Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

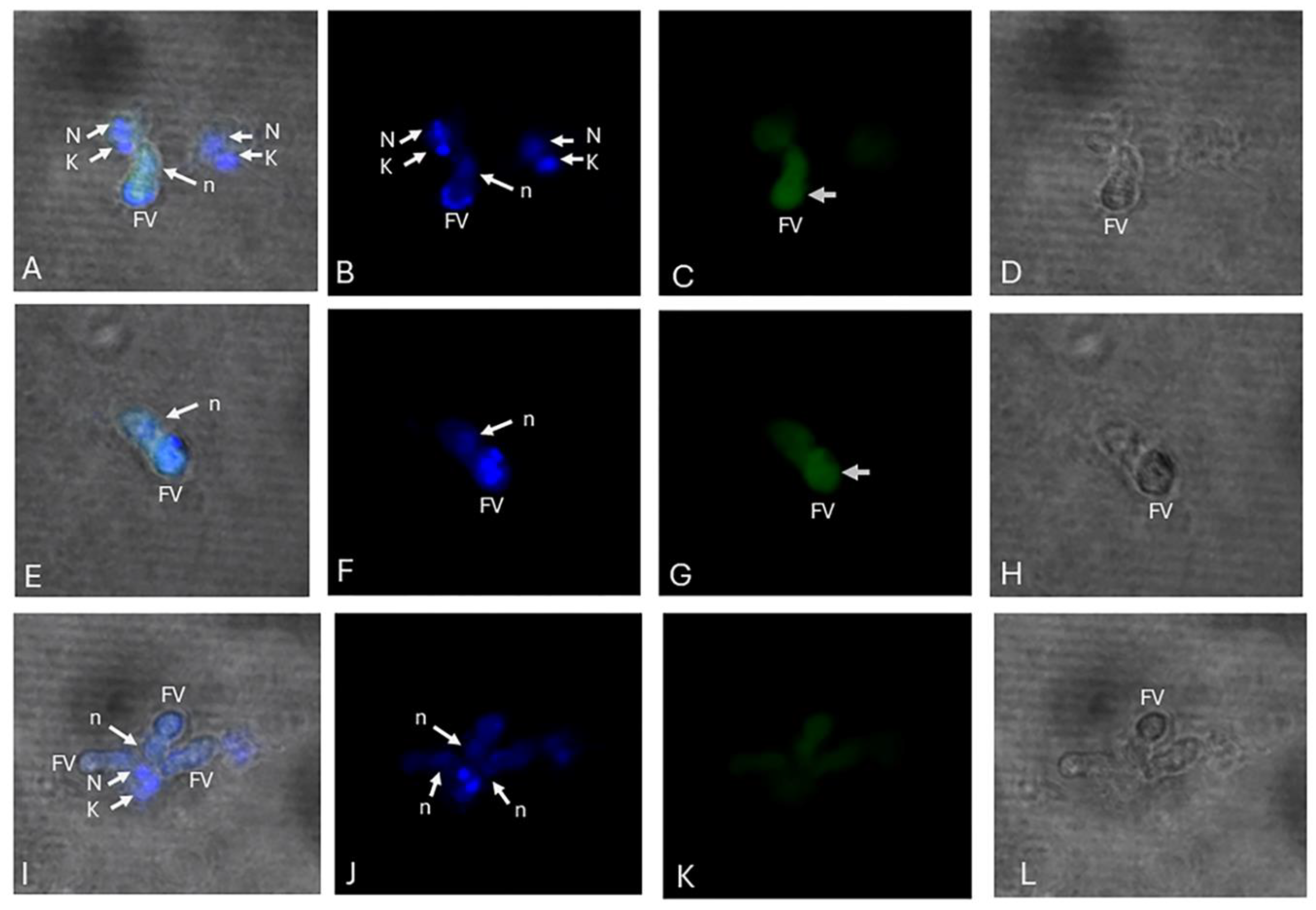

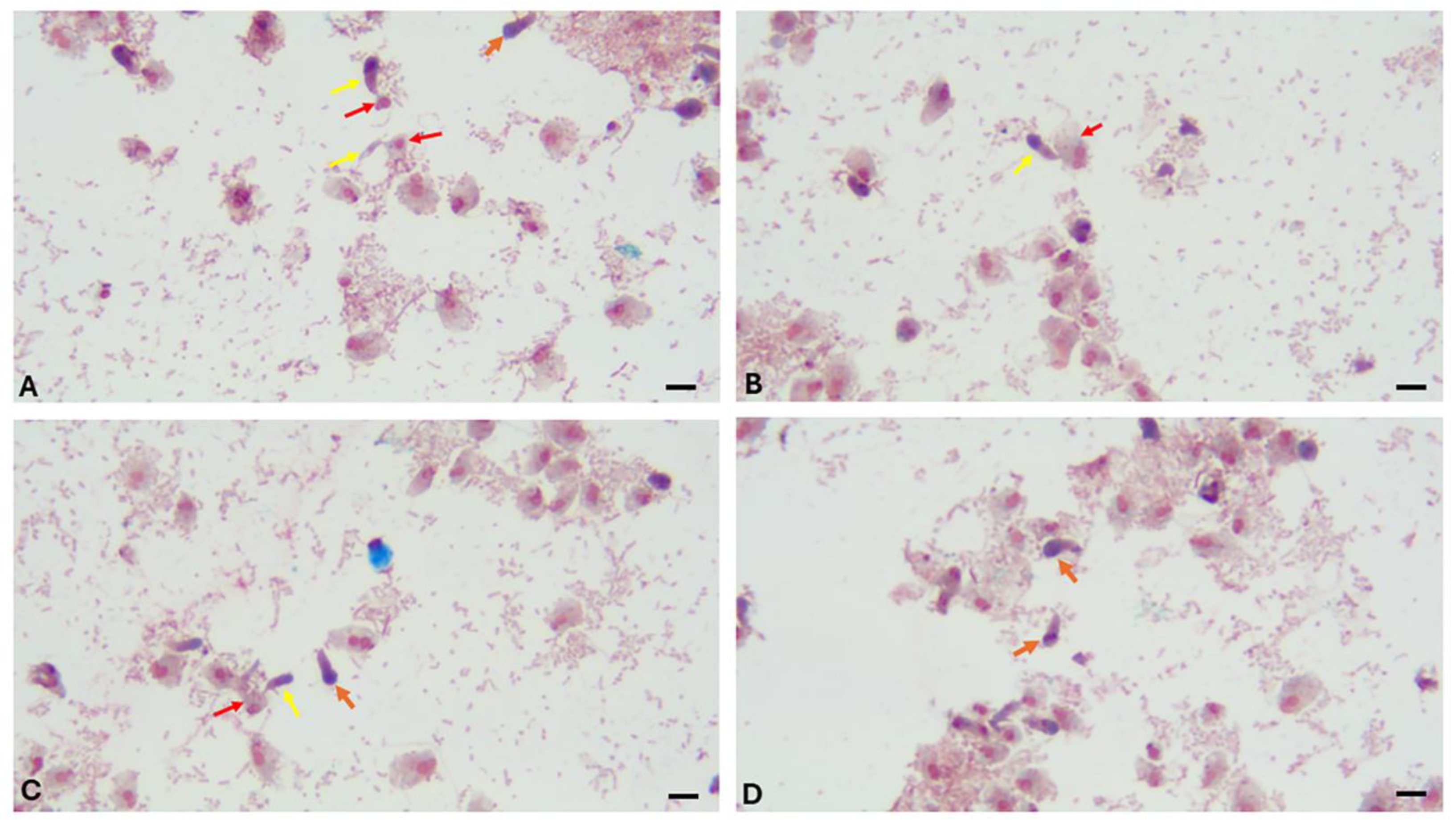

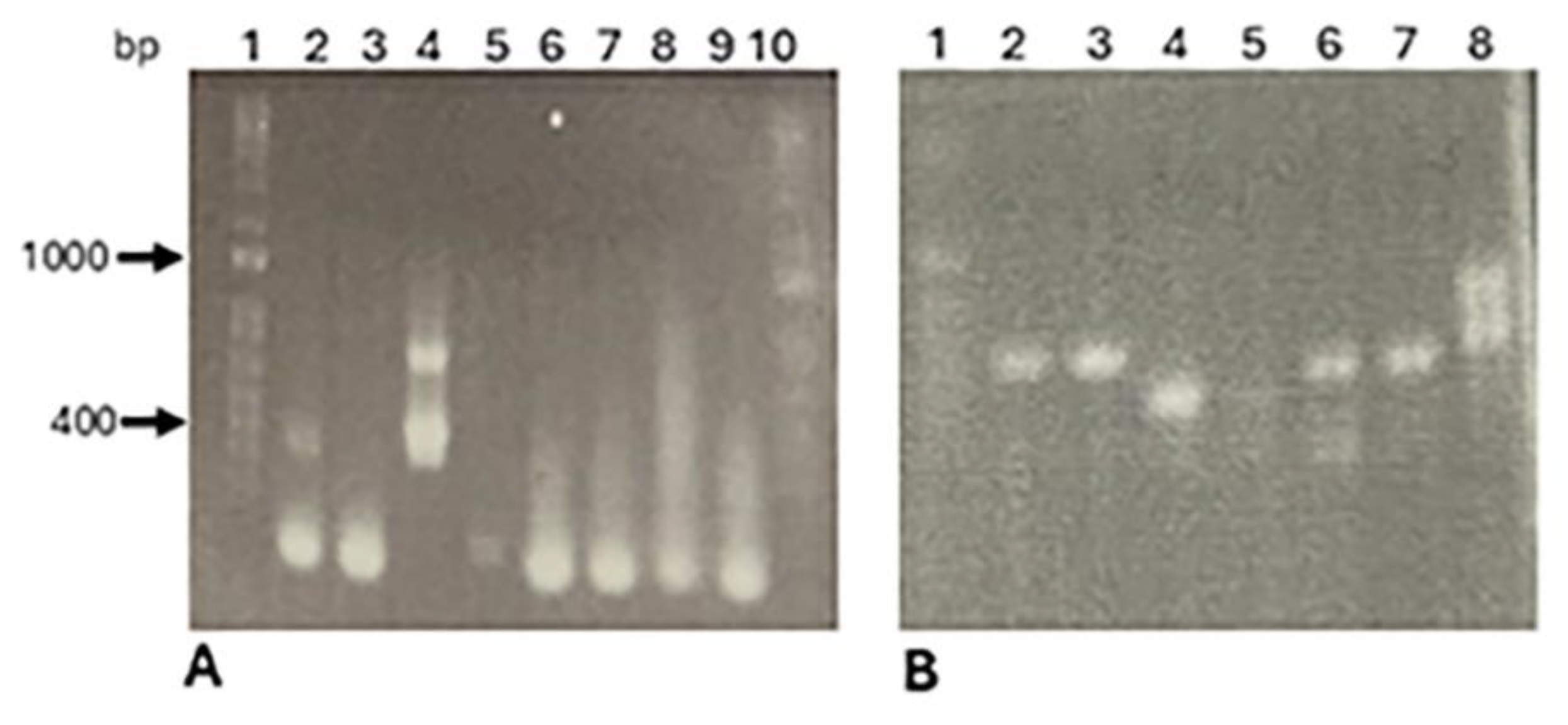

Colpodella species are predatory biflagellates phylogenetically related to pathogenic Apicomplexans like Plasmodium spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Babesia spp. and Theilaria spp. Colpodella species have been reported in human and animal infections. Trophozoites of Colpodella sp. ATCC 50594 obtain nutrients through myzocytosis and endocytosis. Following attachment of Colpodella sp. to its prey Parabodo caudatus, cytoplasmic contents of the prey are aspirated into a posterior food vacuole that initiates encystation. Unattached trophozoites also endocytose nutrients as demonstrated by the uptake of 40 and 100 nm nanoparticles. Cytochalasin D treatment was shown to distort the tubular tether formed during myzocytosis showing that actin plays a role in myzocytosis. Markers associated with myzocytosis, endocytosis and food vacuole formation are unknown. Furthermore, the relationship between the model Colpodella sp. ATCC 50594 and Colpodella sp. identified in arthropods, human and animal hosts are unknown. In this study we investigated the conservation of the coronin and Kelch 13 genes in Colpodella sp. ATCC 50594 using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Kelch 13 distribution in Colpodella sp. ATCC 50594 life cycle stages was investigated using anti-Kelch 13 antibodies by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Both genes were amplified from genomic DNA extracted from diprotist culture containing Colpodella sp. and P. caudatus but not from monoprotist culture containing P. caudatus alone. We amplified DNA encoding 18s rRNA with similarity to 18s rRNA amplified using piroplasm primers from the Italian Colpodella sp. identified in cattle and ticks. Detection of the coronin and Kelch genes in Colpodella sp. provides for the first time markers for actin binding and endocytosis in Colpodella species that can be investigated further to gain important insights into the mechanisms of myzocytosis, endocytosis and food vacuole formation in Colpodella sp.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Valigurová, A.; Florent, I. Nutrient Acquisition and Attachment Strategies in Basal Lineages: A Tough Nut to Crack in the Evolutionary Puzzle of Apicomplexa. Microorganisms. 2021, 9: 1430. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Long S, Hide G, Lun ZR, Lai DH. Apicomplexa micropore: history, function, and formation. Trends Parasitol. 2024 May;40(5):416-426. Epub 2024 Apr 17. PMID: 38637184. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.; Patterson, D. Ultrastructure and the identification of the predatory flagellate Colpodella pugnax Cienkowski (Apicomplexa) with a description of Colpodella turpis n. sp. and a review of the genus. Syst, Parasitol., 1996, 33, 187-198. [CrossRef]

- Brugerolle, G. Colpodella vorax: Ultrastructure, predation, life-cycle, mitosis, and phylogenetic relationships. Europ. J. Protistol., 2002, 38:113-125. [CrossRef]

- Cavalier-Smith T; Chao, E.E. Protalveolate phylogeny and systematics and the origins of Sporozoa and dinoflagellates (phylum Myzozoa nom. Nov.). Eur. J. Protistol. 2004, 40: 185-212. [CrossRef]

- Salti MI, Sam-Yellowe TY. Are Colpodella Species Pathogenic? Nutrient Uptake and Approaches to Diagnose Infections. Pathogens. 2024 Jul 21;13(7):600. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.L.; Keeling, P.J.; Krause, P.J. et al. Colpodella spp.–like Parasite Infection in Woman, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012, 18:125-127.

- Chiu, H.C.; Sun, X.; Bao, Y.; Fu, W.; Lin, K.; Chen, T.; Zheng, C.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Huang, C. Molecular identification of Colpodella sp. of South China tiger Panthera tigris amoyensis (Hilzheimer) in the Meihua Mountains, Fujian, China. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2022, 69:2022.019. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Hu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Wang, J.; Jiang, J. Colpodella sp. (Phylum Apicomplexa) Identified in Horses Shed Light on Its Potential Transmission and Zoonotic Pathogenicity. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13:857752. [CrossRef]

- Elochukwu, C. V.; Nnabuife, H. E.; Nicodemus, M.; Ogo, N. I.;Sylvanus, O. S.; Cornelius, J. O.; Kamani, J.; Maxwell, O. N. Molecular detection of Colpodella sp. using Cryptosporidium primers in faecal samples of small ruminants in FCT and Plateau State , Nigeria. J. Vet. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 6, 112-122.

- Olmo, J.L.; Esteban, G.F.; Finlay, B.J. New records of the ectoparasitic flagellate Colpodella gonderi on non-Colpoda ciliates. J Int Microbiol, 2011, 14:207-211. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J-F.; Jiang, R-R.; Chang, Q-C.; Zheng, Y-C.; Jiang, B-G.; Sun, Y.; Jia, N.; Wei, R.; Bo, H-B.; Huo, Q-B.; Wang, H.; von Fricken, M. E.; Cao, W-C. Potential novel tick-borne Colpodella species parasite infection in patient with neurological symptoms. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis., 2018, 12(8):e0006546. [CrossRef]

- Sam-Yellowe, T.Y.; Fujioka, H.; Peterson, J.W. Ultrastructure of Myzocytosis and Cyst Formation, and the Role of Actin in Tubular Tether Formation in Colpodella sp. (ATCC 50594). Pathogens, 2022, 11:455.

- Getty, T.A.; Peterson, J.W.; Fujioka, H.; Walsh, A.M.; Sam-Yellowe, T.Y. Colpodella sp. (ATCC 50594) Life Cycle: Myzocytosis and Possible Links to the Origin of Intracellular Parasitism. Trop Med Infect Dis., 2021, 6:127. [CrossRef]

- Sam-Yellowe, T.Y.; Asraf, M.M.; Peterson, J.W.; Fujioka, H. Fluorescent Nanoparticle Uptake by Myzocytosis and Endocytosis in Colpodella sp. ATCC 50594. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1945.

- Sam-Yellowe TY, Getty TA, Addepalli K, Walsh AM, Williams-Medina AR, Fujioka H, Peterson JW. Novel life cycle stages of Colpodella sp. (Apicomplexa) identified using Sam-Yellowe's trichrome stains and confocal and electron microscopy. Int Microbiol. 2022 Nov;25(4):669-678.

- Piro, F.; Focaia, R.; Dou, Z.; Masci, S.; Smith, D.; Di Cristina, M. An Uninvited Seat at the Dinner Table: How Apicomplexan Parasites Scavenge Nutrients from the Host. Microorganisms. 2021 Dec 15;9(12):2592. [CrossRef]

- Koreny, L.; Mercado-Saavedra, B.N.; Klinger, C.M.; Barylyuk, K.; Butterworth, S.; Hirst, J.; Rivera-Cuevas, Y.; Zaccai, N.R.; Holzer, V.J.C.; Klingl, A.; Dacks, J.B.; Carruthers, V.B.; Robinson, M.S.; Gras, S.; Waller, R.F.. Stable endocytic structures navigate the complex pellicle of apicomplexan parasites. Nat Commun., 2023, 14:2167. [CrossRef]

- Matz, J.M. Plasmodium's bottomless pit: properties and functions of the malaria parasite's digestive vacuole. Trends Parasitol., 2022, 38:525-543. [CrossRef]

- Elsworth, B.; Keroack, C.D.; Duraisingh, M.T. Elucidating Host Cell Uptake by Malaria Parasites. Trends Parasitol., 2019, 35:333-335. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui FA, Boonhok R, Cabrera M, Mbenda HGN, Wang M, Min H, Liang X, Qin J, Zhu X, Miao J, Cao Y, Cui L. Role of Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13 Protein Mutations in P. falciparum Populations from Northeastern Myanmar in Mediating Artemisinin Resistance. mBio. 2020 Feb 25;11(1):e01134-19. [CrossRef]

- Spielmann T, Gras S, Sabitzki R, Meissner M. Endocytosis in Plasmodium and Toxoplasma Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2020 Jun;36(6):520-532. [CrossRef]

- Ajibaye O, Olukosi YA, Oriero EC, Oboh MA, Iwalokun B, Nwankwo IC, Nnam CF, Adaramoye OV, Chukwemeka S, Okanazu J, Gabriel E, Balogun EO, Amambua-Ngwa A. Detection of novel Plasmodium falciparum coronin gene mutations in a recrudescent ACT-treated patient in South-Western Nigeria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024 Apr 23;14:1366563. [CrossRef]

- Demas et al. Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum actin-binding coroninconfer reduced artemisinin susceptibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2018, 115, 12799-12804.

- Chan, K. T.; Creed, S. J.; Bear, J. E. Unraveling the enigma: progress towards understanding the coronin family of actin regulators. Trends Cell Biol., 2011, 21, 481-8. [CrossRef]

- Bane, K. S. et al. The Actin filament -binding protein coronin regulates motility in Plasmodium sporozoites. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005710. [CrossRef]

- Sam-Yellowe TY, Yadavalli R, Fujioka H, Peterson JW, Drazba JA. RhopH3, rhoptry gene conserved in the free-living alveolate flagellate Colpodella sp. (Apicomplexa). Eur J Protistol. 2019 Oct;71:125637. [CrossRef]

- Jimale, K. A.; Bezzera-Santos, M. A.; Mendoza-Roldan, J. A.; Latrofa, M. S.; Baneth, G.; Otrano, D. Molecular detection of Colpodella sp. and other tick-borne pathogens in ticks of ruminants, Italy. Acta Tropica, 2024, 257, 107306. [CrossRef]

- de Laurent ZR, Chebon LJ, Ingasia LA, Akala HM, Andagalu B, Ochola-Oyier LI, Kamau E. Polymorphisms in the K13 Gene in Plasmodium falciparum from Different Malaria Transmission Areas of Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018 May;98(5):1360-1366. [CrossRef]

- Tardieux I, Liu X, Poupel O, Parzy D, Dehoux P, Langsley G. A Plasmodium falciparum novel gene encoding a coronin-like protein which associates with actin filaments. FEBS Lett. 1998 Dec 18;441(2):251-6. [CrossRef]

- Mayengue PI, Niama RF, Kouhounina Batsimba D, Malonga-Massanga A, Louzolo I, Loukabou Bongolo NC, Macosso L, Ibara Ottia R, Kimbassa Ngoma G, Dossou-Yovo LR, Pembet Singana B, Ahombo G, Sekangue Obili G, Kobawila SC, Parra HJ. No polymorphisms in K13-propeller gene associated with artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolated from Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. BMC Infect Dis. 2018 Oct 29;18(1):538. [CrossRef]

- Jonscher, E.; Flemming, S.; Schmitt, M.; Sabitzki, R.; Reichard, N.; Birnbaum, J.; Bergmann, B.; Höhn, K.; Spielmann, T. PfVPS45 Is Required for Host Cell Cytosol Uptake by Malaria Blood Stage Parasites. Cell Host Microbe, 2019, 25:166-173. [CrossRef]

- Edgar RCS, Counihan NA, McGowan S, de Koning-Ward TF. Methods Used to Investigate the Plasmodium falciparum Digestive Vacuole. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Jan 13;11:829823. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Meng J, Yu F, Zhou C, Yang B, Chen X, Yang G, Sun Y, Cao W, Jiang J, Wu J, Zhan L. Molecular epidemiological investigation of piroplasms carried by pet cats and dogs in an animal hospital in Guiyang, China. Front Microbiol. 2023 Oct 12;14:1266583. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.; Li, X.; Bukharr, S. M.; Zhou, M.; Ahmad, S.; Amhad, S.; Javid, A.; Guan, C.; Hussain, A.; Ali, W.; Khalid, N,;Ahmad, U, Tian, L.; Hou, Z. Cross-genera amplification and identification of Colpodella sp. with Cryptosporidium primers in fecal samples of zoo felids from northeast China. Braz J Biol. 2021 Sep 6; 83:e247181. [CrossRef]

- Qi Y, Wang J, Lu N, Qi X, Yang C, Liu B, Lu Y, Gu Y, Tan W, Zhu C, Ai L, Rao J, Mao Y, Yi H, Li Y, Yue M. Potential novel Colpodella spp. (phylum Apicomplexa) and high prevalence of Colpodella spp. in goat-attached Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks in Shandong province, China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2024 May;15(3):102328. [CrossRef]

- Soliman AM, Mahmoud HYAH, Hifumi T, Tanaka T. Discovery of Colpodella spp. in ticks (Hyalomma dromedarii) infesting camels in southern Egypt. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2024 Sep;15(5):102352. [CrossRef]

- Gnädig NF, Stokes BH, Edwards RL, Kalantarov GF, Heimsch KC, Kuderjavy M, Crane A, Lee MCS, Straimer J, Becker K, Trakht IN, Odom John AR, Mok S, Fidock DA. Insights into the intracellular localization, protein associations and artemisinin resistance properties of Plasmodium falciparum K13. PLoS Pathog. 2020 Apr 20;16(4):e1008482. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).