3.1. Physiological Evaluations of Seeds After Drying

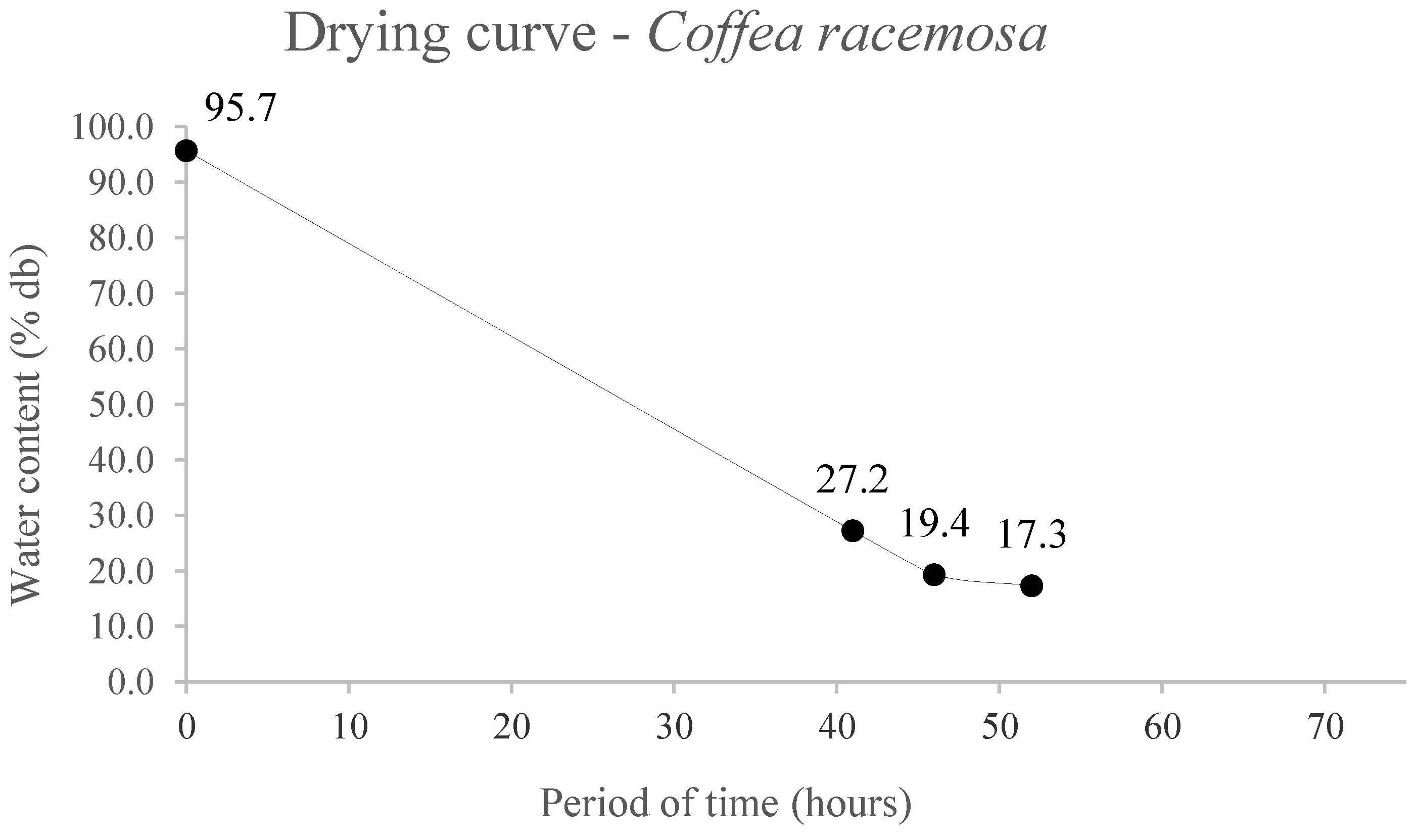

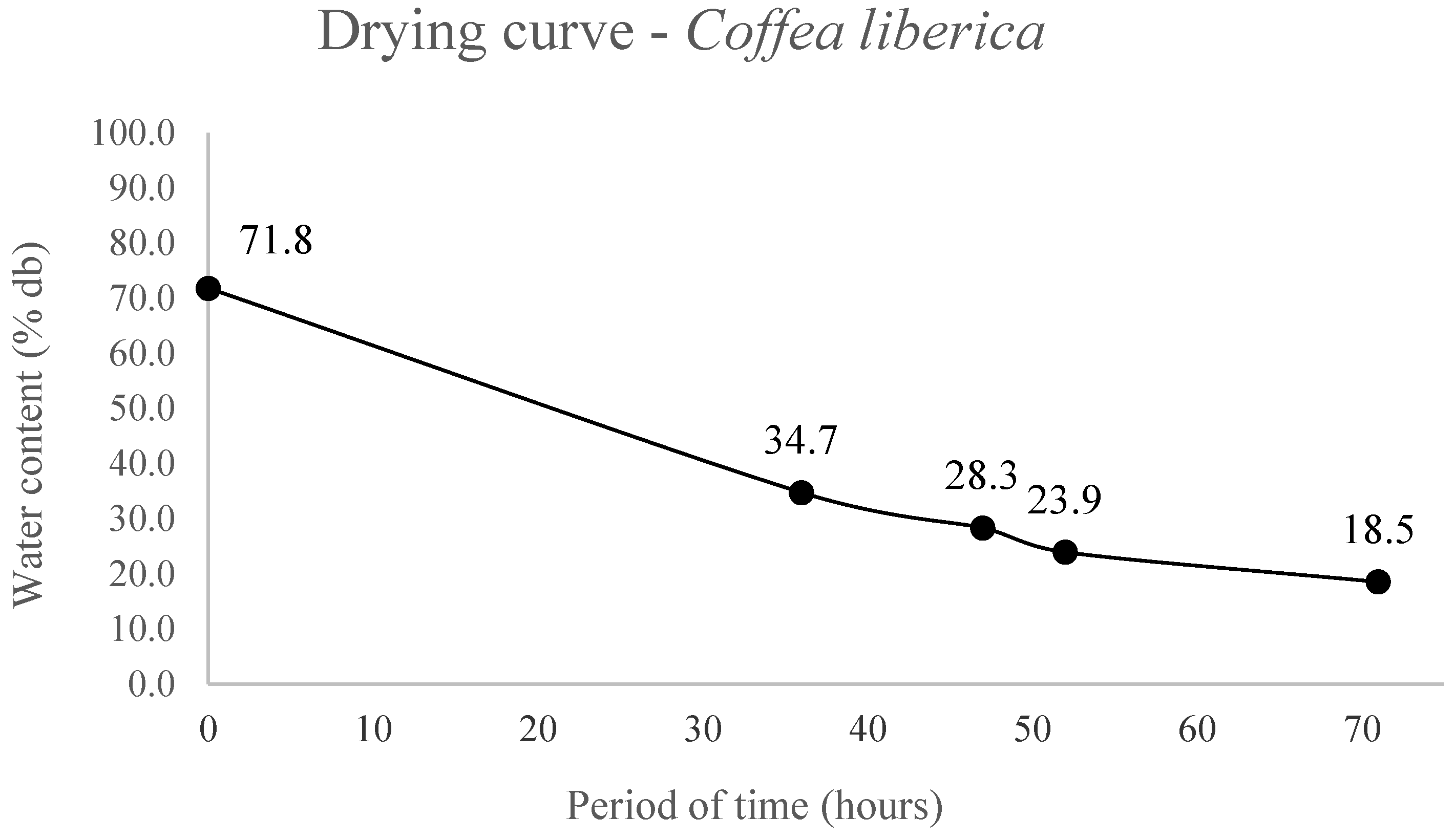

The seed drying curves are shown in

Figure 2, and the water content of

C. racemosa and

C. liberica var

dewevrei after drying in silica gel are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The

C. racemosa seeds, with initial moisture of 95.7%, remained 52 hours in gerbox containers with silica gel until reaching the lowest water content, 17.3%, which represents a drying rate of 0.65%.h

-1. A period of 71 hours was necessary for

C. liberica seeds, with initial moisture of 71.8%, to reach water content of 18.5%, a drying rate of 0.37%.h

-1 (

Figure 2).

According to Chevalier (1947),

C. racemosa seeds have a semi-globular or slightly elongated shape, with mean dimensions of 5-7 mm length × 5-6 mm width × 3-3.5 mm thickness. These values are lower than those obtained for

C. liberica var

dewevrei, whose seeds have a plano-convex shape, with approximate dimensions of 8-10 mm length × 5-7 mm width × 3-4 mm thickness. These characteristics may explain the different rates of water loss in the seeds of the two species. The rounded shape of

C. racemosa, with a larger exposed surface area, as well as its smaller size compared to

C. liberica (

Figure 1-A), favor the faster drying rate of

C. racemosa seeds.

Removal of water from the seeds for the purpose of cryopreservation is a key step, since the free water present in the cells can lead to the formation of ice crystals, which would rupture cell membranes. Therefore, water content should be ideal for cryopreservation, that is, not high enough to form ice crystals nor low enough to cause mechanical damage to the cells due to collapse of vacuoles and macromolecular structures (Wesley-Smith et al., 2014). According to Pammenter; Vertucci; Berjak (1993), the threshold of water loss that seeds or parts of seeds can tolerate without total loss of viability may coincide with the level of intracellular water that does not freeze, which varies among species.

The physiological quality of

C. racemosa seeds (

Table 1) and

C. liberica seeds (

Table 2) was assessed soon after harvest and after drying in silica gel. For

C. racemosa, root protrusion and seed viability 95% and 89%. There was no effect of water content on these characteristics. However, these high percentages were not maintained over seedling development for seeds dried to 25% or 18% moisture. At these water content levels (25% and 18%), lower percentages of normal seedlings and of expanded cotyledonary leaves, as well as a lower value for dry matter, were observed, compared to freshly-harvested seeds and those dried to 20%. Therefore, for this species, there was no loss of initial seed quality when seeds were dried to 20% moisture, since they exhibited 91.0% normal seedlings.

The water content of seeds before immersion in liquid nitrogen is one of the key factors in ensuring preservation of seed quality. Removing water from seeds through reduction in relative humidity (RH) using silica gel has proven to be a safe method for coffee cryopreservation. However, there is a threshold beyond which each species does not tolerate water loss (Figueiredo et al., 2017 and 2021; Coelho et al., 2017, 2018, and 2019). In the case of

C. racemosa, reduction in moisture to 18% was harmful to seed germination (

Table 1).

For

C. liberica, the effect of drying to water content from 20% to 35% was observed only for SV (

Table 2). The highest SV percentage occurred at intermediate water content, that is, 25% and 30%. SV declined compared to freshly-harvested seeds, and the lowest values were recorded at water content levels of 20% and 35%. This species is considered to have a higher degree of recalcitrance (Eira et al., 2005 and Dussert et al., 2001) than

C. racemosa, which makes water removal an even more delicate process.

The ability of plant tissues to survive below-zero (°C) temperatures depends on their tolerance not only to temperature, but also to desiccation. Many species have limits for these tolerance levels (Chin et al. 1989), which makes it necessary to know the degree of tolerance to drying along with the response of the tissues to exposure to below-zero temperatures.

3.2. Physiological Evaluations of Cryopreserved Seeds

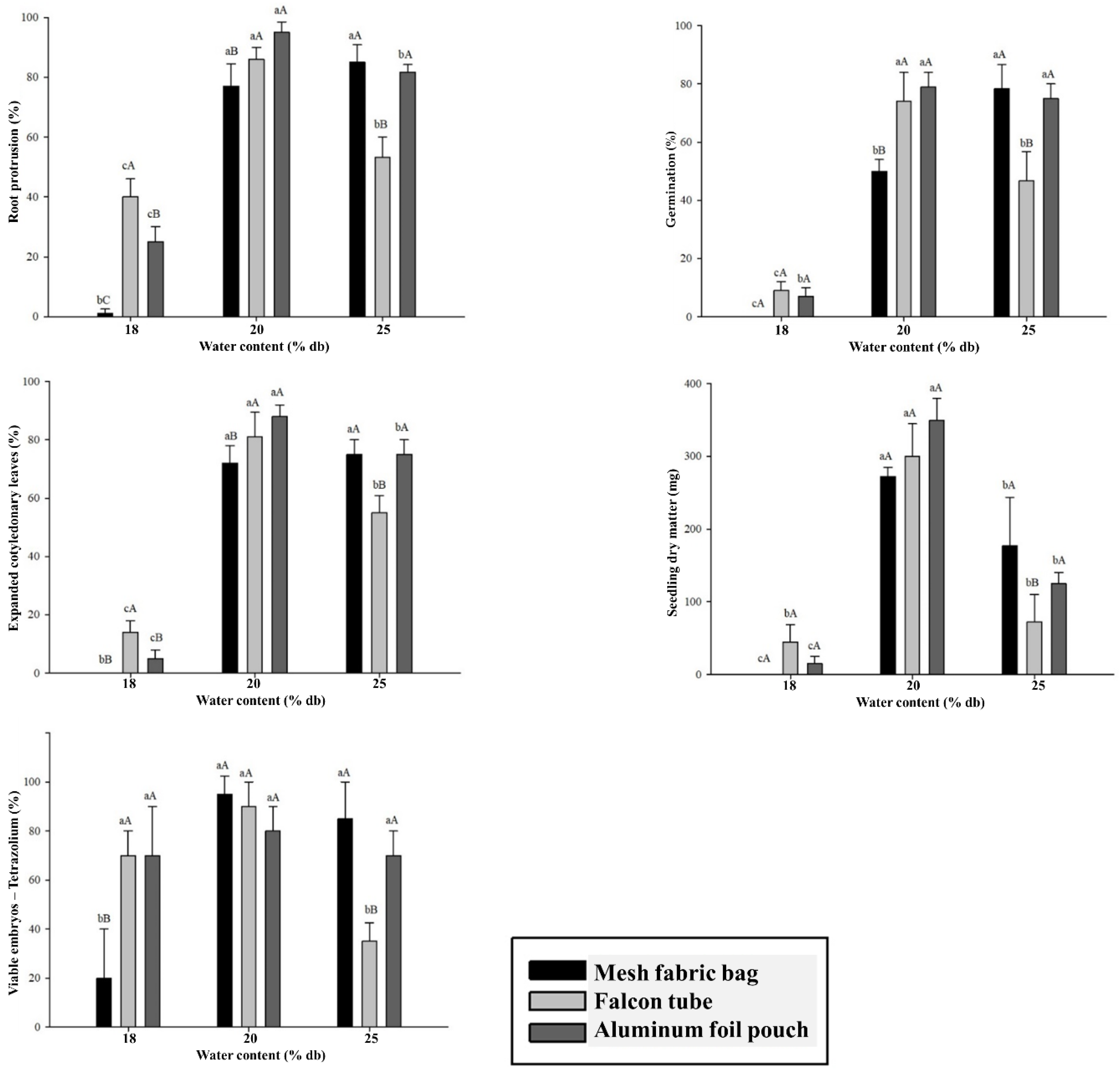

The results of the physiological quality indicators of

C. racemosa seeds after cryopreservation show a significant interaction between the water content and type of packaging factors (

Figure 3). Reducing the water content to 18% had a drastic effect on the seeds of this species, which exhibited low physiological performance, with a germination percentage below 20% (

Figure 3B). The low percentages of the variables RP, NS, SECL, and SDM of

C. racemosa seeds cryopreserved at 18% water content (

Figure 3) contrast with the better results for SV (

Figure 3D) observed in the tetrazolium test. This result can be attributed to the greater sensitivity of the endosperm to LN, as already observed by Dussert et al. (2001), Coelho et al. (2017, 2019), and Figueiredo et al. (2017 and 2021).

At 20% moisture, cryopreserved C. racemosa seeds showed greater survival and higher percentages in physiological evaluations. Under the same moisture at 20%, seeds stored in triple-layered aluminum foil sheets and Falcon tubes yielded better results compared to those stored in mesh fabric bags. An exception was observed in the tetrazolium test, where the type of packaging did not significantly affect seed viability.

In the cryopreservation process, rewarming is one of the critical factors for seed survival, because during this step, recrystallization or devitrification of the ice can cause fatal damage to cells. The adoption of fast rewarming can minimize recrystallization by reaching the melting point before significant crystallization growth occurs (Pan et al., 2023).

The water bath is traditionally used during the rewarming phase, and it is commercially available and widely used in plant experiments and practical applications. The basic principle of the water bath is to incubate biological samples by immersing them in a container with water at a fixed temperature. An electric heating device increases the water temperature in the container until it reaches the intended value. The use of a water bath has been reported as an effective method for warming biological samples after cryopreservation (Pan et al., 2023).

Mean values followed by the same uppercase letters comparing packaging within each moisture level and lowercase letters comparing moisture levels of the same packaging do not differ from each other by Tukey’s test at 5% probability. Error bars on averages indicate the standard deviation for measurements.

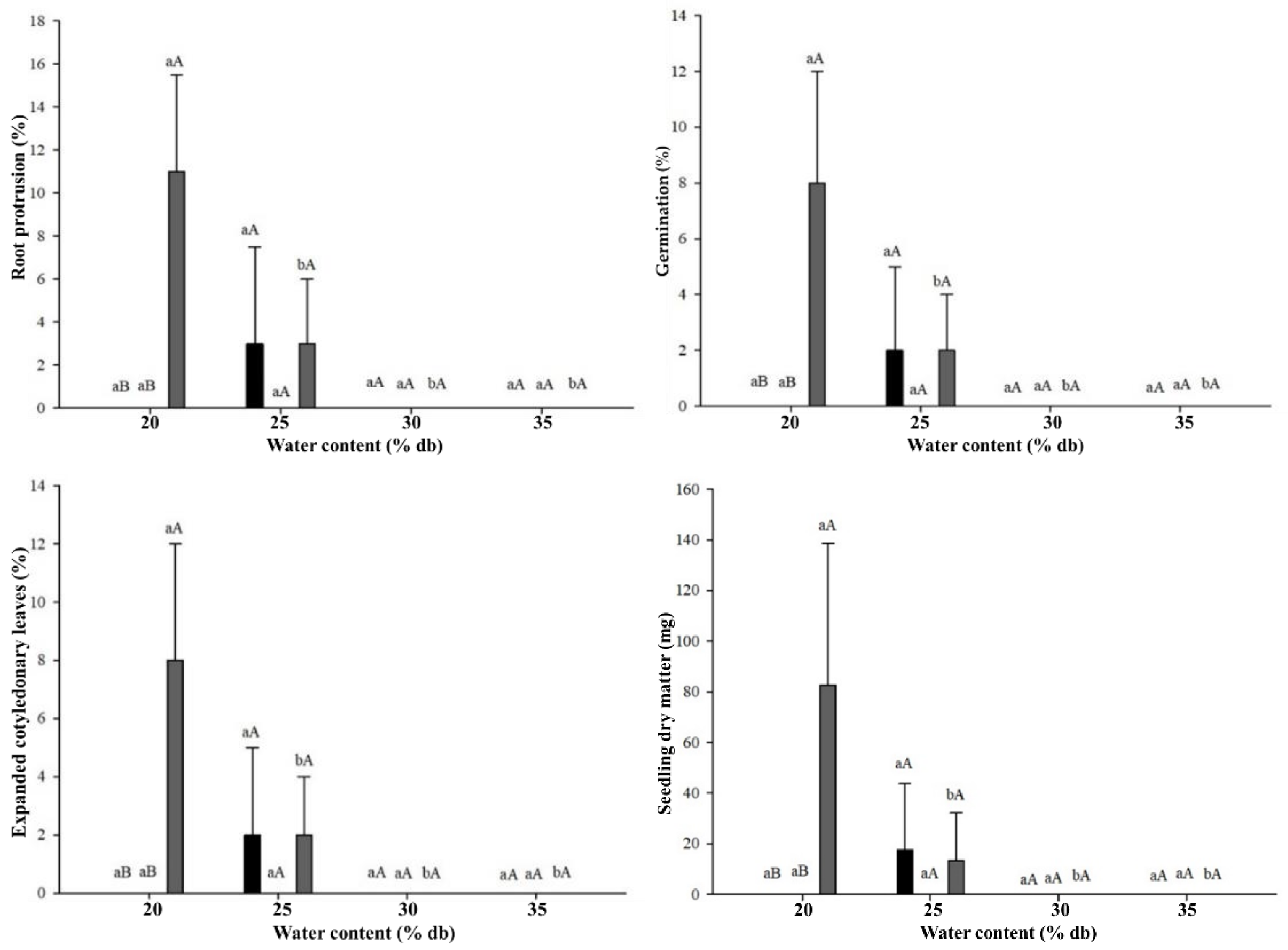

The cryopreservation treatments had strong negative impacts on the physiological quality of

C. liberica seeds (

Figure 4). After immersion in LN and rewarming, significant interaction of the factors was observed. The best performance was for the seeds with 20% water content in aluminum foil pouch packaging, which showed 10% root protrusion, 8% germination and of seedlings with expanded cotyledonary leaves, as well as 80 mg of seedling dry matter (

Figure 4-A, B, C, and E). At the water content of 25%, only 2% of the seeds packed in mesh fabric or aluminum foil pouches had some level of survival. The

C. liberica seeds with 30% and 35% water content did not survive cryopreservation (

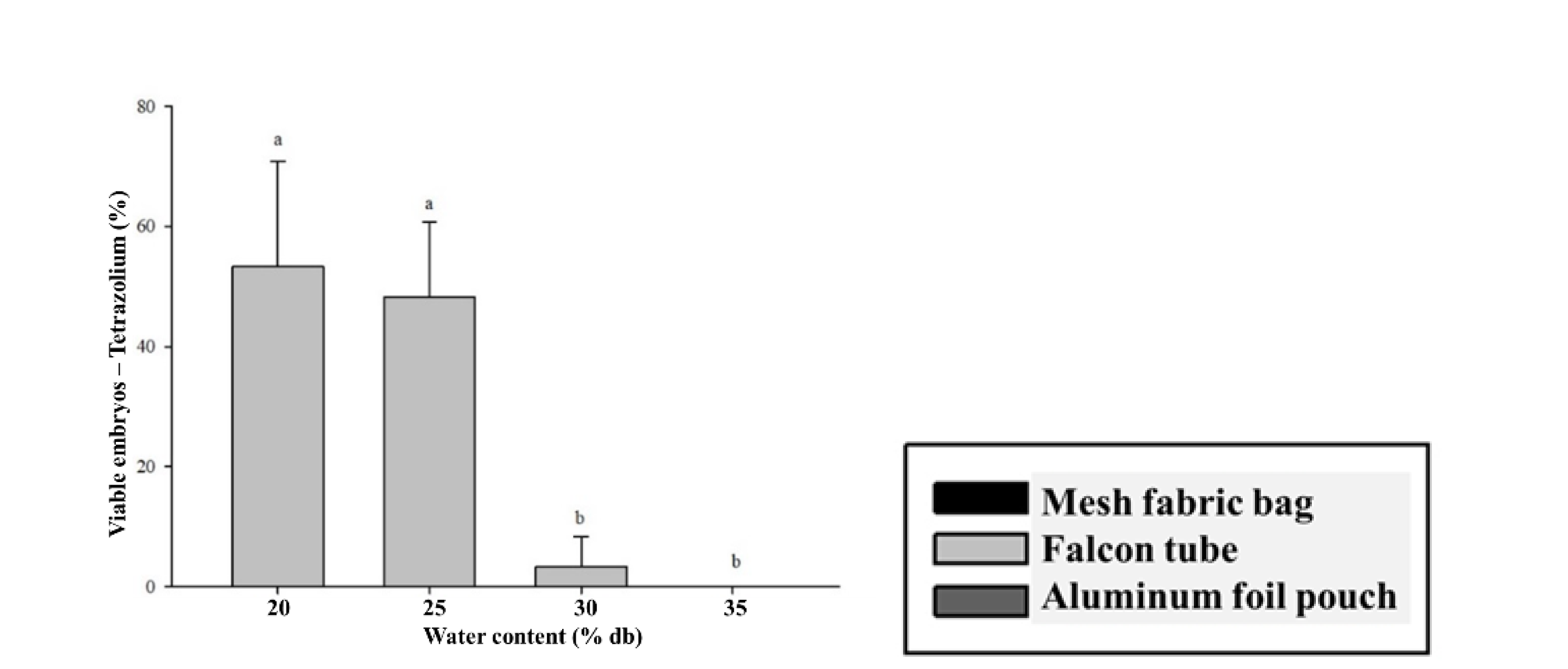

Figure 4). The tetrazolium test showed no interaction between the types of packaging; however, there was a significant difference between moisture levels. Seeds with 20% and 25% moisture content exhibited higher viability percentages, with 53% and 48%, respectively (

Figure 4D).

The best result for cryopreservation of C. liberica seeds dried in silica gel to 20% moisture and in aluminum foil pouch packaging was the protocol in which the seeds still survived. Although these results represent progress compared to other studies in which C. liberica seeds did not survive (Dussert et al., 2001), this value is still low compared to those achieved with other species, such as C. arabica and C. racemosa.

There is a wide variety of packages that can be used to store samples during cryopreservation. To package whole seeds, Tetra PakTM pouches and plastic containers of various sizes are generally used, or even jars with screw lids, whose sizes vary according to the sizes of seeds and samples. Although studies related to the effect of packages on cryopreservation of coffee seeds are rare, our results show that seed viability can be affected by the type of packaging used for preserving seed quality in LN.

Mean values followed by the same uppercase letters comparing packaging within each moisture level and lowercase letters comparing moisture levels of the same packaging do not differ from each other by Tukey’s test at 5% probability. Error bars on averages indicate the standard deviation for measurements.

Analysis of physiological quality for the two species in our study made it clear that C. racemosa has greater tolerance to cryopreservation than C. liberica var. dewevrei does. This result corroborates results obtained by Eira et al. (2005) who studied coffee seed physiology and observed that the degree of tolerance to dehydration varies among Coffea species, with C. racemosa being the most tolerant species, in contrast with C. liberica, which is the most sensitive. The authors also observed that there was no difference in tolerance to desiccation and to low temperature among different cultivars of C. arabica.

The differences among species of the Coffea genus can be attributed to both phylogenetic relationships and the habitat of origin of the species and/or the duration of the fruit development and maturation cycles (Eira et al., 2005). According to the authors, species from drier regions, such as C. racemosa, C. arabica, C. canephora, and C. congensis, have a higher degree of tolerance to desiccation than C. liberica var. liberica or var. dewevrei seeds, which are native to wetter regions. Regarding the fruit development and maturation period, C. racemosa, the species most tolerant to desiccation, requires only 90 days, whereas C. liberica var. dewevrei, the least tolerant species, reaches maturity only at 360 days (Carvalho et al., 1991).

Dussert et al. (2001) studied the response of Coffea species to cryopreservation with variation in the cooling rate of the seeds, and they differentiated three groups of species according to post-freezing survival. The first group consisted of C. brevipes, C. liberica, C. stenophylla, and C. canephora, whose seeds did not germinate after immersion in LN. In C. eugenioides and C. arabica, constituting the second group, survival was very low after rapid cooling and only moderate when cooling was performed more slowly. The third group consists of the species C. pseudozanguebariae, C. racemosa, and C. sessiliflora, which are characterized by high seed survival rates after both types of cooling (Dussert et al., 2001).

C. pseudozanguebariae and C. racemosa, according to Davis et al. (2006), originate from seasonally dry forests, which may explain the high survival rates achieved by Dussert et al. (2001) after cryopreservation of these species. The species C. sessiliflora has its origin in humid forests (Davis et al., 2006); however, it was classified by Dussert et al. (2001) in the same group as other species originating from dry areas, with high tolerance to cryopreservation.

Despite the high sensitivity of C. libérica seeds, the zygotic embryos extracted from ripe fruit show tolerance to cryopreservation (Dussert et al., 2001; Normah & Vengadasalam, 1992; and Hor et al., 1993). In the present study, use of the tetrazolium test also showed higher survival rates of embryos extracted from seeds after immersion in LN. This result can be attributed to the greater sensitivity of the endosperms compared to the embryos, which was also observed in other studies (Coelho et al., 2017, 2019, Figueiredo et al., 2021). The search for cryopreservation protocols for whole seeds is of great interest, considering that it is a simpler and more economical method. It also requires less time to obtain seedlings and, after that, plantlets appropriate for planting (Vilela et al., 2022).

Several protocols have been tested in recent years aiming at cryopreservation of coffee seeds. For the C. arabica L. species, some authors achieved success in the technique, with high germination percentages after immersion of the seeds with 20% water content (db) in LN (Coelho et al., 2017; Figueiredo et al., 2017 e 2021). For C. canephora, Coelho et al. (2018 and 2019) studied different cryopreservation methodologies, achieving a 43% survival rate of seeds dried to 25% db using silica gel and then directly immersed in LN. In the present study, C. racemosa, considered one of the species most tolerant to desiccation and to ultra-low temperatures within the genus, also showed 79% of normal seedlings, a high survival rate for seeds dried to 20% db and packed in an aluminum foil pouch before direct immersion in LN. According to Dussert et al. (2001), 52% of the C. racemosa seeds previously immersed in LN developed into normal seedlings after desiccation to 0.28 g H2O per g (dw). When water content was reduced to 0.20 g H2O per g (dw), there was only 12% germination, and no seedlings were produced at lower water content (Dussert et al., 2001).

For C. liberica, which is considered a species with more recalcitrant seeds (Dussert et al., 2001; Eira et al., 2005), only 8% of the seeds germinated after the technique in the present study, and further investigations are necessary to achieve better results. Normah and Vengadasalam (1992) studied the cryopreservation of this species after drying seeds to 16.7% water content (wb) and direct immersion in LN, achieving a 53% survival rate. They also observed that coffee seeds with the endocarp survived better than those without the endocarp.

For both species studied, drying seeds to 20% water content, followed by direct immersion in LN in aluminum foil pouches, was the best protocol among those studied, resulting in a 79.0% survival rate for C. racemosa and 8% for C. liberica.

3.3. Isoenzyme Profiles in Cryopreserved Seeds

From the results observed in the physiological evaluations of cryopreserved seeds, (

Figure 3), all the protocols analyzed for

C. racemosa resulted in viable seeds, and therefore, isoenzyme analyses were carried out for all of them (

Figure 5). For

C. liberica, these analyses were restricted to seeds with 20% and 25% water content that exhibited some survival (

Figure 4 and

Figure 6).

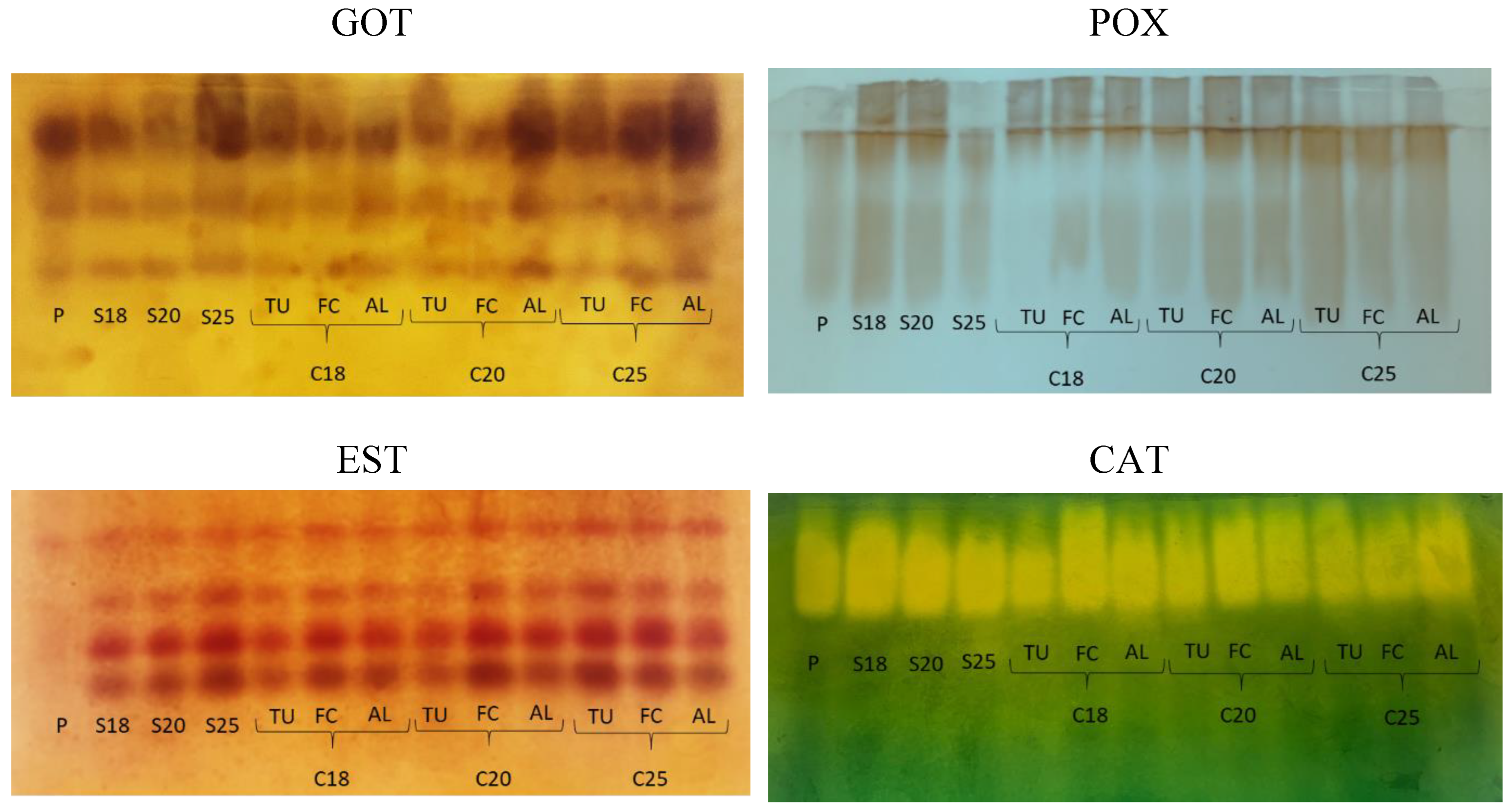

In

C. racemosa, GOT exhibited three well-defined isoforms, with variations in the intensity of the bands of the different treatments (

Figure 5). Glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT) is an important enzyme for germination and it is present throughout the plant development cycle. It is involved in transamination during removal of N from amino acids and in the formation of alpha-keto acid groups for the citric acid cycle and gluconeogenesis (Goodman and Stuber, 1983).

Seeds dried to 25% water content had a GOT profile similar to that observed in freshly-harvested seeds with 95.7% water content. In contrast, the intensity of the bands of this enzyme decreased when the seed water content was reduced to 20% and 18% water content (

Figure 5). Freezing the seeds in LN followed by warming for two minutes in a water bath did not change GOT activity in seeds with 25% water content stored in Falcon tubes and in three folded sheets of aluminum foil, and it led to an increase in GOT activity in seeds at 20% water content in three folded sheets of aluminum foil (

Figure 5). Seeds with 18% water content that had lower NS, SECL, and SDM compared to freshly-harvested seeds and those with 20% water content (

Table 1) did not exhibit a change in the GOT profile after cryopreservation, regardless of the package used. Thus, GOT activity does not related with the physiological quality of the cryopreserved seeds, which was high for seeds with 20% water content packaged in mesh or Falcon tubes and placed under the cryopreservation protocols. These protocols showed the same patterns observed for GOT in seeds with 18% water content after cryopreservation. The differences observed in the gel seem to be related to the higher water content of the freshly-harvested seeds and those with 25% water content, whether cryopreserved or not, and related to the manner of packaging the seeds, where aluminum foil packaging seems to favor GOT activity in seeds with 20% water content.

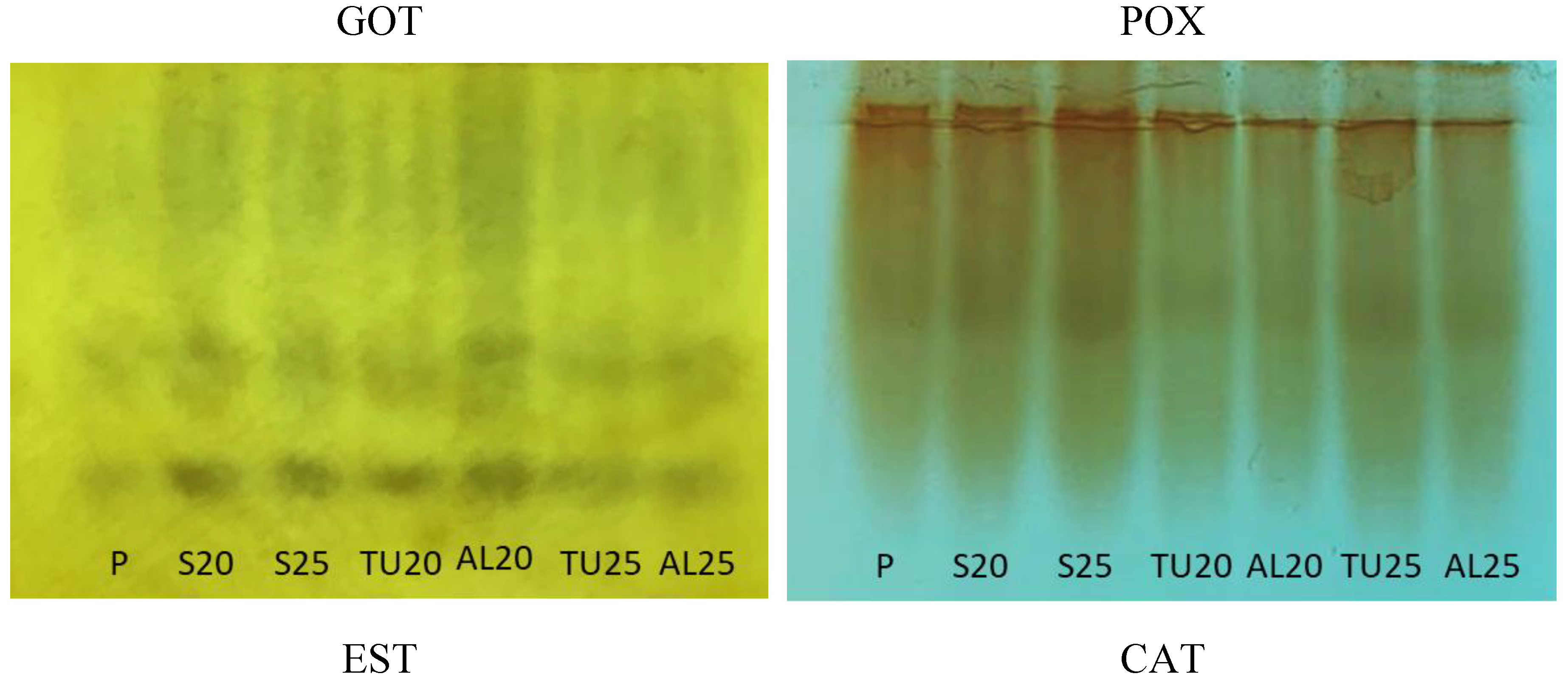

Unlike

C. racemosa, in the GOT profile obtained for the

C. liberica seeds, only two isoforms appeared in the polyacrylamide gel (

Figure 6A). Whereas in

C. racemosa the GOT was more active in the seeds with higher moisture levels, in

C. liberica, freshly-harvested seeds with 72% water content (

Table 1) had the lowest activity of this isoenzyme in their profile, followed by those cryopreserved with 25% water content. Seeds dried to 20% and 25% water content, just as those cryopreserved with 20% water content, had similar GOT profiles, with more active. It is important to emphasize that cryopreservation of

C. liberica resulted in viable in the tetrazolium test, conducted with embryos, at over 50% viability, but they had very low germination and vigor indices (

Figure 4). Also, for this species, GOT was not related with seed survival.

Peroxidases are enzymes that also are present throughout the plant life cycle. They belong to a large multigene family with a large number of isoforms. With two possible catalytic cycles, the peroxidative and the hydroxylating, peroxidases can generate free radicals, such as reactive oxygen species, and be involved in polymerization of cell wall compounds (Passardi et al., 2005). The POX also catalyze cross-linking between phenolic groups (tyrosine, phenylalanine, ferulic acid) in cell wall proteins, pectins, and other wall polymers (Passardi et al., 2005).

C. racemosa seeds dried to 25% water content showed the same pattern as freshly-harvested seeds. An increase in POX expression was observed when the seeds were dried to 18% and 20%. After cryopreservation, this pattern was maintained only in the seeds with 20% water content stored in Falcon tubes and in the three folded sheets of aluminum foil. In contrast, seeds with 18% water content that were cryopreserved showed reduction in POX expression, which was also observed for seeds with 20% water content cryopreserved in mesh packaging (

Figure 5).

The drying process is known to increase stress in seeds, and excessive amounts of ROS cause cell damage by oxidation of biomolecules such as lipids and proteins (Sahu et al., 2017). In addition, Passardi et al. (2005) indicate that physical stresses can induce expression of POX to trigger tissue repair mechanisms. Damage caused by LN to drier

C. racemosa seeds, those with 18% and 20% water content, especially for those kept in the mesh fabric packaging and that came into direct contact with the nitrogen, seems to have had a negative impact on POX activity, especially in relation to its cell-wall related function. This is shown by a drastic reduction in germination of these cryopreserved seeds, even when their embryos survive (

Figure 3).

For C. liberica, there was reduction in POX activity after cryopreservation of the seeds dried to 25% and 20% water content and stored either in mesh fabric or aluminum foil packaging. It should be noted that seeds with 20% water content in the mesh packaging showed low survival in the germination test, however, the percentage of viable seeds measured in the tetrazolium test, was the same as the percentage observed for the seeds with 25% water content.

Dussert et al. (2001) divided coffee species into groups according to their survival after cryopreservation. In that division, C. liberica and C. canephora seeds did not germinate after immersion in LN. In another group, C. racemosa responded with high seed survival after immersion in LN. It is noteworthy that Coelho et al. (2018) also found no correlation between POX and protocols related to cooling rates in the cryopreservation process of C. canephora seeds. That may indicate that more recalcitrant seeds, such as those of C. liberica, the regulatory mechanism of POX expression does not follow the same pattern observed in seeds more tolerant to cryopreservation.

In

C. racemosa, the freshly-harvested seeds showed virtually no EST expression. EST activation is observed along with the seed drying process and its maintenance after cryopreservation, without differences in the profiles according to water content or different types of packaging. An exception can be seen for seeds cryopreserved at 18% and 20% water content and stored in mesh packaging (

Figure 5). Esterase hydrolyzes esters and metabolizes lipids such as membrane phospholipids. Cryopreservation stress, just as seen for POX, resulted in lower band intensity in the treatments mentioned above.

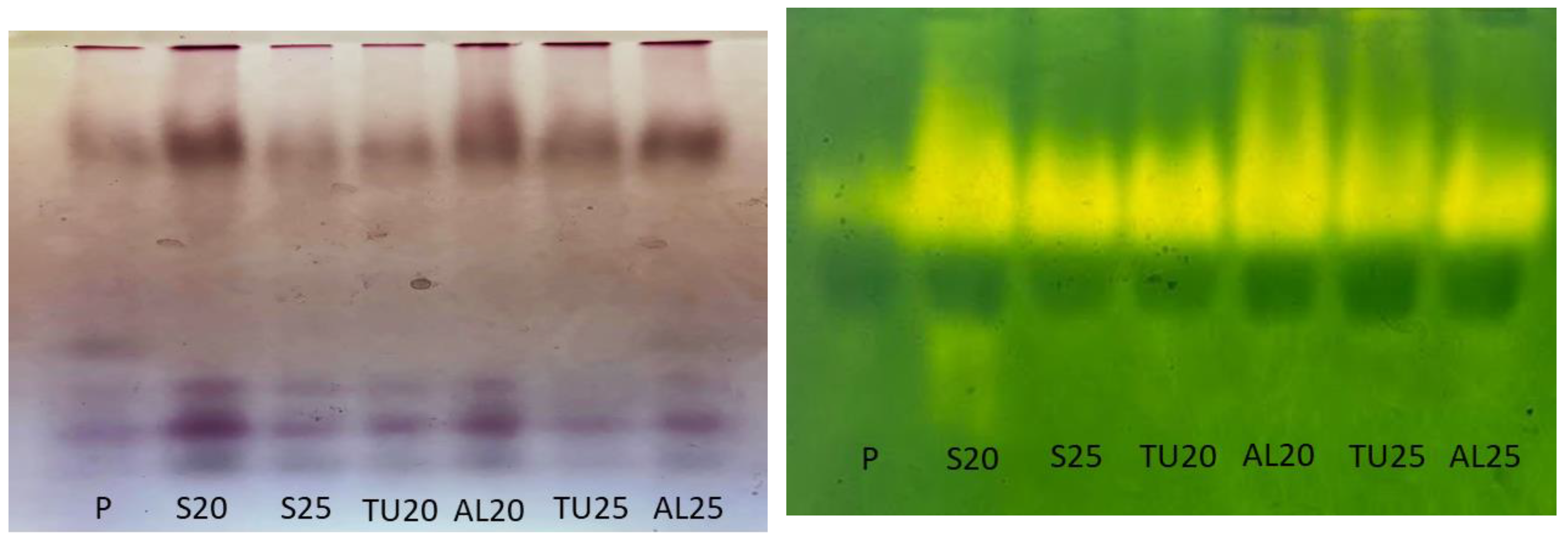

For

C. liberica, the EST pattern for freshly-harvested seeds was different: five isoforms were expressed, compared to four isoforms in the other treatments. After drying, the seeds with 20% water content showed greater esterase activity than those with 25% water content. Cryopreservation in the aluminum foil packaging of seeds with 20% and 25% water content resulted in seeds with greater EST activity (

Figure 6). Coelho et al. (2019) also observed that in

C. canephora seeds, drying seeds from 22% to 17% wb favors increased expression of this isoenzyme. The authors also found that when the seeds were dried slowly to 22% water content (wb) using a NaCl solution and then cryopreserved, they also showed low expression of this enzyme.

Catalase, found in the peroxisomes and mitochondria, is part of the efficient antioxidant enzyme machinery in the cells, and it is involved in protection against damage caused by oxidative stress by breaking down H

2O

2 into O

2 and H

2O (Das & Roychoudhury, 2014, Gill & Tuteja, 2010; Sahu, 2017). CAT was already active in the freshly harvested

C. racemosa seeds and remained so after drying and cryopreservation. A decline in catalase activity was observed only for the protocol in which seeds with 18% water content stored in mesh packaging were cryopreserved (

Figure 5).

Freshly-harvested

C. liberica seeds showed low CAT activity, which increased with the drying process. Seeds with 20% water content showed greater intensity of CAT expression, indicating the response of this enzyme to an increased demand likely created by stress from greater water removal from the seeds (

Figure 6). Although the cryopreserved

C. liberica seeds low survival (

Figure 4), CAT remained active after the cryopreservation of seeds with 20% and 25% water content stored in both mesh and aluminum foil packaging.

It is known that ROS also have a signaling effect in response to abiotic stresses, as they are necessary for cell homeostasis based on a delicate balance between production and elimination of these reactive species (Das & Roychoudhury, 2014; Sahu et al., 2017). It is noteworthy that CAT is activated in

C. liberica only when water is removed from the seeds, indicating that cell signaling for protection against oxidative stress only occurs at that time (

Figure 6). This is different from the response observed in

C. racemosa, where high CAT activity is already observed in freshly-harvested seeds with 95.7% water content (

Figure 5). In

C. canephora, the species studied by Coelho et al. (2018), CAT was a good marker for monitoring the vigor of cryopreserved seeds, and those with higher quality showed greater band intensity for these enzymes.

In general, for

C. racemosa, the isoenzymes GOT, POX, and EST showed comparatively lower activity when seeds with 20% or 18% water content were stored in mesh fabric (

Figure 5). In addition to the oxidative stress damage caused by the drying process, this type of packaging led to increased stress from direct contact of LN with the endosperm. The opposite was observed for the aluminum foil packaging, which proved to be more suitable for seed storage, also in regard to physiological quality. For

C. liberica, further studies are necessary to define a cryopreservation protocol that will allow recovery of seeds with higher germination and vigor rates.

Studies on more recalcitrant seeds are challenging, requiring, at the same time, specific and appropriate methods, speed, and precision, characteristics that cannot always be ensured simultaneously. Thus, results such as those presented in this study for C. liberica are very important, in spite of the low survival rate of these seeds after cryopreservation. Various factors affect the quality of cryopreserved seeds, and they may interact, as was shown in this study and in numerous results already published. Factors such as the initial quality of the seeds, drying method, water content, seed preparation and protective treatment, cooling rate, and the rewarming method after removal from the cryotank are essential to ensure preservation.