Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations for Indicator Development

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Decree of The President of The Russian Federation dated May 13, 2000 No. 849. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/15492 (accessed on 10/04/2024).

- Federal Law Dated July 20, 2000 No 104-FZ. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/15841 (accessed on 11/04/2024).

- Lagutina, M. Russia’s Arctic policy in the twenty-first century: national and international dimensions. Lexington Books: Maryland, United States, 2019; pp. 5-10.

- The Russian Federation, Arctic Council. Arctic-council.org. Available online: https://arctic-council.org/about/states/russian-federation/ (accessed on 10/04/2024).

- Okunev, I. , & Oskolkov, P. Consequences of Involution of Russian Regions (Comparative Analysis Based on Expert Interviews). J. Political Theory Political Philos. Sociol. Politics Polit. 2019, 92, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosstat, 2016-2021, Arctic Zone of The Russian Federation. Rosstat.gov.ru. Available online: from https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/arc_zona.html (accessed on 11/04/2024).

- Federal law Dated April 30, 1999 No. 82-FZ. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/13778 (accessed on 08/04/2024).

- Order of The Government of Russia Dated May 8, 2009 No 631-r. Government.ru. Available online: http://government.ru/docs/30064/ (accessed on 10/04/2024).

- Tishkov, V. Russian Arctic: indigenous peoples and industrial development. Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology. N. N. Miklukho-Maklay RAS: Moscow, Russia, 2016, pp. 50-60.

- Arruda, G. , & Krutkowski, S. Arctic governance, indigenous knowledge, science and technology in times of climate change: Self-realization, recognition, representativeness. Journal of Enterprising Communities 2017, 11(4), pp. 514–528. [CrossRef]

- Derendyaeva, O. Climatic Risks of Hydrocarbon Production in the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation. In Energy of the Russian Arctic: Ideals and Realities; Valery I. Salygin Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 425–439. [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, R. (b). Indigenous Economies, Theories of Subsistence, and Women. Exploring the Social Economy Model for Indigenous Governance. Am. Indian Q. 2011, 35, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannikova, Y. Traditional economy of the indigenous people of the North Yakutia in the post-Soviet period: some research results. Arctic and North 2017, 28, pp. 92–105. [CrossRef]

- Russian Population Census 2020. Rosstat.gov.ru. Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn/2020 (accessed on 10/04/2024).

- Tysiachniouk, M. , & Olimpieva, I. Caught between traditional ways of life and economic development: Interactions between indigenous peoples and an oil company in numto nature park. Arctic Review on Law and Politics 2019, 10, pp. 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention C050 - Recruiting of Indigenous Workers Convention, 1936. International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:14416074785345::NO::P12100_SHOW_TEXT:Y: (accessed: 08/04/2024).

- Convention C064 - Contracts of Employment (Indigenous Workers) Convention, 1939. International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C064 (accessed on 08/04/2024).

- Convention C169. Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989. International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:55:0::NO::P55_TYPE,P55_LANG,P55_DOCUMENT,P55_NODE:REV,en,C169,/Document (accessed on 08/04/2024).

- Convention C107 - Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention, 1957. International Labour Organization. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C107 (accessed on 08/04/2024).

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples United Nations. Un.org. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed on 13/04/2024).

- Decree of The President of The Russian Federation Dated June 15, 1996 No 909. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/9571 (accessed: 08/04/2024).

- Constitution of the Russian Federation of December 12, 1993 as amended on July 1, 2020. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/constitution (accessed on 07/04/2024).

- Federal law Dated October 20, 2022 No 403-FZ. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/48443 (accessed on 08/04/2024).

- Decree of The President of The Russian Federation Dated March 5, 2020 No 164. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/45255 (accessed on 08/04/2024).

- Decree of The President of The Russian Federation Dated October 26, 2020 No 645. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/45972 (accessed on 08/04/2024).

- Order of The Government of Russia Dated April 15, 2021 No 996. Government.ru. Available online: http://government.ru/docs/42000/ (accessed on 13/04/2024).

- Order of The Government of Russia Dated March 30, 2021 No 484. Garant.ru. Available online: https://base.garant.ru/400534977/?ysclid=luul5suez077285619 (accessed on 11/04/2024).

- Gad, U., Jacobsen, U., & Strandsbjerg, J. Politics of sustainability in the Arctic: A Research Agenda. In Springer Polar Sciences, Fondahl, G., Wilson, G. Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 13–23.

- Jokela, T. , Coutts, G. , & Huhmarniemi, M. Tradition and Innovation in Arctic Sustainable Art and Design. Human Culture Education 2020, 1, pp. 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, M. Indigenous Peoples, Self-determination and the Arctic Environment. The Arctic 2019, pp. 377–409. [CrossRef]

- Recommendations, Arctic Council, 2021. Arctic Council. Available online: https://arctic-council.org/explore/work/policy-recommendations/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework. Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1562782976772/1562783551358 (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Kingdom of Denmark Strategy for the Arctic. Ministry of foreign affairs of Denmark. Available online: https://um.dk/en/foreign-policy/the-arctic (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- The Norwegian Government’s Arctic Policy, 2021. Government.no. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/arctic_policy/id2830120/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Lintott, B. , & Rees, G. Arctic Heritage at Risk: Insights into How Remote Sensing, Robotics and Simulation Can Improve Risk Analysis and Enhance Safety. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S. , Das, D., Mukherjee, S., & Saha, A. Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity of Arctic Biome. Journal of Climate Change 2022, 8(2), pp. 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, W. , Lemay, M., & Allard, M. Arctic permafrost landscapes in transition: towards an integrated Earth system approach. Arctic science 2017, 3(2), pp. 39–64. [CrossRef]

- Andreev, A. , & Klimanov, V. Quantitative Holocene climatic reconstruction from Arctic Russia. Journal of Paleolimnology 2000, 24(1), pp. 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, V. A composite reconstruction of the Russian Arctic climate back to A.D. 1435. The Polish Climate in the European Context: An Historical Overview 2010, pp. 295–326. [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, P. , Andreev, A., Anderson, P., Lozhkin, A., Leipe, C., Haltia, E., Nowaczyk, N., Wennrich, V., Brigham-Grette, J., & Melles, M. A pollen-based biome reconstruction over the last 3.562 million years in the Far East Russian Arctic – new insights into climate–vegetation relationships at the regional scale. Climate of the Past 2013, 9(6), pp. 2759–2775. [CrossRef]

- Malkova, G. , Drozdov, D., Vasiliev, A., Gravis, A., Kraev, G., Korostelev, Y., Nikitin, K., Orekhov, P., Ponomareva, O., Romanovsky, V., Sadurtdinov, M., Shein, A., Skvortsov, A., Sudakova, M., & Tsarev, A. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Permafrost in the Western Part of the Russian Arctic. Energies 2022, 15, pp. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Romasheva, N. , Smirnova, N., & Lvov, V. Problems and prospects for the development of Arctic oil and gas resources in Russia. Russ. Econ. Internet J. 2018, 2, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zaikov, K. , Kondratov, N., Kudryashova, E., Lipina, S., & Chistobaev, A. Scenarios for the development of the Arctic region (2020–2035). Arctic and North 2019, 35, pp. 5–24. [CrossRef]

- Kryukov, V. , & Kryukov, Yu. The Economy of the Arctic in the Modern Coordinate System. Outlines of Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, Law 2020, 12(5), pp. 25–52. [CrossRef]

- Vylegzhanina, A. Certain socioeconomic problems of development of the Arctic territories. Studies on Russian Economic Development 2017, 28(2), pp. 180–190. [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, F. Indigenous people of the Arctic: concept, the status of culture. Arct. North 2013, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokurova, U. The problem of legal definition of the indigenous peoples of the Arctic. Russia: Society, Politics, History 2022, 2(2), pp. 35–48. https://www.ru-society.com/jour/article/view/22/14.

- Nosov, S., Bondarev, B., Gladkov, A., & Gassiy, V. Land Resources Evaluation for Damage Compensation to Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic (Case-Study of Anabar Region in Yakutia). Resources 2019, 8(3), pp.1-13. [CrossRef]

- Federal law Dated July 24, 2002 No 101-FZ. Kremlin.ru. Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/18935 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Federov, V. , Zhuravel, V., Grinyaev, S., & Medvedev, D. Scientific approaches to defining the territorial boundaries of the Arctic. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 302(1), pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Gassiy, V. , & Potravny, I. The assessment of the socio-economic damage of the indigenous peoples due to industrial development of Russian Arctic. Czech Polar Reports 2017, 7(2), pp. 257–270. [CrossRef]

- Nenasheva, M. Social Impact Assessment as a Tool for Sustainable Development of the Russian Arctic. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast 2019, 2 (62), pp. 196-210. [CrossRef]

- Sleptsov, A. , & Petrova, A. Ethnological Expertise in Yakutia: The Local Experience of Assessing the Impact of Industrial Activities on the Northern Indigenous Peoples. Resources 2019, 8(3), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Stroykov, G. , Vasilev, Y., & Zhukov, O. Basic Principles (Indicators) for Assessing the Technical and Economic Potential of Developing Arctic Offshore Oil and Gas Fields. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2021, 9(12), pp. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Gutman, S. , & Teslya, A. Selecting and assessing indicators for monitoring environmental safety in the Russian Arctic. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 302(1), pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A. , Gutman, S., Zaychenko, I., & Rytova, E. The Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation through The Concept of a Regional Indicators System. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 2015, 6(5 S4), pp. 379-386. [CrossRef]

- The United Nations Resolution A/RES/68/261. Undocs.org. Available online: https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FRES%2F68%2F261&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Chaddock, R. Principles and Methods of Statistics. Houghton Mifflin: Boston, United States, 1925; pp. 200-230.

- Balm, G. Benchmarking and gap analysis: what is the next milestone? Benchmarking for Quality Management & Technology 1996, 3(4), pp. 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Ibbs, C. , & Kwak, Y. Assessing Project Management Maturity. Project management journal 2000, 31(1), pp. 32–43. [CrossRef]

- Lasswell, H. Conflict and leadership: the process of decision and the nature of authority. Conflict in Society 1966, pp. 210-228.

- Liu, M., Feng, X., Wang, S. & Zhong, Y. Does poverty-alleviation-based industry development improve farmers’ livelihood capital? Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2021, 20(4), 915–926. [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005. Millenniumassessment.org. 2005. Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/index.html (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Good Practice Guidelines for Indicator Development and Reporting, 2009. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/development/evaluation/qualitystandards.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Kuokkanen, R. (a). From Indigenous Economies to Market-Based Self-Governance: A Feminist Political Economy Analysis. Can. J. Political Sci. 2011, 44, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarayeva, Y. , Kistova, A., Pimenova, N., Reznikova, K., & Seredkina, N. Taymyr reindeer herding as a branch of the economy and a fundamental social identification practice for indigenous peoples of the Siberian Arctic. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 2015, 6(3), pp. 225–232. [CrossRef]

- Gover, K. Tribal Constitutionalism: State, Tribes, and the Governance of Membership in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the Univted States; Oxford University press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2012; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, B. Indigenous identity: Summary and future directions. Statistical Journal of the IAOS 2019, 35, pp. 147–157. [CrossRef]

- Koptseva, N. , & Kirko, V. The impact of global transformations on the processes of regional and ethnic identity of indigenous peoples Siberian arctic. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 2015, 6(3), pp. 217–224. [CrossRef]

- Cocks, M. Biocultural diversity: Moving beyond the realm of “indigenous” and “local” people. Human Ecology 2006, 34(2), pp. 185–200. [CrossRef]

- Tassell-Matamua, N. , Lindsay, N., Bennett, A., & Masters-Awatere, B. Maori cultural identity linked to greater regard for nature: Attitudes and (less so) behavior. Ecopsychology 2021, 13(1), pp. 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005. Millenniumassessment.org. Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/index.html (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- EU ecosystem assessment. Publications Office of the EU, 2021. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/81ff1498-b91d-11eb-8aca-01aa75ed71a1/language-en#:~:text=The%20EU%20ecosystem%20assessment%20analysed,and%20lakes%2C%20and%20marine%20ecosystems (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future, 1987. The United Nations. Available online: https://gat04-live-1517c8a4486c41609369c68f30c8-aa81074.divio-media.org/filer_public/6f/85/6f854236-56ab-4b42-810f-606d215c0499/cd_9127_extract_from_our_common_future_brundtland_report_1987_foreword_chpt_2.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Lax, J., & Krug, J. Livelihood assessment: A participatory tool for natural resource dependent communities. Thunen Working Papers 7; Johann Heinrich von Thunen Institute, Federal Research Institute for Rural Areas, Forestry and Fisheries: Braunschweig, Germany, 2024; pp. 1-21.

- Chapargina, A. , & Dyadik, N. Statistical Analysis of the Financial Solvency of the Russian Arctic Regions. Voprosy Statistiki 2021, 28(1), pp. 28–37. [CrossRef]

- Selin, V., & Vyshinskaya, Yu. The economy of the Arctic region and corporations at the present stage. Bulletin of the Kola Science Center RAS 2015, 4(23), pp. 90–99. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ekonomika-arkticheskih-regionov-i-korporatsiy-na-sovremennom-etape?ysclid=luuxfwlpxb701461478.

- Tishkov, V. Russian Arctic: indigenous peoples and industrial development. Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology. N. N. Miklukho-Maklay RAS: Moscow, Russia, 2016; pp. 1-272.

- Anderson, J. E., Brady, D.W., Bullock, III, C.S., & Stewart, Jr., J. Public policy and politics in America; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, 1984; pp. 1-434.

- Order of the Government of Russia Dated 11 April, 2021 No 978-r. Government.ru. Available online: http://government.ru/docs/42009/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Drozdova, I. , Alievskaya, N., & Belova, N. Problems and Prospects for the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering 2023, 206, pp.137–143. [CrossRef]

- Larchenko, V. , & Kolesnikov, R. Regions of the Russian Arctic Zone: State and Problems at the Beginning of the New Development Stage. International Journal of Engineering & Technology 2018, 7(3.14), pp. 369-375. [CrossRef]

- Leksin, V. , & Porfiriev, B. The Russian Arctic: The Logic and Paradoxes of Change. Studies on Russian Economic Development 2019, 30(6), pp. 594–605. [CrossRef]

- Zamyatina, N., & Plyasov, A. Russian Arctic: a new understanding of ongoing processes; URSS: Moscow, Russia, 2020; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, F. Indigenous people of the Arctic: concept, the status of culture. Arct. North 2013, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Khoteeva, E. , & Stepus, I. Population Migration in the Russian Arctic in Statistical Estimates and Regional Management Practice. Problems of Territory’s Development 2023, 2 (124), pp. 110-128. [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, D. The population dynamics in the Russian Arctic. Mir [World] (Modernization. Innovation. Research) 2016, 6(4(24)), pp. 51–57. [CrossRef]

- Korchak, E. The long-term dynamics of the social space of the Russian Arctic. Arctic and North 2020, 38, pp. 121–139. [CrossRef]

- Ilinova, A. , & Dmitrieva, D. Sustainable Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation: Ecological Aspect. Biosciences, Biotechnology Research Asia 2016, 13, pp. 2101-2106. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, V. , Dudin, M., & Yuryeva, A. Strategic development of the arctic region in the context of great challenges and threats. Economy of Regions 2020, 16(3), pp. 680–695. [CrossRef]

- Gutenev, M. , Lagutina, M., & Sergunin, A. Russian Universities as Actors of Arctic Science Diplomacy. Vysshee Obrazovanie v Rossii 2023, 32(8–9), pp. 70–88. [CrossRef]

- Kurelyk, A. Reindeer’s breeding at Yakutsk Republic of Soviet Union; Knizhnoe izdatelstvo: Yakutsk, Russia, 1982; pp. 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- Syrovatsky, D. (2000). Organization and economy of reindeer’s breeding; Sakhapolygrphizdat, Yakutsk, Russia, 2000; pp. 1-407.

- Tarasov, M. , Val, O., & Teryutina, M. Economic efficiency and development of the third domain of reindeer husbandry (in the republic of Sakha). E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 389, pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Gerasimova, I. , Oblova, I., & Golovina, E. The Demographic Factor Impact on the Economics of the Arctic Region. Resources 2021, 10(11), pp.1-16. [CrossRef]

- Potravnaya, E. , & Kim, H. Economic behavior of the indigenous peoples in the context of the industrial development of the Russian arctic: A gender-sensitive approach. Region: Regional Studies of Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia 2020, 9(2), pp. 101–126. [CrossRef]

- Mardikian, L. , & Galani, S. Protecting the Arctic Indigenous Peoples’ Livelihoods in the Face of Climate Change: The Potential of Regional Human Rights Law and the Law of the Sea. Human Rights Law Review 2023, 23(3), pp. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, V. , Alekseenko, A., Karthe, D., & Puzanov, A. Manganese Pollution in Mining-Influenced Rivers and Lakes: Current State and Forecast under Climate Change in the Russian Arctic. Water 2022, 14(7), pp. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Romasheva, N. , Dmitrieva, D., Tcvetkov, P., Cherepovitsyn, A., & Vladimirovich, F. Energy Resources Exploitation in the Russian Arctic: Challenges and Prospects for the Sustainable Development of the Ecosystem. Energies 2021, 14(24), pp. 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Vladimirova, V. Continuous Militarization as a Mode of Governance of Indigenous People in the Russian Arctic. Politics and Governance 2024, 12, pp. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Sergunin, A. , & Shibata, A. Implementing the 2017 Arctic Science Cooperation Agreement: Challenges and Opportunities as regards Russia and Japan. Yearbook of Polar Law 2022, 14, pp. 45–75. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A. Lost Generations? Indigenous Population of the Russian North in the Post-Soviet Era. Canadian Studies in Population 2008, 35(2), pp. 269-290. [CrossRef]

- Rozanova, M. Indigenous urbanization in Russia’s arctic the case of nenets autonomous region. Sibirica 2019, 8(3), pp. 54–91. [CrossRef]

- Klokov, K., Krasovskaya, T., & Yamskov, A. Problems of a transition to the sustainable development of territories with indigenous population in the Russian Arctic; Institute of Anthropology and Ethnology: Moscow, Russia, 2001; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkopeeva, M., Corell, R., Maynard, N., Turi, E., Eira, I., Oskal, A., & Mathiesen, S. Framing Adaptation to Rapid Change in the Arctic. In Reindeer Husbandry; Mathiesen, S.D., Eira, I.M.G., Turi, E.I., Oskal, A., Pogodaev, M., Tonkopeeva, M., Eds.; Springer Polar Sciences: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M. , Nicolson, C., Kofinas, G., Tetlichi, J., & Martin, S. Adaptation and sustainability in a small arctic community: Results of an agent-based simulation model. Arctic 2004, 57(4), pp. 401–414. [CrossRef]

- Poppel, B., & Kruse, J. The Importance of a Mixed Cash- and Harvest Herding Based Economy to Living in the Arctic – An Analysis on the Survey of Living Conditions in the Arctic (SLiCA). In Quality of Life and the Millennium Challenge; Møller, V., Huschka, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2008; Volume 35, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, S. , & Shevareva, Y. Problems and perspectives of the development of traditional activities of indigenous peoples from the Russian Arctic and the Far East. Regional Studies 2017, 4(2), pp. 26-44. [CrossRef]

- Orbaek, J. Borre. Arctic alpine ecosystems and people in a changing environment. Polar Rec. 2008, 44, 367–369. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, S., & Gunn, K. Indigenous Belonging: A Commentary on Membership and Identity in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; Oxford University Pres: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2013; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, A. Indigenous Self-Government in the Arctic, and their Right to Land and Natural Resources. Yearbook of Polar Law 2009, 1, pp. 245–281. [CrossRef]

- Penikett, T. An Unfinished Journey: Arctic Indigenous Rights, Lands, and Jurisdiction? Seattle Univ. Law Rev. 2008, 37, 1127–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Varnai, Z. , & Szeverenyi, S. Identity and language in an Arctic city: the case of the indigenous peoples in Dudinka. Yearbook of Finno-Ugric Studies 2022, 16(4), pp. 701–720. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. , Yang, L., Lobanov, A. A., Andronov, S. V., Lidiya, &, & Lobanova, P. Sino-Russian cooperation on the sustainable utilization of Arctic biological resources: modernizing traditional knowledge. Advances in Polar Science 2020, 31(3), pp. 224-235. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, H. , Danielsen, F., Fidel, M., Hausner, V., Horstkotte, T., Johnson, N., Lee, O., Mukherjee, N., Amos, A., Ashthorn, H., Ballari, O., Behe, C., Breton-Honeyman, K., Retter, G., Buschman, V., Jakobsen, P., Johnson, F., Lyberth, B., Parrott, J., Vronski, N. The need for transformative changes in the use of Indigenous knowledge along with science for environmental decision-making in the Arctic. People and Nature 2020, 2(3), pp. 544–556. [CrossRef]

- Savvinova, A. , & Zakharov, M. Indigenous knowledge transfer through participatory mapping: attitude of the arctic population to communications using mental maps. Abstracts of the ICA 2023, 6, pp. 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Peralta, L. , Sanchez-Moreno, E., & Herrera, S. Aging and Family Relationships among Aymara, Mapuche and Non-Indigenous People: Exploring How Social Support, Family Functioning, and Self-Perceived Health Are Related to Quality of Life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(15), pp. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, A. , & Evengård, B. Climate change, its impact on human health in the Arctic and the public health response to threats of emerging infectious diseases. Global Health Action 2009, 2(1), pp. 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Revich, B. , Eliseev, D., & Shaposhnikov, D. Risks for Public Health and Social Infrastructure in Russian Arctic under Climate Change and Permafrost Degradation. Atmosphere 2022, 13(4), pp. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. , & Schertzer, R. Is Indigeneity like Ethnicity? Theorizing and Assessing Models of Indigenous Political Representation. Canadian Journal of Political Science 2019, 52(4), pp. 677–696. [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. , & Jolly, D. Adapting to climate change: Social-ecological resilience in a Canadian western arctic community. Ecology and Society 2002, 5(2), pp. 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Borish, D. , Cunsolo, A., Snook, J., Shiwak, I., Wood, M., Dale, A., Flowers, C., Goudie, J., Hudson, A., Kippenhuck, C., Purcell, M., Russell, G., Townley, J., Mauro, I., Dewey, C., & Harper, S. “It’s like a connection between all of us”: Inuit social connections and caribou declines in Labrador, Canada. Ecology and Society 2022, 27(4), pp. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Curry, T. , Meek, C., & Berman, M. Informal institutions and adaptation: patterns and pathways of influence in a remote Arctic community. Local Environment 2021, 26(9), pp. 1070–1091. [CrossRef]

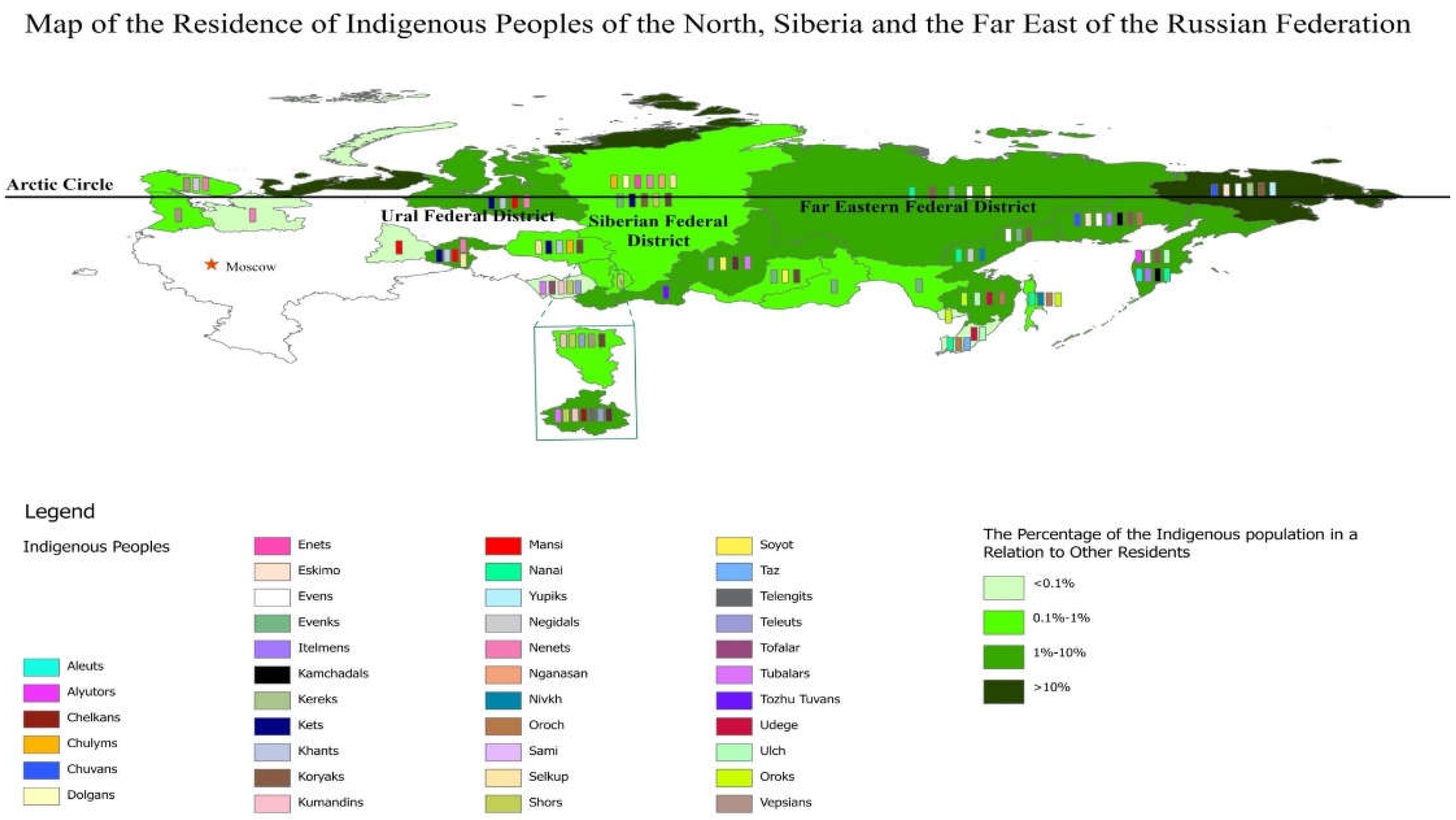

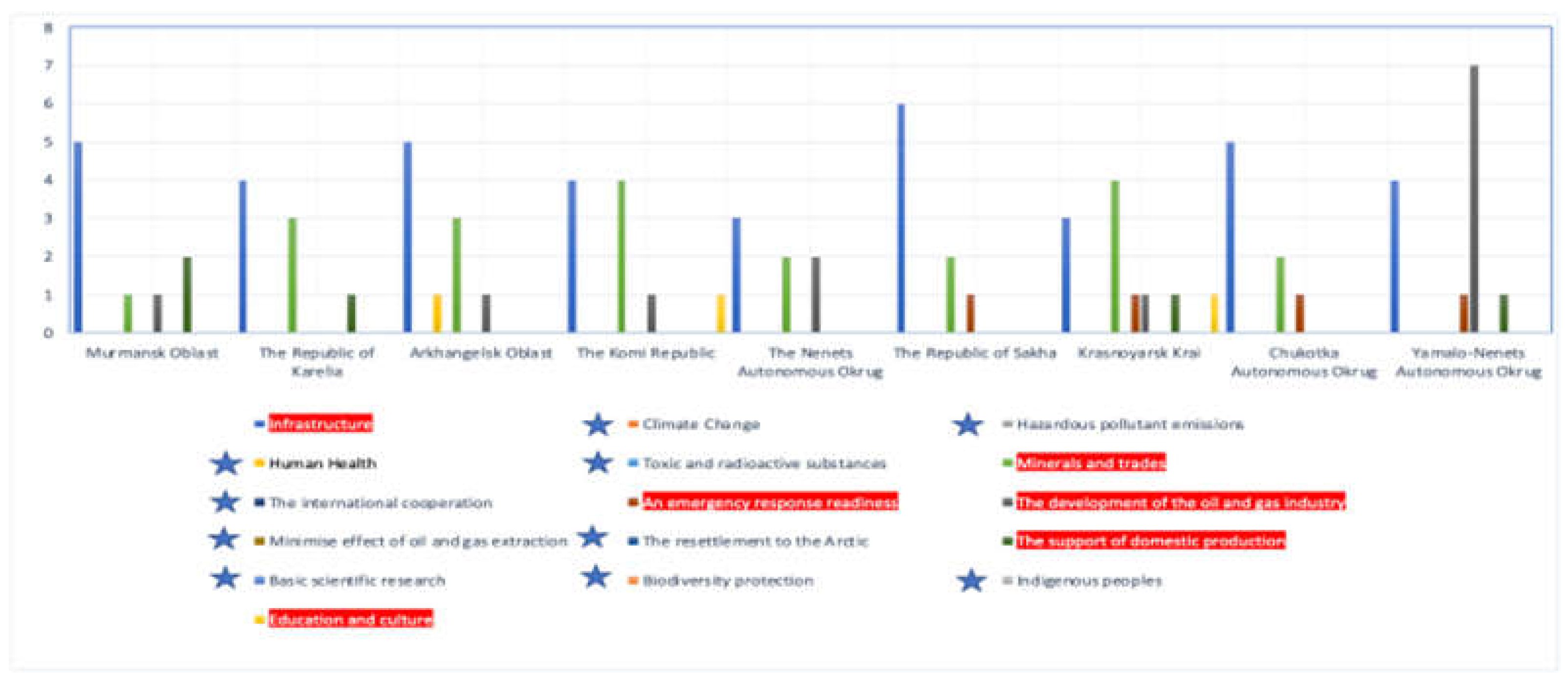

indicates policies that score zero for each district. Source: created by the author and with the information from [26].

indicates policies that score zero for each district. Source: created by the author and with the information from [26].

indicates policies that score zero for each district. Source: created by the author and with the information from [26].

indicates policies that score zero for each district. Source: created by the author and with the information from [26].

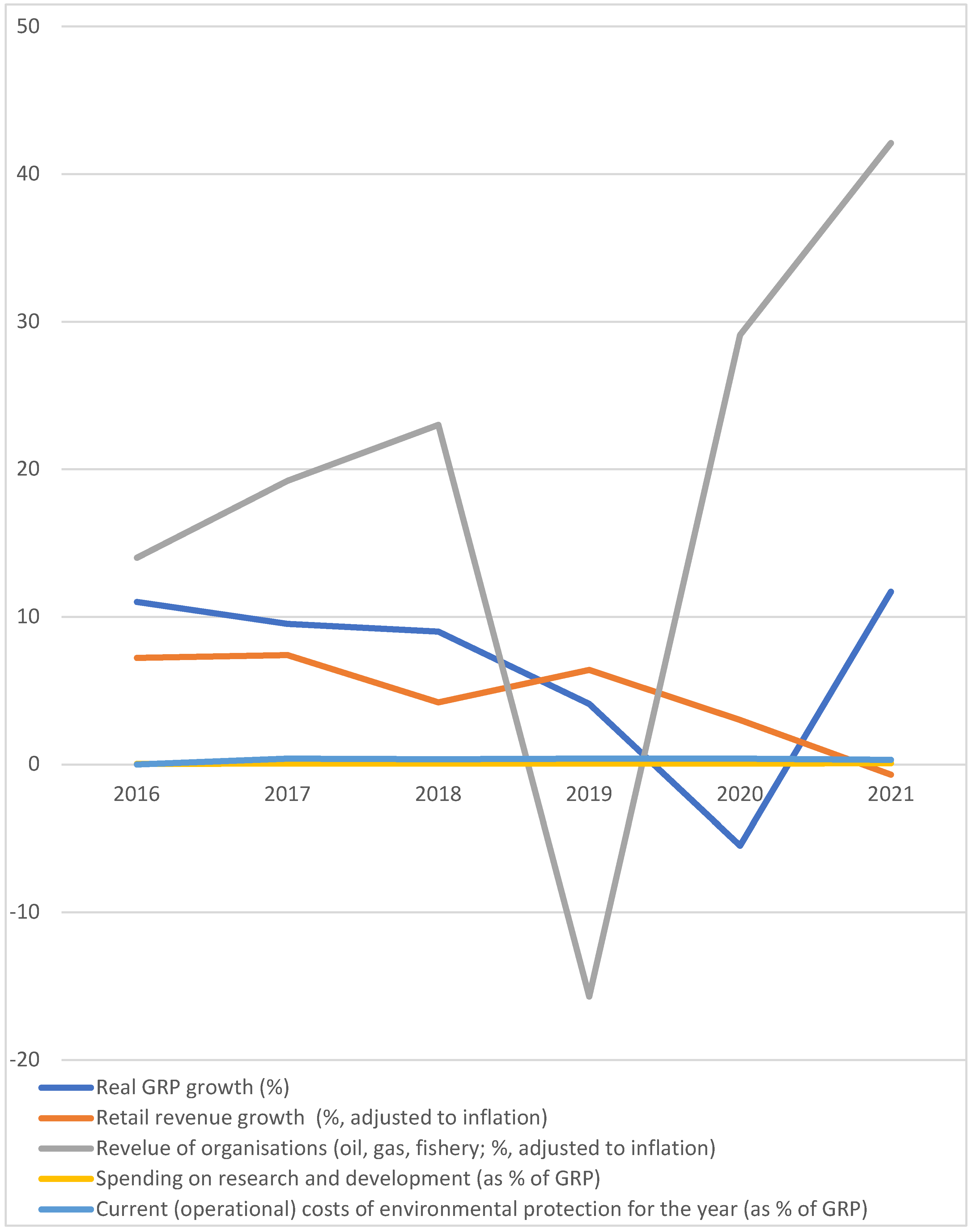

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metrics | |||||||

| 1 | Gross domestic product (million rubles) | 6570457 | 7196332 | 7843960 | 8169184 | 7719007 | 8625972 |

| 2 | Annual household consumption (rubles/per member) | 314954 | 329106 | 349151 | 395803 | 448546 | 443441 |

| 3 | Investment (without small businesses, million rubles) | 1789620.46 | 4195337.04 | 11555152.5 | 7208736.41 | 16463976.7 | 6156112.19 |

| 4 | Retail revenue (million rubles) | 483656.134 | 524062.823 | 542519.184 | 578931.192 | 597223.62 | 639859.95 |

| 5 | Revenue of organizations (million rubles) | 4520822.66 | 5434362.21 | 6636308.46 | 5605402.56 | 7247074.06 | 10256409.7 |

| 6 | Balanced financial result (profit minus loss, million rubles) | 942630.231 | 732191.981 | 932936.889 | 1888492.82 | 765763.035 | 2345965.49 |

| 7 | Postgraduate graduation in the reporting year (people) | 8 | 4 | 4 | N/A | N/A | 8 |

| 8 | Unemployment rate (according to the methodology of the International Labor Organization/ %) | N/A | 5.6 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 6 | 4.7 |

| 9 | The coefficient of migration rate of the population per 1000 people | -5.9 | -6 | -5.1 | -3.8 | -3 | -1 |

| 10 | Spending on research and development (million rubles) | 4068 | 3392 | 4421 | 4606 | 4781 | 5264 |

| 11 | Share of the population that are active Internet users in the total population (%) | 82.9 | 82.9 | 88.4 | 88.5 | 88.6 | 90.3 |

| 12 | The number of pupils in organizations engaged in educational activities for educational programs of preschool education, supervision and care of children | 154415 | 158399 | 159295 | 161376 | 166295 | 160996 |

| 13 | The length of public roads (km) | 5642.9 | 5970.1 | 6230.8 | 7309.3 | 9079.9 | 14413.6 |

| 14 | The number of reindeer (agricultural organizations that are not related to small businesses) | 210014 | 350491 | 564509 | 547580 | 476548 | 524348 |

| 15 | Commissioning of | N/A | 494 | 3 | 401 | 59 | 80 |

| environmental facilities (Wastewater treatment) | |||||||

| plants, thousand m3 per day) | |||||||

| 16 | Commissioning of General educational organizations (student desks from building and reconstruction) | 1003 | 510 | 720 | 865 | 0 | 2980 |

| 17 | Rate of natural population growth in the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation (per 1000 people) | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 | -1 | -3.6 |

| 18 | Number of employees performing research and development | 3615 | 3023 | 3291 | 3302 | 3315 | 3304 |

| 19 | Commissioning of hospital organizations (number of beds from building and reconstruction) | 0 | 24 | 240 | 0 | 7 | 335 |

| 20 | Current (operational) costs of environmental protection in the Arctic zone Russian Federation for the year/ million rubles | N/A | 32132.9 | 32281.1 | 38146.1 | 38691.8 | 36577.1 |

| 21 | The total area of the housing stock, on average, per inhabitant of the land territories of the Arctic zone Russian Federation (square meters) | N/A | 24.9 | 24.4 | 24.3 | 25 | 25.3 |

| 22 | Assessment of the permanent population of the land territories of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation on an average per year (Countryside and Urban) | 2374945 | 2411003 | 2401965 | 2435369 | 2612242 | 2599316 |

| – Countryside | 2120864 | 2143653 | 2135925 | 2142074 | 2263076 | 2256464 | |

| – Urban | 254081 | 267350 | 266040 | 293295 | 349166 | 342852 | |

| 23 | Commissioning of gas wells (unit) | N/A | 250 | 238 | 290 | 291 | 494 |

| 24 | Commissioning of new oil wells (unit) | N/A | 699 | 752 | 670 | 860 | 902 |

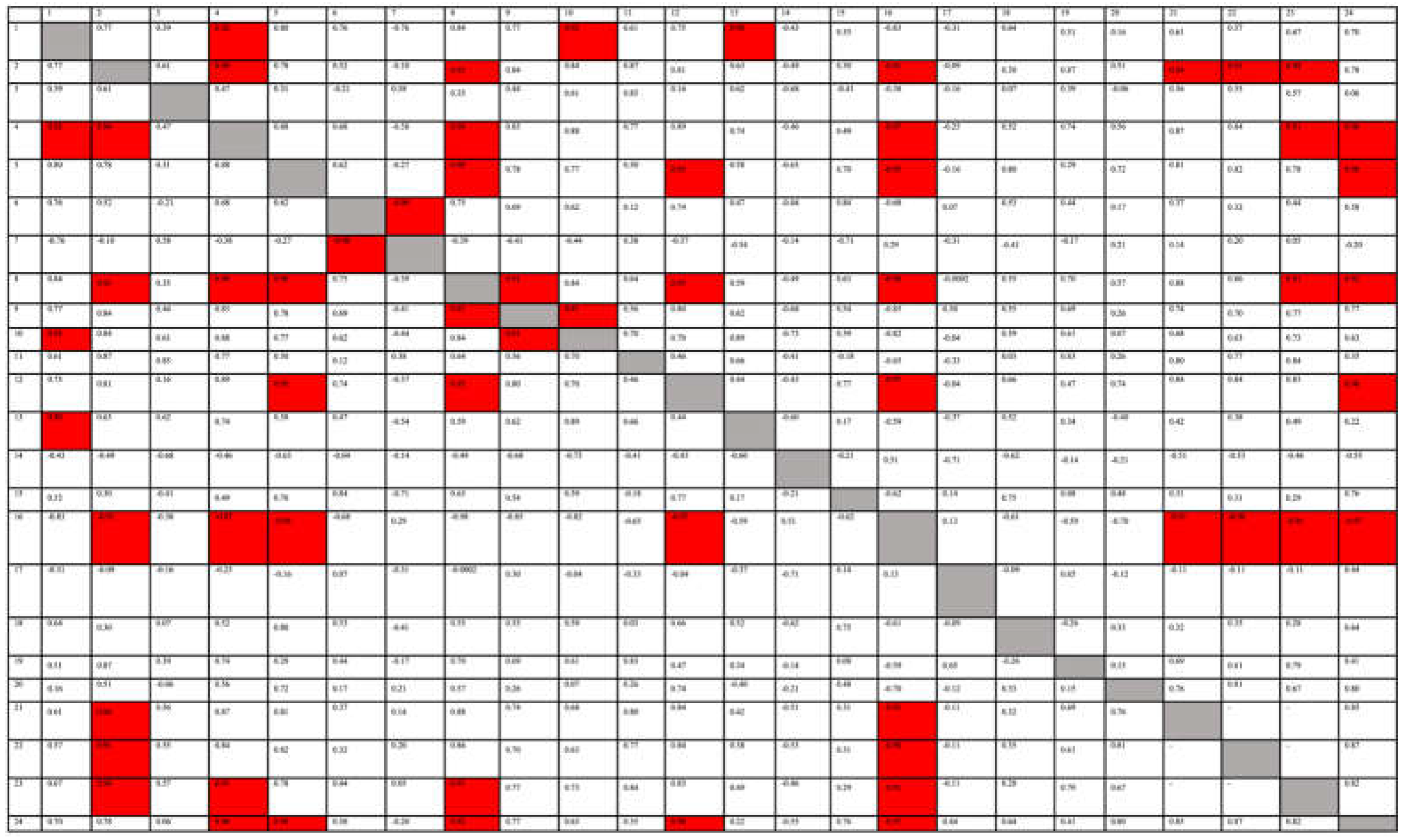

| No | Metric |

|---|---|

| 1 | GRP |

| 2 | Household consumption |

| 3 | Investments |

| 4 | Retail revenue |

| 5 | Revenue of organizations |

| 6 | Balanced financial result |

| 7 | Unemployment rate |

| 8 | The coefficient of migration rate |

| 9 | Spending on research and development |

| 10 | Share of the population that are active Internet users |

| 11 | The number of pupils in organizations engaged in educational activities |

| 12 | The length of public roads |

| 13 | The number of reindeers |

| 14 | Commissioning of environmental facilities |

| 15 | Commissioning of General educational organizations |

| 16 | Rate of natural population growth |

| 17 | Number of employees performing research and development |

| 18 | Commissioning of hospital organizations |

| 19 | Current (operational) costs of environmental protection |

| 20 | The total area of the housing stock |

| 21 | The number of the residential population |

| 22 | The number of the residential population: Urban |

| 23 | The number of the residential population: Countryside |

| 24 | Commissioning of oil and gas wells |

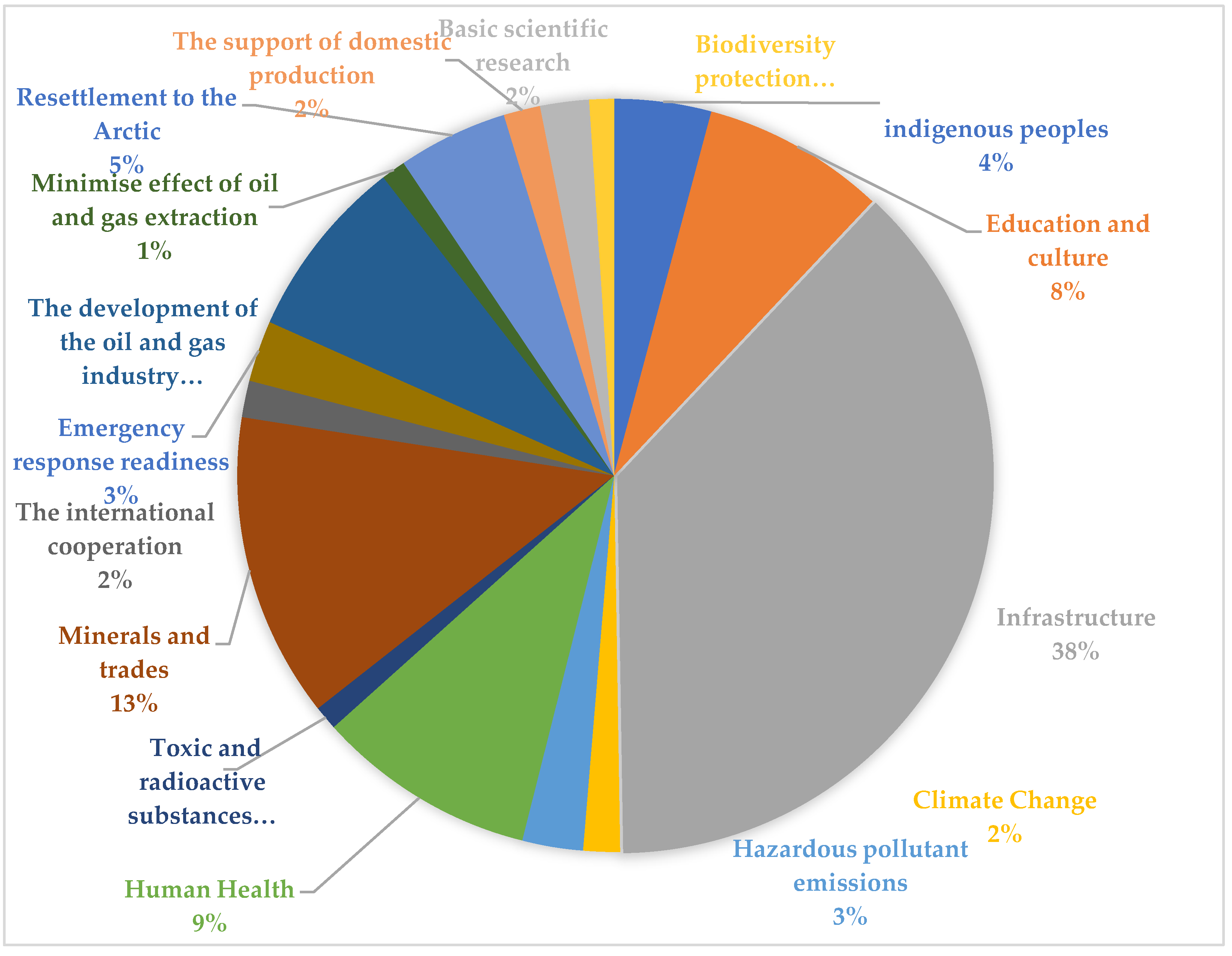

| Categories for measures |

Examples of proposed measures | Total number of proposed measures |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous people | Ensure the preservation and promotion of cultural heritage; providing indigenous peoples with mobile sources of energy supply; promoting the comprehensive development of the young generation of indigenous peoples | 6 |

| Education and culture | Improve the availability of general education; establish in the Arctic branches of federal universities; build sports facilities | 10 |

| Infrastructure | Build roads, airports, railway facilities; create infrastructure for sea ports and new shipping routes; | 66 |

| Climate Change | An adaptation of the economy and infrastructure of the Arctic zone to climate change; The development of a unified system of state environmental monitoring | 3 |

| Hazardous pollutant emissions |

The minimization of emissions into the atmospheric air, discharges into water bodies; The state support for activities in the field of waste management in the Arctic zone | 5 |

| Human health | The modernisation of primary health care; disease prevention measures; state financing of medical care, taking into account the low population density | 17 |

| Toxic and radioactive substances |

The prevention of highly toxic and radioactive substances entering the Arctic zone from the abroad; A regular assessment of the environmental consequences of anthropogenic impact on the environment caused by the transfer of pollutants from the states of North America, Europe and Asia | 2 |

| Minerals and trades | The development of minerals, state support and private investments; The provision of state support to projects for the creation of fish processing complexes, greenhouses, livestock complexes | 25 |

| International cooperation |

The development of general principles for the implementation of investment projects with the participation of foreign capital; Ensuring the implementation of the Agreement to strengthen international Arctic scientific cooperation; An active participation in the work of the AC and other international forums | 3 |

| Emergency response readiness |

The development of technologies, creation of technical means and equipment for carrying out emergency rescue operations and extinguishing fires; The development of Arctic complex emergency rescue centres; Increasing the level of security of critical and potentially dangerous facilities | 5 |

| The development of oiland gas industry | An introduction of a special economic regime that facilitates the implementation of private investment in geological exploration in the Arctic; The preparation of materials necessary to substantiate the outer limit of the continental shelf; The provision of state support measures aimed at the creation and development of technologies for the development of oil and gas fields | 14 |

| Minimise an effect of oil and gas extraction |

The prevention of negative environmental consequences during the extraction of natural resources; Ensuring the rational use of associated petroleum gas in order to minimize its flaring | 2 |

| Resettlement to the Arctic from other regions of the Russian Federation |

Programs for providing settlers with the land; Financial benefits for migrants | 9 |

| Support of domestic production |

Stimulate the use of Russian-made industrial products | 3 |

| Basic scientific research |

Support fundamental and applied scientific research | 4 |

| Biodiversity protection |

The creation of specially protected natural areas; state support for the intensification of forest’s reforestation, the development of aviation to protect forests from fires | 2 |

| Number | Association | Type of association |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | GRP – The number of reindeer | Positive |

| 2. | Household consumption – The coefficient of migration rate | Positive |

| 3. | Household consumption – Rate of natural population growth | Negative |

| 4. | The length of public roads – Rate of natural population growth | Negative |

| 5. | The length of public roads – Revenue of organizations | Positive |

| 6. | The length of public roads – The coefficient of migration rate | Positive |

| 7. | Rate of natural population growth – Revenue of organizations | Negative |

| 8. | Rate of natural population growth – The coefficient of migration rate | Negative |

| 9. | Rate of natural population growth – Commissioning of oil and gas wells | Negative |

| 10. | The coefficient of migration rate – Commissioning of oil and gas wells | Positive |

| 11. | Revenue of organizations – Commissioning of oil and gas wells | Positive |

| Composite indexes | Specific indicators |

|---|---|

| Adaptability index |

Production methods 1. Households producing goods only for their own needs compared with households selling their products (% of the total households studied); 2. The revenue of households from selling the goods they produced (rubles); 3. Household connection to electricity networks (%); 4. Household distance from roads (km); 5. Number of motorboats in fishery households (units); 6. Fisheries mechanisation power/ fish outputs (Watts/ tons); 7. Reindeer farm mechanization power/ number of reindeers (Watts/livestock capita); 8. How the overall sea hunting area divided between households; 9. Monthly household spending on purchasing food (rubles); 10. Access to electricity (% of population); 11. Gasification of households (% of population); 12. Type of electricity source (e. g., batteries). Seasonal lifestyle 13. Access of households to climate information and agro-advisory services (% of households); 14. The number of households using traditional weather and climate forecasting knowledge in daily life (% of households); 15. Reindeer movements from one pasture to another (days); 16. Flooding situation (days and square kilometres affected); 17. Reindeer pastures (square kilometres/ livestock capita); 18. Livestock affected by rabies (%); 19. Sea / river level (meters at different months). Household livelihood strategies 20. Number of households involved in traditional economic activities: fishing, hunting, reindeer breeding compared with overall number of households (%); 21. Gender distribution in performing traditional economic activities (overall number) (%); 22. Head of the household (gender); 23. Level of education (years at school and higher education institutions); 24. Vehicles per households (units); 25. Household members migrating for work to other regions in Russia as a proportion to households where all members live together (%); 26. Households where children are involved in traditional economic activities (%); 27. Primary food provider (gender); 28. Households who gave up nomadic life style in favour to other economic activities (% of households); 29. Access to the internet (hours spend online per day). Usage of cash 30. Households create handicrafts for obtaining cash (% of households); 31. How often households purchasing goods from the mainland (times per year); 32. Households involved in barter activities (%); 33. Representation of banks at the cities within access for indigenous villages (units). |

| Self-Identity index |

Indigenous membership 34. Population involved in activities of indigenous people’s organizations (% of population); 35. Annual cross-community indigenous activities which are performed regularly (number of activities and people participated); 36. The existence of tribal membership criteria (types and number of criteria); 37. People’s self-description, whether as “indigenous” or “Russian” (% of population); 38. Community acceptance of non-indigenous representatives (low/high); Rights to land 39. Gender differences with secure rights to land (%); 40. Percentage of households who have any documented evidence of their properties and land (%); 41. Percentage of households who were forced to change their original place of living within last 40 years (%); 42. The level of protection of indigenous rights to land (number of legal documents which secure indigenous rights to their land); 43. Households that have secure access to fishery areas and/or reindeer pastures (% of households). Usage of native language 44. People who use native language in everyday communication (% to the whole population); 45. Evidence of written material in native language (number of evidences/ documents); 46. Study of native language at school (studying hours per months for pupils); 47. Young people use native language in everyday communication (% of young people under 18); 48. People using Russian language as a primary language (% to the whole population); 49. People who can write in native language (% to the whole population); 50. People who can speak at least two languages (% to the whole population). Application of traditional knowledge 51. Use of indigenous knowledge in routine life: e. g. food storage, waste treatment vs conventional knowledge (number of examples); 52. An application of traditional medicine (number of examples/ household); 53. Use of indigenous knowledge and conventional knowledge in organising nomadic activities (% of examples); 54. Households involved in traditional crafting (% of households); 55. Transmission of indigenous knowledge through generations (% of young people under 18 and older population who declare to use indigenous knowledge in everyday life); 56. Oral and written traditional cultural materials; 57. Evidence of application of copyrights to indigenous knowledge; 58. National-level legislation for the protection of indigenous knowledge (number of examples). |

| Health index |

Health self-perception 59. Rating of self-perceived health status (males/females; children under 18; 25-34 years old; 35-44 years old; 45-54 years old; 55-64 years old; 65+ years old); 60. People report having long-term chronic health problems (% of population); 61. Rating of self-perceived health status by people with different education levels (1 to 5 ratings). Changes in morbidity specific to indigenous population 62. An assessment of Northern-specific diseases: hypertension, urolithiasis, diseases of the musculoskeletal system (% of the population); 63. Infants’ health development assessment 64. The distance from indigenous communities to the nearest hospitals (km); 65. Alcoholism by gender (% to the population); 66. Infectious diseases (the correlation number between temperature changes, sea level rise and % of population affected by infectious diseases); 67. Mortality rates (age groups, male/females); 68. Injury incidence (% of all hospitals admission); 69. Suicide incidence (number of declared cases). |

| Capacity index |

Representation at the government 70. Indigenous people in the regional government (%); 71. Indigenous people in the federal government (%); 72. Russian indigenous people in international indigenous organizations (%); 73. The existence of indigenous people’s organizations (number of organizations); 74. Population participating in elections (% of population); 75. The existence of self-government in local communities (number of examples); 76. The communication between communities’ local council or the elders and local authorities (number of cases during the year). Intercommunity social links 77. Product exchange between different communities (rubles); 78. Knowledge exchange between communities (number of examples); 79. Existing routes between different communities (total length in km); 80. Intercommunity social events (number of examples). Participation in the market economy 81. Number of working migrants in households (people); 82. Revenue of households (rubles/year); 83. Monthly spendings of households (rubles); 84. Examples of selling goods beyond the Arctic Region (rubles). Education structure 85. Classroom time for pupils from indigenous communities (hours); 86. Accessibility of schools (km from indigenous communities); 87. Availability of transport for sending indigenous pupils to schools (units); 88. Access to internet learning (number of available programs); 89. Access to internet (% of households); 90. Indigenous population in colleges (% of the young population); 91. Indigenous population with higher education (% of young people enrolled in universities programs); 92. Branches of Universities in Arctic regions (universities in Arctic cities as a proportion to the local population (indigenous and non-indigenous); 93. Indigenous people involved in research and development (% of population); 94. People involved in sustainable development education programs (% of the population). |

| Ecological Index |

Methods to deal with waste 95. Waste reduction by implementation of specific community practices: sharing items, avoiding waste (% of waste reduced by implementing special practices); 96. Combination of conventional and indigenous waste treatment practices (% of waste covered by combined waste treatment practices); 97. Landfills (square meters). Natural resource management Communities’ natural resources management strategies; 98. Federal funding to support indigenous natural resource management strategies (rubles); 99. Indigenous rights to the land with specific natural resources (number of documents). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).