1. Introduction

Parvovirus infection has frequently been associated with gastrointestinal disease in a wide range of hosts and has been described in different species of birds, including waterfowls [

1,

2]. Diseases caused by waterfowl parvoviruses (WFPVs) cause serious economic losses in regions with intensive goose and duck production [

3,

4,

5].

Waterfowl parvovirus infection was first detected in China and described by Fang in 1956 [

6], primarily known and investigated by Derzsy and his team in Hungary in 1967. It was named after him, and described in goslings as a highly fatal disease characterized by anorexia, prostration, and death within 2 to 5 days [

7]. This disease is caused by goose parvovirus (GPV) [

8].

During the late 1980s, a new disease called Muscovy 3-week disease, caused by a related Muscovy duck parvovirus (MDPV), appeared in Muscovy ducks worldwide. This disease is characterized by mortality of between 10 and 80%, neurological, locomotor, and enteric signs, and surviving ducks permanently suffer from abnormal feather development and growth retardation [

9].

Generally, Pekin and mule duck breeds are resistant to classical WFPV infections. A new disease known as short beak and dwarfism syndrome (SBDS) has been reported in mule and Pekin ducks in several countries, including France, Poland, and China. SBDS is characterized by strong growth retardation, beak atrophy, and tongue protrusion [

10,

11,

12]. Based on virus isolation and molecular identification, a variant strain of GPV named novel goose parvovirus (NGPV) was identified as the causative agent of SBDS in ducklings, and it has been circulating since 2015 in China [

13].

WFPVs` genome is represented by approximately 5100 nucleotides of long linear single-stranded DNA with icosahedral symmetry and a diameter of 20–22 nm. Two main open reading frames (ORFs) are identified. The left 5′ ORF (ORF1) encodes nonstructural proteins (NS), which are involved in viral replication, transcription, and assembly. The right 3′ ORF (ORF2) encodes capsid viral proteins (Caps), including the structural proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3, which play important roles in tissue tropism, host range, and pathogenicity. WFPVs can be antigenically categorized into GPV-related or MDPV-related groups, based on their nucleotide sequences [

14,

15]. NGPVs isolated from SBDS cases belong to either the West European subgroup or the Chinese subgroup of the GPV-related group, as they share a strong antigenic relationship with classical GPV strains. Furthermore, genome comparison showed that the sequence similarity between NGPVs and GPVs (90% to 98%) was greater than that between NGPVs and MDPVs (78.6% to 85.0%). Therefore, it can be regarded as variant GPVs (13, 16-18).

Capsid proteins play an important role in virus host range, tropism, pathogenicity, and protective immune response, as they contain viral antigenic sites. These three capsid proteins, VP1, VP2, and, VP3 constitute the icosahedral capsid in a ratio of approximately 1:1:8 respectively [

19,

20]. Consequently, they are utilized in the creation of discriminating diagnostic tools, epidemiological monitoring of WFPVs, selection and evaluation of protective vaccines [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Owing to the difficulties facing WFPV isolation, conventional PCR technology has been used as the main screening and diagnostic tool not only for the detection of WFPVs but also for the differentiation between MDPVs and GPVs [

25,

26]. Recently, TaqMan-based real-time PCR (RT-PCR) has gained wide acceptance due to its high specificity and sensitivity (27, 28). As a result of high antigenic homology, especially between classical GPV and NGPVs, Sequence-independent techniques, such as next generation sequencing (NGS), have allowed the confirmatory identification and differentiation between NGPVs and GPVs [

1,

29]. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) has been used to detect parvovirus-positive signals in various organs [

30,

31].

Since 2019, SBDS outbreaks have been frequently recorded in different localities in Egypt among commercial Pekin and mule flocks, leading to drastic economic losses for farms` owners. The causative agent was isolated on primary duck embryo liver (DEL) cell culture, detected using conventional PCR, and identified by partial genome sequencing and phylogenic analysis of the VP1 gene as a variant GPV (NGPV) that clustered with the Chinese NGPVs in the same group [

32].

Most studies have investigated the negative impact of classical and variant GPVs on the digestive system and accompanying visceral organs [

31,

33] including our own original research [

34], with less interest in the immune system [

30,

35]. This relatively rare information motivated us in the present study to investigate GPV pathogenesis among immune organs in naturally occurring outbreaks in Egypt and the full genome sequencing of three Egyptian isolates using next generation sequencing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Considerations

Animal handling and sample collection were reviewed and approved by the ZU-IACUC committee at Zagazig University in Egypt (approval number: ZUIACUC/2/F/176/2022; approval date: 28/9/2022).

2.2. Clinical, Postmortem Examination and Sample Collection

A total of 99 diseased ducks, representing 25 flocks from different breeds (15 Pekin flocks, seven Muscovy flocks, two native flocks, and only one mule flock), ranged in age from 14 to 75 days and were collected from different localities in Sharkia Province, Egypt. All ducks hatched from vaccinated breeders, except for the native flocks. The study design, field assessment of the current state of parvovirus infections in ducks, and sample collection were carried out during a three-year period (2021–2023). The collected ducks, expected to have a parvovirus infection, were subjected to clinical and postmortem examinations.

Seventy-five pooled samples from immune organs of those 25 diseased duck flocks (three pools per flock, from thymus, bursa of Fabricius, and spleen samples) were harvested and stored at approximately 4°C in leak-proof containers with ice and preserved at -80°C for molecular detection. Representative samples from each flock were inoculated onto embryonating chicken eggs (ECE) via the allantoic cavity route and candled daily for seven days [

33]. The allantoic fluid was then harvested and tested using the rapid hemagglutination test to confirm the absence of any mixed infection with hemagglutinating (HA) agents, such as avian influenza and Newcastle disease viruses.

2.3. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical (IHC) Examination

Tissue specimens from the thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius were collected from all examined birds, preserved in neutral buffered formalin 10%, and routinely processed, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) [

36]. Tissue sections were examined using a Leica DM4 B light microscope (Leica, Germany) and captured using a Leica DMC 4500 digital camera (Leica, Germany) linked to LAS-X software (Leica, Germany).

Hyperimmune serum was prepared in four New Zealand rabbits against waterfowl parvovirus using DEPARMUNE® inactivated oil emulsion vaccine (Ceva-Phylaxia, Budapest, Hungary, Batch No: 001KG1D) via a series of injections (0.5 ml) following the schedule described by Samiullah et al. (2006) [

37]. Blood samples were collected and centrifuged to separate serum. The serum was purified via precipitation using ammonium sulfate [

38]. Purified IgG was used as the primary antibody at a dilution of 1:500 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

IHC was performed as described by Mesalam et al. (2021) [

39]. The retrieval of heat-induced antigen was conducted in a microwave oven for 15 min using Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-base, 1 mM EDTA solution, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9). Tissue slides were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The endogenous peroxidase blocking step was performed by adding three drops of 3% H2O2 (Bio-SB, CA, USA) to tissue sections and incubating for 10 min. Tissue slides were incubated with the primary antibodies (rabbit anti-waterfowl parvovirus, 1:500 in PBS) for 2 h in a humidity chamber, followed by washing with PBS and incubation with goat anti-rabbit HRP-labelled secondary antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, a DAB Substrate Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used for substrate detection. As a negative control, the primary antibody was replaced by negative serum on parvovirus-infected immune tissue specimens. Additionally, normal non-infected duck immune tissues were incubated with the primary anti-waterfowl parvovirus antibodies [

40].

2.4. DNA Extraction, Conventional and TaqMan Real-Time PCR Amplification

DNA was extracted from the bursa of Fabricius, thymus, and spleen tissue pools using the GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific™, Baltics UAB, Lithuania, Catalogue No: K0721) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA extracts were quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Oligonucleotide primers (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin, Germany) used for conventional PCR and TaqMan real-time PCR are shown in (

Table 1).

27 tissue pools from Muscovy and native flocks were detected by conventional PCR assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the DreamTaq PCR Master Mix (2X) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific™, Baltics UAB, Lithuania, Catalogue No: K1071) and performed with two PCR reactions for each sample. A total of 50 μL of each PCR reaction was optimized as follows: 25 µL of 2X DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix, 1 µL forward primer, 1 µL reverse primer (10 μmol/l each), 5 µL DNA template, and 18 µL nuclease-free water. The thermal cycling conditions were optimized as follows: one cycle of 95°C 1 min (initial denaturation), followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The amplification products were subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis using a ready-to-use GeneRuler 1 kb DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific™, Baltics UAB, Lithuania, Catalogue No: SM0313).

48 tissue pools from Pekin and mule flocks were detected using TaqMan real-time PCR. A total of 25 μL of PCR reaction per sample was done by adding 12.5 μL of Brilliant Multiplex QPCR Master Mix (Agilent technologies, USA, Catalog no: 600553), 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μmol/l each), 1 μL of probe (10 μmol/l), 3 μL of DNA template, and nuclease-free water in an amount to adjust the total reaction volume to 25 μl. The thermal profile was set as: 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s using the AriaMx Real-time PCR System (Agilent Technologies, USA). Positive TaqMan real-time PCR samples were resubmitted to discriminative conventional PCR to detect any mixed infection with MDPV.

2.5. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) and Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA)

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was performed to summarize and visualize the data and assess the associations between the presence of various gross lesions and microscopic features in different breeds and ages of the examined ducks. Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) was used in combination with MCA to profile and group the ducks or variables with similar characteristics. MCA and HCA provided convenient and easy-to-interpret analytical tools for assessing categorical data relationships [

41], and were performed using the “factoMineR” package R-version 3.4.3 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

2.6. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Library preparation was done as follows: viral DNA fragmentation into smaller pieces with adapters` ligation to its end. These adapters contained sequences that were recognized by the Illumina sequencing platform and allowed for amplification and sequencing of the DNA fragments using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA, Catalogue No: FC-131-1024). The prepared DNA library was loaded onto the Illumina MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, USA, Serial no: SY-410-1003). The sequencing process involved clustering of the DNA fragments on a flow cell, followed by the cyclic addition of fluorescently labelled nucleotides, which were incorporated into the growing DNA strands. The fluorescent signals generated during this process were detected using the sequencer and used to determine the sequence of each DNA fragment.

Raw sequencing data were processed and analyzed using the bacterial and viral bioinformatics resource center (BV-BRC) (bv-brc.org) and molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version.11 (MEGA.11) software, and the data were submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (

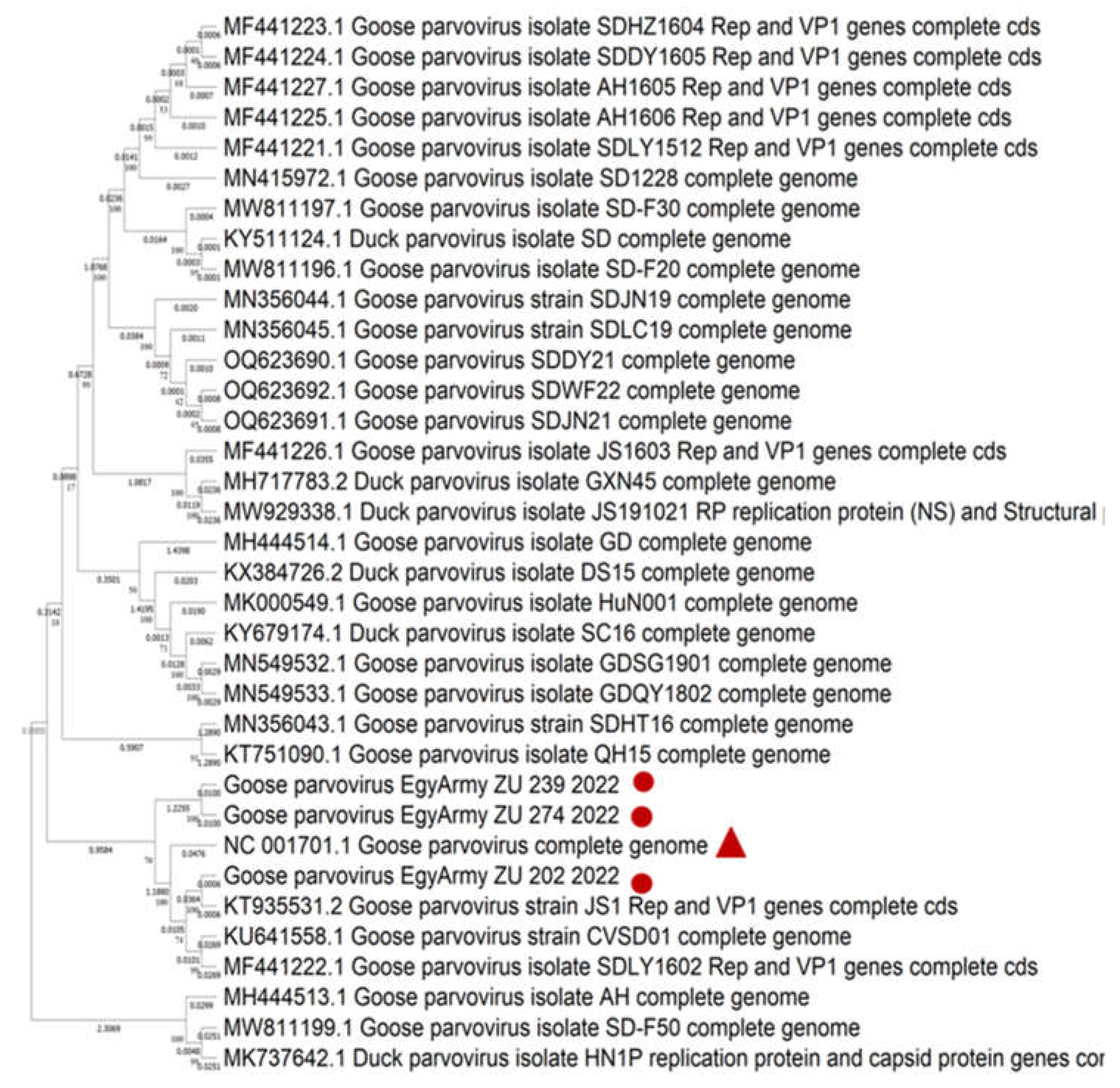

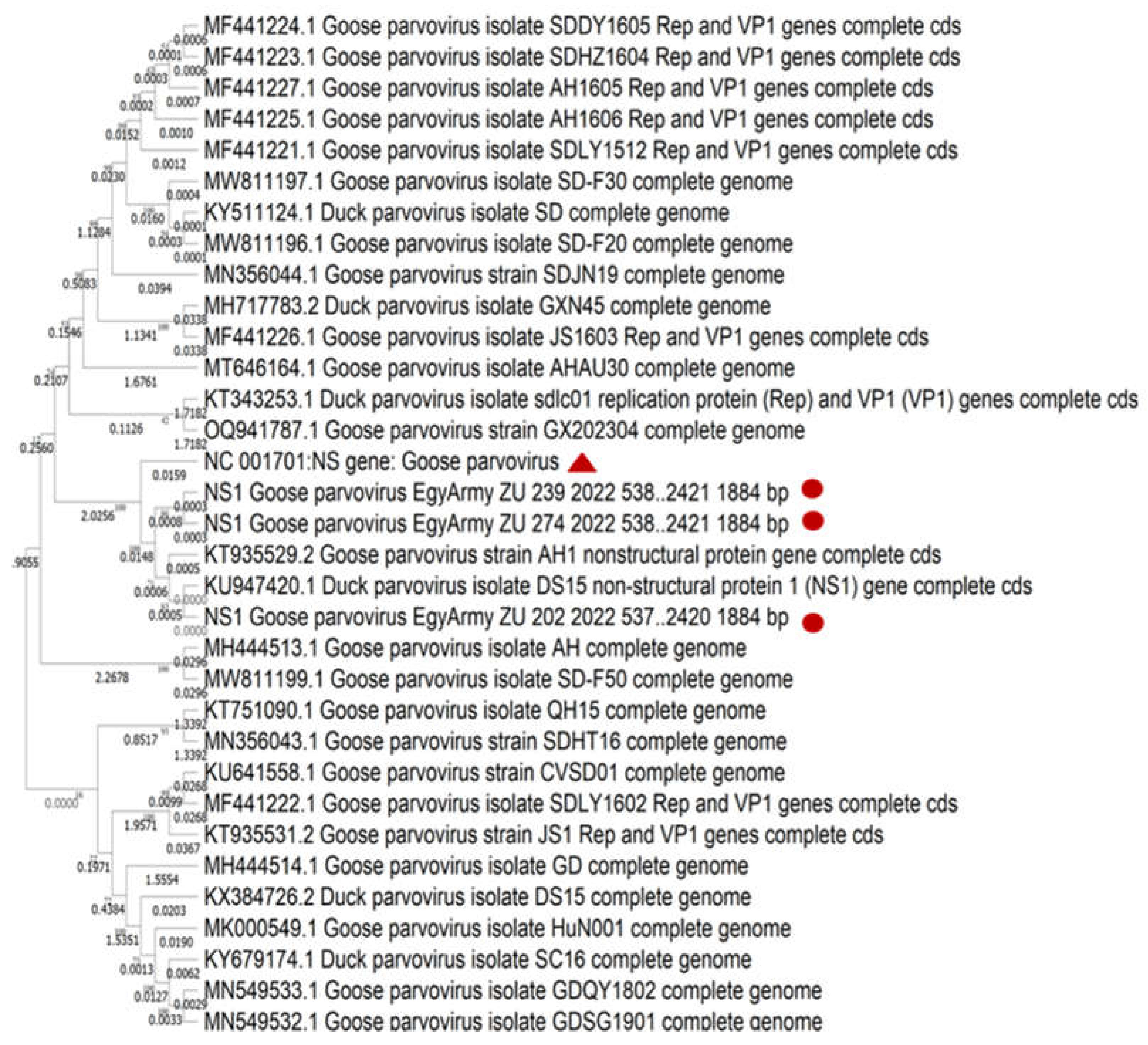

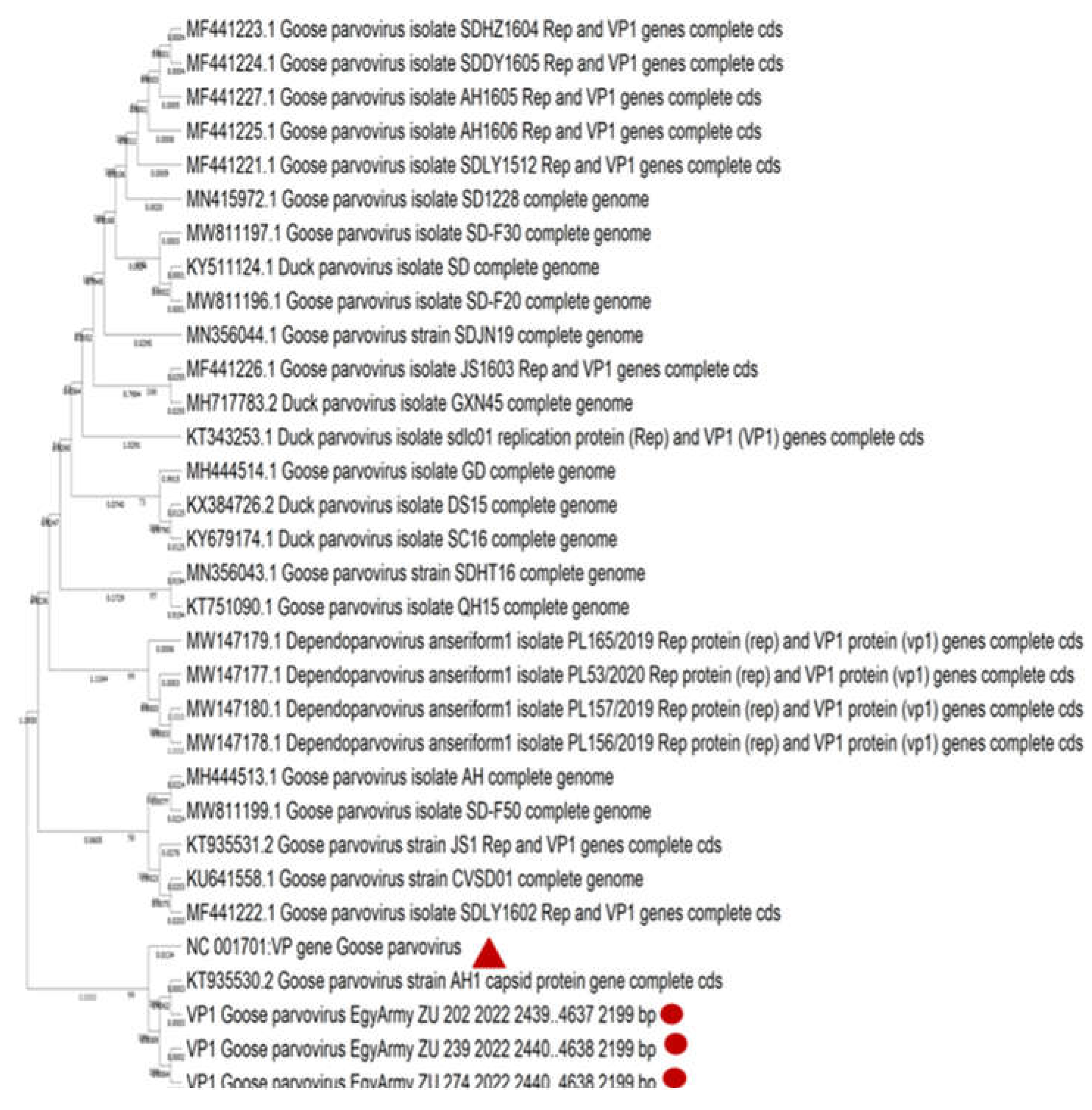

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The phylogenetic tree was designated based on BLAST analysis of the three whole genome-sequenced isolates in the current study using the NCBI database. Up to 30 NGPV complete genome sequences, which were much closer to NGPV isolates in the present study, were selected to construct the phylogenetic tree using MEGA.11 software. The NCBI reference GPV virulent B strain (Accession no: NC_001701) was blasted with the three identified NGPV strains and inserted into the whole genome, capsid protein (VP), and nonstructural (NS) phylogenetic trees to determine the nucleotide diversity among them.

VP sequences of two European strains, the French Hoekstra vaccine strain (accession number: AY496907 for VP1/VP2, and AY496894 for VP3), and the Hungarian LB vaccine strain (accession number: AY496900 for VP1/VP2, and AY496887 for VP3) [

21] were blasted with the strains in the current study to determine the VP nucleotide homology. The viral genome was annotated and interpreted using the Vgas viral genome annotation system (

http://guolab.whu.edu.cn/vgas ) [

42]. All procedures for molecular identification were performed according to the biosafety measures in Biodefense Center for Infectious and Emerging Diseases, Ministry of Defense, Egypt.

4. Discussion

As a continuing threat, GPV negatively affects the duck industry in Egypt, even with regular vaccination, particularly in commercial flocks. The present study aimed to identify and investigate the circulating strains of GPV and their impact on immune organs in different duck breeds and ages in Sharkia Province, Egypt. Twenty-five duck flocks exhibiting a clinical history of suspected GPV infection were investigated based on the clinical picture, postmortem and histopathological examination, PCR detection, IHC, statistical analysis of risk factors affecting the frequency of macroscopic and microscopic features, and full genome sequencing.

The variation in the morbidity rate of NGPV infection among flocks could be attributed to either variation in host susceptibility between Muscovy and Pekin ducks or the presence of maternally derived antibodies (MDA) [

10,

13,

43], comparable to the current study in which all examined ducks (except native flocks) hatched from vaccinated breeders, so there was a partial level of protection against the severe state of the disease. The morbidity rate after NGPV experimental challenge was higher (70%) in one-day MDI-free mule ducklings than in one-day mule ducklings hatched from parvovirus-vaccinated breeders (33%) [

10]. A high morbidity rate was recorded after NGPV experimental challenge either in mule (80%) or Cherry Valley (90%) three-day-old MDI-free ducklings [

16].

Regarding the low mortalities in the present study, Zhu et al. (2022) also recorded low mortality rate of 1% in NGPV-naturally infected Cherry Valley ducks [

44]. Also, naturally infected mule and Cherry Valley flocks displayed 2% mortality rate [

17]. While Palya et al. (2009) recorded 3 and 5% mortality rates in NGPV-experimentally infected mule ducklings either hatched from vaccinated or non-vaccinated breeders, respectively [

10]. Moreover, NGPV can be PCR-detected and cause postmortem and histopathological lesions in different organs without causing any mortality [

10,

33]. Lower mortality and smaller beak are the major discriminators between fully susceptible, MDI-free, classical GPV, and NGPV-infected ducks. As classical GPV does not severely infect mule and Pekin duck breeds, NGPV, as a variant GPV strain, is not completely adapted to cause severe disease in mule and Pekin ducks, which might be the reason for the low mortality caused by this variant strain in such breeds [

10,

17,

35,

45].

In the current study, common clinical signs were recorded in examined ducks of variable ages (14-75 days old). Similarly, there was a wide spectrum of age susceptibility, as the disease was recorded in all ducks from one day old until 50 days of age [

46]. Comparable clinical features have been previously reported in several publications that recorded WFPV infections over the years [

1,

2]. The same clinical signs, in addition to short beaks with protruding tongues, have been recorded among NGPV-infected ducks [

10,

13], and were also recorded in the examined Muscovy and native flocks, except for tongue protrusion. Xiao et al. (2017) investigated the pathogenicity of NGPV M15 strain in different duck breeds including Muscovy breed. Although NGPV-infected Muscovy ducklings suffered from severe growth retardation, no Muscovy ducklings showed tongue protrusion and the decrease in beak length and width was insignificant compared to non-infected ducks [

43]. Moreover, Zhu et al. (2022) profoundly compared the NGPV pathogenicity between Muscovy and Pekin breeds and recorded that both Cherry Valley-origin NGPV (CVD21) and Muscovy-origin NGPV (MD17) were able to experimentally infect Cherry Valley Pekin ducklings, causing the appearance of the typical clinical picture of SBDS, while obvious clinical signs were observed in the Muscovy ducklings infected with MD17, mainly growth retardation and decreased beak width and length, without tongue protrusion [

44].

In parvovirus-infected flocks, atrophy of lymphoid tissues, including the bursa, thymus, and spleen was recorded during the postmortem examination of clinically diseased ducks from different breeds [

45,

47,

48]. Atrophy of the immune organs was more prominent in Pekin ducks, which could be attributed to the relative increase in disease severity in this breed [

16,

33] compared to other duck breeds [

43].

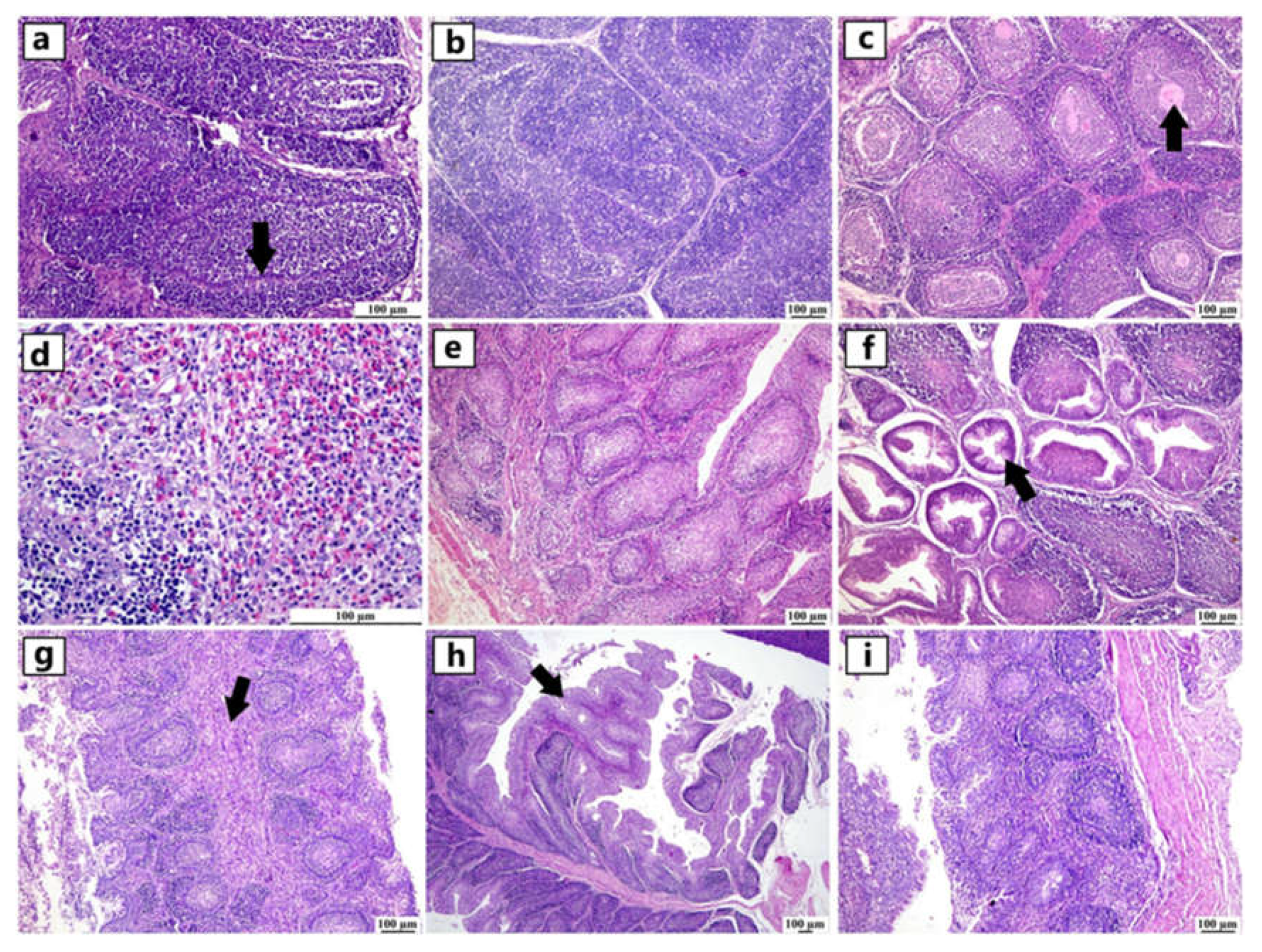

The histopathological findings were also previously recorded in several reports investigating WFPVs` pathogenesis under natural or experimental circumstances including; necrotic thymic medulla with Hassel`s corpuscle disintegration [

33], depletion and degeneration of thymic lymphocytes [

30,

47,

49], disappearance of normal bursal histological morphology accompanied with atrophy of bursal lymph follicles and lymphocytic depletion [

5,

35,

47,

49], Spleen degeneration characterized by lymphocytic depletion [

5,

30,

44,

47], and reticular cell proliferation [

10].

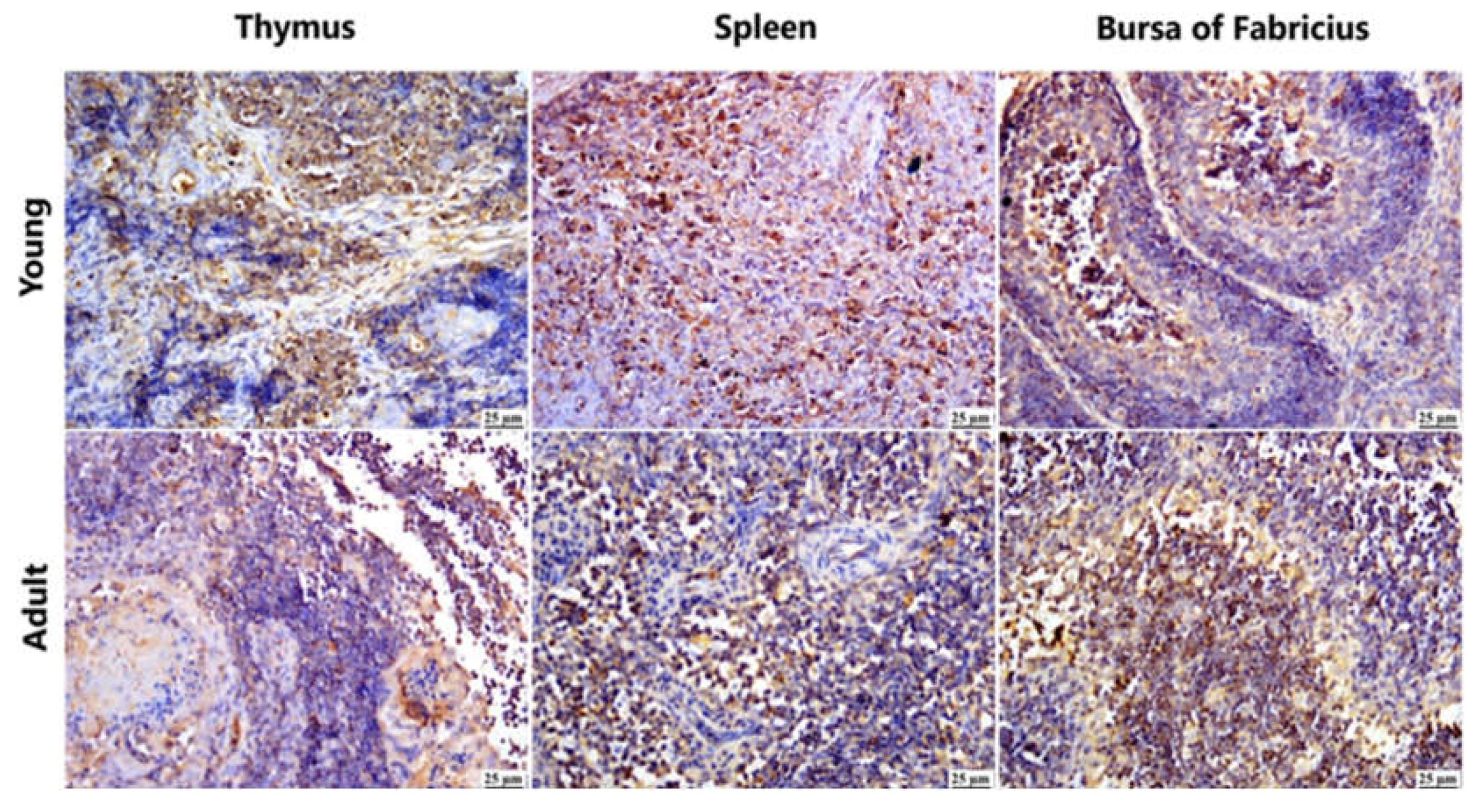

Surprisingly, no previous IHC work was conducted for NGPV infection to compare with the IHC findings in the current study. Only GPV was previously detected by immunoassay in the spleen of experimentally-infected goslings [

50], whereas it was detected in all immune organs, including the bursa, thymus, and spleen, after the experimental challenge with GPV in Cherry Valley ducklings [

30]. Histopathological and IHC findings were confirmed using molecular identification, which established the NGPV infection with the complete exclusion of MDPV infection.

Primer selection is critical for distinguishing between MDPVs and GPVs (including classical and variant strains) in the present study. Genomic comparison between GPVs and MDPVs revealed that they share 80%–84% nucleotide similarity at the genome level [

15,

25]. These data indicate that false PCR results can be obtained if primers are not designed to target specific regions. To overcome this drawback, we used a conventional PCR assay based on NS phylogenetic analysis of MDPV and GPV isolates and provided an alternative tool to detect and differentiate between MDPVs and GPVs with increased accuracy [

25]. We also performed a TaqMan RT-PCR assay based on the characteristic variable regions of NS genes in GPVs and MDPVs for the specific detection of classical GPV and NGPV with total exclusion of MDPV detection probability. Moreover, classical GPV and NGPV could be distinguished using this assay coupled with host specificity, as the samples were considered NGPV positive if they were successfully detected in Pekin and mule ducks, and considered classical GPV positive if it was successfully detected in Muscovy ducks and goslings [

28]. However, this concept was drooped in our study, while we confirmed the variant GPV (NGPV) in both Muscovy ducks and Pekin ducks using NGS.

The PCR assay revealed an unexpected result as the bursa was the primary organ for NGPV detection (76%) among the examined flocks. Unfortunately, there are few available records in which NGPV was detected in the bursa in naturally-occurring NGPV outbreaks. The few records could be attributed to pooled mixed organ samples submitted for PCR detection, so the organ of detection could not be defined [

51]. GPV copy numbers in the spleen, thymus, and bursa following experimental infection in Muscovy ducklings were detected as early as the first dpi until the end of the observation period [

52]. Following experimental infection in goslings, GPV viral load was detected in all immune organs [

50], and was significantly higher than GPV viral load in any other organ [

53]. Comparably, these immune organs could be considered the primary sites of invasion in ducks after NGPV infection; in turn, they might massively hurt and impair the immune performance of infected ducks, as evidenced by the abovementioned negative impact on the immune system of birds under study.

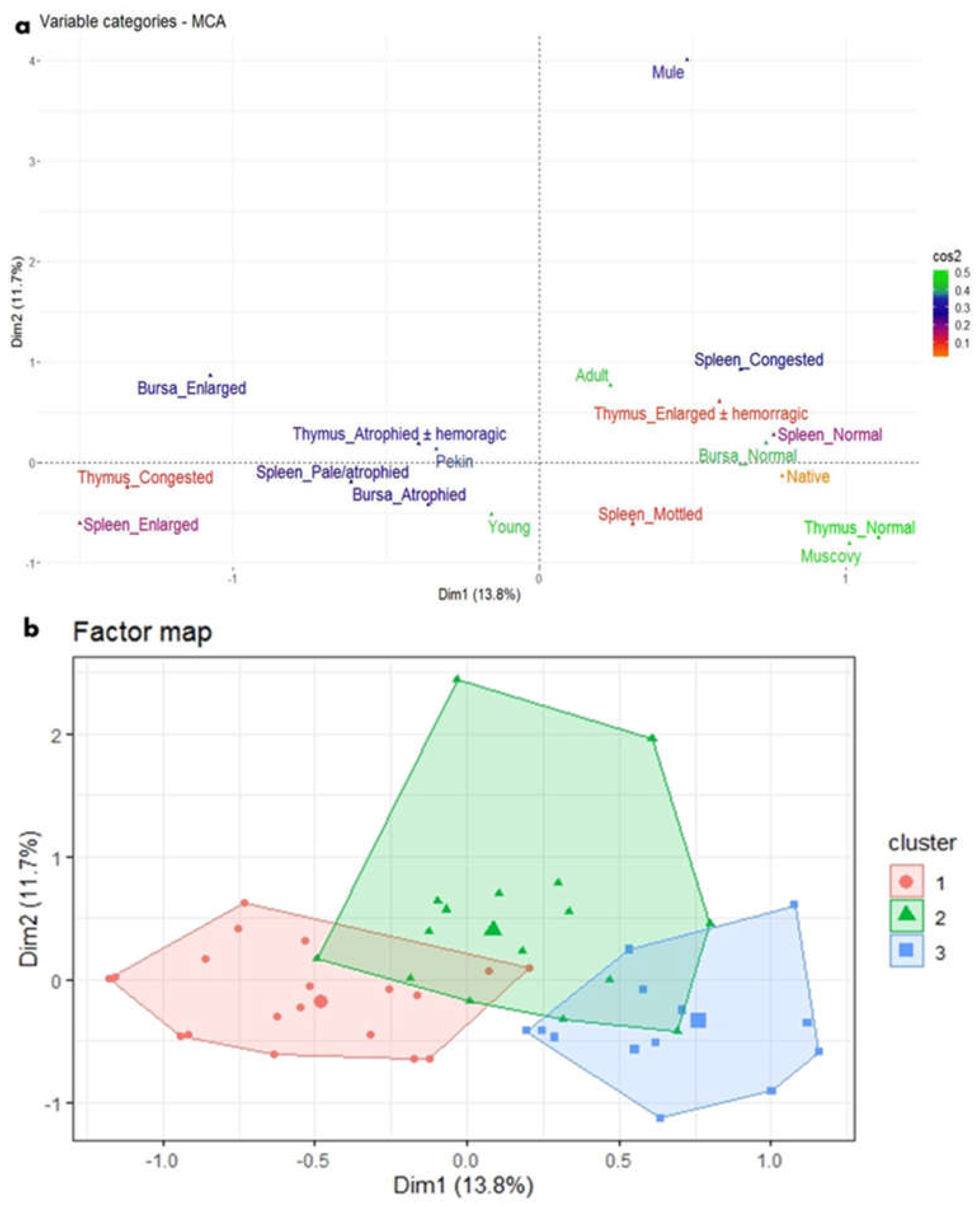

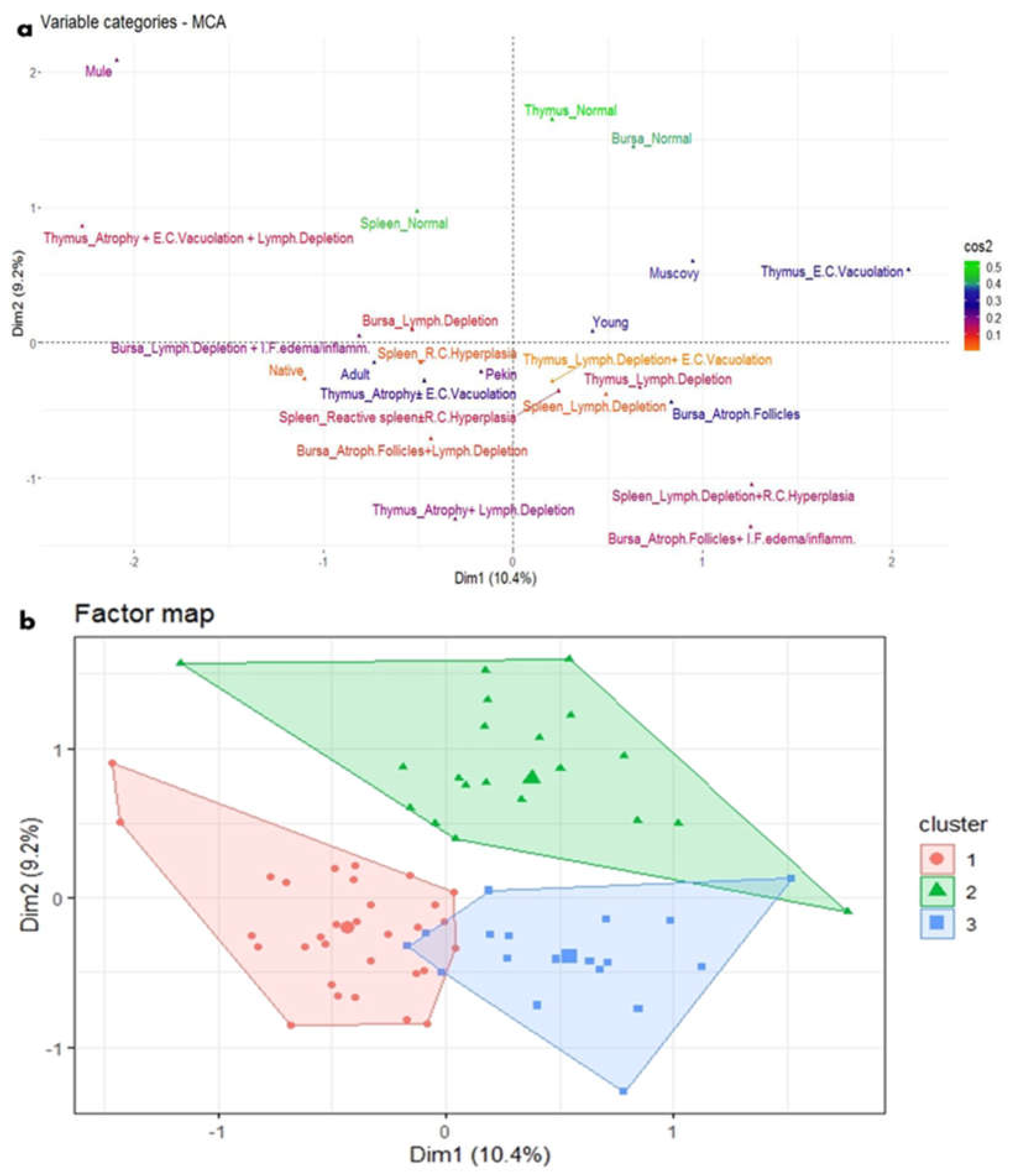

Based on the statistical analysis of the macroscopic and microscopic features to determine lesion frequency in relation to the age and breed of examined ducks using MCA and HCA, the authors in their current work declared that in all duck ages and breeds, immune organs were negatively affected, with a variable degree of severity. In parvovirus-infected young waterfowls, atrophy of lymphoid tissues including the bursa, thymus, and spleen was recorded during pathological examination of goslings and Muscovy ducklings [

47], Cherry Valley Pekin ducklings [

45], mule ducklings [

48], and thymic petechial hemorrhage [

48,

49], as the ducklings hatched from non-vaccinated breeders. In infected young Pekin and mule ducks, a congested, enlarged thymus with or without petechial hemorrhage [

13,

30,

33,

45], and splenomegaly [

30,

33] were observed, as evidenced in the present study. Although Muscovy and native ducks were apparently normal, the microscopic picture provided another perspective on immune impairment.

A typical microscopic picture of lymphoid atrophy was identified in young Pekin ducks as well as in adult Pekin and native ducks. In previous studies, analogous histopathological changes were recorded: thymus atrophy with lymphocytes and reticular cells scattered in the necrosis, and thymus corpuscle disintegration was observed after experimental infection in NGPV-infected Cherry Valley Pekin ducklings [

33], depletion and degeneration of thymic lymphocytes in GPV-infected Cherry Valley Pekin ducklings [

30], disappearance of normal bursal histological morphology accompanied by atrophied bursal lymph follicles and lymphocytic depletion in NGPV-infected Pekin ducklings [

35] and NGPV-infected goslings [

5]. In addition, splenic lymphocyte necrosis and depletion in GPV-infected Cherry Valley ducklings [

30], NGPV-infected Pekin and Muscovy ducklings [

44], and reticular cell proliferation in NGPV-infected mule ducklings [

10] were also recorded and supported the findings of the present study.

The low cross protection of breeder vaccination in examined Pekin ducklings and the absence of any applied vaccination regimen in examined adult Pekins led to microscopically severe disease at both ages, confirmed by the PCR percentage of detection (73.3%). The reason why native ducks expressed the disease only in the adult age with the 83.3% percentage of PCR detection in despite of hatching from non-vaccinated breeders may be due to the natural resistance of the native breed compared with foreign duck breeds (Pekin and mule). Less frequent normal histological features in immune organs were recorded and only within Muscovy ducks, as the examined Muscovy flocks were only 42.9% PCR positive reactors. Serious pathological changes in the immune organs may cause immunosuppression, resulting in an enhanced opportunity for co-infection with other viral or bacterial pathogens and potentially leading to vaccination failure, which is highly indicative of WFPVs' (including NGPV) tropism in the immune system [

30,

48,

49,

50,

53].

Based on PCR detection, all isolates in the current study were identified as GPVs. However, NGS and phylogenetic analysis of the whole genome sequences of three representative isolates proved to be NGPVs. Phylogenetic analysis of NGPV strains in the current study revealed they were closely related to Chinese NGPV (up to 99%) isolates, as recent studies from Poland and Vietnam declared about their isolates [

12,

51].

Comparably, many recent phylogenetic analyses of NGPVs worldwide have dedicated a close relationship to Chinese NGPV strains with less genetic relationship with classical GPVs. Two Chinese AH and GD NGPV isolates had nucleotide homology with other NGPV isolates ranging from 93.4 to 99.9% and 89.7-96.7% identity with classical GPV isolates at the whole genome level [

17]. The HuN18 strain shared 96.8%-99.0% identity with other NGPVs, while it shared 92.9%-96.3% identity with classical GPV [

54]. Both GDQY1802 and GDSG1901 NGPVs had 96.2–99.5% whole genome nucleotide identity with NGPVs and 92.7–96.3% with GPVs [

18]. The genomes of three NGPV Chinese strains, SDHT16, SDJN19, and SDLC19, shared 98.9%–99.7% whole genome nucleotide similarity with each other but only 95.2%–96.1% similarity with the classical GPVs, including strain B [

55]. All previously reported alignment data indicated that the similarity among NGPVs was still higher than the similarity between NGPVs and GPVs, as we declared in the present study. Gene annotation analysis of the identified NGPV strains was also within the same range as a recent genetic map for NGPV revealed [

56].

Regarding European vaccine strains currently used in Egypt in vaccination programmes against WFPVs, the percentage of VP nucleotide identity between the identified NGPV strains under the current investigation and those vaccine strains (

Table 3) might be insufficient for the complete protection against circulating NGPVs and SBDS prevention. Commercially used vaccines have not included NGPV strains until now; therefore, they do not produce such great cross-protection in NGPV-infected flocks. This may explain why they were highly susceptible to infection, and could justify the severe atrophy lesions in immune organs. Our deduction was confirmed by a comparative study in which all MDI-free mule ducklings were GPV- and NGPV-positive PCR reactors until six weeks post-infection, regardless of the age at which the ducklings were challenged. However, ducklings from vaccinated breeders were only NGPV-positive PCR reactors until the fifth week after the challenge [

10].

Consequently, it has been recommended that there is a need to evaluate the protective efficacy of classical GPV vaccines against NGPV and update the available commercial vaccines to include recent isolates [

17]. NGPV incidence seems to be attributed to the alteration of host ranges of GPV caused by virus variation [

57]. NGPV host susceptibility and evolution are gradually expanding among waterfowls, consequently leading to vaccination failure because of outdated commercial vaccines and/or defects in the vaccination regimen itself [

18,

43].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.L, A.E, A.A.M.E, M.G.S, and S.S.H.; Software, M.G.S, H.F.G, and M.F.E.; Resources, M.G.S, M.R.M, A.S.E, K.S.R, and E.K.; Validation, S.S.H, M.G.S, and A.A.M.E.; Investigation, S.S.H, H.F.G, M.R.M, N.I.A.G, and A.A.M.E.; Visualization, S.S.H, R.M.E, H.F.G, M.R.M, N.I.A.G, M.G.S, and A.A.M.E.; Methodology, S.S.H, R.M.E, H.F.G, M.R.M, N.I.A.G, M.F.E, and M.G.S.; Writing – original draft, S.S.H, H.F.G, M.R.M, and A.A.M.E. Writing – review and editing, S.S.H, R.M.E, and A.A.M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Clinical signs and gross lesions of naturally NGPV-infected flocks. (a) Abnormal feathering and skin redness in the adult Pekin ducks. (b) Short beak with protruding tongue in the Pekin duck. (c) The growth retarded Pekin duckling compared to the normal one in the same flock. (d) The growth retarded Muscovy duck compared to the normal one in the same flock. (e) Whitish diarrhea, general weakness, and abnormal feathering in back and neck regions in the Muscovy duckling. (f) Bursal enlargement and (g) Bursal atrophy compared to the normal one (h) in the same Pekin flock. (i) Thymus enlargement with hemorrhage and (j) Thymus congestion in both adult Muscovy and Pekin ducks respectively. (k) Thymus atrophy in the Muscovy duckling compared to normal one in the same flock (l). Spleen mottling (m) and enlargement (n) in adult Muscovy and Pekin ducks respectively. (o) A pale atrophied spleen in the young Pekin duck compared to the normal spleen in the same flock (p).

Figure 1.

Clinical signs and gross lesions of naturally NGPV-infected flocks. (a) Abnormal feathering and skin redness in the adult Pekin ducks. (b) Short beak with protruding tongue in the Pekin duck. (c) The growth retarded Pekin duckling compared to the normal one in the same flock. (d) The growth retarded Muscovy duck compared to the normal one in the same flock. (e) Whitish diarrhea, general weakness, and abnormal feathering in back and neck regions in the Muscovy duckling. (f) Bursal enlargement and (g) Bursal atrophy compared to the normal one (h) in the same Pekin flock. (i) Thymus enlargement with hemorrhage and (j) Thymus congestion in both adult Muscovy and Pekin ducks respectively. (k) Thymus atrophy in the Muscovy duckling compared to normal one in the same flock (l). Spleen mottling (m) and enlargement (n) in adult Muscovy and Pekin ducks respectively. (o) A pale atrophied spleen in the young Pekin duck compared to the normal spleen in the same flock (p).

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of thymus from different infected duck flocks (H&E). Young Pekin duck showed atrophy of thymus gland (a). Young Pekin duck showed an atrophied thymus with prominent decrease of cortical width giving the appearance of increased medullary size (arrow) (b). Young Pekin duck showed lymphoid depletion in the thymic cortex as demonstrated by remaining lymphocytes with pyknotic nuclei (necrotic/ apoptotic cells) (arrow) (c). Adult Pekin duck showed accumulation of an abundant eosinophilic necrotic material in the thymic medulla (arrow) (d). Adult Pekin duck showed severe thymic atrophy illustrated by presence of few lymphoid cells within this remnant of thymus, thymic (Hassall 's) corpuscles are prominent in the medulla (e). Adult Pekin duck showed an extensive damage and necrosis of thymic gland with the total absence of demarcation between cortex and medulla in the thymic lobules, accumulation of necrotic debris and vacuolation of epithelial cells (arrow) (f).

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of thymus from different infected duck flocks (H&E). Young Pekin duck showed atrophy of thymus gland (a). Young Pekin duck showed an atrophied thymus with prominent decrease of cortical width giving the appearance of increased medullary size (arrow) (b). Young Pekin duck showed lymphoid depletion in the thymic cortex as demonstrated by remaining lymphocytes with pyknotic nuclei (necrotic/ apoptotic cells) (arrow) (c). Adult Pekin duck showed accumulation of an abundant eosinophilic necrotic material in the thymic medulla (arrow) (d). Adult Pekin duck showed severe thymic atrophy illustrated by presence of few lymphoid cells within this remnant of thymus, thymic (Hassall 's) corpuscles are prominent in the medulla (e). Adult Pekin duck showed an extensive damage and necrosis of thymic gland with the total absence of demarcation between cortex and medulla in the thymic lobules, accumulation of necrotic debris and vacuolation of epithelial cells (arrow) (f).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of spleen from different infected duck flocks (H&E). Young Muscovy ducks with reactive lymphoid follicles (germinal centres), consisting of a nodular collection of large lymphoblast-like cells enclosed by a thin connective tissue capsule (arrows) (a). Young Pekin ducks with lymphocytic depletion illustrated by granular debris within the vacuolar spaces of apoptotic cells (arrow) (b). Young Pekin ducks showed severe loss of lymphocytes in white pulps and were replaced by fibrinous deposits (arrows) (c). Adult Pekin ducks` tissue sections at higher magnification displayed the paucity of lymphocytes in the white pulp (d). Young Muscovy ducks with obvious hyperplasia of ellipsoidal reticular cells around penicilliform capillaries (arrow) (e). Young Pekin ducks with infarcted areas separated with haemorrhagic margins (arrow) (f).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of spleen from different infected duck flocks (H&E). Young Muscovy ducks with reactive lymphoid follicles (germinal centres), consisting of a nodular collection of large lymphoblast-like cells enclosed by a thin connective tissue capsule (arrows) (a). Young Pekin ducks with lymphocytic depletion illustrated by granular debris within the vacuolar spaces of apoptotic cells (arrow) (b). Young Pekin ducks showed severe loss of lymphocytes in white pulps and were replaced by fibrinous deposits (arrows) (c). Adult Pekin ducks` tissue sections at higher magnification displayed the paucity of lymphocytes in the white pulp (d). Young Muscovy ducks with obvious hyperplasia of ellipsoidal reticular cells around penicilliform capillaries (arrow) (e). Young Pekin ducks with infarcted areas separated with haemorrhagic margins (arrow) (f).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of bursa of Fabricius from different infected duck flocks (H&E). Young Pekin ducks showed depletion of lymphoid follicles with prominent epithelial cells located between cortex and medulla (arrow) (a). Adult Muscovy ducks showed reactive lymphoid follicles with increasable depleted lymphocytes, demonstrated by vacuolar spaces (b). Young Pekin ducks showed severely damaged follicles with cystic spaces in the medullary area containing proteinaceous exudates (arrow) (c). Adult Muscovy ducks` tissue sections at higher magnification showed an expansion of the interfollicular connective tissue with many heterophils and macrophages (d). Adult Pekin ducks with marked loss of lymphocytes in lymphoid follicles (e). Adult Pekin ducks showed collapsed plica and mucosal epithelial cells started to fold into the damaged follicles; note that the epithelium cells appeared as ductal structures due to the sectioning plane (arrow) (f). Young Pekin ducks showed marked atrophied follicles and expansion of the interfollicular spaces with abundant fibroplasia and inflammatory cell aggregates (arrow) (g). Young Muscovy ducks with an extensive folding of plica epithelium (arrow) (h). Young Pekin ducks showed atrophied bursa with marked reduction of bursa folds and decreased number of lymphoid follicles (i).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of bursa of Fabricius from different infected duck flocks (H&E). Young Pekin ducks showed depletion of lymphoid follicles with prominent epithelial cells located between cortex and medulla (arrow) (a). Adult Muscovy ducks showed reactive lymphoid follicles with increasable depleted lymphocytes, demonstrated by vacuolar spaces (b). Young Pekin ducks showed severely damaged follicles with cystic spaces in the medullary area containing proteinaceous exudates (arrow) (c). Adult Muscovy ducks` tissue sections at higher magnification showed an expansion of the interfollicular connective tissue with many heterophils and macrophages (d). Adult Pekin ducks with marked loss of lymphocytes in lymphoid follicles (e). Adult Pekin ducks showed collapsed plica and mucosal epithelial cells started to fold into the damaged follicles; note that the epithelium cells appeared as ductal structures due to the sectioning plane (arrow) (f). Young Pekin ducks showed marked atrophied follicles and expansion of the interfollicular spaces with abundant fibroplasia and inflammatory cell aggregates (arrow) (g). Young Muscovy ducks with an extensive folding of plica epithelium (arrow) (h). Young Pekin ducks showed atrophied bursa with marked reduction of bursa folds and decreased number of lymphoid follicles (i).

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph demonstration of NGPV antigen in different immune organs of various infected flocks (IHC). Positive expression was detected in the thymic lymphocytes in the cortex and, to a lesser extent, in the medulla. The spleen showed diffuse positive expression of viral antigen in the bursa-dependent lymphoid follicle and peri-ellipsoidal lymphoid sheath (PELS) of young and adult infected duck flocks. The bursal lymphoid follicles exhibited a positive reaction, demonstrating viral antigen mainly in the medullary lymphocytes.

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph demonstration of NGPV antigen in different immune organs of various infected flocks (IHC). Positive expression was detected in the thymic lymphocytes in the cortex and, to a lesser extent, in the medulla. The spleen showed diffuse positive expression of viral antigen in the bursa-dependent lymphoid follicle and peri-ellipsoidal lymphoid sheath (PELS) of young and adult infected duck flocks. The bursal lymphoid follicles exhibited a positive reaction, demonstrating viral antigen mainly in the medullary lymphocytes.

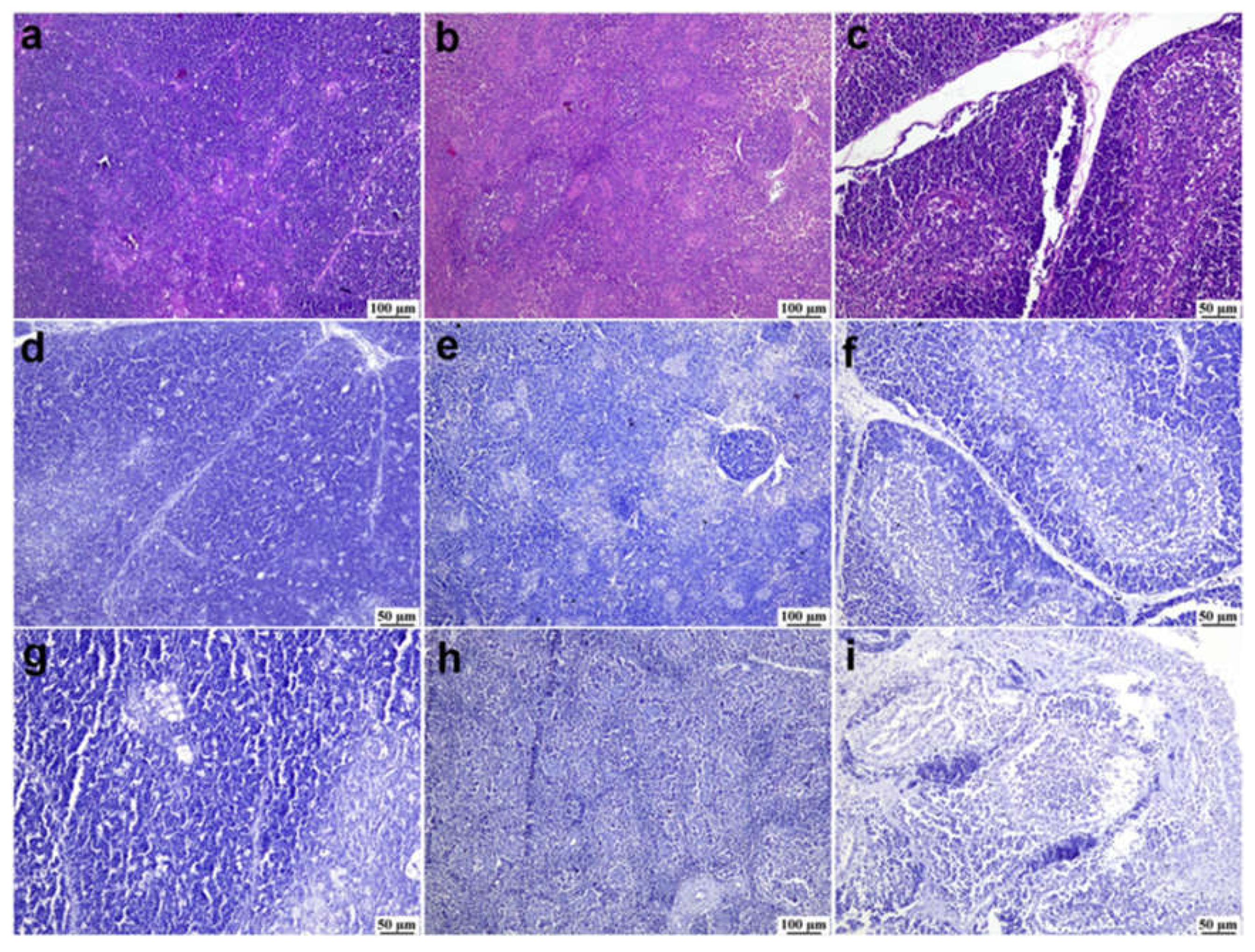

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of bursa, thymus, and spleen of non-infected ducks. (a-c) Normal histological structure of the thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius from flocks free from NGPV infection, respectively (H&E). (d-f) Negative expression of the viral antigen in the thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius of the non-infected flocks, respectively (IHC). (g-i) Negative expression of viral antigen in the thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius of the infected flocks after the deletion of primary antibody incubation step, respectively (IHC).

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of bursa, thymus, and spleen of non-infected ducks. (a-c) Normal histological structure of the thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius from flocks free from NGPV infection, respectively (H&E). (d-f) Negative expression of the viral antigen in the thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius of the non-infected flocks, respectively (IHC). (g-i) Negative expression of viral antigen in the thymus, spleen, and bursa of Fabricius of the infected flocks after the deletion of primary antibody incubation step, respectively (IHC).

Figure 7.

MCA and HCA of macroscopic lesions in relation to the age and breed of NGPV-infected ducks. (a) The MCA plot revealed the relationship between the age of ducks, duck breeds, and the recorded macroscopic lesions in the spleen, thymus, and bursa of Fabricius. The closer the points were to each other, the higher the relationship was. The points that were separate and far away considered outliers and were less frequent. (b) The HCA factor map of the macroscopic lesions which were clustered into three clusters, in relation to the age and breed of the examined ducks.

Figure 7.

MCA and HCA of macroscopic lesions in relation to the age and breed of NGPV-infected ducks. (a) The MCA plot revealed the relationship between the age of ducks, duck breeds, and the recorded macroscopic lesions in the spleen, thymus, and bursa of Fabricius. The closer the points were to each other, the higher the relationship was. The points that were separate and far away considered outliers and were less frequent. (b) The HCA factor map of the macroscopic lesions which were clustered into three clusters, in relation to the age and breed of the examined ducks.

Figure 8.

MCA and HCA of microscopic lesions in relation to the age and breed of NGPV-infected ducks. (a) The MCA plot revealed the relationship between the age and the recorded microscopic features in the spleen, thymus, and bursa of different duck breeds. The closer the points were to each other, the higher the relationship was. The points that are separate and far away considered outliers and were less frequent. (b) The HCA factor map of the microscopic lesions which were clustered into three clusters, in relation to the age and breed of the examined ducks.

Figure 8.

MCA and HCA of microscopic lesions in relation to the age and breed of NGPV-infected ducks. (a) The MCA plot revealed the relationship between the age and the recorded microscopic features in the spleen, thymus, and bursa of different duck breeds. The closer the points were to each other, the higher the relationship was. The points that are separate and far away considered outliers and were less frequent. (b) The HCA factor map of the microscopic lesions which were clustered into three clusters, in relation to the age and breed of the examined ducks.

Figure 9.

Bootstrap phylogenetic tree based on sequence alignment of whole genome sequences of NGPVs. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap percentages obtained using 500 replicates. Circles refer to NGPV strains determined in this study, while triangle shape refers to classical GPV B strain.

Figure 9.

Bootstrap phylogenetic tree based on sequence alignment of whole genome sequences of NGPVs. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap percentages obtained using 500 replicates. Circles refer to NGPV strains determined in this study, while triangle shape refers to classical GPV B strain.

Figure 10.

Bootstrap phylogenetic tree based on NS sequence alignment of NGPVs. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap percentages obtained using 500 replicates. Circles refer to NGPV strains determined in this study, while triangle shape refers to classical GPV B strain.

Figure 10.

Bootstrap phylogenetic tree based on NS sequence alignment of NGPVs. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap percentages obtained using 500 replicates. Circles refer to NGPV strains determined in this study, while triangle shape refers to classical GPV B strain.

Figure 11.

Bootstrap phylogenetic tree based on VP sequence alignment of NGPVs. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap percentages obtained using 500 replicates. Circles refer to NGPV strains determined in this study, while triangle shape refers to classical GPV B strain.

Figure 11.

Bootstrap phylogenetic tree based on VP sequence alignment of NGPVs. Numbers on the branches indicate bootstrap percentages obtained using 500 replicates. Circles refer to NGPV strains determined in this study, while triangle shape refers to classical GPV B strain.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and probe used in current study.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and probe used in current study.

PCR

Type |

Target protein |

Primer name |

Sequence |

PCR bp |

Reference |

Conventional

PCR |

NS gene of MDPV and GPV |

MDPV-F1 |

5′-GATGAATGCTGTAGTGCAGGAGGA-3 |

549

|

[25] |

| GPV-F1 |

5′- TTTGGCHGCCCCTTTACCTGATCC-3 |

| MGPV-R |

5′- ATTTTTCCCTCCTCCCACCA-3′ |

TaqMan Real-time

PCR |

NS gene of GPV and NGPV |

GPV-qF |

5-TAGGGAGGAGTTAGAAGA-3′ |

-

|

[28] |

| GPV-qR |

5′-TACTTATGACAATTCTATGGATG-3′ |

| GPV-qP |

FAM-5′- ACCTGGTAATTGTTCYTGCTTCTCT-3′-Eclipse |

Table 2.

Conventional and TaqMan real-time PCR findings.

Table 2.

Conventional and TaqMan real-time PCR findings.

| PCR type |

Breed |

Total Sample No/breed |

Organ of detection |

No of samples/organ |

NGPV-Positive/organ |

Total NGPV-Positive/breed |

NGPV-Negative/organ |

TaqMan

Real-time PCR |

Pekin |

45 |

Bursa |

15 |

14 |

33 |

1 |

| Thymus |

15 |

9 |

6 |

| Spleen |

15 |

10 |

5 |

Mule |

3 |

Bursa |

1 |

1 |

2 |

− |

| Thymus |

1 |

1 |

− |

| Spleen |

1 |

− |

1 |

Conventional

PCR |

Muscovy |

21 |

Bursa |

7 |

2 |

9 |

5 |

| Thymus |

7 |

3 |

4 |

| Spleen |

7 |

4 |

3 |

Native |

6 |

Bursa |

2 |

2 |

5 |

− |

| Thymus |

2 |

2 |

− |

| Spleen |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| Total |

- |

75 |

- |

75 |

49 |

49 |

26 |

Table 3.

Genome annotation, the nucleotide identity of classical GPV B strain with the three Egyptian NGPVs, and the nucleotide identity of the VP sequences of Egyptian NGPVs with the VP sequences of European Vaccinal strains currently used in Egypt.

Table 3.

Genome annotation, the nucleotide identity of classical GPV B strain with the three Egyptian NGPVs, and the nucleotide identity of the VP sequences of Egyptian NGPVs with the VP sequences of European Vaccinal strains currently used in Egypt.

Sequence_ID |

Whole genome length

(bp) |

Replication protein

(NS) |

Capsid protein

(VP) |

Nucleotide identity with#break#classical GPV B strain |

VP sequence of

LB strain |

VP sequence of Hoekstra strain |

Whole

length (bp) |

Start

site (bp) |

End

site (bp) |

Whole

length (bp) |

Start

site (bp) |

End

site (bp) |

Whole

genome level |

NS

level |

VP

level

|

VP1/VP2 |

VP3 |

VP1/VP2

|

VP3 |

| GPV-EgyArmy-ZU-202-2022 |

5107 |

1884 |

537 |

2420 |

2199 |

2439 |

4637 |

96.28% |

96.92% |

96.59% |

96.16% |

96.97% |

98.65% |

98.99% |

| GPV-EgyArmy-ZU-239-2022 |

5106 |

1884 |

538 |

2421 |

2199 |

2440 |

4638 |

96.18% |

96.76% |

96.45% |

96.61% |

96.97% |

94.58% |

98.99% |

| GPV-EgyArmy-ZU-274-2022 |

5101 |

1884 |

538 |

2421 |

2199 |

2440 |

4638 |

96.20% |

96.82% |

96.50% |

96.61% |

96.97% |

94.58% |

98.99% |