Introduction

ME is a complex and debilitating illness of unclear etiology, marked by persistent fatigue, post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive deficits (

“brain fog”), autonomic instability, and immune dysfunction [

1]. Its heterogeneity has made pathophysiological understanding and treatment development challenging. Growing evidence points to metabolic and immunological disturbances in ME patients. Metabolomic studies have repeatedly found abnormalities in lipid metabolism – for example, significantly reduced phosphatidylcholine and choline levels in ME patients compared to healthy controls [

2]. These membrane lipid deficits may impair mitochondrial function and cellular integrity. Immune studies have identified chronic low-grade inflammation and shifts in cytokine profiles [

3]. Notably, autonomic nervous system irregularities are common, with some patients exhibiting features of sympathetic overactivation (such as orthostatic tachycardia or hypertension) and others showing blunted sympathetic output (orthostatic hypotension or low plasma norepinephrine) [

4,

5]. This spectrum suggests that distinct subtypes of ME exist, possibly rooted in differing underlying biological perturbations.

A unifying hypothesis is needed to explain how a precipitating event – often an infection or stressor – could lead to both metabolic derailment and autonomic dysregulation, resulting in ME. This paper presents a systems-level hypothesis centred on lipid metabolic dysfunction and secondary catecholamine imbalance.

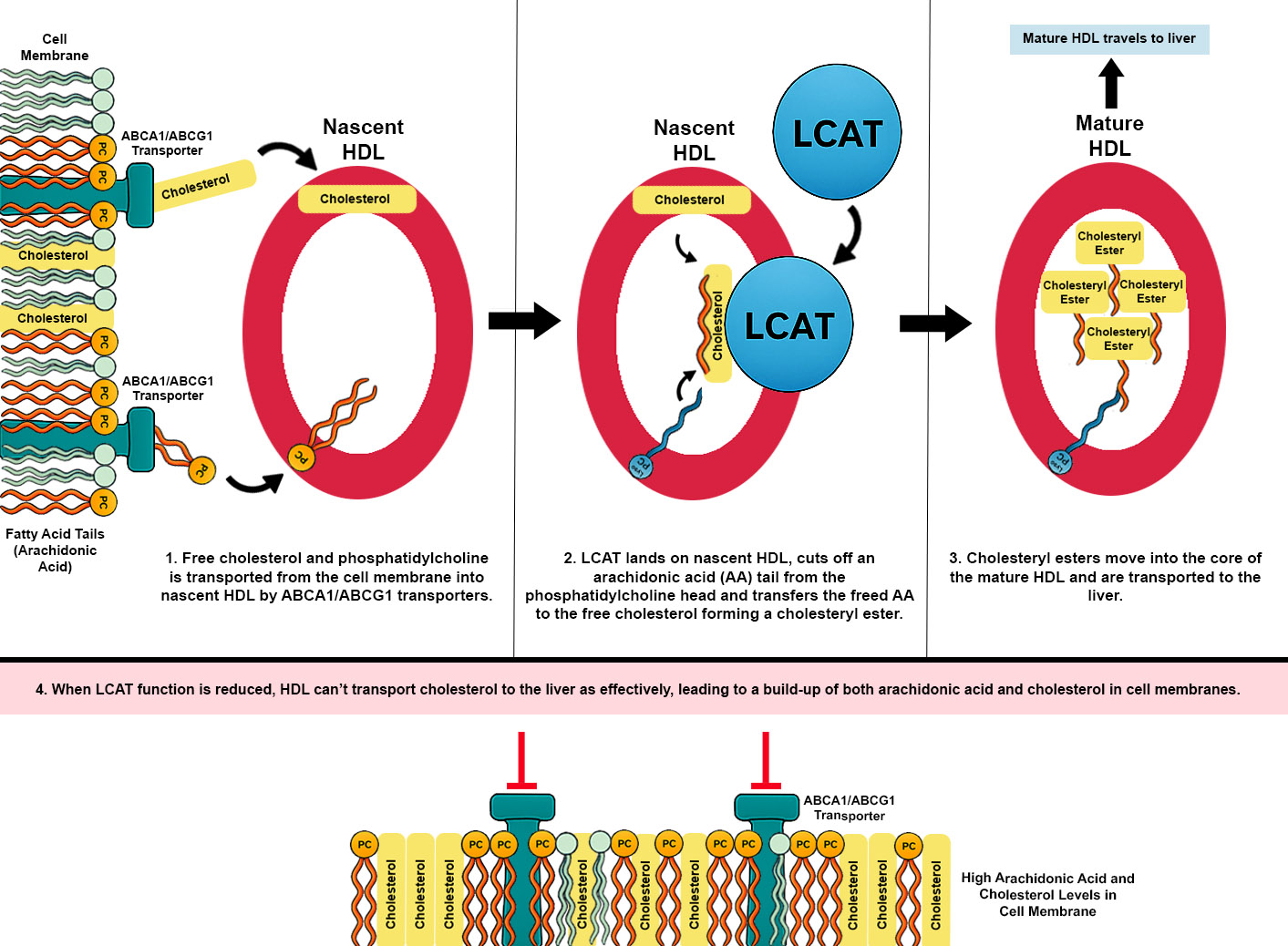

This hypothesis proposes that dysfunction of lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) is a common underlying feature across ME subtypes, while differences in phosphatidylcholine (PC) availability—normal in some patients and reduced in others due to impaired synthesis, breakdown, or transport—shape distinct disease trajectories through their impact on membrane structure and lipid signaling. LCAT is essential for cholesterol homeostasis by esterifying free cholesterol for transport via high-density lipoproteins (HDL); reduced activity can lead to cholesterol accumulation in cell membranes. At the same time, LCAT normally removes arachidonic acid (AA) from phosphatidylcholine and transports it to the liver, so impaired activity results in a build-up of AA in peripheral tissues, including neuronal, endothelial, immune, and adipose membranes. Upon activation of phospholipase A₂, there is excessive arachidonic acid release and production of downstream eicosanoids and leukotrienes.

By integrating these elements, this hypothesis provides a framework that can account for the constellation of ME symptoms and their variability among patients. Below, we detail the mechanistic links in this model: how LCAT and phosphatidylcholine disruptions might arise and lead to immune changes; how excess AA from membrane phospholipids could drive inflammatory mediators and hormonal imbalances; how PPAR-γ activation (or lack thereof) might moderate these effects; how insulin and cholesterol metabolism differences between central and peripheral tissues could translate into altered NE homeostasis; and how these factors collectively produce the observed subgroups of ME. We then relate these concepts to emerging observations in post-COVID ME and propose diagnostic and therapeutic directions.

Lecithin–Cholesterol Acyltransferase Dysfunction and Cholesterol Accumulation

Lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) is an enzyme that esterifies free cholesterol on high-density lipoproteins (HDL), using phosphatidylcholine (PC) as a fatty acid donor. This reaction is essential for reverse cholesterol transport—the process by which cholesterol is removed from peripheral tissues and returned to the liver via HDL. When LCAT activity is impaired, free (unesterified) cholesterol accumulates in plasma and cell membranes due to reduced esterification and clearance. While rare genetic LCAT deficiency syndromes are well described, a milder yet functionally significant impairment may occur more commonly in the population due to common gene variants such as

LCAT rs4986970 AA, which has been associated with altered HDL metabolism and may contribute to LCAT dysfunction in ME patients [

6].

A study by Kennedy et al. (2005) reported that patients with ME exhibit significantly reduced HDL cholesterol levels and elevated concentrations of oxidised low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL), along with increased markers of lipid peroxidation such as malondialdehyde (MDA)[

7]. These findings are consistent with impaired activity of LCAT because reduced LCAT function impairs HDL particle formation, leading to decreased HDL-C concentrations and diminished capacity to buffer and detoxify oxidised lipids. In parallel, the accumulation of unesterified cholesterol in low-density lipoproteins increases their susceptibility to oxidative modification, contributing to higher oxLDL levels. The observed lipid profile and oxidative imbalance in ME patients therefore support a model in which compromised LCAT activity contributes to disordered lipid metabolism and oxidative stress, both of which may play a role in the pathophysiology of the disease.

Cholesterol accumulation in immune cell membranes may have negative affects on their function and one example of this is microglial cells in the brain. Increased cholesterol accumulation in microglial cell membranes can significantly impact their function and contribute to neuroinflammation. Cholesterol is essential for maintaining membrane fluidity and facilitating signal transduction; however, excessive accumulation disrupts these processes. Elevated membrane cholesterol can alter lipid raft composition, affecting receptor localisation and downstream signaling pathways, leading to an enhanced pro-inflammatory response. This state is characterised by increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and a reduction in phagocytic activity, impairing the clearance of cellular debris and exacerbating neurodegenerative processes. Furthermore, cholesterol-laden microglia exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidative stress, further promoting a neurotoxic environment. These findings underscore the importance of cholesterol homeostasis in microglial function and its role in the pathogenesis of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases [

8].

Phosphatidylcholine Deficiency and Membrane Integrity

Phosphatidylcholine (PC) is the most abundant phospholipid in mammalian membranes, essential for membrane fluidity and the function of embedded proteins. A deficiency of PC can arise from several sources relevant to ME:

- (i)

Impaired synthesis – for example, genetic variants or functional defects in enzymes like PEMT (phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase) could limit endogenous PC production. The PEMT enzyme uses S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) as a methyl donor to convert phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to PC. Therefore, genetic variants in enzymes involved in methyl group metabolism—such as MTHFR and BHMT, which are important for SAMe synthesis—may indirectly impair PC synthesis by limiting PEMT activity;

- (ii)

Excessive breakdown – chronic inflammation or allergic activation could elevate phospholipase A₂ (PLA₂) activity, which cleaves PC and releases arachidonic acid; and

- (iii)

Transport defects – the distribution of PC to peripheral tissues might be hampered by liver dysfunction or lipoprotein abnormalities.

Indeed, severe PC depletion has been linked to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) because PC is required to package triglycerides into very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) for export from the liver. Mice lacking PEMT (hence unable to synthesise adequate PC) accumulate fat in the liver and develop steatosis, illustrating how PC shortage can have system-wide metabolic effects [

9]. In ME, metabolomic analyses have found reduced plasma and membrane PC levels [

10].

Importantly, LCAT function depends on PC as its substrate; thus, PC deficiency and LCAT dysfunction are closely intertwined. If PC is low, even normal LCAT enzyme levels may fail to esterify cholesterol efficiently—effectively a functional LCAT impairment. The combination of low LCAT activity and low PC availability is deleterious, leading to rigid, cholesterol-rich cell membranes and a propensity for hemorheological and neural issues.

Arachidonic Acid, Eicosanoids and Immune Activation

Lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) is a key enzyme in reverse cholesterol transport, catalysing the esterification of free cholesterol using the sn-2 fatty acid from phosphatidylcholine (PC). This reaction yields cholesteryl esters for storage within HDL particles and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), which is typically reacylated back into PC via the Lands’ cycle. The sn-2 position of PC is frequently occupied by polyunsaturated fatty acids, most notably arachidonic acid (AA). Under physiological conditions, LCAT thus contributes to the regulated turnover of AA-containing phospholipids in plasma and supports the balance of lipid species that participate in membrane composition and inflammatory signaling.

When LCAT activity is reduced—due to genetic variants, metabolic dysfunction, or inflammation-induced suppression—this remodeling pathway is impaired. The consequence is a retention of AA-rich PC species in HDL particles, decreased formation of LPC, and reduced capacity to esterify and buffer free cholesterol. Another consequence is that less arachidonic acid containing PC is removed from cell membranes and transported back to the liver leading to a build-up of AA in peripheral tissue. In the setting of increased phospholipase A₂ (PLA₂) activity—triggered by mast cell activation, cellular stress, or viral inflammation—AA is actively released from membranes but not efficiently cleared or buffered, leading to excess free AA in both plasma and tissues.

Free AA serves as the substrate for two major enzymatic pathways: cyclooxygenases (COX-1/2), which generate prostaglandins and thromboxanes, and lipoxygenases such as 5-LOX (encoded by ALOX5), which produce leukotrienes and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids. Dysregulation in these pathways may be amplified by genetic variants that enhance enzyme activity or stability. For example, individuals carrying functional variants in ALOX5 or its activating protein (FLAP) may produce exaggerated amounts of leukotrienes from a given AA pool. LTB₄, LTC₄, and related metabolites exert potent effects on leukocyte recruitment, mast cell activation, vascular permeability, and bronchial tone—features commonly observed in ME subgroups with co-morbid mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS).

The prostaglandin arm of the pathway is similarly implicated. Chronic overproduction of PGE₂ and PGD₂, downstream of COX-2 activation, is associated with vasodilation, fever, pain sensitisation, and immune modulation. As these symptoms are common in fibromyalgia, patients who have both ME and fibromyalgia may have LCAT dysfunction with a propensity for increased PLA2 and COX-2 activation. PGE₂ has been shown to skew T cells toward a Th2 phenotype and induce enzymes such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), altering tryptophan metabolism and reducing serotonin synthesis. Furthermore, prostaglandins such as PGE₂ and PGD₂, and leukotrienes like LTB₄ and LTD₄, are capable of upregulating matrix metalloproteinases (e.g., MMP-1, MMP-9) in various tissues, which may contribute to connective tissue breakdown and joint hypermobility—a phenotype described in a subset of ME patients.

In sum, reduced LCAT activity may initiate a cascade of biochemical events that culminate in both the accumulation of free AA and its excessive incorporation into cell membranes. This AA-enriched lipid environment favours exaggerated eicosanoid signaling, with downstream effects on immune balance, pain perception, connective tissue integrity, and energy metabolism. This model also aligns with emerging findings in post-COVID syndrome, where SARS-CoV-2–induced PLA₂ activation may drive a persistent inflammatory and lipid remodeling response. In genetically susceptible individuals, the confluence of impaired AA clearance and hyperactive lipid mediator pathways may underlie the multisystem symptoms observed in ME and related conditions.

In addition to promoting pro-inflammatory eicosanoid production, an increased concentration of AA in membrane phospholipids—particularly in PC—may also accelerate the breakdown of PC itself. When PLA₂ enzymes are activated, they hydrolyze the sn-2 ester bond of membrane phospholipids, liberating free AA while simultaneously converting PC into LPC. This process not only fuels downstream inflammatory signaling but also represents a direct loss of structural membrane phospholipids. In individuals with compromised PC biosynthesis—such as those with genetic variants in the PEMT gene—this increased rate of PC turnover may outpace synthesis and recycling, leading to progressive membrane instability. Depletion of PC in cellular membranes can disrupt lipid raft architecture, impair receptor signaling (including insulin and adrenergic receptors), and hinder membrane-bound enzyme function. Moreover, insufficient PC availability can impair lipoprotein assembly and hepatic lipid export, further compounding lipid metabolic dysfunction. Thus, chronic or repeated activation of PLA₂ in an AA-enriched membrane context may represent a feed-forward mechanism that exacerbates both inflammation and membrane phospholipid depletion in susceptible individuals.

Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Activation and Hormone Imbalance

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) is a nuclear receptor and transcription factor with central roles in lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, inflammation resolution, and adipogenesis. It is activated by various endogenous ligands, including oxidized AA derivatives such as 15-deoxy-Δ¹²,¹⁴-prostaglandin J₂ (15d-PGJ₂), a high-affinity PPAR-γ agonist. Upon activation, PPAR-γ translocates to the nucleus and regulates gene expression programs that promote lipid storage, suppress NF-κB–driven inflammation, and enhance insulin responsiveness in adipose and other peripheral tissues.

In the context of this hypothesis, excess AA in peripheral tissues due to low LCAT activity or increased PLA₂ activation may increase levels of downstream eicosanoids such as PGD₂ and 15d-PGJ₂. In individuals with normal PPAR-γ signaling, this can trigger a compensatory anti-inflammatory response that limits damage from inflammatory cascades. PPAR-γ also promotes cholesterol efflux via upregulation of transporters such as ABCA1 and ABCG1, offering protection against LCAT dysfunction–induced membrane cholesterol accumulation. Therefore, individuals with intact PPAR-γ signaling may be partially buffered against both the inflammatory and metabolic consequences of excessive AA and cholesterol levels in cell membranes.

PPAR-γ also plays a role in regulating sex hormone metabolism. One of its downstream effects is suppression of CYP19A1 (aromatase), the enzyme that converts testosterone to estradiol. Increased PPAR-γ activity, driven by elevated 15d-PGJ₂, may therefore reduce estradiol levels and contribute to relative androgen excess. Low estradiol could contribute to symptoms such as vasomotor instability, mast cell activation, or dysregulated hypothalamic signaling. Estradiol can reduce 5α-reductase activity, the enzyme responsible for converting testosterone to the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Therefore, a drop in estradiol may disinhibit 5α-reductase, increasing DHT levels and exacerbating androgen-related symptoms such as hair loss, hirsutism, or hepatic insulin resistance.

Conversely, individuals with genetically reduced PPAR-γ activity—due to variants such as PPARG Pro12Ala—may be less responsive to AA-derived ligands. This results not only in diminished anti-inflammatory signaling, but also in weaker upregulation of cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1, increasing the risk of membrane cholesterol accumulation. In patients who also have LCAT dysfunction, the combined effect of impaired cholesterol esterification and impaired efflux may lead to particularly high levels of unesterified cholesterol in cell membranes. Elevated levels of transforming growth factor beta 2 (TGF-β2) may serve as a biomarker of reduced PPAR-γ activity, as PPAR-γ normally suppresses TGF-β signaling pathways involved in fibrosis, immune suppression, and extracellular matrix remodeling. As abnormalities in PPAR-γ and TGF-β2 have been found in people with autism, it’s possible that this may constitute a subtype of ME that might be more common in autistic ME patients.

Reduced activation of PPAR-γ may contribute to hepatic metabolic dysfunction by permitting unchecked pro-fibrotic signaling. PPAR-γ exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects in the liver, in part by repressing the expression of TGF-β2. When PPAR-γ activity is diminished, TGF-β2 expression increases, promoting SMAD-dependent transcriptional repression of CYP7A1, the rate-limiting enzyme in the classical bile acid synthesis pathway. This suppression of CYP7A1 reduces the hepatic conversion of cholesterol to bile acids, potentially impairing lipid digestion, altering enterohepatic signaling, and contributing to hepatic lipid accumulation. Thus, impaired PPAR-γ signaling may play a central role in disrupting bile acid homeostasis through TGF-β2–mediated transcriptional control.

Impaired PPAR-γ activation also leads to reduced suppression of CYP19A1, resulting in higher aromatase activity and increased conversion of testosterone to estradiol. Elevated estradiol levels can inhibit 5α-reductase, reducing the conversion of testosterone to the more potent androgen DHT. However, while estradiol typically increases sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), the presence of co-occurring insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia can suppress SHBG production, overriding the effect of high estradiol and increasing the bioavailability of free testosterone. In this setting, the combination of elevated ovarian androgen synthesis (driven by insulin), reduced SHBG binding, and impaired androgen clearance may result in sustained elevations in circulating testosterone. Because testosterone has a longer half-life, slower clearance, and broader systemic effects than DHT, this hormonal milieu could contribute to the development of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)[

15].

In summary, PPAR-γ serves as a critical regulatory node linking membrane lipid dynamics, inflammation, cholesterol transport, and sex hormone balance. Its variable activation—depending on genetic background and lipid mediator levels—may modulate distinct symptom patterns in ME by shaping the balance between estrogen and androgens, influencing cholesterol efflux capacity, and buffering or amplifying inflammation in response to elevated AA.

Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Inhibition

Increased cholesterol content in the plasma membrane can also directly impair mitochondrial energy metabolism by contributing to the inhibition of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex. Excess membrane cholesterol alters the fluidity and function of mitochondrial-associated membranes and may increase oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling. These stress signals, including activation of NF-κB and FOXO1, can upregulate pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK), which inactivates PDH by phosphorylation. The result is a block in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, causing pyruvate accumulation and forcing cells to rely on anaerobic glycolysis. Thus, cholesterol accumulation contributes not only to membrane dysfunction and insulin resistance but also to a metabolic shift that limits efficient ATP production.

Moreover, the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α (encoded by PPARGC1A), which partners with PPAR-γ to regulate mitochondrial and metabolic gene expression, also influences cholesterol homeostasis. PGC-1α promotes the expression of LXR target genes such as ABCA1 and ABCG1, thereby supporting cholesterol efflux. Individuals carrying genetic variants such as PPARGC1A rs8192678 (Gly482Ser) may have reduced coactivation potential, further impairing ABCA1/ABCG1 expression. When combined with LCAT dysfunction, this may lead to particularly severe membrane cholesterol accumulation. Additionally, reduced PGC-1α expression may increase PDK4 expression and contribute to PDH inhibition, especially under conditions of metabolic stress or inflammation. Therefore, individuals with PPARGC1A variants may be more vulnerable to developing a profound block in pyruvate oxidation and mitochondrial energy production, compounding the effects of PPAR-γ or LCAT dysfunction.

Another potential mechanism contributing to PDH complex inhibition involves the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta (PPARβ/δ) by arachidonic acid–derived eicosanoids. PPARβ/δ is a nuclear receptor that promotes fatty acid oxidation and represses glucose oxidation by upregulating PDK4. Several oxidized lipid mediators, including prostacyclin (PGI₂) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids such as 15-HETE and 13-HODE, can serve as endogenous ligands for PPARβ/δ. In patients with elevated arachidonic acid levels and enhanced eicosanoid biosynthesis—such as those carrying high-expression variants in genes like ALOX5—this pathway may be chronically activated. The resulting increase in PDK4 expression could lead to sustained inhibition of PDH, reinforcing a metabolic shift away from glucose oxidation and exacerbating the energy deficit already present in ME. This adds a further layer of complexity in individuals who also exhibit impaired PPARγ/PGC-1α signaling, as the combination of suppressed mitochondrial biogenesis, reduced PDH activity, and excess PPARβ/δ-driven PDK4 expression may trap cells in a hypometabolic state. This fits with research in ME patients which shows increased PDKs and inhibited PDH [

16].

Histamine Exacerbation of Dysregulation

Histamine, another key mediator released by mast cells, serves as a potent amplifier of this AA-driven inflammatory cascade. Acting through H1 and H4 receptors, histamine increases intracellular calcium levels and directly stimulates PLA₂ activity, thereby promoting further AA liberation from membrane stores. Additionally, histamine enhances COX-2 and 5-LOX expression, boosting the synthesis of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes. These eicosanoids in turn sensitise tissues to histamine and promote mast cell activation, forming a self-reinforcing inflammatory loop. Both histamine and eicosanoids, particularly LTB₄ and PGE₂, are known to upregulate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) such as MMP-1 and MMP-9, which degrade collagen and other extracellular matrix components. This may contribute to the development of endometriosis and hypermobility— disorders which frequently co-occur with ME.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterised by ectopic endometrial tissue, cyclic pain, and immune dysregulation. In endometriosis, both histamine and prostaglandins are elevated in peritoneal fluid and promote angiogenesis, neuroinflammation, and nociceptor sensitisation. Moreover, MMPs are overexpressed in ectopic endometrial lesions, contributing to tissue invasion and lesion expansion. These effects may be exacerbated by AA-enriched membranes resulting from impaired lipid remodeling, and insufficient PPAR-γ activity to resolve inflammation.

Activation of PPAR-γ promotes transcriptional programmes that suppress NF-κB signaling, downregulate COX-2 and ALOX5 expression, and inhibit mast cell degranulation. PPAR-γ also suppresses the expression of MMPs and shifts macrophages and T cells toward regulatory or anti-inflammatory phenotypes. However, in the context of LCAT deficiency and chronic inflammation, this protective mechanism may be insufficient. Reduced activation of PPAR-γ due to skewed AA metabolism, PC deficiency or PPAR-γ genetic variants, may lead to impaired resolution of inflammation. It has been suggested that there is a higher occurrence of both PCOS and endometriosis in female ME patients [

15].

Neuronal vs. Non-Neuronal Insulin Sensitivity

Differential membrane lipid composition arising from LCAT dysfunction and variations in PC synthesis may underlie divergent patterns of insulin receptor sensitivity in ME subtypes. In individuals with both LCAT dysfunction and reduced PC availability, insulin sensitivity could be systemically elevated. Phosphatidylcholine plays a critical role in the structural organisation and curvature of the plasma membrane, and its deficiency has been shown to impair clathrin-mediated endocytosis, a key process in insulin receptor internalisation and recycling. As a result, insulin receptors accumulate on the cell surface, prolonging their activation and amplifying downstream signaling. This effect is likely to occur across multiple tissue types, including noradrenergic neurons, which are known to express insulin receptors and exhibit insulin-sensitive regulation of norepinephrine transporter (NET) expression. Enhanced insulin signaling in this context may downregulate NET, increasing extracellular norepinephrine levels and contributing to the increased sympathetic nervous system activation observed in some ME patients.

In contrast, a second ME subtype, characterised by LCAT dysfunction with preserved PC synthesis, may experience a different trajectory. In these individuals, the activity of LCAT leads to a build up of AA in peripheral tissues, resulting in a progressive enrichment of AA within membrane PC. This shift in lipid composition can increase membrane fluidity, disrupting lipid raft integrity and impairing insulin receptor signaling. In neurons, this may blunt insulin responsiveness and lead to elevated NET expression and reduced extracellular norepinephrine availability. Although neurons do not take up circulating cholesterol, and thus are relatively insulated from plasma cholesterol dysregulation, peripheral tissues are not. In these tissues, membrane AA enrichment combined with free cholesterol accumulation—secondary to LCAT dysfunction—may act synergistically to destabilise membrane microdomains and further impair insulin receptor localisation and function. Cholesterol-rich, AA-dense membranes are known to interfere with insulin receptor signaling platforms, potentially leading to systemic insulin resistance.

Together, these opposing effects—insulin hypersensitivity in the PC-deficient subtype and insulin resistance in the normal PC subtype—highlight the critical role of membrane lipid composition in shaping tissue-specific insulin responses. Importantly, the differential effects in noradrenergic neurons may drive distinct patterns of norepinephrine dysregulation, which in turn influence autonomic tone, energy metabolism, and neuroimmune signaling in ME.

Insulin’s Role in Regulating Norepinephrine Transporters

The norepinephrine transporter (NET) is a critical membrane protein that clears norepinephrine (NE) from the synaptic cleft and extracellular space, thereby regulating the intensity and duration of noradrenergic signaling. NET function shapes sympathetic tone across both the central and peripheral nervous systems. Notably, insulin signaling has been shown to modulate NET expression and activity. Experimental studies indicate that insulin, acting through the PI3K/Akt pathway, reduces NET trafficking to the cell surface and promotes its internalisation, thereby decreasing NE reuptake. In neuronal cultures, insulin application leads to reduced NE uptake, with Akt kinase identified as a key mediator of this effect [

17].

In the context of ME, patients with membrane hypersensitivity to insulin—particularly those with LCAT dysfunction and PC deficiency—may experience excessive downregulation of NET in noradrenergic neurons. Even modest elevations in insulin, such as those seen with postprandial surges, could substantially reduce NET surface expression. This would result in elevated extracellular NE levels, consistent with the hyperadrenergic symptoms reported in some ME patients, including tachycardia, palpitations and anxiety. Studies have indeed identified ME subgroups with high and low plasma NE levels [

18].

Reduced NET function may also impair NE recycling. Norepinephrine that is not reabsorbed cannot be repackaged into synaptic vesicles, leading to depletion of intracellular stores. This is reflected in decreased levels of the NE metabolite dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG), as observed in an NIH intramural study of ME patients [

19]. Such a pattern could create a paradoxical state of simultaneous adrenergic excess (increased receptor stimulation) and sympathetic insufficiency (limited NE reserves), contributing to autonomic instability.

Moreover, sustained elevations of extracellular NE may activate α₂-adrenergic autoreceptors on pre-synaptic noradrenergic neurons, suppressing the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)—the rate-limiting enzyme in NE synthesis—via negative feedback inhibition. This suppression becomes particularly problematic in the context of NET downregulation, as less NE is recycled, increasing reliance on de novo synthesis. If NE synthesis is also impaired—whether due to genetic variants in TH, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), or tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) pathways, or due to deficiencies in necessary cofactors such as vitamin B6, iron, copper, or vitamin C—the result may be a fragile system prone to episodic depletion. This could manifest as a “boom and bust” cycle of extracellular NE availability, where transient surges are followed by profound depletion. Such a mechanism may underlie the hallmark symptom of ME: post-exertional malaise (PEM). The fact that PEM can be triggered by both mental and physical exertion is consistent with this model, as both cognitive and physical activity would demand increased noradrenergic output, potentially exhausting an already compromised system.

β₂-Adrenergic Receptor & Overtraining Syndrome

Prolonged elevations in extracellular NE can also lead to β₂-adrenergic receptor (β₂-AR) downregulation on peripheral target cells. β₂-ARs mediate critical physiological responses including vasodilation, bronchodilation, immune modulation, gastrointestinal motility, and metabolic regulation. Notably, research has shown reduced responsiveness of β₂-ARs in ME immune cells (to β₂-AR agonists), reinforcing this mechanism as a clinically relevant aspect of the disease [

20].

This receptor downregulation may also play a role in chronotropic incompetence (CI)—the inability to appropriately increase heart rate during exertion—frequently observed in ME [

21,

22]. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) over two consecutive days has shown that ME patients experience reduced performance on the second day, along with increased CI [

23]. This may reflect the consequence of excessive β-adrenergic stimulation during day one exercise leading to β-receptor desensitisation by day two. Alternatively, the exertion may deplete NE stores, contributing to autonomic insufficiency during the second test.

Interestingly, many ME patients report being highly active or athletic prior to disease onset, and there is considerable symptomatic overlap between ME and overtraining syndrome (OTS). In OTS, chronic physical stress leads to downregulation of β₂-ARs, impaired sympathetic function, and persistent fatigue. These parallels suggest that overactivation of the adrenergic system—whether via physical overexertion or metabolic dysregulation—may represent a common pathophysiological thread in both conditions.

It is important to note, however, that not all individuals with ME will exhibit β₂-AR downregulation in response to sustained elevations of NE. The degree of receptor desensitisation may be modulated by genetic polymorphisms in the

ADRB2 gene, which encodes the β₂-AR. Specific variants, such as

Arg16Gly (rs1042713) and

Gln27Glu (rs1042714), have been shown to influence receptor internalisation and desensitisation kinetics in response to catecholamine exposure. For instance, the

Gly16 allele has been associated with enhanced agonist-induced downregulation, whereas the

Glu27 variant appears to confer relative resistance to receptor internalisation. Such genetic differences may underlie inter-individual variability in autonomic responsiveness and vulnerability to β₂-AR-mediated dysfunction in ME. Gene variants in the

CACNA1C gene which codes the Cav1.2 channel may also affect β₂-AR desensitisation mechanisms and may confer a vulnerability to β₂-AR downregulation [

24].

Noradrenergic Neuronal Insulin Resistance and Increased Norepinephrine Uptake

In contrast to the insulin-hypersensitive subtype of ME, another pathophysiological route may involve insulin resistance within noradrenergic neurons. This may occur in patients with LCAT dysfunction and preserved PC synthesis, where elevated AA content in neuronal membranes alters fluidity and disrupts insulin receptor signaling. Neurons are not likely to be affected by high plasma cholesterol, but high AA enrichment can impair membrane raft formation and insulin receptor localisation, diminishing insulin signal transduction.

Insulin signaling is known to downregulate NET expression via the PI3K/Akt pathway. In insulin-resistant noradrenergic neurons, this regulatory mechanism is blunted, leading to increased NET surface expression and enhanced NE uptake from the synaptic cleft. This dynamic is further exacerbated by genetic variants that impair NE synthesis (e.g., TH, DBH, or GCH1 affecting BH4 availability. In particular, polymorphisms in SLC18A2, which encodes the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2), may impair the sequestration of NE into synaptic vesicles, leaving more NE exposed to cytosolic degradation by monoamine oxidase (MAO). This increases the metabolic burden on the neuron and may deplete intracellular NE reserves over time, despite an apparently robust reuptake process. The result may be a functional noradrenergic deficit with low synaptic NE availability between bursts of vesicular release.

Insulin Signaling and Dopamine Transporter Regulation in the Striatum

In addition to its role in noradrenergic neurons, insulin also modulates dopaminergic signaling in the striatum—a region central to reward processing, motivation, and motor control. Dopamine neurons in the striatum express insulin receptors, and insulin signaling has been shown to increase dopamine transporter (DAT) expression and trafficking to the neuronal membrane. This leads to enhanced reuptake of dopamine from the synaptic cleft and reduced extracellular dopamine availability. In contrast to norepinephrine regulation, where insulin increases extracellular NE by downregulating NET, insulin increases dopamine clearance by upregulating DAT [

25].

This distinction has implications for ME subtypes characterised by divergent neuronal insulin sensitivity. In the insulin-hypersensitive subtype—associated with PC deficiency and neuronal insulin hypersensitivity—exaggerated insulin signaling in striatal neurons may lead to excessive DAT expression, resulting in abnormally low extracellular dopamine levels. Clinically, this may manifest as reduced motivation, anhedonia, motor slowing, or emotional flattening.

Conversely, in the insulin-resistant neuronal subtype—associated with high membrane arachidonic acid content—DAT expression may be blunted, leading to increased extracellular dopamine. Depending on individual receptor sensitivity and genetic background, this could either result in a hyperdopaminergic state (e.g., impulsivity, agitation) or, over time, contribute to postsynaptic receptor desensitisation and dopaminergic dysfunction.

Noradrenergic Subtypes of ME (Low vs. High Norepinephrine)

We have described the possibility of three types of noradrenergic dysfunction and how they might arise. Let’s now consider the effects of these three subtypes on noradrenergic function in the brain and sympathetic nervous system, and the symptoms that might arise from this dysregulation.

Subtype 1: Low Norepinephrine (Hypoadrenergic)

This subtype is defined by reduced extracellular NE levels, which may result from increased reuptake, impaired synthesis, and/or reduced recycling of NE. Clinically, patients may experience symptoms consistent with low sympathetic nervous system tone: orthostatic intolerance, cold extremities, reduced thermoregulation, and frequent dizziness or light-headedness upon standing. Cerebral hypoperfusion due to inadequate vasoconstriction may contribute to brain fog, headaches, and visual disturbances. In the brain, low norepinephrine can impair prefrontal cortex function and the activity of the locus coeruleus, leading to reduced attention, motivation, and mental stamina. It may also disrupt astrocyte-mediated support for neurons, limiting glucose uptake, lactate production, and glutamate clearance—contributing to excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, and cognitive fatigue. Sleep may be unrefreshing due to poor glymphatic clearance during sleep cycles, which is normally facilitated by noradrenergic tone.

In the periphery, low NE reduces lipolysis, hepatic glucose output, and vascular tone, potentially contributing to energy crashes and poor exercise tolerance. Paradoxically, if low NE is a result of neuronal and systemic insulin resistance, then the low liver glucose production caused by low sympathetic activation may be offset by the systemic insulin resistance. The low liver glucose output may lead to a masking of the systemic insulin resistance, as it could lead to insulin and glucose levels remaining within normal levels.

Gastrointestinal motility may also be affected, with symptoms such as bloating, constipation, or alternating bowel habits.

As a compensatory response to low NE levels, in order to maintain blood pressure slower hormonal systems such as the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and vasopressin may become upregulated, which may manifest as salt craving, increased thirst, and episodes of fluid retention or dehydration. However, these systems are not always sufficient to maintain stable blood pressure or adequate perfusion, particularly in the context of physical or cognitive exertion.

In the context of low NE, the immunoregulatory role of adrenergic signaling may be significantly diminished. Norepinephrine acts via β₂-AR on immune cells to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production and promote regulatory phenotypes, including the polarisation of macrophages toward an M2-like anti-inflammatory state. Reduced NE availability may therefore impair this immunosuppressive tone, leading to a relative shift toward Th1- and Th17-type immune responses, increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, and reduced induction of regulatory T cells. Inadequate β₂-AR-mediated signaling may also disrupt microglial homeostasis in the central nervous system, contributing to a pro-inflammatory neuroimmune environment. This lack of adrenergic restraint may facilitate low-grade systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation, further amplifying fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and hypersensitivity in this ME subtype.

Subtype 2: High Norepinephrine (Hyperadrenergic)

This subtype is characterised by elevated extracellular NE levels due to reduced NET expression and preserved NE synthesis. Clinically, patients often experience symptoms of sustained sympathetic overactivation, such as resting tachycardia, palpitations, anxiety, and exercise intolerance. Orthostatic stress may trigger exaggerated heart rate responses (e.g., postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or POTS), even in the absence of hypotension. Vasodilation mediated by β₂-ARs can contribute to blood pooling in the periphery, leading to light-headedness and cognitive dysfunction despite elevated circulating NE.

In the central nervous system, chronically elevated NE may contribute to symptoms such as insomnia, hypervigilance, irritability, and sensory hypersensitivity by modulating excitatory–inhibitory balance and arousal circuits. Norepinephrine acts through adrenergic receptors on both neurons and astrocytes to influence neurotransmitter dynamics, including glutamate and GABA signaling. While acute NE signaling can enhance glutamate clearance by upregulating astrocytic excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs), prolonged or dysregulated adrenergic activation may lead to altered synaptic plasticity and impaired GABAergic inhibition.

In particular, excessive β-adrenergic signaling has been shown to reduce GABA synthesis and release in some brain regions, diminishing inhibitory tone and contributing to cortical hyperexcitability. This imbalance between excitation and inhibition may underlie key symptoms observed in ME, including sensory hypersensitivity, cognitive overload, and non-restorative sleep, without necessarily invoking classic glutamate excitotoxicity. Moreover, regional differences in NE signaling and receptor expression likely contribute to heterogeneous effects across different neural circuits. In addition, astrocytic dysfunction in response to high NE levels may reduce lactate shuttling to neurons and impair the glymphatic system’s ability to clear metabolic waste during sleep—contributing to unrefreshing sleep, neuroinflammation, and impaired cognitive function.

In the periphery, sympathetic overdrive can suppress digestive motility, leading to nausea, delayed gastric emptying, or constipation. Hepatic glucose production is often elevated, potentially contributing to glucose instability. Some patients may also experience symptoms of excessive sweating, shakiness, or heat intolerance during stress or exertion.

The severity of symptoms in this subtype may be influenced by the individual’s capacity to counterbalance sympathetic activity via the parasympathetic nervous system. Patients with co-occurring impairments in acetylcholine synthesis or vagal tone may have difficulty dampening adrenergic responses, leading to prolonged recovery from physical or emotional stressors. In these individuals, even minor stimuli can trigger sustained autonomic arousal, contributing to cycles of overexertion and delayed symptom flare-ups.

Elevated NE levels can significantly alter peripheral energy metabolism by acting on β-adrenergic receptors in both skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. In adipocytes, NE stimulates β₃-adrenergic receptors to activate hormone-sensitive lipase and promote lipolysis, increasing circulating free fatty acids. While this may provide an acute energy source, sustained lipolysis under hyperadrenergic conditions can lead to lipid overload, insulin resistance, and altered mitochondrial function. In skeletal muscle, high NE increases β₂-AR signaling, which promotes glycogenolysis and, under stress or exertion, accelerates muscle protein breakdown to support gluconeogenesis. Chronically elevated sympathetic tone may therefore contribute to muscle catabolism, reduced muscle endurance, and impaired recovery following exertion—features commonly reported in ME.

In patients with elevated extracellular NE and preserved β₂-AR function, the immune response may skew toward suppression or dysregulation depending on the receptor density and downstream signaling dynamics. Chronic β₂-AR stimulation of immune cells, particularly T cells and macrophages, can induce a tolerogenic or immunosuppressive phenotype, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production and inhibiting effective antiviral responses. In this setting, persistent sympathetic overactivation may paradoxically impair host defense, increase susceptibility to viral reactivation, and promote Th2 polarisation. Moreover, sustained β₂-AR signaling can suppress natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity and antigen-presenting cell function, potentially contributing to immune evasion and chronic infection.

Subtype 3: High Norepinephrine with β₂-Adrenergic Receptor Downregulation

In this subtype, extracellular NE is elevated— due to reduced NET expression—but β₂-adrenergic receptor signaling is diminished. This may result from genetic variants that increase the susceptibility of β₂-ARs to downregulation in response to sustained high NE exposure. This creates an imbalance in adrenergic signaling, favouring α₁- and β₁-mediated responses while impairing the vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic roles of β₂-receptors. The result is a state of unopposed vasoconstriction and heightened vascular tone, leading to symptoms such as cold extremities, Raynaud-like episodes, reduced peripheral perfusion, and exercise intolerance.

The metabolic consequences of this receptor imbalance are particularly evident in the liver. While α₁- and β₁-adrenergic stimulation enhance glycogenolysis, the loss of β₂-receptor input impairs gluconeogenesis—a pathway essential for maintaining glucose homeostasis during prolonged activity or fasting. This can result in reduced hepatic lactate clearance and could contribute to post-exertional malaise, particularly during aerobic activity when gluconeogenic support is critical. This subtype may be particularly vulnerable to low glucose levels and postprandial hypoglycemia. This is because the systemic insulin hypersensitivity that causes the increased NET expression would lead to fast systemic glucose uptake and yet there would be an inability to increase liver gluconeogenesis to maintain glucose levels. This may be more likely to occur after a period of exertion, as glycogen levels would be depleted.

In skeletal muscle, impaired blood flow and disrupted adrenergic signaling may limit energy availability and exacerbate fatigue. Pulmonary symptoms may also arise in this subtype. β₂-receptors mediate bronchodilation, and their downregulation may increase the risk of bronchoconstriction, restricted breathing, and exertional dyspnea. In the gastrointestinal tract, reduced β₂ signaling diminishes motility, potentially contributing to symptoms such as constipation, bloating, or gastroparesis.

In the central nervous system, β₂-receptors normally support anti-inflammatory signaling, glymphatic clearance, and astrocytic lactate production. Their dysfunction may lead to neuroinflammation, impaired metabolic waste clearance during sleep, and inadequate neuronal energy supply—manifesting as cognitive fatigue, poor sleep quality, and heightened sensitivity to stressors.

On the immune front, β₂-ARs on T cells, macrophages, and microglia modulate cytokine production and limit excessive immune activation. Their downregulation may increase susceptibility to mast cell activation, autoimmune reactions, and chronic low-grade inflammation.

Collectively, this subtype represents a maladaptive adrenergic profile in which high NE levels are not appropriately buffered by β₂-AR signaling, leading to a constellation of vascular, metabolic, pulmonary, and neuroimmune disturbances.

It is important to note that these subtypes may overlap or patients may transition between them over time. For instance, a patient could start as hyperadrenergic (Subtype 2) and then transition into a β₂-receptor-downregulated state (Subtype 3) after months or years of illness. Alternatively, if a patient with PC deficiency started taking supplements that improve PC levels, they could shift to Subtype 1. Recognising these subtypes has practical implications: treatments like beta-blockers, or salt/fluid loading might help one subtype but be counterproductive in another.

Acetylcholine Synthesis

It is important to acknowledge the potential role of acetylcholine (ACh) in modulating these subtypes. The balance between sympathetic (NE-driven) and parasympathetic (ACh-driven) activity is crucial. Genetic differences in cholinergic function – for example, polymorphisms in the choline acetyltransferase gene (CHAT) or autoantibodies to muscarinic receptors – might exacerbate autonomic imbalances. A patient with a hyperadrenergic profile and a weak parasympathetic brake (due to low ACh or poor vagal tone) could have more severe tachycardia and GI dysmotility. Such interactions may help explain why some ME patients benefit from treatments targeting the cholinergic system (like pyridostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor used in POTS to increase ACh). While ACh genes are not the primary focus of this hypothesis, they are an important modifier of the NE subtypes described.

Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System (RAAS) and Vasopressin

Although reduced NE levels in the sympathetic nervous system would typically lower vascular tone and blood pressure, compensatory neuroendocrine mechanisms may partially mask this deficit in many ME patients. When NE is low, reduced vascular resistance and cardiac output can trigger baroreceptor-mediated activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and hypothalamic release of vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone, ADH). Elevated angiotensin II promotes systemic vasoconstriction and sodium retention, while vasopressin increases water reabsorption and contributes to vascular tone through V1 receptor signaling. These compensatory pathways may maintain blood pressure within the normal range, even in the presence of autonomic hypofunction, potentially obscuring low NE as a contributing factor. However, this regulatory adaptation comes at a cost: increased vasopressin and RAAS activity can drive symptoms such as salt craving, thirst, and increased urination, which are commonly reported by some ME patients.

Importantly, this compensatory response may be less effective in individuals with concurrent hormonal dysregulation. In patients with increased PPAR-γ activation—driven by elevated AA derivatives such as 15d-PGJ₂—suppression of CYP19A1 may reduce estradiol levels. Low estrogen has been shown to diminish vascular responsiveness to vasopressin by downregulating V1 receptor expression and reducing vascular smooth muscle sensitivity. Therefore, ME patients with both low NE and reduced estrogen levels may be more susceptible to orthostatic hypotension and low blood pressure, despite maximal compensatory activation of vasopressin and RAAS. This hormonal-vascular interaction may help explain the variability in blood pressure regulation and orthostatic intolerance across ME subtypes.

Glymphatic Clearance and Unrefreshing Sleep

The glymphatic system is the brain’s waste clearance pathway, where cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) interchanges with interstitial fluid to remove metabolites (like amyloid) especially during sleep. Noradrenergic tone plays a pivotal role in this system. During deep non-REM sleep, locus coeruleus firing (source of central NE) greatly diminishes, which allows expansion of interstitial space and efficient CSF influx for waste removal. If a person has chronically low or elevated NE (and particularly if they have trouble achieving deep sleep, as many ME patients do), glymphatic clearance may be impaired. Recent studies have shown that even subtle NE oscillations are critical for driving the contractions of blood vessels that facilitate glymphatic flow. In ME, dysregulated NE levels could leave the brain in a more “wake-like” state, reducing waste removal. Over time, accumulation of neurotoxic metabolites could contribute to cognitive impairments and headaches. Thus, the goal should be restoring normal circadian NE patterns. The frequent report of unrefreshing sleep in ME might be directly related to this glymphatic issue – patients may not have the correct NE oscillations needed for correct glymphatic system function, resulting in them waking up feeling as tired as before sleep.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications

If this hypothesis is accurate, it suggests a precision medicine approach to ME: identifying the dominant pathophysiological subtype in each patient and tailoring therapy accordingly. Key diagnostic strategies and biomarkers to consider include:

Lipid Metabolism Markers: Testing for LCAT functionality could involve measuring the ratio of esterified to free cholesterol in plasma or a direct LCAT activity assay. A low cholesterol esterification percentage with normal cholesterol levels might indicate LCAT impairment. Additionally, assessing HDL particle numbers and sizes (via NMR or electrophoresis) could reveal if HDL is low or dysfunctional. For phosphatidylcholine, one could measure PC and phosphatidylethanolamine in red blood cell membranes (e.g., through lipidomics). A low PC:PE ratio in cell membranes would support the PC deficiency aspect. Low plasmalogen levels may also indirectly suggest phospholipid metabolic issues. High plasma arachidonic acid or a high omega-6:omega-3 ratio would be another red flag; this can be measured in blood fatty acid profiles. In a research setting, one might even check for genetic variants in PEMT, MTHFR, or ALOX5 that could contribute to the lipid profile.

Catecholamine and Autonomic Testing: Patients can be stratified by autonomic subtypes using tests like standing plasma norepinephrine levels (to detect hyperadrenergic POTS, defined by NE > 600 pg/mL when upright), heart rate and blood pressure response to tilt-table testing, and quantitative sudomotor or pupillary response tests (which can reveal sympathetic nerve activity). Low DHPG (a NE metabolite) in the presence of high NE would support the NET dysfunction idea.

PPAR-γ and Inflammatory Profiling: In patients suspected to have reduced PPAR-γ activity, genetic testing for common polymorphisms such as PPARG Pro12Ala may provide initial support. Given PPAR-γ’s regulatory role in lipid metabolism, immune modulation, and hormonal balance, indirect biomarkers may offer further diagnostic value. For example, elevated transforming growth factor beta 2 (TGF-β2) may serve as a surrogate indicator of reduced PPAR-γ signaling, as PPAR-γ normally suppresses TGF-β transcription. Additionally, hormonal profiles showing elevated estradiol may reflect increased activity of the enzyme CYP19A1, which is normally inhibited by PPAR-γ. Together, the combination of elevated TGF-β2 and high estradiol may help identify a PPAR-γ–deficient ME subtype. One could also measure adiponectin (a hormone increased by PPAR-γ activation) – low adiponectin might indicate PPAR-γ is not active.

Mast Cell and Eicosanoid Markers: For patients suspected of mast cell/eicosanoid involvement, one can test serum or urine histamine, prostaglandin D2, and leukotriene E4. Elevations in these would confirm active mast cell/eicosanoid pathways. High arachidonic acid plus high leukotriene E4 in urine, for instance, would strongly point to the AA-leukotriene axis being upregulated. Those patients might benefit most from leukotriene inhibitors.

Given these diagnostic insights, we can outline therapeutic strategies aimed at the different components of the hypothesis:

Phosphatidylcholine Restoration: If PC deficiency is identified, a logical step is to replenish PC. PC supplements that are made from sunflower oil may be preferable as they are likely to contain less AA. Another approach is to provide choline (as alpha-GPC or citicoline) to drive endogenous PC synthesis; however, in those with PEMT issues, that might not be sufficient. By restoring PC, we not only repair membranes but also give LCAT its substrate back – potentially improving HDL function and cholesterol clearance. However, increasing PC levels may increase membrane AA levels.

LCAT Augmentation: Currently, recombinant human LCAT therapy is an experimental treatment mainly for familial LCAT deficiency. A recombinant LCAT (called rhLCAT or ACP-501) has been shown to raise HDL cholesterol and enhance reverse cholesterol transport in animal models. If our hypothesis is correct, one could envision using rhLCAT in a subset of ME patients with proven LCAT dysfunction, to help clear excess cholesterol and reduce immune activation.

Targeting Arachidonic Acid Pathways: For those with signs of AA/eicosanoid excess (e.g., high prostaglandins, pain, MCAS), omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (fish oil) is a foundational approach. Omega-3 (EPA/DHA) competes with AA in cell membranes and can reduce the substrate available for inflammatory eicosanoids, while also yielding anti-inflammatory resolvins. Dietarily, reducing omega-6 intake (from vegetable oils, etc.) and increasing omega-3 could shift the balance.

COX-2 Inhibitors (like celecoxib or even over-the-counter NSAIDs if tolerated) can cut down prostaglandin production and may alleviate symptoms like joint/muscle pain and headaches. More specifically, leukotriene inhibitors could be game-changing for a subset: the leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast (commonly used for asthma) might help not only asthma-like symptoms but also brain inflammation. Another option is a 5-LOX inhibitor, which would directly reduce leukotriene synthesis – this could benefit those with MCAS and severe inflammatory pain.

PPAR-γ Agonism: If an ME patient has evidence of the PPAR-γ impaired profile (high inflammation, insulin resistance, perhaps PCOS), a PPAR-γ agonist could address multiple problems at once. The thiazolidinedione drugs pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are potent PPAR-γ activators used in diabetes. An alternative is using nutraceutical PPAR-γ agonists: compounds like resveratrol and omega-3 EPA have mild PPAR-γ activating properties. Another intriguing candidate is NRF2 activators (like sulforaphane) because NRF2 and PPAR-γ pathways intersect in controlling inflammation and metabolism. It is not clear if these treatments would be effective if the patient has genetic variants of PPAR-γ.

Targeting PDH Inhibition and Restoring Metabolic Flexibility: In individuals with impaired PDH activity—potentially driven by PPAR-β/δ–mediated upregulation of PDK4, reduced PGC-1α expression, or cholesterol-induced mitochondrial dysfunction—therapeutic strategies should aim to reactivate PDH while supporting mitochondrial function and improving membrane lipid balance. Sodium dichloroacetate (DCA) is a direct inhibitor of PDK enzymes and can restore PDH activity by preventing phosphorylation-dependent inactivation. Cofactor support with thiamine (vitamin B1), alpha-lipoic acid, magnesium, and NAD+ precursors (e.g., nicotinamide riboside or niacin) may further enhance PDH complex function. PPAR-γ agonists such as pioglitazone could offer additional benefit by improving insulin sensitivity, suppressing inflammatory signaling, and indirectly modulating PDK expression, although they do not directly counter PPAR-β/δ activity. In cases where PPAR-β/δ activation is driven by high arachidonic acid or eicosanoid load, dietary reduction of omega-6 fats, PLA2 inhibition, or supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids (EPA/DHA) may reduce the stimulus for PDK4 upregulation. Where PGC-1α function is compromised—e.g., due to PPARGC1A rs8192678 variants—AMPK activators such as AICAR, metformin, or mild exercise mimetics may be considered to enhance mitochondrial gene expression. Finally, phosphatidylcholine or plasmalogen supplementation may improve membrane fluidity and reduce cholesterol-induced mitochondrial stress, helping to restore a metabolic environment more favorable for glucose oxidation.

For the Hypoadrenergic Subtype: the goal is to increase sympathetic tone or compensate for it. One potential medication that could help is midodrine, an alpha-1 agonist that raises standing blood pressure and can reduce orthostatic symptoms. Fludrocortisone, a mineralocorticoid, helps kidneys retain salt and water to expand blood volume (useful if aldosterone is low). Low-dose psychostimulants (like methylphenidate or modafinil) have been used off-label in ME to combat fatigue and might particularly help those with low central NE by promoting release of monoamines. Care must be taken not to overshoot and cause anxiety or insomnia.

For the Hyperadrenergic Subtype: here the aim is to blunt the excessive NE effects. Beta-blockers (such as propranolol, bisoprolol or even low-dose atenolol) can be very helpful in POTS/hyperadrenergic patients to reduce heart rate; patients often report they feel more calm and can stand longer with a beta blocker. Ivabradine, which lowers heart rate by a different mechanism, is another POTS treatment that could be used if beta blockers are not tolerated. Clonidine or guanfacine (central α2 agonists) can reduce central sympathetic output. Correction of underlying PC deficiency to correct NET regulation would be the ideal treatment.

For the Desensitised β2 Receptor Subtype: This is a more difficult to treat subtype– simply blocking NE might not help because receptors are already unresponsive, and increasing NE (with a drug like midodrine) might not work either because the receptors aren’t listening well. The ideal treatment is to correct the underlying dysfunction of NETs to lower extracellular norepinephrine levels. If low NET expression is due to PC deficiency, then supplementing PC should help correct extracellular NE levels. However, β2 receptors can take months to upregulate their surface expression back to normal, meaning that PC supplementation may have to be maintained for at least 3 months to achieve symptom improvement.

Mast Cell Stabilisation and Antihistamines: Regardless of subtype, if mast cell activation is part of the picture (histamine symptoms, etc.), treatments to stabilise mast cells or block their mediators can dramatically improve quality of life. This includes H1 antihistamines (such as cetirizine, fexofenadine) and H2 blockers (famotidine) in combination, cromolyn sodium (oral or nebulized) to stabilise gut and lung mast cells, and supplements like quercetin which is a natural mast cell stabiliser. Ketotifen, a prescription H1 blocker that also stabilises mast cells, is sometimes used in severe cases. Reducing mast cell activation can also indirectly preserve PC levels (by reducing PLA2 activation) and improve sleep in ME patients. Some patients follow a low-histamine diet to minimise triggers.

Hormonal Therapies: If a patient has clear hormone abnormalities like PCOS or thyroid dysfunction, standard treatments for those should be incorporated. For PCOS, beyond metformin and pioglitazone (addressing insulin resistance), ensuring adequate estrogen/progesterone balance via oral contraceptives or cyclic progesterone might help energy and mood. Spironolactone, which is used in PCOS for its anti-androgen and aldosterone-blocking effects, could also be beneficial in ME patients with PPAR-γ dysfunction by reducing aldosterone’s pro-inflammatory effects and helping with potassium retention.

Of course, any interventions should be introduced carefully and one at a time to gauge benefit, as ME patients are often sensitive to medications. It will also be important to monitor objective outcomes (like improvement in orthostatic vitals, reduction in inflammatory markers, normalisation of metabolite levels) alongside symptom changes to truly validate each element of the hypothesis.

Therapeutic Strategies for Augmenting Lecithin–Cholesterol Acyltransferase Activity in ME/CFS & Long COVID

Reduced activity of lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) may represent a central pathophysiological mechanism in a subset of patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Long COVID and other Post-acute infection syndromes (PAISs) particularly those with genetic variants affecting enzyme function. Several potential therapeutic strategies to restore or augment LCAT activity are currently under investigation or theoretical consideration, including recombinant enzyme replacement, small molecule activators, and apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) mimetics. Their relative utility may depend significantly on the specific genetic background of the patient, particularly the presence of missense mutations such as the rs4986970 AA genotype.

Recombinant LCAT Enzyme Therapy

Recombinant human LCAT (rhLCAT; also known as ACP-501) is the most direct therapeutic approach to restore LCAT activity. It has demonstrated efficacy in enhancing reverse cholesterol transport, normalising HDL particle composition, and correcting lipid abnormalities in both preclinical and early-phase clinical settings. For individuals with reduced LCAT activity due to genetic variants such as rs4986970, recombinant therapy may offer a promising strategy. Although the specific functional impact of rs4986970 has not been definitively characterised, it is plausible that certain variants may reduce enzyme efficiency or stability. In cases where endogenous LCAT activity is compromised, recombinant enzyme therapy bypasses the need for native enzyme function by supplying fully active LCAT exogenously, independent of the patient’s genetic background.

Small Molecule LCAT Activators

Small molecule LCAT activators, such as DS-8190a, function by stabilising the enzyme’s active conformation and enhancing its catalytic efficiency in the presence of apoA-I. These agents have shown promise in preclinical models of atherosclerosis and metabolic dyslipidemia. However, their effectiveness is generally contingent upon the presence of a structurally intact and partially functional endogenous LCAT enzyme. In individuals carrying genetic variants that reduce—but do not abolish—enzyme activity, such as rs4986970, small molecule activators may be beneficial by enhancing residual function. Their benefit may be limited if the variant results in a severely misfolded or unstable protein, although further functional characterisation of rs4986970 is needed to assess this.

Apolipoprotein A-I Mimetics

ApoA-I mimetics are peptide or small-molecule compounds designed to replicate the activating effect of native apoA-I on LCAT. These agents can enhance the binding of LCAT to HDL particles and support esterification of free cholesterol, indirectly promoting LCAT activity. Their effectiveness also depends on the presence of an enzyme capable of responding to activation. In individuals with LCAT variants that impair the apoA-I interaction or reduce catalytic activity, such as rs4986970 if it proves functionally significant, the benefit of apoA-I mimetics may be partial. Nonetheless, they could still serve as adjunctive therapies in cases with residual LCAT function or when recombinant enzyme replacement is unavailable.

Clinical Implications

These distinctions have important implications for precision treatment of LCAT dysfunction in ME/CFS. In patients with the rs4986970 AA genotype or other deleterious missense mutations, recombinant enzyme therapy represents the most rational and likely effective therapeutic option. In contrast, patients with epigenetic suppression or post-translational inhibition of LCAT, but intact protein structure, may benefit from small molecule activators or apoA-I mimetics. Genetic screening may therefore be essential to stratify patients and personalise treatment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this ME hypothesis offers a mechanistic framework that accounts for the illness’s clinical heterogeneity and its diverse physiological abnormalities. While it draws together key findings across immune, metabolic, vascular, and autonomic domains, it also highlights the complexity of therapeutic intervention. Targeting one disrupted pathway in isolation—such as supplementing PC or suppressing inflammation—may be insufficient or even counterproductive if other components of membrane lipid regulation remain uncorrected. For example, increasing PC availability in the context of unresolved LCAT dysfunction could accelerate membrane AA accumulation, worsening inflammatory mediator release and shifting a patient into a different functional subtype.

Rather than stratifying patients solely into discrete subgroups, it may be more appropriate to assess each individual’s biochemical and genetic landscape across key axes of dysfunction: LCAT activity, PC status, PPAR-γ signaling capacity, membrane AA content, eicosanoid profiles (e.g., prostaglandins and leukotrienes), norepinephrine dynamics, and acetylcholine synthesis. When combined with genetic testing—such as variants affecting MTHFR, LCAT, PEMT, PPARγ, ALOX5, COX2 or DBH—this multidimensional approach may allow for construction of personalised “subtype profiles” that reflect each patient’s unique disease mechanism. Such precision phenotyping could explain the inconsistent results of previous ME clinical trials and may be essential for developing rational, effective treatment strategies.

While this hypothesis emphasises LCAT dysfunction as a central initiating factor, it is important to recognise that similar patterns of membrane lipid dysregulation and autonomic imbalance may arise through alternative mechanisms. Variants in other genes involved in reverse cholesterol transport, such as ABCA1, APOA1, or CETP, may also impair cholesterol clearance and contribute to membrane rigidity and insulin resistance. Likewise, disruptions in AA trafficking—whether through altered activity of PLA₂ enzymes, LPCAT3, or fatty acid transport proteins—could independently lead to excessive free AA accumulation and downstream production of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators, even in the absence of primary LCAT dysfunction.

Moreover, autonomic dysregulation characteristic of ME could potentially emerge from direct genetic or regulatory disturbances in catecholamine handling. Variants in INSR (insulin receptor), SLC6A2 (norepinephrine transporter), ADRA2A/C (α₂-adrenergic autoreceptors), COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase), or enzymes involved in norepinephrine biosynthesis (e.g., TH, DBH, or GCH1) may independently perturb norepinephrine tone, transporter expression, or receptor responsiveness. In such individuals, autonomic dysfunction may develop even in the absence of LCAT, PC, or cholesterol metabolism abnormalities. These parallel pathways highlight the multifactorial nature of ME and the possibility that multiple molecular constellations may converge on a shared neuroimmune-metabolic phenotype. As such, delineating the relative contribution of lipid-based versus direct catecholaminergic mechanisms will be essential for advancing precision diagnostics and guiding subtype-specific interventions.

Ultimately, this model reinforces that ME is not a singular disease entity but a systems-level disorder driven by interacting molecular disruptions. Future research should focus not only on validating these pathways but also on building integrative diagnostic platforms that capture the complex interplay between membrane composition, intracellular signaling, and autonomic regulation.

References

- Arron HE, Marsh BD, Kell DB, Khan MA, Jaeger BR, Pretorius E. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: the biology of a neglected disease. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1386607. [CrossRef]

- Maksoud R, Magawa C, Eaton-Fitch N, Thapaliya K, Marshall-Gradisnik S. Biomarkers for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): a systematic review. BMC Med. 2023;21:189. [CrossRef]

- Mandarano AH, Maya J, Giloteaux L, Peterson DL, Maynard M, Gottschalk CG, Hanson MR. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients exhibit altered T cell metabolism and cytokine associations. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(3):1491–1505. [CrossRef]

- Słomko J, Estévez-López F, Kujawski S, Zawadka-Kunikowska M, Tafil-Klawe M, Klawe JJ, et al. Autonomic phenotypes in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) are associated with illness severity: a cluster analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2531. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen CB, Kumar S, Zucknick M, Kristensen VN, Gjerstad J, Nilsen H, Wyller VB. Associations between clinical symptoms, plasma norepinephrine, and deregulated immune gene networks in subgroups of adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;76:82–96. [CrossRef]

- Haase CL, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Qayyum AA, Schou J, Nordestgaard BG, Frikke-Schmidt R. LCAT, HDL cholesterol and ischemic cardiovascular disease: a Mendelian randomization study of HDL cholesterol in 54,500 individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(2):E248–E256. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy G, Spence VA, McLaren M, Hill A, Underwood C, Belch JJF. Oxidative stress levels are raised in chronic fatigue syndrome and are associated with clinical symptoms. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39(5):584–589. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Herrera OM, Zivkovic AM. Microglia and cholesterol handling: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Biomedicines. 2022;10(12):3105. [CrossRef]

- van der Veen JN, Lingrell S, Gao X, Takawale A, Kassiri Z, Vance DE, Jacobs RL. Fenofibrate, but not ezetimibe, prevents fatty liver disease in mice lacking phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase. J Lipid Res. 2017;58(4):656–667. [CrossRef]

- Huang K, de Sá AGC, Thomas N, Phair RD, Gooley PR, Ascher DB, Armstrong CW. Discriminating myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and comorbid conditions using metabolomics in UK Biobank. Commun Med. 2024;4:248. [CrossRef]

- Suda T, Akamatsu A, Nakaya Y, Masuda Y, Desaki J. Alterations in erythrocyte membrane lipid and its fragility in a patient with familial lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency. J Med Invest. 2002;49(3–4):147–55. (No DOI available).

- Niesor EJ, Nader E, Perez A, Lamour F, Benghozi R, Remaley A, et al. Red Blood Cell Membrane Cholesterol May Be a Key Regulator of Sickle Cell Disease Microvascular Complications. Membranes (Basel). 2022;12(11):1134. [CrossRef]

- Meurs I, Hoekstra M, van Wanrooij EJ, Hildebrand RB, Kuiper J, Kuipers F, et al. HDL cholesterol levels are an important factor for determining the lifespan of erythrocytes. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(11):1309–19. [CrossRef]

- Saha AK, Schmidt BR, Wilhelmy J, Nguyen V, Do J, Suja VC, et al. Red blood cell deformability is diminished in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2019;71(1):113–116. [CrossRef]

- Thomas N, Gurvich C, Huang K, Gooley PR, Armstrong CW. The underlying sex differences in neuroendocrine adaptations relevant to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2022;66:100995. [CrossRef]

- Fluge Ø, Mella O, Bruland O, Risa K, Dyrstad SE, Alme K, et al. Metabolic profiling indicates impaired pyruvate dehydrogenase function in myalgic encephalopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight. 2016;1(21):e89376. [CrossRef]

- Robertson SD, Matthies HJG, Owens WA, Sathananthan V, Christianson NSB, Kennedy JP, et al. Insulin reveals Akt signaling as a novel regulator of norepinephrine transporter trafficking and norepinephrine homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2010;30(34):11305–16. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen CB, Kumar S, Zucknick M, Kristensen VN, Gjerstad J, Nilsen H, et al. Associations between clinical symptoms, plasma norepinephrine and deregulated immune gene networks in subgroups of adolescents with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;76:82–96. [CrossRef]

- Walitt B, Singh K, LaMunion SR, Hallett M, Jacobson S, Chen K, et al. Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat Commun. 2024;15:907. [CrossRef]

- Kavelaars A, Kuis W, Knook L, Sinnema G, Heijnen CJ. Disturbed neuroendocrine-immune interactions in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(2):692–6. [CrossRef]

- Goto T, Kikuchi S, Mori K, Nakayama T, Fukuta H, Seo Y, et al. Cardiac β-Adrenergic Receptor Downregulation, Evaluated by Cardiac PET, in Chronotropic Incompetence. J Nucl Med. 2021;62(7):996–998. [CrossRef]

- Fry AC, Schilling BK, Weiss LW, Chiu LZF. β2-Adrenergic Receptor Downregulation and Performance Decrements During High-Intensity Resistance Exercise Overtraining. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101(6):1664–72. [CrossRef]

- Lim EJ, Kang EB, Jang ES, Son CG. The Prospects of the Two-Day Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET) in ME/CFS Patients: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):4040. [CrossRef]

- Patriarchi T, Qian H, Di Biase V, Malik ZA, Chowdhury D, Price JL, et al. Phosphorylation of Cav1.2 on S1928 uncouples the L-type Ca2+ channel from the β2 adrenergic receptor. EMBO J. 2016;35(12):1330–45. [CrossRef]

- Figlewicz DP, Szot P, Chavez M, Woods SC, Veith RC. Intraventricular insulin increases dopamine transporter mRNA in rat VTA/substantia nigra. Brain Res. 1994;644(2):331–4. [CrossRef]

- Dehlia A, Guthridge MA. The persistence of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2024;106297. [CrossRef]

- Kuypers FA, Rostad CA, Anderson EJ, Chahroudi A, Jaggi P, Wrammert J, et al. Secretory phospholipase As2 in SARS-CoV-2 infection and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2021;246(23):2543–52. [CrossRef]

- Sumantri S, Rengganis I. Immunological dysfunction and mast cell activation syndrome in long COVID. Asia Pac Allergy. 2023;13(1):50–53. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuraishy HM, Hussien NR, Al-Niemi MS, Fahad EH, Al-Buhadily AK, Al-Gareeb AI, et al. SARS-CoV-2 induced HDL dysfunction may affect the host’s response to and recovery from COVID-19. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11(5):e861. [CrossRef]

- Man DE, Andor M, Buda V, Kundnani NR, Duda-Seiman DM, Craciun LM, et al. Insulin Resistance in Long COVID-19 Syndrome. J Pers Med. 2024;14(9):911. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).