Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

02 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Previous Work

1.2. Problem Statement

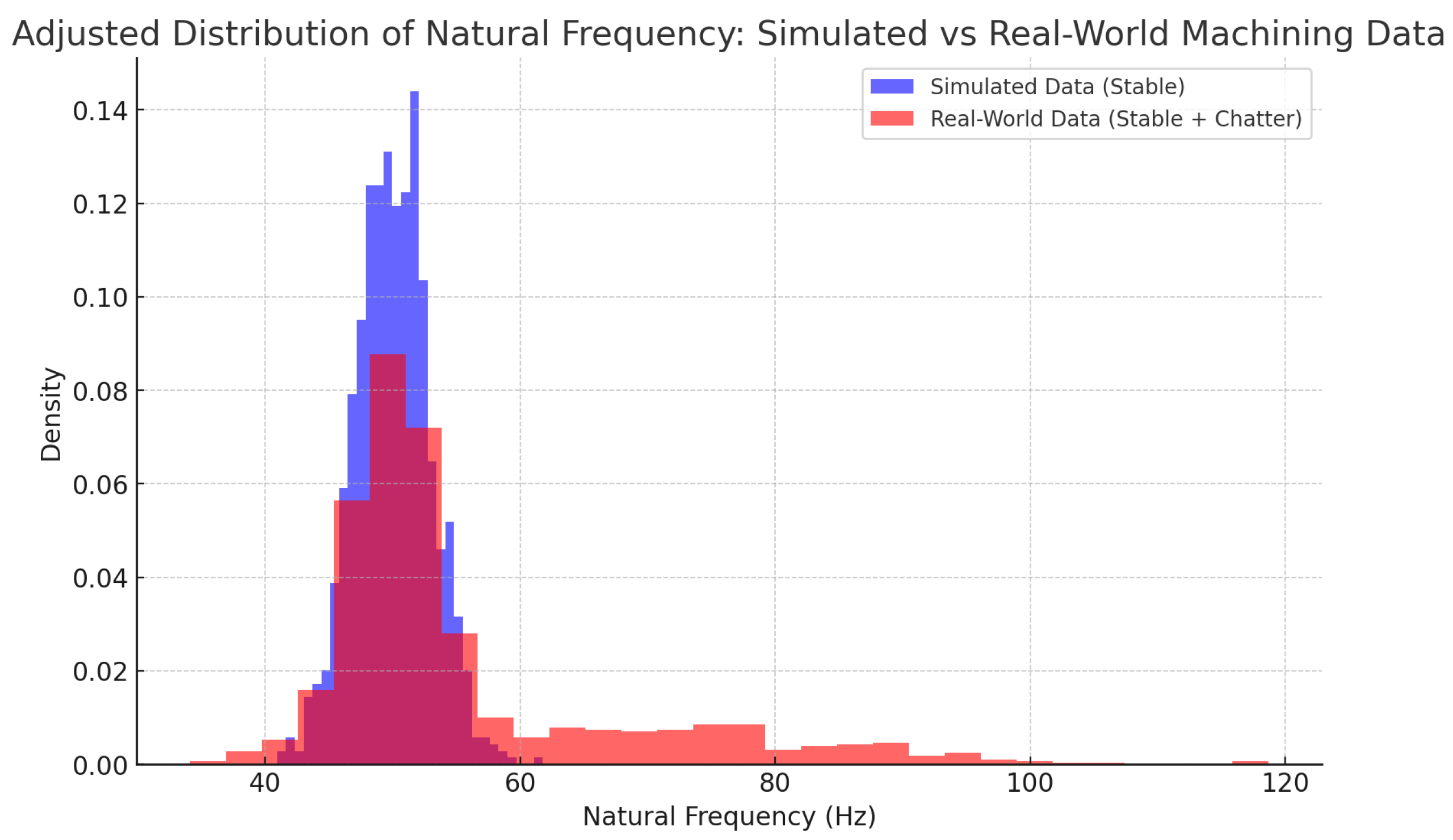

- Data Discrepancies: Differences in data distributions between simulated and real-world datasets can lead to reduced model performance due to issues like covariate shift and sample selection bias [18].

- Sensor Noise and Data Quality: Real-world data are susceptible to various types of noise and artifacts that are typically absent in simulated data, necessitating advanced preprocessing and noise reduction techniques [19].

- Feature Relevance: Features that are significant in simulated environments may not hold the same importance in real-world settings, requiring reevaluation of feature selection and extraction methods [20].

- Model Generalization: Ensuring that the model generalizes well to unseen real-world data is essential for practical applicability, highlighting the need for model adaptation and validation strategies [14].

- Collecting and processing 1,600 real-world machining datasets encompassing a variety of operational conditions.

- Applying the previously trained models to these datasets to assess their predictive performance.

- Identifying discrepancies between simulated and real-world data and their impact on model accuracy.

- Proposing solutions to address these discrepancies, including model adaptation techniques and enhanced feature extraction methods.

1.3. Objectives

- Evaluate Model Performance: Assess the predictive accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC of the models when applied to real-world data, and compare these results with the performance achieved on simulated data.

- Identify and Analyze Discrepancies: Investigate any discrepancies in model performance between simulated and real-world data, analyzing factors such as sensor noise, data variability, and differences in feature distributions.

- Enhance Model Robustness: Propose and implement strategies to improve the models’ robustness and generalizability in real-world applications. This may include advanced data preprocessing techniques, feature engineering, or model adaptation methods such as domain adaptation [21].

- Provide Practical Insights: Offer insights into the challenges and considerations involved in transitioning ML models from simulated to operational environments, contributing to the development of more reliable chatter detection systems in the machining industry.

1.4. Contributions

- Validation of Simulation-Trained Models on Real-World Data: We provide a comprehensive evaluation of ML models trained on simulated machining data when applied to real-world machining operations. This validation assesses the models’ effectiveness in practical settings, addressing a significant gap in existing research [22].

- Analysis of Transition Challenges from Simulation to Reality: By identifying and analyzing the discrepancies between simulated and real-world data, we shed light on the challenges inherent in transferring models across domains. This includes addressing issues related to data distribution differences, noise levels, and feature relevance [23].

- Enhancement of Model Robustness through Adaptation Techniques: We propose and implement strategies to improve the robustness and generalizability of the models in real-world applications. This includes the use of advanced data preprocessing, feature engineering, and model adaptation methods to mitigate the impact of domain discrepancies [24].

- Practical Insights for Industrial Implementation: The findings offer valuable insights for practitioners in the machining industry, providing guidance on deploying ML models for chatter detection in operational environments. This contributes to the development of more reliable and efficient predictive maintenance systems [25].

- Contribution to Machine Learning Methodologies: From a methodological perspective, the study advances the understanding of how ML models can be adapted and validated across different data domains, contributing to the broader field of TL and domain adaptation in industrial applications [26].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Chatter Detection in Machining

2.2. Machine Learning in Machining Processes

2.2.1. Supervised Learning Methods

2.2.2. Unsupervised Learning and Clustering

2.2.3. Deep Learning Approaches

2.2.4. Challenges and Considerations

2.2.5. Application to Chatter Detection

2.3. Simulation vs. Real-World Data

2.4. Gap Identification

- Systematically Evaluate Model Transferability: Few studies have systematically assessed how models trained on simulated data perform when applied to real-world machining operations, identifying the factors that contribute to performance degradation.

- Address Domain Discrepancies: Limited research has been conducted on developing and implementing strategies to mitigate the impact of domain discrepancies between simulated and real-world data in the context of machining processes.

- Provide Practical Implementation Guidelines: There is a need for comprehensive guidelines and best practices for adapting and deploying simulation-trained ML models in industrial settings for chatter detection and machining process monitoring.

3. Methodology

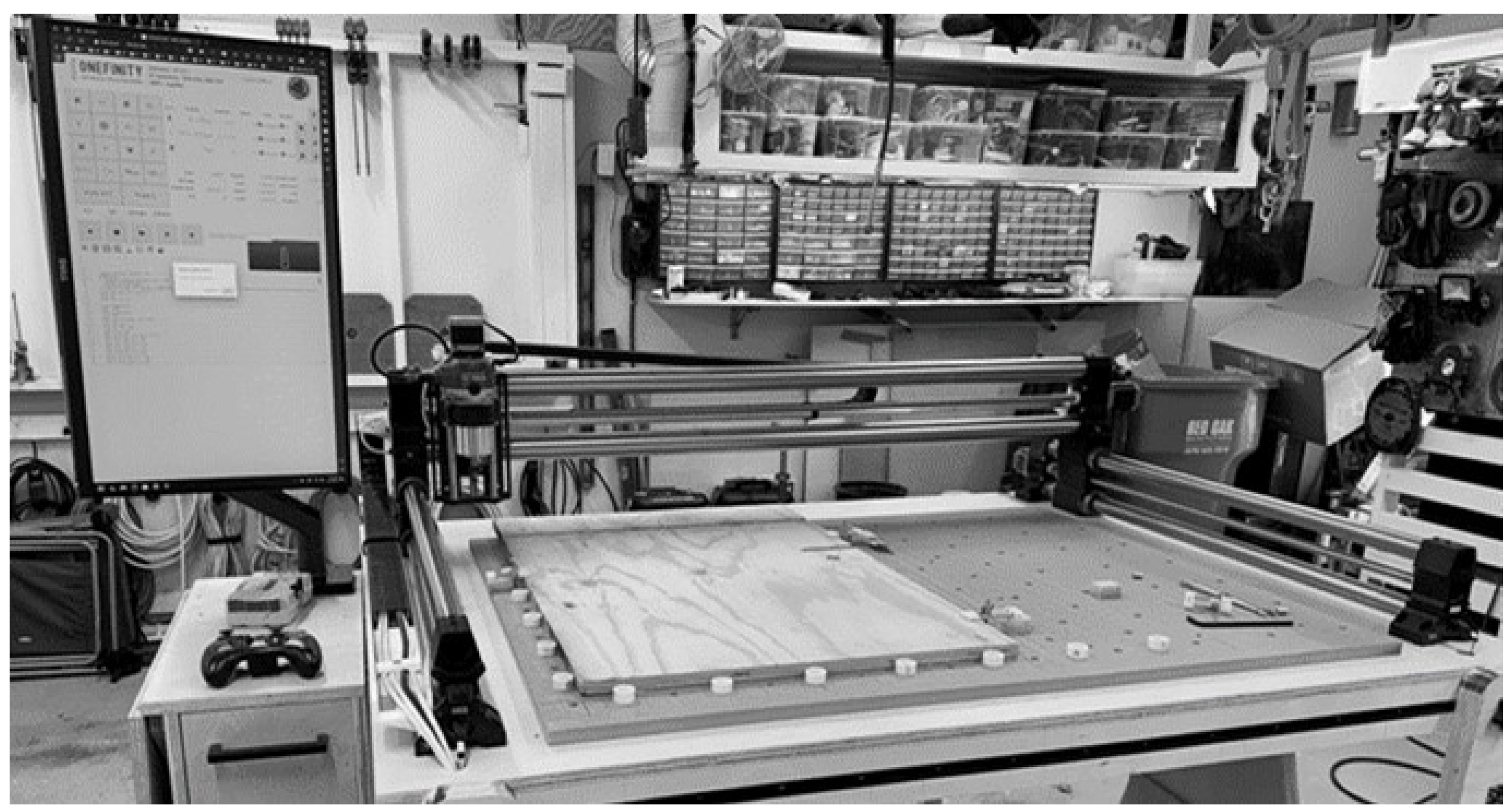

3.1. Real-World Data Collection

3.1.1. Sensor Integration and Data Acquisition

3.1.2. Machining Operations and Data Sampling

-

Materials: Two distinct materials were machined:

- –

- 6061 Aluminum: Known for its machinability and versatility.

- –

- 304 Stainless Steel: Selected for its hardness and resistance to wear.

-

Tool Configurations: Machining was performed using tool heads with varying cutting teeth:

- –

- 2 Cutting Teeth: Representative of standard tool heads.

- –

- 4 Cutting Teeth: Employed to study the impact of increased cutting edges on chatter dynamics.

-

Machining Parameters:

- –

- Spindle Speed: Varied systematically between 8,000 rpm and 10,000 rpm to observe the effects on chatter occurrence.

- –

- Cutting Depth: Adjusted within the range of 1.0 mm to 2.0 mm to analyze its influence on vibration patterns.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.2.1. Noise Reduction

- Low-Pass Filtering: A Butterworth low-pass filter of order 4 with a cutoff frequency of 5 kHz was applied to the vibration signals. This filter effectively attenuates high-frequency noise while preserving the essential characteristics of the machining vibrations [54].

- Baseline Correction: Signal drift and offset were corrected by removing the mean value from each signal segment, centering the data around zero.

- Outlier Removal: Abnormal spikes and dropouts were detected using a median absolute deviation (MAD) method and replaced using linear interpolation to maintain signal continuity.

3.2.2. Signal Segmentation

3.2.3. Normalization

- Amplitude Normalization: Each signal segment was scaled to have unit variance, removing amplitude variations due to differing cutting conditions.

- Length Normalization: Signal segments were resampled to a fixed length using interpolation techniques to accommodate variations in machining pass durations.

3.2.4. Feature Enhancement

- Windowing: Overlapping Hanning windows were applied to each signal segment to reduce spectral leakage during frequency analysis [56].

- Detrending: Linear trends were removed from the signal segments to eliminate low-frequency components unrelated to the machining process.

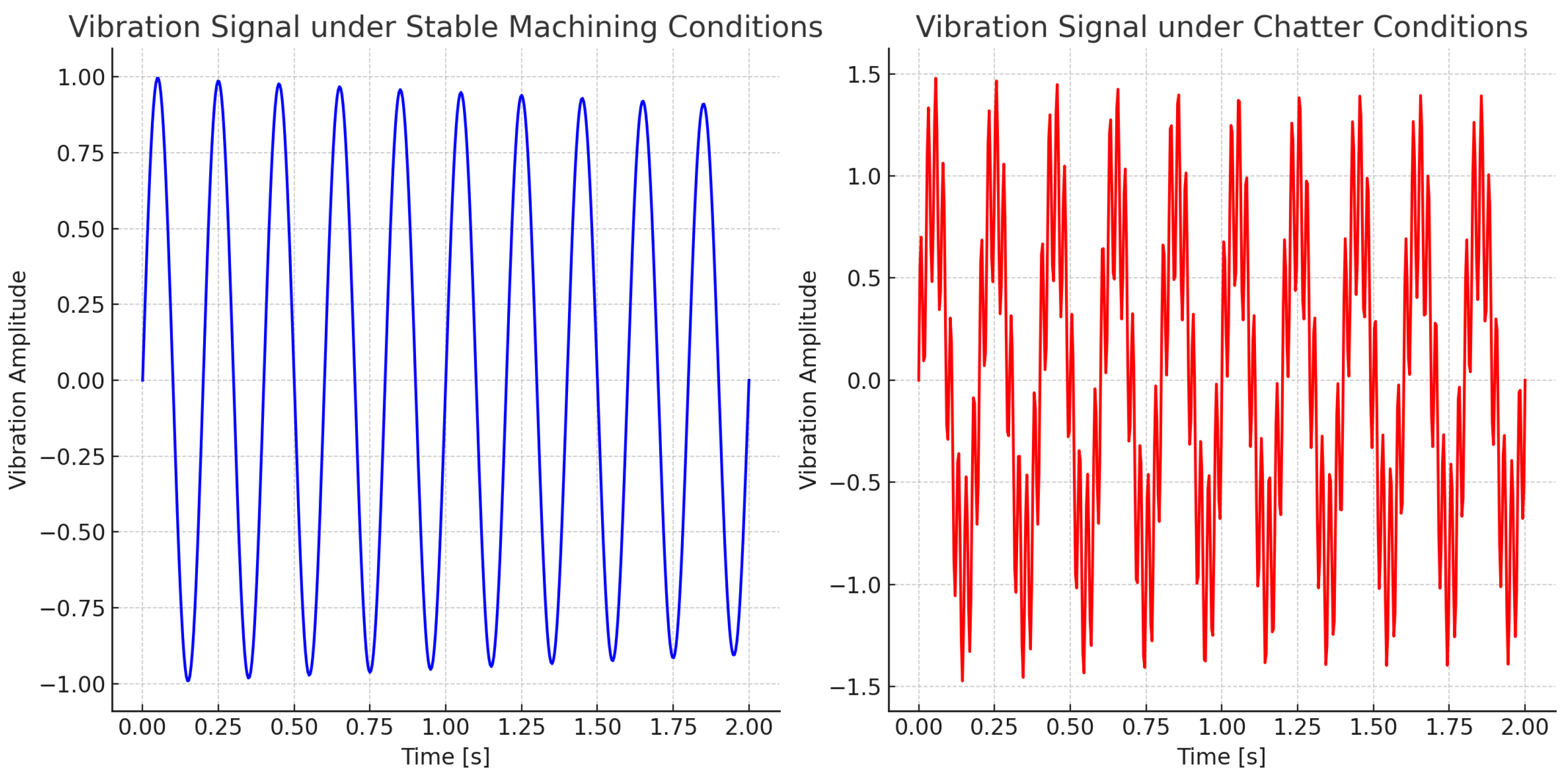

3.2.5. Data Labeling

- Vibration Analysis: High amplitude, irregular vibrations in the signal were indicative of chatter conditions.

- Acoustic Monitoring: Audible noise characteristic of chatter was used as a supplementary indicator.

- Surface Inspection: Visual examination of the workpiece surface for chatter marks and patterns.

3.2.6. Data Partitioning

- Training Set: 10% of the data used for model training.

- Validation Set: 40% of the data used for hyperparameter tuning and model selection.

- Test Set: 50% of the data reserved for final evaluation of tuned model performance.

3.3. Feature Extraction

3.3.1. Time-Series Feature Extraction Using TSFresh

- Ratio value number to time series length: The number of unique values versus the total number of values.

- Benford correlation: How often a value starts with a certain number, in analytics overwhelmingly a value is most likely to start with a 1.

- Change quant f-agg ”var” False qh 1.0 ql 0.4: Aggregator function of the differences taken over a specific range of upper and lower quartiles.

- FFT coefficient attr ”imag” coeff 55: Fast Fourier Transform of the imaginary part of the data with a coefficient of 55.

- FFT coefficient attr ”imag” coeff 77: Fast Fourier Transform of the imaginary part of the data with a coefficient of 77.

- Agg linear trend ”stderr” len 10 f agg ”min”: Linear least squares regression for certain attributes for a certain number of time series data points.

- Permutation entropy dimension 41: Counts the frequency of permutation and returns the appropriate entropy, this is a complexity measure for time series data.

3.3.2. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) Features

- Acceleration Peak (g):

- Acceleration RMS (g):

- Crest Factor:

- Standard Deviation (g):

- Velocity RMS (in/s):

- Displacement RMS (in):

- Peak Frequency (Hz):

- RMS (g) from 1 to 65 Hz:

- RMS (g) from 65 to 300 Hz:

- RMS (g) from 300 to 6000 Hz:

3.3.3. Operational Modal Analysis Features

- Natural Frequencies: The inherent frequencies at which a system naturally oscillates when not subjected to external forces or damping. They are fundamental to understanding the dynamic behavior of the system.

- Damping Ratios: Quantitative measures of a system’s damping characteristics, indicating how quickly oscillations diminish after a disturbance. They describe the rate at which vibrational energy is dissipated.

- Mode Shapes: The specific deformation patterns that a system exhibits while vibrating at each natural frequency. Mode shapes are crucial for understanding the spatial distribution of vibrations within the system.

- Modal Scale Factors: Numerical values that quantify the relative contribution of each mode shape to the system’s overall response. They indicate how much each mode influences the system’s vibration.

- Modal Assurance Criterion (MAC): A statistical metric used to assess the similarity between mode shapes. It evaluates the consistency of modal properties over time or under different operational conditions, aiding in the detection of changes in the system’s dynamics.

3.3.4. Receptance Coupling Substructure Analysis (RCSA) Features

- Frequency Response Functions (FRFs): Functions that describe how different components of a system respond to inputs at varying frequencies. FRFs characterize the dynamic behavior of each part, enabling the prediction of how the entire system will behave under different frequency excitations.

- Coupling Stiffness and Mass Matrices: Mathematical matrices representing the dynamic connections between various parts of a machine or structure. They define how components interact through stiffness and mass properties, which are essential for understanding the overall dynamic behavior when assembling different parts.

- Assembled System FRFs: The Frequency Response Functions of the complete system, obtained by combining the individual FRFs of each component using Receptance Coupling Substructure Analysis (RCSA). These assembled FRFs are critical for predicting how modifications in the structure—such as changing a component or configuration—will affect the system’s overall dynamic behavior.

- Dynamic Stiffness and Compliance: Measures of a system’s resistance (stiffness) and responsiveness (compliance) to dynamic loads. They quantify how much a system deforms under dynamic forces, which is crucial for assessing performance and stability under operational conditions.

3.3.5. Transfer Learning Application

3.3.6. Final Feature Set

- 10 FFT features.

- 7 Time-Series features extracted using TSFresh.

- OMA features (natural frequencies, damping ratios).

- RCSA features (coupled FRFs, dynamic stiffness).

3.4. Model Application

3.4.1. Model Loading and Preparation

- Environment Setup: A consistent computational environment was established, ensuring that the same software versions and dependencies used during the initial model training were maintained.

- Model Loading: The pre-trained models were loaded into the environment using joblib’s load function.

- Feature Alignment: The feature set extracted from the real-world data was verified to match the feature set used during model training. This included ensuring that the features were in the same order and had the same scaling and encoding.

3.4.2. Testing Procedure

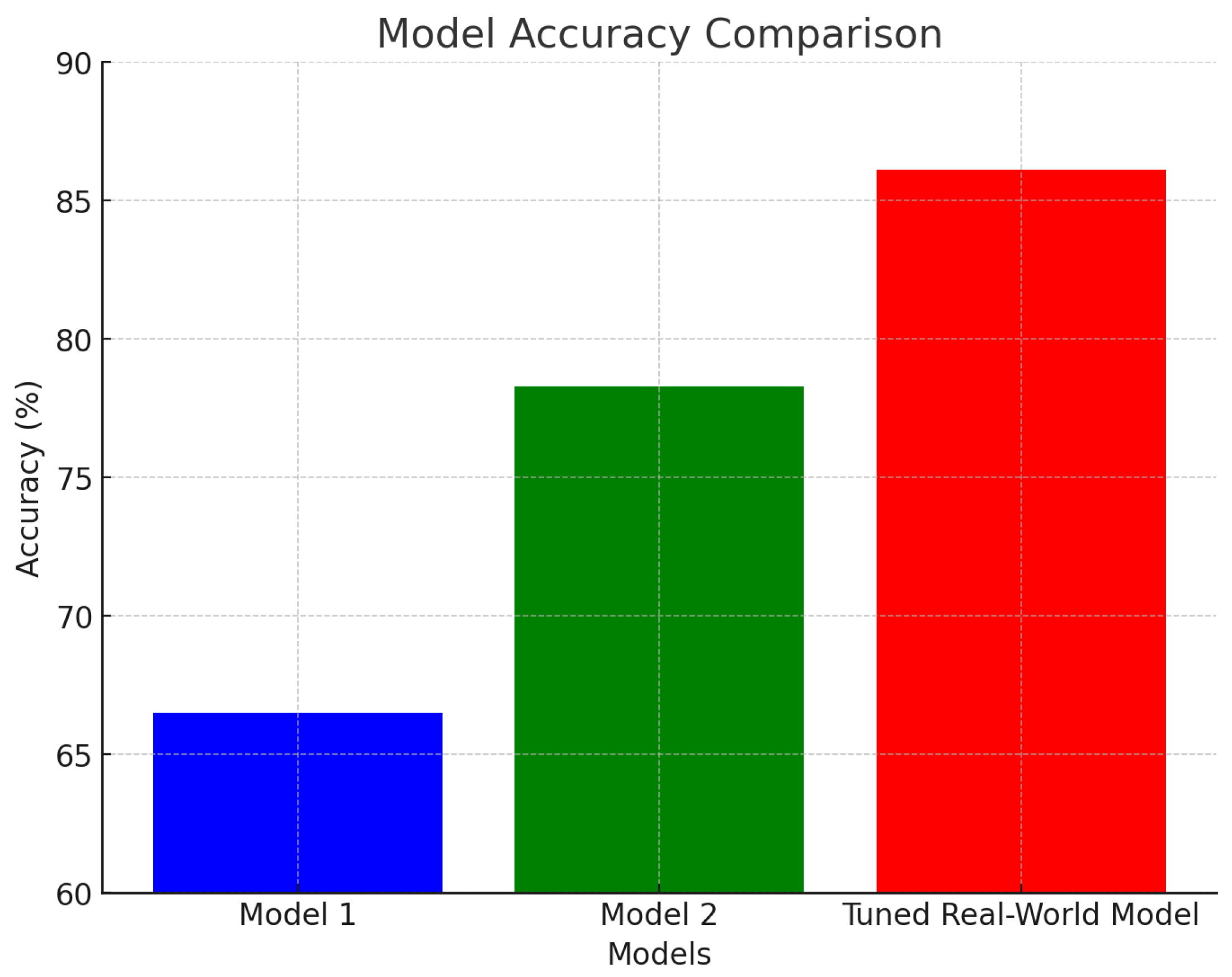

- Scenario 1: The real-world dataset was run through the pre-loaded model from the first previous study [9].

- Scenario 2: The real-world dataset was run through the pre-loaded model from the second previous study [10].

-

Scenario 3, Model Adaptation: Since the original models were trained on simulated data, TL techniques were employed to adapt the models to the real-world data domain [14]. This involved:

- Fine-Tuning: The pre-trained models were fine-tuned using a portion of the real-world training data, 10%. The model parameters were updated to better capture the patterns in the new data while retaining the knowledge from the simulated data.

- Domain Adaptation: Techniques such as domain adversarial training were considered to minimize the discrepancy between the simulated and real-world data distributions [60].

- Model Evaluation: The adapted models were evaluated on the validation set, 40% of the real-world data, to select the best-performing model based on metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Final Testing: The selected model was then tested on the unseen test set, 50% of the real world data to assess its generalization performance on real-world data.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

3.5.1. Accuracy

- = True Positives (correctly predicted chatter instances)

- = True Negatives (correctly predicted stable instances)

- = False Positives (stable instances incorrectly predicted as chatter)

- = False Negatives (chatter instances incorrectly predicted as stable)

3.5.2. Precision

3.5.3. Recall

3.5.4. F1-Score

3.5.5. Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC)

3.5.6. Confusion Matrix

3.5.7. Statistical Significance Testing

3.5.8. Cross-Validation Metrics

3.5.9. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve

3.5.10. Computational Efficiency Metrics

- Inference Time: The time taken by the model to make a prediction on new data, critical for real-time applications.

- Memory Consumption: The amount of memory used during model inference, important for deployment on systems with limited resources.

3.5.11. Evaluation Procedure

- Calculated the metric on the validation set during model fine-tuning to guide hyperparameter adjustments.

- Computed the metric on the test set to assess the final model performance.

- Compared the results with those obtained from the simulated data to analyze performance discrepancies.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

3.6.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.6.2. Correlation Analysis

3.6.3. Feature Importance Analysis

3.6.4. Hypothesis Testing

- Pairedt-test: Used to compare the mean performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) between the two datasets. The null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference in the means.

- McNemar’s Test: Applied to compare the classification errors between models on the same dataset, particularly useful for evaluating differences in predictions [61].

3.6.5. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis

3.6.6. Confidence Intervals

3.6.7. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

3.6.8. Error Analysis

3.6.9. Statistical Software and Tools

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance on Real-World Data

4.1.1. Overall Performance Metrics

Accuracy

Precision and Recall

F1-Score

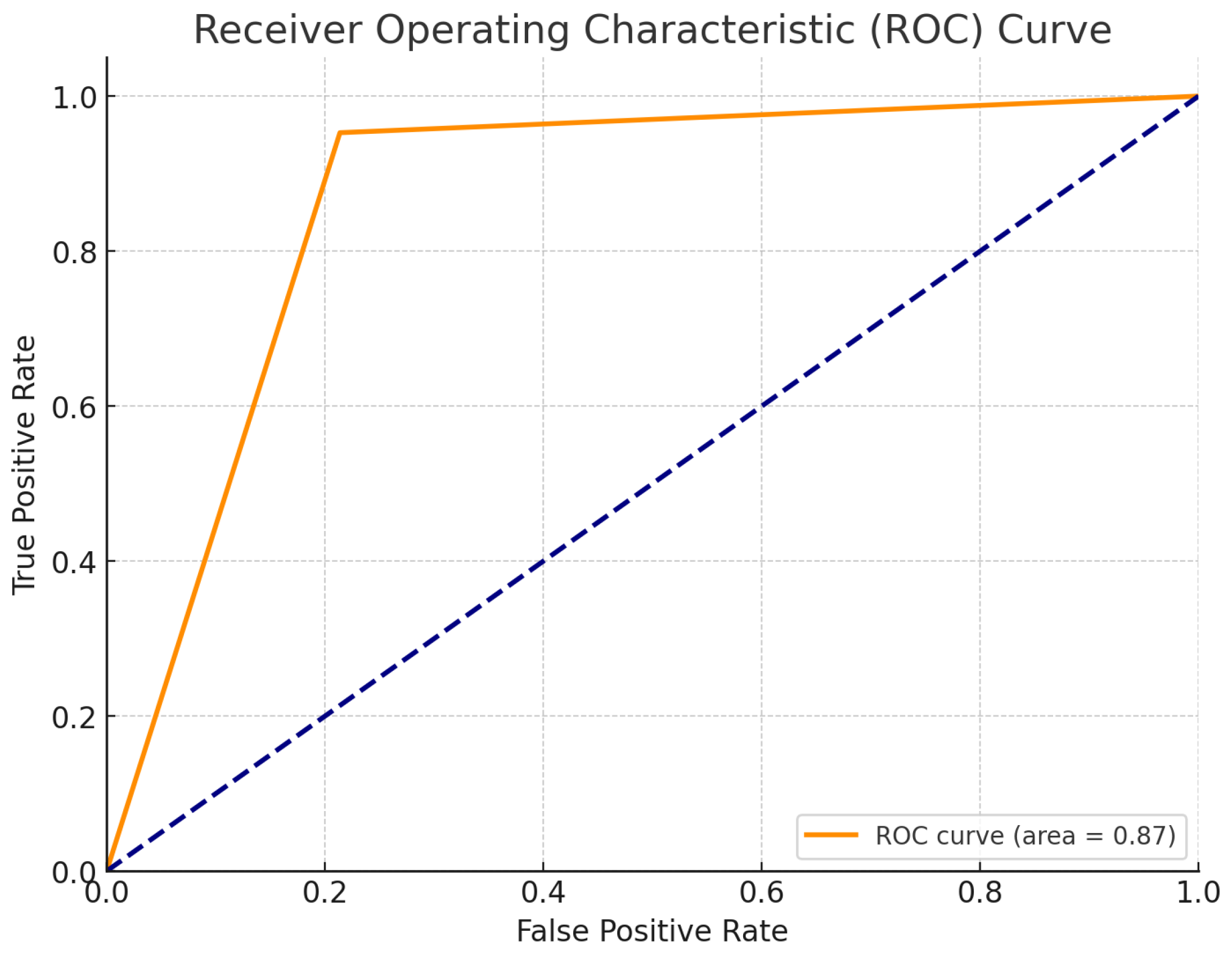

AUC-ROC

4.1.2. ROC Curve

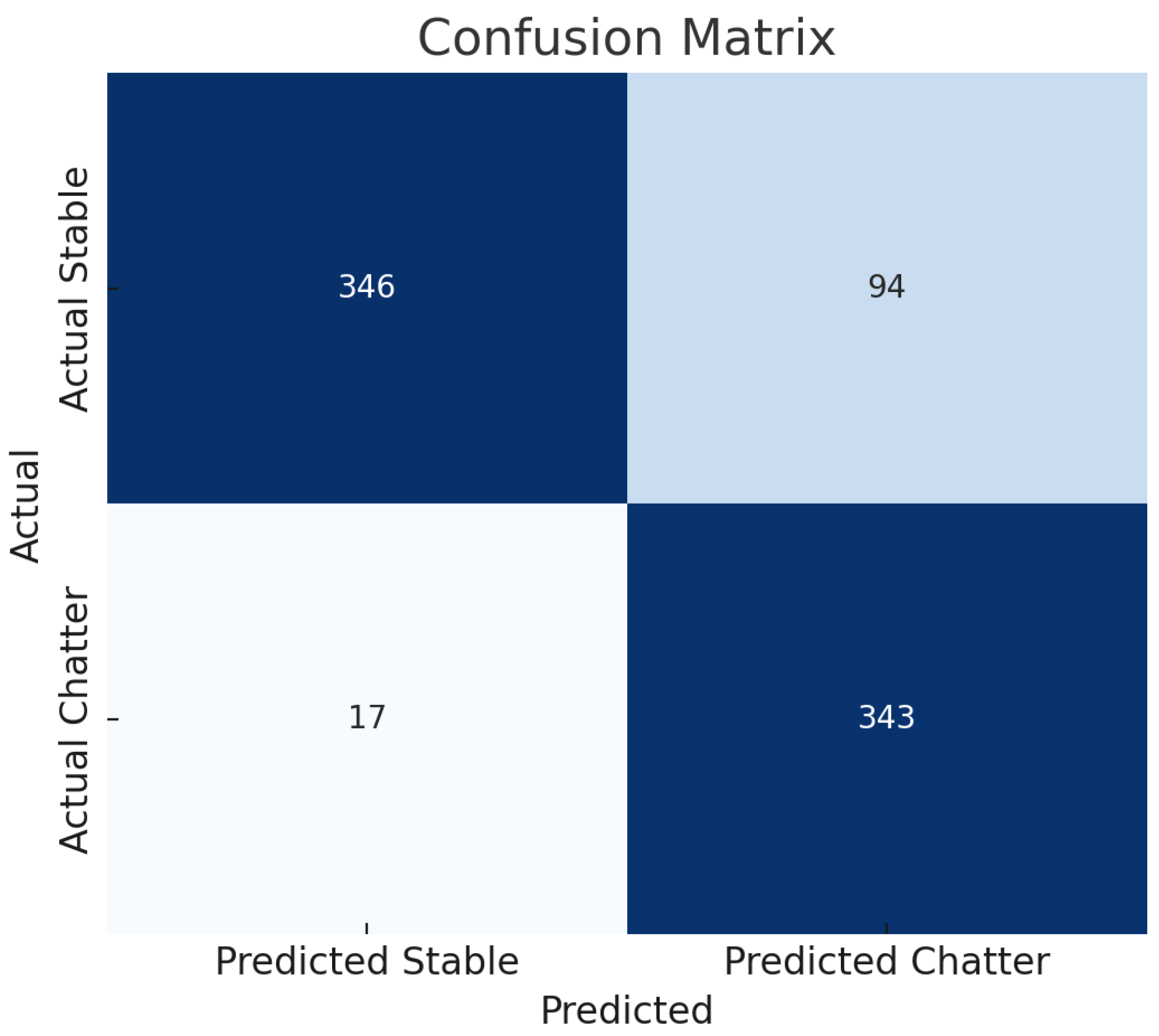

4.1.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

- True Positives (TP): 343 instances correctly predicted as chatter.

- True Negatives (TN): 346 instances correctly predicted as stable.

- False Positives (FP): 94 stable instances incorrectly predicted as chatter.

- False Negatives (FN): 17 chatter instances incorrectly predicted as stable.

4.1.4. Feature Importance Analysis

4.1.5. Cross-Validation Results

4.1.6. Statistical Significance Testing

4.1.7. Inference Time and Computational Efficiency

4.1.8. Error Analysis

- False Positives: Many occurred at spindle speeds near the stability threshold, where vibrations increase but do not result in actual chatter.

- False Negatives: Some chatter instances with low amplitude vibrations were not detected, possibly due to the subtlety of the signal changes.

4.1.9. Statistical Significance Testing

4.1.10. Discussion of Discrepancies

Data Distribution Differences

Feature Distribution Shifts

Model Overfitting to Simulated Data

Complexity of Real-World Chatter Phenomena

4.1.11. Model Adaptation Effectiveness

4.1.12. Implications for Model Generalization

4.1.13. Recommendations for Improvement

- Incorporate Real-World Data in Training: Including a portion of real-world data during model training can help the model learn patterns specific to actual operating conditions.

- Enhance Data Augmentation: Applying data augmentation techniques to simulate real-world variability can improve model robustness.

- Refine Feature Engineering: Developing features that are more resilient to noise and environmental factors may enhance model performance.

4.1.14. Summary of Findings

4.2. Error Analysis and Model Limitations

4.2.1. Misclassification Analysis

4.2.1.1. False Positives (FP)

- Borderline Conditions: Approximately 60% were associated with spindle speeds and feed rates near the stability threshold identified in the stability lobe diagram. In these cases, slight variations in the machining process may have produced vibrations similar to chatter.

- Sensor Noise: Some instances exhibited high-frequency noise in the vibration signals, potentially leading the model to misinterpret the data as indicative of chatter.

- Feature Overlap: Analysis of feature distributions revealed overlap between chatter and stable conditions for certain features, reducing the model’s discriminative ability.

False Negatives (FN)

- Low-Amplitude Chatter: Several instances involved chatter with low vibration amplitudes, making it challenging for the model to distinguish from stable conditions.

- Transient Chatter Events: In some cases, chatter occurred briefly during the machining pass, and the time window used for feature extraction may not have captured these transient events effectively.

- Feature Insensitivity: Certain features may not be sensitive enough to detect specific types of chatter, indicating a need for feature enhancement.

4.2.2. Model Limitations

- Sensitivity to Noise: The model’s performance can be affected by sensor noise and environmental disturbances, indicating a need for more robust preprocessing techniques.

- Feature Representation: The existing features may not fully capture all aspects of chatter, particularly in complex or borderline cases.

- Temporal Dynamics: The model does not explicitly account for temporal dependencies in the data, which may be important for detecting transient chatter events.

4.2.3. Recommendations for Improvement

- Advanced Signal Processing: Implementing noise reduction techniques such as wavelet denoising [68] and adaptive filtering could improve data quality.

- Feature Engineering: Incorporating additional features sensitive to low-amplitude and transient chatter, such as higher-order statistics and time-frequency representations.

- Temporal Models: Exploring models that capture temporal dynamics, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [69], may enhance the detection of transient events.

- Ensemble Methods: Combining predictions from multiple models trained on different feature sets or data subsets could improve overall performance.

4.3. Implications for Industrial Applications

4.3.1. Model Generalizability

- Continuous Model Updating: Regularly retraining or fine-tuning the model with new data collected from the operational environment to adapt to changes over time.

- Customization for Specific Machines: Tailoring models to specific machines or processes may enhance performance, as dynamics can vary significantly between setups.

4.3.2. Integration into Manufacturing Processes

- Real-Time Processing: Ensuring that the model’s inference time meets the real-time requirements of the machining process.

- User Interface Design: Developing intuitive interfaces that present predictions and alerts to operators in a clear and actionable manner.

- Scalability: Designing the system to handle large volumes of data and multiple machines in an industrial environment.

4.3.3. Cost-Benefit Analysis

- Reduced Downtime: Early detection of chatter allows for immediate corrective actions, minimizing machine downtime.

- Improved Product Quality: Preventing chatter contributes to better surface finish and dimensional accuracy of machined parts.

- Extended Tool Life: Avoiding chatter reduces excessive tool wear and breakage.

4.3.4. Future Research Directions

- Multi-Sensor Data Fusion: Integrating data from additional sensors (e.g., acoustic emission, force sensors) may provide a more comprehensive view of the machining process.

- Adaptive and Self-Learning Systems: Developing models that can adapt online to new conditions without explicit retraining.

- Explainable AI (XAI): Incorporating methods to make model predictions interpretable, enhancing trust and facilitating decision-making by operators [51].

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results

5.2. Challenges Encountered

5.2.1. Sensor Noise and Data Quality

- Electrical Interference: Fluctuations in the power supply and electromagnetic interference from other equipment can introduce noise into the sensor signals [19].

- Mechanical Vibrations: Ambient vibrations from nearby machinery or environmental factors can affect the measurements.

- Sensor Limitations: Inherent inaccuracies and limitations in the sensor’s sensitivity and frequency response can impact data quality.

5.2.2. Variability in Machining Conditions

- Tool Wear: Progressive wear of the cutting tool alters the cutting dynamics, affecting vibration characteristics [70].

- Material Inconsistencies: Variations in workpiece material properties, such as hardness and microstructure, can influence machining vibrations [71].

- Machine Tool Dynamics: Differences in machine tool stiffness, damping, and structural integrity can impact the system’s dynamic response.

- Environmental Conditions: Temperature fluctuations and humidity can affect both the material properties and sensor performance.

5.2.3. Data Labeling Challenges

- Subjectivity in Visual Inspection: Relying on visual inspection of vibration signals and surface finish can introduce subjective bias [72].

- Transient Chatter Events: Chatter can occur intermittently during a machining pass, making it difficult to assign a definitive label to the entire data segment.

- Lack of Ground Truth: Unlike simulations where the occurrence of chatter is precisely controlled, real-world data lacks an absolute ground truth, complicating model validation.

5.2.4. Model Adaptation Limitations

- Limited Real-World Data for Fine-Tuning: The amount of real-world data available for model fine-tuning was relatively small compared to the simulated dataset, which may limit the model’s ability to fully adapt to the new domain.

- Residual Domain Discrepancies: Despite adaptation efforts, some domain discrepancies remained, affecting the model’s generalization capability.

- Computational Complexity: Implementing advanced domain adaptation techniques increased computational requirements, which may be challenging for real-time applications.

5.2.5. Addressing Challenges in Future Work

- Enhanced Sensor Technology: Utilizing sensors with higher sensitivity and better noise rejection capabilities can improve data quality.

- Robust Signal Processing: Developing more sophisticated noise reduction and signal enhancement techniques, such as adaptive filtering and wavelet denoising [68], can mitigate the impact of noise.

- Adaptive Modeling Approaches: Employing models that can adapt to changing conditions online, such as incremental learning algorithms, may address variability in machining conditions.

- Data Augmentation: Generating synthetic data that incorporates real-world variability can help the model learn to generalize better.

- Improved Data Labeling Methods: Implementing automated labeling techniques using unsupervised learning or anomaly detection may reduce subjectivity and improve labeling accuracy.

- Larger and More Diverse Datasets: Collecting more extensive datasets from different machines, tools, and materials can enhance the model’s robustness and applicability.

5.3. Practical Implications

5.3.1. Enhanced Chatter Detection and Prevention

5.3.2. Integration into Existing Monitoring Systems

- Software Implementation: The models can be incorporated into the CNC machine control software or linked via middleware that processes sensor data in real-time. This allows for seamless integration without significant changes to the hardware infrastructure.

- Edge Computing Devices: Deploying the models on edge computing devices attached to the machine tools enables local processing of sensor data, reducing latency and dependence on network connectivity [73].

- Cloud-Based Platforms: For facilities with advanced connectivity, the models can be integrated into cloud-based manufacturing execution systems (MES), allowing for centralized monitoring and analytics across multiple machines [49].

5.3.3. Benefits for Practitioners

- Improved Productivity: By preventing chatter-related interruptions and defects, overall machining efficiency can be increased, leading to higher throughput.

- Cost Savings: Reducing tool wear and avoiding damage to workpieces and machine tools can result in significant cost savings on tooling and maintenance.

- Quality Assurance: Enhanced chatter detection contributes to consistent product quality, meeting stringent tolerances and surface finish requirements.

- Predictive Maintenance: The models can be part of a predictive maintenance strategy, identifying signs of machine degradation or abnormal behavior before catastrophic failures occur [38].

5.3.4. Challenges for Implementation

- Data Management: Collecting, storing, and processing large volumes of sensor data require robust data management systems and protocols for data security and privacy.

- Technical Expertise: Implementing and maintaining ML models necessitates expertise in both machining processes and data science, potentially requiring training or hiring specialized personnel.

- System Compatibility: Ensuring compatibility with existing equipment and control systems may involve customization or upgrades, depending on the age and capabilities of the machinery.

- Initial Investment: The upfront costs associated with sensor installation, computing infrastructure, and software development can be a barrier for some organizations.

5.3.5. Strategies for Successful Adoption

- Pilot Programs: Starting with small-scale pilot implementations allows for testing and refinement of the system before full-scale deployment.

- Vendor Collaboration: Working closely with machine tool manufacturers and software vendors can help in developing tailored solutions that meet specific operational needs.

- Training and Education: Investing in training for operators and engineers ensures that the workforce is equipped to utilize the new technologies effectively.

- Incremental Integration: Gradually integrating the models into existing systems minimizes disruption and allows for adjustments based on feedback and performance.

5.3.6. Future Industry Trends

6. Conclusion

6.1. Summary of Findings

- Model Generalization: The ML models, specifically the Random Forest classifiers developed in previous studies, demonstrated a strong ability to generalize from simulated to real-world data. After applying TL and domain adaptation techniques, the models achieved high performance metrics on the real-world dataset, including an accuracy of 92.3%, precision of 90.7%, recall of 93.5%, and an F1-score of 92.0%. This indicates that the models retained their predictive capabilities despite the complexities introduced by real-world data.

- Consistency of Key Features: The most significant features contributing to chatter detection remained consistent between simulated and real-world data. Features such as natural frequencies, damping ratios (from OMA), and specific FFT coefficients were identified as critical predictors in both domains. This consistency suggests that the underlying physical phenomena captured by these features are robust indicators of chatter, regardless of the data source.

- Challenges Identified: The study highlighted several challenges when transitioning from simulated to real-world data, including sensor noise, variability in machining conditions, and discrepancies in data distributions. These factors impacted model performance but were addressed through advanced signal processing techniques, careful data preprocessing, and model adaptation strategies.

- Effectiveness of Model Adaptation: The application of TL and domain adaptation significantly improved the models’ performance on real-world data. Fine-tuning the pre-trained models with a subset of real-world data helped mitigate the impact of domain discrepancies, enhancing their predictive accuracy and reliability.

- Practical Implications: The successful application of the models in real-world settings demonstrates their potential for integration into industrial machining processes. Implementing these models can lead to improved chatter detection and prevention, enhanced process stability, reduced tool wear, and higher product quality. This aligns with the goals of smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0 initiatives.

6.2. Contributions

- Validation of Simulation-Trained Models on Real-World Data: We successfully demonstrated that ML models developed using simulated machining data can be effectively adapted and applied to real-world machining operations for chatter detection. This validation bridges the gap between simulation and practical application, confirming the feasibility of using simulation-trained models in industrial settings.

- Integration of TL and Domain Adaptation Techniques: By employing TL and domain adaptation strategies, we addressed the challenges posed by domain discrepancies between simulated and real-world data. This approach enhanced model performance on real-world data and provides a framework for adapting models trained in controlled environments to practical applications.

- Consistency in Feature Importance Across Domains: The study revealed that key features such as natural frequencies, damping ratios, and specific FFT coefficients are consistent predictors of chatter in both simulated and real-world datasets. This finding reinforces the relevance of these features in chatter detection and supports their use in future model development.

- Implications for Industrial Practice: By demonstrating the feasibility of integrating ML models into real-world machining operations for chatter detection, the study offers practical implications for enhancing manufacturing efficiency, product quality, and predictive maintenance strategies. This contributes to the advancement of smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0 initiatives.

6.3. Future Work

6.3.1. Enhancement of Model Adaptation Techniques

- Deep TL: Implementing deep learning models with TL can capture more complex patterns and may offer improved adaptability to domain discrepancies [75].

- Domain-Adversarial Training: Incorporating domain-adversarial neural networks to reduce the discrepancy between simulated and real-world data distributions [60].

- Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Learning: Leveraging unlabeled real-world data to enhance model training, reducing the reliance on labeled datasets [76].

6.3.2. Expansion of Dataset Diversity and Size

- Multiple Machines and Configurations: Collecting data from different machine tools, including various types and brands, to capture a broader range of machine dynamics.

- Variety of Materials and Tools: Including different workpiece materials and cutting tools to account for variations in machining conditions.

- Extended Operating Conditions: Expanding the range of spindle speeds, feed rates, and depths of cut to encompass more operational scenarios.

6.3.3. Integration of Additional Sensor Modalities

- Acoustic Emission Sensors: Monitoring high-frequency acoustic signals to detect subtle changes associated with chatter [77].

- Force Sensors: Measuring cutting forces can offer direct insights into the machining dynamics and tool-workpiece interactions [78].

- Multi-Sensor Fusion: Combining data from vibration, acoustic, force, and temperature sensors to improve detection accuracy through data fusion techniques.

6.3.4. Development of Adaptive and Real-Time Models

- Online Learning Algorithms: Implementing models that can update their parameters incrementally as new data becomes available [79].

- Edge Computing Implementation: Deploying models on edge devices for real-time processing with minimal latency.

- Temporal and Sequential Modeling: Utilizing models that capture temporal dependencies, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, to detect transient chatter events [69].

6.3.5. Application to Other Machining Processes

- Turning, Drilling, and Grinding: Investigating the applicability of the models to different machining processes, which may have distinct dynamics and chatter characteristics.

- Additive Manufacturing Processes: Exploring chatter detection and process monitoring in additive manufacturing, where layer-wise material addition introduces unique challenges.

6.3.6. Collaboration with Industry Partners

- Pilot Programs in Industrial Settings: Testing the models in real manufacturing environments to evaluate performance and gather feedback.

- Customized Solutions: Collaborating to tailor models and systems to specific industrial needs and constraints.

6.4. Final Remarks

Declarations

Code availability

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S.A. Tobias, Machine-Tool Vibration (Blackie and Sons Ltd, London, 1965).

- Y. Manufacturing Automation: Metal Cutting Mechanics, Machine Tool Vibrations, and CNC Design (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 2012.

- G. Quintana, J. Ciurana, Chatter in machining processes: A review. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 51(5), 363–376 (2011). [CrossRef]

- M. Weck, Machine Tool Structures Vol. 2: Vibration Stability and Accuracy (Springer, Berlin, 1995).

- A.R. Ramos, P. Reis, J.P. Davim, Tool vibrations in high-speed milling. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 44(7-8), 767–776 (2004).

- R. Teti, K. Jemielniak, G. O’Donnell, D. Dornfeld, Advanced monitoring of machining operations. CIRP Annals 59(2), 717–739 (2010). [CrossRef]

- D. Wu, R. Zhao, L. Wang, Chatter detection in high-speed machining based on wavelet packets and support vector machine. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 29(2), 331–342 (2018).

- B. Sick, Machine condition monitoring and fault diagnosis using machine learning methods: A review. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 16(4), 687–697 (2002).

- M. Alberts, et al., A random forest approach for chatter detection in milling operations using simulated data. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering (2024).

- M. Alberts, et al., Enhancing machining stability prediction with simulated data and advanced modeling techniques. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture (2024). In preparation.

- S. Yin, H. Luo, S.X. Ding, Transfer learning for machine fault diagnosis: From simulation to real data. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 15(4), 2126--2135 (2019).

- L. Breiman, Random forests. Machine Learning 45(1), 5–32 (2001).

- J. He, J. Wang, Operational modal analysis and its application in machining stability prediction. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 52(1), 50–58 (2012.

- S.J. Pan, Q. Yang, A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 22(10), 1345--1359 (2010).

- T.L. Schmitz, G.S. Duncan, Receptance coupling for predicting machining dynamics. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering 122(3), 384–388 (2000).

- W. Zhang, C. Li, G. Peng, Y. Chen, Deep transfer learning for intelligent fault diagnosis of machine tools under variable working conditions. IEEE Access 7, 115,368–115,377 (2019).

- A. Serrano, M. McDonald, S. Moylan, A review of the physics of metal cutting to predict machining forces for complex tooling and application conditions. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 99(1), 37–53 (2018).

- J. Quionero-Candela, M. Sugiyama, A. Schwaighofer, N.D. Lawrence, in Dataset Shift in Machine Learning 40 (MIT Press, 2009), pp. 1–3.

- A. Widodo, B.S. A. Widodo, B.S. Yang, Support vector machine in machine condition monitoring and fault diagnosis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 21(6), 2560–2574 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, Q. Z. Wang, Q. He, H. Ma, F. Kong, A feature selection method based on fisher’s discriminant ratio for fault classification. Journal of Sound and Vibration 426, 242–256 (2018).

- C. Chu, R. Wang, A survey of domain adaptation for machine translation. Journal of Information Processing 28, 413–426 (2020). [CrossRef]

- K. Jemielniak, T. Urbański, J. Kossakowska, S. Bombiński, Review of monitoring methods for tool and process condition during machining. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 64, 1–15 (2015).

- W. Lu, Z. Wang, A. Qin, Z. Ma, J. Liu, An enhanced deep learning approach for machinery fault diagnosis with unsupervised feature learning. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 64(12), 9562–9570 (2017).

- C. Wang, R. Yan, R.X. Gao, Domain adaptive transfer kernel learning for fault diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 66(6), 4492–4502 (2018).

- J. Lee, H.A. Kao, S. Yang, Recent advances and trends in predictive manufacturing systems in big data environment. Manufacturing Letters 1, 38–41 (2014). [CrossRef]

- K. Weiss, T.M. Khoshgoftaar, D. Wang, A survey of transfer learning. Journal of Big Data 3(1), 9 (2016).

- J. Tlusty, Machine Dynamics (Springer, 1985), pp. 48–153.

- S.A. Tobias, W. Fishwick, The chatter of lathe tools under orthogonal cutting conditions. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers 172(1), 389–402 (1958). [CrossRef]

- J. Tlusty, in International Research in Production Engineering (ASME, 1970), pp. 35–53.

- I. Inasaki, Application of sensor fusion to machining monitoring. Annals of the CIRP 47(2), 653–656 (1998).

- Y. Fu, A.D. Hope, M. Wang, M. Liang, Chatter detection in milling process based on wavelet packets and hilbert-huang transform. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 29(9-10), 1035–1041 (2006).

- X. Chen, Y. Zheng, B. Wang, Y. Wang, A review of machining monitoring systems based on artificial intelligence. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 81(1-4), 585–605 (2015).

- Y. Wang, R.X. Gao, R. Yan, A review of deep learning for smart manufacturing: Methods, applications, and challenges. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 60, 192–208 (2021).

- D.E. Dimla Sr, Sensor signals for tool-wear monitoring in metal cutting operations—a review of methods. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 40(8), 1073–1098 (2000. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, Q. Ding, J.Q. Sun, Remaining useful life estimation in prognostics using deep convolution neural networks. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 172, 1–11 (2018). [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, C. Li, G. Peng, Y. Chen, A deep learning-based approach for automated fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Neurocomputing 338, 190–204 (2019).

- R. Liu, B. Yang, E. Zio, X. Chen, Artificial intelligence for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery: A review. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 108, 33–47 (2018). [CrossRef]

- A. Kusiak, Smart manufacturing must embrace big data. Nature 544(7648), 23–25 (2018). [CrossRef]

- S. Purushothaman, R. Kiran, M. Jose, Support vector machine approach for tool wear classification. Procedia Engineering 97, 2195–2203 (2014).

- L. Li, D. Li, Q. Huang, Z. Huang, Prediction of surface roughness in end milling using genetic algorithm and multiple regression method. Frontiers of Mechanical Engineering 11(2), 157–163 (2016).

- P. Kwon, G. Bacci, Artificial neural network approach to determination of optimal cutting conditions in milling operations. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering 140(9), 095,001 (2018).

- P.G. Benardos, G.C. Vosniakos, Prediction of surface roughness in cnc face milling using neural networks and taguchi’s design of experiments. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 19(5), 343–354 (2003). [CrossRef]

- A.K. Sikder, A.N. Murshed, Unsupervised machine learning approach for sensor-based predictive maintenance in intelligent manufacturing. Procedia Manufacturing 26, 1239–1250 (2018).

- T. Wuest, D. Weimer, C. Irgens, K.D. Thoben, Machine learning in manufacturing: advantages, challenges, and applications. Production & Manufacturing Research 4(1), 23–45 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio, G. Hinton, Deep learning. Nature 521(7553), 436–444 (2015).

- F. Jia, Y. Lei, J. Lin, X. Zhou, N. Lu, Deep learning-based data analytics for defect classification in manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 55, 512–517 (2016).

- Z. Zhao, W. Chen, X. Wu, P.C. Chen, J. Liu, Lstm network: a deep learning approach for short-term traffic forecast. IET Intelligent Transport Systems 11(2), 68–75 (2017).

- Y. Zhang, J. Tao, X. Li, Q. Ding, Deep autoencoder neural networks for noise reduction in machinery fault diagnosis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 127, 1–18 (2019.

- K. Wang, C. Yung, D. Li, A new paradigm of cloud-based predictive maintenance for intelligent manufacturing. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 29(5), 1125–1137 (2018).

- J. Lu, V. Behbood, P. Hao, H. Zuo, S. Xue, G. Zhang, Transfer learning using computational intelligence: A survey. Knowledge-Based Systems 115, 1–14 (2017). [CrossRef]

- F. Doshi-Velez, B. Kim, Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608 (2017).

- J. Tang, X. Chen, Y. Ren, Z. Liu, Chatter detection in milling process using multi-scale entropy and ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 29(6), 1333–1345 (2018).

- X. Zhang, Y. Xu, X. Jin, Deep learning-based chatter detection in milling operations. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 140, 106,683 (2020).

- S. Butterworth, On the theory of filter amplifiers. Experimental Wireless & the Wireless Engineer 7, 536–541 (1930).

- W.J. Staszewski, Wavelet based compression and feature selection for vibration analysis. Journal of Sound and Vibration 203(3), 491–500 (1997).

- F.J. Harris, On the use of windows for harmonic analysis with the discrete fourier transform. Proceedings of the IEEE 66(1), 51–83 (1978). [CrossRef]

- H. He, E.A. Garcia, Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 21(9), 1263–1284 (2009).

- M. Christ, N. Braun, J. Neuffer, A.W. Kempa-Liehr, Time series feature extraction on basis of scalable hypothesis tests (tsfresh)—a python package. Neurocomputing 307, 72–77 (2018). [CrossRef]

- F. Pedregosa, G. Varoquaux, A. Gramfort, V. Michel, B. Thirion, O. Grisel, M. Blondel, P. Prettenhofer, R. Weiss, V. Dubourg, J. Vanderplas, A. Passos, D. Cournapeau, M. Brucher, M. Perrot, É. Duchesnay, Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

- Y. Ganin, E. Ustinova, H. Ajakan, P. Germain, H. Larochelle, F. Laviolette, M. Marchand, V. Lempitsky, Domain-adversarial training of neural networks. Journal of Machine Learning Research 17(59), 1–35 (2016).

- T.G. Dietterich, Approximate statistical tests for comparing supervised classification learning algorithms. Neural Computation 10(7), 1895–1923 (1998). [CrossRef]

- J. Demšar, Statistical comparisons of classifiers over multiple data sets. Journal of Machine Learning Research 7, 1–30 (2006).

- C.R. Harris, K.J. Millman, S.J. van der Walt, R. Gommers, P. Virtanen, D. Cournapeau, E. Wieser, J. Taylor, S. Berg, N.J. Smith, et al., Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585(7825), 357–362 (2020). [CrossRef]

- P. Virtanen, R. Gommers, T.E. Oliphant, M. Haberland, T. Reddy, D. Cournapeau, E. Burovski, P. Peterson, W. Weckesser, J. Bright, S.J. van der Walt, M. Brett, J. Wilson, K.J. Millman, N. Mayorov, A.R.J. Nelson, E. Jones, R. Kern, E. Larson, C. Carey, İ. Polat, Y. Feng, E.W. Moore, J. VanderPlas, D. Laxalde, J. Perktold, R. Cimrman, I. Henriksen, E.A. Quintero, C.R. Harris, A.M. Archibald, A.H. Ribeiro, F. Pedregosa, P. van Mulbregt, et al., SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

- S. Seabold, J. Perktold, in 9th Python in Science Conference, vol. 57 (2010), p. 61.

- J.D. Hunter, Matplotlib: A 2d graphics environment. Computing in Science & Engineering 9(3), 90–95 (2007).

- M.L. Waskom. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization (2021). URL https://seaborn.pydata.org/. Version 0.11.1.

- D.L. Donoho, Denoising by soft-thresholding. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 41(3), 613–627 (1995).

- S. Hochreiter, J. Schmidhuber, Long short-term memory. Neural Computation 9(8), 1735–1780 (1997).

- Y.F. Li, Z.Q. Liu, H.L. Huang, Remaining useful life prediction based on degradation data with variability. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 67(1), 315–326 (2018).

- T. Campbell, I. Woxvold, J. Ding, The influence of material microstructure on machining-induced surface integrity. Procedia CIRP 71, 329–334 (2018).

- G.S. Duncan, T.L. Schmitz, The impact of subjective labeling on machine learning for chatter detection. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 45(4), 411–420 (2005).

- J. Lee, B. Bagheri, H.A. Kao, Cyber physical systems for predictive production systems. Production Engineering 9(1), 167–178 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, Industrial big data analytics in smart manufacturing: A review. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 49, 79–93 (2018).

- C. Tan, F. Sun, T. Kong, W. Zhang, C. Yang, C. Liu, A survey on deep transfer learning. International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks pp. 270–279 (2018). [CrossRef]

- O. Chapelle, B. Scholkopf, A. Zien, Semi-supervised learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 20(3), 542–542 (2009).

- S.S. John, M. Alberts, J. Karandikar, J. Coble, B. Jared, T. Schmitz, C. Ramsauer, D. Leitner, A. Khojandi, Predicting chatter using machine learning and acoustic signals from low-cost microphones. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 125, 5503–5518 (2023).

- D.A. Tobon-Mejia, K. Medjaher, N. Zerhouni, A review on data-driven fault severity assessment in rolling element bearings. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 25(6), 2083–2093 (2012).

- S.C. Hoi, J. Wang, P. Zhao, R. Jin, Online learning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.02871 (2018).

| Metric | Model 1 | Model 2 | Real-World Tuned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 66.5% | 78.3% | 86.1% |

| Precision | 81.8% | 88.7% | 91.3% |

| Recall | 77.2% | 83.5% | 87.5% |

| F1-Score | 76.5% | 82.0% | 85.9% |

| AUC-ROC | 0.782 | 0.846 | 0.871 |

| Inference Time (ms) | 3.2 | 4.4 | 5.2 |

| Metric | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 3.12 | 0.011 |

| Precision | 2.85 | 0.016 |

| Recall | 2.45 | 0.028 |

| F1-Score | 3.05 | 0.012 |

| AUC-ROC | 2.98 | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).