Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vehicle Washing Facility

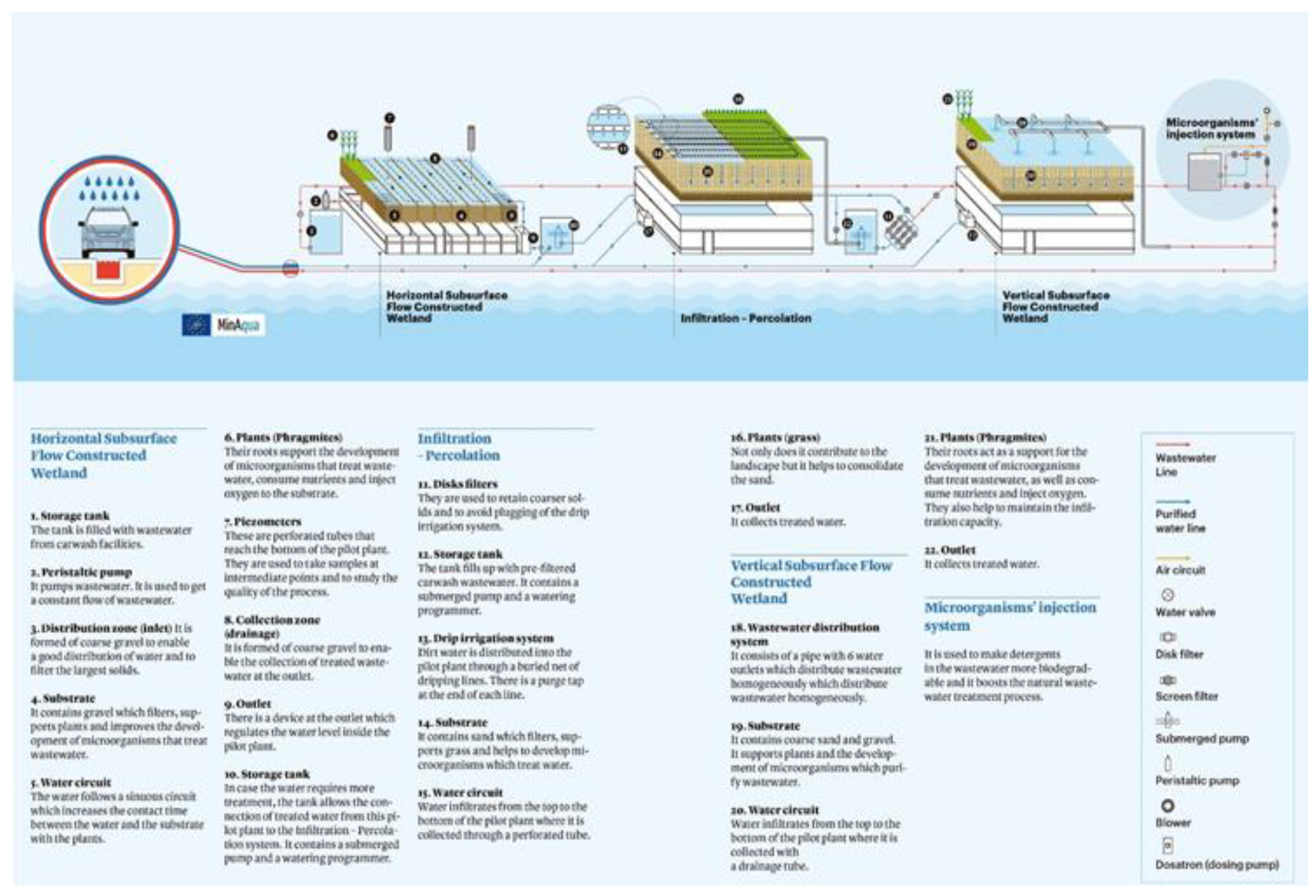

2.2. Nature-Based Solution Pilots

2.2.1. Monitoring of NBS Pilot Plants

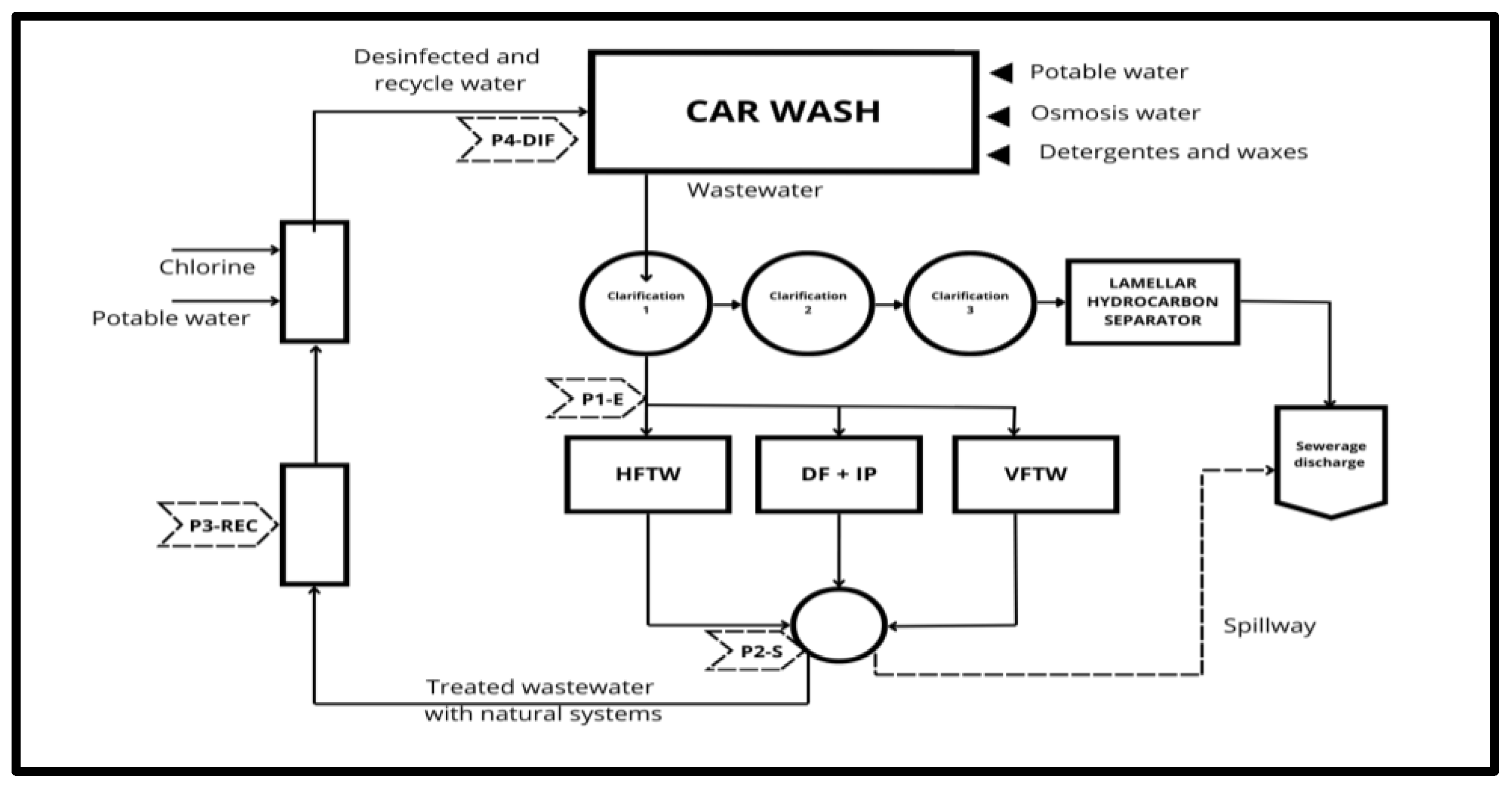

2.3. Water Recycling System

2.3.1. Monitoring of Water Recycling System

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Vehicle Washing Facility Wastewater Quality

3.2. Nature-Based Solutions Performance

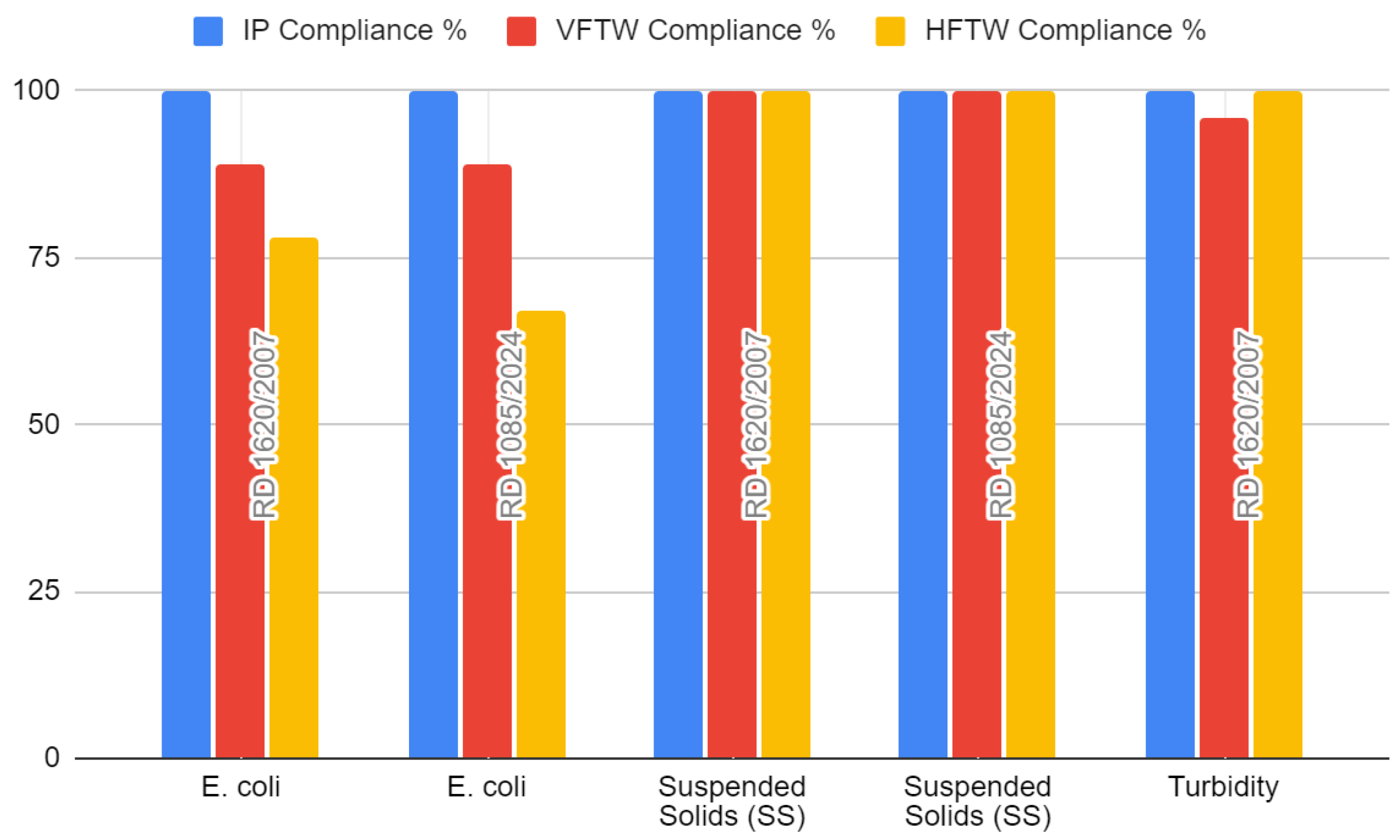

3.2.1. Effluent Quality

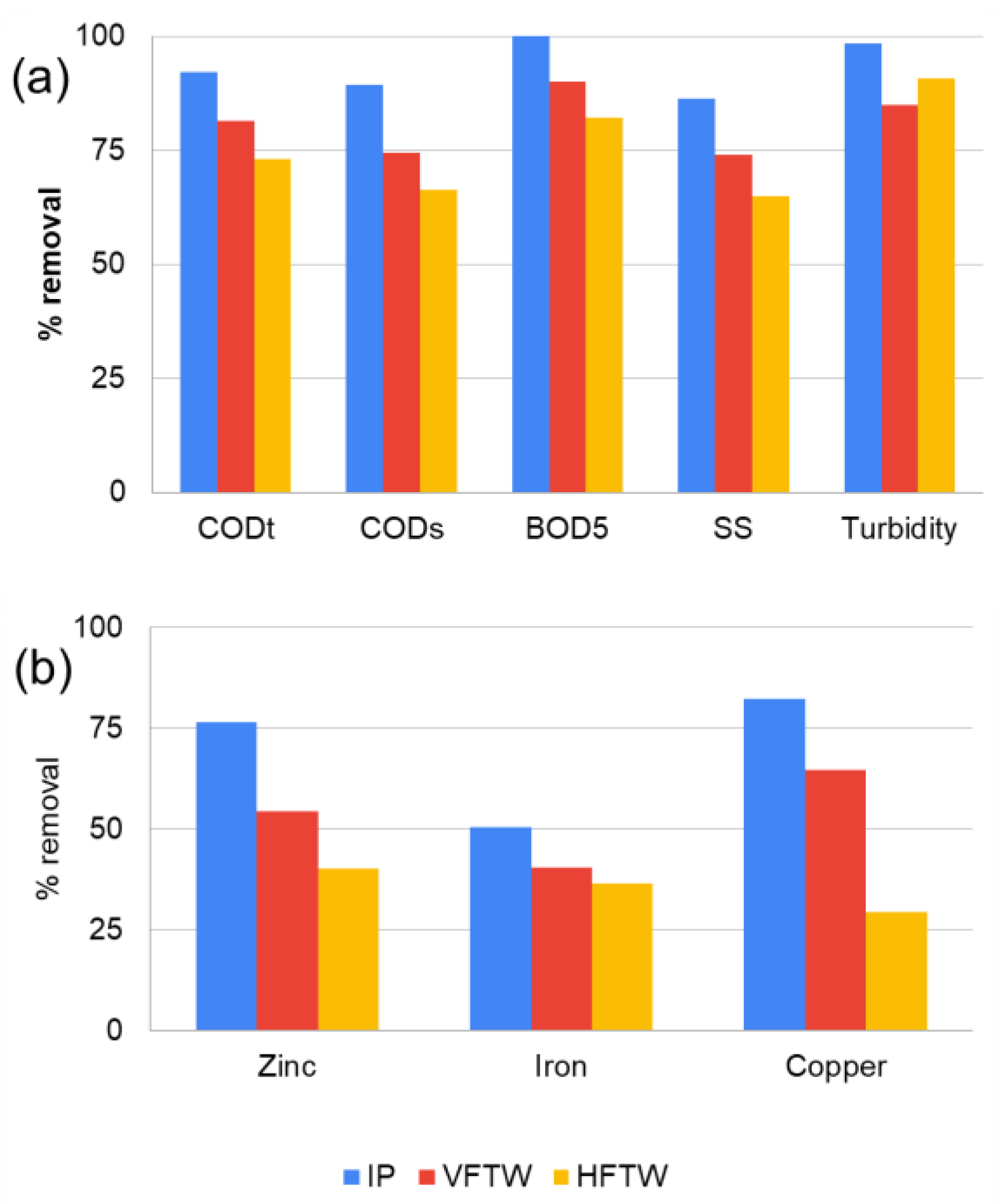

3.2.2. Pollutant Removal Efficiency

3.2.3. Recycling Capacity of the Nature-Based Solutions

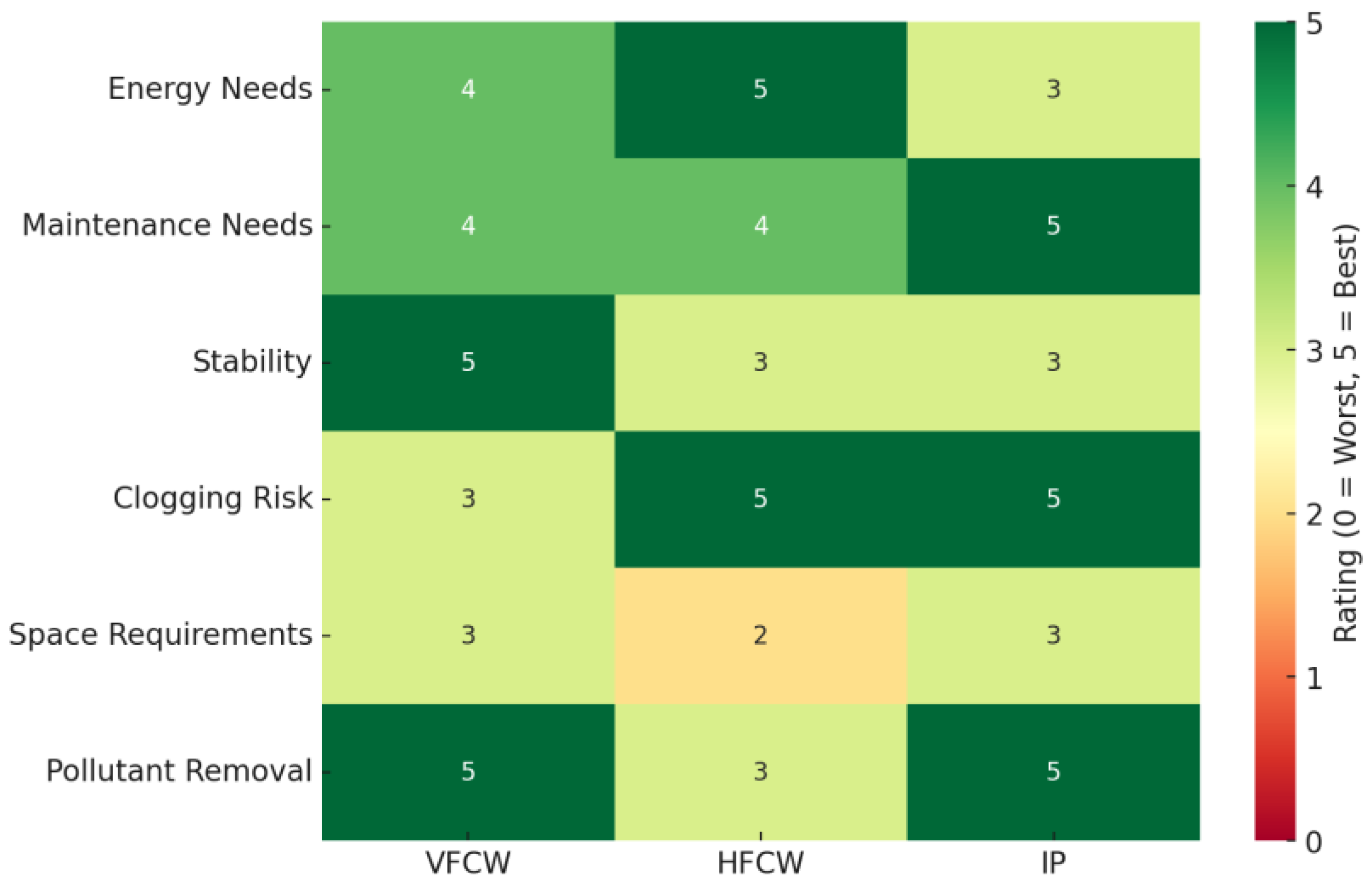

3.3. Sustainability, System Scaling, and Comparative Performance

3.3.1. Area Requirements and Hydraulic Loads

3.3.2. System Sustainability and Maintenance

3.3.3. Comparative Analysis and Recommendations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torrens, A., Aulinas, M., Folch, M., & Salgot, M. Recycling of carwash effluents treated with subsurface flow constructed wetlands. In Constructed Wetlands for Industrial Wastewater Treatment; A. Stefanakis, Ed.; Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2018; pp. 469-492. [CrossRef]

- Gönder, Z. B., Balcıoğlu, G., Vergili, I., & Kaya, Y. An integrated electrocoagulation–nanofiltration process for carwash wastewater reuse. Chemosphere, 2020, Vol. 253, p. 126713. [CrossRef]

- Kashi, G., Younesi, S., Heidary, A., Akbarishahabi, Z., Kavianpour, B., & Kalantary, R. R. Carwash wastewater treatment using chemical processes. Water Science and Technology, 2021, Vol. 84(1), p. 16-26. [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M., Ahmad, W., & Khan, H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons removal from vehicle-wash wastewater using activated char. Desalination and Water Treatment, 2021, Vol. 236, p. 55-68. [CrossRef]

- Sarmadi, M., Foroughi, M., Najafi Saleh, H., Sanaei, D., Zarei, A. A., Ghahrchi, M., & Bazrafshan, E. Efficient technologies for carwash wastewater treatment: A systematic review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2020, Vol. 27(28), p. 35448-35459. [CrossRef]

- Aulinas, M., Folch, M., Torrens, A., & Salgot, M. (2016). Good Practices Guide for Car Wash Installations. Grup Fundació Ramon Noguera, in collaboration with Consorci Life MinAqua. Legal deposit: GI 1485-2016.

- Ajibode, O. M., Rock, C., Bright, K., McLain, J. T., Gerba, C. P., & Pepper, I. L. Influence of residence time of reclaimed water within distribution systems on water quality. Journal of Water Reuse and Desalination, 2013, Vol. 3(3), p. 185–196. [CrossRef]

- Castellar, J. A. C., Torrens, A., Buttiglieri, G., Monclús, H., Arias, C. A., Carvalho, P. N., Galvao, A., & Comas, J. Nature-based solutions coupled with advanced technologies: An opportunity for decentralized water reuse in cities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022, Vol. 340, 130660. [CrossRef]

- Torrens, A., de La Varga, D., Ndiaye, A. K., Folch, M., & Coly, A. Innovative multistage constructed wetland for municipal wastewater treatment and reuse for agriculture in Senegal. Water, 2020, Vol.12(11), 3139. [CrossRef]

- Bali, M., Gueddari, M., & Boukchina, R. Treatment of secondary wastewater effluents by infiltration percolation. Desalination, 2010, Vol. 258(1–3), 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S. O., Vieira dos Santos, E., Tossi de Araújo Costa, E. C., & Martínez-Huitle, C. A. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes (EAOPs) as alternative treatment techniques for carwash wastewater reclamation. Chemosphere, 2018, Vol.211, p.998-1006. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z., Ma, H., & Zhang, L. Carwash wastewater quality and treatment: A review. Environmental Technology Reviews, 2021, Vol. 10(1), p. 1-20.

- Bakare, B. F., Mtsweni, S., & Rathilal, S. Characteristics of greywater from different sources within households in a community in Durban, South Africa. Journal of Water Reuse and Desalination, 2017, Vol. 7(4), p. 520–528. [CrossRef]

- Zaneti, R. N., Etchepare, R., & Rubio, J. (2013). Constructed wetlands and water recycling in car wash facilities. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 2013, Vol.1, p.31-40. [CrossRef]

- Blanky, M., Rodríguez-Martínez, S., Halpern, M., & Friedler, E. Legionella pneumophila: From potable water to treated greywater; quantification and removal during treatment. Science of The Total Environment, 2015, Vol.533, p. 557-565. [CrossRef]

- Dotro, G., Langergraber, G., Molle, P., Nivala, J., Puigagut, J., Stein, O., & von Sperling, M. (2017). Treatment Wetlands. IWA Publishing, Volume 16. ISBN electronic: 9781780408774. [CrossRef]

- Kadlec, R. H., & Wallace, S. D. Treatment Wetlands, 2nd ed.; CRC Press. 2008. ISBN: 978-1-56670-526-4.

- Vymazal, J., & Březinová, T.. The use of constructed wetlands for removal of pesticides from agricultural runoff and drainage: a review. Environmental International, 2015, 75, 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Decree 130/2003, of 13 May, approving the Regulation of public sanitation services. Catalunya Government, 2003.

- Royal Decree-Law 606/2003, of May 23, amending Royal Decree 849/1986, of April 11, approving the Regulation of the Public Hydraulic Domain, which Develops Preliminary Titles, I, IV, V, VI and VIII of Law 29/1985. Official State Gazette (BOE),2003.

- Royal Decree 1620/2007, of December 7, establishing the legal regime for the reuse of treated water. Official State Gazette (BOE), 294, 50639-50661.

- Royal Decree 1085/2024, of October 22, by which the Water reuse regulation and several regulations are modified decrees that regulate water management. Official State Gazette (BOE), 256, 2024.

- Knox, A. S., Paller, M. H., Seaman, J. C., Mayer, J., & Nicholson, C. Removal, distribution, and retention of metals in a constructed wetland over 20 years. Science of The Total Environment, 2021, Vol. 796, p.149062. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Nature-based Solutions Pilot Plants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IP | HFTW | VFTW | |

| Pre-treatment | 4 disk filters (120 mesh) installed in parallel | - | - |

| Feeding system | Submerged pump (activated by a timer) feeding from accumulation tank | - | - |

| Distribution system | 8 pipelines with 2.3 l/h self-compensating and heat-sealed drips are distributed. Subsurface drip irrigation systems, at 10 cm from the surface and separated 40 cm between lines and 30 cm between emitters |

Inlet (25-40 mm gravel; 1 m length of this gravel is placed in the inlet zone) | Overground pipeline with 6 outlets |

| Container | Built in steel | Built in steel; interior compartments of 2 x 0.6 m every 0.6 m | Built in steel |

| Size | Container total surface: 10.58 m2 Total length: 4.6 m Total width: 2.3 m Height: 1.3 m |

Pilot total surface: 10.58 m2 Total pilot length: 4.6 m Total pilot width: 2.3 m Height: 0.6 m |

Container total surface: 10.58 m2 Total length: 4.6 m Total width: 2.3 m Height: 1.3 m |

| Filtering material | Calibrated sand 0-3 mm, 1 m (d10: 0.30 – 0.40 mm; CU: 2-3; fines content < 3%) | Filtering zone (12-18mm gravel) | Two layers of filtering material: - Top layer of calibrated fine sand (d10: 0.23; CU: 3.2; fines content < 3%) 0.40 m height - Bottom layer of fine gravel (2-8 mm) 0.50 m height |

| Draining material | Transition layer 0.10 m (7-12 and 3-7mm mixed gravel) Draining layer 0.20 m (25-40 mm gravel) | Outlet areas (25-40 mm gravel; 0,5 m length in the outlet zone) | Transition layer 0.1 m (7-12 mm gravel) Draining layer 0.2 m (25-40 mm gravel) |

| Vegetation | Grass: seed mix Zulueta Compact (10% Lolium perenne, 5% Poa pratense and 85% Festuca arundinacea) |

Phragmites australis | Phragmites australis |

| Outlet structure | PVC 1 ½ pipeline with 1” brass tap for sampling and outlet pipe | Adjustable pipe for water level control | PVC Pipeline |

| Parameters | Units | n | Average (whole period) |

Max | Min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | ºC | 67 | 18.7 | 27.8 | 9.5 | |

| pH | 67 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 6.7 | ||

| Redox | mV | 67 | 86.2 | 225 | -47 | |

| EC | µS/cm | 67 | 548 | 1259 | 179 | |

| DO | mg/L | 67 | 0.9 | 5.9 | 0.0 | |

| Turbidity | FNU | 67 | 114 | 265 | 33.8 | |

| COD | mg/L | 66 | 71.6 | 438 | bdl | |

| dCOD | mg/L | 66 | 32.4 | 190 | bdl | |

| pCOD | mg/L | 66 | 41.3 | 346 | 5.0 | |

| BOD5 | mg/L | 66 | 18.8 | 70 | bdl | |

| SS | mg/L | 66 | 63.8 | 421 | bdl | |

| VSS | mg/L | 31 | 25.6 | 210 | bdl | |

| TKN | mg/L | 31 | 3.8 | 34.2 | bdl | |

| N-NO3- | mg/L | 31 | 2.1 | 14.8 | bdl | |

| N-NH4+ | mg/L | 31 | 0.6 | 3.3 | bdl | |

| P-PO43- | mg/L | 31 | 0.7 | 6.5 | bdl | |

| S-SO42- | mg/L | 15 | 48.7 | 157 | 31.8 | |

| Cl- | mg/L | 15 | 51.5 | 250 | 20.1 | |

| Ca2+ | mg/L | 15 | 59.6 | 79.2 | 50.6 | |

| Mg2+ | mg/L | 15 | 9.8 | 12.5 | 8.5 | |

| Alkalinity | mg/L CaCO3 | 32 | 174 | 239 | 58.1 | |

| Anionic surfactants | mg/L | 32 | ild | 0.9 | bdl | |

| Cationic surfactants | mg/L | 32 | ild | 0.4 | bdl | |

| Non-ionic surfactants | mg/L | 32 | 0.4 | 1.4 | bdl | |

| Hydrocarbons, oil and fats | mg/L | 6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | bdl | |

| E. coli | CFU/100 mL | 64 | 2382 | 59000 | 0 | |

| Legionella spp. | CFU/L | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nematode eggs | Eggs/10L | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Parameter (mg/L) |

IP | VFTW | HFTW | ||||||

| Average | Max | Min | Average | Max | Min | Average | Max | Min | |

| COD | 7.46 | 64 | bdl | 13.23 | 54 | bdl | 19.37 | 58 | bdl |

| dCOD | 5.72 | 26 | bdl | 8.26 | 32 | bdl | 10.00 | 40 | bdl |

| pCOD | 1.71 | 59 | 0 | 3.58 | 16 | 0 | 9.37 | 34 | 0 |

| BOD5 | bdl | 5 | bdl | bdl | 6 | bdl | 5.12 | 8 | bdl |

| SS | bdl | 24 | bdl | 3.42 | 17 | bdl | 3.08 | 22 | bdl |

| Turbidity (FNU) | 1.31 | 2.43 | 0 | 5.58 | 30.77 | 0 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| N-NO3- | 3.38 | 13.6 | bdl | 6.36 | 31.2 | bdl | 1.58 | 7.7 | bdl |

| N-NH4+ | 0.25 | 32.7 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 1.55 | 0.05 | bdl | 0.7 | 0.05 |

| S-SO42- | 96.14 | 423.7 | 32.7 | 45.96 | 56.3 | 27 | 43.02 | 73.8 | 31.2 |

| Ca2+ | 59.57 | 69.3 | 46.5 | 71.04 | 72.3 | 44.8 | 64.85 | 71 | 56.3 |

| Mg2+ | 9.19 | 10.8 | 6.8 | 11.24 | 12.1 | 7.7 | 10.42 | 11.2 | 9.1 |

| Cl- | 46.81 | 137 | 25.5 | 56.67 | 97.4 | 28.4 | 59.53 | 82.3 | 22.2 |

| Anionic surfactants | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | Bdl | bdl |

| Cationic surfactants | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | Bdl | bdl |

| Non-ionic surfactants | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | Bdl | bdl |

| Hydrocarbons, oil and fats | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | Bdl | bdl |

| Parameter | IP | VFTW | HFTW | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Max | Min | Average | Max | Min | Average | Max | Min | |

|

E. coli (CFU/100 mL) |

<10 | 20 | bdl | <10 | 15 | Bdl | 100 | 300 | bdl |

|

Legionella spp. (CFU/L) |

Absent | 0 | 0 | Absent | 0 | 0 | Absent | 0 | 0 |

| Nematode eggs (Eggs/10L) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parameter | RD 1620/2007 (Urban Uses) | RD 1085/2024 (Urban Uses) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal nematodes | 1 egg/10L | Not specified | Likely removed due to advancements in treatment technology |

| E. coli | 200 CFU/100 mL | 100 CFU/100 mL | Stricter limit in 2024 (100 CFU/100 mL) for enhanced health protection |

| Suspended solids (SS) | 20 mg/L | 35 mg/L | Increased limit in 2024, providing more operational flexibility while maintaining quality. |

| Turbidity | 10 NTU | Not specified | Specified in 2007 to ensure water clarity; not defined in 2024. |

| Legionella spp. | 100 CFU/L (if aerosolization risk) | Monitoring required by RD 487/2022 | Mandatory monitoring remains, with compliance under RD 487/2022 |

| NbS | Recycling efficiency | Max daily capacity (m3/day) |

|---|---|---|

| HFTW | 57.8 | 9 |

| VFTW | 60 | 9 |

| IP | 60 | 9 |

| NbS | Max hydraulic load (cm/day) | Area per general vehicle (m2) | Area per car (m2) |

Area per industrial vehicle (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFTW | 10 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 3.2 |

| VFTW | 36 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| IP | 36 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).