Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Machine learning is revolutionizing the way we work and the field of occupational health and safety (OHS) has significant knowledge gaps for its implementation. This review synthesizes current applications across hazard identification, risk assessment, ergonomics, PPE compliance monitoring, and environmental surveillance, while identifying critical areas for future research. Even with promising advances, challenges persist in developing machine learning models that work effectively across industries, integrate multi-modal data streams, and adapt to dynamic work environments. Key limitations include the need for more robust assessment tools, personalization capabilities, and solutions to data quality and privacy concerns. The field particularly lacks standardized frameworks for data collection and sharing, as well as clear ethical guidelines for implementing machine learning in workplace safety contexts. This analysis reveals promising research directions, including the development of explainable AI systems to support OHS decision-making, learning applications to address data scarcity, and privacy-preserving learning approaches. The integration of machine learning with internet-of-things (IoT) and extended reality technologies offers additional avenues for innovation. Advancing these opportunities requires interdisciplinary collaboration between OHS professionals, computer scientists, lawyers, and subject matter experts. This review concludes that realizing the full potential of machine learning in OHS depends on addressing both technical and organizational challenges. A focus on these identified research priorities in this field can make significant advances toward creating more effective, data-driven tactics to workplace safety and health management.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

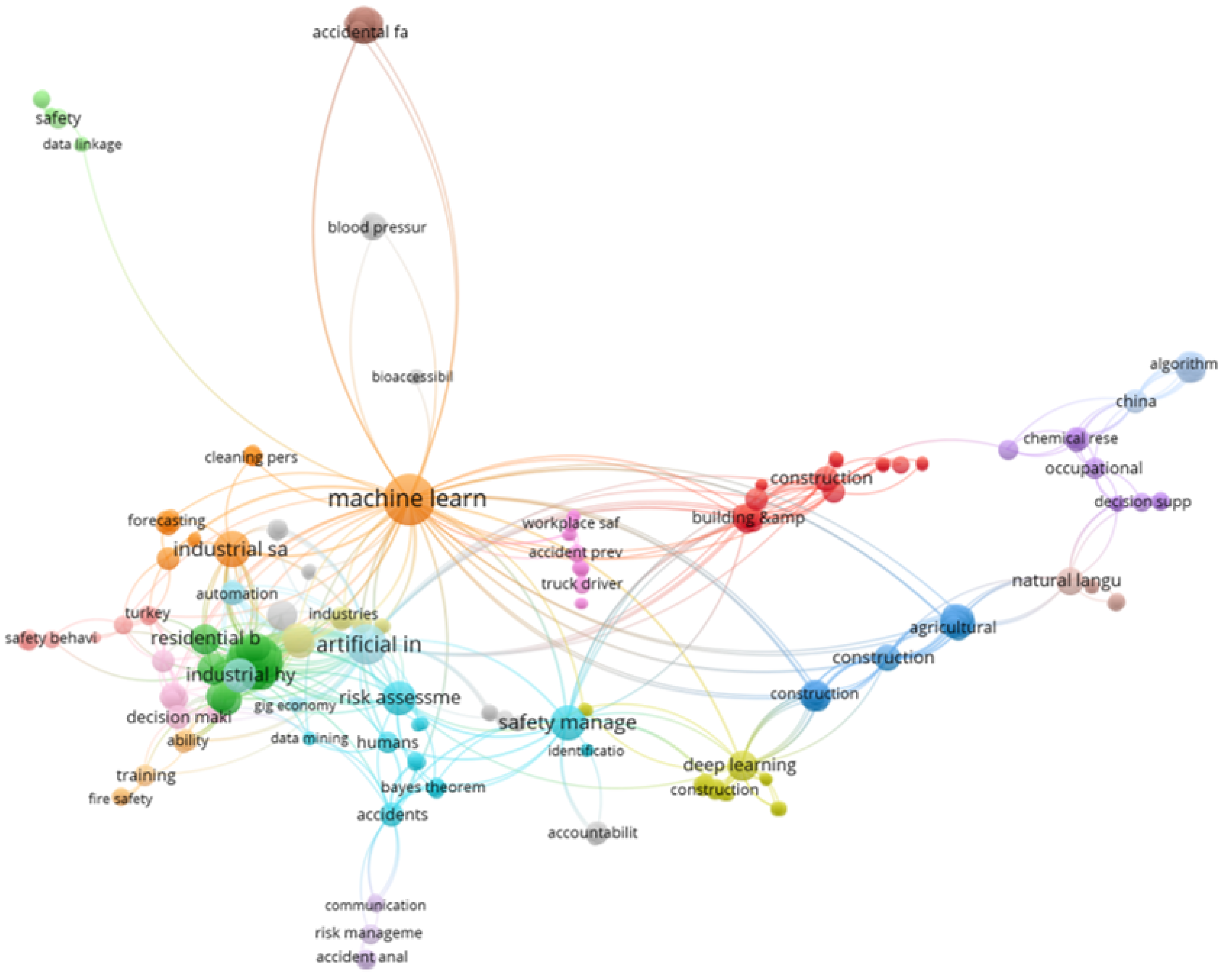

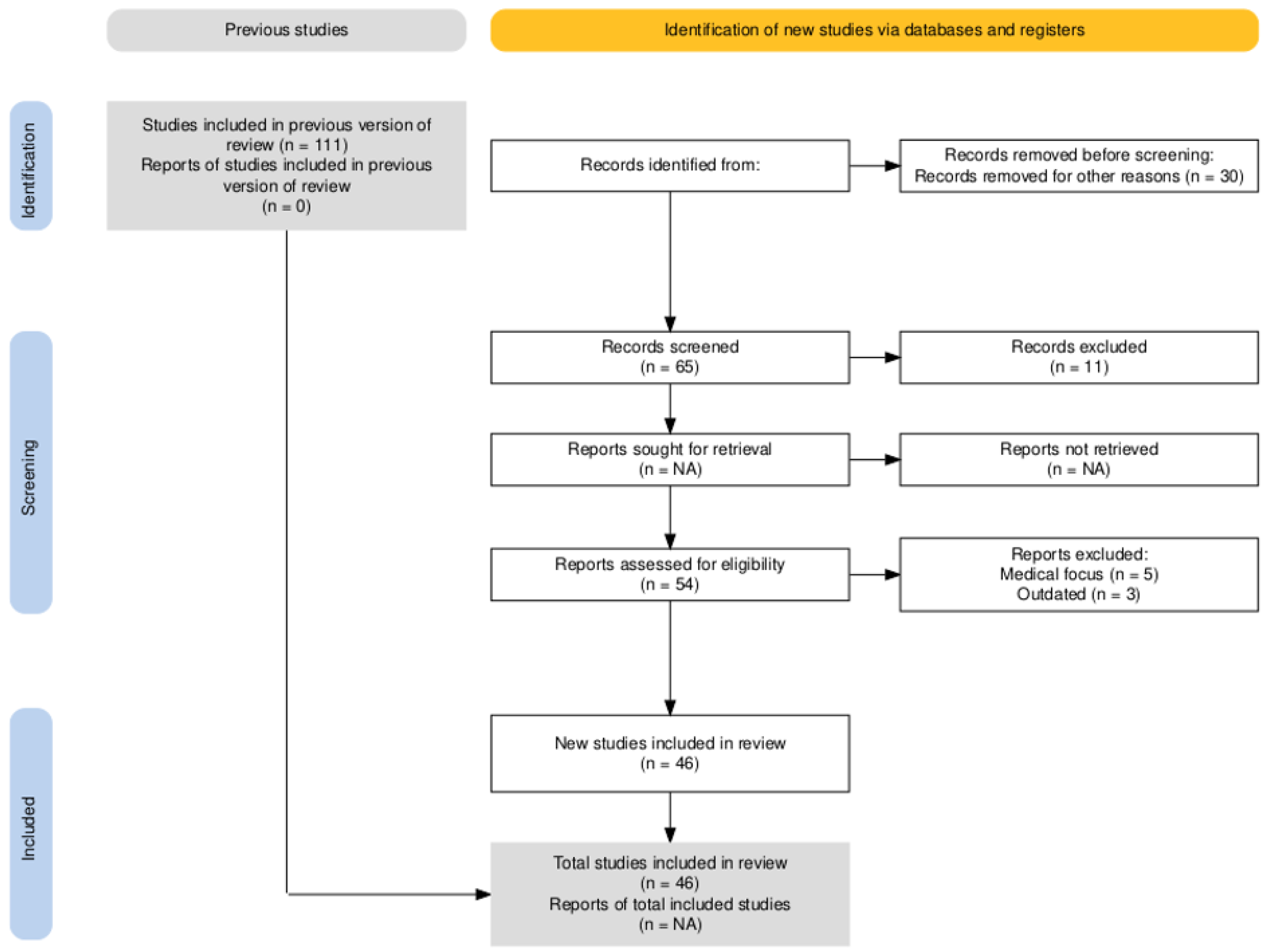

2. Methodology

2.1. Objectives

2.2. Screening Process

3. Results

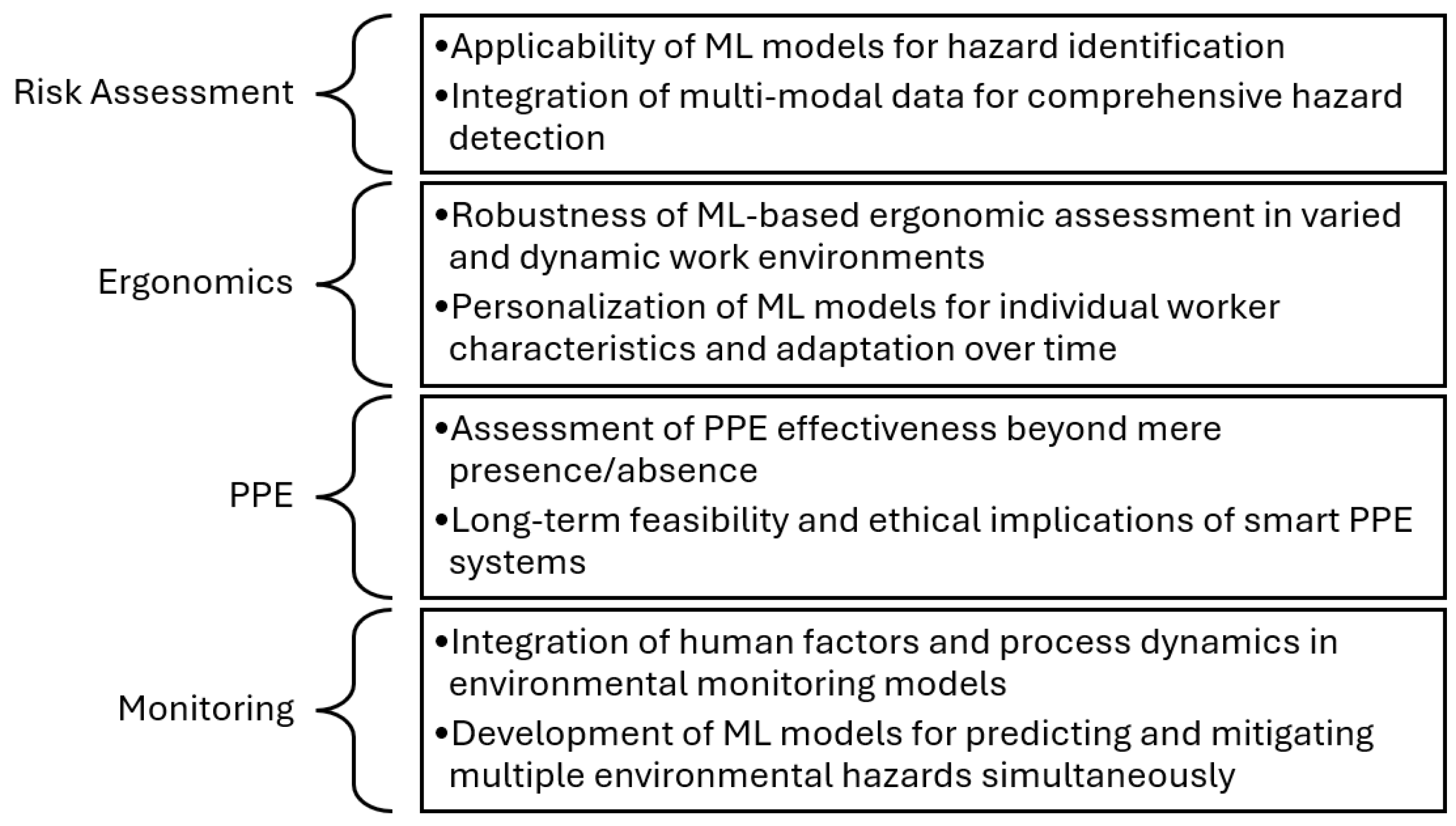

3.1. Applications for Machine Learning in OHS and Associated Knowledge Gaps

3.1.1. Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

3.1.2. Ergonomics and Biomechanics

3.1.3. Personal Protective Equipment Compliance

3.1.4. Environmental Monitoring

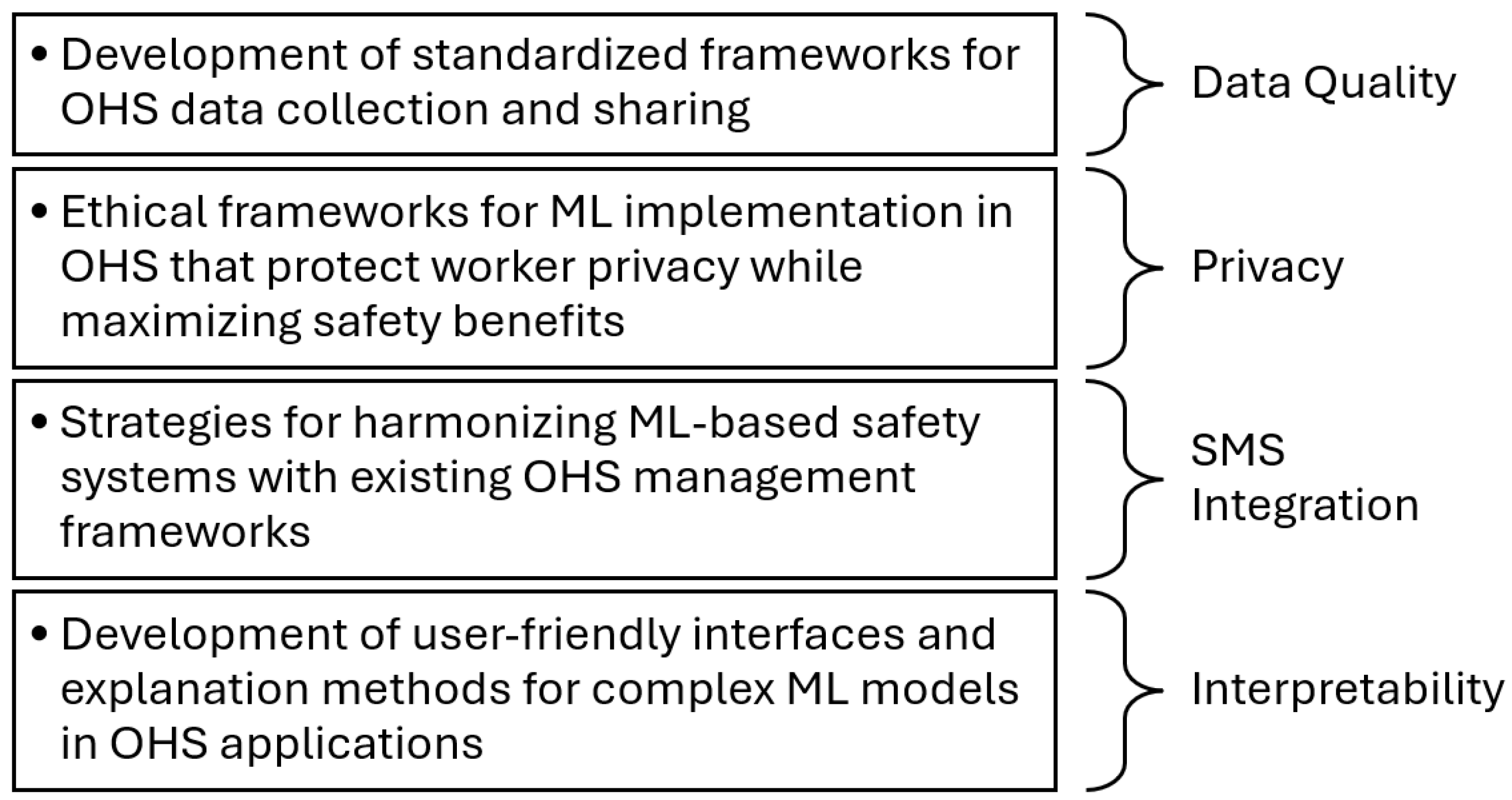

3.2. Challenges, Limitations, and Associated Knowledge Gaps

3.2.1. Data Quality and Availability

3.2.2. Privacy Concerns and Ethical Considerations

3.2.3. Integration with Existing OHS Management Systems

3.2.4. Interpretability of Complex Machine Learning Models

3.3. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

3.3.1. Integration of Machine Learning with Internet of Things (IoT)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020 : An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Helaly, M. Artificial Intelligence and Occupational Health and Safety, Benefits and Drawbacks. La Medicina del Lavoro | Work, Environment and Health 2024, 115, e2024014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.; Zhong, B.; Zhao, N.; Love, P.E.; Luo, H.; Xue, J.; Xu, S. A deep learning-based approach for mitigating falls from height with computer vision: Convolutional neural network. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2019, 39, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.; Morgado-Dias, F. Deep Learning-Based Automatic Safety Helmet Detection System for Construction Safety. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jing, X.; Zhu, Q.; Du, W.; Wang, X. Automatic Construction Hazard Identification Integrating On-Site Scene Graphs with Information Extraction in Outfield Test. Buildings 2023, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Lin, Q.; Chen, Y. A vision-based method for automatic tracking of construction machines at nighttime based on deep learning illumination enhancement. Automation in Construction 2021, 127, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Dong, M.; Fang, T. Automatic detection of falling hazard from surveillance videos based on computer vision and building information modeling. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2022, 18, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrizi, R.; Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Metaxas, D.; Li, K. A computer vision based method for 3D posture estimation of symmetrical lifting. Journal of Biomechanics 2018, 69, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, W. Smart wearable insoles in industrial environments: A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics 2024, 118, N.PAG–N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodoo, J.E.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Lonsdale, M.; Alalwan, N. Digital Innovations for Occupational Safety: Empowering Workers in Hazardous Environments. Workplace Health & Safety 2024, 72, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, G.; Valles, D.; Wierschem, D.C.; Koldenhoven, R.M.; Koutitas, G.; Mendez, F.A.; Aslan, S.; Jimenez, J. Machine Learning Techniques for Motion Analysis of Fatigue from Manual Material Handling Operations Using 3D Motion Capture Data. 2020 10th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2020; pp. 0300–0305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Fuentes, A.; Busto Serrano, N.M.; Sánchez Lasheras, F.; Fidalgo Valverde, G.; Suárez Sánchez, A. Work-related overexertion injuries in cleaning occupations: An exploration of the factors to predict the days of absence by means of machine learning methodologies. Applied Ergonomics 2022, 105, N.PAG–N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendran, A.; McSharry, J.; Meade, O.; Meredith, D.; McNamara, J.; Bligh, F.; O’Hora, D. Barriers and facilitators to adopting safe farm-machine related behaviors: A focus group study exploring older farmers’ perspectives. Journal of Safety Research 2024, 90, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, N.D.; Behzadan, A.H.; Paal, S.G. Deep learning for site safety: Real-time detection of personal protective equipment. Automation in Construction 2020, 112, 103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.; Bao, Q.L.; Hussain, R.; Soltani, M.; Pham, H.C.; Park, C. Learning from construction accidents in virtual reality with an ontology-enabled framework. Automation in Construction 2024, 166, 105597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edirisinghe, R. Digital skin of the construction site: Smart sensor technologies towards the future smart construction site. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2019, 26, 184–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowicz, W.; Barata, J.; Rupino da Cunha, P. Business Information Systems: 22nd International Conference, BIS 2019, Seville, Spain, June 26-28, 2019, Proceedings, Part I; Number v.353 in Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing Ser, Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, 2019.

- Dhingra, S.; Madda, R.B.; Gandomi, A.H.; Patan, R.; Daneshmand, M. Internet of Things Mobile–Air Pollution Monitoring System (IoT-Mobair). IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 5577–5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.N.; Medvedovsky, K.; Zuidema, C.; Peters, T.M.; Koehler, K. Probabilistic Machine Learning with Low-Cost Sensor Networks for Occupational Exposure Assessment and Industrial Hygiene Decision Making. Annals of Work Exposures & Health 2022, 66, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, L.P.; Griffin, C.R.; Finn, J.T.; Prescott, R.L.; Faherty, M.; Still, B.M.; Danylchuk, A.J. Warming seas increase cold-stunning events for Kemp’s ridley sea turtles in the northwest Atlantic. PLoS ONE 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, G.; Antwi-Afari, M.F. Recognizing sitting activities of excavator operators using multi-sensor data fusion with machine learning and deep learning algorithms. Automation in Construction 2024, 165, 105554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, B.; Luo, Y.; Li, T.; Han, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, B. Water-Richness Zoning Technology of Karst Aquifers at in the Roofs of Deep Phosphate Mines Based on Random Forest Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, null–null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, A.; Klambauer, G.; Unterthiner, T.; Hochreiter, S. DeepTox: Toxicity Prediction using Deep Learning. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, A.; Ozturk, P.; Chau, K.w. Flood Prediction Using Machine Learning Models: Literature Review. Water 2018, 10, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, D.W. Decision support: using machine learning through MATLAB to analyze environmental data. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2019, 9, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, B.; Park, S.K.; Zhao, Z. Construction of environmental risk score beyond standard linear models using machine learning methods: application to metal mixtures, oxidative stress and cardiovascular disease in NHANES. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source 2017, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yin, K.; Cao, Y.; Intrieri, E.; Ahmed, B.; Catani, F. Displacement prediction of step-like landslide by applying a novel kernel extreme learning machine method. Landslides 2018, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Yang, X.; Xing, X.; Wang, J.; Umer, W.; Guo, W. Real-Time Monitoring of Mental Fatigue of Construction Workers Using Enhanced Sequential Learning and Timeliness. Automation in Construction 2024, 159, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.; Xu, X.; Ni, X.; Ma, S.; Guo, L. Fall-risk assessment of aged workers using wearable inertial measurement units based on machine learning. Safety Science 2024, 176, 106551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.; Bansal, P.; Buddhavarapu, P. A new spatial count data model with Bayesian additive regression trees for accident hot spot identification., 2020. Published: $howpublished.

- Kumar, L.S.; Burns, G.N. Determinants of safety outcomes in organizations: Exploring O*NET data to predict occupational accident rates. Personnel Psychology 2024, 77, 555–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheronnaghsh, S.; Zolfagharnasab, H.; Gorgich, M.; Duarte, J. Machine learning in Occupational Safety and Health - a systematic review: Review. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Safety 2023, 7, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, D. Workforce Diversity and Occupational Hearing Health. Safety 2023, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.M.; Chang, J.H.; Indrayani, N.L.D.; Wang, C.J. Machine learning approach to determine the decision rules in ergonomic assessment of working posture in sewing machine operators. Journal of Safety Research 2023, 87, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tixier, A.J.P.; Hallowell, M.R.; Rajagopalan, B.; Bowman, D. Application of machine learning to construction injury prediction. Automation in Construction 2016, 69, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadhari, R.K.; Rabiee, M.; Khanzode, V.; Murthy, S.; Tarei, P.K. From unstructured accident reports to a hybrid decision support system for occupational risk management: The consensus converging approach. Journal of Safety Research 2024, 89, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Park, J.; Seo, M.B.; Yi, J.S. Graph-based intelligent accident hazard ontology using natural language processing for tracking, prediction, and learning. Automation in Construction 2024, 168, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodie, M.T. The law and policy of people analytics. University of Colorado Law Review 2017, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Cagno, E.; Accordini, D.; Neri, A.; Negri, E.; Macchi, M. Digital solutions for workplace safety: An empirical study on their adoption in Italian metalworking SMEs. Safety Science 2024, 177, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zeng, J.; Chen, C.; Li, T.; Ma, J. Decentralized adaptive work package learning for personalized and privacy-preserving occupational health and safety monitoring in construction. Automation in Construction 2024, 165, 105556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, A.; Boudreau-Trudel, B.; Souissi, A.S. Occupational health and safety in the industry 4.0 era: A cause for major concern? Safety Science 2018, 109, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable machine learning: a guide for making black box models explainable, second edition ed.; Christoph Molnar: Munich, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, J. Prompt-based automation of building code information transformation for compliance checking. Automation in Construction 2024, 168, 105817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.F.; Katsikas, S.; Beltramello, O.; Hadjiefthymiades, S. Augmented and virtual reality based monitoring and safety system: A prototype IoT platform. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2017, 89, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szóstak, M.; Mahamadu, A.M.; Prabhakaran, A.; Pérez, D.C.; Agyekum, K. Development and testing of immersive virtual reality environment for safe unmanned aerial vehicle usage in construction scenarios. Safety Science 2024, 176, 106547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).