Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Farmers

3.2. Farm Characteristics

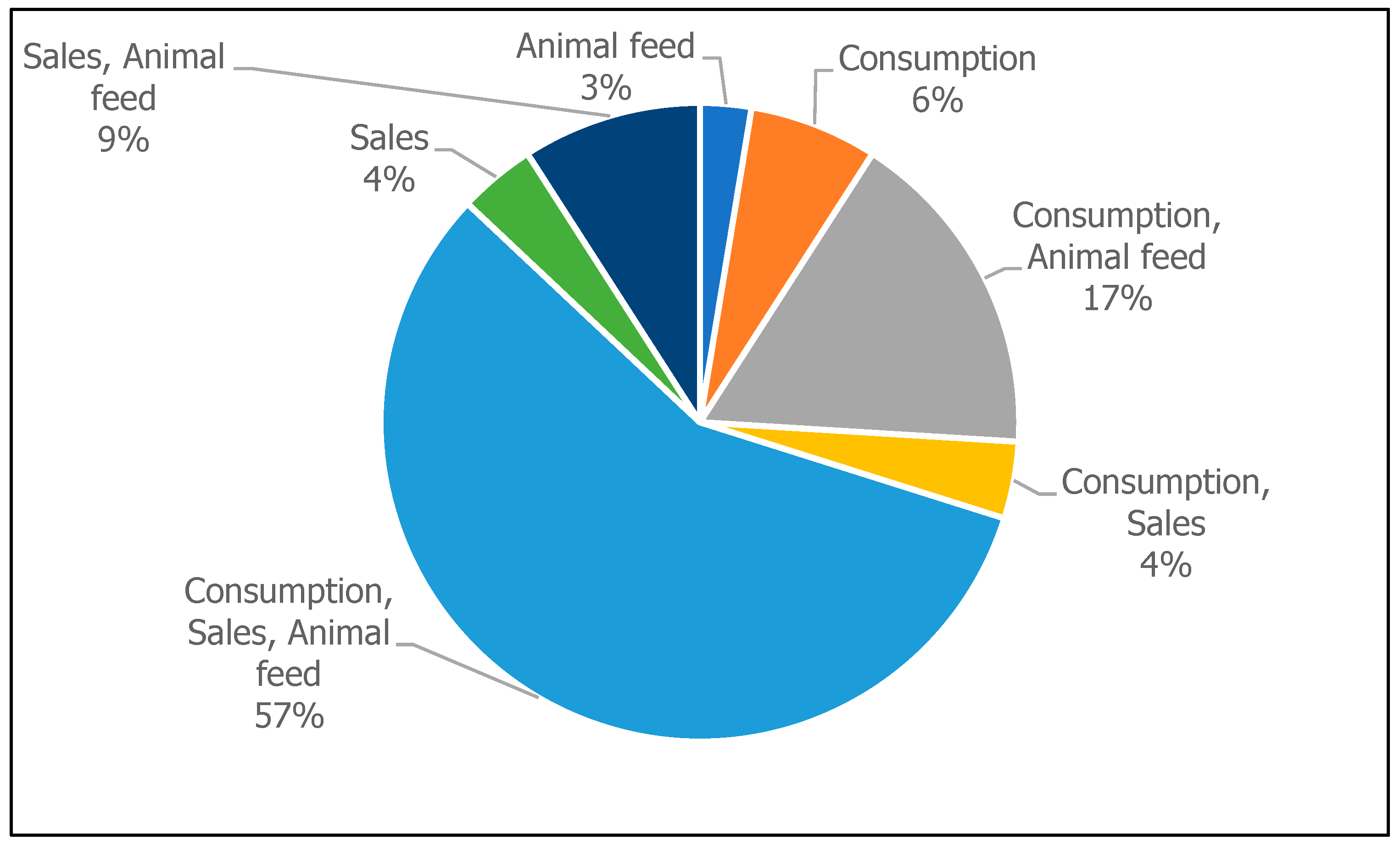

3.3. Purpose of Farming

3.4. Facilities Used to Store Maize, Storage Forms of Maize, Farmers’ Knowledge of Storage Pests and Control Practices

3.6. Conclusion and Recommendations

Funding

Ethical statement

Authorship contribution statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- L. Kuonen, L. Norgrove, Mulching on family maize farms in the tropics: A systematic review, Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 4 (2022) 100194. [CrossRef]

- O. Erenstein, M. Jaleta, K. Sonder, et al., Global maize production, consumption and trade: trends and R&D implications, Food security 14(2022) 1295-1319.

- A. Diko, W. Jun, Influencing factors of maize production in South Africa: The Case of Mpumalanga, free state and North West Provinces. Asian Journal of Advances in Agricultural Research, 14(2020), pp.25-34.

- H. Machekano, B.M. Mvumi, R. Rwafa, Postharvest knowledge, perceptions and practices of African small-scale maize and sorghum farmers, Julius-Kühn-Archiv (2018).

- A. Boakye, Estimating agriculture technologies’ impact on maize yield in rural South Africa, SN Business & Economics 3(2023) 149.

- K.N. Nwaigwe, An overview of cereal grain storage techniques and prospects in Africa, Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 4 (2019) 19-25.

- L.M. Mangena-Netshikweta, D.R. Katerere, P. Mngqawa, Grain production by rural subsistence farmers in selected districts of Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces of South Africa, Botswana Journal of African Studies 30(1) (2016).

- J.M. Thamaga-Chitja, S.L. Hendriks, G.F. Ortmann, et al., Impact of maize storage on rural household food security in Northern Kwazulu-Natal, Journal of Consumer Sciences 32 (2004). [CrossRef]

- R. Santpoort, The drivers of maize area expansion in sub-Saharan Africa. How policies to boost maize production overlook the interests of smallholder farmers, Land 9(2020) 68. [CrossRef]

- J. Swai, E. Mbega, A. Mushongi, and P. Ndakidemi, Post-harvest losses in maize store-time and marketing model perspectives in Sub-Saharan Africa, Journal of Stored Products and Postharvest Research 10 (2019).

- N. Fufa, T. Zeleke, D. Melese, et al., Assessing storage insect pests and post-harvest loss of maize in major producing areas of Ethiopia, International Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Technology 7(2021) 193-198.

- S. Khanam, M. Mushtaq, Farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices towards rodent pests and their management in rural Pothwar, Pakistan, Pure and Applied Biology (PAB) 10(2021) 1181-1193.

- H.T. Duguma, Indigenous knowledge of farmer on grain storage and management practice in Ethiopia, Food and Science Nutrition Technology 5(2020) 1-4.

- M. Tadesse, Post-harvest loss of stored grain, its causes and reduction strategies, Food Science and Quality Management 96 (2020) 26-35.

- M.B. Saeed, M.D. Laing, Biocontrol of maize weevil, Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in maize over a six-month storage period, Microorganisms 11(2023): 1261.

- M. Berhe, B. Subramanyam, M. Chichaybelu, et al., Post-harvest insect pests and their management practices for major food and export crops in East Africa: An Ethiopian case study, Insects 13(2022) 1068. [CrossRef]

- K.D. Ileke, L.C. Nwosu, and E.O. Emeribe, Control of stored products arthropod pests, Forensic Entomology (2023) 75.

- S. Tiwari, R.B. Thapa, S. Sharma, Use of botanicals for weevil management: An integrated approach of maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais) management in a storage condition, Journal of the Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science 35 (2018) 167-72. [CrossRef]

- I.A.T. de Araújo Ribeiro, R. da Silva, A.G. da Silva, et al., Chemical characterization and insecticidal effect against Sitophilus zeamais (maize weevil) of essential oil from Croton rudolphianus leaves, Crop protection 129 (2020) 105043.

- M.S. AL-Ahmadi, Pesticides, anthropogenic activities, and the health of our environment safety, In Pesticides-use and misuse and their impact in the environment, IntechOpen (2019).

- C.A. Damalas, S.D. Koutroubas, Farmers’ exposure to pesticides: toxicity types and ways of prevention, Toxics 1 (2017) 1-10. [CrossRef]

- P.A. Mkenda, E. Mbega, P.A. Ndakidemi, Accessibility of agricultural knowledge and information by rural farmers in Tanzania-A review, Journal of Biodiversity Environmental Sciences 11 (2017) 216-228.

- KSDM DRAFT ANNUAL REPORT 2022-2023, https://lg.treasury.gov.za/supportingdocs/EC157/EC157_Annual%20Report%20Draft_2023_Y_20240205T131821Z_nomandelan.pdf.

- M. Mtyobile, S. Mhlontlo, Evaluation of tillage practices on selected soil chemical properties, maize yield and net return in OR Tambo District, South Africa, Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development 13(2021) 158-164.

- Eastern Cape Provincial Government (ECPG). The Eastern Cape – The Home of Legends (2021/2023), https://ecprov.gov.za/the-eastern-cape.aspx.

- I.K. Agbugba, M. Christian, A. Obi, Economic analysis of smallholder maize farmers: Implications for public extension services in Eastern Cape, South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 48 (2020) 50-63. [CrossRef]

- D. Kibirige, Smallholder commercialization of maize and social capital in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. International Journal of Economics, commerce and management, 4(2016), pp.236-252.

- Chiwuzie, E.M. Prince, S.T. Olawuyi, Women and Land Governance in Selected African Countries: A Review, Journal of Law, Society and Development 9 (2022) 1-12.

- A.J. Afolayan, P. Masika, O.O. Odeyemi, Farmers' knowledge and experience of indigenous insect pest control in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, Indilinga African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems 5(2006) 167-174. [CrossRef]

- S. Qange, L. Mdoda, Factors affecting subsistence farming in rural areas of Nyandeni local municipality in the Eastern Cape Province, South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 48(2020) 92-105.

- D. Bese, E. Zwane, P. Cheteni, The use of sustainable agricultural methods amongst smallholder farmers in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa, African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 13(2021) 261-271. [CrossRef]

- L. Mdoda, L.S. Gidi, Impact of Land Ownership in Enhancing Agricultural Productivity in Rural Areas of Eastern Cape Province, South African Journal of Agricultural Extension 51(2023) 1-23.

- M. Sibanda, A. Mushunje, C.S. Mutengwa, Factors influencing the demand for improved maize open pollinated varieties (OPVs) by smallholder farmers in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, Journal of Cereals and Oilseeds 7(2016) 14-26. [CrossRef]

- E. Nzeyimana, G. Odularu, Small holder farmers’ postharvest management behaviour and influence on maize production cycle in Rwanda, International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 14 (2024) 93-105.

- M.G. Nenna, E.G. Osegbue, C.G. Ojiako-Chigozie, Assessment of Maize Storage Techniques Utilized by Small Scale Farmers in Anambra State, Nigeria, International Journal of Agriculture and Earth Science 5(2023)1-14. [CrossRef]

- T.K. Mekonen, B.Y. Wubetie, Determinants of the use of hermetic storage bags for maize storage among smallholder farmers in northwest Ethiopia, Advances in Agriculture 2021(2021) 6644039. [CrossRef]

- S. Tiwari, R.B. Thapa, S. Sharma, Use of botanicals for weevil management: An integrated approach of maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais) management in a storage condition, Journal of the Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science 35 (2018) 167-72. [CrossRef]

- J.R. Mendoza, L. Sabillón, R. Howard, et al., Assessment of handling practices for maize by farmers and marketers in food-insecure regions of Western Honduras, Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 16 (2024) 101140. [CrossRef]

- C.N. Nwogu, B.N. Nwankwojike, O.S. Onwuka, et al., Design and Development of a Second-class Lever for Maize Shelling Operation (2024).

- M. Megerssa, M. Negeri, E. Getu, Farmers’ perceptions, existing knowledge and current control methods of major stored maize grain insect pests in West Showa, Ethiopia, Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 54(2021) 1778-1796. [CrossRef]

- Y.M. Shabana, M.E. Abdalla, A.A. Shahin, et al., Efficacy of plant extracts in controlling wheat leaf rust disease caused by Puccinia triticina, Egyptian Journal of Basic Applied Sciences 1 (2017) 67-73. [CrossRef]

- S. Katwal, K. Malbul, S.K. Mandal, et al., “Successfully managed aluminium phosphide poisoning: A case report”. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 70 (2021) 102868.

- L. Shi, T. Jian, Y. Tao, et al., Case report: acute intoxication from phosphine inhalation, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(2023) 5021.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 55 | 71.43 |

| Female | 22 | 28.57 | |

| Age (years) | 18-35 | 4 | 5.19 |

| 36-55 | 25 | 32.47 | |

| 56+ | 48 | 62.34 | |

| Education level | None | 12 | 15.58 |

| Primary | 21 | 27.27 | |

| Secondary | 38 | 49.35 | |

| Tertiary | 6 | 7.79 | |

| Farming experience (years) | 1 | 1 | 1.30 |

| 2-5 | 11 | 14.29 | |

| 6-9 | 6 | 7.79 | |

| 10+ | 59 | 76.62 |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Methods used to store | Metal tanks | 63 | 81.82 |

| Metal tanks and sacks in residential houses | 8 | 10.39 | |

| Sacks in residential houses | 6 | 7.79 | |

| Storage form | Shelled maize | 75 | 97.40 |

| Unshelled maize | 2 | 2.60 |

|

| Maize weevils infestation | Yes | 69 | 89.61 |

| No | 8 | 10.39 | |

| Other pests apart from maize weevils | Grain moths | 57 | 74.03 |

| Control practices | Use of chemical (Aluminium Phosphide) | 65 | 84.42 |

| Use of chemical (Aluminium Phosphide) and other control practices (dry pepper, camphor and wood ash) | 10 | 12.99 | |

| Doing nothing | 1 | 1.30 | |

| Removing affected grains | 1 | 1.30 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).