1. Introduction

Although rice production in Europe may be considered low, its use has an important socio-cultural value. So much so that some Mediterranean countries have developed world-famous dishes based on rice. This is the case of

risotto in Italy or

paella in Spain.

japonica rice varieties are used to prepare these dishes. They have a lower amylose content than

indica rice varieties, which contributes to their unique cooking and sensory properties. [

1]. In the preparation of

paella, pearled (white-core)

japonica rice cultivars are employed due to their capacity to withstand cooking and absorb flavors. [

2]. The

Bomba cultivar is the preferred variety for this dish due to its medium amylose content (18%). However, this cultivar has a low-yielding variety, which results in a higher cost. Consequently, other varieties with a lower amylose content (14%) are utilized. Another important factor to consider is the stickiness of the cooked grain. This factor appears to be increased when using low-amylose varieties. In addition to selecting the most suitable cultivars, these can be enhanced through the use of specialized soaking techniques or high-pressure applications, which can elevate their culinary and cooking qualities. [

3]

Furthermore, high-pressure processing (HPP) treatments modify the gelatinization process of rice grains, enhancing the integrity of starch granules [

4], delaying starch retrogradation, which causes texture deterioration during storage [

5], and elevating the degree of grain gelatinization. [

6]. Nevertheless, research has demonstrated that the outcomes anticipated from the implementation of HPP are contingent upon the specific rice variety, particularly its amylose content. The impact of HPP on waxy (non-pearled) and

indica rice varieties with elevated amylose content has been extensively investigated. This encompasses the phenomenon of starch retrogradation [

4,

5], wherein discernible variations were observed contingent on the leached amylose content. Additionally, alterations in solvent retention capacity exhibited notable distinctions between floury and waxy rice varieties. [

7].

Although a great deal of work has been done on the effect of HPP on the degree of gelatinization of rice flour, there are few cases where treatment has been carried out on whole grain. In these cases, it has been observed that the intensity of treatment on the degree of gelatinization depends very much on the variety of grain. So, in the case of the

japonica BChunyou 84 ([

8]., 2016), it was reported that a treatment of 400 MPa for 10 minutes was sufficient to achieve total gelatinization while for varieties such as

jasmine indigo the treatments to be applied were almost 600 MPa for 20 minutes [

9].

The hypothesis of this study is that a japonica variety with an amylose content similar to or slightly higher than that of Bomba may have good cooking textural characteristics which can be improved by treatment with HPP. Therefore, the objective was to evaluate the textural characteristics of Nuovo Maratelli rice cooked by two methods (boiling and microwave) for the impact of HPP pretreatment (400 and 600 MPa for 10 min).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and experimental design

A medium-grain japonica rice cultivar (Nuovo Maratelli) was selected for the present study. Samples were supplied by a local company (Producción Arroz Navarra S.L, Arguedas, Spain) and were stored at ambient temperature and dark until use.

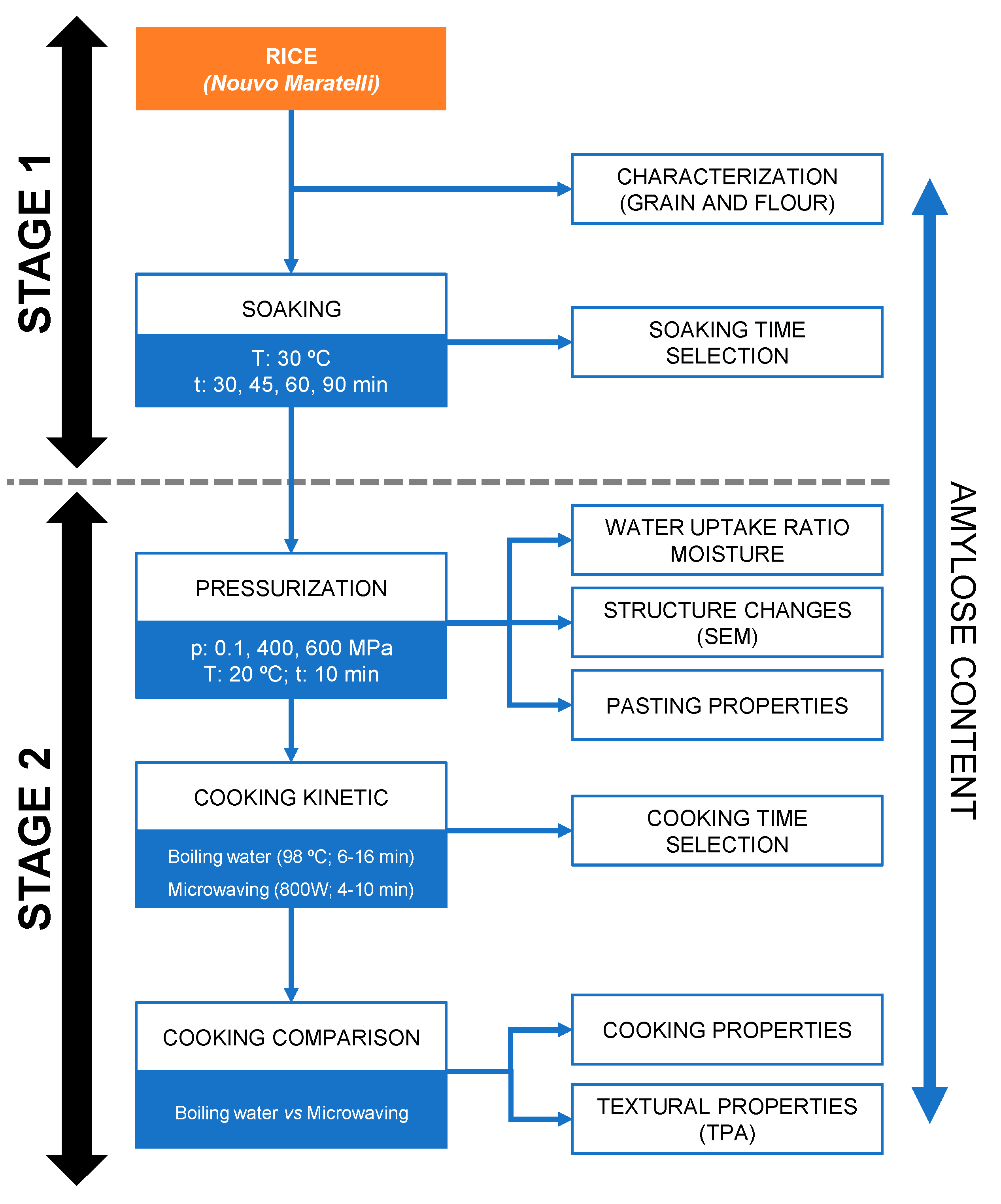

A two-stage approach was used to fulfill the research objectives. Firstly, the optimal hydration level of the rice grain was determined by examining the soaking time. Secondly, the impact of HPP pretreatment on the rice and on the texture and cooking properties of microwave and boil cooked rice was assessed (

Figure 1).

2.2. Soaking time and water uptake ratio

The optimal soaking time for achieving the appropriate grain moisture was determined through the method of Rattanamechaiskul et al. [

10], with some modifications. The samples (100 g of grain rice and 500 g of water) were placed into a polyamide/polyethylene 20/70 plastic bag, and soaked at 30 °C for 30, 45, 60, and 90 min. The samples were then air-dried for 2 min and weighed. The water uptake ratio of the rice samples (soaked and pressurized) was obtained by dividing the weight of the soaked rice by the initial weight. Once the samples reached steady state, the optimal soaking time was established. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

2.3. High-hydrostatic pressure treatment

A high-pressure unit Idus machine of 10 L vessel capacity and 800 MPa of maximum pressure (Idus HPP Systems S.L.U., Noain, Spain) was employed for all the experimental assays. Samples of 100 g of rice and 500 mL of osmotized water were placed in a PA/PE 20/70 plastic bag and soaked at 30 °C for the time selected in section 2.2. The samples were introduced in the HPP equipment at 25 ± 4 °C and two different levels of pressure were applied, 400 and 600 MPa, for 10 min in both cases. The 10 min treatment time did not include any come-up or depressurization times. The pressure-transmitting medium was water, pressurization rate was 600 MPa/min, and the depressurization was almost instantly. The product temperature was registered during processing with a pressure resistant data logger (LDT200 and Pt-100 thermometer, Leyro Instruments, Barcelona, Spain; Tempmate®-B5 data button, Heilbronn, Germany). The collected data set included both pressure and temperature readings. After treatment, the water was removed, and they were left to air dry for 2 min before stored 1 day maximum until further analysis.

2.4. Chemical analysis

The moisture content was estimated following the reference method [

11]. For amylose determination, soaked and cooked rice samples were first dried at 40 °C to reduce moisture up to 6 – 12%. Treated and raw samples were ground for 1 min with an electric grinder (Moulinette, Moulinex, Barcelona, Spain) and passed through a 150-µm sieve to ensure homogeneous particle size.

The apparent amylose content (AAC) was quantified using the method suggested by Juliano et al. [

12]. A standard curve for the estimation of AAC (10 to 40 mg/100 mL of potato amylose) was used and the absorbance was measured at 720 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). The AAC of rice samples were expressed as mg/100 g dry matter (DM).

2.5. Microstructure by Scanning Electron Microscopy

Changes in microstructure of pressurized rice samples were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging, according to the method described by Xu et al. [

13]. Freeze-dried rice grain samples were mounted onto a SEM plate using conductive carbon tabs, and Pt-coated by sputtering of 7 nm. The three-dimensional network microstructure of the rice grain samples was then observed and photographed using a JSM-5610-LV scanning electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at a 20-kV acceleration voltage. For image analysis, the Fiji software package, a distribution of ImageJ2 v.1.54f image analysis software, was used on the Java 8 platform [

14]. Particle circularity was quantified by the method of Jordan et al. [

15]. A circularity value of 1 is indicative of a perfect circle, while a value close to zero (0) suggests an elongated shape.

2.6. Pasting properties

Flour samples (about 10% of moisture) were prepared as for the AAC determination (section 2.3). Pasting properties of the rice flours were evaluated in a rotational Rheometer HAAKE RotoVisco 1 (Thermo Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a cup Z43S and a starch blade FL2B paddle-shaped rotor with 2 blades using the method described by Kaur et al. [

16] with slightly modifications. Heating and cooling cycles were programmed. Each rice flour suspension (6 g/50 g) was held at 50 °C for 6 min, heated to 95 °C at 2.25 °C/min, held at 95 °C for 400 s, before cooling from 95 to 50 °C at 3 °C/min. The rotating speed of the paddle was set at 160 rpm during the measurements except of 960 rpm at the first 10 s. Device management and data acquisition were performed using HAAKE RheoWin 4 software (Thermo Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany). Outputs were expressed as Pa·s.

2.7. Cooking kinetics and cooking time selection

To obtain the rice cooking kinetics by boiling, 100 g of rice were submerged in 500 mL of deionized water in a beaker and boiled (98 ± 1 °C) using a heating plate (Combiplac, JP Selecta, Barcelona, Spain). Subsamples of 15 g of rice were taken at two-minute intervals between minutes 6 and 14 placed on qualitative filter paper for 5 min. This process allowed the removal of surface moisture from the rice grains.

For microwave cooking kinetics, 60 g of raw rice was mixed with 300 mL of distilled water using a domestic microwave oven (Taurus Luxus Grill 21 L, Taurus Group, Oliana, Spain) at 800 W. At 2-minute intervals between 2 and 10 min, 5 g samples of rice were collected for analysis and placed on filter paper, as previously described. In order to ascertain the cooking time and textural properties for both, the boiling and microwave cooking methods, an instrumental analysis of the texture and a visual analysis were employed. Each time sample was submitted to the texture profile analysis (TPA) described in 2.9 section. Additionally, two grains of rice placed between two plates were crushed using a 5 kg weight load. The grains were analyzed under a magnifying glass and the rice was identified as cooked when approximately less than 10% of the grains show an opaque center. [

17]

2.8. Cooking properties

Once the cooking time was determined for each cooking method, samples of cooked rice were prepared in accordance with the method outlined in section 2.7, and the resulting cooked rice is evaluated in terms of its cooking properties. Cooking properties such as elongation ratio, gruel solid loss, water uptake ratio and expansion volume were quantified according to methods described by Bhattacharya [

18].

2.9. Instrumental analysis of texture profile

The texture analyzer TA-XT Plus (Stable Micro System Ltd., Surrey, UK), with 50 kg load cell, fitted to an aluminum compression platen (75mm Ø, code P/75) and controlled with the Exponent Lite v.6.1. software (Stable Micro Systems Ltd., Surrey, UK) was used. A double compression test was programmed for texture profile analysis (TPA). A rice sample of 2 g (room temperature) was placed carefully on the base platform, under the center of probe, and was 90% compressed at test rate of 1 mm/s. Pre-test and post-test rates were 5 mm/s. The analyzer calibration was conducted using a weight of 1 kg. Parameters such as hardness (N), adhesiveness (N s), cohesiveness, resilience (%); springiness (%), gumminess (N), and chewiness (N) were obtained applying the method described by Lyon et al [

19]. TPA tests were performed in triplicate.

2.10. Statistical analysis

A one-way ANOVA was applied to physicochemical parameters of samples. The Tukey test was used for multiple comparison (95% significance level) when differences between means were detected by ANOVA. The textural properties that were most affected by the dual treatments (pressurization and cooking) applied to the rice in stage 2 were determined through a discriminant analysis. Statistical assessment of the data was achieved using the SPSS Statistics for Windows, vers. 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. HPP processing

The pressure-time relation and the internal temperature of the sample recorded during rice HPP processing at 400 and 600 MPa are shown in

Figure S1. The temperature of the filling water ranged from 25 to 30 °C during the treatments. The temperature of the product has never exceeded 32 °C, with thermal leaps in the range of 8 to 10 °C. This means and ensures that the pressure treatment has not caused any heat-induced structural changes in the rice and starch and that any change in the properties, characteristics and behavior of the samples should be attributed to the pressure.

3.2. Raw grain characterization and water uptake

The raw samples of

Nuovo Maratelli rice have a length of 6.1 ± 0.4 mm and a length/width ratio of 2.12 ± 0.19 and belong to the medium grain classification [

20].

The moisture content of

Nuovo Maratelli samples was found to be 11.78 ± 0.53%, with an AAC of 22.61 ± 0.83% (25.31 ± 0.93 mg/100 g DM). Based on these findings, the samples can be classified as intermediate amylose rice [

21]. Commonly, amylose content was related positively with hardness and negatively with stickiness, so cooked-rice hardness and stickiness were very highly inversely correlated [

22]. Although this

japonica rice cultivar with intermediate content of amylose could be used to prepare

paella, as HPP could reduce firmness and stickiness, the application of this technology could be of special interest to improve eating quality.

The soaking time at 30 °C to reach the minimum recommended moisture content (from 25 to 35%) was determined to be 45 min.

3.3. Effect of pressurization on water uptake ratio

The water uptake ratio in the soaked and pressurized samples were 1.27 ± 0.00, 1.33 ± 0.02 and 1.69 ± 0.01 g treated/g initial rice for 0.1, 400 and 600 MPa, respectively. In consequence, when comparing atmospheric pressure soaking to HPP soaking, the moisture content (g water /100 g) of normal rice grain significantly rose from 39.5 ± 0.45 (unpressurized samples) to 42.13 ± 0.17 (400 MPa) and 39.07 ± 1.51 (600 MPa). This is in accordance with the results described by Wu et al. [

23], that found water absorption rates around 1.28 g/100 g in

Wuchang cultivar, a non-waxy rice after 400 MPa soaking for 15 min. The rise in moisture levels indicated that water molecules could effectively penetrate the peripheral regions of starch granules in rice grains under conditions of HPP [

24]. The increase in weight with raising pressure level did not correlate with a corresponding increase in moisture content. These findings suggest that solids retention was greater in samples subjected to 600 MPa, which is attributable to gelatinization processes that take place at these pressures. [

25,

26].

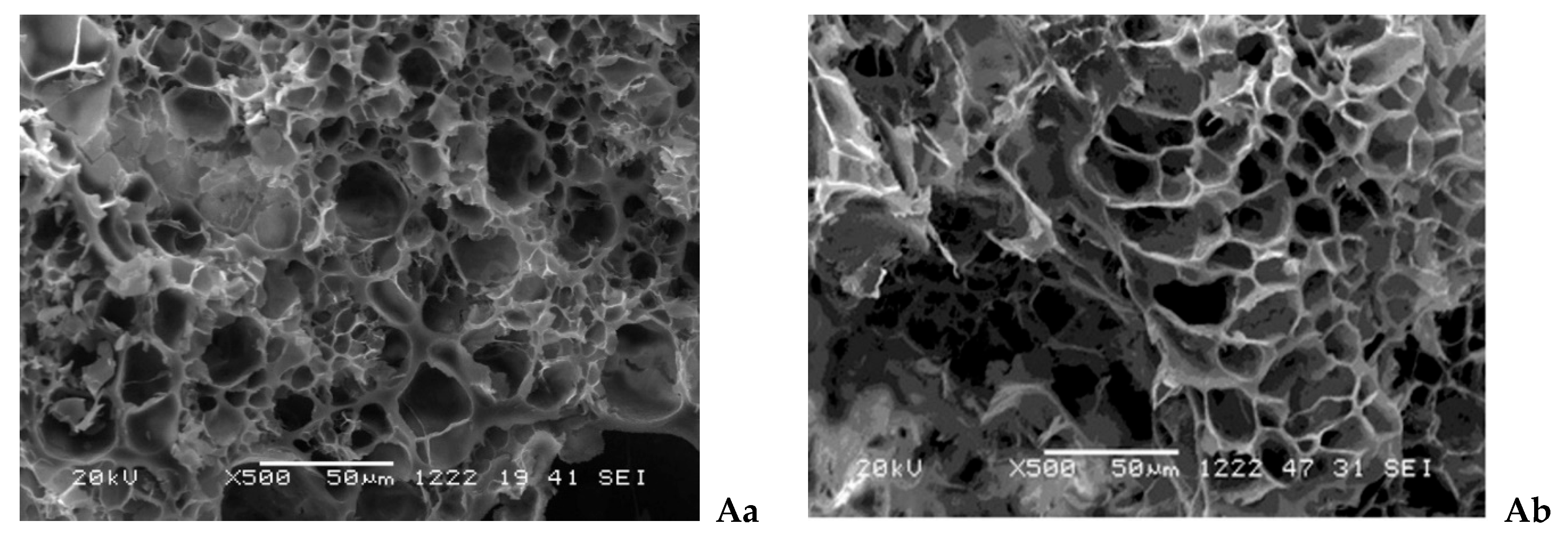

3.4. Effect of pressurization on rice grain microstructure

Figure 2 depicts the alterations in rice grain microstructure according to pressure treatments, as observed through SEM. The microstructure of rice grains was affected by HPP treatment. Moderate pressurization (400 MPa, 10 min) enhanced hydration of starch granules, making the cavities more homogenous (

Figure 2 Aa y Ab). The characteristic polyhedral forms of the starch of the raw rice grain (

Figure 2 Ba) begin to be lost after the application of an intermediate HPP treatment (

Figure 2 Bb) and when gelatinization occurs at certain pressures, there is a reorganization of microstructure due to partial aggregation, compaction (

Figure 2 Bc). The intermediate amount of amylose could contribute to stabilize the granules and prevents them from disintegrating as was found by Hu et al. [

4] in non-waxy starch granules that retain their integrity, a difference to waxy starch granules that lose it after HPP at 600 MPa. Cappa et al. [

27] also reported this phenomenon in different rice flour samples treated at 600 MPa.

3.5. Effect of pressurization on pasting properties of rice flours

The pasting properties of rice starch are influenced by granule swelling, amylose leaching, starch crystallinity, amylose content, and branch chain-length distribution of amylopectin. The increase in viscosity with rising temperature can be attributed to the removal of water from the exuded amylose by the granules as they undergo swelling [

28]. Rice with a high-intermediate amylose content typically exhibits elevated values for pasting temperature (PT), peak viscosity (PV), minimum viscosity (MV) and final viscosity (FV). Additionally, it displays a low breakdown index (BI), indicating stability during the cooking process and a high setback, which means that it retrogrades easily [

29,

30].

The results of the assays with the

Nouvo Maratelli rice showed no differences in any of the pasting properties in all the control and HPP treated samples. However, a tendency towards a reduction in BI was detected in the HPP treated rice. Lower values of BI were also detected following pressurization (120 to 600 MPa for 30 min and 400 MPa for 10 min) in starch rice [

31] and medium or high amylose rice flour [

30], respectively. The decrease of BI in HPP treated samples resulted in more stable samples during cooking. Similarly, the HPP treated samples exhibited a tendency to increase PV and MV at 400 MPa and to decrease these pasting parameters to 600 MPa in comparison to the control (

Table 1). These results are aligned with those previously reported by Li et al. [

31], who applied pressures of 120 – 600 MPa to rice starch.

Modifications were observed in the microstructure of the starch granule at 400 MPa (

Figure 2), being this pressure the threshold for rice grain gelatinization for the

japonica cultivar

Chunyou 84 [

8]. All of this could explain the changes in the pasting properties of the 400 MPa pressurized sample compared to control. On the contrary, under 600 MPa the compaction and partial gelatinization of rice starch does not lead to changes in pasting properties respect to control.

In whole rice grains, the physicochemical modifications induced by HPP treatments which affect the pasting properties are less pronounced than in rice flour and rice starch, so the effect on the pasting properties is therefore more challenging to assess.

3.6. Cooking behavior: texture changes and time selection

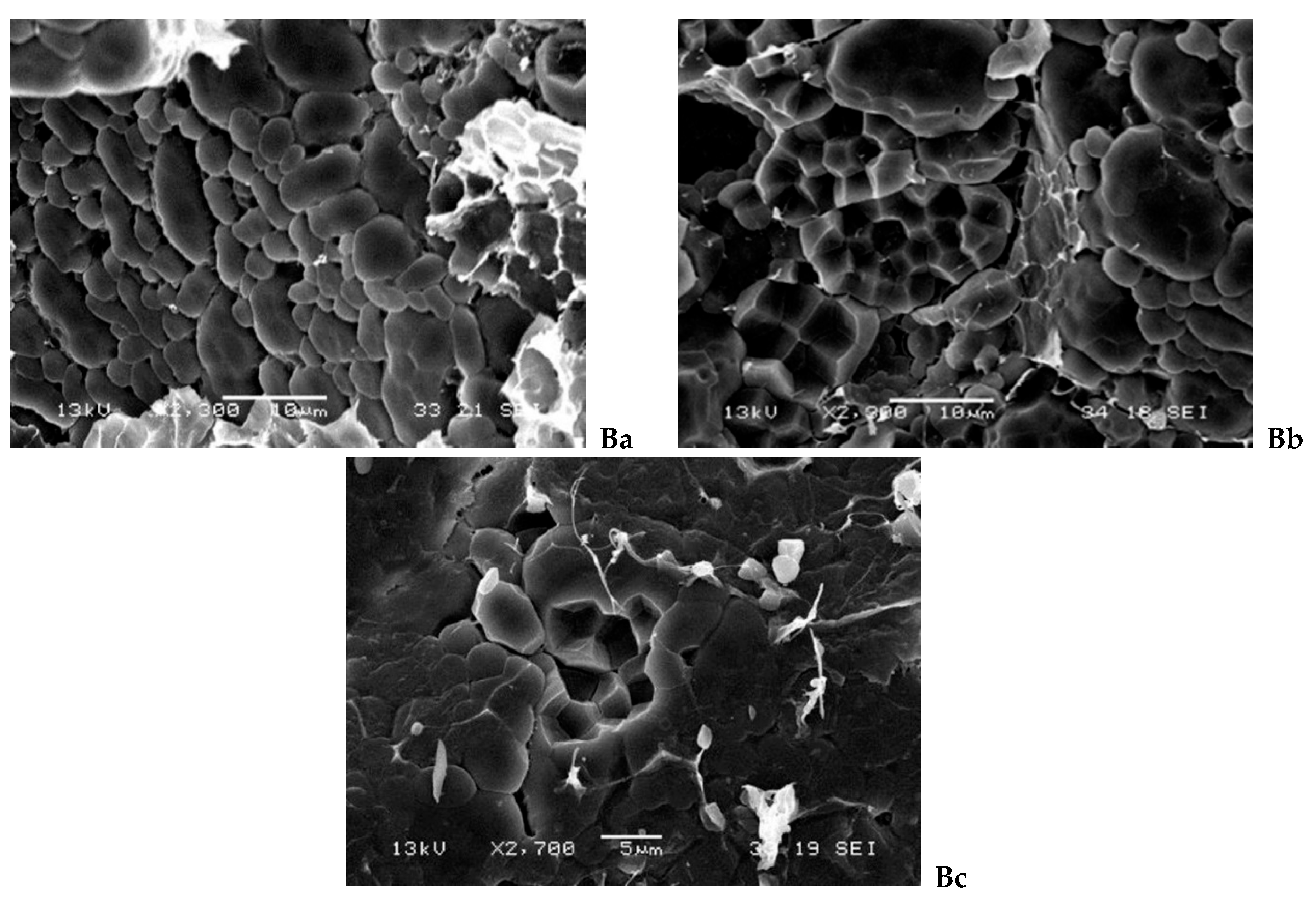

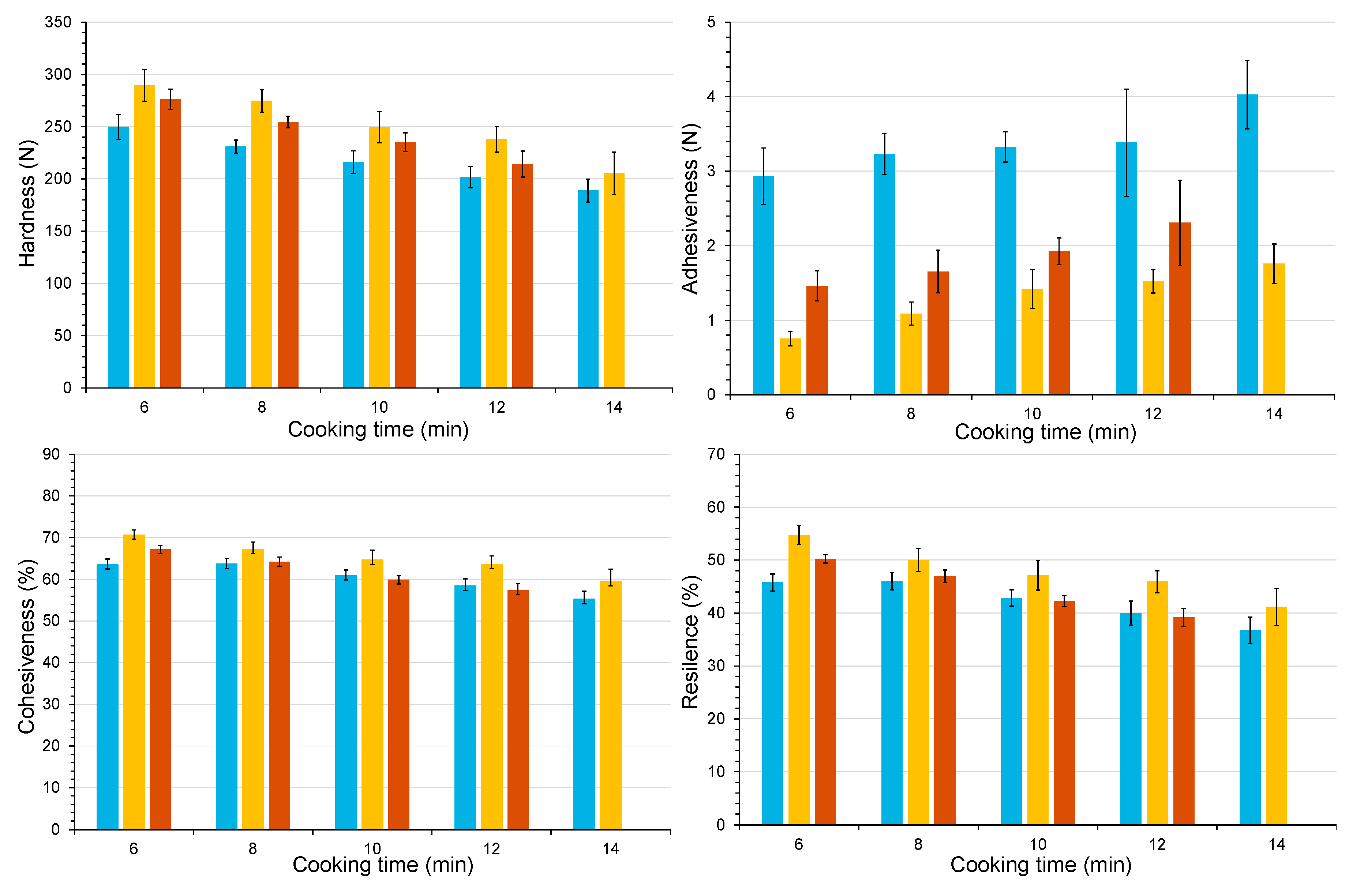

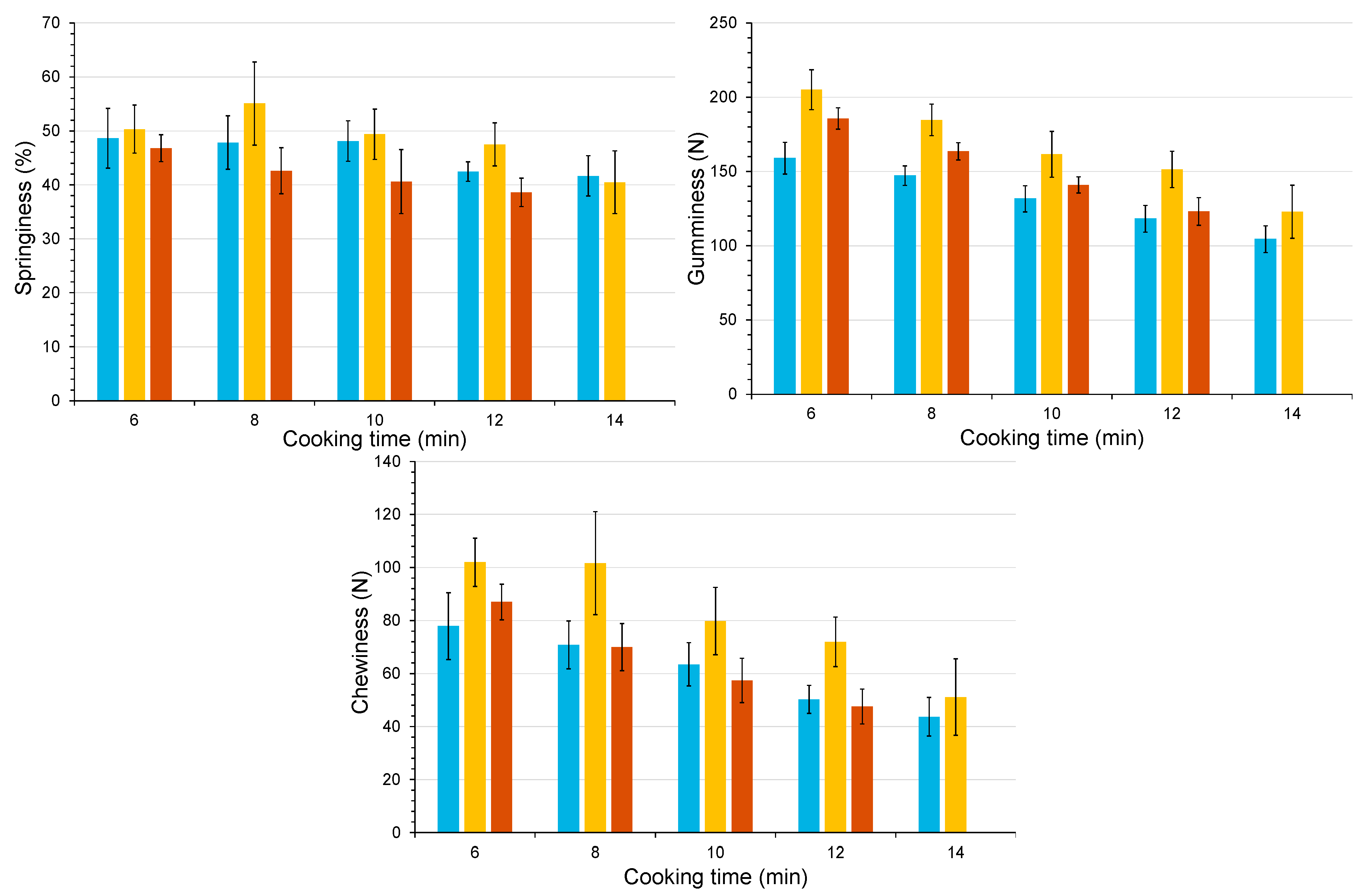

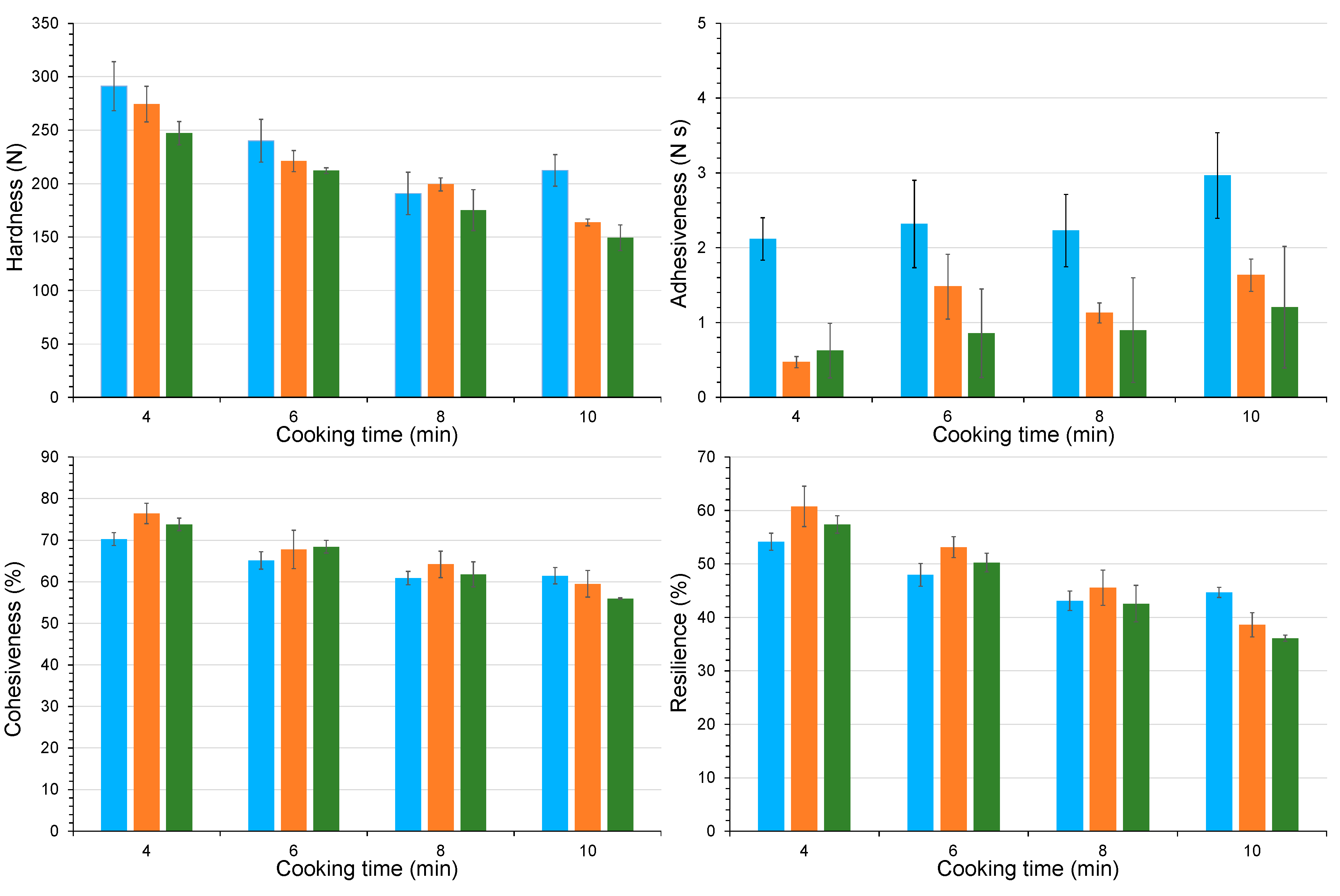

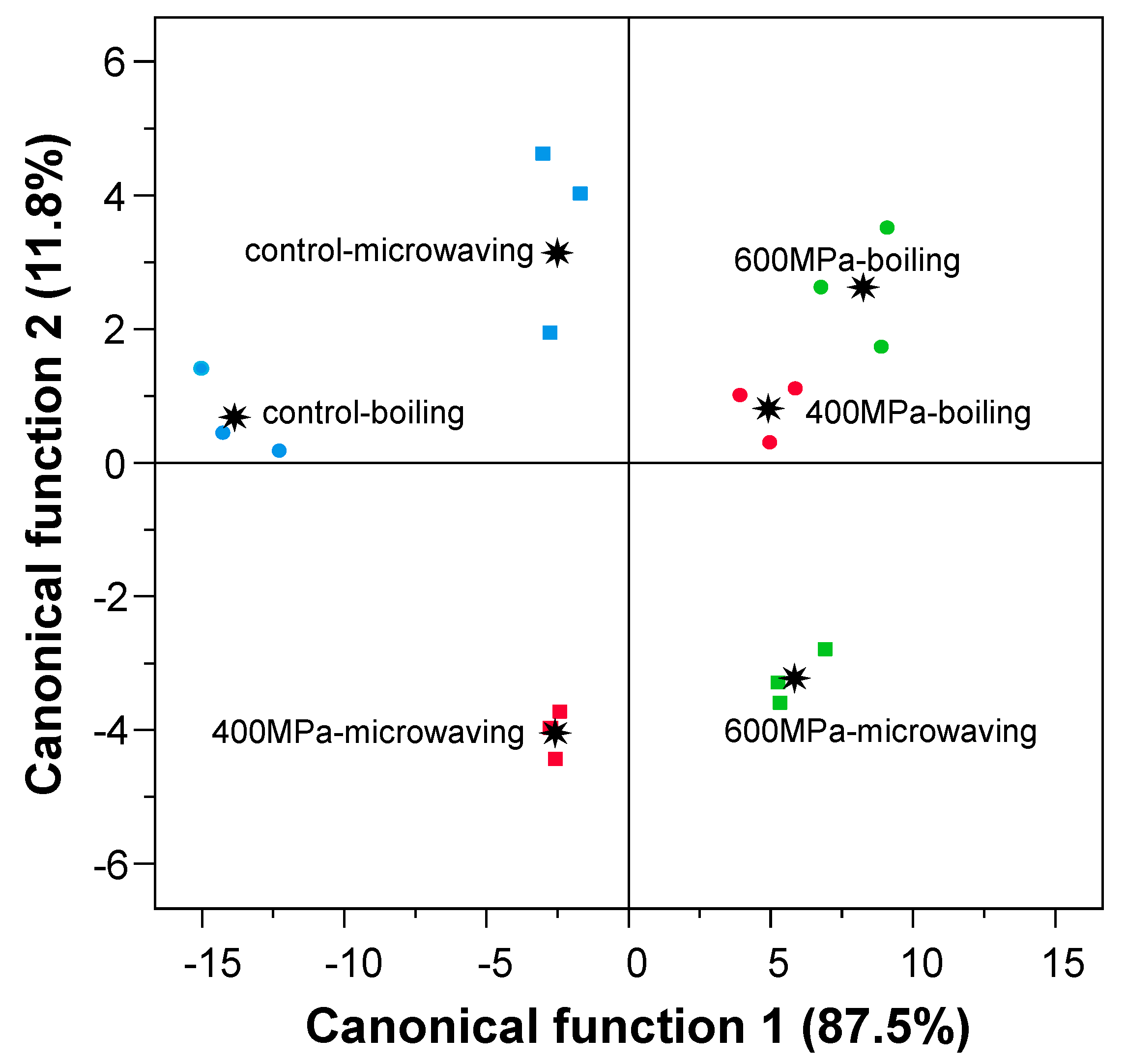

The changes in instrumental texture parameters as a function of time during boiling and microwave cooking are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Data for 600 MPa - boiled rice at 14 min are not included because the samples were overcooked and therefore not suitable for instrumental analysis. During cooking, all texture parameters decreased with time except for adhesiveness, which increased. Overall, HPP treatment increased the cohesiveness and reduced the adhesiveness of the rice grains irrespective of the cooking method. However, the results of the texture kinetics showed that the effect of the other texture parameters depended on the cooking method applied. These effects were generally more pronounced in the 400 MPa than in the 600 MPa treated samples.

Compared to the unpressurized samples, the HPP ones showed a notable reduction in adhesiveness. In addition to changes in the amylose content in the cooked samples, which is negatively related to the stickiness, the structure of the starch affects this parameter [

22], so the changes in adhesiveness could be explained by changes in the rice starch during pressurization. As the instrumentally measured adhesiveness is indicative of the stickiness between the rice grain and the TPA probe, it can be deduced that the leached materials (amylose) from the cooking process are a determining factor in the stickiness between the rice grains.

When boil cooking as applied (

Figure 3), the pressurized samples had higher values for hardness, cohesiveness, chewiness, gumminess and resilience than their non-pressurized counterparts at the same cooking time, especially when 400 MPa was used. In microwave cooked samples, in contrast to boil cooked samples, HPP pretreatment reduced the hardness. The more uniform structure shown in 400 MPa pressurized rice than in control (

Figure 2 Aa and Ab) could be responsible for these changes. Tian et al. [

24] also observed a more homogeneous network structure, resulting in lower hardness when normal and waxy rice were soaked under 400 MPa. In addition, the cooked rice also had smaller holes, and a more resistant granule structure. Yu et al. [

5] also reported that the hardness of HPP brown rice was reduced under pressure of 300 MPa for 10 min.

The visual evaluations for each rice sample led to the determination of cooking times, which are presented in

Table 2. In this study, the cooking time was a prerequisite for evaluating the texture of the cooked rice. The cooking time for the unpressurized boiled samples was 14 ± 0 min, a relatively high value for a soaked sample, which is related to its intermediate AAC and the shape of the grains.

The cooking time was reduced when a pretreatment of 400 or 600 MPa was applied prior to cooking compared to the unpressurized samples. According to Priestley [

32], fast cooking rice is directly related to the water absorbed in the previous soaking. Since HPP favors water uptake through diffusion, it is expected that cooking time will be reduced. Thus, the application of intermediate pressures (around 400 MPa) induces starch gelatinization and may reduce cooking time by facilitating water diffusion into the rice grain [

33,

34]. In addition, when the pressure treatment is increased to 600 MPa, rice grain gelatinization occurs depending on the degree of the milling and/or treatment time [

8], thus reducing cooking time.

3.7. Effect of HPP pretreatment on cooking properties

The cooking properties of the raw rice samples (boiled and microwave cooked) and those treated with HPP are shown in

Table 2. The soaking and pressurization processes caused water to penetrate the grain, increasing the moisture content of the soaked rice grains pressurized to 400 – 600 MPa, as indicated in section 3.1. This pretreatment facilitates subsequent cooking by reducing cooking time, water uptake and changes in grain physical dimensions. In addition, the cooking properties and impact of the HPP treatment differ depending on the cooking method. Thus, shorter cooking times are required for microwave cooking, although the application of the higher pressures reduces the difference between both methods. The partial gelatinization of starch by pressure at 600 MPa could explain this phenomenon.

As water uptake was produced during HPP and cooking time was reduced, lower ratios of this parameter were detected in the treated samples, especially at the higher pressure. Water absorption facilitates the incorporation of flavors into rice dishes, which is a crucial aspect from a culinary point of view. Similarly, the grain elongation ratio and the volume expansion after cooking in the HPP-treated samples are consequently smaller than those observed in the cooked non-pressurized samples. Furthermore, a lower final moisture content of the HPP cooked samples was found, as already found in the uncooked pressurized samples, especially when cooked in the microwave. The physical changes of the grain dimension during cooking are less pronounced at 600 MPa than at 400 MPa, probably due to a shorter cooking time and a partial pressure gelatinization before heat cooking. The compressibility of starch suspensions under pressure showed a reduction in total volume associated with gelatinization [

35].

Furthermore, the effect of HPP treatments on the gruel solids loss differs depending on the cooking method. Microwave cooking increased the gruel solids loss, whereas boiling had no effect.

In terms of cooking properties, boiled rice showed superior convenience and quality compared to microwaved rice, which showed lower values for cooking properties, regardless of the pressure applied.

3.8. Effect of HPP pretreatment on textural properties

The outputs of the instrumental texture evaluation for boil and microwave cooked rice grain are summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively. The statistical analysis revealed that all parameters were significantly different between the unpressurized and pressurized samples, except for springiness (boil and microwave cooking), and for gumminess (microwave cooking).

The effect of pressurization on hardness differs depending on cooking method, as observed in the cooking kinetics (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). In unpressurized samples, the hardness of microwave cooked samples was higher than boil cooked ones. The lower cooking time and higher amylose leaching during cooking in microwave cooked samples could explain this result. The increase in hardness could be attributed to the amylose forming a film that coats the rice grains [

36].

Boil cooked pressurized samples displayed a higher hardness than control ones, while microwave cooked ones showed a reduced hardness, to a more extent at 400 MPa pressure. A reduction in hardness was found for normal, waxy and black rice treated up to 400 MPa [

24,

37]. Boluda-Aguilar et al. [

9] also found a decrease in instrumental hardness of

Jasmine rice (an

indica cultivar) heated by microwave in samples subjected to moderate HPP treatments (300 – 400 MPa for 2 – 3 min) relative to untreated samples. The lower hardness in pressurized samples cooked by microwave could be explained by a less amylose leaching than in control during cooking.

The pressurized samples showed higher cohesiveness and chewiness, but lower adhesiveness than the unpressurized ones irrespective of cooking method.

The increase in cohesiveness and chewiness depends on the cooking method. In the case of boiling, the effect was detected for any pressure. However, in the case of microwave cooking, a pressure of up to 600 MPa is required to observe changes in this parameter. A more compact network might be formed in rice under the high pressure that increases cohesiveness [

24,

37]. HPP treatment can also cause the starch granules to be more firmly bound to the protein, thus decreasing the hardness of the rice and improving the chewiness [

23].

Pressurization reduces rice adhesiveness in samples cooked with both methods. The application of HPP treatment shortened the cooking time and modified grain microstructure and starch granules, and thus, the grain adhesiveness was affected.

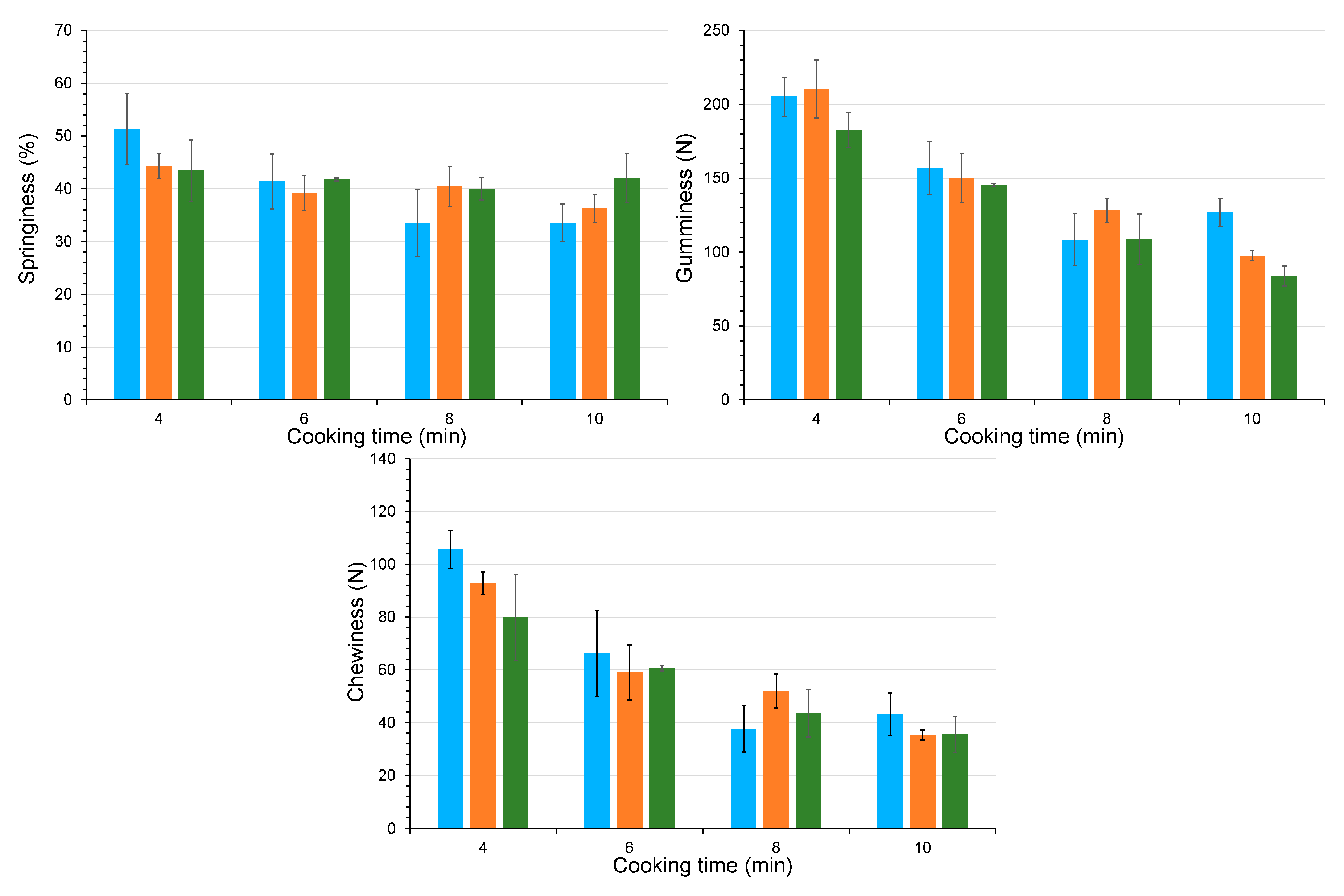

The discriminant analysis performed to the instrumental texture parameters yielded two functions that collectively explained 99.2% of the sample variance. Discriminant function 1 (87.5%) was closely associated with hardness, gumminess and resiliency. Discriminant function 2 (11.8%) was strongly related to adhesiveness.

Figure 5 depicts the samples based on the two discriminant functions. Unpressurized samples (control) are shown in the first quadrant of the graph. Pressurized and boiled cooking samples are grouped in the second quadrant. Pressurized and microwaved cooking samples are collected in the remaining quadrants.

In comparison to the unpressurized and boil-cooked samples, the pressurized to 400 MPa and microwave-cooked samples showed comparable hardness values but had decreased adhesiveness. This finding suggests that microwave cooking had the greatest impact on the textural properties of pressurized samples, as hardness and stickiness are the key to improve and manage eating quality for rice [

22].

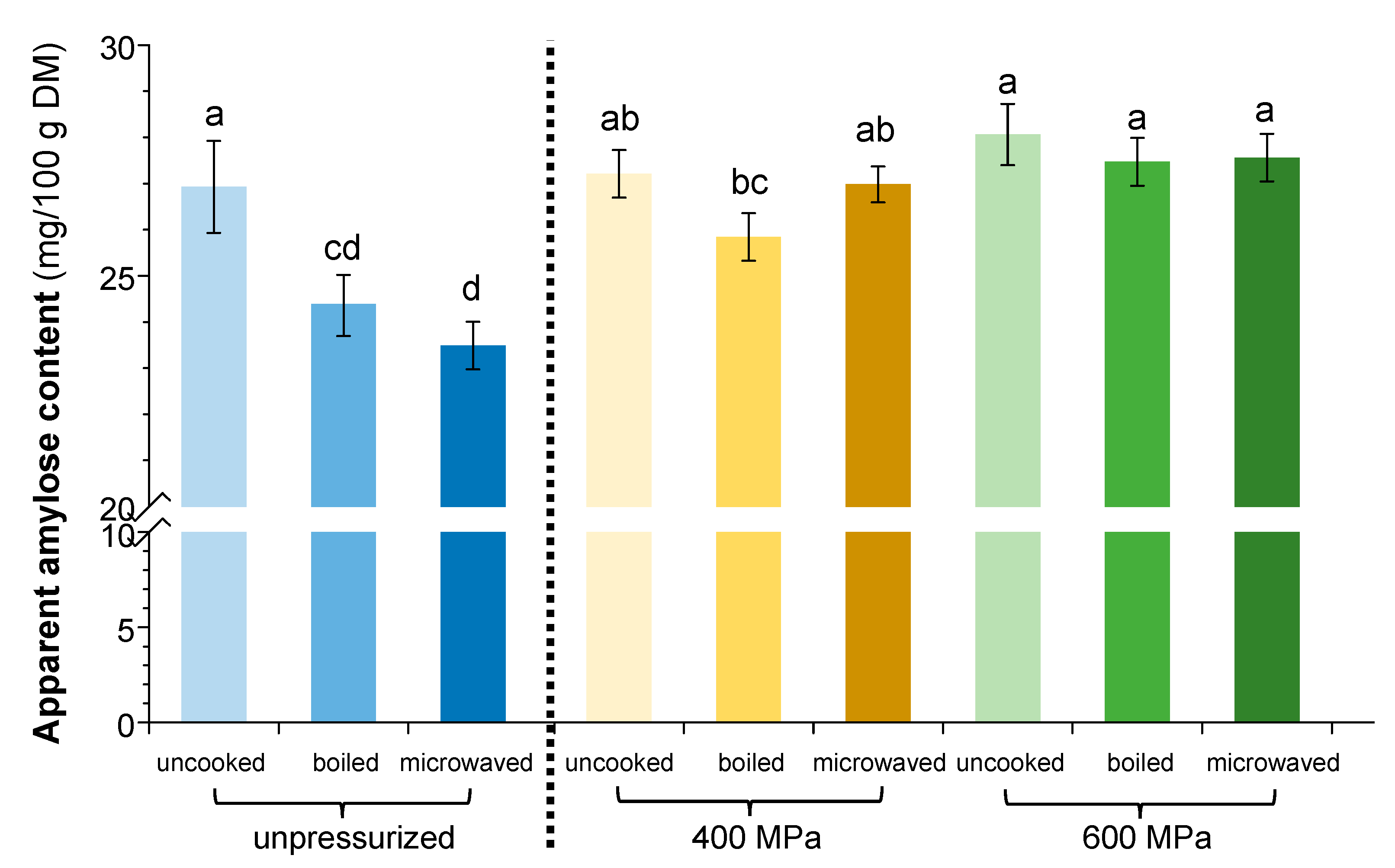

3.9. Effect of pressurizing and cooking on amylose content

Figure 6 shows the changes in the AAC of rice samples soaked and subjected to the different treatments (pressurization and cooking). The highest values were recorded in the samples pressurized at 600 MPa, regardless of the cooking type (27.47 – 28.06 mg/100 g DM). The samples treated at 400 MPa displayed intermediate values (25.84 – 27.21 mg/100 g DM). Instead, soaked and microwaved samples showed the lowest values (23.49 mg/100 g DM).

Regarding uncooked sample, the HPP treatment did not significantly impact the AAC. On the contrary, the cooked samples exhibited elevated AAC contents when subjected to HPP pretreatment, especially when microwave cooking was used and when the pressure applied was 600 MPa. Therefore, it can be concluded that pressurization would effectively reduce the leaching of amylose during the cooking process. These were also observed in pressurized normal and black rice grain [

4,

37], that was attributed to the intact starch granules presented in the HPP treatment, that difficult amylose leaching [

4].

4. Conclusions

This study evaluates, for the first time, the effect of HPP pretreatment on the properties of Nuevo Maratelli rice and prepared using two different cooking methods. Based on the results obtained, pretreatments at 400 and 600 MPa for 10 min could be used to modify the cooking properties of the rice. In particular, the HPP treatment reduces cooking times and improves some of the textural properties that are critical for the eating quality of this rice cultivar. However, the speed of cooking and the subsequent modifications depend on both the pressure level and the cooking method used. The application of the highest pressure level facilitates the incorporation of water into the grain, thereby increasing its availability and reducing the cooking time by up to 6 min when microwaved. Additionally, the HPP pretreatment causes changes in the grain microstructure, which are already observed at 400 MPa and become more pronounced at 600 MPa, when a compact network was formed because of the pressure gelatinization. Most of the textural parameters were modified as a result, but to improve the eating quality of the cooked rice, 400 MPa before microwave cooking could be selected as it achieves a similar hardness than to that of unpressurized boil cooked rice and reduces adhesiveness. The results obtained in this work suggest that a pretreatment of pressurization could improve the eating quality and convenience of Nuovo Maratelli rice to prepare traditional rice dishes such as paella.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V. and C.A.; methodology, M.J.N. and S.H..; formal analysis, F.C.I.; investigation, S.H. and I.F.P.; resources, S.H. and I.F.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.N. and CA.; writing—review and editing, I.F.P, S.H. and F.C.I..; supervision, P.V. and F.C.I.; funding acquisition, P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mefleh, M. Cereals of the Mediterranean region: their origin, breeding history and grain quality traits. In Cereal-Based Foodstuffs: The Backbone of Mediterranean Cuisine; Boukid, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-69228-5. [Google Scholar]

- Barea-Ramos, J.D.; Santos, J.P.; Lozano, J.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Montero-Fernández, I.; Martín-Vertedor, D. Detection of aroma profile in Spanish rice paella during socarrat formation by electronic nose and sensory panel. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Turner, M.S.; Fitzgerald, M.; Stokes, J.R.; Witt, T. Review of the effects of different processing technologies on cooked and convenience rice quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, X.; Jin, Z.; Tian, Y.; Bai, Y.; Xie, Z. Retrogradation properties of rice starch gelatinized by heat and high hydrostatic pressure (HHP). J. Food Eng. 2011, 106, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Pan, F.; Ramaswamy, H.S.; Zhu, S.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Q. Effect of soaking and single/two cycle high pressure treatment on water absorption, color, morphology and cooked texture of brown rice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Selomulyo, V.O.; Zhou, W. Effect of high pressure on some physicochemical properties of several native starches. J. Food Eng. 2008, 88, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Mulla, M.Z.; Arfat, Y.A.; Kumar, V. Effects of high-pressure treatment on functional, rheological, thermal and structural properties of Thai jasmine rice flour dispersion. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.M.; Hu, F.F.; Ramaswamy, H.S.; Yu, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Q.T. Effect of high pressure treatment and degree of milling on gelatinization and structural properties of brown rice. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2016, 9, 1844–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda-Aguilar, M.; Taboada-Rodríguez, A.; López-Gómez, A.; Marín-Iniesta, F.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Quick cooking rice by high hydrostatic pressure processing. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanamechaiskul, C.; Junka, N.; Prakotmak, P. Modeling and optimization of moisture diffusion of paddy and brown rice during thermal soaking. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO Cereals and Cereal Products — Determination of Moisture Content — Reference Method; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Juliano, B.O.; Perez, C.M.; Blakeney, A.B.; Castillo, T.; Kongseree, N.; Laignelet, B.; Lapis, E.T.; Murty, V.V.S.; Paule, C.M.; Webb, B.D. International cooperative testing on the amylose content of milled rice. Starch - Stärke 1981, 33, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yan, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Du, X. Effect of ultra-high pressure on quality characteristics of parboiled rice. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 87, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.C.; Dürig, T.; Cas, R.A.F.; Zimanowski, B. Processes controlling the shape of ash particles: Results of statistical IPA. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2014, 288, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Kaur, N.; Kaur, M.; Sandhu, K.S. Some properties of rice grains, flour and starches: A comparison of organic and conventional modes of farming. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 61, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, B.O.; Perez, C.M.; Barber, S.; Blakeney, A.B.; Iwasaki, T.A.; Shibuya, N.; Keneaster, K.K.; Chung, S.; Laignelet, B.; Launay, B.; et al. International cooperative comparison of instrument methods for cooked rice texture. J. Texture Stud. 1981, 12, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.R. Some selected rice quality test procedures. In Rice Quality. A Guide to Rice Properties and Analysis; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2011; pp. 531–562 ISBN 978-1-84569-485-2.

- Lyon, B.G.; Champagne, E.T.; Vinyard, B.T.; Windham, W.R. Sensory and instrumental relationships of texture of cooked rice from selected cultivars and postharvest handling practices. Cereal Chem. 2000, 77, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Council Regulation (EC) No 1234/2007 of 22 October 2007 Establishing a Common Organisation of Agricultural Markets and on Specific Provisions for Certain Agricultural Products; 2007; Vol. 299.

- Juliano, B.O. Structure, chemistry, and function of the rice grain and its fractions. Cereal Foods World 1992, 37, 772–779. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Gilbert, R.G. Starch molecular structure: The basis for an improved understanding of cooked rice texture. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 195, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; He, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Hui, A.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Effect of high-pressure pre-soaking on texture and retrogradation properties of parboiled rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 4201–4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Jin, Z. Effect of different pressure-soaking treatments on color, texture, morphology and retrogradation properties of cooked rice. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahromrit, A.; Ledward, D.A.; Niranjan, K. Kinetics of high pressure facilitated starch gelatinisation in Thai glutinous rice. J. Food Eng. 2007, 79, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-L.; Jao, C.-L.; Hsu, K.-C. Effects of hydrostatic pressure/heat combinations on water uptake and gelatinization characteristics of Japonica rice grains: a kinetic study. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, E442–E448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappa, C.; Lucisano, M.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Mariotti, M. Physical and structural changes induced by high pressure on corn starch, rice flour and waxy rice flour. Food Res. Int. 2016, 85, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Qiu, C.; Liao, Z.; Sui, Z.; Corke, H. Impact of cooking conditions on the properties of rice: Combined temperature and cooking time. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, K.; Yu, W.; Prakash, S.; Gilbert, R.G. Investigating cooked rice textural properties by instrumental measurements. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2020, 9, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakura, M.; Haraguchi, K.; Okadome, H.; Suzuki, K.; Tran, U.T.; Horigane, A.K.; Yoshida, M.; Homma, S.; Sasagawa, A.; Yamazaki, A.; et al. Effects of soaking and high-pressure treatment on the qualities of cooked rice. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2005, 52, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bai, Y.; Mousaa, S.A.S.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, Q. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure on physicochemical and structural properties of rice starch. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 2233–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, R.J. Moisture requirements for gelatinisation of rice. Starch - Stärke 1975, 27, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B.A.; Knorr, D. The impact of pressure, temperature and treatment time on starches: pressure-induced starch gelatinisation as pressure time temperature indicator for high hydrostatic pressure processing. J. Food Eng. 2005, 68, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.E.; Hemar, Y.; Anema, S.G.; Wong, M.; Neil Pinder, D. Effect of high-pressure treatment on normal rice and waxy rice starch-in-water suspensions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 73, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douzals, J.P.; Marechal, P.A.; Coquille, J.C.; Gervais, P. Microscopic study of starch gelatinization under high hydrostatic pressure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelayuthsoontorn, P.; Thipayarat, A. Textural and morphological changes of Jasmine rice under various elevated cooking conditions. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Z.; Hui, A.; Gao, H.; Chen, P.; He, Y. Effect of pressure-soaking treatments on texture and retrogradation properties of black rice. LWT 2018, 93, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Flow chart detailing the sequence of experimental procedures.

Figure 1.

Flow chart detailing the sequence of experimental procedures.

Figure 2.

Images scanning electron microscopy of samples subjected to different treatments (Aa: raw rice; Ab: 400 MPa, x 500; Ba: raw rice; Bb: 400 MPa; Bc: 600 MPa, x 2,300–2,500).

Figure 2.

Images scanning electron microscopy of samples subjected to different treatments (Aa: raw rice; Ab: 400 MPa, x 500; Ba: raw rice; Bb: 400 MPa; Bc: 600 MPa, x 2,300–2,500).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of textural parameters measured by instrumental TPA, to establish the cooking time in rice samples treated by boil cooking (𝜈: control; 𝜈: 400 MPa; 𝜈: 600 MPa). NOTE: Adhesiveness data are expressed as absolute values.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of textural parameters measured by instrumental TPA, to establish the cooking time in rice samples treated by boil cooking (𝜈: control; 𝜈: 400 MPa; 𝜈: 600 MPa). NOTE: Adhesiveness data are expressed as absolute values.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of textural parameters measured by instrumental TPA, to establish the cooking time in rice samples treated by microwave cooking (𝜈: control; 𝜈: 400 MPa; 𝜈: 600 MPa). NOTE: Adhesiveness data are expressed as absolute values.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of textural parameters measured by instrumental TPA, to establish the cooking time in rice samples treated by microwave cooking (𝜈: control; 𝜈: 400 MPa; 𝜈: 600 MPa). NOTE: Adhesiveness data are expressed as absolute values.

Figure 5.

Score plot of the canonical discriminant functions for the instrumental texture evaluated in rice samples (: group centroids).

Figure 5.

Score plot of the canonical discriminant functions for the instrumental texture evaluated in rice samples (: group centroids).

Figure 6.

Changes of apparent amylose content in soaked rice samples as a function of the treatments applied. The dashed vertical line separates unpressurized samples (left) from pressurized samples (right). Note the broken axis to highlight differences in treatments.

Figure 6.

Changes of apparent amylose content in soaked rice samples as a function of the treatments applied. The dashed vertical line separates unpressurized samples (left) from pressurized samples (right). Note the broken axis to highlight differences in treatments.

Table 1.

Pasting properties of Nuovo Maratelli rice flours as a function of pressurization treatment (10 min). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n=3).

Table 1.

Pasting properties of Nuovo Maratelli rice flours as a function of pressurization treatment (10 min). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n=3).

| Parameter |

Control |

400 MPa |

600 MPa |

F ratio |

p-value |

| PT |

65.60 ± 1.82 |

66.30 ± 0.37 |

64.30 ± 1.29 |

2.752 |

0.142 |

| PV (η / Pas) |

24.10 ± 0.65ab

|

27.00 ± 2.32a

|

23.10 ± 1.11b

|

5.248 |

0.040 |

| MV (η / Pas) |

15.90 ± 0.95 |

18.30 ± 2.05 |

15.10 ± 1.17 |

3.855 |

0.084 |

| FV (η / Pas) |

33.90 ± 0.87 |

35.90 ± 2.47 |

34.00 ± 1.27 |

1.349 |

0.358 |

| BI |

7.90 ± 0.89 |

7.20 ± 1.04 |

7.40 ± 0.38 |

0.580 |

0.589 |

Table 2.

Cooking properties of Nuovo Maratelli rice according to pressurization (10 min, 20 °C) and cooking treatments.

Table 2.

Cooking properties of Nuovo Maratelli rice according to pressurization (10 min, 20 °C) and cooking treatments.

| |

Control |

400 MPa |

600 MPa |

| Parameter |

boiling |

microwaving |

boiling |

microwaving |

boiling |

microwaving |

| Cooking time (min) |

14 ± 0 |

10 ± 0 |

12 ± 0 |

8 ± 0 |

8 ± 0 |

6 ± 0 |

| Moisture (g / 100 g sample) |

67.58 ± 0.06 |

62.69 ± 0.25 |

62.02 ± 0.91 |

53.33 ± 0.53 |

62.68 ± 0.25 |

49.42 ± 0.77 |

| Water uptake ratio |

2.33 ± 0.11a

|

1.96 ± 0.20a

|

1.92 ± 0.05b

|

1.63 ± 0.04b

|

1.63 ± 0.02c

|

1.57 ± 0.01b

|

| Expansion volume |

1.75 ± 0.28a

|

1.78 ± 0.31a

|

1.57 ± 0.09b

|

1.36 ± 0.05ab

|

1.15 ± 0.04b

|

1.12 ± 0.05b

|

| Grain elongation ratio |

68.50 ± 10.93a

|

60.48 ± 2.33a

|

54.64 ± 2.51ab

|

46.99 ± 0.95b

|

42.62 ± 1.64b

|

41.59 ± 0.64b

|

| Gruel solid loss (%) |

3.83 ± 0.67 |

1.28 ± 0.13c

|

3.81 ± 0.04 |

1.77 ± 0.12b

|

2.98 ± 0.85 |

2.32 ± 0.20a

|

Table 3.

Instrumental texture of unpressurized rice (control), and pressurized rice (10 min, 20 °C), and treated by the boil cooking method. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Table 3.

Instrumental texture of unpressurized rice (control), and pressurized rice (10 min, 20 °C), and treated by the boil cooking method. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations (n = 3).

| Parameter |

Control |

400 MPa |

600 MPa |

F ratio |

p-value |

| Hardness (N) |

188.82 ± 11.01b

|

237.81 ± 12.26a

|

254.49 ± 5.53a

|

34.710 |

0.001 |

| Adhesiveness (N s) |

–4.03 ± 0.46b

|

–1.52 ± 0.16a

|

–1.65 ± 0.28a

|

56.946 |

0.000 |

| Cohesiveness (%) |

55.20 ± 1.98b

|

63.58 ± 2.01a

|

64.19 ± 1.18a

|

24.309 |

0.001 |

| Resiliency (%) |

36.73 ± 2.51b

|

45.94 ± 2.07a

|

46.96 ± 1.17a

|

23.907 |

0.001 |

| Springiness (%) |

41.66 ± 3.73 |

47.50 ± 4.00 |

42.63 ± 4.27 |

1.831 |

0.240 |

| Gumminess (N) |

104.35 ± 8.99b

|

151.35 ± 12.17a

|

163.53 ± 5.82a

|

33.445 |

0.001 |

| Chewiness (N) |

43.70 ± 7.29b

|

71.97 ± 9.32a

|

69.96 ± 8.88a

|

10.231 |

0.012 |

Table 4.

Instrumental texture of unpressurized rice (control) and pressurized rice (10 min, 20 °C), and cooked by microwaving method. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations (n = 3).

Table 4.

Instrumental texture of unpressurized rice (control) and pressurized rice (10 min, 20 °C), and cooked by microwaving method. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations (n = 3).

| Parameter |

Control |

400 MPa |

600 MPa |

F ratio |

p-value |

| Hardness (N) |

227.89 ± 16.14a |

189.25 ± 11.62b |

210.35 ± 7.09ab |

7.557 |

0.023 |

| Adhesiveness (N s) |

–3.44 ± 0.67b |

–1.14 ± 0.21a |

–0.41 ± 0.12a |

44.355 |

0.000 |

| Cohesiveness (%) |

62.18 ± 1.37b |

63.60 ± 4.07ab |

69.47 ± 1.00a |

6.914 |

0.028 |

| Resiliency (%) |

45.01 ± 1.05 |

45.33 ± 4.33 |

51.49 ± 1.51 |

5.425 |

0.050 |

| Springiness (%) |

36.09 ± 3.40 |

37.77 ± 2.09 |

41.97 ± 6.74 |

1.346 |

0.329 |

| Gumminess (N) |

127.64 ± 9.13 |

126.21 ± 15.21 |

146.14 ± 6.74 |

3.088 |

0.120 |

| Chewiness (N) |

47.68 ± 7.01b |

46.04 ± 4.78ab |

61.24 ± 5.14a |

6.365 |

0.023 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).