Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This research explored the experiences of LGBTQIA+, black and ethnic minority (BME), and disabled victims of domestic abuse due to the frequency of abuse in these populations and bespoke needs they may have. Data was collected via an online survey (n=317), a focus group with professionals (n=2), and interviews with victim/survivors of domestic abuse (n=2). Many articulated difficulties in accessing support for many reasons, including individual and structural barriers - such as embarrassment, stigma, shame, fear and not being aware of what support is available. Whilst good practice was reported, examples of secondary victimization towards victim/survivors by individuals, professionals and organizations were recounted. Many barriers were identified, for example there was inappropriate provision in refuges or shelters for LGBTQIA+ groups or disabled people. Disabled victims experienced additional barriers if their abuser was also their carer. BME groups may have additional language difficulties as well as cultural stigma and pressure to stay with their abuser. Recommendations for practice include the need for enhanced multi-agency training and recognition of abuse; crime victim/survivors being supported by someone with the same cultural background; easier access to interpreters; and more appropriate refuge or alternative housing options.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Definitions and Prevalence

1.1.1. LGBTQIA+ Victim/Survivors

1.1.2. BME Victim/Survivors

1.1.3. Disabled Victim/Survivors

1.2. Accessing Support

1.2.1. Barriers for LGBTQIA+ Victim/Survivors

1.2.2. Barriers for BME Victim/Survivors

1.2.3. Barriers for Disabled Victim/Survivors

1.3. Purpose of the Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surveys – General Public

2.2. Focus Group - Practitioners

2.3. Interviews – Victim/Survivors

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative Analysis

2.5.2. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Information

3.1.1. Survey

3.1.2. Focus Group

3.1.3. Interviews

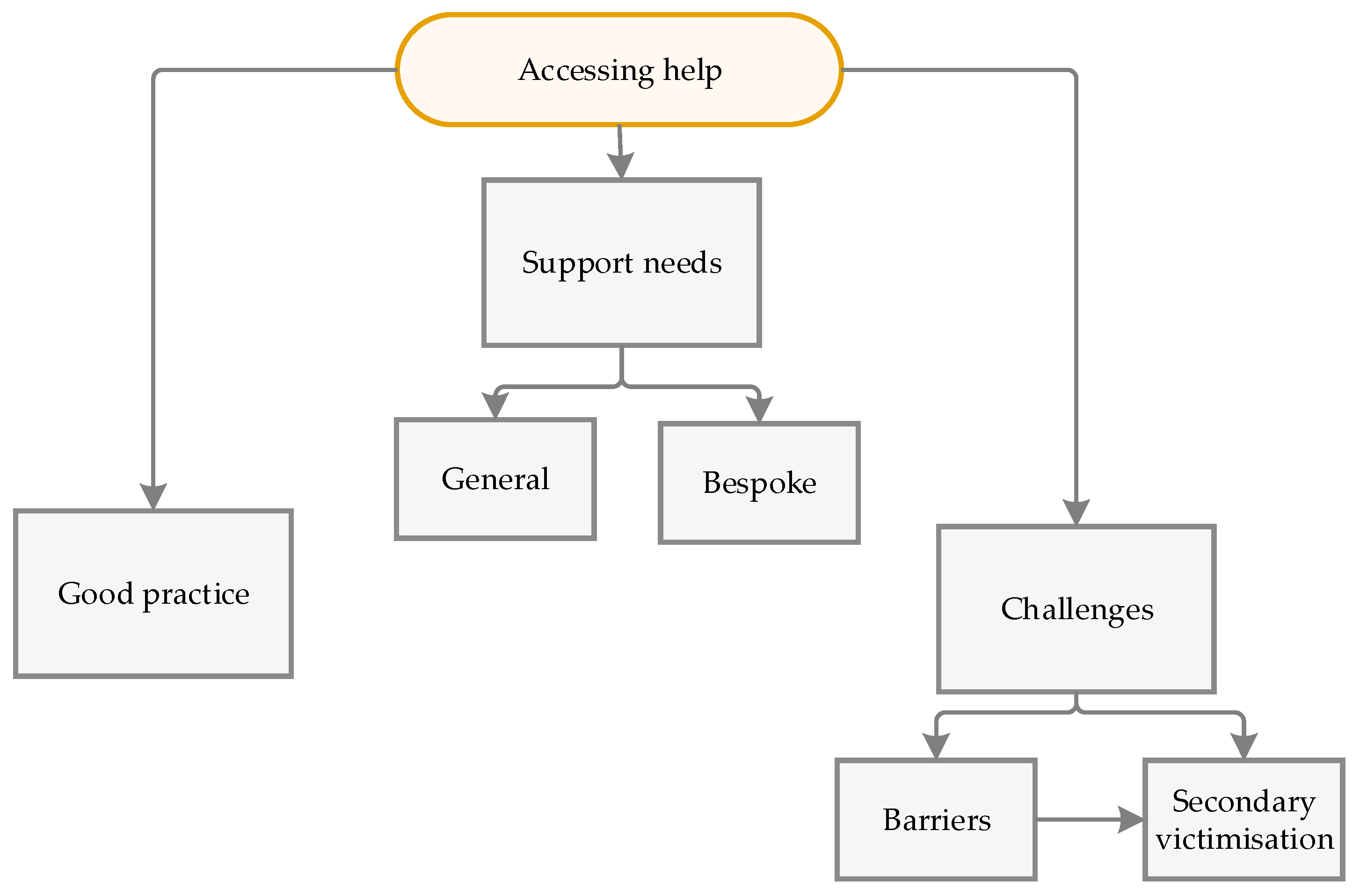

3.2. Identified Themes

3.2.1. Good Practice

3.2.2. Secondary Victimisation

3.2.3. Barriers to Obtaining Support

3.2.4. Support Needs – General

3.2.5. Support Needs – Bespoke

3.2.5.1. BME

3.2.5.2. Disabled People

3.2.5.3. LGBTQIA+

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ablaza, C., Kuskoff, E., Perales, F., & Parsell, C. (2022). Responding to Domestic and Family Violence: The Role of Non-Specialist Services and Implications for Social Work. The British Journal of Social Work, 81–99. [CrossRef]

- Afe, T. O., Emedoh, T. C., Ogunsemi, O. O., & Adegohun, A. A. (2017). Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Partner Characteristics, Socioeconomic Variables, and Intimate Partner Violence in Women with Schizophrenia in South-South Nigeria. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(2), 707– 720. [CrossRef]

- Afrouz, R., Crisp, B. R. &Taket, A. (2020). Seeking Help in Domestic Violence Among Muslim Women in Muslim-Majority and Non-Muslim-Majority Countries. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(3), 551-566.

- Ammar, N., Couture-Carron, A., Alvi, S. & San Antonio, J. (2014). Experiences of Muslim and Non-Muslim Battered Immigrant Women With the Police in the United States: A Closer Understanding of Commonalities and Differences. Violence Against Women, 19(12), 1449-1471.

- Andersson, N., Cockroft, A., Ansari, U., Omar, K., Ansari, N. M., Khan, A. & Chaudhry, U.U. (2009). Barriers to Disclosing and Reporting Violence Among Women in Pakistan: Findings From a National Household Survey and Focus Group Discussions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(11), 1965-1985.

- Anitha, S. (2008). Neither safety nor justice: The UK government response to domestic violence against immigrant women. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 30(3), 189–202, 2022. [CrossRef]

- AVA. (2022). Staying Mum A review of the literature on domestic abuse, mothering and child removal.

- Balderston, S. (2013) Victimized again? Intersectionality and injustice in disabled women’s lives after hate crime and rape. In Texler Segal, M. & Demos, V. eds. Gendered Perspectives on Conflict and Violence: Part A (Advances in Gender Research, Volume 18A) Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp.17 - 51.

- Bostock, J., Plumpton, M., & Pratt, Re. (2009). Domestic Violence Against Women: Understanding Social Processes and Women’s Experiences. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19, 95–110. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Sage: London CDC, 2013.

- Coles, N., Stokes, N., Retter, E., Manning, F., Curno, O., & Awoonor-Gordon, G. (n.d.). Blind and partially sighted people’s experiences of domestic abuse.

- Couto, L, O’Leary, N & Brennan< I (2023) Police victims of domestic abuse: barriers to reporting victimisation, Policing and Society, DOI: 10.1080/10439463.2023.2250523 48.

- Domestic Abuse Act (2021) Domestic Abuse Act 2021.

- Ellsberg M, Jansen HAFM, Heise L, et al. (2008) Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 371(9619):1165–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X.

- Emerson, E., & Llewellyn, G. (2023). Exposure of women with and without disabilities to violence and discrimination: evidence from cross-sectional national surveys in 29 middle-and low-income countries. Journal of interpersonal violence, 38(11-12), 7215-7241.

- Equality Act (2010) Equality Act 2010.

- Fanslow, J. L., Malihi, Z. A., Hashemi, L., Gulliver, P. J., & McIntosh, T. K. D. (2021). Lifetime Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence and Disability: Results From a Population-Based Study in New Zealand. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 61(3), 320–328. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G., Agnew-Davies, R., Bailey, J., Howard, L., Howarth, E., Peters, T. J., Sardinha, L., & Feder, G. S. (2016). Domestic violence and mental health: A cross-sectional survey of women seeking help from domestic violence support services. Global Health Action, 9(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M., Landis, L., Riordan, K., Naureckas, S., & Engel, B. (2005). Barriers to domestic violence help seeking: Implications for intervention. Violence Against Women, 11(3), 290–310. [CrossRef]

- Graca, S. (2017) Domestic violence policy and legislation in the UK: A discussion of immigrant women’s vulnerabilities. Eur. J. Curr. Leg. Issues, 22, 1–34.

- Griffiths, S., Allison, C., Kenny, R., Holt, R., Smith, P., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2019). The Vulnerability Experiences Quotient (VEQ): A Study of Vulnerability, Mental Health and Life Satisfaction in Autistic Adults. Autism Research, 12(10), 1516–1528. [CrossRef]

- Guasp, A. (2011). Lesbian, gay & bisexual people in later life. London: Stonewall.

- Hassouneh, D., & Glass, N. (2008). The Influence of Gender Role Stereotyping on Women’s Experiences of Female Same-Sex Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Against Women, 14(3), 310–325. [CrossRef]

- Healy, J.C. (2021) ‘An exposition of sexual violence as a method of disablist hate crime’, in I. Zempi and J. Smith (eds.) Misogyny as Hate Crime. London: Routledge, pp. 178-194.

- Heron, R. L., Eisma, M. C., & Browne, K. (2022). Barriers and Facilitators of Disclosing Domestic Violence to the UK Health Service. Journal of Family Violence, 37(3), 533–543. [CrossRef]

- Home Office (2024) New measures set out to combat violence against women and girls. 19 September 2024, from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-measures-set-out-to-combat-violence-against-women-and-girls.

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Jones, L., Wood, S., Bates, G., Eckley, L. McCoy, E., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T. & Officer, A. (2012) Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 379(9826), pp.1621-16.

- Hulley, J., Bailey, L., Kirkman, G., Gibbs, G. R., Gomersall, T., Latif, A., & Jones, A. (2023). Intimate Partner Violence and Barriers to Help-Seeking Among Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic and Immigrant Women: A Qualitative Metasynthesis of Global Research. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 24(2), 1001–1015. [CrossRef]

- Interventions Alliance. (n.d.). Domestic Abuse in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Groups | Interventions Alliance. Retrieved December 20, 2023, from https://interventionsalliance.com/domestic-abuse-in-black-asianand-minority-ethnic-groups/.

- Iob, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID19 pandemic. British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(4), 543–546. [CrossRef]

- Johnston-McCabe, P., Levi-Minzi, M., Van Hasselt, V. B., & Vanderbeek, A. (2011). Domestic Violence and Social Support in a Clinical Sample of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Women. Journal of Family Violence, 26(1), 63– 69. [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, K., McNeeley, M., & Collins, S. (2016). Young Men Who Have Sex With Men’s Experiences With Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(2), 143–175. [CrossRef]

- McDowell, M. J., Hughto, J. M., & Reisner, S. L. (2019). Risk and protective factors for mental health morbidity in a community sample of female-to-male trans-masculine adults. BMC psychiatry, 19, 1-12.

- Magowan, P. (2003) Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide: domestic violence and disabled women. Safe: Domestic Abuse Quarterly 5, pp.15-18.

- Maxwell, S. O’Brien, R. & Stenhouse, R. (2022). Experiences of Scottish Men who have been subject to Intimate Partner Violence in Same Sex Relationships Research Report *GBM_RR_summary.pdf (waverleycare.org) New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2022.

- Olabanji, O. A. (2022). Collaborative Approaches to Addressing Domestic and Sexual Violence among Black and Minority Ethnic Communities in Southampton: A Case Study of Yellow Door. Societies, 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Office of National Statistics. (2022). Characteristics of victims of domestic abuse based on findings from the Crime Survey for England and Wales and police recorded crime.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS), (2023) Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: year ending March 2023.

- Peitzmeier, S. M., Malik, M., Kattari, S. K., Marrow, E., Stephenson, R., Agénor, M., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. In American Journal of Public Health (Vol. 110, Issue 9, pp. E1–E14). American Public Health Association Inc. [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, B., Greenhead, S., Khalifeh, H., Drennan, V., Hart, T., Hogg, J., Borschmann, R., Mamo, E. & Moran, P. (2013) At risk, yet dismissed: The criminal victimisation of people with mental health problems. London: Victim Support & Mind.

- Romero-Sánchez, M., Skowronski, M., Bohner, G., & Megías, J. L. (2021). Talking about ‘victims’, ‘survivors’ and ‘battered women’: how labels affect the perception of women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Revista de Psicologia Social, 36(1), 30–60. [CrossRef]

- SafeLives (2015) Getting it right the first time - SafeLives.

- SafeLives. (2017b). Your Choice: ‘honour’-based violence, forced marriage and domestic abuse.

- Scheer, J. R., Lawlace, M., Cascalheira, C. J., Newcomb, M. E., & Whitton, S. W. (2023). Help-Seeking for Severe Intimate Partner Violence Among Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents and Young Adults Assigned Female at birth: A Latent Class Analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(9–10), 6723–6750. [CrossRef]

- Sin, C. H. (2015) Hate crime against people with disabilities. In Hall, N., Corb, A., Giannasi, P. & Grieve, J.G.D. ed(s) The Routledge International Handbook on Hate Crime. Oxon: Routledge, pp.193-206.

- Stephenson, R., Darbes, L. A., Rosso, M. T., Washington, C., Hightow-Weidman, L., Sullivan, P., & Gamarel, K. E. (2022). Perceptions of Contexts of Intimate Partner Violence Among Young, Partnered Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(15– 16), NP12881–NP12900. [CrossRef]

- Thiara, R. K. & Hague, G. (2013) Disabled women and domestic violence: Increased risk but fewer services. In Roulstone, A. & Mason-Bish, H. ed(s). Disability, Hate Crime and Violence. London: Routledge, pp106- 117.

- WHO (2018) Violence against women Prevalence Estimates, 2018. Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. WHO: Geneva, 2021.

- Wilson, J. M., Fauci, J. E., & Goodman, L. A. (2015). Bringing trauma-informed practice to domestic violence programs: A qualitative analysis of current approaches. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(6), 586–599. [CrossRef]

| Barriers to accessing support | No. of Yes Responses (n=160) |

Percentage (%) (Rounded) |

|---|---|---|

| Embarrassment or shame | 109 | 68 |

| Not recognising abuse | 107 | 67 |

| Fear of what might happen | 105 | 66 |

| Fear of not being believed | 101 | 63 |

| Denial | 90 | 56 |

| Not a big deal | 70 | 44 |

| Hope things will change | 64 | 40 |

| Worry about information sharing | 63 | 39 |

| Love for abuser | 52 | 33 |

| Loyalty for abuser | 50 | 31 |

| Accessing support | 50 | 31 |

| Worry about losing access to children | 49 | 31 |

| Worry about finances | 46 | 29 |

| Worry about losing friends and family | 46 | 29 |

| Worry about housing | 41 | 26 |

| Other | 16 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).