Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

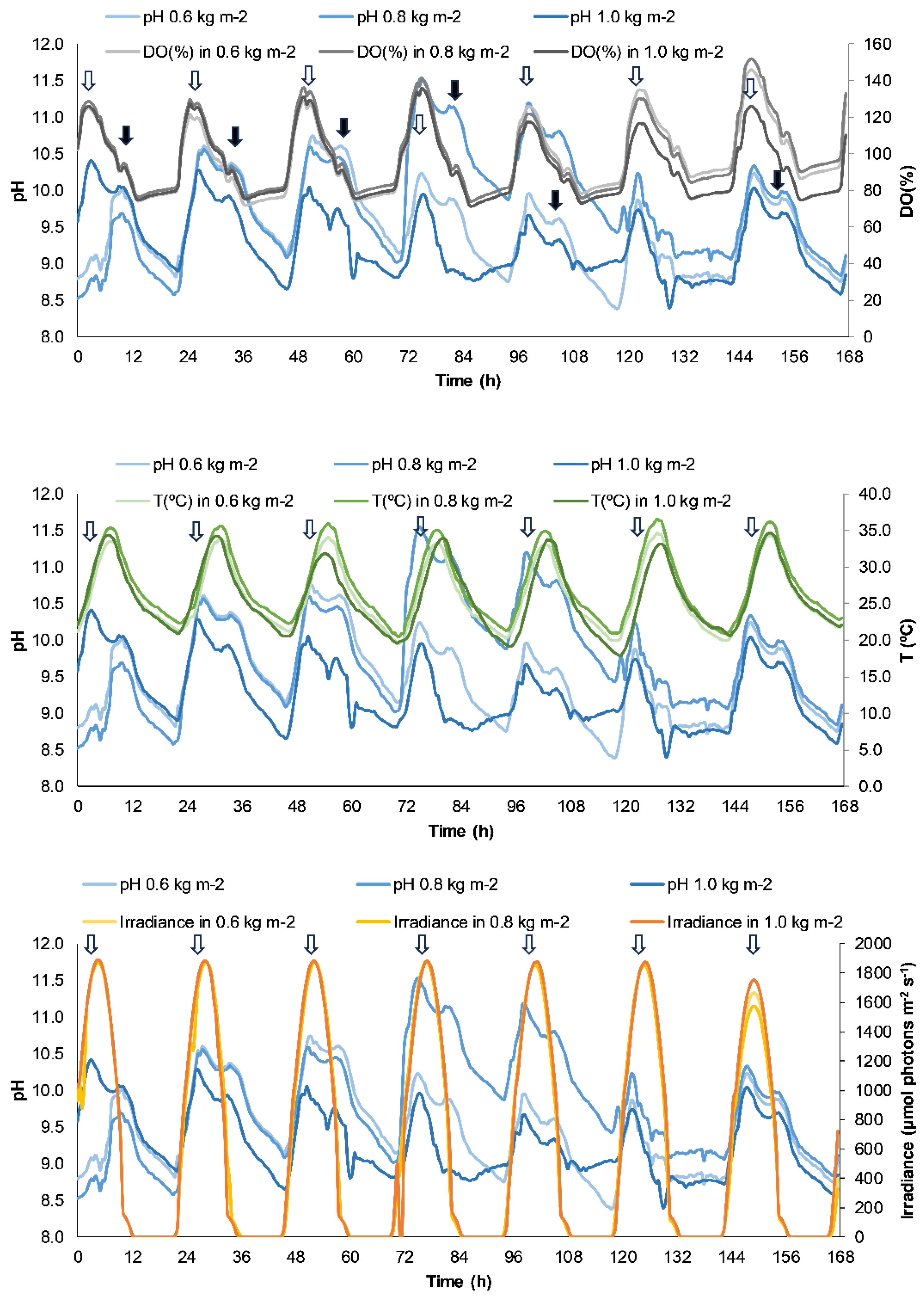

2.1. Diurnal Variation in Water Physical and Chemical Variables during the Course of the Culture.

2.2. Biomass Growth Rate and Nutrient Assimilation in the Raceway Ponds.

2.3. Effect of Algal Density on Physiological and Functional Variables.

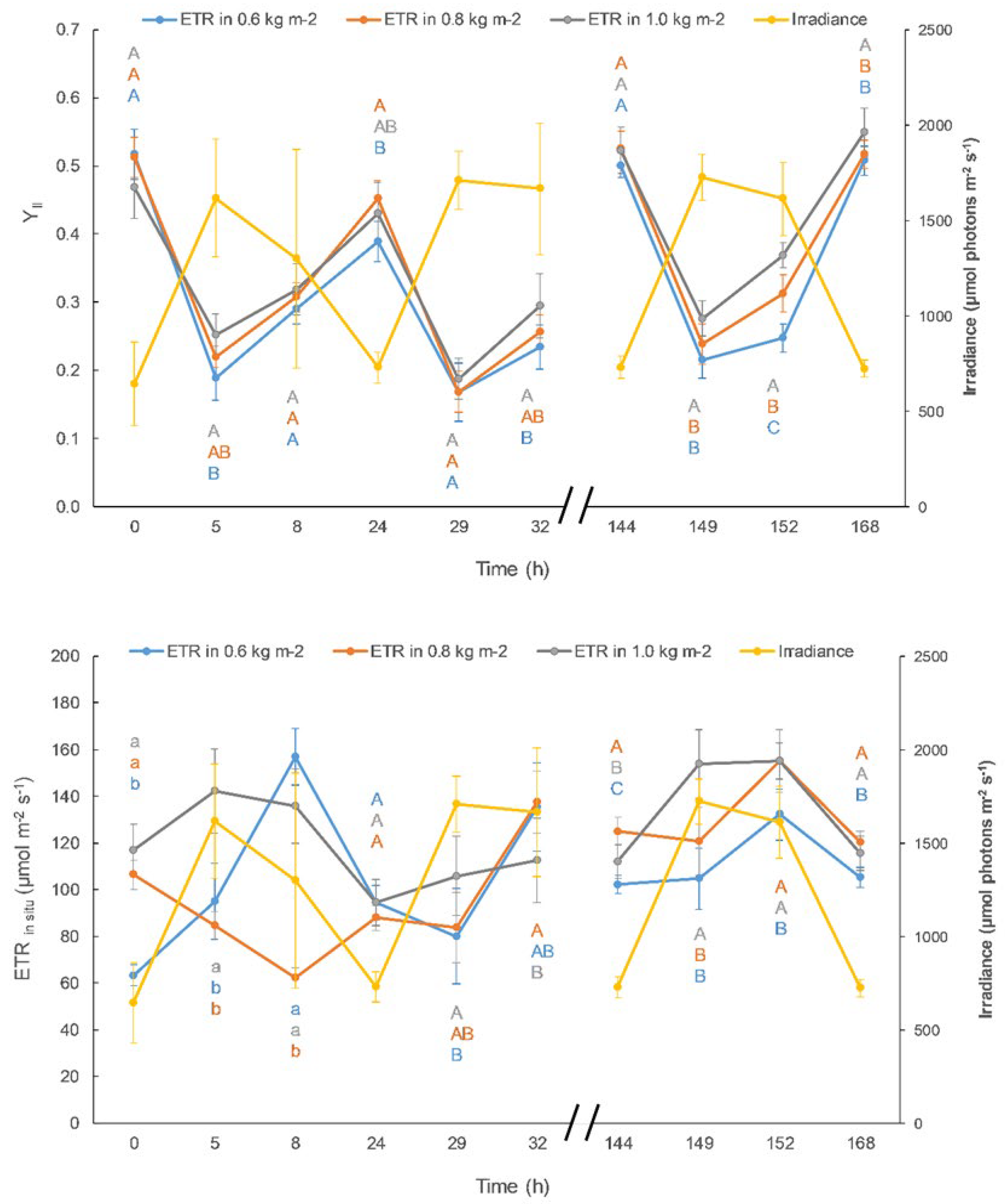

2.3.1. In Situ Photosynthetic Activity.

2.3.2. Ex Situ Photosynthetic Activity: Rapid Light Curves (RLC).

2.4. Effect of Algal Acclimatization on Physiological and Functional Variables.

2.5. Functional Relationship between Variables.

3. Discussion

3.1. Physical and Chemical Variables during the Culture.

3.2. Biomass Growth Rate and Nutrient Assimilation in the Raceway Ponds.

3.3. Effect of Algal Density on Physiological and Functional Variables.

3.4. Effect of Algal Acclimatization on Physiological and Functional Variables.

3.5. Functional Relationship between Variables.

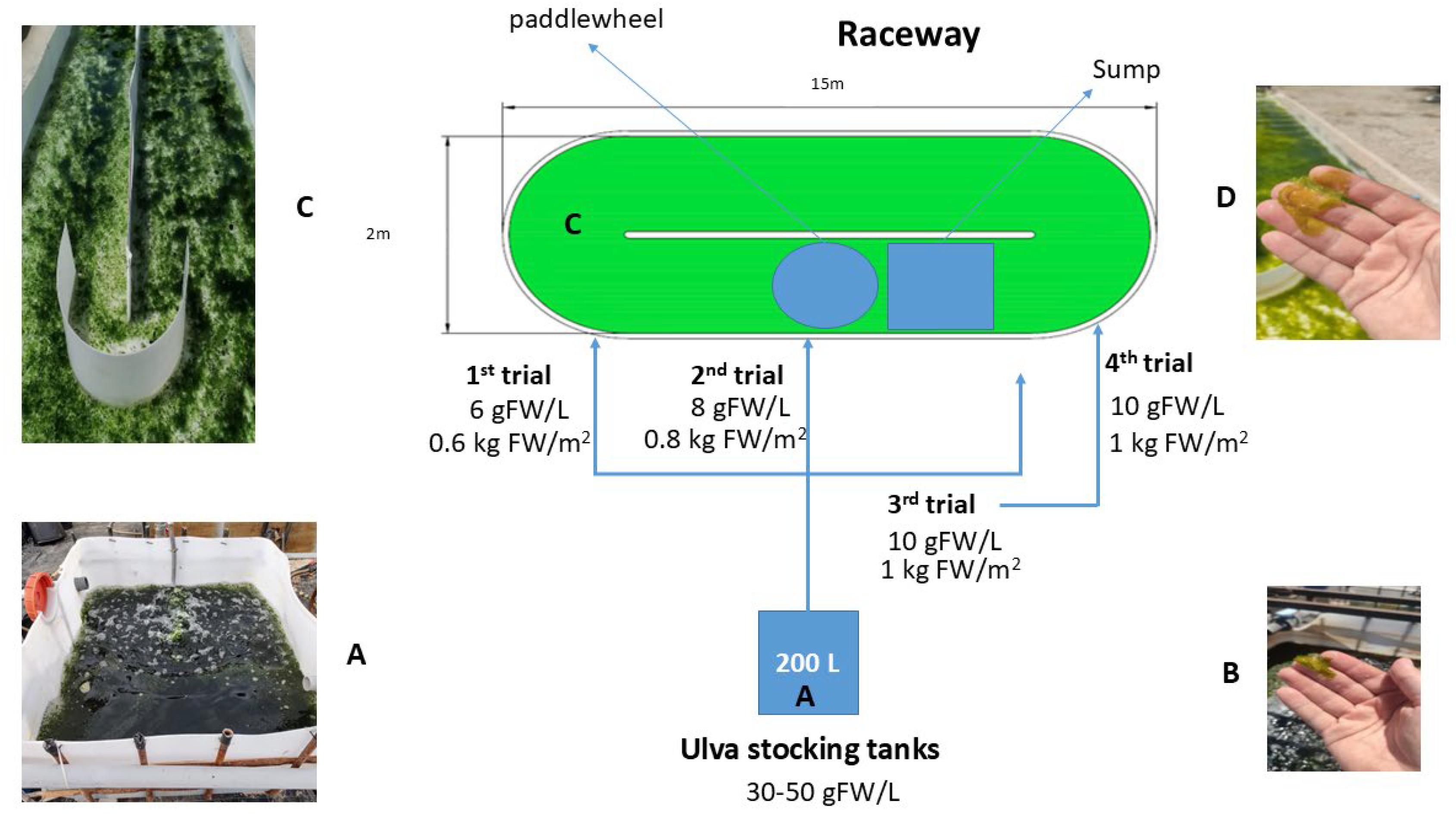

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Experimental Conditions

4.3. Water Physical and Chemical Analysis.

4.4. Biomass Growth Parameters and Physiological Variables Measurements.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions and Future Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bermejo R, Buschmann A, Capuzzo E, Cottier-Cook E, Fricke A, Hernández I, et al. State of knowledge regarding the potential of macroalgae cultivation in providing climate-related and other ecosystem services: a report of the Eklipse Expert Working Group on Macroalgae cultivation and Ecosystem Services. 76 p.

- Duarte CM, Bruhn A, Krause-Jensen D. A seaweed aquaculture imperative to meet global sustainability targets. Vol. 5, Nature Sustainability. Nature Research; 2022. p. 185–93. [CrossRef]

- Charrier B, Abreu MH, Araujo R, Bruhn A, Coates JC, De Clerck O, et al. Furthering knowledge of seaweed growth and development to facilitate sustainable aquaculture. Vol. 216, New Phytologist. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2017. p. 967–75. [CrossRef]

- Jusadi D, Ekasari J, Suprayudi MA, Setiawati M, Fauzi IA. Potential of Underutilized Marine Organisms for Aquaculture Feeds. Front Mar Sci. 2021 Feb 11; 7:1250. [CrossRef]

- Massocato T, Robles-Carnero V, Vega J, Bastos E, Avilés A, Bonomi-Baru J, et al. Short-term nutrient removal eficiency by Ulva pseudorotundata (Chlorophyta): potential use for Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA). 2022. [CrossRef]

- Massocato TF, Robles-Carnero V, Moreira BR, Castro-Varela P, Pinheiro-Silva L, Oliveira W da S, et al. Growth, biofiltration and photosynthetic performance of Ulva spp. cultivated in fishpond effluents: An outdoor study. Front Mar Sci. 2022 Sep 2; 9:1550. [CrossRef]

- Vega J, Schneider G, Moreira BR, Herrera C, Bonomi-Barufi J, Figueroa FL. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids from Red Macroalgae: UV-Photoprotectors with Potential Cosmeceutical Applications. Applied Sciences 2021, Vol 11, Page 5112. 2021 May 31;11[11]:5112. [CrossRef]

- Neori A, Chopin T, Troell M, Buschmann AH, Kraemer GP, Halling C, et al. Integrated aquaculture: rationale, evolution and state of the art emphasizing seaweed biofiltration in modern mariculture. Aquaculture. 2004 Mar 5;231[1–4]:361–91. [CrossRef]

- Buschmann AH, Camus C, Infante J, Neori A, Israel Á, Hernández-González MC, et al. Seaweed production: overview of the global state of exploitation, farming and emerging research activity. Eur J Phycol. 2017 Oct 2;52[4]:391–406. [CrossRef]

- Kim JK, Yarish C, Hwang EK, Park M, Kim Y, Kim JK, et al. Seaweed aquaculture: cultivation technologies, challenges and its ecosystem services. Algae. 2017 Mar 15 ;32(1):1–13. [CrossRef]

- Monti M, Minocci M, Beran A, Iveša L. First record of Ostreopsis cfr. ovata on macroalgae in the Northern Adriatic Sea. Mar Pollut Bull. 2007 May 1;54(5):598–601. [CrossRef]

- A Akcali I, Kucuksezgin F. A biomonitoring study: Heavy metals in macroalgae from eastern Aegean coastal areas. Mar Pollut Bull. 2011 Mar 1;62(3):637–45. [CrossRef]

- B Baumann HA, Morrison L, Stengel DB. Metal accumulation and toxicity measured by PAM—Chlorophyll fluorescence in seven species of marine macroalgae. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2009 May 1;72(4):1063–75. [CrossRef]

- García-Poza S, Leandro A, Cotas C, Cotas J, Marques JC, Pereira L, et al. The Evolution Road of Seaweed Aquaculture: Cultivation Technologies and the Industry 4.0. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, Vol 17, Page 6528. 2020 Sep 8;17(18):6528. [CrossRef]

- Dini I. The Potential of Algae in the Nutricosmetic Sector. Molecules 2023, Vol 28, Page 4032 . 2023 May 11 ;28(10):4032. [CrossRef]

- Zertuche-González JA, Sandoval-Gil JM, Rangel-Mendoza LK, Gálvez-Palazuelos AI, Guzmán-Calderón JM, Yarish C. Seasonal and interannual production of sea lettuce (Ulva sp.) in outdoor cultures based on commercial size ponds. J World Aquac Soc. 2021 Oct 1;52(5):1047–58. [CrossRef]

- Fort A, Lebrault M, Allaire M, Esteves-Ferreira AA, McHale M, Lopez F, et al. Extensive Variations in Diurnal Growth Patterns and Metabolism Among Ulva spp. Strains. Plant Physiol . 2019 May 3 ;180(1):109–23. [CrossRef]

- Lapointe BE, Tenore KR. Experimental outdoor studies with Ulva fasciata Delile. I. Interaction of light and nitrogen on nutrient uptake, growth, and biochemical composition. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1981 Jul 14;53[2–3]:135–52. [CrossRef]

- Ryther JH, Lapointe BE. The Effects of Nitrogen and Seawater Flow Rate on the Growth and Biochemical Composition of Gracilaria foliifera var. angustissima in Mass Outdoor Cultures. Botanica Marina. 1979 Jan 1 ;22(8):529–38. [CrossRef]

- Chopin T, Robinson SMC, Troell M, Neori A, Buschmann AH, Fang J. Multitrophic Integration for Sustainable Marine Aquaculture. In: Encyclopedia of Ecology, Five-Volume Set. Elsevier Inc.; 2008. p. 2463–75. [CrossRef]

- Neori A, Msuya FE, Shauli L, Schuenhoff A, Kopel F, Shpigel M. A novel three-stage seaweed (Ulva lactuca) biofilter design for integrated mariculture. J Appl Phycol. 2003 Nov ;15(6):543–53. [CrossRef]

- Buck BH, Shpigel M. ULVA: Tomorrow’s “Wheat of the sea”, a model for an innovative mariculture. J Appl Phycol . 2023 Jul 21 ;1:1–4. [CrossRef]

- Acién Fernández FG, Gómez-Serrano C, Fernández-Sevilla JM. Recovery of Nutrients From Wastewaters Using Microalgae. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2018 Sep 20; 2:59. [CrossRef]

- San Pedro A, González-López C V., Acién FG, Molina-Grima E. Outdoor pilot production of Nannochloropsis gaditana: Influence of culture parameters and lipid production rates in raceway ponds. Algal Res. 2015 Mar 1; 8:205–13. [CrossRef]

- Sharma AK, Sharma A, Singh Y, Chen WH. Production of a sustainable fuel from microalgae Chlorella minutissima grown in a 1500 L open raceway ponds. Biomass Bioenergy. 2021 Jun 1; 149:106073. [CrossRef]

- Shpigel M, Guttman L, Ben-Ezra D, Yu J, Chen S. Is Ulva sp. able to be an efficient biofilter for mariculture effluents? J Appl Phycol. 2019 Aug 1;31(4):2449–59. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Bonomi-Barufi J, Celis-Plá PSM, Nitschke U, Arenas F, Connan S, et al. Short-term effects of increased CO2, nitrate and temperature on photosynthetic activity in Ulva rigida (Chlorophyta) estimated by different pulse amplitude modulated fluorometers and oxygen evolution. J Exp Bot . 2021 Feb 2 ;72(2):491–509. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Korbee N, Abdala R, Jerez CG, López-de la Torre M, Güenaga L, et al. Biofiltration of fishpond effluents and accumulation of N-compounds (phycobiliproteins and mycosporine-like amino acids) versus C-compounds (polysaccharides) in Hydropuntia cornea (Rhodophyta). Mar Pollut Bull. 2012 Feb 1;64(2):310–8. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera J, De Gálvez MV, Conde R, Pérez-Rodríguez E, Viñegla B, Abdala R, et al. Series temporales de medida de radiación solar ultravioleta y fotosintética en Málaga. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2004 Oct 1;95(1):25–31. [CrossRef]

- Green-Gavrielidis LA, Thornber CS. Will Climate Change Enhance Algal Blooms? The Individual and Interactive Effects of Temperature and Rain on the Macroalgae Ulva. Estuaries and Coasts . 2022 Sep 1 ;45(6):1688–700. [CrossRef]

- Xiao J, Zhang X, Gao C, Jiang M, Li R, Wang Z, et al. Effect of temperature, salinity and irradiance on growth and photosynthesis of Ulva prolifera. Acta Oceanologica Sinica. 2016 Oct 1;35(10):114–21. [CrossRef]

- Bews E, Booher L, Polizzi T, Long C, Kim JH, Edwards MS. Effects of salinity and nutrients on metabolism and growth of Ulva lactuca: Implications for bioremediation of coastal watersheds. Mar Pollut Bull. 2021 May 1; 166:112199. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Tong Y, Xia J, Sun Y, Zhao X, Sun J, et al. Ulva macroalgae within local aquaculture ponds along the estuary of Dagu River, Jiaozhou Bay, Qingdao. Mar Pollut Bull. 2022 Jan 1; 174:113243. [CrossRef]

- Beer S, Eshel A. Photosynthesis of Ulva sp. II. Utilization of CO and HCO-3 when submerged. Vol. 70, Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1983. [CrossRef]

- Axelsson L, Ryberg H, Beer S. Two modes of bicarbonate utilization in the marine green macroalga Ulva lactuca. Plant Cell Environ . 1995 Apr 1 ;18(4):439–45. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Conde-Álvarez R, Gómez I. Relations between electron transport rates determined by pulse amplitude modulated chlorophyll fluorescence and oxygen evolution in macroalgae under different light conditions. Photosynth Res . 2003 ,75(3):259–75. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Israel A, Neori A, Martínez B, Malta E jan, Ang P, et al. Effects of nutrient supply on photosynthesis and pigmentation in Ulva lactuca (Chlorophyta): responses to short-term stress. Aquat Biol . 2009 Oct 22 ;7[1–2]:173–83. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Santos R, Conde-Álvarez R, Mata L, Gómez Pinchetti JL, Matos J, et al. The use of chlorophyll fluorescence for monitoring photosynthetic condition of two tank-cultivated red macroalgae using fishpond effluents. Botanica Marina . 2006 Sep 1 ;49(4):275–82. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Álvarez-Gómez F, Bonomi-Barufi J, Vega J, Massocato TF, Gómez-Pinchetti JL, et al. Interactive effects of solar radiation and inorganic nutrients on biofiltration, biomass production, photosynthetic activity and the accumulation of bioactive compounds in Gracilaria cornea (Rhodophyta). Algal Res. 2022 Nov 1; 68:102890. [CrossRef]

- Jerez CG, Malapascua JR, Sergejevová M, Masojídek J, Figueroa FL. Chlorella fusca (Chlorophyta) grown in thin-layer cascades: Estimation of biomass productivity by in-vivo chlorophyll a fluorescence monitoring. Algal Res. 2016 Jul 1; 17:21–30. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Conde-Álvarez R, Bonomi Barufi J, Celis-Plá PS, Flores P, Malta EJ, et al. Continuous monitoring of in vivo chlorophyll a fluorescence in ulva rigida (Chlorophyta) submitted to different CO2, nutrient and temperature regimes. Aquat Biol. 2014 Nov 20; 22:195–212. [CrossRef]

- Mata L, Schuenhoff A, Santos R. A direct comparison of the performance of the seaweed biofilters, Asparagopsis armata and Ulva rigida. J Appl Phycol . 2010 Feb 17;22(5):639–44. [CrossRef]

- Mata L, Santos R. Cultivation of Ulva rotundata (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) in raceways using semi-intensive fishpond effluents: yield and biofiltration. Proceedings of the 17th International Seaweed Symposium, Cape Town, South Africa, 28 January-2 February 2001. 2003;237–42.

- Msuya FE, Neori A. Effect of water aeration and nutrient load level on biomass yield, N uptake and protein content of the seaweed Ulva lactuca cultured in seawater tanks. J Appl Phycol . 2008 Dec 1 ;20(6):1021–31. [CrossRef]

- Msuya FE, Kyewalyanga MS, Salum D. The performance of the seaweed Ulva reticulata as a biofilter in a low-tech, low-cost, gravity generated water flow regime in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Aquaculture. 2006 Apr 28;254[1–4]:284–92. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Del Río M, Ramazanov Z, García-Reina G. Ulva rigida (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) tank culture as biofilters for dissolved inorganic nitrogen from fishpond effluents. Hydrobiologia . 1996 ;326–327(1):61–6. [CrossRef]

- Neori A, Cohen I, Gordin H. Ulva lactuca Biofilters for Marine Fishpond Effluents II. Growth Rate, Yield and C:N Ratio. Botanica Marina . 1991 Jan 1;34(6):483–90. [CrossRef]

- Vandermeulen H, Gordin H. Ammonium uptake using Ulva (Chlorophyta) in intensive fishpond systems: mass culture and treatment of effluent. J Appl Phycol. 1990 Dec;2(4):363–74. [CrossRef]

- Debusk TA, Ryther JH, Hanisak MD, Williams LD. Effects of seasonality and plant density on the productivity of some freshwater macrophytes. Aquat Bot. 1981 Jan 1;10(C):133–42. [CrossRef]

- Bruhn A, Dahl J, Nielsen HB, Nikolaisen L, Rasmussen MB, Markager S, et al. Bioenergy potential of Ulva lactuca: Biomass yield, methane production and combustion. Bioresour Technol. 2011 Feb 1;102(3):2595–604. [CrossRef]

- Neori A, Shpigel M, Ben-Ezra D. A sustainable integrated system for culture of fish, seaweed and abalone . Vol. 186, Aquaculture. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Henley J. W, Levavasseur G, Franklin LA, Lindley ST, Ramus J, Osmond CB. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1991. p. 75, 19–28 Diurnal responses of photosynthesis and fluorescence in Ulva rotundata acclimated to sun and shade in outdoor culture on JSTOR. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24825806.

- Henley WJ. Measurement and interpretation of photosynthetic light-response curves in algae in the context of photoinhibition and diel changes. J Phycol. 1993;29(6):729–39. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm C, Becker A, Toepel J, Vieler A, Rautenberger R. Photophysiology and primary production of phytoplankton in freshwater. Physiol Plant. 2004 Mar 1;120(3):347–57. [CrossRef]

- Savvashe P, Mhatre-Naik A, Pillai G, Palkar J, Sathe M, Pandit R, et al. High yield cultivation of marine macroalga Ulva lactuca in a multi-tubular airlift photobioreactor: A scalable model for quality feedstock. J Clean Prod. 2021 Dec 20; 329:129746. [CrossRef]

- Zou D. The effects of severe carbon limitation on the green seaweed, Ulva conglobata (Chlorophyta). J Appl Phycol. 2014 Dec 1;26(6):2417–24. [CrossRef]

- Fort A, McHale M, Cascella K, Potin P, Usadel B, Guiry MD, et al. Foliose Ulva Species Show Considerable Inter-Specific Genetic Diversity, Low Intra-Specific Genetic Variation, and the Rare Occurrence of Inter-Specific Hybrids in the Wild. J Phycol. 2021 Feb 1;57(1):219–33. [CrossRef]

- Schneider G, Figueroa FL, Vega J, Chaves P, Álvarez-Gómez F, Korbee N, et al. Photoprotection properties of marine photosynthetic organisms grown in high ultraviolet exposure areas: Cosmeceutical applications. Algal Res. 2020 Aug 1; 49:101956. [CrossRef]

- Vega J, Bonomi-Barufi J, Gómez-Pinchetti JL, Figueroa FL. Cyanobacteria and Red Macroalgae as Potential Sources of Antioxidants and UV Radiation-Absorbing Compounds for Cosmeceutical Applications. Marine Drugs 2020, Vol 18, Page 659 . 2020 Dec 21 ;18(12):659. [CrossRef]

- Vega J, Álvarez-Gómez F, Güenaga L, Figueroa FL, Gómez-Pinchetti JL. Antioxidant activity of extracts from marine macroalgae, wild-collected and cultivated, in an integrated multi-trophic aquaculture system. Aquaculture. 2020 May 30; 522:735088. [CrossRef]

- R Ramírez T, Cortés D, Mercado JM, Vargas-Yañez M, Sebastián M, Liger E. Seasonal dynamics of inorganic nutrients and phytoplankton biomass in the NW Alboran Sea. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2005 Dec 1;65(4):654–70. [CrossRef]

- Gomez Pinchetti JL, Del Campo Fernández E, Moreno Díez P, García Reina G. Nitrogen availability influences the biochemical composition and photosynthesis of tank-cultivated Ulva rigida (Chlorophyta). J Appl Phycol . 1998 ;10(4):383–9. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Bueno A, Korbee N, Santos R, Mata L, Schuenhoff A. Accumulation of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids in Asparagopsis armata Grown in Tanks with Fishpond Effluents of Gilthead Sea Bream, Sparus aurata. J World Aquac Soc . 2008 Oct 1 ;39(5):692–9. [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Pasini A, Aguirre-Von-Wobeser E, Figueroa FL. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis in Macrocystis pyrifera (Phaeophyceae), Chondrus crispus (Rhodophyceae) and Ulva lactuca (Chlorophyceae) in outdoor culture systems. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2000 Sep 1;57[2–3]:169–78. [CrossRef]

- Hanelt D, Figueroa FL. Physiological and Photomorphogenic Effects of Light on Marine Macrophytes. In 2012. p. 3–23. [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson L, Furbank RT, Chow WS. A simple alternative approach to assessing the fate of absorbed light energy using chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynth Res . 2004 ;82(1):73–81. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Domínguez-González B, Korbee N. Vulnerability and acclimation to increased UVB radiation in three intertidal macroalgae of different morpho-functional groups. Mar Environ Res. 2014 Jun 1; 97:30–8. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Bonomi Barufi J, Malta EJ, Conde-Álvarez R, Nitschke U, Arenas F, et al. Short-term effects of increasing CO2, nitrate and temperature on three mediterranean macroalgae: Biochemical composition. Aquat Biol. 2014 Nov 20; 22:177–93. [CrossRef]

- Longstaff BJ, Kildea T, Runcie JW, Cheshire A, Dennison WC, Hurd C, et al. An in situ study of photosynthetic oxygen exchange and electron transport rate in the marine macroalga Ulva lactuca (Chlorophyta). Photosynth Res. 2002 ;74(3):281–93. [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Pasini A, Figueroa FL. Effect of nitrate concentration on the relationship between photosynthetic oxygen evolution and electron transport rate in Ulva rigida (chlorophyta). J Phycol. 2005 Dec 16;41(6):1169–77. [CrossRef]

- Eilers PHC, Peeters JCH. A model for the relationship between light intensity and the rate of photosynthesis in phytoplankton. Ecol Modell. 1988 Sep 1;42[3–4]:199–215. [CrossRef]

- Morillas-España A, Lafarga T, Gómez-Serrano C, Acién-Fernández FG, González-López CV. Year-long production of Scenedesmus almeriensis in pilot-scale raceway and thin-layer cascade photobioreactors. Algal Res. 2020 Oct 1; 51:102069. [CrossRef]

- Shpigel M, Guttman L, Shauli L, Odintsov V, Ben-Ezra D, Harpaz S. Ulva lactuca from an Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) biofilter system as a protein supplement in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) diet. Aquaculture. 2017 Dec 1; 481:112–8. [CrossRef]

- Castro R, Piazzon MC, Zarra I, Leiro J, Noya M, Lamas J. Stimulation of turbot phagocytes by Ulva rigida C. Agardh polysaccharides. Aquaculture. 2006 Apr 28;254[1–4]:9–20. [CrossRef]

- Valente LMP, Gouveia A, Rema P, Matos J, Gomes EF, Pinto IS. Evaluation of three seaweeds Gracilaria bursa-pastoris, Ulva rigida and Gracilaria cornea as dietary ingredients in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) juveniles. Aquaculture. 2006 Mar 1;252(1):85–91. [CrossRef]

- Abdala-Díaz RT, García-Márquez J, Rico RM, Gómez-Pinchetti JL, Mancera JM, Figueroa FL, et al. Effects of a short pulse administration of Ulva rigida on innate immune response and intestinal microbiota in Sparus aurata juveniles. Aquac Res. 2021 Jul 1;52(7):3038–51. [CrossRef]

- García-Márquez J, Rico RM, Sánchez-Saavedra M del P, Gómez-Pinchetti JL, Acién FG, Figueroa FL, et al. A short pulse of dietary algae boosts immune response and modulates fatty acid composition in juvenile Oreochromis niloticus. Aquac Res. 2020 Nov 1;51(11):4397–409. [CrossRef]

- Rico RM, Tejedor-Junco MT, Tapia-Paniagua ST, Alarcón FJ, Mancera JM, López-Figueroa F, et al. Influence of the dietary inclusion of Gracilaria cornea and Ulva rigida on the biodiversity of the intestinal microbiota of Sparus aurata juveniles. Aquaculture International. 2016 Aug 1;24(4):965–84. [CrossRef]

- García IB, Ledezma AKD, Montaño EM, Leyva JAS, Carrera E, Ruiz IO. Identification and Quantification of Plant Growth Regulators and Antioxidant Compounds in Aqueous Extracts of Padina durvillaei and Ulva lactuca. Agronomy 2020, Vol 10, Page 866 . 2020 Jun 18 ;10(6):866. [CrossRef]

- Hamouda RA, Hussein MH, El-Naggar NEA, Karim-Eldeen MA, Alamer KH, Saleh MA, et al. Promoting Effect of Soluble Polysaccharides Extracted from Ulva spp. on Zea mays L. Growth. Molecules 2022, Vol 27, Page 1394 . 2022 Feb 18 ;27(4):1394. [CrossRef]

- Sekhouna D, Kies F, Elegbede I, Matemilola S, Zorriehzahra J, Hussein EK. Potential assay of two green algae Ulva lactuca and Ulva intestinalis as bio-fertilizers. Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research . 2021 Mar 10 ;9(4). [CrossRef]

- Figueroa FL, Korbee N, Abdala-Díaz R, Álvarez-Gómez F, Gómez-Pinchetti JL, Acién FG. Growing algal biomass using wastes. Bioassays: Advanced Methods and Applications. 2018 Jan 1;99–117. [CrossRef]

- Neveux N, Bolton JJ, Bruhn A, Roberts DA, Ras M, Barre S La, et al. The Bioremediation Potential of Seaweeds: Recycling Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Other Waste Products. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen MM, Bruhn A, Rasmussen MB, Olesen B, Larsen MM, Møller HB. Cultivation of Ulva lactuca with manure for simultaneous bioremediation and biomass production. J Appl Phycol. 2012 Jun;24(3):449–58. [CrossRef]

- Acién FG, Gómez-Serrano C, Morales-Amaral MM, Fernández-Sevilla JM, Molina-Grima E. Wastewater treatment using microalgae: how realistic a contribution might it be to significant urban wastewater treatment? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol . 2016 Nov 1 ;100(21):9013–22. [CrossRef]

- Posada JA, Brentner LB, Ramirez A, Patel MK. Conceptual design of sustainable integrated microalgae biorefineries: Parametric analysis of energy use, greenhouse gas emissions and techno-economics. Algal Res. 2016 Jul 1; 17:113–31. [CrossRef]

- Posadas E, Bochon S, Coca M, García-González MC, García-Encina PA, Muñoz R. Microalgae-based agro-industrial wastewater treatment: a preliminary screening of biodegradability. J Appl Phycol . 2014 Dec 1 ;26(6):2335–45. [CrossRef]

- Duarte CM, Wu J, Xiao X, Bruhn A, Krause-Jensen D. Can seaweed farming play a role in climate change mitigation and adaptation? Front Mar Sci. 2017 Apr 12;4(APR):245020. [CrossRef]

- Maulu S, Hasimuna OJ, Haambiya LH, Monde C, Musuka CG, Makorwa TH, et al. Climate Change Effects on Aquaculture Production: Sustainability Implications, Mitigation, and Adaptations. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2021 Mar 12; 5:609097. [CrossRef]

| Culture density | SGR (%day-1) |

Biomass production (kg FW) | Growth rate (g FW m-2 day-1) | Growth rate (g DW m-2 day-2) | Biomass production (kgFW/mg N) | Biomass production (kg FW/mg P) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6 kg m-2 | 5.94 | 7.7 | 36.7 | 6.23 | 0.611 | 8.280 | ||||||

| 0.8 kg m-2 | 4.9 | 8.2 | 38.1 | 6.48 | 0.651 | 8.817 | ||||||

| 1.0 kg m-2 | 4.07 | 8.3 | 39.1 | 6.64 | 0.659 | 8.925 |

| Culture density | Fv/Fm | ETRmax (µmol m-2 s-1) | αETR (µmol electrons/µmol photons) | Ek (µmol photons m-2 s-1) | NPQmax | ETRmax/NPQmax | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6 kg m-2 | 0.62 ± 0.010 B | 89.02 ± 12.16 A | 0.22 ± 0.008A | 412.00 ± 44.79 B | 0.74 ±0.074 C | 120.01 ± 15.34 A | ||||||

| 0.8 kg m-2 | 0.63 ± 0.010 B | 90.51 ± 11.62 A | 0.22 ± 0.034A | 352.81 ± 15.23 B | 1.41 ± 0.044 B | 64.31 ± 27.03 B | ||||||

| 1.0 kg m-2 | 0.68 ± 0.007 A | 94.82 ±5.69 A | 0.18 ± 0.009A | 512.46 ± 36.22 A | 1.51 ± 0.028 A | 62.69 ± 4.79 B |

| Culture density | SGR(%day-1) | Biomass production (kg FW) | Growth rate (g FW m-2 day-1) | Growth rate (g DW m-2 day-1) | Biomass production (kg FW/mg N) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-acclimatized | 4.07 | 8.30 | 38.10 | 6.48 | 0.66 | |||||

| Post-acclimatized | 4.80 | 10.1 | 47.62 | 8.10 | 0.79 |

| Algae condition |

Fv/Fm | ETRmax (µmol m-2 s-1) |

αETR (µmol electrons /µmol photons) | Ek (µmol photons m-2 s-1) | NPQmax | ETRmax/NPQmax (µmol m-2 s-1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-acclimation | 0.680 ± 0.007B | 94.89 ± 5.69B | 0.180 ± 0.009B | 512.460 ± 36.221B | 1.510 ± 0.028A | 62.69 ± 4.79B | ||||||

| Post-acclimation | 0.740 ± 0.006A | 184.73 ± 28.52A | 0.230 ± 0.009A | 852.340 ± 99.315A | 0.750 ± 0.027B | 245.98 ± 45.85A |

| Specie | Tank Volume (L) | Stocking density (kg FW m-2) | Growth (g L-1 day-1) | Water exchange (L day-1) | Growth rate (g DW m-2 day-1) | References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U. compressa | 3000 | 0,6-1 | 0.37-0.48 | 0 | 6,23-8 | This study | ||||||

| U. pseudorotundata | 200 | 1.2 | Not | 0 | 7.5-8 | [6] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 800 | 1-3 | 0.32-0.17 | 0 | 25-13 | [26] | ||||||

| U. rigida | 110 | 1.9 | Not | 2,4-96 | 44-73 | [42] | ||||||

| U. rigida | 1900 | 1.9 | Not | 14,4 | 48 | [43] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 600 | 1 | 0.19-0.63 | 34 | 11-38 | [44] | ||||||

| U. reticulata | 40 | 1 | 1.35-2.3 | 2040 | 46 | [45] | ||||||

| U. rigida | 750 | 2.5 | 0.09-0.32 | 2-12 | 40 | [46] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 600 | 2-6 | 0.24-0.42 | 4-16 | 55 | [47] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 600 | 1 | Not | 4-8 | 55 | [48] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 1700 | 1 | Not | 1-24 | 45-16 | [49] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 600 | 1-8 | 0.37-0.16 | 12 | 12,32 | [50] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 600 | 1.5 | 0.39 | 2 | 21,3 | [51] | ||||||

| U. lactuca | 900-1700 | 1 | 0.26-0.64 | 14-56 | 19 | [21] |

| SGR (%) | ETRmax (µmol m-2 s-1) | ETRmax/NPQmax (µmol m-2 s-1) | NUR (µmol N g-1 DW h-1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGR (%) | - | -0.2689 | 0.8147** | 0.9969** | ||||

| ETRmax | - | - | 0.0772 | -0.2605 | ||||

| ETRmax/NPQmax | - | - | - | 0.8353** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).