Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and reagents

2.2. Experiments

2.2.1. LOM experiments

2.2.2. Abiotic experiments

2.3. Supernatant analysis

2.3.1. LOM experiments

2.3.2. Abiotic experiments

2.4. Mass balance

3. Results and discussions

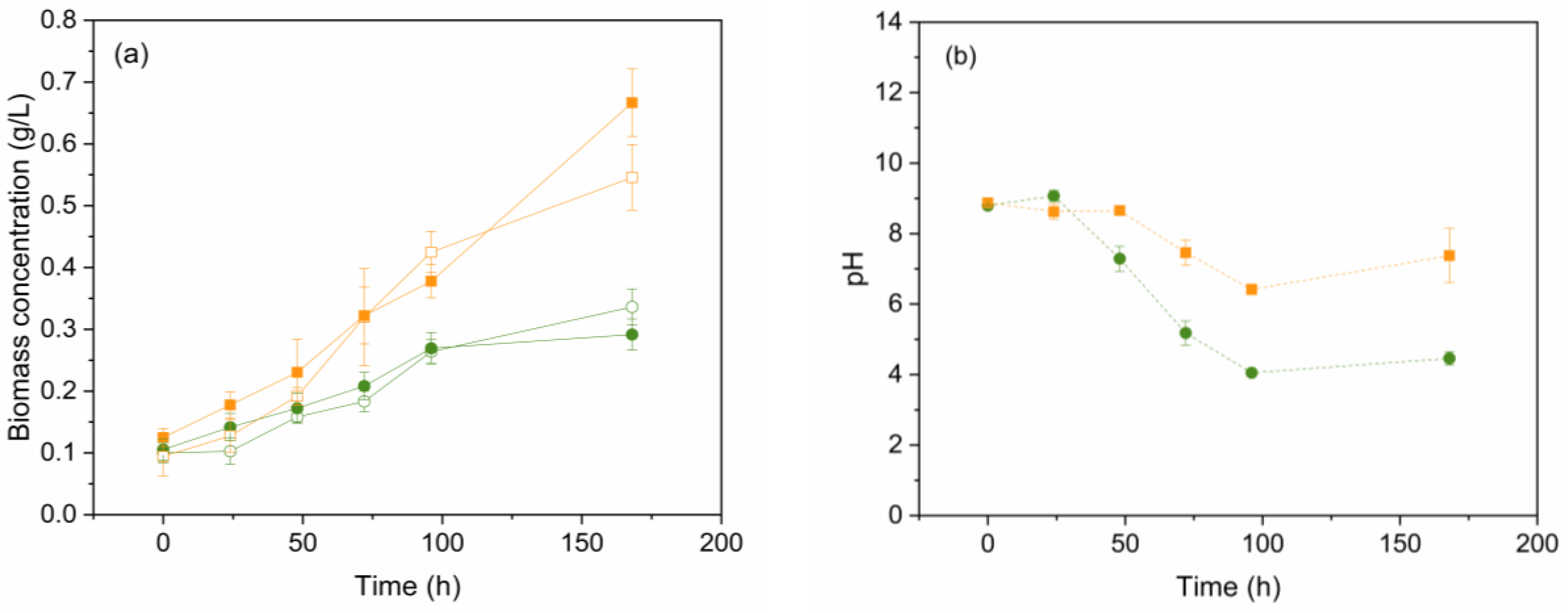

3.1. Microalgae growth in the presence of EDCs

3.2. Nutrient removal

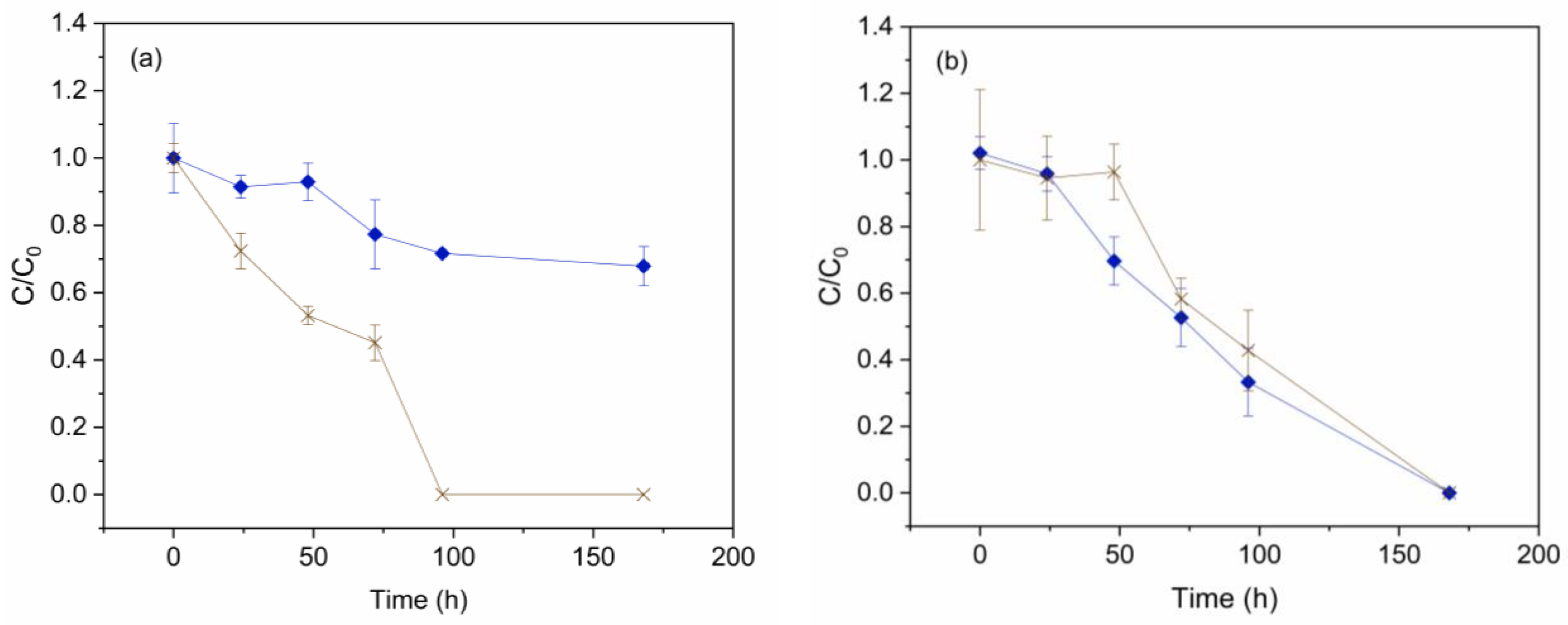

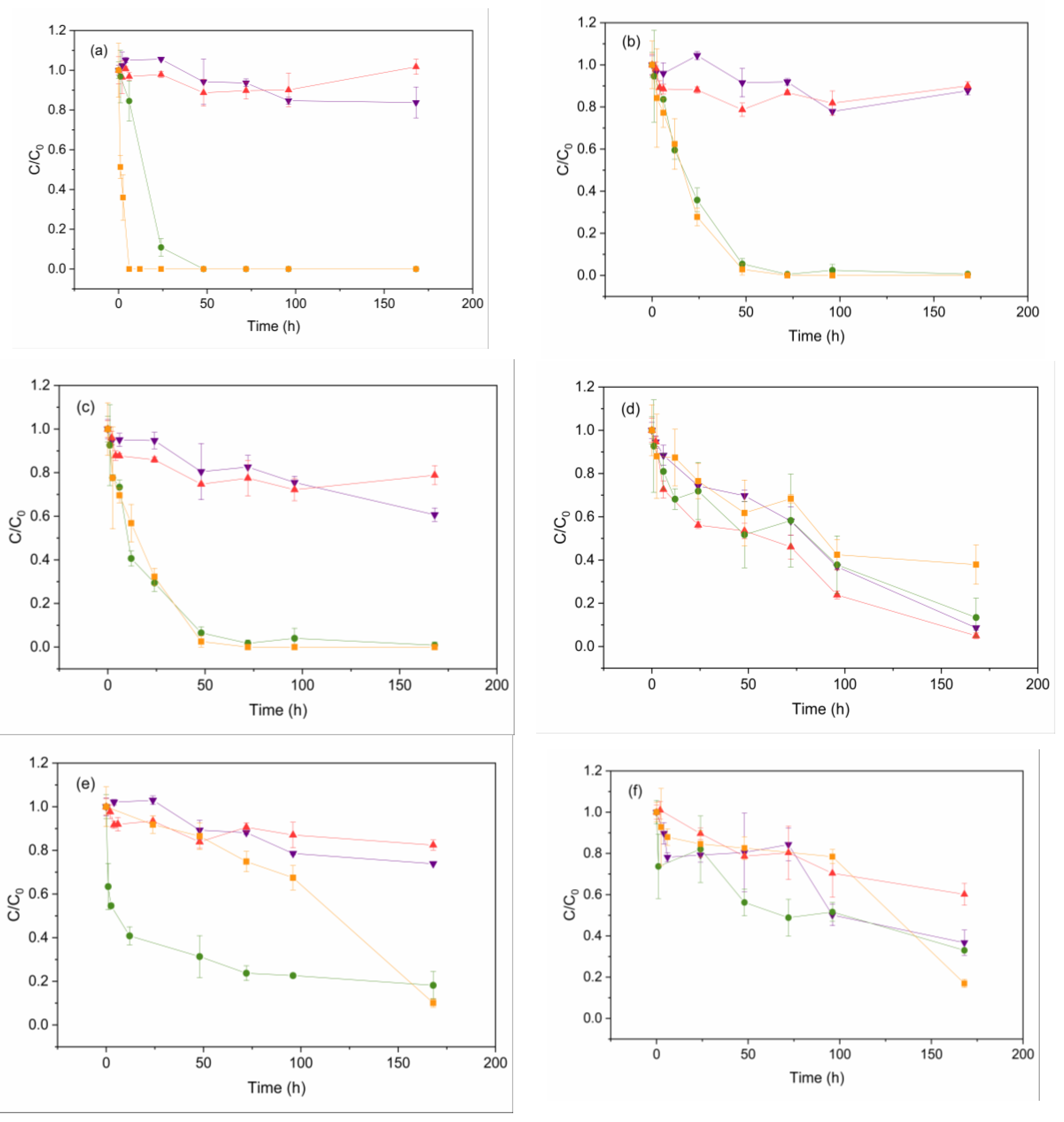

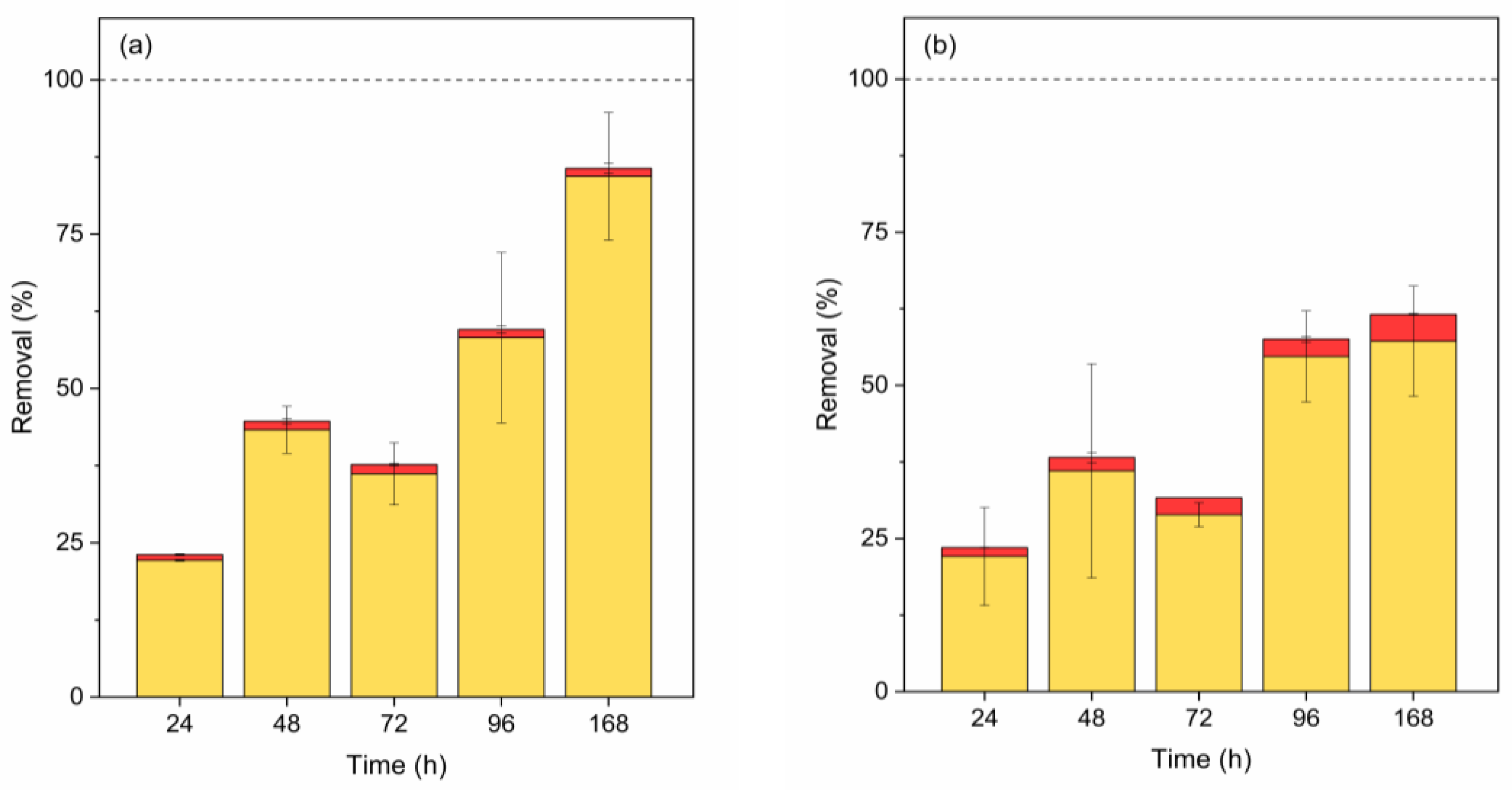

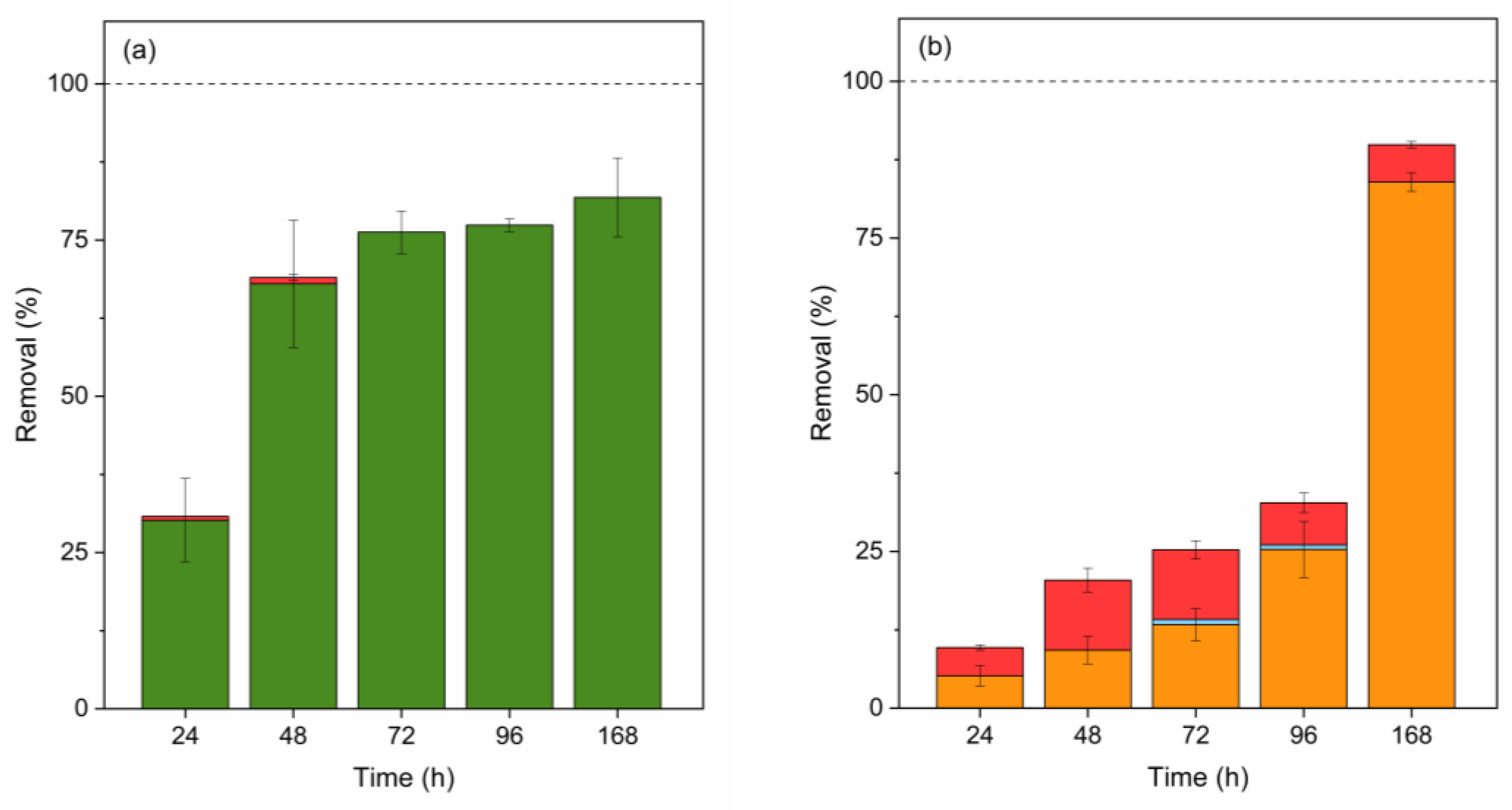

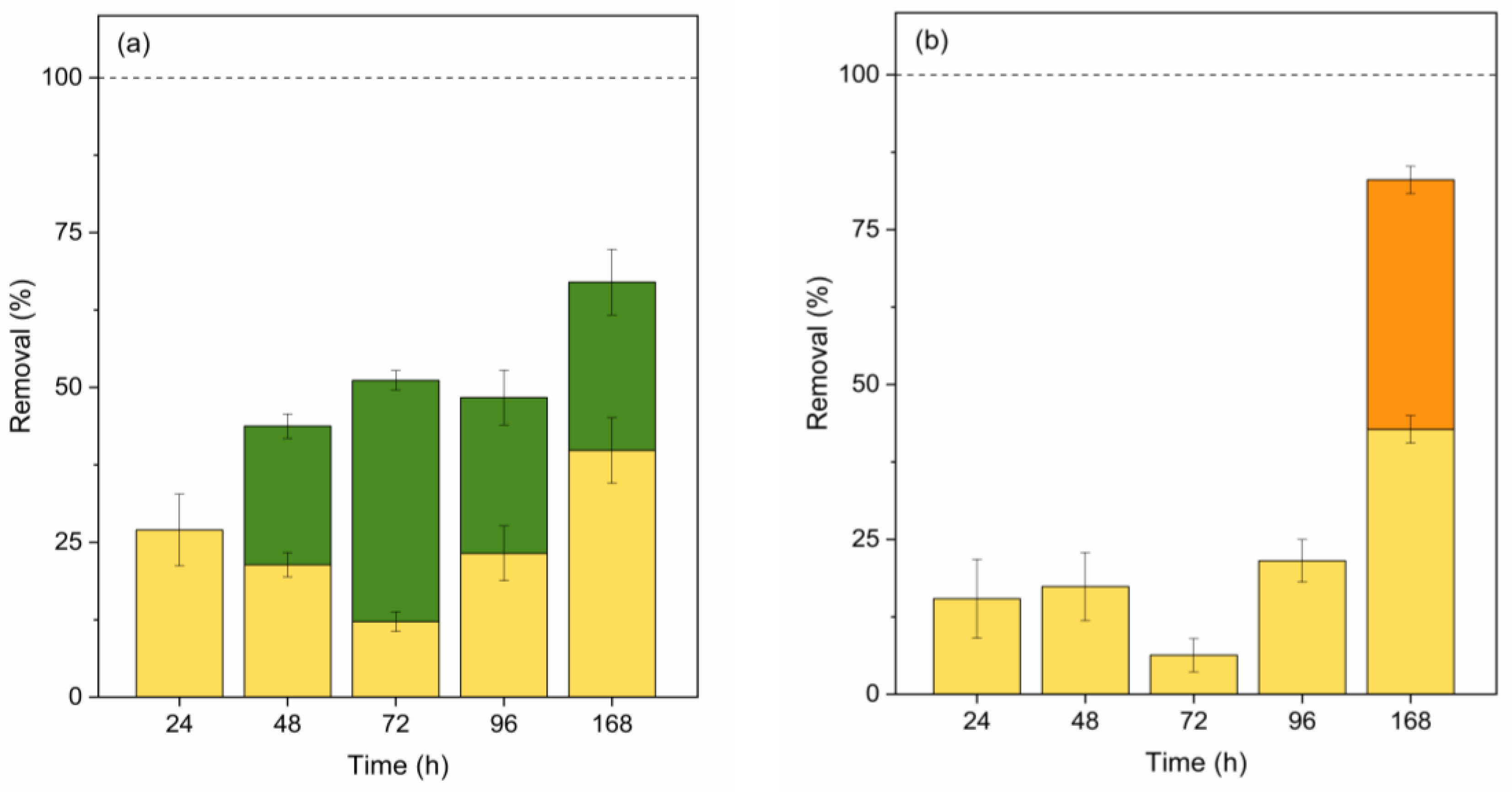

3.3. EDCs removal

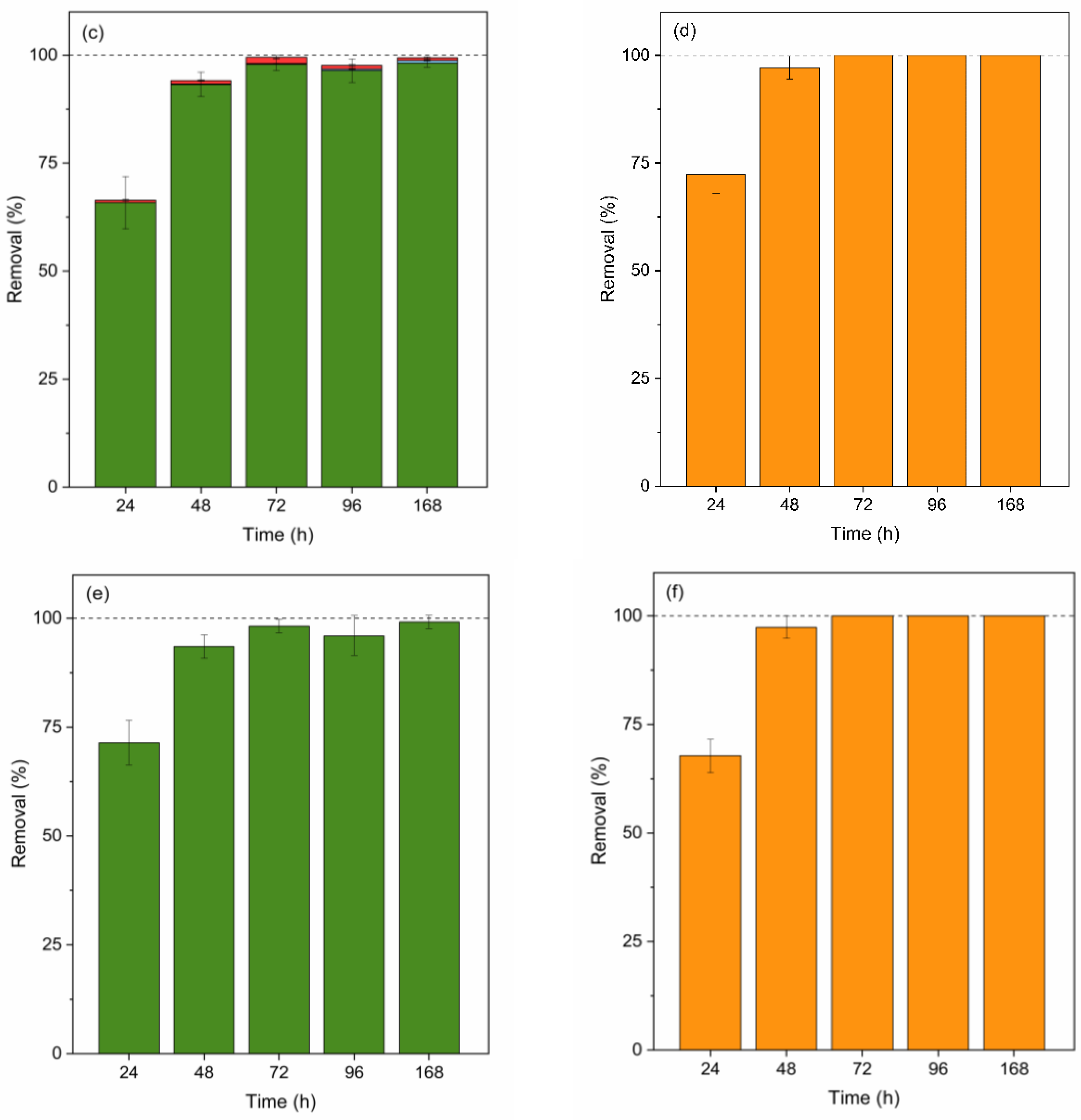

3.4. Mass balance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Xu, J. Progress in the Biological and Chemical Treatment Technologies for Emerging Contaminant Removal from Wastewater: A Critical Review. J Hazard Mater 2017, 323, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtuoso, S.; Raggi, C.; Maugliani, A.; Baldi, F.; Gentili, D.; Narciso, L. Toxicological Effects of Naturally Occurring Endocrine Disruptors on Various Human Health Targets: A Rapid Review. Toxics 2024, 12, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casals-Casas, C.; Desvergne, B. Endocrine Disruptors: From Endocrine to Metabolic Disruption. Annu Rev Physiol 2011, 73, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, K.; Jabłońska, E.; Ratajczak-Wrona, W. Immunomodulatory Effects of Synthetic Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals on the Development and Functions of Human Immune Cells. Environ Int 2019, 125, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolujoko, N.B.; Unuabonah, E.I.; Alfred, M.O.; Ogunlaja, A.; Ogunlaja, O.O.; Omorogie, M.O.; Olukanni, O.D. Toxicity and Removal of Parabens from Water: A Critical Review. Sci Total Environ 2021, 792, 148092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. hong; Li, J.; Xu, G.; Ma, L. dan; Li, J. jun; Li, J. song; Tang, L. Pollution Patterns and Underlying Relationships of Benzophenone-Type UV-Filters in Wastewater Treatment Plants and Their Receiving Surface Water. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2018, 152, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohore, O.E.; Songhe, Z. Endocrine Disrupting Effects of Bisphenol A Exposure and Recent Advances on Its Removal by Water Treatment Systems. A Review. Sci Afr 2019, 5, e00135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.S.; Sánchez, P.S.V.; Gil, S.A.A. Removal of Estrone in Water and Wastewater by Photocatalysis: A Systematic Review. Prod Limpia 2019, 14, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Shields, J.N.; Akemann, C.; Meyer, D.N.; Connell, M.; Baker, B.B.; Pitts, D.K.; Baker, T.R. The Phenotypic and Transcriptomic Effects of Developmental Exposure to Nanomolar Levels of Estrone and Bisphenol A in Zebrafish. Sci Total Environ 2021, 757, 143736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.; Ratajczak-Wrona, W.; Górska, M.; Jabłońska, E. Parabens and Their Effects on the Endocrine System. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2018, 474, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeppe, E.S.; Ferguson, K.K.; Colacino, J.A.; Meeker, J.D. Relationship between Urinary Triclosan and Paraben Concentrations and Serum Thyroid Measures in NHANES 2007-2008. Sci Total Environ 2013, 445–446, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadkhaniha, R.; Mansouri, M.; Yunesian, M.; Omidfar, K.; Jeddi, M.Z.; Larijani, B.; Mesdaghinia, A.; Rastkari, N. Association of Urinary Bisphenol a Concentration with Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Environ Health Sci Eng 2014, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trasande, L.; Attina, T.M.; Blustein, J. Association between Urinary Bisphenol A Concentration and Obesity Prevalence in Children and Adolescents. JAMA 2012, 308, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Fan, J.; Cai, S.; Fan, C.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, L. Associations of Urinary Levels of Phenols and Parabens with Osteoarthritis among US Adults in NHANES 2005–2014. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2020, 192, 110293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silori, R.; Kumar, M.; Madhab Mahapatra, D.; Biswas, P.; Prakash Vellanki, B.; Mahlknecht, J.; Mohammad Tauseef, S.; Barcelo, D. Prevalence of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in the Urban Wastewater Treatment Systems of Dehradun, India: Daunting Presence of Estrone. Environ Res 2023, 235, 116673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błedzka, D.; Gromadzińska, J.; Wasowicz, W. Parabens. From Environmental Studies to Human Health. Environ Int 2014, 67, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültekin, I.; Ince, N.H. Synthetic Endocrine Disruptors in the Environment and Water Remediation by Advanced Oxidation Processes. J Environ Manage 2007, 85, 816–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servos, M.R.; Bennie, D.T.; Burnison, B.K.; Jurkovic, A.; McInnis, R.; Neheli, T.; Schnell, A.; Seto, P.; Smyth, S.A.; Ternes, T.A. Distribution of Estrogens, 17β-Estradiol and Estrone, in Canadian Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Sci Total Environ 2005, 336, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Suthar, S. Occurrence, Seasonal Variation, Mass Loading and Fate of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in Sewage Treatment Plants in Cities of Upper Ganges Bank, India. J Water Process Eng 2021, 44, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, E.; Yamashita, N.; Taniyasu, S.; Lam, J.; Lam, P.K.S.; Moon, H.B.; Jeong, Y.; Kannan, P.; Achyuthan, H.; Munuswamy, N.; et al. Bisphenol A and Other Bisphenol Analogues Including BPS and BPF in Surface Water Samples from Japan, China, Korea and India. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2015, 122, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Liao, C.; Song, G.J.; Ra, K.; Kannan, K.; Moon, H.B. Emission of Bisphenol Analogues Including Bisphenol A and Bisphenol F from Wastewater Treatment Plants in Korea. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, C.D.; Bayen, S.; Desrosiers, M.; Muñoz, G.; Sauvé, S.; Yargeau, V. An Introduction to the Sources, Fate, Occurrence and Effects of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals Released into the Environment. Environ Res 2022, 207, 112658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Sharabati, M.; Abokwiek, R.; Al-Othman, A.; Tawalbeh, M.; Karaman, C.; Orooji, Y.; Karimi, F. Biodegradable Polymers and Their Nano-Composites for the Removal of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) from Wastewater: A Review. Environ Res 2021, 202, 111694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, D.; Arif, A.; Blair, D.; Dionne, J.; Filion, Y.; Ouarda, Y.; Pazmino, A.G.; Pulicharla, R.; Rilstone, V.; Tiwari, B.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Current Technologies for Removal of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals from Wastewaters. Environ Res 2022, 207, 112196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.L.; Ralph, P.J. Microalgal Bioremediation of Emerging Contaminants - Opportunities and Challenges. Water Res 2019, 164, 114921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncel, S.S. Microalgae for a Macroenergy World. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2013, 26, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Choudhary, S.; Meena, A.; Poluri, K.M. Carbon Capture, Storage, and Usage with Microalgae: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2023, 21, 2085–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazirzadeh, A.; Jafarifard, K.; Ajdari, A.; Chisti, Y. Removal of Nitrate and Phosphate from Simulated Agricultural Runoff Water by Chlorella vulgaris. Sci Total Environ 2022, 802, 149988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabed, H.M.; Akter, S.; Yun, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, X. Biogas from Microalgae: Technologies, Challenges and Opportunities. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2020, 117, 109503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narindri Rara Winayu, B.; Chu, F.J.; Sutopo, C.C.Y.; Chu, H. Bioprospecting Photosynthetic Microorganisms for the Removal of Endocrine Disruptor Compounds. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 40, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.J.; Ying, G.G.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L.J.; Chen, Z.F.; Peng, F.Q. Simultaneous Removal of Inorganic and Organic Compounds in Wastewater by Freshwater Green Microalgae. Environ Sci Process Impacts 2014, 16, 2018–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Xiong, J.Q.; Ru, S.; Patil, S.M.; Kurade, M.B.; Govindwar, S.P.; Oh, S.E.; Jeon, B.H. Toxicity of Benzophenone-3 and Its Biodegradation in a Freshwater Microalga Scenedesmus Obliquus. J Hazard Mater 2020, 389, 122149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Wang, L.; Rousseau, D.P.L.; Lens, P.N.L. Removal of Estrone, 17α-Ethinylestradiol, and 17ß-Estradiol in Algae and Duckweed-Based Wastewater Treatment Systems. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2010, 17, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, M.K.; Kabra, A.N.; Choi, J.; Hwang, J.H.; Kim, J.R.; Abou-Shanab, R.A.I.; Oh, Y.K.; Jeon, B.H. Biodegradation of Bisphenol A by the Freshwater Microalgae Chlamydomonas mexicana and Chlorella vulgaris. Ecol Eng 2014, 73, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Heredia, J.C.; Sacramento-Rivero, J.C.; Ruiz-Marín, A.; Baz-Rodríguez, S.; Canedo-López, Y.; Narváez-García, A. Evaluation of Cell Growth, Nitrogen Removal and Lipid Production by Chlorella vulgaris to Different Conditions of Aireation in Two Types of Annular Photobioreactors. Rev Mex Ing Quim 2016, 15, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A.; Gupta, V. Methods for the Determination of Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantitation of the Analytical Methods. Chron Young Sci 2011, 2, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, I.T.K.; Sung, Y.Y.; Jusoh, M.; Wahid, M.E.A.; Nagappan, T. Chlorella vulgaris: A Perspective on Its Potential for Combining High Biomass with High Value Bioproducts. Appl Phycol 2020, 1, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Hong-ying, H.; Ke, G.; Jia, Y. Growth and Nutrient Removal Properties of a Freshwater Microalga Scenedesmus sp. LX1 under Different Kinds of Nitrogen Sources. Ecol Eng 2010, 36, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xu, W.; Luan, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, L.; Lin, L. Comparative Responses of Cell Growth and Related Extracellular Polymeric Substances in Tetraselmis sp. to Nonylphenol, Bisphenol A and 17α-Ethinylestradiol. Environ Pollut 2021, 274, 116605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; He, Y.; Song, L.; Ding, J.; Ren, S.; Lv, M.; Chen, L. Methylparaben Toxicity and Its Removal by Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris and Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Hazard Mater 2023, 454, 131528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.C.; Dennett, M.R.; Riley, C.B. Effect of Nitrogen-mediated Changes in Alkalinity on pH Control and CO2 Supply in Intensive Microalgal Cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng 1982, 24, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinod, R. Maraskolhe Carbon Sequestration Potential of Scenedesmus Species (Microalgae) under the Fresh Water Ecosystem. Afr J Agr Res 2012, 7, 2818–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakuei, N.; Amini, G.; Najafpour, G.D.; Jahanshahi, M.; Mohammadi, M. Optimal Cultivation of Scenedesmus sp. Microalgae in a Bubble Column Photobioreactor. Indian J Chem Technol 2015, 22, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makareviciene, Prof.Dr.V.; Andrulevičiūtė, V.; Skorupskaitė, V.; Kasperovičienė, J. Cultivation of Microalgae Chlorella sp. and Scenedesmus sp. as a Potentional Biofuel Feedstock. Environ Res Eng Manag 2011, 57, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Green, B.F.; Lundquist, T.; Mujeriego, R.; Hernández-Mariné, M.; Oswald, W.J. Long Term Diurnal Variations in Contaminant Removal in High Rate Ponds Treating Urban Wastewater. Bioresour Technol 2006, 97, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Hong-ying, H.; Ke, G.; Ying-xue, S. Effects of Different Nitrogen and Phosphorus Concentrations on the Growth, Nutrient Uptake, and Lipid Accumulation of a Freshwater Microalga Scenedesmus sp. Bioresour Technol 2010, 101, 5494–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, H.Y.; Su, Z.F. Biomass Production of a Scenedesmus sp. under Phosphorous-Starvation Cultivation Condition. Bioresour Technol 2012, 112, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, Y.; Hwang, S.J. Removal of Nitrogen and Phosphorus by Chlorella sorokiniana Cultured Heterotrophically in Ammonia and Nitrate. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 2013, 85, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dȩbowski, M.; Rusanowska, P.; Zieliński, M.; Dudek, M.; Romanowska-Duda, Z. Biomass Production and Nutrient Removal by Chlorella vulgaris from Anaerobic Digestion Effluents. Energies (Basel) 2018, 11, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; He, L.; Sun, X.; Li, X.; Li, M. The Transformation of Benzophenone-3 in Natural Waters and AOPs: The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Potential Environmental Risks of Products. J Hazard Mater 2022, 427, 127941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Guo, X.F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.S. The Natural Degradation of Benzophenone at Low Concentration in Aquatic Environments. Water Sci Technol 2015, 72, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abargues, M.R.; Ferrer, J.; Bouzas, A.; Seco, A. Removal and Fate of Endocrine Disruptors Chemicals under Lab-Scale Postreatment Stage. Removal Assessment Using Light, Oxygen and Microalgae. Bioresour Technol 2013, 149, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Chen, G.Z.; Tam, N.F.Y.; Luan, T.G.; Shin, P.K.S.; Cheung, S.G.; Liu, Y. Toxicity of Bisphenol A and Its Bioaccumulation and Removal by a Marine Microalga Stephanodiscus hantzschii. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2009, 72, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenorio, R.; Fedders, A.C.; Strathmann, T.J.; Guest, J.S. Impact of Growth Phases on Photochemically Produced Reactive Species in the Extracellular Matrix of Algal Cultivation Systems. Environ Sci (Camb) 2017, 3, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.H.; Yeh, H.Y.; Chou, P.H.; Hsiao, W.W.; Yu, C.P. Algal Extracellular Organic Matter Mediated Photocatalytic Degradation of Estrogens. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 209, 111818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, K.; Yu, C.P. Biotransformation of Estrone, 17β-Estradiol and 17α-Ethynylestradiol by Four Species of Microalgae. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019, 180, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruksrithong, C.; Phattarapattamawong, S. Removals of Estrone and 17β-Estradiol by Microalgae Cultivation: Kinetics and Removal Mechanisms. Environ Technol (U. K.) 2019, 40, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas, G.; López-Serna, R.; Scarcelli, P.G.; Serejo, M.L.; Boncz, M.Á.; Muñoz, R. Influence of the Hydraulic Retention Time on the Removal of Emerging Contaminants in an Anoxic-Aerobic Algal-Bacterial Photobioreactor Coupled with Anaerobic Digestion. Sci Total Environ 2022, 827, 154262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, F.; Sousa, C.A.; Sousa, H.; Santos, L.; Simões, M. Impact of Parabens on Microalgae Bioremediation of Wastewaters: A Mechanistic Study. Chem Eng J 2022, 442, 136374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, F.; He, Y.; Kushmaro, A.; Gin, K.Y.H. Effects of Benzophenone-3 on the Green Alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and the Cyanobacterium Microcystis Aeruginosa. Aquat Toxicol 2017, 193, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Luo, L.; Ma, X.Y.; Wang, X.C. Effect of Elevated Benzophenone-4 (BP4) Concentration on Chlorella vulgaris Growth and Cellular Metabolisms. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2018, 25, 32549–32561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Song, D. Enhanced Degradation of Bisphenol A: Influence of Optimization of Removal, Kinetic Model Studies, Application of Machine Learning and Microalgae-Bacteria Consortia. Sci Total Environ 2023, 858, 159876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Ouada, S.; Ben Ali, R.; Leboulanger, C.; Ben Ouada, H.; Sayadi, S. Effect of Bisphenol A on the Extremophilic Microalgal Strain Picocystis sp. (Chlorophyta) and Its High BPA Removal Ability. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2018, 158, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Microalgae | MeP | PrP | BuP | BP | BPA | E | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenedesmus sp. | 100.0±0.0% | 99.4±1.1% | 99.2±1.5% | 85.6±9.0% | 81.8±6.3% | 67.0±0.6% | This study |

| C. vulgaris | 100.0±0.0% | 100.0±0.0% | 100.0±0.0% | 62.1±9.1% | 89.9±2.0% | 83.0±2.0% | |

| C. reinhardtii | 100.0% | 100.0% | [31] | ||||

| S. obliquus | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||||

| C. pyrenoidosa | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||||

| C. vulgaris | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||||

| Tetradesmus obliquus, C. vulgaris, Pseudanabaena sp., Scenedesmus sp. and Nitzscha sp. | 89.0% | [58] | |||||

| C. vulgaris | 33.0-14.0% | [59] | |||||

| S. obliquus | 23.3–28.5% 1 | [32] | |||||

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | 58.4% 1 | [60] | |||||

| C. vulgaris | 14.0% 2 | [61] | |||||

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | 20.0-43.0% | [62] | |||||

| C. mexicana | 39.0% | [34] | |||||

| C. vulgaris | 28.0% | ||||||

| S. obliquus | 91.0% | [57] | |||||

| C. vulgaris | 52.0% |

| Compound | kO (h-1) (R2) | kLO (h-1) (R2) | kLOM (h-1) (R2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenedesmus sp. | C. vulgaris | |||

| MeP | 1.3·10-3 (0.868) | 1.1·10-3 (0.841) | 9.0·10-2 (0.983) | 3.8·10-1 (0.928) |

| PrP | 7.0·10-3 (0.831) | 4.0·10-3 (0.758) | 5.7·10-2 (0.968) | 7.4·10-2 (0.972) |

| BuP | 2.9·10-3 (0.951) | 2.8·10-3 (0.961) | 5.4·10-2 (0.982) | 7.5·10-2 (0.957) |

| BP | 1.3·10-2 (0.936) | 1.6·10-2 (0.958) | 1.1·10-2 (0.924) | 6.0·10-3 (0.901) |

| BPA | 2.0·10-3 (0.940) | 1.1·10-3 (0.956) | 2.1·10-2 (0.976) | 1.3·10-2 (0.815) |

| E | 5.9·10-3 (0.966) | 3.1·10-3 (0.954) | 5.2·10-3 (0.819) | 9.9·10-3 (0.805) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).