1. Introduction

Water plays a vital role in human lives, however, water pollution and clean water shortage have become a global issue which are the results of industrial and agricultural activities [

1]. In recently years, the water pollution caused by organic compounds [

2,

3] such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) have become a significant issue. And many researchers found PAHs in various water systems, such as influent and effluent of chemical wastewater treatment plant, groundwater, surface water and even in the ocean [

4].

PAHs are aromatic hydrocarbons containing two or more benzene rings. PAHs could be produced by natural combustion such as forest or brush fires and human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels, vehicle emissions, cigarette smoke and industrial activities [

5]. Generally, PAHs produced by combustion and vehicle emissions diffuse into atmosphere first, and a part of it enter to soil or water as deposits. Different from the PAHs pollution in atmosphere, another important polluted source in water is the discharge of industrial wastewater, increasing the concentration of PAHs in water environment. Fluoranthene (FLN), phenanthrene (Phe), and pyrene (Pyr) are frequently in high quantities in water environment around the world according many references [

6,

7,

8,

9], these researches study the PAHs concentration from drinking water, rivers and lakes, chemical wastewater and even groundwater. It has been reported that the concentration of FLN, Phe, and Pyr in drinking water in China [

7] ranged from 0.004 mg/L to 0.021 mg/L, in Poland [

10] ranged from 0.010 mg/L to 0.050 mg/L. Liu et al. [

11] and Pan et al. [

12] investigated the PAHs in rivers and lakes from China and found the concentrations of FLN, Phe, and Pyr were ranged from 0.002 mg/L to 0.730 mg/L. Nasher et al. [

13] has found that the concentration of FLN, Phe, and Pyr in seawater of south China sea is 1.4, 0.6, 1.8 mg/L, respectively. Therefore, remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr from water environment is an urgent issue.

The treatments currently used to remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr from wastewater including biological, physical and chemical methods [

14,

15]. Biological methods including phytoremediation and bioremediation. According to the Reynoso-cuevas et al. [

16] study, 6.99% PAHs could be accumulated to the stem of F. arundinacea by phytoremediation methods meanwhile 20.66% has been accumulated to the root. Physical and chemical methods including adsorption and advanced oxidation process (AOPs), common adsorbents include activated carbon, bentonite, biochar, nano-tubes and so on [

17,

18,

19]; AOPs including Fenton oxidation, ozonation, electrochemical oxidation and persulfate (PS) oxidation [

20,

21]. Among them, the persulfate oxidation method is popular due to its economy and durability. And activated methods was used to improve the oxidation efficiency of PS [

22], including heat activation, microwave activation, and transition metal (Fe, Cu, Zn, Mn, etc.) activation.

The special hydrated iron oxyhydroxide rich in sulfate [

23] (schwertmannite, Fe

8O

8(OH)

x(SO

4)

y) was used with weak crystallinity and large specific surface area, it has been often used as adsorbent and catalyst. The schwertmannite (sch) is usually used for adsorption due to its large specific surface area. Liao et al. [

24] used sch to adsorb As(III) from groundwater and found that the maximum adsorption amount was 113.9 mg/g, and the adsorption of arsenic was not affected by other competing ions in the system. In recent years, sch have been widely used in the field of catalytic degradation of organic pollutants [

25,

26,

27]. The study found that the introduction of sch could make the degradation rate of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) in the Fenton system reach 88.9% in 1 h [

28], and the synergistic effect of sch and oxalic acid could remove 97% methyl orange from wastewater [

25]. Biochar also been extensively employed as a versatile adsorbent, and the bamboo-biochar showed the high adsorption rate by its microcrystalline structure with high porosity, fast adsorption and high active surface area [

29].

However, there are currently no reports on the schwertmannite catalyze persulfate remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr from wastewater. Furthermore, the sch synthesis with bamboo-biochar used to remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr from wastewater has not been explored yet. Therefore, this study focuses on: (1) different methods to synthesis schwertmannite; (2) compare the effects of schwertmannite synthesized with different methods (including treatment added bamboo-biochar) catalyzed PS on removal of FLN, Phe, and Pyr from wastewater. The realization of these goals has important theoretical and practical significance for control and remove the FLN, Phe, and Pyr from wastewater.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

Fluoranthene (>98 %), phenanthrene (>95 %), acetone (>99.5 %), FeSO4·7H2O (>99.0%), Na2S2O8 (>97%) and methanol (>99.5 %) are the Wako 1st Grade reagents, and they were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Japan, except fluoranthene provided by Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan; other reagents were Wako Special Grade, pyrene (>97 %), nonane (>98 %), and dichloromethane (>99.5 %) was obtained from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Japan; hexane (>99.5 %) was supplied by Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Japan; Pyrene-d10 (>99.99 %) was supplied by AccuStandard, USA; silica was provided by Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Japan; Deionized water was prepared by a w ater purifier (Direct-Q 3 UV, Millipore, USA).

2.2. Preparation of Sch with Three Synthesis Methods

The different types of sch were prepared by oxidation of ferrous sulfate solution with H

2O

2 following the methods of Liu et al. [

30]. In this research, we used the three methods to synthesis the special sch, first of all, prepare 150 mL of FeSO

4•7H

2O solution (160 mmol/L) following three methods:

- (1)

sch-1: add 1.8 mL H2O2 at 2 h;

- (2)

sch-2: add 0.36 mL H2O2 at 2, 14, 26, 38, and 50 h;

- (3)

sch@BC: add 1.8 mL H2O2 at 2 h, and add biochar (mFe2+: mBC=1:20) at 3 h.

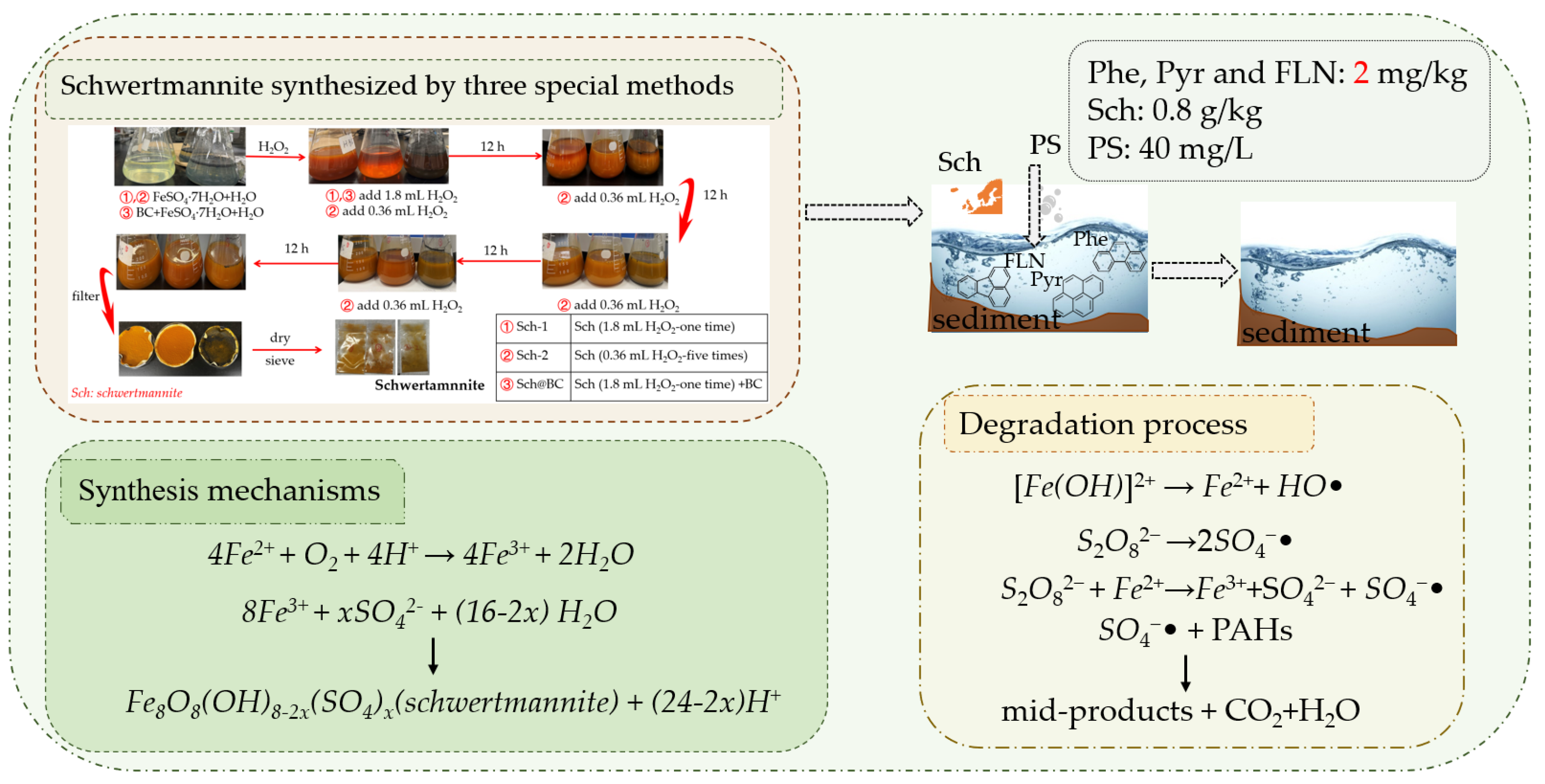

The precipitates formed by different treatments were collected after 60 h and oven-dried at 50°C to constant weight. The mineral was identified by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and X-ray diffraction (XRD). Moreover, the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) of Sch were also evaluated. The research process and degradation mechanisms of this study have been shown in

Figure 1.

The preparation method of biochar (BC) is as follows : bamboo has been ground through a 250 μm sieve, was collected from Anhui, China. Using single-step activation to synthesize biochar, bamboo powder is put into ceramic boat and set in a stainless horizontal tubular furnace under N

2 atmosphere condition with a 200 mL/min flow rate for 10 min to eradicate air and then activated at 800 °C for 1 h with a heating rate of 10 °C/min [

18].

In a series of Erlenmeyer flask with an effective volume of 250 mL, 12 treatments with a 50-mL total solution volume were set up as

Table 1. All treatments repeated 3 times and reacted for 3 h on a magnetic stirrer (RS-6DN, AS ONE company, Japan) with 1000 r·min

-1. Sampling was carried out at 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h, and passed through a 0.20-μm membrane filter. Add 150 μL methanol to quench free radicals, then extraction FLN, Phe, and Pyr from wastewater and GC-MS was used to determine the contents of FLN, Phe, and Pyr according to the method [

31].

2.3. Analytical Methods

Rotavapor (R-100, Buchi, Germany), interface (I-100, Buchi, Germany) and heating bath (B-100, Buchi, Germany) were used for the concentrated extraction of FLN, Phe, and Pyr; while GC-MS instrument (6890A (G1530A), Agilent, USA) for the concentration determination of FLN, Phe, and Pyr in the extract. A 0.25 mm internal diameter (i.d.) x 30 m length column with 0.25 μm film thickness, specifically an Intertcap 17 column, was employed for Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) investigations. The GC system utilized an HP6890 GC interfaced with a 5973 MSD detector. The initial temperature of the column was set at 40°C keep 2 minutes, and rise to 200°C with a ramp rate of 15°C /min, subsequently increasing to 320°C at a rate of 5°C /min. Helium with high purity was the carrier gas at a flow of 1 mL/min. MS spectra were acquired at the electron ionization mode with an electron multiplier voltage of 70 eV. The mass scanning raged between m/z 45 and 350. Chromatographic peaks of samples were identified by NIST 98 mass spectra library.

Additionally, Mineral phase analysis was performed with power X-ray diffraction (XRD, MiniFlex II, Tokyo, Japan). Morphology was observed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM, S-4800, Hitachi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The chemical bonds of Sch were determined by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (IR-6100, JASCO Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The mineral specific surface area was obtained using an automatic specific surface area and pore analyzer (BELSORP-miniX-TKS0, MicrotracBEL Corp., Osaka, Japan). Sulfur was determined by an integrated sulfur analyzer (HYDL-9, Hebi Huayu Instrument Co., Ltd., Henan, China). Descriptive statistics were performed using Microsoft Excel 2019. Data analysis was conducted with Origin 2016 software package.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Sch

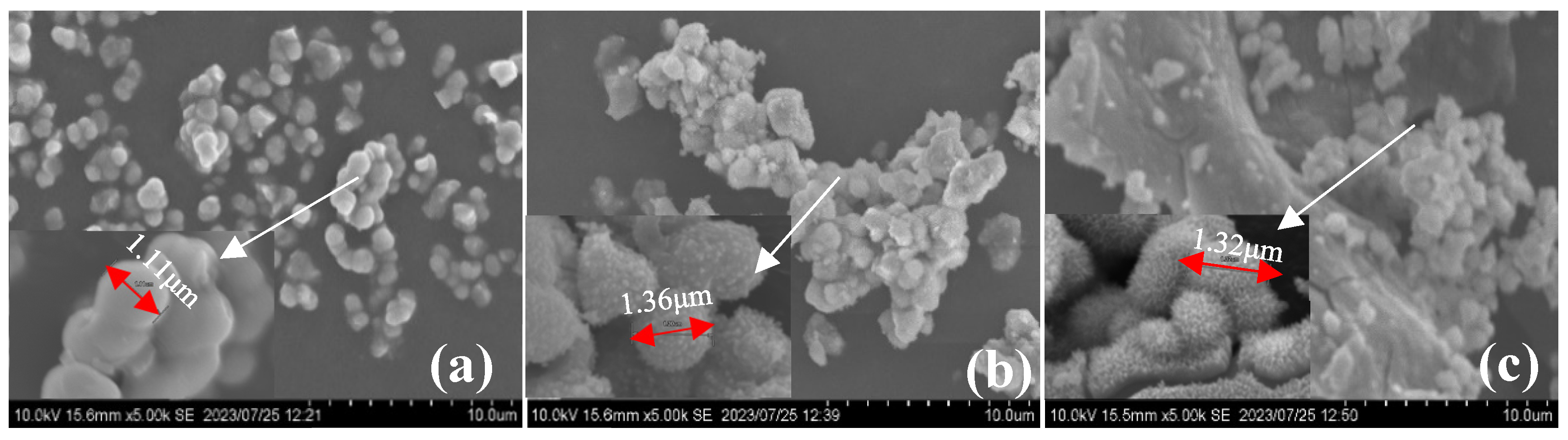

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image ( × 5000) of sch-1 has been shown in

Figure 2a, sch-1 was spherical aggregates with smaller particle diameters, and it is smooth, which is the typical morphology of chemical synthesized schwertmannite.

Figure 2b shows the SEM image (× 5000) of sch-2, it could be found that sch-2 surface is rough and has burrs, which is consistent with the morphology of Sch observed by Liu et al. [

30]. The SEM image (× 5000) of sch@BC was shown in

Figure 2c, the composites had a prominent aggregate structure, the sch has covered the surface of BC, which was similar to the morphology of minerals synthesized by others [

32]. The cells diameter of sch-1, sch-2, and sch@BC were measured under SEM image (× 30000), 1.11 μm, 1.36 μm, and 1.32 μm, respectively.

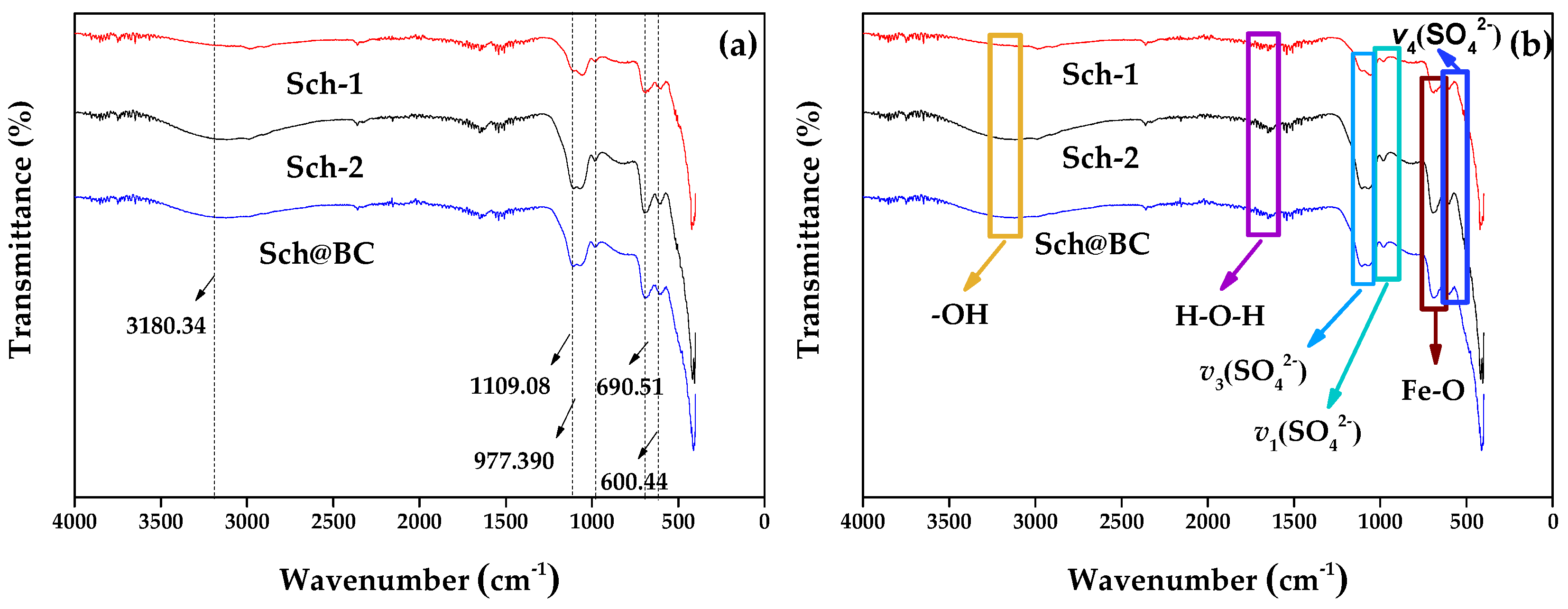

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) has been shown in

Figure 3, the contraction vibration peak at 3180.34 cm

-1 is the hydroxyl group (-OH) on the sch surface. The triple degenerate asymmetric absorption peak

ν3(SO

42−) of the sulfate ion of schwertmannite is shown as a broad peak of contraction vibration at 1109.08 cm

−1. The inner symmetric contraction peak at 977.39 cm

−1 is

ν1(SO

42−). Both

ν1(SO

42−) and

ν3(SO

42−) are considered to be the sulfate groups externally complexed by schwertmannite. The absorption peak of

ν4 (SO

42−) at 600.44 cm

−1 is the sulfate inside the tunnel of schwertmannite. The results show that the contraction vibration peak at 690.51 cm

−1 is the Fe-O absorption peak. These peaks were similar to the morphology of minerals synthesized by others [

33].

Figure 4 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of sch is shown in

Figure 3, and the characteristic diffraction peaks of sch appear at 2

θ =18.24°, 26.26°, 35.16°, 39.50°, 46.54°, 55.30°, and 61.34°. It could see rom

Figure 3 that three types of minerals have no sharp and strong peaks, they have wide peaks and more burrs. Compare this with the standard XRD diffraction peaks of sch (JCPDS: PDF47-1775). It is certain the three minerals synthesized in this study are sch.

Table 2 shows the BET and formulae of different sch. The BET of sch-1, sch-2, and sch@BC is 1.09 m

2/g, 11.30 m

2/g, and 6.10 m

2/g, respectively. And the sch-2 has highest pore volume is 7.35* 10^-2 cm

3/g, followed by sch@BC is 1.50* 10^-2 cm

3/g, and pore volume of sch-1 is 1.09*10^-2 cm

3/g. The mean pore diameter of sch-1, sch-2, and sch-BC is 22.85 nm, 25.99 nm, and 9.86 nm, respectively. It also could be found that the molar ratio of Fe/S in sch-1, sch-2, and sch@BC were 4.66, 4.72, and 6.59 respectively. And the formulae of sch-1, sch-2, and sch@BC were determined as Fe

8O

8(OH)

4.56(SO

4)

1.72, Fe

8O

8(OH)

4.61(SO

4)

1.70, and Fe

8O

8(OH)

5.48(SO

4)

1.21, respectively.

3.2. Sch with Different Methods Catalyze Persulfate to Control FLN, Phe, and Pyr from Wastewater

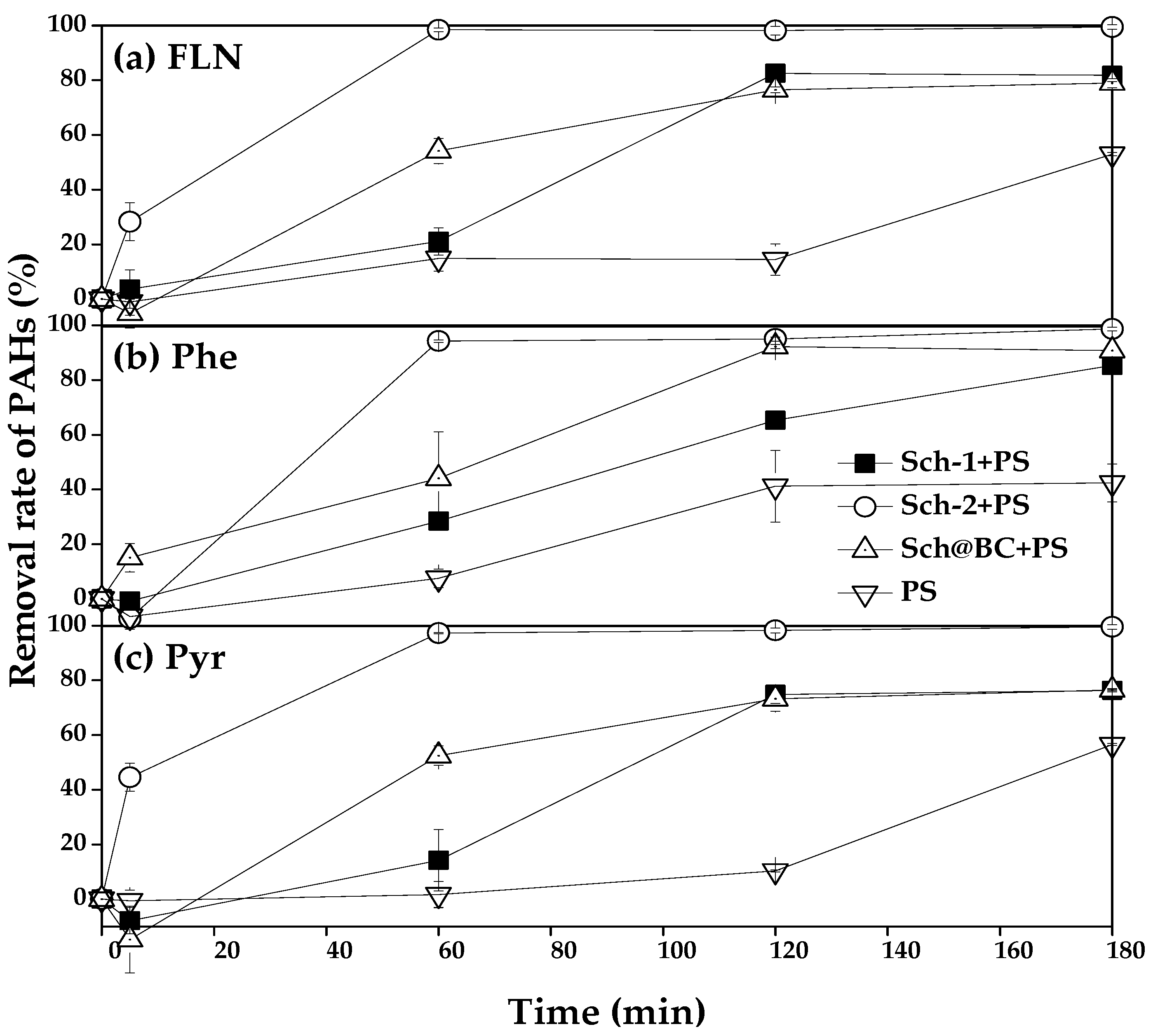

PS remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr catalyzed by different sch has been shown in

Figure 5, it could see that the removal rate of FLN in treatment which added sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, and sch@BC+PS after react 1 h was 21.1%, 98.5%, and 54.2%, respectively, from

Figure 5a, meanwhile the removal rate of FLN is 14.8% in treatment which only add PS. After react 2 h,the removal rate of FLN in treatment which added sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, sch@BC+PS, and PS was 82.6%, 98.1%, 76.5%, and 14.5%, respectively. After react 3 h, the removal rate of FLN in treatment which only added PS has increase to 53.0%, and in other treatment which added sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, sch@BC was 81.8%, 99.5%, 78.9%, respectively.

Figure 5b shows the PS catalyzed by different sch to remove Phe, and it could be found that 28.4%, 94.3%, 44.1%, and 7.6% of Phe has been removed after react 1 h in the treatment of sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, sch@BC, and PS, respectively. The removal rate of Phe in treatment of sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, sch@BC, and PS was 65.3%, 95.0%, 92.2%, and 41.2%, respectively, after react 2 h. And after react 3 h, the removal rate of Phe in sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, and sch@BC were 85.4%, 98.7%, and 90.8%, respectively, but in treatment which added PS only, the removal rate of Phe is only 42.4% after react 3 h. The removal rate of Pyr has been shown in

Figure 5c, it could find that after react 1 h, sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, sch@BC, and PS could remove 14.2%, 97.2%, 52.5%, and 1.7% Pyr, respectively. And after react 2 h, the removal rate of Pyr in treatment of sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, sch@BC, and PS was 74.8%, 98.2%, 73.2%, and 10.3%, respectively. After react 3 h, the removal rate of Pyr in treatment which added sch-1+PS, sch-2+PS, and sch@BC was 76.3%, 99.5%, and 76.5%, respectively, and the removal rate of Pyr is 56.5% in treatment of PS after react 3 h.

Figure 6 shows the SEM image ( × 5000) of sch-1, sch-2, and sch@BC after reaction, the surface of schwertmannite has no obvious change and is still slightly rough, appearing as spherical aggregates with burrs, compared with the SEM of schwertmannite before the reaction. The cells diameter of sch-1, sch-2, and sch@BC after reaction were measured under SEM image (× 30000), 1.30 μm, 1.44 μm, and 1.40 μm, respectively.

4. Discussion

As is shown in

Table 2, sch-2 has a larger BET (11.30 m

2/g) compared with sch-1 (1.09 m

2/g) and sch@BC (6.10 m

2/g), combined with the FTIR shown in

Figure 3, the vibration peak of sch-2 is stronger, the -OH vibration peak of sch-2 fluctuates greatly, which indicates that there are more externally bound hydroxyl functional groups, and the

ν3(SO

42−) and

ν4(SO

42−) stretching vibration peaks of sch-2 fluctuate greatly, indicating that it have more internally and externally complexed SO

42−. Wang et al. [

34] has found that the sch with stronger vibration peaks have more binding site. Therefore, it could be indicated that sch-2 has more binding sites, which makes it have better adsorption and catalysis performance. According to

Figure 5, it could be found that the treatment only added PS, it could only remove 53.0% FLN, 42.4% Phe, and 56.5% Pyr after react 1 hour, respectively. It is due to that S

2O

82- in PS could produce SO

4-• (Eq. (1)). When added sch in to the wastewater, whatever which kind of sch, the removal rate of FLN, Phe, and Pyr all better than the treatment only added PS, this is because sch could produce Fe (II) (Eq. (2)) [

35], which could react with S

2O

82- to produce more SO

4-• (Eq. (3)) [

23,

36]. Many researchers [

37,

38,

39] found that Fe could active S

2O

82- to produce more SO

4-•, which is similar to the results of this study. And the sch used in this study has a large amount of Fe, which could continuously supply Fe for the activation of S

2O

82- .

And it could be found that sch-2 has best capacity on catalyze persulfate to remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr. Added sch-2 after 1 hour could remove 98.5% FLN, 94.3%Phe, and 97.2% Pyr by catalyze PS, respectively. And after react 3 hour the removal rate of FLN, Phe, and Pyr were 99.5%, 98.7%, and 99.5%, respectively. It is due to that sch-2 has more binding sites, which could promote the S

2O

82- produce SO

4-• rapidly than others, and then SO

4-• could react with FLN, Phe, and Pyr to destroy their structures. And the -OH on the surface of sch also could react with SO

4-• to produce HO• (Eq. (4)), HO• could also destroy the structure of FLN, Phe, and Pyr and control them from wastewater. Wang et al. [

23] discovered the same mechanism when studying the activation of persulfate by sch to remove oxytetracycline.

In summary, the remove rate of FLN, Phe, and Pyr by PS is slowly. The addition of sch greatly improves the removal rate of FLN, Phe, and Pyr by PS, and the sch with more binding sites has a better catalytic effect.

5. Conclusions

In this study, schwertmannite was synthesized by three special methods, and use sch catalyze PS to remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr from wastewater, and found that (1) Sch synthesized by add 0.36 mL H2O2 five times (sch-2) has the biggest BET (11.3 m2/g); (2) Sch-2 shows the best capacity on catalyze persulfate to remove FLN, Phe, and Pyr. Therefore, sch (synthesized by add 0.36 mL H2O2 five times) is an excellent catalytic material for PS to control FLN, Phe and Pyr from chemical wastewater.

Author Contributions

Yanyan Wang: Validation and Writing-Original draft preparation; Weiqian Wang: Data Curation, Visualization; Fenwu Liu: Methodology and Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Qingyue Wang: Project administration, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision; Shangrong Wu: Validation。

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Special Funds for Innovative Area Research (Number. 20120015, FY2008-FY2012) and Basic Research (B) (Number. 24310005, FY2012-FY2014; Number. 18H03384, FY2017-FY2020; Number. 22H03747, FY2022-FY2024) of Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Y. W], upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Comprehensive Analysis Center for Science, Saitama University for allowing us to conduct some analyses and providing insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors (Yanyan Wang, Qingyue Wang, Weiqian Wang, Fenwu Liu, Shangrong Wu) declared that they have no conflicts of interest to this work. We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

References

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Cui, B.; Bai, J.; Zhang, W. Size effect of polystyrene microplastics on sorption of phenanthrene and nitrobenzene. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 173, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edokpayi, J.N.; Odiyo, J.O.; Durowoju, O.S. Impact of Wastewater on Surface Water Quality in Developing Countries: A Case Study of South Africa. In Water Quality; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 401–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Nguyen, K.A.; Vu, C.T.; Senoro, D.; Villanueva, M.C. Contamination levels and potential sources of organic pollution in an Asian river. Water Sci. Technol. 2017, 76, 2434–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandclément, C.; Seyssiecq, I.; Piram, A.; Wong-Wah-Chung, P.; Vanot, G.; Tiliacos, N.; Roche, N.; Doumenq, P. From the conventional biological wastewater treatment to hybrid processes, the evaluation of organic micropollutant removal: A review. Water Res. 2017, 111, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojiri, A.; Zhou, J.L.; Ohashi, A.; Ozaki, N.; Kindaichi, T. Comprehensive review of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water sources, their effects and treatments. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olayinka, O.O.; Adewusi, A.A.; Olarenwaju, O.O.; Aladesida, A. Concentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Estimated Human Health Risk of Water Samples Around Atlas Cove, Lagos, Nigeria. J. Health Pollut. 2018, 8, 181210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, B.; He, Z.; Li, L.; Shi, H.; Wang, M. Enantioselective metabolism of four chiral triazole fungicides in rat liver microsomes. Chemosphere 2019, 224, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A.S.; Oyekunle, J.A.O.; Ojo, O.S.; Maxakato, N.W.; Olutona, G.O.; Obisesan, O.R. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon levels of groundwater in Ife north local government area of Osun state, Nigeria. Toxicol. Rep. 2016, 4, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C. The distribution and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in shallow groundwater from an alluvial-diluvial fan of the Hutuo River in North China. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 13, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabzinski, A.K.M.; Cyran, J.; Juszczak, R. Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Water (Including Drinking Water) of Lodz. Pol. J. Environ. Stud 2002, 11, 695–706. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, J.; Chen, Z.; Ren, N.; Li, Y. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface water and sediment near a drinking water reservoir in Northeastern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 20, 2535–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, E.C.; Sun, H.; Xu, Q.J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.F.; Chen, X.D.; Xu, Y. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Concentrations in Drinking Water in Villages along the Huai River in China and Their Association with High Cancer Incidence in Local Population. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 762832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasher, E.; Heng, L.Y.; Zakaria, Z.; Surif, S. Concentrations and Sources of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Seawater around Langkawi Island, Malaysia. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 975781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayanand, M.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Subramanian, R.; Issac, P.K.; Nasr, M.; Khoo, K.S.; Rajagopal, R.; Greff, B.; Azelee, N.I.W.; Jeon, B.-H.; et al. Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the water environment: A review on toxicity, microbial biodegradation, systematic biological advancements, and environmental fate. Environ. Res. 2023, 227, 115716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Han, Y.; Duan, Y.; Lai, X.; Fu, R.; Liu, S.; Leong, K.H.; Tu, Y.; Zhou, L. Review on the contamination and remediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coastal soil and sediments. Environ. Res. 2021, 205, 112423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoso-Cuevas, L.; Cruz-Sosa, F.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, M. In vitro phytoremediation mechanisms of PAH removal by two plant species. In: Haines, P.A., Hendrickson, M.D. (Eds.), Book: Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Pollution, Health. Nova Science Publishers, US. 2010.

- Karaca, G.; Baskaya, H.S.; Tasdemir, Y. Removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from inorganic clay mineral: Bentonite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 23, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, Q. Investigation of Pyrolysis/Gasification Process Conditions and Syngas Production with Metal Catalysts Using Waste Bamboo Biomass: Effects and Insights. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkiewicz, M.; Sikorska, C.; Leszczyńska, D.; Stepnowski, P. Helical multi-walled carbon nanotubes as an efficient material for the dispersive solid-phase extraction of low and high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from water samples: Theoretical study. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayaroth, M.P.; Marchel, M.; Boczkaj, G. Advanced oxidation processes for the removal of mono and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons–A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, G.K.; Mehmood, T.; Kumar, M.; Cheng, L.; Sathishkumar, K.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, D. Review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) migration from wastewater. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2021, 236, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons degradation mechanisms in methods using activated persulfate: Radical and non-radical pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Bi, W.; Qin, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Fu, P.; Liu, F. Schwertmannite catalyze persulfate to remove oxytetracycline from wastewater under solar light or UV-254. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.H.; Liang, J.R.; Zhou, L.X. Adsorptive removal of As(III) by biogenic schwertmannite from simulated As-contaminated groundwater. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, J.; Jiang, D.J.; Zhou, P.; Lan, Y.Q.; Zhou, L.X. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange in schwertmannite/oxalate suspension under UV irradiation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 2313–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.Y.; Yu, B. Rapid ferric transformation by reductive sissolution of schwertmannite for highly efficient catalytic degradation of Rhodamine B. Materials 2018, 11, 1165–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Zheng, G.Y.; Meng, X.Q.; Zhou, L.X. Assessment of catalytic activities of selected iron hydroxysulphates biosynthesized using Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans for the degradation of phenol in heterogeneous Fenton-like reactions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 185, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.X.; Yu, K.; Xu, J.Y.; Cai, Y.L.; Li, Y.F.; Cao, H.L.; Lü, J. Engineered nanoscale schwertmannites as Fenton-like catalysts for highly efficient degradation of nitrophenols. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 548, 149248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odega, C.A.; Ayodele, O.O.; Ogutuga, S.O.; Anguruwa, G.T.; Adekunle, A.E.; Fakorede, C.O. Potential application and regeneration of bamboo biochar for wastewater treatment: A review. Adv. Bamboo Sci. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Zhou, L.; Fan, W. Schwertmannite Synthesis through Ferrous Ion Chemical Oxidation under Different H2O2 Supply Rates and Its Removal Efficiency for Arsenic from Contaminated Groundwater. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, F.; Wu, S. Migration of fluoranthene, phenanthrene, and pyrene in soil environment during the growth of Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 110, 104535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Zhou, L.; Hou, Q.; Wang, W.; Tian, Y.; Qin, J.; Bi, W.; Liu, F. Enhanced removal of As(III) and Cd(II) from wastewater by alkali-modified Schwertmannite@Biochar. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boily, J.-F.; Gassman, P.L.; Peretyazhko, T.; Szanyi, J.; Zachara, J.M. FTIR Spectral Components of Schwertmannite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chen, K.; Yin, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhuang, Q.; Cao, Q.; Dang, Z.; Guo, C. Surface properties of schwertmannite with different sulfate contents and its effect on Cr(VI) adsorption. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2024, 373, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.; Wu, Y.; Dong, W. The Degradation of Oxytetracycline with low concentration of persulfate sodium motivated by copper sulphate under simulated solar light. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 393, 122782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Ferronato, C.; Salvador, A.; Yang, X.; Chovelon, J.-M. Degradation of ciprofloxacin and sulfamethoxazole by ferrous-activated persulfate: Implications for remediation of groundwater contaminated by antibiotics. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 472, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, S.; Li, N.; Chen, G.; Hou, L. Applications of vacancy defect engineering in persulfate activation: Performance and internal mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 449, 130971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Lai, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Xu, F.; Nie, J. Metal-carbon hybrid materials induced persulfate activation: Application, mechanism, and tunable reaction pathways. Water Res. 2023, 234, 119808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, T.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, M.; Ge, L.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Application of carbon aerogel-based materials in persulfate activation for water treatment: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 384, 135518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).