Submitted:

26 September 2024

Posted:

27 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Procedures

2.2. Fungal Material and Fermentation

2.3. Extraction and Isolation

2.4. NMR and ECD Calculation Methods

2.5. Fungicidal Activity Assay of Compounds 1-10 In Vitro

2.6. Fungicidal Activity Assay of Compound 10 In Vivo

3. Results

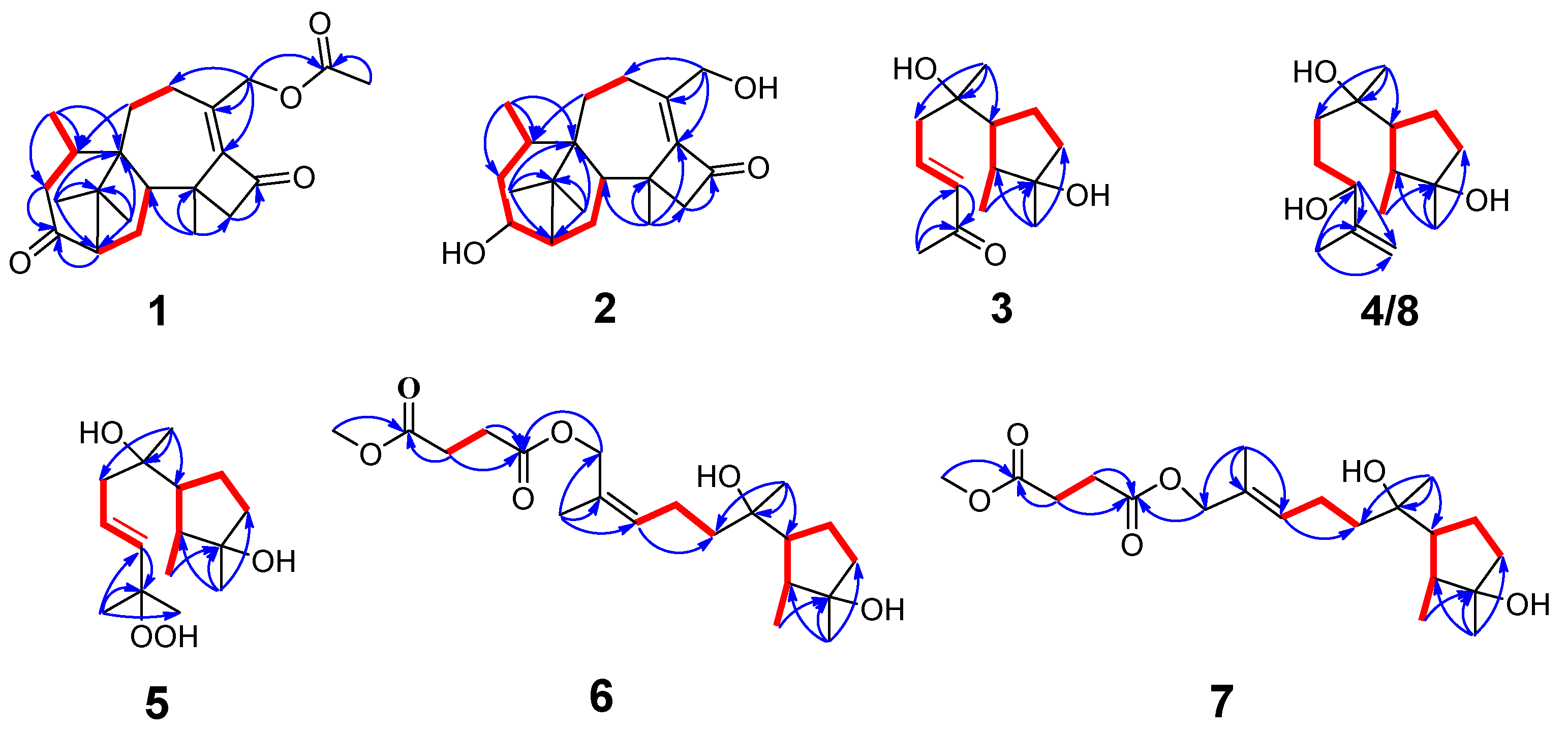

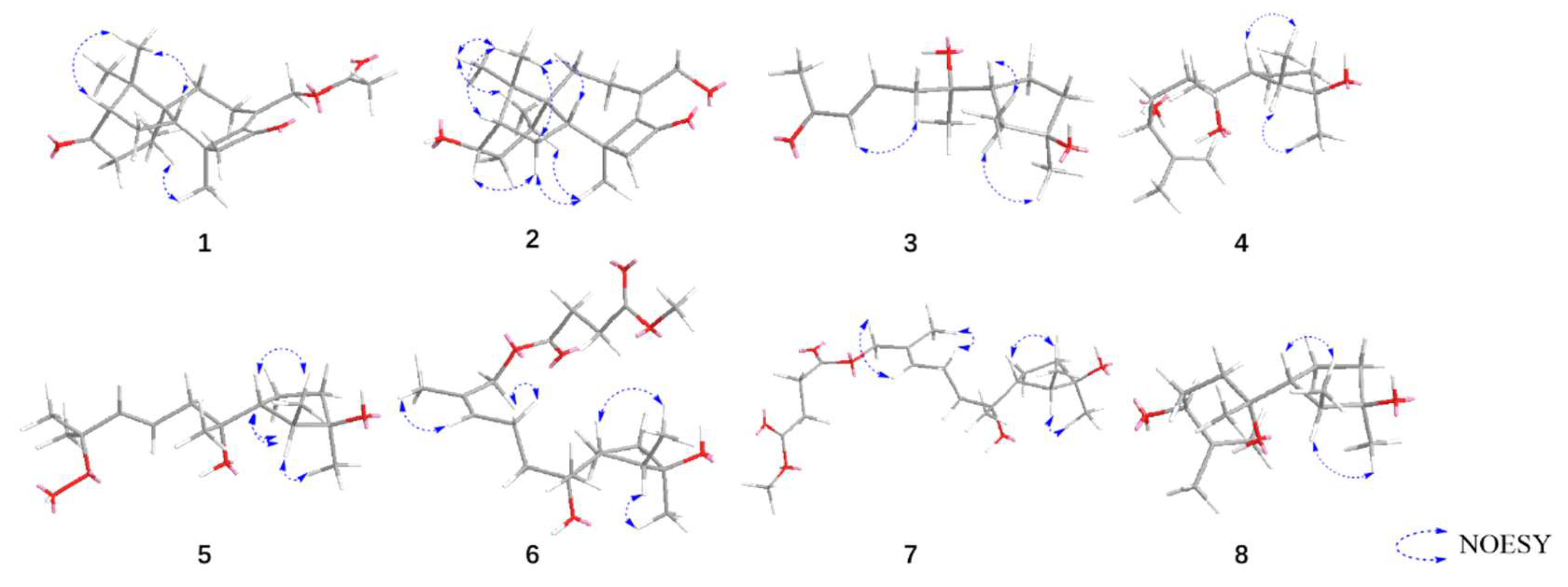

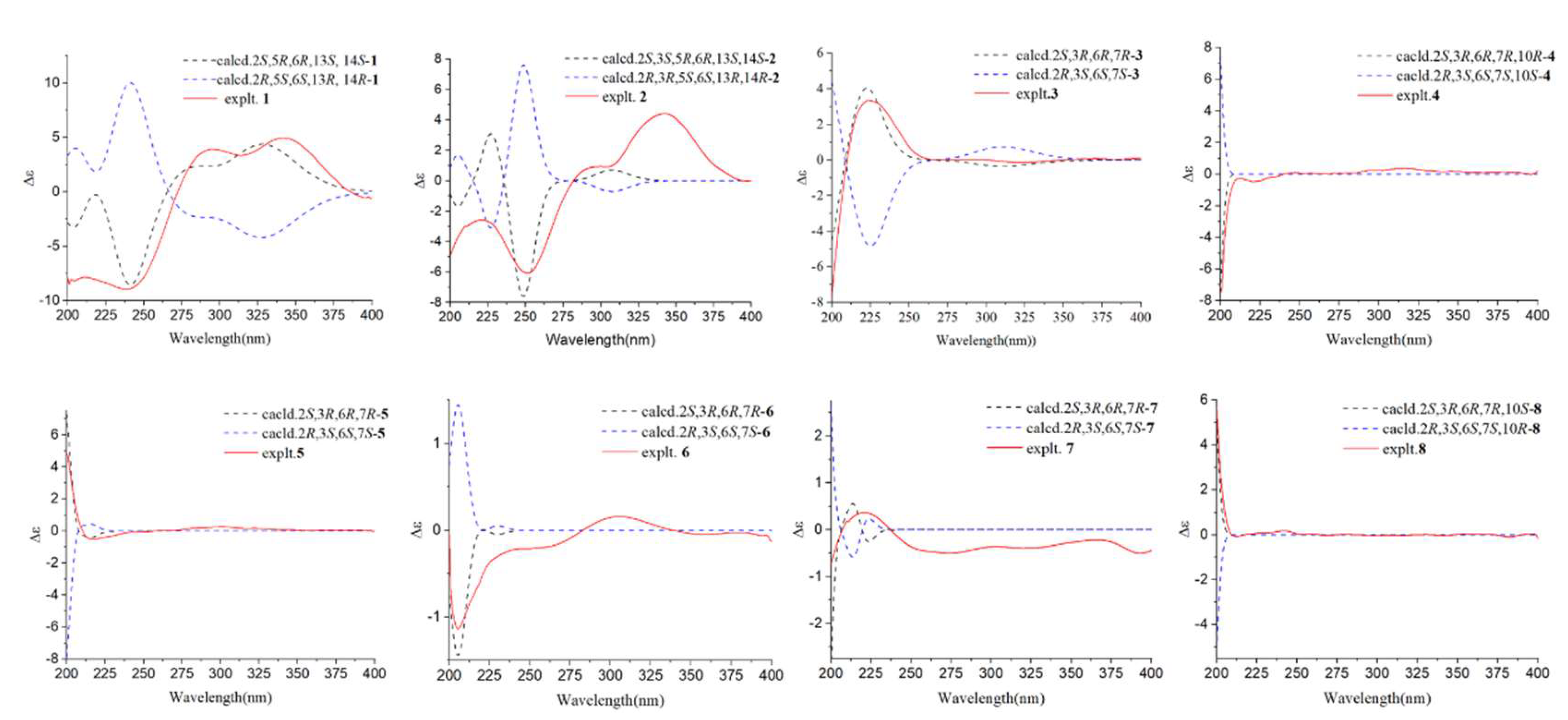

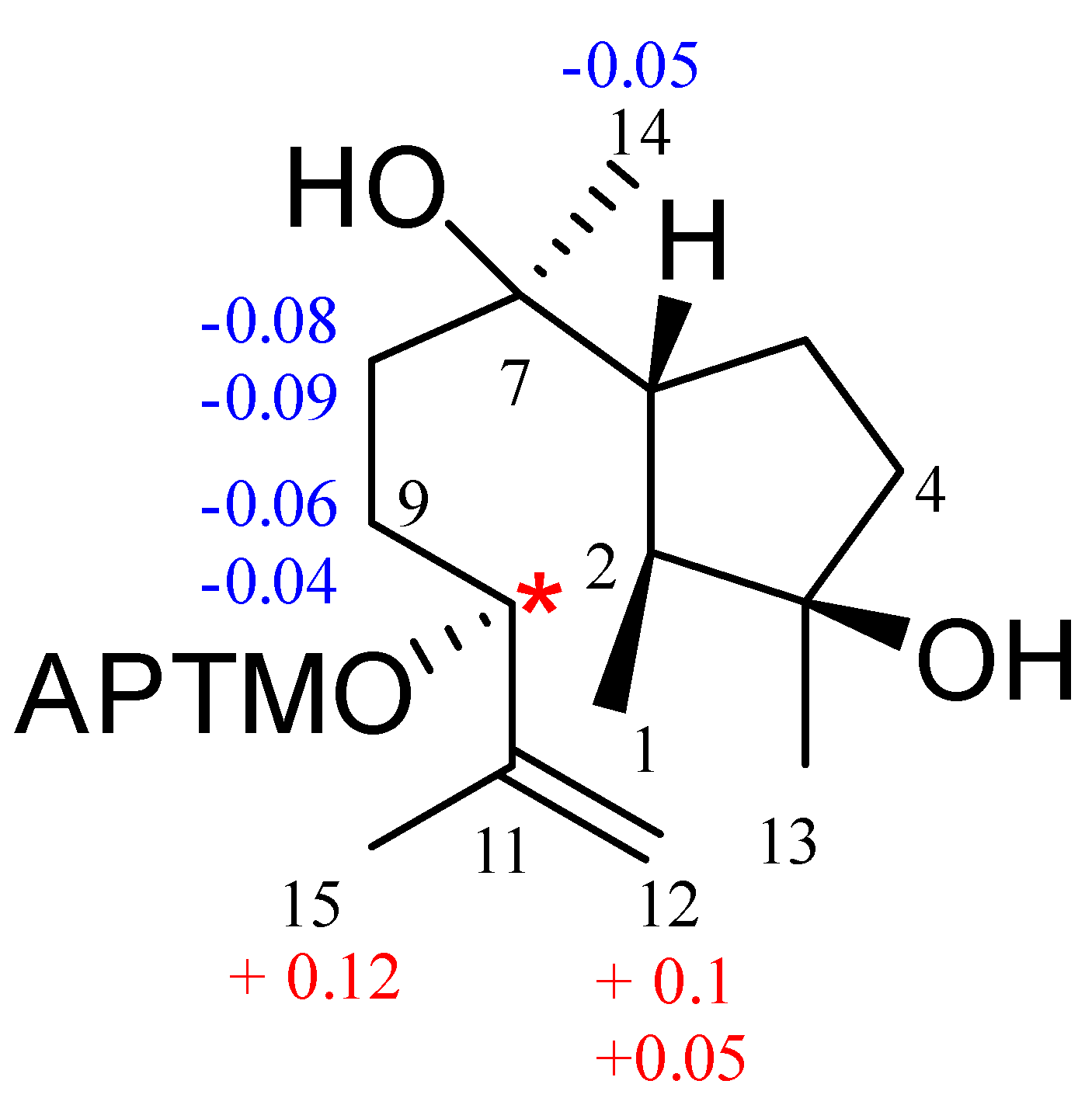

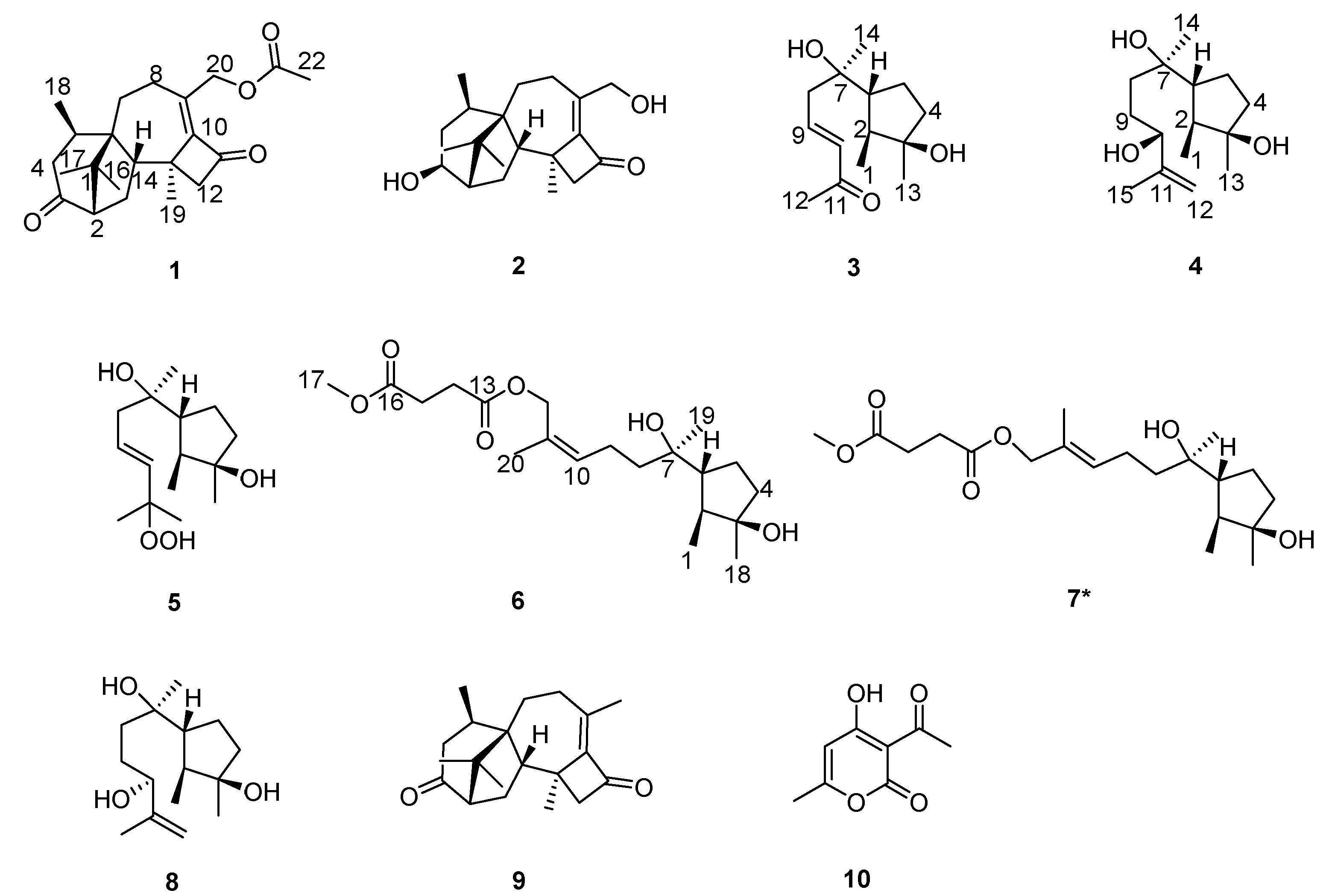

3.1. Structural Identification of Compounds

3.2. Fungicidal Activities of Compounds 1-10 In Vitro

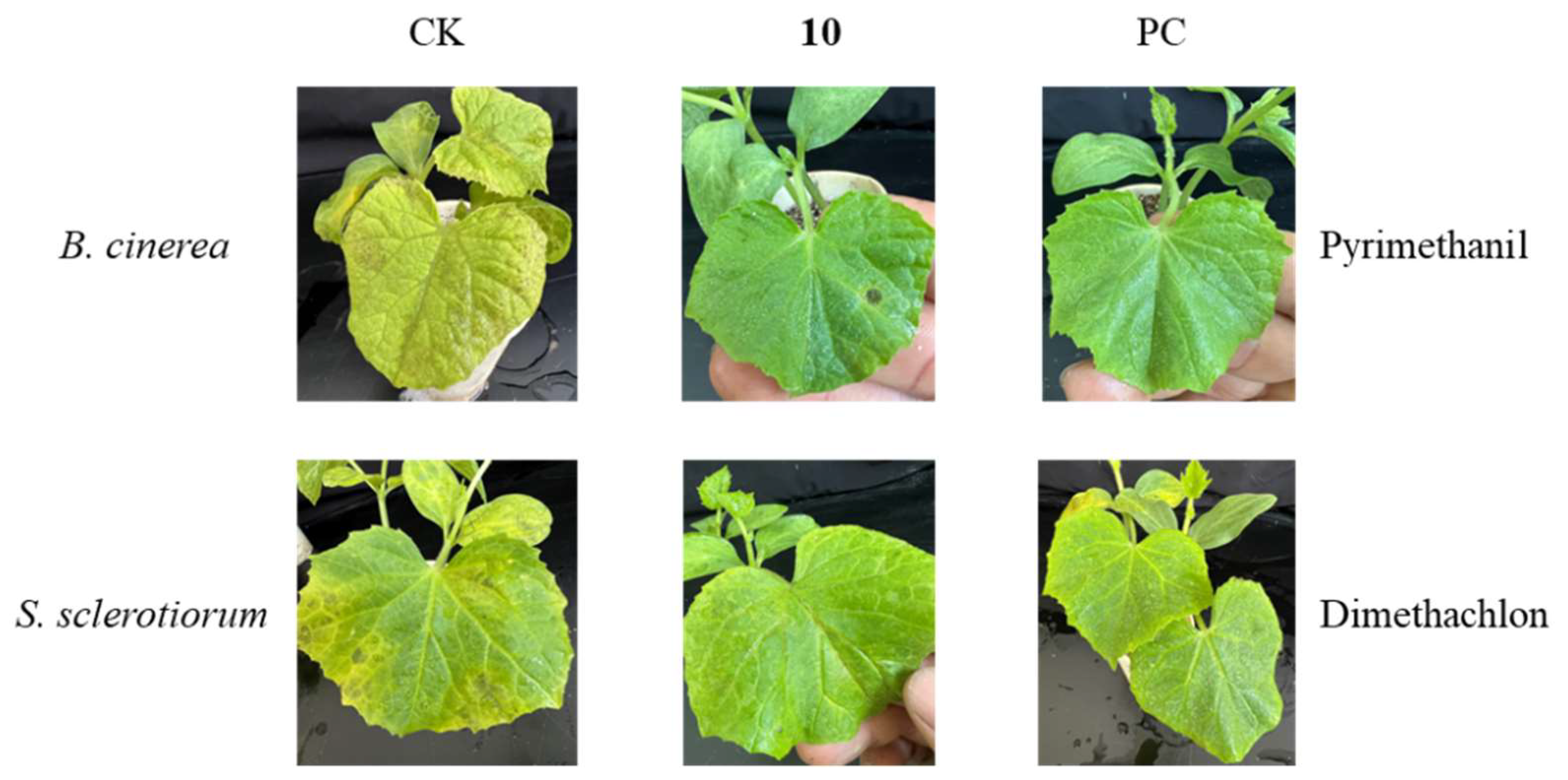

3.3. Fungicidal Activities of Compound 10 In Vivo

| Preventative efficiency (%) | ||

| pathogenic fungi | Botrytis cinerea | Sclerotinia sclerotiorum |

| 10 | 65.8 % | 49.1 % |

| PC | 88.6 % | 100 % |

4. Discussion

5. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salazar, B.; Ortiz, A.; Keswani, C.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S.; Pratap, S. S.; Rekadwad, B.; Borriss, R.; Jain A.; Singh HB.; Sansinenea E. Bacillus spp. as Bio-factories for Antifungal Secondary Metabolites: Innovation Beyond Whole Organism Formulations. Microb Ecol, 2023; 86, 1-24. DOI: 10.1007/s00248-022-02044-2. [CrossRef]

- Syed Ab Rahman, S.F.; Singh, E.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Schenk, P.M. Emerging microbial biocontrol strategies for plant pathogens. Plant Sci, 2018, 267, 102-111. DOI: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.11.012. [CrossRef]

- Saldaña-Mendoza, S.A.; Pacios-Michelena, S.; Palacios-Ponce, A.S.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Aguilar, C.N. Trichoderma as a biological control agent: mechanisms of action, benefits for crops and development of formulations. World J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2023; 39, 269. DOI: 10.1007/s11274-023-03695-0. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jennings, A. Worldwide Regulations of Standard Values of Pesticides for Human Health Risk Control: A Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2017, 14 (7), 826. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph14070826. [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.; Khadka, R.; Doni, F.; Uphoff, N. Benefits to Plant Health and Productivity from Enhancing Plant Microbial Symbionts. Front Plant Sci, 2021, 11, 610065. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2020.610065. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Shen, D.; Fan, H.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Chen, L. Virulent and attenuated strains of Trichoderma citrinoviride mediated resistance and biological control mechanism in tomato. Front Plant Sci, 2023, 14, 1179605. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1179605. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Y.; Ribera, J.; Schwarze F.W.M.R.; De France, K. Biotechnological development of Trichoderma-based formulations for biological control. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2023, 107 (18), 5595-5612. DOI: 10.1007/s00253-023-12687-x. [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jaroszuk-Ściseł, J. Trichoderma: The Current Status of Its Application in Agriculture for the Biocontrol of Fungal Phytopathogens and Stimulation of Plant Growth. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23 (4), 2329. DOI: 10.3390/ijms23042329. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, J.; Chen, J. Trichoderma and its role in biological control of plant fungal and nematode disease. Front Microbiol, 2023, 14, 1160551. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1160551. [CrossRef]

- Bolzonello, A.; Morbiato, L.; Tundo, S.; Sella, L.; Baccelli I.; Echeverrigaray S.; Musetti R.; De Zotti M.; Favaron F.; Peptide Analogs of a Trichoderma Peptaibol Effectively Control Downy Mildew in the Vineyard. Plant Dis, 2023, 107 (9), 2643-2652. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS-09-22-2064-RE. [CrossRef]

- El-Hasan, A.; Walker, F.; Klaiber, I.; Schöne, J. P.; fannstiel, J.; Voegele, R.T. New Approaches to Manage Asian Soybean Rust (Phakopsora pachyrhizi) Using Trichoderma spp. or Their Antifungal Secondary Metabolites. Metabolites, 2022, 12 (6), 507. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12060507. [CrossRef]

- Scharf, D.H.; Brakhage, A.A.; Mukherjee, P.K. Gliotoxin--bane or boon? Environ Microbiol, 2016, 18 (4), 1096-1109. DOI: 10.1111/1462-2920.13080. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Tang, Z.; Gan, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Gao, C.; Zhao, L.; Chai, L.; Liu, Y. 18-Residue Peptaibols Produced by the Sponge-Derived Trichoderma sp. GXIMD 01001. J Nat Prod, 2023, 86 (4), 994-1002. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.3c00014. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ortega, R.; Guillén-Alonso, H.; Alcalde-Vázquez, R.; Ramírez-Chávez, E.; Molina-Torres, J.; Winkler, R. In Vivo Low-Temperature Plasma Ionization Mass Spectrometry (LTP-MS) Reveals Regulation of 6-Pentyl-2H-Pyran-2-One (6-PP) as a Physiological Variable during Plant-Fungal Interaction. Metabolites, 2022, 12 (12), 1231. DOI: 10.3390/metabo12121231. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.P.; Shi, Z.Z.; Fang, S.T.; Song, Y.P.; Ji, N.Y. Lipids and Terpenoids from the Deep-Sea Fungus Trichoderma lixii R22 and Their Antagonism against Two Wheat Pathogens. Molecules, 2023, 28 (17), 6220. DOI: 10.3390/molecules28176220. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Li, Q.L.; Yang, Y.B.; Liu, K.; Miao, C.P.; Zhao, L.X.; Ding, Z.T. Koninginins R-S from the endophytic fungus Trichoderma koningiopsis. Nat Prod Res, 2017, 31 (7), 835-839. DOI: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1250086. [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, V.; Kumar, J.; Rana, V.S.; Sati, O.P.; Walia, S. Comparative evaluation of two Trichoderma harzianum strains for major secondary metabolite production and antifungal activity. Nat Prod Res, 2015, 29 (10), 914-920. DOI: 10.1080/14786419.2014.958739. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.A.; Najeeb, S.; Hussain, S.; Xie, B.; Li, Y. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Trichoderma spp. against Phytopathogenic Fungi. Microorganisms, 2020, 8 (6), 817. DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms8060817. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Z.; Liu, X.H.; Li, X.N.; Ji, N.Y. Antifungal and Antimicroalgal Trichothecene Sesquiterpenes from the Marine Algicolous Fungus Trichoderma brevicompactum A-DL-9-2. J Agric Food Chem, 2020, 68 (52), 15440-15448. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05586. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Shi, L.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ding, G.; Chen, L. Structures and Biological Activities of Secondary Metabolites from the Trichoderma genus (Covering 2018-2022). J Agric Food Chem, 2023, 71 (37), 13612-13632. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c04540. [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.; Kuang, Q.X.; Li, Q.Z.; Huang, L.J.; Guo, W.X.; Gong, L.Q.; Dai, Y.F.; Wang, L.; Gu, Y.C.; Wang, D.; Deng, Y.; Guo, DL. Aureonitol Analogues and Orsellinic Acid Esters Isolated from Chaetomium elatum and Their Antineuroinflammatory Activity. J Nat Prod, 2021, 84 (12), 3044-3054. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00783. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Q.X.; Luo, Y.; Lei, L.R.; Guo, W.X.; Li, X.A.; Wang, Y.M.; Huo, X.Y.; Liu, M.D.; Zhang, Q.; Feng D.; Huang, L.J.; Wang, D.; Gu, Y.C.; Deng, Y.; Guo, D.L. Hydroanthraquinones from Nigrospora sphaerica and Their Anti-inflammatory Activity Uncovered by Transcriptome Analysis. J Nat Prod, 2022, 85 (6), 1474-1485. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c01141. [CrossRef]

- Hoye, T. R.; Jeffrey, C. S.; Shao, F. Mosher ester analysis for the determination of absolute configuration of stereogenic (chiral) carbinol carbons. Nat Protoc, 2007, 2 (10), 2451-2458. DOI: 10.1038/nprot.2007.354. [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.; Yang, W.; Chen, T.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Said, G.; Sun, B.; Wang, B.; She, Z. Griseofulvin enantiomers and bromine-containing griseofulvin derivatives with antifungal activity produced by the mangrove endophytic fungus Nigrospora sp. QQYB1. Mar Life Sci Technol, 2023, 6 (1), 102-114. DOI: 10.1007/s42995-023-00210-0. [CrossRef]

- Goto, H.; Osawa, E. An efficient algorithm for searching low-energy conformers of cyclic and acyclic molecules. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans, 1993, 2, 187−198. DOI: 10.1039/P29930000187. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; et al. 2016, Gaussian 16, Revision B.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT.

- Li, Y.H.; Mándi, A.; Li, H.L.; Li, X.M.; Li, X.; Meng, L.H.; Yang, S.Q.; Shi, X.S.; Kurtán, T.; Wang, B.G. Isolation and characterization of three pairs of verrucosidin epimers from the marine sediment-derived fungus Penicillium cyclopium and configuration revision of penicyrone A and related analogues. Mar Life Sci Technol, 2023, 5 (2), 223-231. DOI: 10.1007/s42995-023-00173-2. [CrossRef]

- Grimblat, N.; Zanardi, M.M.; Sarotti, A.M. Beyond DP4: an Improved Probability for the Stereochemical Assignment of Isomeric Compounds using Quantum Chemical Calculations of NMR Shifts. J Org Chem, 2015, 80 (24), 12526-12534. DOI: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02396. [CrossRef]

- Bian, Q.; Zhao, R.Q.; Peng, X.J.; Gao, L.J.; Zhou, G.N.; Yu, S.J.; Zhao, W.G. Design, Synthesis, and Fungicidal Activities of Novel Piperidyl Thiazole Derivatives Containing Oxime Ether or Oxime Ester Moieties, J Agric Food Chem, 2021, 69 (13), 3848-3858. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07581. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.P.; Liu, X.H.; Shi, Z.Z.; Miao, F.P.; Fang, S.T.; Ji, N.Y. Bisabolane, cyclonerane, and harziane derivatives from the marine-alga-endophytic fungus Trichoderma asperellum cf44-2. Phytochemistry, 2018, 152, 45-52. DOI: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.04.017. [CrossRef]

- González-Menéndez, V.; Pérez-Bonilla, M.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; et al. Multicomponent Analysis of the Differential Induction of Secondary Metabolite Profiles in Fungal Endophytes. Molecules, 2016, 21 (2), 234. DOI: 10.3390/molecules21020234. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Structures and Biological Activities of Secondary Metabolites from Trichoderma harzianum. Mar Drugs, 2022, 20 (11), 701. DOI: 10.3390/md20110701. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Kumar, A.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S.; et al. Trichoderma Species: Our Best Fungal Allies in the Biocontrol of Plant Diseases-A Review. Plants (Basel), 2023, 12 (3), 432. DOI: 10.3390/plants12030432. [CrossRef]

- Carrero-Carrón, I.; Trapero-Casas, J.L.; Olivares-García, C.; et al. Trichoderma asperellum is effective for biocontrol of Verticillium wilt in olive caused by the defoliating pathotype of Verticillium dahliae. Crop Prot, 2016, 88, 45-52. DOI: 10.1016/j.cropro.2016.05.009. [CrossRef]

- Guo R, Ji.S.; Wang, Z.; et al. Trichoderma asperellum xylanases promote growth and induce resistance in poplar. Microbiol Res, 2021, 248, 126767. DOI: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126767. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Kumar, J. Characterization of volatile secondary metabolites from Trichoderma asperellum. JANS, 2017, 9, 954-959. DOI: 10.31018/jans.v9i2.1303. [CrossRef]

- Alfiky, A.; Weisskopf, L. Deciphering Trichoderma-Plant-Pathogen Interactions for Better Development of Biocontrol Applications. J. Fungi, 2021, 7 (1), 61. DOI: 10.3390/jof7010061. [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Kumar, A.; Tittal, R.K.; et al. Dehydroacetic acid a privileged medicinal scaffold: A concise review. Arch pharm, 2023, 357 (2), e2300512. DOI: 10.1002/ardp.202300512. [CrossRef]

| pos | 1 | 2 | 6 | 7 |

| δC, type | δC, type | δC, type | δC, type | |

| 1 | 49.7, C | 45.8, C | 14.7, CH3 | 14.7, CH3 |

| 2 | 59.4, CH | 49.6, CH | 44.4, CH | 44.4, CH |

| 3 | 214.2, C | 74.4, CH | 81.4, C | 81.5, C |

| 4 | 42.7, CH2 | 34.3, CH2 | 40.5, CH2 | 40.5, CH2 |

| 5 | 30.1, CH | 28.2, CH | 24.5, CH2 | 24.5, CH2 |

| 6 | 51.8, C | 50.4, C | 54.6, CH | 54.4, CH |

| 7 | 30.3, CH2 | 30.4, CH2 | 74.8, C | 74.9, C |

| 8 | 23.8, CH2 | 24.6, CH2 | 40.5, CH2 | 40.0, CH2 |

| 9 | 141.1, C | 154.0, C | 22.5, CH2 | 22.5, CH2 |

| 10 | 153.0, C | 148.9, C | 131.2, CH | 129.9, CH |

| 11 | 196.5, C | 200.2, C | 129.9, C | 130.2, C |

| 12 | 60.2, CH2 | 58.7, CH2 | 63.6, CH2 | 70.6, CH2 |

| 13 | 40.4, C | 40.4, C | 172.4, C | 172.3, C |

| 14 | 52.9, CH | 51.4, CH | 29.1, CH2 | 29.1, CH2 |

| 15 | 26.7, CH2 | 27.6, CH2 | 29.3, CH2 | 29.3, CH2 |

| 16 | 25.2, CH3 | 26.8, CH3 | 172.9, C | 172.9, C |

| 17 | 23.4, CH3 | 23.6, CH3 | 52.0, CH3 | 52.0, CH3 |

| 18 | 21.1, CH3 | 21.4, CH3 | 26.2, CH3 | 26.2, CH3 |

| 19 | 20.6, CH3 | 21.6, CH3 | 25.0, CH3 | 25.1, CH3 |

| 20 | 63.3, CH2 | 67.3, CH2 | 21.6, CH3 | 21.6, CH3 |

| 21 | 170.9, C | |||

| 22 | 21.0, CH3 |

| pos | 1 | 2 | 6 | 7 |

| δH (J in Hz) | δH (J in Hz) | δH (J in Hz) | δH (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 1.04, d (6.8) | 1.05, d (6.8) | ||

| 2 | 2.29, m | 1.84, dd (8.2, 3.7) | 1.60, m | 1.61, m |

| 3 | 3.98, dd (3.6, 6.6) | |||

| 4a 4b |

2.90, m 2.09, m |

2.42, d (16.9) 1.50, d (15.3) |

1.68, m 1.56, m |

1.69, m, 1H 1.57, m |

| 5a 5b |

2.90, m | 2.45, m | 1.85, m 1.55, m |

1.86, m 1.55, m |

| 6 | 1.84, m | 1.85, m | ||

| 7a 7b |

1.97, m 1.40, m |

1.97, m 1.25, m |

||

| 8a 8b |

2.29, m |

2.40, m 2.00, m |

1.49, m |

1.51, t (8.4) |

| 9a 9b |

2.19, m 2.12, m |

2.12, m |

||

| 10 | 5.41, t (6.7) | 5.47, td (7.2, 1.4) | ||

| 12a 12b |

2.66, d (16.6) 2.51, d (16.4) |

2.57, d (16.7) 2.46, d (16.9) |

4.66, d (11.9) 4.60, d (11.9) |

4.48, s |

| 14 | 2.52, m | 2.14, dd (11.3, 8.9) | 2.64, m | 2.65, m |

| 15a 15b |

2.05, m 1.54, m |

1.90, m 1.09, dd (14.0, 9.3) |

2.64, m |

2.65, m |

| 16 | 1.00, s | 0.87, s | ||

| 17 | 1.01, s | 1.33, s | 3.69, s | 3.69, s |

| 18 | 1.13, d (7.2) | 1.18, d (7.6) | 1.26, s | 1.26, s |

| 19 | 1.54, s | 1.51, s | 1.15, s | 1.17, s |

| 20a 20b |

5.12, d (12.8) 4.76, d (12.9) |

4.40, d (18) 4.20, d (18.2) |

1.74, d (1.5) |

1.66, d (1.5) |

| 22 | 2.10, s |

| pos | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| δC, type | δC, type | δC, type | δC, type | |

| 1 | 14.6, CH3 | 14.7, CH3 | 14.5, CH3 | 14.6, CH3 |

| 2 | 44.6, CH | 44.5, CH | 44.6, CH | 44.5, CH |

| 3 | 81.4, C | 81.5, C | 81.6, C | 81.4, C |

| 4 | 40.4, CH2 | 40.5, CH2 | 40.4, CH2 | 40.5, CH2 |

| 5 | 24.6, CH2 | 24.5, CH2 | 24.5, CH2 | 24.5, CH2 |

| 6 | 54.9, CH | 54.8, CH | 54.4, CH | 54.8, CH |

| 7 | 75.0, C | 74.7, C | 74.8, C | 74.8, C |

| 8 | 43.8, CH2 | 36.6, CH2 | 43.6, CH2 | 35.8, CH2 |

| 9 | 144.1, CH | 29.4, CH2 | 126.7, CH2 | 29.1, CH2 |

| 10 | 134.2, CH | 76.7, CH | 138.1, CH | 76.0, CH |

| 11 | 198.5, C | 147.7, C | 82.0, C | 147.7, C |

| 12 | 27.2, CH3 | 111.2, CH2 | 24.6, CH3 | 111.0, CH2 |

| 13 | 26.2, CH3 | 26.2, CH3 | 26.1, CH3 | 26.2, CH3 |

| 14 | 25.9, CH3 | 25.2, CH3 | 25.2, CH3 | 25.2, CH3 |

| 15 | 17.8, CH3 | 24.2, CH3 | 18.2, CH3 |

| pos | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| δH (J in Hz) | δH (J in Hz) | δH (J in Hz) | δH (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 1.06, d (6.8) | 1.05, d (= 6.7) | 1.04, d (6.7) | 1.04, d (6.9) |

| 2 | 1.62, m | 1.62, m | 1.60, m | 1.59, m |

| 4a 4b |

1.72, m 1.58, m |

1.69, m 1.57, m |

1.68, m 1.56, m |

1.69, m 1.57, m |

| 5a 5b |

1.91, m 1.58, m |

1.86, m 1.56, m |

1.86, m 1.57, m |

1.87, m 1.56, m |

| 6 | 1.86, m | 1.86, m | 1.86, m | 1.87, m |

| 8a 8b |

2.45, dd (14.8, 7.6) 2.36, dd (13.9, 8.2) |

1.60, m 1.48, m |

2.23, m |

1.57, m 1.50, m |

| 9a 9b |

6.88, m |

1.65, m |

5.74, dt (15.0, 7.4) |

1.71, m 1.61, m |

| 10 | 6.13, d (16.0) | 4.05, dd (7.2, 5.3) | 5.63, d (15.8) | 4.09, dd (7.6, 4.6) |

| 12a 12b |

2.27, s |

4.95, s 4.84, s |

1.32, s |

4.97, s 4.86, s |

| 13 | 1.27, s | 1.26, s | 1.25, s | 1.26, s |

| 14 | 1.19, s | 1.16, s | 1.14, s | 1.16, s |

| 15 | 1.74, s | 1.33, s | 1.72, s |

| compound | Fungicidal activities (%) at 50 μg/mL | |||||

| A.S. | F.G. | P.C. | S.S. | B.C. | R.S. | |

| 1 | 52.2 ±2.3 | 56.5 ±4.2 | 45.7 ±1.5 | 85.9 ±3.7 | 44.7 ±5.1 | 19.3 ±0.6 |

| 2 | 39.1 ±3.4 | 17.4 ±1.1 | 21.7 ±32.6 | 73.1 ±2.6 | 26.3 ±2.5 | 46.5 ±4.5 |

| 3 | 56.5 ±4.2 | 34.8 ±2.0 | 42.8 ±2.5 | 64.1 ±2.5 | 81.6 ±3.4 | 28.1 ±3.4 |

| 4 | 47.8 ±1.7 | 23.9 ±1.6 | 32.6 ±2.4 | 73.1 ±4.2 | 42.1 ±2.6 | 15.1 ±2.3 |

| 5 | 45.8 ±2.4 | 26.1 ±2.5 | 23.9 ±2.2 | 67.9 ±3.4 | 39.5 ±4.3 | 19.3 ±3,6 |

| 6 | 30.4 ±3.5 | 84.8 ±3.1 | 26.1 ±1.1 | 75.6 ±1.8 | 47.4 ±2.1 | 17.4 ±2.1 |

| 7 | 34.8 ±1.9 | 15.2 ±1.4 | 35.0 ±3.1 | 51.3 ±2.3 | 34.2 ±1.4 | 14.0 ±1.5 |

| 8 | 30.4 ±2.4 | 28.3 ±2.6 | 37.0 ±2.2 | 53.8 ±4.1 | 26.3 ±2.6 | 51.2 ±3.9 |

| 9 | 12.5 ±1.2 | 23.1 ±3.4 | 9.4 ±0.6 | 76.1 ±3.5 | 46.2 ±3.6 | 59.4 ±4.3 |

| 10 | 56.3 ±3.6 | 38.5 ±3.2 | 28.1 ±1.8 | 100.0 ±0.0 | 100.0 ±0.0 | 82.8 ±2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).