 80 and 300 kg.

The significantly lower assembly masses, combined with the concept, bring speed to project delivery. In the cases shown in Error! Reference source not found., the TIME of assembly has been reduced by between 50 and 87% in the preparation, pre-assembly and on-site assembly phases, not to mention the painting and periodic maintenance of the welded system, which has no self-protection against the weather.

It is worth noting that the modular model can support the same load with significantly less structural mass than the traditional system, which is often much heavier than the utilities it supports.

LABOR is an important factor when evaluating a project and plays a significant role in the feasibility of choosing a particular technology. Availability and cost are factors that are not only interdependent, but must be pursued in the quest for competitiveness. In addition, they can be closely related to the complexity and execution time of certain tasks. In the specific case of the comparison between conventional and modular systems, as shown in

Error! Reference source not found., the former has to master the technique, i.e. welding, and the time-consuming task of painting. The modular system, on the other hand, not only has a smaller number of professionals because it doesn't have painting, but it also has assembly skills. This is important, but the technical skills are less complex. They are much more abundant on the market, more versatile and faster by the very nature of the task, and more efficient when using lightweight, portable, battery-powered tools. Looking at the cost of the professionals required for each system (see

Table 4), according to the latest market benchmark, a welder costs between 32 and 41% more than a fitter. A painter, who is required to apply protective paint to the finished and/or repaired surface, costs 8% more than an assembler. When comparing the typical structural and skill requirements for the conventional and modular systems described in

Table 3, the assembler-welder-painter team for the former costs 57 to 61% more than the assembler-only team for the latter.

Another important factor in the decision to switch from one technology to another is

ENERGY consumption. Renewable or not, it has heterogeneous local availability, and globally its cost has historically increased. In Brazil, for example, energy costs are thought to be responsible for the negligible growth of 0.7% in the industrial sector's GDP between 2000 and 2021 (DE FREITAS, 2023). Reducing the energy intensity of operations is therefore the order of the day in project management. Considering the equipment involved in the production of welded and modular structures, as well as the time and motion overview shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively, it is possible to theoretically estimate the electricity consumption of the welding equipment and the battery charge required to assemble the bolted parts. Considering that in the conventional system the welder is the tool used to assemble the structure, and in the modular system the battery-powered screwdriver is the tool of choice, the power consumption of the latter is less than 0.4% of that of the former.

Once it has been verified that the modularity, despite the change in the profile of the professional requirement, maintains the worker's need, and that the economic viability is due to the potential reduction in the worker's variable costs and in the demand for electricity, the social and financial variables for demonstrating SUSTAINABILITY in the change of technologies are satisfied. Once the third variable of the tripod is satisfied, the environmental variable must be considered. Here, in order to simplify the relative comparison, the author chose the amount of raw material used for the supports in each technology and the road freight to estimate the carbon emissions in the atmosphere resulting from the production of the amount of steel needed and its transportation. A more detailed assessment could consider the emissions associated with the production of the electricity required in each model, which would require taking into account the energy matrix of the site being analyzed. Or, at the technical extreme, a Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) to arrive at a value closer to the GHG and other environmental impacts, which is definitely outside the scope of this work.

However, knowing that the modular system has on average half the mass (W) of the conventional equivalent, and since GHG emissions are a direct function of the mass transported by the chosen mode, and assuming that the distance (D) and the emission factor (EF) are the same for both, the emission of the bolted model is 50% of that of the welded one, as shown below:

If the same distance (D) is considered for both technologies, then equations II and III result in IV:

Knowing that the average mass ratio between modular and conventional models is 50%, we have:

The equality in VI means that the emissions of the modular solution are half of the emissions of the conventional solution:

INVESTMENT is another important factor that can contribute to the decision to change technology. As shown in

Table 1, when comparing a battery-powered screwdriver for modular assembly with a welding machine for conventional assembly, and taking into account the range of brands and prices of both on the market, the investment in the former is 32% of that required for the latter. Taking into account the need for painting, which requires the purchase of an air compressor, this relative investment for the modular solution is reduced to 20%. In short, the investment in equipment for the modular system is between 1/5 and 1/3 of that for the heavy equipment of the welding and painting solution.

5. Conclusion

There are opportunities for the construction industry to promote innovations with multiple benefits. The aim of this work is to encourage the analysis of opportunities and assess their impact. It's not just a question of defending innovation for innovation's sake, because we have to consider the safety and well-being of workers, the environment and work efficiency, which is directly reflected in the financial health of a project. In

Table 6, the specific case of industrial metal structures supporting production utilities, it can be seen that there are significant gains in changing the status quo.

Another important variable to stimulate the analysis of opportunities for technology substitution, the concept of ESG, is already consolidated in the market and is a differentiating factor in the acquisition and supply of products and services. Therefore, in addition to the improvement of the working environment, the reduction of environmental impact, the efficiency in the execution and use of resources, and the optimization of costs, the growth and sustainability of companies depend on the initiative to compare the new with the traditional.

References

- CAGED; E-SOCIAL; EMPREGADOR WEB. Construção Civil - Salários 2024, Tabela Salarial, Quanto Ganh. Available online: https://www.salario.com.br/tabela-salarial/construcao-civil/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

-

De Freitas, F.G. Elevação do custo da energia continua a restringir o crescimento econômico e a expansão da produção industrial Editora Brasil Energia. Available online: https://brasilenergia.com.br/energia/elevacao-do-custo-da-energia-continua-a-restringir-o-crescimento-economico-e-a-expansao-da-producao-industrial (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Ghena, M.-F.; Iamandi, A.-M.; Ghiculescu, L.-D. Ghena, M.-F.; Iamandi, A.-M.; Ghiculescu, L.-D. Methods used to gain a competitive advantage in the power tool industry. Acta Tech. Napoc. 2022, 65, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar]

- GHG. About Us GHG Protocol. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/about-us (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Greene, S. Freight Transportation MIT Climate Portal. Available online: https://climate.mit.edu/explainers/freight-transportation (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Hasan, S.; Sacks, R. Integrating BIM and Multiple Construction Monitoring Technologies for Acquisition of Project Status Information. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Iron and Steel Technology Roadmap – Analysis - IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/iron-and-steel-technology-roadmap (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Innella, F.; Arashpour, M.; Bai, Y. Lean Methodologies and Techniques for Modular Construction: Chronological and Critical Review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5°C in the Context of Sustainable Development. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, p. IPCC. Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5°C in the Context of Sustainable Development. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, p. 93–174, 24 maio 2022.

- ISO. ISO 14404-1:2013 - Calculation Method of Carbon Dioxide Emission Intensity from Iron and Steel Production — Part 1: Steel Plant with Blast Furnace. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/57298.html (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- KPMG. Familiar Challenges-New Approaches. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2023/05/2023-global-construction-survey.html (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- MATHERS, J. Green Freight Math: How to Calculate Emissions for a Truck Move. Environmental Defense Fund, 2015. Available online: https://business.edf.org/insights/green-freight-math-how-to-calculate-emissions-for-a-truck-move (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- OECD. OECD. Regional; Rural and Urban Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/regional-rural-and-urban-development.html (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Regmi, M.; Hanaoka, S. A framework to evaluate carbon emissions from freight transport and policies to reduce CO2 emissions through mode shift in Asia. The 3rd International Conference on Transportation and Logistics (T-LOG 2010), p. 1–16, 2010.

- Soliman, A.; et al. Innovative construction material technologies for sustainable and resilient civil infrastructure. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Cognition and system construction of civil engineering innovation and entrepreneurship system in emerging engineering education. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2018, 52, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

More

More

Less

Less