1. Introduction

The global health crisis caused by COVID-19 has had many consequences for the hospitality industry, particularly companies in the food and beverage sector (SIC 581 Eating and Drinking Places; NACE 56, Food and Beverage Service Activities). Infections and confinement orders threaten the economic viability of companies, as well as the social sustainability of employment, in a sector where people play such an essential role (Carvalho & Valdés, 2020; Verick, Schmidt-Klau, & Lee, 2022).

In this research project, we evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the restaurant industry and the availability and attractiveness of employment in bars, restaurants, and cafeterias. The objective is to identify the reasons why this sector is among the sectors most affected by the weakness of post pandemic economic recovery (Chatzinikolaou, Demertzis, & Vlados, 2021; Fang et al., 2021; Moulton et al., 2023). The pandemic has severely decreased revenues in the tourism and hospitality sectors in general (Crespí-Cladera, Martín-Oliver & Pascual-Fuster, 2021), which has resulted in dramatic decreases in both the frequency and number of transactions (Wang, 2021) in addition to a generalized decline in consumer sentiment (Moulton et al., 2023). The collapse of consumer demand or demand poses a grave risk to the survival of businesses in the sector (Kaufman, Goldberg, & Avery, 2020), further complicated by a phenomenon known as “the great resignation” (Tessema et al., 2022); that is, employee attrition or the reluctance of employees to return to their jobs after the pandemic (Liu-Lastres, Wen, & Huang, 2022), resulting in acute staff shortages and poor employee motivation (Chen, Zou, & Chen, 2022; Xia, Muskat, Vu, Law, & Li, 2023). This sector, in particular, has been singled out for generalized poor labor practices and working conditions, sometimes deemed akin to “modern slavery” (Vaughan, 2023), causing persistent and pervasive shortages of qualified staff in key kitchen and service positions (Amorim et al., 2022; Croes, Semrad, & Rivera, 2021). Work in the hospitality industry is recognized as being psychologically stressful, and fears of infection and uncertainties about the future exacerbate this tension only (Lai & Cai, 2022); this may explain the high rates of employee attrition in the sector, with staff quitting their jobs even when this involves renouncing unemployment benefits (Croes et al., 2021).

We believe it is important to explore the causes of these challenges given the importance of a healthy and profitable food and beverage industry to the economy as a whole and as a key element within the broader tourism ecosystem (de Albuquerque Meneguel, Mundet, & Aulet, 2019). Restaurants, bars, and taquerías are important to a community, providing spaces for social engagement and cohesion, and the activities of companies and employees have a significant effect on environmental sustainability (Batat, 2021). The sector is also economically and socially significant as an important source of employment and self-employment as well as an engine of inclusion, with high rates of migrant and female employees (International Labour Organisation -ILO; Cámara Nacional de la Industria de Restaurants y Alimentos Condimentados -CANIRAC-2020; Hostelería de España -HdeE, 2022 y 2023).

This study uses a multilevel analysis model (Dopfer, Foster, & Potts, 2004) to evaluate the duration and extent of institutional measures (macro level), the competitive structure of the sector (meso level) and business practices (micro level) during the pandemic and post pandemic periods (Chatzinikolaou, Demertzis, & Vlados, 2022). In view of the School of Industrial Organizations (Caves, 1992), identifying the structural characteristics of a sector (atomized and fragmented, poor hiring practices and working conditions; Costa et al., 2021; Ryder, 2020) can provide important insights, but given the demand shock, the precipitous collapse in demand, actions by governments and regulatory bodies are also an important part of recovery (Croes, Parsa, & Paraskevas, 2024). The effective management, preservation, and deployment of company resources involves careful decision-making about available assets (Liu et al., 2022), setting priorities for different elements of the sustainability balance sheet (economic, social, and environmental), stakeholders (consumers, shareholders, managers or workers; Li, Zhong, Zhang, & Hua, 2021) and the short- and medium-term outlook (Nguyen et al., 2022). These decisions can provide a competitive advantage when managing a crisis (Bamiatzi & Kirchmaier, 2014) and contribute to the industry's recovery (Tracey, 2020). Thus, a second objective of this research is to identify best practices in business management that lead to improved overall performance and sustainability, owing to positive outcomes in terms of revenues, value, and employment, making the pandemic an opportunity for positive changes in the sector.

The empirical research validates the proposed model, which is based on the grounded theory method (Strauss & Corbin, 2002), with an analysis of the sector in two countries (Mexico and Spain) in two regions of the world (Latin America and Europe), which applied different approaches, public policies, and economic measures in dealing with the pandemic (Soares & Berg, 2022). This study makes dynamic use of a diverse range of sources and research techniques to determine the broader and systemic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Hoehn-Velasco, Silverio-Murillo, & Balmori de la Miyar, 2021) and the dramatic collapse in demand (Maylín-Aguilar & Montoro-Sánchez, 2021). The results suggest, first, structural shortcomings, which are a determining factor in the pace and solidity of the recovery of business activity and employment, and, second, best practices applied by companies, researchers, and public authorities in boosting performance and enhancing the attractiveness of the industry while reducing employee attrition (Croes et al., 2021). The aim is to address the absence of in-depth analysis of the impact of the global pandemic, considering the relationship between the macro environment and companies within the restaurant sector; research into the effects of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry has largely focused on tourism and the accommodation sector (Okumus, Koseoglu, & Ma, 2018). By taking a multi-country approach, this study also aims to facilitate a valuable comparison between different cultural and social contexts, which are fundamental aspects of the industry (Gkoumas, 2022).

2. Materials and Methods

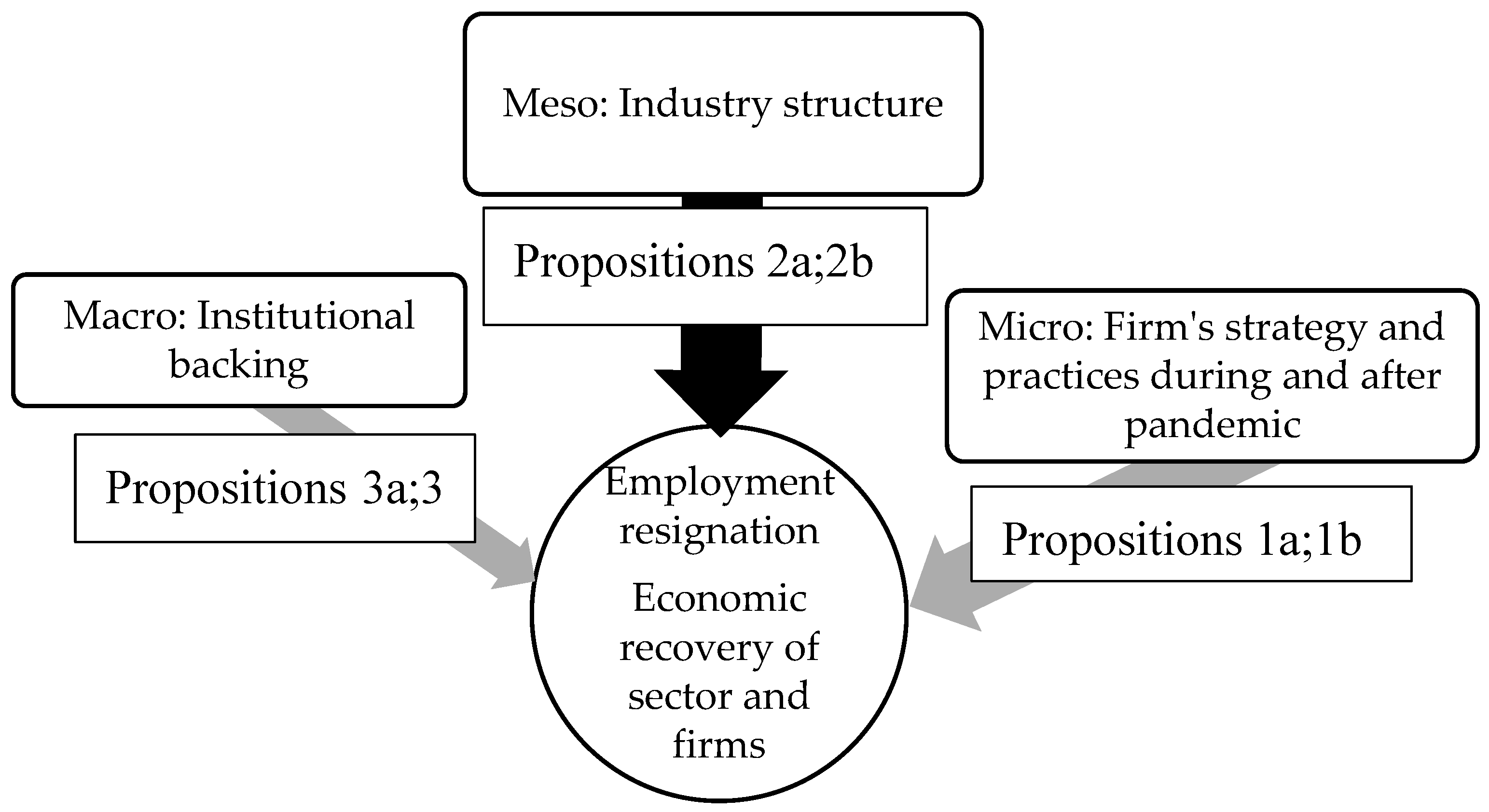

2.1. Multilevel Analysis of the Impact of the Demand Shock

Multilevel analysis of the behavior of the subjects and their reactions in the face of the pandemic takes into account the cultural and social context in which these actions take place (Presti & Mendes, 2023). In terms of the restaurant business (Dopfer, Foster, & Potts, 2004), the analysis approaches the economic realities by taking a macro view of the larger financial and social institutions as well as a meso view of the ecosystem of companies and their institutions within a specific territory (Chatzinikolaou, Demertzis, & Vlados, 2021). Inductively, the research model posits that the causes of the fragility and slow pace of post pandemic economic recovery and great resignation can be found in the actions taken at each level (macro, meso, and micro).

Figure 1.

Research model. Levels of analysis. Causes of the enduring effects (Employment, firms). Source: Authors’ elaboration. Arrows color and width signal the estimated importance of each of the causes in the effect.

Figure 1.

Research model. Levels of analysis. Causes of the enduring effects (Employment, firms). Source: Authors’ elaboration. Arrows color and width signal the estimated importance of each of the causes in the effect.

At the micro level, decisions are made by the business unit: owners and managers evaluate problems, set priorities to achieve economic sustainability and conserve the resources (financial, physical, relational, and locational, Li et al., 2020) of the business. A study by Amorim et al. (2022, p. 14) revealed that human resources managers generally make decisions in two directions: reactive, depending on circumstances or the environment, and proactive, seeking to meet the challenges presented by the pandemic at the micro level, that is, the business unit. Companies that skillfully deploy their resources and dynamic capabilities (flexibility, adaptation, innovation, talent management, and know-how, Teece, 2007) in the face of demand shock can gain a competitive advantage and recover more rapidly by spurring their teams to develop specific skills, such as assertiveness and decisiveness, in the face of a highly uncertain and changing business environment (Lai & Cai, 2023). This deployment of company resources may involve, among other things, certain human resource practices that are perceived as positive or negative by employees (Aloisi & De Stefano, 2022; Croes et al., 2021; Presti & Mendes, 2023; Tessema et al., 2022). Proposition Group 1 posits that decisions in one direction or another in the management of talent during confinement lead to different outcomes in terms of economic and social sustainability:

Proposition 1a: Companies with talent management practices deemed negative for employees have fewer dynamic capacities, delayed economic recovery, and greater employee attrition.

Proposition 1b: Companies with talent management practices deemed positive for employees have more dynamic capacities, accelerated economic recovery, and stable employment of personnel.

While the outcomes of business actions depend on the underlying strategy and decision-making, even under the most adverse circumstances (Bamiatzi & Kirchmaier, 2014), the model posits that all actions take place within a specific context; that is, at the meso level of the location, region or state, considering the structure of the industry, its characteristics in terms of dynamism, growth, barriers to entry or exit and the resources necessary to enter the sector (financial, physical or know-how). The demographics of sectors differ depending on the territory; some are highly concentrated, with large players with significant market power, or fragmented, characterized by numerous small companies, or asymmetrical, a combination of the two. According to the EOI and the Bain–Mason paradigm, the strategy of a company must fit the structure or character of the market: this may be hostile or unfavorable (uncertainty of demand, a fragmented or asymmetrical market, competitor or consumer power, etc.), or welcoming and favorable (absence of significant barriers to entry/exit, lack of supplier or consumer power, solid demand and growth, etc.) (Caves, 1992). These tensions may exacerbate inequality (Verick et al., 2022, pg. 14) between large corporations and small businesses with limited access to financing (Sharma, Lee & Lin, 2023). Thus, Proposition Group 2 posits the effect of industry structure on business recovery and employee attrition.

Proposition 2a: In an unfavorable industry structure, business recovery is slower, increasing asymmetries between companies and increasing employee attrition.

Proposition 2b: In a favorable structure, business recovery is faster, reducing asymmetries and maintaining stable employment.

At the macro level, the cycle of disruption caused by a pandemic generally involves restrictions on personal mobility, which are initially total and then limited or regional (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021; Wang, 2021). To mitigate the impact of confinement on businesses, governments deployed (or did not deploy, as in the case of Mexico) policies to stimulate the economy and protect companies (with direct payments to families in the case of the United States) and with subsidies and employment protections (as in the European Union) (Soares & Berg, 2022). The general stimulus to the economy has exacerbated inequalities because of the way public resources are dedicated to businesses and families (Chetty, Friedman, Hendren, Stepner, & Team, 2020), whereas employment protection policies mitigate the impact of job losses on the most vulnerable (Soares & Berg, 2022).

Proposition 3a: The longer the duration of restrictions is, the greater the impact on companies, with higher bankruptcy rates and slower recovery of business and employment.

Proposition 3b: The greater the investment in companies and employment is, the higher the rate of business survival and the lower the rate of employee attrition.

In the specific case of the pandemic, the existence and effectiveness of public health systems are considered important factors in the success of government initiatives in fostering a faster return to business growth and the recovery of employment: the precarity of these systems and differences in access (rural areas, elderly individuals, etc.) have resulted in wide disparities in mortality rates (JHU-CRC). The vaccination protocols that protected the majority of the population permitted earlier and safer economic reactivation and inter-territorial mobility, although they were hindered by successive waves of new variants of the virus (Lai & Cai, 2022) that prolonged uncertainty (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021) and fears of employees (Chen, Zhou & Chen, 2022).

2.2. Methodology of Empirical Research. Methods, Variables, and Indicators

The propositions and their interrelations were validated through qualitative analysis guided by the principles of veracity, confidence transferability, consistency, and neutrality (McGinley, Wei, Zhang, & Zheng, 2021), in which the researchers applied grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 2002), which was interpreted in light of their prior experience in the field and was subject to expert opinion (Thomas, 2006). This methodology was chosen given the opportunity for access to and understanding of the problem by researchers, educators and consultants active in the restaurant sector. Furthermore, the use of grounded theory as a methodology provides a structure for the use of different methods: deductive analysis of multiple sources of information in collecting data and the analysis of business behavior through case studies (Çakar & Aykol, 2021; de Albuquerque Meneguel et al., 2019).

2.2.1. Explanatory Variables and Control Variables

Previous studies analyzing the impact of the pandemic on businesses allowed us to refine our methods and calibrate conclusions through a comparison of methodologies and common variables and indicators (Aloisi & De Stefano, 2022; Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021; Sigala, 2020; Soares & Berg, 2022; Verick et al., 2022).

Variables and indicators at the micro level: Opportunity criteria were applied in the selection of cases, that is, access to information at the moment of the crisis and channels for oversight during the de-escalation period, thus ensuring that they represented the sector (Thomas, 2006). The dynamic analysis of business activities and practices was conducted in adherence with accepted practices in collecting evidence to extract case study lessons (Eisenhardt, 2021) through multiple primary and secondary sources.

Table 1 provides a summary of their activities.

Variables and indicators at the meso level: the variables and indicators identify and evaluate the characteristics that increase the hostility of the sector at times of crisis and uncertainty (Hao, Xiao, & Chon, 2020; Maylín-Aguilar & Montoro-Sánchez, 2021): 1. Dynamism of the sector: measured by the growth in the number of companies, employees and the value of the industry; 2. Competitiveness: size of companies (Juergensen, Guimón, & Narula, 2020), market fragmentation and asymmetry between micro, small and large companies (Verick et al., 2022); and 3. - competitive rivalry: concentration of market share in large companies (Caves, 1992). The characteristics of the labor market are evaluated in terms of salaries, absolute and compared to other sectors, informality and partial contracts, and inclusivity (women and young people) (Costa et al., 2021; Sánchez-Cubo, Mondéjar-Jiménez, & García-Pozo, 2023; Soares & Berg, 2022; Sull, Sull, & Zweig, 2022). A summary of the variables and indicators that measure the structure of the sector is provided in

Table 1.

Variables and indicators at the macro level: the actions of governments and institutions are classified according to 1. time, duration, and variability between territories as predictors of the decrease in consumer demand: lost visits and decreases in home delivery orders; 2. the measures and support provided to families and companies by governments and institutions, which are indicators of the percentage of gross domestic product (GDP); (Chetty et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021; Salem, Elbaz, Elkhwesky, & Ghazi, 2021; Soares & Berg, 2022; Yang et al., 2020); and 3. the existence and extension of public health services, which are based on two indicators (% of lethality of the virus and % of vaccinated population) extracted from the JHU-CRC. A summary of these variables is provided in

Table 3.

The control variables are as follows: 1. the relative importance of the sector in the economy and thus its total contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) and employment; and 2. the existence of employment alternatives, measured by the percentage of unemployment and the active population in employment. These variables and indicators are provided in

Table 4.

Table 1.

Indicators of business practices (ALSEA, CMR, Grupo José Mª) during the pandemic. Proposal for classification. Primary actions in the value chain.

Table 1.

Indicators of business practices (ALSEA, CMR, Grupo José Mª) during the pandemic. Proposal for classification. Primary actions in the value chain.

| Actions |

ALSEA |

Ev |

CMR |

Ev |

GRUPO JOSÉ Mª |

Ev |

| Logistics of inputs |

|

|

|

|

Flexible planning of needs in farms (suckling pigs) and gardens |

FL |

| Production operations |

|

|

Taking advantage of dormant resources of other companies (service in cinemas) |

IN |

|

|

| Change in service from outlets to home delivery and takeout |

FL |

Change in service from outlets to home delivery and takeout |

FL |

Home delivery service, attention to vulnerable groups |

AD |

| Logistics and product distribution |

Creation of an internal home delivery service |

IN |

Creation of an internal home delivery service |

IN |

Expanded menu of takeout (Gastro-Bar) and home delivery in all of Spain (‘Cochinillo Viajero’) |

AD |

| Sales and Marketing |

Closure of business units (estimated: 20%) |

FL |

Closure of business units (estimated: 10%) |

FL |

Closure of restaurant (complete service) |

AD |

| Activation of online offers |

AD |

Creation of products (‘It’s just Wings’) and expansion of offer (‘Sushi-Itto’) for home delivery |

IN |

Activation of Instagram as a communication channel with employees, giving voice to the community |

AD |

| Customer service |

|

|

Low-priced menu options aimed at young, urban clients |

AD |

Donation of redundant inputs to hospitals and clinics.

Maintain contact with clients (local community) |

AD |

Actions to support the value chain

| |

ALSEA |

|

CMR |

|

GRUPO JOSÉ Mª |

|

| Company structure. Management and decision-making |

Centralized management of dispersed locales (multinational)

|

FL |

|

|

Highlight the family-run nature of the company (José María & Rocío Ruiz) to staff and clients. |

AD |

| Talent management: cost-cutting. |

Employee layoffs (closed units, temporary closures

Reduction of schedules and salary |

AD |

Employee layoffs (units closed, fall in activity)

Retain employees |

AD |

Restaurant closed. Uncertainty about the future. Risk of demotivation and resignations |

AD |

| Layoffs are estimated at 20.4% (16,000 people), leaving without pay, and searching for alternative employment for new staff. |

FL |

Employees “lent” to other companies (e.g., Wal-Mart) with a shared salary scheme. |

IN |

Employees are retained with reduced salaries (measures by the Spanish government). |

AD |

| Reduction of incentives/bonuses for managers and directors |

AD |

Reduction of incentives/bonuses for managers and directors |

AD |

|

|

| Talent management: internal atmosphere |

|

|

|

|

Continuous communication, maintaining operational meetings (daily in restaurants, weekly for all staff). |

AD |

| Technology and development |

APP for home delivery service |

IN |

APP for home delivery service |

IN |

IT systems for remote meetings with all employees (120 homes) |

IN |

| Purchasing |

Preference for local products (closed borders) |

AD |

|

|

Maintenance of the value chain (vertical integration). Ceding of surpluses |

AD |

Source: the authors. Evaluation (Ev): indicator of dynamic capacities for adaptation (AD), flexibility (FL) and innovation (IN).

Table 2.

Variables and indicators of meso level – Structure of the industry.

Table 2.

Variables and indicators of meso level – Structure of the industry.

| |

Period |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2022/2018 |

Evaluation |

| |

|

Number of firms |

|

|

| Sector dynamism: Evolution of number of firms, employment, turnover |

Mexico |

584,023 |

637,124 |

517,124 |

641,279 |

674,826 |

15.55% |

Fav |

| Spain |

260,306 |

261,442 |

253,350 |

260,581 |

265,125 |

1.85% |

Unfav |

| |

Number of employees |

|

|

| Mexico |

2,260,000 |

2,510,000 |

1,790,000 |

2,310,000 |

2,520,000 |

11.50% |

Fav |

| Spain |

1,207,960 |

1,262,971 |

1,114,445 |

1,145,013 |

1,271,964 |

5.30% |

Neutral |

| |

Turnover in the local currency |

|

|

| Mexico Mill |

452,490 |

592,172 |

344,230 |

450,739 |

549,120 |

21.36% |

Fav |

| Spain ‘000 |

51,268,615 |

54,209,610 |

32,807,314 |

44,169,721 |

61,241,052 |

19.45% |

Fav |

Firm’s demography:

Size, concentration and fragmentation |

|

Average size in number of employees |

|

|

| Mexico |

4.00 |

3.94 |

3.46 |

3.60 |

3.73 |

-6.64% |

Unfav |

| Spain |

4.60 |

4.80 |

4.40 |

4.40 |

4.80 |

4.35% |

|

| |

% share micro firms (less than 10 employees) in the total n. of firms |

|

| Mexico |

96.10% |

|

|

|

95.60% |

-0.52% |

Unfav |

| Spain |

95.43% |

95.29% |

95.74% |

95.68% |

95.58% |

0.16% |

Unfav |

| |

% share of micro firms in the total employment |

|

|

| Mexico |

71.10% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Spain |

24.84% |

23.92% |

23.84% |

21.87% |

21.25% |

-14.45% |

Unfav |

| % share of medium and big firms (more than 50 employees) in the total n. of firms |

|

| Mexico |

0.35% |

|

|

|

0.53% |

50.52% |

Fav |

| Spain |

0.31% |

0.34% |

0.34% |

0.33% |

0.44% |

41.94% |

Fav |

Labor market indicators:

Wages, Type of contract, employment of women and youth |

|

Average wage of the sector (monthly basis PMX - €) |

|

|

| Mexico |

3,890,00 |

4,160,00 |

3,860,00 |

4,640,00 |

4,740,00 |

21.85% |

Fav |

| Spain |

1,195,44 |

1,213,48 |

1,178,08 |

1,219,40 |

1,389,90 |

16.27% |

Fav |

| |

Rate of sectoral wage on the average economy’s wage |

|

|

| Mexico |

0.97 |

0.97 |

0.86 |

0.94 |

0.92 |

-4.94% |

Unfav |

| Spain |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.56 |

0.56 |

0.58 |

-2.99% |

Unfav |

| |

Informal contracts (% occupied persons) |

|

|

| Mexico sector |

68.70% |

69.10% |

70.50% |

71.80% |

71.00% |

3.35% |

Unfav |

| Mexico economy |

56.70% |

56.50% |

54.20% |

56.30% |

55.60% |

-1.94% |

|

| |

% Employees with part-time contracts |

|

|

| Spain sector |

22.60% |

23.10% |

23.50% |

24.10% |

21.70% |

-3.98% |

Unfav |

| Spain economy |

13.90% |

14.00% |

13.80% |

13.40% |

12.80% |

-7.91% |

|

| |

% Women on total employees |

|

|

| Mexico |

58.87% |

55.20% |

|

|

32.91% |

|

Fav |

| Spain |

50.40% |

51.20% |

50.00% |

51.20% |

51.00% |

|

Fav |

| |

% salary gap between men and women |

|

|

| Mexico |

-22.14% |

-22.94% |

-16.92% |

-19.57% |

-20.53% |

|

Unfav |

| Spain |

-27.03% |

-20.31% |

-22.48% |

-21.22% |

-21.22% |

|

Unfav |

| |

% Women with part-time contracts |

|

|

| Spain sector |

28.20% |

29.60% |

29.10% |

29.50% |

30.70% |

8.87% |

Unfav |

| Spain economy |

22.70% |

22.80% |

22.30% |

21.70% |

20.60% |

-9,25% |

|

| % Youth on total employees (less than 25 Mexico, less than 30 y o Spain) |

|

| Mexico |

9.91% |

11.30% |

19.91% |

25.83% |

34.20% |

|

Fav |

| Spain |

24.80% |

26.00% |

23.00% |

25.00% |

27.70% |

11,69% |

Fav |

Table 3.

Variables and indicators of the macro level – Institutions and Government actions.

Table 3.

Variables and indicators of the macro level – Institutions and Government actions.

| |

Mexico |

Spain |

| Time of restrictions (confinements, temporary closures, partial openings) |

Total confinement from March to May, 2020

Partial openings from June, 2020 to May, 2021.

Freedom for movements inside Mexico, for residents and foreigners |

Total confinement from March to May, 2020

Partial openings and freedom movements partial restrictions from June, 2020 to November, 2021, depending on local authorities (Autonomous Community, Provinces, Neighborhoods) |

| Backing intensity to firms and employees |

% of GDP in backing measures, 0.6% in 2020

There were no specific supporting measures to firms, neither incentives to retain workers |

% of GDP in backing measures, 1.46% (2.43% EU average in 2020,

1.04% in 2021)

The national government paid 70% of the wage for non-essential workers from March 2020 to November 2021, depending of the sector and the location |

| National Health System |

Coverage of Active Workers. Emergency attention for the rest of the population.

Mortality rate of 4.5% of declared cases

Vaccination index, 77.53% population with at least one dose |

Universal

Mortality rate of 0.9% of declared cases

Vaccination index 88.43% population with at least one dose |

Table 4.

Control variables indicators and measures.

Table 4.

Control variables indicators and measures.

| |

%Number of firms |

Ratios |

| Importance of the sector for the national economy |

|

2015 |

2022 |

2022/2015 |

2022/2018 |

| Mexico |

10.98% |

12.22% |

11.29% |

-7.91% |

| Spain |

7.92% |

7.73% |

-2.40% |

-0.91% |

| |

% Number of employees |

|

|

| Mexico |

7.71% |

8.50% |

10.28% |

-3.45% |

| Spain |

5.60% |

6.19% |

10.45% |

-0.95% |

| |

% Turnover on GDP |

|

|

| Mexico |

2.40% |

2.22% |

-7.48% |

-9.11% |

| Spain |

3.90% |

4.19% |

7.48% |

-1.64% |

| Labor market, total economy |

|

% of Unemployment |

|

|

| Mexico |

4.35% |

3.27% |

-24.79% |

-6.60% |

| Spain |

22.06% |

13.04% |

-40.90% |

-14.55% |

| |

% of Workers on Active population |

| Mexico |

57.86% |

59.76% |

3.29% |

-0.59% |

| Spain |

59.50% |

58.40% |

-1.85% |

-0.43% |

2.2.2. Dependent Variables. Business Recovery and Employee Attrition

Speed and solidity of business recovery: evolution in the number of companies, turnover, and employment: indicators for the creation of new companies, closures, and self-employment (CANIRAC, 2020; Carvalho & Valdés, 2020; Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2023). The indicators for Mexico and Spain from 2015--2022 are provided in

Table 5.

Employment: An indicator of the magnitude of the demand shock caused by the pandemic is the loss of jobs (Presti & Mendes, 2023; Ryder, 2020; Sharma et al., 2023), as reflected in

Table 4. Given the absence of a common indicator for different geographical regions regarding pervasive resignations or reluctance to return to work, we have outlined the principal factors in this phenomenon identified in previous studies (Hao et al., 2020; Liu-Lastres et al., 2022; Sull et al., 2022; Tessema et al., 2022; Xia, Muskat, Vu, Law, & Li, 2023).

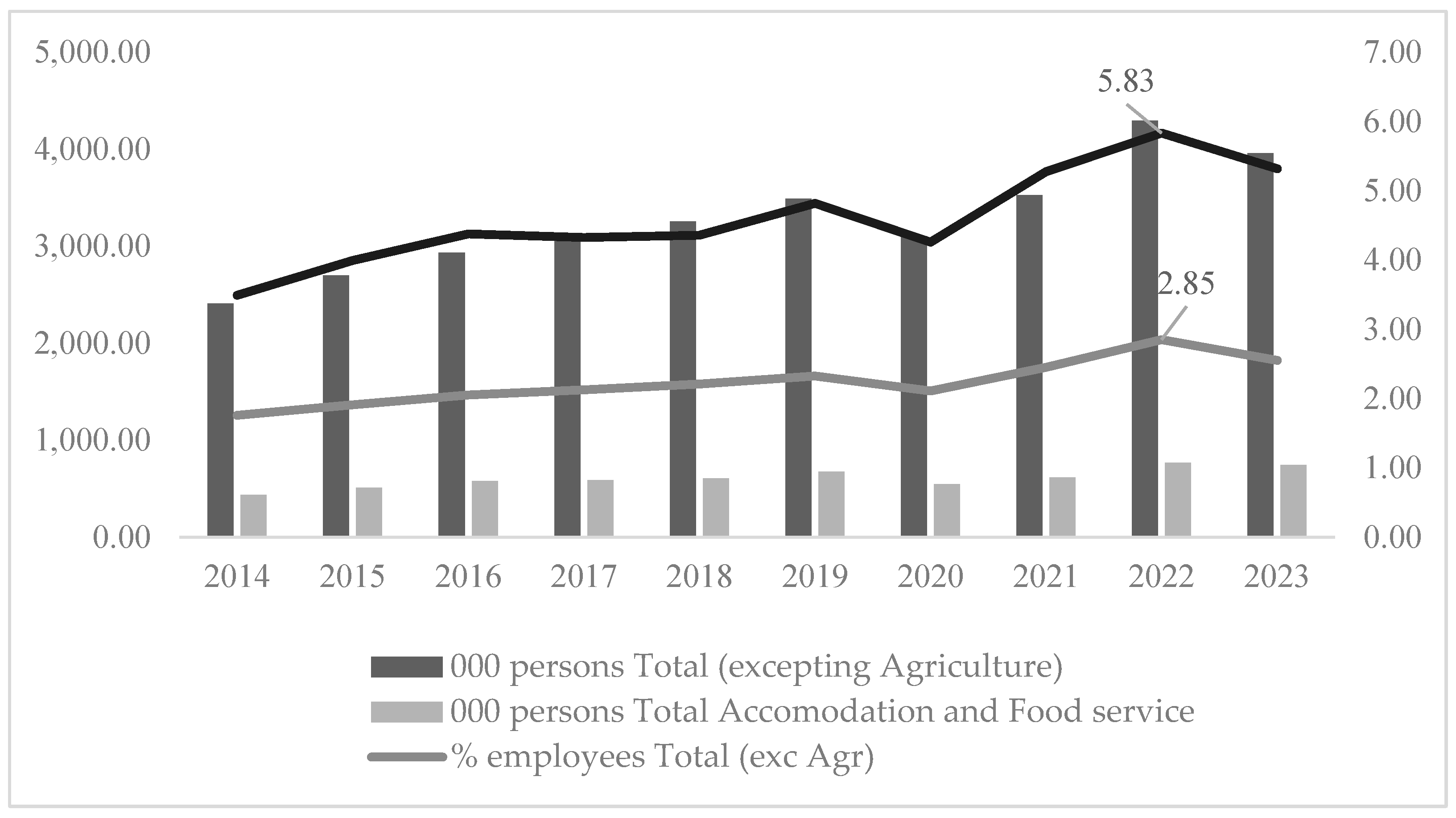

Statistics on the number of people (and percentage of total employees) leaving employment from the Department of Labor of the United States are displayed in Figure II. The bars represent the number of people (in thousands), and the lines represent the percentage of employed individuals who have given up employment in the economy as a whole (excluding agriculture) and in the hospitality and food and beverage industry (Acc + FS). The percentage of people leaving employment in the hospitality and food and beverage industry (Acc + FS) reached 5.83% of total employees in 2022, double the figures for the economy as a whole (excluding agriculture).

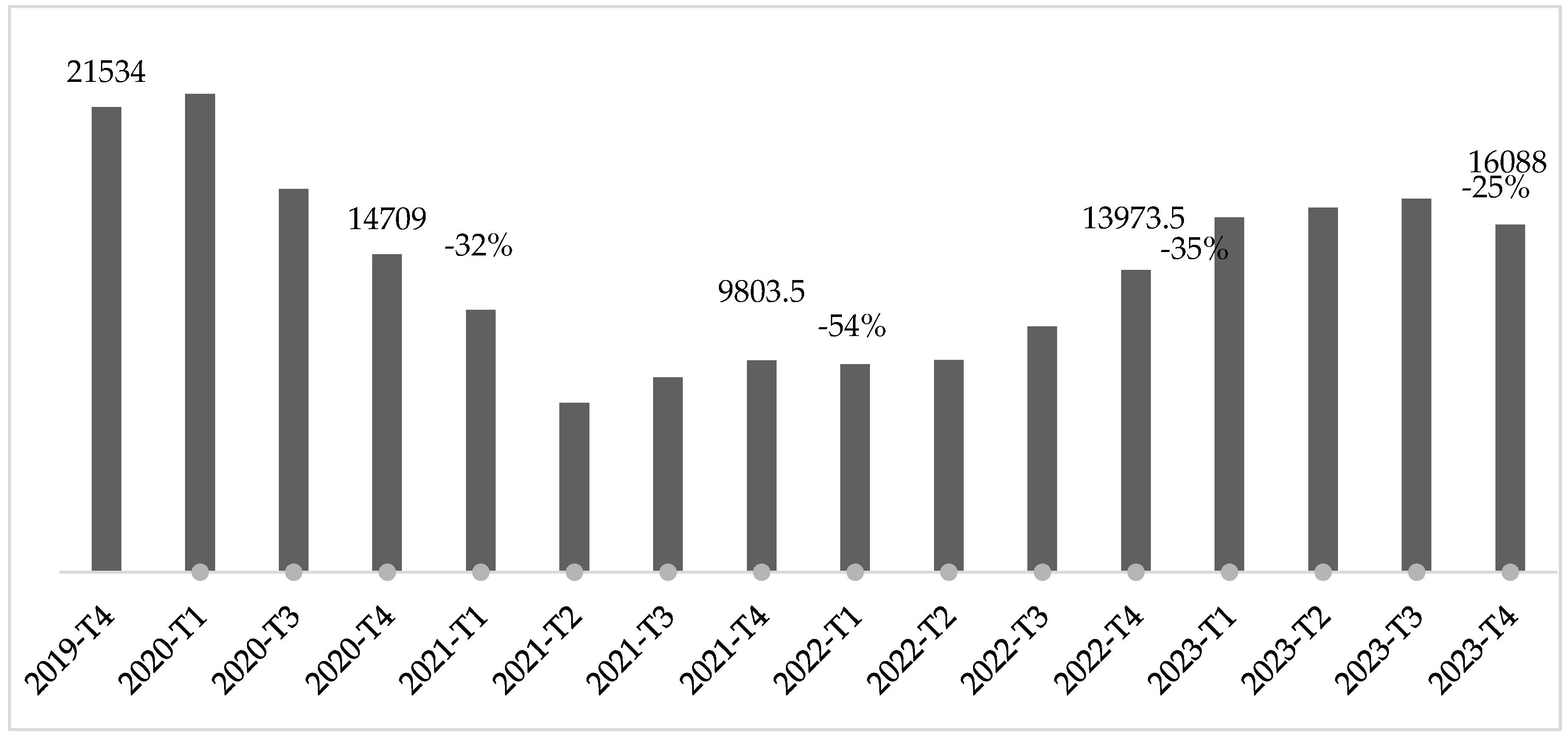

Total number (in persons) of job losses: In Mexico, job losses due to company closures (an estimated 120,000 companies according to Deloitte México) reached their peak one year after the onset of the pandemic, in 2021 (Data México). This time frame, presented in Figure III, indicates not only employee attrition, including those who voluntarily give up their jobs but also the absence of new revenues. In terms of the economy, according to data from the National Occupation and Employment Survey (ENOE), during the first quarter of 2021, there were 773,252 resignations whose motivations were analyzed in the report: “Post pandemic and labor adaptability in Mexico” (OCCMundial, 2022), indicating that 71% of those employed consider resigning, 59% seeking better salary and conditions, and 55% seeking professional advancement and development. The report also noted that 41% of the human resources managers in large companies noted an unusual spike in the number of resignations motivated by “physical and mental exhaustion”.

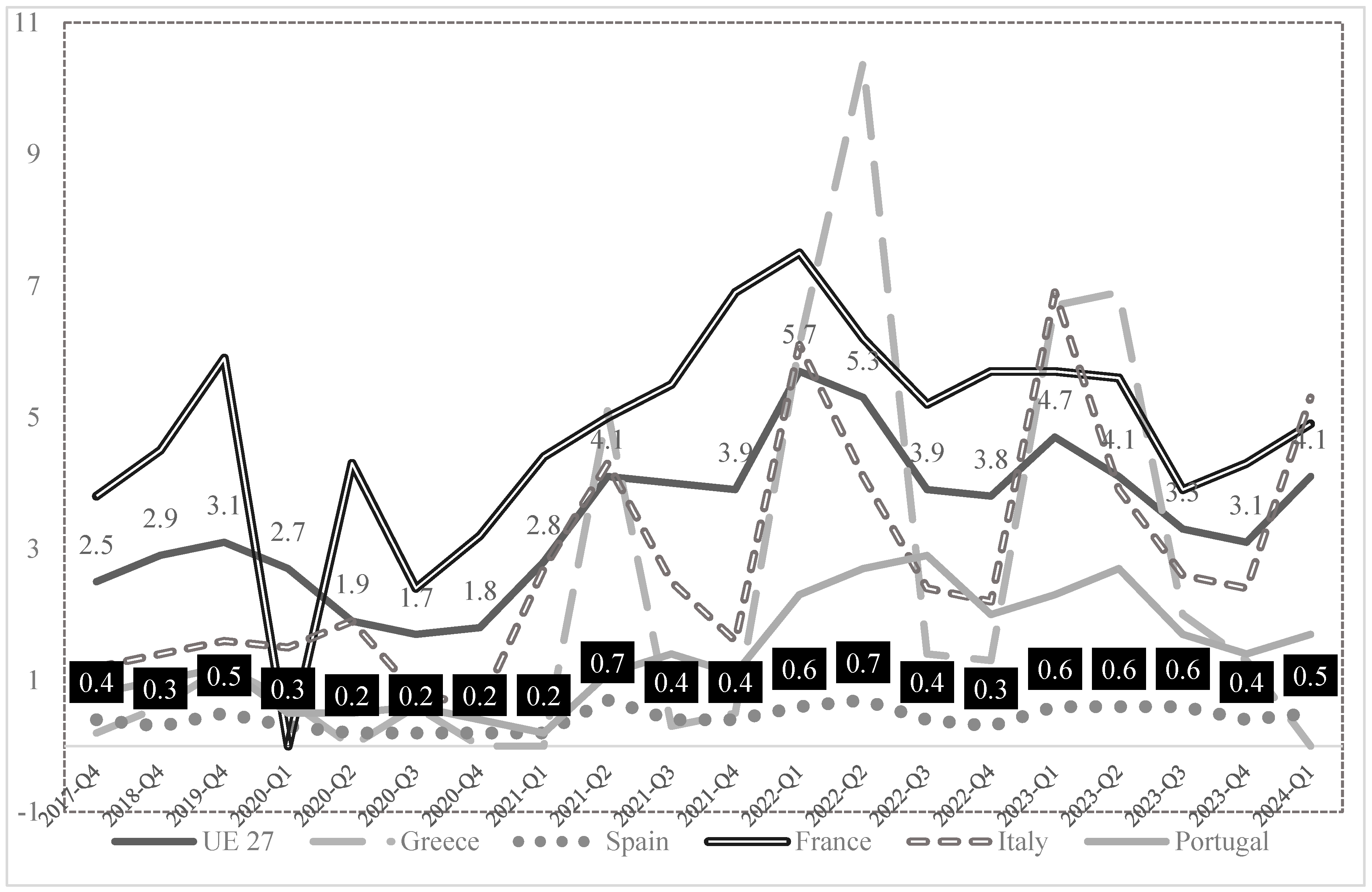

Job vacancy rate (JVR): the total proportion of vacant jobs expressed as the following percentage: JVR = number of vacant jobs/(number of occupied posts + number of job vacancies) × 100. Figure IV shows the evolution of the percentage of job vacancies from 2017--2024 as a percentage of the total number of available jobs in the EU27 (without the United Kingdom) and five countries of southern Europe (Spain, France, Greece, Italy, and Portugal) for the activity sector Accommodation and Food and Beverage Service. This indicator should be taken into account the negative relationship between job vacancies and unemployment, the Beveridge curve: in periods of recession, there are few job vacancies and high unemployment, whereas in periods of economic expansion, there are more job vacancies and the unemployment rate is low (Eurostat). In the case of Spain, just as in Greece, a high level of unemployment in the economy as a whole (averaging 12.2% in 2023--Q12024) is accompanied by a low job vacancy rate (0.9%), whereas in France and Italy, lower levels of unemployment suppose more job vacancies.

Figure 2.

Leave of Employment evolution (United States of America). Total (excepting Agriculture), Accommodation and Food Service. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor (reports JTS720000000000000QUL). Columns depict the number of persons that left their employs in each period, and lines the percentage on the total employment. The percentage for the Accommodation and Food Service sector increases since 2021 and in 2022 (5,83%) doubles the one of the total economy (2.85%), even though it was higher than in previous periods. The 2023 figure keeps the difference, signaling a higher rate of leaves in the Accommodation and Food Service sector.

Figure 2.

Leave of Employment evolution (United States of America). Total (excepting Agriculture), Accommodation and Food Service. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor (reports JTS720000000000000QUL). Columns depict the number of persons that left their employs in each period, and lines the percentage on the total employment. The percentage for the Accommodation and Food Service sector increases since 2021 and in 2022 (5,83%) doubles the one of the total economy (2.85%), even though it was higher than in previous periods. The 2023 figure keeps the difference, signaling a higher rate of leaves in the Accommodation and Food Service sector.

Figure 3.

Timely evolution of the average number of employees in the sector of food and drinks preparation and service (722) in México. Source: Data México.

https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/industry/accommodation-and-food-services. Columns depict the number of employees in each period. The percentages show the variance of the absolute figure in the last quarter (Q4) of each year, compared with the absolute figure in Q4 2019. In spite that the indicator does not capture the full number of workers (self-employed, families), reveals the great fall and the slow recovery in the sectoral employment.

Figure 3.

Timely evolution of the average number of employees in the sector of food and drinks preparation and service (722) in México. Source: Data México.

https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/industry/accommodation-and-food-services. Columns depict the number of employees in each period. The percentages show the variance of the absolute figure in the last quarter (Q4) of each year, compared with the absolute figure in Q4 2019. In spite that the indicator does not capture the full number of workers (self-employed, families), reveals the great fall and the slow recovery in the sectoral employment.

Figure 4.

Job vacancy rate, positions uncovered in the Accommodation and Food service sector. European Union (27 countries, post Brexit) and countries form South Europe (Greece, France, Italy, Spain and Portugal). Source: Eurostat, job vacancy statistics, jvs_q_nace2__custom_11992628 Statistics | Eurostat (europa.eu). Bold line shows the evolution of uncovered vacancies in the Union since 2019, when vacancies were around 3.0% of the total employment, but increased to 5.7-5.3 in 2021 and continued to be a little higher during 2023 and 2024. Country lines show seasonal variations (Q2-Q3) in France, Italy and Greece, while the pattern in Portugal is more stable. The figures for Spain, white numbers in black cases show the lower rate of uncovered vacancies.

Figure 4.

Job vacancy rate, positions uncovered in the Accommodation and Food service sector. European Union (27 countries, post Brexit) and countries form South Europe (Greece, France, Italy, Spain and Portugal). Source: Eurostat, job vacancy statistics, jvs_q_nace2__custom_11992628 Statistics | Eurostat (europa.eu). Bold line shows the evolution of uncovered vacancies in the Union since 2019, when vacancies were around 3.0% of the total employment, but increased to 5.7-5.3 in 2021 and continued to be a little higher during 2023 and 2024. Country lines show seasonal variations (Q2-Q3) in France, Italy and Greece, while the pattern in Portugal is more stable. The figures for Spain, white numbers in black cases show the lower rate of uncovered vacancies.

2.2.3. Sources of Data on Variables and Indicators

The secondary sources included the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI Mexico, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE Spain, with regional and global data drawn from the European Union statistics portal, Eurostat, and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, CEPALSTAT. Notably, a time series was used wherever possible to evaluate the impact of the pandemic over time; this approach necessarily sacrifices more granular and specific data available from many valuable studies conducted by institutions and consulting companies since their data collection and analysis methodologies did not allow for a comparative evaluation of the situation before and after the pandemic. This will be discussed further in the results section and the conclusions. In the case of private companies, information was collected from primary sources (interviews with company owners and managers conducted by the research team; specifically, five in Mexico and four in Spain) and secondary sources, including company publications and data from the Orbis-Bureau van Dijk and the Bolsa Mexicana de Valores (BMV).

3. Results, Validation of the propositions

3.1. Group 1 of Propositions. Company Actions During the Pandemic and Recovery Periods

This proposition is validated by considering the experiences and results of the three business groups described below. The company's actions were categorized according to Porter's value chain (1985) and evaluated in terms of dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2007), with a focus on talent management strategies that were particularly singular during this period (Presti & Mendes, 2023).

3.1.1. Mexico. CMR & ALSEA

The selected companies were the ALSEA, which was founded in 1997 and has since expanded internationally (ALSEA, Memoria 2022), and CMR, Corporación Mexicana de Restaurants, which was founded in 1965, was one of the first Mexican restaurant chains. These two companies were chosen because of the similarity of their businesses, the creation and management of food and beverage services companies, despite their differences in size (employees and turnover, see

Table 6), and their geographical locations, multinational or Mexico. Both companies are listed on the stock market and are headquartered in Mexico. According to specialists in the sector, these companies are leaders in their market segments and pursue different business strategies (ALSEA focuses on fast food and family restaurants, CMR for full-service restaurants) and thus provides complementary insights into the nature of the sector (Thomas, 2006).

A succession of closures and restrictions were ordered by the different national, state, and municipal governments in Mexico throughout 2020 and 2021 (alerts, closures, an orange/yellow alert system, restrictions on capacity and operating hours, with a relaxation in the fourth quarter, Deloitte, 2021). These factors had a significant effect on company activities, reflected in lost revenues (net income) and operating results (net income less operating costs) in millions of Mexican pesos (PMX) and market value (PMX per share), as indicated in

Table 6.

3.1.2. Spain. Gastronomía José María

Gastronomía José María is a family company based in Segovia (Autonomous Community of Castilla y León, Spain), which, in 2024, had various business liens (restaurant, farm, delivery, events, and catering) and 90 employees between kitchen and service staff, cleaning, maintenance, and administration. Between 2020 and 2021, the business was severely impacted by successive confinement orders and closures ordered by the central and community governments. Specifically, the city of Segovia has experienced long periods of confinement, which affects mobility and tourism, a key driver of the local economy. Data for sales, employment and operating results between 2018 and 2022 are provided in

Table 7 (source: eInforma).

According to the available data, both the ALSEA and CMR experienced a recovery in 2022 compared with revenues (sales in euros) before the pandemic (2019), which were 20% and 15%, respectively. This was not the case with Gastronomía José María, which experienced a decline of 3% from 2019. Several factors determine the pace of recovery, such as restrictions on mobility, consumer attitudes, levels of spending and frequency of visits (HdeE, 2022). In geographical terms, recovery was unequal because of the impact on tourism. In Spain, company closures were concentrated in the smallest segment of the market: bars (see the evolution of business demography in Table 9: In Spain, between 2018 and 2021, 3,188 bars closed and 50,950 jobs were lost, accounting for 10% of the total). Furthermore, new consumer habits, such as home delivery or takeout services, have largely benefitted restaurant chains, which have gained market share in Spain (KPMG report 2022). This confluence of circumstances may explain the lack of recovery in sales for Gastronomía José María, the principal business of which is a traditional restaurant located in the provincial capital and highly dependent on tourism.

In terms of employment, in 2022, the ALSEA reported 78,944 employees worldwide, representing a decrease compared with 2019 (81,126 employees). As in Mexico, the figure for 35,300 employees is lower (-10%) than that for 2019, with a stable ratio of women (48%). Globally, data show an increase in the employment of women from 48% to 49.4% as well as an increase in part-time contracts, with some 40% of employees working part-time compared with 36.4% in 2019. According to the 2022 Financial Report, the company continued offering salaries above the average for the sector, indefinite or permanent contracts, training, and commitment to personnel. Therefore, CMR is recognized by industry experts as a company that protects and works to retain talent (CMR, 2018 and 2019), with exceptional behavior during the pandemic in reaching agreements with other employers. This was reported by company managers but could not be confirmed by external sources. The company was able to retain 80% of its staff during the confinement period; however, the absence of data on employees in CMR's financial reporting and company data suggests that this type of data is not considered relevant for companies listed on the Mexican stock market. In this context, CMR is no exception. For Gastronomía José María, employment was not completely recovered, and the company had fewer employees in 2022 (90 persons) than in 2019 (94).

The ratio of operating results to sales was greater in 2021 and 2022 than in 2019 for both the CMR and ALSEA, which demonstrates the effectiveness of innovations in the value chain and business models that have attracted more young, urban clientele (development of apps for an internal home delivery service, adaptation of the supply chain, closure of less productive business units, etc.). However, the markets have punished both companies, especially CMR (which, despite reaching a share price of 3.11 PMX in 2023, has been on a downward trend, with a share price of 1.4 PMX in July 2024, below that of 2019; ALSEA reached 65.96 PMX per share in 2023, remaining stable in 2024). Nevertheless, the sector remains attractive for investors considering the difficulties in financing experienced by most companies (Sharma et al., 2023). With respect to Gastronomía José María, in 2022, the owners undertook operations to spur growth financed through capital expansion and debt; this combination of actions, along with a reorganization of operating accounts, has meant that the company has been classified as highly resilient with low risk, better than the sector, but its EBIT on sales in 2022 was 7.7%, lower than that in 2019 (12.6%; eInforma).

The analysis of the actions undertaken by these three organizations during the pandemic and recovery periods, presented in

Table 1, can be classified as follows: 1. capacity for adaptation (AD), in which existing resources are redeployed; 2. flexibility (FL), in which resources are modified, augmented or reduced; and 3. innovation (IN), in which the company acquires new capacities oriented toward gaining competitive advantage. We observed that the actions in IN were more common in CMR, two being unique in the sector: harnessing dormant resources, service in cinemas, and transferring employees to other companies, with shared salary schemes. The three business groups were effective in adapting (AD) and redeploying resources in accordance with the macro environment (Salem et al., 2021): Gastronomía José María adapted to a scenario that involved support but also restrictions imposed by the central government, whereas the ALSEA took advantage of the greater flexibility in Mexican regulations to carry out layoffs. This negative practice in talent management did not result in slowed business recovery or hindered growth in employment (compared with CMR and Gastronomía José María).

The organizations that survived the crisis did so by demonstrating their sources of competitive advantage within an adverse business environment for all (Aguinis et al., 2023; Bamiatzi & Kirchmayer, 2014). ALSEA's preexisting advantages (size, multi-location, multi-business) enabled it to adapt its human resources policies to local regulations without undermining its attractiveness as an employer in Mexico and benefiting from rapid recovery. The CMR's smaller size and established management talent policy led the company to undertake differentiating and innovative actions that enabled it to recover from the crisis at the same speed as its larger competitor. However, this was not enough to avoid punishment by investors within the context of generalized market uncertainty. Gastronomía José María demonstrated the capacity to adapt to negative circumstances, leveraging its strengths and sources of competitive advantage as a local, family-run business: the shared values of owners and employees (Yeon et al., 2021); however, the recovery was slower than in the sector as a whole in Spain, possibly owing to the more prolonged restrictions imposed in Segovia.

Thus, with the examples of these three organizations, we cannot confirm Proposition 1a: Companies with talent management practices deemed negative for employees have fewer dynamic capacities, delayed economic recovery, and greater employee attrition. The case of the ALSEA demonstrates that preexisting resources and capacities allowed the company to compensate for the potential negative impact of these practices on company results. The examples of CMR and Gastronomía José María confirm Proposition 1b: motivated employees accept changes in their functions and routines, adapt to new circumstances, maintain their ties to the company and remain available to face the challenges of recovery.

3.2. Group 2 of Propositions. Relationship Between Industry Structure and the Impact of the Pandemic on Companies and Employment

Propositions 2a and 2b posit that a hostile or unfavorable industry structure delays business recovery and increases employee attrition, whereas a welcoming, favorable structure leads to faster economic recovery and the retention of employees. As shown in

Table 5, the evolution of revenues (2022/2019) is negative in Mexico, whereas in Spain, it remains positive in nominal terms (12.97%) but does not consider inflation (14.4% from January 2019 to December 2022, INE).

Successfully overcoming the crisis requires greater and better deployment of company resources (Bamiatzi & Kirchmaier, 2014), which are not distributed uniformly. Approximately 29% of players in the global tourism sector are self-employed entrepreneurs, and an additional 29% are micro-companies with fewer than 9 employees (Ryder, 2020). The immediate impact of lost revenue due to confinement is greatest for small companies with limited capital (Carvalho & Valdés, 2020; Chetty et al., 2020; Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021). In Mexico, the number of business units grew by 5.9% between 2019 and 2022, which was greater than the total number of employees (0.40%), as did the number of company closures (24.9% in services in 2020). In Spain, the number of active companies, according to the INE (DIRCE,

Table 5) as of January 2023, was lower than that in January 2019 (231,898 compared with 252,011), and the number of local companies was lower.

The sector represents 12.2% of all Mexican companies and 7.2% in Spain, the vast majority of micro-companies (95%) with fewer than 9 employees (DIRCE-INE, 2022; INEGI, 2021). This atomization of the sector responds to the realities of consumer habits: Mexican taquerías and Spanish bars and cafés are generally small, with fewer than three employees, solidly embedded in local communities, and where clients consume light food and beverages in an informal atmosphere. These establishments account for 33% of the sector in Mexico (55% if stalls serving

antojitos are included) and 64.7% in Spain.

Table 8 compares both countries' number of companies and employees by type of service in the pre pandemic (2018) and post pandemic (2021) periods. Bars and taquerías include cafés, bars, taco and torta stands, etc. Restaurants include fast food outlets,

antojitos, full-service restaurants, and takeaway services. The collectives are institutional services, events, and catering. In Spain, the greatest losses in business units were in the subsector of bars and coffee shops. In Mexico, even though the absence of government support and the lack of resources for small units caused the closure of an estimated 120,000 establishments in 2020 (Deloitte, 2021), the dynamism of the industry produced an increase in the number of establishments: 641.279 in 2021 and 674.826 in 2022, compared with 584,023 in 2018. In Spain, there was shrinkage of the sector and greater concentration, with large companies and hospitality groups gaining market share, from 25% in 2019 to 31% in 2021 (KPMG, 2022).

(1) Registered firm

In Mexico, the sector accounted for 8.5% of the workforce in 2023 (DataMéxico) and is largely characterized by self-employment in microcompanies created by entrepreneurs and their families (66% of entrepreneurs are women). In Spain, the sector employs 1.22 million people, 5.9% of the workforce in 2022, the majority of whom are women (52.2%), many working part-time, with a lower percentage of female entrepreneurs (45.2%) (INEGI, 2019, 2021; Data México; HdeE, 2023). This inclusivity, which may make the sector more attractive, coincides with poorer working conditions than other sectors of the economy: in the case of Mexico, the average monthly salary of 4,740 PMX is below the average for all other occupations (ratio of 0.92); in Spain, the ratio is worse, where the average yearly wage for food and beverage services is below the average for all sectors of the economy (0.56) and decreases during the analyzed period (2015--2022). Employees in this sector work for informal companies (Mexico) in a greater proportion than do those in all other sectors; there are more part-time or partial contracts (Spain), and women earn less than men do (the salary gap is over 20% in Mexico and Spain).

The data provided in

Table 2 suggest that the structure of the industry can be classified as globally negative or hostile in Spain, with less market dynamism and a greater weight of large companies in terms of revenues, and moderately favorable or welcoming in Mexico, where there is more dynamism and large companies have less weight. The systematic evaluation of the business environment during the period 2015--2023 reveals that the sector suffers from structural shortcomings, such as the concentration of small companies (fewer than 4 employees in Mexico) and the high proportion of employee unremunerated family members (Mexico) that are somewhat disguised by a 5.8% annual growth rate in Spain and 5% in Mexico in the years prior to the pandemic, 2015-2019 (INE, INEGI).

The results, therefore, confirm that the unfavorable structure of the sector slows recovery (proposition 2a) in the case of Spain, with fewer companies and employees in 2022 than in 2019, although the indicator for unfilled vacancies (see Figure IV) is lower than that in other countries in the EU27.

In the case of Mexico, the number of employees is lower in 2022 than in 2019, accompanied by a wish of current employees to abandon the sector (OCCMundial, 2021) and high rates of staff rotation (Memoria ALSEA 2022). The impact of the lack of economic activity on employment in Mexico, represented in Figure III, leads us to infer that, in line with the Beveridge curve (low percentage of unemployment, higher number of job vacancies), employees may opt for other employment or even create their own company, explaining the greater growth in the number of companies without an accompanying increase in the number of persons employed in the sector. Thus, proposition 2b is not confirmed in its entirety: the favorable structure of the sector increases the number of companies but not in terms of income or attracting employees.

3.3. Group 3 of Propositions. Effect of Institutional Decisions on Companies and Employment

The first estimations on the impact of confinement and mobility restrictions on the tourism sector, produced by various authors, anticipated losses of between 45% and 70% (Ryder, 2020), depending on the duration and stages of these restrictions (Carvalho & Valdés, 2020; Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021), measured in terms of value, production and working hours. A study by Sharma, Lee and Lin (2023) estimated a decline in sector profits in the United States of approximately 50%, whereas Verick, Schmidt-Klau and Lee (2022, p. 160) estimated that, in 2021, the hospitality sector lost approximately 9.4% of employees, compared with 7.9% for the industrial sector and 3.3% for the retail sector. In Spain and Mexico (

Table 3), the majority of nonessential economic activity was suspended between the 11th and 16th of March 2020, gradually recovering in 2021, with differences at the meso level (municipality, region, and state), which are extremely important in a federal structure (states and autonomous communities) where decisions are decentralized.

The measure of institutional support in terms of percentage of GDP was significantly lower in Mexico than elsewhere (0.6%, compared with 11.8% in the USA). Soares & Berg, 2022). Employment protection measures were thus left in the hands of companies, which, furthermore, received no fiscal support for the retention of their employees (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021). According to a survey on the impact of the pandemic conducted by INEGI, 73.8% of restaurant companies reported responding to the decrease in revenues by cutting both staff (18.4%) and salaries (13.2%). The decrease of 29.3% in the turnover of food and beverage services reduced their contribution to GDP from 1.11% to 0.87% between 2019 and 2020 (INEGI, 2021). Spain applied measures similar to those of other European countries: support for business recovery, although with an investment in terms of the percentage of GDP below the European average (1.46% of GDP compared to the European average of 2.43%), and employment protection, using ERTE mechanisms (Expediente de Regulación Temporal de Empleo), which allowed companies to furlough employees with 70% of the salary paid by the state. The combined impact of restrictions and support can be measured in the contribution of the sector to GDP, which decreased from 4.4% in 2019 to 2.9% in 2020 and then increased to 4.2% in 2022.

Propositions 3a and 3b, which posit the effect of institutional measures on economic recovery and the support provided to companies and employees, should be considered in light of the varying nature of the actions taken between the critical moment of the pandemic, when restrictions on mobility were taken at the national level, and the de-escalation period, when decisions were left in the hands of the states or regions. Hoehn-Velasco, Silverio-Murillo and Balmori de la Miyar (2021) reported that the varying scenarios for reopening the economy in different states and cities in Mexico, from May 2021 onward, contributed to greater uncertainty and more difficulties in recovering economic activity and employment. In Spain, the Community of Madrid relaxed restrictions before other communities, but this greater flexibility did not translate into higher survival rates for companies (17.3% closed) or entrepreneurs (13.3% ceased their activity) in 2021. Similarly, company turnover did not return to prepandemic levels (-31.9% in 2021 vs 2019, -24.4% in all of Spain), although employment did recover at a better pace than in the rest of Spain did (at the end of 2021, statistics revealed a 12.5% drop in the number of employees nationally, whereas in Madrid, the drop was 2.2%). The relaxation of restrictions, within a scenario of global uncertainty measures, has an uneven effect, partly due to differences between companies and partly because consumer confidence does not rebound until vaccinations become widespread (Moulton et al., 2021)

The data indicate that while institutional measures of shutting down establishments and restricting mobility had a positive effect on society by reducing the spread and mortality of the virus (JHU-CRC), they had a negative effect on the sector. However, the experience in the Community of Madrid and certain Mexican states does not permit complete confirmation of proposition 3a. The support measures enacted in Spain did not have a measurable positive effect compared with the absence of support in Mexico, neither in terms of business recovery nor in terms of employment. Thus, proposition 3b cannot be confirmed.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a significant challenge to companies, industries, and governments around the world, which are ecosystems (Chatzinikolaou et al., 2021) that operate within a complex network of interrelationships (Amorim et al., 2022). The non-confirmation of proposition 1b, positing that post pandemic economic recovery is hindered by poor labor practices, exemplified by the ALSEA (laying off 20% of staff and reducing salaries), leads us to reflect on the impact of other organizational factors (size, access to finance, localization; Sharma et al., 2023) on the results of their actions during the pandemic period (operations, commercialization, talent management, innovation, etc.; Lai & Cai, 2022). The example of Gastronomía José María, a medium-sized family business, offers insights into the mechanisms of adaptation and resilience activated in response to the crisis (Nguyen et al., 2022), whereas the example of CMR illustrates the evolution of a business model characterized by the creative management of available resources.

The selected cases demonstrate the importance of cultural context, social cohesion, and cooperation between professionals as key factors in recovery (Gkoumas, 2022), underscoring the importance of the ecosystem, the most immediate context in which the company operates. The results show the interrelation between institutional measures, analyzed in Proposition Group 3, and the measures taken by companies themselves: the greater the degree of institutional protection is, the greater the degree of business protection of employment and employee health and safety (Aguinis et al., 2023; Presti & Mendes, 2023). However, given the existence of different levels of political authority in decentralized states, as is the case in Spain and Mexico, macro analysis, at the national level, is insufficient to confirm the relationship between institutional action and the recovery of the sector and employment.

The study also confirmed that the structure of the industry is an important factor in the recuperation of employment: in a context of precarity and limited worker protection, referred to as “modern slavery” (Vaughan, 2023), poor business practices increase the probability of high rates of employee attrition with workers seeking alternatives outside the sector, thus prolonging the crisis (Costa et al., 2021). In contrast, responsible leadership, as in the case of Gastronomía José María, can effectively attenuate personal-organizational conflict during a crisis (Salem et al., 2021). Even when the structure of the sector is unfavorable to employees, the example of Mexico demonstrates that companies with a reputation for providing decent wages and working conditions remain attractive employers (Bagheri et al., 2022).

Considering proposition 2a, positing that a hostile industry structure is a predictor of a reduced number of companies, value and employment (Maylín-Aguilar & Montoro-Sánchez, 2021), and group 3 propositions on the impact of institutional actions, the study revealed that the lack of equity in the support provided to companies depending on their size and access to resources largely determines the pace and solidity in the recovery of business and employment and reinforces inequalities within the industry (Verick et al., 2022). The case of Mexico demonstrates that an industry structure favorable to business and unfavorable to employees, restrictive measures, and the failure to provide support for companies and employment (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2021) has further eroded the favorable characteristics (growth, self-employment, etc.) of the sector, which required two years to return to pre pandemic levels of employment (2019) and has yet to return to precrisis levels of revenues (2023). In the case of Spain, the lack of granularity in support measures within an asymmetrical industry unfavorable to small businesses, along with changes in consumer habits, accelerated the loss of bars and increased the weight of large companies and franchises in the sector (Yang et al., 2022). The increase in the number of companies in Mexico, but not in total employment, suggests that self-employment is the solution of choice in a sector with virtually no significant barriers to entry (27.3% in España in 2022 and 38% in Mexico) and high levels of business mortality accentuated by the crisis (in Mexico, closures rose from 20.8% to 24.9% between 2019 and 2020, one in four companies, the same proportion as in Spain). Prospectively, the increase in the number of companies without employees, with limited access to financing, will continue to fragment the industry and further accentuate the asymmetry and unfavorable characteristics of the sector..

5. Conclusions, Implications, Limitations and Future Research

The first implication is the importance of meso analysis, that is, an understanding of the structure of the sector at its most basic level, characterized by fragmentation and asymmetry. Here, the impacts of severe demand shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on business and employment sustainability are revealed. The use of various measurements for the same variable offers a more precise view of the results. Thus, in line with the Beveridge curve, the findings suggest that the ratio of job vacancies is closely linked to rising or falling demand in the job market. A dynamic vision of the situation before, during, and after the pandemic and the measures adopted in each case reveal the importance of conducting comparative studies of diverse local contexts, providing greater insight into the impact and potential viability of changes and innovations within the food and beverage service industry.

A multilevel analysis, taking a holistic approach, clarifies the link between the actions of companies and employees and institutional measures and restrictions: in Europe, most unemployed individuals continued to receive support during the de-escalation period and could expect to return to the sector, whereas in countries such as Mexico, workers and the self-employed were forced to seek alternatives, possibly risking their health and that of their families. In fact, Mexico was one of the countries with the highest mortality rates due to the pandemic.

During the crisis period and the post pandemic period, revealing the connections between restaurant companies and their sectorial and social environments was an important endeavor for educators in the field of culinary arts and hospitality management; the majority of the actions referred to in this paper were drawn from the teaching materials of the authors, who used different methods of analysis, evaluation and crisis management adapted to different learning levels. The models and methods applied here may help future researchers analyze and search for solutions in the sector that may also be applicable in other countries and other areas of the service sector.

Implications and lessons for business and public policy management

In an asymmetrical sector with a large presence of micro companies, generalized public policies are ineffective given that the majority of companies lack the resources to apply them. At the height of the pandemic, the lack of granularity in policies to support companies and entrepreneurs, the majority of whom are self-employed, resulted in many business failures. Throughout the de-escalation period, the ever-changing situation, measures to stimulate demand, and changing consumer habits resulted in a concentration of the market into several large companies and hospitality groups. Given the unique nature of this part of the hospitality industry, bars and restaurants, which make a significant contribution to GDP and are a fundamental element in the attractiveness of tourist destinations, deserve to have a more focused and adequate response to their needs.

An analysis of the sector indicates that economic recovery requires a dynamic capacity for adaptation and flexibility, offering innovations on the basis of active listening to clients and deployed by trained and motivated human talent dedicated to the organization. Referring to this active listening to clients, the cases studied here reveal differing attitudes within the restaurant industry: waiting for government support or taking vigorous action to save the business. Some best practices were identified, including adapting to new demands, effectively managing operations, working to safeguard employees' security, even working with other companies, preserving a positive work environment, and upholding the values of the organization. Differing attitudes reveal that differing sets of priorities and actions can have differing outcomes depending on the goals being pursued: financial results or economic sustainability, understood in broader terms associated with social sustainability: affordable food, decent work, and responsibility to the community. The slow pace of recovery in profits and punishment by financial markets suggests purely utilitarian attitudes and actions on the part of financial entities, suppliers, and consumers, without considering the social impact of these actions.

Limitations and future lines of research

The present work has certain limitations, the first being the inductive and multilevel nature of the study, which, while offering greater depth of analysis, also presents difficulties in the choice of methodology. However, from an academic and pedagogical point of view, it is extremely enriching and pertinent given that it introduces students to certain theoretical models (PEST analysis, organizing company operations according to the value chain) while offering insight into the scope of actions and policies at the meso-macro level via secondary sources from reputable public organizations.

The sector offers few attractions for employees, which poses a challenge to educators and educational institutions to confront the structural and cultural changes required in the sector, such as greater employee training, remuneration, and integration, reflecting the attitudes and aspirations of young people and facilitating the inclusion and professional advancement of women and migrants. Change involves the ecosystem as a whole, including the context in which the sector is held by clients and institutions and the recognition of the economic, cultural, and social importance of bars and restaurants in daily life. We hope these reflections will contribute to a multifaceted discussion among academics, entrepreneurs, and public officials on the need for change and renewal, which will enhance the health and resilience of this vital sector of the economy.6. Patents

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Fernández-de-Caleya, Ramos-Abascal and Maylín-Aguilar Y.Y.; data curation, Ramos-Abascal and Maylín-Aguilar; X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Maylín-Aguilar; writing—review and editing, Fernández-de-Caleya and Ramos-Abascal; funding acquisition, Fernández-de-Caleya. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding of the Spanish Government project PID2021 - 126516NB - I00, MCIN /AEI /10.13039/501100011033 / FEDER; Fundación Universidad Francisco de Vitoria and Santander Universidades.

Data Availability Statement

All secondary information and their sources are available as supplementary material in

www.mdpi.com

Acknowledgments

Authors’ acknowledge disinterested support and generous collaboration of current or former employees and managers of ALSEA, CMR and Gastronomía José María

First draft of ALSEA and CMR activities during pandemic was shared in the IX International AFIDE conference, 2021. Summary of the communication is published in Miradas sobre el Emprendimiento ante la crisis del coronavirus, ISBN 978-84-1377-995-9

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguinis, H.; Kraus, S.; Poček, J.; Meyer, N.; Jensen, S.H. The why, how, and what of public policy implications of tourism and hospitality research. Tour. Manag. 2023, 97, 104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALSEA, Memoria 2021 ‘Aprendemos del presente para ganar el futuro’. Memoria 2022 ‘El éxito está en los detalles’. Retrieved from www.alsea.net.

- Aloisi, A.; De Stefano, V. Actividades esenciales, trabajo a distancia y vigilancia digital. Estrategias para hacer frente al panóptico de la pandemia de COVID-19. Rev. Int. Del Trab. 2022, 141, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim WA C d Cruz MV G d Sarsur, A.M.; Fischer, A.L.; Lima, A.Z.; Bafti, A. The intricate systemic relationships between the labor market, labor relations and human resources management in a pandemic context. RAE-Rev. Adm. Empresas 2022, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamiatzi, V.C.; Kirchmaier, T. Strategies for superior performance under adverse conditions: A focus on small and medium-sized high-growth firms. Int. Small Bus. J. 2014, 32, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batat, W. How Michelin-starred chefs are being transformed into social bricoleurs? An online qualitative study of luxury foodservice during the pandemic crisis. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CANIRAC. (2020). Todo sobre la mesa. Dimensiones de la industria restaurantera en 2018. Ciudad de México.

- Carvalho, A.; Valdés, P. (2020). Impacto del COVID-19 en hostelería, en España. EY-Bain.

- Caves, R.E. Industrial organization, corporate strategy and structure. Read. Account. Manag. Control 1992, 335–370. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Demertzis, M.; Vlados, C. European entrepreneurship reinforcement policies in macro, meso, and micro terms for the post-COVID-19 era. Rev. Eur. Stud. 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Zou, S.; Chen, M.-H. The fear of being infected and fired: Examining the dual job stressors of hospitality employees during COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R.; Friedman, J.N.; Hendren, N.; Stepner, M.; Team, T.O.I. How did COVID-19 and stabilization policies affect spending and employment? A new real-time economic tracker based on private sector data; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 91. [Google Scholar]

- Corporación Mexicana de Restaurantes, CMR CMR ; 2018 El grupo restaurantero CMR explica cómo adaptarse a y sacar lo mejor del capital humano millennial (eleconomista.com.mx); 2019 Interview with J. Vargas, Forbes México.

- Costa JC da Sant’Anna, E.S.; Viana, J.P.; Fratucci, A.C. Trabalho (In)Decente no Turismo: Reflexões para a Construção de uma Agenda de Pesquisa. Rosa Dos Ventos 2021, 13, 1213–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespí-Cladera, R.; Martín-Oliver, A.; Pascual-Fuster, B. Financial distress in the hospitality industry during the Covid-19 disaster. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Semrad, K.; Rivera, M. (2021). The state of the hospitality industry 2021 employment report: Covid-19 legacy report. Working paper, October 27 2021. Dick Pope Sr. Institute for Tourism Studies, UCF-Rosen College.

- Çakar, K.; Aykolde, S. Case Study as a Research Method in Hospitality and Tourism Research: A Systematic Literature Review (1974–2020). Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 62, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque Meneguel, C.R.; Mundet, L.; Aulet, S. The role of a high-quality restaurant in stimulating the creation and development of gastronomy tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopfer, K.; Foster, J.; Potts, J. Micro-meso-macro. J. Evol. Econ. 2004, 14, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. What is the Eisenhardt Method, really? Strateg. Organ. 2021, 19, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (European Union statistical site). The Beveridge curve Job vacancy and unemployment rates - Beveridge curve - Statistics Explained (europa.eu).

- Fang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, B. The immediate and subsequent effects of public health interventions for COVID-19 on the leisure and recreation industry. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkoumas, A. Developing an indicative model for preserving restaurant viability during the COVID-19 crisis. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 22, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K.Y. COVID-19 and China’s Hotel Industry: Impacts, a Disaster Management Framework, and Post-Pandemic Agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn-Velasco, L.; Silverio-Murillo, A.; Balmori de la Miyar, J.R. The long downturn: The impact of the great lockdown on formal employment. J. Econ. Bus. 2021, 115, 105983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spanish national statistics bureau, INE (v.d.) www.ine.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Mexican bureau of statistics and geography, INEGI. (2021). Conociendo la industria restaurantera. Ciudad de México.

- John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (JHU-CRC) Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (jhu.

- Juergensen, J.; Guimón, J.; Narula, R. European SMEs amidst the COVID-19 crisis: assessing impact and policy responses. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2020, 47, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, M.S.; Goldberg, L.G.; Avery, J. (2020). Restaurant revolution: How the industry is fighting to stay alive. Harvard Business Education blog, hbs.

- Li, B.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Hua, N. Transcending the COVID-19 crisis: Business resilience and innovation of the restaurant industry in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Lastres, B.; Wen, H.; Huang, W.-J. A reflection on the Great Resignation in the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 35, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Choi, T.M.; Niu, X.Q.; Zhang, M.; Fan, W.G. Determinants of Business Resilience in the Restaurant Industry During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Textual Analytics Study on an O2O Platform Case. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 10427–10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maylín-Aguilar, C.; Ramos-Abascal, M.I.; Fernández de Caleya Dalmau, R. (2021) La hostelería ¿factor de cohesion sostenible en situaciones de crisis? Análisis de la actitud del emprendedor de restauración en megápolis mexicanas, presented at IX International AFIDE conference, 2021. Summary is published in Miradas sobre el Emprendimiento ante la crisis del coronavirus. ISBN 978-84-1377-995-9.

- Maylín-Aguilar, C.; Montoro-Sánchez, Á. The Industry Life Cycle in an Economic Downturn: Lessons from Firm’s Behavior in Spain, 2007–2012. J. Bus. Cycle Res. 2021, 17, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maylín-Aguilar, C.; Gómez-Lega, J.L. (2022). Taking care of those who care. Keeping internal motivation during pandemic in Gastronomía José María, Segovia, Spain, presented at the 17th International QUIS conference, 2022. Extended abstract is published in the conference proceedings. [CrossRef]

- McGinley, S.; Wei, W.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y. The State of Qualitative Research in Hospitality: A 5-Year Review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 62, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, J.; Smith, T.R.; Snezhkova, N.; Weissgerber, A. (2023). High hopes despite high prices: An update on European consumer sentiment. McKinsey & Company.

- OCCMundial (2022) Adaptabilidad laboral post-pandemia en México Available at https://www.occ.com.

- Okumus, B.; Köseoglu, M.A.; Ma, F. Food and gastronomy research in tourism and hospitality: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. (1985). The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, New York. Free Press.